Two

THE RULERS AND THE RULED

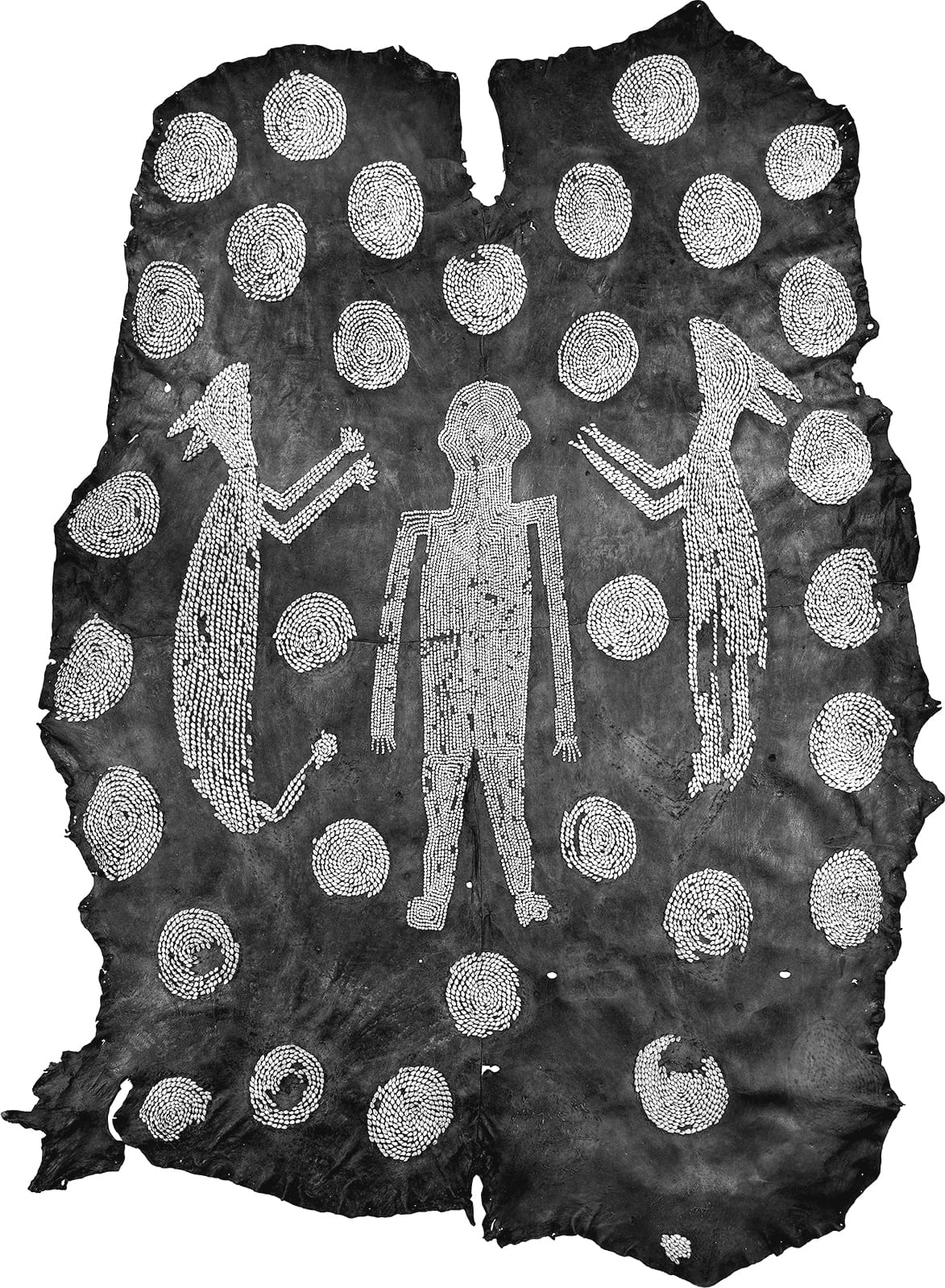

THEY SKINNED THE DEER WITH KNIVES MADE OF STONE and scraped the hides of flesh and fat with a rib bone. They soaked the hides in wood ash and corn mash and stretched them on a frame of sticks before sewing them together with thread made of tendons, twisted. Onto these stitched and tanned hides, they embroidered hundreds of tiny shells of seashore snails, emptied and dried, into the pattern of a man, flanked by a white-tailed deer and a mountain lion in a field of thirty-four circles.

This man was their ruler, the animals his spirits, and the circles the villages over which he ruled. One of his names was Wahunsunacock, but the English called him Powhatan. He may have worn the deerskin as a cloak; he may have used it to honor his ancestors. He may have given it to the English as a gift, in 1608, when their king, James, sent to him the gift of a scarlet robe, one robe for another. Or, the English might have stolen it. Somehow, someone carried it to England on a ship. In 1638, an Englishman who saw it in a museum in England, called the sinew-stitched deerskin decorated with shells “the robe of the King of Virginia.” But if it was Powhatan’s cloak, it also served as a map of his realm.1

The English called Powhatan “king,” for the sake of diplomacy, but it was the king of England who claimed to be the king of Virginia: James considered Powhatan among his subjects. The nature and history of the two kings’ reigns casts light on matters with which England’s colonists would wrestle for more than a century and a half: Who rules, and by what right?

Powhatan was born about 1545. At the death of his father, he inherited rule over six neighboring peoples; in the 1590s, he’d begun expanding his reign. On the other side of the ocean, James was born in 1566; the next year, when his mother died, he became king of Scotland. In 1603, after the death of his cousin Elizabeth, James was crowned king of England. The separation of the Church of England from the Church of Rome had elevated the monarchy, since the king no longer answered to the pope, and James believed that he, like the pope, was divinely appointed by God. “As to dispute what God may doe is Blasphemie,” he wrote, in a treatise called The True Law of Free Monarchies, “so is it Sedition in subjects to dispute what a King may do”—as if he were both infallible and above the rule of law.2

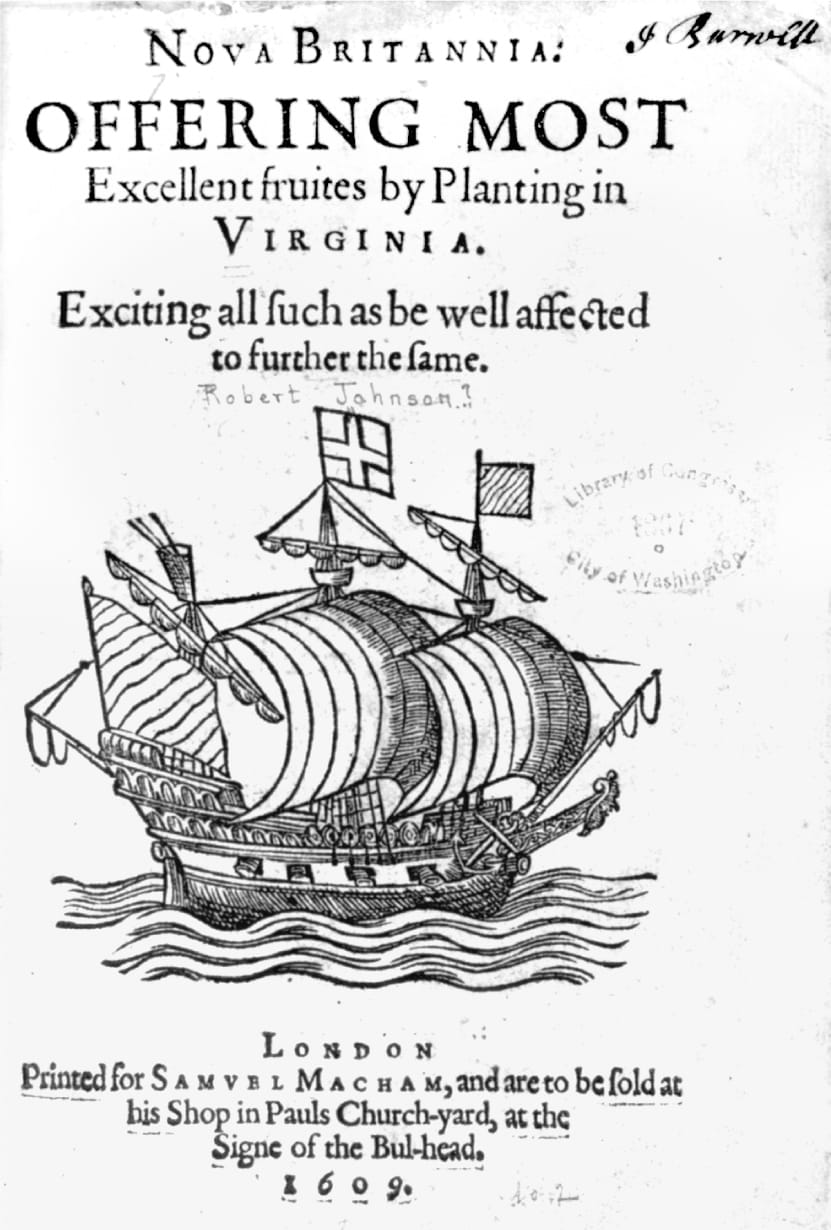

James, a pope-like king, proved more determined to found a colony in the New World than Elizabeth had been. In 1606, he issued a charter, granting to a body of men permission to settle on “that parte of America commonly called Virginia,” land that he claimed as his property, since, as the charter explained, these lands were “not now actually possessed by any Christian Prince or People” and the natives “live in Darkness,” meaning that they did not know Christ.3

Unlike the Spanish, who set out to conquer, the English were determined to settle, which is why they at first traded with Powhatan, instead of warring with him. James granted to the colony’s settlers the right to “dig, mine, and search for all Manner of Mines of Gold, Silver, and Copper,” the very kind of initiatives taken by Spain, but he also urged them to convert the natives to Christianity, on the ground that, “in propagating of Christian Religion to such People,” the English and Scottish might “in time bring the Infidels and Savages, living in those parts, to human Civility, and to a settled and quiet Government.”4 They proposed, he insisted, to bring not tyranny but liberty.

