One

THE NATURE OF THE PAST

“WE SAW NAKED PEOPLE,” A BROAD-SHOULDERED SEA captain from Genoa wrote in his diary, nearing land after weeks of staring at nothing but blue-black sea. Or, at least, that’s what Christopher Columbus is thought to have written in his diary that day in October 1492, ink trailing across the page like the line left behind by a snail wandering across a stretch of sand. No one knows for sure what the sea captain wrote that day, because his diary is lost. In the 1530s, before it disappeared, parts of it were copied by a frocked and tonsured Dominican friar named Bartolomé de Las Casas. The friar’s copy was lost, too, until about 1790, when an old sailor found it in the library of a Spanish duke. In 1894, the widow of another librarian sold to a duchess parchment scraps of what appeared to be Columbus’s original—it had his signature, and the year 1492 on the cover. After that, the widow disappeared, and, with her, whatever else may have been left of the original diary vanished.1

All of this is unfortunate; none of it is unusual. Most of what once existed is gone. Flesh decays, wood rots, walls fall, books burn. Nature takes one toll, malice another. History is the study of what remains, what’s left behind, which can be almost anything, so long as it survives the ravages of time and war: letters, diaries, DNA, gravestones, coins, television broadcasts, paintings, DVDs, viruses, abandoned Facebook pages, the transcripts of congressional hearings, the ruins of buildings. Some of these things are saved by chance or accident, like the one house that, as if by miracle, still stands after a hurricane razes a town. But most of what historians study survives because it was purposely kept—placed in a box and carried up to an attic, shelved in a library, stored in a museum, photographed or recorded, downloaded to a server—carefully preserved and even catalogued. All of it, together, the accidental and the intentional, this archive of the past—remains, relics, a repository of knowledge, the evidence of what came before, this inheritance—is called the historical record, and it is maddeningly uneven, asymmetrical, and unfair.

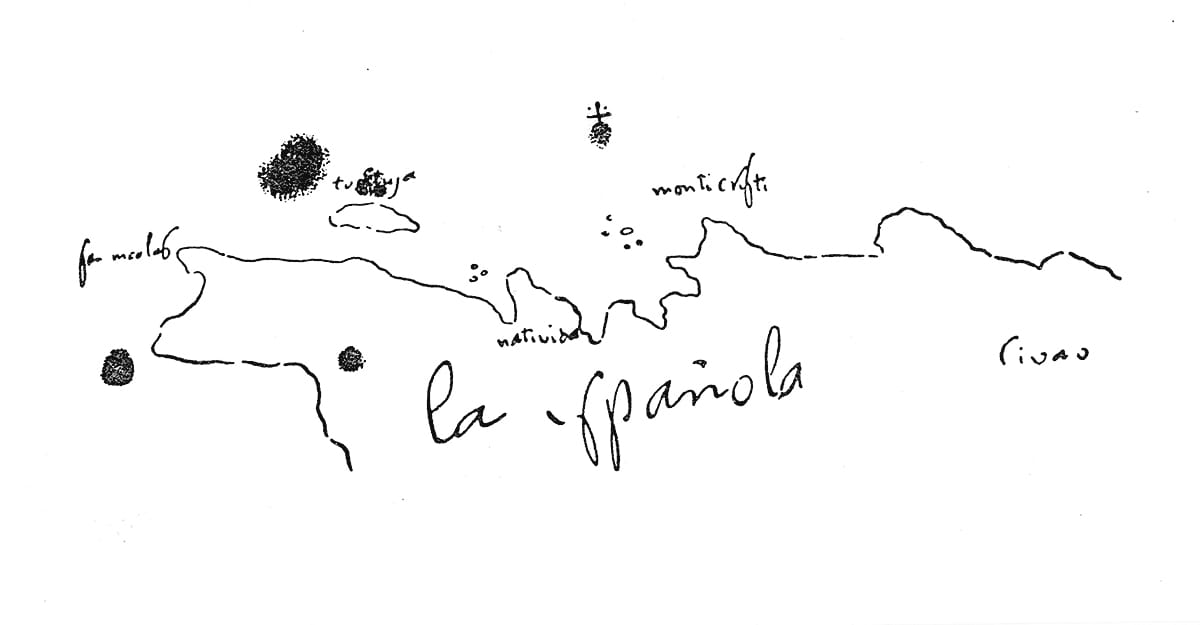

Relying on so spotty a record requires caution. Still, even its absences speak. “We saw naked people,” Columbus wrote in his diary (at least, according to the notes taken by Las Casas). “They were a people very poor in everything,” the sea captain went on, describing the people he met on an island they called Haiti—“land of mountains”—but that Columbus called Hispaniola—“the little Spanish island”—because he thought it had no name. They lacked weapons, he reported; they lacked tools. He believed they lacked even a faith: “They appear to have no religion.” They lacked guile; they lacked suspicion. “I will take six of them from here to Your Highnesses,” he wrote, addressing the king and queen of Spain, “in order that they may learn to speak,” as if, impossibly, they had no language.2 Later, he admitted the truth: “None of us understands the words they say.”3

Two months after he reached Haiti, Columbus prepared to head back to Spain but, off the coast, his three-masted flagship ran aground. Before the ship sank, Columbus’s men salvaged the timbers to build a fort; the sunken wreckage has never been found, as lost to history as everything that the people of Haiti said the day a strange sea captain washed up on shore. On the voyage home, on a smaller ship, square-rigged and swift, Columbus wondered about all that he did not understand about the people he’d met, a people he called “Indians” because he believed he had sailed to the Indies. It occurred to him that it wasn’t that they didn’t have a religion or a language but that these things were, to him, mysteries that he could not penetrate, things beyond his comprehension. He needed help. In Barcelona, he hired Ramón Pané, a priest and scholar, to come along on his next voyage, to “discover and understand . . . the beliefs and idolatries of the Indians, and . . . how they worship their gods.”4

Pané sailed with Columbus in 1493. Arriving in Haiti, Pané met a man named Guatícabanú, who knew all of the languages spoken on the island, and who learned Pané’s language, Castilian, and taught him his own. Pané lived with the natives, the Taíno, for four years, and delivered to Columbus his report, a manuscript he titled An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians. Not long afterward, it vanished.

The fates of old books are as different as the depths of the ocean. Before An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians disappeared, Columbus’s son Ferdinand, writing a biography of his father, copied it out, and even though Ferdinand Columbus’s book remained unpublished at his death in 1539, his copy of Pané’s extraordinary account had by then been copied by other scholars, including the learned and dogged Las Casas, a man who never left a page unturned. In 1570, a scholar in Venice was translating Pané’s Antiquities into Italian when he died in prison, suspected of being a spy for the French; nevertheless, his translation was published in 1571, with the result that the closest thing to the original of Pané’s account that survives is a poor Italian translation of words that had already been many times translated, from other tongues to Guatícabanú’s tongue, and from Guatícabanú’s tongue to Castilian and then, by Pané, from Castilian.5 And yet it remains a treasure.

