Ten

EFFICIENCY AND THE MASSES

WALTER LIPPMANN WORE A THREE-PIECE PINSTRIPE suit the way a tiger wears his skin, but the clue to his acuity came in the raised eyebrows, as pointed as the tip of an arrow. Educated at Harvard, where he studied with William James and George Santayana, he’d seemed destined for a distinguished if quiet career as a professor of philosophy, or maybe history, when he decided, instead, to become a reporter, the sort of man who tucked his pencil into his hat band, except that he wasn’t exactly that kind of reporter: he invented another kind, the learned political commentator. “To read, if not to comprehend, Lippmann was suddenly the thing to do,” wrote one much-wounded rival.

By 1914, when Lippmann was twenty-five, he’d already written two piercing books about American politics and helped launch the New Republic. He was heavyset and silent; his friends called him Buddha. He lived with a who’s who of other young liberals in a narrow three-story red brick row house on Nineteenth Street in Washington that visitors, including Herbert Hoover, who once ate an unlit cigar there over dinner, named the House of Truth. Theodore Roosevelt called Lippmann the “most brilliant young man of his age in all the United States,” which was but small comfort to older men, who found their ideas unraveled by Lippmann, like yarn in the clutches of a kitten. How did a man so young write with such authority, matched by so wide an appeal? Oliver Wendell Holmes said Lippmann’s pieces were like flypaper: “If I touch it, I am stuck till I finish it.”1

In the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth, when Lippmann came of age, industrialism brought great, glittering wealth to a few, prosperity to the nation, cheaper goods to the middle class, and misery and want to the many. The many now numbering more than ever before, talk of “the people” yielded to talk of “the masses,” the swelling ranks of the poor, haggard and hungry. Like many Americans of his generation, Lippmann started out as a socialist, when even mentioning the masses hinted at socialism; The Masses was the name of a socialist monthly, published in New York, and, especially after the Russian Revolution of 1917, which brought the Bolshevists to power (“bol’shinstvo” means “the majority”), “the masses” sounded decidedly Red. But Lippmann soon began to write about the masses as “the bewildered herd,” unthinking and instinctual, and as dangerous as an impending stampede. For Lippmann, and for an entire generation of intellectuals, politicians, journalists, and bureaucrats who styled themselves Progressives—the term dates to 1910—the masses posed a threat to American democracy. After the First World War, Progressives refashioned their aims and took to calling themselves “liberals.”2

Only someone with so great a faith in the masses as Lippmann had when he started out could have ended up with so little. This change was wrought in the upheaval of the age. In the years following the realigning election of 1896, everything seemed, suddenly, bigger than before, more crowded, and more anonymous: looming and teeming. Even buildings were bigger: big office buildings, big factories, big mansions, big museums. Quantification became the only measure of value: how big, how much, how many. There were big businesses: big banks, big railroads, Big Oil. U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation, was formed in 1901 by consolidating more than two hundred companies in the iron and steel businesses. To fight monopolies, protect the people, and conserve the land, the federal government grew bigger, too; dozens of new federal agencies were founded in this era, from the National Bureau of Standards (1901) to the Forest Service (1905), the Coast Guard (1915), and the Bureau of Efficiency (1916), the last designed to handle the problem of bigness by the twin arts of organization and acceleration, a bureau of bureaus.

“Mass” came to mean anything that involved a giant and possibly terrifying quantity, on a scale so great that it overwhelmed existing arrangements—including democracy. “Mass production” was coined in the 1890s, when factories got bigger and faster, when the number of people who worked in them skyrocketed, and when the men who owned them got staggeringly rich. “Mass migration” dates to 1901, when nearly a million immigrants were entering the United States every year, “mass consumption” to 1905, “mass consciousness” to 1912. “Mass hysteria” had been defined by 1925 and “mass communication” by 1927, when the New York Times described the radio as “a system of mass communication with a mass audience.”3

And the masses themselves? They formed a mass audience for mass communication and had a tendency, psychologists believed, to mass hysteria—the political stampede—posing a political problem unanticipated by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who believed that the size of the continent and the growth of its population would make the Republic stronger and its citizens more virtuous. They could not have imagined the vast economic inequality of the Gilded Age, its scale, its extravagance, and its agonies, and the challenge posed to the political order by millions of desperately poor men, women, and children, their opinions easily molded by the tools of mass persuasion.

To meet that challenge in what came to be called the Progressive Era, activists, intellectuals, and politicians campaigned for and secured far-reaching reforms that included municipal, state, and federal legislation. Their most powerful weapon was the journalistic exposé. Their biggest obstacle was the courts, which they attempted to hurdle by way of constitutional amendments. Out of these campaigns came the federal income tax, the Federal Reserve Bank, the direct election of U.S. senators, presidential primaries, minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws, women’s suffrage, and Prohibition. Nearly all of these reforms had long been advocated for, in many cases first by William Jennings Bryan. Progressives’ biggest failure was also Bryan’s: their unwillingness to address, or even discuss, Jim Crow. Instead, they propped it up. And all of what Progressives accomplished in the management of mass democracy was vulnerable to the force that so worried the unrelenting Walter Lippmann: the malleability of public opinion, into mass delusion.

I.

PROGRESSIVISM HAD ROOTS in late nineteenth-century populism; Progressivism was the middle-class version: indoors, quiet, passionless. Populists raised hell; Progressives read pamphlets. Populists had argued that the federal government’s complicity in the consolidation of power in the hands of big banks, big railroads, and big businesses had betrayed both the nation’s founding principles and the will of the people, and that the government itself was riddled with corruption. “The People’s Party is the protest of the plundered against the plunderers—of the victim against the robbers,” said one organizer at the founding of the People’s Party in 1892.4 “A vast conspiracy against mankind has been organized on two continents and is rapidly taking possession of the world,” said another.5 Progressives championed the same causes as Populists, and took their side in railing against big business, but while Populists generally wanted less government, Progressives wanted more, seeking solutions in reform legislation and in the establishment of bureaucracies, especially government agencies.6

Populists believed that the system was broken; Progressives believed that the government could fix it. Conservatives, who happened to dominate the Supreme Court, didn’t believe that there was anything to fix but believed that, if there was, the market would fix it. Notwithstanding conservatives’ influence in the judiciary, Progressivism spanned both parties. After 1896, when the Democratic Party convinced Bryan to run as a Democrat instead of as a Populist, Democrats boasted that they had successfully folded Populists into their party. In 1905, Governor Jeff Davis of Arkansas said, “In 1896, when we nominated the grandest and truest man the world ever knew—William Jennings Bryan—for President, we stole all the Populists hate; we stole their platform, we stole their candidate, we stole them out lock, stock, and barrel.” But Republicans were Progressives, too. “The citizens of the United States must effectively control the mighty commercial forces which they have themselves called into being,” Theodore Roosevelt said. And, as Woodrow Wilson himself admitted, “When I sit down and compare my views with those of a Progressive Republican I can’t see what the difference is.”7

Much that was vital in Progressivism grew out of Protestantism, and especially out of a movement known as the Social Gospel, adopted by almost all theological liberals and by a large number of theological conservatives, too. The name dates to 1886, when a Congregationalist minister took to calling Henry George’s Progress and Poverty a social gospel. George had written much of the book with evangelical zeal, arguing that only a remedy for economic inequality could bring about “the culmination of Christianity—the City of God on earth, with its walls of jasper and its gates of pearl!” (More skeptical and less religious liberals had long since lost faith with George’s utopianism, Clarence Darrow shrewdly remarking, “The error I found in the philosophy of Henry George was its cocksureness, its simplicity, and the small value that it placed upon the selfish motives of men.”)8

The Social Gospel movement was led by seminary professors—academic theologians who accepted the theory of evolution, seeing it as entirely consistent with the Bible and evidence of a divinely directed, purposeful universe; at the same time, they fiercely rejected the social Darwinism of writers like Herbert Spencer, the English natural scientist who coined the phrase “the survival of the fittest” and used the theory of evolution to defend all manner of force, violence, and oppression. After witnessing a coal miners’ strike in Ohio in 1882, the Congregationalist Washington Gladden, a man never seen without his knee-length, double-breasted Prince Albert frock coat, argued that fighting inequality produced by industrialism was an obligation of Christians: “We must make men believe that Christianity has a right to rule this kingdom of industry, as well as all the other kingdoms of this world.”9

Social Gospelers brought the zeal of abolitionism to the problem of industrialism. In 1895, Oberlin College held a conference called “The Causes and Proposed Remedies of Poverty.” In 1897, Topeka minister Charles Sheldon, who got to know his parish by living among his poorest parishioners—spending three weeks in a black ghetto—sold millions of copies of a novel, In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do?, about a minister and his congregation who wonder how Christ would address industrialism (their answer: with Progressive reform). In 1908, Methodists wrote a Social Creed and pledged to fight to end child labor and to promote a living wage. It was soon adopted by the thirty-three-member Federal Council of Churches, which proceeded to investigate a steelworkers’ strike in Bethlehem, ultimately taking the side of the strikers.10

William Jennings Bryan, hero of the plains, was a Social Gospeler in everything but name.11 After losing the election in 1896, though, he threw off his cross of gold and dedicated himself to a new cause: the protest of American imperialism. Bryan saw imperialism as inconsistent with both Christianity and American democratic traditions. Other Progressives disagreed—Protestant missionaries in particular—seeing both Cuba and the Philippines as opportunities to gain new converts.

