Five

A DEMOCRACY OF NUMBERS

IN 1787, WHILE FEDERALISTS AND ANTI-FEDERALISTS were fighting over the proposed Constitution in the mottled pages of American newspapers and on the creaky floors of convention halls, John Adams, minister to Britain, grumbled at his desk in Grosvenor Square, London, while Thomas Jefferson, minister to France, leaned over a desk of his own, undoubtedly fancier, at the Hôtel de Langeac on Paris’s Champs-Elysées. Far from home, the two men who had together crafted the Declaration of Independence staged an epistolary debate about the Constitution, exchanging letters across the English Channel, as if they were holding a two-man ratifying convention, Adams worrying that the Constitution gave the legislature too much power, Jefferson fearing the same about the presidency. “You are afraid of the one—I, of the few,” Adams wrote Jefferson. “You are Apprehensive of Monarchy; I, of Aristocracy.” Both men agonized about elections, Jefferson fearing there would be too few, Adams that there would be too many. “Elections, my dear sir,” Adams wrote, “I look at with terror.”1

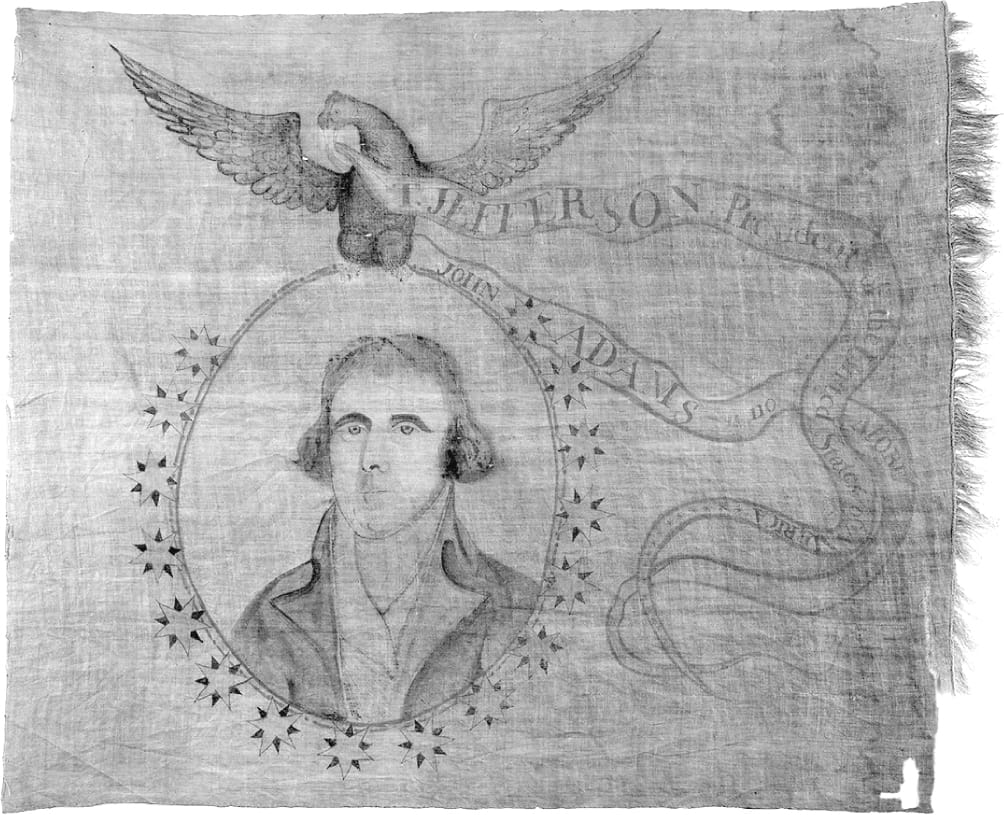

The debate between Adams and Jefferson hadn’t ended after the Constitution was ratified. It hadn’t ended after Washington was elected in 1788, or during his administration, when Adams served as his vice president, and Jefferson as his secretary of state, and it hadn’t ended after Washington was elected again in 1792. Instead, in 1796, their debate helped establish the nation’s first stable political parties.

Jefferson had been worried that the Constitution allowed for a president to serve again and again, till his death, like a king. Adams liked that idea. “So much the better,” he’d written in 1787.2 In 1796, when Washington announced that he wouldn’t run for a third term, Adams and Jefferson each sought to replace him. Adams narrowly won. The two men next faced off in an election Jefferson called “the revolution of 1800.” Whether or not it was a revolution, the election of 1800, the climax of a decades-long debate between Adams and Jefferson, led to a constitutional crisis. The Constitution hadn’t provided for parties, and the method of electing the president could not accommodate them. Nevertheless, Adams ran as a Federalist and Jefferson as a Republican, which meant that, whatever the results of the voting, no one was quite sure of the outcome, especially after the two men received an equal number of votes in the Electoral College, a tie that, under the terms of the Constitution, was to be broken by a vote in the House of Representatives.

Jefferson heard rumors that if he won, Federalists would “break the Union”; he believed they hoped to change the law to allow for Adams to serve for life. “The enemies of our Constitution are preparing a fearful operation,” he warned. Meanwhile, Alexander Hamilton sounded an alarm that if Adams were to be reelected, Virginians would “resort to the employment of physical force” to keep Federalists out of office. It was even said that some Federalists in Congress had decided they’d “go without a Constitution and take the risk of a civil war” rather than elect Jefferson. “Who is to be president?” asked one troubled congressman, and “what is to become of our government?”3

The ongoing argument between Adams and Jefferson was at once a rivalry between two ambitious men, bitter and petty, and a dispute about the nature of the American experiment, philosophical and weighty. In 1800, Adams was sixty-four and even more disputatious, vain, and learned than he’d been as a younger man. A founder of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he’d written a ponderous, three-volume Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, explaining the fragile balance between an aristocracy of the rich and a democracy of the poor, a balance that could only be struck by a well-engineered constitution. “In every society where property exists, there will ever be a struggle between rich and poor,” he wrote. “Mixed in one assembly, equal laws can never be expected. They will either be made by numbers, to plunder the few who are rich, or by influence, to fleece the many who are poor.”4

Jefferson, fifty-seven, president of the American Philosophical Society, by turns moody and frantic, a searing writer, was no less learned, if far more inconsistent, than Adams. He placed his faith in the rule of the majority. The point of the American experiment, he believed, was “to shew by example the sufficiency of human reason for the care of human affairs and that the will of the majority, the Natural law of every society, is the only sure guardian of the rights of man.”5 Adams believed in restraining the will of the majority, Jefferson in submitting to it.

Both men subscribed to the Aristotelian notion that there exist three forms of government, that each could become corrupt, and that the perfect government was the one that best balanced them. Adams believed that the form of government most “susceptible of improvement” was a polity, and that such an improvement could be achieved—and the terrors of democracy avoided—if legislatures were to do a better job of representing the interests of the people by more exactly mirroring them. “The end to be aimed at, in the formation of a representative assembly, seems to be the sense of the people, the public voice,” he wrote. “The perfection of the portrait consists in its likeness.”6

Yet, for all Adams’s talk of portraits and likenesses, the dispute between the two men turned not on art but on mathematics. Government by the people is, in the end, a math problem: Who votes? How much does each vote count?

Adams and Jefferson lived in an age of quantification. It began with the measurement of time. Time used to be a wheel that turned, and turned again; during the scientific revolution, time became a line. Time, the easiest quantity to measure, became the engine of every empirical inquiry: an axis, an arrow. This new use and understanding of time contributed to the idea of progress—if time is a line instead of a circle, things can get better and even better, instead of forever rising and falling in endless cycles, like the seasons. The idea of progress animated American independence and animated, too, the advance of capitalism. The quantification of time led to the quantification of everything else: the counting of people, the measurement of their labor, and the calculation of profit as a function of time. Keeping time and accumulating wealth earned a certain equivalency. “Time is money,” Benjamin Franklin used to say.7

Quantification also altered the workings of politics. No matter their differences, Adams and Jefferson agreed that governments rest on mathematical relationships: equations and ratios. “Numbers, or property, or both, should be the rule,” Adams insisted, “and the proportions of electors and members an affair of calculation.”8 Determining what that rule would be had been the work of the constitutional convention; fixing that rule would be the work of the election of 1800, and of the political reforms to follow, each another affair of calculation.

I.

KINGS ARE BORN; presidents are elected. But how? In Philadelphia in 1787, James Wilson explained, the delegates had been “perplexed with no part of this plan so much as with the mode of choosing the President.” At the convention, Wilson had proposed that the people elect the president directly. But James Madison had pointed out that since “the right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States . . . the latter could have no influence in the election on the score of the Negroes.” That is, in a direct election, the North, which had more voters, would have more votes. Wilson’s proposal was defeated, 12 states to 1.9 Some delegates to the convention had believed Congress should elect the president. This method, known as indirect election, allowed for popular participation in elections while steering clear of the “excesses of democracy”; it filtered the will of the many through the judgment of the few. The Senate, for instance, was elected indirectly: U.S. senators were chosen not by the people but by state legislatures (direct election of senators was not instituted until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment, in 1913). But, for the office of the presidency, indirect election presented a problem: having Congress choose the president violated the principle of the separation of powers.

Wilson had come up with another idea. If the people couldn’t elect the president, and Congress couldn’t elect the president, maybe some other body could elect the president. Wilson suggested that the people elect delegates to an Electoral College, a body of worthy men of means and reputation who would do the actual electing. This measure passed. But Wilson’s compromise stood on the back of yet another compromise: the slave ratio. The number of delegates to the Electoral College would be determined not by a state’s population but by the number of its representatives in the House. That is, the size of a state’s representation in the Electoral College was determined by the rule of representation—one member of Congress for every forty thousand people, with people who were enslaved counting as three-fifths of other people.10 The Electoral College was a concession to slave owners, an affair of both mathematical and political calculation.

