Fourteen

RIGHTS AND WRONGS

NIKITA KHRUSHCHEV, STOUT AND SWAGGERING BENEATH a wide-brimmed white hat, looked like a circus barker; Richard Nixon was dressed like an undertaker. “KNOCK THEM DEAD IN RUSSIA,” Nixon’s television adviser had cabled him. “THIS IS MOST IMPORTANT TRIP OF YOUR LIFE.”1

Nixon, forty-six, went to Moscow in the summer of 1959 eyeing a presidential bid as the unsteady leader of a faltering party. The Republicans had been badly drubbed in the 1958 midterm elections, losing forty-eight seats in the House and thirteen in the Senate, and Democrats had won both Senate seats in the new state of Alaska. Nixon, keen to take advantage of the spotlight of a televised meeting with the Soviet premier, wanted to deliver to Americans shaken by Sputnik a technological triumph, or, at the very least, a little machine-made political magic.

Nixon had traveled to Moscow to open an exhibition. The United States and the USSR, unable to launch rockets without risking mutually assured destruction, had agreed to stage a proxy battle of the merits of capitalism and communism. At the Soviet Exhibition of Science, Technology, and Culture, held at the New York Coliseum, the Russians put a space satellite on display alongside a gallery that housed a model Soviet apartment, its kitchen outfitted with a samovar. Its counterpart, the American National Exhibition, mounted inside a ten-acre pavilion in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park, answered with electric coffeepots, offering visitors a tour of American consumer goods, especially home appliances of the sort that manufacturers pledged would spare women the drudgery of housework. One American family man, exactly capturing the spirit of the thing, wrote Eisenhower that he had a better idea: “Why don’t you let a typical American family make up an exhibit?” He said he’d be happy to bring to Moscow everything anyone in the Soviet Union needed to understand “typical, living, honest to goodness, truthful and democratic loving Americans”: striped toothpaste, a Dairy Queen cone, frozen pink lemonade, a GI insurance policy, his set of golf clubs, the family’s 1959 Ford station wagon, and “Two plump daughters, ages 10 and 11 complete with hula hoops, Brownie and Girl Scout outfits, and a Monopoly set and polio shots.”2 The president did not take him up on the offer.

In Moscow, a grinning, dark-suited Nixon cut the ribbon to open the American exhibit alongside beaming, stripe-tied Khrushchev. Inside, they sparred over the rewards of capitalism and communism while touring galleries stocked with vacuum cleaners and dishwashers, robots and cake mixes, garbage disposals and frozen dinners, a showcase meant to display the American way of life—abundance, convenience, and choice. The bottles of Pepsi were free.

Stopping at a makeshift television stage, the two men fell into an argument, Khrushchev toying with Nixon like a bear playing with a fish.

“You must not be afraid of ideas,” the vice president scolded the premier.

Khrushchev laughed. “The time has passed when ideas scared us.” Nixon pointed out that color television and the video recording of their meeting—American inventions—would lead to great advantages in communication, and that even Khrushchev might learn something from American ingenuity. “Because after all,” Nixon said with a stiff smile, “you don’t know everything.”

“You know absolutely nothing about communism,” Khrushchev shot back. “Nothing except fear of it.”

Awkwardly, they wandered the exhibit hall.

“I want to show you this kitchen,” Nixon said, excitedly ushering the premier to a canary-yellow, appliance-filled room and calling his attention to a washing machine and a television.

“Do your people also have a machine that opens their mouth and chews for them?” Khrushchev prodded.

Nixon dodged and parried. Still, he stood his ground.

The press dubbed it the Kitchen Debate and declared it a draw, but American photographers captured Nixon standing tall and fighting back, poking a finger in Khrushchev’s chest, and the visit was a triumph.3 For the United States, it was, in any event, a triumphant time: at the height of the Cold War, more Americans were earning more, and buying more, than ever before.

