8Nurturing

MARJORIE HARNESS GOODWIN AND CHARLES GOODWIN

Despite the busyness1 of the Los Angeles families we studied, the interactions many family members experienced during shared leisure activities as well as while doing everyday chores and children's work (homework) were characterized by caring, supportiveness, playfulness, and pleasure, just the sorts of experiences psychologists2 and psychological anthropologists3 have said are necessary in order for individuals to thrive. In the midst of mundane, largely unstructured activity such as taking a walk, riding in the car, or cleaning a piano keyboard, children and parents could cultivate active and joyful engagement in imaginative inquiry about the world, often colored by language play during forms of “occasioned knowledge exploration"4 during “quality moments.”5

This chapter demonstrates ways in which forms of love were manifested among family members in everyday life situations and activities in four families. When children received outstanding grades on report cards or demonstrated superior talent in sports, parents displayed considerable enthusiasm for their accomplishments. Parents actively responded to children's desires to learn new skills (e.g., making waffles for family breakfast) by apprenticing them into the activity. Love was also expressed through building opportunities for children to discover new ways of encountering the world or solve problems during unstructured activities such as an evening walk in the neighborhood or while cuddling in bed on a Saturday morning. Through the tactics of tough love parents taught forms of responsibility and perseverance in the midst of conflict. While caring for children was primarily in the hands of parents, siblings in some households were also important partners in nurturing young children, teaching self-care activities, and reading with them, providing moments of relief for parents and opportunities for learning and rich emotional exchange.

Our methodology of videotaping everyday interactions provides a unique lens for examining how moments of intense caring and apprenticeship unfolded in real time and through embodied practice; rarely has it been possible for researchers to document the in situ experience of family members building a life with one another in the intimate spaces of the home in the way we did. This chapter differs from others in this book in that we examine displays of family affection as if looking through a microscope; we investigate how feelings and relationships unfold moment by moment in daily activities. Specifically, we explore how the choreographing of routine events (linked to family cultural values and aspirations) highlight forms of caring and empathy in four different families.

THE REIS FAMILY: SOCIALIZING FOR SUCCESS IN SPORTS AND ACADEMICS

The Reis family devoted considerable energy to preparing their children for the “credentials crisis"6 that twenty-first-century children experience when applying for college. The Reis parents wanted their children to excel in sports so they could get sports scholarships to attend college. Through “concerted cultivation,"7 the parents directed children's development and attempted to stimulate children's cognitive and social skills, in projects designed to accumulate cultural capital.8 The Reis parents expressed love through endless expenditures of time arranging for structured sports and academic preparation (Kumon) for their children. During the weekdays the Reis family, the busiest family in our study, was in high gear, often going from one after-school activity to another in the same afternoon before dinner.9 The Reis children spent 56 percent of their activity time on sports;10 approximately nineteen hours per week were allocated to children's out-of-school practices. Both children (Allison, age 8, and Mike, age 7) were enrolled in a number of sports simultaneously, such as baseball, basketball, ice hockey, fencing, and tennis. Life in this family was so hectic that a whiteboard used for doing homework en route from one activity to another was a permanent fixture to the backseat of the family van.

The parents encouraged sports because of what they felt was a lack of sports in their own upbringing. After dinner in the presence of Dad's mother the following conversation with two ethnographers about why the family encouraged sports took place.

| DAD: | Because my mother never encouraged it when I was growing up. | |

| MOM: | Ou:::::. passing blame here. | |

| DAD: | She wouldn't let me play football because she was afraid the other kids were too big. ‘Cause I was big for my age. | |

| MOM: | SO because of that ((turning to grandma)) We allow our daughter to play with weapons, and our son to get pucks shot at him. |

The Reis parents collaborated in transporting their children to events on weekends. Their strategy was “divide to conquer"—for example, taking one child to Fresno and another to Bakersfield for competitions. Technology was crucial in this family and provided a material indicator of the family's busyness.11 In order to keep track of the multiple activities (and ever-changing dates for activities such as Allison's baseball games), Mom relied on her Palm Pilot to keep everything organized; she commented it was what “keeps everyone all together.” Cell phones were also important for this family; although family members often had to be in disparate places because of the busy schedules taking children to activities, they always felt connected because parents were constantly updated regarding the achievements of children, whether at the hockey rink, baseball field, or tennis court. In the midst of a Saturday morning hockey practice Mom phoned Dad to inform him of the superior playing that Mike was doing as goalie to propel his team to win. As in other American contexts,12 winning and being the best player was important.

