Three

OF WARS AND REVOLUTIONS

BENJAMIN LAY STOOD BARELY OVER FOUR FEET TALL, hunchbacked and bowed, with a too-big head and a barrel chest and legs so spindly it did not appear possible they could bear his weight. As a boy in England, he’d worked on his brother’s farm before being apprenticed to a glove maker, shearing and stitching skins. At twenty-one, he went to sea; in his hammock, by the light of tallow, he read books. Lay liked to call himself “a poor common sailor and an illiterate man,” but in truth, he was widely read and well traveled. He sailed to Syria and to Turkey, where he met “four men that had been 17 Years Slaves”—Englishmen who’d been enslaved by Muslims. He swabbed decks with men who’d sailed on English slave-trading ships, carrying Africans. He heard tales of dark and terrible cruelties. In 1718, Lay sailed to Barbados, where he saw people branded and tortured and beaten, starved and broken; he decided that everything about this arrangement was an offense against God, who “did not make others to be Slaves to us.”1

Lay and his also hobbled wife—a Quaker preacher with a crooked back—left Barbados after only eighteen months and returned to England. Maybe it was something about being so bowed, so easily dismissed, so set aside, that left them reeling at the horrors of slavery, the breaking of backs, the butchering of bodies. In 1732, they embarked for Pennsylvania to join William Penn’s Holy Experiment. In Philadelphia, Lay turned bookseller, selling Bibles and primers along with the works of his favorite poets, like John Milton’s Paradise Lost, and of his favorite philosophers, like Seneca’s Morals, essays on ethics by an ancient Roman stoic.2 He traveled from town to town and from colony to colony, only ever on foot—he would not spur a horse—to denounce slavery before governors and ministers and merchants. “What a Parcel of Hypocrites and Deceivers we are,” he said.3 His arguments fell on deaf ears. After his wife died, he lost his last restraint. In 1738, he went to a Quaker meeting in New Jersey carrying a Bible whose pages he’d removed; he’d placed inside the book a pig’s bladder filled with pokeberry juice, crimson red. “Oh all you negro masters who are contentedly holding your fellow creatures in a state of slavery,” he cried, entering the meetinghouse, “you who profess ‘to do unto all men as ye would they should do unto you,’” you shall see justice “in the sight of the Almighty, who beholds and respects all nations and colours of men with an equal regard.” Then, taking his Bible from his coat and a sword from his belt, he pierced the Bible with the sword. To the stunned parishioners, it appeared to burst with blood, as if by a miracle, spattering their heads and staining their clothes, as Lay thundered, from his tiny frame: “Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who enslave their fellow creatures.”4

The next month, Benjamin Franklin printed Lay’s book, All Slave-Keepers That keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, a rambling and furious three-hundred-page polemic. Franklin sold the book at his shop, two shillings a copy, twenty shillings a dozen. Lay handed out copies for free.5 Then he became a hermit. Outside of Philadelphia, he carved a cave out of a hill. Inside, he stowed his library: two hundred books of theology, biography, poetry, and history. He’d decided to protest slavery by refusing to eat or drink or wear or use anything that had been made with forced labor. He also refused to eat animals. He lived on water and milk, roasted turnips and honey; he kept bees and spun flax and stitched clothes. Franklin used to visit him in his cave. Franklin at the time owned a “Negro boy” named Joseph. By 1750 he owned two more slaves, Peter and Jemima, husband and wife. Lay pressed him and pressed him: By what right?

Franklin, himself a runaway, knew, as every printer knew, and every newspaper reader knew, that every newspaper contained, within its pages, tales of revolution, in the stories of everyday escapes. Among them, in those years, were the following. Bett, who had “a large scar on her breast,” ran away in 1750 from a man on Long Island. She was wearing nothing but a petticoat and a jacket in the bitter cold of January. Primus, who was thirty-seven, and missing the first joint of one of his big toes, probably a punishment for an earlier attempted escape, ran away from Hartford in 1753, carrying his fiddle. Jack, “a tall slim fellow, very black, and speaks good English,” left Philadelphia in July of 1754. Sam, a carpenter, thirty, “a dark Mulatto,” ran away from a shop in Prince George’s County, Maryland, in the winter of 1755. “He is supposed to be lurking in Charles County,” his owner wrote, “where a Mulatoo Woman lives, whom he has for some Time called his Wife; but as he is an artful Fellow, and can read and write, it is probable he may endeavor to make his Escape out of the Province.” Will, forty, ran away from a plantation in Virginia in the summer of 1756; he was, his owner said, “much scar’d on his back with a whip.”6

When Benjamin Franklin began writing his autobiography, in 1771, he turned the story of his own escape—running away from his apprenticeship to his brother James—into a metaphor for the colonies’ growing resentment of parliamentary rule. James’s “harsh and tyrannical Treatment,” Franklin wrote, had served as “a means of impressing me with that Aversion to arbitrary Power that has stuck to me thro’ my whole Life.”7 But that was also the story of every runaway slave ad, testament after testament to an aversion to arbitrary power.

In April 1757, before sailing to London, Franklin drafted a new will, in which he promised Peter and Jemima that they would be freed at his death. Two months later, when Franklin reached London, he wrote to his wife, Deborah, “I wonder how you came by Ben. Lay’s picture.” She had hung on the wall an oil portrait of the dwarf hermit, standing outside his cave, holding in one hand an open book.8

The American Revolution did not begin in 1775 and it didn’t end when the war was over. “The success of Mr. Lay, in sowing the seeds of . . . a revolution in morals, commerce, and government, in the new and in the old world, should teach the benefactors of mankind not to despair, if they do not see the fruits of their benevolent propositions, or undertakings, during their lives,” Philadelphia doctor Benjamin Rush later wrote. Rush signed the Declaration of Independence and served as surgeon general of the Continental army. To him, the Revolution began with the seeds sown by people like Benjamin Lay. “Some of these seeds produce their fruits in a short time,” Rush wrote, “but the most valuable of them, like the venerable oak, are centuries in growing.”9

In 1758, when Benjamin Lay’s portrait hung in Benjamin Franklin’s house, the Philadelphia Quaker meeting formally denounced slave trading; Quakers who bought and sold men were to be disavowed. When Lay heard the news he said, “I can now die in peace,” closed his eyes, and expired.10 Within the year, another Pennsylvania Quaker, Anthony Benezet, published a little book called Observations on the Inslaving, Importing and Purchasing of Negroes, in which he argued that slavery was “inconsistent with the Gospel of Christ, contrary to natural Justice and the common feelings of Humanity, and productive of infinite Calamities.”11 Bett and Primus and Jack and Sam and Will had not run away for nothing.

There were not one but two American revolutions at the end of the eighteenth century: the struggle for independence from Britain, and the struggle to end slavery. Only one was won.

I.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN WROTE a new will before he sailed to London in 1757 because Britain and France were attacking each other’s ships, and he feared his might get sunk. The fighting had broken out three years before, only weeks after Franklin printed his “JOIN, or DIE” snake, slithering across a page. The battling had begun not at sea but on land, in Franklin’s own colony of Pennsylvania. Britain sorely wanted land that the French had claimed in the Ohio Valley, complaining, “the French have stripped us of more than nine parts in ten of North America and left us only a skirt of coast along the Atlantic shore.”12 Leaving that skirt behind, English settlers had begun advancing farther and farther inland, into territories occupied by native peoples but claimed by France. To stop them, the French had starting building forts along their borders. The inevitable skirmish came in May 1754, when a small force of Virginia militiamen and their Indian allies, led by twenty-one-year-old Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, ambushed a French camp at the bottom of a glen.

Born in 1732 in Westmoreland County, Virginia, Washington had inherited his first human property at the age of ten, traveled to the West Indies as a young man, and accepted his first military commission at the age of twenty. Tall, imposing, and grave, he cut a striking figure. He was, as yet, inexperienced, and his first battle proved disastrous for the Virginians, who retreated to a nearby meadow and hastily erected a small wooden garrison that they named, suitably, Fort Necessity. After losing a third of his men in a single day, like so many stalks of wheat hacked down by a scythe, the young lieutenant surrendered. Only weeks later, delegates from the colonies met in Albany to consider Franklin’s proposal to form a defensive union, and, though they approved the plan, their colonial assemblies rejected it.

