Six

THE SOUL AND THE MACHINE

MARIA W. STEWART, DARK AND BEAUTIFUL, CARRIED A manuscript tucked under her arm as she picked her way through the cobbled streets of Boston to the offices of the Liberator, at 11 Merchants’ Hall, down by the docks. “Our souls are fired with the same love of liberty and independence with which your souls are fired,” she’d written in an essay she hoped to publish. The descendant of slaves, she’d been born free, in Connecticut, in 1803. Orphaned at five, she’d been bound as a servant to a clergyman till she turned fifteen. In August of 1826, weeks after the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, she’d married a much older man: she was twenty-three; her husband, James W. Stewart, described as “a tolerably stout well-built man; a light, bright mulatto,” had served as a sailor during the War of 1812; captured, he’d been a prisoner of war. “It is the blood of our fathers, and the tears of our brethren that have enriched your soils,” Maria Stewart wrote in her first, revolutionary essay about American history. “AND WE CLAIM OUR RIGHTS.”1

William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the Liberator, was two years younger than Stewart. He’d apprenticed as a typesetter and worked as a printer and an editor and failed, again and again, before founding his most radical newspaper. A thin, balding white man, he slept on a bed on the floor of his cramped office, a printing press in the corner; he kept a cat to catch rats. Stewart told Garrison she wished to write for his newspaper, to say what she thought needed saying to the American people. Impressed with her “intelligence and excellence of character,” he later recalled, he published the first of her essays in 1831 in a column called the Ladies’ Department. “This is the land of freedom,” Stewart wrote. “Every man has a right to express his opinion.” And every woman, too. She asked, “How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?”2

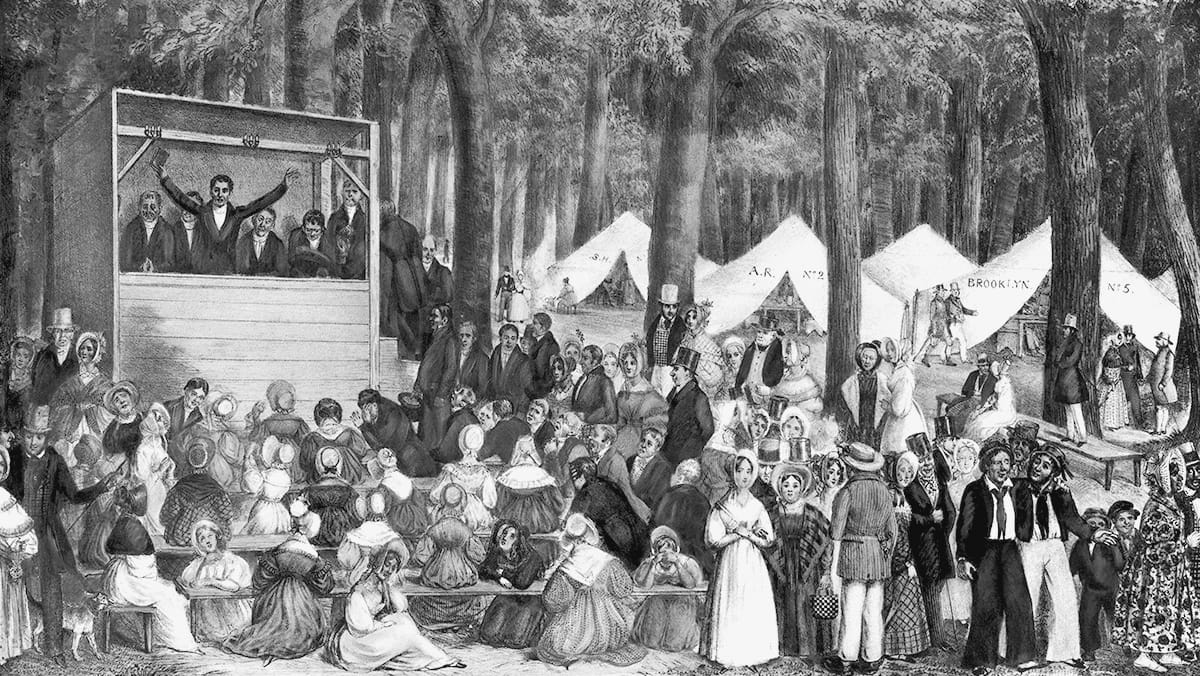

Stewart was a born-again Christian, caught up in a religious revival that swept the country and reached its height in the 1820s and 1830s in the factory towns that grew like kudzu along the path cut by the Erie Canal, from the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, where the power of steam and the anxiety of industrialization were answered by the power of Christ and the assurance of the Gospel. Before the revival began, a scant one in ten Americans were church members; by the time it ended, that ratio had risen to eight in ten.3 The Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher called it “the greatest work of God, and the greatest revival of religion, that the world has ever seen.”4

The revival, known as the Second Great Awakening, infused American politics with the zealotry of millennialism: its most ardent converts believed that they were on the verge of eliminating sin from the world, which would make possible the Second Coming of Christ, who was expected to arrive in as short a time as three months and to come, not to the holy lands, to Bethlehem or Jerusalem, but to the industrializing United States, to Cincinnati and Chicago, to Detroit and Utica. Its ministers preached the power of the people, offering a kind of spiritual Jacksonianism. “God has made man a moral free agent,” said the thundering, six-foot-three firebrand Charles Grandison Finney.5 And the revival was revolutionary: by emphasizing spiritual equality, it strengthened protests against slavery and against the political inequality of women.

“It is not the color of the skin that makes the man or the woman,” wrote Stewart, “but the principle formed in the soul.”6 The democratization of American politics was hastened by revivalists like Stewart who believed in the salvation of the individual through good works and in the equality of all people in the eyes of God. Against that belief stood the stark and brutal realities of an industrializing age, the grinding of souls.

I.

THE UNITED STATES was born as a republic and grew into a democracy, and, as it did, it split in two, unable to reconcile its system of government with the institution of slavery. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, democracy came to be celebrated; the right of a majority to govern became dogmatic; and the right to vote was extended to all white men, developments much derided by conservatives who warned that the rule of numbers would destroy the Republic. By the 1830s, the American experiment had produced the first large-scale popular democracy in the history of the world, a politics expressed in campaigns and parades, rallies and conventions, with a two-party system run by partisan newspapers and an electorate educated in a new system of publicly funded schools.

The great debates of the middle decades of the nineteenth century had to do with the soul and the machine. One debate merged religion and politics. What were the political consequences of the idea of the equality of souls? Could the soul of America be redeemed from the nation’s original sin, the Constitution’s sanctioning of slavery? Another debate merged politics and technology. Could the nation’s new democratic traditions survive in the age of the factory, the railroad, and the telegraph? If all events in time can be explained by earlier events in time, if history is a line, and not a circle, then the course of events—change over time—is governed by a set of laws, like the laws of physics, and driven by a force, like gravity. What is that force? Is change driven by God, by people, or by machines? Is progress the progress of Pilgrim’s Progress, John Bunyan’s 1678 allegory—the journey of a Christian from sin to salvation? Is progress the extension of suffrage, the spread of democracy? Or is progress invention, the invention of new machines?

A distinctively American idea of progress involved geography as destiny, picturing improvement as change not only over time but also over space. In 1824, Jefferson wrote that a traveler crossing the continent from west to east would be conducting a “survey, in time, of the progress of man from the infancy of creation to the present day,” since “in his progress he would meet the gradual shades of improving man.” His traveler—a surveyor, at once, of time and space—would begin with “the savages of the Rocky Mountains”: “These he would observe in the earliest stage of association living under no law but that of nature, subscribing and covering themselves with the flesh and skins of wild beasts.” Moving eastward, Jefferson’s imaginary traveler would then stop “on our frontiers,” where he’d find savages “in the pastoral state, raising domestic animals to supply the defects of hunting.” Next, farther east, he’d meet “our own semi-barbarous citizens, the pioneers of the advance of civilization.” Finally, he’d reach the seaport towns of the Atlantic, finding man in his “as yet, most improved state.”7

Maria Stewart’s Christianity stipulated the spiritual equality of all souls, but Jefferson’s notion of progress was hierarchical. That hierarchy, in Jackson’s era, was the logic behind African colonization, and it was also the logic behind a federal government policy known as Indian removal: native peoples living east of the Mississippi were required to settle in lands to the west. A picture of progress as the stages from “barbarism” to “civilization”—stages that could be traced on a map of the American continent—competed with a picture of progress as an unending chain of machines.

The age of the machine had begun in 1769, in Glasgow, when James Watt patented an improvement on the steam engine. People had tapped into natural sources of power for manufacturing before—with waterwheels and windmills—but Watt’s models produced five times the power of a waterwheel, and didn’t need to be sited on a river: a steam engine could work anywhere. Watt reckoned the power of a horse at ten times the power of a man; he defined one “horse power” as the energy required to lift 550 pounds by one foot in one second. Powered by steam, manufacturing became, in the nineteenth century, two hundred times more efficient than it had been in the eighteenth century. That this invention would eventually upend political arrangements is prefigured in a likely apocryphal story told at the time about Watt and the king of England. When King George III went to a factory to see Watt’s engine at work, he was told that the factory was “manufacturing an article of which kings were fond.”8

What article is that, he asked? The reply: Power.

There followed machine upon machine, steam-driven looms, steam-driven boats, making for faster production, faster travel, and cheaper goods. Steam-powered industrial production altered the economy, and it also altered social relations, especially between men and women and between the rich and the poor. The anxiety and social dislocation produced by those changes fueled the revival of religion. Everywhere, the flame of revival burned brightest in factory towns.