The Affluent Society, the economist John Kenneth Galbraith called it in 1958. “The fundamental political problems of the industrial revolution have been solved,” the sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset wrote confidently in Political Man in 1960. For most of human history, the overwhelming majority of people have suffered from want. Industrialism had promised to end that suffering but turned out to produce vast fortunes only for the few, crushing the many under its wheels. Progressives and New Dealers had tried to lift those wheels. They’d legislated all manner of remedies and forms of mitigation, from a graduated federal income tax to maximum-hour and minimum-wage laws, from Social Security to the G.I. Bill. Since 1940, inequalities of wealth and income had been dwindling.4 Even while checked by the Constitution, the growing power of the state, exercised most dramatically in huge fiscal expenditures, especially military, and funded by a progressive income tax, made possible unprecedented economic growth and a wide distribution of goods and opportunities. By 1960, two out of three Americans owned their own homes. They filled those homes with machines: dishwashers, vacuum cleaners, electric mixers and blenders, refrigerators and freezers, record players, radios, and televisions, the engines of their own abundance. So high a standard of living, so widely distributed, had never been seen before. “Nearly all, throughout history, have been very poor,” Galbraith wrote. “The exception, almost insignificant in the whole span of human existence, has been the last few generations in the comparatively small corner of the world populated by Europeans. Here, and especially in the United States, there has been great and quite unprecedented affluence.”5

The economy a juggernaut, the triumph of liberalism and of Keynesian economics seemed, to many American intellectuals, all but complete. “The remarkable capacity of the United States economy in 1960,” one economic historian concluded, “represents the crossing of a great divide in the history of humanity.”6 Not only had the problems of industrialism been solved, many social scientists believed, but so had the problems of mass democracy, with the emergence of a broad and moderate political consensus, as seen on television. Notwithstanding the ongoing struggle over civil rights, Americans fundamentally agreed with one another about their system of government, and most also agreed on an underlying theory of politics. In The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties, sociologist Daniel Bell argued that socialism and communism had bloomed and withered; ideology, itself, was over. “For ideology, which once was a road to action, has come to be a dead end.” Political debates lay ahead, tinkering around the edges, repairs to the appliance of government, and certainly, in Asia and Africa, new ideologies had emerged. But in the West, Bell insisted, the big ideas of the Left had been exhausted, replaced by a consensus: “the acceptance of a Welfare State; the desirability of decentralized power; a system of mixed economy and of political pluralism.”7

Some younger Americans, Left and Right, found Bell’s argument ridiculous. “It’s like an old man proclaiming the end of sex,” said one. “Because he doesn’t feel it anymore, he thinks it has disappeared.”8 Others suggested that Bell had failed to notice a rising tide of conservatism.9 But Bell hadn’t ignored conservatism; he’d discounted it. In 1955, he’d edited a collection of essays called The New American Right. Joseph McCarthy, to Bell’s contributors, was a man without ideas. “The puzzling thing about McCarthy,” Dwight Macdonald wrote, “was that he had no ideology.” As for the writings of economists like Friedrich Hayek, Bell dismissed them as nonsense. “Few serious conservatives,” wrote Bell, “believe that the Welfare State is the ‘road to serfdom.’”10

Considerable empirical evidence in fact supported Bell’s theory of consensus. At the University of Michigan, political scientists had been conducting interviews with voters every four years since 1948. They’d asked voters questions: “Would you say that either one of the parties is more conservative or more liberal than the other?” Between 1948 and 1960, many voters could not answer that one. Others answered badly. The researchers had asked a follow-up: “What do people have in mind when they say that the Republicans (Democrats) are more conservative (liberal) than the Democrats (Republicans)?” Voters found this kind of question difficult to answer, too. The bottom 37 percent of respondents “could supply no meaning for the liberal-conservative distinction” and only the top 17 percent gave what the interviewers deemed “best answers.” Everyone else fell somewhere in between, but the researchers were pretty sure that a whole bunch of them were just guessing.11 Ideologically minded politicians and intellectuals talked about liberalism and conservatism, for sure, but to ordinary voters these terms had virtually no meaning.

Elaborating on these findings, which were published in 1960 in a landmark study called The American Voter, the political scientist Philip Converse produced an influential essay, “The Nature of Mass Belief Systems in Mass Publics,” in which he divided the American electorate into political elites and the mass public. Political elites are exceptionally well informed, follow politics closely, and adhere to a set of political beliefs so coherent—or, as Converse termed, so “constrained”—as to constitute an ideology. But the mass public has only a scant knowledge of politics, resulting in a very loose and unconstrained attachment to any single set of political beliefs. Converse argued that the Michigan voter interviews revealed that political elites know “what-goes-with-what” (laissez-faire with free enterprise, for example) and “what parties stand for” (Democrats favor labor; Republicans, business), but much of the mass public does not. Political elites vote in a more partisan fashion than the mass public: the more a voter knows about politics, the more likely he is to vote in an ideologically consistent way, not just following a party but following a set of constraints dictated by a political ideology. What makes a voter a moderate, Converse concluded, is not knowing very much about politics. In the 1950s, there were a lot of moderates.12

What no one could quite see, in 1960, was the gathering strength of two developments that would shape American politics for the next half century. Between 1968 and 1972, both economic inequality and political polarization, which had been declining for decades, began to rise. The fundamental problems of the Industrial Revolution had not, alas, been solved. Nor had the problems of mass democracy. Even as social scientists were announcing the end of ideology, a new age of ideology was beginning.

