Seven

OF SHIPS AND SHIPWRECKS

THE DAY ABEL UPSHUR DIED, THE FATE OF THE UNION turned on the question of Texas. On the afternoon of February 28, 1844, Upshur, John Tyler’s secretary of state, boarded the USS Princeton, an iron-hulled, steam-powered warship, for a short trip along the icy waters of the Potomac. Tyler boarded, too, and so did all but one member of his cabinet, along with hundreds more dignitaries, soldiers, and sailors, and invited guests, in top hats and uniforms and snugly buttoned gowns, wrapped in woolen cloaks. James Madison’s aging widow, Dolley, was there, shivering against the wind, along with John C. Calhoun’s young son Patrick, a second lieutenant in the army, and General Juan Almonté, the straight-backed and stalwart Mexican ambassador, his cuffs embroidered with gold, his epaulets like wings.

The U.S. Senate was about to vote on a treaty to annex Texas, a long-sought land of ranges and plains, of cattle towns and rushing rivers. Upshur, fifty-three and balding, with a broad forehead and a long, slender nose, had stayed up late the night before, counting votes and pondering war. Mexico considered Texas one of its provinces, if a rebelling one. If the Senate approved annexation, Upshur knew, Mexico might well declare war on the United States. Upshur, who, before he became secretary of state, had been secretary of the navy, expected that war to be waged at sea, in the Gulf of Mexico, and he had been building up the fleet, preparing for battle. The USS Princeton was the navy’s most formidable warship; the point of setting forth on the Potomac was to offer—to Almonté—a demonstration of the ship’s fearsome cannon, the largest gun ever mounted on a battleship. It was called the Peacemaker.

As the ship steamed along the river, the gun was fired three times, each with a thundering, earth-shaking roar. Obeying the orders of the ship’s doctor, the guests kept their hands over their ears and their mouths wide open, to blunt the force of the shock wave. Almonté seemed suitably daunted. There was to be one more display: a salute to George Washington as the great ship steamed past Mount Vernon.1

Tyler, a gaunt and ungainly man, had staked his presidency on annexation. But his presidency had been weak from the start, and by the time the treaty was drafted, he was a president without a party. A southern aristocrat who despised populism, Tyler had been nominated as Harrison’s running mate because he’d been a vocal critic of both Jackson and Van Buren, and because Whigs hoped he would carry his crucial home state, Virginia. He’d hardly been queried on his politics, nor had voters been informed of them. As one campaign song had it, “We will vote for Tyler therefore / without a why or wherefore.” But Tyler did have political positions, strenuously held: he had long advocated states’ rights. An opponent of the national bank, Tyler didn’t like anything national; he once complained about the signs he saw all over Washington, DC: “National Hotel, National boot-black, National black-smith, National Oyster-house.”2 In April 1841, after Harrison died weeks after his inauguration, Congress had twice passed legislation renewing the charter of the national bank. And twice Tyler had vetoed it. By September, every member of Tyler’s cabinet except his secretary of state, Daniel Webster, had resigned in protest. Two days later, fifty Whig members of Congress gathered on the steps of the Capitol and banished the president from the party. Protesters rallied outside the White House. Fearful for his safety, Tyler had established a presidential police force (it later became the Secret Service). His only respite from the incessant political assault had come during a time of tragedy: his wife, Letitia, suffered a stroke. Having borne eight children, she died in the White House in September 1842. When Charles Dickens met Tyler while on a headlong tour of the United States that year, the novelist wrote that the president “looked somewhat worn and anxious, and well he might; being at war with everybody.”3

Abel Upshur came to be Tyler’s secretary of war after Webster, the last remaining member of Tyler’s original cabinet, resigned in May 1843 to protest the plan to annex Texas. Webster believed that the Republic was already large enough, and that any extension would diminish the spirit of the Union. How could people so different, spread across thousands of miles, even choose a ruler? He wondered “with how much of mutual intelligence, and how much of a spirit of conciliation and harmony, those who live on the St. Lawrence and the St. John might be expected ordinarily to unite in the choice of a President, with the inhabitants of the banks of the Rio Grande del Norte and the Colorado.”4

When Webster’s replacement died of a burst appendix, Tyler appointed Upshur. He might have seen something of himself in him. Upshur, like Tyler, was a southern aristocrat, disdainful of the people (they “read but little,” he said, “and they do not think at all”). Upshur believed that slavery solved the problem of the tensions between capital and labor by giving even a white man of desperate circumstances a reason to accept the economic order: “However poor, or ignorant or miserable he may be, he has yet the consoling consciousness that there is a still lower condition to which he can never be reduced.”5

Tyler and Upshur were convinced that the stability of the American republic rested on expansion. The Monroe Doctrine, crafted by John Quincy Adams in 1823, had warned Europeans not to found any new colonies in the Western Hemisphere, partly in order to keep the path clear for Americans. As one British newspaper observed at the time, “The plain Yankee of the matter is that the United States wish to monopolize to themselves the privilege of colonizing . . . every . . . part of the American continent.”6 Nevertheless, Great Britain’s North American territory, acquired long before the Monroe Doctrine, stretched all the way across the continent, while, in the Pacific Northwest, both Britain and the United States claimed the vast swath of land known as the Oregon Territory. Upshur feared Britain was making a bid to extend its borders to the south. Britain had been selling steam-powered warships to Mexico and offering to buy California. Upshur also believed rumors (which turned out to be false) that Britain had offered loans to Texas if it would abolish slavery, with an eye, presumably, to making Texas part of the British Empire, in which slavery had been abolished in 1833. Tyler’s plan was to annex Texas and have it enter the Union as a slave state, with the hope that he could arrange for the admission of Oregon as a free state, maintaining the balance of free states to slave.

Tyler and Upshur may have wanted to annex Texas in order to extend slavery into the West. But they steered clear of talking about it that way. They talked the language not of slavery but of liberty, making the argument—embraced by everyone from Jefferson to Tocqueville—that the acquisition of new territory provided economic opportunities to the poor, opportunities not available in Europe, because anyone could leave industry behind, move to the woods, build a cabin, fell trees, and plow fields.

In this new age of steam, when every metaphor, suddenly, had to do with engines, people talked about the West as a “safety valve,” releasing pent-up pressure to avoid an explosion. “The public lands are the great regulator of the relations of Labor and Capital,” said Horace Greeley, publisher of the New York Tribune, “the safety valve of our industrial and social engine.” (Greeley, who, with his slumped shoulders and flat face, looked rather like a frog, was the most widely read editorial writer of his generation.) Supporters of the annexation of Texas went further, applying this metaphor to the problem of slave rebellion. “If we shall annex Texas,” a Democratic senator from South Carolina promised in 1844, “it will operate as a safety-valve to let off this superabundant slave population from among us.”7

And the debate might have gone that way, were it not for what happened on board the USS Princeton February 28. As the ship passed Mount Vernon, the crew lit the Peacemaker for its final salute. Suddenly, the gun exploded. Seven men were killed in the blast, including Upshur, along with Tyler’s secretary of the navy and a New York merchant named David Gardiner, whose twenty-four-year-old daughter, Julia, was belowdecks with the president. If Tyler had been topside, he, too, would likely have been killed. Instead, he carried a fainting Julia Gardiner in his arms off the ship and onto a rescue boat.

The death of Upshur had serious political consequences. To replace him, Tyler appointed Calhoun as his new secretary of state. And Cast-Iron Calhoun talked about Texas only with reference to slavery.

As the debate over annexation intensified, John Quincy Adams, seventy-six, his face grown haggard but his political will unbroken, warned that if Texas were annexed, the North would secede; Calhoun, as lionlike at sixty-two as he had been in his youth, warned that the South would secede if it were not. The rivalry between the two men, begun with the “corrupt bargain” of 1828, continued undiminished, even if the explosion on the Potomac set them both back on their heels.

After a brief period of mourning, Congress resumed its business. “The treaty for the annexation of Texas to this Union was this day sent into the Senate,” Quincy Adams wrote in his diary in April, “and with it went the freedom of the human race.”8 Henry Clay called it “Mr. Tyler’s abominable treaty.”9 Quincy Adams insisted that annexing Texas would turn the Constitution into a “menstruous rag.”10

