Nine

OF CITIZENS, PERSONS, AND PEOPLE

WHAT IS A CITIZEN? BEFORE THE CIVIL WAR, AND for rather a long time afterward, the government of the United States had no certain answer to that question. “I have often been pained by the fruitless search in our law books and the records of our courts for a clear and satisfactory definition of the phrase ‘citizen of the United States,’” Lincoln’s exasperated attorney general wrote in 1862.1 In 1866, Congress charged two legal scholars with discovering the definition. “The word citizen or citizens is found ten times at least in the Constitution of the United States,” one scholar wrote to the other, “and no definition of it is given anywhere.”2

Congress raised the question while deliberating over the consequences of emancipation: millions of people once held as slaves had been freed. What it would mean for them to become citizens would depend, in part, on the meaning of “citizen.” On this score, the Constitution proved maddeningly vague, referring to citizenship chiefly as a requirement for running for office, and in relation to the status of immigrants. Article II, Section 1, decreed, “No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President.” But even so seemingly straightforward a statement turned out to be murky. The words “natural born” were added only at the last minute, without recorded debate, after John Jay wrote a letter to George Washington suggesting that it might be “wise and seasonable to provide a strong check to the admission of foreigners into the administration of our national government and to declare expressly that the commander in chief of the American army shall not be given to, nor devolve on, any but a natural born citizen.”3 What and who is a “natural born citizen”? Jay didn’t say.

Under English common law, a “natural born subject” is a person born within the king’s realm or, depending on the circumstances, outside the king’s realm, but to the king’s subjects. A natural born citizen, though, isn’t quite the same thing as a natural born subject, not least because most U.S. laws did not discriminate between “natural born” and “naturalized” citizens, since Americans—immigrants and the children of immigrants—rejected the fealty of blood. In Federalist No. 52, Madison explained that anyone interested in running for Congress need only have been a U.S. citizen for seven years, because “the door of this part of the federal government is open to merit of every description, whether native or adoptive, whether young or old, and without regard to poverty or wealth, or to any particular profession of religious faith.”4 People running for Congress didn’t have to meet property requirements; they didn’t have to have been born in the United States; and they couldn’t be subjected to religious tests. This same logic applied to citizenship, and for the same reason: the framers of the Constitution understood these sorts of requirements as forms of political oppression. The door to the United States was meant to be open.

Before the 1880s, no federal law restricted immigration. And, despite periods of fervent nativism, especially in the 1840s, the United States welcomed immigrants into citizenship, and valued them. After the Civil War, the U.S. Treasury estimated the worth of each immigrant as equal to an $800 contribution to the nation’s economy, eliciting a protest from Levi Morton, a congressman from New York, that this amount was far too low. On the floor of the House, Morton asked, “what estimate can we place upon the value to the country of the millions of Irishmen and Germans to whom we largely owe the existence of the great arteries of commerce extending from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the results of that industry and skill which have so largely contributed to the wealth and property of the country?”5

Plainly, whatever else could be said of American citizenship, the idea was both liberal and capacious. Article IV, Section 2, of the Constitution established that “citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states,” a stipulation that Alexander Hamilton believed to be “the basis of the Union.”6 A citizen of one state was the equal of a citizen from another state. But what made these people citizens? Under what conditions were residents not citizens? And what, exactly, were the privileges and immunities of citizenship?

Nineteenth-century politicians and political theorists interpreted American citizenship within the context of an emerging set of ideas about human rights and the authority of the state, holding dear the conviction that a good government guarantees everyone eligible for citizenship the same set of political rights, equal and irrevocable. Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner stated this view squarely in 1849, while discussing the constitution of his home state: “Here is the Great Charter of every human being drawing vital breath upon this soil, whatever may be his condition, and whoever may be his parents. He may be poor, weak, humble, or black,—he may be of Caucasian, Jewish, Indian, or Ethiopian race,—he may be of French, German, English, or Irish extraction; but before the Constitution of Massachusetts all these distinctions disappear. . . . He is a MAN, the equal of all his fellow-men. He is one of the children of the State, which, like an impartial parent, regards all its offspring with an equal care.”7

The practice fell short of the ideal. On the one hand, all citizens, whether natural born or naturalized, were eligible to run for Congress, no federal laws restricted immigration, and all citizens were, at least theoretically, political equals, but on the other hand, no small number of laws and customs restricted citizenship. The Naturalization Act passed in 1798 extended the residency period required for an immigrant to become a citizen from five to fourteen years. That period was set back to five years in 1802, but under the terms of a law that declared that only a “free white person” could become a citizen. In 1857, in Dred Scott, the Supreme Court considered the question of black citizenship, asking, “Can a negro whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?” Its resounding answer was no. And the citizenship of women was of such a limited scope that in 1859, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote bitterly to Susan B. Anthony: “When I pass the gate of the celestials and good Peter asks me where I wish to sit, I will say, ‘Anywhere so that I am neither a negro nor a woman. Confer on me, great angel, the glory of White manhood, so that henceforth I may feel unlimited freedom.’”8

Adding to the confusion, restrictions on citizenship were unevenly enforced, as is made clear in the evidence of passport applications. The United States issued its first passport in 1782, but for a long time passports were issued not only by the federal government but also, and more usually, by states and cities, by governors, by mayors, and even by neighborhood notary publics. Moreover, not all citizenship documents took the form of passports. Black sailors were commonly issued something known as a “seaman’s protection certificate,” declaring that the bearer was a “Citizen of the United States of America”; Frederick Douglass used one of these certificates to make his escape from slavery.9 (There existed, too, in the land of slavery, a proof of identity that served more like a certificate of noncitizenship, an antipassport, a “slave pass”: a paper signed by a slave owner, needed by any enslaved person moving through land controlled by slave patrols, armed bands of white men formed into militias.) A black man, identified as a “free person of color”—a term adapted from the French gens de couleur libres, and regularly used in the United States beginning in 1810—first obtained a passport in 1835, but that same year the Supreme Court considered the question of whether a passport is also a proof of citizenship and decided that it was not.10

This hodgepodge only gradually yielded to a more uniform system. In 1856, Congress passed a law declaring that only the secretary of state “may grant and issue passports,” and that only citizens could obtain them. In August of 1861, Lincoln’s secretary of state, William Seward, issued this order: “Until further notice, no person will be allowed to go abroad from a port of the United States without a passport either from this Department or countersigned by the Secretary of State.” From then until the end of the war, this restriction was enforced; its aim was to prevent men from leaving the country in order to avoid military service. In 1866, a State Department clerk wrote that, in the issuing of passports, “there is no distinction made in regard to color,” a policy well ahead of federal citizenship law, but it was just this sort of thing that led Congress to send those two legal scholars into the law books, looking, in vain, for a definition of the word “citizen.”11

The Civil War raised fundamental questions not only about the relationship between the states and the federal government but also about citizenship itself and about the very notion of a nation-state. What is a citizen? What powers can a state exert over its citizens? Is suffrage a right of citizenship, or a special right, available only to certain citizens? Are women citizens? And if women are citizens, why aren’t they voters? What about Chinese immigrants, pouring into the West? They were free. Were they, under American law, “free white persons” or “free persons of color” or some other sort of persons?

In the decades following the war, these questions would be addressed by a new party system and a new political order, while a newly empowered and authorized federal government supported the growth of industrial capitalism, which in turn produced inequalities of income and wealth that shook the foundation of the Republic. In that new political order, corporations would claim to be, in the eyes of the law, “persons,” and the dispossessed, the farmers and factory workers who were left behind, would found a political party that insisted on their preeminent authority as “the people.”

In 1866, Congress searched in vain for a well-documented definition of the word “citizen.” Over the next thirty years, that definition would become clear, and it would narrow. In 1896, the U.S. passport office, in the Department of State, which had grown to thousands of clerks, began processing applications according to new “Rules Governing the Application of Passports,” which required evidence of identity, including a close physical description

Age, _____ years; stature, _____ feet _____ inches (English measure); forehead, _____; eyes, _____; nose, _____; mouth, _____; chin, _____; hair, _____; complexion, _____; face, _____

as well as affidavits, signatures, witnesses, an oath of loyalty, and, by way of an application fee, one dollar.12

In the unruly aftermath of the Civil War, the citizen was defined, described, measured, and documented. And the modern administrative state was born.

I.

THE UNION’S DEFEAT of the Confederacy granted to the federal government unprecedented powers. The government exerted over the former soldiers of the Confederacy the powers of a victor over the vanquished. Over former slaves, it exerted powers designed to guarantee civil rights, in an attempt to thwart the efforts of Southern states, which were determined to deny those rights to freedmen and women.

Long before the war ended, black men and women tried to anticipate and influence the government’s postwar plans. Their priorities were clear: citizenship and property. In March 1863, Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s secretary of war, established the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission. Its investigators reported that “the chief object of ambition among the refugees is to own property, especially to possess land, if it only be a few acres.” In October 1864, in Syracuse, New York, the National Convention of Colored Men called for “full measure of citizenship” for black men—not women—and for legislative reforms that included allowing “colored men from all sections of the country” to settle on lands granted to citizens by the federal government through the Homestead Act. The Homestead Act, signed into law in 1862, had made available up to 160 acres of “unappropriated public lands” to individuals or heads of families who would farm them for five years and then pay a small fee. Thaddeus Stevens, a craggy-faced Pennsylvanian, led the self-styled Radical Republicans, that wing of the party staunchly committed to reconstructing the political order of Southern society. Stevens, who had been chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee under Lincoln, wanted to confiscate and distribute nearly four hundred million acres of Confederate land from some seventy thousand of the Confederacy’s “chief rebels,” and distribute forty acres to every adult freedman. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (more generally known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) supplied food and clothing to war refugees and to aid the settlement of freed people but, at freedmen’s conventions, rumors spread that the bureau intended to give each freedman forty acres and a mule. “I picked out my mule,” Sam McAllum, a Mississippi ex-slave later told an interviewer. “All of us did.”13

As the war neared its close, Congress debated how to govern the peace. What should happen to the leaders of the Confederacy? Would they still have the rights of citizens? What should happen to their property? Thaddeus Stevens insisted that the federal government had to treat the former Confederacy as “a conquered people” and reform “the foundation of their institutions, both political, municipal and social,” or else “all our blood and treasure have been spent in vain.”14

But Lincoln was opposed to a vindictive peace, fearing that it would prevent the nation from binding its wounds. He proposed, instead, the so-called 10 percent plan, which included pardoning Confederate leaders and allowing a state to reenter the Union when 10 percent of its voters had taken an oath of allegiance. Radical Republicans in Congress rejected that plan and, at the end of 1864, passed the Wade-Davis Bill, which required a majority of voters to swear that they had never supported the Confederacy, and which would have meant the complete disenfranchisement of all former Confederate leaders and soldiers. Lincoln vetoed the bill. He did, however, eventually agree to place the South under military rule.