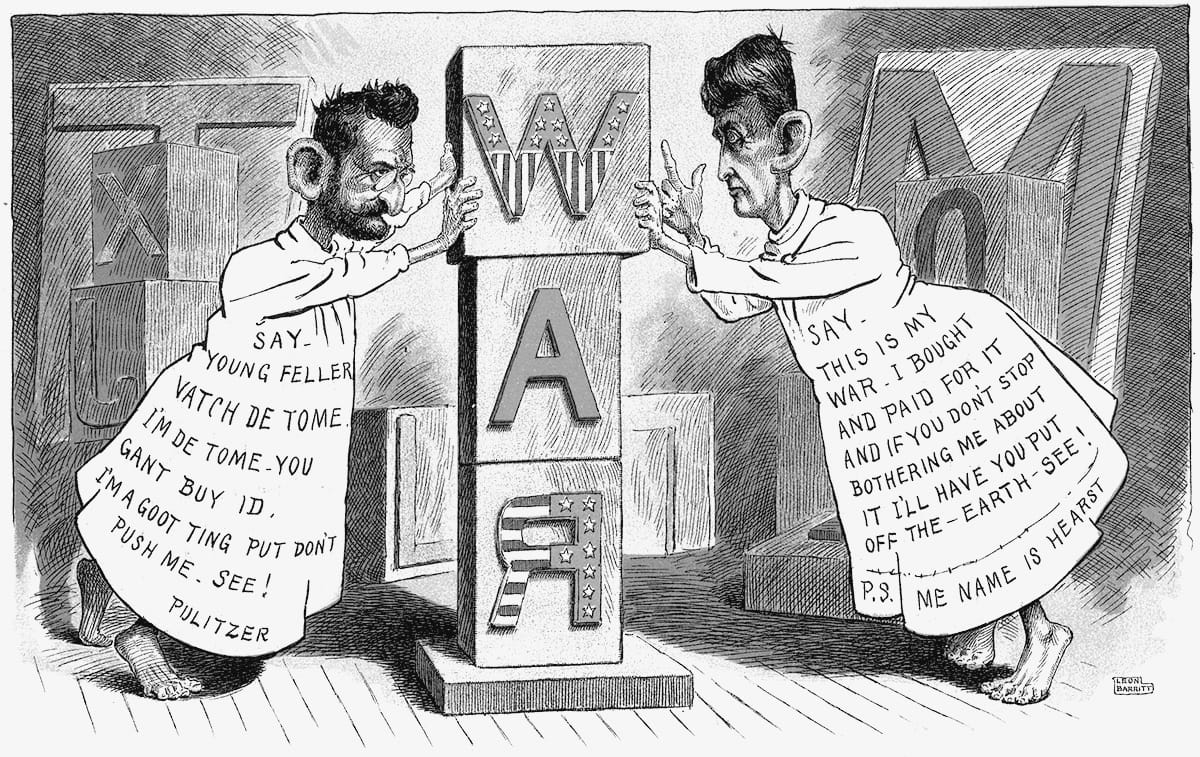

The Spanish-American War, what boosters called a “splendid little war,” began in 1898. Cubans had been attempting to throw off Spanish rule since 1868, and Filipinos had been doing the same since 1896. Newspaper barons William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer came to side with the Cuban rebels, and, eyeing a rich opportunity to boost their newspapers’ circulation, they sent reporters and photographers not only to chronicle the conflict but, in Hearst’s case, to stir it up. Newspaper lore has it that when one of Hearst’s photographers cabled from Havana that war seemed unlikely, Hearst cabled back: “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.” President McKinley sent a warship to Cuba as a precaution, but in February 1898 that ship, the USS Maine, blew up in Havana, killing 250 U.S. sailors. The cause of the explosion was unknown—and it would later be revealed to have been an accident—but both Hearst and Pulitzer published a cable from the captain of the battleship to the assistant secretary of the navy, Theodore Roosevelt, informing him that the disaster was no accident. (The cable was later revealed to be a fake.) Newspaper circulation soared; readers clamored for war. When Congress obliged by declaring war on Spain, Hearst fired rockets from the roof of the New York Journal’s building. Pulitzer came to regret his part in the rush to war, but not Hearst. On his lead newspaper’s front page, Hearst ran the headline HOW DO YOU LIKE THE JOURNAL’S WAR?12

Thirty-nine-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, determined to see combat, resigned his position as assistant secretary of the navy, formed the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, charged up San Juan Hill, and came back a hero. Even Bryan, thirty-eight, enlisted. He formed a volunteer regiment from Nebraska, and went to Florida to prepare to fight, but was never sent into combat, McKinley having apparently made sure Bryan, his presidential rival, had no chance for glory.

Under the terms of the peace, Cuba became independent, but Spain ceded Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States, in exchange for $20 million. A U.S. occupation and American colonial rule were not what the people of the Philippines had in mind when they threw off Spanish rule. The Philippines declared its independence, and Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo formed a provisional constitutional government. McKinley refused to recognize it, and by 1899 U.S. troops had fired on Filipino nationalists. “I know that war has always produced great losses,” Aguinaldo said in an address to the Filipino people. “But I also know by experience how bitter is slavery.” Bryan resigned his commission to protest the annexation, joining a quickly formed and badly organized Anti-Imperialist League, whose supporters included Jane Addams, Andrew Carnegie, William James, and Mark Twain. Bryan, their best speaker, argued that the annexation of the Philippines betrayed the will of both the Filipino people and the American people. “The people have not voted for imperialism,” he said, “no national convention has declared for it; no Congress has passed upon it.”13

From its start in 1899, the Philippine-American War was an unusually brutal war, with atrocities on both sides, including the slaughter of Filipino civilians. U.S. forces deployed on Filipinos a method of torture known as “water cure,” forcing a prisoner to drink a vast quantity of water; most of the victims died. Meanwhile, in Washington, in the debate over the annexation of the Philippines, Americans revisited unsettled questions about expansion that had rent the nation during the War with Mexico and unsettled questions about citizenship that remained the unfinished business of Reconstruction. The debate also marked the limits of the Progressive vision: both sides in this debate availed themselves, at one time or another, of the rhetoric of white supremacy. Eight million people of color in the Pacific and the Caribbean, from the Philippines to Puerto Rico, were now part of the United States, a nation that already, in practice, denied the right to vote to millions of its own people because of the color of their skin.

On the floor of the Senate, those who favored imperial rule over the Pacific island argued that the Filipinos were, by dint of race, unable to govern themselves. “How could they be?” asked Indiana Republican Albert J. Beveridge. “They are not of a self-governing race. They are Orientals.” But senators who argued against annexation pointed out that when the Confederacy had made this argument about blacks, the Union had fought a war and staged an occupation over its disagreement with that claim. “You are undertaking to annex and make a component part of this Government islands inhabited by ten millions of the colored race, one-half or more of whom are barbarians of the lowest type,” said Ben Tillman, a one-eyed South Carolina Democrat who’d boasted of having killed black men and expressed his support for lynch mobs. “It is to the injection into the body politic of the United States of that vitiated blood, that debased and ignorant people, that we object.” Tillman reminded Republicans that they had not so long ago freed slaves and then “forced on the white men of the South, at the point of the bayonet, the rule and domination of those ex-slaves. Why the difference? Why the change? Do you acknowledge that you were wrong in 1868?”14

The relationship between Jim Crow and the war in the Philippines was not lost on black soldiers who served in the Pacific. An infantryman from Wisconsin reported that the war could have been avoided had white American soldiers not applied to the Filipinos “home treatment for colored peoples” and “cursed them as damned niggers.” Rienzi B. Lemus, of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry, reported on the contrast between what he read in American newspapers and what he saw in the Philippines. “Every time we get a paper from there,” he wrote home to Richmond, Virginia, “we read where some poor Negro is lynched for supposed rape,” while in the Philippines, only when “there was no Negro in the vicinity to charge with the crime,” were two white soldiers sentenced to be shot for raping a Filipino woman.15

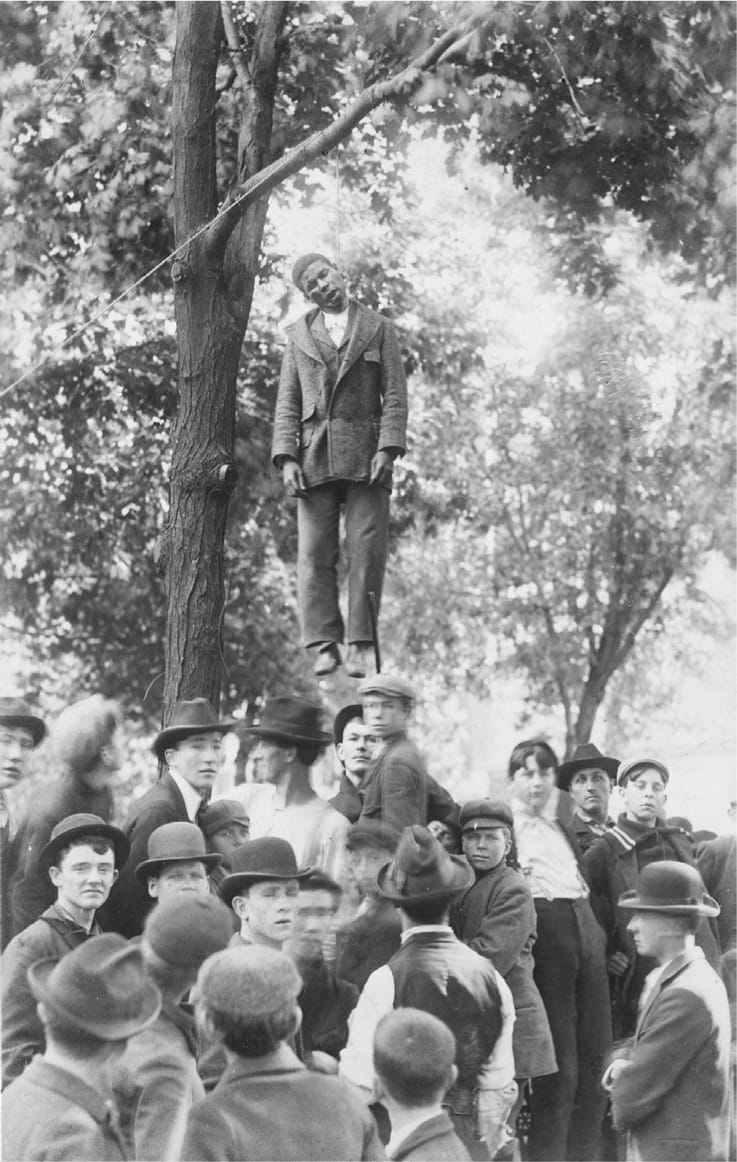

The war that began in Cuba in 1898 and was declared over in the Philippines in 1902 dramatically worsened conditions for people of color in the United States, who faced, at home, a campaign of terrorism. Pro-war rhetoric, filled with racist venom, only further incited American racial hatreds. “If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched,” the governor of Mississippi pledged in 1903. Mark Twain called lynching an “epidemic of bloody insanities.” By one estimate, someone in the South was hanged or burned alive every four days. The court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson meant that there was no legal recourse to fight segregation, which grew more brutal with each passing year. Nor was discrimination confined to the South. Cities and counties in the North and West passed racial zoning laws, banning blacks from the middle-class communities. In 1890, in Montana, blacks lived in all fifty-six counties in the state; by 1930, they’d been confined to just eleven. In Baltimore, blacks couldn’t buy houses on blocks where whites were a majority. In 1917, in Buchanan v. Warley, the Supreme Court availed itself of the Fourteenth Amendment not to guarantee equal protection for blacks but to guarantee what the court had come to understand as the “liberty of contract”—the liberty of businesses to discriminate.16

