Four

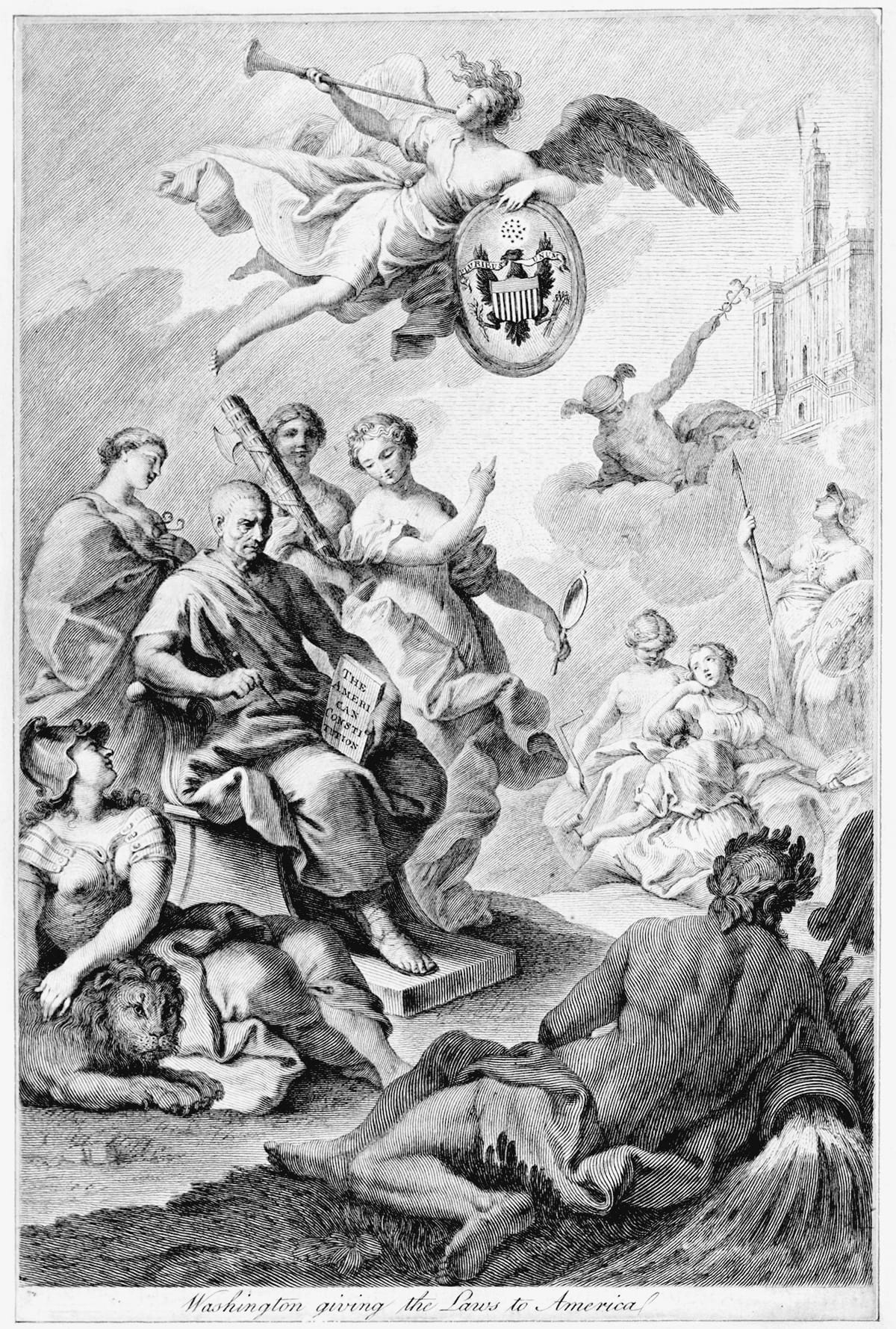

THE CONSTITUTION OF A NATION

JAMES MADISON, THIRTY-SIX, BOOKISH, AND WISE, reached Philadelphia on May 3, 1787, eleven days before the constitutional convention was meant to begin. He settled into his old rooms at Mrs. House’s hotel, a boardinghouse at Fifth and Market Streets, where he’d stayed during meetings of the Continental Congress. To prepare for the convention, he reviewed his notes on the construction of republics. George Washington arrived on May 13, on the eve of the convention, not nearly as quietly, greeted by crowds, the pealing of church bells, a regiment of cavalry, and a thirteen-gun salute. When Washington reached Mrs. House’s, where he’d planned to stay, the wealthy Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris met him there and insisted that Washington stay at his lavish mansion, a few blocks away. The next morning, Washington and Madison walked together to the Pennsylvania State House through a tender mist.1

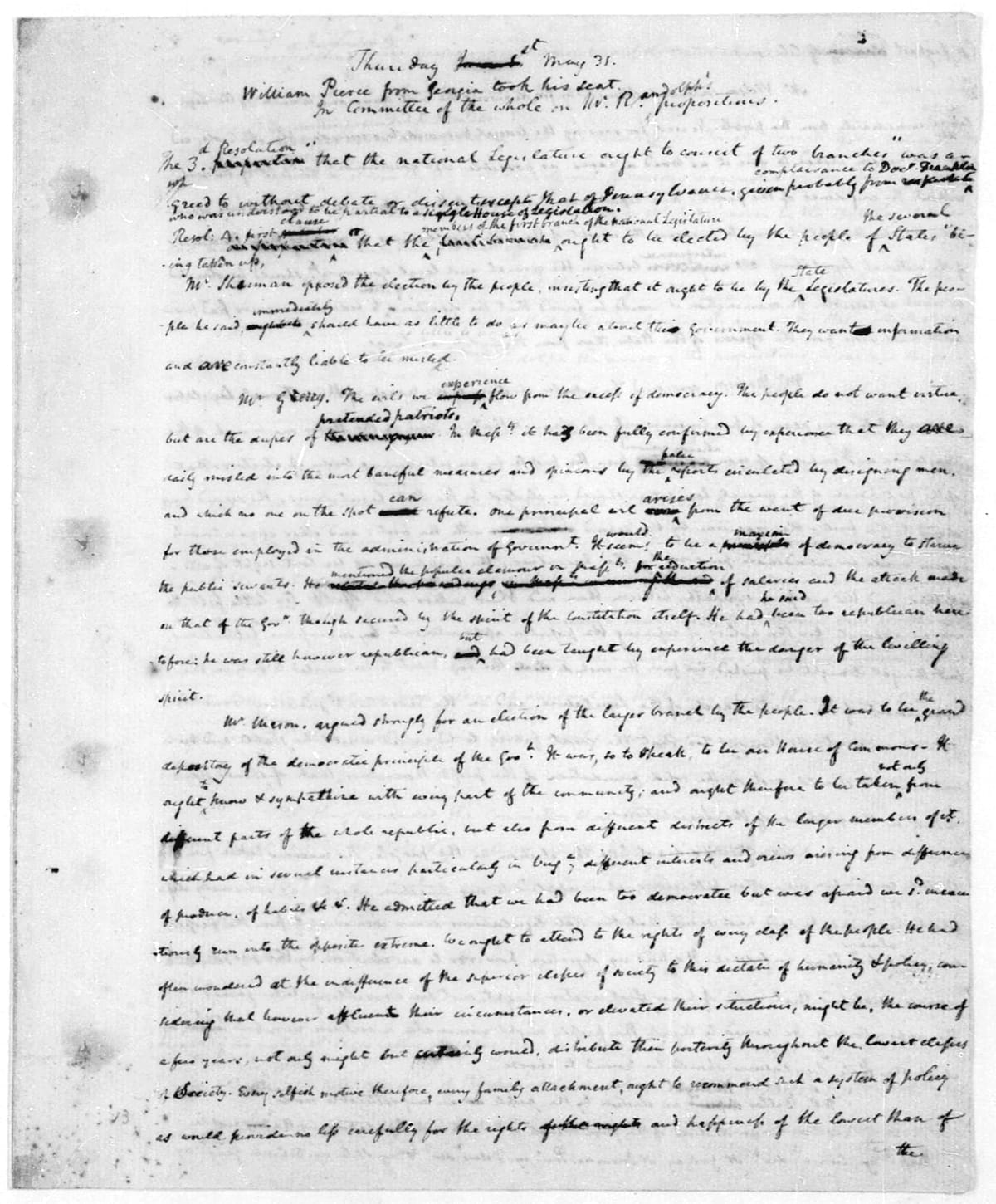

Very few of the delegates had arrived. “There is less punctuality in the outset than was to be wished,” Madison wrote to Jefferson, in Paris, on May 15, brooding.2 Delay or no delay, from the start of the proceedings, Madison took careful notes, certain “of the value of such a contribution to the fund of materials for the History of a Constitution on which would be staked the happiness of a young people.” Past an arched doorway, in the Assembly Room of the State House, its tall windows flooding the room with light, the convention met from May 14 to September 17, from a season of planting to a season of harvest. Madison didn’t miss a single day, “nor more than a casual fraction of an hour in any day,” he explained, “so that I could not have lost a single speech, unless a very short one.”3

Madison spoke softly and haltingly, the very opposite of the way he wrote. He was making a record for himself, and he was also writing down what happened in Philadelphia that summer for Jefferson. Ever since Jefferson left the country, in 1784, Madison had been taking notes of congressional deliberations for him, too. But Madison understood that, above all, he was making a record for posterity, a record of how a constitution had come to be written.