“I wrote it down in haste and did not have sufficient paper,” Pané apologized. He’d collected the Taíno’s stories, though he’d found it difficult to make sense of them, since so many of the stories seemed, to him, to contradict one another. “Because they have neither writing nor letters,” Pané reported, “they cannot give a good account of how they have heard this from their ancestors, and therefore they do not all say the same thing.” The Taíno had no writing. But, contrary to Columbus’s initial impressions, they most certainly did have a religion. They called their god Yúcahu. “They believe that he is in heaven and is immortal, and that no one can see him, and that he has a mother,” Pané explained. “But he has no beginning.” Also, “They know likewise from whence they came, and where the sun and the moon had their beginning, and how the sea was made, and where the dead go.”6

People order their worlds with tales of their dead and of their gods and of the origins of their laws. The Taíno told Pané that their ancestors once lived in caves and would go out at night but, once, when some of them were late coming back, the Sun turned them into trees. Another time, a man named Yaya killed his son Yayael and put his bones in a gourd and hung it from his roof and when his wife took down the gourd and opened it the bones had been changed into fish and the people ate the fish but when they tried to hang the gourd up again, it fell to the earth, and out spilled all the water that made the oceans.

The Taíno did not have writing but they did have government. “They have their laws gathered in ancient songs, by which they govern themselves,” Pané reported.7 They sang their laws, and they sang their history. “These songs remain in their memory rather than in books,” another Spanish historian observed, “and this way they recite the genealogies of the caciques, kings, and lords they have had, their deeds, and the bad or good times they had.”8

In those songs, they told their truths. They told of how the days and weeks and years after the broad-shouldered sea captain first spied their island were the worst of times. Their god, Yúcahu, had once foretold that they “would enjoy their dominion for but a brief time because a clothed people would come to their land who could overcome them and kill them.”9 This had come to pass. There were about three million people on that island, land of mountains, when Columbus landed; fifty years later, there were only five hundred; everyone else had died, their songs unsung.

I.

STORIES OF ORIGINS nearly always begin in darkness, earth and water and night, black as doom. The sun and the moon came from a cave, the Taíno told Pané, and the oceans spilled out of a gourd. The Iroquois, a people of the Great Lakes, say the world began with a woman who lived on the back of a turtle. The Akan of Ghana tell a story about a god who lived closer to the earth, low in the sky, until an old woman struck him with her pestle, and he flew away. “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth,” according to Genesis. “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.”

Darkness was on the face of the deep in geological histories, too, whose evidence comes from rocks and bones. The universe was created about fourteen billion years ago, according to the traces left behind by meteors and the afterlives of stars, glowing and distant, blinking and dim. The earth was formed about four billion years ago, according to the sand and rocks, sea floors and mountaintops. For a very long time, all the lands of the earth were glommed together until, about three hundred million years ago, those glommed-together lands began breaking up; parts broke off and began drifting away from one another, like the debris of a sinking ship.

Evidence of the long-ago past is elusive, but it survives in the unlikeliest of places, even in the nests of pack rats, mammals that crept up in North America sixty million years ago. Pack rats build nests out of sticks and stones and bones and urinate on them; the liquid hardens like amber, preserving pack rat nests as if pressed behind glass. A great many of the animals and plants that lived at the time of ancient pack rats later became extinct, lost forever, saved only in pack rat nests, where their preserved remains provide evidence not only of evolution but of the warming of the earth. A pack rat nest isn’t like the geological record; it’s more like an archive, a collection, gathered and kept, like a library of old books and long-forgotten manuscripts, a treasure, an account of the antiquities of the animals and plants.10

The fossil record is richer still. Charles Darwin called the record left by fossils “a history of the world imperfectly kept.” According to that record, Homo sapiens, modern humans, evolved about three hundred thousand years ago, in East Africa, near and around what is now Ethiopia. Over the next hundred and fifty thousand years, early humans spread into the Middle East, Asia, Australia, and Europe.11 Like pack rats, humans store and keep and save. The record of early humans, however imperfectly kept, includes not only fossils but also artifacts, things created by people (the word contains its own meaning—art + fact—an artifact is a fact made by art). Artifacts and the fossil record together tell the story of how, about twenty thousand years ago, humans migrated into the Americas from Asia when, for a while, the northwestern tip of North America and the northeastern tip of Asia were attached when a landmass between them rose above sea level, making it possible for humans and animals to walk between what is now Russia and Alaska, a distance of some six hundred miles, until the water rose again, and one half of the world was, once again, cut off from the other half.

In 1492, seventy-five million people lived in the Americas, north and south.12 The people of Cahokia, the biggest city in North America, on the Mississippi floodplains, had built giant plazas and earthen mounds, some bigger than the Egyptian pyramids. In about 1000 AD, before Cahokia was abandoned, more than ten thousand people lived there. The Aztecs, Incas, and Maya, vast and ancient civilizations, built monumental cities and kept careful records and calendars of exquisite accuracy. The Aztec city of Tenochtitlán, founded in 1325, had a population of at least a quarter-million people, making it one of the largest cities in the world. Outside of those places, most people in the Americas lived in smaller settlements and gathered and hunted for their food. A good number were farmers who grew squash and corn and beans, hunted and fished. They kept pigs and chickens but not bigger animals. They spoke hundreds of languages and practiced many different faiths. Most had no written form of language. They believed in many gods and in the divinity of animals and of the earth itself.13 The Taíno lived in villages of one or two thousand people, headed by a cacique. They fished and farmed. They warred with their neighbors. They decorated their bodies; they painted themselves red. They sang their laws.14 They knew where the dead went.

In 1492, about sixty million people lived in Europe, fifteen million fewer than lived in the Americas. They lived and were ruled in villages and towns, in cities and states, in kingdoms and empires. They built magnificent cities and castles, cathedrals and temples and mosques, libraries and universities. Most people farmed and worked on land surrounded by fences, raising crops and cattle and sheep and goats. “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it,” God tells Adam and Eve in Genesis, “and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” They spoke and wrote dozens of languages. They recorded their religious tenets and stories on scrolls and in books of beauty and wonder. They were Catholic and Protestant, Jewish and Muslim; for long stretches of time, peoples of different faiths managed to get along and then, for other long stretches, they did not, as if they would cut out one another’s hearts. Their faith was their truth, the word of their God, revealed to their prophets, and, for Christians, to the people, through the words spoken by Jesus—the good-spell, or “good news”—their Gospel, written down.

Before 1492, Europe suffered from scarcity and famine. After 1492, the vast wealth carried to Europe from the Americas and extracted by the forced labor of Africans granted governments new powers that contributed to the rise of nation-states.