James’s charter, like Powhatan’s deerskin, is also a kind of map. (“Charter” has the same Latin root as “chart,” meaning a map.) By his charter, James granted land to two corporations, the Virginia Company and the Plymouth Company: “Wee woulde vouchsafe unto them our licence to make habitacion, plantacion and to deduce a colonie . . . at any Place upon the said-Coast of Virginia or America, where they shall think fit and convenient.”5 Virginia, at the time, stretched from what is now South Carolina to Canada: all of this, England claimed.

England’s empire would have a different character than that of either Spain or France. Catholics could make converts by the act of baptism, but Protestants were supposed to teach converts to read the Bible; that meant permanent settlements, families, communities, schools, and churches. Also, England’s empire would be maritime—its navy was its greatest strength. It would be commercial. And, of greatest significance for the course of the nation that would grow out of those settlements, its colonists would be free men, not vassals, guaranteed their “English liberties.”6

At such a great distance from their king, James’s colonists would remain his subjects but they would rule themselves. His 1606 charter decreed that the king would appoint a thirteen-man council in England to oversee the colonies, but, as for local affairs, the settlers would establish their own thirteen-man council to “govern and order all Matters and Causes.” And, most importantly, the colonists would retain all of their rights as English subjects, as if they had never left England. If the king meant his guarantee of the colonists’ English liberties, privileges, and immunities as liberties, privileges, and immunities due to them if they were to return to England, the colonists would come to understand them as guaranteed in the colonies, a freedom attached to their very selves.7

Over the course of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the English established more than two dozen colonies, founding a sea-born empire of coastal settlements that stretched from the fishing ports of Newfoundland to the rice fields of Georgia and, in the Caribbean, from Jamaica and Antigua to Bermuda and Barbados. Beginning with the Virginia charter, the idea of English liberties for English subjects was planted on American soil and, with it, the king’s claim to dominion, a claim that rested on the idea that people like Powhatan and his people lived in darkness and without government, no matter that the English called their leaders kings.

And yet England’s own political order was about to be toppled. At the beginning of English colonization, the king’s subjects on both sides of the ocean believed that men were created unequal and that God had granted to their king the right to rule over them. These were their old truths. At the end of the seventeenth century, John Locke, imagining an American genesis and borrowing from Christian theology, would argue that all men were born into a state “of equality, wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another,” each “equal to the greatest, and subject to no body.”8 By 1776, many of the king’s subjects in many of his colonies so wholly agreed with this point of view that they accepted Thomas Paine’s “plain truth,” that, “all men being originally equals,” nothing was more absurd than the idea that God had granted to one person and his heirs the right to rule over all others. “Nature disapproves it,” Paine insisted, “otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule by giving mankind an ass for a lion.”9 These became their new truths.

What had happened between the Virginia charter and the Declaration of Independence to convince so many people that all men are created equal and that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed? The answer lies in artifacts as different as a deerskin cloak and a scarlet robe and in places as far from one another as the ruins of ancient castles and the hulls of slave ships, each haunted by the rattling of iron-forged chains.

I.

VIRGINIA’S FIRST CHARTER was prepared in the office of Attorney General Edward Coke, a sour-tempered man with a pointed chin, a systematic mind, and an ungovernable tongue. Coke, who invested in the Virginia Company, was the leading theorist of English common law, the body of unwritten law established by centuries of custom and cases, to which Coke sought to apply the precepts of rationalism. “Reason is the life of the law,” Coke wrote, and “the common law itself is nothing else but reason.” In 1589, when he was thirty-seven, Coke became a member of Parliament. Five years later, Elizabeth appointed him attorney general. In 1603, after James threw Sir Walter Ralegh in the Tower of London, Coke prosecuted Ralegh for treason, for plotting against the king. “Thou viper,” Coke said to Ralegh in court, “thou hast an English face, but a Spanish heart.” Ralegh languished in prison for thirteen years, writing his history of the world, before he was beheaded. Meanwhile, his conviction freed the right to settle Virginia—a right Elizabeth had granted to Ralegh—to be newly issued by James, under Coke’s watchful eye. Two months after issuing the colony’s charter, James appointed Coke chief justice of the court of common pleas.10

To settle the new colony, the Virginia Company rounded up men who were eager to make their own fortunes, along with soldiers who’d fought in England’s religious wars against Catholics and Muslims. Burly and fearless John Smith, all of twenty-six, had already fought the Spanish in France and in the Netherlands and, with the Austrian army, had battled the Turks in Hungary. Captured by Muslims, he’d been sold into slavery, from which he’d eventually escaped. Engraved on his coat of arms, with three heads of Turks, was his motto, vincere est vivere: to conquer is to live.11 George Sandys, Virginia’s treasurer, had traveled by camel to Jerusalem and had written at length about Islam; William Strachey, the colony’s secretary, had traveled in Istanbul. Much like the Spanish, these men and their investors wanted to found a colony in the New World to search for gold to fund wars to defeat Muslims in the Old World, even as they pledged not to inflict “Spanish cruelties” on the American natives.12

In December 1606, 105 Englishmen—and no women—boarded three ships, carrying a box containing a list of the men appointed by the Virginia Company to govern the colony, “not to be opened, nor the governours knowne until they arrived in Virginia.” During the voyage, Smith was confined belowdecks, shackled and in chains, accused of plotting a mutiny to “make himselfe king.”13 In May 1607, when the expedition finally landed on the banks of a brackish river named after their king, the box was opened, and it was discovered that Smith, though still a prisoner, was on that list.14 Unclapped came his chains.

Whatever “quiet government” the company’s merchants had intended, the colonists proved ungovernable. They built a fort and began looking for gold. But a band of soldiers and gentlemen-adventurers proved unwilling to clear fields or plant and harvest crops; instead, they stole food from Powhatan’s people, stores of corn and beans. Smith, disgusted, complained that the company had sent hardly any but the most useless of settlers. He counted one carpenter, two blacksmiths, and a flock of footmen, and wrote the rest off as “Gentlemen, Tradesmen, Servingmen, libertines, and such like, ten times more fit to spoyle a Commonwealth, than either begin one, or but helpe to maintaine one.”15

In 1608, Smith, elected the colony’s governor, made a rule: “he who does not worke, shall not eat.”16 By way of diplomacy, he staged an elaborate coronation ceremony, crowning Powhatan “king,” and draping upon his shoulders the scarlet robe sent by James. Whatever this gesture meant to Powhatan, the English intended it as an act of their sovereignty, insisting that, in accepting these gifts, Powhatan had submitted to English rule: “Powhatan, their chiefe King, received voluntarilie a crown and a scepter, with a full acknowledgment of dutie and submission.”17 And still the English starved, and still they raided native villages. In the fall of 1609, the colonists revolted—auguring so many revolts to come—and sent Smith back to England, declaring that he had made Virginia, under his leadership, “a misery, a ruine, a death, a hell.”18

The real hell was yet to come. In the winter of 1609–10, five hundred colonists, having failed to farm or fish or hunt and having succeeded at little except making their neighbors into enemies, were reduced to sixty. “Many, through extreme hunger, have run out of their naked beds being so lean that they looked like anatomies, crying out, we are starved, we are starved,” wrote the colony’s lieutenant governor, George Percy, the eighth son of the earl of Northumberland, reporting that “one of our Colline murdered his wife Ripped the Childe outt of her woambe and threwe it into the River and after Chopped the Mother in pieces and salted her for his food.”19 They ate one another.

Word of this dire state of affairs soon reached England. Like nearly everything else reported from across the ocean, it set minds alight. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who served on the board of the Virginia Company, eyed the descent of the colony into anarchy with more than passing interest. In 1622, four years after Powhatan’s death, the natives rose up in rebellion and tried to oust the English from their land, killing hundreds of new immigrants in what the English called the “Virginia massacre.” Hobbes, working out a theory of the origins of civil society by deducing an original state of nature, pondered the violence in Virginia. “The savage people in many places of America . . . have no government at all, and live at this day in that brutish manner,” he would later write, in The Leviathan, a treatise in which he concluded that the state of nature is a state of war, “of every man against every man.”20

Miraculously, the colony recovered; its population grew and its economy thrived with a new crop, tobacco, a plant found only in the New World and long cultivated by the natives.21 With tobacco came the prospect of profit, and a new political and economic order: the colonists would rule themselves and they would rule over others. In July 1619, twenty-two English colonists, two men from each of eleven parts of the colony, met in a legislative body, the House of Burgesses, the first self-governing body in the colonies. One month later, twenty Africans arrived in Virginia, the first slaves in British America, Kimbundu speakers from the kingdom of Ndongo. Captured in raids ordered by the governor of Angola, they had been marched to the coast and boarded the São João Bautista, a Portuguese slave ship headed for New Spain. At sea, an English privateer, the White Lion, sailing from New Netherlands, attacked the São João Bautista, seized all twenty, and brought them to Virginia to be sold.22

Twenty Englishmen were elected to the House of Burgesses. Twenty Africans were condemned to the house of bondage. Another chapter opened in the American book of genesis: liberty and slavery became the American Abel and Cain.

