Eleven

A CONSTITUTION OF THE AIR

“OUR WHOLE BUSINESS SYSTEM WOULD BREAK DOWN IN a day if there was not a high sense of moral responsibility in our business world,” said bulldog-faced Herbert Hoover while campaigning for president in 1928, at the age of fifty-three. Hoover had earned the reputation of a savior, along with the nickname “Master of Emergencies,” which was also the title of his campaign film, a chronicle of his relief work in Europe during the war and in Mississippi during the 1927 flood, featuring footage so moving—ashen, hollow children fed, at last—that it reduced theater audiences to tears. One of the most devoted and talented Americans ever to seek the White House, Hoover believed that the philosophy of moral progress that had animated both American politics and American protest since the nation’s founding had come to be best represented by the leaders of American businesses, private citizens who, he thought, possessed a commitment to the public interest as unwavering as his own.1 Nothing so well illustrated his idea of a government-business partnership as radio, an experimental technology in which Hoover, a consummate engineer, invested the hope of American democracy.

As secretary of commerce and undersecretary of everything, Hoover had convened a series of annual radio conferences at the White House between 1922 and 1925, bringing together government agencies, news organizations, and manufacturers, including the fledgling Radio Corporation of America. At the time, there were 220 radio stations in the United States, and 2.5 million radio sets. Telegraph and telephone lines had wired the Republic together by miles of cable, like so many strings of Christmas lights; radio, riding on waves of air, could go anywhere. Nevertheless, early radio sets worked like the telegraph and telephone and were used for point-to-point communication, often ship-to-shore. Hoover understood that the future of radio was in “broadcasting” (a usage coined in 1921), transmitting a message to receivers scattered across great distances, like sowing so many seeds across a field. He rightly anticipated that radio, the nation’s next great mechanical experiment, would radically transform the nature of political communication: radio would make it possible for political candidates and officeholders to speak to voters without the bother and expense of traveling to meet them, and it would also make governing an intimate affair. NBC radio began broadcasting in 1926, CBS in 1928. By the end of the decade, nearly every household would have a wireless—often a homemade one. Hoover promised that broadcasting would make Americans “literally one people.”2

Hoover refused to leave this to chance, or to the public-mindedness of businessmen. The chaos of the early airwaves convinced him that the government had a role to play in regulating the airwaves by issuing licenses to frequencies and by insisting that broadcasters answer to the public interest. “The ether is a public medium,” he insisted, “and its use must be for the public benefit.”3 He pressed for passage of the Federal Radio Act, sometimes called the Constitution of the Air. Passed in 1927, it proved to be one of the most consequential acts of Progressive reform.

Under the terms of the Radio Act, the Federal Radio Commission (later the Federal Communications Commission) adopted an equal-time policy, and debates between political candidates became one of early radio’s most popular features. Hoover would later grow troubled by the world radio had wrought. “Radio lends itself to propaganda far more easily than the press,” he remarked in his memoirs. But his earlier technological utopianism was widely shared: wasn’t radio, after all, the answer to the doubts about mass democracy expressed by the likes of Walter Lippmann? “If the future of our democracy depends upon the intelligence and cooperation of its citizens,” RCA President James G. Harbord wrote in 1929, “radio may contribute to its success more than any other single influence.”4

At the end of the 1920s, the nation’s optimism appeared boundless, and not only about radio. “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land,” Hoover said in the summer of 1928, accepting the Republican nomination. “We shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this earth.” American economic growth seemed unstoppable. “Everything indicates that business continues to make progress with production at a new high record,” the Wall Street Journal reported in July 1928. “And there seems to be nothing in sight to check the upward trend.” Stock market prices kept rising, at a time when stocks were no longer sold only to the wealthy. “Everybody Ought to be Rich,” argued one investor, in a magazine article in which he proposed that Americans without savings buy stocks on an installment plan. By 1929, a quarter of U.S. households owned stocks, compared to less than 1 percent a generation before. When Hoover was elected president in November of 1928, the stock market teetered at a record high; its closing average was three times what it had been in 1918 and twice what it had been in 1924.5

Hoover rode to his inauguration on a rainy Monday in March in a Pierce-Arrow motor car as swank as his top hat. His reign appeared to mark the final triumph of the campaign for efficiency and prosperity, a mass democracy made orderly by public-spirited businessmen and efficiency engineers. “The modern technical mind was for the first time at the head of government,” wrote pioneering New York Times reporter Anne O’Hare McCormick. “Almost with the air of giving genius its chance, we waited for the performance to begin.” But, privately, Hoover worried that the American people believed him “a sort of superman.”6

He set to work with his customary businessman’s briskness. He had a telephone installed on his desk in the Oval Office. He scheduled his appointments at eight-minute intervals. He began reorganizing the federal government. “Back to the mines,” he’d say, after a fifteen-minute lunch break. He worried about the runaway stock market but found himself unable to halt the bulls’ stampede. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had soared to 240 in 1928; in the summer of 1929, it rose past 380.7

On October 21, 1929, Hoover, along with five hundred distinguished guests, including the owners of most of America’s most powerful corporations, met at Henry Ford’s Edison Institute, in Dearborn, Michigan, to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the invention of the incandescent lightbulb. Light’s Golden Jubilee was the brainchild of Edward Bernays, whose publicity campaign in advance of the event including sending incandescent lightbulbs to the editors of all of the nation’s newspapers. On the night of the gala, electric companies all over the country shut off their electricity for one minute to honor Thomas Edison. Eighty-two-year-old Edison then re-created the moment when he’d first lit a lightbulb, while on NBC an announcer reported breathlessly: “Mr. Edison has the two wires in his hand. Now he is reaching up to the old lamp; now he is making the connection. It lights!”8

That night, news came by radio that shares on the New York Stock Exchange had begun to fall. It was as if a light, too brightly lit, had shattered.

I.

DARKNESS HAD ALREADY fallen on Europe, which was well into a depression by 1928, a consequence of the political settlement that had ended the First World War. Before the autumn of 1929, the United States had appeared beyond the reach of that shadow. But then, over three weeks, the Dow Jones fell from 326 to 198. Stocks lost nearly 40 percent of their value. At first, the market rallied; by March 1930, stocks traded on the Dow Jones had regained nearly 75 percent of the value they’d lost. Still, the economy teetered and then it tottered, a depression set in, and by late spring stock prices were once again plummeting.9

Hoover, master of emergencies, steered the country through the crash, but when the Depression began he did very little except to wait for a recovery and attempt to reassure a panicked public. He believed in charity, but he did not believe in government relief, arguing that if the United States were to provide it the nation would be “plunged into socialism and collectivism.”10

When Hoover did act, it was to sever the United States from Europe: he pulled up America’s last financial drawbridge by convincing Congress to pass a new, punitive trade bill, the 1930 Tariff Act. Other nations, retaliating, soon passed their own trade restrictions. Up came their drawbridges. World trade shrank by a quarter. U.S. imports fell. In 1929, the United States had imported $4.4 billion in foreign products; in 1930 imports declined to $3.1. Then U.S. exports fell. To protect American wheat farmers, the tariff on imported grain had been increased by almost 50 percent. But by 1931, American farmers found themselves able to sell only about 10 percent of their crops. Creditors seized farms and sold them off at auction. Foreign debtors, unable to sell their goods in the United States, proved unable to pay back their debts to American creditors.

Between 1929 and 1932, one in five American banks failed. The unemployment rate climbed from 9 percent in 1930, to 16 percent in 1931, to 23 percent in 1932, by which time nearly twelve million Americans—a number equal to the entire population of the state of New York—were out of work. By 1932, national income, $87.4 billion in 1929, had fallen to $41.7 billion. In many homes, family income fell to zero. One in four Americans suffered from want of food.11

Factories closed; farms were abandoned. Even the weather conspired to reduce Americans to want: a drought plagued the plains, sowing despair and reaping death. Soil turned to dust and blew away. Schools shut their doors, children grew thin, and even thinner, and babies died in their cradles. Farm families, displaced by debt and drought, wandered westward, carrying what they could in dust-covered jalopies. The experiment in democracy that had begun with American independence seemed on the very edge of defeat.