A nation is a people who share a common ancestry. A state is a political community, governed by laws. A nation-state is a political community, governed by laws, that, at least theoretically, unites a people who share a common ancestry (one way nation-states form is by violently purging their populations of people with different ancestries). As nation-states emerged, they needed to explain themselves, which they did by telling stories about their origins, tying together ribbons of myths, as if everyone in the “English nation,” for instance, had the same ancestors, when, of course, they did not. Very often, histories of nation-states are little more than myths that hide the seams that stitch the nation to the state.15

The origins of the United States can be found in those seams. When the United States declared its independence in 1776, plainly, it was a state, but what made it a nation? The fiction that its people shared a common ancestry was absurd on its face; they came from all over, and, having waged a war against England, the very last thing they wanted to celebrate was their Englishness. In an attempt to solve this problem, the earliest historians of the United States decided to begin their accounts with Columbus’s voyage, stitching 1776 to 1492. George Bancroft published his History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent to the Present in 1834, when the nation was barely more than a half-century old, a fledgling, just hatched. By beginning with Columbus, Bancroft made the United States nearly three centuries older than it was, a many-feathered old bird. Bancroft wasn’t only a historian; he was also a politician: he served in the administrations of three U.S. presidents, including as secretary of war during the age of American expansion. He believed in manifest destiny, the idea that the United States was fated to cross the continent, from east to west. For Bancroft, the nation’s fate was all but sealed the day Columbus set sail. By giving Americans a more ancient past, he hoped to make America’s founding appear inevitable and its growth inexorable, God-ordained. He also wanted to celebrate the United States, not as an offshoot of England, but instead as a pluralist and cosmopolitan nation, with ancestors all over the world. “France contributed to its independence,” he observed, “the origin of the language we speak carries us to India; our religion is from Palestine; of the hymns sung in our churches, some were first heard in Italy, some in the deserts of Arabia, some on the banks of the Euphrates; our arts come from Greece; our jurisprudence from Rome.”16

Yet the origins of the United States date to 1492 for another, more troubling reason: the nation’s founding truths were forged in a crucible of violence, the products of staggering cruelty, conquest and slaughter, the assassination of worlds. The history of the United States can be said to begin in 1492 because the idea of equality came out of a resolute rejection of the idea of inequality; a dedication to liberty emerged out of bitter protest against slavery; and the right to self-government was fought for, by sword and, still more fiercely, by pen. Against conquest, slaughter, and slavery came the urgent and abiding question, “By what right?”

To begin a history of the United States in 1492 is to take seriously and solemnly the idea of America itself as a beginning. Yet, so far from the nation’s founding having been inevitable, its expansion inexorable, the history of the United States, like all history, is a near chaos of contingencies and accidents, of wonders and horrors, unlikely, improbable, and astonishing.

To start with, weighing the evidence, it’s a little surprising that it was western Europeans in 1492, and not some other group of people, some other year, who crossed an ocean to discover a lost world. Making the journey required knowledge, capacity, and interest. The Maya, whose territory stretched from what is now Mexico to Costa Rica, knew enough astronomy to navigate across the ocean as early as AD 300. They did not, however, have seaworthy boats. The ancient Greeks had known a great deal about cartography: Claudius Ptolemy, an astronomer who lived in the second century, had devised a way to project the surface of the globe onto a flat surface with near-perfect proportions. But medieval Christians, having dismissed the writings of the ancient Greeks as pagan, had lost much of that knowledge. The Chinese had invented the compass in the eleventh century, and had excellent boats. Before his death in 1433, Zheng He, a Chinese Muslim, had explored the coast of much of Asia and eastern Africa, leading two hundred ships and twenty-seven thousand sailors. But China was the richest country in the world, and by the late fifteenth century no longer allowed travel beyond the Indian Ocean, on the theory that the rest of the world was unworthy and uninteresting. West Africans navigated the coastline and rivers that led into a vast inland trade network, but prevailing winds and currents thwarted them from navigating north and they seldom ventured into the ocean. Muslims from North Africa and the Middle East, who had never cast aside the knowledge of antiquity and the calculations of Ptolemy, made accurate maps and built sturdy boats, but because they dominated trade in the Mediterranean Sea, as well as overland trade with Africa, for gold, and with Asia, for spices, they didn’t have much reason to venture farther.17

It was somewhat out of desperation, then, that the poorest and weakest Christian monarchs on the very western edge of Europe, fighting with Muslims, jealous of the Islamic world’s monopoly on trade, and keen to spread their religion, began looking for routes to Africa and Asia that wouldn’t require sailing across the Mediterranean. In the middle of the fifteenth century, Prince Henry of Portugal began sending ships to sail along the western coast of Africa. Building forts on the coast and founding colonies on islands, they began to trade with African merchants, buying and selling people, coin for flesh, a traffic in slaves.

Columbus, a citizen of the bustling Mediterranean port of Genoa, served as a sailor on Portuguese slave-trading ships beginning in 1482. In 1484, when he was about thirty-three years old, he presented to the king of Portugal a plan to travel to Asia by sailing west, across the ocean. The king assembled a panel of scholars to consider the proposal but, in the end, rejected it: Portugal was committed to its ventures in West Africa, and the king’s scholars saw that Columbus had greatly underestimated the distance he would have to travel. Better calculated was the voyage of Bartolomeu Dias, a Portuguese nobleman, who in 1487 rounded the southernmost tip of Africa, proving that it was possible to sail from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Why sail west, across the Atlantic, when a different way to sail to the East had already been found?

Columbus next brought his proposal to the king and queen of Spain, who at first rejected it; they were busy waging wars of religion, purging their population of people who had different ancestors and different beliefs. Early in 1492, after the last Muslim city in Spain fell to the Spanish crown, Ferdinand and Isabella ordered that all Jews be expelled from their realm and, confident that their pitiless Inquisition had rid their kingdom of Muslims and Jews, heretics and pagans, they ordered Columbus to sail, to trade, and to spread the Christian faith: to conquer, and to chronicle, to say what was true, and to write it down: to keep a diary.

TO WRITE SOMETHING down doesn’t make it true. But the history of truth is lashed to the history of writing like a mast to a sail. Writing was invented in three different parts of the world at three different moments in time: about 3200 BCE in Mesopotamia, about 1100 BCE in China, and about AD 600 in Mesoamerica. In the history of the world, most of the people who have ever lived either did not know how to write or, if they did, left no writing behind, which is among the reasons why the historical record is so maddeningly unfair. To write something down is to make a fossil record of a mind. Stories are full of power and force; they seethe with meaning, with truths and lies, evasions and honesty. Speech often has far more weight and urgency than writing. But most words, once spoken, are forgotten, while writing lasts, a point observed early in the seventeenth century by an English vicar named Samuel Purchas. Purchas, who had never been more than two hundred miles from his vicarage, carefully studied the accounts of travelers, because he proposed to write a new history of the world.18 Taking stock of all the differences between the peoples of all ages and places, across continents and centuries, Purchas was most struck by what he called the “literall advantage”: the significance of writing. “By writing,” he wrote, “Man seems immortall.”19

A new chapter in the history of truth—foundational to the idea of truth on which the United States would one day stake and declare its independence—began on Columbus’s first voyage. If any man in history had a “literall advantage,” that man was Christopher Columbus. In Haiti in October 1492, under a scorching sun, with two of his captains as witnesses, Columbus (according to the notes taken by Las Casas) declared that “he would take, as in fact he did take, possession of the said island for the king and for the queen his lords.” And then he wrote that down.20

This act was both new and strange. Marco Polo, traveling through the East in the thirteenth century, had not claimed China for Venice; nor did Sir John Mandeville, traveling through the Middle East in the fourteenth century, attempt to take possession of Persia, Syria, or Ethiopia. Columbus had read Marco Polo’s Travels and Mandeville’s Travels; he seems to have brought those books with him when he sailed.21 Unlike Polo and Mandeville, Columbus did not make a catalogue of the ways and beliefs of the people he met (only later did he hire Pané to do that). Instead, he decided that the people he met had no ways and beliefs. Every difference he saw as an absence.22 Insisting that they had no faith and no civil government and were therefore infidels and savages who could not rightfully own anything, he claimed possession of their land, by the act of writing. They were a people without truth; he would make his truth theirs. He would tell them where the dead go.