To constitute something is to make it. A body is constituted of its parts, a nation of its laws. “The constitution of man is the work of nature,” Rousseau wrote in 1762, “that of the state the work of art.”4 By the eighteenth century, a constitution had come to mean “that Assemblage of Laws, Institutions and Customs, derived from certain fix’d Principles of Reason . . . according to which the Community hath agreed to be govern’d.”5 Englishmen boasted that “England is now the only monarchy in the world that can properly be said to have a constitution.”6 But England’s constitution is unwritten; instead of a single, written document, England’s constitution is the sum of its laws, customs, and precedents. In a debate with the conservative Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine suggested that England’s constitution did not, in fact, exist. “Can, then, Mr. Burke produce the English Constitution?” Paine asked. “If he cannot, we may fairly conclude that though it has been so much talked about, no such thing as a constitution exists, or ever did exist.”7 In America’s book of genesis, the constitution would be written, printed, and preserved.

Centuries of speculation about a state of nature—a time before government—came to an end. It was no longer necessary to imagine how a people might erect a government: this could be witnessed. “We have no occasion to roam for information into the obscure field of antiquity, nor hazard ourselves upon conjecture,” Paine wrote. “We are brought at once to the point of seeing government begin, as if we had lived in the beginning of time.”8 It was with this in mind that Madison proved so careful a historian. It was as if he were living at the beginning of time.

I.

THE CONSTITUTION OF the United States was not the first written constitution in the history of the world. The world’s first written, popularly ratified constitutions were drafted by the American states, beginning in 1776. Having dismantled their own governments, they took seriously—literally—the idea that they needed to create them anew, as if they had been returned to a state of nature.

Three states had adopted written constitutions even before Congress declared independence from England, because they found themselves otherwise without a government. “We conceive ourselves reduced to the necessity of establishing A FORM OF GOVERNMENT,” a Constitutional Congress convened in New Hampshire declared in January 1776, after the Loyalist governor of New Hampshire fled the state, along with most members of his council.9 Eleven of the thirteen states devised constitutions in 1776 or 1777. The work of writing these constitutions, Jefferson noted in 1776, was “the whole object of the present controversy.”10

Most state constitutions were drafted by state legislatures; others were written by men elected as delegates to special conventions. In the spring of 1775, the irascible John Adams had urged Congress “to recommend to the People of every Colony to call such Conventions immediately and set up Governments of their own, under their own Authority; for the People were the Source of all Authority and the Original of all Power.” New Hampshire had been the first to act. It was the first state to submit its constitution to the people for ratification, a process whose outcome was far from inevitable. In 1778, when the Massachusetts legislature drafted a constitution and presented it to the people for ratification, the people rejected it, and called for a special convention, which was held in Cambridge in 1779; Adams, one of its delegates, was the chief author of a new constitution that the people of Massachusetts ratified in 1780. That this act—the people voting on the very form of government—represented an extraordinary break with the past was not lost on Adams, who wrote, “How few of the human race have ever enjoyed an opportunity of making an election of government, more than of air, soil, or climate, for themselves or their children!”11

Each of the states was a laboratory, each new constitution another political experiment. Many state constitutions, like those of Virginia and Pennsylvania, included a Declaration of Rights. Pennsylvania’s, written in September 1776, began by echoing the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, establishing “That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and inalienable rights, amongst which are, the enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” Massachusetts’s constitution insisted on a right to revolution, decreeing that when the government fails the people, “the people have a right to alter the government, and to take measures necessary for their safety, prosperity and happiness.”12

For all the veneration of the “people,” the word “democracy” retained an unequivocally negative connotation. Eighteenth-century Americans borrowed from Aristotle the idea that there are three forms of government: a monarchy, an aristocracy, and a polity; governments by the one, the few, and the many. Each becomes corrupt when the government seeks to advance its own interests rather than the common good. A corrupt monarchy is a tyranny, a corrupt aristocracy an oligarchy, and a corrupt polity a democracy. The way to avoid corruption is to properly mix the three forms so that corruption in any one would be restrained, or checked, by the others.

Between a government too monarchical and a government too democratic, Massachusetts lawyer and later member of Congress Fisher Ames would have rather had the former. “Monarchy is like a merchantman, which sails well, but will sometimes strike on a rock, and go to the bottom,” Ames wrote in 1783, “whilst a republic is a raft, which would never sink, but then your feet are always in the water.”13

Unlike the harrumphing Ames, many of the people who were drafting state constitutions apparently preferred to err on the side of democracy. In framing new governments, several states lowered property qualifications for voting. Under the terms of Pennsylvania’s new constitution, any man who had lived in the state for a year and paid taxes—any taxes—could vote: where earlier two-thirds of white men could vote, 90 percent now could. Yet many men of means found this development alarming, believing that poor men, like women, lacked the capacity to make good political decisions because, dependent on others, their will was not their own. Massachusetts’s constitution included property qualifications both for office seekers and for voters. As Adams explained, “Such is the Frailty of the human Heart, that very few Men, who have no Property, have any Judgment of their own.”14

Most states arranged a government of three branches, with a governor as executive, a superior court as judicial, and a Senate and House of Representatives as legislative. But some states, attempting to correct for colonial arrangements, in which a royally appointed governor and his appointed council wielded the preponderance of power over a weak elected assembly, granted the greatest weight to lower houses of the legislature rather than to upper houses or to an executive. Pennsylvania’s constitution, like its Quakers, was the most radical, and, in the eyes of many observers, alarmingly democratic. It called for annual elections, no governor, and a unicameral legislature whose members served limited terms. Any proposed law had to be printed and distributed to the people, who would have a year to consider it before the legislature voted.15

The states’ constitutions were political experiments in more ways, too. The Declaration of Rights in Vermont’s 1777 constitution specifically banned slavery: men might be indented as servants till the age of twenty-one, or women till the age of eighteen, but no one past that age could be held in bondage. (This provision would have made Vermont the first state to abolish slavery, except that in 1777 Vermont was not a state but an independent republic; it would not join the United States until 1791.)

In 1781, Bett, a slave in Massachusetts whose husband had fought and died in the war, filed a suit in which she argued that the state’s new constitution had abolished slavery. Bett’s owner, John Ashley, was a local judge. She’d heard him talking about natural rights with twenty-six-year-old Theodore Sedgwick, one of his law clerks. When Ashley’s wife tried to strike Bett’s sister with a kitchen shovel, Bett blocked the blow and was badly burned. Fleeing, she went to Sedgwick and decided, with his help, to sue for her freedom. “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing, and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness,” Adams had written, in Article I of the Massachusetts Constitution’s Declaration of Rights. Citing Adams, Bett won her case and her liberty and gave herself a new name: Elizabeth Freeman.16

Two years later, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court formally ruled that slavery was inconsistent with the state’s constitution, adding, “Is not a law of nature that all men are equal and free? Is not the laws of nature the laws of God? Is not the law of God then against slavery?” The next year, Pennsylvania’s 1775 Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage renamed itself the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and a judge in Vermont ruled in favor of a runaway slave whose master had produced a bill of sale proving his ownership: the judge said in order to retain his property in the form of another man he’d have to provide a bill of sale from “God Almighty.”17

Inevitably, some state constitutions worked better than others. What clearly didn’t work well were the Articles of Confederation, which had been hastily drawn up by the Continental Congress for the purpose of waging war against Britain, and even this they did not do well (regiments went unfed, soldiers unpaid, veterans unpensioned). Drafted in 1777, the Articles weren’t ratified by the states until 1781—the delay was the result of the states’ competing claims to western land—and even after the Articles were adopted, those claims remained largely unresolved. Efforts to revise the Articles proved fruitless, even though the Continental Congress had no standing to resolve disputes between states nor any authority to set standards or to regulate trade. The new nation was riddled, as a result, with thirteen different currencies and thirteen separate navies.

Most urgently, Congress lacked the authority to raise money, which it needed both to make good on its debts and to pay for troops in the Northwest Territory, a swath west of the Alleghenies, north of the Ohio River, and east of the Mississippi that the federal government had acquired from the states. The 1783 Treaty of Paris had required that the states repay their debts, and when the states defaulted on those debts, Great Britain threatened to default on a commitment, also made under the terms of the peace, to surrender its northwestern forts—Oswego, Niagara, and Detroit—to the United States.