“At no time since the rise of political democracy have its tenets been so seriously challenged as they are today,” was the proclamation of the New Republic, introducing a series on the future of self-government. All over the world, democracies were collapsing under the weight of the masses. The Russian, Ottoman, and Austrian Empires had fallen apart, producing, by 1918, more than a dozen new states, many of which, like Lithuania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Poland, experimented with democracy but did not endure as democracies. The tally was bleak and, each year, bleaker, as one European nation after another turned to fascism or another form of authoritarianism.12

The long nineteenth-century’s movement toward constitutional government, the rule of law, representative assemblies, and the abdication of dictatorship—the application to modern life of eighteenth-century ideas about reason and debate, inquiry and equality—had come to a halt, and begun a reversal. Hardly a week passed without another learned commentator declaring the experiment a failure. “Epitaphs for democracy are the fashion of the day,” the legal scholar Felix Frankfurter remarked in 1930. “In 1931, men and women all over the world were seriously contemplating and frankly discussing the possibility that the Western system of Society might break down and cease to work,” the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee observed that fateful year. “Representative democracy seems to have ended in a cul-de-sac,” wrote the political theorist Harold Laski in 1932.13

The last peace had created the conditions for the next war. Out of want came fear, out of fear came fury. By 1930, more than three million Germans were unemployed and Nazi Party membership had doubled. Adolf Hitler, as addled as he was ruthless, came to power in 1933, invaded the Rhineland in 1936, Poland in 1939. The bells of history tolled a tragedy of ages. Japan, whose expansion had been prohibited by the League of Nations, invaded Manchuria in 1931 and Shanghai in 1937. Italy’s dictator Benito Mussolini, Il Duce, thirsting for glory and for the triumphs and trophies of war, invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Tyrants ruled with the terror of lies, led by the Reich’s Ministry of Propaganda. Mussolini predicted: “The liberal state is destined to perish.”14

Much appeared to rest on the fate of the United States and its search for a new way, a third way, between laissez-faire capitalism and a state-run economy. “It has fallen to us to live in one of those conjunctures of human affairs which mark a crisis in the habits, the customs, the routine, the inherited method and the traditional ideas of mankind,” Walter Lippmann announced in a speech in Berkeley in 1933. “The old relationships among the great masses of the people of the earth have disappeared,” he said. “The fixed points by which our fathers steered the ship of state have vanished.”15

Was the ship of state lost at sea? “We are still, all of us, more or less, primitive men—as lynchings illustrate dramatically and Fascism systematically,” the historian Charles Beard wrote bitterly in 1934. The great masses of the people had insisted on their right to rule, but their rule, it turned out, was dangerous, so easily were they deceived by propaganda. “The liberal culture of modernity is quite unable to give guidance and direction to a confused generation which faces the disintegration of a social system and the task of building a new one,” the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr wrote that year, in the aptly titled Reflections on the End of an Era.16

One set of political arrangements had come to an end; it remained to be seen what set of arrangements would replace them. After the stock market crash, voters rejected both Hoover’s leadership and that of his party. In the 1930 midterm elections, Republicans lost fifty-two seats in the House. Advisers urged Hoover to address the nation in weekly ten-minute radio broadcasts, to offer comfort and solace and direction; he refused.

Few voices were less well suited to the new medium. Hoover spoke on the radio ninety-five times during his presidency but during the handful of broadcasts in which he did more than issue a strained greeting, he read from a script in a dreadful monotone. “No one with a spark of human sympathy can contemplate unmoved the possibilities of suffering that can crush many of our unfortunate fellow Americans if we shall fail them,” he said once, reading a well-written and even stirring speech but sounding like an overworked principal at a middle-school graduation listlessly announcing the names of graduating students from a lectern in a gray-green auditorium.17

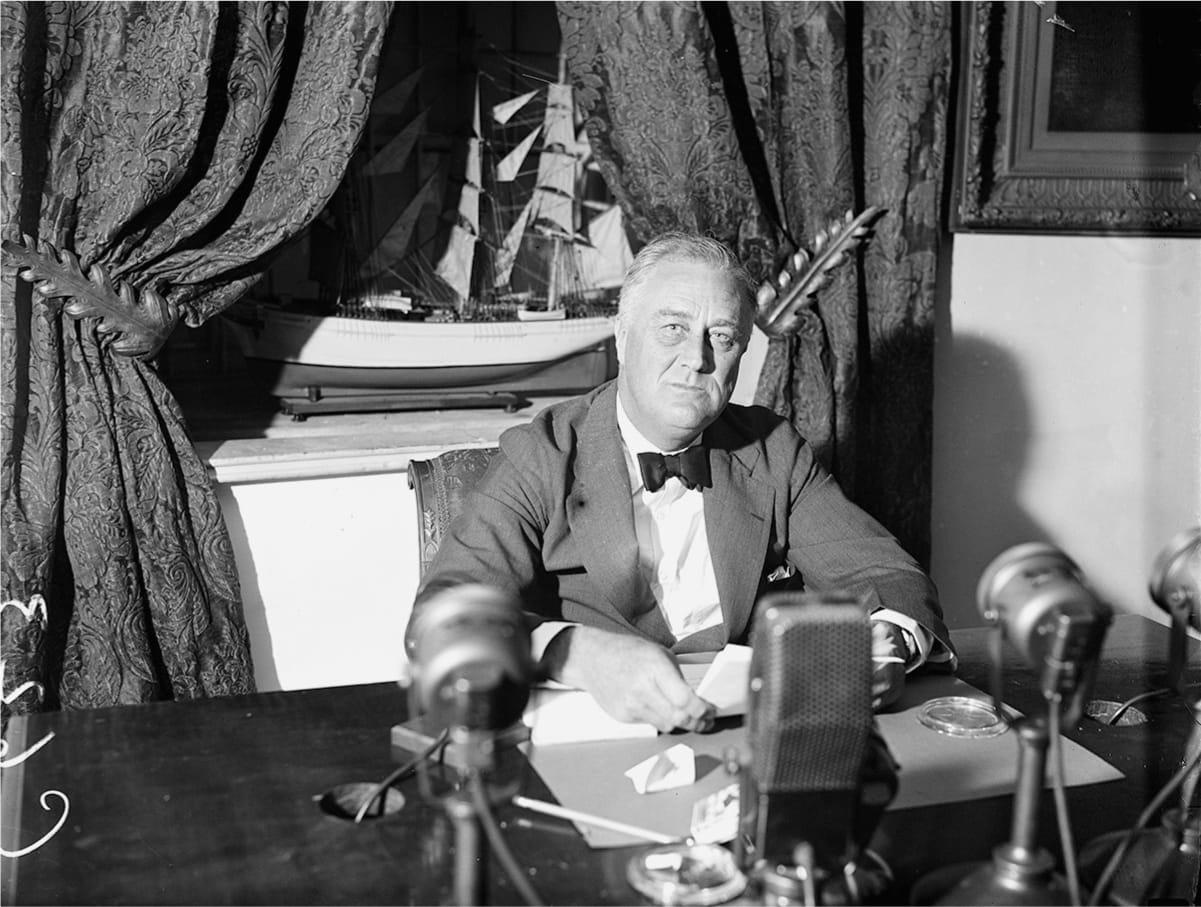

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was untroubled by any such awkwardness. He wore a wide-brimmed hat and wireless round eyeglasses. His daintiness, a certain fussiness of person, earned him the nickname “Feather Duster Roosevelt.” But if he had a patrician style, he spoke on the radio with an easy intimacy and a ready charm, coming across as knowledgeable, patient, kind-hearted, and firm of purpose. He spoke, he liked to say, with the “quiet of common sense and friendliness.”18 Hoover, a man of humble origins, dedicated to public service, would come to be seen as having turned his back on the suffering of the poorest of Americans. Roosevelt, raised as an aristocrat, would be remembered as their champion.

Born in Hyde Park in 1882, Roosevelt as a young man had much admired his distant cousin, lion-hunting Theodore Roosevelt, and even emulated him. “Delighted!” he would say, and “Bully!” He was elected to the state senate in 1910, at the age of twenty-eight, as a Democrat. Three years later, Wilson appointed him assistant secretary of the navy. By 1920, he’d risen to the rank of presidential running mate. But the next year, his political career appeared to be over when, at the age of thirty-nine, he contracted polio and lost the use of both of his legs. Confined to a wheelchair in private, he disguised his condition from the public by using leg braces and a cane, walking only with great pain. It was his paralysis, his wife, Eleanor, said, that taught Roosevelt “what suffering meant.”19

His acquaintance with anguish changed his voice: it made it warmer. Hoover understood the importance of radio; Roosevelt knew how to use it. In 1928, delivering a nominating address at the Democratic National Convention, the first convention broadcast on the air, Roosevelt felt—and sounded as though—he was addressing not the audience in Madison Square Garden but Americans across the country. He’d then honed his skills as a radio broadcaster as governor of New York, delivering regular “reports to the people” from WOKO in Albany. The state’s newspapers were predominantly Republican; to bypass them, Roosevelt delivered a monthly radio address, reaching voters directly.