After Lincoln was assassinated and his vice president, Andrew John-son, assumed the presidency, Johnson, a square-built former governor of Tennessee, attempted to turn the tide of the postwar plan, plotting a course markedly different from Lincoln’s. Lincoln had chosen Johnson as his running mate in an effort to offer reassurance to border states. With Lincoln’s death, Johnson set for himself the task of protecting the South. He talked not about “reconstruction” but about “restoration”: he wanted to bring the Confederate states back into the Union as fast as possible, and to leave matters of citizenship and civil rights to the states to decide.

Freedmen continued to press their claims: Union Leagues, Republican clubs, and Equal Rights Leagues held “freedmen’s conventions,” demanding full citizenship, equal rights, suffrage, and land, and complaining about the amnesties and pardons issued by Johnson to former Confederate leaders. “Four-fifths of our enemies are paroled or amnestied, and the other fifth are being pardoned,” declared one assembly of blacks in Virginia, charging Johnson with having “left us entirely at the mercy of these subjugated but unconverted rebels in everything save the privilege of bringing us, our wives and little ones, to the auction block.”15 By the winter of 1865–66, Southern legislatures consisting of former secessionists had begun passing “black codes,” new, racially based laws that effectively continued slavery by way of indentures, sharecropping, and other forms of service. In South Carolina, children whose parents were charged with failing to teach them “habits of industry and honesty” were taken from their families and placed with white families as apprentices in positions of unpaid labor.16 Slavery seemed like a monster that, each time it was decapitated, grew a new head.

And then rose the Ku Klux Klan, founded in Tennessee in 1866, a fraternal organization of Confederate veterans who dressed in white robes, in order to appear, according to one original Klansman, as “the ghosts of the Confederate dead, who had arisen from their graves in order to wreak vengeance.” The Klan really was a resurrection—not of the Confederate dead but of the armed militias that had long served as slave patrols that for decades had terrorized men, women, and children with fires, ropes, and guns, instruments of intimidation, torture, and murder.17

On February 2, 1866, the Senate passed the Civil Rights Act, the first federal law to define citizenship. “All persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States,” it began. It declared that all citizens have a right to equal protection under the law; its provisions included extending the Freedmen’s Bureau. Five days after the Senate vote—a crucial, pivotal moment—Frederick Douglass visited the White House to seek the president’s support during an extraordinarily tense meeting, a confrontation as remarkable and historic as any that has happened in those halls.

“You are placed in a position where you have the power to save or destroy us,” Douglass told the president. “I mean our whole race.”

Johnson, in a rambling, evasive, and self-justifying speech, assured Douglass that he was a friend to black people. “I have owned slaves and bought slaves,” he said, “but I never sold one.” In truth, Johnson had no intention of taking a stand against black codes or debating equal rights or signing a Civil Rights Act. After Douglass left, Johnson scoffed to an aide, “He’s just like any nigger, and he would sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”18

In March, after the House passed the Civil Rights Act, Johnson vetoed it. In April, Congress, wielding its power, overrode Johnson’s veto. A landmark in the history of the struggle for power between the executive and legislative branches of the federal government, Congress’s stand marked the first time that it had ever overridden a presidential veto.

As the federal government acted to define citizenship and protect civil rights, Johnson tried to halt these changes but proved unable to triumph over the Radical Republicans who dominated Congress and stood at the center of national power.19 As Radical Republicans turned to the question of voting, they began work on constitutional amendments designed to prevent the disenfranchisement of freedmen: the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. There were ideals at stake, of course: making good on the promise of the nation’s founding documents and the cause for which the war was fought. But there was also the matter of raw politics. The abolition of slavery rendered the three-fifths clause obsolete. With each black man, woman, and child counting not as three-fifths of a person but as five-fifths, Southern states gained seats in Congress. Black men, if they were able to vote, were almost guaranteed to vote Republican. For Republicans in Congress to maintain their hold on power, then, they needed to be sure the Southern states didn’t stop black men from voting.

In pursuing this end, Radical Republicans were supported by the legions of women who had fought for abolition and emancipation and for women’s rights. After Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and after ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony had begun to fight, equally hard, for the next amendment, which they expected to guarantee the rights and privileges of citizenship for all Americans—including women.

The Fourteenth Amendment, drafted by the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, marked the signal constitutional achievement of a century of debate and war, of suffering and struggle. It proposed a definition of citizenship guaranteeing its privileges and immunities, and insuring equal protection and due process to all citizens. “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside,” it began. “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”20

During the drafting of the amendment, the committee betrayed the national phalanx of women who for decades had fought for abolition and for black civil rights by proposing to insert, into the amendment’s second section, a provision that any state that denied the right to vote “to any of the male inhabitants of such state” would lose representation in Congress. “Male” had never before appeared in any part of the Constitution. “If that word ‘male’ be inserted,” Stanton warned, “it will take us a century at least to get it out.”21 She was not far wrong.

Women protested. “Can any one tell us why the great advocates of Human Equality . . . forget that when they were a weak party and needed all the womanly strength of the nation to help them on, they always united the words ‘without regard to sex, race, or color’?” asked Ohio-born reformer Frances Gage. Charles Sumner offered this answer: “We know how the Negro will vote, but are not so sure of the women.” How women would vote was impossible to know. Would black women vote the way black men voted? Would white women vote like black women? Republicans decided they’d rather not find out. “This is the negro’s hour,” they told women. “May I ask just one question based on the apparent opposition in which you place the negro and the woman?” Stanton asked Wendell Phillips. “My question is this: Do you believe the African race is composed entirely of males?”22

Over the protests of women, the word “male” stayed in the draft. But another term raised more eyebrows. “All persons born or naturalized in the United States . . . are citizens.”23 Why “persons”? To men who were keen to deny women equal rights, “persons” seemed oddly expansive. Was there a way in which this amendment could be read, even with the word “male,” to support female claims for equal rights?

During the Senate debate, Jacob Howard, a Republican from Michigan, explained that the amendment “protects the black man in his fundamental rights as a citizen with the same shield which it throws over the white man.” Howard assured his fellow senators that the amendment most emphatically did not guarantee black men the right to vote (even though he wished that it did); it only suggested, without providing any mechanism for enforcement, that states that barred men from voting would lose representation in Congress. On this point, Howard quoted James Madison, who’d written that “those who are to be bound by laws, ought to have a voice in making them.” From the floor, Reverdy Johnson, a Democrat from Maryland, rose to ask how far such a proposition could logically be extended, especially given the amendment’s use of the word “person”:

MR. JOHNSON: Females as well as males?

MR. HOWARD: Mr. Madison does not say anything about females.

MR. JOHNSON: “Persons.”

MR. HOWARD: I believe Mr. Madison was old enough and wise enough to take it for granted that there was such a thing as the law of nature which has a certain influence even in political affairs, and that by that law women and children are not regarded as the equals of men.24

It would take a century for this matter to reach Congress again, and then only accidentally, during the debate over the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Yet even with the Fourteenth Amendment’s extension of certain protections only to “male inhabitants” and its narrowed understanding of the rights of persons, ratification was by no means assured. Andrew John-son opposed the amendment and urged Southern states not to ratify it. Only Tennessee ratified (always ambivalent about the Confederacy, and the last state to secede, Tennessee became the first readmitted to the Union). Meanwhile, in the fall of 1866, Radical Republicans were elected to Congress in huge numbers, cutting down Johnson at his knees. And yet, from his knees, still he swung at them. Republicans, deeming the expansion of federal power the only possible way to insure the civil rights of former slaves, passed four Reconstruction Acts. Johnson, swinging wildly, vetoed all four. Congress overrode each of his vetoes, crushing the president into the ground.

The Reconstruction Acts divided the former Confederacy into five military districts, each ruled by a military general. Each former rebel state was to draft a new constitution, which would then be sent to Congress for approval. In an act of constitutional coercion, Congress made readmission to the Union contingent on the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. Under the terms of Reconstruction, men who had been Confederate soldiers could not vote, but men who had been slaves could. In the former Confederacy, most white men who were able to vote were Democrats; 80 percent of eligible Republican voters were black men. Still, even with the protection of federal troops, black men were not always able to vote, especially as the Klan grew. Black men most often succeeded in casting ballots in the upper South. Ninety percent of black registered voters managed to vote in Virginia. In the deeper South, black men arrived early at the polls and in groups, often marching together, by prearrangement, to protect themselves against attack. One election supervisor from Alabama described the first day of voting in 1867: “there must have been present, near one thousand freedmen, many as far as thirty miles from their home, all eager to vote.”25

While the battle to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment raged on, black men participated in more than Election Day. Eight hundred black men served in state legislatures. They filled more than a thousand public offices, mostly in town and county government. A black man was, briefly, governor of Louisiana. “Now is the black man’s day—the whites have had their way long enough,” said one politician. A northern journalist visiting the South Carolina legislature wrote: “The body is almost literally a Black Parliament. . . . The Speaker is black, the Clerk is black, the door-keepers are black, the little pages are black, the chairman of the Ways and Means is black, and the chaplain is coal black.” Whites called it “Negro rule.”26

In Washington, Johnson struggled to regain his feet. Early in 1868, he tried to fire Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Radical Republican and Lincoln appointee. But Stanton, hardheaded and uncompromising, barricaded himself in his office for two months. The nation reeled from one constitutional crisis to the next. The House began impeachment proceedings against the president, charging him with violating a recently passed Tenure of Office Act. Congress voted to impeach, 126 to 47, but the Senate vote, 35–19, fell one vote shy of the two-thirds required. Johnson had survived, but impeachment, a constitutional gun that had never before been fired, had for the first time been loaded.27

The Fourteenth Amendment was finally ratified in the summer of 1868. That summer, Johnson failed to win the Democratic nomination for president, while Ohio-born Ulysses S. Grant, veteran of the War with Mexico and hero of the Civil War, won the Republican nomination, campaigning on the pledge “Let us have peace.” Black men who managed to vote despite the menace of the KKK nearly all voted for Grant.