By 1974, when Richard Nixon announced his resignation from the presidency, sitting before blue drapes in the Oval Office, fifteen years after his debate with Nikita Khrushchev in the canary-yellow kitchen in Moscow, liberalism had begun its long decline, and conservatism its long ascent. And the country was on the way to becoming nearly as divided, and as unequal, as it had been before the Civil War.

I.

GALBRAITH WASN’T HAPPY about the affluent society. He found it complacent and smug, and too willing to accept poverty as inevitable. The prosperous society, he thought, was a purposeless one. He called for higher taxes to build better hospitals and schools and roads to repair the public sector. Americans shrugged, and turned on their televisions. But beneath the cheerful gurgle of the percolating electric coffeepot could be heard a muffled thrum of despair. It began with a fear of the perils of prosperity: laziness, tastelessness, and purposelessness. “We’ve grown unbelievably prosperous and we maunder along in a stupor of fat,” the historian Eric Goldman complained. One journalist called the 1950s “the age of the slob.” It was also the age of the snob. Dwight Macdonald memorably lamented the rise of packed, boxed, and price-tagged, middlebrow mass culture—“masscult,” he dubbed it, as if it were a soft drink—especially in the form of trashy paperback novels and ticky-tacky TV shows produced for the sprawling and suburban middle class by corporations, arbitrated not by taste but by sales and ratings. Art is the creation of individuals in communities, Macdonald argued; middlebrow culture is a product manufactured and packaged for the masses. “Masscult is bad in a new way,” Macdonald wrote. “It doesn’t even have the theoretical possibility of being good.”13

After Nixon came back from Moscow, the Eisenhower administration announced a new resolve: to discover a national purpose. “The year 1960 was a time when Americans stopped taking their national purpose for granted and started doing something about it,” Life reported. Eisenhower appointed ten eminent men—politicians and editors, business and labor leaders, and the presidents of universities and charities—to a Commission on National Goals, and asked the commission to identify a set of ten-year objectives for the United States. A striking measure of the artificial nature of the era’s liberal consensus: every member of the commission was a white man over the age of forty-five.14 Yet the goals the commission would set would be steered, above all, by black college students, who, beginning in 1960, and without a blue-ribbon committee of eminent men, made civil rights the nation’s purpose.

On Monday, February 1, 1960, two days before Eisenhower named the members of his Commission on National Goals, four freshmen from North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, North Carolina, refused to give up their seats at a lunch counter in a segregated diner inside a Woolworth’s store. Theirs wasn’t the first sit-in—over the past three years alone, there’d been sit-ins in sixteen cities—but it was the first to capture national attention. That night, those four students called NAACP lawyer Floyd McKissick, who helped spread the word. They went back to Woolworth’s the next day, with friends; more came the day after that. They sat in shifts, at vinyl-and-chrome stools. They set up a command center and kept track of plans being laid in Durham and Raleigh to stage sit-ins of solidarity. By the end of the week, more than four hundred students were involved in the Greensboro sit-in alone. The movement spread to Tennessee, and then across the South, to Georgia, West Virginia, Texas, and Arkansas. It reached forty more cities in March. Within months, fifty thousand students had joined. Hundreds were arrested in Nashville. In South Carolina, police attacked the demonstrators with teargas and fire hoses, arresting nearly four hundred. Even students who’d doubted the philosophy of nonviolent protest began to see its power, as photographers captured images of thuggish whites pouring milk and squeezing ketchup onto the heads of college students sitting quietly at a lunch counter, or of angry, armored policemen beating them with clubs or dragging them down sidewalks. The students’ protest even earned the admiration of some hardened pro-segregation southern newspaper editors, including the editor of the Richmond News Leader:

Here were the colored students, in coats, white shirts, ties, and one of them was reading Goethe and one was taking notes from a biology text. And here, on the sidewalk outside, was a gang of white boys come to heckle, a ragtail rabble, slack-jawed, black-jacketed, grinning fit to kill, and some of them, God save the mark, were waving the proud and honored flag of the Southern States in the last war fought by gentlemen. Eheu! it gives one pause.