In the spring of 1899, while teaching at Atlanta University, W. E. B. Du Bois was walking from his rooms on campus to deliver to the offices of a city newspaper a restrained essay about the lynching of Sam Hose, a black farmer, when he saw, displayed in a store window, Hose’s knuckles. Hose had been dismembered, and barbecued, his body parts sold as souvenirs. Du Bois, who had earned a PhD in history at Harvard in 1895 before studying in Europe, had pioneered a new method of social science research that had become a hallmark of Progressive Era reform: the social survey. In 1896, he’d gone door-to-door in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward and personally interviewed more than five thousand people in order to prepare his study The Philadelphia Negro. In 1898, he’d delivered a meticulously argued academic lecture on “The Study of the Negro Problems,” which, while brilliant, was cluttered with blather like “the phenomena of society are worth the most careful and systematic study.” But on that spring day in 1899 when he saw what had once been Hose’s hands, he turned around, walked back to his rooms, threw away his essay, and decided that “one could not be a calm, cool and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered and starved.”17

A lot of other people decided that they, too, couldn’t keep calm—and, like Du Bois, that they could no longer live in places like Georgia. “We are outnumbered and without arms,” Ida B. Wells wrote. Instead, they packed up and left, in what came to be called the Great Migration, the movement of millions of blacks from the South to the North and West. Before the Great Migration began, 90 percent of all blacks in the United States lived in the South. Between 1915 and 1918, five hundred thousand African Americans left for cities like Milwaukee and Cleveland, Chicago and Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Detroit. Another 1.3 million left the South between 1920 and 1930. By the beginning of the Second World War, 47 percent of all blacks in the United States lived outside the South. In cities, they built new communities, and new community organizations. In 1909, in New York, Du Bois helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the next year began editing its monthly magazine, The Crisis, explaining that its title came from the conviction that “this is a critical time in the history of the advancement of men”—a crisis for humanity.18

White Progressives, who borrowed from the social science methods pioneered by Du Bois, turned a blind eye to Jim Crow. Like Populists before them, when Progressives talked about inequality, they meant the condition of white farmers and white wage workers relative to business owners. Yet Progressives were undeniably influenced by the struggle for racial justice, not least by the investigative journalism methods pioneered by Wells, with her exposé of lynching: the exposé became Progressives’ sharpest tool. After Theodore Roosevelt, alluding to Pilgrim’s Progress, damned “the Man with the Muck-rake,” who “consistently refuses to see aught that is lofty and fixes his eyes with solemn intentness only on that which is vile and debasing,” investigative journalism came to be called muckraking.19 It first became a national phenomenon at McClure’s, a monthly magazine, when in 1902 its publisher, an Irish immigrant named Samuel Sidney McClure, gave an investigative assignment—designed to expose corruption and lawlessness—to each of his three best writers, charging Ray Stannard Baker with writing about unions, Ida Tarbell about Standard Oil, and Lincoln Steffens about big-city politics. (Steffens later hired as his assistant a very young Walter Lippmann.) None of these people liked being described as a writer who sees only filth. Tarbell, who’d earlier written biographies of Napoleon and Lincoln, considered herself not a muckraker but a historian. And, as Baker later insisted, “We muck-raked not because we hated our world but because we loved it.”20

Tarbell’s indictment of Standard Oil, a catalogue of collusion and corruption, harassment, intimidation, and outright thuggery, first appeared as a nineteen-part series in McClure’s. Standard Oil, Tarbell wrote, was the first of the trusts, the model for all that followed, and “the most perfectly developed trust in existence.” Tarbell, who’d grown up next to an oil field—“great oil pits sunken in the earth”—had watched Standard Oil crush its competition. Often investigated by state and local governments, the company had left behind a paper trail, which Tarbell had followed, doggedly, in the archives. But it was her writing that brought her argument home. “There was nothing too good for them, nothing they did not hope and dare,” she wrote of a group of young men starting out on their own in the industry, unaware of Standard Oil’s methods. “At the very heyday of this confidence, a big hand reached out from nobody knew where, to steal their conquest and throttle their future.”21

In the wake of Tarbell’s indictment, Rockefeller, who’d founded Standard Oil in 1870, became one of the most despised men in America, a symbol of everything that had gone wrong with industrialism. That Rockefeller was a Baptist and a philanthropist did not stop William Jennings Bryan from arguing that no institution should accept a penny from him (Bryan refused to serve on the board of his alma mater, Illinois College, until it broke ties with Rockefeller). “It is not necessary,” Bryan said, “that all Christian people shall sanction the Rockefeller method of making money merely because Rockefeller prays.”22

Muckraking fueled the engine of Progressivism. But the car was driven by two American presidents, Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt, men who could hardly have been more different but who, between them, vastly extended the powers of the presidency while battling against combinations of capital that made corporations into monopolies.

WHEN WOODROW WILSON was a boy reading Sir Walter Scott, he made a paper navy, appointed himself its admiral, and wrote his fleet a constitution. His graduating class at Princeton named him the class’s “model statesman.” At the University of Virginia, he studied law and joined the debating society. A generation earlier, he’d have become a preacher, like his father, but instead he became a professor of political science.23 In the academy and later in the White House, he dedicated himself to the problem of adapting a Constitution written in the age of the cotton gin to the age of the automobile.

A modernist, impatient with his ancestors, Wilson believed that the separation of powers had gotten thrown out of whack. In Congressional Government, he argued that Congress had too much power and used it unwisely, passing laws pell-mell and hardly ever repealing any. He applied the theory of evolution to the Constitution, which, he said, “is not a machine, but a living thing,” and “falls, not under the theory of the universe, but under the theory of organic life.” He came to believe that the presidency had been evolving, too: “We have grown more and more inclined from generation to generation to look to the President as the unifying force in our complex system, the leader both of his party and of the nation. To do so is not inconsistent with the actual provisions of the Constitution; it is only inconsistent with a very mechanical theory of its meaning and intention.” A president’s power, Wilson concluded, is virtually limitless: “His office is anything he has the sagacity and force to make it.”24

People with a writerly bent who were interested in understanding American democracy tended to produce, in those days, sweeping accounts of the nation’s origins and rise. During the years when Frederick Douglass and Frederick Jackson Turner were wrestling with the story of America, Wilson wrote a five-volume History of the American People and young Theodore Roosevelt churned out a four-volume series called The Winning of the West. Wilson was more interested in ideas, Roosevelt in battles.

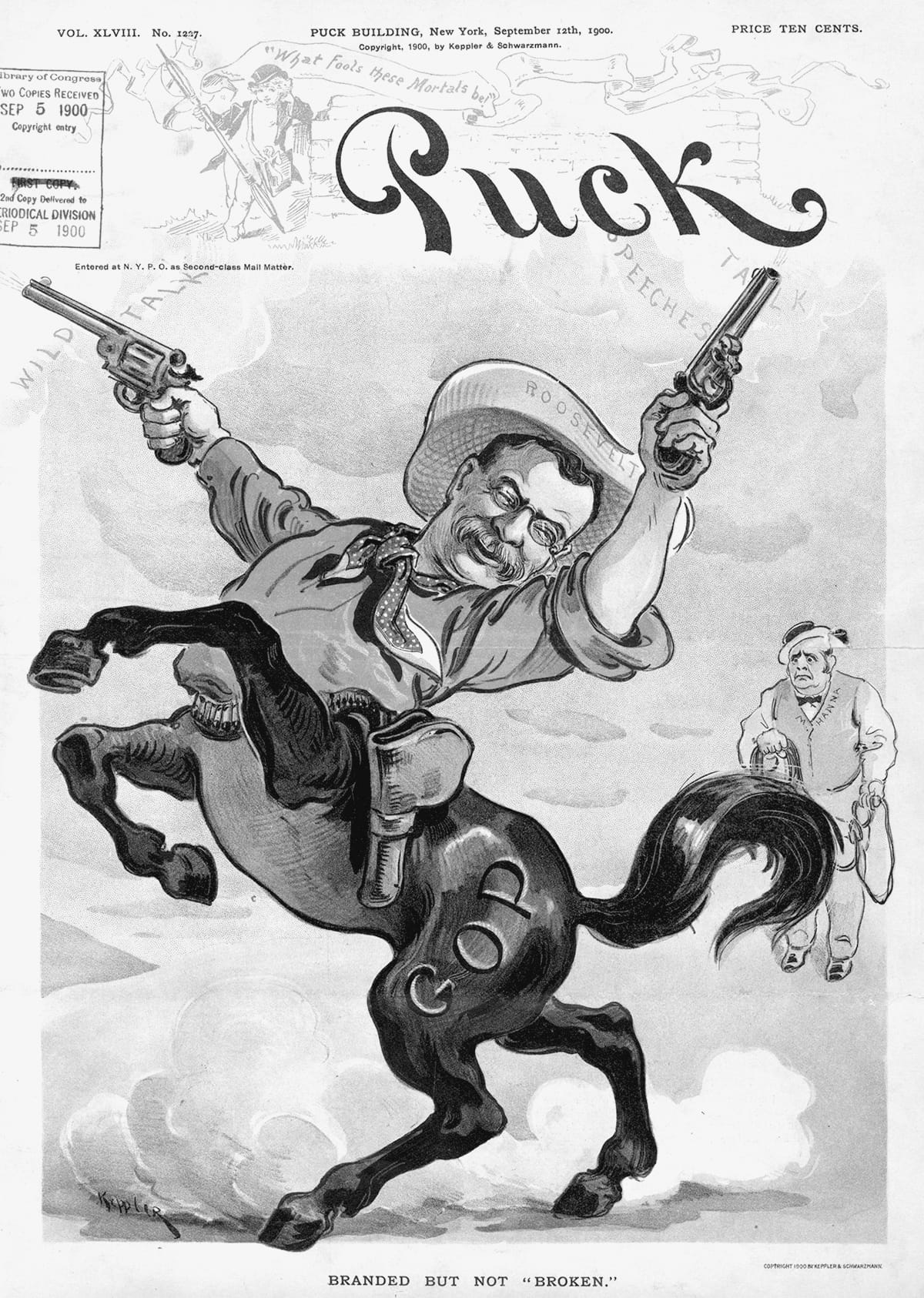

Roosevelt, who looked like a bear and roared like a lion, had finished a law degree at Columbia while serving in the New York State Assembly and spending a great deal of time at his ranch in western Dakota. But it was Roosevelt’s fighting in the Spanish-American War that catapulted him to national fame. On his return from Cuba, he was elected the Republican governor of New York. Two years later, when McKinley faced the Democratic nominee, William Jennings Bryan, he named Roosevelt as his running mate.

“It was a mistake to nominate that wild man,” McKinley’s adviser Mark Hanna always said. But that wild man proved a tireless campaigner. “He ain’t running, he’s galloping,” people said. In Roosevelt, Bryan met his match. Bryan traveled 16,000 miles on the campaign trail, so Roosevelt traveled 21,000. Bryan made 600 speeches, so Roosevelt made 673. Publicly, Roosevelt painted Bryan as a crackpot, with “communistic and socialistic doctrines”; privately, he remarked that Bryan was supported by “all the lunatics, all the idiots, all the knaves, all the cowards, and all the honest people who are slow-witted.”25 Bryan, to Roosevelt, was the candidate of the lame-brained.