II.

WAVES SLAPPED AGAINST the hulls of ships like the pounding of a drum. Mothers lulled children to sleep while men wailed, singing songs of sorrow. “It frequently happens that the negroes, on being purchased by the Europeans, become raving mad,” wrote one slave trader. “Many of them die in that state.” Others took their own lives, throwing themselves into the sea, hoping that the ocean would carry them to their ancestors.23

The English who crossed the ocean endured the hazards of the voyage under altogether different circumstances, but the perils of the passage left their traces on them, too, in memoirs and stories, and in their bonds to one another. In the summer of 1620, a year after the White Lion landed off the coast of Virginia, the Mayflower, a 180-ton, three-masted, square-rigged merchant vessel, lay anchored in the harbor of the English town of Plymouth, at the mouth of the river Plym. It soon took on its passengers, some sixty adventurers, and forty-one men—dissenters from the Church of England—who brought with them their wives, children, and servants. William Bradford, the dissenters’ chronicler, called them “pilgrims.”24

Bradford, who would become governor of the colony the dissenters would found, became, too, its chief historian, writing, he said, “in a plain style, with singular regard unto the simple truth in all things.” Ten years before, Bradford explained, the pilgrims had left England for Holland, where they’d settled in Leiden, a university town known for learning and for religious toleration. After a decade in exile, they’d decided to make a new start someplace else. “The place they had thoughts on was some of those vast and unpeopled countries of America,” Bradford wrote, “which are fruitful and fit for habitation, being devoid of all civil inhabitants, where there are only savage and brutish men which range up and down, little otherwise than the wild beasts.” Though fearful of the journey, they placed their faith in a providential God, and set sail for Virginia. “All being compact together in one ship,” Bradford wrote, “they put to sea again with a prosperous wind.”

During the treacherous, sixty-six-day journey over what Bradford called the “vast and furious ocean,” one man was swept overboard, saved only by grasping a halyard; the ship leaked; a beam split; and one of the masts bowed and nearly cracked. For two days, the wind grew so fierce that everyone on board had to crowd into the hull, huddled under rafters. When the storm quieted, the crew caulked the decks, fortified the masts, and raised the sails once more. Elizabeth Hopkins gave birth on the swaying ship; she named her son Oceanus. The ship, blown severely off course, dropped anchor not in Virginia but off the windswept coast of Cape Cod. Unwilling to risk the ocean again, the pilgrims rowed ashore to found what they hoped would be a new and better England, another beginning. And yet, wrote Bradford, “what could they see but a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men”? They fell to their knees and praised God they were alive. The day they arrived, having sailed what Bradford described as a “sea of troubles,” in a ship they imagined as a ship of state—the whole body of a people, in the same boat—they signed a document in which they pledged to “covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic.”25 They named their agreement after their ship. They called it the Mayflower Compact.

The men who settled Virginia had been granted a charter by the king. But the men, women, and children who settled in what they called a New England had no charter; they’d fled the king, bridling against his rule. Religious dissent in seventeenth-century England was also a form of political dissent. It was punishable by both imprisonment and execution. But if James’s divine right to rule was questioned by dissenters who fled his authority, it was being questioned, too, on the floor of Parliament. The battle between the king and Parliament would send tens of thousands more exiles across the vast and furious ocean, seeking political freedom in the colonies. It would also foster in them a deep and abiding spirit of rebellion against arbitrary rule.

Even as dissenters in New England struggled to survive their first winter in a settlement they named Plymouth, members of Parliament were beginning to challenge the tradition by which Parliament met only when summoned by the king. In 1621, Edward Coke, who, after Ralegh’s beheading in 1618 had emerged as James’s most cunning adversary, claimed that Parliament had the right to debate on all matters concerning the Commonwealth. The king had Coke arrested, confined him to the Tower of London, and dissolved Parliament. Ralegh had written a history of the world while in prison; Coke would write a history of the law.

To build his case against the king, Coke dusted off a copy of an ancient and almost entirely forgotten legal document, known as Magna Carta (literally, the “great charter”), in which, in the year 1215, King John had pledged to his barons that he would obey the “law of the land.” Magna Carta wasn’t nearly as important as Coke made it out to be, but by arguing for its importance, he made it important, not only for English history, but for American history, too, tying the political fate of everyone in England’s colonies to the strange doings of a very bad king from the Middle Ages.

King John, born in 1166, was the youngest son of Henry II. As a young man, he’d studied with his father’s chief minister, Ranulf de Glanville, who had dedicated himself to preparing one of the earliest commentaries on the English law, in which he had attempted to address the rather delicate question of whether a law can be a law if no one had ever written it down.26 It would be “utterly impossible for the laws and rules of the realm to be reduced to writing,” Glanville admitted. That said, unwritten laws are still laws, he insisted; they are a body of custom and precedent that together constitute “common law.”27

Glanville’s ruminations had led him to another and even more delicate question: If the law isn’t written down, and even if it is, by what argument or force can a king be constrained to obey it? Kings had insisted on their right to rule, in writing, since the sixth century BC.28 And, at least since the ninth century AD, they’d been binding themselves to the administration of justice by taking oaths.29 In 1100, in the Charter of Liberties, Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror, promised to “abolish all the evil customs by which the kingdom of England has been unjustly oppressed,” which, while not a promise that he kept, set a precedent that Glanville might have expected would act to restrain Henry I’s grandson King John.30

Unfortunately, King John proved a tyrant, heedless of the Charter of Liberties. He levied taxes higher than any king ever had before and either carried so much coin outside his realm or kept so much of it in his castle that it was difficult for anyone to pay him with money. When his noblemen fell into his debt, he took their sons hostage. He had one noblewoman and her son starved to death in a dungeon. Rumor had it that he ordered one of his clerks crushed to death.31

In 1215, barons rebelling against the king captured the Tower of London.32 When John agreed to meet with them to negotiate a peace and they gathered at Runnymede, a meadow by the Thames, the barons presented him with a very long list of demands, which were rewritten as a charter, in which the king granted “to all free men” in his realm—that is, not to the people, but to noblemen—“all the liberties written out below, to have and to keep for them and their heirs, of us and our heirs.”33 This was the great charter, the Magna Carta.

Magna Carta had been revoked almost immediately after it was written, and it had become altogether obscure by the time of King James and his battles with the ungovernable Edward Coke. But Coke, as brilliant a political strategist as he was a legal scholar, resurrected it in the 1620s and began calling it England’s “ancient constitution.” When James insisted on his sovereignty—an ancient authority, by which the monarch is above the law—Coke, countering with his ancient constitution, insisted that the law was above the king. “Magna Carta is such a fellow,” Coke said, “that he will have no sovereign.”34

Coke’s resurrection of Magna Carta explains a great deal about how it is that some English colonists would one day come to believe that their king had no right to rule them and why their descendants would come to believe that the United States needed a written constitution. But Magna Carta played one further pivotal role, the role it played in the history of truth—a history that had taken a different course in England than in any other part of Europe.

The most crucial right established under Magna Carta was the right to a trial by jury. For centuries, guilt or innocence had been determined, across Europe, either by a trial by ordeal—a trial by water, for instance, or a trial by fire—or by trial by combat. Trials by ordeal and combat required neither testimony nor questioning. The outcome was, itself, the evidence, the only admissible form of judicial proof, accepted because it placed judgment in the hands of God. Nevertheless, the practice was easily abused—priests, after all, could be bribed—and, in 1215, the pope banned trial by ordeal. In Europe, it was replaced by a new system of divine judgment: judicial torture. But in England, where there existed a tradition of convening juries to judge civil disputes—like disagreements over boundaries between neighboring freeholds—trial by ordeal was replaced not by judicial torture but by trial by jury. One reason this happened is because, the very year that the pope abolished trial by ordeal, King John pledged, in Magna Carta, that “no free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned . . . save by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.”35 In England, truth in either a civil dispute or criminal investigation would be determined not by God but by men, and not by a battle of swords but by a battle of facts.

This turn marked the beginning of a new era in the history of knowledge: it required a new doctrine of evidence and new method of inquiry and eventually led to the idea that an observed or witnessed act or thing—the substance, the matter, of fact—is the basis of truth. A judge decided the law; a jury decided the facts. Mysteries were matters of faith, a different kind of truth, known only to God. But when, during the Reformation, the Church of England separated from the Roman Catholic Church, protesting the authority of the pope and finding truth in the Bible, the mysteries of the church were thrown open, the secrets of priests revealed. The age of mystery began to wane, and, soon, the culture of fact spread from law to government.36

In seventeenth-century England, the meat of the matter between the king and Parliament was a dispute over the nature of knowledge. King James, citing divine right, insisted that his power could not be questioned and that it lay outside the realm of facts. “That which concerns the mystery of the king’s power is not lawful to be disputed,” he said.37 To dispute the divine right of kings was to remove the king’s power from the realm of mystery, the realm of religion and faith, and place it in the realm of fact, the realm of evidence and trial. To grant to the colonies a charter was to establish law on a foundation of fact, a repudiation of government by mystery.

By what right did the king rule? And how might Parliament constrain him? After James died, in 1625, his son, Charles, was crowned king, but Charles, too, believed in the divine right of kings. Three years later, Coke, now seventy-six, and having returned to Parliament, objected to Charles’s exerting his royal prerogative to billet soldiers in his subjects’ homes and to confine men to jail, without trial, for refusing to pay taxes. Coke claimed that the king’s authority was constrained by Magna Carta.38 At Coke’s suggestion, Parliament then prepared and delivered to King Charles a Petition of Right, which cited Magna Carta to insist that the king had no right to imprison a subject without a trial by jury. If Coke had been successful, England’s American colonies would have been less so. Instead, in 1629, the king, having forbidden Coke from publishing his study of Magna Carta, dissolved Parliament. It was this act that led tens of thousands of the king’s subjects to flee the country and cross the ocean, vast and furious.