The war came all the same, a war over the trade in the East Indies, over fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland, over shipping along the Mississippi River, and over sugar plantations on West Indian islands. Like all wars, its costs were borne most heavily by the poor, who did the fighting, while traders, who sold weapons and supplied soldiers, saw profits. “War is declared in England—universal joy among the merchants,” wrote one New Yorker in 1756.13 The colonists called it the French and Indian War, after the people they were fighting in North America, but the war stretched from Bengal to Barbados, drew in Austria, Portugal, Prussia, Spain, and Russia, and engaged armies and navies in the Atlantic and the Pacific, in the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. The French and Indian War did what Franklin’s woodcut could not: as far north as New England, it brought Britain’s North American colonies together. Not least, it also led to the publication of an American Magazine, printed in Philadelphia and sent to subscribers from Jamaica to Boston. As its editors boasted: “Our readers are a numerous body, consisting of all parties and persuasions, thro’ British America.”14

During earlier wars between the British and the French, the colonists had mostly done their own fighting, raising town militias and provincial armies. But in 1755, Britain sent regiments of its regular army to North America, under the command of the stubborn and tempestuous General Edward Braddock. Franklin viewed the appointment of Braddock as the Crown’s attempt to keep the colonies weak. “The British Government not chusing to permit the Union of the Colonies, as propos’d at Albany, and to trust that Union with their Defence, lest they should thereby grow too military,” he wrote, they “sent over General Braddock with two Regiments of Regular English Troops.”15 Charged with moving the French line, Braddock began to prepare to engage the French at Fort Duquesne, at the mouth of the Ohio River, on the western edge of the frontier. Franklin warned the general that his planned route, as serpentine as a snake’s path, would expose his troops to Indian attack. “The slender Line near four Miles long, which your Army must make,” he explained, “may expose it to be attack’d by Surprize in its Flanks, and to be cut like a Thread into several Pieces.” Braddock, it would seem, gave Franklin a condescending smile, the same smile the king gave his subjects. “These Savages may indeed be a formidable Enemy to your raw American Militia,” he said. “But upon the King’s regular and disciplin’d Troops, Sir, it is impossible they should make any Impression.”

Braddock and his troops proceeded with their march. Along the way, they plundered the people. Before long, many colonists found themselves fearing the British army as much as the French. “This was enough to put us out of Conceit of such Defenders if we had really wanted any,” wrote Franklin bitterly. Braddock’s troops were ignominiously defeated and Braddock was shot. During a beleaguered retreat, the dying general was carried off the field by Washington.16

Nothing daunted, William Pitt, the new secretary of state, determined to win the war and settle Britain’s claims in North America once and for all. In his honor, when the British and American troops finally seized Fort Duquesne, they renamed it Fort Pitt. But Pitt’s lasting legacy would lie in the staggering cost of the war. Before long, forty-five thousand troops were fighting in North America; half were British soldiers, half were American troops. Pitt promised the colonies the war would be fought “at His Majesty’s expense.” It was the breaking of that promise, and the laying of new taxes on the colonies, that would, in the end, lead the colonists to break with England.

Even before then, the most expensive war in history cost Britain the loyalty of its North American colonists. British troops plundered colonial homes and raided colonial farms. Like Braddock, they also sneered at the ineptness of colonial militias and provincial armies. In close quarters, in camps and on marches, few on either side failed to notice the difference between British and American troops. The British found the colonists inexpert, undisciplined, and unruly. But to the Americans, few of whom had ever been to Britain, it was the British who were wanting: lewd, profane, and tyrannical.17

A clash proved difficult to avoid. In the British army, rank meant everything. British officers were wealthy gentlemen; enlisted men were drawn from the masses of the poor. In the colonial forces, there were hardly any distinctions of rank. In Massachusetts, one in every three men served in the French and Indian War, whether they were penniless clerks or rich merchants. In any case, differences of title and rank that existed in Britain did not exist in the colonies, at least among free men. In England, fewer than one in five adult men could vote; in the colonies, that proportion was two-thirds. The property requirements for voting were met by so many men that Thomas Hutchinson, who lost a bid to become governor in 1749, complained that the town of Boston was an “absolute democracy.”18

“There is more equality of rank and fortune in America than in any other country under the sun,” South Carolina governor Charles Pinckney declared. This was true so long as no one figured in that calculation—as Pinckney never would—people who were property, a number that included Pinckney’s forty-five slaves at Snee Farm, fifty-five people who constituted the source of his family’s wealth. Among them were Cyrus, a carpenter (valued by Pinckney at £120); Cyrus’s children, Charlotte (£80), Sam (£40), and Bella (£20); his granddaughter Cate (£70); and a very old woman named Joan, who might have been Cyrus’s mother. Pinckney placed the value of this great-grandmother at zero; she was, to him, worthless.19

In 1759, British and American forces defeated the French in Quebec, a stunning victory that led the Iroquois to abandon their longstanding position of neutrality and join with the English, which turned the tide of the war. In August 1760, the English captured Montreal, and the North American part of the war ended only six hundred miles from where it began, at the ragged western edge of the British Empire.

Weeks later, young George III was crowned king of Great Britain. Twenty-two and strangely shy, he was a boy of a man, dressed in gold, his white-buckled shoes tripping on a train of ermine. He presented himself to an uneasy world as a defender of the Protestant faith and of English liberties. He had declared, as Prince of Wales, “The pride, the glory of Britain, and the direct end of its constitution is political liberty.”20 But by now, while his subjects in North America welcomed the coronation of their new king, they might as easily have recalled the wisdom of a proverb that Franklin had printed twenty years earlier in Poor Richard’s Almanac: “The greatest monarch on the proudest throne, is oblig’d to sit upon his own arse.”21

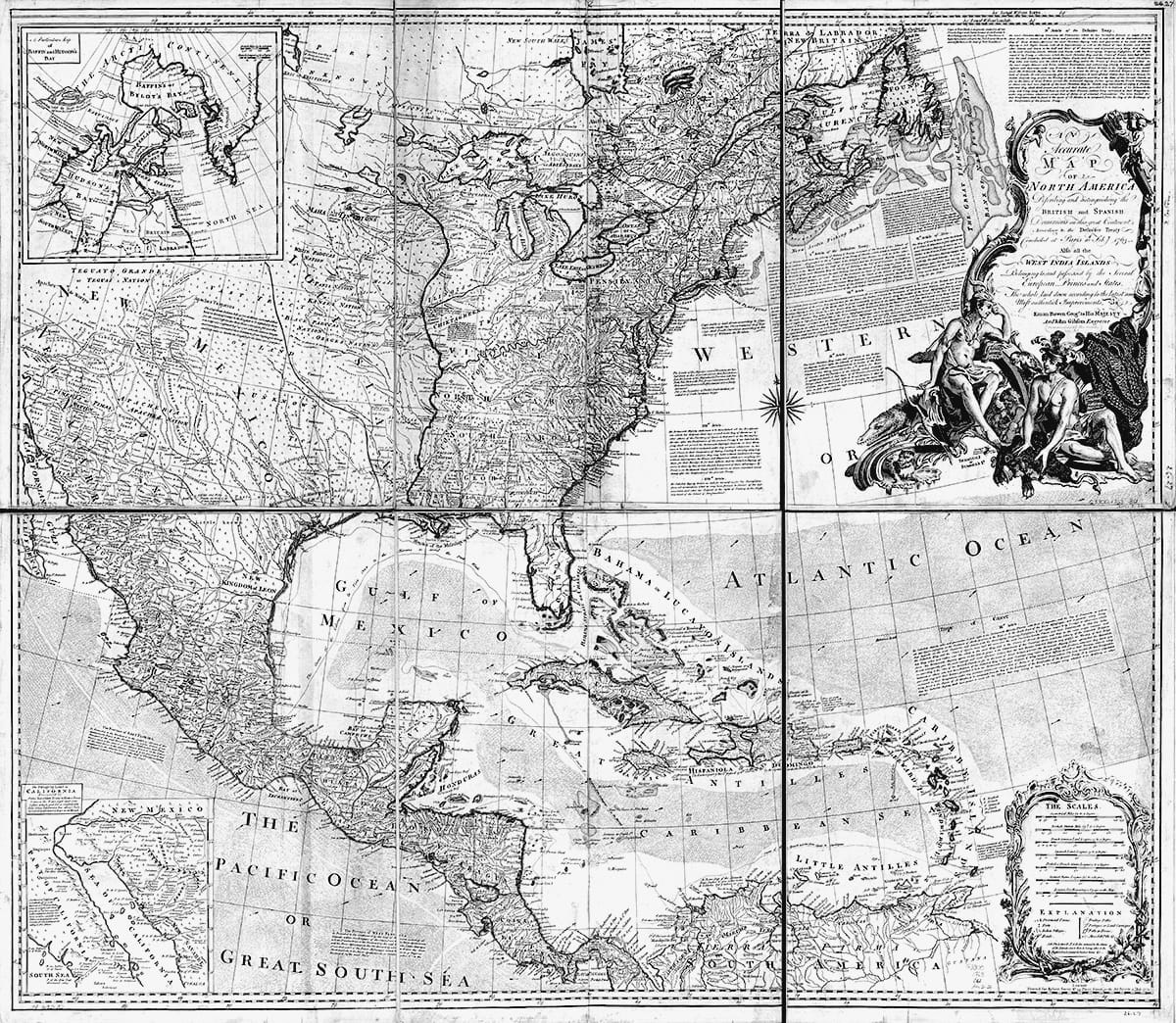

Mapmakers sharpened their quills to redraw the map of North America when peace was reached in 1763. Under its terms, France ceded Canada and all of New France east of the Mississippi to Britain; France granted all its land to the west of the Mississippi, territory known as Louisiana, to Spain; and Spain yielded Cuba and half of Florida to Britain. Britain’s skirt of settlement along the Atlantic looked now like bolts of fabric unfurled on the dressmaker’s floor.