When McKinley won, Democrats blamed Bryan, who, while he cornered the rural vote, had won not a single city except silver-mining Denver. Democracy appeared to be dooming the Democratic Party. In 1880, one half of the American workforce worked on farms; by 1920, only one-quarter did. A great many people worked in factories, and a rising number of them, especially women, worked in offices. In 1880, clerks made up less than 5 percent of the nation’s workforce, nearly all of them men; by 1910, more than four million Americans worked in offices, and half were women. By 1920, most Americans lived and worked in cities. Bryan’s followers were farmers, and so long as he led the party, it was hard to see how Democrats could win the White House. Said one character in a humor column, “I wondhur . . . if us dimmy-crats will iver ilict a prisidint again.”26

In 1901, when McKinley was shot by an anarchist in Buffalo, Roosevelt, only forty-two, became the nation’s youngest president. A great admirer of Lincoln, he wore on his hand a ring that contained a wisp of hair cut from the dead president’s head. He bounded in and out of rooms and slapped senators on the back, but he read widely and deeply, and even though Pulitzer’s World called him “the strangest creature the White House ever held,” he knew how to work the press. He gave reporters a permanent room at the White House, and figured out that the best day to feed them stories was Sunday, so that their pieces would run at the beginning of the week; Roosevelt liked to say that he “discovered Monday.” His lasting legacy was the regulatory state, the establishment of professional federal government and scientific agencies like the Forest and Reclamation Services. Not far behind was the series of wildlife refuges and national parks he created. Much of the rest was bluster. “I am not advocating anything revolutionary,” Roosevelt himself said. “I am advocating action to prevent anything revolutionary.”27

In the White House, Roosevelt pursued reforms long advocated by Populists. Announcing that “trusts are the creatures of the state,” he set about using antitrust fervor to enact regulatory measures, principally through the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department.28 Reelected in 1904, when he easily defeated Alton B. Parker, a conservative whom Democrats had nominated out of their vexation at Bryan, Roosevelt continued to move to the left, pursuing an agenda, not always successfully, of regulating the railroads, passing pure food and drug laws, and ending child labor.

Roosevelt also endorsed the income tax, a measure by now nearly universal in Europe. Between 1897 and 1906, supporters of the tax had introduced into Congress twenty-seven bills proposing to defeat, with a constitutional amendment, the Supreme Court’s decision in Pollock, overturning the 1894 federal income tax. “I feel sure that the people will sooner or later demand an amendment to the constitution which will specifically authorize an income tax,” Bryan said at a rally in Madison Square Garden before an adoring crowd of ten thousand, on his return from a yearlong trip around the world.29

The momentum for change came in the form of an earthquake that hit San Francisco in 1906, spreading fires across the city and, triggered by the collapse of insurance companies that were unable to cover hundreds of millions of dollars in earthquake-damage claims, a financial panic across the country. In the election of 1908, after Roosevelt pledged that he would not run for a third term, a pledge he much regretted, the Republicans nominated William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s secretary of war. The Democrats turned once again to Bryan, who demonstrated, for the third and final time, that, while he could raise a crowd to its feet and leave them weeping, he could not deliver the White House to his party.

President Taft, who had been a federal judge and who would go on to serve as chief justice of the United States, was perfectly willing to support a federal income tax, but he wanted to avoid signing a law that would end up going back to the Supreme Court: “Nothing has ever injured the prestige of the Supreme Court more than that last decision,” he said about the court’s decision in Pollock.30 Taft decided to support a constitutional amendment, which went to the states for ratification in 1909.

Constitutional amendments are notoriously difficult to pass. The Sixteenth Amendment was not, and its success is a measure of the reach and intensity of the Progressive movement. It was ratified, handily and swiftly, in 42 of 48 states, six more than required, winning passage in state senates with an average support of 89 percent and, in state houses, 95 percent. In nineteen lower legislatures, the vote in favor was unanimous. The Sixteenth Amendment became law in February 1913. The House voted on an income tax bill in May. When the Bureau of Internal Revenue printed its first 1040, the form was three pages, the instructions only one.31 Americans later came to argue about the income tax more fiercely almost than anything they’d argued about before, but when it started, they wanted it desperately, and urgently.

INDUSTRIALISM HAD BUILT towers, tipped to the sky, and had cluttered store shelves with trinkets, but it left workers with very little economic security. Beginning in the 1880s, industrializing nations had begun addressing this problem by providing “workingmen’s insurance”—health insurance, industrial accident compensation, and old-age pensions for wage workers—along with various forms of family assistance, chiefly to poor mothers or widows with dependent children. These programs created what came to be known as the modern welfare state. In the United States, the earliest of these forms of assistance were tied to military service. Between 1880 and 1910, under the terms of benefits paid to Civil War veterans and their widows and dependents, more than a quarter of the federal budget went to welfare payments. When Pennsylvania congressman William B. Wilson introduced a pension plan for all citizens over the age of sixty-five, he alluded to this tradition in the measure’s very title, calling it the Old-age Home Guard of the United States Army. Beginning in the 1880s, reformers like Jane Addams and Florence Kelley, in Chicago, had been leading a fight for legislative labor reforms for women, including minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws, and the abolition of child labor. Their first success came in 1883, when Illinois passed a law for an eight-hour workday for women. And yet each of these Progressive reforms, from social insurance to protective legislation, faced a legal obstacle: their critics called them unconstitutional.32

The Illinois Supreme Court struck down the eight-hour-workday law, and, in a particularly remarkable set of decisions issued at a time when courts were coming not only to support government intervention but also to be tools of reform, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled much Progressive labor legislation. The most important of these decisions came in 1905. In a 5–4 decision in Lochner v. New York, the U.S. Supreme Court voided a state law establishing that bakers could work no longer than ten hours a day, six days a week, on the ground that the law violated a business owner’s liberty of contract, the freedom to forge agreements with his workers, something the court’s majority said was protected under the Fourteenth Amendment. The laissez-faire conservatism of the court was informed, in part, by social Darwinism, which suggested that the parties in disputes should be left to battle it out, and if one side had an advantage, even so great an advantage as a business owner has over its employees, then it should win. In a dissenting opinion in Lochner, Oliver Wendell Holmes accused the court of violating the will of the people. “This case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain,” he began. The court, he said, had also wildly overreached its authority and had carried social Darwinism into the Constitution. “A Constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory,” Holmes wrote. “The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social Statics.”33

The Lochner decision intensified the debate about judicial review that had begun with Marbury v. Madison in 1803. Critics charged conservatives with “putting courts into politics and compelling judges to become politicians.” Meanwhile, Progressives painted themselves as advocates of the people, and, continuing a long tradition in American politics, insisted that their political position represented the people’s view of the Constitution—as against that of a corrupt judiciary. Roosevelt would eventually pledge to institute judicial recall—making it possible for justices to be essentially impeached—insisting, “the people themselves must be the ultimate makers of their own Constitution.”34

From either political vantage, the heart of the struggle concerned the constitutionality of the provisions of a welfare state. Britain, which does not have a written constitution, established the foundations for what would become a comprehensive welfare state—complete with health insurance and old-age pensions—at the very time that the United States was failing to do the same. Wilson pointed out that the Constitution, written before mass industrialization, couldn’t be expected to have anticipated it, and couldn’t solve the problems industrialization had created, unless the Constitution were treated like a living thing that, like an organism, evolved. Critics further to the left argued that the courts had become an instrument of business interests. Unions, in fact, often failed to support labor reform legislation, partly because they expected it to be struck down by the courts as unconstitutional, and partly because they wanted unions to provide benefits to their members, which would be an argument for organizing. (If the government provided those social benefits, workers wouldn’t need unions, or so some union leaders feared.)35 Meanwhile, conservatives insisted that the courts were right to protect the interests of business and that either market forces would find a way to care for sick, injured, and old workers, or (for social Darwinists) the weakest, who were not meant to thrive, would wither and die.

For all of these reasons, American Progressives campaigning for universal health insurance enjoyed far less success than their counterparts in Britain. In 1912, one year after Parliament passed a National Insurance Act, the American Association for Labor Legislation formed a Committee on Social Insurance, the brainchild of Isaac M. Rubinow, a Russian-born doctor turned policymaker who would publish, in 1913, the landmark study Social Insurance. Rubinow had hoped that “sickness insurance” would eradicate poverty. By 1915, his committee had drafted a bill providing for universal medical coverage. “No other social movement in modern economic development is so pregnant with benefit to the public,” wrote the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association. “At present the United States has the unenviable distinction of being the only great industrial nation without compulsory health insurance,” the Yale economist Irving Fisher pointed out in 1916.36 It would maintain that unenviable distinction for a century.

Congress debated Rubinow’s bill, which was also put forward in sixteen states. “Germany showed the way in 1883,” Fisher liked to say, pointing to the policy’s origins. “Her wonderful industrial progress since that time, her comparative freedom from poverty . . . and the physical preparedness of her soldiery, are presumably due, in considerable measure, to health insurance.” But after the United States declared war with Germany in 1917, critics described national health insurance as “made in Germany” and likely to result in the “Prussianization of America.” In California, the legislature passed a constitutional amendment providing for universal health insurance. But when it was put on the ballot for ratification, a federation of insurance companies took out an ad in the San Francisco Chronicle warning that it “would spell social ruin in the United States.” Every voter in the state received in the mail a pamphlet with a picture of the kaiser and the words “Born in Germany. Do you want it in California?” The measure was defeated. Opponents called universal health insurance “UnAmerican, Unsafe, Uneconomic, Unscientific, Unfair and Unscrupulous.”37

The fastest way through the constitutional thicket, it turned out, was to argue for welfare not for men but for women and children. By 1900, nearly one in five manufacturing jobs in the United States was held by a woman.38 Women and children couldn’t vote; in seeking labor reform and social insurance, they sought from the state not rights but protections. Mothers made claims on the state in the same terms as did veterans: a claim of services rendered. And even women who had not yet had children could be understood, for these purposes, as potential mothers. To that end, much of the early lobbying for protective legislation for women and children was done by the National Congress of Mothers, later known as the Parent Teacher Association, or the PTA. Founded in 1897 by Phoebe Apperson Hearst, the mother of the newspaper tycoon, and Alice McLellan Birney, the wife of a Washington, DC, lawyer, the National Congress of Mothers aimed to serve as a female auxiliary to the national legislature. “This is the one body that I put even ahead of the veterans of the Civil War,” Theodore Roosevelt declared in 1908, “because when all is said and done it is the mother, and the mother only, who is a better citizen even than the soldier who fights for his country.”39