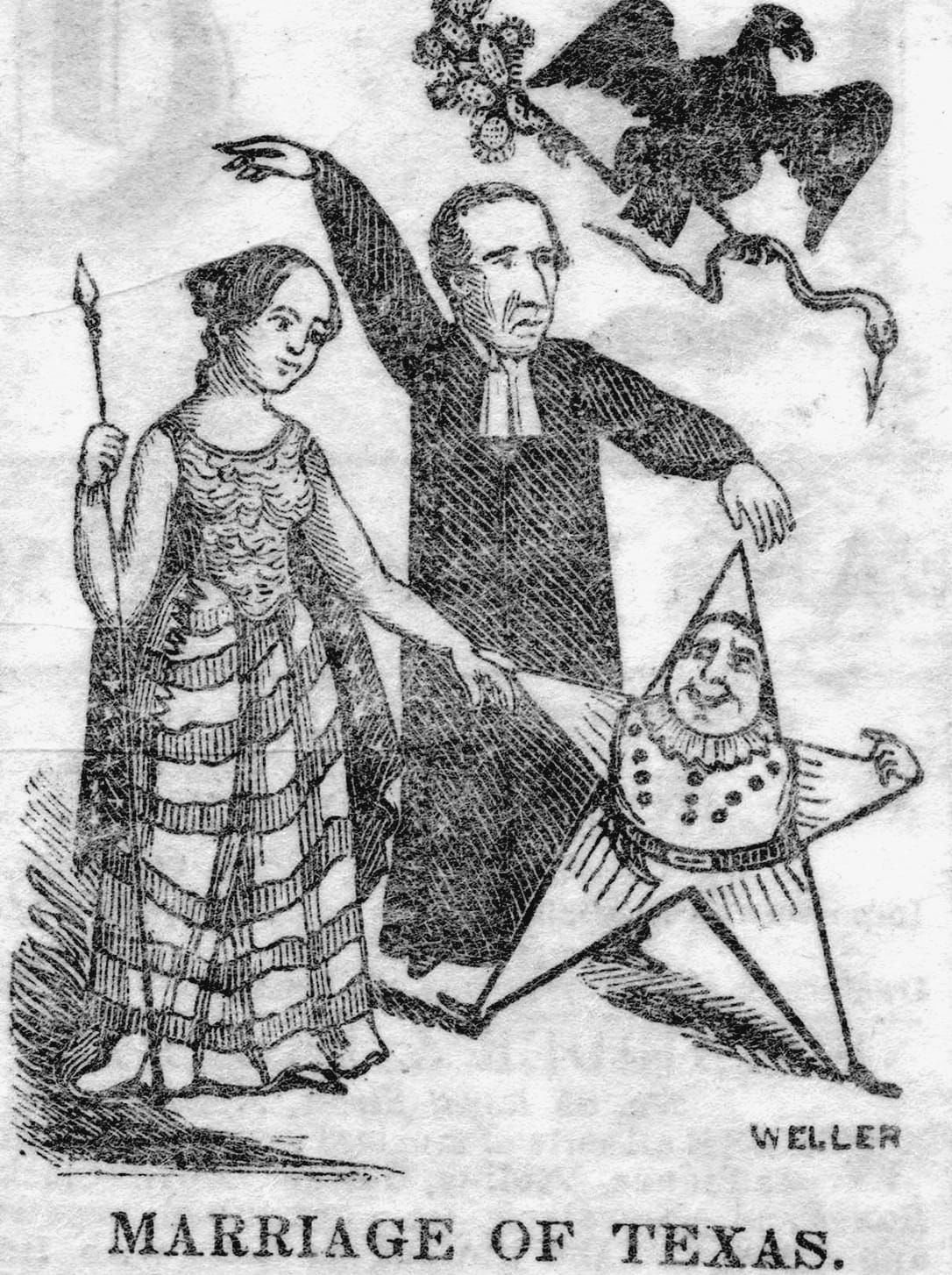

In June, the Senate failed to ratify the treaty by a vote of 35 to 16 that fell along sectional lines. Days later, when President Tyler married Julia Gardiner, white flowers wreathed in her hair, the New York Herald said of the wedding: “The President has concluded a treaty of immediate annexation, which will be ratified without the aid of the Senate of the United States.”11

Tyler, a better bridegroom than a president, decided to run for reelection even though no party would have him. He therefore more or less invented a third party—a one-man party—and called for a convention to nominate him under the banner of “Tyler and Texas.” He did not name a running mate; Texas was his running mate.

Tyler’s hope, in running, was to convince the Democrats to nominate him at their own convention. But Andrew Jackson, edging toward eighty in a not altogether quiet retirement at his slave plantation, had changed his mind about annexation. Earlier, he’d opposed it, fearing a war with Mexico. Now he favored it. But Van Buren did not. Jackson, still controlling the party, decided to thwart Van Buren’s attempt to win the Democratic nomination. Jackson called a meeting at the Hermitage. “General Jackson says the candidate for the first office should be an annexation man, and from the Southwest,” wrote James K. Polk, a Jackson loyalist. Polk became that man.12

Polk was forty-eight and wiry and had eyes like caverns and hair like smoke. A former Speaker of the House and governor of Tennessee, he was unknown outside his home state. “Who is James K. Polk?” became the motto of his opposition. Tyler, assured that the Democrats would fight for annexation, dropped out of the race.13

Henry Clay had been trying to become president of the United States since he was a boy in short pants in the hills of Virginia. He’d already run three times, but in 1844, when he was sixty-seven, the Whigs chose him once more. Clay opposed annexation, but not strenuously enough for abolitionists who left the Whigs to join the Liberty Party. The National Convention of Colored Men—men who hoped, one day, to be able to vote—endorsed the Liberty Party, too.

The race between Polk and Clay, a referendum on annexation, was extraordinarily close. In the end, Polk won the popular vote by a razor-thin margin of 38,000 votes out of 2.6 million cast. Tyler, limping to the end of his term, took Polk’s victory as a mandate for annexation and pressed the House for a vote. On January 25, 1845, the House passed a resolution in favor of annexation, 120–98, having devised a compromise under which the eastern portion of Texas would enter the Union as a slave state, but not the western portion. On February 28, the one-year anniversary of the disaster on the USS Princeton, the Senate approved that resolution by just two votes. It would fall to Polk to sign the formal treaty, but it was Tyler who signed the resolution, on March 1, three days before Polk took office. In a slight to his cast-iron secretary of state, he handed the pen he used to sign it not to Calhoun but to his new bride, Julia Gardiner, as if Texas were her wedding gift.

Two days later, General Almonté, with epaulets like wings, was recalled to Mexico. Both nations braced for war. American soldiers pointed their guns to the southwest, ready to fire shots across a border. But soon enough the United States would be at war with itself, a nation looking down the barrel of its own gun.

I.

IN THE 1840S AND 1850S, the United States faced a constitutional crisis that recast the parties and deepened the national divide. Expansion, even more than abolition, pressed upon the public the question of the constitutionality of slavery. How or even whether this crisis would be resolved was difficult to see not only because of the nature of the dispute but also because there existed very little agreement about who might resolve it: Who was to decide whether a federal law was unconstitutional?

One man of unbounded temerity had said that the Supreme Court could decide. In 1803, in Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall had asserted that “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Marshall may have established a precedent for judicial review, but he had hardly made it a practice. Before his death, in 1835, at the age of seventy-nine, he served on the court for thirty-four years; Marbury is the only time the Marshall Court overturned a federal law.

Another man of similar disposition had said that the states had this authority. When, in 1832, Calhoun, on behalf of South Carolina, had argued that the states can simply nullify acts of Congress, his argument had failed, and making it had nearly destroyed his career.

A third man, not to be undone in the matter of audacity, insisted that this power lay with the president alone. When Jackson vetoed the Bank Act, he had demonstrated that the president has the power to block legislation, but while Jackson sorely wished he had the authority to pronounce laws unconstitutional, this was the merest fancy.

In the midst of all this clamoring among the thundering white-haired patriarchs of American politics, there emerged the idea that the authority to interpret the Constitution rests with the people themselves. Or, at least, this became a rather fashionable thing to say. “It is, Sir, the people’s Constitution, the people’s government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people,” Daniel Webster roared from the floor of Congress.14 Every man could read and understand the Constitution, Webster insisted. As to the actual state of affairs, there was considerable disagreement. In 1834, Justice Joseph Story published a schoolbook in which he attempted to illustrate the nation’s laws to its children. “The Constitution is the will, the deliberate will, of the people,” he explained.15 Tocqueville rhapsodized that the American people knew their Constitution as if by heart. “I scarcely ever met with a plain American citizen who could not distinguish with surprising facility the obligations created by the laws of Congress from those created by the laws of his own state,” the Frenchman reported.16 He thought that the American people were fitted to their Constitution like a hand to a glove. But William Grimes, who escaped from slavery in Virginia 1814 and became a barber in Connecticut—and who was the sort of person Tocqueville never interviewed—had a different idea about just how fitted were the people and the parchment: “If it were not for the stripes on my back which were made while I was a slave,” Grimes wrote, “I would in my will, leave my skin a legacy to the government, desiring that it might be taken off and made into parchment and then bind the Constitution of glorious happy and free America.”17 Americans’ deepest and most abiding divide turned on this starkly different reading of their Constitution, in what meaning lay between the ink written onto parchment and the scars etched on a black man’s back.

A great many people on both sides of this divide had hoped that the long-awaited publication of James Madison’s Notes on the debates at the constitutional convention would cast so much light on the question of slavery as to resolve it. Madison had been asked, time and again, to resolve disputes by revealing their contents. But he refused, steadfast in keeping his vow of secrecy. For years, for decades, Madison had added to and revised his record of what was said and done in the Pennsylvania State House in the long, hot summer of 1787. He’d puttered away at it. The Constitution couldn’t be rewritten or easily amended—but Madison’s Notes could. As the years passed, and Madison grew old, he observed how many other nations had followed the United States’ lead and written their own constitutions: France, Haiti, Poland, the Netherlands, Switzerland. By 1820, at least sixty constitutions had been written in Europe alone; eighty more would be written by 1850. Very few of those constitutions lasted.18

In 1836, Madison turned eighty-five and collapsed at the breakfast table. “The Sage of Montpelier Is No More!” announced the Charleston Courier, in a column blocked in black.19 He was the last delegate to the constitutional convention to die. Madison’s will, made public that summer, revealed two facts that agitated each side in the debate over slavery: he had not freed his slaves, and he had arranged for a sizable part of the proceeds of the publication of his Notes to go the American Colonization Society. The next year, the fifty-year reign of secrecy came to a close. But so nervous were members of Congress about what the Notes might contain, and how their publication would turn the political winds, that when Dolley Madison asked Congress to pay for the printing, the panicked House could hardly manage to hold a vote.20

In the end, Congress approved the expense, and the Notes were finally printed in 1840. Far from settling the issue of whether the Constitution did or did not sanction slavery, publication gave partisans on all sides more ammunition for their arguments. Radical abolitionists, finding in the Notes evidence of coldhearted deal making in Philadelphia, came to consider the Constitution unredeemable. William Lloyd Garrison, peering out from narrow spectacles, would infamously call the Constitution “a Covenant with Death and an Agreement with Hell.” But other opponents of slavery quoted from Madison’s Notes to argue that the Constitution most specifically did not sanction slavery. In The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, Massachusetts lawyer Lysander Spooner damned Garrison for damning the Constitution and wondered why abolitionists were so scared of using it as a weapon: “If they have the constitution in their hands, why, in heaven’s name do they not out with it, and use it?”21

The Notes, it appeared, could be read as variously as the Constitution itself. As one shrewd observer remarked, “The Constitution threatens to be a subject of infinite sects, like the Bible.” And, as with many sects, those politicians who most strenuously staked their arguments on the Constitution often appeared the least acquainted with it. Remarked New York governor Silas Wright, “No one familiar with the affairs of our government, can have failed to notice how large a proportion of our statesmen appear never to have read the Constitution of the United States with a careful reference to its precise language and exact provisions, but rather, as occasion presents, seem to exercise their ingenuity . . . to stretch both to the line of what they, at the moment, consider expedient.”22

And so it came to pass that in 1846, when the United States faced war with Mexico, Americans had yet to settle some seemingly elemental matters relating to their system of government. Annexing Texas meant trying to stretch the already taut parchment of the Constitution across still vaster distances. And the possibility of annexing conquered parts of Mexico meant something else, too—not merely extending the Republic but founding an empire.