Even if Congress had fully possessed the power to tax, how to calculate the tax burden of each state remained unsettled. Should each state pay in proportion to the size of its population or in proportion to its property? In much of the country, one kind of property took the form of people. For purposes of taxation, then, would slaves count as people or as property? In 1777, Pennsylvania’s Samuel Chase had argued that only white inhabitants should count as people because, legally, blacks were no more people “than cattle.” This point seemed so essential to South Carolina’s Thomas Lynch that he had threatened that “if it is debated, whether their slaves are their property, there is an end of the confederation,” whereupon Benjamin Franklin made the wry observation that there was one plain way to tell the difference between people and property: “sheep will never make any insurrections.”18

In 1781 and again in 1783, Congress tried to revise the Articles so as to grant itself authority to collect taxes on imports. This led to a return to the original debate about how to calculate each state’s tax burden: by the number of inhabitants or by the value of land. The value of land was difficult to calculate—acreage alone is a poor guide, since a field is worth more than a swamp—and, as Adam Smith had argued in The Wealth of Nations, “the most decisive mark of the prosperity of any country is the increase of the number of its inhabitants.” Population seemed both easier to calculate and a more sensible measure, for purposes not only of taxation but also of representation. This led to a compromise, involving a fraction. A committee on revenue proposed that “two blacks be rated as equal to one freeman.” Other proposals followed, until “Mr. Madison said that in order to give a proof of the sincerity of his professions of liberality, he would propose that Slaves should be rated as 5 to 3.”

It was very nearly arbitrary, this mathematical formula that would determine the course of American elections for seven decades. At the time, it was also moot: it was never implemented because the state legislatures refused to ratify any revenue-raising amendments.19 But the proposed ratio—three to five—was not forgotten.

The confederation limped along, weak and hobbled. France and Holland pressed for payment of debts—in real money, not the paper promises on which the Republic floated. “Not worth a continental,” a phrase used to describe the paper currency printed by Congress, entered the lexicon. Congress was unable to pay its creditors and, by 1786, the continental government was nearly bankrupt. The states, too, were in distress; they could levy taxes, but they couldn’t reliably collect them. Massachusetts had levied taxes to retire the state’s war debt; farmers who failed to pay could have their property seized and auctioned. Many of those farmers had fought in the war, and, beginning in August 1786, they decided to fight again: well over a thousand armed farmers in western Massachusetts, angry and alienated and led by a veteran named Daniel Shays, protested the government, blockading courthouses and seizing a federal armory.20

It seemed as if the infant nation might descend into civil war, beginning an unending cycle of revolution. “I wish our Poor Distracted State would atend to the many good Lessons” of history, Jane Franklin wrote to her brother, and not “keep always in a Flame.”21 Madison feared the rebellion would spread all the way to Virginia. Washington began to wonder whether the nation needed a king after all, writing to Madison, “We are fast verging to anarchy and confusion!” As Madison reported to Jefferson, Shays’s Rebellion had “tainted the faith” of even the most committed republicans.22

A last-ditch effort to restore order by revising the Articles of Confederation was scheduled to begin on September 11, 1786, in Annapolis, at a special convention of delegates that included Madison, who had probably been behind the resolution to convene the meeting. To prepare, he threw himself into his reading of political history. He’d been assembling a library. In 1785, Jefferson shipped him crates of books from Paris. “Since I have been at home I have had leisure to review the literary cargo for which I am so much indebted to your friendship,” he wrote to Jefferson in March 1786, reporting that Virginia had so much snow that winter that the tops of the Blue Ridge Mountains were still white. While the snow melted that spring, Madison composed a long essay called “Ancient & Modern Confederacies,” an assessment of all the confederated governments he could discover in his reading: their structure, their strengths, and, above all, their weaknesses.23

It had been an unusually wet spring. Madison left Virginia in summer and wended through fields of sodden crops of wheat and rye. He rode all the way to New York on business before turning around to head back down to Maryland, still mulling over his reading, and giving Jefferson still more instructions for books he’d like to add to his library. “If you meet with ‘Graecorum Respublicae ab Ubbone Emmio descriptae,’ Lugd. Batavorum, 1632, pray get it for me,” he pressed him.24

A road-weary Madison arrived in Annapolis in September vastly discouraged. So frayed was the spirit of union and so weak was the federal government that delegates from only five of the thirteen states turned up for the convention. They met at George Mann’s tavern, a six-gabled brick hotel. Madison stabled his horse in Mann’s barn. Without anything close to a quorum, twelve men from five states agreed to a resolution drafted by Alexander Hamilton of New York that delegates—ideally from all thirteen states—would gather in Philadelphia the next year “to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.”25

If more delegates had turned up for the Annapolis Convention, they’d most likely have proposed a single amendment to the Articles, granting Congress the authority to raise revenue. The bad turnout, ironically, opened the possibility for more sweeping action. Still, when the resolution reached Congress, which met, then, in New York, Congress failed for weeks to consider it. Arguably, it was only the course of events in Massachusetts that spurred Congress to act. In January 1787, the governor of Massachusetts sent a three-thousand-man militia across the state in an attempt to suppress Shays’s Rebellion and regain the federal armory (all of this without any authority from the federal government). The state instituted martial law. In New York, Congress finally acted, approving of the proposed Philadelphia convention “for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.”26 No one said anything about drafting a constitution.

After Annapolis, Madison went home to Virginia and resumed his course of study. In April of 1787, he drafted an essay called “Vices of the Political System of the United States.” It took the form of a list of eleven deficiencies, beginning with “1. Failure of the States to comply with the Constitutional requisitions. . . . 2. Encroachments by the States on the federal authority. . . . 3. Violations of the law of nations and of treaties.” And it closed with a list of causes for these vices, which he located primarily “in the people themselves.” By this last he meant the danger that a majority posed to a minority: “In republican Government the majority however composed, ultimately give the law. Whenever therefore an apparent interest or common passion unites a majority what is to restrain them from unjust violations of the rights and interests of the minority, or of individuals?”27 What force restrains good men from doing bad things? Honesty, character, religion—these, history demonstrated, were not to be relied upon. No, the only force that could restrain the tyranny of the people was the force of a well-constructed constitution. It would have to be as finely wrought as an iron gate.

II.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, who was not done with his usefulness, spent the early days of May 1787 waiting for the laggard delegates to arrive and attending to his correspondence. His sister Jane wrote from Boston that she’d been reading about him. “I wanted to tell you how much Pleasure I Injoy in the constant and lively mention made of you in the News papers,” she wrote, full of pride. Franklin was eighty-one years old; Jane was seventy-four. The news of his flurry of activity, she told him, winking, “makes you Apear to me Like a young man of Twenty-five.”28

Franklin was the oldest of the seventy-five men who had been elected to represent twelve states at the convention. (Rhode Island, unwilling to grant the necessity of the meeting, refused to send a delegation.) Half of the delegates were lawyers. Nineteen delegates owned slaves. Only fifty-five showed up, and, since they came and went, there were usually only about thirty men on hand on any given day. When, on May 14, the day the convention was to begin, hardly any of the delegates had arrived, Madison blamed the weather.

Aside from Franklin and Madison, two more members of the Pennsylvania delegation, Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson, were already in town, and so were two more members of the Virginia delegation: George Washington and Edmund Randolph. These six men met on the night of May 16 at Franklin’s newly enlarged house, its growth a measure of his own rise. As he explained to his sister, he’d built an addition and installed a door in his bedroom by which he could enter directly into his library, even in slippers and robe. “When I look at these Buildings, my dear Sister, and compare them with that in which our good Parents educated us, the Difference strikes me with Wonder,” he wrote to her, remembering the tiny wooden house on the crooked street of Boston where they’d been born, in a smaller America.29

That night, by the light of candles in Franklin’s dining room, the six early-comers to the convention agreed that, instead of merely revising the Articles, which were little more than a treaty of alliance among sovereign states, the convention ought to devise a national government. The next day, Madison set to work drafting what became known as the Virginia Plan. Franklin returned to his correspondence. “We are all well, and join in Love to you and yours,” he wrote to his sister.30 He pondered the state of the Union. His sister had one piece of advice. “I hope with the Asistance of such a Nmber of wise men as you are connected with in the Convention you will Gloriously Accomplish, and put a Stop to the nesesity of Dragooning, & Haltering, they are odious means,” she wrote, urging her brother to support an end to the draft and capital punishment. “I had Rather hear of the Swords being beat into Plow-shares, & the Halters used for Cart Roops, if by that means we may be brought to live Peaceably with won a nother.” Franklin’s sister, like so many Americans, had suffered gravely during the war. She’d lost her home. One of her sons had died of wounds suffered during the Battle of Bunker Hill; another had gone mad. She’d had enough of guns and violence. Franklin tucked her letter away and governed his tongue.31

The convention began its work eleven days late, on May 25, when at last a quorum of twenty-nine delegates had arrived. Washington, almost as striking at fifty-five as he’d been as a young man, was unanimously elected president. (His beauty was marred only by his terrible teeth, which had rotted and been replaced by dentures made from ivory and from nine teeth pulled from the mouths of his slaves.)32 Deeply and nearly universally admired, Washington represented to many Americans all that was noblest in a republic. Nothing better testified to his civic virtue than his resignation of his command at the end of the war: instead of seizing power, he had given it away.33 His role as president of the constitutional convention was mostly ceremonial, but, as with so many ceremonial roles, it was an essential and even a stirring performance.