Columbus had this difference from Marco Polo and Mandeville, too: he made his voyages not long after Johannes Gutenberg, a German blacksmith, invented the printing press. Printing accelerated the diffusion of knowledge and broadened the historical record: things that are printed are much more likely to last than things that are merely written down, since printing produces many copies. The two men were often paired. “Two things which I always thought could be compared, not only to Antiquity, but to immortality,” wrote one sixteenth-century French philosopher, are “the invention of the printing press and the discovery of the new world.”23 Columbus widened the world, Gutenberg made it spin faster.

But Columbus himself did not consider the lands he’d visited to be a new world. He thought only that he’d found a new route to the old world. Instead, it was Amerigo Vespucci, the venturesome son of a notary from Florence, Italy, who crossed the ocean in 1503 and wrote, about the lands he found, “These we may rightly call a new world.” The report Vespucci brought home was soon published as a book called Mundus Novus, translated into eight languages and published in sixty different editions. What Vespucci reported discovering was rather difficult to believe. “I have found a continent more densely peopled and abounding in animals than our Europe or Asia or Africa,” he wrote.24 It seemed a Garden of Eden, a place only ever before imagined. In 1516, Thomas More, a counselor to England’s king, Henry VIII, published a fictional account of a Portuguese sailor on one of Vespucci’s ships who had traveled just a bit farther, to an island where he found a perfect republic, named Utopia (literally, no place)—the island of nowhere.25

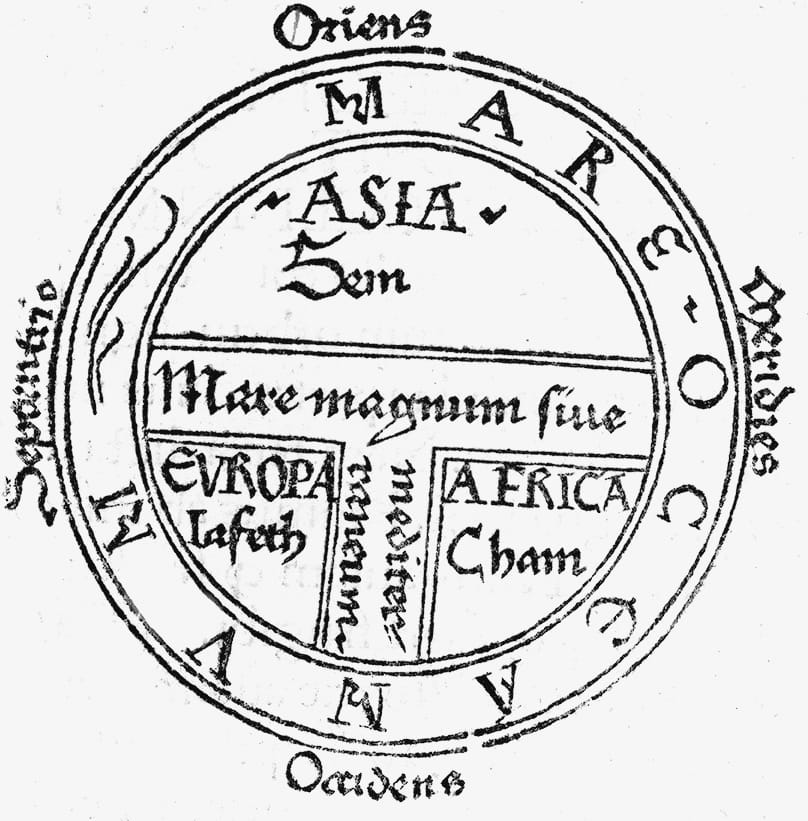

What did it mean to find someplace where nowhere was supposed to be? The world had long seemed to consist of three parts. In the seventh century, the Archbishop Isidore of Seville, writing an encyclopedia called the Etymologiae that circulated widely in manuscript—as many as a thousand handwritten copies survive—had drawn the world as a circle surrounded by oceans and divided by seas into three bodies of land, Asia, Europe, and Africa, inhabited by the descendants of the three sons of Noah: Shem, Japheth, and Ham. In 1472, Etymologiae became one of the very first books ever to be set in type and the archbishop’s map became the first world map ever printed.26 Twenty years later, it was obsolete.

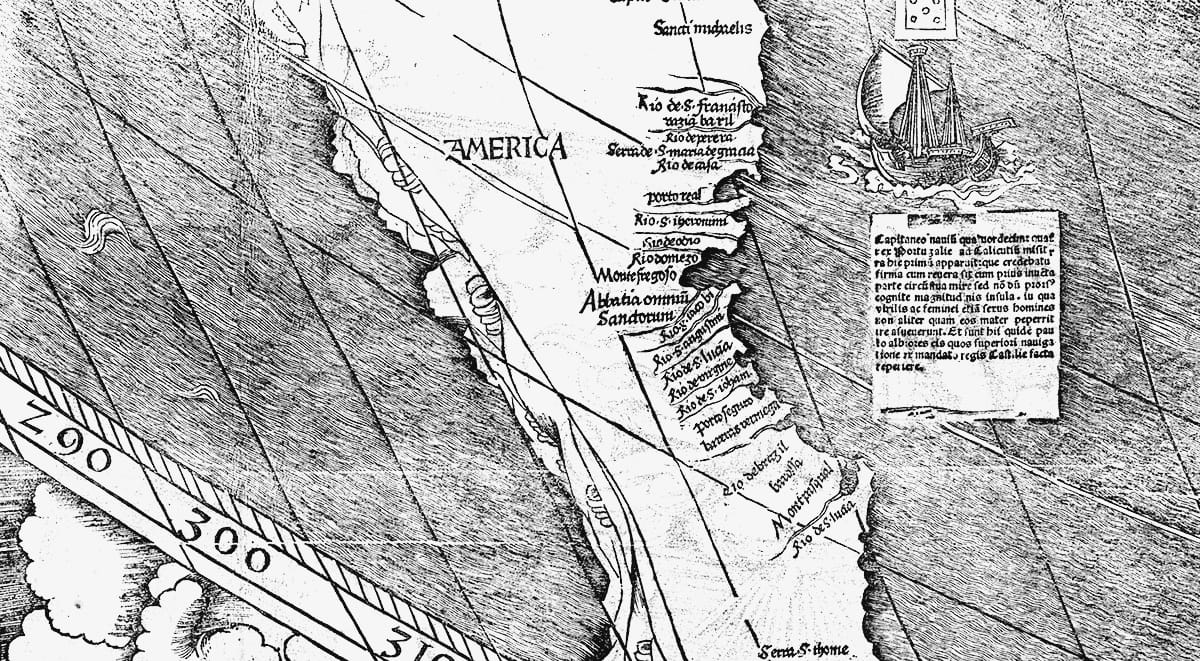

Discovering that nowhere was somewhere meant work for mapmakers, another kind of writing that made claims of truth and possession. In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller, a German cartographer living in northern France who had in his hands a French translation of Mundus Novus, carved onto twelve woodblocks a new map of the world, a Universalis Cosmographia, and printed more than a thousand copies. People pasted the twelve prints together and mounted them like wallpaper to make a giant map, four feet high by eight feet wide. Wallpaper fades and falls apart: only a single copy of Waldseemüller’s map survives. But one word on that long-lost map has lasted longer than anything else Waldseemüller ever wrote. With a nod to Vespucci, Waldseemüller, inventing a word, gave the fourth part of the world, that unknown utopia, a name: he labeled it “America.”27

This name stuck by the merest accident. Much else did not last. The Taíno story about the cave, the Iroquois story about the turtle, the Akan story about the old woman with the pestle, the Old Testament story of Adam and Eve—these stories would be unknown, or hardly known, if they hadn’t been written down or recorded. That they lasted mattered. Modernity began when people fighting over which of these stories was true began to think differently about the nature of truth, about the nature of the past, and about the nature of rule.