Women tried to vote, too. Before the Fourteenth Amendment, women’s rights reformers had fought for women’s education and for laws granting to married women the right to control their own property; after the Fourteenth Amendment, the women’s rights movement became the women’s suffrage movement, which both narrowed and intensified it. In 1868, in a plan that was known as the New Departure, black and white women attempted to gain the right to vote by exercising it: they went to the polls and were arrested when they tried to cast ballots. During those same years, it became increasingly difficult for black men to vote, leading Congress to debate and propose yet another constitutional amendment, one that would raise still more questions about citizens, persons, and people, categories whose limits had long been tested by women and were being newly tested by immigrants from China.

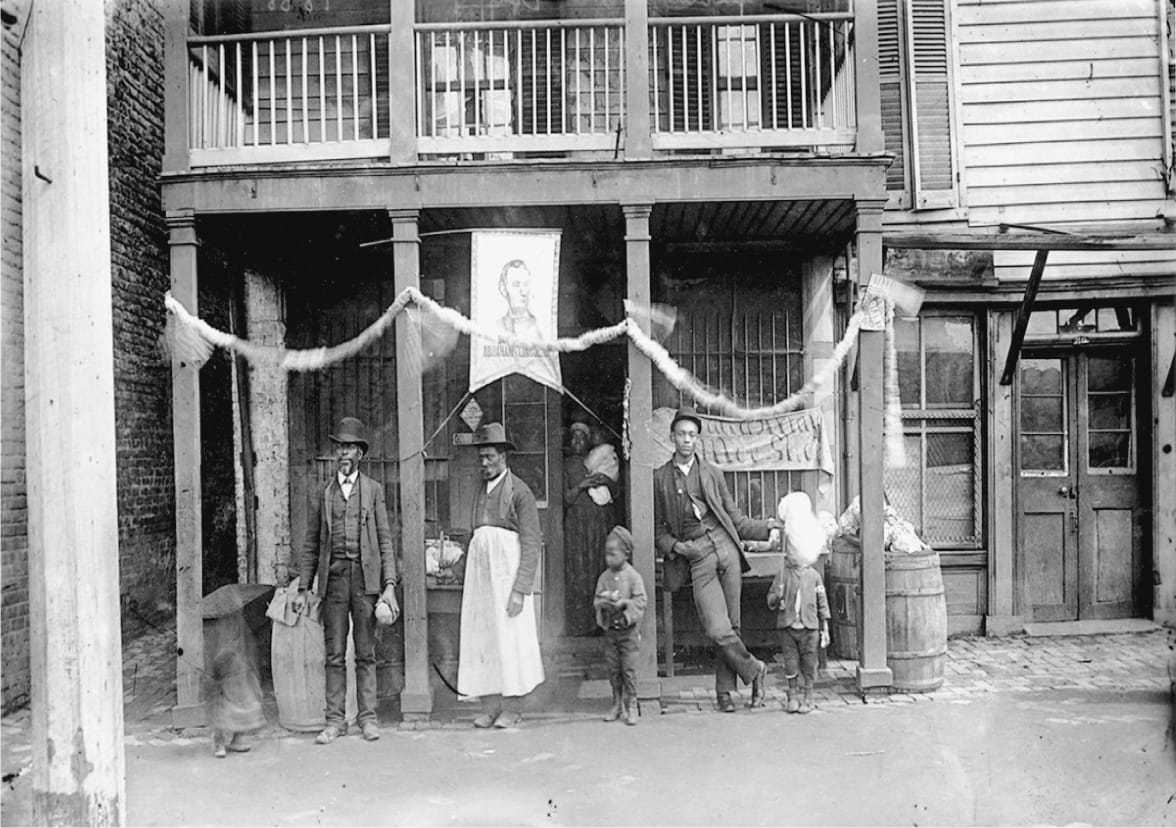

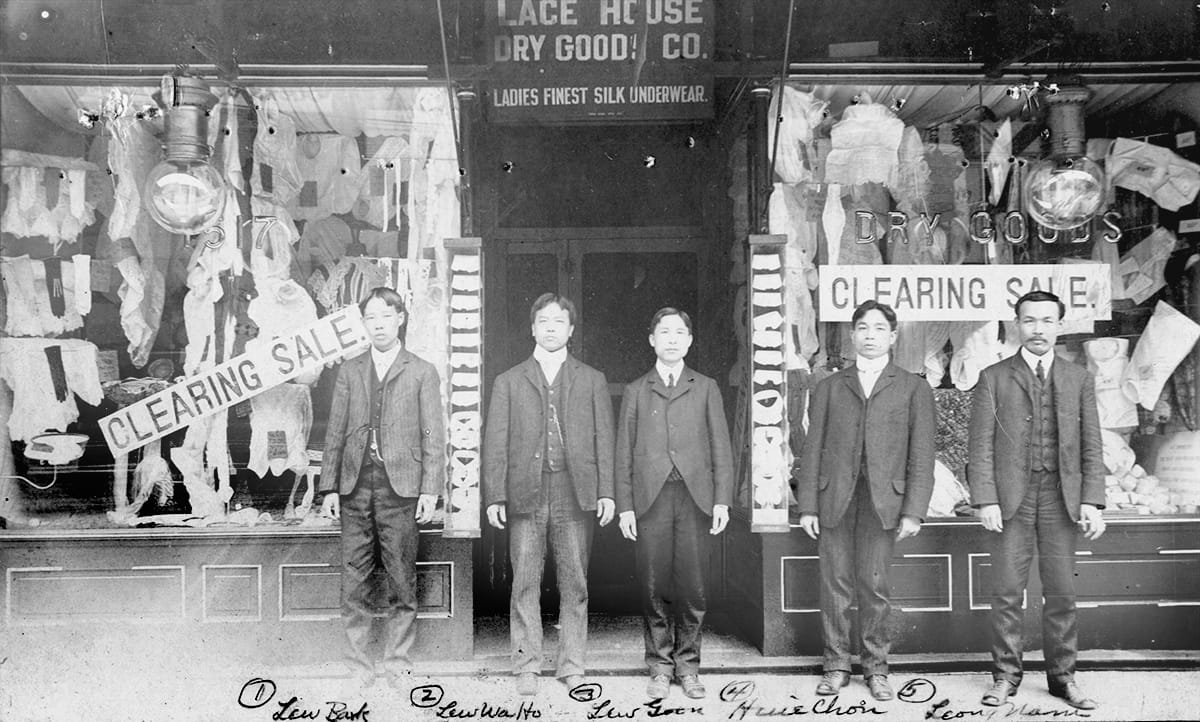

CHINESE IMMIGRANTS BEGAN arriving in the United States in large numbers during the 1850s, following the gold rush. In 1849, California had 54 Chinese residents; by 1850, 791; by 1851, more than 7,000; by 1852, about 25,000. Most came from Kwangtung Province and sailed from Hong Kong, sent by Chinese trading firms known as “the Six Companies.” Most were men. Landing in San Francisco, they worked as miners, first in California and then in Oregon, Nevada, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Colorado. In the federal census of 1860, 24,282 out of 34,935 Chinese toiled in mines. Although some Chinese immigrants left mining—and some were forced out—many continued to mine well into the 1880s, often working in sites abandoned by other miners. An 1867 government report noted that in Montana, “the diggings now fall into the hands of the Chinese, who patiently glean the fields abandoned by the whites.” Chinese workers began settling in Boise in 1865 and only five years later constituted a third of Idaho’s settlers and nearly 60 percent of its miners. In 1870, Chinese immigrants and their children made up nearly 9 percent of the population of California, and one-quarter of the state’s wage earners.28

Their rights, under state constitutions and statutes, were markedly limited. Oregon’s 1857 constitution barred “Chinamen” from owning real estate, while California barred Chinese immigrants from testifying in court, a provision upheld in an 1854 state supreme court opinion, People v. Hall, which described the Chinese as “a race of people whom nature has marked as inferior, and who are incapable of progress or intellectual development beyond a certain point, as their history has shown.”29

The Chinese American population was growing at its fastest clip in the 1860s, just as the federal government was debating the relationship between citizenship and race. The Fourteenth Amendment’s provision for birthright citizenship—anyone born in the United States is a citizen—made no racial restriction. Under its terms, the children of Chinese immigrants born in the United States were American citizens. As Lyman Trumbull, a senator from Illinois, said during the debates over the amendment, “the child of an Asiatic is just as much a citizen as the child of a European.”30 (This interpretation of the amendment was upheld in an 1898 ruling by the Supreme Court, in United States v. Wong Kim Ark.) Trumbull, who’d helped write the Thirteenth Amendment, was one of a very small number of men in Congress who talked about Chinese immigrants in favorable terms, describing them as “citizens from that country which in many respects excels any other country on the face of the globe in the arts and sciences, among whose population are to be found the most learned and eminent scholars in the world.” More typical was the view expressed by William Higby, a Republican congressman from California, and a onetime miner. “The Chinese are nothing but a pagan race,” Higby said in 1866. “You cannot make good citizens of them.”31

If the children of Chinese immigrants were U.S. citizens, what about the immigrants themselves? Chinese immigrants’ most significant protection against discrimination in western states was an 1868 treaty between China and the United States. It provided that “Chinese subjects visiting or residing in the United States, shall enjoy the same privileges, immunities, and exemptions in respect to travel or residence, as may there be enjoyed by the citizens or subjects of the most favored nation.”32 That treaty, though, didn’t make Chinese immigrants into citizens; it only suggested that they be treated like citizens.