Ella Baker, acting director of the SCLC, arranged to invite the student leaders to an organizing meeting on Easter weekend, in April. Baker, born in Virginia in 1903, had been a longtime organizer for the NAACP, as a field secretary beginning in 1938 and as a director of branches across the South in the 1940s, working on, among many other projects, the campaign to win equal pay for black teachers. She’d agreed to join the SCLC in 1958, to head an Atlanta-based voter registration drive known as the Crusade for Citizenship, but she’d been frustrated by southern preachers’ relative inattention to voting rights, and she found Martin Luther King Jr. “too self-centered and cautious.” In 1960, when SCLC tried to convince Baker to persuade the students to join as a junior chapter, Baker, in a stirring speech, refused, and instead urged the students to start their own organization. “She didn’t say, ‘Don’t let Martin Luther King tell you what to do,’” Julian Bond later recalled, “but you got the real feeling that that’s what she meant.” Distancing themselves from both the NAACP and the SCLC, which many students found altogether too conservative, they founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They raised an army; their weapon was nonviolent direct action. Baker left the SCLC to join them.15

Later in 1960, when Eisenhower’s ten distinguished commissioners delivered their report, they wrote that “Discrimination on the basis of race must be recognized as morally wrong, economically wasteful, and in many respects dangerous”; called for federal action to support voting rights; urged the denial of federal funds to employers who discriminate on the basis of race; and insisted upon the urgency of ending segregation in education.16 Although the final report wasn’t published until after the November election, its key findings were released earlier, and more than one observer remarked that the report, while prepared for the Republican White House, aligned very well with the campaign promises made by Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy. “If there were not abundant evidence Senator Kennedy has been fully occupied with other things lately,” said CBS’s Howard K. Smith, “one would swear he wrote the document.”17

Before that fall, the presidential prospects for Kennedy, the dashing Irish Catholic from Boston, had not seemed especially good. Liberals distrusted him because of his silence on McCarthyism, and few had much confidence in him. Kennedy, forty-three, was both young and inexperienced. Lyndon Johnson called him “the boy.”

Kennedy prevailed, in part, because he was the first packaged, market-tested president, liberalism for mass consumption. Weighing the possible party nominees and its platform, the Democratic National Committee, uncertain how to handle the question of civil rights, turned to a new field, called “data science,” a term coined in 1960, to predict the consequences of different approaches to the issue by undertaking the computational simulation of elections. To that end, the DNC in 1959 hired Simulmatics Corporation, a company founded by Ithiel de Sola Pool, a political scientist from MIT. Pool and his team collected old punch cards from the archives of George Gallup and pollster Elmo Roper, the raw data from more than sixty polls conducted during the campaigns of 1952, 1954, 1956, 1958, and 1960, and fed them into a UNIVAC. Using high-speed computation and “a simulation model developed out of historical data,” Pool aimed to both advance and accelerate the measurement of public opinion and the forecasting of elections. “This kind of research could not have been conducted ten years ago,” Pool and his colleagues reported.

Pool sorted voters into 480 possible types, explaining, “A single voter type might be ‘Eastern, metropolitan, lower-income, white, Catholic, female Democrats.’ Another might be, ‘Border state, rural, upper-income, white, Protestant, male Independents.’” He sorted issues into fifty-two clusters: “Most of these were political issues, such as foreign aid, attitudes toward the United Nations, and McCarthyism,” he explained. “Other so-called ‘issue clusters’ included such familiar indicators of public opinion as ‘Which party is better suited for people like you?’”18

Simulmatics’s work, which continued through the 1960s, marked the advent of a new industry whose implications for American democracy alarmed at least one of his colleagues, the political scientist and novelist Eugene Burdick. Famous for the 1958 best seller he coauthored with William Lederer, The Ugly American, and the 1962 novel Fail-Safe (written with Harvey Wheeler and made into a film directed by Sidney Lumet), Burdick published a novel called The 480, about the work done by Simulmatics, a fictional exposé of what he described as “a benign underworld in American politics”:

It is not the underworld of cigar-chewing pot-bellied officials who mysteriously run “the machine.” Such men are still around, but their power is waning. They are becoming obsolete though they have not yet learned that fact. The new underworld is made up of innocent and well-intentioned people who work with slide rules and calculating machines and computers which can retain an almost infinite number of bits of information as well as sort, categorize, and reproduce this information at the press of a button. Most of these people are highly educated, many of them are Ph.D.s, and none that I have met have malignant political designs on the American public. They may, however, radically reconstruct the American political system, build a new politics, and even modify revered and venerable American institutions—facts of which they are blissfully innocent. They are technicians and artists; all of them want, desperately, to be scientists.19

The premise of Simulmatics’s work, as Burdick saw all too clearly, was that, if voters didn’t profess ideologies, if they had no idea of the meaning of the words “liberal” and “conservative,” they could nevertheless be sorted into ideological piles, based on their identities—race, ethnicity, hometown, religion, age, and income. Simulmatics’s first commission, completed just before the Democratic National Convention, in the summer of 1960, was to conduct a study on “the Negro vote in the North” (so few black people were able to vote in the South that there was no point in simulating their votes, Pool concluded). Pool reported discovering that, between 1954 and 1956, “A small but significant shift to the Republicans occurred among Northern Negroes, which cost the Democrats about 1 per cent of the total votes in 8 key states.” The DNC, undoubtedly influenced by the viscerally powerful student sit-ins, absorbed Simulmatics’s report, and decided to add civil rights paragraphs to the party’s platform at its convention in Los Angeles in July.20

Civil rights had not been among Kennedy’s priorities as a member of the Senate. But the protests and the predictions altered his course. Needing to win both black votes in the North and white votes in the South, Kennedy decided to run as a civil rights candidate, to woo those northerners, and chose Lyndon Johnson for his running mate, hoping that the Texan could handle the southerners.

The DNC found Simulmatics’s initial report sufficiently illuminating that, after the convention, it commissioned Pool to prepare three more reports: on Kennedy’s image, on Nixon’s image, and on foreign policy as a campaign issue. Simulmatics also ran simulations on different ways Kennedy might talk about his Catholicism. He ought to employ “frankness and directness rather than avoidance,” Simulmatics advised.21 Kennedy therefore gave a frank and direct speech in Houston on September 12, 1960: “I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute—where no Catholic prelate would tell the President (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote.”22

Meanwhile, Nixon, without much help from Eisenhower, who snubbed him, won the Republican nomination. Campaigns, Inc., ran his campaign in California. “The great need is to go on the offensive—and to attack,” according to the firm’s Plan of Campaign, which advised Nixon to forget “the liberal Democrats who wouldn’t vote for Nixon if he received the joint personal endorsement of Jesus Christ and Karl Marx via a séance with Eleanor Roosevelt.” In the spirit of going on the offensive, Nixon agreed to debate Kennedy on television, in a series of exchanges. “I would like to propose that we transform our circus-atmosphere presidential campaign into a great debate conducted in full view of all the people,” Adlai Stevenson had urged in 1959. But it was Kennedy—a man one notable columnist called “Stevenson with balls”—who made it happen.23

On September 26, 1960, Nixon and Kennedy met in a bare CBS television studio in Chicago, without an audience; the event was broadcast live by CBS, NBC, and ABC. By now, nearly nine in ten American households had a television set. Nixon was sick; he’d been in the hospital for twelve days. He was in pain. And he was unprepared. A skilled debater who’d enjoyed nothing but political gain from his appearances on television, and, most lately, from the Kitchen Debate, he’d barely been briefed for his appearance with Kennedy.24

The rules were the result of strenuous negotiating. The very scheduling required Congress to temporarily suspend an FCC regulation that required giving equal time to all presidential candidates (there were hundreds). Much negotiation involved seemingly little things. Nixon wanted no reaction shots; he wanted viewers to see only the fellow who was talking, not the other guy. But Kennedy wanted them, and Kennedy prevailed, with this concession: he agreed to Nixon’s stipulation that neither man be shown wiping the sweat from his face. Then there were bigger things. Each candidate made an eight-minute opening statement and a three-minute closing statement. The networks wanted Nixon and Kennedy to question each other; both men refused and instead insisted on taking questions from a panel of reporters, one from each network, a format that is more generally known as a parallel press conference. ABC refused to call what happened that night a “debate,” billing it instead as a “joint appearance.” Everyone else called it a debate, sixty-six million Americans watched Nixon scowl, and the misnomer stuck.25