Women were also consumers. In 1899, Florence Kelley, the daughter of an abolitionist who had helped found the Republican Party, became the first general secretary of the National Consumers League. Her motto: “Investigate, record, agitate.” Kelley, born in Philadelphia in 1856, had studied at Cornell and in Zurich, where she became a socialist; in 1885, she translated the work of Friedrich Engels. In the 1890s, while working at Jane Addams’s Hull House in Chicago, she’d earned a law degree at Northwestern. Eyeing the court’s decision in Lochner, and understanding that the courts treated women differently than men, Kelley wondered whether maximum-hour legislation might have a better chance of success in the courts if the test case were a law aimed specifically at female workers. Already, state courts had made rulings in that direction. In 1902, the Nebraska Supreme Court decreed that “the state must be accorded the right to guard and protect women as a class, against such a condition; and the law in question, to that extent, conserves the public health and welfare.”40

For women, who were not written into the Constitution, wining constitutional arguments has always required constitutional patching: cutting and pasting, scissors and a pot of glue. In an era in which the court plainly favored arguments that stopped short of actual equality—Plessy v. Ferguson, after all, had instituted the doctrine of “separate but equal” rather than provide equal protection to African Americans—Kelley tried arguing that women, physically weaker than men, deserved special protection.41

In 1906, the Oregon Supreme Court upheld a female ten-hour law that had been challenged by a laundryman named Curt Muller; Muller appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Kelley arranged for a lawyer named Louis Brandeis to argue the case for Oregon. Brandeis, known as “the people’s attorney,” was born in Kentucky in 1856, graduated from Harvard Law School in 1876, and married Alice Goldmark in 1891. Much of his legwork in the Muller case was done by the indefatigable reformer Josephine Goldmark, who worked for Kelley and was also Brandeis’s sister-in-law.42 Goldmark compiled the findings of hundreds of reports and studies by physicians, municipal health boards, public health departments, medical societies, factory inspectors, and bureaus of labor, demonstrating the harm done to women by working long hours. She presented Brandeis with a 113-page amicus brief that Brandeis submitted to the Supreme Court in 1908 in Muller v. Oregon. “The decision in this case will, in effect, determine the constitutionality of nearly all the statutes in force in the United States, limiting the hours of labor of adult women,” Brandeis explained, arguing that overwork “is more disastrous to the health of women than of men, and entails upon them more lasting injury.” The Oregon law was upheld.

Muller v. Oregon established the constitutionality of labor laws (for women), the legitimacy of sex discrimination in employment, and the place of social science research in the decisions of the courts. The “Brandeis brief,” as it came to be called, essentially made muckraking admissible as evidence. Where the court in Plessy v. Ferguson had scorned any discussion of the facts of racial inequality, citing the prevailing force of tradition, Muller v. Oregon established the conditions that would allow for the presentation of social science evidence in the case that would overrule racial segregation, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, in 1954.43

“History discloses the fact that woman has always been dependent upon man,” Brandeis argued in Muller v. Oregon. “Differentiated by these matters from the other sex, she is properly placed in a class by herself, and legislation designed for her protection may be sustained, even when like legislation is not necessary for men and could not be sustained.”44 Kelley used this difference as a wedge. Between 1911 and 1920, laws providing relief for women in the form of mothers’ and widows’ pensions passed in forty states; between 1909 and 1917, maximum-hour laws for women passed in thirty-nine states; and between 1912 and 1923, minimum-wage laws for women passed in fifteen states.45

But Kelley and female protectionists had made a Faustian bargain. These laws rested on the idea that women were dependent, not only on men, but on the state. If women were ever to achieve equal rights, this sizable body of legislation designed to protect women would stand in their way.

MULLER V. OREGON set the brilliant Louis Brandeis in a new direction. He became interested in the new field of “efficiency” as a means of addressing the problems of relations between labor and business. Brandeis became convinced that “efficiency is the hope of democracy.”46

The efficiency movement began when Bethlehem Steel Works, in Pennsylvania, hired a mechanical engineer from Philadelphia named Frederick Winslow Taylor to speed production, which Taylor proposed to do with a system he called “task management” or, later, “The Gospel of Efficiency.” As Taylor explained in 1911 in his best-selling book, The Principles of Scientific Management, he timed the Bethlehem steelworkers with a stopwatch, identified the fastest worker, a “first-class man,” from among “ten powerful Hungarians,” and calculated the fastest rate at which a unit of work could be done. Thenceforth all workers were required to work at that rate or lose their jobs.47 Taylor, though, had made up most of his figures. After charging Bethlehem Steel two and a half times what he could possibly have saved the company in labor costs, he, too, was fired.48 Nevertheless, Taylorism endured.

Efficiency promised to speed production, lower the cost of goods, and improve the lives of workers, goals it often achieved. It was also a way to minimize strikes and to manage labor—particularly immigrant labor.

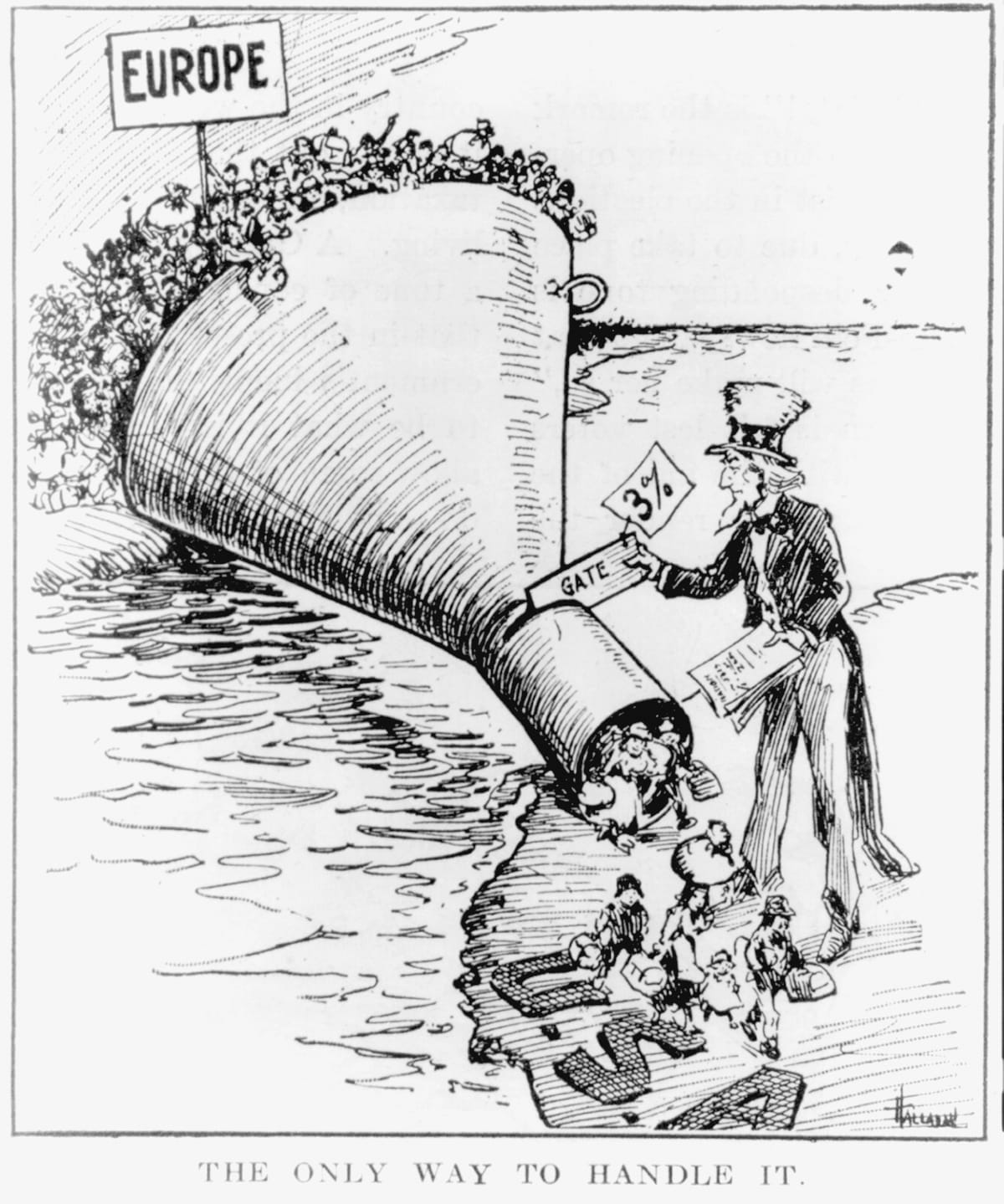

Before 1896, European immigrants to the United States had chiefly come from northern and western Europe, and especially from Germany and Ireland. After 1896, most came from the south and the east, and especially from Italy and Hungary. Slavs, Jews, and Italians, lumped together as the “new immigrants,” also came in far greater numbers than Europeans had ever come before, sometimes more than a million a year. The number of Europeans who arrived in the twelve years between 1902 and 1914 alone totaled more than the number of Europeans who arrived in the four decades between 1820 and 1860.49

