Eight

THE FACE OF BATTLE

APHOTOGRAPH STOPS TIME, TRAPPING IT LIKE A BUTTERFLY in a jar. No other kind of historical evidence has this quality of instantaneity, of an impression taken in a moment, in a flicker, an eye opened and then shut. Photographs also capture the ordinary, the humble, the speechless. The camera discriminates between light and dark but not between the rich and the poor, the literate and the illiterate, the noisy and the quiet. The emergence of photography altered the historical record. It also shaped the course of American history.

In March of 1839, during a trip to Europe to promote his telegraph, Samuel Morse visited the Parisian studio of the painter Louis Daguerre, fellow artist, fellow inventor. Two months before, Daguerre had presented to the French Academy of Sciences the results of experiments in which he took pictures by exposing to light polished, silver-coated copper sheets in the presence of the vapor of iodine crystals. The result was spectacular, an uncanny, ghostly likeness. In April, Morse wrote a letter home to his brother Sidney, editor of the New York Observer, describing Daguerre’s invention as “one of the most beautiful discoveries of the age.”1

The first photograph seen in the United States would be displayed eight months later in a Broadway hotel in New York. Studios soon opened in cities and towns across the country, where photographers, adapting to a fast-changing technology, made portraits of copper (called daguerreotypes), of glass (ambrotypes), and of iron (tintypes). The art spread quickly; by the 1840s and 1850s, twenty-five million portraits were taken in the United States. Ordinary people couldn’t afford a painted portrait, but nearly everyone could afford a photograph; it became a technology of democracy. “Talk no more of ‘holding the mirror up to nature,’” wrote one newspaper editor. “She will hold it up to herself, and present you with a copy of her countenance for a penny.”2 They were “so life-like they almost speak,” people said, but portraits were also closely associated with death, with being trapped in time, on glass, for eternity, and, even more poignantly, with equality.3 With photography, Walt Whitman predicted, “Art will be democratized.”4

Frederick Douglass, an early convert, became a theorist of photography. “Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists,” he said. “It seems to us next to impossible for white men to take likenesses of black men, without most grossly exaggerating their distinctive features.” But a photograph was no caricature. Douglass therefore sat, again and again, in a portraitist’s studio: he became the most photographed man in nineteenth-century America, his likeness taken more often than Twain or even Lincoln. Douglass believed both that photography would set his people free by telling the truth about their humanity and that photography would help realize the promise of democracy by capturing rich and poor alike. “What was once the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now the privilege of all,” he said. “The humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase fifty years ago.” Technological progress, he predicted, would usher in an age of equality, justice, and peace:

The growing inter-communication of distant nations, the rapid transmission of intelligence over the globe—the worldwide ramifications of commerce—bringing together the knowledge, the skill, and the mental power of the world, cannot but dispel prejudice, dissolve the granite barriers of arbitrary power, bring the world into peace and unity, and at last crown the world with justice, liberty, and brotherly kindness.5

But by then, the daguerreotype had been abandoned in favor of the paper print, set aside, one Philadelphian remarked, “like a dead language, never spoken, and seldom written.”6 And Americans would be fighting a war one against another, the first war whose devastation was captured by photography: fields of Union and Confederate soldiers, caught in the trap of time, in black and white.

I.

EVEN AS THE Union was falling apart, Americans indulged in the fantasy that technology could hold it together, and, not only that, but that technology could bind all of the peoples of the world to one another. On September 1, 1858, New Yorkers held a parade celebrating the completion of a cable stretching across the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. “SEVERED JULY 4, 1776,” read one banner, “UNITED AUGUST 12, 1858.” Fifteen thousand people marched from the Battery through the city, past Barnum’s Museum, where the flags of Britain and the United States were tied together by telegraph wire. “Never before was anything purely human done in the history of the world and the race which stood for One-ness as the successful laying of the Atlantic Cable does!” cried one speaker. “We have hitherto lived in a hemisphere, and we now live on a globe—live not by halves, but as a whole—not as scattered members, but as the connected limbs of one organic body, the great common humanity.”7

Morse had long predicted that the telegraph would usher in an age of world peace. “I trust that one of its effects will be to bind man to his fellow-man in such bonds of amity as to put an end to war,” he insisted.8 War was a failure of technology, Morse argued, a shortcoming of communication that could be remedied by way of a machine. Endowing his work with the grandest of purposes, he believed that the laying of telegraph wires across the American continent would bind the nation together into one people, and that the laying of cable across the ocean would bind Europe to the Americas, ushering in the dawn of an age of global harmony. And the telegraph did introduce radical changes into American life. By 1858, Chicago’s Board of Trade was posting grain prices from all over the continent. The nation was tied together by 50,000 miles of wire, 1,400 stations, and 10,000 telegraph operators.9 But war isn’t a failure of technology; it’s a failure of politics.

In the summer of 1858, while New Yorkers were celebrating the laying of the Atlantic cable (a cable that, not long afterward, failed), the people of Illinois witnessed a different and more ancient kind of communication: debate. The debates staged that year between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas proved to be the greatest argument over the American experiment since the constitutional convention. Those debates didn’t avert the coming war between the states, but they illustrate, better than any other part of the historical record of a cloven time, the nature of the disagreement.

Debate is to war what trial by jury is to trial by combat: a way to settle a dispute without coming to blows. The form and its rules had been established over centuries. They derived from rules used in the courts and in Parliament, and even from the rules of rhetoric used in the writing of poetry. Since the Middle Ages and the founding of the first universities, debate had been the foundation of a liberal arts education. (Etymologically and historically, the artes liberales are the arts acquired by people who are free, or liber.)10 In the eighteenth century, debate was understood as the foundation of civil society. In 1787, delegates to the constitutional convention had agreed to “to argue without asperity, and to endeavor to convince the judgment without hurting the feelings of each other.” Candidates for office debated face-to-face. With the expansion of the franchise, debating spread: beginning in the 1830s, debating classes were offered to ordinary citizens as a form of civic education. Debating societies popped up in cities and even the smallest of towns, where anyone who could vote was expected to know how to debate, although this meant, in turn, that anyone who couldn’t vote was expected not to debate. (Women, who couldn’t vote, were not allowed to debate in public, and when they did, it was considered scandalous. In 1837, when Angelina Grimké agreed to debate two men, the local newspaper refused to publish the results.)11 Still, that didn’t stop people who couldn’t vote from studying argument. Frederick Douglass, as a boy of twelve, and while still a slave, read the debates in a schoolbook called The Columbian Orator, which included a “Dialogue between a Master and Slave”:

MASTER: You were a slave when I fairly purchased you.

SLAVE: Did I give my consent to the purchase?

MASTER: You had no consent to give. You had already lost the right of disposing of yourself.

SLAVE: I had lost the power, but how the right? I was treacherously kidnapped in my own country. . . . What step in all this progress of violence and injustice can give a right?12

Studying this debate, Douglass had first begun to ask himself these questions: “Why are some people slaves, and others masters? Was there ever a time when this was not so?”13 Douglass escaped slavery, but he also defeated his bondage by argument.

Banned in Congress under the gag rule, open debate about slavery nevertheless took place elsewhere—in 1855, in Connecticut, the southern aristocrat George Fitzhugh debated the abolitionist Wendell Phillips on the question of “The Failure of Free Society”—but it was uncommon.14 That made the debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas all the more remarkable.

Lincoln and Douglas had given speeches back-to-back in 1854, during the Kansas-Nebraska crisis; but they’d never faced each other. In the spring and early summer of 1858, Lincoln, running for a U.S. Senate seat held by Douglas, had been following Douglas from campaign stop to campaign stop, listening to him speak and then speaking to the same crowd the next day, or even later on the same day, which gave Lincoln the last word but left him with a much smaller audience, since Democrats seldom stayed to listen to him. Lincoln’s supporters urged him to challenge Douglas: “Let him act the honorable part by agreeing to meet you in regular Debate, giving a fair opportunity to all to hear both sides.” On July 24, Lincoln wrote to his political rival, inviting him to debate: “Will it be agreeable to you and myself to divide time and address the same audiences?” Douglas, with some reluctance, agreed.15

Some twelve thousand people showed up for their first debate, at two o’clock in the afternoon on August 21, in Ottawa, Illinois. There were no seats; the audience stood, without relief, for three hours. The two men, standing together on a stage, looked as though they might have been displayed together in Barnum’s Museum: Lincoln, six foot four and as straight as a tree, Douglas, a full foot shorter, his whole body clenched as tight as a fist. They’d agreed to strict rules: the first speaker would speak for an hour and the second for an hour and a half, whereupon the first speaker would offer a thirty-minute rebuttal.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Douglas began, “we are present here to-day for the purpose of having a joint discussion, as the representatives of the two great political parties of the State and Union, upon the principles in issue between those parties.”

The audience was as rapt as it was rowdy. “Hit him again!” the crowd cried, when Douglas scored a point against Lincoln. Douglas reminded his audience of Lincoln’s opposition to the Dred Scott decision.

“I ask you, are you in favor of conferring upon the negro the rights and privileges of citizenship?” he called to the crowd.

“No, no!” came the reply.

The debate turned on the interpretation offered by the two men, and by their parties, of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Douglas argued that Lincoln misread the Declaration of Independence if he believed that it applied to blacks as well as whites. “This Government was made by our fathers on the white basis,” Douglas said. “It was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever.” As to the institution of slavery, that was up to the electorate, Douglas insisted: “I care more for the great principle of self-government, the right of the people to rule, than I do for all the negroes of Christendom.”

Douglas charged Lincoln with being a zealot. This Lincoln denied. “I will say here, that I have no purpose directly or indirectly to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists,” he said when he took the stage. “I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” He contested Douglas’s assertion that he, Lincoln, believed in the equality of the races. “I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races,” he said. “But I hold that, notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The crowd cheered. “I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man,” he added, to another round of cheers.