These calculations required a census, which depended on the very new science of demography (a founding work, the first edition of Thomas Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population, appeared in 1798). Article I, Section 2, of the Constitution calls for the population of the United States to be counted every ten years. Census takers were to count “the whole number of free Persons” and “all other Persons” but to exclude “Indians not taxed,” meaning Indians who lived as independent peoples, even if they lived within territory claimed by the United States. This first federal census, conducted in 1790, counted 3.9 million people, including 700,000 slaves. The three-fifths clause not only granted slave-owning states a disproportionate representation in Congress but amplified their votes in the Electoral College. Virginia and Pennsylvania, for instance, had roughly equivalent free populations but, because of its slave population, Virginia had three more seats in the house and therefore six more electors in the Electoral College, with the result that, for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the Republic, the office of the president of the United States was occupied by a slave-owning Virginian, with John Adams the only exception.11

There remained still more contentious calculations. How delegates to the Electoral College would be chosen had been left to the states. In 1796, in seven out of sixteen states the people elected delegates; in the rest, state legislatures elected delegates. The original idea had been for delegates to use their own judgment in deciding how to cast their votes in the Electoral College, although they hadn’t had to make much of a decision in 1788 and 1792, since Washington ran unopposed. But by 1796, two political parties having emerged and a decision needing to be made, party leaders had come to believe that delegates ought to do the bidding of the men who elected them. One Federalist complained that he hadn’t chosen his elector “to determine for me whether John Adams or Thomas Jefferson is the fittest man for President of these United States . . . No, I chose him to act, not to think.”12

This ambiguity had resulted in a botched election. Under the Constitution, the candidate with the most Electoral College votes becomes president; the candidate who comes in second becomes vice president. In 1796, Federalists wanted Adams as president and Thomas Pinckney as vice president. But in the Electoral College, Adams got seventy-one votes, Jefferson sixty-eight, and Pinckney only fifty-nine. Federalist electors had been instructed to cast the second of their two votes for Pinckney; instead, many had cast it for Jefferson. Jefferson therefore became Adams’s vice president, to the disappointment of everyone.

During Adams’s stormy administration, the distance between the two parties widened. Weakened by the weight of his own pride and not content with issuing warnings about the danger of parties, Adams attempted to outlaw the opposition. In 1798, while the United States was engaged in an undeclared war with France, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, granting to the president the power to imprison noncitizens he deemed dangerous and to punish printers who opposed his administration: twenty-five people were arrested for sedition, fifteen indicted, and ten convicted; that ten included seven Republican printers who supported Jefferson.13 Jefferson and Madison believed that the Alien and Sedition laws violated the Constitution. If a president overreaches his authority, if Congress passes unconstitutional laws, what can states do? The Constitution does not grant the Supreme Court the authority to decide on the constitutionality of laws passed by Congress; that’s a power that the court decided to exercise on its own, but, in 1798, it hadn’t tried yet. Meanwhile, Jefferson and Madison and other Republicans came up with another form of judicial review: they argued that the states could decide on the constitutionality of federal laws. They wrote resolutions objecting to the Alien and Sedition Acts. Madison wrote a resolution for Virginia; Jefferson wrote one for Kentucky. “Unless arrested on the threshold,” Jefferson warned, the Alien and Sedition laws would drive the states “into revolution and blood, and will furnish new calumnies against republican government, and new pretexts for those who wish it to be believed that man cannot be governed but by a rod of iron.”14

The widening divide between the parties also marked a hardening of views on slavery. During the Haitian revolution, Jefferson, favoring France, wanted, at most, a remote relationship with an island of freed slaves. But the Adams administration, favoring England, wanted to renew trade with the Caribbean island and even to recognize its independence. “Nothing is more clear than, if left to themselves, that the Blacks of St Domingo will be incomparably less dangerous than if they remain the subjects of France,” Timothy Pickering, Adams’s secretary of state, wrote in 1799. Meanwhile, Africans in America found inspiration in news of events in Haiti. In the summer of 1800, a blacksmith named Gabriel, who became known as “the American Toussaint,” led a slave rebellion in Virginia, marching under the slogan “Death or Liberty.” The rebellion failed. Gabriel and twenty-six of his followers were tried and executed. Opponents of slavery predicted that Gabriel’s rebellion would not be the last. “Tho Gabriel dies, a host remains,” warned Timothy Dwight, the president of Yale. “Oppresse’d with slavery’s galling chain.”15

Jefferson believed that the election of 1800 would “fix our national character” and “determine whether republicanism or aristocracy would prevail.” It did, in any event, establish a number of conventions of American politics, including the party caucus and a no-holds-barred style of political campaigning. Early in the year, Federalists and Republicans in Congress, keen to avoid a repetition of the confusion of 1796, held a meeting to decide on their party’s presidential nominee. They called this meeting a “caucus.” (The word is an Americanism; it comes from an Algonquian word for “adviser.”) The Republicans settled on Jefferson, the Federalists on Adams, although Alexander Hamilton tried to convince Federalists to abandon Adams and instead throw their support behind his running mate, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina. “Great and intrinsic defects in his character unfit him for the office of chief magistrate,” Hamilton wrote of Adams, citing “the unfortunate foibles of a vanity without bounds, and a jealousy capable of discoloring every object.”16 Adams held on to the nomination only by the grip of his talons.

The candidates themselves did not campaign; Americans deemed a candidate’s addressing the people directly a form of demagoguery. When Adams made a detour while traveling from Massachusetts to Washington, a Republican newspaper editor demanded, “Why must the President go fifty miles out of his way to make a trip to Washington?” But the lack of participation of the candidates themselves by no means quieted the campaigning, which chiefly took place in the nation’s newspapers. Voters argued in taverns and fields, and even by the side of the road, having the kind of conversations that the Carolina Gazette attempted to capture by printing “A DIALOGUE Between a FEDERALIST and a REPUBLICAN”:

REPUBLICAN. Good morrow, Mr. Federalist; ’tis pleasant weather; what is the news of the day? How are elections going, and who is likely to be our president?

FEDERALIST. For my part I would rather vote for any other man in the country, than Mr. Jefferson.

REPUBLICAN. And why this prejudice against Mr. Jefferson, I pray you?

FEDERALIST. I do not like the man, nor his principles, from what I have heard of him. First, because he holds not implicit faith in the Christian Religion; 2dly, because I fear he is too great an advocate for French principles and politics; and lastly, because I understand he is violently prejudiced against every thing that is of British connection.

They argue on. “What have you or anyone to do with Mr. J.’s religious principles?” the Republican asks, after which their debate nearly ends in fisticuffs.17

Republicans attacked Adams for abuses of office. Federalists attacked Jefferson for his slaveholding—Americans will not “learn the principles of liberty from the slave-holders of Virginia,” cried one—and especially for his views on religion. In Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson had stated his commitment to religious toleration. “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no god,” he’d written. “It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” From their pulpits, Federalist clergymen preached that such an opinion could lead to nothing but unchecked vice, crime, and depravity. One New York minister answered Jefferson: “Let my neighbor once perceive himself that there is no God, and he will soon pick my pocket and break not only my leg but my neck.” And a Federalist newspaper, Gazette of the United States, insisted that the election offered Americans a choice between “GOD—AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT” and “JEFFERSON—AND NO GOD!!!!”18

Republicans answered Federalist hyperbole with still more hyperbole. In 1799, Federalists had unsuccessfully pursued the Philadelphia printer William Duane for sedition. In 1800, Duane printed in his newspaper, the Aurora, a pair of lists, contrasting the two candidates. With a second term under Adams, the nation would endure more of “Things As They Are”:

The principles and patriots of the Revolution condemned.

The Nation in arms without a foe, and divided without a cause.

The reign of terror created by false alarms, to promote domestic feud and foreign war.

A Sedition Law.

An established church, a religious test, and an order of Priesthood.

But if Jefferson were elected, the nation could look forward to “Things As They Will Be”:

The Principles of the Revolution restored.

The Nation at peace with the world and united in itself.

Republicanism allaying the fever of domestic feuds, and subduing the opposition by the force of reason and rectitude.

The Liberty of the Press.