And what about the voting rights of U.S.-born Chinese Americans? Much turned on the Fifteenth Amendment, proposed early in 1869. While the aim of the amendment was to guarantee African Americans the right to vote and hold office, its language inevitably raised the question of Chinese citizenship and suffrage. Opponents of the amendment found its entire premise scandalous. Garrett Davis, a Democratic senator from Kentucky, fumed, “I want no negro government; I want no Mongolian government; I want the government of the white man which our fathers incorporated.”33 Michigan’s Jacob Howard urged that the Fifteenth Amendment specifically bar Chinese men by introducing language explaining that the amendment only applied to “citizens of the United States of African descent.”34 Presumably, Howard calculated that this revision, which amounted to Chinese exclusion, would improve the chances of the amendment’s passage and ratification. But congressional enthusiasm for immigration thwarted his proposal. George F. Edmunds of Vermont called Howard’s revision to the amendment an outrage, pointing out that his new language would enfranchise black men only by leaving out “the native of every other country under the sun.”35

Rare was the American orator who could devise, out of a debate mired in invective, an argument about citizenship that rested on human rights. But Frederick Douglass, at the height of his rhetorical powers, made just this argument in a speech in Boston in 1869. Who deserves citizenship and political equality? Not people of one descent or another, or of one sex or another, but all people, Douglass insisted. “The Chinese will come,” he said. “Do you ask, if I favor such immigration, I answer I would. Would you have them naturalized, and have them invested with all the rights of American citizenship? I would. Would you allow them to vote? I would.” Douglass spoke about what he called a “composite nation,” a strikingly original and generative idea, about a citizenry made better, and stronger, not in spite of its many elements, but because of them: “I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours.”36

Douglass’s expansiveness, his deep belief in equality, did not prevail. In its final language, the Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, declared that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”37 It neither settled nor addressed the question of whether Chinese immigrants could become citizens. And, in practice, it hardly settled what it proposed to settle—the voting rights of black men—for whom voting became only more difficult, and more dangerous, in the face of a rising tide of terrorism. Even though a Republican-controlled Congress passed the Force Act of 1870 and the Klan Act of 1871, making it illegal to restrict or interfere with suffrage, the Klan only increased its efforts to take back the South, rampaging across the land.

Nor did the Fifteenth Amendment settle the question of whether women could vote. On the one hand, it didn’t guarantee women that right, since it didn’t bar discrimination by sex (only discrimination by “race, color, or previous condition of servitude”); on the other hand, it didn’t suggest that women couldn’t vote. What it did do was to divide the equal rights movement, splitting the American Equal Rights Association, a civil rights organization, into two, Stanton and Anthony founding the National Woman Suffrage Association, which did not support the amendment, and the veteran reformer Lucy Stone and the poet Julia Ward Howe founding the rival American Woman Suffrage Association, which did. (The rift would be mended when the two organizations merged in 1890 as the National American Woman Suffrage Association.)

In 1870, five black women were arrested for voting in South Carolina. But by now, women had decided to test the limits of female citizenship not only by voting but also by running for office. Victoria Woodhull, a charismatic fortune-teller from Ohio who’d attended a suffrage convention in 1869, moved to New York, and reinvented herself as a stockbroker, became the first woman to run for president. She ran as a “self-nominated” candidate of the party she helped create, the Equal Rights Party. In 1871 she announced, “We are plotting revolution.” Woodhull said she ran “mainly for the purpose of drawing attention to the claims of woman to political equality with man.” Ingeniously, she argued that women had already had the right the vote, under the privileges and immunities clause of the Constitution, an argument she brought before a House Judiciary committee, making her the first woman to address a congressional committee. “As I have been the first to comprehend these Constitutional and legal facts, so am I the first to proclaim, as I now do proclaim to the women of the United States of America that they are enfranchised.” Woodhull’s candidacy ended in ignominy. She spent Election Day in prison on charges of obscenity, and in the end, the Supreme Court ruled against her interpretation of the Constitution, deciding, in Minor v. Happersett, that the Constitution “did not automatically confer the right to vote on those who were citizens.”38

Woodhull’s adventurous, glamorous, and shocking campaign helped ensure that the question commanded attention, even if that attention was, at best, polite. “The honest demand of any class of citizens for additional rights should be treated with respectful consideration,” Republicans announced at their 1872 convention, a position that Stanton called not a plank but a splinter. At the party’s 1876 convention, marking the centennial of the Declaration of Independence, Sarah Spencer, of the National Woman Suffrage Association, said, “In this bright new century, let me ask you to win to your side the women of the United States.” She was hissed. At that same convention, Frederick Douglass, his raven hair now streaked with gray, became the first black person to speak before any nominating convention. Spencer had pleaded. Douglass pressed. “The question now is,” he said, eyeing the crowd of rowdy delegates, silenced by his booming voice, “Do you mean to make good to us the promises in your constitution?”39

Their answer, apparently, was no. That fateful year, a century after the nation was founded, Reconstruction failed, felled by the seedy compromises, underhanded dealings, personal viciousness, and outright fraud of small-minded and self-gratifying men. Grant, dissuaded from running for a third term, stepped down in 1876. Roscoe Conkling, a big, bearded boxer and New York senator, was so sure he’d get the party’s nomination that he picked his vice president and a motto—“Conkling and Hayes / Is the ticket that pays”—only to be defeated by his erstwhile running mate, the lackluster former governor of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes. When the Democrats met in St. Louis—the first time a convention was held west of the Mississippi—a delegation opposed to the nomination of the New York governor and dogged reformer Samuel Tilden hung a giant banner from the balcony of the Lindell Hotel. It read, “The City of New York, the Largest Democratic City in the Union, Uncompromisingly Opposed to the Nomination of Samuel J. Tilden for the Presidency Because He Cannot Carry the State of New York.”40 Tilden won the nomination anyway and, in the general election, he won the popular vote against Hayes. Unwilling to accept the result of the election, Republicans disputed the returns in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Eventually, the decision was thrown to an electoral commission that brokered a nefarious compromise: Democrats agreed to throw their support behind the man ever after known as Rutherfraud B. Hayes, so that he could become president, in exchange for a promise from Republicans to end the military occupation of the South. For a minor and petty political win over the Democratic Party, Republicans first committed electoral fraud and then, in brokering a compromise, abandoned a century-long fight for civil rights.

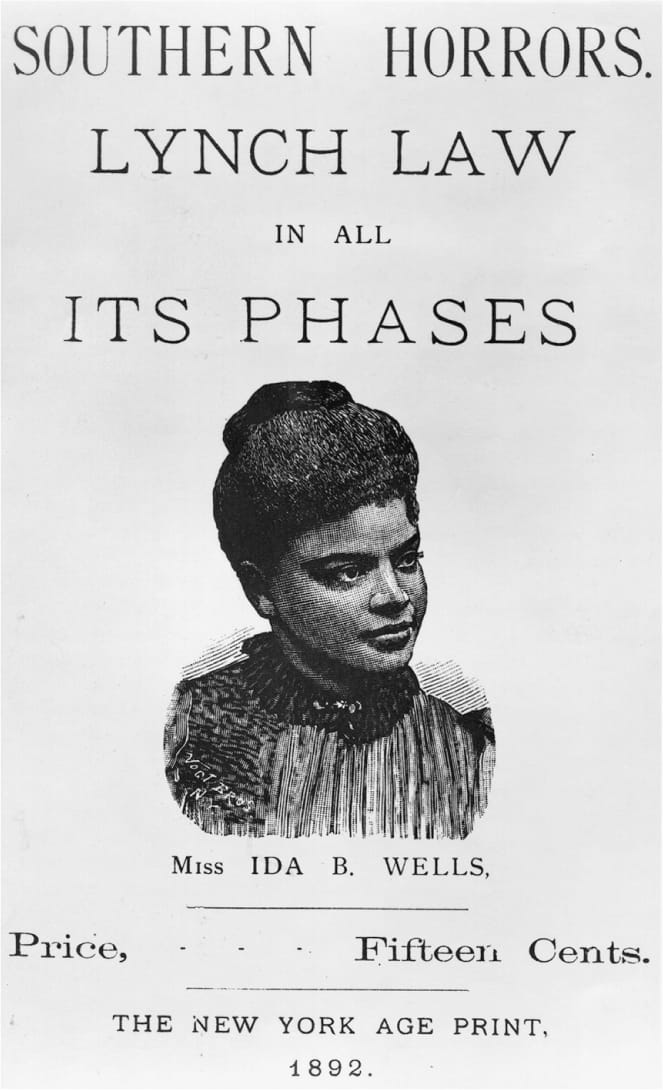

Political equality had been possible, in the South, only at the barrel of a gun. As soon as federal troops withdrew, white Democrats, calling themselves the “Redeemers,” took control of state governments of the South, and the era of black men’s enfranchisement came to a violent and terrible end. The Klan terrorized the countryside, burning homes and hunting, torturing, and killing people. (Between 1882 and 1930, murderers lynched more than three thousand black men and women.) Black politicians elected to office were thrown out. And all-white legislatures began passing a new set of black codes, known as Jim Crow laws, that segregated blacks from whites in every conceivable public place, down to the last street corner. Tennessee passed the first Jim Crow law, in 1881, mandating the separation of blacks and whites in railroad cars. Georgia became the first state to demand separate seating for whites and blacks in streetcars, in 1891. Courthouses provided separate Bibles. Bars provided separate stools. Post offices mandated separate windows. Playgrounds had separate swings. In Birmingham, for a black child to play checkers with a white child in a public park became a crime.41 Slavery had ended; segregation had only begun.

II.