A NATION HAS borders but the edges of an empire are frayed.23 While abolitionists damned the annexation of Texas as an extension of the slave power, more critics called it an act of imperialism, inconsistent with a republican form of government. “We have a republic, gentlemen, of vast extent and unequalled natural advantages,” Daniel Webster pointed out. “Instead of aiming to enlarge its boundaries, let us seek, rather, to strengthen its union.”24 Webster lost that argument, and, in the end, it was the American reach for empire that, by sundering the Union, brought about the collapse of slavery.

No American president made that reach for empire with more bluster and determination than James K. Polk. Texas was only the beginning. Polk wanted to acquire Florida, too, and, he hoped, Cuba. (“As the pear, when ripe, falls by the law of gravity into the lap of the husbandman,” Calhoun had once said, “so will Cuba eventually drop into the lap of the Union.”)25 But when Polk sent an agent to Spain, he was told that, rather than sell Cuba to the United States, Spain “would prefer seeing it sunk in the Ocean.”26

More immediately, Polk wanted to acquire Oregon, an expanse of achingly beautiful land that included all of what later became Oregon, Idaho, and Washington, and much of what later became Montana and Wyoming. “Our title to the country of Oregon is clear and unquestionable,” Polk announced, as if willing this to be true. Britain, Russia, Spain, and Mexico had all made claims to the Oregon Territory. Americans, though, had been staking their claim by moving there. They’d been heading west from Missouri along the arduous Oregon Trail, a series of old Indian roads that cut across mountains and unfurled over valleys and snaked along streams. In 1843, some eight hundred Americans traveled the Oregon Trail, carrying their children in their arms and pulling everything they owned in wind-swept wagons. With Polk’s pledge behind them, hundreds became thousands. They traveled in caravans, guided by little more than books like Lansford W. Hastings’s Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California and John C. Frémont’s Report of an Exploration . . . between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains (1843) or his Report of the Exploring Expedition to Oregon and California (1845). Frémont, born in Georgia in 1813, had been commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. During a series of extraordinary expeditions, he mapped much of the West. How much of this territory did Americans want? The answer became a rallying cry: “The Whole of Oregon!”27

To the southwest, Polk had no intention of ending his reach with the annexation of Texas. Nor did John O’Sullivan, editor of the Democratic Review. “Texas is now ours,” O’Sullivan wrote in 1845, and California would soon be, too: “it will be idle of Mexico to dream of dominion.”28 Immediately after Mexico severed diplomatic relations with the United States, Polk sent an envoy to Mexico with $25 million in hopes of buying three stretches of land: the Nueces Strip, a patch of disputed territory claimed by both Texas and Mexico; New Mexico; and Alta California, north of Baja California and including parts of what became Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. When Mexico refused to treat with the Polk delegation, Polk ordered U.S. troops into the Nueces Strip; they set up camp along the Rio Grande. To lead them, Polk passed over more experienced generals in favor of Zachary Taylor, a fellow southerner unlikely to question his questionable orders.

Polk hoped to provoke a confrontation and soon got what he was after. During a skirmish on April 25, 1846, Mexican forces killed eleven U.S. soldiers. Polk asked Congress to declare war. “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil,” he insisted.29 Not everyone was convinced that Mexico had fired first, or that the Americans who were killed had been standing on American soil when they were shot. In Congress, a gangly young House member from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln introduced resolutions, the so-called spot resolutions, demanding to know the exact spot where American blood was first shed on American soil. He earned the nickname Spotty Lincoln. He did not prevail.

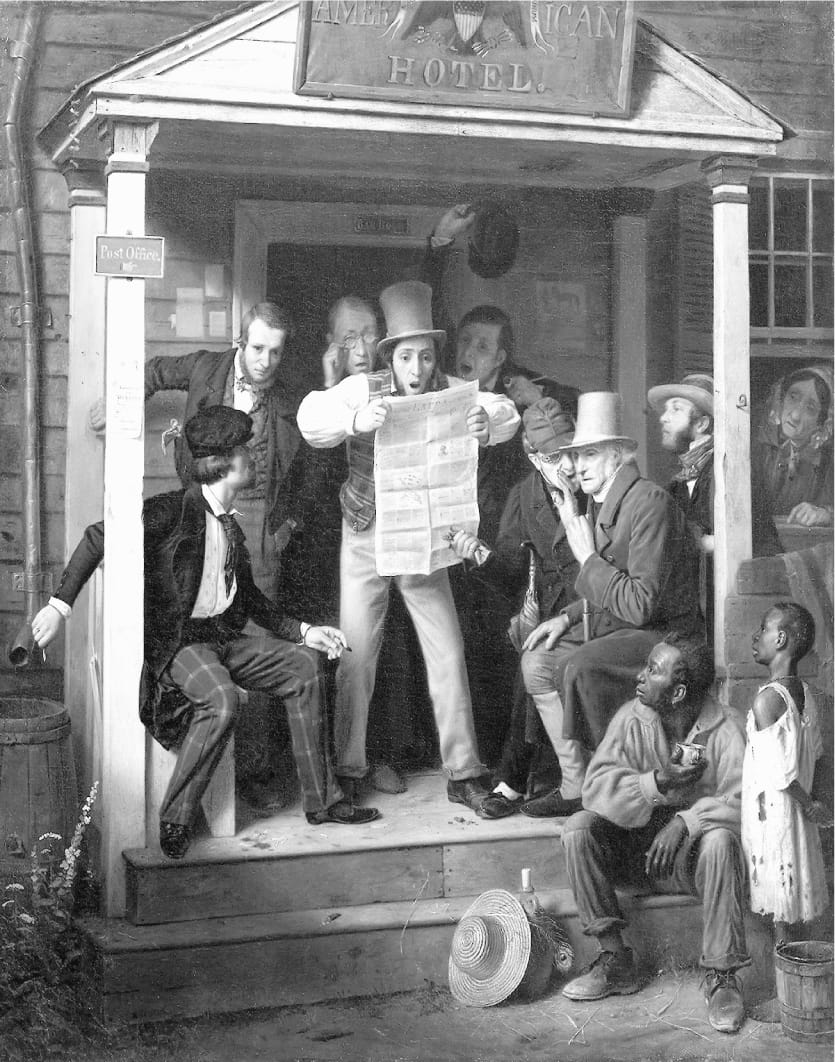

Congress granted Polk his declaration, and war came, but opposition escalated, not least because troubling news from Mexico traveled to American cities in record-breaking time. At the outbreak of the war, the publisher of the New York Sun established an ad hoc news-gathering network involving boats and stagecoaches and early telegraph operators. The Sun’s scheme came to be called “the wire service” and, later, the Associated Press.30

Polk’s very slender victory at the polls proved a thin reed on which to wage a war of aggression in the name of the American people. Nor did Congress escape heightened scrutiny. In the quarrelsome 1840s, visitors to Congress very often found its deliberations contemptible, but no one was more severe on this subject than the author of Pickwick Papers. During his stay in Washington, Charles Dickens, who had started out as a police reporter, visited the House and Senate every day, sitting in the galleries, taking notes. He found the rooms in the Capitol attractive and well appointed—“both houses are handsomely carpeted,” he allowed—and the Senate was “dignified and decorous,” its deliberations “conducted with much gravity and order.” But meetings of the House of Representatives, he said, were “the meanest perversion of virtuous Political Machinery that the worst tools ever wrought.” Its members were cowardly, petty, cussed, and degraded. Dickens, for all the flair of his pen, had by no means exaggerated. Although hardly ever reported in the press, the years between 1830 and 1860 saw more than one hundred incidents of violence between congressmen, from melees in the aisles to mass brawls on the floor, from fistfights and duels to street fights. “It is the game of these men, and of their profligate organs,” Dickens wrote, “to make the strife of politics so fierce and brutal, and so destructive of all self-respect in worthy men, that sensitive and delicate-minded persons shall be kept aloof, and they, and such as they, be left to battle out their selfish views unchecked.” Dickens knew a rogue when he heard one and a circus when he saw one.31

Nearly as soon as the war with Mexico began, members of Congress began debating what to do when it ended. They spat venom. They pulled guns. They unsheathed knives. Divisions of party were abandoned; the splinter in Congress was sectional. Before heading to the Capitol every morning, southern congressmen strapped bowie knives to their belts and tucked pistols into their pockets. Northerners, on principle, came unarmed. When northerners talked about the slave power, they meant that literally.32