Religious liberty, the rights of conscience, no priesthood, truth, and Jefferson.19

“Take your choice,” James Callender, a Scottish satirist, wrote in a pamphlet called The Prospect before Us, “between Adams, war and beggary, and Jefferson, peace and competency.” Aristocracy or republicanism, order or disorder, virtue or vice, terror or reason, Adams or Jefferson. “Such papers cannot fail to have the best effect,” Jefferson wrote privately of Callender’s pamphlet. For The Prospect before Us, Callender was convicted of sedition. Sentenced to six months’ confinement, he wrote a second volume from jail. Thumbing his nose at his prosecutors, he titled one chapter “More Sedition.”20

The campaigning went on for rather a long time, partly because there was no single national election day in 1800. Instead, voting stretched from March to November. Voting was done in public, not in secret. It also hardly ever involved paper and pen, and counting the votes—another affair of calculation—usually meant counting heads or, rather, counting polls. A “poll” meant the top of a person’s head. (In Hamlet, Ophelia says, of Polonius, “His beard as white as snow: All flaxen was his poll.” Not until well into the nineteenth century did a “poll” come to mean the counting of votes.) Counting polls required assembling—all in favor of the Federalist stand here, all in favor of the Republican over there—and in places where voting was done by ballot, casting a ballot generally meant tossing a ball into a box. The word “ballot” comes from the Italian ballota, meaning a little ball—and early Americans who used ballots cast pea or pebbles, or, not uncommonly, bullets. In 1799, Maryland passed a law requiring voting on paper, but most states were quite slow to adopt this reform, which, in any event, was not meant to make voting secret, voting publicly being understood as an act of republican citizenship.21

The revolution of 1800, as Jefferson saw it, was accomplished “by the rational and peaceable instrument of reform, the suffrage of the people”—a revolution in voting.22 Nevertheless, out of a total U.S. population of 5.23 million, only about 600,000 people were eligible to vote. Only in Maryland could black men born free vote (until 1802, when the state’s constitution was amended to exclude them); only in New Jersey could white women vote (until 1807, when the state legislature closed this loophole). Of the sixteen states in the Union, all but three—Kentucky, Vermont, and Delaware—limited suffrage to property holders or taxpayers, who made up 60–70 percent of the adult white male population. Only in Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Virginia did voters choose their state’s delegates to the Electoral College. In no state did voters cast ballots for presidential candidates: instead, they voted for legislators, or they voted for delegates. Which of these methods each state followed was part of what the election was about in the first place, since one method was more aristocratic, and the other more republican—that’s what Jefferson meant by calling the election a revolution.23

Before the election was over, seven out of the sixteen states in the Union changed or modified their procedures for electing delegates to the Electoral College. This began in the spring of 1800, after Republicans made a strong showing in local elections in New England, and the Federalist-dominated legislatures of Massachusetts and New Hampshire repealed the popular vote and put the selection of Electoral College delegates into their own hands. Some efforts to manipulate the voting were thwarted. When, in an election engineered by Jefferson’s running mate, Aaron Burr, New Yorkers elected a Republican legislature, Hamilton tried to convince the state’s governor, John Jay, to convene the lame-duck Federalist legislature to change the rules, throwing the election of delegates to the people so that the new legislature would not be able to choose Jeffersonian electoral delegates. Hamilton couldn’t stand Adams, but he considered Jefferson a “contemptible hypocrite.”24 What he proposed was patently unethical. But if the result would be “to prevent an atheist in Religion, and a fanatic in politics from getting possession of the helm of State,” Hamilton told Jay, “it will not do to be overscrupulous.” Jay refused.25

When the Electoral College met in December 1800, one error of its design became immediately clear: Adams lost, but the winner remained uncertain. Republican electors were supposed to vote for Jefferson and Burr. For Jefferson to become president, at least one Republican elector had to remember to not vote for Burr, so that Jefferson would win and Burr place second. That someone forgot. Instead, Jefferson and Burr both received seventy-three votes in the Electoral College to Adams’s sixty-five and Pinckney’s sixty-four, the Federalists having remembered to give their presidential candidate one more vote than his running mate. (This problem was fixed in 1804, with the Twelfth Amendment, which separated the election of the president and the vice president.) The Jefferson-Burr tie was thrown to the House, dominated by lame-duck Federalists. Jefferson’s party had just won sixty-seven House seats, compared to the Federalists’ thirty-nine, but these new congressmen had not yet taken office.26 Between Jefferson and Burr, Congress eventually decided in favor of the Virginian. Meanwhile, from New England, Federalist Timothy Pickering dubbed Jefferson a “Negro President” because twelve of his electoral votes were a product of the three-fifths clause. Without these “Negro electors,” as northerners called them, he would have lost to Adams, sixty-five to sixty-one. “The election of Mr. Jefferson to the presidency,” John Quincy Adams remarked, represented “the triumph of the South over the North—of the slave representation over the purely free.”27

ON FEBRUARY 17, 1801, Jefferson was at last elected president. “I shall leave in the stables of the United States seven Horses and two Carriages with Harness,” Adams wrote him. “These may not be suitable for you: but they will certainly save you a considerable Expense.”28 Jefferson was inaugurated on March 4, 1801, one day after the Sedition Act expired. He was the first president to be inaugurated in the new capital city of Washington. Spurning pomp, and refusing to ride on any of John Adams’s seven horses or in either of his two carriages, he walked through the city’s muddy streets, a man of the people. Bostonians insisted that he did not, in fact, walk but instead rode “into the temple of Liberty on the shoulders of slaves.”29

Jefferson’s inauguration marked the first peaceful transfer of power between political opponents in the new nation, a remarkable turning point. The two-party system turned out to be essential to the strength of the Republic. A stable party system organizes dissent. It turns discontent into a public good. And it insures the peaceful transfer of power, in which the losing party willingly, and without hesitation, surrenders its power to the winning party.

Jefferson delivered his inaugural address to Congress, assembled in the unfinished Capitol, but he addressed it to the American people: “Friends and Fellow Citizens.” It is one of the best inaugurals ever written. He spoke about “the contest of opinion,” a contest waged in the pages of the nation’s unruly newspapers. He tried to wave aside the bitter partisanship of the election and to defeat the spirit of intolerance manifest in the Sedition Act. “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle,” he said. “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.” Three weeks later, Jefferson wrote to Sam Adams: “The storm is over, and we are in port.”30

The storm was not over. One of the last and most important decisions John Adams made before leaving the presidency was to appoint to the office of chief justice the Virginian John Marshall, who was Jefferson’s cousin and also one of his fiercest political rivals. Federalists had lost power in the other two branches of government, but they seized it in the judicial branch and held it, a check against the suffrage of the people, a form of power more easily subject to abuse than any other.

A corrupt or too powerful judiciary had been one of the abuses that led to the Revolution. In 1768, Benjamin Franklin had listed judicial appointment as one of the “causes of American discontents,” and, in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson included the king’s having “made Judges dependent on his Will alone” on his list of grievances.31 “The judicial power ought to be distinct from both the legislative and executive, and independent,” John Adams had argued in 1776, “so that it may be a check upon both.”32 But a tension exists between judicial independence and the separation of powers. Appointing judges to serve for life would seem to establish judicial independence, but what power would then check the judiciary? Another solution was to have judges elected by the people—the people would then check the judiciary—but the popular election of judges would seem to make the courts subject to all manner of political caprice. At the constitutional convention, no one had argued that the Supreme Court justices ought to be popularly elected, not because the delegates were unconcerned about judicial independence but because there wasn’t a great deal of support for the popular election of anyone, including the president. And, although there was, for a time, some disagreement over whether the president or the Senate ought actually to do the appointing, the proposal that the president ought to appoint justices, and the Senate confirm them, and that these justices ought to hold their appointments “during good behavior,” was established swiftly, and without much dissent.33

Nevertheless, this arrangement had proved controversial during the debate over ratification. In an essay called “The Supreme Court: They Will Mould the Government into Almost Any Shape They Please,” one Anti-Federalist had pointed out that the power granted to the court was “unprecedented in a free country,” because its justices are, finally, answerable to no one: “No errors they may commit can be corrected by any power above them, if any such power there be, nor can they be removed from office for making ever so many erroneous adjudications.”34

This is among the reasons Hamilton had found it expedient, in Federalist 78, to emphasize the weakness of the judicial branch.35 When it began, the Supreme Court, without even a building to call its own, really was nearly as weak as Hamilton pretended it would be. It served, at first, as an appellate court and a trial court and, under the terms of the 1789 Judiciary Act, a circuit court. People thought it was a good idea for the justices to ride circuit, so that they’d know the citizenry better. The justices quite disliked riding circuit and, in 1792, petitioned the president to relieve them of the duty, writing, “we cannot reconcile ourselves to the idea of existing in exile from our families.” Washington, who had no children of his own, was unmoved.36 At one point, the chief justice, John Jay, wrote to Washington to let him know that he was going to skip the next session because his wife was having a baby (“I cannot prevail upon myself to be then at a Distance from her,” Jay wrote), and because there wasn’t much on the docket, anyway. In 1795, Jay resigned his appointment as chief justice to become governor of New York, closer to home. Washington then asked Hamilton to take his place; Hamilton said no, as did Patrick Henry. When the Senate rejected Washington’s next nominee for Jay’s replacement, the South Carolinian John Rutledge, Rutledge tried to drown himself near Charleston, crying out to his rescuers, “He had long been a Judge & he knew no Law that forbid a man to take away his own life.”37 The court, in short, was troubled.

Before leaving office, Adams had tried to reappoint Jay as chief justice, but Jay had refused, writing to the president, “I left the Bench perfectly convinced that under a system so defective, it would not obtain the energy, weight, and dignity which are essential to its affording due support to the national government, nor acquire the public confidence and respect which, as the last resort of the justice of the nation, it should possess.”38 All of this changed with John Marshall.

In 1801, when Marshall was appointed chief justice, the president lived in the President’s House, Congress met at the Capitol, and the court still lacked a home, having no building of its own. Marshall took his oath of office in a dank, dark, cold, “meanly furnished, very inconvenient” room in the basement of the Capitol, where the justices, who had no clerks, had no room to put on their robes or to deliberate. “The deaths of some of our most talented jurists,” one architect remarked, “have been attributed to the location of this Courtroom.” Cleverly, Marshall made sure all the justices rented rooms at the same boardinghouse, so that they could have someplace to talk together, unobserved.39

Nearly the very last thing Adams had done before leaving office was to persuade the lame-duck Federalist Congress to pass the 1801 Judiciary Act, reducing the number of Supreme Court Justices to five, a change slated to go into effect once the next vacancy came up. The only point of this chicanery was to make it so Jefferson wouldn’t have the chance to name a justice to the bench until two justices left. The next year, the newly elected Republican Congress repealed the 1801 act and, furthermore, suspended the next two sessions of the Supreme Court.