Before the rise of the factory, home and work weren’t separate places. Most people lived on farms, where both men and women worked in the fields. In the winter, women spent most of their time carding, spinning and weaving wool, sheared from sheep. In towns and cities, shopkeepers and the masters of artisanal trades—bakers, tailors, printers, shoemakers—lived in their shops, where they also usually made their goods. They shared this living space with journeymen and apprentices. Artisans made things whole, undertaking each step in the process of manufacturing: a baker baked a loaf, a tailor stitched a suit. With the rise of the factory came the division of labor into steps done by different workers.9 With steam power, not only were the steps in the manufacturing process divided, but much of the labor was done by machines, which came to be known as “mechanical slaves.”10

New, steam-powered machines could also spin and weave—and even weave in ornate, multicolored patterns. In 1802, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, a French weaver, invented an automated loom. By feeding into his loom stiff paper cards with holes punched in them, he could instruct it to weave in any pattern he liked. Two decades later, the English mathematician Charles Babbage used Jacquard’s method to devise a machine that could “compute”; that is, it could make mathematical calculations. He called it the Difference Engine, a giant mechanical hand-cranked calculating machine that could tabulate any polynomial function. Then he invented another machine—he called it the Analytical Engine—that could apply the act of mechanical tabulation to solve any problem that involved logic. Babbage never built a working machine, but Ada Lovelace, a mathematician and the daughter of Lord Byron, later prepared a detailed description and analysis of the principles and promises of Babbage’s work, the first account of what would become, in the twentieth century, a general-purpose computer.11

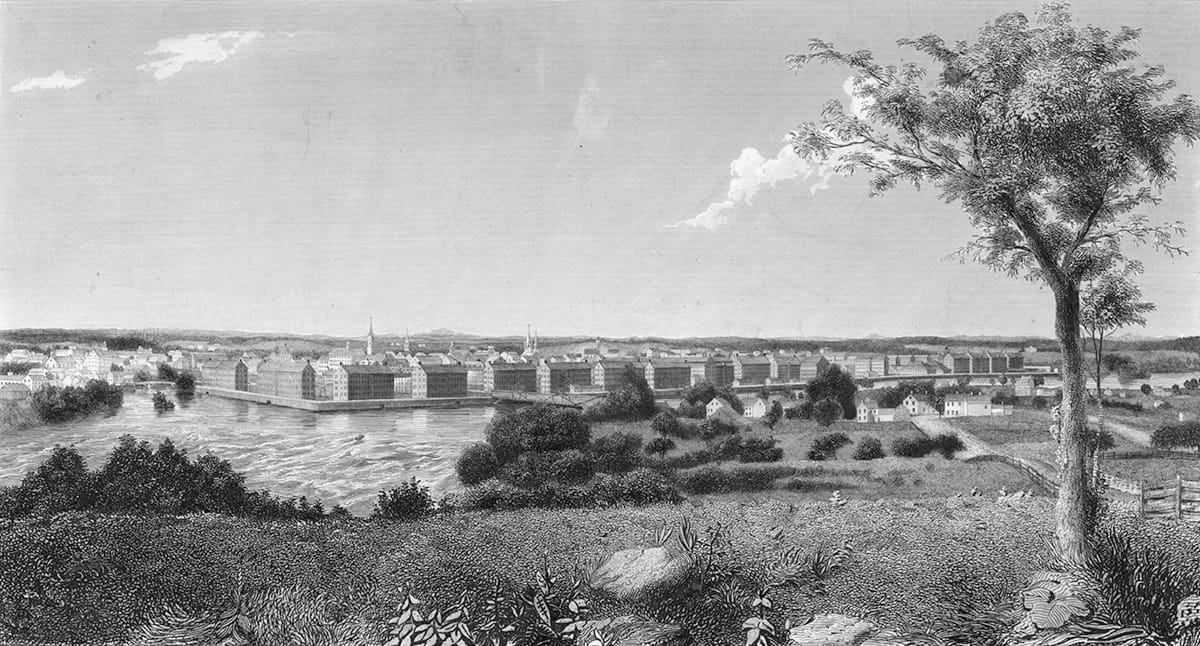

In the United States, with its democracy of numbers, a calculating computer, a machine that could count, would one day throw a wrench in the machinery of government. But long before that day came, Americans devised simpler machines. Watt jealously guarded his patents. In 1810, an American merchant named Francis Cabot Lowell toured England’s textile mills and made sketches from memory. In New England, working from those sketches, he designed his own machines and began raising money to build his own factory. Lowell died in 1817. His successors opened the Lowell mills on the Merrimack River in 1823. Every step, from carding to cloth, was done in the same set of factories: six brick buildings erected around a central clock tower. Inspired by the social reformer Robert Owen, Lowell had meant his system as a model, an alternative to the harsh conditions found in factories in England. He called it “a philanthropic manufacturing college.” The Lowell mill owners hired young women, transplants from New England farms. They worked twelve hours a day and attended lectures in the evening; they published a monthly magazine. But the utopia that Francis Cabot Lowell imagined did not last. By the 1830s, mill owners had cut wages and sped up the pace of work, and when women protested, they were replaced by men.12

Factories accelerated production, canals acceleration transportation. The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, took eight years to dig and covered 360 miles. Before the canal, the wagon trip from Buffalo to New York City took twenty days; on the canal, it took six. The price of goods plummeted; the standard of living soared. A mattress that cost fifty dollars in 1815, which meant that almost no one owned one, cost only five dollars in 1848.13 One stop on the Erie Canal was Rochester, a mill town on the shore of Lake Ontario that processed the grain from surrounding farms. In 1818, Rochester exported 26,000 barrels of flour a year. Its mills were small, made up of twelve to fifteen men working alongside a master, in a single room, in the master’s house. There was, as there had been in such shops for centuries, a great deal of drinking: workers were often paid not in wages but in liquor. Work wasn’t done by the clock but by the task. By the end of the 1820s, after the completion of the canal, these small shops had become bigger shops, typically divided into two rooms and employing many more men, each doing a smaller portion of the work, and generally working by the clock, for wages. “Work” came to mean not simply labor but a place, the factory or the banker’s or clerk’s office: a place men went every day for ten or twelve hours. “Home” was where women remained, and where what they did all day was no longer considered work—that is, they were not paid. The lives of women and men diverged. Wage workers became less and less skilled. Owners made more and more money. Rochester was exporting 200,000 barrels of flour a year by 1828 and, by end of the 1830s, half a million. In 1829, a newspaper editor who used the word “boss” had to define it (“a foreman or master workman, of modern coinage”). By the early 1830s, only the boss still worked in the shop; his employees worked in factories. Masters, or bosses, no longer lived in shops, or even in the neighborhoods of factories: they moved to new neighborhoods, enclaves of a new middle class.14

That new middle class soon grew concerned about the unruliness of workers, and especially about their drinking. Inspired by a temperance crusade led by the revivalist Lyman Beecher, a group of mill owners formed the Rochester Society for the Promotion of Temperance. Its members pledged to give up all liquor and to stop paying their workers in alcohol. Swept up in the spirit of evangelical revival, they began to insist that their workers join their churches; and they ultimately fired those who did not. In this effort, they were led, principally, by their wives.

Women led the temperance movement, spurred to this particular crusade not least because drunken husbands tended to beat their wives. Few laws protected women from such assaults. Husbands addicted to drinking also spent their wages on liquor, leaving their children hungry. Since married women had no right to own property, they had no recourse under the law. Convincing men to give up alcohol seemed the best solution. But the movement was also a consequence of deeper and broader changes. With the separation of home from work there emerged an ideology of separate spheres: the public world of work and politics was the world of men; the private world of home and family was the world of women. Women, within this understanding, were the gentler sex, more nurturing, more loving, more moral. One advice manual, A Voice to the Married, told wives that they should make the home a haven for their husbands, “an Elysium to which he can flee and find rest from the story strife of a selfish world.” These changes in the family had begun before industrialization, but industrialization sped them up. Middle-class and wealthier women began having fewer children—an average of 3.6 children per woman in the 1830s, compared to 5.8 a generation earlier. No new method of contraception made this possible: declining fertility was the consequence of abstinence.15

Lyman Beecher wielded enormous influence in this era of reform, and so did his indomitable daughter Catherine, who advocated for the education of girls and published a treatise on “domestic economy”—advice for housewives.16 But the most powerful preacher to this new middle class, and especially to its women, was Charles Grandison Finney.

Finney had been born again in 1821, when he was twenty-nine, and the Holy Spirit descended upon him, as he put it, “like a wave of electricity.” He was ordained three years later by a female missionary society. He held big meetings and small, tent meetings and prayer groups. He looked his listeners in the eye. “A revival is not a miracle,” he said. “We are either marching towards heaven or towards hell. How is it with you?” Women didn’t always constitute the majority of converts, but their influence was felt on many who did convert. Another female missionary society invited Finney to Rochester in 1830, where he preached every night, and three times on Sunday, for six months. He preached to all classes, all sexes, and all ages but above all to women. Church membership doubled during Finney’s six-month stay in Rochester—driven by women. The vast majority of new joiners—more than 70 percent—followed the faith of their mothers but not of their fathers. One man complained after Finney visited: “He stuffed my wife with tracts, and alarmed her fears, and nothing short of meetings, day and night, could atone for the many fold sins my poor, simple spouse had committed, and at the same time, she made the miraculous discovery, that she had been ‘unevenly yoked.’” By exercising their power as moral reformers, the wives and daughters of factory owners brought their men into churches. Factory owners began posting job signs that read “None but temperate men need apply.” They even paid their workers to go to church. The revival was, for many Americans, heartfelt and abiding. But for many others, it was not. As one Rochester millworker said, “I don’t give a damn, I get five dollars more in a month than before I got religion.”17

If the sincerity of converts was often dubious, another kind of faith was taking deeper root in the 1820s, an evangelical faith in technological progress, an unquestioning conviction that each new machine was making the world better. That faith had a special place in the United States, as if machines had a distinctive destiny on the American continent. In prints and paintings, “Progress” appeared as a steam-powered locomotive, chugging across the continent, unstoppable. Writers celebrated inventors as “Men of Progress” and “Conquerors of Nature” and lauded their machines as far worthier than poetry. The triumph of the sciences over the arts meant the defeat of the ancients by the moderns. The genius of Eli Whitney, hero of modernity, was said to rival that of Shakespeare; the head of the U.S. Patent Office declared the steamboat “a mightier epic” than the Iliad.18