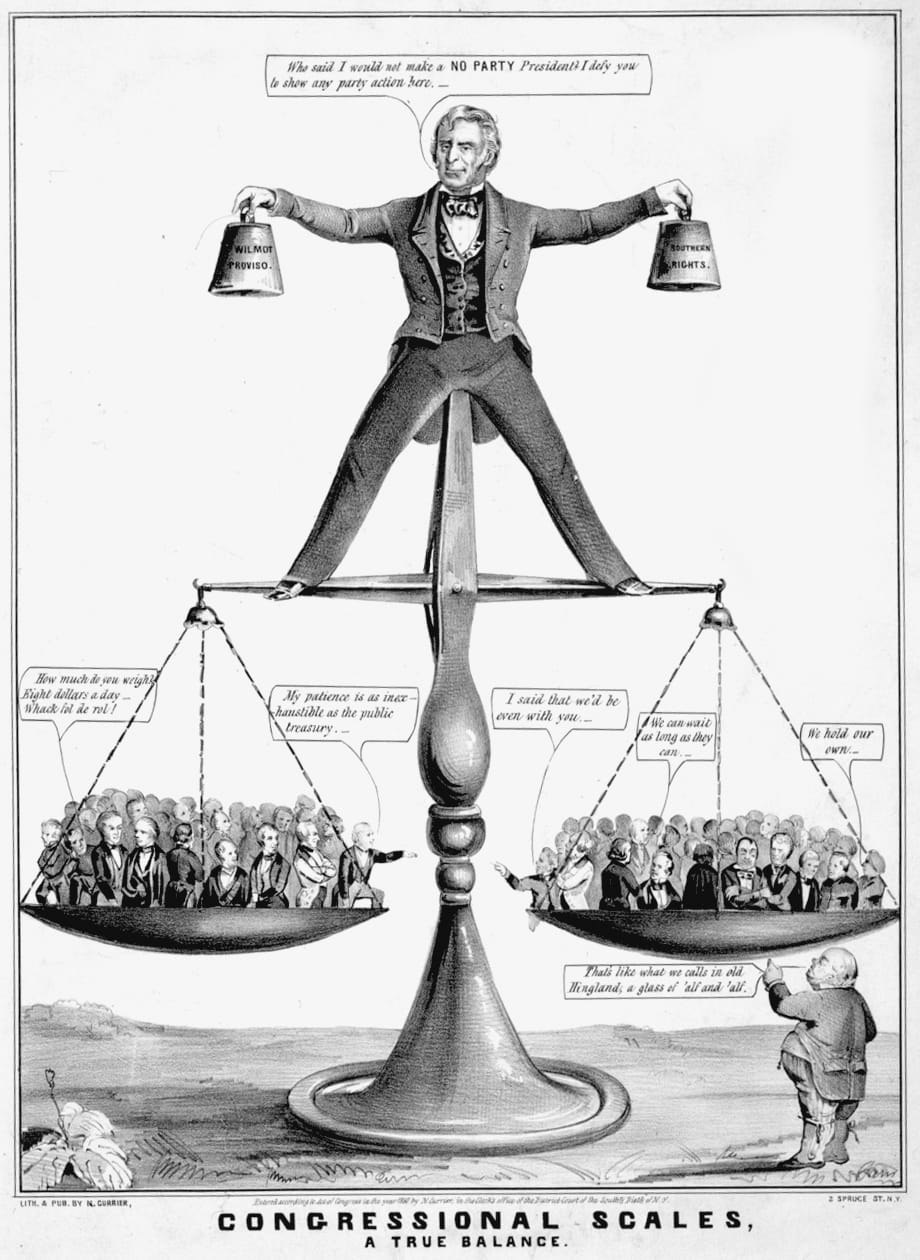

If the United States were to acquire territory from Mexico, and if this territory were to enter the Union, would Mexicans become American citizens? Calhoun, now in the Senate, vehemently opposed this idea. “I protest against the incorporation of such a people,” he declared. “Ours is the government of the white man.”33 And what about the territory itself: would these former parts of Mexico enter the Union as free states or slave? In 1846, David Wilmot, a thirty-two-year-old Democratic congressman from Pennsylvania who looked as meek as a schoolmaster, suggested that a proviso be added to any treaty negotiated to end the war, decreeing that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist” in any territories acquired through the war with Mexico.

In 1846, the Wilmot Proviso passed, 83–64, in the House, a vote that fell entirely along sectional rather than party lines. Massachusetts abolitionist and staunch opponent of the war Charles Sumner predicted that the proviso would lead to “a new crystallization of parties, in which there shall be one grand Northern party of Freedom.” Supporters of the Wilmot Proviso argued that slavery and democracy could not coexist. “It is not a question of mere dollars and cents,” said one Wilmot supporter in the House.

It is not a mere political question. It is one in which the North has a higher and deeper stake than the South possibly can have. It is a question whether, in the government of the country, she shall be borne down by the influence of your slaveholding aristocratic institutions, that have not in them the first element of Democracy.34

Members of Congress shook their fists. Southerners narrowed their eyes at northerners; northerners glared back at them. Men on both sides of the aisle stamped their feet. And the ground beneath the Capitol began to shake.

And yet, as different as were Wilmot’s interests from Calhoun’s, they were both interested in the rights of white men, as Wilmot made plain. “I plead the cause of the rights of white freemen,” he said. “I would preserve for free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slavery brings upon free labor.”35

Protests against the war, as a war of aggression, and against the extension of slavery, as an injustice to black people, were sounded not from the elegantly carpeted floor of Congress but from pulpits and pews built of rough-hewn oak. Theodore Parker, a thirty-six-year-old Unitarian minister who had just returned from a tour of Europe, called on Americans to abolish slavery and disavow conquest. “Abroad we are looked on as a nation of swindlers and men-stealers!” he cried. “And what can we say in our defence? Alas, the nation is a traitor to its great idea—that all men are born equal, each with the same inalienable rights.” Parker called for a revolution in the name of the nation and in the name of God, in the spirit of the nation’s founding, and of its founding ideas.

“We are a rebellious nation; our whole history is treason; our blood was attainted before we were born; our Creeds are infidelity to the Mother church; our Constitution treason to our Father-land. What of that? Though all the Governors in the world bid us commit treason against Man, and set the example, let us never submit. Let God only be a Master to control our Conscience!”36

From the stillness of Walden Pond, Henry David Thoreau heeded that call to conscience. He refused to pay his taxes, in protest of the war. In 1846, he left the cabin where he’d listened to whip-poor-wills sing Vespers, and went to jail. In an essay on civil disobedience, he explained that, in a government of majority rule, men had been made into unthinking machines, spineless, and less than men, unwilling to cast votes of conscience. (Of the democracy of numbers, he asked, searchingly, “How many men are there to a square thousand miles in this country? Hardly one.”) Prison, he said, was “the only house in a slave-state in which a free man can abide with honor.”37 When Emerson asked him why he had gone to jail, Thoreau is said to have answered, “Why did you not?” But Emerson had his own misgivings:

Behold the famous States

Harrying Mexico

With rifle and with knife!38

With that rifle and with that knife, Americans would soon begin to carve up their own country.

II.