Sessions of Congress were open to the public and their deliberations were published, in accordance with what James Wilson had called, at the constitutional convention, the people’s “right to know.” But Marshall decided that the deliberations of the Supreme Court ought to be cloaked in secrecy. He also urged the justices to issue unanimous decisions—a single opinion, ideally written by the chief justice—and to destroy all evidence of disagreement.

Marshall’s critics considered these practices to be incompatible with a government accountable to the people. “The very idea of cooking up opinions in conclave begets suspicions,” Jefferson complained.40 But Marshall went ahead anyway. And, in 1803, in Marbury v. Madison, a suit against Jefferson’s secretary of state, James Madison, Marshall granted to the Supreme Court a power it had not been granted in the Constitution: the right to decide whether laws passed by Congress are constitutional.

Marshall declared: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.”41 One day, those words would be carved in marble; in 1803, they were very difficult to believe.

II.

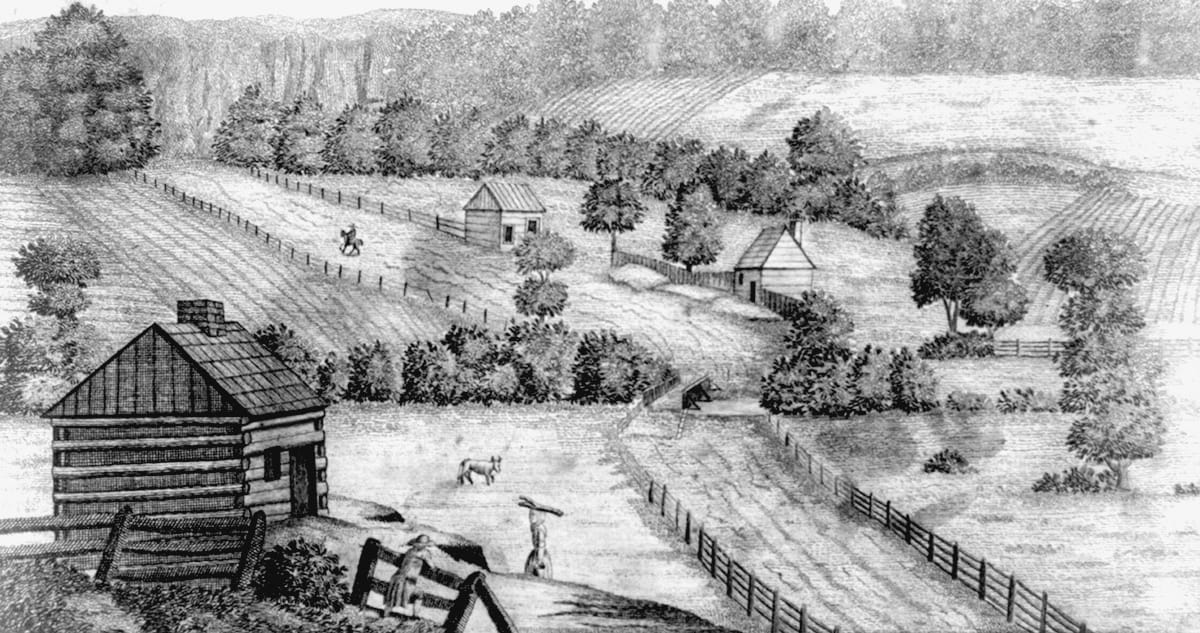

THE REPUBLIC WAS SPREADING like ferns on the floor of a forest. Between the first federal census and the second, the population of the United States increased from 3.9 to 5.3 million; by 1810, it was 7.2 million, having grown at the extraordinary rate of 35 percent every decade. By 1800, 500,000 people had moved from the eastern states to land along the Tennessee, Cumberland, and Ohio Rivers, portending a political shift to the West. Jefferson believed that the fate of the Republic lay in expansion: more land and more farmers. He believed that yeoman farmers, secure in their possessions and independent of the influence of other men, constituted the best citizens. “Dependence begets subservience and venality,” he wrote. There was something romantic, too, in Jefferson’s attachment to farming: “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God.” Influenced by Malthus, Jefferson believed that the new nation had to acquire more territory both to supply its growing population with food and to retain its republican character. Malthus postulated as a law of nature “the perpetual tendency in the race of man to increase beyond the means of subsistence.” In a growing population, poverty in man was as inevitable as old age.42 To this law, Thomas Jefferson expected the United States to prove an exception.

Convinced that the fate of the Republic turned on farming, Jefferson feared manufacturing and the rise of the factory. Workers in steam-powered factories in England, he thought, were the very opposite of the virtuous, independent citizens needed in a republic; they were dependent laborers, subservient and venal. Jefferson had a nail factory on his slave plantation, at Monticello, though it was small-scale, and what he hoped to avoid was the next stage of manufacturing, industrial production. But what he did not see, could not see, was that his fields were a factory, too, run not by machines but by the forced labor of more than a hundred enslaved human beings.

The first factories in the Western world weren’t in buildings housing machines powered by steam: they were out of doors, in the sugarcane fields of the West Indies, in the rice fields of the Carolinas, and in the tobacco fields of Virginia. Slavery was one kind of experiment, designed to save the cost of labor by turning human beings into machines. Another kind of experiment was the invention of machines powered by steam. These two experiments had a great deal in common. Both required a capital investment, and both depended on the regimentation of time.43 What separated them divided the American economy into two: an industrial North, and an agricultural South.

Jefferson’s presidency was a long battle over which of these systems ought to prevail, which meant looking to the West. The Louisiana Territory, nearly a million square miles west of the Mississippi, had been under Spanish rule since 1763, inhabited by Spaniards, Creoles, Africans, and Indians generally loyal to Great Britain. Spain allowed Americans to freely navigate the Mississippi and to ship goods from the vital port city of New Orleans, an arrangement that was essential for western settlement. But in 1800 Napoleon Bonaparte, who had seized control of France in 1799, secretly purchased the territory. He then attempted to reinstitute slavery on Saint-Domingue, which he hoped would serve as the economic heart of his New World empire. Napoleon’s troops captured and imprisoned Toussaint Louverture in 1802, but after war broke out between France and Britain the next year, Napoleon withdrew his forces from Saint-Domingue. The island’s former slaves declared their independence in 1803, establishing the Republic of Haiti. The United States refused to recognize Haiti but profited from its independence; without it, Napoleon no longer had much use for the Louisiana Territory and, at war with Britain, was keenly in need of funds. Jefferson and Madison arranged for their fellow Virginian, James Monroe, to travel to Paris to offer Napoleon $2 million for New Orleans and Florida (he was authorized to pay as much as $10 million). Unexpectedly, Napoleon offered to sell the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million. Monroe, seizing the opportunity, made the purchase. Its geographical and economic consequences were enormous: the size of the United States doubled.

But there were other consequences, too, both constitutional and political. The restoration of navigation rights along the Mississippi, and the use of the Port of New Orleans, were together a triumph. But under the Constitution, expenses have to be approved by the House and treaties by the Senate. Congress has the power to admit to the Union new states “established within the limits of the United States,” but it does not specifically have the power to acquire new territory that would be incorporated into the Union. Views on the matter fell along party lines. New England–dominated Federalists argued that Jefferson’s envoys had overstepped their authority and, further, that the purchase would make the Republic “too widely dispersed,” resulting, ultimately, in the “dissolution of the government.” Republicans argued that the purchase fell within the power to make treaties. Jefferson had no regrets about the purchase, but he did have qualms about its constitutionality. Since 1787, he’d argued for limiting the powers of the federal government; he believed that the Constitution would have to be amended before the treaty could be ratified. “I had rather ask an enlargement of power from the nation, where it is found necessary, than to assume it by a construction which would make our powers boundless.” If the Constitution were so broadly constructed that the power to make treaties could be read as a power to purchase land from another country, the Constitution, Jefferson thought, would have been made “a blank paper.” Yet, in the end, Jefferson deferred to his advisers, who argued against pursuing an amendment. Then, too, he thought this vast swath of territory might be “the means of tempting all our Indians on the East side of the Mississippi to remove to the West.”44

In 1804, after reading a revised edition of Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population, Jefferson concluded that “the greater part of his book is inapplicable to us” because of “the singular circumstance of the immense extent of rich and uncultivated lands in this country, furnishing an increase of food in the same ratio with that of population.” Malthus might have derived a law of nature, Jefferson conceded, but America provided an exception. “By enlarging the empire of liberty,” he wrote in 1805, “we . . . provide new sources of renovation, should its principles, in any time, degenerate, in those portions of our country, which gave them birth.”45

This scarcely settled the question. In 1806, Jefferson secured the passage of a Non-Importation Act, banning certain British imports and, in 1807, an Embargo Act, banning all American exports. During the ongoing war between Britain and France, the British had been seizing American ships and impressing American seamen. Jefferson believed that banning all trade was the only way to remain neutral. No Americans ships were to sail to foreign ports. He insisted that all the goods Americans needed they could produce in their own homes. “Every family in the country is a manufactory within itself, and is very generally able to make within itself all the stouter and middling stuffs for its own clothing and household use,” he wrote to Adams. “We consider a sheep for every person in the family as sufficient to clothe it, in addition to the cotton, hemp and flax which we raise ourselves.” Jefferson—blind to slavery—believed in an agrarian independence that required precise limits on economic activity: “Manufactures, sufficient for our own consumption, of what we raise the raw material (and no more). Commerce sufficient to carry the surplus produce of agriculture, beyond our own consumption, to a market for exchanging it for articles we cannot raise (and no more). These are the true limits of manufactures and commerce. To go beyond them is to increase our dependence on foreign nations, and our liability to war.”46