“We in America have certainly abundant reason to rejoice,” the leading Massachusetts lawyer James Otis Jr. wrote from Boston in 1763. “The British dominion and power may now be said, literally, to extend from sea to sea, and from the great river to the ends of the earth.” If the war had strained the colonists’ relationship to the empire, the peace had strengthened both the empire and the colonists’ attachment to it. Added Otis, “The true interests of Great Britain and her plantations are mutual, and what God in his providence has united, let no man dare attempt to pull asunder.”22

But the war had left Britain nearly bankrupt. The fighting had nearly doubled Britain’s debt, and Pitt’s promise began to waver. Then, too, the king’s ministers determined that defending the empire’s new North American borders would require ten thousand troops or more, especially after a confederation of Indians led by an Ottawa chief named Pontiac captured British forts in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley. Pontiac, it was said, had been stirred to action by a prophecy of the creation on earth of a “Heaven where there was no White people.”23 Fearing the cost of suppressing more Indian uprisings, George III issued a proclamation decreeing that no colonists could settle west of the Appalachian Mountains, a line that many colonists had already crossed.

In 1764, to pay the war debt and fund the defense of the colonies, Parliament passed the American Revenue Act, also known as the Sugar Act. Up until 1764, the colonial assemblies had raised their own taxes; Parliament had regulated trade. When Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which chiefly required stricter enforcement of earlier measures, some colonists challenged it by arguing that, because the colonies had no representatives in Parliament, Parliament had no right to levy taxes on them. The Sugar Act wasn’t radical; the response to it was radical, a consequence of the growing power of colonial assemblies at a time when the idea of representation was gaining new force.

Taxes are what people pay to a ruler to keep order and defend the realm. In the ancient world, landowners paid in crops or livestock, the landless with their labor. Levying taxes made medieval European monarchs rich; only in the seventeenth century did monarchs begin to cede the power to tax to legislatures.24 Taxation became tied to representation at the very time that England was founding colonies in North America and the Caribbean, which was also the moment at which the English had begun to dominate the slave trade. In the 1760s, the two became muddled rhetorically. Massachusetts assemblyman Samuel Adams asked, “If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal Representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Character of free Subjects to the miserable State of tributary Slaves?”25

Taxation without representation, men like Adams argued, is rule by force, and rule by force is slavery. This argument had to do, in part, with debt. “The Borrower is a slave to the Lender,” as Franklin once put it in Poor Richard’s Almanack.26 Debtors could be arrested and sent to debtors’ prison.27 Debtors’ prison was far more common in England than in the colonies, which were in many ways debtors’ asylums.28 But if there was an unusual tolerance for debt in the colonies, there was also an unusual amount of it, and in the 1760s there was, suddenly, rather a lot more of it. The governor of Massachusetts reported that “a Stop to all Credit was expected” and even “a general bankruptcy.”29 The end of the French and Indian War led to a contraction of credit, followed by a crippling depression and, especially in the South, several years of poor crops. Tobacco plantation owners in the Chesapeake found themselves heavily indebted to merchants in England, who, themselves strapped, were quite keen to collect those debts. These planters, in particular, found it politically useful to describe themselves as slaves to their creditors.30 During these same years, though, the sugar colonies in the Caribbean prospered, not least because the Sugar Act enforced a monopoly: under its terms, colonists on the mainland had to buy their sugar from the British West Indies.31 This difference did not pass unobserved. “Our Tobacco Colonies send us home no such wealthy planters as we see frequently arrive from our sugar islands,” Adam Smith would remark in The Wealth of Nations.32

Parliament’s next revenue act induced a still more strenuous response. A 1765 Stamp Act required placing government-issued paper stamps on all manner of printed paper, from bills of credit to playing cards. Stamps were required across the British Empire, and, by those standards, the tax levied in the colonies was cheap: colonists paid only two-thirds of what Britons paid. But in the credit-strained mainland colonies, this proved difficult to bear. Opponents of the act began styling themselves the Sons of Liberty (after the Sons of Liberty in 1750s Ireland) and describing themselves as rebelling against slavery. A creditor was “lord of another man’s purse”; hadn’t British creditors and Parliament itself swindled North American debtors of their purses, and their liberty, too? Was not Parliament making them slaves? John Adams, a twenty-nine-year-old Boston lawyer and leader of the Stamp Act opposition, wrote: “We won’t be their negroes.”33

The colonies were bound up in a growing credit crisis that would engulf the whole of the British Empire, from Virginia planters to Scottish bankers to East India Company tea exporters. But there were American particulars, too: with the Stamp Act, a tax on all printed paper, including newspapers, Parliament levied a tax that cost the most to the people best able to complain about it: the printers of newspapers. “It will affect Printers more than anybody,” Franklin warned, begging Parliament to reconsider.34 Printers from Boston to Charleston argued that Parliament was trying to reduce the colonists to a state of slavery by destroying the freedom of the press. The printers of the Boston Gazette refused to buy stamps and changed the paper’s motto to “A free press maintains the majesty of the people.” In New Jersey, a printer named William Goddard issued a newspaper called the Constitutional Courant, with Franklin’s segmented snake on the masthead. This time, asked whether to join or die, the colonies decided to join.

In October, the month before the Stamp Act was to take effect, twenty-seven delegates from nine colonies met in a Stamp Act Congress in New York’s city hall, where John Peter Zenger had been tried in 1735 and Caesar in 1741. The Stamp Act Congress collectively declared “that it is inseparably essential to the Freedom of a People, and the undoubted Right of Englishmen, that no Taxes be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their Representatives.”35 When they dined, they sent their leftovers to the debtors confined in a prison in the building’s garret, making common cause with men deprived of their liberty by creditors.36

The sovereignty of the people, the freedom of the press, the relationship between representation and taxation, debt as slavery: each of these ideas, with origins in England, found a place in the colonists’ opposition to the Stamp Act. Still, Parliament professed itself baffled. In 1766, Benjamin Franklin appeared before the House of Commons to explain the colonists’ refusal to pay the tax. At sixty, Franklin presented himself as at once a man of the world and an American provincial, wily and plainspoken, sophisticated and homespun.

“In what light did the people of America use to consider the Parliament of Great Britain?” the ministers asked.

“They considered the Parliament as the great bulwark and security of their liberties and privileges, and always spoke of it with the utmost respect and veneration,” was Franklin’s reply.

“And have they not still the same respect for Parliament?”

“No; it is greatly lessened.”

If the colonists had lost respect for Parliament, why had this come to pass? On what grounds did they object to the Stamp Tax? There was nothing in Pennsylvania’s charter that forbade Parliament from exercising this authority.

It’s true, Franklin admitted, there was nothing specifically to that effect in the colony’s charter. He cited, instead, their understanding of “The common rights of Englishmen, as declared by Magna Charta,” as if the colonists were the barons of Runnymede, King George their King John, and Magna Carta their constitution.

“What used to be the pride of the Americans?” Parliament wanted to know.

“To indulge in the fashions and manufactures of Great Britain.”

“What is now their pride?”

“To wear their old clothes over again till they can make new ones.”37

Here was Poor Richard, again with his proverbs.