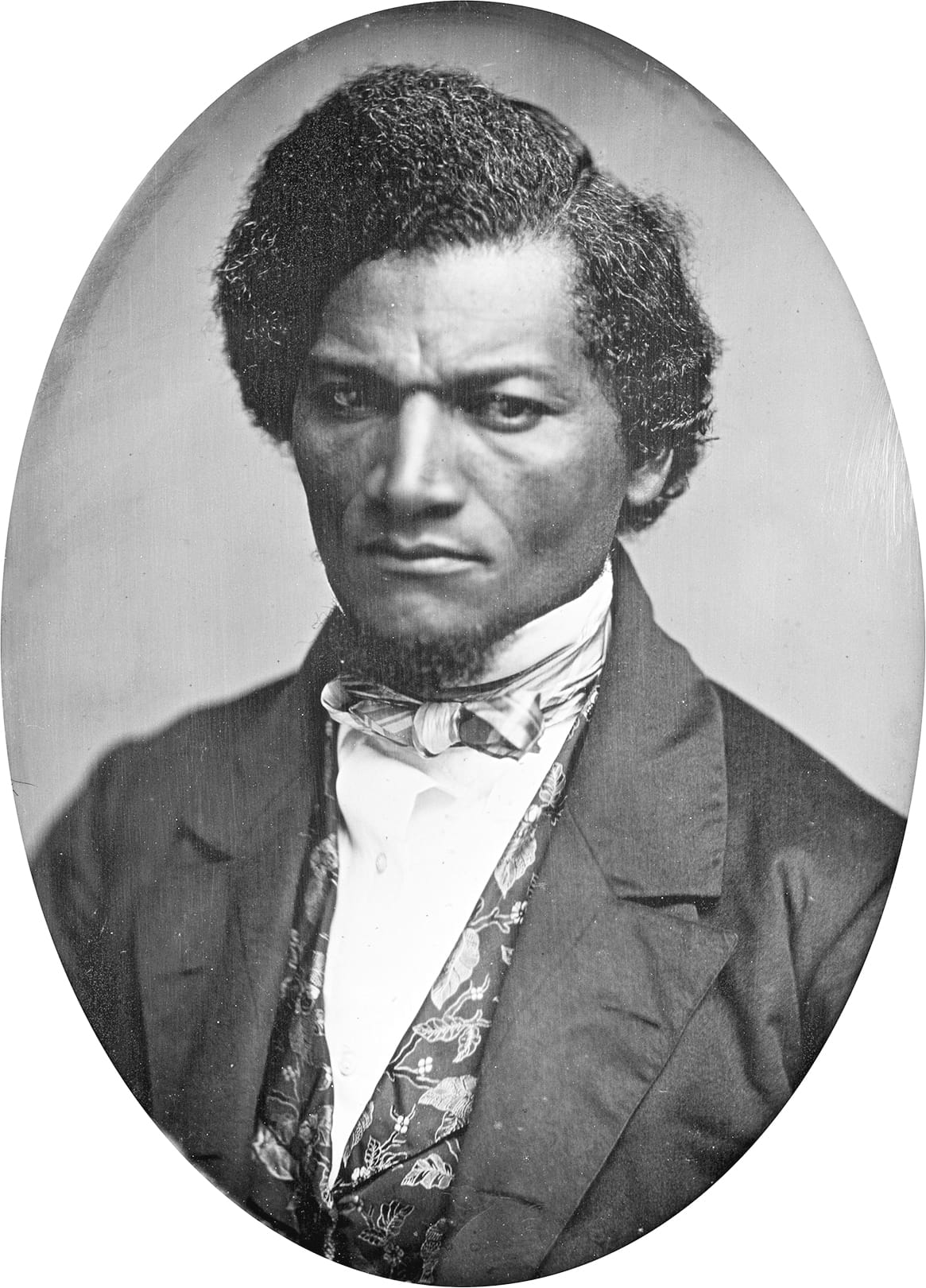

FREDERICK DOUGLASS SAT for his first photograph in 1841. He was twenty-three. He wore a dark suit with a stiff white collar and a polka-dotted tie. His skin was sepia, his hair black, his expression resolute. He stared straight into the camera. Born in Maryland in 1818, Douglass had taught himself to read and write from scraps of newspaper and old spelling books, and studied oratory on the sly. He escaped from slavery in 1838, disguised as a sailor. Living in New England, he began reading William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator. Three years later, he spoke for the first time at an antislavery meeting, on Nantucket. “Have we been listening to a thing, a piece of property, or to a man?” Garrison had asked, when he took the stage after Douglass finished speaking. “A man! A man!” came the cry from the crowd.39 But Douglass provided his own testament, sitting for a daguerreotype, the ocular proof, eyeing the camera: I am a man.40

In the 1840s, Douglass became one of the nation’s best-known speakers. In 1843 alone, he had more than one hundred speaking engagements. He spoke with force and eloquence. His bearing rivaled that of the greatest Shakespearean actors. Garrison wished Douglass would make himself humbler, and talk plainer, to appear more, that is, like Garrison’s notion of an ex-slave. Bristling at Garrison’s handling, Douglass told his own story and made his own way. In 1845, he published an autobiography that, by revealing details of his origins, exposed him to fugitive slave catchers and imperiled his life; he left the country. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass was translated into French, German, and Dutch. Douglass, speaking in Europe, became the most famous black person in the world.41 After buying his freedom, he returned to the United States in 1847 and started a newspaper, the North Star. Its motto and creed: “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren.”42

In the North Star, Douglass called for an immediate end to the war with Mexico. “We beseech our countrymen to leave off this horrid conflict, abandon their murderous plans, and forsake the way of blood,” he urged. “Let the press, the pulpit, the church, the people at large, unite at once; and let petitions flood the halls of Congress by the million, asking for the instant recall of our forces from Mexico.”43 Douglass, who had faith in the power of photography, had faith in other technologies, too. Douglass believed that the great machines of the age were ushering in and accelerating an era of political revolution, of which protest of the war formed only one small part. “Thanks to steam navigation and electric wires,” he wrote, “a revolution cannot be confined to the place or the people where it may commence but flashes with lightning speed from heart to heart.”44

Other observers expected technological forces to work different miracles. As the nation split apart over the war with Mexico, many commentators came to believe that mighty machines could repair the breach. If the problem was the size of the Republic, the sprawl of its borders, the frayed edges of empire, couldn’t railroads, and especially the telegraph, tie the Republic together? “Doubt has been entertained by many patriotic minds how far the rapid, full, and thorough intercommunication of thought and intelligence, so necessary to the people living under a common representative republic, could be expected to take place throughout such immense bounds,” said one House member in 1845, but “that doubt can no longer exist.”45

Samuel Morse’s 1844 demonstration had proven that communication across even so great a distance as the width of the continent could be had in an instant. What hath God wrought? He had wrought, among other things, a wire service. Lawrence Gobright, the Associated Press’s clear-eyed Washington correspondent, determined to use the new wire service to inform Americans of goings-on in Congress: “My business is to communicate facts,” Gobright wrote about his barebones style. “My instructions do not allow me to make any comment upon the facts which I communicate.”46 But, for all the utopianism of Douglass and for all Gobright’s worthiness, even Americans with an unflinching faith in machine-driven progress understood that a pulse along a wire could not stop the slow but steady dissolution of the Union.

In February 1847, Taylor’s forces defeated a Mexican army commanded by Antonio López de Santa Anna near Monterrey. By summer, Mexico was prepared to negotiate a peace. Even as negotiators were tackling the matter of the border between the two nations, U.S. forces led by General Winfield Scott invaded Mexico City. By September, they had occupied the city. With the Americans wielding this tremendous bargaining power, an “All Mexico” movement arose, its adherents taking the position that the United States ought to acquire all of Mexico. Michigan senator Lewis Cass was among those who opposed this plan, on the grounds that it would be difficult to integrate the citizens of Mexico into the United States. “We do not want the people of Mexico either as citizens or subjects,” Cass said. “All we want is a portion of territory, which they nominally hold, generally uninhabited, or, where inhabited at all, sparsely so.”47

Polk’s ambition seemed limitless. He considered trying to acquire all of Mexico, from 26˚ north all the way to the Pacific. In the end, the line was set at 36˚ north. Mexico held onto Baja California, Sonora, and Chihuahua but, in exchange for $15 million, ceded to the United States more than half of its land. Mexican nationals who remained in that territory were given the choice to cross the new border back into Mexico, retain their Mexican citizenship, or become American citizens “on an equality with that of the inhabitants of the other territories of the United States.” Some 75,000–100,000 Mexicans chose to remain, largely in Texas and California, where, although promised political equality, they faced a growing racial animosity and economic losses, especially as their existing economy—trading and ranching—was replaced by prospecting, commercial agriculture, and industrial production.48

The war formally ended on February 2, 1848, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, under which the top half of Mexico became the bottom third of the United States. The gain to the United States was as great as the loss to Mexico. In 1820, the United States of America had spanned 1.8 million square miles, with a population of 9.6 million people; Mexico had spanned 1.7 million square miles, with a population of 6.5 million people. By 1850, the United States had acquired one million square miles of Mexico, and its population had grown to 23.2 million; Mexico’s population was 7.5 million.49

As the United States swelled, Mexico shrank. Most of the land along the border between the two countries was barren and featureless. When the Joint United States and Mexican Boundary Commission began the work of surveying, its members found it hard even to stay alive: most died by starvation. But the scale of the territory the United States acquired by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was staggering. The Louisiana Purchase had doubled the size of the United States. In gaining territory from Mexico, the United States grew by 64 percent. The Superintendent of the Census, charged with measuring its extent, marveled that the territory comprising the United States had grown to “nearly ten times as large as the whole of France and Great Britain combined; three times as large as the whole of France, Britain, Austria, Prussia, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Holland, and Denmark, together; one-and-a-half times as large as the Russian empire in Europe; one-sixth less only than the area covered by the fifty-nine or sixty empires, states, and Republics of Europe; of equal extent with the Roman Empire or that of Alexander, neither of which is said to have exceeded 3,000,000 square miles.”50

Had the United States, an infant nation, become an empire? And in its imperial reach, would it fall, like Rome? “The United States will conquer Mexico,” Emerson had predicted, “but it will be as the man who swallows the arsenic which brings him down. Mexico will poison us.”51

These dismal fears were on the mind of eighty-year-old John Quincy Adams, hobbled and infirm, who objected to the war, and to the peace, with his dying breath. On February 21, 1848, the day Polk received the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Quincy Adams collapsed in the House of Representatives, very nearly in the middle of giving a speech, a last gasp of opposition to the war and all that it stood for. He died two days later. Young Abraham Lincoln, who’d been there when Quincy Adams fell to the floor, was among the men appointed to make arrangements for the funeral, held in the House of Representatives. Calhoun served as a pallbearer. Until the death of Lincoln, the death of no other statesman was so closely reported, followed, and witnessed, a national pageant. Telegraph lines had only just been completed between Portland, Maine, and Richmond, Virginia, and as far west as Cincinnati; word of Quincy Adams’s death spread faster than the wind. His glass-covered coffin traveled five hundred miles by train, stopping in one city after another, where thousands of Americans lined up to view it in an unprecedented, steam-powered parade of grief. The nation fell into mourning, pondering the awful matter of political poison, and the dread question of disunion.52

III.

