Thirteen

A WORLD OF KNOWLEDGE

THE END OF TIME BEGAN AT EIGHT FIFTEEN ON THE morning of August 6, 1945. “Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk,” the writer John Hersey reported in The New Yorker. “Just as she turned her head away from the windows, the room was filled with a blinding light. She was paralyzed by fear, fixed still in her chair for a long moment.”

Everything fell, and Miss Sasaki lost consciousness. The ceiling dropped suddenly and the wooden floor above collapsed in splinters and the people up there came down and the roof above them gave way; but principally and first of all, the bookcases right behind her swooped forward and the contents threw her down, with her left leg horribly twisted and breaking underneath her. There, in the tin factory, in the first moment of the atomic age, a human being was crushed by books.1

In the first moment of the atomic age, a human being was crushed by books: the violence of knowledge.

Hiroshima marked the beginning of a new and differently unstable political era, in which technological change wildly outpaced the human capacity for moral reckoning. It wasn’t only the bomb, and the devastation it wreaked. It was the computers whose development had made dropping the bomb possible. And it was the force of technological change itself, a political power unchecked by an eighteenth-century constitution and unfathomed by a nineteenth-century faith in progress.

Truman got word of the bombing on board a cruiser. The White House told the press the next day. The story went out over the radio at noon. Listeners reeled. John Haynes Holmes, a Unitarian minister and avowed pacifist, was on vacation at a cottage in Kennebunk, Maine. “Everything else seemed suddenly to become insignificant,” he said, about how he felt when he heard the news. “I seemed to grow cold, as though I had been transported to the waste spaces of the moon.” Days later, when the Japanese were forced to surrender, Americans celebrated. In St. Louis, people drove around the city with tin cans tied to the bumpers of their cars; in San Francisco, they tugged trolley cars off their tracks. More than four hundred thousand Americans had died in a war that, worldwide, had taken the lives of some sixty million people.2

And yet, however elated at the peace, Americans worried about how the war had ended. “There was a special horror in the split second that returned so many thousand humans to the primeval dust from which they sprang,” one Newsweek editorial read. “For a race which still did not entirely understand steam and electricity it was natural to say: ‘who next?’” Doubts gathered, and grew. “Seldom if ever has a war ended leaving the victors with such a sense of uncertainty and fear,” CBS’s Edward R. Murrow said. “We know what the bombs did to Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” wrote the editors of Fortune. “But what did they do to the U.S. mind?”3

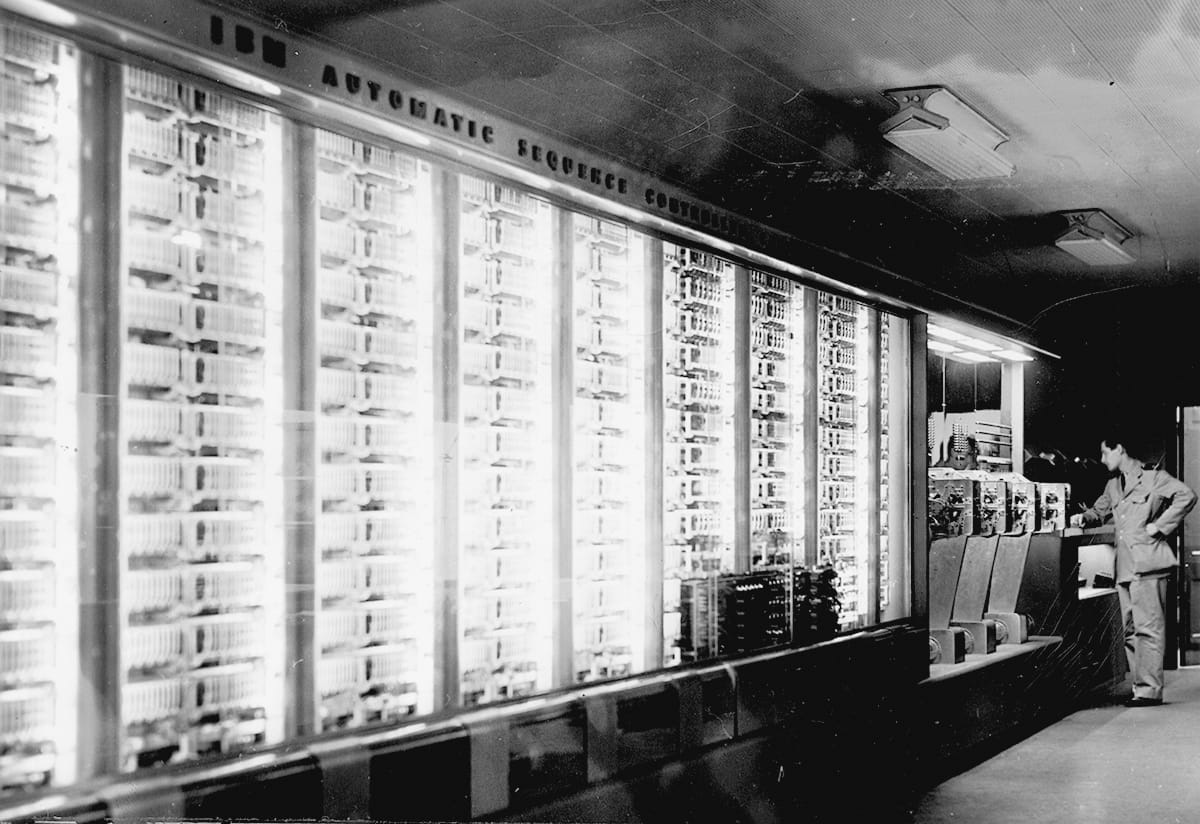

Part of the uncertainty was a consequence of the surprise. Americans hadn’t known about the bomb before it fell. The Manhattan Project was classified. Even Truman hadn’t known about it until after FDR’s death. Nor had Americans known about the computers the military had been building, research that had also been classified, but which was dramatically revealed the winter after the war. “One of the war’s top secrets, an amazing machine which applies electronic speeds for the first time to mathematical tasks hitherto too difficult and cumbersome for solution, was announced here tonight by the War Department,” the New York Times reported from Philadelphia on February 15, 1946, in a front-page story introducing ENIAC, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, the first general-purpose electronic digital computer. Inside, the Times ran a full-page spread, including a photograph of the computer, the size of a room.4 It was as if the curtain had been lifted, a magician’s veil.

Like the atomic bomb, ENIAC was produced by the American military to advance the cause of war and relied on breakthroughs made by scientists in other parts of the world. In 1936, the English mathematician Alan Turing completed a PhD at Princeton and wrote a paper called “On Computable Numbers,” in which he predicted the possibility of inventing “a single machine that can be used to compute any computable sequence.”5 The next year, Howard Aiken, a doctoral student at Harvard, poking around in the attic of a Harvard science building, found a model of Charles Babbage’s early nineteenth-century Difference Engine; Aiken then proposed, to IBM, to build a new and better version, not mechanical but electronic. That project began at IBM in 1941 and three years later moved to Harvard, where Aiken, now a naval officer, was in charge of the machine, known as Mark I; Columbia astronomer L. J. Comrie called it “Babbage’s dream come true.” The Mark I was programmed by a longtime Vassar professor, the brilliant mathematician Grace Murray Hopper. “Amazing Grace,” her colleagues nicknamed her, and she understood, maybe better than anyone, how far-reaching were the implications of a programmable computer. As she would explain, “It is the current aim to replace, as far as possible, the human brain.”6

During the war, the Allied military had been interested in computers for two primary reasons: to break codes and to calculate weapons trajectories. At Bletchley Park, a six-hundred-acre manorial estate fifty miles northwest of London that became a secret military facility, Turing, who would later be prosecuted for homosexuality and die of cyanide poisoning, had by 1940 built a single-purpose computer able to break the codes devised by Germany’s Enigma machine. At the University of Pennsylvania, physicist John Mauchly and electrical engineer Presper Eckert had been charged with calculating firing-angle settings for artillery, work that required iterative and time-consuming calculations. To do that work, American scientists had been using an analog computer called a differential analyzer, invented at MIT in 1931 by FDR research czar Vannevar Bush, an electrical engineer. Numbers were entered into the differential analyzer by people who were known as “computers,” and who were usually women with mathematics degrees, not unlike the “checkers,” women with literature degrees, who worked at magazines. But even when these women entered numbers around the clock, it took a month to generate a single artillery-trajectory table. In August 1942, Mauchly proposed using vacuum tubes to build a digital electronic computer that would be much faster. The U.S. War Department decided on April 9, 1943, to fund it. Construction of ENIAC began in June 1943, but it wasn’t fully operational until July 1945. ENIAC could make calculations a hundred times faster than any earlier machine. Its first assignment, in the fall of 1945, came from Los Alamos: using nearly a million punch cards, each prepared and entered into the machine by a team of female programmers, ENIAC calculated the force of reactions in a fusion reaction, for the purpose of devising a hydrogen bomb.7

The machines built to plot the trajectories and force of missiles and bombs would come to transform economic systems, social structures, and the workings of politics. Computers are often left out of the study of history and government, but, starting at the end of the Second World War, history and government cannot be understood without them. Democracies rely on an informed electorate; computers, the product of long and deep study and experiment, would both explode and unsettle the very nature of knowledge.