In 1932, he stumped for the Democratic nomination on behalf of a new brand of liberalism that borrowed as much from Bryan’s populism as from Wilson’s Progressivism. “The history of the last half century is . . . in large measure a history of a group of financial Titans,” Roosevelt said in a rally in San Francisco. But “the day of the great promoter or the financial Titan, to whom we granted anything if only he would build, or develop, is over.”20

When Roosevelt, at the governor’s mansion in Albany, heard on the radio that he’d been nominated at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, he called the hall and said that he was on his way. While delegates—along with an expectant radio audience—waited, Roosevelt flew to Chicago, his plane refueling in Cleveland. No presidential nominee had ever shown up to accept the nomination in person, but the times were strange, Roosevelt said, and they called for change: “Let it from now on be the task of our party to break foolish traditions.” In his rousing acceptance speech, broadcast live, he promised Americans a “new deal.”

“I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people,” he told the roaring crowd in Chicago Stadium, straw hats waving. “Let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order of competence and of courage. This is more than a political campaign; it is a call to arms. Give me your help, not to win votes alone, but to win in this crusade to restore America to its own people.”21

Republicans often said, as they’d said about William Jennings Bryan, that while listening to Roosevelt, they found themselves agreeing with him, even when they didn’t. “All that man has to do is speak on the radio, and the sound of his voice, his sincerity, and the manner of his delivery, just melts me,” one said. Hoover compared Roosevelt to Bryan not only in style but in substance, describing the New Deal as nothing more than “Bryanism under new words and methods.” That wasn’t really true, as a matter of politics and constituencies, but there were undeniable similarities. The New Deal “is as old as Christian ethics, for basically its ethics are the same,” Roosevelt liked to say. “It recognizes that man is indeed his brother’s keeper, insists that the laborer is worthy of his hire, demands that justice shall rule the mighty as well as the weak.”22

Still, much was new in Roosevelt’s presidency, beginning with his campaign. The stump speeches he delivered on stages all over the country were the first presidential campaign speeches recorded on film and screened in movie theaters as newsreels. After accepting the nomination, he began delivering nationwide radio addresses from the governor’s mansion, each speech more disarming than the last.

“I hope during this campaign to use the radio frequently, to speak to you about important things that concern us all,” he told his audience. “I want you to hear me tonight as I sit here in my own home, away from the excitement of the campaign, and with only a few of the family, and a few personal friends present.” Most Americans had only ever heard national political candidates shouting, trying to project their voices across a banquet hall or a football field. Hearing Roosevelt speak quietly and calmly, as if he were sitting across the kitchen table, having a reasonable argument with you, earned him Americans’ dedicated affection. “It was a God-given gift,” his wife said. He “could talk to people so that they felt he was talking to them individually.”23

In November, Roosevelt trounced Hoover, beating him 472 to 59 in the Electoral College and winning forty-two out of forty-eight states. The simplest explanation was that the public blamed Hoover for the Depression. But there was more to the rout. FDR’s election also ushered in a new party system, as the Democratic and Republican Parties rearranged themselves around what came to be called the New Deal coalition, which brought together blue-collar workers, southern farmers, racial minorities, liberal intellectuals, and even industrialists and, still more strangely, women. With roots in nineteenth-century populism and early twentieth-century Progressivism, FDR’s ascension marked the rise of modern liberalism.

But FDR’s election and the New Deal coalition also marked a turning point in another way, in the character and ambition of his wife, the indomitable Eleanor Roosevelt. Born in New York in 1884, she’d been orphaned as a child. She married FDR, her fifth cousin, in 1905; they had six children. Nine years into their marriage, Franklin began an affair with Eleanor’s social secretary, and when Eleanor found out, he refused to agree to a divorce, fearing it would end his career in politics. Eleanor turned her energies outward. During the war, she worked on international relief, and, after Franklin was struck with polio in 1921, she began speaking in public, heeding a call that brought so many women to the stage for the first time: she was sent to appear in her husband’s stead.

Eleanor Roosevelt became a major figure in American politics in her own right just at a time when women were entering political parties. It was out of frustration with the major parties’ evasions on equal rights that Alice Paul had founded the National Woman’s Party in 1916.24 Fearful that soon-to-be enfranchised female voters would form their own voting bloc, the Democratic and Republican Parties had then begun recruiting women. The Democratic National Committee (DNC) formed a Women’s Division in 1917, and the next year, the Republicans did the same, the party chairman pledging “to check any tendency toward the formation of a separate women’s party.” After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, Carrie Chapman Catt, head of the League of Women Voters, steered women away from the National Woman’s Party and urged them to join one of the two major parties, advising, “The only way to get things in this country is to find them on the inside of the political party.” Few women answered that call more vigorously than Eleanor Roosevelt, who became a leader of the Women’s Division of the New York State Democratic Party while her husband campaigned and served as governor of the state. By 1928, she was one of the two most powerful women in American politics, head of the Women’s Division of the DNC.25

Eleanor Roosevelt, lean and rangy, wore floral dresses and tucked flowers in the brim of floppy hats perched on top of her wavy hair, but she had a spine as stiff as the steel girder of a skyscraper. She hadn’t wanted her husband to run for president, mainly because she had so little interest in becoming First Lady, a role that, with rare exception, had meant serving as a hostess at state dinners while demurring to the men when the talk turned to affairs of state. She made that role her own, deciding to use her position to advance causes she cared about: women’s rights and civil rights. She went on a national tour, wrote a regular newspaper column, and in December 1932 began delivering a series of thirteen nationwide radio broadcasts. While not a naturally gifted speaker, she earned an extraordinarily loyal following and became a radio celebrity. From the White House, she eventually delivered some three hundred broadcasts, about as many as FDR. Perhaps most significantly, she reached rural women, who had few ties to the national culture except by radio. “As I have talked to you,” she told her audience, “I have tried to realize that way up in the high mountain farms of Tennessee, on lonely ranches in the Texas plains, in thousands and thousands of homes, there are women listening to what I say.”26

Eleanor Roosevelt not only brought women into politics and reinvented the role of the First Lady, she also tilted the Democratic Party toward the interests of women, a dramatic reversal. The GOP had courted the support of women since its founding in 1854; the Democratic Party had turned women away and dismissed their concerns. With Eleanor Roosevelt, that began to change. During years when women were choosing a party for the first time, more of them became Democrats than Republicans. Between 1934 and 1938, while the numbers of Republican women grew by 400 percent, the numbers of Democratic women grew by 700 percent.27

In January 1933, she announced that she intended to write a book. “Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who has been one of the most active women in the country since her husband was elected President, is going to write a 40,000-word book between now and the March inauguration,” the Boston Globe reported, incredulous. “Every word will be written by Mrs. Roosevelt herself.”28

It’s Up to the Women came out that spring. Only women could lead the nation out of the Depression, she argued—by frugality, hard work, common sense, and civic participation. The “really new deal for the people,” Eleanor Roosevelt always said, had to do with the awakening of women.29

II.

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT rode to the Capitol in the backseat of a convertible, seated next to Hoover, a blanket spread across their laps; after that cold day, March 4, 1933, the two men never met again. “This great nation will endure, as it has endured,” FDR said in his inaugural address, attempting to reassure a troubled nation as he braced himself against the podium, bearing the weight of his body in great pain. “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror.”30

At the time, many Americans believed that the economic crisis was so dire as to require the new president to assume the powers of a dictator in order to avoid congressional obstructionism. “The situation is critical, Franklin,” Walter Lippmann wrote to Roosevelt. “You may have no alternative but to assume dictatorial powers.”31 Gabriel Over the White House, a Hollywood film coproduced by William Randolph Hearst and released to coincide with the March 1933 inauguration, depicted a fictional but decidedly Rooseveltian president who, threatened with impeachment, bursts into a joint session of Congress.

“You have wasted precious days, and weeks and years in futile discussion,” he tells the assembled representatives. “We need action, immediate and effective action!” He declares a national emergency, adjourns Congress, and takes control of the government.

“Mr. President, this is dictatorship!” cries one senator.