As Mom was present at her son's hockey activities on weekdays as well, she not only could fortify him during breaks with Gatorade but also could congratulate him on specific plays with exclamations such as, “Excellent game! That was great! That was great!” while patting him on the head. When Mike informed his mom that he had scored two goals, she gave him a high five while exclaiming, “No way! You scored two goals today? Dude! ((undulating sound))." This assessment showed heightened affect not only through the positive assessment “No way!” but also through undulating voice quality over the term “Dude” and a celebratory high-five handclap. Such forms of positive assessments contrasted dramatically with other parents’ greetings on first reunions after sports activities,13 as, for example, in “Bess sweetie? I'm gonna pack up the stuff and then I'll come back and get you. Okay?” Parents were frequently in such a hurry to collect belongings and move to the location of their next activity as expediently as possible that they did not make time for talking about their children's performances in sports at the time of the sports event itself, though commentaries might come later in the day on the way home or at dinner.

In order to make the hectic schedule of activities possible, Pam Reis found a job that allowed her to have time flexibility—director of financial aid at a high school. What started out as a part-time job became more permanent employment. In fact, she gave up a former job as a television producer so that she could dedicate herself to “producing a family.” She explained that she really enjoyed being able to pick up her children from school and spend the afternoon with them. Pam Reis was fortunate that she could depend on her eighty-year old mother-in-law to take care of the children when she needed her. As she stated, “And I love the fact that she's here and that the kids have such a great relationship with her.” The paternal grandmother went to all the games and special events that the children participated in. The Reis family had a human safety net, someone they can call on for childcare if they needed it.

Scholarship was important in the family. Allison had a perfect report card. Mike, the youngest child in his class, had excellent grades as well, with 100 percent every week in spelling. There is little wonder that this was the case, given the family's ever-vigilant attention to homework. Ethnographers observed that the entire drive from home to school each morning before a spelling test was occupied with Mom quizzing her children on the list of the day's spelling words.

Competition in sports was critical in this family: advice giving frequently contained assessments and rankings of players relative to one another. As Mike left the benches to go onto the hockey rink one afternoon, Mom told him, “I want you to beat Eric's butt today, okay?” When Mike described a classmate as faster than he was to his father, Dad responded, “But they don't play goalie better than you do.” Family members talked about the comparison of Allison (eight) and a boy, age fourteen, who both came in eighth place in fencing in the Junior Olympics. Mom reported that the coach said, “Alex, it wasn't a big deal to come in eighth. For you [meaning Allison] to come in eighth was amazing!” Joking at dinner about how happy her mom would be should she be in the Olympics, Allison said, “Mommy, if I win a gold medal i(h)n the Olympi(hh)cs? You're gonna be stuck to the ceiling and I scrape—I'll have to scrape you o(hh)ff. With a spatula.”

Informal coaching was a frequent activity in the Reis family. When Dad drove Mike home from hockey practice he critiqued him on the way he had played: “You need to make sure you focus a little more. And I'd—We're going to work on your left kick out. Your left right kick out. ‘Cause what happens when you kick your left leg out? If your left foot stays in the same place, And your body goes to the right. The right.” Even in the midst of individual activities such as Mike's bike riding on weekends Pam Reis assumed the role of coach, with talk such as, “Go slow. Uh oh. Use your brakes not your shoes. Push on your brakes until you stop.” Simultaneously monitoring Allison's skating, she said, “You gotta get much better at the T stop. It's not real strong. It's a little wobbly. I want you to come to a complete stop doing the T.”

One might predict that with such a tightly organized and managed schedule there would be little time for creative activities such as working collaboratively to solve everyday problems or ponder the mysteries of everyday life14 outside of the more extended time together that eating a meal together affords. We did not expect playful talk to be occurring at 7:00 A.M. as family members were cuddling together in the parents’ bed! As the family was discussing a neurosurgeon—"brain doctor"—who was also a reporter, Dad posed a question: “Is a brain doctor smarter than other doctors′ cause he has to work on the brain?” Allison replied to this with, “Yeah. ‘Cause he takes all of the smartness out of them.” As the conversation drifted to consideration of hypothetical dual careers (Allison as a zoologist and a fencer, Mike as a hockey playing drummer) the parents created a scene that would meld zoology and fencing.

| MOM: | If your animal goes out of control, | |

| DAD: | No no. I was thinking more like, | |

| You can watch the animals | ||

| And then you have the perfect skewer for barbecuing them. |

The topic next drifted to the possibility of Mike being a poor poet rather than any other profession, and the family together explored the economics of various professions and their implications for parents having to support their offspring. Countering the idea that poets are necessarily poor, Allison inserted her own idea that a poet celebrity such as Shel Silverstein need not imply a situation of abject poverty.

While in bed, Mom, commenting as informal coach, joked about seven-year-old Mike's plays as goalie the day before during hockey practice: “You let five get past you. But so did the other guy.” Mike playfully disagreed with his mom about the scores in the previous night's game. The talk about competitive activities was all the while overlaid with playful touches, reciprocal nose taps and tickling, and sound play involving the terms confuse you and confusable.