And yet this defiance did not extend to Quebec, or to the sugar islands, where the burden of the Stamp Tax was actually heavier. Thirteen colonies eventually cast off British rule; some thirteen more did not. Colonists from the mainland staged protests, formed a congress, and refused to pay the stamp tax. But, except for some vague and halfhearted objections expressed on Nevis and St. Kitts, British planters in the West Indies barely uttered a complaint. (South Carolina, whose economy had more in common with the British West Indies than with the mainland colonies, wavered.) They were too worried about the possibility of inciting yet another slave rebellion.38

On the mainland, whites outnumbered blacks, four to one. On the islands, blacks outnumbered whites, eight to one. One-quarter of all British troops in British America were stationed in the West Indies, where they protected English colonists from the ever-present threat of slave rebellion. For this protection, West Indian planters were more than willing to pay a tax on stamps. Planters in Jamaica were still reeling from the latest insurrection, in 1760, when an Akan man named Tacky had led hundreds of armed men who burned plantations and killed some sixty slave owners before they were captured. The reprisals had been ferocious: Tacky’s head was impaled on a stake, and, as in New York in 1741, some of his followers were hung in chains while others were burned at the stake. And still the rebellions continued, for which island planters began to blame colonists on the mainland: Did the Sons of Liberty realize what they were saying? “Can you be surprised that the Negroes in Jamaica should endeavor to Recover their Freedom,” one merchant fumed, “when they dayly hear at the Tables of their Masters, how much the Americans are applauded for the stand they are making for theirs”?39

Unsurprisingly, the island planters’ unwillingness to join the protest against the Stamp Act greatly frustrated the Sons of Liberty. “Their Negroes seem to have more of the spirit of liberty than they,” John Adams complained, asking, “Can no punishment be devised for Barbados and Port Royal in Jamaica?” Adams was the rare man whose soaring ambition matched his talents. He would learn to restrain his passions better. But in the 1760s, his anger at those who refused to support the resistance was unchecked. The punishment the Sons of Liberty decided upon came in the form of a boycott of Caribbean goods. In language even more heated than Adams’s, patriot printers damned “the SLAVISH Islands of Barbados and Antigua—Poor, mean spirited, Cowardly, Dastardly Creoles,” for “their base desertion of the cause of liberty, their tame surrender of the rights of Britons, their mean, timid resignation to slavery.”40

Planters bridled at the attack and floundered under the effects of the boycott. “We are likely to be miserably off for want of lumber and northern provisions,” one Antigua planter wrote, “as the North Americans are determined not to submit to the Stamp Act.”41 But they did not yield. And some began to consider their northern neighbors to be mere blusterers. “I look on them as dogs that will bark but dare not stand,” complained one planter from Jamaica.42

Nor were the West Indian planters wrong to worry that one kind of rebellion would incite another. In Charleston, the Sons of Liberty marched through the streets, chanting, “Liberty and No Stamps!” only to be followed by slaves crying, “Liberty! Liberty!” And not a few Sons of Liberty made this same leap, from fighting for their own liberty to fighting to end slavery. “The Colonists are by the law of nature free born, as indeed all men are, white or black,” James Otis Jr. insisted, in a searing tract called Rights of the British Colonists, Asserted, published in 1764, only months after he had rejoiced about the growth of Britain’s empire. Brilliant and unstable, Otis would later lose his mind (before his death in 1783, when he was struck by lightning, he had taken to running naked through the streets). But in the 1760s, he, better than any of his contemporaries, saw the logical extension of arguments about natural rights. He found it absurd to suggest that it could be “right to enslave a man because he is black” or because he has “short curl’d hair like wool.” Slavery, Otis insisted, “is the most shocking violation of the law of nature,” and a source of political contamination, too. “Those who every day barter away other men’s liberty, will soon care little for their own,” he warned.43

Otis’s readers picked and chose which parts of his treatise to hold close and which parts to shed. But something had been set loose in the world, a set of unruly ideas about liberty, equality, and sovereignty. In 1763, when Benjamin Franklin visited a school for black children, he admitted that his mind had changed. “I . . . have conceiv’d a higher Opinion of the natural Capacities of the black Race, than I had ever before entertained,” he wrote a friend. In Virginia, George Mason began to have doubts about slavery, sending to George Washington, in December of 1765, an essay in which he argued that slavery was “the primary Cause of the Destruction of the most flourishing Government that ever existed”—the Roman republic—and warning that it might be the destruction of the British Empire, too.44

Debt, taxes, and slavery weren’t the only issues raised in the political debates of the 1760s. The intensity of the debate strengthened new ideas about equality, too. “Male and female are all one in Christ the Truth,” Benjamin Lay had argued, expressing an idea that drew on a wealth of seventeenth-century Quaker writings about spiritual equality. “Are not women born as free as men?” Otis asked.45 Even Benjamin Franklin’s long-suffering sister Jane began to entertain this notion. In 1765, Jane Franklin lost her husband, a saddler and ne’er-do-well named Edward Mecom, who had sickened while in debtors’ prison, and she’d begun taking in, as boarders, members of the Massachusetts Assembly. “I do not Pretend to writ about Politics,” she once wrote to her brother, “tho I Love to hear them.”46 This was false modesty, a “fishing for commendation” about which her brother so often chided her. At her table, there was a lot for her to listen to, when, in 1766, Otis was elected as Speaker of the Massachusetts Assembly but the royally appointed governor refused to accept the results of the election. If Jane Franklin wasn’t, as yet, willing to write about politics, she had heard much worth pondering. Not long after the governor overturned the results of the election, she wrote to her brother to ask that he send her “all the Pamphlets & Papers that have been Printed of yr writing.”47 She decided to make a study of politics.

In 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. The repeal “has hushed into silence almost every popular Clamour, and composed every Wave of Popular Disorder into a smooth and peaceful Calm,” John Adams wrote in his diary.48 “I congratulate you & my Countrymen on the Repeal,” Franklin wrote to his sister.49 The week after the news reached Boston, its town meeting voted in favor of “the total abolishing of slavery from among us.”50 Pamphleteers began arguing for a colony-wide antislavery law; others counseled waiting until the end of the battle with Parliament, because, even as it repealed the Stamp Act, Parliament had passed the Declaratory Act, asserting its authority to make laws “in all cases whatsoever.” The next year, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, taxes on lead, paper, paint, glass, and tea. When this, too, led to riots and boycotts, the prime minister sent to Boston two regiments of the British army to enforce the law.

“The whol conversation of this Place turns upon Politics,” Jane reported to her brother. The Boston Town meeting resolved that “a series of occurrences . . . afford great reason to believe that a deep-laid and desperate plan of imperial despotism has been laid, and partly executed, for the extinction of all civil liberty.” When troops fired into a crowd in March 1770, killing five men, the Sons of Liberty called it a “massacre” and cried for relief from the tyranny of a standing army. But on the islands, planters called not for less military presence but more, the colonial assembly on St. Kitts begging the king to send troops to protect the colonists from “the turbulent and savage dispositions of the Negroes ever prone to Riots and Rebellions.”51

And still, the zeal for liberty raised the question of ending slavery. The Worcester Town Meeting called for a law prohibiting the importing and buying of slaves; by 1766, an antislavery bill had been introduced into the Massachusetts Assembly. But, mindful of how the question of slavery had severed the island colonies from the mainland, many in Massachusetts feared that further antislavery sentiment would sever the northern colonies from the southern. “If passed into an act, it should have a bad effect on the union of the colonies,” one assemblyman wrote to John Adams in 1771, when the bill came up for a vote.52 The next year, the Court of King’s Bench in London took up the case of Somerset v. Stewart. Charles Stewart, a British customs officer in Boston, had purchased an African man named James Somerset. When Stewart was recalled to England in 1769, he brought Somerset with him. Somerset escaped but was recaptured. Stewart, deciding to sell him to Jamaica, had him imprisoned on a ship. Somerset’s friends brought the case to court, where the justice, Lord Mansfield, found that nothing in English common law supported Stewart’s position. Somerset was set free.

The Somerset case taught people held in slavery two lessons: first, they might look to the courts to secure their freedom, and, second, they had a better shot at winning it in Britain than in any of its colonies. They began to act. Relying on the same logic that James Otis Jr. had expounded, they petitioned the courts for their freedom: “We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them,” read a petition filed by four black men in Boston in April 1773. And they tried to escape to England: in Virginia that September, a slave couple ran away hoping to secure their freedom by reaching London, holding, as one observer put it, “a notion now too prevalent among the Negroes.”53

This struggle for liberty was lost as the colonists returned, instead, to their battles with Parliament. The London-based East India Company was at risk of bankruptcy, partly due to the colonial boycott, but more due to a famine in Bengal, the military costs it incurred there, and collapsing stock value consequent to the empire-wide credit crash of 1772. In May of 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, which reduced the tax on tea—as a way of saving the East India Company—but again asserted Parliament’s right to tax the colonies. Townspeople in Philadelphia called anyone who imported the tea “an enemy of the country.” Tea agents resigned their posts in fear. That fall, three ships loaded with tea arrived in Boston. On the night of December 16, dozens of colonists disguised as Mohawks—warring Indians—boarded the boats and dumped chests of the tea into the harbor. To punish the city, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, which closed Boston Harbor and annulled the Massachusetts charter, effective in June of 1774.