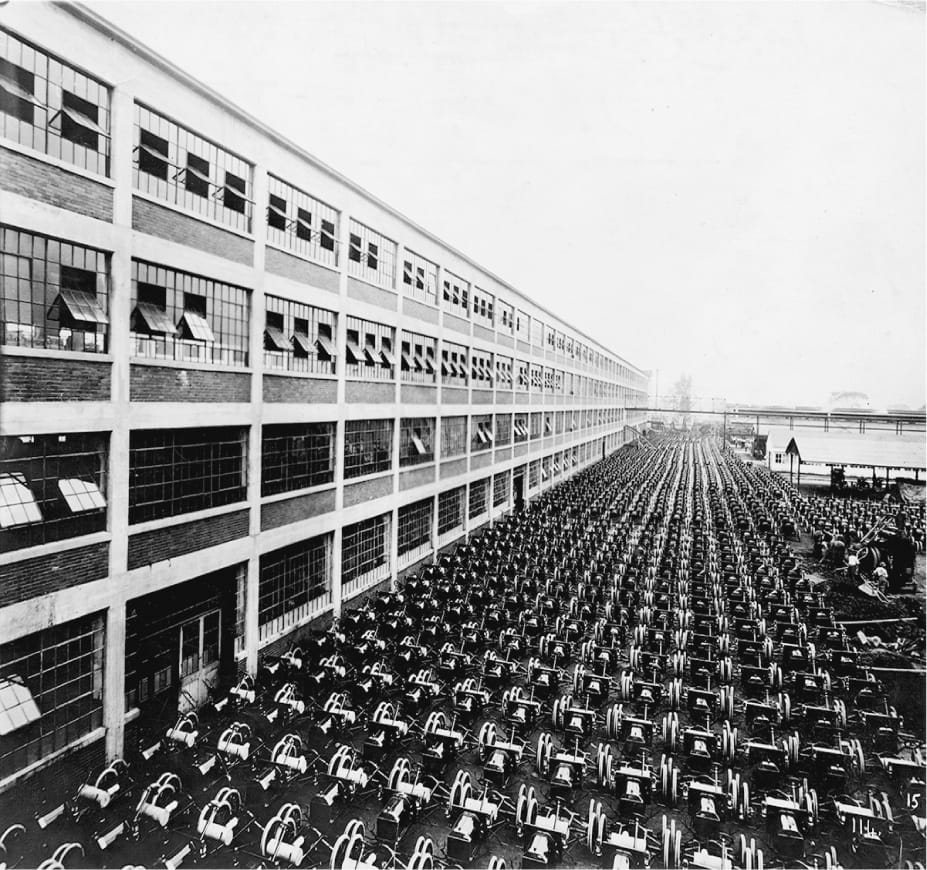

No one implemented the regime of efficiency better than Henry Ford. In 1903, Ford, the forty-year-old son of Michigan farmers, opened a motor car company in Detroit, where workers, timed by a clock, put together parts on an assembly line. By 1914, Ford’s plant was manufacturing nearly a quarter of a million cars every year, cars that cost one-quarter of what he’d sold them for a decade earlier.50 Before the automobile, only businesses owned large machines. As Walter Chrysler explained, “We were making the first machine of considerable size in the history of the world for which every human being was a potential customer.”51 If the railroad served as the symbol of progress in the nineteenth century, the automobile served as its symbol in the twentieth, a consumer commodity that celebrated individualism and choice. Announced Ford: “Machinery is the new Messiah.”52

Efficiency reached into family life with the founding of “home economics.”53 Ford exerted particular control over the home lives of his largely immigrant workers, by way of a Sociological Department. “Employees should use plenty of soap and water in the home, and upon their children, bathing frequently,” one pamphlet recommended. “Nothing makes for right living and health so much as cleanliness. Notice that the most advanced people are the cleanest.” Ford also founded an English School, to Americanize his immigrant workers, using the same methods of assembly that he used in his plant. “There is a course in industry and efficiency, a course in thrift and economy, a course in domestic relations, one in community relations, and one in industrial relations,” Ford’s English School announced. “This is the human product we seek to turn out, and as we adapt the machinery in the shop to turning out the kind of automobile we have in mind, so we have constructed our educational system with a view to producing the human product we have in mind.”54

Brandeis came to believe that Taylorism could solve the problems of mass industrialism and mass democracy. While preparing to appear before the Interstate Commerce Committee on railroad freight rates, Brandeis called a meeting of efficiency experts.55 In the Commerce Committee hearings, he argued that, instead of raising their freight rates, railroads ought to do their work more efficiently. With scientific management, Brandeis said, railroad companies could save one million dollars a day. He won the argument, but the people who worked on railroads and in factories soon began attempting to convince him that those savings came at their expense. The next year, when Brandeis gave a speech about efficiency to a labor union, one woman shouted at him, “You can call it scientific management if you want to, but I call it scientific driving.”56

Some members of Congress suspected the same. In 1912, William B. Wilson, who’d gone down into the coal pits at the age of nine and joined the union at eleven, chaired a House Special Committee to Investigate the Taylor and Other Systems of Shop Management. When Taylor, called to testify, talked about “first-class men,” Wilson inquired about workers who weren’t first-class, men whom Taylor had described as dumb as dray horses. “Scientific management has no place for such men?” Wilson asked. “Scientific management has no place for a bird that can sing and won’t sing,” answered Taylor. “We are not . . . dealing with horses nor singing birds,” Wilson told Taylor. “We are dealing with men who are a part of society and for whose benefit society is organized.57

Were men animals? Were men machines? Was machinery a messiah, and efficiency a gospel? With businesses driving workers to toil at breakneck speed, a growing number of Americans were drawn to socialism, especially since neither of the two major parties had any good answer to William B. Wilson’s anguished exchange with Frederick Winslow Taylor. One union man in Schenectady said, “People got mighty sick of voting for Republicans and Democrats when it was a ‘heads I win, tails you lose’ proposition.” In the presidential election of 1908, more than 400,000 people voted for the Socialist Party candidate, Eugene Debs. In 1911, Socialists were elected as the mayors of eighteen cities and towns and more than a thousand Socialists held offices in thirty states.58

Heads or tails was how the Democrats and Republicans looked to a lot of people in 1912, too, when Debs ran again, Woodrow Wilson won the Democratic nomination, and Theodore Roosevelt hoped to win the Republican one. Wilson believed that it was the obligation of the federal government to regulate the economy to protect ordinary Americans “from the consequences of great industrial and social processes which they cannot alter, control, or singly cope with.” This scarcely distinguished him from Roosevelt. “The object of government is the welfare of the people,” Roosevelt said. As Roosevelt put it, “Wilson is merely a less virile me.”59

The election of 1912 amounted to a referendum on Progressivism, much influenced by the political agitation of women. “With a suddenness and force that have left observers gasping women have injected themselves into the national campaign this year in a manner never before dreamed of in American politics,” the New York Herald reported, though only reporters who hadn’t been paying attention saw anything sudden about it.60

Having fought for their rights formally since 1848, women had achieved the right to vote in eight states: Colorado (1893), Idaho (1896), Utah (1896), Washington (1910), California (1911), Arizona (1912), Kansas (1912) and Oregon (1912). They’d also begun fighting for a great deal more than suffrage. The word “feminism” entered English in the 1910s, as a generation of independent women, many of them college-educated—New Women, they were called—fought for equal education, equal opportunity, equal citizenship, and equal rights, and, not least, for birth control, a term coined by a nurse named Margaret Sanger when she launched the first feminist newspaper, The Woman Rebel, in 1914. In 1912 and again in 1916, suffragists marched on the streets of cities across the country, organized on the campuses of women’s colleges, and staged hunger strikes. They waged old-style political campaigns, with buttons and banners. They flew in balloons. They decorated elephants and donkeys. Women who’d gone to prison for picketing took a train across the country in a Prison Special, wearing their prison uniforms. They dressed as statues; they wore red, white, and blue; they marched in chains. They waged a moral crusade, in the style of abolitionists, but on the streets, in the style of Jacksonian Democrats.61

Roosevelt, in an extraordinary campaign for direct democracy and social justice, hoped to wrest the Republican nomination from Taft partly by appealing to female voters, but mainly by availing himself of another Progressive reform: the direct primary. Progressive reformers, viewing nominating conventions as corrupt, had fought instead for state primaries, in which voters could choose their own presidential candidates. The first primary was held in 1899; the reform, led by Wisconsin’s Robert La Follette, gained strength in 1905. “Let the People Rule” became Roosevelt’s 1912 slogan. “The great fundamental issue now before the Republican Party and before our people can be stated briefly,” he said. “It is: Are the American people fit to govern themselves, to rule themselves, to control themselves? I believe they are. My opponents do not.” Thirteen states held primaries (all were nonbinding); Roosevelt won nine.62

As with the secret ballot, primaries were part Progressive reform, part Jim Crow. Roosevelt needed to win them because, at the Republican National Convention, he had no real chance of winning black delegates. Because the Republican Party had virtually no white support in the South, the only southern delegates were black delegates, men who had been appointed to party offices by the Taft administration. Roosevelt tried in vain to wrest them from their support for the president. “I like the Negro race,” he said in a speech at an AME Church the day before the convention. But the next day the New York Times produced affidavits proving that Roosevelt’s campaign wasn’t so much trying to court black delegates as to bribe them. After Roosevelt lost the nomination to Taft, he formed the Progressive Party, whose convention refused to seat black delegates. “This is strictly a white man’s party,” said one of Roosevelt’s supporters, a leader of the so-called Lily Whites.63

But the Progressive Party was not, in fact, strictly a white man’s party; it was also a white woman’s party. Roosevelt’s new party adopted a suffrage plank and Roosevelt promised to appoint Jane Addams to his cabinet.64 Addams gave the second nominating speech at the convention, after which she marched across the hall carrying a “Votes for Women” flag. Returning to her office, she found a telegram from a black newspaper editor that read: “Woman suffrage will be stained with Negro Blood unless women refuse all alliance with Roosevelt.”65

Roosevelt’s 1912 campaign marked a turn in American politics by venturing the novel idea that a national presidential administration answers national public opinion without the mediation either of parties, or of representatives in Congress. The candidate, Roosevelt suggested, is more important than the party. Roosevelt also used film clips and mass advertising in a way that no candidate had done before, gathering a national following through the tools of modern publicity and bypassing the party system by reaching voters directly. That he failed to win the presidency did not diminish the influence of this new conception of the nature of American political and constitutional arrangements.66

In the end, Roosevelt won 27 percent of the popular vote (more than any third-party candidate either before or since), but, having drawn most of those votes from Taft, Roosevelt’s campaign allowed Wilson to gain the White House, the first southern president elected since the Civil War. Democrats controlled both houses of Congress, too, for the first time in decades. “Men’s hearts wait upon us,” Wilson said in his inaugural address, before the largest crowd ever gathered at an inauguration.67 Wilson, having earned the endorsement of William Jennings Bryan, rewarded him by naming him his secretary of state. At the inauguration, Bryan sat right behind Wilson, a measure of the distance populism had traveled from the prairies of Kansas and Nebraska.

Few presidents have achieved so much so quickly as did Wilson, who delivered on an extraordinary number of his promised Progressive reforms. Learning from Roosevelt’s good relationship with the press while in the White House, Wilson, in his first month, invited more than a hundred reporters to his office, fielded questions, and announced that he intended to do this regularly: in his first ten months alone, he held sixty press conferences. The author of Congressional Government also kept the Sixty-Third Congress in session for eighteen months straight, longer than Congress had ever met before. Congress obliged by lowering the tariff; reforming banking and currency laws; abolishing child labor; and passing a new antitrust act, the first eight-hour work-day legislation and the first federal aid to farmers.