In 1829, Jacob Bigelow, the Rumford Professor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences at Harvard, delivered a series of lectures called “The Elements of Technology.” Before Bigelow, “technology” had meant the arts, mostly the mechanical arts. Bigelow used the word to mean the application of science for the benefit of society. For him, the “march of improvement” amounted to a kind of mechanical millennialism. “Next to the influence of Christianity on our moral nature,” he later proclaimed, technology “has had a leading sway in promoting the progress and happiness of our race.” His critics charged him with preaching “the gospel of machinery.”19

The Welshman Thomas Carlyle, calling the era “the Age of Machinery,” complained that faith in machines had grown into a religious delusion, as wrong and as dangerous as a belief in witchcraft. Carlyle argued that people like Bigelow, who believed that machines liberate mankind, made a grave error; machines are prisons. “Free in hand and foot, we are shackled in heart and soul with far straighter than feudal chains,” Carlyle insisted, “fettered by chains of our own forging.”20 America writers, refuting Carlyle, argued that the age of machinery was itself making possible the rise of democracy. In 1831, an Ohio lawyer named Timothy Walker, replying to Carlyle, claimed that by liberating the ordinary man from the drudgery that would otherwise prohibit his full political participation, machines drive democracy.21

Opponents of Andrew Jackson had considered his presidency not progress but decay. “The Republic has degenerated into a Democracy,” one Richmond newspaper declared in 1834.22 To Jackson’s supporters, his election marked not degeneration but a new stage in the history of progress. Nowhere was this argument made more forcefully, or more influentially, than in George Bancroft’s History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent to the Present. The book itself, reviewers noted, voted for Jackson. The spread of evangelical Christianity, the invention of new machines, and the rise of American democracy convinced Bancroft that “humanism is steady advancing,” and that “the advance of liberty and justice is certain.” That advance, men like Bancroft and Jackson believed, required Americans to march across the continent, to carry these improvements from east to west, the way Jefferson had pictured it. Democracy, John O’Sullivan, a New York lawyer and Democratic editor, argued in 1839, is nothing more or less than “Christianity in its earthly aspect.” O’Sullivan would later coin the term “manifest destiny” to describe this set of beliefs, the idea that the people of the United States were fated “to over spread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given for the development of the great experiment of liberty.”23

To evangelical Democrats, Democracy, Christianity, and technology were levers of the same machine. And yet, all along, there were critics and dissenters and objectors who saw, in the soul of the people, in the march of progress, in the unending chain of machines, in the seeming forward movement of history, little but violence and backwardness and a great crushing of men, women, and children. “Oh, America, America,” Maria Stewart cried, “foul and indelible is thy stain!”24

STEWART HAD STUDIED the Bible from childhood, a study she kept up her whole life, even as she scrubbed other people’s houses and washed other people’s clothes. “While my hands are toiling for their daily sustenance,” she wrote, “my heart is most generally meditating upon its divine truths.”25 She considered slavery a sin. She took her inspiration from Scripture. “I have borrowed much of my language from the holy Bible,” she said.26 But she also borrowed much of her language—especially the language of rights—from the Declaration of Independence. That the revival of Christianity coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration, an anniversary made all the more mystical when the news spread that both Jefferson and Adams had died that very day, July 4, 1826, as if by the hand of God, meant that the Declaration itself took on a religious cast. The self-evident, secular truths of the Declaration of Independence became, to evangelical Americans, the truths of revealed religion.

To say that this marked a turn away from the spirit of the nation’s founding is to wildly understate the case. The United States was founded during the most secular era in American history, either before or since. In the late eighteenth century, church membership was low, and anticlerical feeling was high. It is no accident that the Constitution does not mention God. Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush wondered, politely, whether this error might be corrected, assuming it to have been an oversight. “Perhaps an acknowledgement might be made of his goodness or of his providence in the proposed amendments,” he urged.27 No correction was made.

The United States was not founded as a Christian nation. The Constitution prohibits religious tests for officeholders. The Bill of Rights forbids the federal government from establishing a religion, James Madison having argued that to establish a religion would be “to foster in those who still reject it, a suspicion that its friends are too conscious of its fallacies to trust it to its own merits.”28 These were neither casual omissions nor accidents; they represented an intentional disavowal of a constitutional relationship between church and state, a disavowal that was not infrequently specifically stated. In 1797, John Adams signed the Treaty of Tripoli, securing the release of American captives in North Africa, and promising that the United States would not engage in a holy war with Islam because “the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”29

But during the Second Great Awakening, evangelicals recast the nation’s origins as avowedly Christian. “Upon what was America founded?” Maria Stewart asked, and answered, “Upon religion and pure principles.”30 Lyman Beecher argued that the Republic, “in its constitution and laws, is of heavenly origin.”31 Nearly everything took on a religious cast during the revival, not least because of the proliferation of preachers. In 1775, there had been 1,800 ministers in the United States; by 1845, there were more than 40,000.32 They were Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Episcopalian, Universalist, and more, very much the flowering of religious expression that Madison had predicted would result from the prohibition of an established religion. The separation of church and state allowed religion to thrive; that was one of its intentions. Lacking an established state religion, Americans founded new sects, from Shakers to Mormons, and rival Protestant denominations sprung up in town after town. Increasingly, the only unifying, national religion was a civil religion, a belief in the American creed. This faith bound the nation together, and provided extraordinary political stability in an era of astonishing change, but it also tied it to the past, in ways that often proved crippling. In 1816, when Jefferson was seventy-three and the awakening was just beginning, he warned against worshipping the men of his generation. “This they would say themselves, were they to rise from the dead,” he wrote: “. . . laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.” To treat the founding documents as Scripture would be to become a slave to the past. “Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the ark of the covenant, too sacred to be touched,” Jefferson conceded. But when they do, “They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human.”33

Abolitionists adopted a different posture. They didn’t worship the founders; they judged them. In the spring of 1829, William Lloyd Garrison, who’d entered the evangelical movement as an advocate of temperance and had only lately begun to concern himself with the problem of slavery, was asked to deliver a Fourth of July address before a Massachusetts branch of the Colonization Society, at the Park Street Church in Boston. He declared that the holiday was filled with “hypocritical cant about the inalienable rights of man.”34

This complicated position, a sense of the divinity of the Declaration of Independence, mixed with fury at the founders themselves, came, above all, from black churches, like the church where Maria Stewart and her husband were married, the African Meeting House on Belknap Street, in Boston’s free black neighborhood, on a slope of Beacon Hill known as “Nigger Hill.”35 Their friend David Walker, a tall, freeborn man from North Carolina, lived not far from the meetinghouse, and kept a slop shop on Brattle Street, selling gear to seamen; he likely traded with James W. Stewart, who earned his living outfitting ships. Walker was born in Wilmington, North Carolina. His father was a slave, his mother a free black woman. Sometime between 1810 and 1820, he’d moved from Wilmington to Charleston, South Carolina, probably drawn to its free black community and to its church. At the very beginning of the revival, in 1816, the African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in Philadelphia. Charleston opened an AME church in 1817; Walker joined.

While men like Finney preached to the workers and bosses of Rochester, New York, black evangelicals preached to free blacks who were keenly aware of the very different effects of the age of the machine on the lives of slaves and slave families. Cotton production in the South doubled between 1815 and 1820, and again between 1820 and 1825. Cotton had become the most valuable commodity in the Atlantic world. The Atlantic slave trade had been closed in 1808, but the new and vast global market for cotton created a booming domestic market for slaves. By 1820, more than a million slaves had been sold “down the river,” from states like Virginia and South Carolina to the territories of Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Another million people were sold, and shipped west, between 1820 and 1860. Mothers were separated from their children, husbands from wives. When the price of cotton in Liverpool went up, so did the price of slaves in the American South. People, like cotton, were sold by grades, advertised as “Extra Men, No.1 Men, Second Rate or Ordinary Men, Extra Girls, No.1 Girls, Second Rate or Ordinary Girls.” Slavery wasn’t an aberration in an industrializing economy; slavery was its engine. Factories had mechanical slaves; plantations had human slaves. The power of machines was measured by horsepower, the power of slaves by hand power. A healthy man counted as “two hands,” a nursing woman as a “half-hand,” a child as a “quarter-hand.” Charles Ball, born in Maryland during the American Revolution, spent years toiling on a slave plantation in South Carolina, and time on an auction block, where buyers inspected his hands, moving each finger in the minute action required to pick cotton. The standard calculation, for a cotton crop, “ten acres to the hand.”36

David Walker, living in Charleston, bore witness to those sufferings, and he prayed. So did Denmark Vesey, a carpenter who worshipped with Walker at the same AME church. In 1822, Vesey staged a rebellion, leading a group of slaves and free blacks in a plan to seize the city. Instead, Vesey was caught and hanged. Slave owners blamed black sailors, who, they feared, spread word in the South of freedom in the North and of independence in Haiti. After Vesey’s execution, South Carolina’s legislature passed the Negro Seaman Acts, requiring black sailors to be held in prison while their ships were in port.37 Walker decided to leave South Carolina for Massachusetts, where he opened his shop for black sailors and helped found the Massachusetts General Colored Association, the first black political organization in the United States. Meanwhile, he helped runaways. “His hands were always open to contribute to the wants of the fugitive,” the preacher Henry Highland Garnet later wrote. And he studied; he “spent all his leisure moments in the cultivation of his mind.”38 He also began helping to circulate in Boston the first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, published in New York beginning in 1827. “We wish to plead our own cause,” its editors proclaimed. “Too long have others spoken for us.”39

In the fall of 1829, the year Jacob Bigelow and Thomas Carlyle were arguing about the consequences of technological change, David Walker published a short pamphlet that struck the country like a bolt of lightning: An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to those of the United States of America. Combining the exhortations of a revivalist preacher with the rabble-rousing of a Jacksonian political candidate, Walker preached that, without the saving redemption of abolition, there would come a political apocalypse, the wages of the sin of slavery: “I call men to witness, that the destruction of the Americans is at hand, and will be speedily consummated unless they repent.”