In Virginia, James Madison Jr., twenty-three, eyed the events in Massachusetts from Montpelier, his family’s plantation in the Piedmont, east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. He’d graduated from Princeton two years before and was home tutoring his younger siblings. Far from the scene of action, he followed the news avidly and took pains to understand why the response to the tea tax was different in the northern and middle colonies than in the southern colonies. At Princeton, a Presbyterian college—a college of a dissenting faith—he’d made a study of religious liberty, and, after the dumping of the tea, he concluded that Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had resisted parliamentary authority in a way that Virginia did not because the more northern colonies had no established religion. Religious liberty, Madison came to believe, is a good in itself, because it promotes an independence of the mind, but also because it makes possible political liberty. Hearing word of the Coercive Acts, he began to think, for the first time, of war. He wrote to his closest friend, William Bradford, in Philadelphia, and asked him whether it might not be best “as soon as possible to begin our defense.”54

Meanwhile, at Mount Vernon, George Washington, who’d been elected to the Virginia legislature in 1758, had chiefly occupied himself managing his considerable tobacco estate.55 He hadn’t been much animated by the colonies’ growing resistance to parliamentary authority until the passage of the Coercive Acts. In September, fifty-six delegates from twelve of the thirteen mainland colonies met in Philadelphia, in a carpenters’ guildhall, as the First Continental Congress. Washington served as a delegate from Virginia. But if protest over the Stamp Act had temporarily united the colonies, the Coercive Acts appeared to many delegates to be merely Massachusetts’s problem. To Virginians, the delegates from Massachusetts seemed intemperate and rash, fanatical, even, especially when they suggested the possibility of an eventual independence from Britain. In October, Washington expressed relief when, after speaking to the “Boston people,” he felt confident that he could “announce it as a fact, that it is not the wish or interest of that Government, or any other upon this Continent, separately or collectively, to set up for Independency.” He was as sure “as I can be of my existence, that no such thing is desired by any thinking man in all North America.”56

From Philadelphia, James Madison’s friend William Bradford passed along fascinating tidbits of gossip about the goings-on at Congress. Bradford proved a resourceful reporter, and a better sleuth. From the librarian at the Library Company of Philadelphia—which supplied Congress with books—he’d heard that the delegates were busy reading “Vattel, Burlamaqui, Locke, and Montesquieu,” leading Bradford to reassure Madison: “We may conjecture that their measures will be wisely planned since they debate on them like philosophers.”57

Wise they may have been, but these philosophers immediately confronted a very difficult question that has dogged the Union ever since. Congress was meant to be a representative body. How would representation be calculated? Virginia delegate Patrick Henry, an irresistible orator with a blistering stare, suggested that the delegates cast a number of votes proportionate to their colonies’ number of white inhabitants. Given the absence of any accurate population figures, the delegates had little choice but to do something far simpler—to grant each colony one vote. In any case, the point of meeting was to become something more than a collection of colonies and the sum of their grievances: a new body politic. “The distinction between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders is no more,” Henry said. “I am not a Virginian, but an American.”58 A word on a long-ago map had swelled into an idea.

II.

THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS neither suffered the disunion and chaos of the Albany Congress nor undertook the deferential pleading of the Stamp Act Congress. Preparing for the worst, this new, more ambitious, and more expansive—continental—Congress urged colonists to muster their militias and stockpile weapons. It also agreed to boycott all British imports and to ban all trade with the West Indies, a severing of ties with the islands. The month the boycott was to begin, the Jamaica Assembly sent a petition to the king, with a bow and a curtsey. The Jamaicans began with an assurance that the island had no intention of joining the rebellion: “weak and feeble as this Colony is, from its very small number of white inhabitants, and its peculiar situation from the incumbrance of more than two hundred thousand slaves, it cannot be supposed that we now intend, or ever could have intended, resistance to Great Britain,” the Jamaicans explained. And yet, they went on, they did agree with the continentals’ fundamental grievance, declaring it “the first established principle of the Constitution, that the people of England have a right to partake, and do partake, of the legislation of their country.”59

Unmoved, Congress offered Jamaica halfhearted thanks: “We feel the warmest gratitude for your pathetic mediation in our behalf with the crown.” Neither the king nor Parliament proved inclined to reconsider the Coercive Acts. The tax burden against which the colonists were protesting was laughably small, and their righteousness was grating. Lord North, the prime minister, commissioned the famed essayist Samuel Johnson to write a response to the Continental Congress’s complaints. Plainly, the easiest case to make against the colonists was to charge them with hypocrisy. In Taxation No Tyranny, Johnson asked, dryly, “How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?” Johnson’s opposition to slavery was far more than rhetorical; a free Jamaican, a black man named Francis Barber, was his companion, collaborator, and heir. (“To the next insurrection of negroes in the West Indies,” Johnson declared, in a toast he offered during the war.) But Johnson’s charge of hypocrisy amounted to no more than the charges made by Philadelphia doctor Benjamin Rush the year before: “Where is the difference,” Rush wondered, “between the British Senator who attempts to enslave his fellow subjects in America, by imposing Taxes upon them contrary to Law and Justice, and the American Patriot who reduces his African Brethren to Slavery, contrary to Justice and Humanity?”60

By now, the seed planted by Benjamin Lay had borne fruit, and Quakers had formally banned slavery—excluding from membership anyone who claimed to own another human being. On April 14, 1775, one month before the Second Continental Congress was to meet in Philadelphia, two dozen men, seventeen of them Quakers, founded in that city the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. But once again, as in 1773, whatever the urgency of ending slavery, the attention of all the colonies was called away. Five days later, on April 19, 1775, blood spilled on the damp, dark grass of spring, on Lexington Green.

It began when General Thomas Gage, in charge of the British troops, seized ammunition stored outside of Boston, in nearby Charlestown and Cambridge, and sent seven hundred soldiers to do the same in Lexington and Concord. Seventy armed militiamen, or minutemen—farmers who pledged to be ready at a moment’s notice—met them in Lexington, and more in Concord. The British soldiers killed ten of them, and lost two men of their own. The rebel forces then laid siege to Boston, occupied by the British army. Loyalists stayed in the city, but Loyalists in Boston were few: twelve thousand of the city’s fifteen thousand inhabitants attempted to escape, the ragged and the dainty, the old and the young, the war’s first refugees.

John Hancock, John Adams, and Samuel Adams rode in haste to Philadelphia. The evacuation cleaved families. Boston Gazette printer Benjamin Edes carted his printing press and types to the Charles River and rowed across while, in Boston, his eighteen-year-old son was taken prisoner of war.61 Jane Franklin, sixty-three, rode out of the city in a wagon with a granddaughter, leaving a grandson behind. “I had got Pact up what I Expected to have liberty to carey out intending to seek my fourtune with hundred others not knowing whither,” she wrote to her brother, who was on his way back to America, after years in England, to join Congress.62

Shots having been fired, the debate at the Second Continental Congress, which convened that May, was far more urgent than at the First. Those who continued to hope for reconciliation with Great Britain—which described most delegates—had now to answer the aggrieved, more radical delegates from Massachusetts, who brought stories of trials and tribulations. “I sympathise most sincerely with you and the People of my native Town and Country,” Benjamin Franklin wrote to his sister. “Your Account of the Distresses attending their Removal affects me greatly.”63 In June, two months after bullets were first fired in Massachusetts, Congress voted to establish a Continental army; John Adams nominated George Washington as commander. The resolute and nearly universally admired Washington, a man of unmatched bearing, and very much a Virginian, was sent to Massachusetts to take command—his very ride meant as a symbol of the union between North and South.

All fall, Congress was occupied with taking up the work of war, raising recruits and provisioning the troops. The question of declaring independence was put off. Most colonists remained loyal to the king. If they supported resistance, it was to fight for their rights as Englishmen, not for their independence as Americans.

Their slaves, though, fought a different fight. “It is imagined our Governor has been tampering with the Slaves & that he has it in contemplation to make great Use of them in case of a civil war,” young James Madison reported from Virginia to his friend William Bradford in Philadelphia. Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, intended to offer freedom to slaves who would join the British army. “To say the truth, that is the only part in which this colony is vulnerable,” Madison admitted, “and if we should be subdued, we shall fall like Achilles by the hand of one that knows that secret.”64

But the colonists’ vulnerability to slave rebellion, that Achilles’ heel, was hardly a secret: it defined them. Madison’s own grandfather, Ambrose Madison, who’d first settled Montpelier, had been murdered by slaves in 1732, apparently poisoned to death, when he was thirty-six. In Madison’s county, slaves had been convicted of poisoning their masters again in 1737 and 1746: in the first case, the convicted man was decapitated, his head placed atop a pole outside the courthouse “to deter others from doing the Like”; in the second, a woman named Eve was burned alive.65 Their bodies were made into monuments.