The boundlessness of scientific inquiry also challenged the boundaries of the nation-state. After the war, scientists were among the loudest constituencies calling for international cooperation and, in particular, for a means by which atomic war could be averted. Instead, their work was conscripted into the Cold War.

The decision to lift the veil of secrecy and display ENIAC to the public came at a moment when the nation was engaged in a heated debate about the role of the federal government in supporting scientific research. During the war, at the urging of Vannevar Bush, FDR had created both the National Defense Research Committee and the Office of Scientific Research and Development. (Bush headed both.) Near the end of the war, Roosevelt had asked Bush to prepare a report that, in July 1945, Bush submitted to Truman. It was called “Science, the Endless Frontier.”8

“A nation which depends upon others for its new basic scientific knowledge will be slow in its industrial progress and weak in its competitive position in world trade,” Bush warned. “Advances in science when put to practical use mean more jobs, higher wages, shorter hours, more abundant crops, more leisure for recreation, for study, for learning how to live without the deadening drudgery which has been the burden of the common man for ages past.”9

At Bush’s urging, Congress debated a bill to establish a new federal agency, the National Science Foundation. Critics said the bill tied university research to the military and to business interests and asked whether scientists had not been chastened by the bomb. Scientific advances did indeed relieve people of drudgery and produce wealth and leisure, but the history of the last century had shown nothing if not that these benefits were spread so unevenly as to cause widespread political unrest and even revolution; the project of Progressive and New Deal reformers had been to protect the interests of those left behind by providing government supports and regulations. Could this practice be applied to the federal government’s relationship to science? Democratic senator Harley M. Kilgore, a former schoolteacher from West Virginia, introduced a rival bill that extended the antimonopoly principles of the New Deal to science, tied university research to government planning, and included in the new foundation a division of social science, to provide funding for research designed to solve social and economic problems, on the grounds that one kind of knowledge had gotten ahead of another: human beings had learned how to destroy the entire planet but had not learned how to live together in peace. During Senate hearings, former vice president Henry Wallace said, “It is only by pursuing the field of the social sciences comprehensively” that the world could avoid “bigger and worse wars.”10

Many scientists, including those who belonged to the newly formed Federation of Atomic Scientists, agreed, and two rivulets of protest became a stream: a revision of Kilgore’s bill was attached to a bill calling for civilian control of atomic power. Atomic scientists launched a campaign to enlist the support of the public. “To the village square we must carry the facts of atomic energy,” Albert Einstein said. “From there must come America’s voice.” Atomic scientists spoke at Kiwanis clubs, at churches and at synagogues, at schools and libraries. In Kansas alone, they held eight Atomic Age Conferences. And they published One World or None: A Report to the Public on the Full Meaning of the Atomic Bomb, essays by atomic scientists, including Leo Szilard and J. Robert Oppenheimer, and by political commentators, including Walter Lippmann. Albert Einstein, in his essay, argued for “denationalization.”11

Against this campaign stood advocates for federal government funding of the new field of computer science, who launched their own publicity campaign, beginning with the well-staged unveiling of ENIAC. It had been difficult to stir up interest. No demonstration of a general-purpose computer could have the drama of an atomic explosion, or even of the 1939 World’s Fair chain-smoking Elektro the Moto-Man. ENIAC was inert. Its vacuum tubes, lit by dim neon bulbs, were barely visible. When the machine was working, there was no real way to see much of anything happening. Mauchly and Eckert prepared press releases and, in advance of a scheduled press conference, tricked up the machine for dramatic effect. Eckert cut Ping-Pong balls in half, wrote numbers on them, and placed them over the tips of the bulbs, so that when the machine was working, the room flashed as the lights flickered and blinked. It blinked fast. The Times gushed, “The ‘Eniac,’ as the new electronic speed marvel is known, virtually eliminates time.”12

The unintended consequences of the elimination of time would be felt for generations. But the great acceleration—the speeding up of every exchange—had begun. And so had the great atomization—the turning of citizens into pieces of data, fed into machines, tabulated, processed, and targeted, as the nation-state began to yield to the data-state.

I.

THE END OF THE WAR marked the dawn of an age of affluence, a wide and deep American prosperity. It led both to a new direction for liberalism—away from an argument for government regulation of business and toward an insistence on individual rights—and to a new form of conservatism, dedicated to the fight against communism and deploying to new ends the rhetoric of freedom.

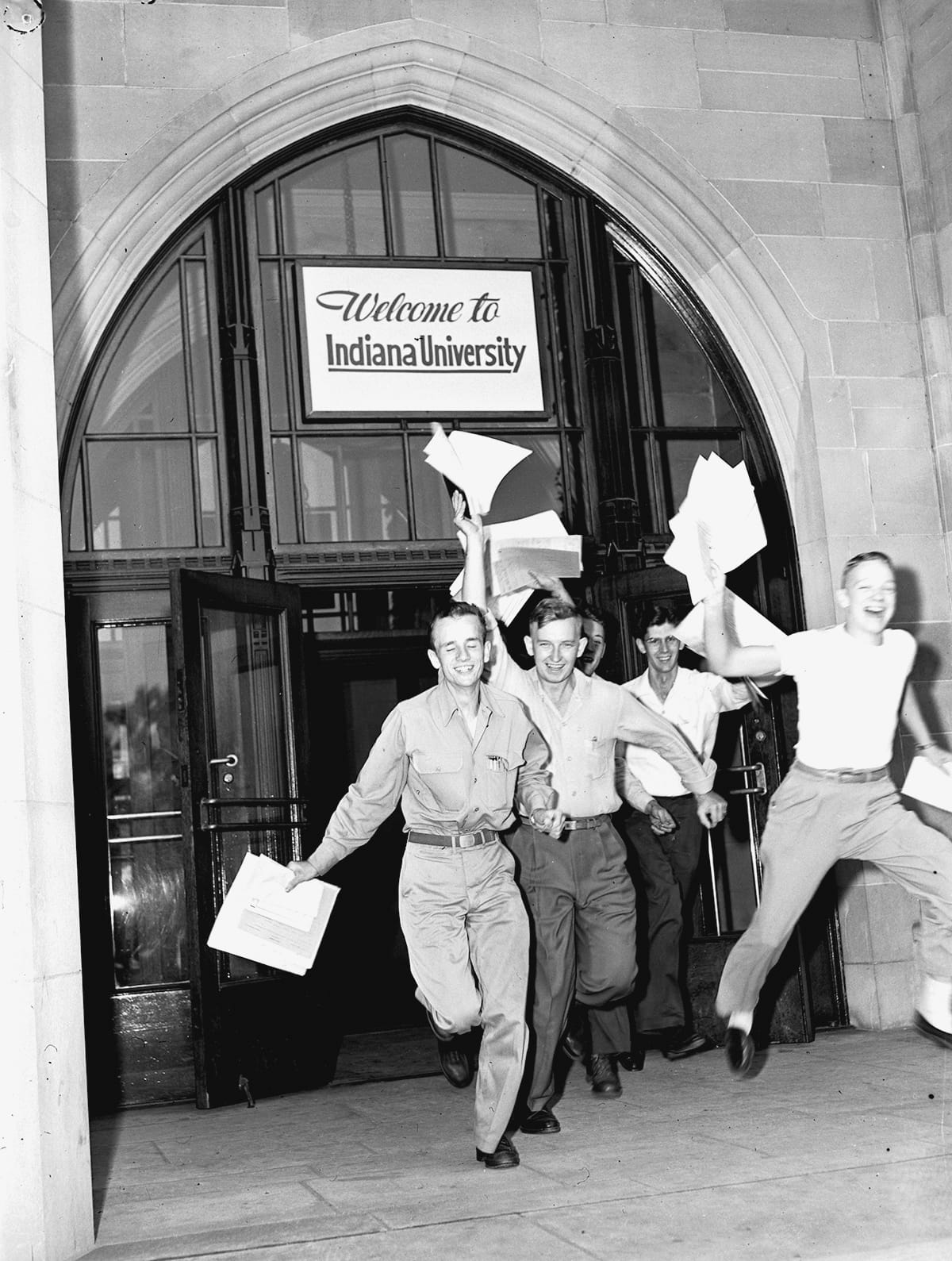

The origins of postwar prosperity lay in the last legislative act of the New Deal. In June 1944, FDR had signed the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act, better known as the G.I. Bill of Rights. It created a veterans-only welfare state. The G.I. Bill extended to the sixteen million Americans who served in the war a series of benefits, including a free, four-year college education, zero-down-payment low-interest loans for homes and businesses, and a “readjustment benefit” of twenty dollars a week for up to fifty-two weeks, to allow returning veterans to find work. More than half of eligible veterans—some eight million Americans—took advantage of the G.I. Bill’s educational benefits. Those who did enjoyed average earnings of $10,000–$15,000 more than those who didn’t. They also paid more in taxes. By 1948, the cost of the G.I. Bill constituted 15 percent of the federal budget. But, with rising tax revenues, the G.I. Bill paid for itself almost ten times over. It created a new middle class, changed the face of American colleges and universities, and convinced many Americans that the prospects for economic growth, for each generation’s achieving a standard of living higher than the generation before, might be limitless.13