“Words do not frighten me!” answers the president.32

“Do We Need a Dictator?” The Nation asked, the month the film was released, and answered, “Emphatically not!”33

Meanwhile, the world watched Germany. For a long time, American reporters had underestimated Hitler. Crackerjack world-famous journalist Dorothy Thompson interviewed Hitler in 1930 and dismissed him. “He is inconsequent and voluble, ill-poised, insecure,” she wrote. “He is the very prototype of the Little Man.” By 1933, what that little man intended was growing clearer, and Thompson would go on to do more to raise American awareness of the persecution of American Jews than almost any other writer. Nazism she would describe as “a repudiation of the whole past of Western man,” a “complete break with Reason, with Humanism, and with the Christian ethics that are the basis of liberalism and democracy.” Thrown out of Germany for her criticism of the Nazi government, she had her expulsion order framed and hung it on her wall.34

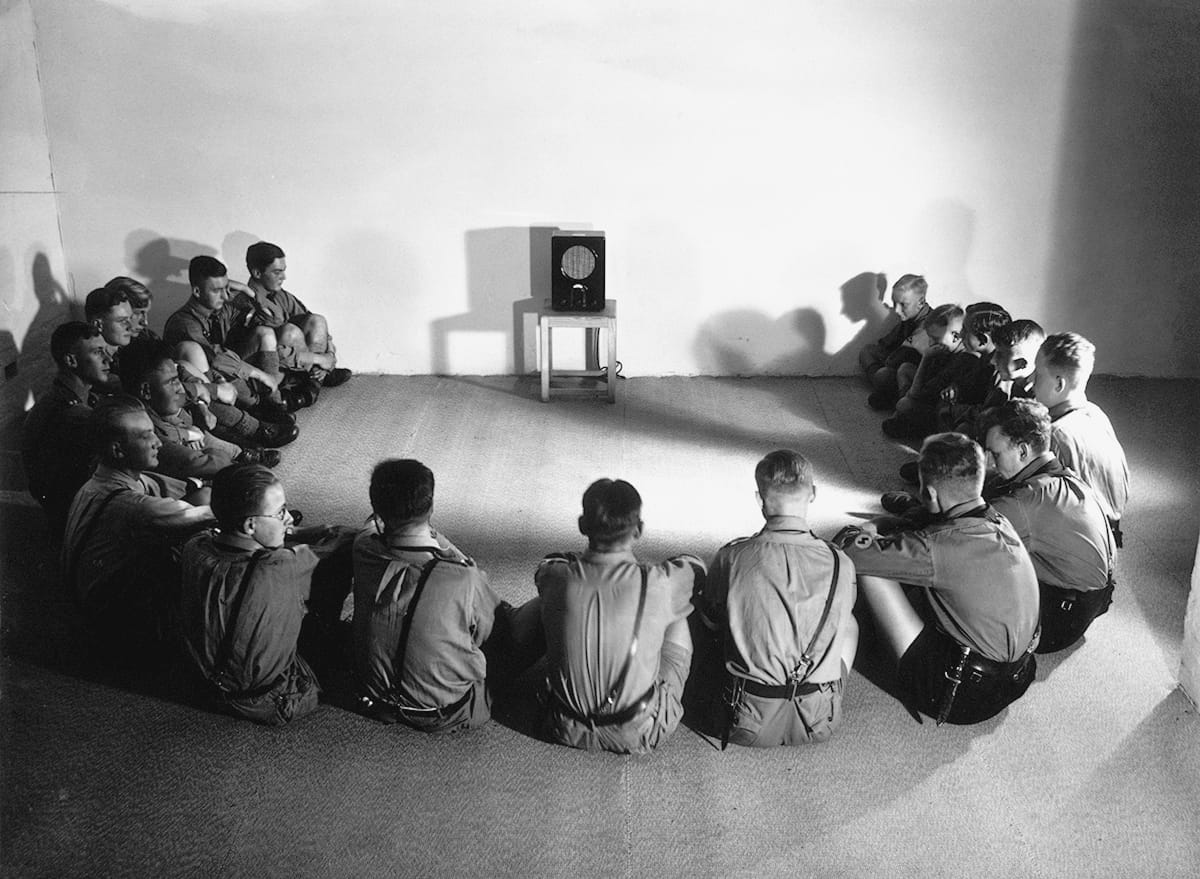

On January 30, 1933, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. In parliamentary elections held on March 5—the last vote the German people would be allowed for a dozen years—the Nazi Party narrowly failed to win a majority. Six days later, Hitler told his cabinet of his intention to establish a Ministry of Propaganda. Joseph Goebbels, appointed as its head on March 13, reported in his diary four days later that “broadcasting is now totally in the hands of the state.” Having seized control of the airwaves, Hitler seized control of what remained of the government. On March 23, he addressed the German legislature, the Reichstag, its doors barred. Speaking beneath a giant flag of a swastika, Hitler asked the Reichstag to pass the Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich, essentially abolishing its own authority and granting to Hitler the right to make law. The government then outlawed all parties but the Nazi Party. By October, Germany had withdrawn from the League of Nations. Jewish refugees trying to flee to the United States found themselves blocked by a grotesque paradox: Nazi law mandated that no Jew could take more than four dollars out of the country; American immigration laws banned anyone “likely to become a public charge.”35

To many people around the world, Roosevelt was the hope of democratic government, and his New Deal the last best hope for a liberal order. “You have made yourself the Trustee for those in every country who seek to mend the evils of our condition by reasoned experiment within the framework of the existing social system,” John Maynard Keynes wrote to the president. “If you fail, rational change will be gravely prejudiced throughout the world, leaving orthodoxy and revolution to fight it out. But if you succeed, new and bolder methods will be tried everywhere, and we may date the first chapter of a new economic era from your accession to office.”36

Keynes’s expectations were nothing compared to those of ordinary Americans. In FDR’s first seven days in office, he received more than 450,000 letters and telegrams from the public. By no means was all the mail favorable, but FDR loved it all the same; it taught him what people were thinking. He made a point of reading a selection daily.37

People had been writing to presidents since George Washington was inaugurated, but, by volume, no other presidency had come anywhere close.38 (Hoover received eight hundred letters a day; FDR eight thousand.) The rise of “fan mail”—the expression wasn’t used before the 1920s—was a product of radio; radio stations and networks encouraged listeners to write to them and used their responses to refine their programming. In the 1930s, the National Broadcasting Corporation received ten million letters a year (not counting mail sent to its affiliates, sponsors, and stations). Like radio stations, the White House began reading, sorting, and counting its mail. Eleanor Roosevelt received three hundred thousand letters in 1933 alone. The mail came pouring down on Congress next. By 1935, the Senate received forty thousand letters a day. By the end of the 1930s, voters were writing letters to Supreme Court justices.39

If FDR listened carefully to ordinary Americans by reading voter mail, he also assembled an altogether unordinary team of advisers. Elected during a national emergency, Roosevelt assembled a “brain trust” that included Frances Perkins as his secretary of labor, the first female member of a presidential cabinet. How he both relied on his brain trust and put his own touch on their advice is suggested in how he handled radio scripts. “We are trying to construct a more inclusive society,” Perkins wrote for him, in a draft of a speech he intended to give over the radio. When he delivered that speech, he said, instead: “We are going to make a country in which no one is left out.”40

He began by shutting down the nation’s banks. The rate of bank and business failures reached the highest point in history. Millions of Americans had lost every penny. The New York Stock Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade had suspended trading, and the governors of thirty-two states had already shut their banks to prevent total collapse. In states where banks remained open, depositors could withdraw no more than 5 percent of their savings. Roosevelt shut the banks to prevent still further collapse. On March 5, the day after he was inaugurated, he asked Congress to declare a four-day bank holiday. Under the terms of the Emergency Banking Act, banks would be opened once they’d been found to be sound. On March 12, FDR spoke on the radio in what radio executives took to calling a “fireside chat”—the first of more than three hundred. Explaining his banking plan, he offered reassurance. “I want to tell you what has been done in the last few days, and why it was done, and what the next steps are going to be,” he said. He offered a lesson: “When you deposit money in a bank, the bank does not put the money into a safe deposit vault.” He asked for Americans’ confidence. “I can assure you that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.”41

Roosevelt’s ability to take such measures was greatly strengthened by the popular endorsement he was able to secure by way of the radio. People said that in the summer you could walk down a city street, past the open windows of houses and cars, and not miss a word of a fireside chat, since everyone was tuned in. “We have become neighbors in a new and true sense,” FDR said, describing what coast-to-coast broadcasting had wrought. He’d listen to recordings of his addresses after he’d given them, to make improvements for the next time. He worked and reworked drafts so that, by the time he sat down at the microphone, he’d committed his speech to memory. Before every address, he took a nap to rest his voice. He spoke at an unusual speed—much slower than most radio announcers—and with an everyday vocabulary. Roosevelt’s mastery of the airwaves resulted from his talent for and dedication to the form. But he also worked with his FCC chairman to block newspaper publishers from owning radio stations, thereby defeating William Randolph Hearst’s attempt to expand his empire to radio and denying one of his key political opponents a place on the dial.42

Roosevelt was also dogged in his work with Congress. He met with legislators every day of the first hundred days of his administration and proposed—and Congress passed—a flurry of legislation intended to stabilize and reform the banking system, regulate the economy through government planning, provide economic relief through public assistance programs, reduce unemployment through a public works program, and allow farmers to keep their farms by securing better resources to rural Americans. “As a Nation,” Perkins said, “we are recognizing that programs long thought of as merely labor welfare, such as shorter hours, higher wages, and a voice in the terms and conditions of work, are really essential economic factors for recovery.”43

Roosevelt’s agenda rested on the idea that government planning was necessary for the recovery and, to some degree, on the Keynesian belief that the remedy for depression was government spending, an agenda he adopted even before the publication, in 1936, of Keynes’s Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. FDR’s banking reforms included the Emergency Banking Act; the Glass-Steagall Act, which established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; and creation of the Securities Exchange Commission. The Public Works Administration oversaw tens of thousands of infrastructure projects, from repairing roads to building dams, as well as cultural and arts initiatives, including the Federal Writers’ Project and the Federal Theatre Project. The Agricultural Adjustment Act addressed the problems faced by the more than one in three Americans who worked on farms.