No estate was without this Achilles’ heel. George Washington’s slaves had been running away at least since 1760. At least forty-seven of them fled at one time or another.66 In 1763, a twenty-three-year-old man born in Gambia became Washington’s property; Washington named him Harry and sent him to work draining a marsh known as the Great Dismal Swamp. In 1771, Harry Washington managed to escape, only to be recaptured. In November 1775, he was grooming his master’s horses in the stables at Mount Vernon when Lord Dunmore made the announcement that Madison had feared: he offered freedom to any slaves who would join His Majesty’s troops in suppressing the American rebellion.67

In Cambridge, where George Washington was assembling the Continental army, he received a report about the slaves at Mount Vernon. “There is not a man of them but would leave us if they believed they could make their escape,” Washington’s cousin reported that winter, adding, “Liberty is sweet.”68 Harry Washington bided his time, but he would soon join the five hundred men who ran from their owners and joined Dunmore’s forces, a number that included a man named Ralph, who ran away from Patrick Henry, and eight of the twenty-seven people owned by Peyton Randolph, who had served as president of the First Continental Congress.69

Edward Rutledge, a member of South Carolina’s delegation to the Continental Congress, said that Dunmore’s declaration did “more effectually work an eternal separation between Great Britain and the Colonies—than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of.”70 Not the taxes and the tea, not the shots at Lexington and Concord, not the siege of Boston; rather, it was this act, Dunmore’s offer of freedom to slaves, that tipped the scales in favor of American independence.

Not that it ever tipped them definitively. John Adams estimated that about a third of colonists were patriots, a third were Loyalists, and a third never really made a decision about independence.71 Aside from Dunmore’s proclamation of freedom to slaves, the strongest impetus for independence came from brooding and tireless Thomas Paine, who’d immigrated to Philadelphia from England in 1774. In January 1776, Paine published an anonymous pamphlet called Common Sense, forty-seven pages of brisk political argument. “As it is my design to make those that can scarcely read understand,” Paine explained, “I shall therefore avoid every literary ornament and put it in language as plain as the alphabet.” Members of Congress might have been philosophers, reading Locke and Montesquieu. But ordinary Americans read the Bible, Poor Richard’s Almanack, and Thomas Paine.

Paine wrote with fury, and he wrote with flash. “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind,” he announced. “’Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent—of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time.”

His empiricism was homegrown, his metaphors those of the kitchen and the barnyard. “There is something absurd in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island,” he wrote, turning the logic of English imperialism on its head. “We may as well assert that because a child has thrived upon milk, that it is never to have meat.”

But he was not without philosophy. Digesting Locke for everyday readers, Paine explained the idea of a state of nature. “Mankind being originally equals in the order of creation, the equality could only be destroyed by some subsequent circumstance,” he wrote, a schoolteacher to his pupils. The rule of some over others, the distinctions between rich and poor: these forms of inequality were not natural, nor were they prescribed by religion; they were the consequences of actions and customs. And the most unnatural distinction of all, he explained, is “the distinction of men into kings and subjects.”72

Paine made use, too, of Magna Carta, arguing, “The charter which secures this freedom in England, was formed, not in the senate, but in the field; and insisted upon by the people, not granted by the crown.” He urged Americans to write their own Magna Carta.73 But Magna Carta supplies no justification for outright rebellion. The best and most expedient strategy, Paine understood, was to argue not from precedent or doctrine but from nature, to insist that there exists a natural right to revolution, as natural as a child leaving its parent. “Let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the earth, unconnected with the rest, they will then represent the first peopling of any country, or of the world,” he began, as if he were telling a child a once-upon-a time story.74 They will erect a government, to secure their safety, and their liberty. And when that government ceases to secure their safety and their liberty, it stands to reason that they may depose it. They retain this right forever.

Much the same language found its way into resolutions passed by specially established colonial conventions, held so that the colonies, untethered from Britain, could establish new forms of government. “All men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity,” read the Virginia Declaration of Rights and Form of Government, drafted in May 1776 by brazen George Mason. “All power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people.” James Madison, half Mason’s age, had been elected to the convention from Orange County. He proposed a revision to Mason’s Declaration. Where Mason had written that “all men should enjoy the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion,” Madison rewrote that clause to instead guarantee that “all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise of it.” The proposed change was adopted, and Madison became the author of the first-ever constitutional guarantee of religious liberty, not as something to be tolerated, but as a fundamental right.75

Inevitably, slavery cast its long and terrible shadow over these statements of principle: slavery, in fact, had made those statements of principle possible. Mason’s original draft hadn’t included the clause about rights being acquired by men “when they enter into a state of society”; these words were added after members of the convention worried that the original would “have the effect of abolishing” slavery.76 If all men belonging to civil society are free and equal, how can slavery be possible? It must be, Virginia’s convention answered, that Africans do not belong to civil society, having never left a state of nature.

Within eighteenth-century political thought, women, too, existed outside the contract by which civil society was formed. From Massachusetts, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John, in March of 1776, wondering whether that might be remedied. “I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors,” she began, alluding to the long train of abuses of men over women. “Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands,” she told him. She spoke of tyranny: “Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could.” And she challenged him to follow the logic of the principle of representation: “If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

Her husband would have none of it. “As to your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh,” he replied. “We have been told that our Struggle has loosened the bands of Government every where. That Children and Apprentices were disobedient—that schools and Colledges were grown turbulent—that Indians slighted their Guardians and Negroes grew insolent to their Masters. . . . Depend upon it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”77 That women were left out of the nation’s founding documents, and out of its founders’ idea of civil society, considered, like slaves, to be confined to a state of nature, would trouble the political order for centuries.

AT THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS, in June, Pennsylvania delegate John Dickinson drafted the Articles of Confederation. “The Name of this Confederacy shall be ‘The United States of America,’” he wrote, possibly using that phrase for the first time. It may be that Dickinson found the phrase “the united states” in a book of treaties used by Congress; it included a treaty from 1667 that referred to a confederation of independent Dutch states as the “the united states of the Low Countries.” In Dickinson’s draft, the colonies—now states—were to form a league of friendship “for their Common Defence, the Security of their Liberties, and their mutual & general Wellfare.” The first draft brought before Congress called for each state’s contribution to the costs of war, and of the government, to be proportionate to population, and therefore called for a census to be taken every three years. It would take many revisions and a year and a half of debate before Congress could agree on a final version. That final document stripped from Dickinson’s original most of the powers his version had granted to Congress; the final Articles of Confederation are more like a peace treaty, establishing a defensive alliance among sovereign states, than a constitution, establishing a system of government. Much was makeshift. The provision for a census of all the states together, for instance, was struck in favor of an arrangement by which a common treasury was to be supplied “in proportion to the value of all land within each state,” and since, in truth, no one knew that value, what the states contributed would be left for the states to decide.78

Nevertheless, these newly united states edged toward independence. On June 7, 1776, fiery Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” A vote on the resolution was postponed, but Congress appointed a Committee of Five to draft a declaration: Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, New York delegate Robert R. Livingston, and Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman. Jefferson agreed to prepare a first draft.

The Declaration of Independence was not a declaration of war; the war had begun more than a year before. It was an act of state, meant to have force within the law of nations. The Declaration explained what the colonists were fighting for; it was an attempt to establish that the cause of the revolution was that the king had placed his people under arbitrary power, reducing them to a state of slavery: “The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.” Many readers found these words unpersuasive. In 1776, the English philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham called the theory of government that informed the Declaration of Independence “absurd and visionary.” Its self-evident truths he deemed neither self-evident nor true. He considered them, instead, “subversive of every actual or imaginable kind of Government.”79

But what Bentham found absurd and visionary represented the summation of centuries of political thought and political experimentation. “There is not an idea in it but what had been hackneyed in Congress for two years before,” Adams later wrote, jealous of the acclaim that went to Jefferson. Jefferson admitted as much, pointing out that novelty had formed no part of his assignment. Of the Declaration, he declared, “Neither aiming at originality of principles or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind.”80 But its ideas, those expressions of the American mind, were older still.