MARY E. LEASE crossed the plains like a tornado. “Raise less corn and more hell,” she said. She could talk for hours, her audience rapt. She stood almost six feet tall. “Tall and raw-boned and ugly as a mud hen,” one reporter called her; “the people’s party Amazon,” said another. A writer who watched her said she had “a golden voice,” an extraordinary contralto; to listen to her was to be hypnotized. A founder and principal orator of the populist movement, Lease believed that after the Civil War the federal government had conspired with corporations and bankers to wrest political power from ordinary people, like farmers and factory workers. “There is something radically wrong in the affairs of this Nation,” Lease told a mesmerized crowd in 1891. “We have reached a crisis in the affairs of this Nation which is of more importance, more fraught with mighty consequence for the weal or woe of the American people, than was even that crisis that engaged the attention of the people of this Nation in the dark and bleeding years of civil strife.”42

Lease had known that civil strife in her heart and by her hearth. Born in 1850, the daughter of Irish immigrants, she’d lost her father, two brothers, and an uncle in the Civil War; her uncle died at Gettysburg and her father starved to death as a prisoner of war. She never forgave the South, or the Democratic Party (which she called, all her life, “the intolerant, vindictive, slavemaking Democratic Party”).43 Married in 1873, she raised four children and lost two more to early death while farming in Kansas and Texas, and taking in washing, and also writing, and studying law. What was this new crisis endangering the nation that she talked about in hundreds of speeches, to applause as loud as a torrent of rain hitting the roof of a barn? “Capital buys and sells to-day the very heart-beats of humanity,” she said. Democracy itself had been corrupted by it: “the speculators, the land-robbers, the pirates and gamblers of this Nation have knocked unceasingly at the doors of Congress, and Congress has in every case acceded to their demands.”44 The capitalists, she said, had subverted the will of the people.

The populist movement, marble in the flesh of American politics into the twenty-first century, started in the South and in the West. Lease and people like her drew on the agrarian republicanism of Thomas Jefferson and the common-man rhetoric of Andrew Jackson, but they also influenced the political commitments of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, serving as a bridge between populism and progressivism, the two great political reform movements that straddled the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.

Lease fought for the farmers and wage laborers whose political voices, she believed, were being shouted down by capitalists. But she also fought for women’s suffrage and for temperance and helped to diffuse a distinctive female political style—the moral crusade—throughout American politics. Prevented from entering the electorate, women who wanted to influence public affairs relied on forms of popular politics that, among men, were on the decline: the march, the rally, the parade. In the late nineteenth century, a curious reversal took place. Electoral politics, the politics men engaged in, became domesticated, the office work of education and advertising—even voting moved indoors. Meanwhile, women’s political expression moved to the streets. And there, at marches, rallies, and parades, women deployed the tools of the nineteenth-century religious revival: the sermon, the appeal, the conversion.45

The female political style left its traces in every part of American politics, nowhere more deeply than in the populist tradition. Beginning in the twentieth century, it would drive the modern conservative movement.

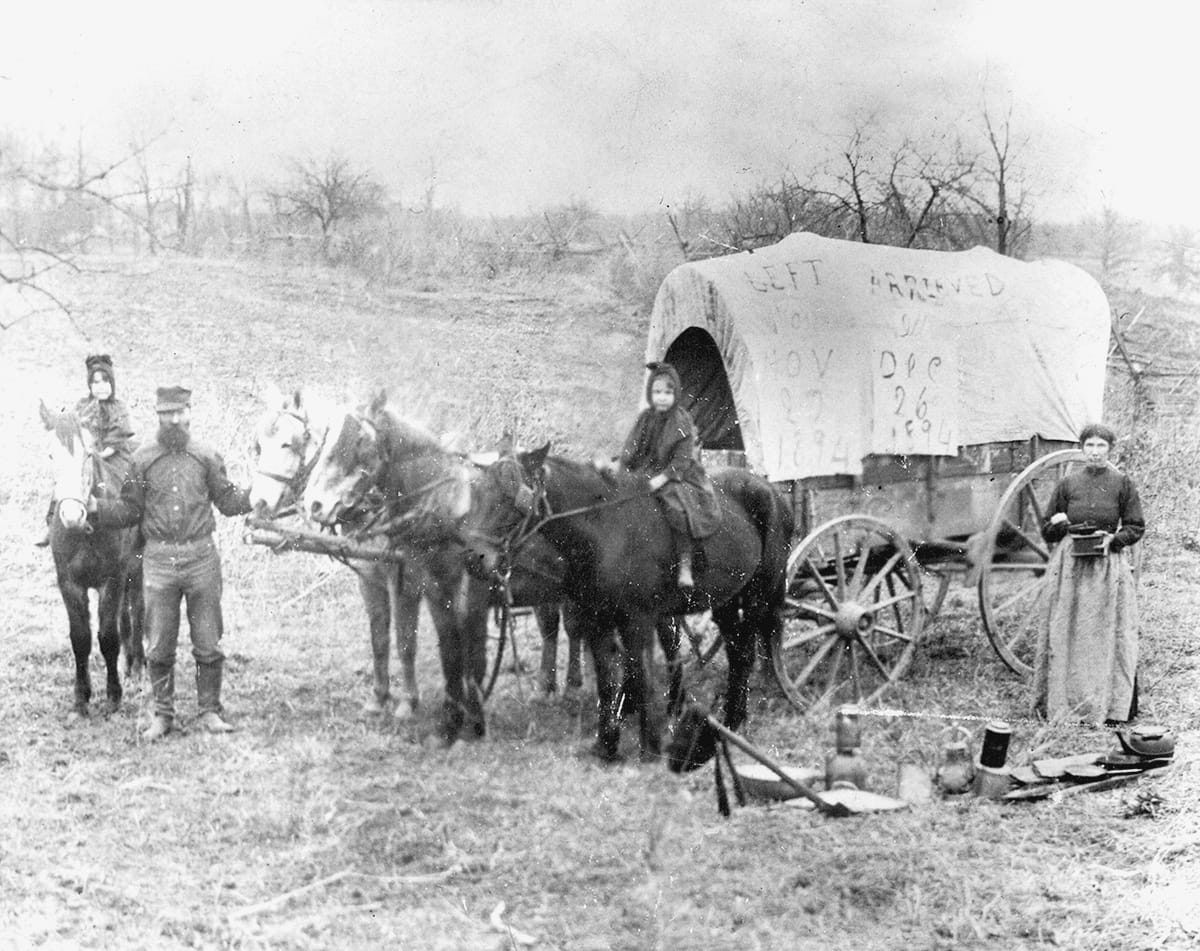

What Lease described as a conspiracy between the federal government and capitalists, especially railroad company owners and bankers, had its roots in the Civil War itself, and in the federal government’s shifting policy toward the West. Before the war, the controversy over slavery had limited federal involvement in the West, but when the South seceded, Democratic opposition in Congress disappeared, giving Republicans a free hand. Without Democrats fighting for slavery’s expansion, Republicans had made haste to bring the West into the Union, and to exert authority over its economic development. A Republican Congress had approved the organization of new territories: the Dakotas (1861), Nevada (1861), Arizona (1863), Idaho (1863), and Montana (1864). In 1862 alone, in addition to the Homestead Act, the Republican Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act (chartering railroad companies to build the line from Omaha, Nebraska, to Sacramento, California) and the National Bank Act (to issue paper money to pay for it all). After the war, political power moved from the states to the federal government and as the political influence of the South waned, the importance of the West rose. Congress not only sent to the states amendments to the Constitution that defined citizenship and guaranteed voting rights but also passed landmark legislation involving the management of western land, the control of native populations, the growth and development of large corporations, and the construction of a national transportation infrastructure.

The independent farmer—the lingering ideal of the Jeffersonian yeoman—remained the watchword of the West, but in truth, the family farming for subsistence, free of government interference, was far less common than a federally subsidized, capitalist model of farming and cattle raising for a national or even an international market. The small family farm—Jefferson’s republican dream—was in many parts of the arid West an environmental impossibility. Much of the property distributed under the terms of the Homestead Act, primarily in the Great Basin, was semi-arid, the kind of land on which few farmers could manage a productive farm with only 160 acres. Instead, Congress typically granted the best land to railroads, and allowed other, bigger interests to step in, buying up large swaths for agricultural business or stock raising and fencing it in, especially after the patenting of barbed wire in 1874.46

With the overwhelming force of the U.S. Army, the federal government opened land for settlement by suppressing Indian insurrections, including a rebellion of more than six thousand Dakota Sioux. In measures that began as exigencies of war, the federal government forced native peoples off their land while providing corporations with incentives to build railroads. In a single ten-year span, Congress granted more than one hundred million acres of public lands to railroad companies. In 1870, only two million non-Indians lived west of the Missouri River; by 1890, that number had risen to more than ten million.47

As railroads owned by large corporations extended their tentacles like so many octopuses across vast lands owned by giant companies, the big business of beef-cattle raising grew. Railroads made it possible to carry massive herds to market in cities like Chicago, St. Louis, Omaha, and Kansas City. Buffalo that had long thrived on those lands were slaughtered nearly to extinction and replaced by Texas longhorns, five million of which were driven to railroad terminals in 1865 by cowboys of all backgrounds—white, black, Mexican, and Indian. By 1880, two million cattle were slaughtered in Chicago alone. In 1885, an American economist tried to reckon the extraordinary transformation wrought by what was now 200,000 miles of railroad, more than in all of Europe. It was possible to move one ton of freight one mile for less than seven-tenths of one cent, “a sum so small,” he wrote, “that outside of China it would be difficult to find a coin of equivalent value to give a boy as a reward for carrying an ounce package across a street.”48

The transformation of the West fueled the American economy, but it also produced instability, especially given rampant land speculation and the popularity of railroad stocks and bonds, novel financial instruments issued and managed by the federal government. That instability contributed to a broader set of political concerns that became Mary Lease’s obsession, concerns known as “the money question,” and traceable all the way back to Hamilton’s economic plan: Should the federal government control banking and industry?