The deliberations began in earnest on May 29, when Edmund Randolph offered a polite expression of gratitude to the framers of the Articles of Confederation, who could hardly be faulted for that document’s deficiencies, given that they had “done all that patriots could do, in the then infancy of the science, of constitutions, & of confederacies.” Randolph was a formidable lawyer whose Loyalist father had fled Virginia in 1775 and whose uncle Peyton’s slaves had joined Lord Dunmore’s regiment. He knew mayhem. He said he considered “the prospect of anarchy from the laxity of government everywhere,” and offered a series of resolutions about the means available to the convention for avoiding chaos.34

The immediate problem the delegates were charged with addressing—that chaos—was Congress’s debt, its lack of cash, and its inability to raise taxes or to suppress popular revolt or to resolve conflicts between the states. But, like many other delegates, Randolph believed that the work of the convention was to counter the tendencies of the state constitutions. “Our chief danger arises from the democratic parts of our constitutions,” he said. Massachusetts firebrand Elbridge Gerry agreed that the states suffered from an “excess of democracy.” Randolph believed that the point of the convention was “to provide a cure for the evils under which the United States labored; that in tracing these evils to their origin every man had found it in the turbulence and follies of democracy: that some check therefore was to be sought for against this tendency of our Governments.”35

Those delegates who opposed establishing a national government, and who thought they’d come to Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation, could not appeal to the public, which might well have been severely alarmed by word of the goings-on in Independence Hall had they heard so much as a whisper. But the delegates had pledged to keep their deliberations secret—for a term of fifty years—a pledge that worked in favor of men like Madison. And, within the hall, it allowed for a full and frank airing of views.

The Constitution drafted in Philadelphia acted as a check on the Revolution, a halt to its radicalism; if the Revolution had tilted the balance between government and liberty toward liberty, the Constitution shifted it toward government. But in very many ways the Constitution also realized the promise of the Revolution, and particularly the promise of representation. In devising the new national government, the delegates adamantly rejected a proposal that the state legislators, rather than the people, elect members of Congress. “Under the existing Confederacy, Congress represent the States not the people of the States,” George Mason said, “their acts operate on the States not on the individuals. The case will be changed in the new plan of Government. The people will be represented; they ought therefore to choose the Representatives.”36

However much delegates at the convention might have railed at the excess of democracy in the state constitutions and regretted the lowering of property qualifications for voting in the states, they did not institute those requirements in the federal constitution. Franklin argued that, since poor men of no estate whatsoever had fought in the war, there could be no sound reason why they should not vote in the new government. “Who are to be the electors of the federal representatives?” Madison asked. “Not the rich, more than the poor; not the learned, more than the ignorant; not the haughty heirs of distinguished names, more than the humble sons of obscure and unpropitious fortune. The electors are to be the great body of the People of the United States.” This was a matter as much of politics as of principle. Connecticut delegate Oliver Ellsworth put it plainly: “The people will not readily subscribe to the Natl. Constitution, if it should subject them to be disfranchised.” Voting requirements were left to the states.

Nor did the Constitution institute property requirements for running for federal office. “Who are to be the objects of popular choice?” Madison asked. “Every citizen whose merit may recommend him to the esteem and confidence of his country.” What could be more revolutionary than these words? “No qualification of wealth, of birth, of religious faith, or of civil profession is permitted to fetter the judgment or disappoint the inclination of the people,” Madison insisted.37

In this same revolutionary spirit, the Constitution required congressmen to be paid, so that the office would not be limited to wealthy men. It required only a short residency for immigrants before they, too, became eligible to run for office. Delegates who argued for greater restriction faced immigrants like Hamilton, born in the West Indies, and James Wilson, born in Scotland, who wondered at the prospect of “his being incapacitated from holding a place under the very Constitution which he had shared in the trust of making.”

But if these matters were resolved with relative ease, others proved far more difficult. The convention found itself facing a nearly unbreachable divide. How was fairly apportioned representation in Congress to be achieved in a national government composed of states of such different sizes? One proposal involved redrawing the map of the United States. “Lay the map of the confederation on the table,” a New Jersey delegate suggested, and redraw it so that “all the existing boundaries be erased, and that a new partition of the whole be made into 13 equal parts.”38 But, as Madison pointed out, the problem wasn’t only the size of the states. It was the nature of their population. “The States were divided into different interests not by their difference of size,” he explained, “. . . but principally from the effects of their having or not having slaves.”39

The problem of property in the form of people had become an even bigger problem than it had been before the Revolution. The years following the end of the war had witnessed the largest importation of African slaves to the Americas in history—a million people over a single decade. The slave population of the United States, 500,000 in 1776, had soared to 700,000 by 1787. After the Treaty of Paris, when Britain recognized the independence of the United States, it also regarded its former colonies as a foreign nation, which meant that American merchants were banned from British ports, including ports in the West Indies. As a result, a trade in slaves grew within the United States, as slave owners in the South sold their property to back country settlers in Kentucky, Louisiana, and Tennessee. Yet even as the number of slaves in the southern states was rising, it was falling in the North; by 1787, slavery had been effectively abolished in New England and much challenged in Pennsylvania and New York. Economically, it was significant in only five of the thirteen states, and in only two, South Carolina and Georgia, was it the crux of the economy.

At the convention, it proved impossible to set the matter of slavery aside, both because the question of representation turned on it and because any understanding of the nature of tyranny rested on it. When Madison argued about the inevitability of a majority oppressing a minority, he cited ancient history, and told of how the rich oppressed the poor in Greece and Rome. But he cited, too, modern American history. “We have seen the mere distinction of color made in the most enlightened period of time, the ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.”40 In offering this illustration of oppression, Madison hadn’t intended to make a point about slavery (although he did, inadvertently, make such a point, since what he said that day revealed that he thought “the mere distinction of color” was no basis for bondage); he was trying to convince his fellow delegates that a republic needed to be large, and with an abundance of factions, so that a majority could not oppress a minority. But slavery was how he understood oppression.

Slavery became the crucial divide in Philadelphia because slaves factored in two calculations: in the wealth they represented as property and in the population they represented as people. The two could not be separated.

The most difficult question at the convention concerned representation. States with large populations of course wanted representation in the federal legislature to be proportionate to population. States with small populations wanted equal representation for each state. States with large numbers of slaves wanted slaves to count as people for purposes of representation but not for purposes of taxation; states without slaves wanted the opposite. “If . . . we depart from the principle of representation in proportion to numbers, we will lose the object of our meeting,” Pennsylvania’s James Wilson warned on June 9.41 That same day, or probably later that evening, Benjamin Franklin, catching up on his correspondence, distributed to notable antislavery leaders around the world copies of the new constitution of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, “for in this business the friends of humanity in every Country are of one Nation and Religion.”42 Franklin spoke at the convention on the question of representation, but it was Wilson, his fellow Pennsylvanian, who treated the matter squarely. Better than any other delegate, Wilson understood the nature of the political divide—a divide that would, in a matter of decades, sunder the Union.

On July 11, Wilson asked why, if slaves were admitted as people, they weren’t “admitted as Citizens.” And “then why are they not admitted on an equality with White Citizens?” And, if they weren’t admitted as people, “Are they admitted as property? Then why is not other property admitted into the computation?”

The convention was very nearly at an impasse, broken only by a deal involving the Northwest Territory—a Northwest Ordinance decreeing that any new states entering the Union formed north of the Ohio River would be without slavery, while those south of the Ohio would continue slavery. This measure passed on July 13. Four days later, the convention adopted what’s known as the Connecticut compromise, establishing equal representation in the Senate, with two senators for each state, and proportionate representation in the House of Representatives, with one representative for every 40,000 people (at the very last minute this number was changed to 30,000). And, for purposes of representation, each slave would count as three-fifths of a person—the ratio that Madison had devised in 1783. A federal census, conducted every ten years, was instituted to make the count.43

The most remarkable consequence of this remarkable arrangement was to grant slave states far greater representation in Congress than free states. In 1790, the first Census of the United States counted 140,000 free citizens in New Hampshire, which meant that the Granite State got four seats in the House of Representatives. But South Carolina, with 140,000 free citizens and 100,000 slaves, got six seats. The population of Massachusetts was greater than the population of Virginia, but Virginia had 300,000 slaves and so got five more seats. If not for the three-fifths rule, the representatives of free states would have outnumbered representatives of slave states by 57 to 33.44

During a break in the proceedings in August, Madison attended to his own affairs. A slave named Anthony, seventeen, had run away from Montpelier; Madison asked his erstwhile human property, Billey, now William Gardener, if he knew where Anthony might have gone.45 Anthony had gone looking to be five-fifths of a person.

Franklin spent the break resting, and pondering the problem of slavery. He’d planned to introduce a proposal calling for a statement of principle condemning both the trade and slavery itself, but northern delegates had convinced him to withdraw it because the compromise was so fragile. Massachusetts delegate Rufus King spent the adjournment rethinking his concession to the three-fifths clause. And when deliberations resumed, King proposed that Congress at least be granted the authority to abolish the slave trade, whereupon the South Carolina delegation made clear that any attempt to restrict the trade would force them to leave the convention.