“We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable,” Jefferson began, “that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these ends, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government shall become destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, & to institute new government.” He’d borrowed from, and vastly improved upon, the Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason. Having established that a right of revolution exists if certain conditions are met, it remained to establish that those conditions obtained. The bulk of Jefferson’s draft was a list of grievances, of charges against the king, calling him to account “for imposing taxes on us without our consent,” for dissolving the colonists’ assemblies, for keeping a standing army, “for depriving us of trial by jury,” rights established as far back as Magna Carta. Then, in the longest statement in the draft, Jefferson blamed George III for African slavery, charging the king with waging “cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery,” preventing the colonies from outlawing the slave trade and, “that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us.” This passage Congress struck, unwilling to conjure this assemblage of horrors in the nation’s founding document.

The Declaration that Congress did adopt was a stunning rhetorical feat, an act of extraordinary political courage. It also marked a colossal failure of political will, in holding back the tide of opposition to slavery by ignoring it, for the sake of a union that, in the end, could not and would not last.

In July, the Declaration of Independence was read aloud from town houses and street corners. Crowds cheered. Cannons were fired. Church bells rang. Statues of the king were pulled down and melted for bullets. Weeks later, when a massive slave rebellion broke out in Jamaica, slave owners blamed the Americans for inciting it. In Pennsylvania, a wealthy merchant, passionately stirred by the spirit of the times, not only freed his slaves but vowed to spend the rest of his life tracking down those he had previously owned and sold, and their children, and buying their freedom. And in August 1776, one month after delegates to the Continental Congress determined that in the course of human events it sometimes becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the bands which have connected them with another, Harry Washington declared his own independence by running away from Mount Vernon to fight with Dunmore’s regiment, wearing a white sash stitched with the motto “Liberty to Slaves.”81

III.

DURING THE WAR, nearly one in five slaves in the United States left their homes, fleeing American slavery in search of British liberty. One American refugee renamed himself “British Freedom.” New lyrics to “Yankee Doodle,” rewritten as “The Negroes Farewell to America,” were composed in London. In the new version, fugitive slaves leave the United States “for old Englan’ where Liberty reigns / Where Negroe no beaten or loaded with chains.”82

Not many succeeded in reaching the land where liberty reigned, or even in getting behind British battle lines. Instead, they were caught and punished. One slave owner who captured a fifteen-year-old girl who was heading for Dunmore’s regiment punished her with eighty lashes and then poured hot embers into the gashes.83 However desperate and improbable a flight, it must have seemed a good bet; the shrewdest observers expected Britain to win the war, not least because the British began with 32,000 troops, disciplined and experienced, compared to Washington’s 19,000, motley and unruly. An American victory appeared an absurdity. But the British regulars, far from home, suffered from a lack of supplies, and while William Howe, commander in chief of British forces, set his sights first on New York and next on Philadelphia, he found that his victories yielded him little. Unlike European nations, the United States had no established capital city whose capture would have led to an American surrender. More importantly, time and again, Howe failed to press for a final, decisive defeat of the Americans, fearing the losses his own troops would sustain and the danger of heavy casualties when reinforcements were at such a distance.

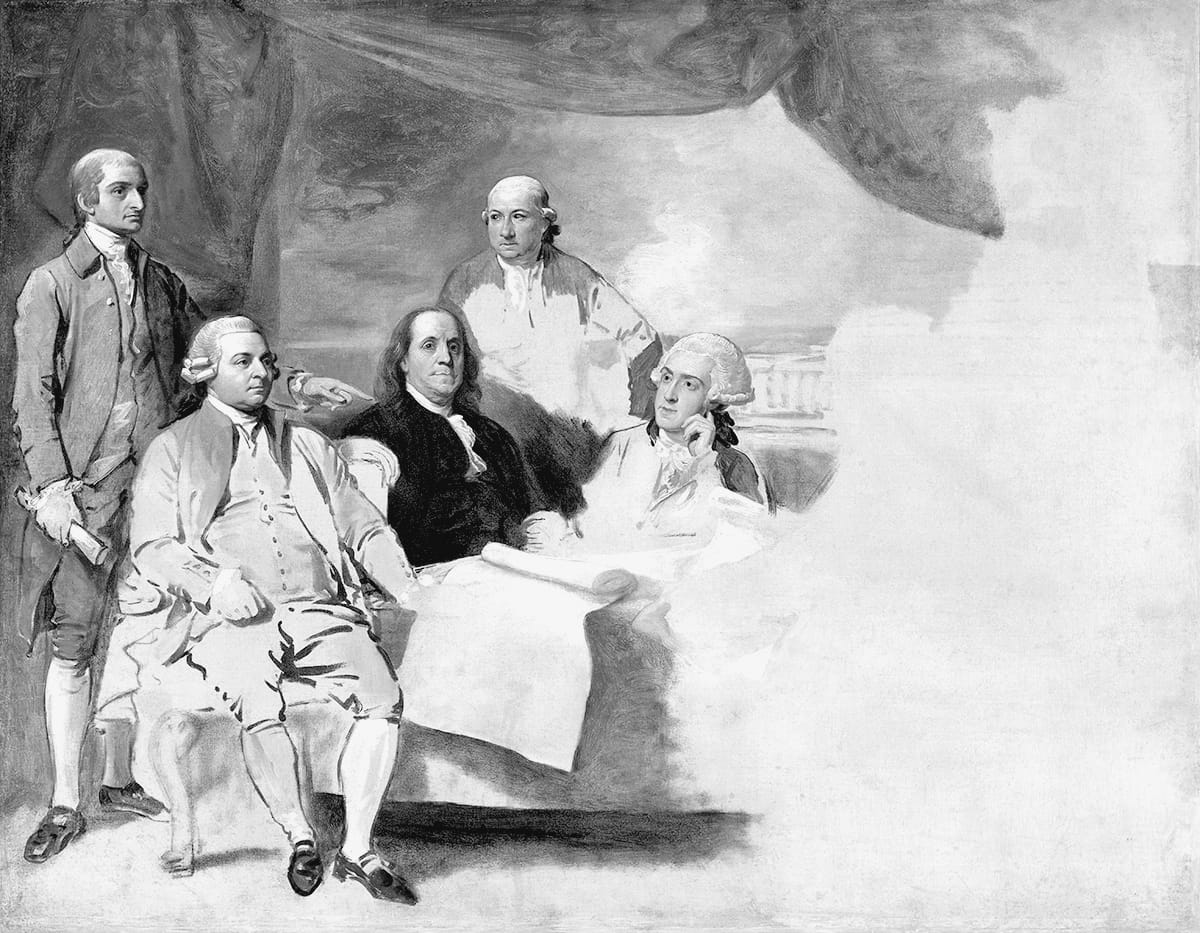

Then, too, Britain’s forces were spread thin, across the globe, waging the war on many fronts. For the British, the American Revolution formed merely one front in a much larger war, a war for empire, a world war. Like the French and Indian War, that war was chiefly fought in North America, but it spilled out elsewhere, too, to West Africa, South Asia, the Mediterranean, and the Caribbean. In 1777, Howe captured Philadelphia while, to the north, the British commander John Burgoyne suffered a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Saratoga. This American victory helped John Jay, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, serving as diplomats in France, to secure a vital treaty: in 1778, France entered the conflict as an ally of the United States, at which point Lord North, keen to protect Britain’s much richer colonies in the Caribbean from French attack, considered simply abandoning the American theater. Spain joined the French-American alliance in 1779. Germany entered the conflict by supplying paid soldiers called, by Americans, Hessians. And, partly because the Dutch had been supplying arms and ammunition to the Americans, Britain declared war on Holland in 1780. The involvement of France brought the fighting to the wealthy West Indies, where, beginning in 1778, the French captured the British colonies of Dominica, Grenada, St. Vincent, Montserrat, Tobago, St. Kitts, and Turks and Caicos. The cessation of trade between the mainland and the British Caribbean exacted another kind of toll on Britain’s profitable sugar colonies: Africans starved to death. On Antigua alone, a fifth of the slave population died during the war.84

To Americans, the Revolutionary War was not a world war but a civil war, between those who favored independence and the many who did not. John Adams, offhand, guessed that one in three colonists remained loyal to the Crown and another third hadn’t quite decided, but Adams’s guess did not begin to include the still greater numbers of Loyalists whom the British counted among their allies: the entire population of American slaves and nearly all Native American peoples. One reason the British continually failed to press their advantage was that they kept trying to change the field of fighting to a part of the colonies where they expected to find more Loyalist support, not only among the merchants and lawyers and farmers who remained loyal to the Crown but among their African and Indian allies. The battle, Howe’s successor, Henry Clinton, believed, was “to gain the hearts & subdue the minds of America.”85 That strategy failed. And when that strategy failed, Britain didn’t so much lose America as abandon it.