Federal land and railroad projects required vast amounts of spending at a time when Americans were uncertain how to pay their debts. Like the Continental currency printed during the Revolutionary War, greenbacks, issued during the Civil War and not backed up by gold, soon became all but valueless. After the war, gold-bugs argued for the collection and retirement of the greenbacks and the establishment of a gold standard; “silverites” supported a standard of specie-backed currency but not specifically gold. In 1869, Congress passed the Public Credit Act, promising to pay back its own debt in specie or specie-backed notes. But with all its borrowing and intricate financial instruments, the federal government, especially the administration of Ulysses S. Grant, became notorious for corruption and bribery.

Matters reached a crisis point in 1873, for Mary Lease and for the country, too. That spring, Lease and her husband and children moved to Kingman, Kansas, onto land they’d acquired through the Homestead Act. The Leases got their Kansas land for free, but Mary’s husband, Charles, had to borrow hefty sums of money from a local bank to buy tools and pay land office fees. They lived in a sod house, where Mary pinned newspaper pages to the walls so that she could read while kneading dough. For a few months they scraped by, but within a year they were unable to repay their debts, and the bank repossessed their land.49 Life on a Kansas farm was like trying to raise corn on a beach of sand. Better to raise hell.

In suffering financial ruin the dire year of 1873, the Leases were not alone. Eighteen-seventy-three saw the worst financial disaster since the Panic of 1837. Blame for the collapse rests on the desk of a white-whiskered Philadelphia banker named Jay Cooke, the latest in a long line of scoundrels that went all the way back to William Duer, whose swindling brought on the Panic of 1792. Cooke had made a great deal of money during the Civil War, investing in federal war bonds and in the Northern Pacific Railway, chartered by Congress in 1864. His brother Henry had been placed in charge of the Freedman’s Savings Bank, chartered in 1865. Henry Cooke illegally invested the bank’s money—the savings of freedmen—in his brother’s railroad ventures. The proposed Northern Pacific was supposed to go through lands owned and occupied by the Sioux, who, in 1872, began fighting against the U.S. Army. Investors pulled out of Jay Cooke’s scheme, and Henry Cooke’s savings bank collapsed. Jay Cooke & Company closed and declared bankruptcy, a bankruptcy that led to a nationwide depression.50 More than one hundred banks and nearly twenty thousand businesses failed. Even after the worst of the depression was over, the price of grain kept on falling. A farmer’s profit on a bushel of corn had been forty-five cents in 1870; by 1889, the profit on that same bushel had fallen to ten cents.51

The populist revolt began when farmers started banding together and calling for cooperative farming and regulation of banks and railroads and an end to corporate monopolies. Nearly a million small farmers in the South and the Midwest flocked to an organization called the Grange. On July 4, 1873, they issued a Farmers’ Declaration of Independence, calling for an end to “the tyranny of monopoly,” which they described as “the absolute despotism of combinations that, under the fostering care of government and with wealth wrung from the people, have grown to such gigantic proportions as to overshadow all the land and wield an almost irresistible influence for their own selfish purposes in all its halls of legislation.”52

Finance capitalism had brought tremendous gains to investors and created vast fortunes, inaugurating the era known as the Gilded Age, edged with gold. It spurred economic development and especially the growth of big businesses: big railroad companies, big agriculture companies, and, beginning in the 1870s, big steel companies. (Andrew Carnegie built his first steel mill in 1875.) But to poor farmers like Mary Lease and to the farmers who joined the Grange, finance capitalism looked like nothing so much, as Lease put it, as “a fraud against the people.”53

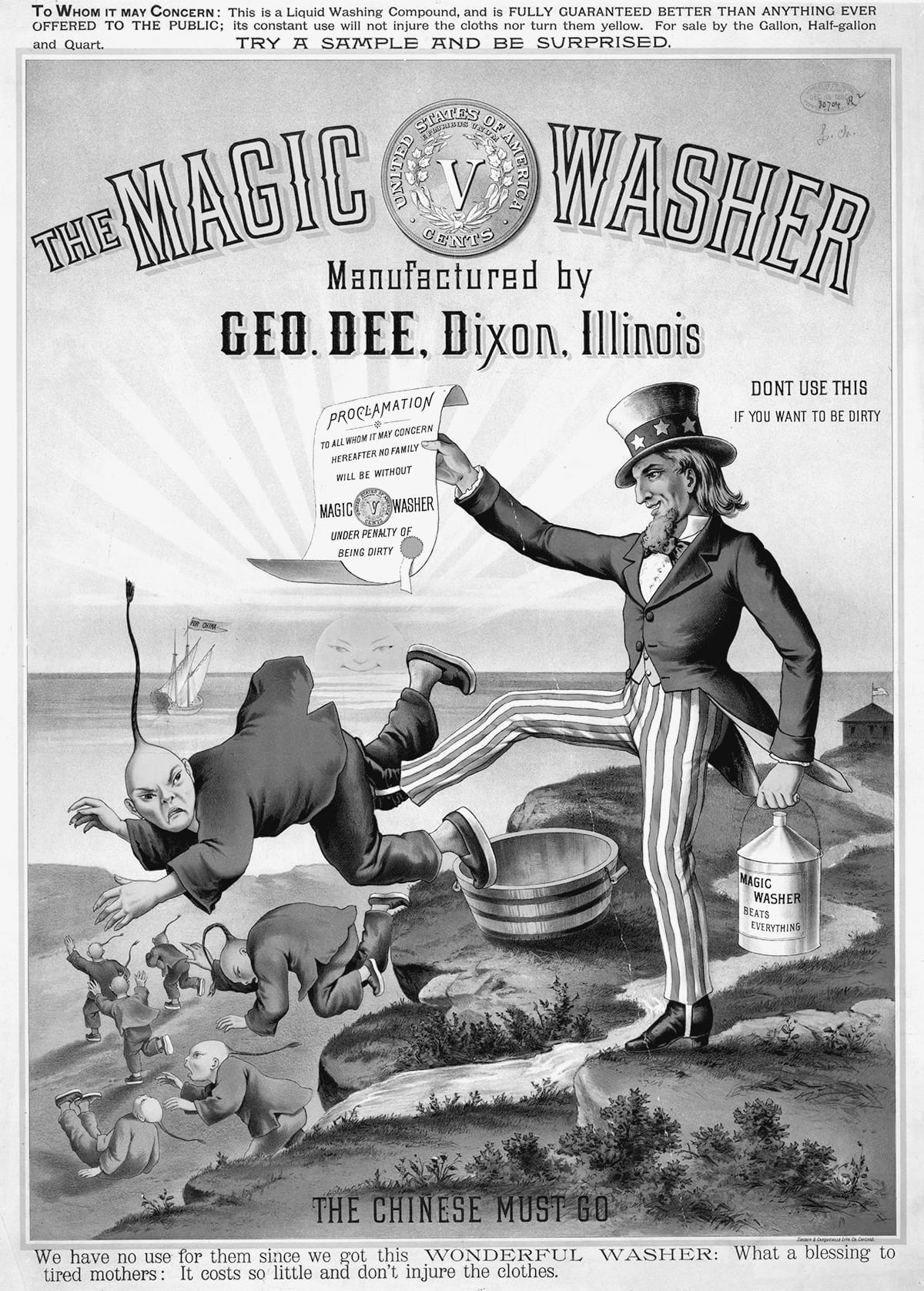

It looked that way to wage laborers, too. The Knights of Labor, founded in 1869 and with seven hundred thousand members by the 1880s, crusaded against the kings of industry. “One hundred years ago we had one king of limited powers,” the head of the Knights of Labor said. “Now we have a hundred kings, uncrowned ones, it is true, but monarchs of unlimited power, for they rule through the wealth they possess.”54 The laborers who raised their fists against the new uncrowned kings also hoped to crush beneath their feet the new peasants. No group of native-born Americans was more determined to end Chinese immigration than factory workers. The 1876 platform of the Workingmen’s Party of California declared that “to an American death is preferable to life on par with a Chinaman.”55 In 1882, spurred by the nativism of populists, Congress passed its first-ever immigration law, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred immigrants from China from entering the United States and, determining that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to people of Chinese ancestry, decreed that Chinese people already in the United States were permanent aliens who could never become citizens.

The National Farmers’ Alliance, formed in Texas in 1877 to fight for taxing of railroads and corporations and for the establishment of farm cooperatives and the removal of fences from public lands, soon spread into the Dakotas, Nebraska, Minnesota, Iowa, and Kansas.56 Populists, whether farmers or factory workers, for all their invocation of “the people,” tended to take a narrow view of citizenship. United in their opposition to the “money power,” members of the alliance, like members of the Knights of Labor, were also nearly united in their opposition to the political claims of Chinese immigrants, and of black people. The Farmers’ Alliance excluded African Americans, who formed their own association, the Colored Farmers’ Alliance. Nor did populists count Native Americans within the body of “the people.”

The long anguish of dispossession and slaughter that had begun in Haiti in 1492 opened a new chapter in the 1880s, on the eve of the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage. Since the era of Andrew Jackson and the forced removal of the Cherokees from their homelands, the federal government’s Indian policy rested on treaties that confined native peoples to reservations—“domestic dependent nations.” This policy had led to decades of suffering, massacre, and war, as many people, especially on the Plains, where the Cheyenne and Sioux stood their ground, had resisted forced confinement. Plains warfare ended in 1886, when Geronimo, of the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua Apaches, became one of the last native leaders to surrender to the U.S. Army.57 And still the conquest continued.

In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act, under whose terms the U.S. government offered native peoples a path to citizenship in a nation whose reach had extended across the lands of their ancestors. The Dawes Act granted to the federal government the authority to divide Indian lands into allotments and guaranteed U.S. citizenship to Indians who agreed to live on those allotments and renounce tribal membership. In proposing the allotment plan, Massachusetts senator Henry Laurens Dawes argued that the time had come for Indians to choose between “extermination or civilization” and insisted that the law offered Americans the opportunity to “wipe out the disgrace of our past treatment” and instead lift Indians up “into citizenship and manhood.”58

But in truth the Dawes Act understood native peoples neither as citizens nor as “persons of color,” and led to nothing so much as forced assimilation and the continued takeover of native lands. In 1887 Indians held 138 million acres; by 1900, they held only half of that territory. From the great debate at Valladolid in 1550 between Las Casas and Sepúlveda, debate about the morality of conquest had continued all but unabated across hundreds of years, during which each generation of Europeans and Americans who had confronted what by the middle of the nineteenth century they called the “Indian problem” had fallen short of their own understanding of justice.