This Luther Martin could not abide. Martin, the son of New Jersey farmers, had been a schoolmaster before he became a lawyer; in 1778, he’d been appointed Maryland’s attorney general. Martin declared that the trade in slaves “was inconsistent with the principles of the Revolution and dishonorable to the American character.” He was short and red-faced, as slovenly as he was brilliant. “His genius and vices were equally remarkable,” it was said.46 But he proved a man of principle. He withdrew from the convention, refused to sign the Constitution, and opposed its ratification, warning that “national crimes can only be, and frequently are, punished in this world by national punishments.”47 John Rutledge dismissed Martin’s argument. Rutledge, forty-eight, had served in the South Carolina assembly, the Stamp Act Congress, and the Continental Congress, and as governor of his state; he proved to be the South’s most determined defender. “The true question at present,” he insisted, “is whether the Southern states shall or shall not be parties to the Union.”

New Englanders ceded the point. “Let every state import what it pleases,” said Connecticut’s Oliver Ellsworth. Ellsworth, a devout Christian, had prepared for a career in the ministry before becoming a lawyer. “The morality or wisdom of slavery are considerations belonging to the states themselves,” he said. He also believed that the institution was on the wane: “Slavery, in time, will not be a speck in our country.”

A compromise between those opposed to the slave trade and those in favor of it was reached with a motion that Congress should be prohibited from interfering with the slave trade for a period of twenty years. Madison was aggrieved. He’d have preferred no mention of slavery in the Constitution at all. “So long a term will be more dishonorable to the national character than to say nothing about it in the Constitution,” he warned. Gouverneur Morris, who’d lost a leg to a carriage wheel and the use of an arm to a boiling pot of water, was appalled at the entire bargain, and decided to deliver a lecture. “The inhabitant of Georgia and S.C. who goes to the Coast of Africa, and in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections & damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes in a Govt. instituted for protection of the rights of mankind, than the Citizen of Pa. or N. Jersey who views with a laudable horror, so nefarious a practice.” He said he “would sooner submit to a tax for paying for all the Negroes in the United States than saddle posterity with such a Constitution.” As Morris pointed out, the delegates were there to build a republic, but there was nothing more aristocratic than slavery. He called it “the curse of heaven.”48

The Constitution would not lift that curse. Instead, it tried to hide it. Nowhere do the words “slave” or “slavery” appear in the final document. “What will be said of this new principle of founding a right to govern Freemen on a power derived from slaves,” Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson wondered—correctly, as it would turn out. He predicted: “The omitting the Word will be regarded as an Endeavour to conceal a principle of which we are ashamed.”49

Five days before the close of the convention, George Mason proposed adding a bill of rights. “A bill might be prepared in a few hours,” he urged. But Mason’s proposal was struck down; not a single state voted in favor of it, mainly because most states already had a bill of rights, but also because the delegates were exhausted and eager to go home.

By Monday, September 17, 1787, after four months of arduous debate, a polished draft was at last ready for signatures. After the document was read out loud for the very first time, Franklin, crippled by gout, struggled to rise from his chair but, as had happened many times during the convention, he found he was too weary to make a speech. Wilson, half Franklin’s age, read his remarks instead.

“Mr. President,” he began, addressing Washington, “I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them.” He suggested that he might, one day, change his mind. “For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others.” Hoping to pry open the minds of delegates who were closed to the compromise before them, he reminded them of the cost of zealotry. “Most men indeed as well as most sects in Religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them it is so far error.” But wasn’t humility the best course, in such circumstances? “Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution,” he closed, “because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best.”50

It was four o’clock in the afternoon when the delegates began signing the bottom of the last of the document’s four sheets of parchment. Mason was among the delegates who refused to sign. Washington sat in a chair in front of a window. Franklin understood the importance of political theater. He ventured that he had often wondered, during the many long days at the convention when he’d lost track of the time, whether the sun he could see outside the window, like the sun carved on the back of Washington’s chair, was rising or setting. “But now at length,” he said, “I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.”51

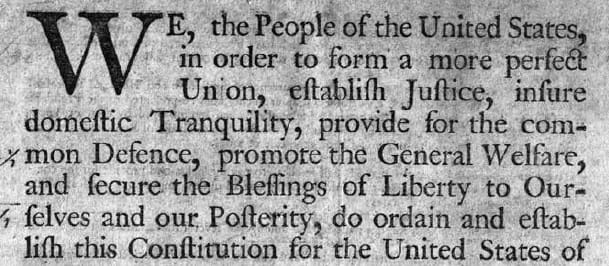

The day after the convention adjourned, what had been kept for so long strictly secret and had only so lately been written on parchment was copied and made public, printed in newspapers and on broadsheets, often with “We the People” set off in extra-large type. Washington sent a copy to Lafayette in Paris: “It is now a Child of fortune.” As Madison explained, the Constitution is “of no more consequence than the paper on which it is written—a blank page—unless it be stamped with the approbation of those to whom it is addressed. . . . THE PEOPLE THEMSELVES.”52

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE had been signed by members of the Continental Congress; it had never been put to a popular vote. The Articles of Confederation had been ratified in the states, not by the people, but by the state legislatures. Except for the Massachusetts Constitution, in 1780, and the second New Hampshire Constitution, in 1784, no constitution, no written system of government, had ever before been submitted to the people for their approval. “This is a new event in the history of mankind,” said the governor of Connecticut at his state’s ratification convention.53

The debate over ratifying the Constitution produced some of the most heated political writing in American history, not only in American newspapers but in hundreds of broadsides and pamphlets. The argument in favor of ratification was made, eloquently and persuasively, in eighty-five essays, known as The Federalist Papers, published between October 1787 and May 1788 under the pen name Publius. Ambitious, young, red-haired Alexander Hamilton, who hadn’t played much of a role at the constitutional convention, and who thought the Constitution created a government too democratic, wrote fifty-one of the essays. Madison wrote another twenty or so, and John Jay wrote the rest.

The debate, waged in ratifying conventions but, even more thrillingly, in the nation’s weekly newspapers, established the structure of the new nation’s two-party system. Against the Federalists stood the unfortunately named Anti-Federalists, who opposed ratification. If it hadn’t been for the all-or-nothing dualism of this choice, and a partisan press, the United States might well have a multiparty political culture.

The Anti-Federalists generally charged that the Constitution amounted to a conspiracy against their liberties, not least because it lacked a bill of rights. Jefferson, from Paris, made this complaint: “A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth.”54 Anti-Federalists also argued that Congress was too small; here they cited John Adams, who’d written that a legislature “should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large.” Influenced by Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws (1748), Anti-Federalists believed that a republic had to be small and homogeneous; the United States was too big for this form of government. They also charged that the Constitution was difficult to read, and that its difficulty was further evidence that it was part of a conspiracy against the understanding of a plain man, as if it were willfully incomprehensible. “The constitution of a wise and free people,” Anti-Federalists insisted, “ought to be as evident to simple reason, as the letters of our alphabet,” as easy to read as Common Sense. “A constitution ought to be, like a beacon, held up to the public eye, so as to be understood by every man,” Patrick Henry declared.”55

Anti-Federalists, including former delegates to the convention, also contested the three-fifths clause. Luther Martin called it a “solemn mockery of and insult to God” and said that the clause “involved the absurdity of increasing the power of a state . . . in proportion as that state violated the rights of freedom.”56 Madison defended this decision, insisting that there was no other way to count slaves except as both persons and property, since this “is the character bestowed on them by the laws under which they live.”57

Ratification proved to be a nail-biter. By January 9, 1788, five states—Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—had ratified. The debate that began in mid-January at the convention in Massachusetts grew heated. “You Perceive we have some quarilsome spirits against the constitution,” Jane Franklin reported to her brother from Massachusetts. “But,” she reassured him, “it does not appear to be those of Superior Judgment.”58 After Federalists promised they’d propose a bill of rights at the first session of the new Congress, Massachusetts, in a squeaker, voted in favor of ratification by a vote 187 to 168 in February. In March, Rhode Island, which had refused to send any delegates to the constitutional convention, refused to hold a ratifying convention. Maryland ratified in April, South Carolina in May, New Hampshire in June. That made nine states in favor, meeting the minimum required.

Practically, though, the approval of Virginia and New York was essential. At Virginia’s convention, Patrick Henry argued that the Constitution was an assault on the sovereignty of the states: “Have they made a proposal of a compact between states? If they had, this would be a confederation: It is otherwise most clearly a consolidated government. The question turns, sir, on that poor little thing—the expression, We, the people, instead of the states, of America.”59 But Federalists eventually prevailed, by a vote of 89 to 79, on June 25, 1788.

On the Fourth of July, James Wilson, with full-throated passion, spoke at a parade in Philadelphia, while a ratifying convention met in New York. “You have heard of Sparta, of Athens, and of Rome; you have heard of their admired constitutions, and of their high-prized freedom,” he told his audience. Then he asked a series of rhetorical questions. But were their constitutions written? The crowd called back, “No!” Were they written by the people? No! Were they submitted to the people for ratification? No! “Were they to stand or fall by the people’s approving or rejecting vote?” No, again.

Three weeks later, New York ratified by the smallest of margins: 30 to 27.60 By three votes, the Constitution became law. And yet the political battle raged on. The day after the vote, Thomas Greenleaf, the only Anti-Federalist printer in Federalist-dominated New York City, arrived home in the evening to find that a band of Federalists had fired musket balls into his house. He loaded two pistols, put them in a chest near his bed, and went to sleep, only to be awakened in the middle of the night by men shouting outside his house. When a mob began breaking down his door, smashing windows, and throwing stones, Greenleaf shot into the crowd from a second-story window, tried to reload, then decided to run. After he and his wife and children made a narrow escape out the back door, the mob swarmed his house and office and destroyed his type and printing press, a bad omen for a nation founded on the freedom of speech.61

Ratification had been an agony. It might very easily have gone another way. An unruly new republic had begun.