Douglas argued that claiming that blacks were included in the Declaration of Independence amounted to slandering Jefferson. Lincoln replied (calling Douglas, a former Illinois Supreme Court justice, “Judge”):

I believe the entire records of the world, from the date of the Declaration of Independence up to within three years ago, may be searched in vain for one single affirmation, from one single man, that the negro was not included in the Declaration of Independence; I think I may defy Judge Douglas to show that he ever said so, that Washington ever said so, that any President ever said so, that any member of Congress ever said so, or that any living man upon the whole earth ever said so, until the necessities of the present policy of the Democratic party, in regard to slavery, had to invent that affirmation.

As to which of the two men could speak best for Jefferson, Lincoln laid down a gauntlet:

And I will remind Judge Douglas and this audience, that while Mr. Jefferson was the owner of slaves, as undoubtedly he was, in speaking upon this very subject, he used the strong language that “he trembled for his country when he remembered that God was just”; and I will offer the highest premium in my power to Judge Douglas if he will show that he, in all his life, ever uttered a sentiment at all akin to that of Jefferson.

“Hit him again!” the crowd continued to holler at each of the next debates, as if watching a political prize fight, boxers in the ring, taunting, jabbing, dodging. Newspapers printed full transcriptions, including all the interjections from the crowd, the bloodthirsty calls, the thunderous applause. Lincoln began keeping a scrapbook of pasted newspaper columns. An inveterate archivist, he also knew that one day he’d make use of that record.

Their final debate took place in Alton, Illinois, on October 15, just weeks before the election. Not for the first time and not for the last, Lincoln bemoaned the suppression of plain talk about slavery, the endless avoidance of the question at hand. “You must not say anything about it in the free states because it is not here. You must not say anything about it in the slave states because it is there. You must not say anything about it in the pulpit, because that is religion and has nothing to do with it. You must not say anything about it in politics because that will disturb the security of ‘my place.’ There is no place to talk about it as being a wrong, although you say yourself it is a wrong.” And, as to the wrongness of slavery, he called it tyranny, and the idea of its naturalness as much an error as a belief in the divine right of kings. The question wasn’t sectionalism or nationalism, the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. The question was right against wrong. “That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent,” Lincoln said.16

In November, Lincoln narrowly lost to Douglas. But he had become a leader of the Republican Party—and indisputably its most powerful speaker. “Though I now sink out of view, and shall be forgotten,” he wrote, “I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I am gone.”17 But Lincoln had yet to leave his lasting mark.

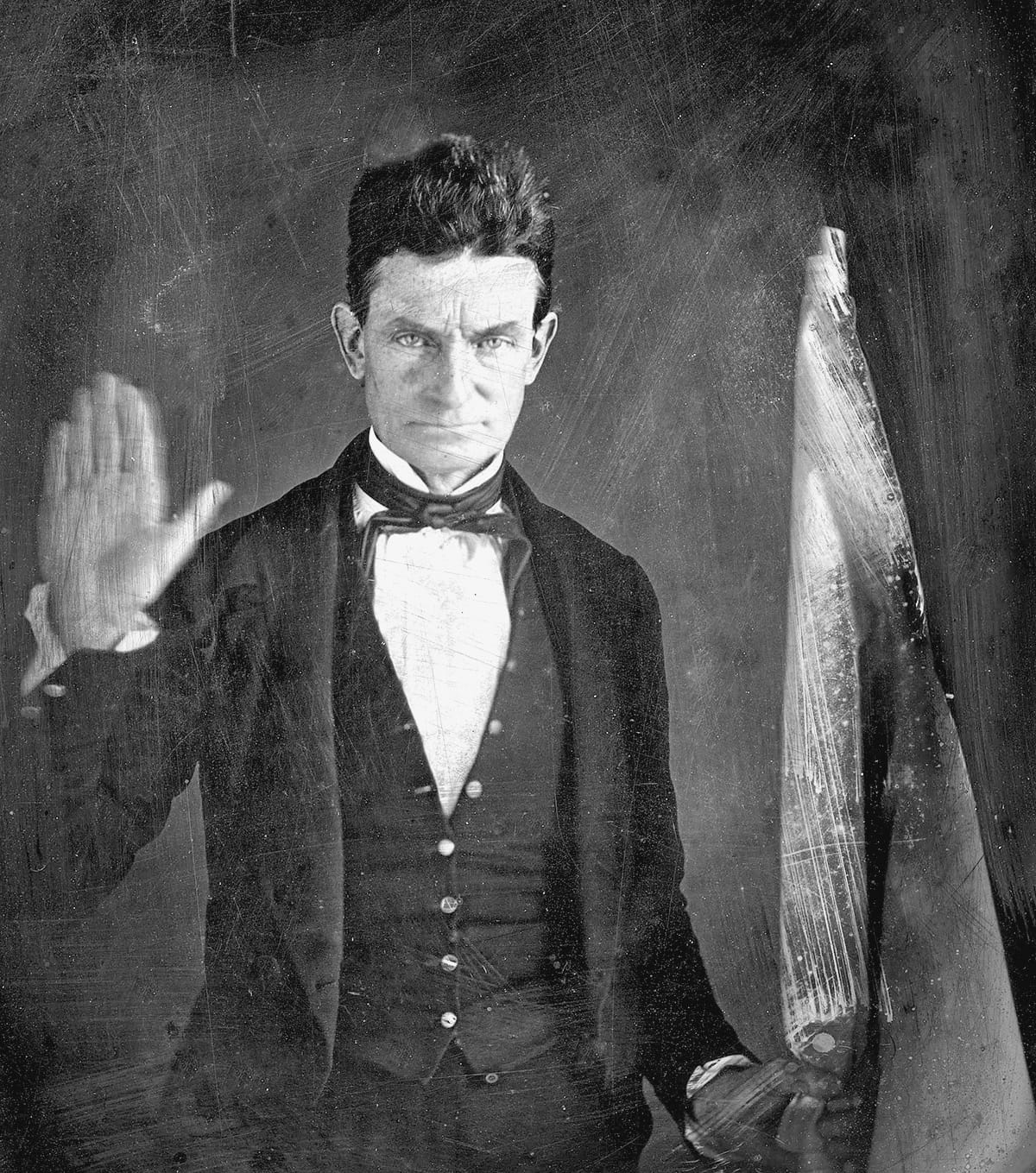

The year Lincoln debated Douglas, John Brown, with eyes like water and hair like a forest, held a constitutional convention in a hushed river town in Canada, fifty miles east of Detroit, a last stop on the Underground Railroad. Brown, fifty-eight, had fathered twenty children. He spoke of prophecies and scourges. He’d once founded a secret society called the League of Gileadites. A tanner, sheep farmer, and failed businessman, he’d first had his portrait taken by a black daguerreotype artist named Augustus Washington. In Washington’s portrait, Brown, lean and fearsome, with furrowed brow, stands beside the flag of the Underground Railroad and holds up a hand, as if he might break the very glass beneath which his image is trapped. In the 1850s, Brown became a militant abolitionist, fighting in Kansas with his sons. He sounded like a patriarch out of the Old Testament, Abraham sacrificing Isaac. In his 1858 constitution, Brown and his followers—forty-four black men and eleven white men—replaced “we the people” with “we, citizens of the United States and the oppressed people . . . who have no rights,” proclaimed bondage to be “in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence,” and declared war on slavery.18 They began stockpiling weapons.

In the 1850s, while antislavery conviction grew in the free states, pro-slavery fervor grew in the slave states, not least because the price of slaves was on the rise, from an average of $900 in 1850 to $1,600 ten years later. The high price meant that owners, who spared no pains in the hunting of men, women, and children, were less worried about slave rebellion than about a mass exodus from slave states to free, a much-feared and, in the South, widely reported “slave stampede” that was nothing so much as legions of people emancipating themselves.19

Some slave states, blaming the exodus on the influence of free blacks, tried to ban them. Arkansas required that all free blacks leave the state by the end of 1859 or be reenslaved. Meanwhile, some new states entering the Union adopted a “whites-only” policy: Oregon’s proposed constitution, which also placed severe restrictions on the growing number of immigrants from China—“No Negro, Chinaman, or Mulatto shall have the right of suffrage”—both prohibited slavery and barred blacks from entering the state.20

The price of slaves grew so high that a sizable number of white southerners urged the reopening of the African slave trade. In the 1850s, legislatures in several states, including South Carolina, proposed reopening the trade. Adopting this measure would have violated federal law. Some “reopeners” believed that the federal ban on the trade was unconstitutional; others were keen to nullify it, in a dress rehearsal for secession.