Between 1630 and 1640, the years during which King Charles ruled without Parliament, a generation of ocean voyagers, some twenty thousand dissenters, fled England and settled in New England. One of these people was John Winthrop, a stern and uncompromising man with a Vandyke beard and a collar of starched ruffles, who decided to join a new expedition to found a colony in Massachusetts Bay. Unlike Bradford’s pilgrims, who wanted to separate from the Church of England, Winthrop was one of a band of dissenters known as Puritans—because they wanted to purify the Church of England—who lost their positions in court after the dissolution of Parliament. In 1630, Winthrop, who would become the first governor of Massachusetts, wrote an address called “A Model of Christian Charity” to his fellow settlers. The Mayflower compact had described the union of Plymouth’s settlers into a body politic, but Winthrop described the union of his people in the body of Christ, held together by the ligaments of love. “All the parts of this body being thus united are made so contiguous in a special relation as they must needs partake of each other’s strength and infirmity, joy and sorrow, weal and woe,” he said, citing 1 Corinthians 12. “If one member suffers, all suffer with it; if one be in honor, all rejoice with it.” In this, their New England, he said, they would build a city on a hill, as Christ had urged in his Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:14): “A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid.”39

Colonies sprouted along the Atlantic coast like cattails along the banks of a pond. Roger Williams, once Coke’s stenographer, joined the mission to Massachusetts Bay, although for his commitment to religious toleration he was banished in 1635. The next year, he founded Rhode Island. In 1624, the Dutch had settled New Netherland (which later became New York); in 1638, Swedish colonists settled New Sweden, a colony that straddled parts of latter-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Even colonies that weren’t Puritan were founded by dissenters of one kind or another. Maryland, named after Charles I’s Catholic wife, Henrietta Maria, started in 1634 as a sanctuary for Catholics. Connecticut, like Rhode Island, was founded in 1636, New Haven in 1638, New Hampshire in 1639.

English migrants often came as families and they sometimes came as whole towns, hoping to found a Christian commonwealth, a religious community bound to the common wealth of all, public good over private gain. “The care of the public must oversway all private respects,” Winthrop said. “For it is a true rule that particular estates cannot subsist in the ruin of the public.” They expected the world to be watching. “The eyes of all people are upon us,” Winthrop said. Theirs was an ordered world, a world of hierarchy and deference. They considered the family a “little commonwealth,” the father its head, just as a minister is the head of a congregation and the king is the head of his people. They built towns around commons—lands owned in common, for pasturing animals. They did not consider a commitment to the public good, the common weal, to be at odds with the desire for prosperity. They believed in providence: everything happened for a reason, ordained by God.

Wealth was a sign of God’s favor, its accretion for its own sake a great sin. New Englanders expected to thrive by farming and by trade. “In America, religion and profit jump together,” wrote Edward Winslow, of Plymouth.40 They governed themselves through town meetings. Their lives centered on their churches, or meetinghouses: they built more than forty of them in their first two decades. In England, they’d raised money by promising to “propagate the Gospel,” that is, to convert the Indians to Christianity. Massachusetts adopted as a colony seal a drawing of a nearly naked Indian mouthing the words “Come Over and Help Us,” a reference to the biblical Macedonians, awaiting Christ. In 1636, New England Puritans founded a school in Cambridge for educating “English and Indian youth”: Harvard College. The next year, in Connecticut, war broke out between the colonists and the Pequot Indians. At the end of the war, the colonists decided to turn captured Indians into slaves and to sell them to the English in the Caribbean. In 1638, the first African slaves in New England arrived in Salem, on board a ship called the Desire that had carried captured Pequots to the West Indies, where they’d been traded, as Winthrop noted in his diary, for “some cotton and tobacco, and negroes.” There would never be very many Africans in New England, but New Englanders would have slave plantations, on the distant shores. Nearly half of colonial New Englanders’ wealth would come from sugar grown by West Indian slaves.41

The English in the colonies understood their rights as “free men” as deriving from an “ancient constitution” that guaranteed that even kings were subject to the “laws of the land.” These same people sold Indians and bought Africans. By what right did they rule them, in their city on a hill?

III.

ENGLAND’S AMERICA WAS disproportionately African. England came late to founding colonies and it came late to trafficking in slaves, but nearly as soon as it entered that trade, it dominated it. One million Europeans migrated to British America between 1600 and 1800 and two and a half million Africans were carried there by force over that same stretch of centuries, on ships that sailed past one another by day and by night.42 Africans died faster, but as a population of migrants, they outnumbered Europeans two and a half to one.

Much as the English had told lurid tales of “Spanish cruelties” in the Americas, they had long condemned the Portuguese for trading in Africans. An English trader named Richard Jobson told a Gambian man who tried to sell him slaves in 1621 that the Portuguese “were another kinde of people different from us.” The Portuguese bought and sold people, like animals, but the English, Jobson said, “were a people, who did not deale in any such commodities, neither did wee buy or sell one another, or any that had our owne shapes.”43

But in the 1640s, when English settlers in Barbados began planting sugar, they set these long-held reservations aside. Growing sugar takes more work than growing tobacco. To grow this difficult but wildly profitable new crop, Barbadian planters bought Africans from the Spanish and the Dutch and, soon enough, from the English. In 1663, not long after the English entered the slave trade, they founded the Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading with Africa. In the last twenty-five years of the seventeenth century, English ships, piloted by English sea captains, crewed by English sailors, carried more than a quarter of a million men, women, and children across the ocean, shackled in ships’ holds.44 Theirs was not a ship of state crossing a sea of troubles, another Mayflower, their bond a covenant. Theirs was a ship of slavery, their bonds forged in fire. They whispered and wept; they screamed and sat in silence. They grew ill; they grieved; they died; they endured.

Many of the Africans bought by English traders were Bantu speakers and came from the area around what is now Senegambia; some were Akan speakers, from what is now Ghana; others spoke Igbo, and came from what is now Nigeria. During the march to the coast, on the journey across the Atlantic, on islands in the Caribbean, on the continent, and above all on board those ships, they died in staggering numbers. They believed that they lived after death. Nyame nwu na mawu, they said, in Akan: “God does not die, so I cannot die.”45

By what right did the English hold these people as their slaves? They looked to the same ancient authorities as had Juan Sepúlveda, in his debate with Bartolomé de Las Casas at Valladolid in 1550—and found them insufficient. Under Roman law, all men are born free and can only be made slaves by the law of nations, under certain narrow conditions—for instance, when they’re taken as prisoners of war, or when they sell themselves as payment of debt. Aristotle had disagreed with Roman law, insisting that some men are born slaves. Neither of these traditions from antiquity proved to be of much use to English colonists attempting to codify their right to own slaves, because laws governing slavery, like slavery itself, had disappeared from English common law by the fourteenth century. Said one Englishman in Barbados in 1661, there was “no track to guide us where to walk nor any rule sett us how to govern such Slaves.”46 With no track or rule to guide them, colonial assemblies adopted new practices and devised new laws with which they attempted to establish a divide between “blacks” and “whites.” As early as 1630, an Englishman in Virginia was publicly whipped for “defiling his body in lying with a negro.”47 Adopting these practices and passing these laws required turning English law upside down, because much in existing English law undermined the claims of owners of people. In 1655, a Virginia woman with an African mother and an English father sued for her freedom by citing English common law, under which children’s status follows that of their father, not their mother. In 1662, Virginia’s House of Burgesses answered doubts about “whether children got by any Englishman upon a Negro woman should be slave or ffree” by reaching back to an archaic Roman rule, partus sequitur ventrem (you are what your mother was). Thereafter, any child born of a woman who was a slave inherited her condition.48

In one of the more unsettling ironies of American history, laws drafted to justify slavery and to govern slaves also codified new ideas about liberty and the government of the free. In 1641, needing to provide some legal support for trading Indians for Africans, the Massachusetts legislature established The Body of Liberties, a bill, or list, of one hundred rights, many of them taken from Magna Carta. (A century and a half later, seven of them would appear in the U.S. Bill of Rights.) The Body of Liberties includes this prohibition: “There shall never be any bond slaverie, villinage or Captivitie amongst us unles it be lawfull Captives taken in just warres, and such strangers as willingly selle themselves or are sold to us.” Drawing on Roman law, the provision about slavery offered specific legal cover for selling into slavery Pequot and other Algonquians captured by the colonists during the Pequot War in 1637 and for the sale and purchase of Africans—described under the language of “strangers,” that is, foreigners who “are sold to us”—so that there would be no legal question to debate.49 Not for another century and a half would New Englanders be willing to open the legality of slavery to debate.