III.

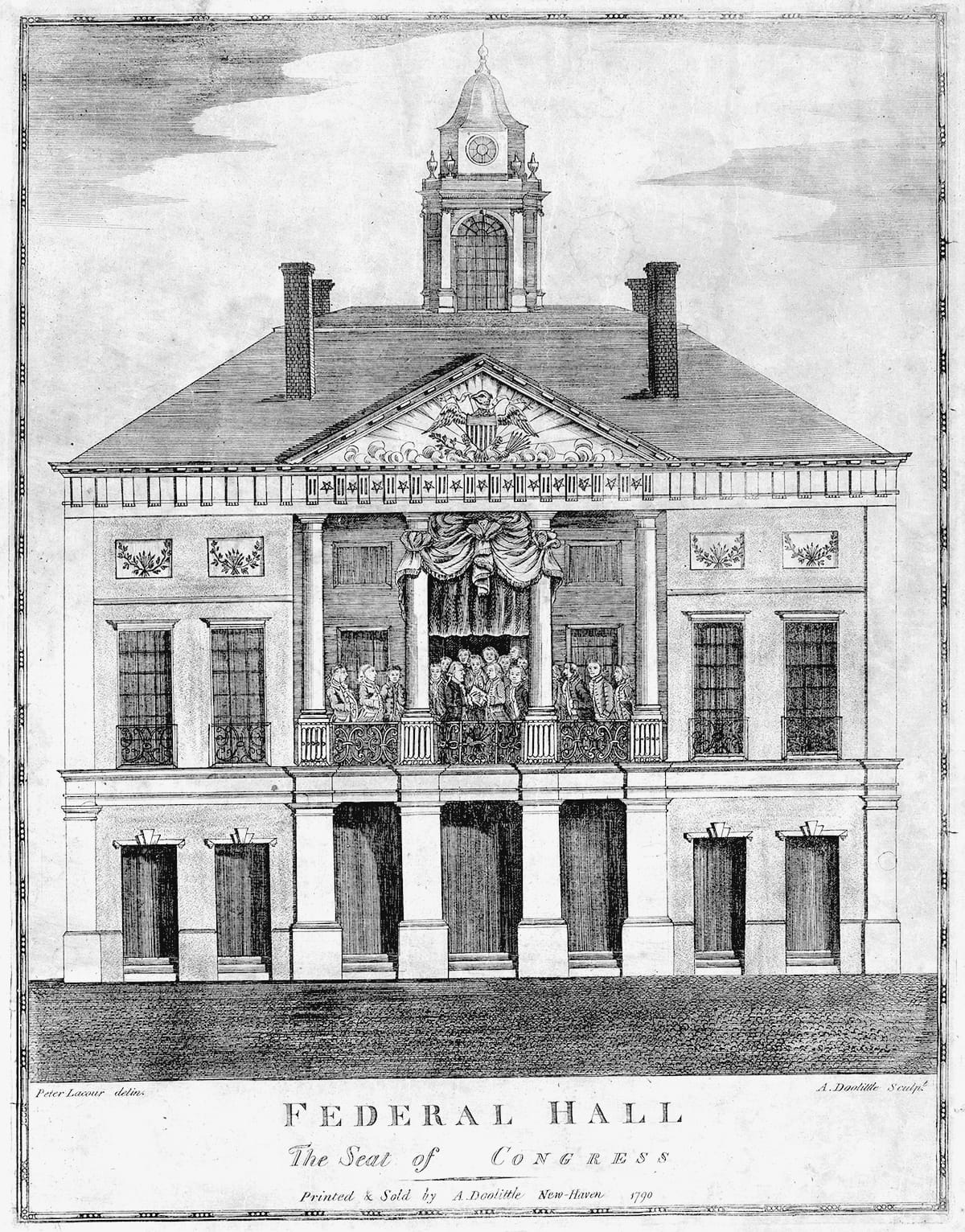

THE FIRST CONGRESS convened on March 4, 1789, in New York’s city hall, where the German printer John Peter Zenger had been tried in 1735, where a black man named Caesar had met his fate in 1741, and where the Stamp Act Congress had deliberated in 1765, each another trial for freedom. Renamed Federal Hall, the building was refitted to its new purpose, enlarged, improved, and made majestic, with Tuscan columns and Doric pillars, according to a plan designed by the French architect Pierre Charles l’Enfant, who, when the federal government moved to the banks of the Potomac, would one day design the nation’s capital. In L’Enfant’s hands, city hall grew to three times its original size, its aesthetic founding a new architectural style: Federal. Above a grand new balcony, facing Wall Street, a giant eagle, carrying thirteen arrows, appeared to burst out of the clouds. A new cupola boasted half-circle windows, eyes to the sky.62

For all its pomp, Federal Hall was a monument to republicanism: the building opened its doors to the people. The Constitution requires that “Each House shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same.” The Congressional Record was published, because it had to be, but Congress decided to make its proceedings public in an altogether different way. Pennsylvania’s 1776 Constitution had decreed that “the doors of the house . . . shall be and remain open for the admission of all persons who behave decently,” and the House of Representatives followed this precedent, opening its doors from its first session. The representatives’ hall, arched and octagonal, was two stories tall, with large galleries for spectators.63

The new president wasn’t inaugurated until April 30; the delay was due to the time it took to conduct the first presidential election. Washington had run unopposed, but there remained the matter of counting the votes. Exactly how the new president was to assume his office was not immediately clear. The Constitution calls only for a president to take an oath, swearing to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Hours before Washington’s inauguration was scheduled to take place, a special congressional committee decided that it might be fitting for the president to rest his hand on a Bible while taking the oath of office. Unfortunately, no one in Federal Hall had a copy of the Bible on hand. There followed a mad dash to find one. At midday, above a crowd assembled on Wall Street, Washington took his oath standing on a balcony, below that eagle bursting from the clouds.

He pledged, and then he kissed his borrowed Bible. After Washington was sworn in, he entered Federal Hall and delivered a speech that had been written by Alexander Hamilton. The Constitution does not call for an inaugural address. But Washington had a sense of occasion. He began by addressing his remarks to “Fellow-Citizens of the Senate and the House of Representatives.” He was speaking to Congress, in that arched, octagonal room, but he invoked the people. “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of Government,” Washington said, are “staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”64

Nearly everything Washington did set a precedent. What would have happened if he had decided, before taking that oath of office, to emancipate his slaves? He’d grown disillusioned with slavery; his own slaves, and the greater number of slaves owned by his wife, were, to him, a moral burden, and he understood very well that for all the wealth generated by forced, unpaid labor, the institution of slavery was a moral burden to the nation. There is some evidence—slight though it is—that Washington drafted a statement announcing that he intended to emancipate his slaves before assuming the presidency. (Or maybe that statement, like Washington’s inaugural address, had been written by Hamilton, a member of New York’s Manumission Society.) This, too, Washington understood, would have established a precedent: every president after him would have had to emancipate his slaves. And yet he would not, could not, do it.65 Few of Washington’s decisions would have such lasting and terrible consequences as this one failure to act.

THE CONSTITUTION DOESN’T say much about the duties of the president. “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States,” according to Article II, Section 2, and “he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices.” But the Constitution doesn’t call for a cabinet. Nevertheless, the first Congress established several departments, to which Washington appointed secretaries: the Department of State, headed by Jefferson; the Department of the Treasury, headed by Hamilton, and the Department of War, headed by Henry Knox.

Congress’s most pressing order of business was drafting a bill of rights. Madison, having prepared a bill “to make the Constitution better in the opinion of those who are opposed to it,” presented a list of twelve amendments to the House on June 8. He had wanted the amendments written into the constitution, each in its proper place, but instead they were added at the end.66

While Madison’s proposed amendments were debated and revised, Congress tackled the question of the national judiciary. Article III, Section 1, decrees that “The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court,” but the details were left to Congress. On September 24, 1789, Washington signed the Judiciary Act, which established the number of justices, six; defined the authority of the court, which was narrow; and created the office of attorney general, to which Washington appointed Edmund Randolph.

Under the Constitution, the power of the Supreme Court is quite limited. The executive branch holds the sword, Hamilton had written in Federalist 78, and the legislative branch the purse. “The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever.” All judges can do is judge. “The judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of powers,” Hamilton concluded, citing, in a footnote, Montesquieu: “Of the three powers above mentioned, the judiciary is next to nothing.”67

The Supreme Court had no rooms in Federal Hall. Instead, it met—when it met—in a drafty room on the second floor of an old stone building called the Merchants’ Exchange, at the corner of Broad and Water Streets. The ground floor, an arcade, served as a stock exchange. Lectures and concerts were held upstairs. On the first day the court was called to session, only three justices showed up, and so, lacking a quorum, court was adjourned.68

The day after Washington signed the Judiciary Act, Congress sent Madison’s twelve constitutional amendments to the states for ratification. Meanwhile, Congress took up other business, and was immediately confronted with the question of slavery. On February 11, 1790, a group of Quakers presented two petitions, one from Philadelphia and one from New York, urging Congress to end the importation of slaves and to gradually emancipate those already held. In the octagonal room in Federal Hall, after representatives from Georgia and South Carolina rose to condemn the petitions, Madison moved to put the petitions to a committee. The next day, Congress received a petition from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society urging Congress to “take such measures in their wisdom, as the powers with which they are invested will authorize, for promoting the abolition of slavery, and discouraging every species of traffic in slaves”; its signatories included Benjamin Franklin.