Walker claimed the Declaration of Independence for black Americans: “‘We hold these truths to be self-evident—that ALL men are created EQUAL!! that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness!!’” He insisted on the right to revolution. Addressing his white readers, he wrote, “Now, Americans! I ask you candidly, was your sufferings under Great Britain, one hundredth part as cruel and tyrannical as you have rendered ours under you?” He described American expansion, the growth of the Union from thirteen states to twenty-four, as a form of violence: “the whites are dragging us around in chains and in handcuffs, to their new States and Territories, to work their mines and farms, to enrich them and their children.” And he damned manifest destiny as a fraud, resting on the belief of millions of Americans “that we being a little darker than they, were made by our Creator to be an inheritance to them and their children forever.” He called the scheme of Henry Clay’s American Colonization Society the “colonizing trick”: “This country is as much ours as it is the whites, whether they will admit it now or not, they will see and believe it by and by.” And he warned: “Are Mr. Clay and the rest of the Americans, innocent of the blood and groans of our fathers and us, their children?—Every individual may plead innocence, if he pleases, but God will, before long, separate the innocent from the guilty.” He asked black men to take up arms. “Look upon your mother, wife and children,” he urged, “and answer God Almighty; and believe this, that it is no more harm for you to kill a man, who is trying to kill you, than it is for you to take a drink of water when thirsty.” And, remarking on the history of the West Indies, he warned the owners of men: “Read the history particularly of Hayti, and see how they were butchered by the whites, and do you take warning.” In an age of quantification, Walker made his own set of calculations: “God has been pleased to give us two eyes, two hands, two feet, and some sense in our heads as well as they. They have no more right to hold us in slavery than we have to hold them.” And then: “I do declare it, that one good black man can put to death six white men.”40

The preaching of David Walker, even more than the preaching of Lyman Beecher or Charles Grandison Finney, set the nation on fire. It was prosecutorial; it was incendiary. It was also widely read. Walker had made elaborate plans to get his Appeal into the hands of southern slaves. With the help of his friends Maria and James Stewart, he stitched copies into the linings of clothes he and Stewart sold to sailors bound for Charleston, New Orleans, Savannah, and Wilmington. The Appeal went through three editions in nine months. The last edition appeared in June of 1830; that August, Walker was found dead in the doorway of his Boston shop. There were rumors he’d been murdered (rewards of upward of $10,000 had been offered for him in the South). More likely, he died of tuberculosis. James and Maria Stewart moved into his old rooms on Belknap Street.41

Walker had died, but he had spread his word. In 1830, a group of slaves plotting a rebellion were found with a copy of the Appeal. With Walker, the antislavery argument for gradual emancipation, with compensation for slave owners, became untenable. Abolitionists began arguing for immediate emancipation. And southern antislavery societies shut their doors. As late as 1827, the number of antislavery groups in the South had outnumbered those in the North by more than four to one. Southern antislavery activists were usually supporters of colonization, not of emancipation. Walker’s Appeal ended the antislavery movement in the South and radicalized it in the North. Garrison published the first issue of the Liberator on January 1, 1831. It begins with words as uncompromising as Walker’s: “I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.”42

That summer, in Virginia, a thirty-year-old revivalist preacher named Nat Turner planned a slave rebellion for the Fourth of July. Turner’s rebellion was at once an act of emancipation and of evangelism. Both of his parents were slaves. His mother had been born in Africa; his father escaped to the North. The wife of Turner’s owner had taught him to read when he was a child; he studied the Bible. He worked in the fields, and he also preached. In 1828, he had a religious vision: he believed God had called him to lead an uprising. “White spirits and black spirits engaged in battle,” he later said, “. . . and blood flowed in streams.” He delayed until August, when, after killing dozens of whites, he and his followers were caught. Turner was hanged.

The rebellion rippled across the Union. The Virginia legislature debated the possibility of emancipating its slaves, fearing “a Nat Turner might be in every family.” Quakers submitted a petition to the state legislature calling for abolition. The petition was referred to a committee, headed by Thomas Jefferson’s thirty-nine-year-old grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, who proposed a scheme of gradual emancipation. Instead, the legislature passed new laws banning the teaching of slaves to read and write, and prohibiting, too, teaching slaves about the Bible.43 In a nation founded on a written Declaration, made sacred by evangelicals during a religious revival, reading about equality became a crime.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the sharp-eyed French political theorist and historian, landed in New York in May 1831, for a nine-month tour of the United States. Nat Turner waged his rebellion in Virginia that August. Maria Stewart’s first essay appeared in the Liberator that October. “If ever America undergoes great revolutions, they will be brought about by the presence of the black race on the soil of the United States,” Tocqueville predicted. “They will owe their origin, not to the equality, but to the inequality of condition.”44 Even as Tocqueville was writing, those revolutions were already being waged.

II.

MARIA STEWART WAS the first woman in the United States to deliver an address before a “mixed” audience—an audience of both women and men, which happened to have been, as well, an audience of both blacks and whites. She spoke, suitably, in a hall named after Benjamin Franklin. She said she’d heard a voice asking the question: “‘Who shall go forward, and take of the reproach that is cast upon the people of color? Shall it be a woman?’ And my heart made this reply—‘If it is thy will, be it even so, Lord Jesus!’”45

Stewart delivered five public addresses about slavery between 1831 and 1833, the year Garrison founded the American Anti-Slavery Society, in language that echoed hers. At the society’s first convention, Garrison declared, “We plant ourselves upon the Declaration of our Independence and the truths of Divine Revelation, as upon the Everlasting Rock.”46

Shall it be a woman? One consequence of the rise of Jacksonian democracy and the Second Great Awakening was the participation of women in the reformation of American politics by way of American morals. When suffrage was stripped of all property qualifications, women’s lack of political power became starkly obvious. For women who wished to exercise power, the only source of power seemingly left to them was their role as mothers, which, they suggested, rendered them morally superior to men—more loving, more caring, and more responsive to the cries of the weak.

Purporting to act less as citizens than as mothers, cultivating the notion of “republican motherhood,” women formed temperance societies, charitable aid societies, peace societies, vegetarian societies, and abolition societies. The first Female Anti-Slavery Society was founded in Boston in 1833; by 1837, 139 Female Anti-Slavery Societies had been founded across the country, including more than 40 in Massachusetts and 30 in Ohio. By then, Maria Stewart had stopped delivering speeches, an act that many women, both black and white, considered too radical for the narrow ambit of republican motherhood. After 1835, she never again spoke in public. As Catherine Beecher argued in 1837, in An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, with Reference to the Duty of American Females, “If the female advocate chooses to come upon a stage, and expose her person, dress, and elocution to public criticism, it is right to express disgust.”47

While women labored to reform society behind the scenes, men protested on the streets. The eighteen-teens marked the beginning of a decades-long struggle between labor and business. During the Panic of 1819, the first bust in the industrializing nineteenth century, factories had closed when the banks failed. In New York, a workingman’s wages fell from 75 cents to 12 cents a day. Those who suffered the most were men too poor to vote; it was, in many ways, the suffering of workingmen during that Panic of 1819 that had led so many men to fight for the right to vote, so that they could have a hand in the direction of affairs. Having secured the franchise, they attacked the banks and all manner of monopolies. In 1828, laborers in Philadelphia formed the Working Men’s Party. One writer in 1830 argued that commercial banking was “the foundation of artificial inequality of wealth, and, thereby, of artificial inequality of power.”48

Workingmen demanded shorter hours (ten, instead of eleven or twelve) and better conditions. They argued, too, against “an unequal and very excessive accumulation of wealth and power into the hands of a few.” Jacksonian democracy distributed political power to the many, but industrialization consolidated economic power in the hands of a few. In Boston, the top 1 percent of the population controlled 10 percent of wealth in 1689, 16 percent in 1771, 33 percent in 1833, and 37 percent in 1848, while the lowest 80 percent of the population controlled 39 percent of the wealth in 1689, 29 percent in 1771, 14 percent in 1833, and a mere 4 percent in 1848. Much the same pattern obtained elsewhere. In New York, the top 1 percent of the population controlled 40 percent of the wealth in 1828 and 50 percent in 1845; the top 4 percent of the population controlled 63 percent of the wealth in 1828 and 80 percent in 1845.49

Native-born workingmen had to contend with the ease with which factory owners could replace them with immigrants who were arriving in unprecedented numbers, fleeing hunger and revolution in Europe and seeking democracy and opportunity in the United States. Many parts of the country, including Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, recruited immigrants by advertising in European newspapers. Immigrants encouraged more immigrants, in the letters they wrote home to family and friends, urging them to pack their bags. “This is a free country,” a Swedish immigrant wrote home from Illinois in 1850. “And nobody needs to hold his hat in his hand for anyone else.” A Norwegian wrote from Minnesota, “The principle of equality has been universally accepted and adopted.”50

In 1831, twenty thousand Europeans migrated to the United States; in 1854, that number had risen to more than four hundred thousand. While two and a half million Europeans had migrated to all of the Americas between 1500 and 1800, the same number—two and a half million—arrived specifically in the United States between 1845 and 1854 alone. As a proportion of the U.S. population, European immigrants grew from 1.6 percent in the 1820s to 11.2 percent in 1860. Writing in 1837, one Michigan reformer called the nation’s rate of immigration “the boldest experiment upon the stability of government ever made in the annals of time.”51

The largest number of these immigrants were Irish and German. Critics of Jackson—himself the son of Irish immigrants—had blamed his election on the rising population of poor, newly enfranchised Irishmen. “Everything in the shape of an Irishman was drummed to the polls,” one newspaper editor wrote in 1828.52 By 1860, more than one in eight Americans were born in Europe, including 1.6 million Irish and 1.2 million Germans, the majority of whom were Catholic. As the flood of immigrants swelled, the force of nativism gained strength, as did hostility toward Catholics, fueled by the animus of evangelical Protestants.