The embargo devastated the American economy. Jeffersonian agrarianism was not only backward-looking but also largely a fantasy. In 1793, when Jefferson first heard about the cotton gin, a machine that separates cotton fibers from the cotton bolls (“gin” is short for “engine”), he thought it would be excellent “for family use.” As late as 1815 he was boasting that, as a result of the embargo, “carding machines in every neighborhood, spinning machines in large families and wheels in the small, are too radically established ever to be relinquished.” That year, cotton and slave plantations in the American South were shipping seventeen million bales of cotton to England, to be carded and woven and spun in the coal- and-steam-powered mills in Lancaster and Manchester.47

Parliament abolished the slave trade in 1807; Congress followed in 1808, the first year that the trade could be ended, under the terms of the Constitution. But the cotton gin had by then made American slavery more profitable than ever. Congress repealed Jefferson’s embargo when he left office in 1809 (following the precedent established by Washington in not running for a third term), but New Englanders continued to press for the development of manufacturing. Congress therefore authorized a new kind of counting to be part of the next federal census, in 1810: an inventory of American manufacturing, overseen by Tench Coxe, former assistant secretary of the Treasury. In 1812, no longer able to stay neutral in the Napoleonic Wars, Congress narrowly approved the request by Jefferson’s successor, Madison, to declare war on Britain, the South supporting the declaration, and New England and the mid-Atlantic states mostly opposing it. It adversely affected northern manufacturing. It threatened an invasion from Canada. And it symbolized, to many Federalists, the daunting political dominance of the Republican Party. Not without cause, Federalists saw little distinction between the administrations of Jefferson and Madison, and would feel the same way about Madison’s successor, James Monroe, Virginians elected under the three-fifths clause.

Much of the fighting in what came to be called the War of 1812 took place at sea and in Canada. Britain successfully defended its possessions to the north. In 1813, the British captured the nation’s capital, Madison and his cabinet fled to Virginia, and, between the battle and a storm, the President’s House was all but destroyed. Three clerks at the War Office stuffed the original parchment Constitution of the United States into a linen sack and carried it to a gristmill in Virginia, which was a good idea, because the British burned the city down. Later, when someone asked James Madison where the Constitution had gone, he had not the least idea.48 After the war, the rebuilt President’s House was freshly painted—and became known as the White House.

The War of 1812 reminded northerners of the price the Republic had paid for the political calculation made in 1787. New Englanders hadn’t wanted to wage the war in the first place, and yet they found themselves powerless against the slave-owning states, grown mightier through the extension of slavery into newly acquired territories. By 1804, after the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory, Massachusetts and Connecticut had called for the abolition of the three-fifths clause. Their calls grew more shrill in 1812, after the New England author of a polemic titled Slave Representation damned the three-fifths clause as “the rotten part of the Constitution” and urged that it be “amputated.”49 Eyeing the inevitable ushering into the Union of new states, one writer from Massachusetts calculated that “one slave in Mississippi has nearly as much power in Congress, as five free men in the State of New-York.” Federalist fury reached a climax in 1814 at the Hartford Convention, where delegates from five New England states assembled in Connecticut to debate possible actions, including secession. Towns that had petitioned for the convention called for the end of slave representation. But three days after the convention sent its recommendation to the states, the last battle of the war began in New Orleans, where Andrew Jackson, a young general from Tennessee, led American troops to a stunning victory. The protest of New England was forgotten, the call to eradicate the three-fifths ratio ignored. On March 3, 1815, the last day Congress was in session, the resolutions of the Hartford Convention were read into the record and promptly tabled.50

The next day, at Monticello, Jefferson, seventy-two, pondered the future of the children he’d had with one of his slaves, a woman named Sally Hemings. Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles, had died in 1782, when Jefferson was thirty-eight. While she lay on her deathbed, he had promised her he would never remarry. Sally Hemings was the much younger half-sister of Jefferson’s wife; they had different mothers but the same father, John Wayles, who had six children with one of his slaves, a woman named Elizabeth Hemings, herself the child of an African woman and an English man. “The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submission on the other,” Jefferson wrote in 1782, the year of his wife’s death. “The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances.” In 1789, when sixteen-year-old Sally Hemings was working for and living in the residence of forty-six-year-old Jefferson in Paris, she became pregnant. She might have left him and gained her freedom; slavery was illegal in France. Instead, she extracted from him a promise, that if she stayed with him, he would set all of their children free.51

But he’d not quite managed to keep his children with Sally Hemings a secret. In 1800, printers had helped get Jefferson elected, but his view of them had grown dim over their scrutiny of his family life. (During his second term, an embittered Jefferson would suggest that newspapers ought to be divided into four sections: Truths, Probabilities, Possibilities, and Lies.)52 Only days after his inauguration, he’d complained that printers “live by the zeal they can kindle, and the schisms they can create.”53 James Callender, who’d gone to prison for sedition for campaigning for Jefferson, had wanted a political appointment. Jefferson having failed to reward him with a position, Callender in 1802 published an essay in the Richmond Recorder in which he reported on longstanding rumors that Jefferson had fathered children with one of his slaves. “Her name,” he wrote, “is SALLY.” And, had Callender been willing to publish the story of this scandal earlier, he said, “the establishment of this single fact would have rendered his election impossible.”54 Sally Hemings had had seven children by Jefferson, bearing her last in 1808. Jefferson, whose election had been made possible by the three-fifths clause, lived in a world that made the political calculation that his seven children with Sally were worth no more than four and two-tenths.

On March 4, 1815, the day after Congress tabled a resolution to abolish the three-fifths clause, haunted by the tragedy of his own and the nation’s malign political math, Jefferson attempted to calculate just how many generations would have to pass before a child with a full-blooded African ancestor could be called “white.” Under Virginia law—absurdity heaped upon absurdity—to be seven-eighths white was to be, legally, magically, white.

“Let us express the pure blood of the white in the capital letters of the printed alphabet,” Jefferson began, writing out his mathematical proof. “Let the first crossing be of a, a pure negro, with A, a pure white,” he went on. “The unit of blood of the issue being composed of the half of that of each parent, will be a/2 + A/2. Call it, for abbreviation, h (half blood).” This h was Elizabeth Hemings, Sally’s mother, the daughter of an Englishman, A, and an African woman, a. He labeled the second “pure white” B, a so-called quadroon, q, and the third “pure white” C. B was John Wayles, Sally’s father, and q, Sally herself. C was the third president of the United States. He concluded his proof:

Let the third crossing be of q and C, their offspring will be q/2 + C/2 = A/8 + B/4 + C/2, call this e (eighth), who having less than 1/4 of a, or of pure negro blood, to wit 1/8 only, is no longer a mulatto, so that a third cross clears the blood.55

To Jefferson, his children by Hemings were e, the third crossing, not black, because seven-eighths white: not three-fifths a person, but a whole.

Only four of Sally Hemings’s children lived to adulthood. She knew and they knew what Jefferson knew: if they left Monticello, they could pass for white, if they chose, reinventing themselves as citizens, making their own calculations, in a republic of blood.

OTHER MEN’S CONSCIENCES troubled them differently. In December 1816, a group of northern reformers and southern slave owners met in Washington at Davis’s Hotel for a meeting chaired by Henry Clay, the fast-talking Kentucky congressman and Speaker of the House. They’d gathered to discuss what to do about the nation’s growing number of free blacks. In 1790, there had been 59,467; by 1800, there were 108,398; in 1810, 186,446, to some a threatening multitude. The census made clear that the American population was growing at a rate never seen anywhere before, in the history of the world. Yet it made this much clear, too: the original thirteen eastern states were losing power, relative to the newer, western states. The institution of slavery, so far from dying the natural death predicted by the framers of the Constitution, was growing in the West, even as it was declining in the East. Two new states had lately entered the Union as free states: Ohio in 1803 and Indiana in 1816. Two more had entered as slave states: Louisiana in 1812 and Mississippi in 1816. But population growth in free states was outpacing that in slave states. And the population of free blacks was growing at a rate more than double that of the population of whites.

In Washington, the men who met in Davis’s Hotel decided upon a plan: they would found a colony in Africa, as Clay said, “to rid our country of a useless and pernicious, if not dangerous portion of its population.” They elected a president, Bushrod Washington, George Washington’s nephew and a Supreme Court justice. Andrew Jackson served as a vice president. They chose a name for their organization; they called it the American Colonization Society.56

By 1816, the divide between Republicans and Federalists had begun to align rather closely with the divide over the question of slavery. In his diary, John Quincy Adams, the son of the former president, who served as secretary of state for the new president, James Monroe, began calling the two parties the “slavery party” and the “free party.”57 Any extension of the Union threatened the balance between these two political forces. In 1819, Missouri, which had been settled by southerners, became the first part of the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi and north of the Ohio River to seek to enter the Union as a state. To the bill granting Missouri admission, James Tallmadge, a congressman from New York, introduced an amendment that would have banned slavery in the state. When one critic of the amendment said it would destroy the Union, Tallmadge replied, “Sir, if a dissolution of the Union must take place, let it be so!”58

The Tallmadge Amendment passed narrowly in the House but failed in the Senate. The debate that followed lasted more than two years. In wrestling with this question, members of Congress had the advantage of an extraordinary wealth of information about the population but suffered from a lack of historical perspective on the Constitution itself. The fifty-year vow of silence pledged by delegates to the constitutional convention—which prevented James Madison from publishing his Notes—meant that whatever logic there was to the three-fifths compromise was essentially unknowable. In November 1819, Madison, living in retirement in Virginia, answered a query about Missouri, explaining his view that the Constitution probably did not grant Congress the power to make the prohibition of slavery a condition of entering the Union and that, in any case, once Missouri became a state, it would have the right to institute slavery. For Madison, a member of the Colonization Society, the matter could be divided into a moral question, a matter of political arithmetic, and a constitutional one, a matter of law.