While John Brown and his men were drafting a new constitution in Canada, the Louisiana House of Representatives passed an act to reopen the trade. In 1859, anticipating the success of this movement, men from Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana formed the African Labor Supply Association. A Southern Commercial Convention meeting in Montgomery, Alabama, voted that “all laws, State and Federal, prohibiting the African slave trade, ought to be repealed.” Not content to wait for any of these laws to pass, southern vigilantes known as “filibusters” outfitted ships with arms and ammunition and attempted to conquer Cuba, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, and Brazil in order to extend a market for slaves. A leading reopener, Leonidas Spratt of South Carolina, said, “If the trade is wrong so be the condition which results from it”; the two could not be separated. Alabama’s William Yancey, born on the banks of the Ogeechee River in Georgia, said that the real issue was labor, and that the only difference between labor in the North and the South was that “one comes under the head of importation, the other under the head of immigration.” He said, “If it is right to buy slaves in Virginia and carry them to New Orleans, why is it not right to buy them in Cuba, Brazil, or Africa and carry them there?”21

Proslavery southerners made these arguments under the banner of “free trade,” their rhetorical answer to “free labor.” To George Fitzhugh, all societies were “at all times and places, regulated by laws as universal and as similar as those which control the affairs of bees,” and trade itself, including the slave trade, was “as old, as natural, and irresistible as the tides of the ocean.”22 In 1855, David Christy, the author of Cotton Is King, wrote about the vital importance of “the doctrine of Free Trade,” which included abolishing the tariffs that made imported English goods more expensive than manufactured goods produced in the North. As one southerner put it, “Free trade, unshackled industry, is the motto of the South.”23

If proslavery southerners defended free trade and pro-labor northerners defended free soil and free labor, abolitionists defended free speech. If southern Democrats came to Congress armed and ready to fight, and northern Whigs, Democrats, and Free-Soilers had usually come unarmed, northern Republicans nevertheless went to Congress ready to do battle. One Massachusetts congressman, heading to Washington for the 1855 session of Congress, was met at the train station by his constituents, bearing a gift. It was a pistol, engraved “Free Speech.”24

When the South began referring to its economy as “unshackled,” matters had plainly arrived at an ideological impasse. By the end of 1858, many observers had come around to Lincoln’s point of view that the United States would either be one thing or another, but not both. William H. Seward, a Florida-born senator from New York, called the dispute between the states an unavoidable conflict, moral, and absolute: “It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slaveholding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation.” Seward had no doubt which side would prevail, since his theory of history was a theory of progress, in a march from slavery to freedom and from inequality to equality. “I know, and you know, that a revolution has begun,” he told his audience. “I know, and the world knows, that revolutions never go backwards.”25

John Brown believed that the conflict was irrepressible, too, but he didn’t fear the nation slipping into it; he wanted to start it. In the spring of 1859, Brown and a party of his followers made their way to Maryland, where they planned a military operation that would begin with the seizing of a U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now part of West Virginia). In August, Frederick Douglass went to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, to meet with Brown, who had also tried, and failed, to enlist the support of Harriet Tubman. Brown and Douglass met at an abandoned stone quarry outside of town. Brown told Douglass about his plan. Douglass warned him against it, saying “it would . . . array the whole country against us.” The more Douglass heard, the more he worried. He later wrote, “All his arguments, and all his descriptions of the place, convinced me that he was going into a perfect steel trap, and that once in he would never get out alive.”26

On the night of Sunday, October 16, 1859, Brown and twenty-one men attacked the arsenal and captured it. They halted a train leaving Harpers Ferry but then let it go. As the train sped through the Maryland countryside to Baltimore, passengers threw hastily written notes out the windows, warning people about the insurrection. Barely twelve hours after the raid had begun, headlines were being telegraphed across the continent: “INSURRECTION . . . at Harper’s Ferry . . . GENERAL STAMPEDE OF SLAVES.”

Brown had fallen into the perfect steel trap that Douglass feared. He’d hoped that word of the attack would stir up a widespread revolt, that black men and women would take up arms. But while word spread across the country by telegraph, it did not reach the slave cabins on plantations in neighboring Maryland and Virginia; slaves, marooned and isolated from the technology of the telegraph, remained unaware of the insurrection. U.S. Marines and soldiers commanded by Robert E. Lee retook the arsenal, capturing Brown and killing or capturing all of his men. “The result proves the plan was the attempt of a fanatic or madman,” Lee said. Among the men killed was Dangerfield Newby, a free black man who was hoping to rescue his wife, Harriet, and their children from slavery in Virginia. His pocket held a letter from Harriet: “if I thought I shoul never see you,” she wrote him, “this earth would have no charms for me.”27

Brown had planned to lead an armed revolution throughout the South. At the nearby farm and school where he and his men had assembled, soldiers found sixteen boxes of weapons and ammunition, along with boxes of papers, including thousands of copies of his 1858 constitution and maps of the South, printed on cambric cloth, and with places where blacks outnumbered whites marked with Xs. They also found, rolled up into a scroll, a “Declaration of Liberty by the Representatives of the Slave Population of the United States of America.”

“We hold these truths to be Self Evident; That All Men are Created Equal,” it began, proceeding to establish a right to revolution: “The history of Slavery in the Unites States, is a history of injustice & Cruelties inflicted upon the Slave in evry conceivable way, & in barbarity not surpassed by the most Savage Tribes. It is the embodiment of all that is Evil, and ruinous to a Nation; and subversive of all Good.”28

News of Brown’s attack convinced southern slave owners that their worst fears were right: abolitionists were murderers. The so-called Secret Six, northern men who’d funded Brown, either denied their involvement or fled. Douglass, who’d not supported Brown’s plan but had known of it, escaped to Canada and then to England. “I am most miserably deficient in courage,” he confessed. But what most outraged slave owners was the number and stature of northerners who, on learning of Brown’s raid, celebrated him as a hero and a martyr. On October 30, in Concord, Henry David Thoreau, shoulders slumped, hat to his chest, delivered “A Plea for Captain John Brown.” “Is it not possible that an individual may be right and a government wrong?” Thoreau asked. Brown, he said, was, for his commitment to equality, “the most American of us all.”29

Thoreau’s own commitment to abolition was strengthened by his reading a book just published in London. The same was true of many of his contemporaries. The book had made its way to Concord even as Brown was raiding Harpers Ferry: Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Thoreau, a naturalist, a man of beans and bumblebees and frogs and herons, had been following Darwin’s work, and when the book appeared, he read it with a passionate interest, filling the pages of six notebooks with his notes. Darwin’s Origin of Species would have a vast and lingering influence on the world of ideas. Most immediately, it refuted the racial arguments of ethnologists like Louis Agassiz. And, in the months immediately following the book’s publication—the last, unsettling months before the beginning of the Civil War—abolitionists took it as evidence of the common humanity of man.30

During his trial, fifty-nine-year-old Brown, who’d been wounded during the battle, lay on a cot, unable to stand. Found guilty of murder, conspiracy, and treason, he was allowed to speak at his sentencing, on November 2. This speech earned Brown still more support in the North. “If it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country, whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments,” he said, “I submit.”31

Brown went to the gallows three weeks before Christmas, in the last month of the most tumultuous decade in American history. To northern abolitionists, his death marked the beginning of a second American Revolution. “The second of December, 1859,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote in his diary. “This will be a great day in our history; the date of a new Revolution,—quite as much needed as the old one.”32 Longfellow, building upon the verses he’d written in Poems on Slavery, decided to write a poem to stir the North to the cause of emancipation, to tie one revolution to another. He called it “Paul Revere’s Ride.”33

In Virginia, fifteen hundred soldiers gathered to watch Brown’s execution. Among them was John Wilkes Booth, serving with a troop from Richmond. Brown gave no speech on the gallows, but on the morning of his execution he handed a guard a note he’d scribbled on a scrap of paper: “I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land: will never be purged away; but with Blood.”34

Six days later, on December 8, 1859, the day of John Brown’s funeral, Mississippi congressman Reuben Davis gave a speech in Congress: “John Brown, and a thousand John Browns, can invade us, and the Government will not protect us.” The Union had betrayed the South, Davis argued. And so, he resolved, “To secure our rights and protect our honor we will dissever the ties that bind us together, even if it rushes us into a sea of blood.”35