FDR had dealt with many of these problems as a governor of New York. During the 1920s, more than three hundred thousand farms in New York were abandoned. Like many reformers associated with what came to be called the New Conservation, Roosevelt believed the greatest disparity of wealth in the United States was that between urban and rural Americans. Farming communities had worse schools, inadequate health care, and higher taxes. Poor land makes poor people, he believed. “I want to build up the land as, in part at least, an insurance against future depressions,” Roo sevelt said in 1931, the year he established the New York Power Authority. The Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Farm Security Administration, and other agricultural initiatives extended a better and fairer distribution of resources like land, power, and water to a national scale. Much of the greatest distress among rural Americans was felt in the Cotton Belt, a part of the country that FDR called “the Nation’s No. 1 economic problem—the Nation’s problem, not merely the South’s.”44

Reform, relief, and recovery were the three legs of FDR’s agenda. Early results were promising, but the Depression continued. “When any prognosticator foretells the outcome of the acts of the New Deal, he is more or less of a guesser in this vale of tears,” Charles Beard wrote in 1934. “What is an ‘outcome’ or a ‘result’? Is it an outcome or result in 1936, 1950, or the year 2000?” The New Deal had barely begun but voters approved; Democrats fared well in the midterm elections, leading Roosevelt to push further. “Boys, this is our hour,” his adviser Harry Hopkins said. “We’ve got to get everything we want—a works program, social security, wages and hours, everything—now or never.” Or, not quite everything. In 1934 Isaac Rubinow, who’d fought for national health insurance during the 1910s, published The Quest for Security and urged FDR to include health care in the New Deal. But by now the American Medical Association, which had favored Rubinow’s proposal before the war, had switched sides. Government meddling in medicine, the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association said, came down to a question of “Americanism versus sovietism.”45

Even without universal health care, the scope of the New Deal was remarkable. In 1935, Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act, granting to workers the right to organize, and established the Works Project Administration, to hire millions of people who built roads and schools and hospitals, as well as artists and writers. Meanwhile, Perkins drafted the Social Security Act, passed by Congress later that year. It established pensions, federal government assistance for fatherless families, and unemployment relief.

Still, the reforms had limits. The liberal policymakers who created the welfare state in the 1930s were averse to relief as such. “The Federal Government,” FDR said, “has no intention or desire to force upon the country or the unemployed themselves a system of relief which is repugnant to American ideals of individual self-reliance.” And they were also squeamish about direct taxes, an aversion most manifest in the decision to fund the Social Security Act with an indirect tax on payroll. This allowed New Dealers to distinguish between old-age and unemployment programs (cast as insurance, paid for by annuities created from payroll taxes acting as insurance premiums) and poverty programs, like Aid to Dependent Children (cast as welfare). One legacy of this distinction was that Americans hostile to welfare seldom saw Social Security as part of it.46

HUNGER, ACHING WANT, was the great scourge of the 1930s. The land itself had grown barren. “When we picked the cotton, we could see the tracks where we plowed two or three months before,” Willis Magby recalled of the drought in Beaton, Arkansas, west of Little Rock. “It hadn’t rained enough to wash away the tracks.” Magby was thirteen years old in 1933 when his parents piled him and his six younger siblings into an old Model T and drove from Arkansas to south Texas. The family slept on the ground at the side of the road, pawning the last of their scant belongings along the way to buy gasoline. Once in Texas, for weeks at a time they ate nothing but cornmeal soaked in rainwater. One winter, they lived off rabbits. Only in 1936, when Magby’s father was able to get a government loan to buy a team of mules and plant a crop, did things start to look up.47

Nearly five in ten white families and nine in ten black families endured poverty at some point during the Depression. Black families fared worse, not only because more fell into poverty but also because the roads out of poverty were often closed to them: New Deal loan, relief, and insurance programs often specifically excluded black people.

Louise Norton, born in Grenada in 1900, met her husband, Earl Little, a Baptist minister, at a United Negro Improvement Association meeting in Philadelphia in 1917. In 1925, when the Littles were living in Omaha and Louise was pregnant with her son Malcolm and home alone with her three young children, mounted Klansmen came to their house, threatening to lynch the Reverend Little. Finding him not at home, they shattered all the windows. Driven out of Omaha, the Littles eventually settled in Lansing, Michigan, where still more vigilantes burned their home to the ground. In 1931, the Reverend Little was killed by a streetcar; much evidence suggests that his death was not an accident. After Little’s death, the insurance company denied his widow his life insurance. For a while, Louise and the children lived on dandelions. In 1939, after giving birth to her eighth child, Louise Little was committed to an insane asylum at the Kalamazoo State Hospital, where she remained for the next quarter century. Her son Malcolm was moved into foster care and then a juvenile home, and eventually lived in Boston with his half-sister. He would one day change his name to Malcolm X.48

Yet if hard times widened some divisions, they narrowed others. People who were doing fairly well one day could be reduced to anguished indigence the next. Then, too, it was impossible not to bear witness. Massive unemployment had this side effect: people had more time on their hands to listen to the radio. One third of all movie theaters closed, but, between 1935 and 1941 alone, nearly three hundred new radio stations opened. By the end of the decade, the United States had more than half the world’s radio sets, at a time when radio broadcasts chronicled and dramatized the suffering of the poor to a national audience, both in reporting and in the emerging genre of the radio drama, with a new vocabulary of sound effects, immediate and visceral.49

Much of the work of chronicling the suffering of those years was done by playwrights, photographers, historians, and writers, hired by the government under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration. Working for the Federal Writers Project and the Federal Theatre Project, including its Radio Division, they documented the lives of the ordinary, the rural, and especially the poor, in interviews, photographs, films, paintings, and radio broadcasts. Its critics called it the “Whistle, Piss, and Argue” department, but at a time when one in four people in publishing were out of work, the WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project provided employment to more than seven thousand writers, including Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, John Cheever, and Richard Wright.50 But it was radio that brought the sounds of suffering into the homes, even, of people who were still getting by, and even the rarer few who were prospering. James Truslow Adams’s The Epic of America (1931), featuring the lives of the humblest Americans, was dramatized by the Federal Theatre of the Air. “There is no lack of excellent one-volume narrative histories of the United States, in which the political, military, diplomatic, social, and economic strands have been skillfully interwoven,” Adams had written in his book’s preface. The Epic of America was not that kind of book. Instead, Adams had tried “to discover for himself and others how the ordinary American, under which category most of us come, has become what he is to-day in outlook, character, and opinion.” Adams, who’d wanted to call his book “The American Dream”—a term he coined—celebrated the struggles of the common man in language that would stir leaders of later generations, from Martin Luther King Jr. to Barack Obama.51

Much the same spirit pervaded the documentary projects of the WPA and of other New Deal programs, including the photography of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, undertaken on behalf of the Farm Security Administration. The head of the FSA’s photography program required his staff to read Charles Beard’s History of the United States—an eloquent and strident social history that championed the struggles of the poor. The WPA’s folklore director, Benjamin Botkin, wanted to turn “the streets, the stockyards, and the hiring halls into literature.” From more than ten thousand interviews, the Writers’ Project produced some eight hundred books, including A Treasury of American Folklore, and a volume called These Are Our Lives, which included excerpts from more than two thousand interviews with Americans once held as slaves.52

If the Depression, and alike the New Deal, created a new compassion for the poor, it also produced a generation of politicians committed to the idea that government can relieve suffering and regulate the economy. In 1937, lanky former Texas schoolteacher Lyndon Baines Johnson was elected to Congress, where he worked to obtain federal funds for his district for projects like the construction of dams to improve farmland. When LBJ was a boy, his father had lost his farm. He’d grown up dirt-poor. Six foot three, with long ears and no discernible end to his energy, Johnson had hitchhiked to a state teachers college and, after graduating, taught at an elementary school in Cotulla, Texas, sixty miles north of the border. The students were Mexican American; there was no lunch break, because the children had no lunch to eat. Johnson organized a debating team and taught them how to fight for their ideas. When he ran for Congress, he printed signs that read “Franklin D. and Lyndon B.” Like his hero, LBJ embraced the radio, campaigning on radio stations like KNOW in Austin and KTSA in San Antonio and once—in an act of inspired populist appeal—broadcasting from a barbershop.53