Figure 8.1. Making waffles cooperatively.

| MOM: | I was trying to confuse you. | |

| MIKE: | I tried to confuse you too. | |

| MOM: | Well you almost did. But not really. Not really. I was trying to confuse you too. | |

| MIKE: | It's confusable. | |

| MOM: | Are you confusable? | |

| MIKE: | NO. | |

| MOM: | Well neither am I. ((tickles Mike)) | |

| MIKE: | eh heh! | |

| MIKE: | Hey Mom. | |

| MOM: | What. | |

| MIKE: | Beep! ((taps her on the nose)) | |

| MOM: | Hey Mike. | |

| MIKE: | What. | |

| MOM: | ((does a reciprocal play punch)) |

As the family was cuddling, discussion of Mike's future as a hockey playing drummer was interspersed with wordplay, tickling, and gentle nose tapping to punctuate points. Across a range of circumstances the Reis children were socialized to view events in terms of rank ordering of positions in a game or monetary worth on a relative scale of professions. The Reis parents helped their children learn the embodied skills they would need in order to excel in sports (skating, riding bikes, hockey, shooting baskets, fencing, etc.) as well as the intellectual skills they needed to get perfect scores on tests. They assisted in children's activities such as Little League baseball; on the baseball field through helping to pitch or referee Mom demonstrated concern for their children's development through sports with her active engagement.

Figure 8.2. Pouring waffle batter.

On occasion children in the Reis family initiated activities that benefited the entire family. In the midst of the Saturday morning cuddling Mike asked if he could make waffles for a family breakfast. Although he had never done so before his mom patiently worked with him in what could be viewed as a lesson in scientific practice. Ingold argues that a young apprentice is led to “develop a sophisticated perceptual awareness of the properties of his surroundings and of the possibilities they afford for action” as he is instructed in “what to look out for, and his attention is drawn to subtle clues that he might otherwise fail to notice.”15 Mom helped Mike to read the recipe; locate, assemble, and position the tools and ingredients for the task; and showed him how to hold and use a measuring spoon, understand the difference between teaspoons and tablespoons, figure out the arithmetic to make double the recipe, measure the flour in a glass cup, break up hardened brown sugar in a cup, place batter into a waffle iron—all the time carefully guiding his engagement with the task and warning what mishaps could occur. She physically encircled him, helping him hold a measuring spoon in his hand as she poured salt into it and ladling batter onto the waffle iron. In essence Mike as novice was being trained in the enskillment that is needed to be a cook. Mom taught when it is important to be precise in measurement (not adding too much salt) and when it is not as important (when adding sugar). (See Figures 8.1 and 8.2.)

Through his waffle making Mike contributed to the well-being of the family and received appreciative assessments; tasting one of his waffles, Mom commented, “Oh man. ((hand slap)) They're awesome! Excellent job.” (See Figure 8.3.)

Figure 8.3. Mom congratulating child on making waffles with a high five.

Parents such as the Reises actively assisted their children in acquiring important skills they could use in navigating future problem-solving activities, in schoolwork, sports, or helpful activities such as cooking. They were also highly successful in getting their children to do self-care chores without extended argument,16 as occurred while doing cleanup chores in some families.17 When the Reis children mildly protested compliance with, for example, taking a bath, they were calmly told that following through with what a parent wants them to do was “non-negotiable.”18 Mom rarely raised her voice, and the protest ended. Parents demonstrated engagement in the lives of children through extended dialogue with them. Through playful and counterfactual talk that occurred in the midst of cuddling in bed on a Saturday morning or while being shepherded to brush teeth,19 children learned to envision themselves as actors who had career trajectories and could construct hypothetical worlds and as agents who could playfully dispute ideas with their parents, yet eventually complied with what they were told to do.

THE TRACY FAMILY: CULTIVATING CREATIVITY AND JOYFUL EXPLORATION

In contrast to the Reis family, the lives of Miles (age five) and Gwen (age eight) Tracy were not organized with respect to tightly scheduled age-specific sports or academic activities, though Gwen did participate in weekly piano lessons. On weekends the family members enjoyed activities such as excursions to the downtown library, walking on the beach in Santa Monica and making sand castles, playing music together (Dad on keyboard and Gwen on the piano), or simply hanging out in the living room together. What was central to Tracy family life was that in the midst of family-centric activities children and parents engaged in a continuous stream of deeply involving interactions. Parents and children interspersed whatever activity they were undertaking with playful as well as joyful moments of exploration of possible ways the world could be understood, cultivating active engagement in imaginative inquiry about the world.