That growth was achieved, in part, by consumer spending, as factories outfitted for wartime production were converted to manufacture consumer goods, from roller skates to color televisions. The idea of the citizen as a consumer, and of spending as an act of citizenship, dates to the 1920s. But in the 1950s, mass consumption became a matter of civic obligation. By buying “the dozens of things you never bought or even thought of before,” Brides magazine told its readers, “you are helping to build greater security for the industries of this country.”14

Critics suggested that the banality and conformity of consumer society had reduced Americans to robots. John Updike despaired: “I drive my car to supermarket, / The way I take is superhigh, / A superlot is where I park it, / And Super Suds are what I buy.”15 Nothing epitomized what critics called the “Packaged Society” so much as Disneyland, an amusement park that had opened in 1955 as a reimagined 1939 World’s Fair, more provincial and more commercial, with a Main Street and a Tomorrowland. In Frontierland, Walt Disney explained, visitors “can return to frontier America, from the Revolutionary Era to the final taming of the great southwest,” riding stagecoaches and Conestoga wagons over dusty trails and boarding the steamship Mark Twain within sight of the park’s trademark turquoise-towered castle, a fairyland that sold itself as “The Happiest Place on Earth.”16

Most of the buying was done by women: housewives and mothers. The home, which had become separated from work during the process of industrialization, became a new kind of political space, in which women met the obligations of citizenship by spending money. Domesticity itself took on a different cast, as changes to the structure of the family that had begun in the Depression and continued during the war were reversed. Before the war, age at first marriage had been rising; after the war, it began falling. The number of children per family had been falling; it began rising. More married women and mothers of young children had been entering the paid labor force; they began leaving it. Having bigger families felt, to many Americans, an urgent matter. “After the Holocaust, we felt obligated to have lots of babies,” one Jewish mother later explained. “But it was easy because everyone was doing it—non-Jews, too.” Expectations of equality between men and women within marriage diminished, as did expectations of political equality. Claims for equal rights for women had been strenuously pressed during the war, but afterwards, they were mostly abandoned. In 1940, the GOP had supported the Equal Rights Amendment (first introduced into Congress in 1923), and in 1944 the Democrats had supported it, too. The measure reached the Senate in 1946, where it won a plurality, but fell short of the two-thirds vote required to send an amendment to the states for ratification.17 It would not pass Congress until 1972, after which an army of housewives, the foot soldiers of the conservative movement, would block its ratification.

The G.I. Bill, for all that it did to build a new middle class, also reproduced and even exacerbated earlier forms of social and economic inequality. Most women who had served in the war were not eligible for benefits; the women’s auxiliary divisions of the branches of the military had been deliberately decreed to be civilian units with an eye toward avoiding providing veterans’ benefits to women, on the assumption that they would be supported by men. After the war, when male veterans flocked to colleges and universities, many schools stopped admitting women, or reduced their number, in order to make more room for men. And, even among veterans, the bill’s benefits were applied unevenly. Some five thousand soldiers and four thousand sailors had been given a “blue discharge” during the war as suspected homosexuals; the VA’s interpretation of that discharge made them ineligible for any G.I. Bill benefits.18

African American veterans were excluded from veterans’ organizations; they faced hostility and violence; and, most significantly, they were barred from taking advantage of the G.I. Bill’s signal benefits, its education and housing provisions. In some states, the American Legion, the most powerful veterans’ association, refused to admit African Americans, and proved unwilling to recognize desegregated associations. Money to go to college was hard to use when most colleges and universities refused to admit African Americans and historically black colleges and universities had a limited number of seats. The University of Pennsylvania had nine thousand students in 1946; only forty-six were black. By 1946, some one hundred thousand black veterans had applied for educational benefits; only one in five had been able to register for college. More than one in four veterans took advantage of the G.I. Bill’s home loans, which meant that by 1956, 42 percent of World War II veterans owned their own homes (compared to only 34 percent of nonveterans). But the bill’s easy access to credit and capital was far less available to black veterans. Banks refused to give black veterans loans, and restrictive covenants and redlining meant that much new housing was whites-only.19

Even after the Supreme Court struck down restrictive housing covenants in 1948, the Federal Housing Administration followed a policy of segregation, routinely denying loans to both blacks and Jews. In cities like Chicago and St. Louis and Los Angeles and Detroit, racially restrictive covenants in housing created segregated ghettos where few had existed before the war. Whites got loans, had their housing offers accepted, and moved to the suburbs; blacks were crowded into bounded neighborhoods within the city. Thirteen million new homes were built in the United States during the 1950s; eleven million of them were built in the suburbs. Eighty-three percent of all population growth in the 1950s took place in the suburbs. For every two blacks who moved to the cities, three whites moved out. The postwar racial order created a segregated landscape: black cities, white suburbs.20

The New Deal’s unfinished business—its inattention to racial discrimination and racial violence—became the business of the postwar civil rights movement, as new forms of discrimination and the persistence of Jim Crow laws and even of lynching—in 1946 and 1947, black veterans were lynched in Georgia and Louisiana—contributed to a new depth of discontent. As a black corporal from Alabama put it, “I spent four years in the Army to free a bunch of Dutchmen and Frenchmen, and I’m hanged if I’m going to let the Alabama version of the Germans kick me around when I get home.” Langston Hughes, who wrote a regular column for the Chicago Defender, urged black Americans to try to break Jim Crow laws at lunch counters. “Folks, when you go South by train, be sure to eat in the diner,” Hughes wrote. “Even if you are not hungry, eat anyhow—to help establish that right.”21

But where Roosevelt had turned a blind eye, Truman did not. He had grown up in Independence, Missouri, just outside of Kansas City, and worked on the family farm until the First World War, when he saw combat in France. Back in Missouri, he began a slow ascension through the Democratic Party ranks, starting with a county office and rising to the U.S. Senate in 1934. Roosevelt had chosen him as his running mate in 1944 chiefly because he was unobjectionable; neither wing of the Democratic Party was troubled by Truman. He had played virtually no role in White House affairs during his vice presidency, and was little prepared to move into the Oval Office upon Roosevelt’s death. No president had faced a greater trial by fire than the decision that had fallen to Truman over whether or not to use the atomic bomb. Mild-mannered and myopic, Truman had a common touch. Unlike most American presidents, he had neither a college degree nor a law degree. For all his limitations as a president, he had an intuitive sense of the concerns of ordinary Americans. And, from the very beginning of his career, he’d courted black voters and worked closely with black politicians.

Unwilling to ignore Jim Crow, Truman established a commission on civil rights. To Secure These Rights, its 1947 report, demonstrated that a new national consensus had been reached, pointing to a conviction that the federal government does more than prevent the abuse of rights but also secures rights. “From the earliest moment of our history we have believed that every human being has an essential dignity and integrity which must be respected and safeguarded,” read the report. “The United States can no longer countenance these burdens on its common conscience.”22

Consistent with that commitment, Truman made national health insurance his first domestic policy priority. In September 1945, he asked Congress to act on FDR’s Second Bill of Rights by passing what came to be called a Fair Deal. Its centerpiece was a call for universal medical insurance. The time seemed, finally, right, and Truman enjoyed some important sources of bipartisan support, including from Earl Warren, the Republican governor of California. What Truman proposed was a national version of a plan Warren had proposed in California: compulsory insurance funded with a payroll tax. “The health of American children, like their education, should be recognized as a definite public responsibility,” the president said.23

Warren, the son of a Norwegian immigrant railroad worker, a striker who was later murdered, had grown up knowing hardship. After studying political science and the law at Berkeley and serving during the First World War, he’d become California’s attorney general in 1939. In that position, he’d been a strong supporter of the Japanese American internment policy. “If the Japs are released,” Warren had warned, “no one will be able to tell a saboteur from any other Jap.” (Warren later publicly expressed pained remorse about this policy and, in a 1972 interview, wept over it.) On the strength of his record as attorney general, Warren had run for governor in 1942. Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter had managed his campaign, which had been notoriously heated. “War-time voters live at an emotional pitch that is anything but normal,” Whitaker had written in his Plan of Campaign. “This must be a campaign that makes people hear the beat of drums and the thunder of bombs—a campaign that stirs and captures the imagination; a campaign that no one who loves California can disregard. This must be A CALL TO ARMS IN DEFENSE OF CALIFORNIA!”24

Warren won, but he didn’t like how he’d won. Just before the election, he fired Whitaker and Baxter. They never forgave him.