In Congress, Johnson regularly worked sixteen- and eighteen-hour days. He fought for the Bankhead-Jones Act in 1937, to help tenant farmers buy land. He campaigned for more improvements, too, and fought to have rural electrification placed in the hands not of power companies but farmers’ cooperatives. He later said, “We built six dams on our river. We brought the floods under control. We provided our people with cheap power. . . . That all resulted from the power of the government to bring the greatest good to the greatest number.”54

What was that number? New methods and new sources of information made it possible to measure the impact of the New Deal, as the age of quantification yielded to the age of statistics. In 1912, an Italian statistician named Corrado Gini, Chair of Statistics at the University of Cagliari, devised what came to be called the Gini index, which measures economic inequality on a scale from zero to one.55 If all the income in the world were earned by one person and everyone else earned nothing, the world would have a Gini index of one. If everyone in the world earned exactly the same income, the world would have a Gini index of zero. In between zero and one, the higher the number, the greater the gap between the rich and the poor. Using federal income tax returns, filed beginning in 1913, it’s possible to calculate the Gini index for the United States. In 1928, under the tax scheme endorsed by Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, the top 1 percent of American families earned 24 percent of all income. By 1938, after the reforms of the New Deal, the top 1 percent of American families earned only 16 percent of all income.56 It was just this kind of redistribution, at a time when Americans were flirting with fascism, that alarmed conservatives. The sort of economic planning that Gini himself advocated was closely associated with nondemocratic states. In 1925, four years after he wrote an essay called “The Measurement of Inequality,” Gini signed the “Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals.” His work as a scientist was so closely tied to the fascist state that after the regime fell he was tried for being “an apologist for Fascism.”57

Americans, too, began hunting for apologists for fascism, and, especially, for communism, fishing for American subversives. During the Depression, some seventy-five thousand Americans had joined the Communist Party. In May 1938, Martin Dies Jr., a beefy thirty-seven-year-old conservative Democrat from Texas and a fly in Lyndon Johnson’s eye, convened the House Un-American Activities Committee to investigate suspected communists and communist organizations. Dorothy Thompson railed against the committee: “little men—nasty little men—who run around pinning tags on people. This one is a ‘Red’; this one is a ‘Jew.’ Since when has America become a race of snoopers?” But the snooping had been going on for a while. Much of Dies’s work continued the campaign of harassment and intimidation waged by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which had for years been conducting surveillance on hundreds of black artists and writers, infiltrating their organizations and, in particular, harassing writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance. As Richard Wright wrote, in “The FB Eye Blues,” “Everywhere I look, Lord / I see FB eyes . . . I’m getting sick and tired of gover’ment spies.”58

In congressional hearings, Dies directed his ire at writers and artists employed by the WPA, attempting to demonstrate that their work—their plays and poems and folklore collections and documentary photographs—contained hidden communist messages. In one notorious encounter, Dies called Hallie Flanagan, the director of the Federal Theatre Project. Flanagan, born in South Dakota, was an accomplished playwright and distinguished professor of drama at Vassar, where she’d founded its Experimental Theatre. When she appeared before Dies’s committee, in December 1938, Alabama congressman Joseph Starnes asked her about a scholarly article she’d written in which she used the phrase “Marlowesque madness.” (The Theatre Project had funded productions of Marlowe’s Tragical History of Dr. Faustus in New Orleans, Boston, Detroit, Atlanta and, directed by Orson Welles, in New York.)

“You are quoting from this Marlowe,” Starnes said. “Is he a Communist?”

Spectators roared with laughter, but Flanagan answered solemnly.

“I was quoting from Christopher Marlowe.”

“Tell us who Marlowe is,” Starnes pressed.

“Put in the record,” Flanagan said wearily, “that he was the greatest dramatist in the period of Shakespeare.”59

Flanagan was right to be worried. The Federal Theatre Project had staged more than eight hundred plays. Dies’s committee objected to only a handful—including Woman of Destiny, about a female president, and Machine Age, about mass production—but months after Flanagan’s testimony, funding for both the Federal Theatre Project and the Federal Writers’ Project stopped, Congress having struck a bargain with Dies little better than the deal Faustus struck with Lucifer.

III.

FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT’S PRESIDENCY marked the beginning of a “new deal order,” an American-led, rights-based liberalism that Lyndon Johnson would carry into the 1960s. In the nineteenth century, “liberalism” meant advocacy of laissez-faire capitalism. The meaning of the term changed during the Progressive Era, when self-styled Progressives, borrowing from Populism, began attempting to reform laissez-faire capitalism by using the tools of collective action and appeals to the people adopted by Populists; in the 1930s, these efforts came together as New Deal liberalism.60

All that while, a new kind of conservatism was growing, too. It consisted not only of businessmen who opposed government regulation of the economy but also of Americans, chiefly rural Americans, who objected to government interference in their lives. These two strands of conservatism were largely separate in the 1930s, but they’d already begun moving closer together, especially in their animosity toward the paternalism of liberalism.61

Not long into FDR’s first term, businessmen who had supported him began to question his agenda. The du Pont brothers—Pierre, Irénée, and Lammot—belonged to a family that had made its fortune in paints, plastics, and munitions. In 1934, Merchants of Death, a bestseller that blamed arms manufacturers for the First World War, led to a congressional investigation, headed by North Dakota Republican senator Gerald P. Nye, who’d flouted his party to support Roosevelt. At the time, concern about munitions manufacturers crossed party lines, and so did a related concern about guns.

Americans had always owned guns, but states had also always regulated their manufacture, ownership, and storage. Carrying concealed weapons was prohibited by laws in Kentucky and Louisiana (1813), Indiana (1820), Tennessee and Virginia (1838), Alabama (1839), and Ohio (1859). Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma passed similar laws. The “mission of the concealed deadly weapon is murder,” said one governor of Texas. “To check it is the duty of every self-respecting, law abiding man.” Different rules obtained in the city and in the country. In western cities and towns, sheriffs routinely collected the guns of visitors, like checked baggage. In 1873, a sign in Wichita, Kansas read: “Leave Your Revolvers at Police Headquarters, and Get a Check.” On the road into Dodge, a billboard read, “The Carrying of Firearms Strictly Prohibited.” The shootout at the O.K. Corral, in Tombstone, Arizona, happened when Wyatt Earp confronted a man violating an 1879 city ordinance by failing to leave his gun at the sheriff’s office.62

The National Rifle Association had been founded in 1871 by a former reporter from the New York Times, as a sporting and hunting association; most of its business consisted of sponsoring target-shooting competitions. Not only did the NRA not oppose firearms regulation, it supported and even sponsored it. In the 1920s and 1930s—the era of Nye’s Munitions Committee—the NRA endorsed gun control legislation, lobbying for new state laws in the 1920s and 1930s. Concern about urban crime led to federal legislation in the 1930s. Public-safety-minded firearms regulation was uncontroversial. The NRA supported both the uniform 1934 National Firearms Act—the first federal gun control legislation—and the 1938 Federal Firearms Act, which together prohibitively taxed the private ownership of automatic weapons (“machine guns”), mandated licensing for handgun dealers, introduced waiting periods for handgun buyers, required permits for anyone wishing to carry a concealed weapon, and created a licensing system for dealers. In 1939, in a unanimous decision in U.S. v. Miller, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld these measures after FDR’s solicitor general, Robert H. Jackson, argued that the Second Amendment is “restricted to the keeping and bearing of arms by the people collectively for their common defense and security.” The text of the amendment, Jackson argued, makes clear that the right “is not one which may be utilized for private purposes but only one which exists where the arms are borne in the militia or some other military organization provided for by law and intended for the protection of the state.”63

The 1934 and 1938 firearms legislation enjoyed bipartisan support, but the regulation of munitions manufacturing was more usually promoted by conservatives who were isolationists. For two years, Nye, railing against “merchants of death,” led the most rigorous inquiry into the arms industry that any branch of the federal government has ever conducted. He convened ninety-three hearings. He thought that the ability to manufacture weapons should be restricted to the government. “The removal of the element of profit from war would materially remove the danger of more war,” he said. From the vantage of the du Ponts, the prospect of handing the manufacture of weapons over to the government represented the worst possible instance of laissez-faire economics yielding to a planned economy. The du Ponts were concerned, too, about the growing strength of labor unions, the number of strikes, and the establishment of the Securities Exchange Commission. Irénée du Pont wrote: “It must have now become clear to every thinking man that the so-called ‘New Deal,’ advocated by the Administration, is nothing more or less than the Socialistic doctrine called by another name.”64