In 1834, Lyman Beecher delivered a series of anti-Catholic lectures. The next year, Samuel F. B. Morse, a young man of many talents, best known as a painter, published a virulent treatise called Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States through Foreign Immigration, urging the passage of a new immigration law banning all foreign-born Americans from voting.53 Morse then ran for mayor of New York (and lost). Meanwhile, he began devising a secret code of dots and dashes, to be used on the telegraph machine he was designing. He believed there existed a Catholic plot to take over the United States. He believed that, to defeat such a plot, the U.S. government needed a secret cipher. Eventually, he decided that a better use of his code, not secret but public, would be to use it to communicate by a network of wires that he imagined would one day stretch across the entire continent. It wouldn’t be long, he predicted in 1838, before “the whole surface of this country would be channeled for those nerves which are to diffuse, with the speed of thought, a knowledge of all that is occurring throughout the land; making, in fact, one neighborhood of the whole country.”54

Could a mere machine quiet the political tumult? In Philadelphia in 1844, riots between Catholics and Protestants left twenty Americans dead. The single biggest wave of immigration in the period came between 1845 and 1849, when Ireland endured a potato famine. One million people died, and one and a half million left, most for the United States, where they landed in Eastern Seaboard cities, and settled there, having no money to pay their way to travel inland. (Patrick Kennedy, the great-grandfather of the first Catholic to be elected president of the United States, left Ireland in 1849.) They lived in all-Irish neighborhoods, generally in tenements, and worked for abysmal wages. New York lawyer George Templeton Strong, writing in his diary, lamented their foreignness: “Our Celtic fellow citizens are almost as remote from us in temperament and constitution as the Chinese.” The Irish, keen to preserve their religion and their communities, built Catholic churches and parochial schools and mutual aid societies. They also turned to the Democratic Party to defend those institutions. By 1850, one in every four people in Boston was Irish. Signs at shops began to read, “No Irish Need Apply.”55

Germans, who came to the United States in greater numbers than the Irish, suffered considerably less prejudice. They usually arrived less destitute, and could afford to move inland and become farmers. They tended to settle in the Mississippi or Ohio Valleys, where they bought land from earlier German settlers and sent their children to German schools and German churches. The insularity of both Irish and German communities contributed to a growing movement to establish tax-supported public elementary schools, known as “common schools,” meant to provide a common academic and civic education to all classes of Americans. Like the extension of suffrage to all white men, this element of the American experiment propelled the United States ahead of European nations. Much of the movement’s strength came from the fervor of revivalists. They hoped that these new schools would assimilate a diverse population of native-born and foreign-born citizens by introducing them to the traditions of American culture and government, so that boys, once men, would vote wisely, and girls, once women, would raise virtuous children. “It is our duty to make men moral,” read one popular teachers’ manual, published in 1830. Other advocates hoped that a shared education would diminish partisanship. Whatever the motives of its advocates, the common school movement emerged out of, and nurtured, a strong civic culture.56

Yet for all the abiding democratic idealism of the common school movement, it was animated, as well, by nativism. One New York state assemblyman warned: “We must decompose and cleanse the impurities which rush into our midst. There is but one rectifying agent—one infallible filter—the SCHOOL.” And critics suggested that common schools, vaunted as moral education, provided, instead, instruction in regimentation. Common schools emphasized industry—working by the clock. This curriculum led workingmen to voice doubts about the purpose of such an education, with Mechanics Magazine asking in 1834: “What is the education of a common school? Is there a syllable of science taught in one, beyond the rudiments of mathematics? No.”57

Black children were excluded from common schools, leading one Philadelphia woman to point out the hypocrisy of defenders of slavery who based their argument on the ignorance of Americans of African descent: “Conscious of the unequal advantages enjoyed by our children, we feel indignant against those who are continually vituperating us for the ignorance and degradation of our people.” Free black families supported their own schools, like the African Free School in New York, which, by the 1820s, had more than six hundred students. In other cities, black families fought for integration of the common schools and won. In 1855, the Massachusetts legislature, urged on by Charles Sumner, made integration mandatory. This occasioned an outcry. The New York Herald warned: “The North is to be Africanized. Amalgamation has commenced. New England heads the column. God save the Commonwealth of Massachusetts!” No other state followed. Instead, many specifically passed laws making integration illegal.58

With free schools, literacy spread, and the number of newspapers rose, a change that was tied to the rise of a new party system. Parties come and go, but a party system—a stable pair of parties—has characterized American politics since the ratification debates. In American history the change from one party system to another has nearly always been associated with a revolution in communications that allows the people to shake loose of the control of parties. In the 1790s, during the rise of the first party system, which pitted Federalists against Republicans, the number of newspapers had swelled. During the shift to the second party system, which, beginning in 1833, pitted Democrats against the newly founded Whig Party, not only did the number of newspapers rise, but their prices plummeted. The newspapers of the first party system, which were also known as “commercial advertisers,” had consisted chiefly of partisan commentary and ads, and generally sold for six cents an issue. The new papers cost only one cent, and were far more widely read. The rise of the so-called penny press also marked the beginning of the triumph of “facts” over “opinion” in American journalism, mainly because the penny press aimed at a different, broader, and less exclusively partisan, audience. The New York Sun appeared in 1833. “It shines for all” was its common-man motto. “The object of this paper is to lay before the public, at a price within the means of everyone, ALL THE NEWS OF THE DAY,” it boasted. It dispensed with subscriptions and instead was circulated at newsstands, where it was sold for cash, to anyone who had a ready penny. Its front page was filled not with advertising but with news. The penny press was a “free press,” as James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald put it, because it wasn’t beholden to parties. (Bennett, born in Scotland, had immigrated to the United States after reading Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography.) Since the paper was sold at newsstands, rather than mailed to subscribers, he explained, its editors and writers were “entirely ignorant who are its readers and who are not.” They couldn’t favor their readers’ politics because they didn’t know them. “We shall support no party,” Bennett insisted. “We shall endeavor to record facts.”59

During the days of the penny press, Tocqueville observed that Americans had a decided preference for weighing the facts of a matter themselves:

They mistrust systems; they adhere closely to facts and study facts with their own senses. As they do not easily defer to the mere name of any fellow man, they are never inclined to rest upon any man’s authority; but, on the contrary, they are unremitting in their efforts to find out the weaker points of their neighbor’s doctrine.60

The people wished to decide, not only on how to vote, but about what’s true, and what’s not.

I I I.

IF THOMAS JEFFERSON rode to the White House on the shoulders of slaves, Andrew Jackson rode to the White House in the arms of the people. By the people, Jackson meant the newly enfranchised workingman, the farmer and the factory worker, the reader of newspapers. In office, he pursued a policy of continental expansion, dismantled the national bank, and narrowly averted a constitutional crisis over the question of slavery. He also extended the powers of the presidency. “Though we live under the form of a republic,” Justice Joseph Story said, “we are in fact under the absolute rule of a single man.” Jackson vetoed laws passed by Congress (becoming the first president to assume this power). At one point, he dismissed his entire cabinet. “The man we have made our President has made himself our despot, and the Constitution now lies a heap of ruins at his feet,” declared a senator from Rhode Island, “When the way to his object lies through the Constitution, the Constitution has not the strength of a cobweb to restrain him from breaking through it.”61 His critics dubbed him “King Andrew.”