Tied to England, to the Caribbean, and to West Africa by the path steered by ships that sailed between them, colonists plotted the course of their laws. Even as England’s colonists justified the taking of slaves and insisted on their right to rule over them absolutely and without restraint, the king’s subjects were fighting to restrain his authority. Under what conditions do some people have a right to rule, or to rebel, and others not? In 1640, King Charles at last summoned a meeting of Parliament in hopes of raising money to suppress a rebellion in Scotland. The newly summoned Parliament, striking back, passed a law abridging the king’s authority, including requiring that Parliament meet at least once every three years, with or without a royal summons. War between supporters of the king and backers of Parliament broke out in 1642. During this battle, the legal fiction of the divine right of kings was replaced by another legal fiction: the sovereignty of the people.50

This idea, which would ride across the ocean on the crest of every wave, rested on the notion of representation. Parliaments had first met in the thirteenth century, when the king began summoning noblemen to court to parler, demanding that they pledge to obey his laws and pay his taxes. After a while, those noblemen began pretending that they weren’t making these pledges for themselves alone but that, instead, in some meaningful way, they “represented” the interests of other people, their vassals. In the 1640s, those parleying noblemen, now called Parliament, challenged the king, countering his claim to sovereignty with a claim of their own: they argued that they represented the people and that the people were sovereign. They said this was because, in some time immemorial, the people had granted them authority to represent them. Royalists pointed out that this was absurd. How can “the people” rule when “they which are the people this minute, are not the people the next minute”? Who even are the people? Also, when, exactly, did they empower Parliament to represent them? In 1647, the Levellers, hoping to remedy this small problem, drafted An Agreement of the People, with the idea that every Englishman would sign it, granting to his representatives the power to represent him.51 This didn’t quite come to pass. Instead, in 1649, the king was tried for treason and beheaded.

Out of this same quarrel came foundational ideas about freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press, ideas premised on the belief, heretical to the medieval church, that there is no conflict between freedom and truth. In 1644, the Puritan poet John Milton—later the author of Paradise Lost—published a pamphlet in which he argued against a law passed by Parliament requiring printers to secure licenses from the government for everything they printed. No book should be censored before publication, Milton argued (though it might be condemned after printing), because truth could only be established if allowed to do battle with lies. “Let her and falsehood grapple,” he urged, since, “whoever knew Truth to be put to the worst in a free and open encounter?” This view depended on an understanding of the capacity of the people to reason. The people, Milton insisted, are not “slow and dull, but of a quick, ingenious and piercing spirit, acute to invent, subtle and sinewy to discourse, not beneath the reach of any point the highest that human capacity can soar to.”52

In Rhode Island, Roger Williams dedicated himself to the cause of the “liberty of conscience,” the idea that the freer people are to think, the more likely they are to arrive at the truth. In a letter written in 1655, Williams borrowed from Plato’s Republic the idea of a political society as like passengers on board a ship—a metaphor adored by people who had crossed a desperately dangerous ocean. “There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship, whose weal and woe is common, and is a true picture of a commonwealth, or a human combination or society,” Williams wrote, and sometimes “both papists and protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked in one ship.” The shipmaster ought to protect their freedom to worship as they wished, Williams insisted, by insuring “that none of the papists, protestants, Jews, or Turks, be forced to come to the ship’s prayers of worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any.”53

Williams, who notably included in his commonwealth Catholics and all manner of Protestants but also Jews and Muslims, imagined a particularly capacious ship, at a time when religious and political dissent was flourishing. Between 1649 and 1660, England had no king, and became a commonwealth, and people took seriously the idea of a common wealth, everyone in the same boat as everyone else, and it also got a little easier to pretend that there existed such a thing as the people, and that they were the sovereign rulers of . . . themselves. In England, new sects thrived, from Baptists to Quakers. The Diggers advocated communal ownership of land. The Levellers argued for political equality. Meanwhile, on the other side of the ocean, the colonies grew, and the colonists came to see themselves as the people, too. Not to mention, much of British America was itself the product of religious and political rebellion, each colony its own experiment in the rule of the people and freedom of speech. Most colonies established assemblies, popularly elected legislatures, and made their own laws. By 1640, eight colonies had their own assemblies. Barbados, settled by the English in 1627, was by 1651 insisting that Parliament had no authority over its internal affairs (which, in any event, chiefly concerned the law of slavery).

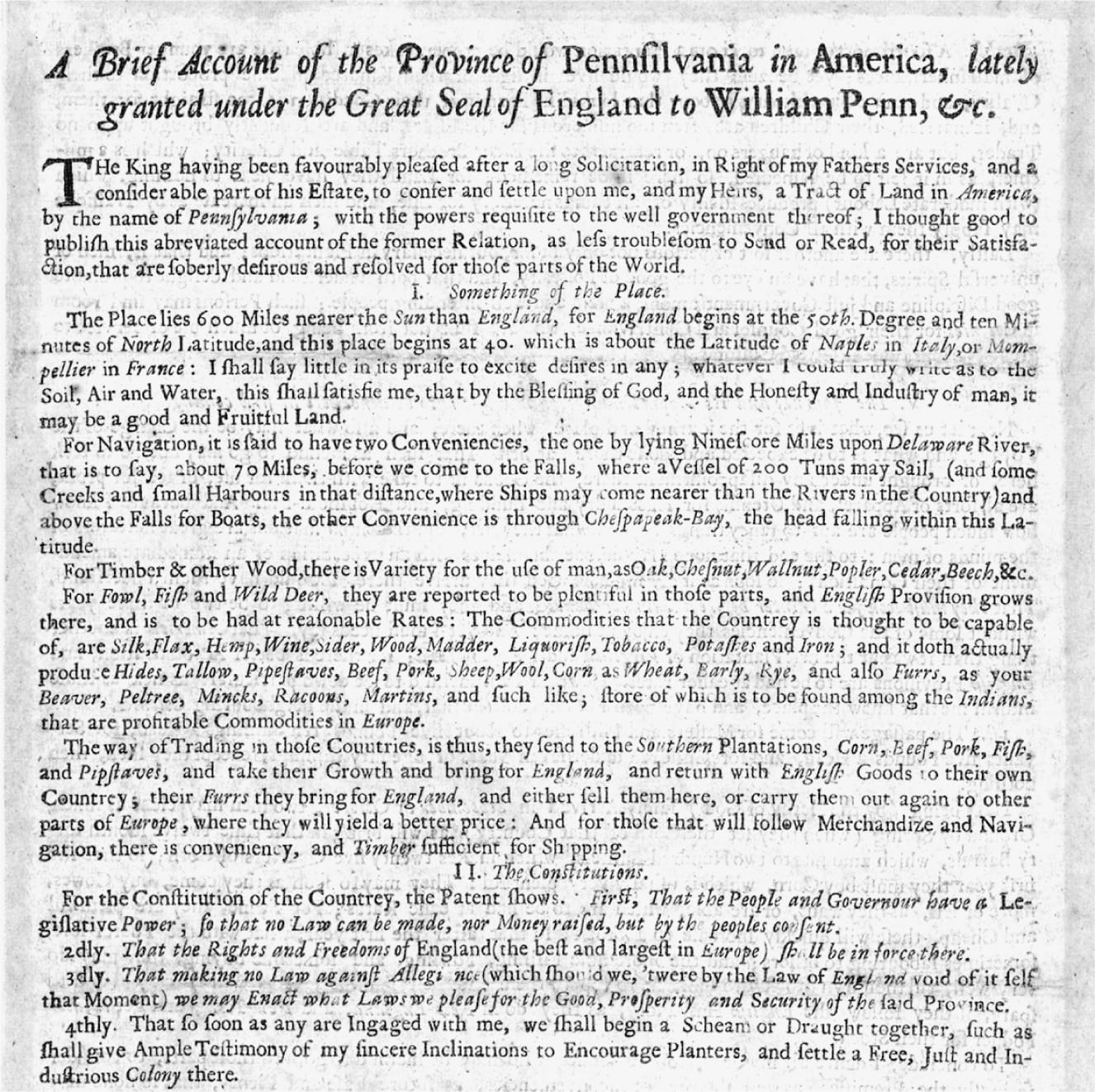

The restoration of the monarchy, in 1660, with the coronation of Charles II, represented not a lessening but a deepening commitment to religious toleration, the new king pledging “that no man shall be disquieted or called in question for differences of opinion in matter of religion.” This spirit extended across the ocean, especially in the six Restoration colonies, those that were founded or came under English rule during Charles II’s reign. New York and New Jersey became religious asylums for Quakers, Presbyterians, and Jews, as did Pennsylvania, granted by Charles II to the Quaker William Penn in 1681. Penn called Pennsylvania his “holy experiment” and hoped it would form “the seed of a nation.” In his 1682 Frame of Government, a constitution for the new colony, he provided for a popularly elected general assembly and for freedom of worship, decreeing “That all persons living in this province, who confess and acknowledge the one Almighty and eternal God, to be the Creator, Upholder and Ruler of the world; and that hold themselves obliged in conscience to live peaceably and justly in civil society, shall, in no ways, be molested or prejudiced for their religious persuasion or practice, in matters of faith and worship, nor shall they be compelled, at any time, to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place or ministry whatever.”54 Peace rested on tolerance.

With each new charter, with each new constitution, with each new slave code, England’s American colonists upended assumptions and rewrote laws governing the relationship between the rulers and the ruled. In the tumult of a century of civil strife, the water between England and America became a kind of looking glass: people drafting new laws saw in their reflections political philosophers; political philosophers saw in their reflections colonial lawmakers. Few people contemplated this relationship more closely than John Locke, a political philosopher who also served as colonial lawmaker.

Locke, a tutor at Christ Church, Oxford, had a hollow face and a long nose; he looked like a bird of prey. He never married. One of his students was the son of the Earl of Shaftesbury, who was the chancellor of the exchequer, and a rather ill man. In 1667, Locke left Oxford and became Shaftesbury’s personal secretary, in charge as well of his medical care; he moved into Exeter House, Shaftesbury’s London residence, in the Strand. It happened that Shaftesbury was deeply involved in colonial affairs, serving and establishing various councils on trade and plantations, including the board of proprietors for the colony of Carolina. (Charles had granted the colony to eight members of Parliament who had supported his restoration to the throne.) Locke became the colony’s secretary.