Late in 1944, Warren had fallen seriously ill with a kidney infection. His treatment required heroic and costly medical intervention. He began to consider the catastrophic effects a sudden illness could have on a family of limited means. “I came to the conclusion that the only way to remedy this situation was to spread the cost through insurance,” he later wrote. He asked his staff to develop a proposal. After conferring with the California Medical Association, he anticipated no objections from doctors. And so, in his January 1945 State of the State address, Warren announced his plan, a proposal modeled on the social security system: a 1½ percent withholding of wages would contribute to a statewide compulsory insurance program.25 And then the California Medical Association hired Campaigns, Inc.

Earl Warren began his political career as a conservative and ended it as a liberal. Years later, Leone Baxter was asked by a historian what she made of Warren’s seeming transformation. Warren’s own explanation, the historian told Baxter, was this: “I grew up a poor boy myself and I saw the trials and tribulations of getting old without having any income and being sick and not being able to work.” Baxter shot back, “He didn’t see them until that Sunday in 1945.” Then she ended the interview.26

What really changed Earl Warren was Campaigns, Inc. Whitaker and Baxter took a piece of legislation that enjoyed wide popular support and torpedoed it. Fifty newspapers initially supported Warren’s plan; Whitaker and Baxter whittled that down to twenty. “You can’t beat something with nothing,” Whitaker liked to say, so they launched a drive for private health insurance. Their “Voluntary Health Insurance Week,” driven by 40,000 inches of advertising in more than four hundred newspapers, was observed in fifty-three of the state’s fifty-eight counties. Whitaker and Baxter sent more than nine thousand doctors out with prepared speeches. They coined a slogan: “Political medicine is bad medicine.”27 They printed postcards for voters to stick in the mail:

Dear Senator:

Please vote against all Compulsory Health Insurance Bills pending before the Legislature. We have enough regimentation in this country now. Certainly we don’t want to be forced to go to “A State doctor,” or to pay for such a doctor whether we use him or not. That system was born in Germany—and is part and parcel of what our boys are fighting overseas. Let’s not adopt it here.28

When Warren’s bill failed to pass by just one vote, he blamed Whitaker and Baxter. “They stormed the Legislature with their invective,” he complained, “and my bill was not even accorded a decent burial.”29 It was the greatest legislative victory at the hands of admen the country had ever seen. It would not be the last.

II.

RICHARD MILHOUS NIXON counted his resentments the way other men count their conquests. Born in the sage-and-cactus town of Yorba Linda, California, in 1913, he’d been a nervous kid, a whip-smart striver. His family moved to Whittier, where his father ran a grocery store out of an abandoned church. Nixon went to Whittier College, working to pay his way, resenting that he didn’t have the money to go somewhere else. He had wavy black hair; small, dark eyes; and heavy, brooding eyebrows. An ace debater, he’d gone after college to Duke Law School, resented all the Wall Street law firms that refused to hire him when he finished, and returned to Whittier. He went away again, to serve in the navy in the South Pacific. And when he got back, serious and strenuously intelligent Lieutenant Commander Nixon, thirty-two, was recruited by a group of California bankers and oilmen to try to defeat five-term Democratic incumbent Jerry Voorhis for a seat in the House. The man from Whittier wanted to go to Washington.

Voorhis, a product of Hotchkiss and Yale and a veteran of Upton Sinclair’s EPIC campaign, was a New Dealer who’d first been elected to Congress in 1936, but, ten years later, the New Deal was old news. The midterm elections during Truman’s first term—and the fate of his legislative agenda—were tied to heightening tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. Nixon in California was only one in a small battalion of younger men, mainly ex-servicemen, who ran for office in 1946, the nation’s first Cold Warriors. In Massachusetts, another veteran of the war in the Pacific, twenty-nine-year-old John F. Kennedy, ran for a House seat from the Eleventh District. But, unlike Nixon, he’d been readied for that seat from the cradle.

Kennedy, born to wealth and groomed at Choate and Harvard, represented everything Nixon detested: all that Nixon had fought for, by tooth and claw, had been handed to Kennedy, on a platter decorated with a doily. But both Nixon and Kennedy were powerfully shaped by the rising conflict with the Soviet Union, and both understood domestic affairs through the lens of foreign policy. After Stalin broke the promise he’d made at Yalta to allow Poland “free and unfettered elections,” it had become clear that he was ruthless, even if the West had, as yet, little knowledge of the purges with which he was overseeing the murder of millions of people. Inside the Truman administration, a conviction grew that the Soviet regime was ideologically and militarily relentless. In February 1946, George Kennan, an American diplomat in Moscow, sent the State Department an 8,000-word telegram in which he reported that the Soviets were resolute in their determination to battle the West in an epic confrontation between capitalism and communism. “We have here a political force committed fanatically to the belief that with US there can be no permanent modus vivendi that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted, our traditional way of life be destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken, if Soviet power is to be secure,” Kennan wrote. “This political force has complete power of disposition over energies of one of world’s greatest peoples and resources of world’s richest national territory, and is borne along by deep and powerful currents of Russian nationalism.” Two weeks later, Winston Churchill, speaking in Truman’s home state of Missouri, warned of an “iron curtain” falling across Europe.30

The postwar peace had been fleeting. As keenly as Roosevelt and Churchill had wanted to avoid repeating the mistakes of the peace made at the end of the First World War, political instability had inevitably trailed behind the devastation of the Second World War. The Soviet Union’s losses had been staggering: twenty-seven million Russians died, ninety times as many casualties as were suffered by Americans. Much of Europe and Asia had been ravaged. From ashes and ruins and graveyards, new regimes gathered. In Latin America, Africa, and South Asia, nations and peoples that had been colonized by European powers, began to fight to secure their independence. They meant to choose their own political and economic arrangements. But, in a newly bipolar world, that generally meant choosing between democracy and authoritarianism, between capitalism and communism, between the influence of the United States or the influence of the USSR.31

“At the present moment in world history nearly every nation must choose between alternative ways of life,” Truman said. He conceived of a choice between freedom and oppression. Much about this conception derived from the history of the United States, a refiguring of the struggle between “freedom” and “slavery” that had divided nineteenth-century America into “free states” and “slave states” and during which opponents of slavery had sought to “contain” it by refusing to admit “slave states” into the Union. In the late 1940s, Americans began applying this rhetoric internationally, pursuing a policy of containing communism while defending the “free world.”32

The same rhetoric, of course, infused domestic politics. Republicans characterized the 1946 midterm elections as involving a stark choice: “Americanism vs. Communism.” In California, scrappy Richard Nixon defeated the diffident Voorhis by debating him on stage a half-dozen times, but especially by painting him as weak on communism and slaughtering him with innuendo and smear. Nixon adopted, in his first campaign, his signature tactic: making false claims and then taking umbrage when his opponent impugned his integrity. Voorhis was blindsided. “Every time that I would say that something wasn’t true,” he recalled, “the response was always ‘Voorhis is using unfair tactics by accusing Dick Nixon of lying.’” But Nixon, the lunch-bucket candidate, also exploited voters’ unease with a distant government run by Ivy League–educated bureaucrats; he found it took only the merest of gestures to convince voters that there was something un-American about people like Voorhis, people like them. His campaign motto: “Richard Nixon is one of us.”33

In November 1946, the GOP won both the House and Senate for the first time since 1932. The few Democrats who were elected, like Kennedy in Massachusetts, had sounded the same themes as Nixon: the United States was soft on communism. As freshmen congressmen, Kennedy and Nixon struck up an unlikely friendship while serving together on the House Education and Labor Committee. Nixon and his fellow Republicans supported a proposed Taft-Hartley Act, regulating the unions and prohibiting certain kinds of strikes and boycotts—an attempt to rein in the power of unions, whose membership had surged before the war, from three million in 1933 to more than ten million in 1941. After Pearl Harbor, the AFL and the CIO had promised to abstain from striking for the duration of the conflict and agreed to wage limits. As soon as the war ended, though, the strikes began. Some five million workers walked out in 1946 alone. Truman opposed Taft-Hartley, and, when Congress passed it, Truman vetoed it. Republicans in Congress began lining up votes for an override. Nixon and Kennedy went to a steel town in western Pennsylvania to debate the question before an audience of union leaders and businessmen. Each man admired the other’s style. On the train back to Washington, they shared a sleeping car. Kennedy’s halfhearted objections would, in any case, hold no sway against Republicans who succeeded in depicting unionism as creeping communism. Congress overrode the president’s veto.34

On foreign policy, Truman began to move to the right. Disavowing the legacy of American isolationism, he pledged that the nation would aid any besieged democracy. The immediate cause of this commitment was Britain’s decision to stop providing aid to Greece and Turkey, which were struggling against communism. In March of 1947, the president announced what came to be called the Truman Doctrine: the United States would “support free peoples who are resisting subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” (Truman aides later said that the president himself was unpersuaded by the growing fear of communism but was instead concerned about his chances for reelection. “The President didn’t attach fundamental importance to the so-called Communist scare,” one said. “He thought it was a lot of baloney.”) He also urged passage of the Marshall Plan, which provided billions of dollars in aid for rebuilding Western Europe. The Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan, the president liked to say, were “two halves of the same walnut.” Abroad, the United States would provide aid; at home, it would root out suspected communists. Coining a phrase, the financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch in April 1947 said in a speech in South Carolina, “We are today in the midst of a cold war.”35

Instead of a welfare state, the United States built a national security state. A peace dividend expected after the Allied victory in 1945 never came; instead came the fight to contain communism, unprecedented military spending, and a new military bureaucracy. During Senate hearings on the future of the national defense, military contractors including Lockheed, which had been an object of congressional investigation in the merchants-of-death era of the 1930s and had built tens of thousands of aircraft during the Second World War, argued that the nation required “adequate, continuous, and permanent” funding for military production, pressing not only for military expansion but also for federal government subsidies.36

In 1940, when Roosevelt pledged to make the United States an “arsenal of democracy,” he meant wartime production. A central political question of postwar American politics would become whether the arsenal was, in fact, compatible with democracy.