To make this case to the American public, the du Ponts turned to the National Association of Manufacturers, whose president said, “The public does not understand industry, largely because industry itself has made no real effort to tell its story; to show the people of this country that our high living standards have risen almost altogether from the civilization which industrial activity has set up.” To that end, the association hired a publicist named Walter W. Weisenberger, appointing him executive vice president. Weisenberger used the tools of radio and paid advertisement to oppose both labor agitation and government regulation by arguing that peace and prosperity were best assured by the leadership of businessmen and a free market. One campaign motto: “Prosperity dwells where harmony reigns.”65 The Association insisted that its efforts were educational, but a congressional investigation led by Wisconsin Progressive Robert M. La Follette concluded otherwise. Business leaders, the La Follette Committee reported, “asked not what the weaknesses and abuses of the economic structure had been, and how they could be corrected, but instead paid millions to tell the public that nothing was wrong and that grave dangers lurked in the proposed remedies.”66

Other corporate leaders pursued similar aims. In July 1934, the du Ponts gathered fellow businessmen in the offices of General Motors in New York, where they founded a “propertyholders’ association” to oppose the New Deal; by August, this association had been incorporated as the American Liberty League. In pamphlets and in speeches, the league argued that the voice of business was being drowned out by the “ravenous madness” of the New Deal. Leaguers particularly objected to Social Security, described as the “taking of property without due process of law.” The majority of the league’s funding came from only thirty very wealthy men; Democrats dubbed it the “Millionaires Union.”67 It went by other names, too. In the U.S. presidential election of 1936, the Liberty League supported the Republican nominee, Alf M. Landon, an oil executive and governor of Kansas, through the efforts of an organization called the Farmers’ Independence Council. But the Farmer’s Independence Council had the same mailing address as the Liberty League and a membership that consisted, not of any farmers, but instead of Chicago meatpackers. Most of its funding came from Lammot du Pont, who defended his lobbying as a “farmer” by insisting that his ownership of a 4,000-acre estate made him one.68

Many kinds of conservatism coexisted in the United States in the 1930s, not yet sharing an ideology. Businessmen who opposed the New Deal generally had little in common with conservative intellectuals. like Albert Jay Nock, editor of a magazine called The Freeman and author of Our Enemy, the State (1935). While he complained about a centralized state, Nock was chiefly concerned with the rise of mass democracy and mass culture as harbingers of the decline of Western civilization, believing that radical egalitarianism had produced a world of mediocrity and blandness. American conservative intellectuals were opposed to socialism; they were isolationists; many tended to be anti-Semitic. In 1941, Nock wrote an essay for Atlantic Monthly called “The Jewish Problem in America.”69

Only after the war would the conservative movement find its base, and its direction. Meanwhile, the leftward drift of American politics in the 1930s was kept in check by the new businesses of political consulting and public opinion polling, the single most important forces in American democracy since the rise of the party system.

CAMPAIGNS, INC., the first political consulting firm in the history of the world, was founded by Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter in California in 1933. Critics called it the Lie Factory.

Political consulting, when it started, had one foot in advertising and one foot in journalism. Political consulting is often thought of as a product of the advertising industry, but the reverse is closer to the truth. When modern advertising began, in the 1920s, the industry’s big clients were interested in advancing a political agenda as much as, if not more than, a commercial one. Muckrakers and congressional investigations tended to make Standard Oil look greedy and Du Pont, for making munitions, sinister. Large corporations hired advertising firms to make themselves look better and to advance pro-business legislation.70

Political consulting’s origins in journalism lie with William Randolph Hearst. Whitaker, thirty-four, started out as a newspaperman, or, really, a newspaper boy; he was already working as a reporter at the age of thirteen. By nineteen, he was city editor for the Sacramento Union and, two years later, a political writer for the San Francisco Examiner, a Hearst paper. In the 1930s, one in four Americans got their news from Hearst, who owned twenty-eight newspapers in nineteen cities. Hearst’s papers were all alike: hot-blooded, with leggy headlines. Page one was supposed to make a reader blurt out, “Gee whiz!” Page two: “Holy Moses!” Page three: “God Almighty!” Hearst used his newspapers to advance his politics. In 1934, he ordered his editors to send reporters to college campuses, posing as students, to find out which members of the faculty were Reds. People Hearst thought were communists not infrequently thought Hearst was a fascist; he’d professed his admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. Hearst didn’t mind; he silenced his critics by attacking them in his papers relentlessly and ferociously. Some fought back. “Only cowards are intimated by Hearst,” Charles Beard said. In February 1935, Beard addressed an audience of a thousand schoolteachers in Atlantic City and said, of Hearst, “No person with intellectual honesty or moral integrity will touch him with a ten-foot pole.” The crowd gave Beard a standing ovation.71

Hearst endures, in American culture, in Citizen Kane, a film by Orson Welles released in 1941. The film bears so uncanny a resemblance to Imperial Hearst, a biography of Hearst published in 1936—with a preface by Beard—that the biographer sued the filmmakers. “I had never seen or heard of the book Imperial Hearst,” Welles insisted in a deposition for a case that was eventually settled out of court. Welles argued that his Citizen Kane wasn’t a character; he was a type: an American sultan. (The film was originally titled American.) If Kane, like Hearst, was a newspaper tycoon who turned to politics, that’s because, according to Welles, “such men as Kane always tend toward the newspaper and entertainment world,” despite hating the audience they crave, combining “a morbid preoccupation with the public with a devastatingly low opinion of the public mentality and moral character.” A man like Kane, Welles said, believes that “politics as the means of communication, and indeed the nation itself, is all there for his personal pleasuring.”72 Hearst would not be the last American sultan.

Clem Whitaker, having been trained by Hearst, left the San Francisco Examiner to start a newspaper wire service, the Capitol News Bureau, distributing stories to over eighty papers. In 1933, Sheridan Downey, a progressive California lawyer originally from Wyoming, hired Whitaker to help him defeat a referendum sponsored by Pacific Gas and Electric. Downey also hired Leone Baxter, a twenty-six-year-old widow who had been a writer for the Portland Oregonian, and suggested that she and Whitaker join forces. When Whitaker and Baxter defeated the referendum, Pacific Gas and Electric was so impressed that it put the two on retainer, and Whitaker and Baxter, who later married, started doing business as Campaigns, Inc.73

Campaigns, Inc., specialized in running political campaigns for businesses, especially monopolies like Standard Oil and Pacific Telephone and Telegraph. Working for the left-wing Downey had been an aberration. As a friend said, they liked to “work the Right side of the street.” In 1933, Upton Sinclair, an eccentric and dizzyingly prolific writer still best known for The Jungle, his 1906 muckraking indictment of the meat-packing industry, decided to run for governor of California. Sinclair, a longtime socialist, registered as a Democrat in order to seek the Democratic nomination, on a platform known as EPIC: End Poverty in California. After he unexpectedly won the nomination, he chose Downey as his running mate. (Their ticket was called “Uppie and Downey.”) Sinclair saw American history as a battle between business and democracy, and, “so far,” he wrote, “Big Business has won every skirmish.”74

Emboldened by Roosevelt’s winning of the White House, Sinclair decided to take a shot at the governor’s office. Whitaker and Baxter, like most California Republicans, were horrified at the prospect of a Sinclair governorship.75 Two months before the election, they began working for George Hatfield, a candidate for lieutenant governor on a Republican ticket headed by the incumbent governor, Frank Merriam. They locked themselves in a room for three days with everything Sinclair had ever written. “Upton was beaten,” Whitaker later said, “because he had written books.”76 The Los Angeles Times began running on its front page a box with an Upton Sinclair quotation in it, a practice the paper continued every day for six weeks, right up until Election Day. For instance:

SINCLAIR ON MARRIAGE:

THE SANCTITY OF MARRIAGE. . . . I HAVE HAD SUCH A BELIEF . . .

I HAVE IT NO LONGER.77

The passage, as Sinclair explained in a book called I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, was taken from his novel Love’s Pilgrimage (1911), in which a fictional character writes a heartbroken letter to a man having an affair with his wife.78 “Reading these boxes day after day,” Sinclair wrote, “I made up my mind that the election was lost.”79

The nation was founded on self-evident truths. But, as Sinclair argued, voters were now being led by a Lie Factory. “I was told they had a dozen men searching the libraries and reading every word I had ever published,” he wrote. They’d find lines he’d written, speeches of fictional characters in novels, and stick them in the paper as if Sinclair had said them. “They had an especially happy time with The Profits of Religion,” Sinclair said, referring to his 1917 polemic about institutionalized religion. “I received many letters from agitated old ladies and gentlemen on the subject of my blasphemy. ‘Do you believe in God?’ asked one.” There was very little he could do about it. “They had a staff of political chemists at work, preparing poisons to be let loose in the California atmosphere on every one of a hundred mornings.”80

“Sure, those quotations were irrelevant,” Baxter later said. “But we had one objective: to keep him from becoming Governor.” They succeeded. The final vote was Merriam, 1,138,000; Sinclair, 879,000.81 No single development altered the workings of American democracy so wholly as the industry Whitaker and Baxter founded. “Every voter, a consumer; every consumer, a voter” became its mantra.82 They succeeded best by being noticed least. Progressive reformers dismantled the party machine. But New Dealers barely noticed when political consultants replaced party bosses as the wielders of political power gained not by votes but by money.