HORACE GREELEY HIRED Margaret Fuller as an editor at the New York Tribune in 1844. Fuller, thirty-four, nearsighted and frail, was the most learned woman in the United States, as comfortable writing literary criticism as she was discussing philosophy with Emerson. “Her powers of speech throw her writing into the shade,” Emerson once wrote in his journal.53

Rebukes by the likes of Catherine Beecher, who condemned any woman who spoke in public, had silenced a great many women but not all, and certainly not Fuller or prominent abolitionists like the Grimké sisters. Angelina Grimké, raised in Charleston, South Carolina, and expelled from her church for speaking out against slavery, had written a reply to Beecher, an essay called “Human Rights Not Founded on Sex.” She said, “The investigation of the rights of the slave has led me to a better understanding of my own.”54 Her sister Sarah made the argument historical: “The page of history teems with woman’s wrongs, and it is wet with woman’s tears.”55

Sentiment was not Fuller’s way; debate was her way. She was a scourge of lesser intellects. Edgar Allan Poe, whose work she did not admire, described her as wearing a perpetual sneer. In “The Great Lawsuit: Man versus Men, Woman versus Women,” Fuller argued that the democratization of American politics had cast light on the tyranny of men over women: “As men become aware that all men have not had their fair chance,” she observed, women had become willing to say “that no women have had a fair chance.” Meanwhile, abolition—“partly because many women have been prominent in that cause”—had made urgent the fight for women’s rights. In 1845, in Woman in the Nineteenth Century, Fuller argued for fundamental and complete equality: “We would have every path laid open to Woman as freely as to Man.”56 The book was wildly successful, and Greeley, who had taken to greeting Fuller with one of her catchphrases about women’s capacity—“Let them be sea-captains, if you will”—sent her to Europe to become his newspaper’s foreign correspondent. Fuller was in Rome, where she fell in love and gave birth to a son, when the women’s rights movement was born in earnest in the United States, as part of the political mayhem of the revolutionary year of 1848, a presidential election year.57

Polk had pledged to serve only one term. Democrats struggled to name a replacement. By now, finding a candidate to run for president had become all but impossible; the parties were national, but, given that politics had become sectional, what man could attract voters in both the North and the South?

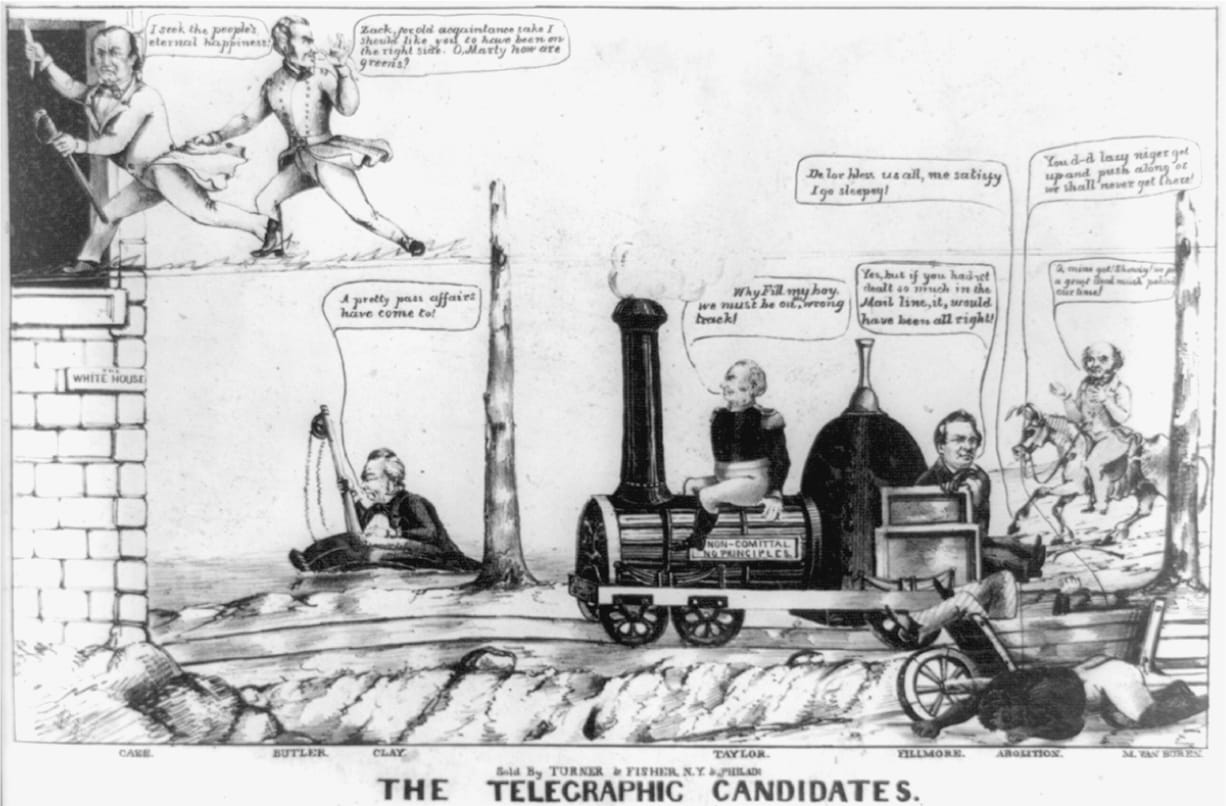

The contenders were decidedly lackluster, the cramped and shortsighted men of a cramped and shortsighted age. One Democratic Party prospect, Pennsylvania lawyer and lifelong bachelor James Buchanan, had served as Polk’s secretary of state. Buchanan favored solving the territorial problem by extending the Missouri Compromise line all the way across the continent. Senator Lewis Cass, who’d served as Jackson’s secretary of war, had a subtler mind. Cass favored a political scheme dubbed, by its supporters, “popular sovereignty,” under which each state ought to decide, on entering the Union, whether it would allow or prohibit slavery. At the party’s nominating convention, Cass prevailed, and delegates chose, as his running mate, William Butler, a general who had served in the War with Mexico with no particular distinction.

Military heroes were the fashion of the political year. The Whig Party courted two of the war’s two better-known generals, Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, casting aside the two aging leaders of the party, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. Taylor had never belonged to a political party; Scott was nearly as mysterious. Taylor only grudgingly agreed to declare himself a Whig. “I am a Whig,” he said, adding, “but not an ultra Whig.” As he himself admitted, he’d never even voted.58 Nevertheless, he won the nomination. Clay, dismayed at the rise of the war heroes, declared, “I wish I could slay a Mexican.”59

The rise of Cass and Taylor left Democrats and Whigs who opposed the extension of slavery into the territories without a candidate. They bolted and, at a convention held in Buffalo in June of 1848, formed the Free-Soil Party. Casting about in desperation for a man with a national reputation, they settled on ex-president Martin Van Buren and adopted as their motto “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men!”60

The Free-Soil, Free-Speech movement came out of the dispute over the interpretation of the Constitution, but it was also tied to revolutions that convulsed Europe in 1848. Margaret Fuller filed reports from Italy, where she nursed fallen revolutionaries in a hospital in Rome. Reeling from those revolutions, the king of Bavaria asked the historian Leopold von Ranke to explain why his people had rebelled against monarchial rule, as had so many peoples in Europe that year. “Ideas spread most rapidly when they have found adequate concrete expression,” Ranke told the king, and the United States had “introduced a new force in the world,” the idea that “the nation should govern itself,” an idea that would determine “the course of the modern world”: free speech, spread by wire, would make the whole world free.61

Unlike the predominant U.S. response to the Haitian revolution, most Americans, following Margaret Fuller, greeted the revolutions in Europe as democratic revolutions, the people rising up against the tyranny of aristocracy and monarchy. Marx’s Communist Manifesto, published that year, was hardly read, and soon forgotten (only to be rediscovered decades later). But it captured a sentiment that coursed across the American continent: the workers had lost control of the means of production.

People who rallied behind “free labor” insisted on the moral superiority of yeoman farming and wage work over slave labor. But the language of the struggle between labor and capital suffused free labor ideology. “Labor is prior to, and independent of capital,” Lincoln said in 1859, and “in fact, capital is the fruit of labor.”62 But the battle, for Free-Soilers, wasn’t really between labor and capital; it was between free labor (the producing classes) and the slave power (American aristocrats). The Free-Soil movement enjoyed its strongest support in two particular sorts of middling classes: laboring men in eastern cities and farming men in western territories. If it sounds, in retrospect, like Marx, its rhetoric in fact borrowed from the nature writings of Emerson and Thoreau. Unlike Thoreau, who cursed the railroads, Free-Soilers believed in improvement, improvement through the hard work of the laboring man, his power, his energy. “Our paupers to-day, thanks to free labor, are our yeoman and merchants of tomorrow,” the New York Times boasted. “Why, who are the laboring people of the North?” Daniel Webster asked. “They are the whole North. They are the people who till their own farms with their own hands, freeholders, educated men, independent men.” As laboring men moved westward, they carried this spirit with them, so long as they founded free states. The governor of Michigan argued, “Like most new States, ours has been settled by an active, energetic, and enterprising class of men, who are desirous of accumulating property rapidly.”63

Free-Soilers and their bedfellows spoke of “Northern Progress and Southern Decadence,” comparing the striving, energetic, and improving work of free labor to the corruption, decadence, and backwardness of slavery. Slavery reduced a man to “a blind horse upon a tread-mill,” said Lincoln. Slavery had left the South in ruins, wrote New York senator William Seward: “An exhausted soil, old and decaying towns, wretchedly-neglected roads.” As Horace Greeley put it, “Enslave a man and you destroy his ambition, his enterprise, his capacity.”64

This attack by northerners led southerners to greater exertions in defending their way of life. They battled on several fronts. They described northern “wage slavery” as a far more exploitative system of labor than slavery. They celebrated slavery as fundamental to American prosperity. Slavery “has grown with our growth, and strengthened with our strength,” Calhoun said. And they elaborated an increasingly virulent ideology of racial difference, arguing against the very idea of equality embodied in the American creed.