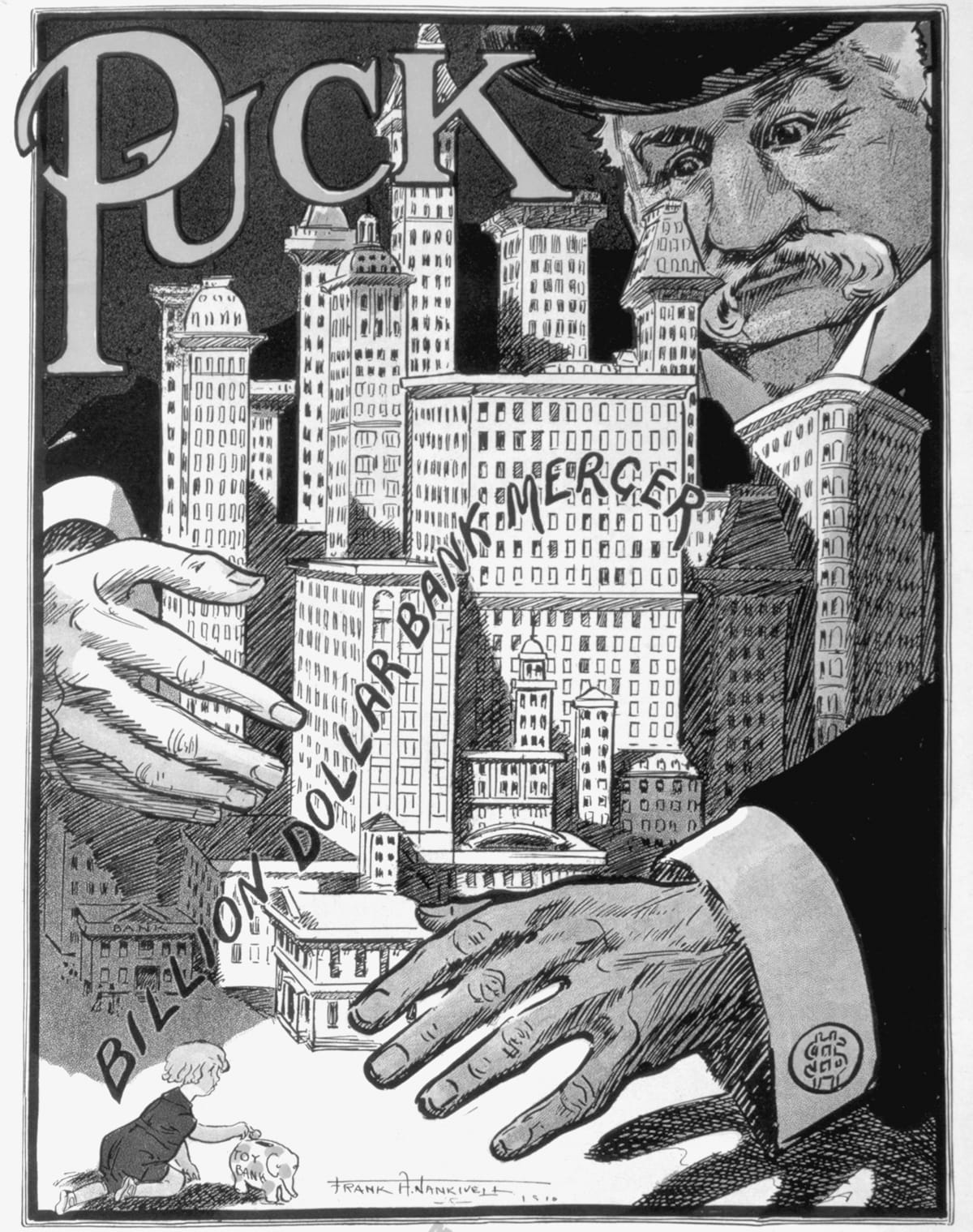

Among Wilson’s hardest fights was his nomination of Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court, one of the most controversial in the court’s history, not because Brandeis was the first Jew appointed to the court, though that was controversial in some quarters, but because Brandeis was a dogged opponent of plutocrats. Beyond the cases he’d argued, Brandeis had become something of a muckraker, publishing an indictment of the plutocracy, Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It, parts of which sounded as though they could have been written by the likes of Mary E. Lease. “The power and the growth of power of our financial oligarchs comes from wielding the savings and quick capital of others,” he wrote. “The fetters which bind the people are forged from the people’s own gold.” He pointed out that J. P. Morgan and the First National and National City Bank together held “341 directorships in 112 corporations having aggregate resources or capitalization of $22,245,000,000,” a sum that is “more than three times the assessed value of all the real estate in the City of New York” and “more than the assessed value of all the property in the twenty-two states, north and south, lying west of the Mississippi River.” During the Judiciary Committee debates over Brandeis’s nomination, one senator remarked, “The real crime of which this man is guilty is that he has exposed the iniquities of men in high places in our financial system.”68

Wilson fought hard for Brandeis, and won, and Brandeis’s presence on the bench made all the difference to endurance of Progressive reform. But, like other Progressives, Wilson not only failed to offer any remedy for racial inequality; he endorsed it. On the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, he spoke on the battlefield at a reunion of more than fifty thousand Union and Confederate veterans. “A Reunion of whom?” asked the Washington Bee: black soldiers were not included. It was, instead, a reunion between whites in the North and the South, an agreement to remember the Civil War as a war over states’ rights, and to forget the cause of slavery. “We have found one another again as brothers and comrades in arms, enemies no longer, generous friends rather, our battles long past, the quarrel forgotten,” Wilson told the veterans at Gettysburg. A week later, his administration mandated separate bathrooms for blacks and whites working in the Treasury Department; soon he segregated the entire civil service, bringing Jim Crow to the nation’s capital.69

“There may have been other Presidents who held the same sort of sentiments,” wrote the NAACP’s James Weldon Johnson, “but Mr. Wilson bears the discreditable distinction of being the first President of the United States, since Emancipation, who openly condoned and vindicated prejudice against the Negro.”70 Jim Crow thrived because, after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, reformers who had earlier fought for the cause of civil rights abandoned it for the sake of forging a reunion between the states and the federal government and between the North and the South. This wasn’t Wilson’s doing; this was the work of his generation, the work of the generation that came before him, and the work of the generation that would follow him, an abdication of struggle, an abandonment of justice.

II.

WAR BROKE OUT in Europe in July of 1914, war on a scale that had never been seen before, a war run by efficiency experts and waged with factory-made munitions, a war without limit or mercy. Machines slaughtered the masses. Europe fell to its knees. The United States rose to its feet. The Great War brought the United States into the world. It marked the end of Europe’s reign as the center of the Western world; that place, after the war, was held by the United States.71

At the start, Americans only watched, numb, shocked to discover that the nineteenth-century’s great steam-powered ship of progress had carried its all-too-trusting passengers to the edge of an abyss. “The tide that bore us along was then all the while moving to this as its grand Niagara,” wrote Henry James.72 The scale of death in the American Civil War, so staggering at the time—750,000 dead, in four years of fighting—looked, by comparison, minuscule. Within the first eight weeks of the war alone, nearly 400,000 Germans were killed, wounded, sick, or missing. In 1916, over a matter of mere months, there were 800,000 military casualties in Verdun and 1.1 million at the Somme. But civilians were slaughtered, too. The Ottoman government massacred as many as 1.5 million Armenians. For the first time, war was waged by airplane, bombs dropped from a great height, as if by the gods themselves. Cathedrals were shelled, libraries bombed, hospitals blasted. Before the war was over, nearly 40 million people had been killed and another 20 million wounded.73

What sane person could believe in progress in an age of mass slaughter? The Great War steered the course of American politics like a gale-force wind. The specter of slaughter undercut Progressivism, suppressed socialism, and produced anticolonialism. And, by illustrating the enduring wickedness of humanity and appearing to fulfill prophecies of apocalypse as a punishment for the moral travesty of modernism, the war fueled fundamentalism.

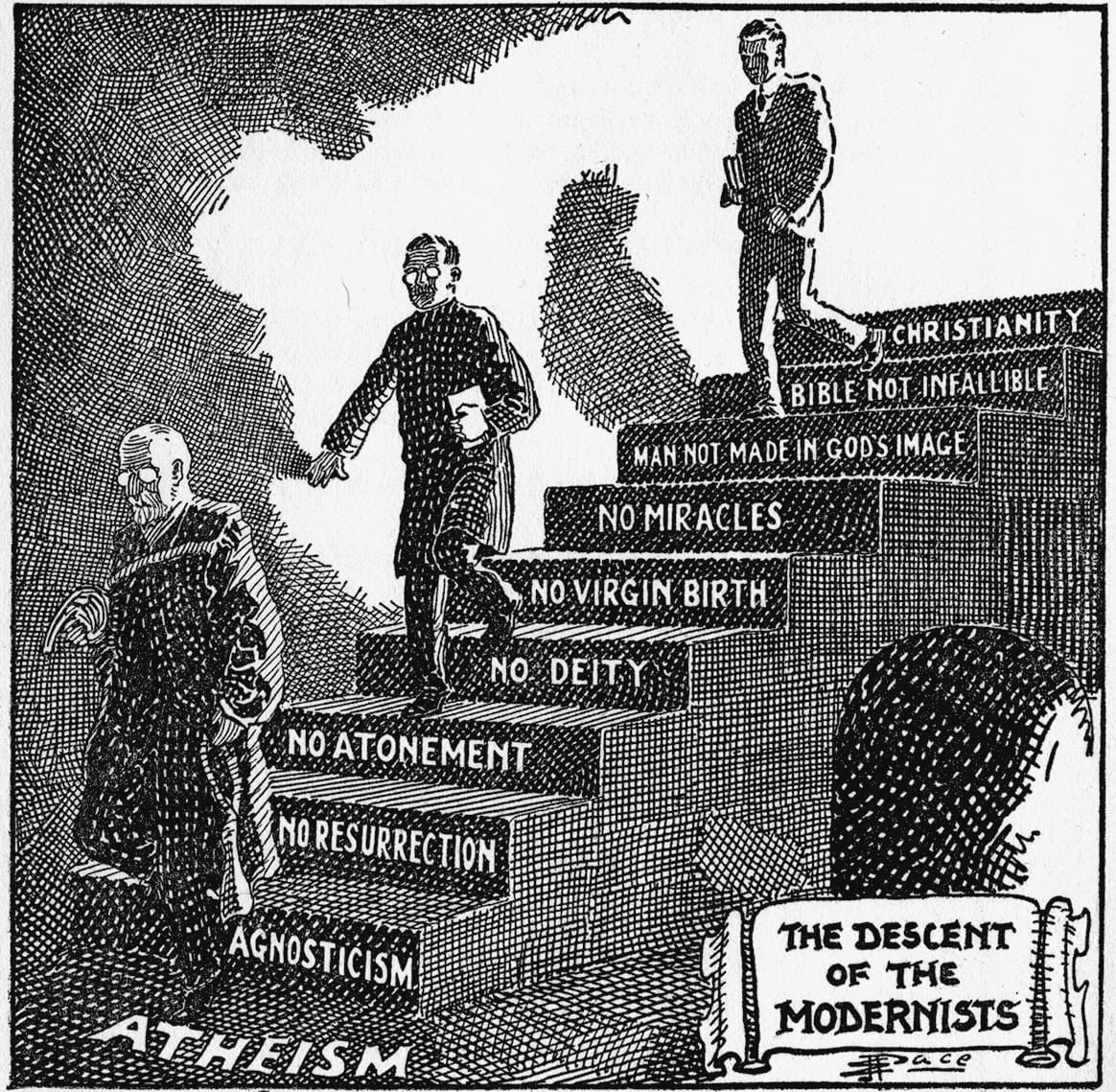

Fundamentalists’ dissent from Protestantism had to do with the idea of truth, a dissent that would greatly influence the history of a nation whose creed rests on a very particular set of truths. Fundamentalism began with a rejection of Darwinism. Some of fundamentalism’s best-remembered preachers are southerners who moved west, like the Alabama-born Texas Baptist J. Frank Norris, six foot one and hard as oak. “I was born in the dark of the moon, in the dog-fennell season, just after a black cat had jumped upon a black coffin,” Norris liked to say. Ordained in 1897, Norris went on to rail against “that hell-born, Bible-destroying, deity-of-Christ-denying, German rationalism known as evolution.”74 But fundamentalism began among educated northern ministers. Influenced by Scottish commonsense philosophers, early fundamentalists like the Princeton Theological Seminary’s Charles Hodge maintained that the object of theology was to establish “the facts and principles of the Bible.” Darwinism, Hodge thought, would lead to atheism. He then declared the Bible “free from all error,” a position his son, A. A. Hodge, also a professor at Princeton, carried further. (The younger Hodge insisted that it was the originals of the Scriptures that were free from error, not the copies; the originals do not survive. This distinction usually went unnoticed by his followers.)