As secretary, Locke wrote and later revised the colony’s constitution, not long after writing his Letters concerning Toleration, and at the very time when he was drafting Two Treatises on Civil Government, works that would later greatly influence the framers of the U.S. Constitution.55 Without ever crossing the ocean, Locke dug deep into the soil of the colonies and planted seeds as small as the nibs of his pen.

Consistent with his argument in his Letters concerning Toleration, Locke’s Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina established freedom of religious expression. People who did “not acknowledge a God and that God is publickly and solemnly to be worshiped” were to be barred from settling and owning land, but, aside from that, any belief was acceptable, the constitution decreeing that “heathens, Jews and other dissenters from the purity of Christian Religion may not be scared and kept at a distance.” Moreover, and in this same spirit—and here weighing in on a debate that had begun in 1492 and had occupied the Spanish throne for the better part of a century—Carolina’s constitution established that the heathenism of the natives was not sufficient grounds to take their lands: “The Natives of that place,” the constitution stipulated, “are utterly strangers to Christianity whose Idollatry Ignorance or mistake gives us noe right to expell or use them ill.”56 By what right, then, did the English claim their land?

The answer to this question rested in Locke’s philosophy. The Fundamental Constitutions established a government as a matter of practice, while in the Two Treatises on Civil Government Locke attempted to explain, as a matter of philosophy, how governments come to exist. He began by imagining a state of nature, a condition before government:

To understand political power right, and derive it from its original, we must consider, what state all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man.

This was more than a thought experiment; this was a known place: “In the beginning,” he wrote, “all the world was America.”

This state of nature, for Locke, was a state of “perfect freedom” and “a state also of equality.” Locke’s egalitarianism derived, in part, from his ideas about Christianity, and the equality of all people before God, “there being nothing more evident, than that creatures of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another without subordination or subjection.” From this state of natural, perfect equality, men created civil society—government—for the sake of order, and the protection of their property.

To understand how governments came to exist, then, required understanding how people come to hold property. This, for Locke, required looking to the example of America. Half of the references to America in Locke’s Second Treatise come in the chapter called “Of Property.”57 He considered, for instance, kings like Powhatan, whose deerskin cloak Locke might well have held in his hands, fingering its snail shells, since the cloak was housed in a museum at Oxford. “The Kings of the Indians in America,” Locke wrote, “are little more than Generals of their Armies,” and the Indians, having no property, have “no Government at all.” Kings like Powhatan had no sovereignty, according to Locke, because they did not cultivate the land; they only lived there. “God gave the World to Men in Common,” Locke wrote, but “it can not be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the Industrious and Rational, (and Labour was to be his Title to it).” People who leave “great Tracts of Ground” to waste—that is, uncultivated—and who owned land in common, have therefore not “joyned with the rest of Mankind.” A people who do not believe land can be owned by individuals not only cannot contract to sell it, they cannot be said to have a government, because government only exists to protect property.

It’s not that this idea was especially new. In Utopia in 1516, Thomas More had written that taking land from a people that “does not use its soil but keeps it idle and waste” was a “most just cause for war.”58 But Locke, spurred both by a growing commitment to religious toleration and by a desire to distinguish English settlement from Spanish conquest, stressed the lack of cultivation as a better justification for taking the natives’ land than religious difference, an emphasis with lasting consequences.

In both the Carolina constitution and in his Two Treatises on Government, Locke treated both property and slavery. “Slavery” is, in fact, the very first word in the Two Treatises, which begins: “Slavery is so vile and miserable an estate of man, and so directly opposite to the generous temper and courage of our nation, that it is hardly to be conceived that an Englishman, much less a gentleman, should plead for it.” This was an attack on Sir Robert Filmer, who had argued, in a book called Patriarcha, that the king’s authority derives, divinely, from Adam’s rule and cannot be protested. For Locke, to believe that was to believe that the subjects of the king were nothing but his slaves. Locke argued that the king’s subjects were, instead, free men, because “the natural liberty of man is to be free from any superior power on earth, and not to be under the will or legislative authority of man, but to have only the law of nature for his rule.” All men, Locke argued, are born equal, with a natural right to life, liberty, and property; to protect those rights, they erect governments by consent. Slavery, for Locke, was no part either of a state of nature or of civil society. Slavery was a matter of the law of nations, “nothing else, but the state of war continued, between a lawful conqueror and a captive.” To introduce slavery in the Carolinas, then, was to establish, as fundamental to the political order, an institution at variance with everything about how Locke understood civil society. “Every Freeman of Carolina, shall have absolute power and Authority over his Negro slaves,” Locke’s constitution read. That is to say, notwithstanding the vehement assertion of a natural right to liberty and the claim that absolute power is a form of tyranny, the right of one man to own another—impossible to conceive in a state of nature or under a civil government, impossible to imagine under any arrangement except a state of war—was not only possible, but lawful, in America.59

The only way to justify this contradiction, the only way to explain how one kind of people are born free while another kind of people are not, would be to sow a new seed, an ideology of race. It would take a long time to grow, and longer to wither.

IV.

THE REVOLUTION IN AMERICA, when it came, began not with the English colonists but with the people over whom they ruled. Long before shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, long before George Washington crossed the Delaware, long before American independence was thought of, or even thinkable, a revolutionary tradition was forged, not by the English in America, but by Indians waging wars and slaves waging rebellions. They revolted again and again and again. Their revolutions came in waves that lashed the land. They asked the same question, unrelentingly: By what right are we ruled?

It often seemed to England’s colonists as if these rebellions were part of a conspiracy, especially when they came one after another, as they did in 1675 and 1676, a century before the English began their own struggle for independence. In June of 1675, a federation of New England Algonquians, led by a sachem named Metacom (the English called him “King Philip”), attempted to oust the foreigners from their lands, attacking town after town. The Indians, one Englishman wrote, had “risen round the country.” Before it was over, more than half of all the English towns in New England had been either destroyed or abandoned. Metacom was shot, drawn, quartered, and beheaded, his severed head placed on a pike in Plymouth, a king’s punishment. His nine-year-old son was sold as a slave and shipped to the Caribbean, where a slave rebellion had just broken out in Barbados. The English in Barbados believed that the Africans there “intended to Murther all the White People”; their “grand design was to choose them a King.” (Panicked, the legislature on the island swiftly passed a law banning the buying of any Indian slaves carried from New England, for fear that they would only add to the rebellion.) New England and Barbados, one New Englander remarked, had “tasted of the same cup.”

That cup spilled over. Even as war was raging in New England and rebellion was seizing Barbados, natives began attacking English towns in Maryland and Virginia, leading Virginia governor William Berkeley to declare that “the Infection of the Indianes in New-England” had spread southward. Berkeley’s refusal to retaliate against the Indians led to a rebellion incited by a colonist named Nathaniel Bacon, who led a band of five hundred men to Jamestown, which they burned to the ground. More mayhem would have surely followed had not Berkeley lost his governorship and Bacon died of dysentery.60

Wars and rebellions and rumors of more filled the pages of colonial letters and newspapers. Word spread wide and far, and invariably had this effect: racial lines hardened. Before King Philip’s War, ministers in New England had attempted to convert the natives to Christianity, to teach them English, with the idea that they would eventually live among the English. After the war, these efforts were largely abandoned. Bacon’s Rebellion hardened lines between whites and blacks. Before Bacon and his men burned Jamestown, poor Englishmen had very little political power. As many as three out of every four Englishmen and women who sailed to the colonies were either debtors or convicts or indentured servants; they weren’t slaves, but neither were they free.61 Property requirements for voting meant that not all free white men could vote. Meanwhile, the fact that slaves could be manumitted by their masters meant that it was possible to be both black and free and white and unfree. But after Bacon’s Rebellion, free white men were granted the right to vote, and it became nearly impossible for black men and women to secure their freedom. By 1680, one observer could remark that “these two words, Negro and Slave” had “grown Homogeneous and convertible”: to be black was to be a slave.62

Fear of war and rebellion haunted every English colony, lands of terror, and of terrifying political instability and physical vulnerability. In 1692, nineteen women and men were convicted of witchcraft in the Massachusetts town of Salem. What looked like witchcraft, though, appears to have been the aftermath of Indian attacks, the haunting memories of terrible suffering. During the witch trials, when Mercy Short said the Devil had tormented her by burning her, she described the Devil as “a Short and a Black Man . . . not of Negro, but of a Tawney, or an Indian colour.” Two years before Satan and his witches afflicted Mercy Short, she had been captured by Abenakis, who raided her family’s home in a town in New Hampshire, killing her parents and three of her brothers and sisters. Mercy Short had been forced to walk into Canada. Along the way, she witnessed atrocity upon atrocity: a five-year-old boy chopped to pieces, a young girl scalped, and a fellow captive “Barbarously Sacrificed,” bound to a stake, and tortured with fire, the Abenakis cutting off his flesh, bit by bit. Witches call the Devil “a Black Man,” the Boston minister Cotton Mather observed, “and they generally say he resembles an Indian.” Mather took that to mean that blacks and Indians were devils, of a sort, instruments of evil. But what haunted Mercy Short wasn’t the working of witchcraft; it was the working of terror.63

Even in years and places where there were no attacks, there was news of them, from other places, and, always, there was a terror of them. There were uprisings everywhere, and where there were not uprisings, there was fear of uprisings. Some of the plots that the settlers were forever suspecting, detecting, and suppressing were real, and some were imagined, but they all have this in common: parties of men, slaves or Indian, were planning to topple the government and erect their own.