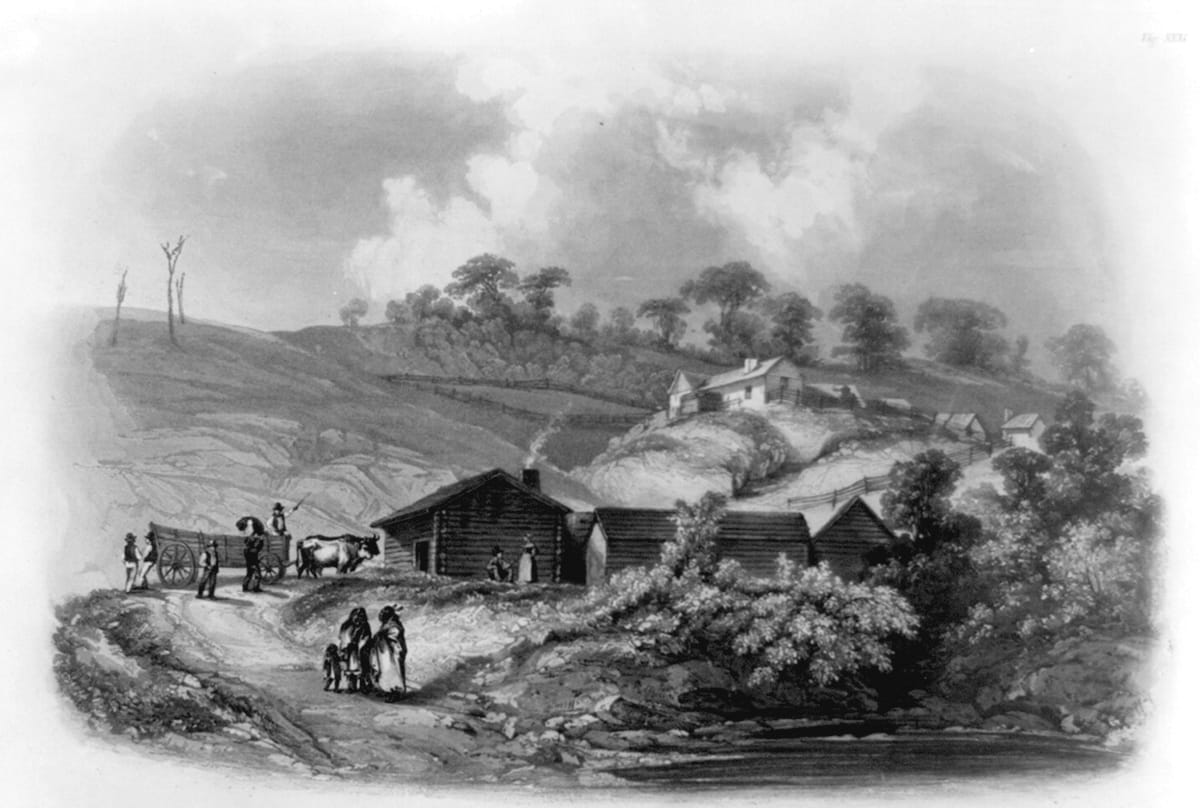

Jackson’s first campaign involved implementing the policy of Indian removal, forcibly moving native peoples east of the Mississippi River to lands to the west. This policy applied only to the South. There were Indian communities in the North—the Mashpees of Massachusetts, for instance—but their numbers were small. James Fennimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans (1826) was just one in a glut of romantic paeans to the “vanishing Indian,” the ghost of Indians past. “We hear the rustling of their footsteps, like that of the withered leaves of autumn, and they are gone forever,” wrote Justice Story in 1828. Jackson directed his policy of Indian removal at the much bigger communities of native peoples of the Southeast, the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Chocktaws, Creeks, and Seminoles who lived on homelands in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee, Jackson’s home state.62

To this campaign, Jackson brought considerable military experience. In 1814, he’d led a coalition of U.S. and Cherokee forces against the Creeks. After that war, the Creeks ceded more than twenty million acres of their land to the United States. In 1816 and 1817, Jackson then compelled his Cherokee allies to sign treaties selling to the United States more than three million acres for about twenty cents an acre. When the Cherokees protested, Jackson reputedly said, “Look around, and recollect what happened to our brothers the Creeks.”63 But the religious revival interfered with removal. In 1816, evangelicals from the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions began attempting to convert the Cherokee, declaring a mission “to make the whole tribe English in their language, civilized in their habits, and Christian in their religion,” a mission that, if accomplished, would seem to defeat the logic of removal in the name of “progress.” Meanwhile, the Cherokee decided to proclaim their political equality and declare their independence as a nation.64

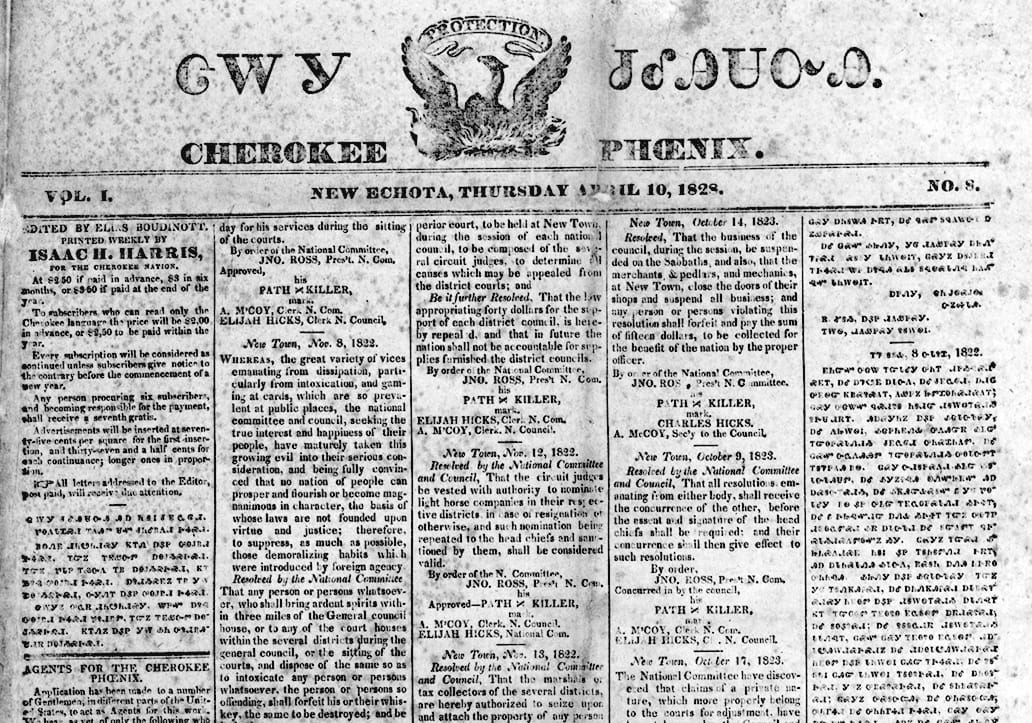

For centuries, Europeans had based their claims to lands in the New World on arguments that native peoples had no right to the land they inhabited, no sovereignty over it, because they had no religion, or because they had no government, or because they had no system of writing. The Cherokees, with deliberation and purpose, challenged each of these arguments. In 1823, when the federal government tried to get the Cherokees to agree to move, the Cherokee National Council replied, “It is the fixed and unalterable determination of this nation never again to cede one foot of land.” A Cherokee man named Sequoyah, who’d fought under Jackson during the Creek War, invented a written form of the Cherokee language, not an alphabet but a syllabary, with one character for every syllable. In 1825, the Cherokee Nation began printing the Phoenix, in both English and, using the syllabary, in Cherokee. In 1826, it established a national capital, at New Echota (just outside of what’s now Calhoun, Georgia), and in 1827 the National Council ratified a written constitution.65

South Carolina–born John C. Calhoun, Monroe’s secretary of war, pressed them: “You must be sensible that it will be impossible for you to remain, for any length of time, in your present situation, within the limits of Georgia, or any other State.” To whch the Cherokees replied: “We beg leave to observe, and to remind you, that the Cherokees are not foreigners, but original inhabitants of America; and that they now inhabit and stand on the soil of their own territory; . . . and that they cannot recognize the sovereignty of any State within the limits of their territory.”66

Jacksonians argued that, in the march of progress, the Cherokees had been left behind, “unimproved,” but the Cherokees were determined to call that bluff by demonstrating each of their “improvements.” In 1825, Cherokee property consisted of 22,000 cattle, 7,600 horses, 4,600 pigs, 2,500 sheep, 725 looms, 2,488 spinning wheels, 172 wagons, 10,000 plows, 31 grist mills, 10 sawmills, 62 blacksmith shops, 8 cotton gins, 18 schools, 18 ferries, and 1,500 slaves. The writer John Howard Payne, who lived with Cherokees in the 1820s, explained, “When the Georgian asks—shall savages infest our borders thus? The Cherokee answers him—‘Do we not read? Have we not schools? churches? Manufactures? Have we not laws? Letters? A constitution? And do you call us savages?’”67

They might have prevailed. They had the law of nations on their side. But then, in 1828, gold was discovered on Cherokee land, just fifty miles from New Echota, a discovery that doomed the Cherokee cause. When Jackson took office, in March 1829, he declared Indian removal one of his chief priorities and argued that the establishment of the Cherokee Nation violated Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution: “no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State” without that state’s approval.

Jackson’s Indian Removal Act aroused the ire of reformers and revivalists. David Walker had argued that Indian removal was just another version of the “colonizing trick.” Catharine Beecher, disavowing public speaking but advocating letter-writing, led an effort to submit a female petition opposing Indian removal to Congress. After considerable debate, the bill narrowly passed, the vote falling along sectional lines, New Englanders voting 28–9 against and southerners 60–15 in favor in the House while, in the Senate, New Englanders voted nearly uniformly against, and southerners unanimously in favor. The middle states were more divided. And yet the debate itself had raised, for everyone, broader questions about the nature of race, one senator from New Jersey inquiring, “Do the obligations of justice change with the color of the skin?”68

There remained the matter of the lawfulness of the act, and the question of its enforcement. The Cherokees argued that the state of Georgia had no jurisdiction over them, and the case went to the Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall said, “If courts were permitted to indulge their sympathies, a case better calculated to excite them can scarcely be imagined.” In his opinion, Marshall fatefully defined the Cherokee as “domestic dependent nations,” a new legal entity—not states and not quite nations, either. In another case the next year, Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Marshall elaborated: “The Cherokee Nation, then, is a distinct community, occupying its own territory, . . . in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter. . . . The Acts of Georgia are repugnant to the Constitution, laws, and treaties of the United States.”69

In New England, Marshall’s decision led tribes like the Penobscots and the Mashpees to press for their own independence. In 1833, the Mashpee people published An Indian’s Appeal to the White Men of Massachusetts, arguing, “As our brethren, the white men of Massachusetts, have recently manifested much sympathy for the red men of the Cherokee nation . . . we, the red men of the Mashpee tribe, consider it a favorable time to speak. We are not free. We wish to be so.”70 Marshall’s rulings in the Cherokee cases—which touched on the nature of title—inevitably occasioned a pained discussion about the European settlement of North America and the founding of the United States. In 1835, Edward Everett, a Massachusetts legislator who’d led the fight against Indian removal in Congress, balked at the hypocrisy of northern writers and reformers: “Unless we deny altogether the rightfulness of settling the continent,—unless we maintain that it was from the origin unjust and wrong to introduce the civilized race into America, and that the whole of what is now our happy and prosperous country ought to have been left, as it was found, the abode of barbarity and heathenism,—I am not sure, that any different result could have taken place.”71 Jackson agreed, asking, “Would the people of Maine permit the Penobscot tribe to erect an independent government within their State?”72