II.

IN 1493, WHEN COLUMBUS returned from his unimaginable voyage, a Spanish-born pope granted all of the lands on the other side of the ocean, everything west of a line of longitude some three hundred miles west of Cape Verde, to Spain, and granted what lay east of that line, western Africa, to Portugal, the pope claiming the authority to divvy up lands inhabited by tens of millions of people as if he were the god of Genesis. Unsurprisingly, the heads of England, France, and the Netherlands found this papal pronouncement absurd. “The sun shines for me as for the others,” said the king of France. “I should like to see the clause of Adam’s will which excludes me from a share of the world.”28 Nor did Spain’s claim go uncontested on the other side of the world. A Taíno man told Guatícabanú that the Spanish “were wicked and had taken their land by force.”29 Guatícabanú told that to Ramón Pané, who wrote it down. Ferdinand Columbus copied that out. And so did a scholar in a prison in Venice. It was as if that Taíno man had taken down from his roof a gourd full of the bones of his son and opened it, spilling out an ocean of ideas. The work of conquest involved pretending that ocean could be poured back into that gourd.

An ocean of ideas not fitting into a gourd, people in both Europe and the Americas groped for meaning and wondered how to account for difference and sameness. They asked new questions, and they asked old questions more sharply: Are all peoples one? And if they are, by what right can one people take the land of another or their labor or, even, their lives?

Any historical reckoning with these questions begins with counting and measuring. Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas; they carried twelve million Africans there by force; and as many as fifty million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease.30 Europe is spread over about four million square miles, the Americas over about twenty million square miles. For centuries, geography had constrained Europe’s demographic and economic growth; that era came to a close when Europeans claimed lands five times the size of Europe. Taking possession of the Americas gave Europeans a surplus of land; it ended famine and led to four centuries of economic growth, growth without precedent, growth many Europeans understood as evidence of the grace of God. One Spaniard, writing from New Spain to his brother in Valladolid in 1592, told him, “This land is as good as ours, for God has given us more here than there, and we shall be better off.”31 Even the poor prospered.

The European extraction of the wealth of the Americas made possible the rise of capitalism: new forms of trade, investment, and profit. Between 1500 and 1600 alone, Europeans recorded carrying back to Europe from the Americas nearly two hundred tons of gold and sixteen thousand tons of silver; much more traveled as contraband. “The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind,” Adam Smith wrote, in The Wealth of Nations, in 1776. But the voyages of Columbus and Dias also marked a turning point in the development of another economic system, slavery: the wealth of the Americas flowed to Europe by the forced labor of Africans.32

Slavery had been practiced in many parts of the world for centuries. People tended to enslave their enemies, people they considered different enough from themselves to condemn to lifelong servitude. Sometimes, though not often, the status of slaves was heritable: the children of slaves were condemned to a life of slavery, too. Many wars had to do with religion, and because many slaves were prisoners of war, slaves and their owners tended to be people of different faiths: Christians enslaved Jews; Muslims enslaved Christians; Christians enslaved Muslims. Since the Middle Ages, Muslim traders from North Africa had traded in Africans from below the Sahara, where slavery was widespread. In much of Africa, labor, not land, constituted the sole form of property recognized by law, a form of consolidating wealth and generating revenue, which meant that African states tended to be small and that, while European wars were fought for land, African wars were fought for labor. People captured in African wars were bought and sold in large markets by merchants and local officials and kings and, beginning in the 1450s, by Portuguese sea captains.33

Columbus, a veteran of that trade, reported to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492 that it would be the work of a moment to enslave the people of Haiti, since “with 50 men all of them could be held in subjection and can be made to do whatever one might wish.”34 In sugar mines and gold mines, the Spanish worked their native slaves to death while many more died of disease. Soon, they turned to another source of forced labor, Africans traded by the Portuguese.

Counting and keeping accounts on the cargo of every ship, Europeans found themselves puzzled by an extraordinary asymmetry. People moved from Europe and Africa to the Americas; wealth moved from the Americas to Europe; and animals and plants moved from Europe to the Americas. But very few people or animals or plants moved from the Americas to Europe or Africa, at least not successfully. “It appears as if some invisible barrier existed preventing passage Eastward, though allowing it Westward,” a later botanist wrote.35 The one-way migration of people made self-evident sense: people controlled the ships and they carried far more people west than east, bringing soldiers and missionaries, settlers and slaves. But the one-way migration of animals and plants was, for centuries, until the late nineteenth-century age of Darwin and the germ theory of disease, altogether baffling, explained only by faith in divine providence: Christians took it as a sign that their conquest was ordained by God.

The signs came in abundance. When Columbus made a second voyage across the ocean in 1493, he commanded a fleet of seventeen ships carrying twelve hundred men, and another kind of army, too: seeds and cuttings of wheat, chickpeas, melons, onions, radishes, greens, grapevines, and sugar cane, and horses, pigs, cattle, chickens, sheep, and goats, male and female, two by two. Hidden among the men and the plants and the animals were stowaways, seeds stuck to animal skins or clinging to the folds of cloaks and blankets, in clods of mud. Most of these were the seeds of plants Europeans considered to be weeds, like bluegrass, daisies, thistle, nettles, ferns, and dandelions. Weeds grow best in disturbed soil, and nothing disturbs soil better than an army of men, razing forests for timber and fuel and turning up the ground cover with their boots, and the hooves of their horses and oxen and cattle. Livestock eat grass; people eat livestock: livestock turn grass into food that humans can eat. The animals that Europeans brought to the New World—cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, chickens, and horses—had no natural predators in the Americas but they did have an abundant food supply. They reproduced in numbers unfathomable in Europe. Cattle populations doubled every fifteen months. Nothing, though, beat the pigs. Pigs convert one-fifth of everything they eat into food for human consumption (cattle, by contrast, convert one-twentieth); they feed themselves, by foraging, and they have litters of ten or more. Within a few years of Columbus’s second voyage, the eight pigs he brought with him had descendants numbering in the thousands. Wrote one observer, “All the mountains swarmed with them.”36

Meanwhile, the people of the New World: They died by the hundreds. They died by the thousands, by the tens of thousands, by the hundreds of thousands, by the tens of millions. The isolation of the Americas from the rest of the world, for hundreds of millions of years, meant that diseases to which Europeans and Africans had built up immunities over millennia were entirely new to the native peoples of the Americas. European ships, with their fleets of people and animals and plants, brought along, unseen, battalions of diseases: smallpox, measles, diphtheria, trachoma, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, malaria, typhoid fever, yellow fever, dengue fever, scarlet fever, amoebic dysentery, and influenza, diseases that had evolved alongside humans and their domesticated animals living in dense, settled populations—cities—where human and animal waste breeds vermin, like mice and rats and roaches. Most of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, though, didn’t live in dense settlements, and even those who lived in villages tended to move with the seasons, taking apart their towns and rebuilding them somewhere else. They didn’t accumulate filth, and they didn’t live in crowds. They suffered from very few infectious diseases. Europeans, exposed to these diseases for thousands of years, had developed vigorous immune systems, and antibodies particular to bacteria to which no one in the New World had ever been exposed.