By insisting on the literal truth of the Bible, fundamentalists dared liberal theologians and Social Gospelers into a fight, especially after the publication, beginning in 1910, of a twelve-volume series of pamphlets called The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth. The purpose of a church is to convert people to Christ by teaching the actual, literal gospel, fundamentalists insisted, not by preaching good works and social justice. “Some people are trying to make a religion out of social service with Jesus Christ left out,” the revivalist and ex–baseball player Billy Sunday complained in 1912. “We’ve had enough of this godless social service nonsense.”75

William Jennings Bryan, Mr. Fundamentalist, was not actually a fundamentalist. For one, he believed in the Social Gospel; for another, he does not appear ever to have owned a copy of The Fundamentals and, as a man unconcerned with theological matters, he hardly ever bothered defending the literal truth of the Bible. “Christ went about doing good” was the sum of Bryan’s theology. Bryan was confused for a fundamentalist because he led a drive to prohibit the teaching of evolution in the nation’s schools. But Bryan saw the campaign against evolution as another arm of his decades-long campaign against the plutocracy, telling a cartoonist, “You should represent me as using a double-barreled shotgun fixing one barrel at the elephant as he tries to enter the treasury and another at Darwinism—the monkey—as he tries to enter the schoolroom.”76

Bryan’s difficulty was that he saw no difference between Darwinism and social Darwinism, but it was social Darwinism that he attacked, the brutality of a political philosophy that seemed to believe in nothing more than the survival of the fittest, or what Bryan called “the law of hate—the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill the weak.”77 How could a war without mercy not set this movement aflame? Germany was the enemy, the same Germany whose model of education had secularized American colleges and universities, which were now teaching eugenics, sometimes known as the science of human betterment, calling for the elimination from the human race of people deemed unfit to reproduce on the basis of their intelligence, criminality, or background.

Bryan wasn’t battling a chimera. American universities were indeed breeding eugenicists. Zoologist Charles Davenport was a professor at Harvard when he wrote Statistical Methods, with Special Reference to Biological Variation. In 1910, in Eugenics, he defined the field as “the science of human improvement by better breeding.” Biologist David Jordan was president of Stanford in 1906 when he headed a committee of the American Breeders’ Association (an organization founded by Davenport) whose purpose was to “investigate and report on heredity in the human race” and to document “the value of superior blood and the menace to society of the inferior.”78

Nor was this academic research without consequence. Beginning in 1907, with Indiana, two-thirds of American states passed forced sterilization laws. In 1916, Madison Grant, the president of the Museum of Natural History in New York, who had degrees from Yale and Columbia, published The Passing of the Great Race; Or, the Racial Basis of European History, a “hereditary history” of the human race, in which he identified northern Europeans (the “blue-eyed, fair-haired peoples of the north of Europe” that he called the “Nordic race”) as genetically superior to southern Europeans (the “dark-haired, dark-eyed” people he called “the Alpine race”) and lamented the presence of “swarms of Jews” and “half-breeds.” In the United States, Grant argued, the Alpine race was overwhelming the Nordic race, threatening the American republic, since “democracy is fatal to progress when two races of unequal value live side by side.”79

Progressives mocked fundamentalists as anti-intellectual. But fundamentalists were, of course, making an intellectual argument, if one that not many academics wanted to hear. In 1917, William B. Riley, who, like J. Frank Norris, had trained at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, published a book called The Menace of Modernism, whose attack on evolution included a broader attack on the predominance in public debate of liberal faculty housed at secular universities—and the silencing of conservative opinion. Conservatives, Riley pointed out, have “about as good a chance to be heard in a Turkish harem as to be invited to speak within the precincts of a modern State University.” In 1919, Riley helped bring six thousand people to the first meeting of the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association. The horror of the war fueled the movement, convincing many evangelicals that the growing secularization of society was responsible for this grotesque parade of inhumanity: mass slaughter. “The new theology has led Germany into barbarism,” one fundamentalist argued in 1918, “and it will lead any nation into the same demoralization.”80

Even as Americans reeled at the slaughter in Europe, the United States edged toward war. “There will be no war while I am Secretary of State,” Bryan had pledged when he joined Woodrow Wilson’s administration.81

But in 1915 Bryan resigned, unable to halt the drift toward American entry into the war. Peace protests, mainly led by women, had begun just weeks after war broke out. At a Women’s Peace Parade in New York in the summer of 1914, fifteen thousand women marched, dressed in mourning. Meanwhile, women were also marching for suffrage, the two causes twining together, on the theory that if women could vote, they’d vote against sending their sons and husbands to war.

In 1916, Wilson campaigned for reelection by pledging to keep the United States out of the war. The GOP nominated former Supreme Court justice Charles Evans Hughes, who took the opposing position. “A vote for Hughes is a vote for war,” explained a senator from Oklahoma. “A vote for Wilson is a vote for peace.”82

“If my re-election as President depends upon my getting into war, I don’t want to be President,” Wilson said privately. “He kept us out of war” became his campaign slogan, and when Theodore Roosevelt called that an “ignoble shirking of responsibility,” Wilson countered, “I am an American, but I do not believe that any of us loves a blustering nationality.”83

Wilson had withheld support from female suffrage, but women who could vote tended to favor peace. Suffragist Alice Paul decided that women, spurned by both parties, needed a party of their own. The National Woman’s Party proceeded to parade through the streets of Denver with a donkey named Woodrow who carried a sign that read “It means freedom for women to vote against the party this donkey represents.” Paul did not prevail. In the end it was women voters who, by rallying behind the peace movement, gained Wilson a narrow victory: he won ten out of the twelve states where women could vote.84

But as Wilson prepared for his second term, women fighting for equal rights dominated the news. In Brooklyn, Margaret Sanger and her sister Ethel Byrne, also a nurse, had opened the first birth control clinic in the United States. Sanger argued that the vote was nothing compared to the importance of birth control, especially for poor women, a position that might have seemed to align with conservative eugenicists, but which did not, since they were opposed to feminism. Arrested for violating a New York penal code that prevented any discussion of contraception, Ethel Byrne was tried in January 1917; the story appeared in newspapers across the country. Her lawyer argued that the penal code was unconstitutional, insisting that it infringed on a woman’s right to the “pursuit of happiness.” Byrne was found guilty on January 8; in prison, she went on a hunger strike. Two days later, Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party began a suffrage vigil outside the White House, carrying signs reading “Mr. President How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?”85

Public support for suffrage plummeted as the United States grew closer to entering the war and questioning the president began to look like disloyalty. In January 1917, Wilson released an intercepted telegram from the German minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador in Mexico in which Zimmermann asked Mexico to enter the war as Germany’s ally, promising to help “regain for Mexico the ‘lost territories’ of New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas should the U.S. declare War on Germany.”86 Days after Wilson was inaugurated, German U-boats sank three American ships. Wilson concluded that there was no longer any way to stay out of the war. At the beginning of April, he asked Congress to declare war.

“The world must be made safe for democracy,” Wilson told Congress. Not everyone was persuaded. “I want especially to say, Mr. President, that I am not voting for war in the name of democracy,” Ohio’s Warren G. Harding said on the Senate floor. “It is my deliberate judgment that it is none of our business what type of government any nation on this earth may choose to have. . . . I voted for war tonight for the maintenance of American rights.”87

Congress declared war. But Wilson’s claim that the United States was fighting to make the world safe for democracy was hard for many to swallow. Wilson had in fact pledged not to make the world democratic, or even to support the establishment of democratic institutions everywhere, but instead to establish the conditions of stability in which democracy was possible. A war for peace it was not. The war required a massive mobilization: all American men between eighteen and forty-five had to register for the draft; nearly five million were called to serve. How were they to be persuaded of the war’s cause? In a speech to new recruits, Wilson’s new secretary of state, Robert Lansing, ventured an explanation. “Were every people on earth able to express their will, there would be no wars of aggression and, if there were no wars of aggression, then there would be no wars, and lasting peace would come to this earth,” Lansing said, stringing one conditional clause after another. “The only way that a people can express their will is through democratic institutions,” Lansing went on. “Therefore, when the world is made safe for democracy . . . universal peace will be an accomplished fact.”88

Wilson, the political scientist, tried to earn the support of the American people with an intricate theory of the relationship between democracy and peace. It didn’t work. To recast his war message and shore up popular support, he established a propaganda department, the Committee on Public Information, headed by a baby-faced, forty-one-year-old muckraker from Missouri named George Creel, best-known for an exposé on child labor called Children in Bondage. Creel applied the methods of Progressive Era muckraking to the work of whipping up a frenzy for fighting. His department employed hundreds of staff and thousands of volunteers, spreading pro-war messages by print, radio, and film. Social scientists called the effect produced by wartime propaganda “herd psychology”; the philosopher John Dewey called it the “conscription of thought.”89

The conscription of thought also threatened the freedom of speech. To suppress dissent, Congress passed a Sedition Act in 1918. Not since the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 had Congress so brazenly defied the First Amendment. Fewer than two dozen people had been arrested under the 1798 Sedition Act. During the First World War, the Justice Department charged more than two thousand Americans with sedition and convicted half of them. Appeals that went to the Supreme Court failed. Pacifists, and feminists went to prison, and so, especially, did socialists. Ninety-six of the convicted were members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), including its leader, Bill Haywood, sentenced to twenty years in prison. Eugene Debs was sentenced to a ten-year term for delivering a speech in which he’d told his listeners that they were “fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder.”90