POPULISTS’ GRIEVANCES WERE many, and bitter. Their best-founded objection was their concern about the federal government’s support of the interests of businesses over those of labor. This applied, in particular, to the railroads. In 1877, railroad workers protesting wage cuts went on strike in cities across the country. President Hayes sent in federal troops to end the strikes, marking the first use of the power of the federal government to support business against labor. The strikes continued, with little success in improving working conditions. Between 1881 and 1894, there was, on average, one major railroad strike a week. Labor was, generally and literally, crushed: in a single year, of some 700,000 men working on the railroads, more than 20,000 were injured on the job and nearly 2,000 killed.59

The lasting legacy of this battle came in the courts. When state legislatures tried to tax the railroads, as California did, federal judges eagerly entertained arguments that such taxes were unconstitutional—even going so far as accepting the argument that such laws violated the rights of corporations as “persons.” In 1882, Roscoe Conkling represented the Southern Pacific Railroad Company’s challenge to a California tax rule. He told the U.S. Supreme Court, “I come now to say that the Southern Pacific Railroad Company and its creditors and stockholders are among the ‘persons’ protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.”60

Conkling, aside from having been a senator and a presidential candidate, had twice been nominated to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court (he’d declined, unwilling to bear the loss of his income as a corporate attorney). In offering an argument about the meaning and original intention of the word “person” in the Fourteenth Amendment, Conkling enjoyed a singular authority: he’d served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction that had drafted the amendment and by 1882 was the lone member of that committee still living. With no one alive to contradict him, Conkling assured the court that the committee had specifically rejected the word “citizen” in favor of “person” in order to include corporations. (A legal fiction that corporations are “artificial persons” dates to the eighteenth century.) It’s true that “the rights and wrongs of the freedmen were the chief spur and incentive” of the amendment, Conkling allowed, but corporations had been on the minds of its drafters, too. A New York newspaper, reporting that day’s oral arguments, headlined its story “Civil Rights of Corporations.”61

Much evidence suggests, however, that Conkling was lying. The record of the deliberations of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction does not support his argument regarding the committee’s original intentions, nor is it plausible that between 1866 and 1882, the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment had kept mysteriously hidden their secret intention to guarantee equal protection and due process to corporations. But in 1886, when another railroad case, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, reached the Supreme Court, the court’s official recorder implied that the court had accepted the doctrine that “corporations are persons within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.”62 After that, the Fourteenth Amendment, written and ratified to guarantee freed slaves equal protection and due process of law, became the chief means by which corporations freed themselves from government regulation. In 1937, Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black would observe, with grim dismay, that, over the course of fifty years, “only one half of one percent of the Fourteenth Amendment cases that came before the court had anything to do with African Americans or former slaves, while over half of the cases were about protecting the rights of corporations.”63 Rights guaranteed to the people were proffered, instead, to corporations.

III.

“MAN IS MAN,” Mary E. Lease liked to say, but “woman is superman.” Populism gave vent to the grievances of farmers and laborers against business and government. But the movement was built by women—women who believed they were morally superior to men.64

Lease entered politics by way of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), a federation of women’s clubs formed in Cleveland in 1874 and itself an outgrowth of a campaign against saloons known as the Woman’s Crusade. She first spoke in public at a WCTU rally in Kansas, delivering a hair-raiser called “A Plea for the Temperance Ballot for Women.”65 Lease argued that, to end the scourge of alcohol—which, for women, served as shorthand for husbands who beat their wives and children and who spent their wages on drinking, leaving their families to starve—women needed the right to vote.

This argument reshaped the nation’s political parties. In 1872, the Prohibition Party became the first party to declare itself in favor of women’s suffrage. Seven years later, the WCTU, under the leadership of Frances Willard, adopted “Home Protection” as its motto. The indefatigable Willard, who’d been president of a women’s college and the first female dean of Northwestern University, lived by another motto: “Do Everything.” When the Republican Party failed to support either Prohibition or suffrage, Willard defected from the GOP and founded the Home Protection Party, which in 1882 merged with the Prohibition Party. “Then and there,” Willard wrote, American women entered politics, “and when they came they came to stay.”66

Like Lease, Sarah E. V. Emery, a devout Universalist from Michigan, rose to prominence as a speaker and writer through the WCTU, the Knights of Labor, and the Farmers’ Alliance. The Farmers’ Alliance sold over 400,000 copies of Emery’s anti-Semitic tract Seven Financial Conspiracies Which Have Enslaved the American People. “It is within the memory of many of my readers when millionaires were not indigenous to American soil,” Emery wrote. “But that period has passed, and today we boast more millionaires than any other country on the globe; tramps have increased in a geometrical ratio; while strikes, riots and anarchists’ trials constitute an exciting topic of conversation in all classes of society.” Emery blamed this state of affairs on a conspiracy of Jewish bankers.67

To advance their causes, both populists and suffragists, rejected by the major parties, turned to third-party politics. If the Republican Party had turned its back on equal rights for women, the Democratic Party had still less interest in the cause. Susan B. Anthony hoped to deliver a speech at the 1880 Democratic National Convention, calling on the party “to secure to twenty millions of women the rights of citizenship.” Instead, Anthony was left to look on, in silence, while her statement was read by a male clerk, after which, the New York Times reported, “No action whatever was taken in regard to it, and Miss Anthony vexed the convention no more.”68 Marietta Stow, a newspaper publisher, declared that it was “quite time that we had our own party” and ran for governor of California in 1882 as a candidate of the Woman’s Independent Political Party. Two years later, Belva Lockwood, a DC attorney, campaigned as the presidential candidate of the Equal Rights Party. In 1886, Emery spoke on behalf of suffrage planks at both the Democratic Party and Prohibition Party conventions. But Judith Ellen Foster, who’d helped found the WCTU, condemned third parties at a Republican rally. Far from honoring woman, a third party only “appropriates her work and her influence to its own purposes,” Foster warned. In 1892, Foster founded the Woman’s National Republican Association. “We are here to help you,” she told the party’s male delegates at its convention that year, and, she added, echoing Willard, “we have come to stay.”69

By then, Lease had helped found not a women’s club or a women’s party but a People’s Party, which joined with a movement led by a California newspaperman named Henry George. A character straight out of a Melville novel, George, born in Philadelphia in 1839, had left school at fourteen and sailed to India and Australia as a foremast boy, on board a ship called the Hindoo. Romantics wrote about India as a place of jewels and jasmine; George was struck, instead, by its poverty. Returning to Philadelphia, he became a printer’s apprentice, a position that many radicals before him had taken into politics. (Benjamin Franklin had been a printer’s apprentice. So had William Lloyd Garrison.) Enticed by the West, he joined the crew of a navy lighthouse ship sailing around Cape Horn in 1858 because it was the only way he could afford to get to California. In San Francisco, he edited a newspaper; it soon failed. By 1865, married and with four children, he was begging in the streets to feed his family.70

He finally found work, first as a printer and then as a writer and editor, with the San Francisco Times. From the West, when the railroad had nearly crossed the continent, George wrote an essay called “What the Railroad Will Bring Us.” His answer: the rich will get richer and the poor will get poorer. In a Fourth of July oration in 1877, he declared, “No nation can be freer than its most oppressed, richer than its poorest, wiser than its most ignorant.”71

In Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Causes of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth, published in 1879, George argued that the very same technological progress that brought so many marvels brought wealth to the few and poverty to the many. “Discovery upon discovery, and invention after invention, have neither lessened the toil of those who most need respite, nor brought plenty to the poor,” he wrote. He devised an economic plan that involved abolishing taxes on labor and instead imposing a single tax on land. Tocqueville had argued that democracy in America is made possible by economic equality; people with equal estates will eventually fight for, and win, equal political rights. George agreed. But, like Mary Lease, he thought that financial capitalism was destroying democracy by making economic equality impossible. He saw himself as defending “the Republicanism of Jefferson and the Democracy of Jackson.”72

George believed that the problem of inequality could not be solved without reforming elections. Suffragists suggested that the solution to corrupt elections was for women to vote, and some suggested it would be better to retract the franchise from poor white men (and give it to wealthier white women instead). But George, while granting that elections had become a national scandal, resisted the conclusion “that democracy is therefore condemned or that universal suffrage must be abandoned.”73 He didn’t want poor white men to lose the right to vote, and he supported women’s suffrage (though he vehemently opposed extending either suffrage or any other right of citizenship to Chinese immigrants or their children). He wanted white men to vote better.