Wars, rebellions, and rumors: what the colonists feared was revolution. On the Danish island of St. John’s in 1733, ninety African slaves seized control of the island and held it for half a year. On Antigua in 1736, a group of black men “formed and resolved to execute a Plot, whereby all the white Inhabitants of the Island were to be murdered, and a new Form of Government to be established by the Slaves among themselves, and they entirely to possess the Island,” its leader, a man named Court, having “assumed among his Country Men . . . the Stile of KING.”64 Sometimes, rebels faced trial; more usually they did not. In waging war against Indians, the English tended to abandon any ideas they had earlier held, about under what circumstances war was just; they tended to wage those wars first, and justify them afterward. And in suppressing and punishing slave rebellions, they abandoned their ideas about trial by jury and the abolition of torture. In Antigua, men charged with conspiracy were tortured under the terms of a new law making grotesque punishments legal; black men were broken on the wheel, starved to death, roasted over a slow fire, and gibbeted alive. On Nantucket in 1738, English colonists believed they had detected a conspiracy of the island’s Indians “to destroy all the English, by first setting Fire to their Houses, in the Night, and then falling upon them with their Fire Arms.” One Indian’s explanation for this plot was “that the English at first took the Land from their Ancestors by Force, and have kept it ever since.”65

Conquest was always fragile, slavery forever unstable. In Jamaica, where blacks outnumbered whites by as many as twenty to one, Africans led by a man named Cudjoe fled plantations and built towns—the English called them “maroon” towns—in the mountains in the island’s interior. The First Maroon War ended in 1739 with a treaty under which the British agreed to acknowledge five Maroon towns, and granted Cudjoe and his followers their freedom and more than fifteen hundred acres of land. It had been a war for independence.

Word of rebellions in Jamaica and Antigua reached the Carolinas and Georgia in a matter of weeks, New England only days later. English colonists on the mainland had family on the islands—and so did their slaves, who, like their owners, traded gossip and news with the arrival of every ship. In 1739, more than a hundred black men rose up in arms and killed more than twenty whites in the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, a colony where blacks outnumbered whites by two to one. “Carolina looks more like a negro country than like a country settled by white people,” one visitor wrote.66 The rebels hoped to make their way to Spanish Florida, where the Spanish had promised fugitive slaves their freedom. As they marched, they shouted, “Liberty!” They were led by a man named Jemmy. Born in Angola, he spoke Kikongo, English, and Portuguese, and, as was very often true of the leaders of slave rebellions, could read and write.67

What laws might quiet these rebellions, what punishments avert these revolutions? This was the question debated by colonial legislatures, in meetinghouses built of brick and wood and stone, even as Indians and Africans threatened to tear those meetinghouses down. In 1740, in the aftermath of the Stono Rebellion, the South Carolina legislature passed An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing Negroes, a new set of rules for relations between the rulers and the ruled. It restricted the movement of slaves, set standards for their treatment, established punishments for their crimes, explained the procedures for their prosecution and codified the rules of evidence for their trials; in capital cases, the charges were to be heard by two justices and a jury comprising at least three men. The law also made it a crime for anyone to teach a slave to write, in hopes of averting the next Jemmy, reading and preaching liberty.68 The English, as Samuel Purchas had remarked, enjoyed a “literall advantage” over the people they ruled, and they meant to keep it.

Word of rebellions spread so fast in the colonies because, while suppressed among slaves, literacy was growing among the colonists, who had begun to print their own pamphlets and books and, especially, their own newspapers. The first printing press brought to Britain’s colonies arrived in Boston in 1639, and the first newspaper in British America, Publick Occurrences, appeared there in 1690. Censored, it lasted for only a single issue, but a second newspaper, the Boston News-Letter, started in 1704, and carried on, printed from a shop on a narrow, cramped street in the narrow and cramped town of Boston, not far from the Common, where sheep grazed and where, at every hour, the lowing of cows could be heard as an unending thrum beneath the tolling of church bells.69

At first, colonial printers reported mostly news from Europe but, more and more, they began reporting the goings-on in neighboring colonies. They also began questioning authority, and insisting on their liberty and, in particular, on the liberty of the press. Its fiercest advocate would be Benjamin Franklin, born in Boston in 1706, the son of a Puritan candle maker and soap-boiler.

Benjamin Franklin was the youngest of his father’s ten sons; his sister Jane, born in 1712, was the youngest of their father’s seven daughters. Benjamin Franklin taught himself to read and write, and then he taught his sister, at a time when girls, like slaves, were hardly ever taught to write (they were, however, taught to read, so that they could read the Bible). He wanted to become a writer. His father could only afford to send him to school for two years (and sent Jane not at all). Another of their brothers, James, became a printer, and at sixteen, Benjamin became his apprentice, just when James Franklin began printing an irreverent newspaper called the New-England Courant.70

The New-England Courant brooked no censor: it was the first “unlicensed” newspaper in the colonies; that is, the colonial government did not grant it a license, and did not review its content before publication. James Franklin decided to use his newspaper to criticize both the government and the clergy, at a time when the two were essentially one, and Massachusetts a theocracy. “The Plain Design of your Paper is to Banter and Abuse the Ministers of God,” Cotton Mather seethed at him. In 1722, James Franklin was arrested for sedition. While he was in prison, his little brother and hardworking apprentice took over printing the Courant, and there appeared on the masthead, for the first time, the name BENJAMIN FRANKLIN.71

While his little sister remained at home dipping candles and boiling soap, young Benjamin Franklin decided to thumb his nose at the government by printing excerpts from a work known as Cato’s Letters, written by two radicals, an Englishman, John Trenchard and a Scot, Thomas Gordon. Cato’s Letters comprises 144 essays about the nature of liberty, including freedom of speech and of the press. “Without freedom of thought,” Trenchard and Gordon wrote, “there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as publick liberty, without freedom of speech: Which is the right of every man.”72 Jane Franklin read those essays as well, and maybe, raised and schooled in a family of rebels, she began to wonder about the rights of every woman, too.

James Franklin fought his prosecution, got out of prison, and kept on printing, but in 1723, young Benjamin Franklin thumbed his nose at his brother, too, and ran away from his apprenticeship, which also meant that he abandoned his sister Jane. Not long after, at the age of fifteen, she was married. Benjamin Franklin began his rags-to-riches rise, a phrase that, at the time, was meant both figuratively and literally: paper is made of rags and Franklin, the first American printer to print paper currency, turned rags to riches. Jane, who would have twelve children and bury eleven of them, lived the far more common life of an eighteenth-century American and especially of a woman, born poor: rags to rags.

Leaving his sister in Boston, Benjamin Franklin eventually settled in the tidy Quaker town of Philadelphia and began printing his own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, in 1729. In its pages, he fought for freedom of the press. In a Miltonian 1731 “Apology for Printers,” he observed “that the Opinions of Men are almost as various as their Faces” but that “Printers are educated in the Belief, that when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.”73

The culture of the fact—the idea of empiricism that had spread from law to government—hadn’t yet quite spread to newspapers, which were full of shipping news and runaway slave ads, and word of slave rebellions and Indian wars, and of the latest meeting of Parliament. Newspapers were interested in truth, but they established truth, as Franklin explained, by printing all sides, and letting them do battle. Printers did not consider it their duty to print only facts; they considered it their duty to print the “Opinions of Men,” as Franklin put it, and let the best man win: truth will out.

But if the culture of the fact hadn’t yet spread to newspapers, it had spread to history. In Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes had written that “The register of Knowledge of Fact is called History.”74 One lesson Americans would learn from the facts of their own history had to do with the limits of the freedom of the press, and this was a fact on which they dwelled, and a liberty they grew determined to protect.

After James Franklin’s tangles with the law in Boston, the next battle over the freedom of the press was staged in New York, the busiest port on the mainland, where African slaves owned by the Dutch had once built a wall at the edge of town, and African slaves owned by the English had taken it down, leaving Wall Street behind. In 1732, a new governor arrived in New York to take up his office in city hall, built by Africans out of the stones that had once formed the wall.

William Cosby was a dandy and a lout. Like the governors of all but four of the mainland colonies, he’d been appointed by the king. He had neither any particular qualifications for the office nor any ties to the people over whom he would rule. He was greedy and corrupt. To topple him, a New York lawyer named James Alexander, a friend of Benjamin Franklin’s, hired a German immigrant named John Peter Zenger to print a new newspaper, the New-York Weekly Journal. The first issue appeared in 1733. Much of the paper consisted of excerpts from Cato’s Letters and like-minded essays written, anonymously, by Alexander. “No Nation Antient or Modern ever lost the Liberty of freely Speaking, Writing, or Publishing their Sentiments but forthwith lost their Liberty in general and became Slaves,” Alexander wrote. By “slaves” he meant what Locke meant: a people subject to the tyranny of absolute and arbitrary rule. He most emphatically didn’t mean the Africans who worked and lived in his own house. One in five New Yorkers was a slave. Slaves built the city, its hulking stone houses, its nail-knocked wooden wharves. They dug the roads, and their own graves, at the Negroes Burying Ground. They carried water for steeping tea and wood for burning. They loaded and unloaded the ships, steps from the slave market. But the liberty to freely speak, write, and publish was not theirs.75

Cosby, brittle and high-handed, like many an imperious and thin-skinned ruler after him, could not abide criticism. He ordered all copies of Zenger’s paper burned, and had Zenger, a poor tradesman who was doing another man’s bidding, arrested for seditious libel.