In the end, Jackson decided to ignore the Supreme Court. “John Marshall has made his decision,” he is rumored to have said (the rumor appears to have been a wild one). “Now let him enforce it.”73 The leaders of a tiny minority of Cherokees signed a treaty, ceding the land to Georgia and setting a deadline for removal at May 23, 1838. By the time the deadline came, only 2,000 Cherokees had left for the West; 16,000 more refused to leave their homes. U.S. Army General Winfield Scott, a fastidious career military man from Virginia known as “Old Fuss and Feathers,” arrived to force the matter. He begged the Cherokees to move voluntarily. “I am an old warrior, and have been present at many a scene of slaughter,” he said, “but spare me, I beseech you, the horror of witnessing the destruction of the Cherokees.” On the forced march 800 miles westward and, by Jefferson’s imagining, backward in time, one in four Cherokees died, of starvation, exposure, or exhaustion, on what came to be called the Trail of Tears. By the time it was over, the U.S. government had resettled 47,000 southeastern Indians to lands west of the Mississippi and acquired more than a hundred million acres of land to the east. In 1839, in Indian Territory, or what is now Oklahoma, the Cherokee men who’d signed the treaty were murdered by unknown assassins.74

By then, Jackson’s two terms in office had come to an end. But during the years he occupied the White House, between 1829 and 1837, ignoring a decision made by the Supreme Court had been neither the last nor the least of Andrew Jackson’s assertions of presidential power. Especially fraught was Jackson’s relationship with his first vice president, John C. Calhoun, Monroe’s former secretary of war, a fellow so stern and unyielding that one particularly shrewd observer dubbed him “cast-iron man.”75 Calhoun had served as John Quincy Adams’s vice president, too, and his relationship with Jackson had been strained from the start. Matters worsened when Calhoun led South Carolina’s attempt to “nullify” a tariff established by Congress. Like the struggle over Indian removal, the debate over the tariff stretched the limits of the powers of the Constitution to hold the states together.

One night in 1832, at a formal dinner, Jackson and Calhoun battled the matter out over drinks. The president offered a toast to “Our federal Union—it must be preserved.” After Jackson sat down, Calhoun rose from his seat to offer his own toast: “The Union—next to our liberty, the most dear; may we all remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states.” The much lesser political skills of former New York governor Martin Van Buren, also at the dinner that night, were in evidence when he rose to give a third toast, to “mutual forbearance and reciprocal concession.”76 Between Jackson and Calhoun, there would be no forbearance, and very little concession.

Although the tariff cut the duty on imports in half, it still worried southerners, who argued that it put the interest of northern manufacturers above southern agriculturalists. The South provided two-thirds of American exports (almost entirely in the form of cotton) and consumed only one-tenth of its imports, leading its politicians to oppose the tariff by endorsing a position that came to be called “free trade.”77

To protest the tariff, Calhoun wrote a treatise on behalf of the South Carolina legislature in which he developed a theory of constitutional interpretation under which he argued that states had the right to declare federal laws null and void. Influenced by the Kentucky and Virginia Resolves, drafted by Jefferson and Madison in 1798, and also by the Hartford Convention, in 1812, in which northern states had threatened to secede from the Union over their opposition to the war with Britain, Calhoun argued that if a state were to decide that a law passed by Congress was unconstitutional, the Constitution would have to be amended, and if such an amendment were not ratified—if it didn’t earn the necessary approval of three-quarters of the states—the objecting state would have the right to secede from the Union. The states had been sovereign before the Constitution was ever written, or even thought of, Calhoun argued, and they remained sovereign. Calhoun also therefore argued against majority rule; nullification is fundamentally anti-majoritarian. If states can secede, the majority does not rule.78

The nullification crisis was less a debate about the tariff than it was a debate about the limits of states’ rights and about the question of slavery, an early augury of the civil war to come. South Carolina had the largest percentage of slaves of any region in the country. Coming in the wake of David Walker’s Appeal and the challenge posed by the Cherokee Nation to the State of Georgia, nullification represented South Carolina’s attempt to reject the power of the federal government to set laws it found unfavorable to its interests.

Jackson responded with a proclamation in which he called Calhoun’s theory of nullification a “metaphysical subtlety, in pursuit of an impracticable theory.” Jackson’s case amounted to this: the United States is a nation; it existed before the states; its sovereignty is complete. “The Constitution of the United States,” Jackson argued, “forms a government, not a league.”79 In the end, Congress adopted a compromise tariff and South Carolina accepted it. “Nullification is dead,” Jackson declared. But the war was far from over. The nullification crisis hardened the battle lines between the sectionalists and the nationalists, while Calhoun became the leader of the proslavery movement, declaring that slavery is “indispensable to republican government.”80

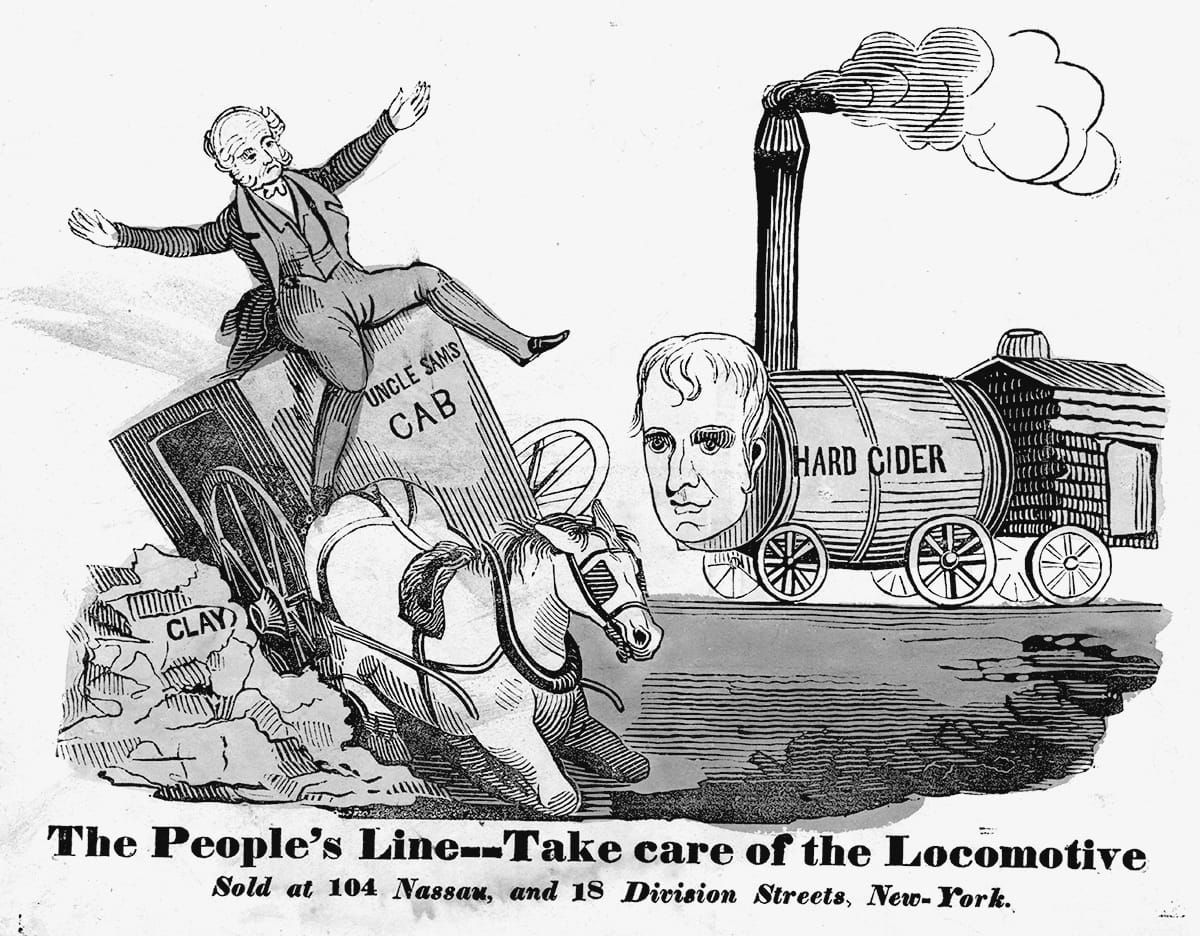

Jackson’s feud with Calhoun meant that he had not the least wish for him to continue as his vice president during a second term. Reluctant simply to drop Calhoun from the ticket for fear of political reprisal, Jackson cast about for a subtler means by which he could get rid of his cast-iron man. His eyes fell upon a new and short-lived political party, the Anti-Masons. In September of 1831, the Anti-Masons held the first presidential nominating convention in American history. Founded on the opposition to secret cabals, like Masons or political caucuses, the Anti-Masons had decided to borrow the idea of holding a gathering of delegates, like the constitutional conventions that had been held, year after year, in the states. Unfortunately, the man the Anti-Masons chose as their nominee turned out to be . . . a Mason. But the Anti-Masons’ nominating convention left two legacies: the practice of granting to each state delegation a number of votes equal to the size of its delegation in the Electoral College, and the rule by which a nomination requires a three-quarters vote. Two months after the Anti-Masons met, yet another short-lived party, the National Republican Party, held a convention of its own, in which roll was called of states, not in alphabetical order but in “geographical order,” beginning with Maine, and working down the coast, causing no small consternation among the gentlemen from Alabama.81 Henry Clay, asked by letter if he would be willing to be nominated by the short-lived National Republicans, wrote back to say yes but added that it was impossible for him to attend the convention in Baltimore “without incurring the imputation of presumptuousness or indelicacy.” Clay accepted the nomination, and set a precedent that lasted until Franklin Delano Roosevelt: for more than a century, no nominee accepted the nomination in person, and Roosevelt only did it because he was trying to put the point across that he was promising to offer Americans a “new deal.”82

Still, the practice of nominating a presidential candidate at a national party convention might not have become an American political tradition if Jackson hadn’t decided that the Democratic Party ought to hold one, too, so that he could get rid of his disputatious vice president. Jackson and his advisers realized that if they left the nomination to the state legislatures, where Calhoun had a great deal of support, they’d be stuck with him again. Jackson therefore contrived to have the New Hampshire legislature call for a national convention and to nominate Jackson as president and his pliable former secretary of state, New York governor Martin Van Buren, as his running mate.