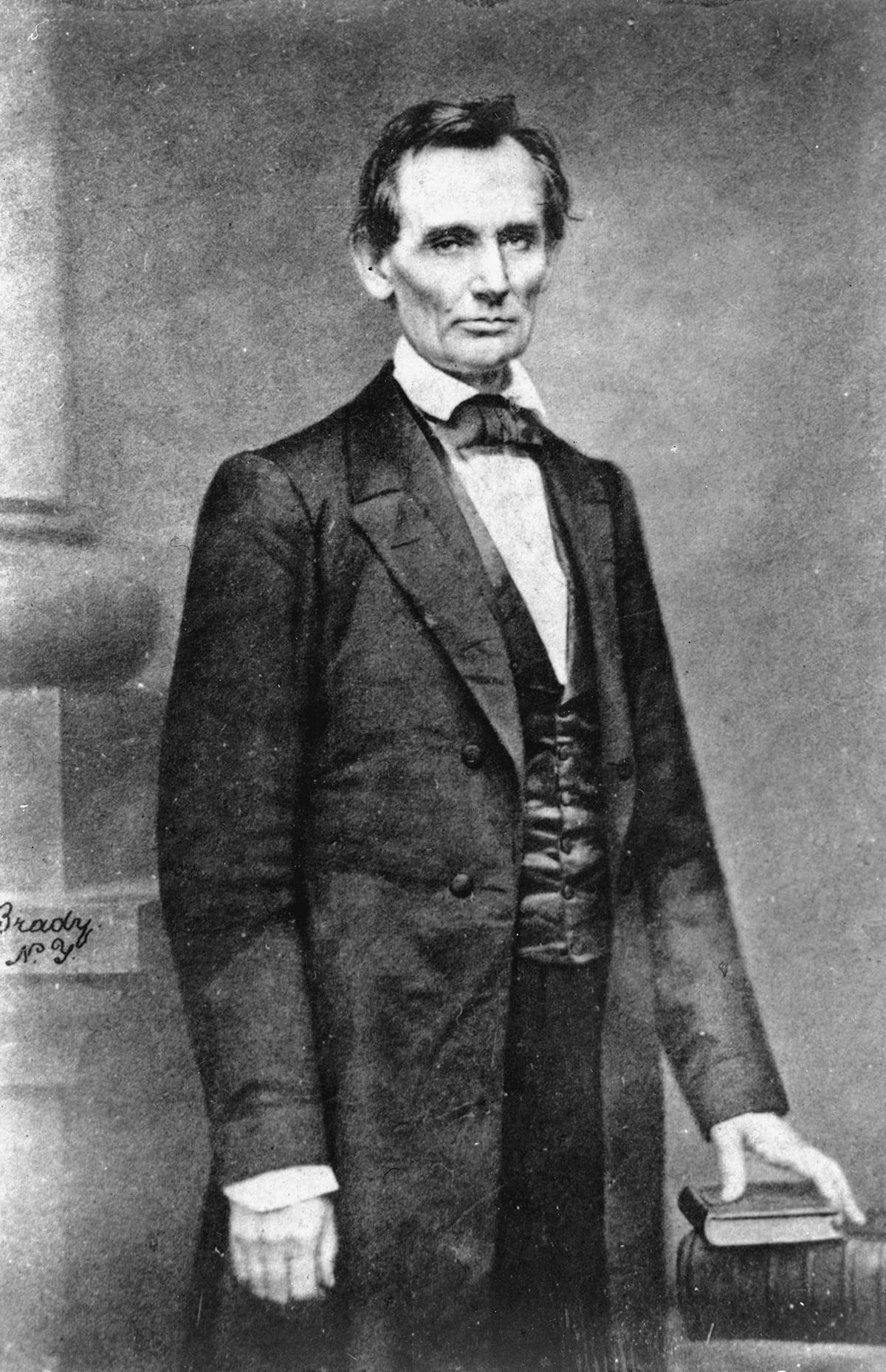

WEEKS AFTER DAVIS’S dire warning, lanky Abraham Lincoln visited Mathew Brady’s studio in New York. He posed for a photograph standing by a small table over which he towered, his left hand resting on a stack of books that looked, compared to him, as if they belonged in a dollhouse. His face was gaunt, his eyes hollow. Later that day, Lincoln delivered a speech at Cooper Union that launched his campaign for the Republican nomination for the presidency. The portrait, made into a miniature tintype, became a presidential campaign button.

Like everyone else running for president that year, Lincoln believed that the election turned on the interpretation of the Constitution. He set about making the case, once again, against Stephen Douglas, who was seeking the Democratic nomination. And, in a reprise of what he’d said during the great debates of 1858, he insisted both that Douglas’s interpretation of the Constitution was in error and that his argument amounted to anarchy: “Your purpose, then, plainly stated,” Lincoln charged, “is that you will destroy the Government, unless you be allowed to construe and enforce the Constitution as you please.”36

Lincoln had labored over the scrapbook he’d assembled of newspaper transcriptions of his 1858 debates with Douglas. The time had come to put them to use. He faithfully edited them for publication, not changing the speeches, omitting only the “cheers” and “laughter” and other reactions from the crowds. Political Debates Between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas was first advertised on May 5, 1860, eleven days before the Republican National Convention, with promotional copy that boasted, fairly enough: “There is probably no better exposition of the doctrines of the Democratic and Republican Parties than is contained in this volume.” When people invited Lincoln to speak, he very often told them to read the Debates instead. Douglas, incensed, complained that his speeches had been “mutilated,” a charge without foundation, but one that suggests that Douglas knew, as Lincoln knew, that even if Douglas had won that election, Lincoln had won those debates.37

The Democratic Party held its national convention in Charleston, South Carolina, in April, just before the published Debates appeared. The platform committee had been unable to bind together the two arms of the party, producing both a Majority Report, endorsed by southern delegates, and a Minority Report, submitted by northerners, whereupon the Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Florida delegations walked out of the convention in protest of the platform’s failure to include a guarantee of the rights of citizens to hold “all descriptions of property” (meaning slaves). Unable to nominate a candidate, the remaining delegates decided to hold a second convention—to gather in Baltimore in June.

The Republicans met in Chicago in May, in a massive building called the Wigwam, after its arched wooden ceiling. The party endorsed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—leading one delegate to observe that, while he also believed in the Bible and the Ten Commandments, he didn’t see why these documents needed mentioning—but specifically disavowed any proslavery interpretation of the Constitution as “a dangerous political heresy.”38 For the nomination, Lincoln was something of a dark horse. But Lincoln’s supporters successfully courted delegates and resorted, too, to political chicanery. The day the balloting began, Lincoln’s campaign managers printed thousands of fake admission tickets and handed them out to Lincoln supporters, who then packed the hall and thundered their applause whenever Lincoln’s name was mentioned. Lincoln won the nomination, to still more thunder.39

William Dean Howells, twenty-three and prodigiously talented, agreed to write a campaign biography for Lincoln.40 Howells, at the time, was an unknown poet from Ohio; he would go on to become one of the century’s most esteemed men of letters. He wrote his Life of Abraham Lincoln in a matter of weeks, as much as a satire of the form as an example of it. Howells had never met Lincoln and knew very little about him; what he did know was that campaign biographies were overwrought, ridiculous, and fabulous.41 He had not the least idea who Lincoln’s ancestors were; he somehow worked that out to be a credit to the candidate. “There is a dim possibility that he is of the stock of the New England Lincolns, of Plymouth colony,” he wrote, “but the noble science of heraldry is almost obsolete in this country, and none of Mr. Lincoln’s family seems to have been aware of the preciousness of long pedigrees.” Later, in the White House, Lincoln checked Howells’s book out of the Library of Congress, in order to check Howells’s facts. He made corrections in the margins. Howells had claimed that in the 1820s Lincoln had been “a stanch Adams man”—a supporter of John Quincy Adams. Lincoln crossed out “Adams” and wrote “anti-Jackson.” Among Howells’s many tall tales, he’d told about how, as a young congressman, Lincoln had walked for miles to the Illinois legislature, Lincoln scribbled in the margin: “No harm, if true; but, in fact, not true. L.”42

While Republicans campaigned for Honest Abe, Democrats gathered in Baltimore for their second convention in June. An American flag was hung in the front of the hall, embroidered with the hopeful motto: “We Will Support the Nominee.” The convention opened with the proposal of a loyalty oath: “every person occupying a seat in this convention is bound in good honor and good faith to abide by the action of this convention, and support its nominee.”43 The deliberations fell apart. At one point, one delegate drew his pistol on another. For the nomination, the convention was deadlocked through fifty-seven roll calls. On June 22, 1860, the Democratic Party split: the South walked out. The next day, Caleb Cushing of Massachusetts, presiding, stepped down, declaring, “The delegations of a majority of the States of this Union have, either in whole or in part, in one form or another, ceased to participate in the deliberations of this body.” But the convention ultimately nominated Douglas, as the candidate of the Northern Democratic Party, while the bolting southern delegates reconvened down the street, opened their own convention, and nominated John C. Breckinridge, U.S. senator from Kentucky, on their first ballot, the candidate for the Southern Democratic Party.44

In November, when Longfellow heard that Lincoln had won the election, he exulted. “It is the redemption of the country,” he wrote in his diary. “Freedom is triumphant.”45 Lincoln won every northern state, all six states in which the Lincoln-Douglas debates had been published, and all four states in which black men could vote. But Lincoln had won hardly any votes in the South, and his election led to unrest in the North, too, including attacks on abolitionists. In December, when Frederick Douglass was slated to speak in Boston’s Tremont Temple on the occasion of the anniversary of John Brown’s execution, a mob broke into the hall to silence him. To answer them, Douglass days later delivered a blistering “Plea for Free Speech,” in which, as had Longfellow, he placed abolition in the tradition of the nation’s founding. “No right was deemed by the fathers of the Government more sacred than the right of speech,” Douglass said, and “Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist.”46