After the war, the United States committed itself to military supremacy in peacetime, not only through weapons manufacture and an expanded military but through new institutions. In 1946, the standing committees on military and naval affairs combined to become the Armed Services Committee. The 1947 National Security Act established the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency; created the position of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; and made the War Department, now housed for the first time in a building of its own, into the Department of Defense.

In this political climate, the “one world” vision of atomic scientists, along with the idea of civilian, international control of atomic power, faded fast. Henry Stimson urged the sharing of atomic secrets. “The chief lesson I have learned in a long life,” he said, “is the only way you can make a man trustworthy is to trust him; and the surest way you can make a man untrustworthy is to distrust him and to show your distrust.” Truman disagreed. Atomic secrets were to be kept secret, and the apparatus of espionage was to be deployed to ferret out scientists who might dissent from that view.37

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists began publishing a Doomsday Clock, an assessment of the time left before the world would be annihilated in an atomic war. In 1947, they set the clock at seven minutes before midnight. Kennan, in a top secret memo to Truman, warned that to use an atomic or hydrogen bomb would be to turn back time. These weapons, Kennan argued, “reach backward beyond the frontiers of western civilization”; “they cannot really be reconciled with a political purpose directed to shaping, rather than destroying, the lives of the adversary”; “they fail to take into account the ultimate responsibility of men for one another.”38

No caution slowed the development of the weapons program, and Soviet aggression and espionage, along with events in China, aided the case for national security and undercut the argument of anyone who attempted to oppose the military buildup. With every step of communist advance, the United States sought out new alliances, strengthened its defenses, and increased military spending. In 1948, the Soviet-supported Communist Party in Czechoslovakia staged a coup, the Soviets blockaded Berlin, Truman sent in support by air, and Congress passed a peacetime draft. The next year, the United States signed the North Atlantic Treaty, joining with Western Europe in a military alliance to establish, in NATO, a unified front against the USSR and any further Soviet aggression. Months later, the USSR tested its first atomic bomb and Chinese communists won a civil war. In December 1949, Mao Zedong, the chairman of China’s Communist Party, visited Moscow to form an alliance with Stalin; in January, Klaus Fuchs, a German émigré scientist who had worked on the Manhattan Project confessed that he was, in fact, a Soviet spy. Between 1949 and 1951, U.S. military spending tripled.39

The new spending restructured the American economy, nowhere more than in the South. By the middle of the 1950s, military spending made up close to three-quarters of the federal budget. A disproportionate amount of this spending went to southern states. The social welfare state hadn’t saved the South from its long economic decline, but the national security state did. Southern politicians courted federal government contracts for defense plants, research facilities, highways, and airports. The New South led the nation in aerospace and electronics. “Our economy is no longer agricultural,” the southern writer William Faulkner observed. “Our economy is the Federal Government.”40

Nixon staked his political future on becoming an instrument of the national security state. Keen to make a name for himself by ferreting out communist subversives, he gained a coveted spot on the House Un-American Activities Committee, where his early contributions included inviting the testimony of the actor Ronald Reagan, head of the Screen Actors Guild, a Californian two years Nixon’s junior. But Nixon’s real chance came when the committee sought the testimony of Time magazine senior editor and noted anticommunist Whittaker Chambers.

On August 3, 1948, Chambers, forty-seven, told the committee that, in the 1930s, he’d been a communist. Time, pressured to fire Chambers, refused, and published this statement: “TIME was fully aware of Chambers’ political background, believed in his conversion, and has never since had reason to doubt it.” But if Chambers’s past was no real surprise, his testimony nevertheless contained a bombshell: Chambers named as a fellow communist the distinguished veteran of the U.S. State Department, former general secretary of a United Nations organizing conference, and now president of the widely respected Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, forty-three-year-old Alger Hiss—news that, by the next morning, was splashed across the front of every newspaper in the country.

Hiss appeared before the committee on August 25 in a televised congressional hearing. He deftly denied the charges and seemed likely to be exonerated, especially after Chambers, who came across as unstable, vengeful, and possibly unhinged, admitted that he had been a Soviet spy (at that point, Time publisher Henry Luce accepted his resignation). Chambers having presented no evidence to support his charges against Hiss, the committee was inclined to let it pass—all but Nixon, who seemed to hold a particular animus for Hiss.41 Rumor had it that in a closed session, not seen on television, Nixon had asked Hiss to name his alma mater.

“Johns Hopkins and Harvard,” Hiss answered, and then added dryly, “And I believe your college is Whittier?”42

Nixon, who never forgave an Ivy League snub, began an exhaustive investigation, determined to catch his prey, the Sherlock Holmes to Hiss’s Professor Moriarty. Meanwhile, the press and the public forgot about Hiss and turned to the upcoming election, however unexciting it appeared. Hardly anyone expected Truman to win his first full term in 1948 against the Republican presidential nominee, Thomas Dewey, governor of New York. Few Americans were excited about either candidate, but Truman’s loss seemed all but inevitable. “We wish Mr. Dewey well without too much enthusiasm,” Reinhold Niebuhr said days before the election, “and look to Mr. Truman’s defeat without too much regret.”43

Truman had accomplished little of his domestic agenda, with one exception, which had the effect of alienating him from his own party: he had ordered the desegregation of the military. Aside from that, a Republican-controlled Congress had stymied nearly all of his legislative initiatives, including proposed labor reforms. Truman was so weak a candidate that two other Democrats ran against him on third-party tickets. Henry Wallace ran to Truman’s left, as the nominee of the Progressive Party. The New Republic ran an editorial with the headline TRUMAN SHOULD QUIT.44 At the Democratic convention in Philadelphia that summer, segregationists bolted: the entire Mississippi delegation and thirteen members of the Alabama delegation walked out, protesting Truman’s stand on civil rights. These southerners, known as Dixiecrats, formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party and ran a candidate to Truman’s right. They held a nominating convention in Birmingham during which Frank M. Dixon, a former governor of Alabama, said that Truman’s civil rights programs would “reduce us to the status of a mongrel, inferior race, mixed in blood, our Anglo-Saxon heritage a mockery.” The Dixiecrat platform rested on this statement: “We stand for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race.” As its candidate, the States’ Rights Party nominated South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond.45

Waving aside the challenges from Wallace and Thurmond, Truman campaigned vigorously against Dewey, running on his chief campaign pledge: a national health insurance plan. Dewey, on the other hand, proved about as good a campaigner as a pail of paint. From Kentucky, the Louisville Courier-Journal complained, “No presidential candidate in the future will be so inept that four of his major speeches can be boiled down to these historic four sentences. Agriculture is important. Our rivers are full of fish. You cannot have freedom without liberty. Our future lies ahead.”46

Truman might have felt that the crowds were rallying to him, but every major polling organization predicted that Dewey would defeat him. Truman liked to mock leaders who paid attention to polls. “I wonder how far Moses would have gone if he’d taken a poll in Egypt,” he said. “What would Jesus Christ have preached if he’d taken a poll in Israel?”47 The week before Election Day, George Gallup issued a statement: “We have never claimed infallibility, but next Tuesday the whole world will be able to see down to the last percentage point how good we are.”48 Gallup predicted that Truman would lose. The Chicago Tribune, crippled by a strike of typesetters, went to press with the headline DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN. A victorious Truman was caught on camera two days later, holding up the paper and wearing a grin as wide as the Mississippi River.

The 1948 election became a referendum on polling, a referendum with considerable consequences because Congress was still debating whether or not to establish a National Science Foundation, and whether such a foundation would provide funding to social science. The pollsters’ error likely had to do with undercounting black votes. Gallup routinely failed to poll black people, on the theory that Jim Crow, voter violence, intimidation, and poll taxes prevented most from voting. But blacks who could vote overwhelmingly cast their ballots for Truman, and probably won him the election.