When the parents in the Tracy family came home, all office work was left behind, and the focus was on the children. Within minutes of when Dad came home he took the children for a half hour walk around the neighborhood. Mom felt this was a very important time of the day for the children to develop cognitive skills in talk with Dad. During neighborhood walks, in the midst of car noises and against the cityscape environment, Dad and children entered into a play world, taking on the characters of different animals (a zebra, a cobra, and a firefly) and elaborating dramas between these animals—chasing, scaring, and assisting one another—as they walked several blocks. In addition, Dad asked his children about their day at school and helped them think of ways of dealing with problems as strangers to a new school. After Gwen discussed her new school friend from Brazil, Dad empathized with his daughter's situation being a newcomer in a school; then, putting her situation into perspective, he commented on how hard it must be for her Brazilian friend to be both new to the school and from another country. The evening walk in the dark was therapeutic, as it provided a daily opportunity for eliciting talk about children's feelings, opinions, and thoughts about their day.

The walk provided the opportunity not only for the Tracy children to dramatically enact and collaboratively describe the habits of animals, but also to hypothesize various things about their natures. As Miles enacted a firefly, Dad became uncertain about how the firefly's “lighter” worked. In so doing he left open the possibility of one of his children resolving what for him was an unsolved mystery. In response Gwen connected the idea of a firefly's “lighter” with how a flashlight works and proposed, “They have some sort of charge.” Repeating what Gwen said ("Some sort of charge"), Dad ratified her understanding while expanding on it, saying, “Or maybe electrical charge?” He then introduced another possible explanation for how the firefly produces light with “some kind of chemical process.” In response Gwen provided a tentative biological model of how the “lighter” of a firefly could be passed down from one generation to the next, proposing, “maybe charges from their mother and their mother before that and their mother before that.”

After talk about the properties of fireflies Dad began commentary on the animal he was enacting, the zebra. He pondered how it is that despite having stripes that “are very easy to see” (i.e., having little camouflage), zebras have nonetheless escaped being eaten. He then mentioned the animal that zebras would most have to fear, stating, “But the lions haven't got ‘em all yet.” At this point Gwen joined in the discussion, adding her own perspective on animal behavior: “The lionnesses—uh–hunt the most. The lion is actually (.) sleeping at home while the lioness is doing all the work.” To this Dad responded, “Right. That happens in a lot of societies where the women do most of the work.” Father permitted his daughter to offer her own position about the roles of lions and lionesses. He subsequently added his own commentary on the social roles of women in society. Much like what has been discussed as “science at dinner"20 or emergent “islands of expertise,"21 here Dad socialized perspective taking and critical thinking in the midst of a very playful scene. Moments of “occasioned knowledge exploration"22 occur when children and parents extemporaneously connect new knowledge to existing knowledge in collaborative endeavors, such as the talk about firefly “lighters” and lions’ and lionesses’ hunting habits during an evening walk. They thus differ from didactic “lessons” in which parents lecture children about science (e.g., discussing how rockets are launched by referring to encyclopedia entries) without a child's inviting them to do so.

Father was very attentive to any indication of his children's wanting to know more about how the world works. He responded to what his children were interested in learning about in age-appropriate ways. When Miles made a comment about lights that were blinking on a parked car, talk was transformed into a lesson about hazard lights. Dad animated the car lights talking as he explained what the lights were “saying”: “I'm just stopping here for a minute. Don't bother me, policeman.” However, when Gwen asked about the blinking car lights he provided an elaborated explanation of “hazard lights” for her, detailing their practical uses. In explaining the meaning of the blinking lights, Dad waited until the children displayed interest in the developing topic (when Gwen asked the question, “Do you put that on sometimes?") before providing a more elaborated discussion. Explanations were child-oriented and carefully fitted to the level of understanding of each child.

A playful rendering of talk23 was also characteristic of the way that parents in this family interacted with their children. One Saturday morning in the living room area, Gwen was looking at encyclopedia entries for parts of the body on the computer, and Dad and Miles were nearby cleaning the keyboard for her to use. The computer voice stated, “Flexor digitorum superficialis muscle.” Immediately Dad responded playfully, focusing on one part of the Latin nomenclature. He stated, “Superficialis, that must not be very important.” Gwen's next move was to provide a further playful rendering, emphasizing “fish” in “Super fish ialis.” Dad laughingly responded and then using the sounds of the same words as Gwen, interjected a line modified from Mary Poppins: "Superfishialic cajifrigilistic exphiladosus?” In the midst of Dad's talk Miles chimed in with his own further permutation of “superficialis,” singing “Super fish!” Then in his next move Miles provided his own fanciful explanation about how fish might have evolved into land animals, stating, “But fishes can't go on the ground. Just if they have—a ear muff . . . A:nd—a:nd—a breathing lip- atector.” Father and children made use of sound play, a way of sequencing to talk that children delight in,24 to transform what the computer voice said. What emerged was a child's hypothesis on the evolution of fishes. Much like a jazz composition,25 participants carefully attended to the sounds of others to produce their own playful elaboration of ongoing talk.