The consequence was catastrophe. Of one hundred people exposed to the smallpox virus for the first time, nearly one hundred became infected, and twenty-five to thirty-three died. Before they died, they exposed many more people: smallpox incubates for ten to fourteen days, which meant that people who didn’t yet feel sick tended to flee, carrying the disease as far as they could go before collapsing. Some people who were infected with smallpox could have recovered, if they’d been taken care of, but when one out of every three people was sick, and a lot of people ran, there was no one left to nurse the sick, who died of thirst and grief and of being alone.37 And they died, too, of torture: already weakened by disease, they were worked to death, and starved to death. On the islands in the Caribbean, so many natives died so quickly that Spaniards decided very early on to conquer more territory, partly to take more prisoners to work in their gold and silver mines, as slaves.

Spanish conquistadors first set foot on the North American mainland in 1513; in a matter of decades, New Spain spanned not only all of what became Mexico but also more than half of what became the continental United States, territory that stretched, east to west, from Florida to California, and as far north as Virginia on the Atlantic Ocean and Canada on the Pacific.38 Diseases spread ahead of the Spanish invaders, laying waste to wide swaths of the continent. It became commonplace, inevitable, even, first among the Spanish, and then, in turn, among the French, the Dutch, and the English, to see their own prosperity and good health and the terrible sicknesses suffered by the natives as signs from God. “Touching these savages, there is a thing that I cannot omit to remark to you,” one French settler wrote: “it appears visibly that God wishes that they yield their place to new peoples.” Death convinced them at once of their right and of the truth of their faith. “The natives, they are all dead of small Poxe,” John Winthrop wrote when he arrived in New England in 1630: “the Lord hathe cleared our title to what we possess.”39

Europeans craved these omens from their God, because otherwise their title to the land and their right to enslave had little foundation in the laws of men. Often, this gave them pause. In 1504, the king of Spain assembled a group of scholars and lawyers to provide him with guidance about whether the conquest “was in agreement with human and divine law.” The debate turned on two questions: Did the natives own their own land (that is, did they possess “dominion”), and could they rule themselves (that is, did they possess “sovereignty”)? To answer these questions, the king’s advisers turned to the philosophy of antiquity.

Under Roman law, government exists to manage relations of property, the king’s ministers argued, and since, according to Columbus, the natives had no government, they had no property, and therefore no dominion. Regarding sovereignty, the king’s ministers turned to Aristotle’s Politics. “That some should rule and others be ruled is a thing not only necessary, but expedient,” Aristotle had written. “From the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule.” All relations are relations of hierarchy, according to Aristotle; the soul rules over the body, men over animals, males over females, and masters over slaves. Slavery, for Aristotle, was not a matter of law but a matter of nature: “he who is by nature not his own but another’s man, is by nature a slave; and he may be said to be another’s man who, being a human being, is also a possession.” Those who are by nature possessions are those who have a lesser capacity for reason; these people “are by nature slaves,” Aristotle wrote, “and it is better for them as for all inferiors that they should be under the rule of a master.”40

The king was satisfied: the natives did not own their land and were, by nature, slaves. The conquest continued. But across the ocean, a trumpet of protest was sounded from a pulpit. In December 1511, on the fourth Sunday of Advent, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican priest, delivered a sermon in a church on Hispaniola. Disagreeing with the king’s ministers, he said the conquistadors were committing unspeakable crimes. “Tell me, by what right or justice do you hold these Indians in such cruel and horrible slavery? By what right do you wage such detestable wars on these people who lived mildly and peacefully in their own lands, where you have consumed infinite numbers of them with unheard of murders and desolations?” And then he asked, “Are they not men?”41

Out of this protest came a disquieting decision, in 1513: the conquistadors would be required to read aloud to anyone they proposed to conquer and enslave a document called the Requerimiento. It is, in brief, a history of the world, from creation to conquest, a story of origins as justification for violence.

“The Lord our God, Living and Eternal, created the Heaven and the Earth, and one man and one woman, of whom you and we, all the men of the world, were and are descendants, and all those who come after us,” it begins. It asks that any people to whom it was read “acknowledge the Church as the Ruler and Superior of the whole world, and the high priest called Pope, and in his name the King and Queen.” If the natives accepted the story of Genesis and the claim that these distant rulers had a right to rule them, the Spanish promised, “We in their name shall receive you in all love and charity, and shall leave you your wives, and your children, and your lands, free without servitude.” But if the natives rejected these truths, the Spanish warned, “we shall forcibly enter into your country, and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their Highnesses; we shall take you and your wives and your children, and shall make slaves of them.”42

With the Requerimiento in hand, with its promises of love and charity and its threats of annihilation and devastation, the Spanish marched across the North American continent. In 1519, determined to ride to glory, Hernán Cortés, mayor of Santiago, Cuba, led six hundred Spaniards and more than a thousand native allies thundering across the land with fifteen cannons. In Mexico, he captured Tenochtitlán, a city said to have been grander than Paris or Rome, and destroyed it without pity or mercy. His men burned the Aztec libraries, their books of songs, their histories written down, a desolation described in a handful of surviving icnocuicatl, songs of their sorrow. One begins,

Broken spears lie in the roads;

we have torn our hair in our grief.

The houses are roofless now, and their walls

are red with blood.43

In 1540, a young nobleman named Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led an army of Spaniards who were crossing the continent in search of a fabled city of gold. In what is now New Mexico, they found a hive of baked-clay apartment houses, the kind of town the Spanish took to calling a pueblo. Dutifully, Coronado had the Requerimiento read aloud. The Zuni listened to a man speaking a language they could not possibly understand. “They wore coats of iron, and warbonnets of metal, and carried for weapons short canes that spit fire and made thunder,” the Zuni later said about Coronado’s men. Zuni warriors poured cornmeal on the ground, and motioned to the Spanish they dare not cross that line. A battle began. The Zuni, fighting with arrows, were routed by the Spaniards, who fought with guns.44