Some of these ideas came from the field of ethnology. The Swiss-born American naturalist Louis Agassiz advocated “special creation,” the idea that God had created and distributed all the world’s plants and animals separately, and strewn them across the lands and the seas, each to its proper place. With proslavery southerners, Agassiz also subscribed to polygenesis, the theory that God had created four different races, each in a separate Garden of Eden. But, as Frederick Douglass observed, slavery lay “at the bottom of the whole controversy,” since the dispute between polygenists and monogenists was, at heart, a debate “between the slaveholders on the one hand, and the abolitionists on the other.”65

Conservative Virginian George Fitzhugh, himself inspired by ethnological thinking, dismissed the “self-evident truths” of the Declaration of Independence as utter nonsense. “Men are not born physically, morally, or intellectually equal,” he wrote. “It would be far nearer the truth to say, ‘that some were born with saddles on their backs, and others booted and spurred to ride them,’—and the riding does them good.” For Fitzhugh, the error had begun in the imaginations of the philosophes of the Enlightenment and in their denial of the reality of history. Life and liberty are not “inalienable rights,” Fitzhugh argued: instead, people “have been sold in all countries, and in all ages, and must be sold so long as human nature lasts.” Equality means calamity: “Subordination, difference of caste and classes, difference of sex, age, and slavery beget peace and good will.” Progress is an illusion: “the world has not improved in the last two thousand, probably four thousand years.” Perfection is to be found in the past, not in the future.66 As for the economic systems of the North and the South, “Free laborers have not a thousandth part of the rights and liberties of negro slaves,” Fitzhugh insisted. “The negro slaves of the South are the happiest, and, in some sense, the freest people in the world.”67

The Free-Soil Party opposed every single one of Fitzhugh’s claims. And, if it drew support from farmers and laborers, it also earned the loyalty of free blacks. To support the party, Henry Highland Garnet, a black abolitionist in Troy, New York, reprinted David Walker’s Appeal. The party held its first convention in Buffalo in the summer of 1848. Salmon Chase drafted the party’s platform, which very closely followed Chase’s interpretation of Madison’s Notes. The Constitution couldn’t be rejected, Chase argued, it had to be reclaimed. His key ideas, he explained, were three: “1. That the original policy of the Government was that of slavery restriction. 2. That under the Constitution Congress cannot establish or maintain slavery in the territories. 3. That the original policy of the Government has been subverted and the Constitution violated for the extension of slavery, and the establishment of the political supremacy of the Slave Power.”68

The Free-Soil Party had also drawn the support of women who’d been involved in the temperance and abolition movements, and who’d campaigned on behalf of the Whig Party in 1840 and 1844. On the heels of the Free-Soil convention in Buffalo, three hundred women and men held a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Margaret Fuller was still in Italy, but it was her work that had served as a catalyst.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, thirty-two, drafted a manifesto. The daughter of a New York Supreme Court Justice, Stanton had grown up reading her father’s lawbooks. Earlier that spring, she’d been instrumental in securing the passage of a state Married Women’s Property Act. Under most existing state laws, married women could not own property or make contracts; anything they owned became their husbands’ upon marriage; the New York law allowed women “separate use” of their separate property. Stanton, whose husband, also a lawyer, would help found the Republican Party, was also a noted abolitionist. As Fuller had pointed out, the migration of abolitionism into party politics illustrated to women just how limited was their capacity to act politically when they could not vote. The women who gathered at Seneca decided to fight for all manner of legal reform and, controversially, for the right to vote. They felt, Stanton later wrote, “as helpless and hopeless as if they had been suddenly asked to construct a steam engine.”

Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments did not merely call for piecemeal legislative reform but instead echoed the Declaration of Independence:

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

And on it went. “The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her,” Stanton wrote. “To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.” Man took woman’s property, passed laws in which she had no voice, subjected her to taxation without representation, denied her an education, made her a slave to his will, forbade her from speaking in public, and denied her the right to vote.69 One Whig newspaper called the convention “the most shocking and unnatural incident ever recorded in the history of womanity.”70 But nothing so weak as ridicule ever stopped Stanton, who refused to let the battle over the meaning of the Constitution be settled by men alone.

Margaret Fuller, the most accomplished American woman of the century, would miss that battle. With her babbling, toddling nearly two-year-old son and his father, and with the manuscript of her epic history of the revolution in Rome wrapped in a blue calico bag tucked into a portable wooden desk, she left Italy in 1849 and set sail for New York. Less than three hundred yards from the shore of Fire Island and mere miles from New York City, their ship ran aground on a sandbar in a raging storm. Other passengers pried planks from the deck of the ship and, using them as rafts, made their way to shore. Fuller, who was terrified of water and unwilling to let go of her baby, sat on the deck in a white nightdress and waited for a lifeboat from the island lighthouse while the ship beneath her broke to pieces, its masts splintering, its rigging whipping in the wind. A wave crashed over her and she was plunged into the fearsome sea.

Thoreau came from Massachusetts to comb the beach in search of her remains or any of her pages. Only the tiny bare body of her baby was ever found.71

IV.

HISTORY TEEMS WITH mishaps and might-have-beens: explosions on the Potomac, storms not far from port, narrowly contested elections, court cases lost and won, political visionaries drowned. But over the United States in the 1850s, a sense of inevitability fell, as if there were a fate, a dismal dismantlement, that no series of events or accidents could thwart.

Near the end of 1849, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, despairing for the Union, composed a poem about the American ship of state. Long-fellow, born by the sea in Portland, Maine, in 1807, was America’s best-known and best-loved poet. He was also the beloved and passionately loyal friend of six-foot-four Charles Sumner, who in the 1840s campaigned against the annexation of Texas and the War with Mexico while fighting against racial segregation in Boston schools. In 1842, Sumner had convinced Longfellow to put his pen to the antislavery cause, and Longfellow had dutifully written and published a little book of Poems on Slavery. Well known for his abolitionist views, Longfellow had in 1844 been urged by the Liberty Party to run for Congress. “Though a strong anti-Slavery man, I am not a member of any society, and fight under no single banner,” he wrote, declining. “Partizan warfare becomes too violent—too vindictive for my taste; and I should be found but a weak and unworthy champion in public debate.”72

By 1849, Longfellow, like most Americans who were paying attention, feared for the Republic. He began writing a poem, called “The Building of the Ship,” about a beautiful, rough-hewn ship called the Union. But as he closed the poem, he could imagine nothing but disaster for this worthy vessel. In his initial draft, he closed the poem with these lines:

. . . where, oh where,

Shall end this form so rare?

. . . Wrecked upon some treacherous rock,

Rotting in some loathsome dock,

Such the end must be at length

Of all this loveliness and strength!

Then, on November 11, 1849, Sumner came to dinner at Longfellow’s house in Cambridge, flushed with excitement about the Free-Soil Party. Sumner was running for Congress as a Free-Soiler; November 12 was Election Day. He convinced Longfellow that the Union might yet be saved, and that he ought to write a more hopeful ending to his poem. Longfellow drafted a revision that night and the next day went to the polls to vote for Sumner. Longfellow’s new ending became one of his most admired verses:

Sail on! Sail on! O Ship of State!

For thee the famished nations wait!

The world seems hanging on thy fate!

He wrote to his publisher, “What think you of the enclosed, instead of the sad ending of ‘The Ship’? Is it better?” It was better. Lincoln’s secretary later said that after Lincoln read Longfellow’s poem, “His eyes filled with tears and his checks were wet. He did not speak for some minutes, but finally said with simplicity, ‘It is a wonderful gift to be able to stir men like that!’”73

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the struggle over slavery that had begun on the shores of the Atlantic had reached the shores of the Pacific—across three thousand miles hatched and crisscrossed with train tracks and telegraph wires. “The Union has been preserved thus far by miracles,” John Marshall had written in 1832. “I fear they cannot continue.” Another miracle, it seemed, was needed in 1850. The discovery of gold in California had led to a gold rush. Migrants came from the east, from neighboring Oregon, from Mexico, and from parts elsewhere, unimaginably far, even from Chile and China. In 1849, a California constitutional convention decreed that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in the State.” (A resolution to prohibit “free negroes” from settling in the state was defeated.) With a constitution ratified by voters in the fall of 1849, the request to enter the Union went to Congress.74

It must have felt like living on a seesaw. Admitting California as a free state would have toppled the precarious balance between slave and free states. Congress seemed at an impasse. But over eight months of close negotiation, Henry Clay, much aided by Illinois senator Stephen Douglas, a short, brawny bulldog of a man, brokered a compromise or, rather, a series of compromises, involving a set of issues related to slavery. To appease Free-Soilers, California would be admitted as a free state; the slave trade would be abolished in Washington, DC; and Texas would yield to New Mexico a disputed patch of territory, in exchange for $10 million. (John C. Frémont, an opponent of slavery, was elected California’s first senator.) To appease those who favored slavery, the territories of New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah would be organized without mention of slavery, leaving the question to be settled by the inhabitants themselves, upon application for statehood. Douglas promoted the idea of popular sovereignty, proclaiming, “If there is any one principle dearer and more sacred than all others in free governments, it is that which asserts the exclusive right of a free people to form and adopt their own fundamental law.”75

Unfree people, within Stephen Douglas’s understanding, had no such rights. The final proslavery element of the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Law, required citizens to turn in runaway slaves and denied fugitives the right to a jury trial. The law, said Harriet Jacobs, a fugitive slave living in New York, marked “the beginning of a reign of terror to the colored population.”76 Bounty hunters and slave catchers hunted down and captured former slaves and returned them to their owners for a fee. Little stopped them from seizing men, women, and children who had been born free, or who had been legally emancipated, and selling them to the South, too. Nothing so brutally exposed the fragility of freedom or the rapaciousness of slavery. “If anybody wants to break a law, let him break the Fugitive-Slave Law,” Longfellow wrote bitterly. “That is all it is for.”77

Harriet Tubman, who’d first run away when she was only seven years old, helped build a new American infrastructure: the Underground Railroad. Tubman, five feet tall, had been beaten and starved—a weight thrown at her head had left a permanent dent—but had escaped bondage in 1849, fleeing from Maryland to Philadelphia. Beginning in 1850, she made at least thirteen trips back into Maryland to rescue some seventy men, women, and children, while working, in New York, Philadelphia, and Canada, as a laundress, housekeeper, and cook. People took to calling her “Captain Tubman” or, more simply, “Moses.” Once, asked what she would do if she were captured, she said, “I shall have the consolation to know that I had done some good to my people.”78

The Compromise of 1850 lasted for barely four years, but in the interim it transformed the abolitionist movement and, once again, realigned the parties. In 1851, Charles Sumner, running as a Free-Soiler, won the Massachusetts senate seat long held by Daniel Webster, architect of the compromise that Sumner despised. That same year, Frederick Douglass broke with Garrison on the question of the Constitution. “I am sick and tired of arguing on the slaveholders’ side,” Douglass said. He had come to believe that the Constitution did not sanction slavery and could be used to end it.79 “At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed,” Douglass said bitterly, in a blistering speech he delivered in Rochester on July 5, 1852. “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?” he asked.