After several hours of debate—before spectators in the galleries—Congress voted 43 to 11 to refer all three petitions to a committee (seven of the eleven “no” votes came from Georgia and South Carolina). On March 8, the day scheduled for the committee report, southern delegates succeeded in delaying it. James Jackson of Georgia gave a two-hour speech, in which he said that the Constitution was a “sacred compact,” and William Loughton Smith of South Carolina spoke for another two hours, opposing emancipation by insisting that if blacks were free they would marry whites, “the white race would be extinct, and the American people would be all of the mulatto breed.”69

Not so many miles away from New York, men, women, and children who had once been owned by some of the people who were engaged in this debate were engaged in a debate of their own. Harry Washington, who had left New York for Halifax in 1783, wondered whether he ought to move his family to a new colony, in West Africa. The first expedition to Sierra Leone had sailed from London in May of 1787, just as the delegates to the constitutional convention were straggling into Philadelphia. As some four hundred emigrants prepared to sail, the African-born writer and former slave Quobna Ottobah Cugoano had warned them that “they had better swim to shore, if they can, to preserve their lives and liberties in Britain, than to hazard themselves at sea . . . and the peril of settling at Sierra Leone.” They sailed all the same. Across the Atlantic, they’d founded a capital and elected as their governor a runaway slave and Revolutionary War veteran from Philadelphia named Richard Weaver. Five months later, plagued by disease and famine, 122 of the settlers had died. Even worse, and exactly as Cugoano had predicted, some were kidnapped and sold into slavery all over again. But for some, Sierra Leone was home. Frank Peters, kidnapped as a child, had spent most of his life as a field slave in South Carolina until he joined the British army in 1779. Two weeks after he arrived in Sierra Leone, at the age of twenty-nine, an old woman found him, held him, and pressed him close: she was his mother.70

Harry Washington decided, in the end, to join nearly twelve hundred black refugees from the United States who boarded fifteen ships in Halifax Harbor, bound for the west coast of Africa, along with black preachers Moses Wilkinson and David George. Before the convoy left the harbor, each family was handed a certificate “indicating the plot of land ‘free of expence’ they were to be given ‘upon arrival in Africa.’” But when Washington reached Sierra Leone, he found that the colony’s new capital, Free-town, was plagued by disease and weighed down by a poverty enforced by exorbitant rents. “We wance did call it Free Town,” Wilkinson complained bitterly, but “we have a reason to call it a town of slavery.”71

In New York, a slave town, the congressional committee charged with responding to the antislavery petitions finally presented its report. The Constitution forbade Congress from outlawing the slave trade until the year 1808 but provided for taxing imported goods, the committee reported, and that authority included the power to tax the slave trade heavily enough to discourage and even to end it. Madison, quiet of voice, stood to speak. He urged the committee to eliminate this allowance on revising the report. It had been a tiny window, the smallest of openings. Madison slammed it shut. The final report concluded, “Congress have no authority to interfere in the emancipation of slaves, or in the treatment of them within any of the States; it remaining with the several States alone to provide any regulations therein, which humanity and true policy may require.” A resolution to accept the report passed 29 to 25, along sectional lines. It effectively tabled the question of slavery until 1808.72

Franklin, from his deathbed, attempted to protest. Earlier, he’d tried to reassure his sister, “As to the Pain I suffer, about which you make yourself so unhappy, it is, when compar’d with the long life I have enjoy’d of Health and Ease, but a Trifle.”73 But this was the merest dissembling. He was in agony. Writing in the Pennsylvania Gazette, he offered an attack on slavery, signing his essay “Historicus”—the voice of history.74

He died two weeks later. He was the only man to have signed the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Paris, and the Constitution. His last public act was to urge abolition. Congress would not hear of it.

THE DIVIDE OVER slavery, which had nearly prevented the forming of the Union, would eventually split the nation in two. There were other fractures, too, deep and lasting. The divide between Federalists and Anti-Federalists didn’t end with the ratification of the Constitution. Nor did it end with the ratification of the Bill of Rights. On December 15, 1791, ten of the twelve amendments drafted by Madison were approved by the necessary three-quarters of the states; these became the Bill of Rights. They would become the subject of ceaseless contention.

The Bill of Rights is a list of the powers Congress does not have. The First Amendment reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Its tenets derive from earlier texts, including Madison’s 1785 “Memorial Remonstrance against Religious Assessments” (“The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man”), Jefferson’s 1786 Statute for Religious Freedom (“our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions any more than our opinions in physics or geometry”), and Article VI of the Constitution (“no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States”).75

Yet the rights established in the Bill of Rights were also extraordinary. Nearly every English colony in North America had been settled with an established religion; Connecticut’s 1639 charter explained that the whole purpose of government was “to mayntayne and presearve the liberty and purity of the gospel of our Lord Jesus.” In the century and a half between the Connecticut charter and the 1787 meeting of the constitutional convention lies an entire revolution—not just a political revolution but also a religious revolution. So far from establishing a religion, the Constitution doesn’t even mention “God,” except in naming the date (“the year of our Lord . . .”). At a time when all but two states required religious tests for office, the Constitution prohibited them. At a time when all but three states still had an official religion, the Bill of Rights forbade the federal government from establishing one. Most Americans believed, with Madison, that religion can only thrive if it is no part of government, and that a free government can only thrive if it is no part of religion.76

With the ratification of the Bill of Rights, new disputes emerged. Much of American political history is a disagreement between those who favor a strong federal government and those who favor the states. During Washington’s first term, this dispute took the form of a debate over the economic plan put forward by Hamilton. Much of this debate concerned debt. First stood private debt. The depression that followed the war had left many Americans insolvent. There were so many men confined to debtors’ prison in Philadelphia that they printed their own newspaper: Forlorn Hope.77 Second stood the debts incurred by the states during the war. And third stood the debts incurred by the Continental Congress. Until these government debts were paid, the United States would have no lenders and no foreign investors and would be effectively unable to participate in world trade.

Hamilton proposed that the federal government not only pay off the debts incurred by the Continental Congress but also assume responsibility for the debts incurred by the states. To this end, he urged the establishment of a national bank, like the Bank of England, whose benefits would include stabilizing a national paper currency. Congress passed a bill establishing the Bank of the United States, for a term of twenty years, in February 1790. Before signing the bill into law, Washington consulted with Jefferson, who advised the president that Hamilton’s plan was unconstitutional because it violated the all-purpose Tenth Amendment, which reads: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” The Constitution does not specifically grant to Congress the power to establish a national bank, and, since the Tenth Amendment says that all powers not granted to Congress are held by either the states or by the people, Congress cannot establish a national bank. Washington signed anyway, establishing a precedent for interpreting the Constitution broadly, rather than narrowly, by agreeing with Hamilton’s argument that establishing a national bank fell under the Constitution’s Article I, Section 8, granting to Congress the power “To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper,” the very opposite of how Congress had interpreted its power to tax the slave trade.

Other elements of Hamilton’s plan raised other objections. States that had already paid off their war debts, like Virginia and Maryland, objected to the federal government’s assumption of state debt, since federal taxes levied in Virginia and Maryland would now be used to pay a burden incurred by states that had not yet paid their debts, like South Carolina and Massachusetts. The idea that this plan was unconstitutional, Hamilton believed, was “the first symptom of a spirit which must either be killed or will kill the constitution of the United States.” Hamilton brokered a deal. Southerners were also averse to Hamilton’s economic plan because it emphasized manufacturing over agriculture and therefore seemed disadvantageous to the southern states. Also on the congressional agenda was where to locate the nation’s capital. The First Congress met for its first two sessions in New York and for its second two sessions in Philadelphia. The Continental Congress had also met in Baltimore and Princeton, and in half a dozen other places. Where it and the other branches of the federal government should permanently meet was a vexing question, given the sectional tensions that had plagued the Union from the start. In a deal worked out with Madison over dinner at Jefferson’s rooms on Maiden Lane, in New York—and known as the “dinner table bargain”—Hamilton threw his support behind a plan to locate the nation’s capital in the South, in exchange for Madison’s support and the support of his fellow southerners for Hamilton’s plan for the federal government to assume the states’ debts. In July 1790, Congress passed Hamilton’s assumption plan, and voted to establish the nation’s capital on a ten-mile square stretch of riverland along the Potomac River, in what was then Virginia and Maryland, and to found, as mandated in the Constitution, a federal district. It would be called Washington.78

Hamilton believed that the future of the United States lay in manufacturing, freeing Americans of their dependence on imported goods, and spurring economic growth. To that end, his plan included raising the tariff—taxes on imported goods—and providing federal government support to domestic manufacturers and merchants. Congress experimented, briefly, with domestic duties (including taxes on carriages, whiskey, and stamps). Before the Civil War, however, the federal government raised revenue and regulated commerce almost exclusively through tariffs, which, unlike direct taxes, skirted the question of slavery and were therefore significantly less controversial. Also, tariffs appeared to place the burden of taxation on merchants, which appealed to Jefferson. “We are all the more reconciled to the tax on importations,” Jefferson explained, “because it falls exclusively on the rich.” The promise of America, Jefferson thought, was that “the farmer will see his government supported, his children educated, and the face of his country made a paradise by the contributions of the rich alone.”79

But Hamilton’s critics, Jefferson chief among them, charged that Hamilton’s economic plan would promote speculation, which, indeed, it did. To Hamilton, speculation was necessary for economic growth; to Jefferson, it was corrupting of republican virtue. This matter came to a head in 1792, when speculation led to the first financial panic in the new nation’s history.