Sequencing talk to the sound properties of language rather than literal meaning occurred across multiple exchanges in the family. When Dad said one night that he was reading a story based on a story by Octavio Paz, Miles responded, “Paws?” Dad then answered with, “Not like kitten paws.” When Gwen added, “Octave paws. Like octaves on a piano and paws like a kitten.” Miles next riffed, “Pause like stop.” Though Dad eventually provided his interpretation of what Octavio meant, he permitted the children to elaborate their own meanings in the midst of his talk.

While some families in our study infused their directives with threats,26 an alternative way of framing directives in the Tracy family was through teasing and wordplay. At mealtime one evening the family had been discussing a shy new Brazilian boy in Gwen's classroom. Mom and Dad told Gwen to ask him about the samba, a Brazilian dance, and they discussed their versions of what Brazilian Portuguese sounded like. As the conversation about Brazilian Portuguese wound down, Mom initiated talk about getting ready for bed: “Okay. Time to brush your teeth.” This was playfully countered by Gwen with “Time to brush your teeth. That is not Brazilian.” Answering Gwen, Mom then said, "Samba. Samba to the bathroom.” Here, by tying her talk to Gwen's countermove, she issued a directive that entered a frame of play rather than seriousness. Yet she got results as well. Gwen started to literally dance her way to the bathroom. When Miles responded, “I don't know how to samba,” in an attempt to stall the directive, Mom, tying her talk to the same form answered, “You'll learn how to samba.” She then produced an explicit command: “Get in the bathroom.” Providing backup to Mom's directives, Dad then issued direct imperatives in rapid-fire form like a drill sergeant: “Now. Go. Wash face, wash hands, brush teeth.” Such forms of bald commands were in fact more frequent in the Tracy family than in another family where there was little playful interaction.27 While Mom infused her directives with features of playful negotiation, Dad demanded and expected compliance with his directives.

In the Tracy family, as in the Reis family, parents treated their children as capable of carrying out complex tasks and invited their coparticipation in matters of concern to the economics of the household (as in seven-year-old Mike cooking waffles in the Reis family). For example, on returning home from school Mom gave her eight-year-old daughter, Gwen, the task of ordering books from a school pamphlet. She asked Gwen to make up a list of the books she would like to order and their prices. Gwen then devised her own system for prioritizing the books.

Though Mom never mentioned prices as a constraint on the task, Gwen told her, “I bet it's gonna be more than twenty dollars—for all these books.” “I don't think we can get them all, only a few.” Rather than directly oppose her mother, Gwen instead used hesitations and questions ("Do you really want me to get that?” and “You really do?"), forms of disagreement associated with polite adult conversation.28 Rather than counter that they already have a copy of the Guiness Book of World Records, Gwen asked if her mom knew where an earlier version of the book is in the house. Mom eventually came around to Gwen's position with, “Okay, if you don't want to get it this time that's fine.” Gwen proved successful in negotiating the sequence so that she was able to get what she felt was appropriate in a highly mitigated way, using indirect strategies characteristic of adult speech. Miles as well was able to negotiate what he wanted because he has learned how to provide explanations justifying his perspectives in negotiations with parents.29

We see from our brief overview of these two families that loving and playful engagement with children, attending to and providing uptake to what they say, appears to have payoffs for socializing children to be responsible and respectful in carrying out activities that contribute to the well-being of the family (whether cooking or figuring out a budget), doing well in school and in extracurricular activities (whether sports or music), and maintaining peaceful relationships with siblings.

THE WALTERS FAMILY: NURTURING SIBLINGS

It is well known that in small, non-Western agrarian societies siblings are highly valued caregivers as well as socializing agents30 and that sibling care promotes interdependence and prosocial behavior in children.31 In studies of the Kwara'ae of the Solomon Islands Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo describe dialogues between siblings in which empathic attention by the caretaker is important and in which teaching and instruction occurs.32 They note, “In nonserious contexts, which encompass most of everyday life, directives and repeating routines are used to teach infants and young children rights, obligations, roles and cultural expectations associated with birth order, gender, and kin relation; to develop their skills in work tasks and other activities; and to teach language and give them practice in interactional skills.”33

Weisner, summarizing cross-cultural studies, notes, “Most children will rehearse, display and experiment with language capacities and cognitive skills with their siblings well before they will do so with other people.”34 Zukow, studying socialization of rural and urban Mexican children, found that interactive play with sibling caregivers was more advanced than play with adult caregivers.35 Older siblings’ use of both verbal instructions and nonverbal demonstrations help a younger child's transition to a more advanced level of functioning.36 During communication breakdowns in play interactions with a twenty-one-month-old, Zukow observed that mothers did not adjust their verbal messages, but instead reiterated verbal directions not understood by the child that interfered with completing the activity.37 By way of contrast the child's three-and-a-half-year-old sibling was able to reframe the interaction and engage the younger child by providing nonverbal demonstrations of what to do as well as commentary. Older siblings differed from parents by at times providing very explicit correction of a younger sibling's activity, calling into question the younger sibling's competence,38 while providing very explicit models of appropriate performance. While adult caregivers guide the child in subtle ways, “siblings in their own exuberance, impatience, or pride seemed intent on showing off their own competence.”39 Zukow has proposed that because siblings accommodate to young children less than adults, their participation with siblings could encourage infants’ development of pragmatic skills.