In the age of popular politics, Election Day was a day of drinking and brawls. Party thugs stationed themselves at the polls and bought votes by doling out cash, called “soap,” and handing voters pre-printed party tickets. Buying votes cost anything from $2.50, in San Francisco, to $20, in Connecticut. In Indiana, men sold their suffrages for no more than the cost of a sandwich.74 Prohibitionists argued that the best way to battle corruption was to get alcohol out of elections. George argued for getting money out. In 1871, after the New York Times began publishing the results of an investigation into the gross corruption of elections in New York City under Democratic Party boss William Magear Tweed, George, who had spent considerable time in Australia and had married an Australian woman, proposed a reform that had been introduced in Australia in 1856. Under the terms of Australia’s ballot law, no campaigning could take place within a certain distance of the polls, and election officials were required to print ballots and either to build booths or hire rooms, to be divided into compartments, where voters could mark their ballots in secret. Without such reforms, George wrote, “we might almost think soberly of the propriety of putting up our offices at auction.”75

To promote the Australian ballot, George created a new party, the Union Labor Party. Mary Lease joined the party in Kansas. In 1886, George, having moved east, ran for mayor of New York on the Union Labor ticket. The Democratic candidate, Abram Hewitt, won, but George beat the Republican, twenty-eight-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, a young man who only six years before had written a senior thesis at Harvard titled “The Practicability of Equalizing Men and Women Before the Law.” Three years later, Henry George and Mary Lease helped to form the People’s Party. “We are depending upon the votes of freemen for our success—votes of men who will not be bought or sold,” Lease said at the party’s Kansas convention in 1890. “Let our motto be more money and less misery.”76

As the suffering of farmers and wage workers grew, so did the ranks of the People’s Party, which became the most successful third party in American history. Between 1889 and 1893, the mortgages on so many farms were foreclosed that 90 percent of farmland fell into the hands of bankers. The richest 1 percent of Americans owned 51 percent of the nation’s wealth, and the poorest 44 percent owned less than 2 percent. Populists didn’t oppose capitalism; they opposed monopolism, which Lease called “the divine right of capital,” predicting that it would go the way of “the divine right of kings.” If they weren’t quite socialists, they were certainly collectivists. “Henry George is not the representative of any political party, clan or ‘ism,’” Lease said. “In the great struggle now going on between the millions who have not enough to eat and the plutocratic few who have a million times more than their craven bodies deserve; in the great struggle between human greed and human freedom, Henry George stands as a fearless exponent and defender of human rights.”77

For all its passionate embrace of political equality and human rights and its energetic championing of suffrage, the People’s Party rested on a deep and abiding commitment to exclude from full citizenship anyone from or descended from anyone from Africa or Asia. (Emery’s anti-Semitism pervaded the movement as well, but it did not attach itself to arguments about citizenship.) Populism’s racism and nativism rank among its longest-lasting legacies. Lease, in a wildly incoherent white supremacist screed called The Problem of Civilization Solved, wove together the population theories of Thomas Malthus and Thomas Jefferson with the colonization schemes endorsed by James Madison and the outright racism of the social Darwinist Herbert Spencer to propose that all manual labor be done by Africans and Asians. “Through all the vicissitudes of time, the Caucasian has arisen to the moral and intellectual supremacy of the world,” she wrote, and the time had come for white people to realize their “destiny to become the guardians of the inferior races.”78

Many of the reforms proposed by populists had the effect of diminishing the political power of blacks and immigrants. Chief among them was the Australian ballot, more usually known as the secret ballot, which, by serving as a de facto literacy test, disenfranchised both black men in the rural South and new immigrants in northern cities. In 1888, the Kentucky state legislature became the first in the nation to attempt the reform, in the city of Louisville. “The election last Tuesday was the first municipal election I have ever known which was not bought outright,” one observer wrote to the Nation after Election Day.79 Massachusetts passed a secret ballot law later that year. The measure seemed likely to suppress the Democratic vote, since literacy was lowest among the newest immigrants to northern cities, who tended to vote Democratic. In New York, the Democratic governor, David Hill, vetoed a secret ballot bill three times.80 Hill’s veto was only broken in 1890, after fourteen men carried a petition weighing half a ton to the floor of the New York legislature.81

Massachusetts and New York proved the only states to deliberate at length over the secret ballot. Quickest to adopt the reform were the states of the former Confederacy, where the reform appealed to legislatures eager to find legal ways to keep black men from voting. In 1890, Mississippi held a constitutional convention and adopted a new state constitution that included an “Understanding Clause”: voters were required to pass oral examination on the Constitution, on the grounds that “very few Negroes understood the clauses of the Constitution.” (Nor, of course, did most whites, though white men were not tested.) In the South, the secret ballot was adopted in this same spirit. Both by law and by brute force, southern legislators, state by state, and poll workers, precinct by precinct, denied black men the right to vote. In Louisiana, black voter registration dropped from 130,000 in 1898 to 5,300 in 1908, and to 730 in 1910. In 1893, Arkansas Democrats celebrated their electoral advantage by singing,

The Australian ballot works like a charm

It makes them think and scratch

And when a Negro gets a ballot

He has certainly met his match.82

Populists’ other signal reform was the graduated income tax, a measure they believed essential to the survival of a democracy undermined by economic inequality. After the Civil War, a wartime federal income tax had been allowed to expire, over the protests of John Sherman, a Republican from Ohio who would go on to author the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) and who, countering Jefferson, pointed out that tariffs unfairly burdened the poor. “We tax the tea, the coffee, the sugar, the spices the poor man uses,” Sherman said. “Everything that he consumes we call a luxury and tax it; yet we are afraid to touch the income of Mr. Astor. Is there any justice in that? Is there any propriety in it? Why, sir, the income tax is the only one that tends to equalize these burdens between rich and poor.”83

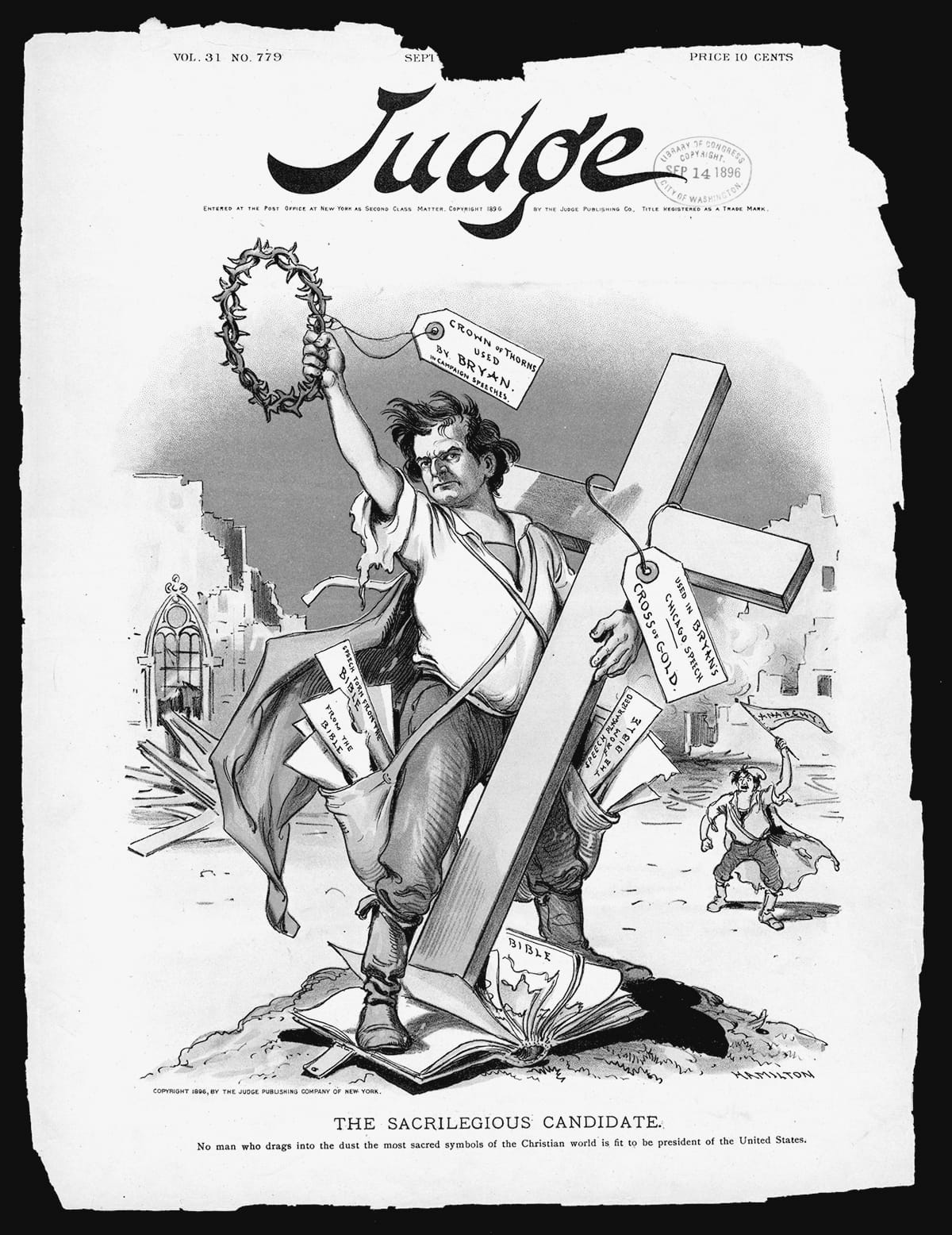

But the man who drove this point home was the inimitable William Jennings Bryan. Tall, broad-shouldered, and sturdy in a string tie and cowhide boots, Bryan carried populism from the Plains to the Potomac and turned the Democratic Party into the people’s party. Born in Illinois in 1860, he’d snuck into the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis in 1876 when an obliging policeman had helped him in through a window. He’d gone to Illinois College and then to Union College of Law in Chicago. He made a particular study of oratory, at which he trained for years. Still, when he asked his mother’s opinion of his first political speech in 1880, she said, “Well, there were a few good places in it—where you might have stopped!” Moving to Nebraska, he’d settled in Lincoln, a prairie town, in the Union’s fastest-growing state. He was elected to Congress as a Democrat in 1890, when he was thirty. “Boy Bryan,” he was called. He began his first run for the presidency when he was two months shy of the required age. He would live his life on the political stage and die, far diminished, in the glow cast by the footlights.84

Nearly everyone who ever heard Boy Bryan said he was the best speaker they’d ever known. In an age before amplification, Bryan may have been the only speaker most people had ever really heard: he could project his voice for three blocks, and at events where speaker after speaker took to the stage, very often only Bryan’s rose above the distant mumble of lesser men. He was also mesmerizing. The first presidential candidate to campaign on behalf of the poor, Bryan delivered the leveling promise of the Second Great Awakening to American party politics and, in the end, to the Democratic Party. One Republican said, “I felt that Bryan was the first politician I had ever heard speak the truth and nothing but the truth,” even though in every case, when he read a transcript of the speech in the newspaper the next day, he “disagreed with almost all of it.”85