That was hardly the only problem with the polling industry. In 1944, Gallup had underestimated Democratic support in two out of every three states; Democrats charged that he had engineered the poll to favor Republicans. Questioned by Congress, he’d weakly offered that, anticipating a low turnout, he had taken two points off the projected vote for FDR, more or less arbitrarily.49 Concerned that the federal government might institute regulatory measures, the polling industry had decided to regulate itself by establishing, in 1947, the American Association for Public Opinion Research. But the criticism had continued, especially from within universities, where scholars pointed out that polling was essentially a commercial activity, cloaked in the garb of social science.

The most stinging critiques came from University of Chicago sociologist Herbert Blumer and Columbia political scientist Lindsay Rogers. Public opinion polling is not a form of empirical inquiry, Blumer argued, since it skips over the crucial first step of any inquiry: identifying what it is that is to be studied. As Blumer pointed out, this is by no means surprising, since polling is a business, and an industry run by businessmen will create not a science but a product. Blumer argued that public opinion does not exist, absent its measurement; pollsters created it: “public opinion consists of what public opinion polls poll.” The very idea that a quantifiable public opinion exists, Blumer argued, rests on a series of false propositions. The opinions held by any given population are not formed as an aggregation of individual opinions, each given equal weight, as pollsters suppose; they are formed, instead, “as a function of a society in operation”; we come to hold and express the opinions that we hold and express in conversation and especially in debate with other people and groups, over time, and different people and groups influence us, and we them, in different degrees.50

Where Herbert Blumer argued that polling rested on a misunderstanding of empirical science, Lindsay Rogers argued that polling rested on a misunderstanding of American democracy. Rogers, a scholar of American political institutions, had started out as a journalist. In 1912, he reported on the Democratic National Convention; three years later, he earned a doctorate in political science from Johns Hopkins. In the 1930s, he’d served as an adviser to FDR. In 1949, in The Pollsters: Public Opinion, Politics, and Democratic Leadership, Rogers argued that he wasn’t sold on polling as an empirical science, but that neither was that his particular concern. “My criticisms of the polls go to questions more fundamental than imperfections in sampling methods or inaccuracy in predicting the results of elections,” he explained. Even if public opinion could be measured by adding up what people say in interviews over the telephone to people they’ve never met, legislators using this information to inform their votes in representative bodies would be inconsistent with the Constitution.

“Dr. Gallup wishes his polls to enable the United States to become a mammoth town meeting in which yeses and noes will suffice,” Rogers wrote. “He assumes that this can happen and that it will be desirable. Fortunately, both assumptions are wrong.” A town meeting has to be small; also, it requires a moderator. Decisions made in town meetings require deliberation and delay. People had said the radio would create a town meeting, too. It had not. “The radio permits the whole population of a country, indeed of the world, to listen to a speaker at the same time. But there is no gathering together. Those who listen are strangers to each other.” Nor—and here was Rogers’s key argument—would a national town meeting be desirable. The United States has a representative government for many reasons, but among them is that it is designed to protect the rights of minorities against the tyranny of majority opinion. But, as Rogers argued, “The pollsters have dismissed as irrelevant the kind of political society in which we live and which we, as citizens should endeavor to strengthen.” That political society requires participation, deliberation, representation, and leadership. And it requires that the government protect the rights of minorities.51

Blumer and Rogers offered these critiques before the DEWEY-BEATS-TRUMAN travesty. But after the election, the Social Science Research Council announced that it would begin an investigation. The council, an umbrella organization, brought together economists, anthropologists, historians, political scientists, psychologists, statisticians, and sociologists. Each of these social sciences had grown dependent on the social science survey, the same method used by commercial pollsters: they used weighted samples of larger wholes to measure attitudes and opinions. Many social scientists subscribed to rational choice theory. Newly aided by the power of computers, they used quantitative methods to search for a general theory that could account for the behavior of individuals. In 1948, political scientists at the University of Michigan founded what became the American National Election Survey, the largest, most ambitious, and most significant survey of American voters. Rogers didn’t object to this work, but he wasn’t persuaded that counting heads is the best way to study politics, and he believed that polling was bad for American democracy. Blumer thought pollsters misunderstood science. But what many other social scientists came to believe, after the disaster of the 1948 election, was that if the pollsters took a fall, social science would fall with them.

The Social Science Research Council warned, “Extended controversy regarding the pre-election polls among lay and professional groups might have extensive and unjustified repercussions upon all types of opinion and attitude studies and perhaps upon social science research generally.” Its report, issued in December 1948, concluded that pollsters, “led by false assumptions into believing their methods were much more accurate than in fact they are,” were not up to the task of predicting a presidential election, but that “the public should draw no inferences from pre-election forecasts that would disparage the accuracy or usefulness of properly conducted sampling surveys in fields in which the response does not involve expression of opinion or intention to act.” That is to say, the polling industry was unsound, but social science was perfectly sound.52

Despite social scientists’ spirited defense of their work, when the National Science Foundation was finally established in 1950, it did not include a social science division. Even before the founding of the NSF, the federal government had committed itself to fortifying the national security state by funding the physical sciences. By 1949, the Department of Defense and the Atomic Energy Commission represented 96 percent of all federal funds for university research in the physical sciences. Many scientists were concerned about the consequences for academic freedom. “It is essential that the trend toward military domination of our universities be reversed as speedily as possible,” two had warned. Cornell physicist Philip Morrison predicted that science under a national security state would become “narrow, national, and secret.”53 The founding of the NSF did not allay these concerns. Although the NSF’s budget, capped at $15 million, was a fraction of the funds provided to scientists engaged in military research (the Office of Naval Research alone had an annual research budget of $85 million), the price for receiving an NSF grant was being subjected to a loyalty test, surveillance, and ideological oversight, and agreeing to conduct closeted research. As the Federation of American Scientists put it, “The Foundation which will thus come into existence after 4 years of bitter struggle is a far cry from the hopes of many scientists.”54

Even without support from the National Science Foundation, of course, social science research proceeded. Political scientists applied survey methods to the study of American politics and relied on the results to make policy recommendations. In 1950, when the distance between the parties was smaller than it has been either before or since—and voters had a hard time figuring out which party was conservative and which liberal—the American Political Science Association’s Committee on Political Parties issued a report called “Toward a More Responsible Two-Party System.” The problem with American democracy, the committee argued, is that the parties are too alike, and too weak. The report recommended strengthening every element of the party system, from national leadership committees to congressional caucuses, as well as establishing a starker difference between party platforms. “If the two parties do not develop alternative programs that can be executed,” the committee warned, “the voter’s frustration and the mounting ambiguities of national policy might set in motion more extreme tendencies to the political left and the political right.”55

The recommendation of political scientists that American voters ought to become more partisan and more polarized did not sit well with everyone. In 1950, in a series of lectures at Princeton, Thomas Dewey, still reeling from his unexpected loss to Truman, damned scholars who “want to drive all moderates and liberals out of the Republican party and then have the remainder join forces with the conservative groups of the South. Then they would have everything neatly arranged, indeed. The Democratic party would be the liberal-to-radical party. The Republican party would be the conservative-to-reactionary party. The results would be neatly arranged, too. The Republicans would lose every election and the Democrats would win every election.”56

Exactly this kind of sorting did eventually come to pass, not to the favor of one party or the other but, instead, to the detriment of everyone. It may have been the brainchild of quantitative political scientists, but it was implemented by pollsters and political consultants, using computers to segment the electorate. The questions raised by Blumer and Rogers went unanswered. Any pollster might have predicted it: POLLSTERS DEFEAT SCHOLARS.

WHEN TRUMAN BEAT DEWEY, and not the reverse, and Democrats regained control of both houses, and long-eared Lyndon B. Johnson took a seat in the Senate, the American Medical Association panicked and telephoned the San Francisco offices of Campaigns, Inc. In a message to Congress shortly before his inauguration, Truman called for the passage of his national health insurance plan.

The AMA, knowing how stunningly Campaigns, Inc., had defeated Warren’s health care plan in California, decided to do exactly what the California Medical Association had done: retain Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter. The Washington Post suggested that maybe the AMA, at the hands of Whitaker and Baxter, ought to stop “whipping itself into a neurosis and attempting to terrorize the whole American public every time the Administration proposes a Welfare Department or a health program.” But the doctors’ association, undaunted, hired Whitaker and Baxter for a fee of $100,000 a year, with an annual budget of more than a million dollars. Campaigns, Inc., relocated to a new, national headquarters in Chicago, with a staff of thirty-seven. To defeat Truman’s proposal, they launched a “National Education Campaign.” The AMA raised $3.5 million, by assessing twenty-five dollars a year from its members. Whitaker and Baxter liked to talk about their work as “grass roots campaigning.” Not everyone was convinced. “Dear Sirs,” one doctor wrote them in 1949. “Is it 2½ or 3½ million dollars you have allotted for your ‘grass roots lobby’?”57

They started, as always, by drafting a Plan of Campaign. “This must be a campaign to arouse and alert the American people in every walk of life, until it generates a great public crusade and a fundamental fight for freedom,” it began. “Any other plan of action, in view of the drift towards socialization and despotism all over the world, would invite disaster.” Then, in an especially cunning maneuver, aimed, in part, at silencing the firm’s critics, Whitaker had hundreds of thousands of copies of their plan, “A Simplified Blueprint of the Campaign against Compulsory Health Insurance,” printed on blue paper—to remind Americans that what they ought to do was to buy Blue Cross and Blue Shield—and distributed it to reporters and editors and to every member of Congress.58

The “Simplified Blueprint” wasn’t their actual plan; a different Plan of Campaign circulated inside the office, in typescript, marked “CONFIDENTIAL:—NOT FOR PUBLICATION.” While the immediate objective of the campaign was to defeat Truman’s proposal, its long-term objective was “to put a permanent stop to the agitation for socialized medicine in this country by”:

(a) awakening the people to the danger of a politically-controlled, government-regulated health system;

(b) convincing the people . . . of the superior advantages of private medicine, as practiced in America, over the State-dominated medical systems of other countries;

(c) stimulating the growth of voluntary health insurance systems to take the economic shock out of illness and increase the availability of medical care to the American people.