Figure 8.4. Helping baby to get from bed to the bathroom.

In our study of videotaped interactions we found that children of dual-earner middle-class Los Angeles families could also act as critical socializing agents of younger siblings, freeing parents for engagement in other household tasks.40 The forms of participation and engagement in families with toddlers vary quite a lot; they included momentary transactions of entertaining baby when Mom was fully occupied (the Slovenskis), extensive custodial care with a teenage sister (the Morrises), pretend and parallel play and helpful voluntary caretaking while Mom was busy (the Moss family), roughhousing (the Beringer-Potts family), assistance in self-care and in initiation of playful interactions (the Pattersons), and rich engagement, characterized by joint attention in mutually enjoyable activities (the Walterses). In this section we will look at the forms of participation through which ten-year-old sibling caretaker Leslie Walters and her eighteen-month-old sibling, Roxanne, organized involvement and the teaching of enskillment in a routine activity: tooth brushing.

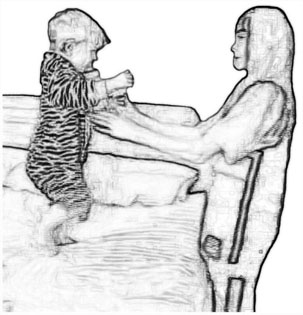

Figure 8.5. Apprenticeship by nesting baby's body.

Investigating a routine task important in the lives of American children, tooth brushing, Tulbert and Goodwin found that explanation and critique were interspersed in ten-year-old Leslie's mentoring of her younger sister into the activity.41 Leslie's caretaking practices had close resemblances to the way in which Kwara'ae child caretakers go to great lengths to engage in dialogues with their charges during routine activities, naming objects, telling them stories, and so on.42

Narration about the steps involved in tooth brushing occurred as the activity unfolded. Directives (e.g., “Roxanne spit") were given as the child manager herself was accomplishing the activity requested (spitting). Demonstrations of how to perform a task resembled those of Kaluli mothers; they provide instructions for children on how to carry out an activity while embodying the activity (cupping the hands to drink water from a stream, peeling a hot cooked banana, or pulling weeds from a garden) as they say, “Do like that.”43

We will examine in some detail a tooth brushing activity that was launched on a weekday morning, as Leslie and her younger sister, Roxanne, were sitting close together on their parents’ bed watching television. Leslie turned to her sister and said, “Roxanne, just stay here. Okay? Roxanne, I need to—go—I need to brush my teeth." When subsequently Roxanne turned her body ever so slightly toward her older sister, Leslie quickly readjusted her course of action. She queried, “D'you wanna come and brush your teeth with me? Okay, let's go brush our teeth.” Leslie got off the bed and offered her arms for Roxanne to climb into (Figure 8.4). As a highly attuned caregiver, Leslie responded to her sister's change in body orientation by finding ways to include her sister.

When they got to the bathroom, Leslie moved a small stool for Roxanne to stand on before positioning Roxanne on top of it and guiding her to face the sink. Leslie then requested that Roxanne give her the bottle she had in her mouth and put it on the shelf adjacent to the sink. She thus freed both her sister's hands and directed attention to the new task, closing one activity in order to begin another. Stepping on the edge of the bathtub, she retrieved the objects that the two would need for brushing teeth. Stating, “Okay, so,” Leslie verbally demarcated the initiation of the actual brushing routine, turned on the water, and lifted Roxanne's toothbrush under the running water. As Leslie was uncapping the toothpaste, Roxanne extended her toothbrush to Leslie. Leslie then initiated a politeness routine, saying, “Thank you Roxanne. Could you say ‘you're welcome?” When no answer was forthcoming, Leslie repeated the request: “Roxanne, could you say ‘you're welcome’ for me?” Here, as at the onset of the activity, requests such as “could you” and questions were used to structure the activity.

After Leslie prepared her own toothbrush the two were positioned toward the mirror in a nesting formation (see Figure 8.5). As Leslie began brushing her own teeth she gave Roxanne a directive: “Now keep on brushing your teeth Roxanne.” At the age of eighteen months, Roxanne was already able to show her familiarity with various steps of this routine through her production of the correct physical gestures. She held her toothbrush out toward her sister, waiting for the application of toothpaste.