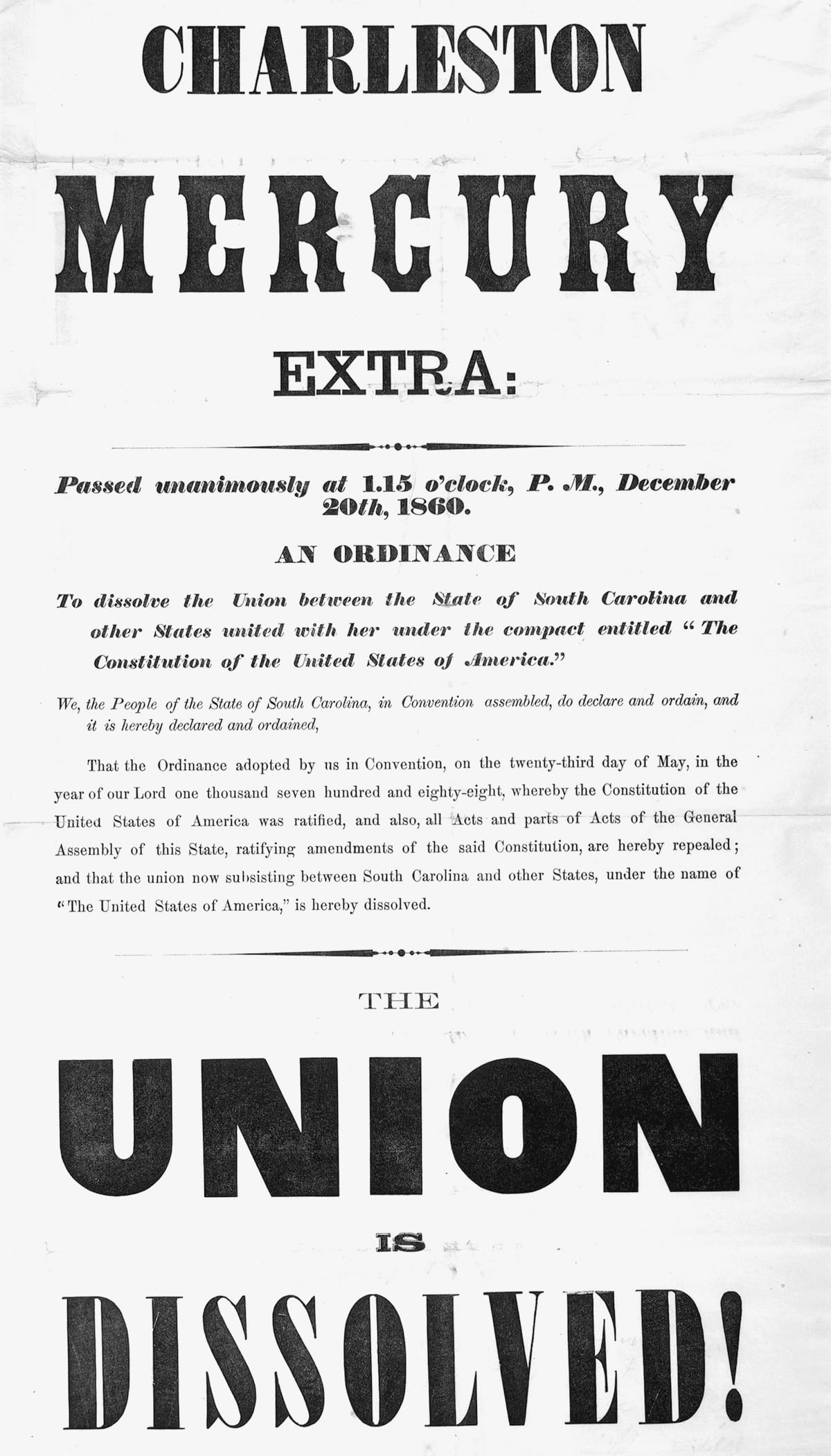

Many in the South pressed for secession. Others urged patience. Two days after the election, the New Orleans Bee printed a one-word response to Lincoln’s victory: “WAIT.”47 They did not wait for long. Six weeks after the election, South Carolinians held a convention in which they voted to repeal the state’s ratification of the Constitution, declaring, “The union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of ‘The United States of America,’ is hereby dissolved.”48 Six states followed—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—and in February 1861 they formed the Confederate States of America, with, as president, former Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis, a man the Texan Sam Houston once called “as ambitious as Lucifer and as cold as a lizard.”49

“The dissolution of the Union goes slowly on,” Longfellow wrote in his diary, miserably. “Behind it all I hear the low murmur of the slaves, like the chorus in a Greek tragedy.”50

II.

AT HIS INAUGURATION, Jefferson Davis, tall and gaunt, insisted that only the Confederacy was true to the original Constitution. “We have changed the constituent parts, but not the system of government. The constitution formed by our fathers is that of these Confederate States.”51 But when delegates from the seven seceding states met in secret in Montgomery, Alabama, they adopted a constitution that had more in common with the Articles of Confederation (“We, the people of the Confederate States, each State acting in its sovereign and independent character . . .”).

The truths of the Confederacy disavowed the truths of the Union. The Confederacy’s newly elected vice president, a frail Georgian named Alexander Stephens, delivered a speech in Savannah in which he made those differences starkly clear. The ideas that lie behind the Constitution “rested upon the assumption of the equality of races,” Stephens said, but “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea: its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery . . . is his natural and moral condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”52 It would become politically expedient, after the war, for ex-Confederates to insist that the Confederacy was founded on states’ rights. But the Confederacy was founded on white supremacy.

The South having seceded, Lincoln was nevertheless inaugurated, as scheduled, on March 4, 1861. He’d grown a beard since Election Day, a development that, in a quieter year, might have caused more of a stir. He rode from his hotel to the ceremony with James Buchanan in an open carriage, driven by a black coachman, surrounded by battalions of cavalry and infantry: there was every reason to fear someone might try to kill him. Riflemen positioned themselves in the windows of the Capitol, prepared to shoot anyone in the crowd who drew a gun.

Sworn into office by the Chief Justice Roger Taney, who’d presided over Dred Scott, Lincoln went on to give the most eloquent inaugural address in American history. “One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended,” he said. “This is the only substantial dispute.” He hoped that this dispute could yet be resolved by debate. He closed:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.53

The better angels did not prevail. Debate had failed.

“Slavery cannot tolerate free speech,” Frederick Douglass had said, in his “Plea for Free Speech.”54 The seventeenth-century battle for freedom of expression had been fought by writers like John Milton, opposing the suppression of religious dissent; the eighteenth-century struggle for the freedom of the press had been fought by printers like Benjamin Franklin and John Peter Zenger, opposing the suppression of criticism of the government; and the nineteenth century’s fight for free speech had been waged by abolitionists opposing southern slave owners, who had been unwilling to subject slavery to debate.

Opposition to free speech had long been the position of slave owners, a position taken at the constitutional convention and extended through the gag rule, antiliteracy laws, bans on the mails, and the suppression of speakers. An aversion to political debate also structured the Confederacy, which had both a distinctive character and a lasting influence on Americans’ ideas about federal authority as against popular sovereignty. Secessionists were attempting to build a modern, proslavery, antidemocratic state. In order to wage a war, the leaders of this fundamentally antidemocratic state needed popular support. Such support was difficult to gain and impossible to maintain. The Confederacy therefore suppressed dissent.55

“The people have with unexampled unanimity resolved to secede,” one South Carolina convention delegate wrote in his diary, but this was wishful thinking.56 Seven states of the lower South seceded before Lincoln’s inauguration, but the eight states of the upper South refused to do the same. And even in the lower South, the choice to secede was not a simple one. Nor was it an easy victory.

The most ardent supporters of secession were the wealthiest plantation owners; the least ardent were the great majority of white male voters: poor men who did not own slaves. The most effective way to persuade these men to support secession was to argue that even though they didn’t own slaves, their lives were made better by the existence of the institution, since it meant that they were spared the most demeaning work. Prosecessionists made this argument repeatedly, and with growing intensity. James D. B. DeBow’s The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder (1860) was widely excerpted in newspapers, reminding poor white men that “No white man at the South serves another as a body servant, to clean his boots, wait on his table, and perform the menial services of his household.”57

Nevertheless, rather than trusting a decision about secession to the voters, or even to a ratifying convention, Georgia legislator Thomas R. R. Cobb advised his legislature to make the decision itself: “Wait not till the grog shops and cross roads shall send up a discordant voice from a divided people.” When Georgia did hold a convention, its delegates were deeply split. The secessionists cooked the numbers in order to insure their victory and proceeded to require all delegates to sign a pledge supporting secession even if they had voted against it. One of the first things the new state of Georgia did was to pass a law that made dissent punishable by death.58

As hard as secessionists fought for popular support, and as aggressively as they suppressed dissent, they were nevertheless only partially successful. Four states in the upper South only seceded after Confederate forces fired on U.S. troops at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12. Even then, Virginia kept on stalling until, on April 17, Governor Henry Wise walked into the Virginia convention and took out his pistol and said that, by his order, Virginia was now at war with the federal government, and that if anyone wanted to shoot him for treason, they’d have to wrestle his pistol away from him first. The convention voted 88–55 to recommend secession. That went to the state’s electorate on May 23, which voted 125,950–20,373 in favor. Most who opposed it were in the western part of the state. In June, they held their own convention and effectively seceded from the state, to become West Virginia. Four more states in the upper South still refused to secede, even as the cords that tied the nation together were being cut. Telegraph wires were only just first stretching all the way across the American continent. The first message sent, from east to west, had read: “May the Union Be Perpetuated.” After the firing on Fort Sumter, Lincoln ordered the telegraph wires connecting Washington to the South severed.59

By May of 1861, the Confederacy comprised fifteen states stretching over 900,000 square miles and containing 12 million people, including 4 million slaves, and 4 million white women who were disenfranchised. It rested on the foundational belief that a minority governs a majority. “The condition of slavery is with us nothing but a form of civil government for a class of people not fit to govern themselves,” said Jefferson Davis.60