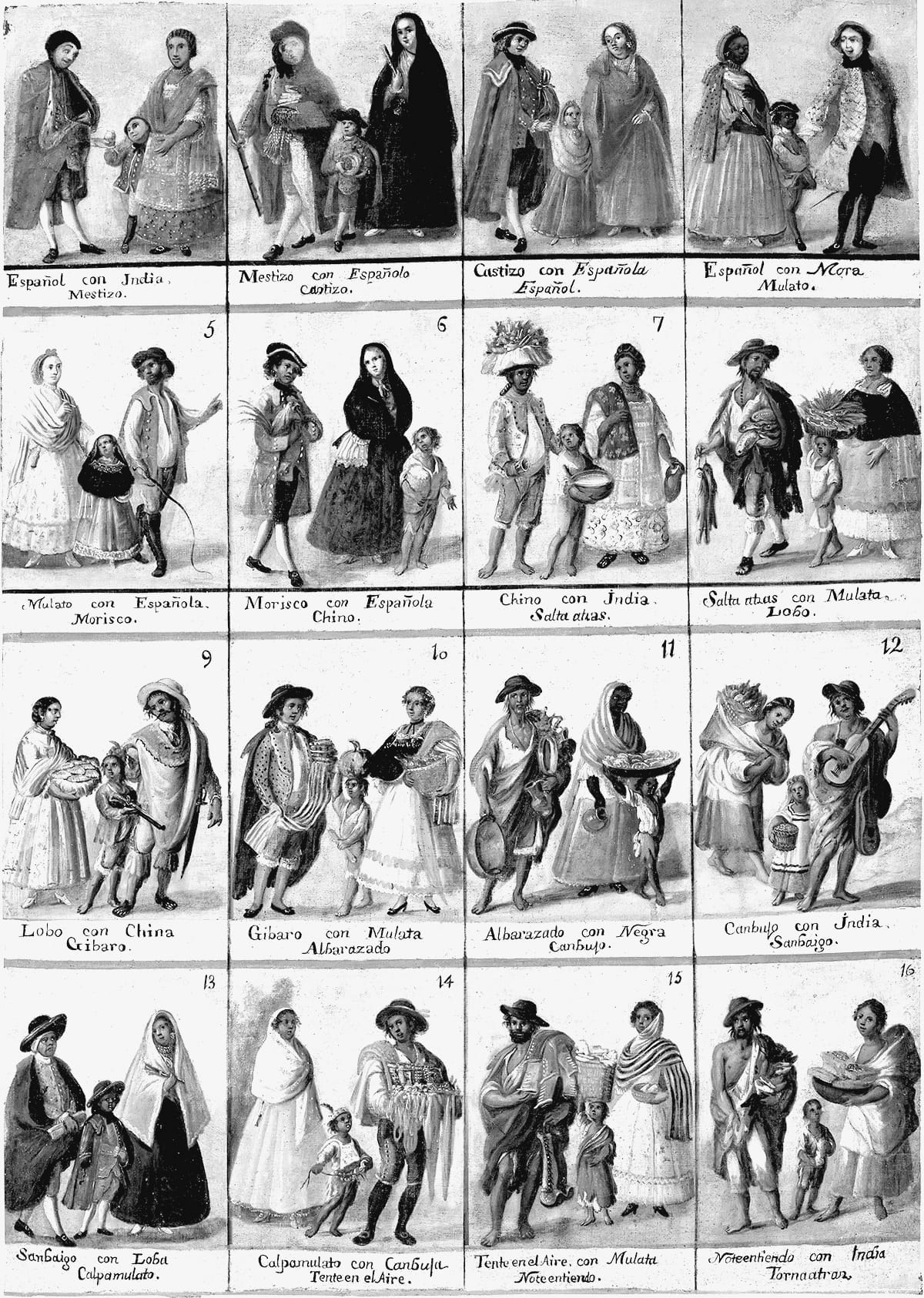

The conquest raged on, and so did the debate, even as the lines between the peoples of the Americas, Africa, and Europe blurred. The Spanish, unlike later English colonizers, did not travel to the New World in families, or even with women: they came as armies of men. They seized and raped women and they loved and married them and raised families together. La Malinche, a Nahua woman who was given to Cortés as a slave and who became his interpreter, had a son with him, born about 1523, the freighted symbol of a fateful union. In much of New Spain, the mixed-race children of Spanish men and Indian women, known as mestizos, outnumbered Indians; an intricate caste system marked gradations of skin color, mixtures of Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans, as if skin color were like dyes made of plants, the yellow of sassafras, the red of beets, the black of carob. Later, the English would recognize only black and white, a fantasy of stark and impossible difference, of nights without twilight and days without dawns. And yet both regimes of race, a culture of mixing or a culture of pretending not to mix, pressed upon the brows of every person of the least curiosity the question of common humanity: Are all peoples one?

Bartolomé de Las Casas had been in Hispaniola as a settler in 1511, when Montesinos had preached and asked, “Are they not men?” Stirred, he’d given up his slaves and become a priest and a scholar, a historian of the conquest, which is what led him, later, to copy parts of Columbus’s diary and Pané’s Antiquities. In 1542, Las Casas wrote a book called Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias, history not as justification but as a cry of conscience. With the zeal of a man burdened by his own guilt, he asked, “What man of sound mind will approve a war against men who are harmless, ignorant, gentle temperate, unarmed, and destitute of every human defense?”45 Eight years later, a new Spanish king summoned Las Casas and other scholars to his court in the clay-roofed city of Valladolid for another debate. Were the native peoples of the New World barbarians who had violated the laws of nature by, for instance, engaging in cannibalism, in which case it was lawful to wage war against them? Or were they innocent of these violations, in which case the war was unlawful?

Las Casas argued that the conquest was unlawful, insisting that charges of cannibalism were “sheer fables and shameless nonsense.” The opposing argument was made by Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, Spain’s royal historian, who had never been to the New World. A translator of Aristotle, Sepúlveda cited Aristotle’s theory of natural slavery. He said that the difference between the natives and the Spaniards was as great as that “between apes and men.” He asked, “How are we to doubt that these people, so uncultivated, so barbarous, and so contaminated with such impiety and lewdness, have not been justly conquered?”46

The judges, divided, failed to issue a decision. The conquest continued. Broken spears clattered to the ground and the walls ran red with blood.

III.

TO ALL OF THIS, the English came remarkably late. The Spanish had settled at Saint Augustine, Florida, in 1565 and by 1607 were settling the adobe town of Santa Fe, nearly two thousand miles away. The French, who made their first voyages in 1534, were by 1608 building what would become the stone city of Quebec, a castle on a hill. The English sent John Cabot across the Atlantic in 1497, but he disappeared on his return voyage, never to be seen again, and the English gave barely any thought to sending anyone after him. The word “colony” didn’t even enter the English language until the 1550s. And although England chartered trading companies—the Muscovy Company in 1555, the Turkey Company, in 1581, and the East India Company, in 1600—all looked eastward, not westward. About America, England hesitated.

In 1584, Elizabeth, the fierce and determined queen of England, asked one of her shrewdest ministers, Richard Hakluyt, whether she ought to found her own colonies in the Americas. She had in mind the Spanish and their idolatries, and their cruelties, and their vast riches, and their tyranny. By the time Elizabeth began staring west across the ocean, Las Casas’s pained history of the conquest had long since been translated into English, lavishly illustrated with engravings of atrocities, often under the title Spanish Cruelties and, later, as The Tears of the Indians. The English had come to believe—as an article of faith, as a matter of belonging to the “English nation”—that they were nobler than the Spanish: more just, wiser, gentler, and dedicated to liberty. “The Spaniards governe in the Indies with all pride and tyranie,” Hakluyt reminded his queen, and, as with any people who are made slaves, the natives “all yell and crye with one voice Liberta, liberta.”47 England could deliver them.

England’s notion of itself as a land of liberty was the story of the English nation stitched to the story of the English state. The Spanish were Catholic, but, while conquistadors had been building a New Spain, the English had become Protestant. In the 1530s, Henry VIII had established the Church of England, defiantly separate from the Church of Rome. Occupied with religious and domestic affairs, England had been altogether tentative in venturing forth to the New World. When Henry VIII died, in 1547, his son Edward became king, but by 1552, Edward was mortally ill. Hoping to avoid the ascension of his half-sister Mary, who was a Catholic, Edward named as his successor his cousin Lady Jane Grey. But when Edward died, Mary seized power, had Jane beheaded, and became the first ruling queen of England. She attempted to restore Catholicism and persecuted religious dissenters, nearly three hundred of whom were burned at the stake. Protestants who opposed her rule on religious grounds decided to argue that she had no right to reign because she was a woman, claiming that for the weak to govern the strong was “the subversion of good order.” Another of Mary’s Protestant critics complained that her reign was a punishment from God, who “haste set to rule over us an woman whom nature hath formed to be in subjeccion unto man.” Mary’s Catholic defenders, meanwhile, argued that, politically speaking, Mary was a man, “the Prince female.”