After Leslie put her toothbrush on the sink and closed up the toothpaste, she provided closure to the activity: “We're all done.” Simultaneously Roxanne took the toothbrush out of her mouth. Through talk and embodied actions and gestures, Leslie expertly turned her sister's physical attention toward the activity and then guided her to its completion.

This example allows a view to how small children's presence in the unfolding of their caregiver's activities affords a site for the socialization of carefully attuned attention to a physical activity. Roxanne knew some aspects of how to physically participate in the unfolding sequence of the routine (in holding out of the brush), though she did not yet know how to embody the rhythm of brushing. Leslie explicitly pointed out the action steps of the sequence as she performed them, providing a verbal narrative of the physical routine.

Across a range of different activities, from reading a book together to teaching Roxanne how to defend herself and kick, the ensemble of practices that were orchestrated in interaction between Leslie and Roxanne demonstrated a high degree of intersubjectivity,44 supporting Zukow's argument that child caregivers can adjust or finely tune their input to a particular younger child's level of development.45

Often Western siblings’ sophisticated knowledge of the social world has been largely ignored, Here, and across various dual earner families we have studied, we find, as Zukow has argued,46 that older siblings can function as competent socializing agents of younger children, and not merely as monitors of the young child's most basic biological needs. Sibling caregiving provides infants with a great diversity of cognitive and social stimulation while older siblings practice nurturing roles. Children learn how to shift frame between moments of more egalitarian peerlike play and the serious business of self-care activities (changing diapers, putting on clothes, brushing teeth, etc.)—creating a rich social learning environment.47

THE ANDERSON FAMILY: AFFECT AND MORALITY IN HOMEWORK

The types of frameworks for participation that caretakers and children evolve in the midst of moment-to-moment interaction are consequential for how family members shape each other as moral, social, and cognitive actors. Not all participation entailed the sustained expressions of mutual affection we have seen in the previous examples. Participation frameworks for parent-child interaction can change dramatically over the course of time and be quite consequential for how important features of children's “work” (in the present case, homework) are achieved and relations in the family are maintained. The scene we will examine took place on a Monday evening as eleven-year-old Sandra Anderson, who was just coming down with a cold, was lying on her parents’ bed doing her mathematics homework.

What is required for mutual engagement in a task activity? As we saw with Mike Reis making waffles and Roxanne Walters brushing her teeth, in order to carry out relevant courses of action participants must position themselves to see, feel, and in other ways perceive as clearly as possible. This needs to be achieved in ways that are relevant to the activities in progress, considering consequential structure in the environment that is the focus of their attention (e.g., pages of an arithmetic assignment) as well as the orientation of participants toward each other. Participants arrange their bodies precisely to accomplish such work-relevant perception. As Ingold has argued,48 such arrangements are critical to the education of attention. When participants visibly orient to one another and the environment that is the focus of the work they are attempting to accomplish together, their embodied participation framework displays what we could call a cooperative stance. Not going along with what is being proposed in the present, however, is another possibility; it is what Goffman terms “role distance.”49 Given the possibility of noncooperation by children who have both autonomy and choice, frameworks of mutual engagement should be viewed as accomplishments, as frameworks for the organization of cognition and action that are sustained through the ongoing attentive work of people interacting together. How are such frameworks for mutual engagement achieved?

When Dad in the Anderson family initially began to help Sandra with her homework, she refused to fully cooperate. She did not address her father's question about the math problem. Instead of looking toward her Dad and showing coparticipation with respect to what he had said, she closed her eyes and put her head between her arms. She used whining, “put-upon” prosody that suggested that her father's requests interfered with her ability to watch television.

Sandra's father did not get mad but a moment later summoned Sandra, and she answered and turned her head toward him. In line 26 the father further demanded that Sandra attend by producing an explanation that included an environmentally coupled gesture,50 an action that requires that the listener not only see the speaker making the gesture but also take the gesture into account. However, Sandra made no move to more closely attend to the text that her father was pointing toward.

Both Sandra and her father maintained different ideas about how participation in the homework activity should be orchestrated. When Sandra asked her father how to do a problem, he responded by asking for a pencil. However, Sandra simply wanted her father to do the homework for her rather than figure it out herself. She said, “No. Just tell me. How do you do that.” All the while she kept her hands positioned so that she was not looking. Dad then explicitly stated, “I can't just tell you.”

Thus two alternative ways of attending to the work in progress occurred. Sandra refused to move her body into alignment so that she could view the papers that were being worked on. She refused to take a cooperative stance toward the work in progress. An appropriate alignment toward others and the task in progress is crucial for the organization of mundane activities in the lived social world. Father characterized Sandra's actions and refusals to engage in the math task he was helping her with as moral failings.

| ACTOR | ADDRESSEE | |

| 49 | you have to be nice—to me okay. = | |

| 50 | (you) Don't talk to me in that tone of voice. |

Father made explicit the responsibilities that his daughter had with respect to showing appropriate forms of affective engagement. With his complaint, “You have to be nice to me,” he treated Sandra as an actor who was morally responsible for the types of stances she took up as well as the forms of actions she engaged in. However, rather than getting angry, Father refused to continue the activity unless Sandra displayed the appropriate alignment. He then walked out, offering as the reason for this move Sandra's refusal to coparticipate with him (lines 13-14 below) and her derogatory treatment of him (line 16).