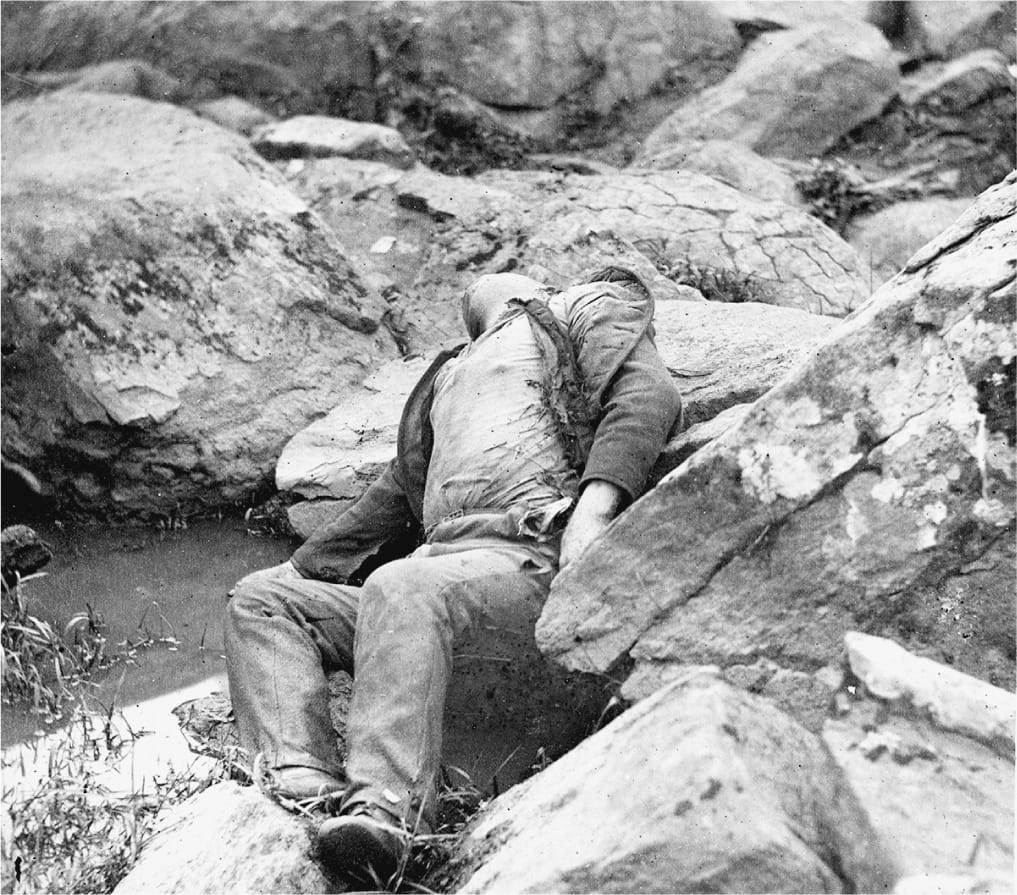

The Civil War inaugurated a new kind of war, with giant armies wielding unstoppable machines, as if monsters with scales of steel had been let loose on the land to maul and maraud, and to eat even the innocent. When the war began, both sides expected it to be limited and brief. Instead, it was vast and long, four brutal, wretched years of misery on a scale never before seen. In campaigns of singular ferocity, 2.1 million Northerners battled 880,000 Southerners in more than two hundred battles. More than 750,000 Americans died. Twice as many died from disease as from wounds. They died in heaps; they were buried in pits. Fewer than 2,000 Americans had died in battle during the entire War with Mexico. In a single battle of the Civil War, at Shiloh, Tennessee, in 1862, there were 24,000 casualties. Soldiers were terrified of being left behind or lost among the unnamed, unburied, unremembered dead. One soldier from South Carolina wrote home: “I have a horror of being thrown out in a neglected place or bee trampled on.” On battlefields, the dead and dying were found clutching photographs of their wives and children. After yet another slaughter, Union general Ulysses S. Grant said a man could walk across the battlefield in any direction, as far as he could see, without touching the ground but only the dead.61

Fields where once waved stalks of corn and wheat yielded harvests of nothing but suffering and death or, falling fallow, nothing but graves. All of this, each misery, its grand scale, for the first time in history, was captured on camera, archived, displayed, exhibited. A thousand photographers produced hundreds of thousands of photographs on battlefield after battlefield. After the first major battle fought in the North, in Maryland—the worst day in American military history, with 26,000 Confederate and Union soldiers killed, wounded, captured, or missing—Mathew Brady, in his National Photographic Portrait Gallery, on the corner of New York’s Tenth Street and Broadway, opened The Dead of Antietam, an exhibit of photographs of the carnage taken by a Scottish immigrant named Alexander Gardner. “Mr. BRADY has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war,” the New York Times reported. “If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”62

On a scorched Wednesday, July 1, 1863, the turning point in the war came at the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. By the third day of fighting, each side had lost more than 20,000 men, and the Confederate general, the fifty-six-year-old Virginian Robert E. Lee, began his retreat. Five thousand horses, fallen, were burned to stop their rotting, the smoke of those fires mingling with the steam that rose from the fetid remains of unburied men. Samuel Wilkeson, a reporter for the New York Times, went to report on the battle and found that his oldest son, a lieutenant, had been wounded in the leg and had died after his surgeons abandoned him when Confederates neared the barn where they were attempting an amputation. On July 4, America’s eighty-seventh birthday, Wilkeson buried his son and filed his report. “O, you dead, who died at Gettysburg have baptized with your blood the second birth of freedom in America,” he wrote in agony, before supplying his readers with a list of the dead and wounded.63 The next day, Alexander Gardner and two of his team showed up with their cameras and took shots from which Gardner made some eighty-seven photographs, a field of ghosts. They lay in trenches, they lay on hilltops; they lay between trees, they lay atop rocks.

Gardner gathered them together in a book of the dead, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, America’s first book of photographs. Gardner had been an abolitionist, and the book included photographs of the dead and dying but it included, too, scenes of towns and streets and scenes that told the story of slavery. On a brick building of a trading house was printed: “Price, Birch & Co. Dealers in Slaves.” Gardner titled it Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia.64 Gardner was a Union soldier, his camera his weapon.

Four months after the carnage, Lincoln set out for Gettysburg. Thousands of bodies had lain, barely covered by dirt; hogs rutting in the fields had dug up arms and legs and heads. But with caskets provided by the War Department, the corpses had been uncovered, sorted, and catalogued; a third had been reburied, the rest waited. Lincoln had been invited to dedicate their burial. After an eighty-mile train ride, he arrived in Pennsylvania at dusk to find coffins still stacked at the station. The next morning, still in mourning for his own young son, he rode at the head of a march of one hundred men astride horses. The oration that day was given by Edward Everett. Lincoln, offering a dedication, spoke for a mere three minutes. With a scant 272 words, delivered slowly in his broad Kentucky accent, he renewed the American experiment.65

He spoke first of the dead: “We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.” But a cemetery is not only for the dead, he said:

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.66

He did not mention slavery. There would be those, after the war ended, who said that it had been fought over states’ rights or to preserve the Union or for a thousand other reasons and causes. Soldiers, North and South, knew better. “The fact that slavery is the sole undeniable cause of this infamous rebellion, that it is a war of, by, and for Slavery, is as plain as the noon-day sun,” a soldier writing for his Wisconsin regimental newspaper explained in 1862. “Any man who pretends to believe that this is not a war for the emancipation of the blacks,” a soldier writing for his Confederate brigade’s newspaper wrote that same year, “is either a fool or a liar.”67 By then, the emancipation had begun.

III.

IT WAS AN American Odyssey. “They came at night, when the flickering camp-fires shone like vast unsteady stars along the black horizon,” W. E. B. Du Bois later wrote, “old men, and thin, with gray and tufted hair; women with frightened eyes, dragging whimpering hungry children; men and girls, stalwart and gaunt.”68 They came, too, in daylight, and on horseback, by wagon and cart. They clambered aboard trains. They packed food and stole guns. They walked and they ran and they rode, carrying their children on their backs, dedicating themselves to the unfinished work of the nation: freeing themselves.

The Civil War was a revolutionary war of emancipation. The exodus began even before the first shots were fired, but the closer the Union army drew, the more the people fled. The families who lived on Jefferson Davis’s thousand-acre cotton plantation, Brierfield, with its colonnaded mansion, in Mississippi, just south of Vicksburg, began leaving early in 1862. Another 137 people left Brierfield after the fall of Vicksburg and headed to Chickasaw Bayou, a Union camp. Confederate secretary of state Robert Toombs had boasted that the Confederacy would win the war and that he would one day call a roll of slaves at Bunker Hill. Wrote one newspaper reporter, after the arrival of Davis’s former slaves at Chickasaw Bayou, “The President of the Confederate States may call the roll of his slaves at Richmond, at Natchez, or at Niagara, but the answer will not come.”69

Lincoln announced on September 22, 1862, in a Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, that he would free nearly every slave held in every Confederate state in exactly one hundred days—on New Year’s Day 1863. He’d planned the announcement for a long time, wrestling with his conscience. “I said nothing to anyone,” he later told his cabinet, “but I made the promise to myself and to my maker.”70 Across the land, people fell to their knees. Frederick Douglass said that the war had at last been “invested with sanctity.” In New York, Horace Greeley declared that “in all ages there has been no act of one man and of one people so sublime as this emancipation.” The New York Times deemed the Proclamation as important as the Constitution. “Breath alone kills no rebels,” Lincoln cautioned. But a crowd of black men, women, and children nevertheless came to the White House and serenaded him, singing hosannas.71

The announcement set the South on fire. The Richmond Examiner called the promised Emancipation Proclamation the “most startling political crime, the most stupid political blunder, yet known in American history.” Fifteen thousand copies of the Proclamation having been printed, the news made its way within days to slaves, whispered through windows, shouted across fields. Isaac Lane swiped a newspaper from his master’s mail and read it aloud to every slave he could find. Not everyone was willing to wait as long as one hundred days. In October, men caught planning a rebellion in Culpeper, Virginia, were found to have in their possession newspapers in which the Proclamation had been printed; seventeen of those men were killed, their executions meant as a warning, the reign of a different hell.72

Frederick Douglass, who had led his people to the very gates of freedom, worried that Lincoln might abandon the pledge. “The first of January is to be the most memorable day in American Annals,” he wrote. “But will that deed be done? Oh! That is the question.” The promised emancipation turned the war into a crusade. But not all of Lincoln’s supporters were interested in fighting a crusade against slavery. As autumn faded to winter, pressure mounted on the president to retract the promise. He held fast.

“Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history,” Lincoln told Congress in December. “We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.” On Christmas Eve, day ninety-two, a worried Charles Sumner visited the White House. Would the president make good his pledge? Lincoln offered reassurance. On December 29, Lincoln read a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. (It did not free slaves in states that had not seceded, nor those in territory in secessionist states held by the Union army.) Cabinet members suggested an amendment urging “those emancipated, to forbear from tumult.” This Lincoln refused to add. But Salmon Chase, secretary of the Treasury, suggested a new ending, which Lincoln did adopt: “I invoke the considerate judgment of all mankind and the gracious favor of almighty God.”73

On day ninety-six, Douglass declared, “The cause of human freedom and the cause of our common country are now one and inseparable.” Ninety-seven, ninety-eight. Ninety-nine: New Year’s Eve 1862, “watch night,” the eve of what would come to be called the “Day of Days.”

In the capital, crowds of African Americans filled the streets. In Norfolk, Virginia, four thousand slaves—who, living in a border state that was not part of the Confederacy, were not actually freed by the Emancipation Proclamation—paraded through the streets with fifes and drums, imitating the Sons of Liberty. In New York, Henry Highland Garnet, the black abolitionist, preached to an overflow crowd at the Shiloh Presbyterian Church. At exactly 11:55 p.m., the church fell silent. The parishioners sat in the cold, in the stillness, counting those final minutes, each tick of the clock. At midnight, the choir broke the silence: “Blow Ye Trumpets Blow, the Year of Jubilee has come.” On the streets of the city, the people sang another song:

Cry out and shout all ye children of sorrow,

The gloom of your midnight hath passed away.