“Will it or will it not better the condition of the slaves, by lessening the number belonging to individual masters, and intermixing both with greater masses of free people?” Madison asked. “Will the aggregate strength, security, tranquility and harmony of the whole nation be advanced or impaired by lessening the proportion of slaves to the free people in particular sections of it?”59

Tallmadge and his supporters condemned the politics of slavery, assailing the injustice of slave representation, and insisted that whatever bargain had been made at the constitutional convention need not extend into states that had not existed in 1787. Their opponents, instead of defending slavery, insisted on the impracticability of emancipation by arguing that black people would never be able to live among white people as equals. “There is no place for the free blacks in the United States—no place where they are not degraded,” one argued. “If there was such a place, the society for colonizing them would not have been formed.”60 Behind Madison’s remarks about “lessening the proportion of slaves to the free people,” behind Jefferson’s tortured calculations about how many generations would have to pass before his own children could pass for “white,” lay this hard truth: none of these men could imagine living with descendants of Africans as political equals.

And yet Jefferson made good on his promise to Sally Hemings. His two oldest children with Sally, Beverly and Harriet, left Monticello, apparently with his approval. “Harriet. Sally’s run,” Jefferson wrote in 1822 in his “Farm Book,” where he kept track of his human property. Harriet Hemings hadn’t run. She was twenty-one, and Jefferson had set her free. “She was nearly as white as anybody, and very beautiful,” recalled one of Jefferson’s overseers, who also said that Jefferson ordered him to give fifty dollars to Harriet, and had paid for her ride, by stage, to Philadelphia. From there she traveled on to Washington, where her brother Beverly had already settled. “She thought it to her interest, on going to Washington, to assume the role of a white woman,” said Harriet’s brother Madison, the only one of Sally Hemings’s children to live his life as a black man. He seems never to have forgiven his sister. But he kept her secret. “I am not aware that her identity as Harriet Hemings of Monticello has ever been discovered,” he said. “Harriet married a white man in good standing in Washington City, whose name I could give,” he said, “but will not.”61

On the floor of Congress, men pounded on their desks, and they rose to make speeches, and they listened, intently or indifferently. Into the stale air of the room wafted another proposal. Southerners like Henry Clay and John Tyler began to make a mathematical argument about “diffusion”: if slavery were allowed in states like Missouri, people who wanted to own slaves would have to buy them from states like Virginia, and then slavery as an institution would grow in the West, but the number of slaves would be small. Meanwhile, the number of slaves in the East would continue to decline, and in both places the ratio of slaves to white people would be low, which, it was expected, would make the condition of slaves better, and would lessen the likelihood that they would have children with whites. Might the blood of the nation be cleared?

“Diffusion is about as effectual a remedy for slavery as it would be for smallpox,” scoffed a Baltimore attorney named Daniel Raymond, in a thirty-nine-page pamphlet called The Missouri Question. Raymond was a member of the American Colonization Society, but, he argued, the idea “that the Colonization Society can under any circumstances, have any perceptible effect in eradicating slaves from our soil, is utterly chimerical.” It was a matter of Malthusianism: “as population increases in a geometrical ratio, it is utterly impossible by that means, to make any perceptible diminution of the number of blacks in our country. On the contrary, the curse of slavery will continue to increase and that in a geometrical ratio too, in spite of the utmost efforts of the Society.” Slavery would not simply disappear, Raymond insisted: “It is an axiom as true as the first problem in Euclid, that if left to itself it will every year become more inveterate and more formidable.”62

Southerners attacked Raymond on the floor of the Senate. Among other things, they pointed out that a moral objection that was geographically bounded—those who opposed slavery in the West promised they would leave it alone in the South—was hardly a deeply held conviction. Virginia senator James Barbour asked, “What kind of ethics is that which is bounded by latitude and longitude, which is inoperative on the left, but is omnipotent on the right bank of a river?” But Raymond’s math, at any rate, turned out to be right. Calculating the growth of the slave population based on its known rate of increase, Raymond predicted that the number of slaves in the United States, less than 900,000 in 1800, would be 1.9 million by 1830. He was very close; it would be 2 million.63

Month after month of pencil to paper, adding and subtracting, multiplying and dividing, did not settle the matter of the ratio of white people to black people in the United States. Nor did the colonization scheme. (Only about three thousand African Americans ever left for Liberia.) The Missouri question was settled, more or less, by accident. In 1820, Maine, which had been part of Massachusetts, petitioned to be admitted to the Union as a free state. Alabama had been admitted to the Union the summer before, as a slave state, making the number of free and slave states equal, at twelve each. Congress, eager to end the impasse over Missouri, devised a compromise that would retain the balance between slave and free states. Under the Missouri Compromise, a deal deftly brokered by Clay, ever after known as “the Great Compromiser,” Missouri was admitted as a slave state and Maine as a free state, and a line was set at 36˚30' latitude, the southern border of Missouri: any states formed out of territories above that line would enter the Union as free states, and any states below that line would enter as slave states. The three-fifths clause survived. But John Quincy Adams did not believe it would survive for long. “Take it for granted that the present is a mere preamble—a title page to a great, tragic volume,” he wrote in his diary. “The President thinks this question will be winked away by a compromise. But so do not I. Much am I mistaken if it is not destined to survive his political and individual life and mine.”64 He was not mistaken.

III.

THE FIRST FIVE PRESIDENTS of the United States, Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, were diplomats, soldiers, philosophers, and statesmen, founders of the nation. Even Monroe, the youngest of the five men, and the least distinguished of them, had fought in the Revolutionary War and served in the Continental Congress. But by 1824, that generation had passed. John Quincy Adams had been intended—at least by his father—as their successor, groomed, from childhood, for the presidency. “You come into life with advantages which will disgrace you if your successes are mediocre,” John Adams told him. “And if you do not rise . . . to the head of your country, it will be owing to your own Laziness, Slovenliness, and Obstinancy.”65

John Quincy Adams was hardly a shirker. He’d begun keeping a diary in 1779, when he was twelve and on a diplomatic mission to Europe with his father. After finishing his studies and passing the bar, he’d served as Washington’s minister to the Netherlands and Portugal, as his father’s minister to Prussia, and as Madison’s minister to Russia. He spoke fourteen languages. As secretary of state, he’d drafted the Monroe Doctrine, establishing the principle that the United States would keep out of wars in Europe but would consider any European colonial ventures in the Americas as acts of aggression. By the time he decided to seek the presidency, he’d also served as a U.S. senator and as a professor of logic at Brown and professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard.

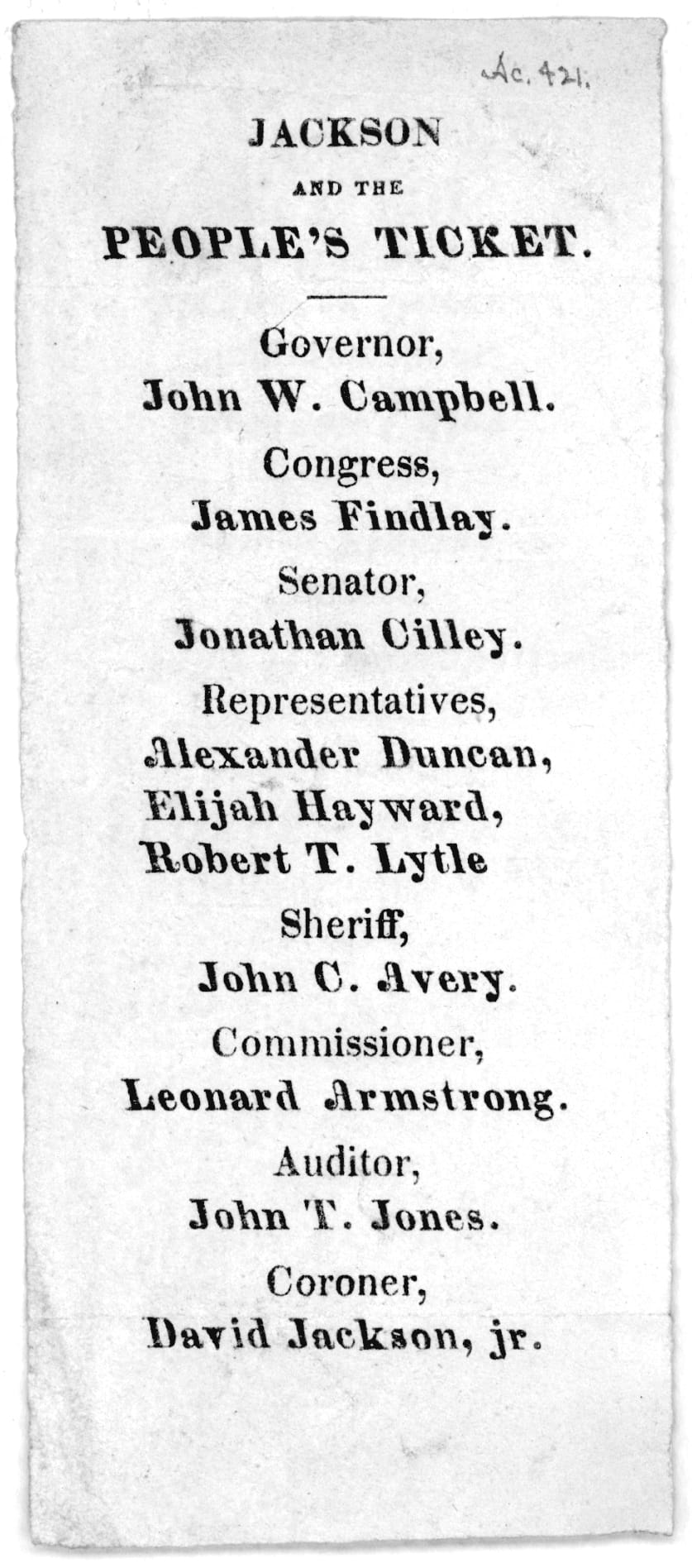

In 1824, it was said that American voters faced a choice between “John Quincy Adams, / Who can write / And Andrew Jackson, / Who can fight.”66 If the battle between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson had determined whether aristocracy or republicanism would prevail (and, with Jefferson, republicanism won), the battle between Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams would determine whether republicanism or democracy would prevail (and, with Jackson, democracy would, eventually, win). Jackson’s rise to power marked the birth of American populism. The argument of populism is that the best government is that most closely directed by a popular majority. Populism is an argument about the people, but, at heart, it is an argument about numbers.67