I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.80

But even as Douglass called on Americans to realize the promise of the nation’s founding documents, expansion to the West led to still more staggering constitutional distortions and moral contortions.

In 1854, the seesaw tipped once more, pressed down, on the proslavery end, by Stephen Douglas, who served as chair of the Senate’s Committee on Territories. Congress had been talking about plans for a transcontinental railroad since the 1830s. Douglas wanted the railroad to go through Chicago. But between Chicago and the Pacific stood the so-called Permanent Indian Territory, the land to which Andrew Jackson had removed eastern Indians, including the Cherokees. Douglas argued that, in an age of improvement, in the country of the future, the very notion of a Permanent Indian Territory was absurd: “The idea of arresting our progress in that direction has become so ludicrous that we are amazed, that wise and patriotic statesmen ever cherished the thought. . . . How are we to develop, cherish, and protect our immense interests and possessions on the Pacific, with a vast wilderness fifteen hundred miles in breadth, filled with hostile savages, and cutting off all direct communication? The Indian barrier must be removed.”81

When a bill organizing the Permanent Indian Territory into Kansas and Nebraska was introduced into Congress in January of 1854, Douglas proposed an amendment that amounted to a repeal of the Missouri Compromise, which would have prohibited slavery from both territories. Instead, in accordance with the principle of popular sovereignty, the people of Kansas and Nebraska would decide. The Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively opened to slavery land that had previously been closed to it. Its consequences represented, to many northerners, an outrageous betrayal of the Constitution itself. New York senator Preston King predicted that “past lines of party will be obliterated with the Missouri line.” Maine senator Hannibal Hamlin declared, “The old Democratic party is now the party of slavery.”82

So far from serving as a safety value with which to release the pent-up pressure of the growing American population, expansion into the West had proved explosive. The Kansas-Nebraska controversy made the Democratic Party into the party of slavery, and it spelled the end of the American Party, also known as the Know-Nothing Party. The Know-Nothings had pledged never to vote for any foreign-born or Catholic candidate and campaigned for extending the period of naturalization to twenty-one years. They’d won control of the Massachusetts legislature and over 40 percent of the vote in Pennsylvania. One Pennsylvania Democrat said, “Nearly everybody seems to have gone altogether deranged on Nativism.” In New York, Samuel F. B. Morse ran for Congress as a Know-Nothing and lost, but he spread his message by reprinting his nativist tract Imminent Dangers and began arguing that abolitionism was itself a foreign plot, a “long-concocted and skillfully planned intrigue of the British aristocracy.”83 (“Slavery per se is not a sin,” Morse insisted. “It is a social condition ordained from the beginning of the world for the wisest purposes, benevolent and disciplinary, by Divine Wisdom.”)84 In February 1854, at their convention in Philadelphia, northern Know-Nothings proposed a platform plank calling for the reinstatement of the Missouri Compromise. When that motion was rejected, some fifty delegates from eight northern states bolted: they left the convention, and the party, to set up their own party, the short-lived North American Party. Nativism would endure as a force in American politics, but, meanwhile, nativists split over slavery.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act also drew forty-five-year-old Abraham Lincoln out of his law practice and back into politics. As a member of the House, Lincoln had opposed the war with Mexico and supported the Wilmot Proviso, but he’d hardly spoken about slavery. In the spring of 1854, he began meditating on the institution of slavery and, like a lawyer preparing for court, weighing possible arguments with which to defeat those who defended the institution. In a fragment written in April, he anticipated a line of debate:

If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?—

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly? You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest; you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.85

Lincoln found a political home in a new political party, the Republican Party, founded in May 1854, in Ripon, Wisconsin, by fifty-four citizens determined to defeat the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Three of those fifty-four citizens were women. Their new party drew a coalition of former Free-Soilers, Whigs, and northern Democrats and Know-Nothings who opposed slavery. If the Democratic Party had become the party of slavery; the Republican Party would be the party of reform. In that spirit, it welcomed the aid of women: women wrote Republican campaign literature and made speeches on behalf of the party. One of the party’s best, and best-paid, speakers was Anna Dickinson, who became the first woman to speak in the Hall of the House of Representatives.86

Joining the new party, Lincoln wrestled with the implications of the speeches and writing of far-seeing Frederick Douglass, who had staked the fundamental case against slavery in the common humanity of all people. In August 1854, still working out his best line of argument, Lincoln began speaking at political meetings. That fall, campaigning as a Republican, he decided to challenge Stephen Douglas for his seat in the Senate. He debated Douglas in Peoria before a fascinated crowd. Douglas spoke for three hours and then, after a dinner break, Lincoln spoke for just as long. Lincoln argued that what Douglas advocated was an abomination of the idea of democracy. The matter depended on whether “the negro is a man,” Lincoln said.

If he is not a man, why in that case, he who is a man may, as a matter of self-government, do just as he pleases with him. But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself, that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.

For this, for making democracy into the abomination of despotism, he said he hated the Kansas-Nebraska Act:

I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

Lincoln’s was the language of free soil, free speech, and free labor. He grounded his argument against slavery in his understanding of American history, in the language of Frederick Douglass, and in his reading of the Constitution. “Let no one be deceived,” he said. “The spirit of seventy-six and the spirit of Nebraska, are utter antagonisms.”87

Lincoln lost the race. And still he kept at work, refining his argument, as if he were hewing a log, cutting it into boards, and sanding them. “Most governments have been based, practically, on the denial of equal rights of men,” he wrote, in a note to himself. “Ours began, by affirming those rights. . . . We made the experiment; and the fruit is before us. Look at it—think of it. Look at it, in its aggregate grandeur, of extent of country, and numbers of population—of ship, and steamboat, and rail.88

Kansas, left to decide whether it would enter the Union as a free or a slave state, broke out in outright war. Southerners moved into Kansas to vote for slavery; northerners moved into Kansas to vote against it. Eventually, they began shooting one another. Horace Greeley dubbed it “Bleeding Kansas.” Soon there would be blood on the Senate floor. Lincoln privately confided his despair about what he described as the nation’s “progress in degeneracy,” a political regression:

As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.89

In May of 1856, Charles Sumner delivered from his desk in the Senate a thundering speech called “The Crime Against Kansas,” indicting the barbarism of slavery, comparing slavery to rape (and intimating that all slave owners raped their slaves), and warning of a civil war. “Even now, while I speak,” Sumner shouted, “portents lower in the horizon, threatening to darken the land, which already palpitates with the mutterings of civil war.” Two days later, Congressman Preston Brooks, a cousin of South Carolina senator Andrew Butler, who had cowritten the Kansas-Nebraska Act with Stephen Douglas, approached Sumner while Sumner was sitting at his desk on the Senate floor. “Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully,” Brooks told Sumner. “It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.” Not waiting for a reply, Brooks then beat Sumner mercilessly with his cane, thwacking him on the head again and again. Longfellow, who had been quietly doing his own part in the fight against slavery—buying the freedom of fugitive slaves and funding free schools—wrote to Sumner to tell him that he was “the greatest voice on the greatest subject that had been uttered since we became a nation.”90 It would take Sumner more than three years to recover from his head injuries. In all that while, Massachusetts refused to elect a replacement, leaving his Senate seat empty.

“The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere,” the Cincinnati Gazette argued.91 But what Brooks’s caning of Sumner illustrated best was that the battle over slavery was a battle over the West. In the 1856 election, the Republican Party, incorporating Free-Soilers and acknowledging the growing political power of the West, nominated the Californian and famed explorer John C. Frémont for president, and only narrowly voted down Lincoln for vice president. The party adopted the slogan: “Free Speech, Free Soil, and Frémont!” It included on its platform opposition to the idea that slavery could be left to the states: “We deny the authority of Congress, of a Territorial Legislature, of any individual or association of individuals, to give legal existence to slavery in any Territory of the United States, while the present Constitution shall be maintained.”92

Frémont, however, proved a lackluster campaigner. As more than one Republican pointed out, his wife, the formidably eloquent Jesse Benton Frémont, “would have been the better candidate.”93 The Whigs nominated the unmemorable Millard Fillmore, the president of their nominating convention declaring, “It has been preached that the Whig party is dead, but it is not so.” He was wrong. The Whigs really were dead. In 1856, Democrats decided their best chance of winning an election was nominating a proslavery northerner, and chose James Buchanan. Polk once confided in his diary, “Mr. Buchanan is an able man, but in small matters without judgment and sometimes acts like an old maid.”94 A man of limited imagination, Buchanan’s sole political virtue was the appearance of evenhandedness: during the maelstrom of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, he had been serving as ambassador to Great Britain, which made him appear, to American voters, unstained, as if a vote for Buchanan were a vote for union. In the general election, Buchanan campaigned by arguing that electing Frémont, a known opponent of the extension of slavery to the territories, would lead to a civil war; he won by a landslide.