The successful completion of the homework session occurred only after Father came back seventeen minutes later, when the participation framework changed dramatically. At first there was tense negotiation about whether Father could show Sandra how to do homework.

Father did not become angry and proposed that it was possibly because she was sick that she could not do her homework. He did, however, insist on a particular form of participation, one in which both arranged their bodies so that they were looking at the book. Sandra did dramatically change her orientation, so she could attend to what her father said as well as to anything he might do on the homework pages. The affective tone then changed, and both began laughing while working on the problems.

Here we can see how mundane interactive activities such as helping with homework constitute a key site where the work of parenting, with its accompanying cognitive, social, and emotional components, is achieved in the daily round of family life. This instance shows how forms of affect may change over time as a parent holds his ground regarding standards he expects to be upheld. At first when Sandra did not comply, her father made pejorative judgments about her character. He permitted a tense encounter, one he unilaterally walked away from, to change to a situation in which the participants were joyfully laughing with each other as they worked together on the homework problems.

CONCLUSION

Across a range of activities we thus find ways that family members can work together to build forms of cooperative engagement that produce moments of intense pleasure during everyday events of their lives. In the midst of both extracurricular and unstructured leisure activities, during help with homework, and during sibling child care, we find that parents and/or sibling caretakers provide warm, supportive interactions that help their family members explore known and possible meanings of how events in the world are structured, understand feelings of being newcomers or outsiders, congratulate them for successful accomplishments, apprentice them into new activities, and guide them into new ways of approaching difficult endeavors. These activities are often overlaid with heightened forms of affect, gentle touch and smiles. Through the ways in which family members organize participation, including talk and the body, in specific, constantly changing activities, parties shape each other as moral, social and cognitive actors.

NOTES

1. Darrah 2007; Graesch 2009.

2. Larson and Richards 1994.

3. Weisner 2009.

4. M.H. Goodwin 2007.

5. Kremer-Sadlik and Paugh 2007.

6. Levey 2009.

7. Lareau 2003.

8. Zelizer 2005. For an extensive review of theories about middle-class anxiety about parents’ ability to secure their children's place in the middle class and the view of childhood as a “period of preparation” and parents’ views of “the child as a project,” see Kremer-Sadlik and Gutierrez, this volume.

9. See Kremer-Sadlik and Gutiérrez, this volume, for a description of the series of events occurring one weekday afternoon.

10. Gutiérrez, Izquierdo, and Kremer-Sadlik 2005.

11. Graesch 2009.

12. Levey 2009.

13. Van Hamersveld and Goodwin 2007.

14. Getzels and Csikszentmihalyi 1976; Ochs, Smith, and Taylor 1989.

15. Ingold 2000, 37.

16. Klein, Graesch, and Izquierdo 2009.

17. Goodwin 2006; Klein, Graesch, and Izquierdo 2009.

18. Goodwin, Cekaite, and Goodwin forthcoming.

19. Tulbert and Goodwin 2011.

20. Ochs and Taylor 1992.

21. Crowley and Jacobs 2002.

22. M.H. Goodwin 2007.

23. Fasulo, Liberati, and Pontecorvo 2002.

24. Keenan 1977; Schieffelin 1983.

25. Black 2008.

26. Fasulo, Loyd, and Padiglione 2007; M. H. Goodwin 2006; Klein, Graesch, and Izquierdo 2009.

27. Press 2003.

28. Pomerantz 1984.

29. Goodwin 2005.

30. Maynard 2002; Ochs 1988; Rabain-Jamin, Maynard, and Greenfield 2003; Schieffelin 1990; Weisner and Gallimore 1977; Weisner 1989; Zukow 1989.

31. Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo 1989; Weisner and Gallimore 1977.

32. Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo 1989.

33. Ibid., 61.

34. Weisner 1989, 11.

35. Zukow 1989, 89.

36. Ibid., 91.

37. Ibid., 90.

38. Ibid., 92, 96.

39. Ibid., 98.

40. Goodwin 2010.

41. Tulbert and Goodwin 2011.

42. Watson-Gegeo and Gegeo 1989.

43. Schieffelin 1990, 76.

44. Goodwin 2010.

45. Zukow 1989, 97.

46. Ibid., 254.

47. Goodwin 2010.

48. Ingold 2000, 37.

49. Goffman 1961.

50. C. Goodwin 2007.