A national hero after the Battle of New Orleans, Jackson had gone on to lead campaigns against the Seminoles, the Chickasaws, and the Choctaws, pursuing a mixed strategy of treaty-making and war-making, with far more of the latter than the former, as part of a plan to remove all Indians living in the southeastern United States to lands to the west. He was provincial, and poorly educated. (Later, when Harvard gave Jackson an honorary doctorate, John Quincy Adams refused to attend the ceremony, calling him “a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and hardly could spell his own name.”)68 He had a well-earned reputation for being ferocious, ill-humored, and murderous, on the battlefield and off. When he ran for president, he had served less than a year in the Senate. Of his bid for the White House Jefferson declared, “He is one of the most unfit men I know of for such a place.”69

Jackson made a devilishly shrewd decision. He would make his lack of certain qualities—judiciousness, education, political experience—into strengths. He would run as a hot-tempered military man who’d pulled himself up by his own bootstraps. To do this, he needed to tell the story of his life. Within weeks of his victory at the Battle of New Orleans, in preparation for a political career, he hired a biographer, sixty-five-year-old David Ramsay, a South Carolina legislator and physician and gifted historian whose books included a two-volume History of the American Revolution (1789) and a heroic Life of George Washington (1807). But before Ramsay could begin work on the biography, he was shot in the back on the streets of Charleston. Jackson hired his aide-de-camp John Reid, who drafted four chapters before he, too, died an unfortunate and unexpected death. “The book must be finished,” Jackson insisted. He turned, next, to a twenty-six-year-old lawyer named John Eaton who had served under Jackson during the Creek War and the War of 1812; Eaton was Jackson’s “bosom friend and adopted son,” according to Margaret Bayard Smith, a novelist and remarkably astute observer of Washington society and politics. (Her husband, Samuel Harrison Smith, was a president of the Bank of the United States.) Eaton’s Life of Andrew Jackson appeared in 1817. The next year, Eaton was elected to the Senate, and in 1823, when Jackson joined him in Washington, the two senators from Tennessee shared lodgings.70

Andrew Jackson, man of the people, was the first presidential candidate to campaign for the office, the first to appear on campaign buttons, and nearly the first to publish a campaign biography. In 1824, when Jackson announced his bid for the presidency, Eaton, who ran Jackson’s campaign, shrewdly revised his Life of Andrew Jackson, deleting or dismissing everything in Jackson’s past that looked bad and lavishing attention on anything that looked good and turning into strengths what earlier had been considered weaknesses: Eaton’s Jackson wasn’t uneducated; he was self-taught. He wasn’t ill-bred; he was “self-made.”71

The election of 1824 also altered the very method of electing a president. Why should a party’s nominee be selected by a caucus in Congress? The legislative caucus worked only so long as voters didn’t mind that they had virtually no role in electing the president.72 Calls for the beheading of “King Caucus” had begun in 1822, when the New York American asked: “Why should not a general convention of Republican delegates from the different states assemble at Washington a few months prior to the period for electing a President and decide, by a majority, the choice of an individual for that elevated office”? Two years later, popular opposition to the caucus had grown. After word got out to the press about a caucus meeting to be held in the House, only 6 out of 240 legislators were willing to appear before a disgruntled public, which flooded the galleries shouting, “Adjourn! Adjourn!” And so it did.73

With the caucus dead, John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay simply declared their candidacies. Jackson looked for a popular mandate: he was nominated by the Tennessee legislature. The momentum behind Jackson’s candidacy drew, as well, on the power of newly enfranchised voters. When new states entered the Union, they held conventions to draft and ratify their own state constitutions: they almost always adopted more democratic arrangements than those that prevailed in the thirteen original states. They abolished property requirements for voting, replaced judicial appointment with judicial elections, and provided for the popular election of delegates to the Electoral College. The new and more democratic state constitutions put pressure on older states to revise their own constitutions. By 1821, property qualifications for voting no longer existed in twenty-one out of twenty-four states. Three years later, eighteen out of twenty-four states held popular elections for delegates to the Electoral College. More and poorer white men came to the polls and were elected to office, much to the dismay of conservatives like Chancellor James Kent of New York who, at New York’s 1821 constitutional convention, complained, “The notion that every man that works a day on the road, or serves an idle hour in the militia, is entitled as of right to an equal participation in the whole power of government, is most unreasonable and has no foundation in justice.” He believed in proportionate representation—representation proportionate to wealth: “Society is an association for the protection of property as well as of life, and the individual who contributes only one cent to the common stock, ought not to have the same power and influence in directing the property concerns of the partnership, as he who contributes his thousands.”74

As the kind of people who could vote changed, so did the method of voting. Early paper voting had been unwieldy and inconvenient; voters were expected to bring to the polls a scrap of paper on which they could write the names of their chosen candidates. With the electorate expanding, this system became even more impractical. Party leaders began to print ballots, usually in partisan newspapers, usually in long strips, listing an entire slate as a “party ticket.” The ticket system consolidated the power of the parties and contributed to the expansion of the electorate: party tickets meant that voters didn’t need to know how to write or even how to read; each party ticket was printed on a different color paper, and each was stamped with a party symbol.

In 1824, Jackson won both the popular vote and a plurality, though not a majority, of the electoral vote. The election was thrown to the House, which chose John Quincy Adams after Henry Clay threw his support behind him. Adams then appointed Clay his secretary of state. Jefferson wrote to John Adams to congratulate him on his son’s election. Having retired from politics, the two men had renewed the friendship of their youth. “Every line from you exhilarates my spirits,” Adams replied.75

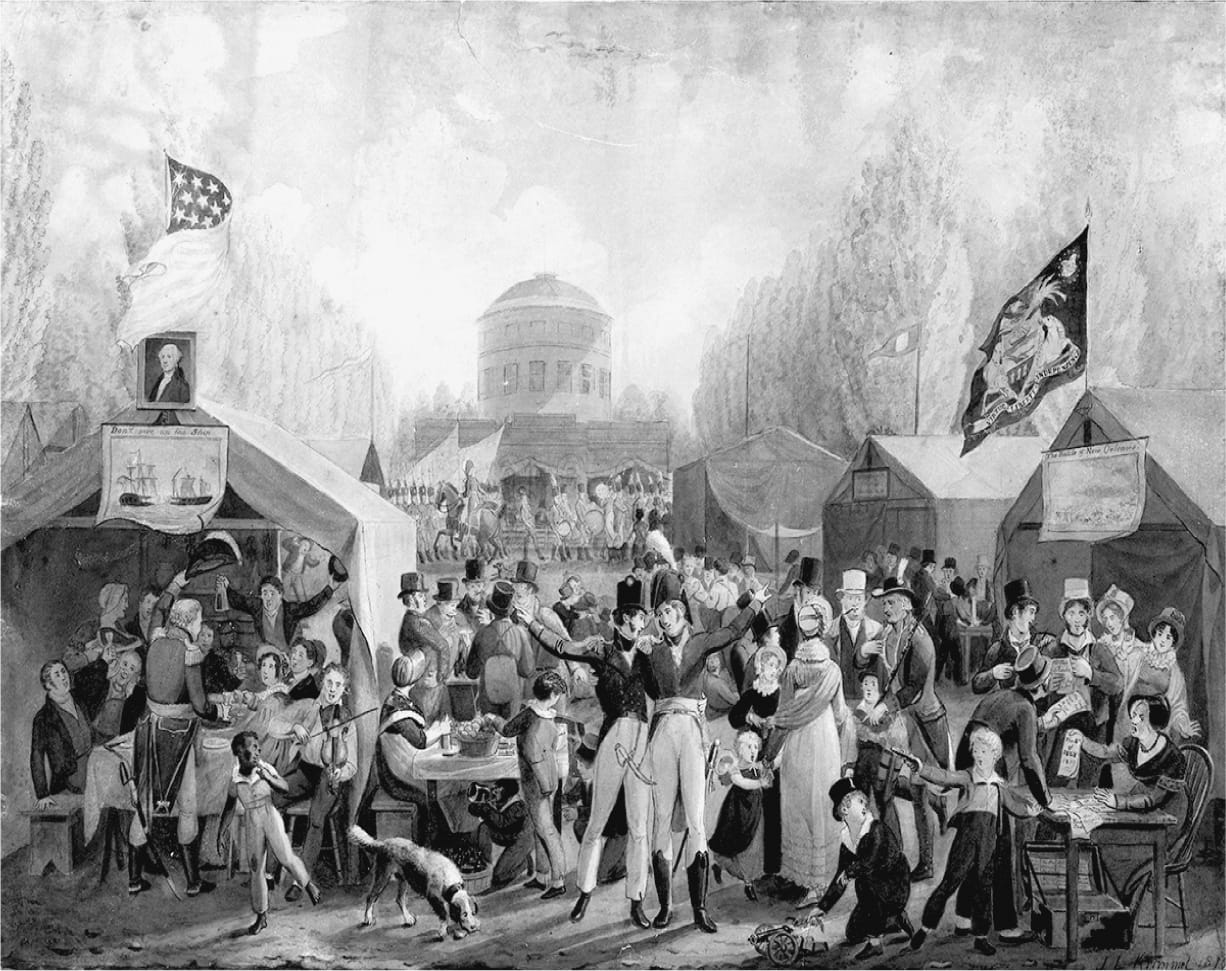

Jackson, furious at what he deemed a “corrupt bargain,” resigned from the Senate in 1825, returned to the Hermitage, and bided his time while the electorate swelled. Between 1824 and 1828, it more than doubled, growing from 400,000 to 1.1 million. Men who had attended the constitutional convention in 1787 shook their gray-haired heads and warned that Americans had crowned a new monarch, King Numbers.76