As Whitaker and Baxter put it, “Basically, the issue is whether we are to remain a free Nation, in which the individual can work out his own destiny, or whether we are to take one of the final steps toward becoming a Socialist or Communist State. We have to paint the picture, in vivid verbiage that no one can misunderstand, of Germany, Russia—and finally, England.”59

They mailed leaflets, postcards, and letters across the country, though they were not always well met. “RECEIVED YOUR SCARE LETTER. AND HOW PITYFUL,” an angry pharmacist wrote from New York. “I DO HOPE PRESIDENT TRUMAN HAS HIS WAY. GOOD LUCK TO HIM.” Truman could have used some luck. Whitaker and Baxter’s campaign to defeat his national health insurance plan ended up costing the AMA nearly $5 million and took more than three years. But it worked.60

Truman was furious. As to what in his plan could possibly be construed as “socialized medicine,” he said, he didn’t know what in the Sam Hill that could be. He had one more thing to say: there was “nothing in this bill that came any closer to socialism than the payments the American Medical Association makes to the advertising firm of Whitaker and Baxter to misrepresent my health program.”61

National health insurance would have to wait for another president, another Congress, and another day. The fight would only get uglier.

III.

MOST POLITICAL CAREERS follow an arithmetic curve. Richard Nixon’s rise was exponential: elected to Congress at thirty-three, he won a Senate seat at thirty-six. Two years later, he would be elected vice president.

He had persisted in investigating Whittaker Chambers’s claim that Alger Hiss had been a communist. In a series of twists and turns worthy of a Hitchcock film—including microfilm hidden in a hollowed-out pumpkin on Chambers’s Maryland farm, the so-called Pumpkin Papers—Nixon charged that Hiss had been not only communist but, like Chambers, a Soviet spy.62

In January 1950, Hiss was convicted of perjury for denying that he had been a communist (the statute of limitations for espionage had expired) and sentenced to five years in prison. Five days after the verdict, on the twenty-sixth, Nixon delivered a four-hour speech on the floor of Congress, a lecture he called “The Hiss Case—A Lesson for the American People.” It read like an Arthur Conan Doyle story, recounting the entire history of the investigation, with Nixon as ace detective. Making a bid for a Senate seat, Nixon had the speech printed and mailed copies to California voters.63

Nixon sought the Senate seat of longtime California Democrat Sheridan Downey, the “Downey” of the “Uppie-and-Downey” EPIC gubernatorial ticket of 1933, who had decided not to run for reelection. Nixon defeated his opponent, Democrat Helen Gahagan Douglas, by Red-baiting and innuendo-dropping. Douglas, he said, was “Pink right down to her underwear.” The Nation’s Carey McWilliams said Nixon had “an astonishing capacity for petty malice.”64 But what won him the seat was the national reputation he’d earned in his prosecution of Alger Hiss, even if that crusade was soon taken over by a former heavyweight boxer who stood six foot tall and weighed two hundred pounds.

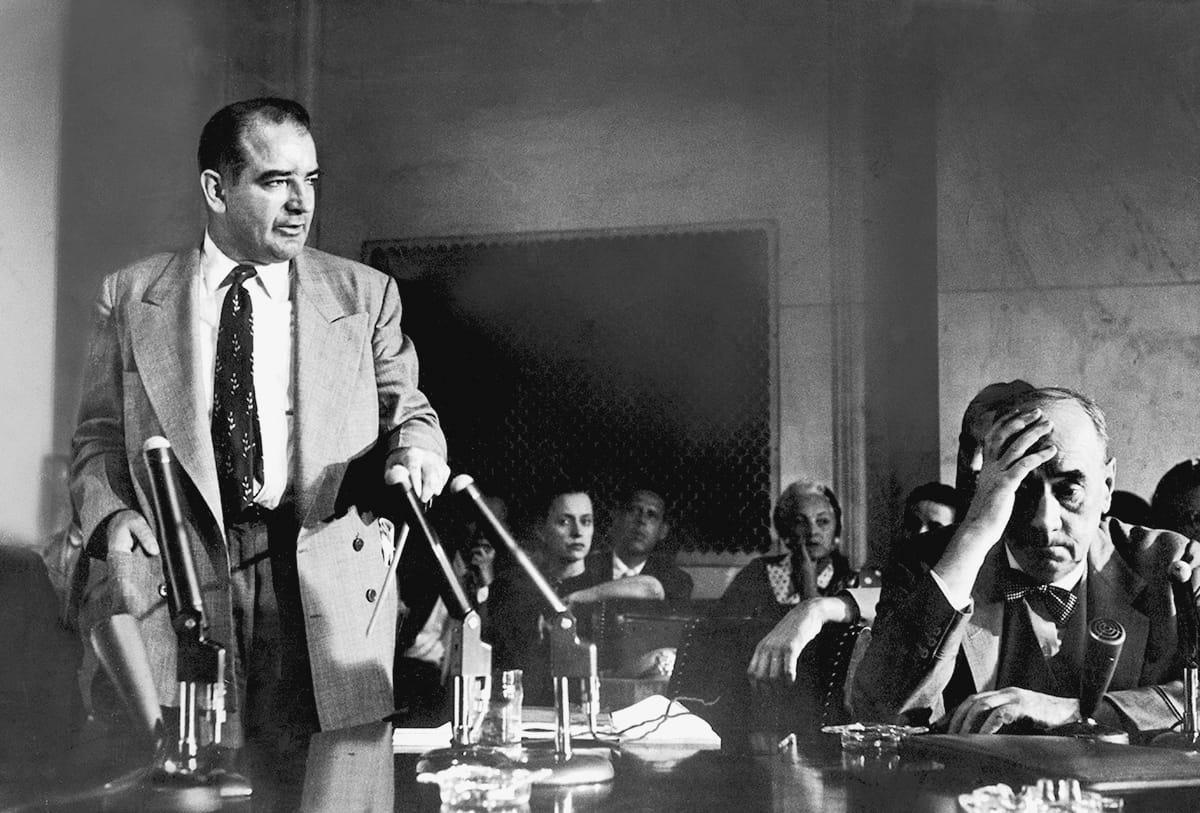

On February 9, a junior senator from Wisconsin named Joseph McCarthy stole whole paragraphs from Nixon’s “The Hiss Case—A Lesson for the American People” and used them in an address of his own, in which he claimed to have a list of subversives working for the State Department. In a nod to Nixon, McCarthy liked to say, when he was sniffing out a subversive: “I have found a pumpkin.”65

McCarthy had big hands and bushy eyebrows, and an unnerving stare. During the war, he’d served as a marine in the Pacific. Although he’d seen little combat and sustained an injury only during a hazing episode, he’d defeated the popular incumbent Robert La Follette Jr., in a 1946 Republican primary by running as a war hero, and had won a Senate seat against the Democrat, Howard McMurray, by claiming, falsely, that McMurray’s campaign was funded by communists, as if McMurray wore pink underwear, too.

The first years of McCarthy’s term in the Senate had been marked by failure and duplicity. Like Nixon, he tested the prevailing political winds and decided to make his mark by crusading against communism. In his Hiss speech, Nixon had hinted that not only Hiss but many other people in the State Department, and in other parts of the Truman administration, were part of a vast communist conspiracy. When McCarthy delivered his February 9 speech, before the Ohio County Republican Women’s Club, in Wheeling, West Virginia, he went further than Nixon. “While I cannot take the time to name all of the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party,” he said, “I have here in my hand a list of two hundred and five . . . names that were made known to the Secretary of State as members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department.”66 He had no list. He had nothing but imaginary pink underwear.