Whitaker and Baxter won nearly every campaign they waged.83 The campaigns they chose to run, and the way they decided to run them, shaped the history of California and of the country. They drafted the rules by which campaigns would be waged for decades afterward. The first thing they did, when they took on a campaign, was to “hibernate” for a week to write a Plan of Campaign. Then they wrote an Opposition Plan of Campaign, to anticipate the moves made against them. Every campaign needs a theme.84 Keep it simple. Rhyming’s good (“For Jimmy and me, vote ‘yes’ on 3”). Never explain anything. “The more you have to explain,” Whitaker said, “the more difficult it is to win support.” Say the same thing over and over again. “We assume we have to get a voter’s attention seven times to make a sale,” Whitaker said. Subtlety is your enemy. “Words that lean on the mind are no good,” according to Baxter. “They must dent it.” Simplify, simplify, simplify. “A wall goes up,” Whitaker warned, “when you try to make Mr. and Mrs. Average American Citizen work or think.”85

Make it personal, Whitaker and Baxter always advised: candidates are easier to sell than issues. If your position doesn’t have an opposition, or if your candidate doesn’t have an opponent, invent one. Once, when fighting an attempt to recall the mayor of San Francisco, Whitaker and Baxter waged a campaign against the Faceless Man—the idea was Baxter’s—who might end up replacing him. Baxter drew a picture, on a tablecloth, of a fat man with a cigar poking out from beneath a face hidden by a hat, and then had him plastered on billboards all over the city, with the question “Who’s Behind the Recall?” Pretend that you are the Voice of the People. Whitaker and Baxter bought radio ads, sponsored by “the Citizens Committee Against the Recall,” in which an ominous voice said: “The real issue is whether the City Hall is to be turned over, lock, stock, and barrel, to an unholy alliance fronting for a faceless man.” (The recall was defeated.) Attack, attack, attack. Said Whitaker: “You can’t wage a defensive campaign and win!” Never underestimate the opposition.86

Never shy from controversy, they advised; instead, win the controversy. “The average American,” Whitaker wrote, “doesn’t want to be educated; he doesn’t want to improve his mind; he doesn’t even want to work, consciously, at being a good citizen. But there are two ways you can interest him in a campaign, and only two that we have ever found successful.” You can put on a fight (“he likes a good hot battle, with no punches pulled”), or you can put on a show (“he likes the movies; he likes mysteries; he likes fireworks and parades”): “So if you can’t fight, PUT ON A SHOW! And if you put on a good show, Mr. and Mrs. America will turn out to see it.”87

Whitaker and Baxter, more effectively than any politician, addressed the problem of mass democracy with an elegant solution: they turned politics into a business. But their very success depended, in part, on the rise of another political industry: public opinion polling.

THE AMERICAN PUBLIC OPINION industry began as democracy’s answer to fascist propaganda. By the end of 1933, Joseph Goebbels had established a Broadcasting Division within his Ministry of Propaganda and had undertaken production of cheap radio sets, the Volksempfanger, or “people’s set,” with the aim of ensuring that the government could reach every household, in a practice Goebbels liked to describe as “mind-bombing.”88 Fascists told the people what to believe; democrats asked them. But the scientific measurement of public opinion would come to rest on its ability to accurately predict the outcome of national elections. From the start, the industry embraced a paradox. Publicly and reliably predicting the outcome of an election would seem to undercut democracy, not promote it. Notwithstanding this paradox, polling proceeded.

Newspapers had been predicting local election results for decades, but predicting the outcome of a national election required a network of newspapers. In 1904, the New York Herald, the Cincinnati Enquirer, the Chicago Record-Herald and the St. Louis Republic joined forces to forecast elections, tallying their straws together. By 1916, the Herald had organized a group of newspapers in thirty-six states. That year, the Literary Digest, a national magazine, began mailing out ballots as a publicity stunt. The Digest used its polls to try to attract new subscribers; its plan was to collect more ballots than anyone else. In 1920, the Digest distributed eleven million ballots and, in 1924, more than sixteen million.89 For reach, its only real rival was the chain of newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst, which was able to report the results of polls in forty-three states. Although the Literary Digest sometimes miscalculated the popular vote, it always got the Electoral College winner right. In 1924, the Digest’s forecast was right for all but two states and in 1928 for all but four.

A newspaperman named Emil Hurja figured out that this method was nevertheless bound to fail, since what matters is not the size of a stack of straws but its variety. Hurja tried to convince the Democratic National Committee to conduct its straw polls using ore sampling methods. “In mining you take several samples from the face of the ore, pulverize them, and find out what the average pay per ton will be,” Hurja explained. “In politics you take sections of voters, check new trends against past performances, establish percentage shift among different voting strata, supplement this information from competent observers in the field, and you can accurately predict an election result.” In 1928, the DNC dismissed Hurja as a crank, but by 1932 he was running FDR’s campaign.90 By 1932, the Literary Digest’s mailing list had grown to more than twenty million names. Most of those names were taken from telephone directories and automobile registration files. Hurja was one of the few people who understood that the Digest had consistently underestimated FDR’s support because its sample, while very big, was not very representative: people who supported FDR were much less likely than the rest of the population to own a telephone or a car.91

Hurja was borrowing from the insights of social science. But the real innovation in public opinion measurement was a method that had been devised by social scientists in the 1920s, which was to use statistics to estimate the opinions of a vast population by surveying a statistically representative sample.

Political polling is the marriage of journalism and social science, a marriage made by George Gallup. “When I went to college, I wanted to study journalism, and later on go out and be an editor of a newspaper,” Gallup said, remembering his days at the University of Iowa in the 1920s, but “in my day I couldn’t get a degree in journalism, so I got my degree in psychology.” He graduated in 1923, entered a graduate program in a new field, Applied Psychology, where everyone was talking about Walter Lippmann’s 1922 book, Public Opinion, and Gallup got interested in the problem of measuring it. His first idea was to use the sample survey to understand how people read the news. In 1928, in a dissertation called “An Objective Method for Determining Reader Interest in the Content of a Newspaper,” he argued that “at one time the press was depended upon as the chief agency for instructing and informing the mass of people,” but that the growth of public schools meant that newspapers no longer filled that role and instead ought to meet “a greater need for entertainment.” He had therefore devised a method to measure “reader interest,” a way to know what parts of the paper readers found entertaining. He called it the “Iowa method”: “It consists chiefly of going through a newspaper, column by column, with a reader of the paper.” The interviewer would then mark up the newspaper to show what parts the reader had enjoyed. “The Iowa method offers the newspaper editor a scientific means for fitting his paper to his community,” Gallup wrote: he could hire an expert in measurement to conduct a study to find out what features and writers his readers like best, and then stop printing the boring stuff.92

In 1932, when Gallup was a professor of journalism at Northwestern, his mother-in-law, Ola Babcock Miller, ran for lieutenant governor of Iowa. Her husband had died in office; her nomination was largely honorary and she was not expected to win. Gallup decided to apply his ideas about measuring reader interest to understanding her chances. After that, he moved to New York and began working for an advertising agency, where, while also teaching at Columbia, he perfected a method for measuring the size of a radio audience. He conducted some experiments in 1933 and 1934, trying to figure out how to better predict elections for newspapers and magazines, and started a company he named the Editors’ Research Bureau. Gallup liked to call public opinion measurement “a new field of journalism.” But he decided his work needed a scholarly pedigree. In 1935, he renamed the Editors’ Research Bureau the American Institute of Public Opinion and established it in Princeton, New Jersey, which also made it sound more academic.93

Gallup’s method was to survey public opinion by asking questions of a sample of the population carefully chosen to represent the whole of it. He said he was taking the “pulse of democracy.” (Wrote a skeptical E. B. White: “Although you can take a nation’s pulse, you can’t be sure that the nation hasn’t just run up a flight of stairs.”) In 1935, to announce the publication of a new weekly column by Gallup, the Washington Post launched a blimp over the nation’s capital trailing a streamer that read “America Speaks!”94

Gallup intended the measurement of public opinion to be a tool for democratic government, a tool intended to do the very opposite of the work of political consulting. Political consulting is the business of managing the opinions of the masses. Public opinion surveying is the business of finding out the opinions of the masses. Political consultants tell voters what to think; pollsters ask them what they think. But neither of these businesses gives a great deal of credit to the idea that voters ought to make independent judgments, or that they can.