ON JULY 4, 1826, the United States celebrated its jubilee, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. In cities and towns, Americans paraded and sang and raised glasses and listened to speeches. Many of those speeches celebrated the new spirit of democracy, the defeat of the contempt for the people that had been part of the nation’s founding. “There may be those who scoff at the suggestion that the decision of the whole is to be preferred to the judgment of the enlightened few,” said the historian George Bancroft, speaking in Boston. “They say in their hearts that the masses are ignorant; that farmers know nothing of legislation; that mechanics should not quit their workshops to join in forming public opinion. But true political science does indeed venerate the masses.” The voice of the people, Bancroft insisted, “is the voice of God.”77

Nothing more clearly marked the end of the founding era than the coincidence of the deaths of two men, on that very day: Thomas Jefferson, the pen of the Declaration, and John Adams, the voice of independence. Adams, ninety, died at his home in Massachusetts. “He breathed his last about 6 o’clock in the afternoon,” reported one newspaper, “while millions of his fellow-countrymen were engaged in festive rejoicings at the nation’s jubilee, and in chanting praises to the immortal patriots whose valour and virtue accomplished their country’s freedom and independence.”78 He had been declining for years. He’d lost his teeth and his eyesight. He slept in an overstuffed armchair in his library, in a dressing coat and a cotton cap, surrounded by his books; he left them, in his will, to his son John Quincy. Cannons fired on the Fourth were nearly drowned out by the sound of thunder, an afternoon storm. Having been carried to his bed, Adams stirred and whispered, “Thomas Jefferson survives.” At twenty past six, he died. But in Virginia, Jefferson, eighty-three, had died at ten minutes before one.

In a will that Jefferson had made months before, he’d freed the last two of his children with Sally Hemings, Madison and Eston; he did not mention Sally. Invited to celebrate the Fourth of July in Washington, Jefferson had instead sent a letter of regret, and words upon the day, celebrating this self-evident truth: “the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few, booted and spurred, ready to ride them.” He was dying. Suffering and in pain, he’d been dosed with laudanum. He’d slept through most of July 2 and July 3 and then refused the medicine. He died on the Fourth, while the bells in nearby Charlottesville tolled the anniversary of American independence.

Sally Hemings’s brother John built Jefferson’s coffin. Six months later, to pay his debts, Jefferson’s entire estate, including 130 slaves, was sold at an auction. The Fossett children, cousins of Sally Hemings’s, were among the “130 VALUABLE NEGROES” sold to the highest bidder.79 Hemings, fifty-three years old, was appraised at fifty dollars, but she was not sold at auction; she had, by then, quietly left Monticello for Charlottesville, where she lived until her death. From Monticello, she brought with her a pair of Jefferson’s eyeglasses to remember him by—a man of sight, and of blindness.80

Their daughter Harriet Hemings was twenty-seven and still living in Washington in 1828 when Andrew Jackson finally defeated John Quincy Adams, in an election that marked the founding of the Democratic Party, Jackson’s party, the party of the common man, the farmer, the artisan: the people’s party.

Jackson won a whopping 56 percent of the popular vote. Four times as many white men cast a ballot in 1828 as in 1824. They voted in throngs. They voted by casting ballots, not balls but slips of paper: Jackson tickets, with which they cast their votes for Jackson delegates to the Electoral College, and for an entire slate of Democratic Party candidates. The majority ruled. Watching the rise of American democracy, an aging political elite despaired, and feared that the Republic could not survive the rule of the people. Wrote John Randolph of Virginia, “The country is ruined past redemption.”81

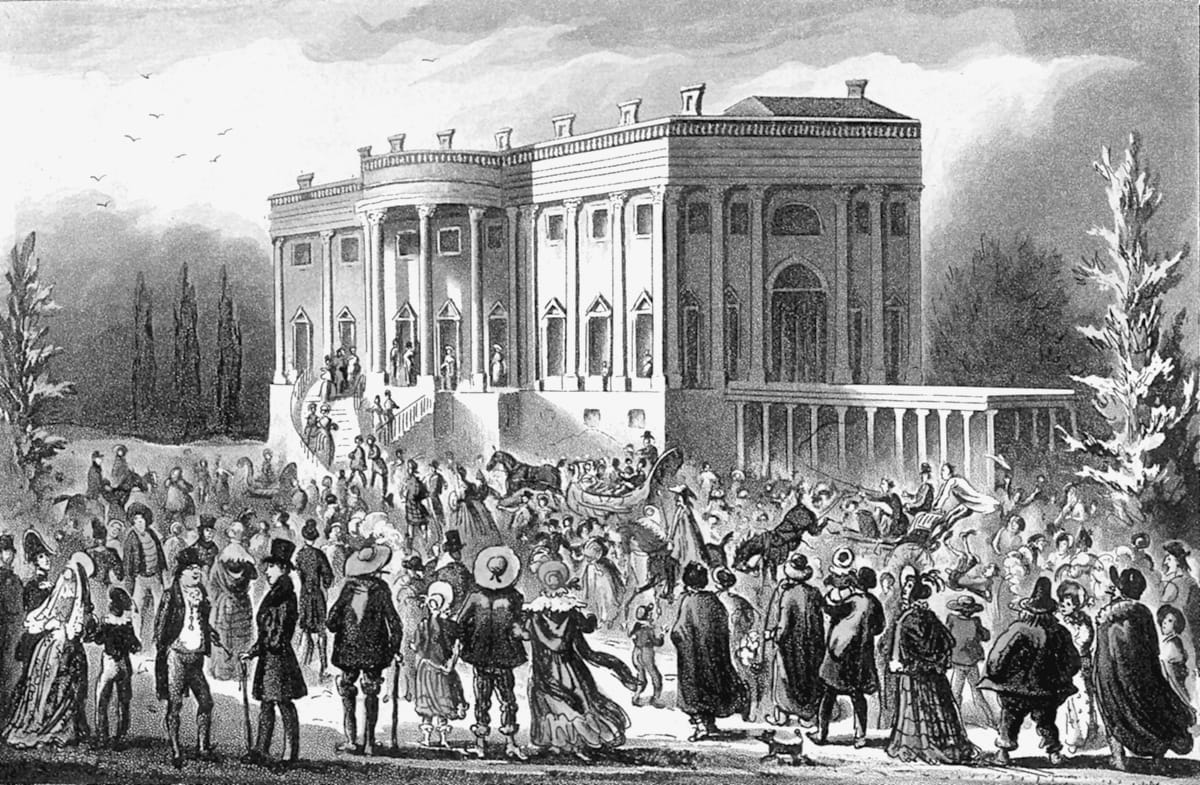

On a mild winter’s day, March 4, 1829, twenty thousand Americans turned up in Washington for Andrew Jackson’s unruly inauguration. Steamboats from Alexandria offered discounted passage across the Potomac.82 “Thousands and thousands of people, without distinction of rank, collected in an immense mass round the Capitol,” wrote Margaret Bayard Smith. Jackson was the first president to deliver his inaugural address to the American people. Following the practice established by Jefferson, he walked to the Capitol instead of riding. Harriet Hemings might have watched, from a sidewalk.

John Marshall administered the oath of office. Margaret Bayard Smith said that when Jackson began to speak, “an almost breathless silence, succeeded and the multitude was still, listening to catch the sound of his voice.”

His voice rising, he celebrated the triumph of numbers. “The first principle of our system,” Jackson said, “is that the majority is to govern.” He bowed to the people. Then, all at once, the people nearly crushed him with their affection. “It was with difficulty he made his way through the Capitol and down the hill to the gateway that opens on the avenue,” Smith reported. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story attended the swearing-in and then left, bemoaning “the reign of KING MOB.”83

Even after the president mounted a horse, the people followed him. “Country men, farmers, gentlemen, mounted and dismounted, boys, women and children, black and white,” Smith wrote. “Carriages, wagons and carts all pursuing him to the President’s house.” They followed Jackson from the steps of the Capitol all the way to the White House, where, for the first time, the doors were opened to the public. A “rabble, a mob, of boys, negros, women, children, scrambling fighting, romping,” wrote Smith. “Ladies fainted, men were seen with bloody noses and such a scene of confusion took place as is impossible to describe,—those who got in could not get out by the door again, but had to scramble out of windows.” There was a real worry that the people might press the president to death before the day came to an end. “But it was the People’s day,” she wrote, “and the People’s President and the People would rule.”84 The rule of numbers had begun.