One hundred. On January 1, 1863, sometime after two o’clock in the afternoon, Lincoln held the Emancipation Proclamation in his hand and picked up his pen. He said solemnly, “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.”74

In South Carolina, the Proclamation was read out to the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, a regiment of former slaves. At its final lines, the soldiers began to sing, quietly at first, and then louder:

My country, ’tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty,

Of thee I sing!75

American slavery had lasted for centuries. It had stolen the lives of millions and crushed the souls of millions more. It had cut down children, stricken mothers, and broken men. It had poisoned a people and a nation. It had turned hearts to stone. It had made eyes blind. It had left gaping wounds and terrible scars. It was not over yet. But at last, at last, an end lay within sight.

The American Odyssey had barely begun. From cabins and fields they left. Freed men and women didn’t always head north. They often went south or west, traveling hundreds of miles by foot, on horseback, by stage, and by train, searching. They were husbands in search of wives, wives in search of husbands, mothers and fathers looking for their children, children for their parents, chasing word and rumors about where their loved ones had been sold, sale after sale, across the country. Some of their wanderings lasted for years. They sought their own union, a union of their beloved.

“MEN OF COLOR, TO ARMS!” Frederick Douglass cried on March 2, 1863, calling on black men to join the Union army: “I urge you to fly to arms, and smite with death the power that would bury the Government and your liberty in the same hopeless grave.” Congress had lifted a ban on blacks in the military in 1862, but with emancipation, Douglass began traveling through the North as a recruiting agent for the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry, a newly formed all-black regiment. “The iron gate of our prison stands half open,” Douglass wrote. “The chance is now given you to end in a day the bondage of centuries.”76

The Confederacy, meanwhile, had called its own men to arms, instituting the first draft in American history. The Union had soon followed, instituting a draft of its own. In July 1863, white New Yorkers, furious at being called to fight what was plainly a war of emancipation, protested the draft during five days of violent riots that mainly involved attacking the city’s blacks. Eleven men were lynched, and the more than two hundred children at the Colored Orphan Asylum only barely escaped when the building was set on fire.

The Confederate draft called on as many as 85 percent of white men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five, a much broader swath of the population than served in the Union army. Seventy percent of Union soldiers were unmarried; the Confederate draft drew on married men, leaving their families at risk of destitution and starvation. “I have no head to my family,” one Confederate woman wrote in 1863, the year the Confederate government also passed a “one-tenth tax,” requiring citizens to give 10 percent of everything grown or raised on farms to the state.77 Near the end of the war, the Confederate government, its army desperately short of both men and supplies, decided to do what had been for so long unthinkable: it began enlisting slaves as soldiers, to the great dismay of many Confederate soldiers, who’d been urged to fight to protect their rights as whites. One private from North Carolina wrote home to his mother, “I did not volunteer my services to fight for A free Negroes free country, but to fight for A free white mans free country.”78

The Civil War expanded the powers of the federal government by precedents set in both the North and the South that included not only conscription but also a federal currency, income taxes, and welfare programs. The Union, faced with paying for the war against the Confederacy, borrowed from banks and, when money ran short, recklessly printed it, producing federal legal tender, the greenback. The House Ways and Means Committee considered levying a tax on land, willing to take the risk that such a measure would be eventually struck down as unconstitutional, because a land tax is a direct tax. But Schuyler Colfax, a Republican from Indiana, objected: “I cannot go home and tell my constituents that I voted for a bill that would allow a man, a millionaire, who has put his entire property into stock, to be exempt from taxation, while a farmer who lives by his side must pay a tax.” A tax on income seemed a reasonable, and less regressive, alternative. A number of states—Pennsylvania, Virginia, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, and Florida—already taxed income. And Britain had partly funded the Crimean War by doing the same. Unlike a tax on real estate, an income tax was not, or at least not obviously, a direct tax, prohibited by the Constitution. Income also included earnings from stocks and so didn’t exempt fat cats. In 1862, Lincoln signed a law establishing an Internal Revenue Bureau charged with administering an income tax, later turned into a graduated tax, taxing incomes over $600 at 3 percent and incomes more than $10,000 at 5 percent. The Confederacy, reluctant to levy taxes, was never able to raise enough money to pay for the war, which is one reason the rebellion failed.79

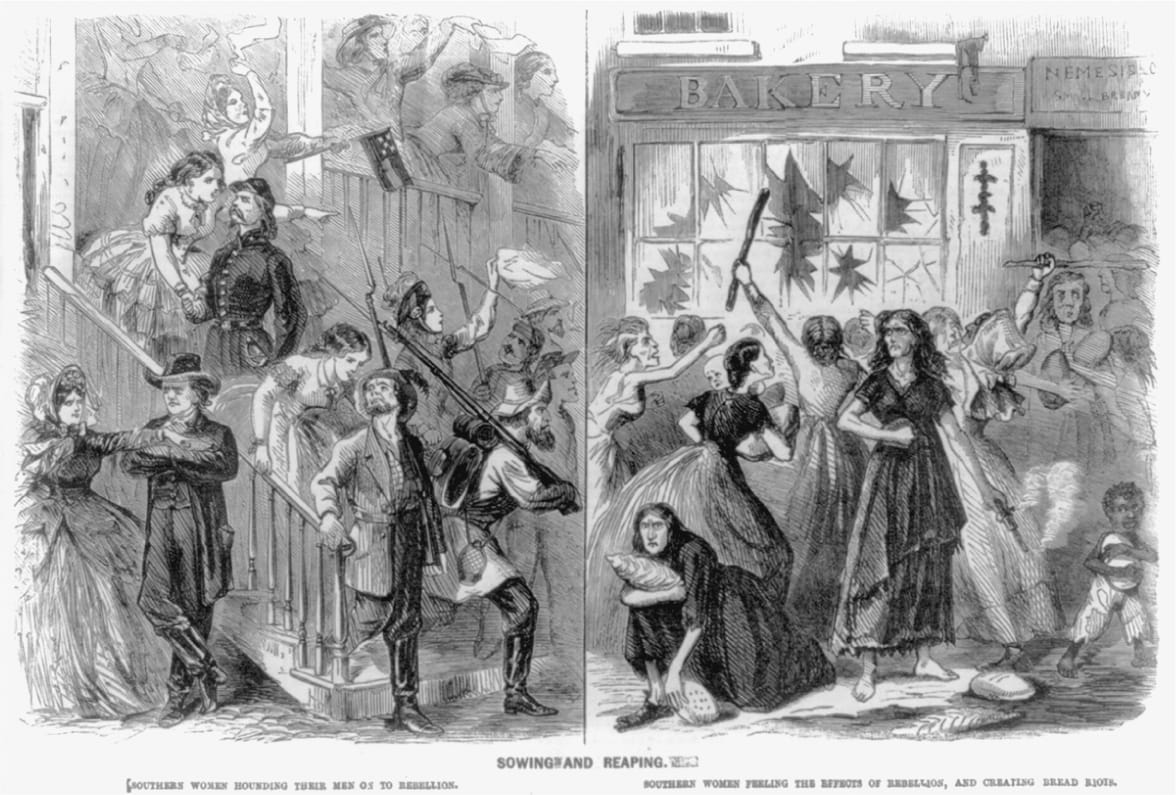

Yet ironically the Confederacy, a government opposed to federal power, exercised it to a far greater degree than the Union. The rhetoric of war had it that Southerners were fighting to protect their homes and especially their wives. But Confederate conscription led white women in the South to protest politically. They entered the political arena with much the same fervor that Northern women had for decades demonstrated in the fight for abolition. By 1862, large numbers of soldiers’ wives had begun petitioning the government, seeking relief. Mary Jones, a soldier’s widow from the river town of Natchez, Mississippi, wrote to her governor: “Every Body say I must be taken care of by the Confederate States they did not tell my Deare Husband that I should Beg from Door to Door when he went to fight for his country.” These disenfranchised women employed the rhetoric of wartime sacrifice as a claim to citizenship: “We have given our men.” They also began organizing collectively by staging food riots. In November 1862, two petitioning women warned that “the women talk of Making up Companys going to try to make peace for it is more than human hearts can bear.” Another woman warned the governor of North Carolina, “The time has come that we the common people has to hav bread or blood and we are bound boath men and women to hav it or die in the attempt.” The following spring, female mobs numbering in the hundreds, and often armed with knives and guns, were involved in at least twelve violent protests. “Bread or blood,” rioting women shouted, in Atlanta, in Richmond, in Mobile. In Salisbury, North Carolina, Mary Moore had a message for her governor: “Our Husbands and Sons are now separated from us by the cruel war not only to defend their humbly homes but the homes and property of the rich man.”80

In the end, the petitions written and protests staged by white Confederate women contributed to the creation of a new system of public welfare, relief for soldiers’ wives, a state welfare system bigger than any anywhere in the Union. The rise of the modern welfare system is often traced to the pension system instituted for Union veterans in the 1870s, but it was the Confederacy—and Southern white women—that laid its foundation.81

The war was not yet won and emancipation not yet achieved. As late as the summer of 1862, in the last weeks before the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln had insisted that the purpose of the war was to save the Union. “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it,” he wrote Horace Greeley, “and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”82 But by 1864, he had wholly changed his mind. Victory without abolition would be no victory at all.

The Emancipation Proclamation had freed all slaves within the Confederate states, but it had not freed slaves in the border states, and it had not made slavery itself impossible: that would require a constitutional amendment. While soldiers fought and fell on distant battlefields, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony knocked on doors and gathered four hundred thousand signatures demanding passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, prohibiting slavery in the United States.83 The measure was approved by the Senate, 33–6, on April 8, 1864. All Senate Republicans, three Northern Democrats, and five senators from border states voted in favor. But in the House, voting weeks before the Republican National Convention was scheduled to meet in Baltimore, the amendment fell thirteen votes short of the needed two-thirds majority.