Three weeks after McCarthy’s Wheeling address, John Peurifoy, deputy undersecretary of state, said that while there weren’t any communists in the State Department, there were ninety-one men, homosexuals, who’d recently been fired because they were deemed to be “security risks” (another euphemism was men whose “habits make them especially vulnerable to blackmail”). It was, in part, Peurifoy’s statement that gave credibility to McCarthy’s charges: people really had been fired. One Republican representative from Illinois, getting the chronology all wrong, praised McCarthy for the purge: “He has forced the State Department to fire 91 sex perverts.”67

The purge had begun years earlier, in 1947, under the terms of a set of “security principles” provided to the secretary of state. People known for “habitual drunkenness, sexual perversion, moral turpitude, financial irresponsibility or criminal record” were to be fired or screened out of the hiring process. Thirty-one homosexuals had been fired from the State Department in 1947, twenty-eight in 1948, and thirty-one in 1949. A week after Peurifoy’s statement, Roy Blick, the ambitious head of the Washington, DC, vice squad, testified during classified hearings (on “the infiltration of subversives and moral perverts into the executive branch of the United States Government”) that there were five thousand homosexuals in Washington. Of these, Blick said, nearly four thousand worked for the federal government. The story was leaked to the press. Blick called for a national task force: “There is a need in this country for a central bureau for records of homosexuals and perverts of all types.”68

The Nixon-McCarthy campaign against communists can’t be separated from the campaign against homosexuals. There had been much intimation that Chambers, a gay man, had informed on Hiss because of a spurned romantic overture. By March of 1950, McCarthy’s charges had been reported in newspapers all over the country. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee convened hearings into “whether persons who are disloyal to the United States are or have been employed by the Department of State.” The hearings, chaired by Millard Tydings, a Democrat from Maryland, proved unilluminating. In the committee’s final report, Tydings called the charges “a fraud and a hoax.” This neither dimmed the furor nor daunted McCarthy, who masterfully manipulated the press and escalated fears of a worldwide communist conspiracy and a worldwide network of homosexuals, both trying to undermine “Americanism.” (So great was McCarthy’s hold on the electorate that, for challenging him, Tydings was defeated when he ran for reelection.)69

Who could rein him in? Few critics of McCarthyism were as forceful as Maine senator Margaret Chase Smith, the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress. In June 1950, she rose to speak on the floor of the Senate to deliver a speech later known as the Declaration of Conscience. “I don’t want to see the Republican Party ride to political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny—Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry, and Smear,” said Smith, a moderate Republican in the mold of Wendell Willkie. Bernard Baruch said that if a man had made that speech he would be the next president of the United States. Later, after Smith was jettisoned from the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, it was Nixon who took her place.70

In September 1950, Congress passed the Internal Security Act, over Truman’s veto, requiring communists to register with the attorney general and establishing a loyalty board to review federal employees. That fall, Margaret Chase Smith, who, despite her centrist leanings, had no qualms about the purging of homosexuals, joined North Carolina senator Clyde Hoey’s investigation into the “Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government.” The Hoey committee’s conclusion was that such men and women were a threat to national security.71

The crusade, at once against communists and homosexuals, was also a campaign against intellectuals in the federal government, derided as “eggheads.” The term, inspired by the balding Illinois Democrat Adlai Stevenson, was coined in 1952 by Louis Bromfield to describe “a person of spurious intellectual pretensions, often a professor or the protégé of a professor; fundamentally superficial, over-emotional and feminine in reactions to any problems.” The term connoted, as well, a vague homosexuality. One congressman described leftover New Dealers as “short-haired women and long-haired men messing into everybody’s personal affairs and lives.”72

One thing McCarthyism was not was a measured response to communism in the United States. Membership in the Communist Party in the United States was the lowest it had been since the 1920s. In 1950, when the population of the United States stood at 150 million, there were 43,000 party members; in 1951, there were only 32,000. The Communist Party was considerably stronger in, for instance, Italy, France, and Great Britain, but none of those nations experienced a Red Scare in the 1950s. In 1954, Winston Churchill, asked to establish a royal commission to investigate communism in Great Britain, refused.73

In 1951, McCarthy’s crusade scored a crucial legal victory when the Supreme Court upheld the Smith Act of 1940, ruling 6–2 in Dennis v. United States that First Amendment protections of free speech, press, and assembly did not extend to communists. This decision gave the Justice Department a free hand in rounding up communists, who could be convicted and sentenced to prison. In a pained dissent in Dennis, Justice Hugo Black wrote, “There is hope, however, that in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.” That calm did not come for a very long time. Instead, McCarthy’s imagined web of conspiracy grew bigger and stretched further. The Democratic Party itself, he said, was in the hands of men and women “who have bent to the whispered pleas from the lips of traitors.” William Jenner, Republican senator from Indiana, said, “Our only choice is to impeach President Truman and find out who is the secret invisible government.”74

Eggheads or not, Democrats failed to defeat McCarthyism. Lyndon Johnson had become the Democratic Party whip in 1950 and two years later its minority leader; the morning after the 1952 election, he’d called newly elected Democrats before sunrise to get their support. “The guy must never sleep,” said a bewildered John F. Kennedy. Johnson became famous for wrangling senators the way a cowboy wrangles cattle. He’d corner them in hallways and lean over them, giving them what a pair of newspaper columnists called “The Treatment.” “Its velocity was breathtaking, and it was all in one direction,” they wrote. “He moved in close, his face a scant millimeter from his target, his eyes widening and narrowing, his eyebrows rising and falling.” Johnson despised McCarthy. “Can’t tie his goddam shoes,” he said. But, lacking enough support to stop him, Johnson bided his time.75

Liberal intellectuals, refusing to recognize the right wing’s grip on the American imagination, tended to dismiss McCarthyism as an aberration, a strange eddy in a sea of liberalism. The historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., writing in 1949, argued that liberals, having been chastened by their earlier delusions about socialism and even Sovietism and their romantic attachment to the ordinary and the everyday, had found their way again to “the vital center” of American politics. Conservatives might be cranks and demagogues, they might have power and even radio programs, but, in the world of ideas, liberal thinkers believed, liberalism had virtually no opposition. “In the United States at this time, liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition,” insisted literary critic Lionel Trilling. “For it is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation.”76

This assessment was an error. McCarthyism wasn’t an eddy; it was part of a rising tide of American conservatism.77 Its leading thinkers were refugees from fascist or communist regimes. They opposed collectivism and centralized planning and celebrated personal liberty, individual rights, and the free market. Ayn Rand, born Alisa Rosenbaum, grew up in Bolshevik Russia, moved to the United States in 1926, and went to Hollywood to write screenplays, eventually turning to novels; The Fountainhead appeared in 1943 and Atlas Shrugged in 1957. Austrian-born Friedrich von Hayek, after nearly twenty years at the London School of Economics, began teaching at the University of Chicago in 1949 (in 1961, he moved to Germany). While engaged in vastly different projects, Hayek and Rand engaged in many of the same rhetorical moves as Whitaker and Baxter, who, like all the most effective Cold Warriors, reduced policy issues like health care coverage to a battle between freedom and slavery. Whitaker and Baxter’s rhetoric against Truman’s health care plan sounded the same notes as Hayek’s “road to serfdom.” The facts, Whitaker said in 1949, were these:

Hitler and Stalin and the socialist government of Great Britain all have used the opiate of socialized medicine to deaden the pain of lost liberty and lull the people into non-resistance. Old World contagion of compulsory health insurance, if allowed to spread to our New World, will mark the beginning of the end of free institutions in America. It will only be a question of time until the railroads, the steel mills, the power industry, the banks and the farming industry are nationalized.

To pass health care legislation would be to reduce America to a “slave state.”78

But perhaps the most influential of the new conservative intellectuals was Richard M. Weaver, a southerner who taught at the University of Chicago and whose complaint about modernity was that “facts” had replaced “truth.” Weaver’s Ideas Have Consequences (1948) rejected the idea of machine-driven progress—a point of view he labeled “hysterical optimism”—and argued that Western civilization had been in decline for centuries. Weaver dated the beginning of the decline to the fourteenth century and the denial that there exists a universal truth, a truth higher than man. “The denial of universals carries with it the denial of everything transcending experience,” Weaver wrote. “The denial of everything transcending experience means inevitably—though ways are found to hedge on this—the denial of truth.” The only way to answer the question “Are things getting better or are they getting worse?” is to discover whether modern man knows more or is wiser than his ancestors, Weaver argued. And his answer to this question was no. With the scientific revolution, “facts”—particular explanations for how the world works—had replaced “truth”—a general understanding of the meaning of its existence. More people could read, Weaver stipulated, but “in a society where expression is free and popularity is rewarded they read mostly that which debauches them and they are continuously exposed to manipulation by controllers of the printing machine.” Machines were for Weaver no measure of progress but instead “a splendid efflorescence of decay.” In place of distinction and hierarchy, Americans vaunted equality, a poor substitute.79

If Weaver was conservatism’s most serious thinker, nothing better marked the rising popular tide of the movement than the publication, in 1951, of William F. Buckley Jr.’s God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom,” in which Buckley expressed regret over the liberalism of the American university. Faculty, he said, preached anticapitalism, secularism, and collectivism. Buckley, the sixth of ten children, raised in a devout Catholic family, became a national celebrity, not least because of his extraordinary intellectual poise.