At a time when political parties were frowned upon by nearly everyone as destructive of the political order—“Party is the madness of many, for the gain of a few,” remarked the poet Alexander Pope in 1727—two political factions nevertheless emerged in the hurly-burly city of New York: the Court Party, which supported Cosby, and the Country Party, which opposed him. “We are in the midst of Party flames,” lamented Daniel Horsmanden, a petty, small-minded placeman appointed by Cosby to the Supreme Court. But three thousand miles from London, weeks of sailing time away from any relief from the abuses of a tyrannical governor, New Yorkers began to believe that parties might be “not only necessary in free Government, but of great service to the Public.” As one New Yorker wrote in 1734, “Parties are a check upon one another, and by keeping the Ambition of one another within Bounds, serve to maintain the public Liberty.”76

The next year, Zenger was tried before the colony’s Supreme Court, in that city hall of stone. Alexander, whose authorship of the essays remained unknown, served as Zenger’s lawyer until the court’s chief justice, a Cosby appointee, had him disbarred. Zenger was then represented by Andrew Hamilton, an especially shrewd lawyer from Philadelphia. Hamilton did not dispute that Zenger had printed articles critical of the governor. Instead, he argued that everything that Zenger had printed was true—Cosby really was a dreadfully bad governor—and dared a jury to disagree. In his closing argument, he both drew on Cato’s Letters and elevated the controversy in New York to epic proportions, in a rhetorical move that would become commonplace by the 1760s, as more colonies bridled at English rule. The question, Hamilton told the jury, “is not the Cause of a poor Printer, nor of New-York alone.” No, “It is the best Cause. It is the Cause of Liberty.”77

The jury found Zenger not guilty. Cosby died ignominiously the next year. But New Yorkers’ zeal for parties did not abate. There was even talk, for a time, of a civil war. The Country Party went on to dispute the authority of Cosby’s beleaguered successor, George Clarke, who reported to London, astounded, that New Yorkers believed that “if a Governor misbehave himself they may depose him and set up another.”78

And yet the idea that a people might depose a tyrant and replace him with one of themselves as a ruler was not, of course, such an astonishing notion: it lay behind every slave rebellion. In the years after the Zenger trial, fear that just such a conspiracy was in the minds of the city slaves became an obsession of their owners. In 1741, when fires broke out across the city, and Clarke’s own mansion—the governor’s mansion—burned to the ground, many New Yorkers became convinced that the fires had been set by the city’s slaves, plotting a rebellion, not unlike the rebellions that had taken place in the 1730s in Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica, and South Carolina—and, if more violent, not altogether unlike the rebellion waged by the Country Party against Cosby. Were these not yet more terrifying party flames?

“The Negroes are rising!” New Yorkers shouted from street corners. Many of the city’s slaves had come to New York from the Caribbean; not a few had come from islands known for rebellion. Caesar, owned by a Dutch baker, was able to read and write, like Jemmy, the leader of South Carolina’s Stono Rebellion. Caesar had also fathered a child with a white woman—another crossing of racial lines. He was one of the first men arrested in New York. There followed whispered rumors and tortured confessions. Daniel Horsmanden decided that “most of the Negroes in town were corrupted” and that they planned to murder all the whites and elect Caesar as their governor.

What happened in New York in the 1730s and 1740s set a pattern in American politics. At Horsmanden’s urging, more than 150 black men in the city were arrested, thrown in prison, and interrogated. Many were tried. The outcomes of the trials of Zenger and men like Caesar could hardly have been more different. White New Yorkers had decided that they could bear the singe of party flames: political dissent, in the form of a newspaper and a political party opposed to the royally appointed governor, they could tolerate. But dissent in the form of a slave rebellion they could not. The very court that had acquitted Zenger tried and convicted thirty black men, sentencing thirteen to be burned at the stake and seventeen more to be hanged, along with four whites. “Bonfires of the Negros,” one colonist called the executions in 1741. But these, too, were party flames. Most of the rest of the black men who had been arrested were taken from their families and sold to the Caribbean, a fate many considered to be worse than death. Caesar, who at the gallows refused to confess, was hung in chains, his rotting body displayed for months, in hopes that his “Example and Punishment might break the Rest, and induce some of them to unfold this Mystery of Iniquity.”79 But the mystery of iniquity wasn’t conspiracy; it was slavery itself.

Waves of rebellion lashed the shores of the English Atlantic for more than a century, from Boston to Barbados, from New York to Jamaica, from the Carolinas and back again to London. “Rule, Britannia, rule the waves; / Britons never will be slaves,” read a poem written in England in 1740 that became the empire’s anthem, and America’s anthem, too. It was lost on no one that the loudest calls for liberty in the early modern world came from a part of that world that was wholly dependent on slavery.

Slavery does not exist outside of politics. Slavery is a form of politics, and slave rebellion a form of violent political dissent. The Zenger trial and the New York slave conspiracy were much more than a dispute over freedom of the press and a foiled slave rebellion: they were part of a debate about the nature of political opposition, and together they established its limits. Both Cosby’s opponents and Caesar’s followers allegedly plotted to depose the governor. One kind of rebellion was celebrated, the other suppressed—a division that would endure. In American history, the relationship between liberty and slavery is at once deep and dark: the threat of black rebellion gave a license to white political opposition. The American political tradition was forged by philosophers and by statesmen, by printers and by writers, and it was forged, too, by slaves.

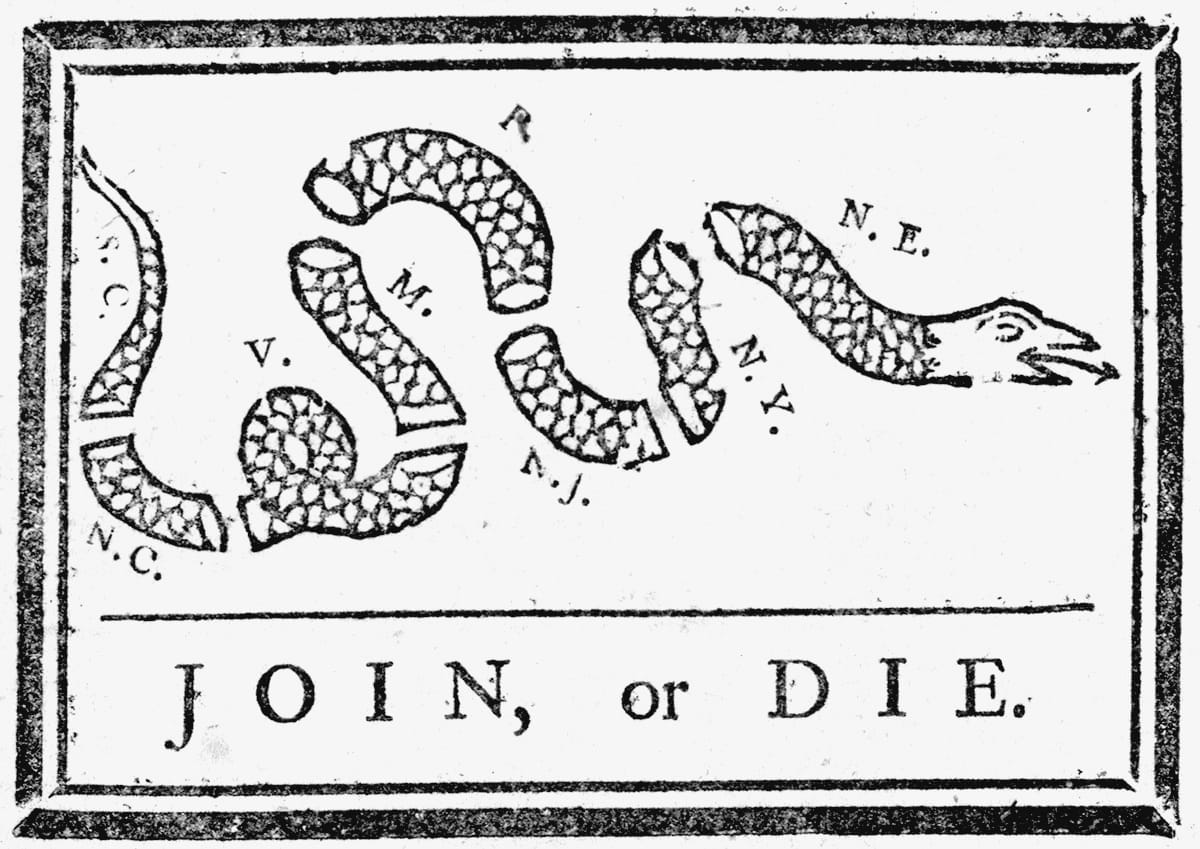

ON MAY 9, 1754, Benjamin Franklin, a man of parts, printed a woodcut in the Pennsylvania Gazette. It was titled “JOIN, or DIE,” and it pictured a snake, chopped into eight pieces, labeled, by their initials, from head to tail: New England, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

For centuries, the kings and queens of Europe had fought over how to divvy up North America, as if the land were a cake to be carved. They staked their claims on the ground, naming towns and waging wars, and they staked their claims with maps, drawing lines and coloring shapes. In 1681, a map called “North America Divided into its Principall Parts where are distinguished the several States which belong to the English, Spanish, and French” was bound in an atlas printed in London, with colors inked by hand. It took only passing notice of natives of these lands, vaguely noting the “Apache” near New Mexico. Like many maps, it became very quickly outdated. England and Scotland formed a union in 1707 and went on waging an on-again, off-again war with France and Spain that spilled over onto the North American continent, where both Britain and France allied with Indians. The colonists named these wars after the kings or queens under whose reign they fell: King William’s War (1689–1697), Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713), and King George’s War (1744–48). North America was divided into its principal parts, and then it was divided again, and again.