A war-weary Abraham Lincoln had decided to run for reelection, even though no American president had served a second term since Andrew Jackson. His supporters handed out campaign buttons, tintype photographs of Lincoln, cased in metal. His face is sunken and craggy, as chiseled as a sea-swept rock. He lifts his chin and looks off into the distance as if offering a promise.84 In the election, he confronted a meager opponent, George McClellan, an inept general whom Lincoln had relieved of his command. McClellan’s support within the party was thin. At the Democratic Convention in August, a display outside the hall—coiled gas pipe with jets that were meant to ignite and spell out the words “McClellan, Our Only Hope”—failed and only sputtered, as helplessly as the candidate.85 Three months later, Lincoln won 55 percent of the popular vote, the greatest margin since Jackson’s reelection in 1828. His most sweeping victory came from the Union army: 70 percent of soldiers voted for him. Instead of voting for their former commander, McClellan, they cast their votes for Lincoln—and for emancipation.86

After the election, Lincoln pressed the House for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment by lobbying senators from border states. “We can never have an entire peace in this country so long as the institution of slavery remains,” said James S. Rollins of Missouri, a former slave owner. When the amendment finally passed by the required two-thirds majority, on January 31, 1865, 119 to 56, the hall for a moment fell silent. And then members of Congress sank to their seats and “wept like children.” Outside, a hundred-gun salute announced the result. From the battlefield, one black Union soldier wrote: “America has washed her hands at the clear spring of freedom.”87 Only time would tell whether the water from that spring could ever clean the stain of slavery.

Rain fell in Washington for weeks that winter as winds lashed the city, uprooting trees, as if the very weather were bringing the cruelty of war to the capital. On the morning of Lincoln’s inauguration, March 4, the crowds came armed with umbrellas, bayoneted against the sky. They huddled in a swamp of puddles and mud. A fog fell over the city. But just as Lincoln rose to speak, the skies cleared and the sun broke through the clouds. With the heavy steps of his lumbering gait, Lincoln ascended the platform on the east front of the Capitol. Alexander Gardner captured him in a photograph of magnificent acuity. Lincoln wears no hat. He holds a sheaf of papers in his hand and looks down. He spoke but briefly. Slavery had been “the cause of the war,” and yet “fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away”: a prayer for the living and for the dead. And then he closed, with words that have since been etched into his memorial:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

John Wilkes Booth, twenty-six, watched from the balcony. “What an excellent chance I had to kill the President, if I had wished, on Inauguration Day!” he’d later say.88

On April 9, in the parlor of a farmhouse in Appomattox, Virginia, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his command to Union General Ulysses Grant. Two days later, Booth, a well-known Shakespearean actor, stood uneasily in a crowd, watching Lincoln deliver a speech in which the president explained the terms of the victory. “That means nigger citizenship,” Booth muttered. Four days and some hours after that, at about 10:15 p.m. on April 14, Good Friday, Booth shot Lincoln with a derringer in Ford’s Theatre, a playhouse six blocks from the White House.

Lincoln slumped in a chair, a walnut rocker, unconscious. An army surgeon leapt into the president’s box, laid Lincoln out on the carpeted floor, removed his shirt, and looked for the wound. He and two other doctors then carried the president down a staircase, out of the playhouse, and into a first-floor room in a boardinghouse on Tenth Street. The president, fifty-six, was not expected to survive. Hoping he might speak before dying, more than a dozen people remained at his side through the night. They waited in vain. He never woke. He died in the morning, the first president of the United States to be killed while in office. Word of his death, spread by telegraph, was reported in newspapers on Saturday and mourned in churches on Sunday. “May we not have needed this loss,” declared one minister, “in which we gain a national martyr.”89 It was Easter.

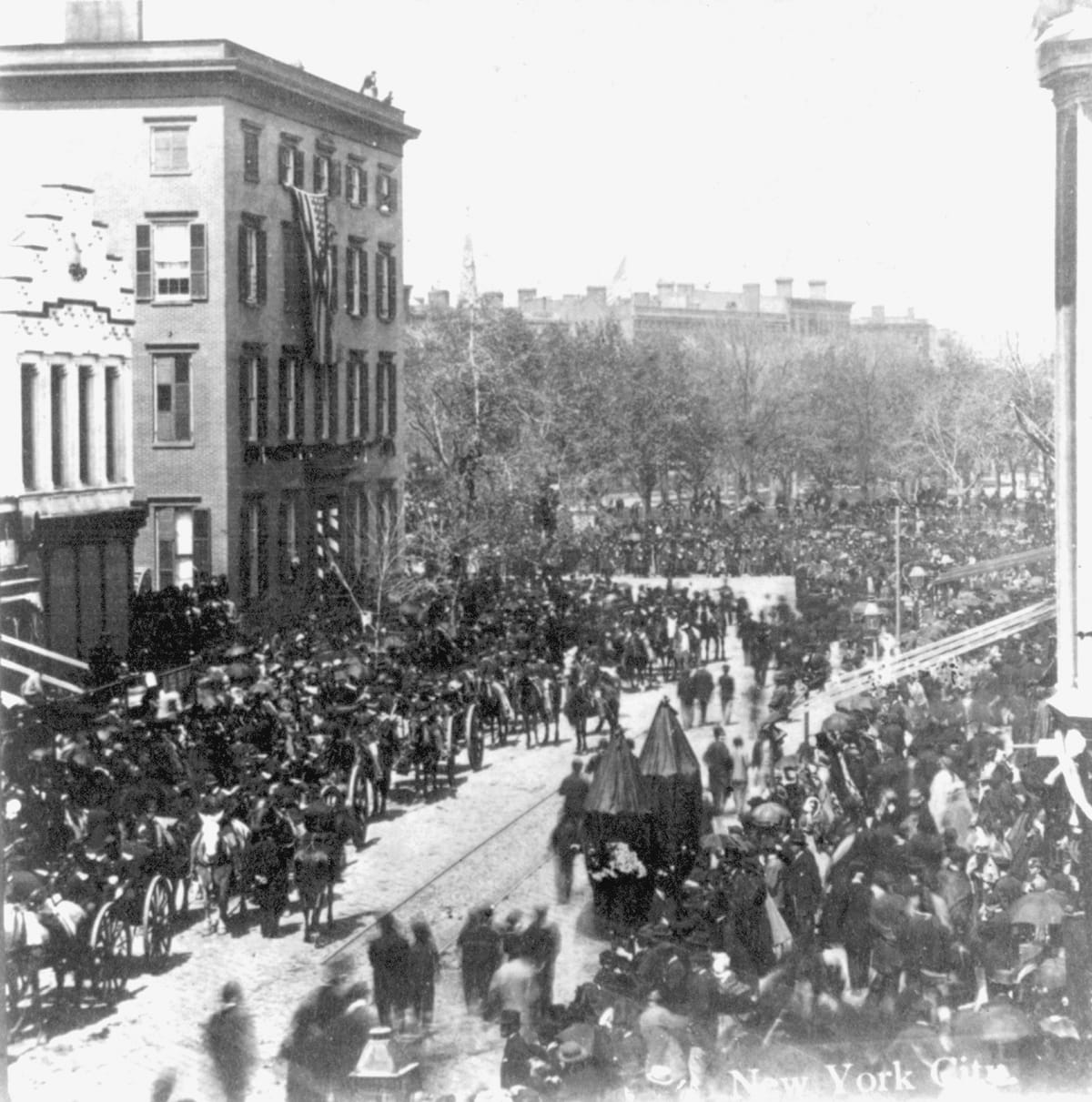

The death of Abraham Lincoln marked the birth of a new American creed: a religion of emancipation. It began with the mourning of a martyr. After four years of war, most Americans had black clothes ready to hand, the women their widow’s weeds, the men their black cloaks and armbands. At the White House, the doctors who conducted the autopsy kept relics, one wrapping in paper “a splinter of bone from the skull.” Lincoln had been a man of gigantic proportions, his body the subject of ceaseless fascination. The embalmers, arriving at the White House, promised, “The body of the President will never know decay.”90

Four days later, when the casket was put on display, vendors sold mementos as mourners gathered to get a glimpse of the dead president. “We have lost our Moses,” cried one elderly black woman waiting in line. “He was crucified for us,” another black mourner said in Pennsylvania. Not all Americans mourned. “Hurrah!” one South Carolinian wrote in her diary. “Old Abe Lincoln has been assassinated!”91

Pallbearers carried Lincoln’s casket onto a funeral train that snaked across the country, through fields and towns, for twelve days and nights. On May 4, 1865, his body was carried into a temporary vault in Spring-field, Illinois, until a more permanent memorial could be built, a granite obelisk above a marble sarcophagus.92 If he had uttered no dying words, he had left many last words, forever remembered, and etched in stone.

With the nation still draped in black, the Thirteenth Amendment, Lincoln’s last legacy, went to the states. When it was finally ratified, on December 6, 1865, one California congressman declared, “The one question of the age is settled.”93 A great debate had ended. A terrible war had been won. Slavery was over. But the unfinished work of a great nation remained undone: the struggle for equality had only just begun.

Lincoln would remain a man trapped in time, in the click of a shutter and by the trigger of a gun. In mourning him, in sepia and yellow, in black and white, beneath plates of glinting glass, Americans deferred a different grief, a vaster and more dire reckoning with centuries of suffering and loss, not captured by any camera, not settled by any amendment, the injuries wrought on the bodies of millions of men, women, and children, stolen, shackled, hunted, whipped, branded, raped, starved, and buried in unmarked graves. No president consecrated their cemeteries or delivered their Gettysburg address; no committee of arrangements built monuments to their memory. With Lincoln’s death, it was as if millions of people had been crammed into his tomb, trapped in a vault that could not hold them.