As with so many financial crises, the story began with ambition and ended with corruption. Hamilton had been befriended by John Pintard, an importer with offices at 12 Wall Street. Pintard had been elected to the state legislature in 1790; the next year, he’d become a partner of Leonard Bleecker, who happened to be the secretary of New York’s Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors: together, they auctioned stock. After Bleecker dissolved their partnership, Pintard began dealing with Hamilton’s assistant secretary of the Treasury, William Duer, a rogue who had the idea of cornering stock in the Bank of the United States. With Pintard acting as his agent, Duer borrowed the life savings of “shopkeepers, widows, orphans, Butchers, Carmen, Gardners, market women.” In 1792, when it became clear that over a million dollars’ worth of bank notes, signed by Pintard, weren’t worth the paper on which they were printed, Duer and Pintard’s insolvency triggered the nation’s first stock market crash. A mob attempted to stone Duer to death and then chased him to debtors’ prison. Pintard hid in his Manhattan town house. “Would it not be prudent for him to remove to a State where there is a Bankrupt Act?” one friend wondered.80 Pintard fled across the river to New Jersey, where he was eventually found, and sent to debtors’ prison.

Even the most eminent of men could not escape confinement for debt. James Wilson, the most democratic delegate to the constitutional convention, and now a Supreme Court justice, fell so badly into debt that he was afraid to ride circuit, for fear of being captured by his creditors and clapped in chains. (He owed nearly $200,000 to Pierce Butler, who’d been a South Carolina delegate to the constitutional convention.) In 1797, Wilson joined Pintard in debtors’ prison in New Jersey, and, although he managed to get out by borrowing $300 from one of his sons, he was thrown into another debtors’ prison, in North Carolina, the next year, where his wife found him in ragged, stained clothes. He soon contracted malaria. Only fifty-six years old, he died of a stroke, raving, deliriously, about his debts.81

Hamilton determined that the United States should have unshakable credit. The nation’s debts would be honored: private debt could be forgiven. In the new republic, individual debts—the debts of people who took risks—could be discharged. Pintard got out of debtors’ prison by availing himself of a 1798 New Jersey insolvency law; later, he filed for bankruptcy under the terms of the first U.S. bankruptcy law, passed in 1800.82 He was legally relieved of the obligation ever to repay his debts, his ledger erased. The replacement of debtors’ prison with bankruptcy protection would change the nature of the American economy, spurring investment, speculation, and the taking of risks.

The Panic of 1792 had this effect, too: it led New York brokers to sign an agreement banning private bidding on stocks, so that no one, ever again, could do what Duer had done; that agreement marks the founding of what would become the New York Stock Exchange.

IV.

“IT IS AN AGE of revolutions, in which everything may be looked for,” Thomas Paine wrote from England in 1791, in the first part of Rights of Man. He soon fled England for France, where he wrote the second part. “Where liberty is, there is my country,” Franklin once said, to which Paine is supposed to have replied, “Wherever liberty is not, there is my country.”83 The one country where Paine didn’t try to rile up revolution was Haiti. It was an age of revolutions, but Paine wasn’t looking for a slave rebellion.

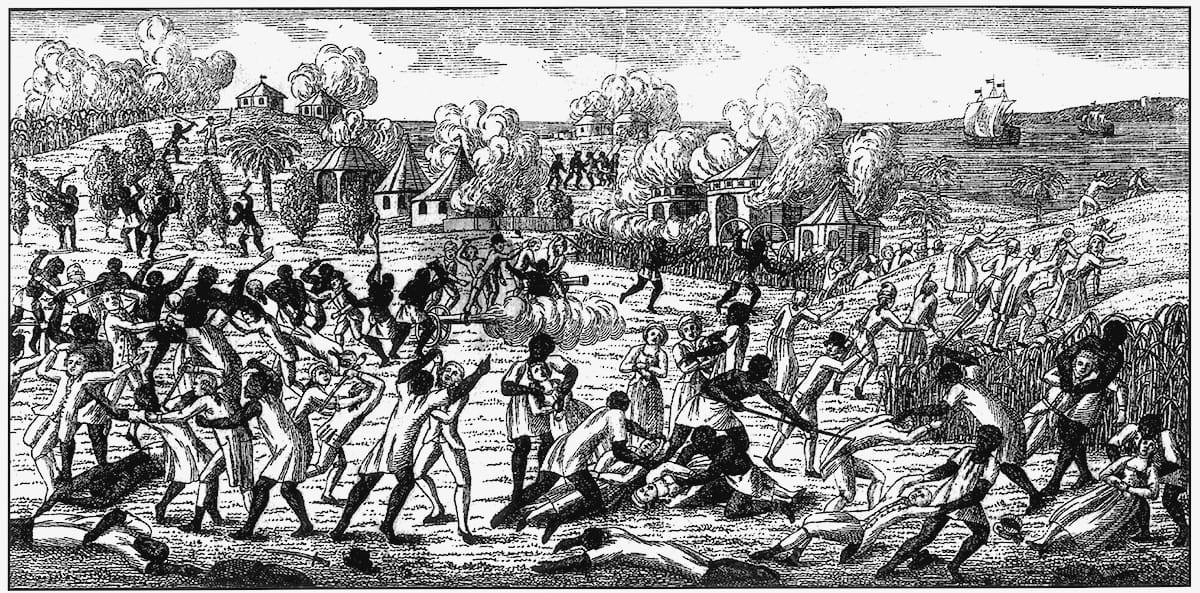

Haiti, then known as Saint-Domingue, was the largest colony in the Caribbean, and the richest. France’s most vital colony, its population consisted of 40,000 whites, 28,000 free people of color, and 452,000 slaves—half the slave population of the entire Caribbean. The world’s leading producer of sugar and coffee, the island exported nearly as much sugar as Jamaica, Cuba, and Brazil combined.84 Its revolution began in 1791.

The events that unfolded in Haiti followed France’s own, tortured revolution, begun in the spring of 1789. Members of a special legislature called in response to France’s own difficulties with war debt defied the king, formed themselves into a National Assembly, abolished the privileges of the aristocracy, and set about drafting a constitution. In August, Lafayette introduced into the assembly a Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Article I read, “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.”85

Paine was in Paris during the Reign of Terror, when Louis XVI was beheaded. Paine himself was arrested. He wrote most of the second part of The Age of Reason from a cell while the prison’s inmates went daily to their deaths. In six weeks in the summer of 1794, more than thirteen hundred people were executed.86

The French Revolution had gone too far, a revolution that never stopped. But, though it terrified Americans, it held for most Americans not half the fear that was inspired by the revolution in Haiti in 1791, where hundreds of thousands of slaves cast off their chains. They were led at first by a man named Boukman and, after Boukman’s death, by an ex-slave named Toussaint Louverture. Their slave rebellion was a war for independence, the second in the Western world.

American owners of slaves were terrified by the events unfolding in Haiti—their darkest fears realized. But to some radicals in New England, the Haitian revolution was the inevitable next step in the progress of the freedom of man. Abraham Bishop, a Connecticut Jeffersonian, was one of a handful of Americans to welcome the revolution. “If Freedom depends upon colour, and if the Blacks were born for slaves, those in the West-India islands may be called Insurgents and Murderers,” Bishop observed, in a series of essays called “The Rights of Black Men,” published in Boston. “But the enlightened mind of Americans will not receive such ideas,” Bishop went on. “We believe that Freedom is the natural right of all rational beings, and we know that the Blacks have never voluntarily resigned that freedom. Then is not their cause as just as ours?”

The answer his fellow Americans gave was a resounding no. Instead, American newspapers reported on the Haitian revolution as a kind of madness, a killing frenzy. “Nothing can be more distressing than the situation of the inhabitants, as their slaves have been called into action, and are a terrible engine, absolutely ungovernable,” Jefferson wrote. So far from extending statements about the equality of “all men” to all men, white or black, the revolution on Saint-Domingue convinced many white Americans of the reverse. Between 1791 and 1793, the United States sold arms and ammunition and gave hundreds of thousands of dollars in aid to the French planters on the island.87 Federalists tended to be more worried about France than about Haiti. Republicans, especially southerners, were worried about a spreading revolution. Jefferson, calling the Haitians “cannibals,” warned Madison, “If this combustion can be introduced among us under any veil whatever, we have to fear it.”88