When Mary died, in 1558, Elizabeth, a Protestant, succeeded her, and Mary’s supporters, who tried to argue against Elizabeth’s right to rule, were left to battle against their own earlier arguments: they couldn’t very well argue that Elizabeth couldn’t rule because she was a woman, when they had earlier insisted that her sex did not bar Mary from the throne. The debate moved to new terrain, and clarified a number of English ideas about the nature of rule. Elizabeth’s best defender argued that if God decided “the female should rule and govern,” it didn’t matter that women were “weake in nature, feable in bodie, softe in courage,” because God would make every right ruler strong. In any case, England’s constitution abided by a “rule mixte,” in which the authority of the monarch was checked by the power of Parliament; also, “it is not she that ruleth but the lawes.” Elizabeth herself called on yet another authority: the favor of the people.48 A mixed constitution, the rule of law, the will of the people: these were English ideas that Americans would one day make their own, crying, “Liberty!”

Elizabeth eyed Spain, which had been warring with England, France, and a rebelling Netherlands (the Dutch did not achieve independence from Spain until 1609). She set out to fight Spain on every field. On the question of founding colonies in the Americas, Hakluyt submitted to Elizabeth a report that he titled “A particular discourse concerning the greate necessitie and manifold comodyties that are like to growe to this Realme of Englande by the Western discoveries lately attempted.” How much the queen was animated by animosity to Spain is nicely illustrated in the title of a report submitted to her at the very same time by another adviser: a “Discourse how Her Majesty may annoy the King of Spain.”49

Hakluyt believed the time had come for England to do more than attack Spanish ships. Establishing colonies “will be greately for the inlargement of the gospell of Christe,” he promised, and “will yelde unto us all the commodities of Europe, Affrica, and Asia.” And if the queen of England were to plant colonies in the New World, word would soon spread that the English “use the natural people there with all humanitie, curtesie, and freedome,” and the natives would “yielde themselves to her government and revolte cleane from the Spaniarde.”50 England would prosper; Protestantism would conquer Catholicism; liberty would conquer tyranny.

Elizabeth was unpersuaded. She was also distracted. In 1584, she’d expelled the Spanish ambassador after discovering a Spanish plot to invade England by way of Scotland. She liked the idea of an English foothold in the New World, but she didn’t want the Crown to cover the cost. She decided to issue a royal patent—a license—to one of her favorite courtiers, the dashing Walter Ralegh, writer, poet, and spy, granting him the right to land in North America south of a place called Newfoundland: A new-found-land, a new world, a utopia, a once-nowhere.

Ralegh was an adventurer, a man of action, but he was also a man of letters. Newly knighted, he launched an expedition in 1584. He did not sail himself but sent out a fleet of seven ships and six hundred men, providing them with a copy of Las Casas’s “book of Spanish crueltyes with fayr pictures,” to be used to convince the natives that the English, unlike the Spanish, were men of mercy and love, liberty and charity. Ralegh may well also have sent along with his expedition a copy of a new book of essays by the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne. Like William Shakespeare, Ralegh was deeply influenced by Montaigne, whose 1580 essay “Of Cannibals” testifies to how, in one of the more startling ironies in the history of humanity, the very violence that characterized the meeting between one half of the world and the other, which sowed so much destruction, also carried within it the seeds of something else.51

“Barbarians are no more marvelous to us than we are to them, nor for better cause,” Montaigne wrote. “Each man calls barbarism whatever is not his own practice.”52 They are to us as we are to them, each true: out of two truths, one.

Ralegh’s men made landfall on an island on the Outer Banks of what is now North Carolina, sweeping beaches edged with seagrass and stands of pine trees and palms. The ships sailed away, leaving behind 104 men with very little by way of supplies; the supply ship had been damaged, nearly running aground on the shoals. The site had been chosen because it was well hidden and difficult to reach. It may have been a good hideout for pirates, but it was a terrible place to build a colony. The settlers planned to wait out the winter, awaiting supplies they hoped would arrive in the spring. Meanwhile, they intended to look for gold and for a safer, deeper harbor. They built a fort, surrounded by palisades. They aimed its guns out over the wide water, believing their enemy to be Spain. They built houses outside the protection of the fort. They had very little idea that the people who already lived in the Outer Banks might pose a danger to them.

They sent home glowing reports of a land of ravishing beauty and staggering plenty. Ralph Lane, the head of the expedition, wrote that “all the kingdoms and states of Christendom, their commodities joined in one together, do not yield either more good or more plentiful whatsoever for public use is needful, or pleasing for delight.” Yet when the supply ship was delayed, the colonists, in the midst of plenty, began to starve. The natives, to whom the colonists had been preaching the Gospel, began telling them, “Our Lord God was not God, since he suffered us to sustain much hunger.” In June, a fleet arrived, commanded by Sir Francis Drake, a swashbuckler who’d sailed across the whole of the globe. He carried a cargo of three hundred Africans, bound in chains. Drake told the colonists that either he could leave them with food, and with a ship to look for a safer harbor, or else he could bring them home. Every colonist opted to leave. On Drake’s ships, they took the places of the Africans, people that Drake may have simply dumped into the cobalt sea, unwanted cargo.

Another expedition sent in 1587 to what had come to be called Roanoke fared no better. John White, an artist and mapmaker who had carefully studied the reports of the first expedition, aimed to establish a permanent colony not on the island but in nearby Chesapeake Bay, in a city to be called Ralegh. Instead, one blunder followed another. White sailed back to England that fall, in hopes of securing supplies and support. His timing could hardly have been less propitious. In 1588, a fleet of 150 Spanish ships attempted to invade England. Eventually, the armada was defeated. But with a naval war with Spain raging, White had no success in scaring up more ships to sail to Roanoke, leaving the settlement marooned.

Any record of the fate of the English colony at Roanoke, like most of what has ever happened in the history of the world, was lost. When White finally returned, in 1590, he found not a single Englishman, nor his daughter, nor his grandchild, a baby named Virginia, after Elizabeth, the virgin queen. Nearly all that remained of the settlement were the letters “CRO” carved into the trunk of a tree, a sign that White and the colonists had agreed upon before he left, a sign that they’d packed their things and headed inland to find a better site to settle. Three letters, and not one letter more. They were never heard from again.

“We found the people most gentle, loving and faithful, void of all guile and treason and such as lived after the manner of the Golden Age,” Arthur Barlowe, one of Ralegh’s captains, had earlier written home, describing Roanoke as a kind of Eden.53 The natives weren’t barbarians; they were ancestors, and the New World was the oldest world of all.

In the brutal, bloody century between Columbus’s voyage and John White’s, an idea was born, out of fantasy, out of violence, the idea that there exists in the world a people who live in an actual Garden of Eden, a state of nature, before the giving of laws, before the forming of government. This imagined history of America became an English book of genesis, their new truth.

“In the beginning,” the Englishman John Locke would write, “all the world was America.” In America, everything became a beginning.