At first, the Crown courted compliance. In 1778, the king sent commissioners authorized to offer to repeal all acts of Parliament that had been opposed by the colonies since 1763, but when Congress demanded that the king recognize American independence, the commissioners refused. At this point, although Clinton held New York City and fighting continued to the west, the theater of war moved to the South: British ministers decided to make a priority of saving the wealthy sugar islands, to give up on the northern and middle mainland colonies, and to try to keep the southern colonies in order to restore the supply of food to the West Indies. Clinton captured Savannah, Georgia, in December 1778 and set his sights on Charleston, South Carolina, the largest city in the South. In Congress, this led to a debate about arming slaves. In May 1779, Congress proposed to enlist three thousand slaves in South Carolina and Georgia and to pay them with their freedom. “Your Negro Battallion will never do,” warned John Adams. “S. Carolina would run out of their Wits at the least Hint of such a Measure.”86 He was entirely correct. The South Carolina legislature rejected the proposal, declaring, “We are much disgusted.”87 Clinton captured Charleston in May of 1780.

In 1781, in hopes of taking the Chesapeake, the British general Lord Cornwallis fortified Yorktown, Virginia, as a naval base. His troops were soon besieged and bombarded by a combination of French and American forces. The French were led by the dazzling Marquis de Lafayette, whose service to the Continental army and impassioned advocacy of the American cause had included lobbying for French support. Cornwallis was vulnerable because British naval forces were occupied in the Caribbean. He surrendered on October 19, not realizing that British forces were that very day sailing from New York to aid him. Cornwallis’s defeat at Yorktown ended the fighting in North America, but it didn’t end the war. The real end, for Great Britain, came in 1782, in the West Indies, at the Battle of the Saintes, when the British defeated a French and Spanish invasion of Jamaica, an outcome that testified not to the empire’s weaknesses but to its priorities. Britain kept the Caribbean but gave up America.

Not surprisingly, the terms of the peace proved as messy and sprawling as the war. Loyalists confronted the same decision as the empire itself: whether to give up on America. “To go or not to—is that the question?” one bit of Shakespearean doggerel went. “Whether ’tis best to trust the inclement sky . . . or stay among the Rebels! / And, by our stay rouse up their keenest rage.” Most, not near so indecisive as Hamlet, left if they could: 75,000, about one in every forty people in the United States, evacuated with the British. They went to Britain and Canada, to the West Indies and India: they helped build the British Empire. “No News here but that of Evacuation,” one patriot wrote from New York. “Some look smiling, others melancholy, a third Class mad.” None were more desperate to escape the United States than the 15,000–20,000 ex-slaves who were part of that exodus, the largest emancipation in American history before Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.88 In July of 1783, Harry Washington, who’d left Mount Vernon years before to join Dunmore’s regiment, managed to reach New York City, where he boarded the British ship L’Abondance, bound for Nova Scotia. A clerk noted his departure in a ledger called the “Book of Negroes,” listing the 2,775 runaway black men, women, and children who evacuated from the city with the British that summer: “Harry Washington, 43, fine fellow. Formerly the property of General Washington; left him 7 years ago.”89

When Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, 60,000 Loyalists raced to get behind British lines. Knowing their property would be seized, if it hadn’t been already—or that they themselves would be seized, as someone else’s property—they chose to leave the United States for Britain or for other parts of its empire. They headed to New York, Savannah, or Charleston, cities still held by the British, and from which they would soon be disembarking. Out of 9,127 Loyalists who sailed from Charleston, 5,327 were fugitive slaves. In Virginia, the 2,000 black soldiers under Cornwallis’s command who had survived the siege, described as “herds of Negroes,” trudged through swamps and forests in hopes of reaching a British warship that Washington, under the terms of the surrender, had agreed to allow to sail to New York. They suffered from exhaustion; they suffered from hunger; they suffered from disease. Of thirty people who escaped Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, fifteen died of smallpox before reaching Cornwallis. Other fugitive slaves fled to the French. “We gained a veritable harvest of domestics,” wrote one surprised French officer. Armed slave patrols pursued the fugitives, capturing hundreds of Cornwallis’s soldiers and their families, including two people owned by Washington and five owned by Jefferson. In the race to reach British lines, pregnant women ran, too, in hopes that their newborns would earn their freedom papers in the form of a “BB” certificate: “Born Free Behind British Lines.”90

Reaching New York or Charleston or Savannah was only the beginning of the journey. In New York, Boston King, a runaway from South Carolina, heard a rumor that all the slaves in the city, some two thousand, “were to be delivered up to their masters,” and he was haunted by fear of American slave owners marching through the city, “seizing upon their slaves in the streets, or even dragging them out of their beds.” King, a carpenter, wrote in his memoirs that blacks in the city were too frightened even to sleep. A Hessian officer reported that as many as five thousand slave owners entered the city to recapture their slaves. George Washington had in fact ordered the keeping of the “Book of Negroes” so that owners might later seek compensation for slaves carried off in British ships. In Charleston, soldiers patrolled the wharves to hold back the hundreds of people desperately seeking to realize what would be, for most of them, their last chance at securing the blessings of liberty for themselves and their posterity. Despite the patrols, dozens of people leapt off the docks and swam out to the last longboats heading to the British warships, including the aptly named Free Briton. The swimmers grabbed the rails of the crowded boats and tried to climb aboard. When they would not let go, the British soldiers on the boats tried to hack off their fingers.91

The Revolution was at its most radical in the challenge it presented to the institution of slavery and at its most conservative in its failure to meet that challenge. Still, the institution had begun to break, like a pane of glass streaked with cracks but not yet shattered. In January 1783, when Lafayette heard that the commissioners in Paris were near to arriving at a peace treaty, he wrote to Washington to congratulate him and to propose that together they finish work the Revolution had begun. “Let us unite in purchasing a small estate, where we may try the experiment to free the negroes,” he suggested. “Such an example as yours might render it a general practice; and if we succeed in America,” they could bring the experiment to the West Indies. “I should be happy to join you in so laudable a work,” Washington wrote back, saying that he wished to meet to discuss the details.92

No thinking person was unaffected by the challenge the struggle for liberty posed to the institution of slavery, America’s Achilles’ heel. In Philadelphia in 1783, James Madison, leaving Congress, was packing up, preparing to return to Montpelier. He wasn’t sure what to do about Billey, a twenty-three-year-old man that he’d brought with him from Virginia when he’d first come to serve in Congress. Billey had been Madison’s property since his birth in 1759, when Madison was eight years old. In 1777, the Pennsylvania legislature passed the first abolition law in the Western world, decreeing that any child born to an enslaved woman after March 1, 1780, would be free after twenty-eight years of slavery, and banning the sale of slaves. New York’s John Jay declared that to oppose emancipation would be to find of America that “her prayers to Heaven for liberty will be impious.”93 In 1782, the Virginia legislature passed a law that allowed slave owners to free their slaves: one Virginia Quaker said, upon manumitting his slaves, that he had been “fully persuaded that freedom is the natural Right of all mankind & that it is my duty to do unto others as I would desire to be done by in the Like Situation.”94 Not many followed his lead. In 1782, Madison had bought a cache of books in Philadelphia, including a copy of Hobbes’s Leviathan, even though short of cash and complaining that he would soon be “under the necessity of selling a negro,” meaning Billey.95

The terrible irony of the man who would draft the Constitution selling a man to buy philosophy was prevented by the terms of Pennsylvania’s 1780 abolition law. Madison could not, in fact, sell Billey in Philadelphia. And in 1783, as he prepared to leave Philadelphia for Virginia, it was by no means certain, under Pennsylvania law, that he had any legal right to force Billey to go with him, either. “I have judged it most prudent not to force Billey back to Virginia even if it could be done,” Madison reported to his father. “I am persuaded his mind is too thoroughly tainted to be a fit companion for fellow slaves in Virginia.” That is, Billey, having spent three and a half years serving Madison in Philadelphia, a city where many black people were free, would be a problem on a plantation: he would incite rebellion. Trade in slaves was illegal in Pennsylvania. Madison might have tried to smuggle Billey out of the state, to sell him farther south, or into the Caribbean, but, he told his father, he was unwilling to “think of punishing him by transportation merely for coveting that liberty for which we have paid the price of so much blood, and have proclaimed so often to be the right, and worthy pursuit, of every human being.” In the end, Madison decided to sell him, not as a slave but as an indentured servant, with a seven-year term. Billey renamed himself William Gardener, served out his seven-year term, became a free man, worked as merchant’s agent, and raised a family with a wife who, when Jefferson was in Philadelphia, washed Jefferson’s clothes.96