The election of 1832 turned on the question of the national bank. Like the battles over Indian removal and the tariff, Jackson’s battle with the bank tested the power of the presidency. The issue was longstanding. Because the Constitution barred states from printing money, banks chartered by state legislatures printed their own money, not legal tender but banknotes, signed by bank presidents. Three hundred forty-seven banks opened up in the United States between 1830 and 1837. They printed their own money, producing more than twelve hundred different kinds of bills. Under this notoriously unstable arrangement, counterfeiting was rife, and so was swindling, especially by land banks, set up to speculate on western land.

In 1816, Congress had chartered a Second Bank of the United States, to help the nation recover from the devastation of the war with England. In 1819, the Supreme Court had upheld the constitutionality of the bank.83 The Bank of the United States served as the depository of all federal money; it handled its payments and revenues, including taxes. Nevertheless, it was a private bank reporting to stockholders. Its economic influence was extraordinary. By 1830, its holdings of $35 million amounted to twice the annual expenses of the federal government. To its severest critics, the national bank looked like an unelected fourth branch of the government.84 Jackson hated all banks. “I do not dislike your bank any more than all banks,” he told the bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle. Jackson believed that the Bank of the United States undermined the sovereignty of the people, defied their will, and, like all banks, had “a corrupting influence” on the nation by allowing “a few Monied Capitalists” to use public revenue, to “enjoy the benefit of it, to the exclusion of the many.”85

In January 1832, with Jackson nearing the end of his term, Biddle submitted to Congress a request to renew the bank’s charter, even though that charter wasn’t due to expire until 1836. Congress obliged. Clay promised, “Should Jackson veto it, I will veto him!”86 But in July 1832, Jackson did veto the bank bill, delivering an 8,000-word message in which he made clear that he believed the president has the authority to decide on the constitutionality of laws passed by Congress.

“It is maintained by the advocates of the bank that its constitutionality in all its features ought to be considered as settled by precedent and by the decision of the Supreme Court,” Jackson said. “To this conclusion, I cannot assent.”87 Biddle called Jackson’s veto message “a manifesto of anarchy.” But the Senate proved unable to override the veto. The Bank War, said Edward Everett, “is nothing less than a war of Numbers against Property.”88 Jackson, man of the people, King of Numbers, won in a rout.

IV.

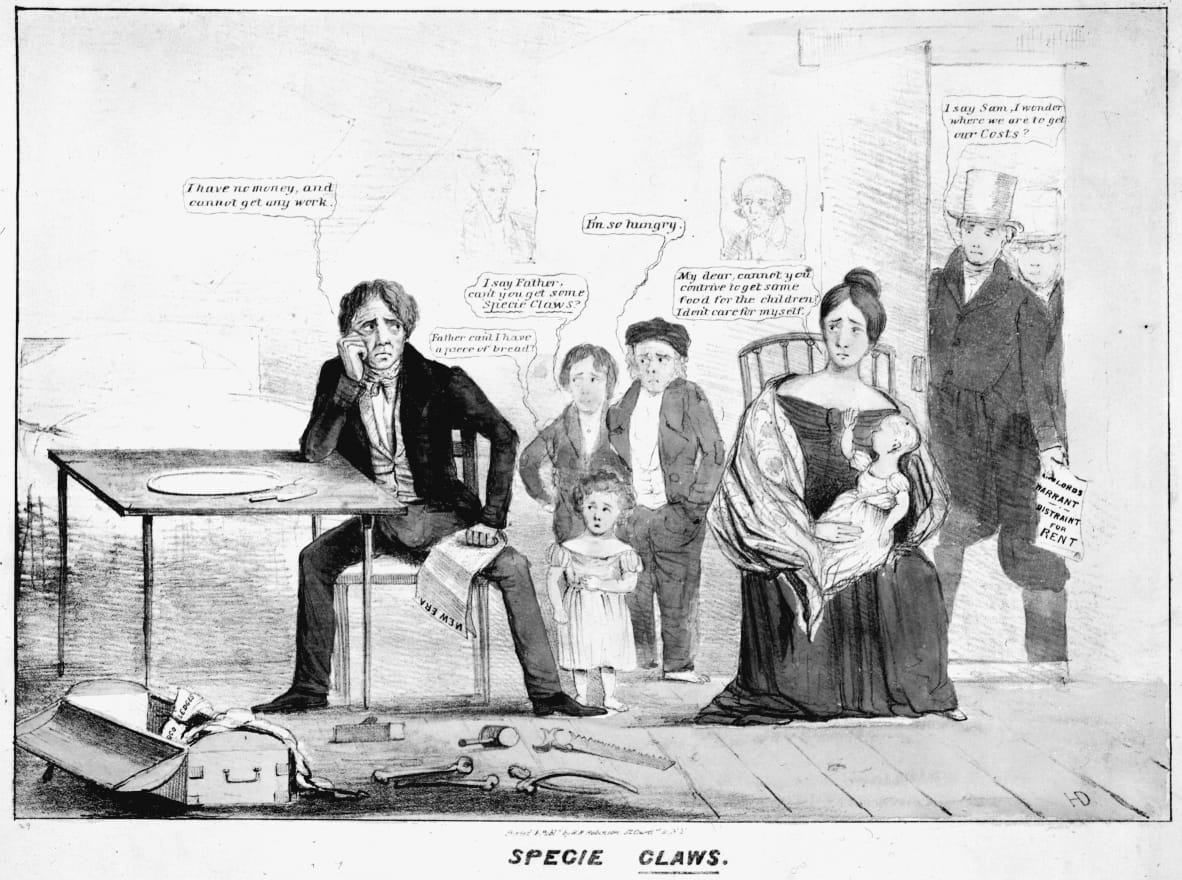

JACKSON’S BANK VETO unmoored the American economy. With the dissolution of the Bank of the United States, the stability it had provided, ballast in a ship’s hull, floated away. Proponents of the national bank had insisted on the need for federal regulation of paper currency. Jackson and his supporters, known as “gold-bugs,” would have rather had no paper money at all. In 1832, $59 million in paper bills was in circulation, in 1836, $140 million. Without the national bank’s regulatory force, very little metal backed up this blizzard of paper, American banks holding only $10.5 million in gold.89

Both speculators and the president looked to the West. “The wealth and strength of a country are its population, and the best part of the population are cultivators of the soil,” Jackson said, echoing Jefferson.90 Fleeing worsening economic conditions in the East and seeking new opportunities, Americans moved west, alone and with families, on wagons and trails, on canals and steamboats, to Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Alabama, Mississippi, Missouri, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Michigan. They homesteaded on farms; they built cabins out of rough-hewn logs. They started newspapers and argued about politics. They built towns and churches and schools. “I invite you to go to the West, and visit one of our log cabins, and number its inmates,” said one Indiana congressman. “There you will find a strong, stout youth of eighteen, with his better half, just commencing the first struggles of independent life. Thirty years from that time, visit them again; and instead of two, you will find in that same family twenty-two. This is what I call the American multiplication table.”91

Still, slavery haunted every step of westward settlement. Elijah Love-joy, born in Maine, settled in St. Louis, where he printed abolitionist tracts, the distribution of which was illegal in slave states, leading abolitionists to call for “free speech” against southerners’ demands for “free trade.” In 1836, proslavery rioters destroyed Lovejoy’s press. Lovejoy moved across the river, to the free state of Illinois, where he and his black typesetter, John Anderson, reopened their business with a new press. That press, too, was destroyed by a mob, and when a third press arrived, Lovejoy, who was armed, was shot in the chest and killed, a martyr to the cause of free speech.

To survey land and supervise settlement, Congress chartered the General Land Office. Surveyors laid the land out in grids of 640 acres. These they divided into 160-acre lots, as the smallest unit to be offered for sale. By 1832, during a boom in land sales—the office was receiving 40,000 patents a year—that minimum purchase was reduced to 40 acres. In 1835, Congress increased the number of clerks working at the Land Office from 17 to 88. Yet still they could not keep up with the volume of paperwork.

From the South, American settlers crossed the border into Mexico, which had won independence from Spain in 1821. Mexico had trouble managing its sprawling north; much of the land between its populous south, including its capital, Mexico City, and its most distant territory, Alta California, was desert, and chiefly occupied by Apaches, Utes, and Yaqui Indians. As one Mexican governor said, “Our territory is enormous, and our Government weak.” As early as 1825, John Quincy Adams had instructed the American minister to Mexico to try to negotiate a new boundary; the Mexican government needed the money but it wouldn’t sell its own land. As its minister, Manuel de Mier y Terán, argued: “Mexico, imitating the conduct of France and Spain, might alienate or cede unproductive lands in Africa or Asia. But how can it be expected to cut itself off from its own soil?”

Mexico wouldn’t sell its own land, but the Mexican territories of Coahuila and Texas, along the Gulf of Mexico, and west of the state of Louisiana, proved particularly attractive to American settlers in search of new lands for planting cotton. “If we do not take the present opportunity to people Texas,” one Mexican official warned, “day by day the strength of the United States will grow until it will annex Texas, Coahuila, Saltillo, and Nuevo León.” (At the time, Texas included much of what later became Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.) In 1835, Americans in Texas rebelled against Mexican rule, waging a war under the command of a political daredevil named Sam Houston. In 1836, Texas declared its independence, founding the Republic of Texas, with Houston its president. Mexico’s president, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, warned that, if he were to discover that the U.S. government had been behind the Texas rebellion, he would march “his army to Washington and place upon its Capitol the Mexican flag.”92