On October 19, two days before the last of the candidates’ four scheduled debates, Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in Atlanta during a lunch counter sit-in. He’d waited a long time before joining the sit-ins. But now he was in, and he was sentenced to four months of hard labor. Kennedy called King’s wife, Coretta Scott King. His brother Robert intervened, and got King out of jail. Nixon, who had a much stronger record on civil rights than Kennedy, did nothing. He later came to believe that this lost him the election, one of the closest elections in American history, Kennedy winning by a hairsbreadth, 34,221,000 to 34,108, 000.

Nixon came to believe that the result had been rigged, and he may have been right; there appears to have been Democratic voter fraud in Illinois and Texas. Thirteen-year-old Young Republican Hillary Rodham volunteered to look for evidence of fraud in Chicago. “We won, but they stole it from us,” Nixon said.26

Nixon blamed Democrats. He blamed black voters. And, above all, he blamed the press.

II.

THE YOUNGEST MAN ever elected president, John F. Kennedy replaced the oldest man ever to hold the office. With his hand resting on a Bible carried across the ocean by his Irish immigrant ancestors, Kennedy looked more like a Hollywood movie star than like any man who had ever occupied the Oval Office. Wearing no overcoat, his every exhale visible in the freezing cold, he proclaimed his inauguration, on January 21, 1961, to mark the beginning of a new era: “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage.”27

Kennedy had taken that torch from Eisenhower. Three days before the inauguration, Eisenhower had delivered a farewell address in which he issued a dire warning about the U.S.-Soviet arms race. “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” he said. “Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.” Kennedy, in his inaugural address, echoed his predecessor: “Neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course—both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind’s final war.”28

One of the first acts of his administration was the announcement of the Peace Corps, in March 1961. But during a presidency that began with hope and ended with tragedy, Kennedy set the nation on a path not to peace but to war. In the world-stage struggle between communism and capitalism, Kennedy was determined to win over third world countries that remained, even if only nominally, uncommitted.29

In 1951, eyeing a run for the Senate, Kennedy and his brother Bobby had made a seven-week tour of Asia and the Middle East, stopping in Vietnam. Long colonized by the French and occupied by the Japanese beginning in 1940, Vietnam, led by the Communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh—the man who’d tried to meet with Wilson at the Paris Peace conference in 1919—had declared its independence at the end of the Second World War, but France had launched a campaign to restore colonial rule. The United States viewed the spread of communism in Southeast Asia with alarm, chiefly for ideological reasons, but geopolitical and economic factors played a role, too. China and the USSR were plainly in the best position to exert influence in Southeast Asia, with its population of 170 million, but every Southeast Asian country that became part of the communist bloc threatened a loss of trade for Japan, which had already lost its trading relationship with China, its largest trading partner. The United States, attempting to exert its own influence in the region, redirected its foreign aid from Europe to Asia and Africa. Between 1949 and 1952, three-quarters of American aid went to Europe; between 1953 and 1957, three-quarters went to the third world; by 1962, nine-tenths did. When Indochina began attempting to overthrow French colonial rule, the United States supported France. The United States had been much admired after the war because of FDR’s staunch opposition to colonialism; its aid to France led to growing anti-Americanism. France lost the war in 1954. A treaty divided independent Vietnam at the seventeenth parallel; Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Party came to power in the North and U.S.-backed Catholic nationalist Ngo Dinh Diem in the South. Beginning in 1955, South Vietnam became the site of the largest state-building experiment in the world, training a police force and civil servants, building bridges, roads, and hospitals, under the advice of the Michigan State University Vietnam Advisory Group.30

In 1958, Kennedy was among a group of senators who handed out to every colleague a copy of Burdick and Lederer’s The Ugly American, which told the story of American diplomats and military men stationed in the fictional Asian country of Sarkhan, lost in a mire of misunderstanding and failure. In a factual epilogue, Lederer and Burdick reported “a rising tide of anti-Americanism” around the world arguing that the United States could hardly hope to wield political influence when, for one thing, American ambassadors to Asia did not speak the language. “In the whole of the Arabic world—nine nations—only two ambassadors have language qualifications. In Japan, Korea, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and elsewhere, our ambassadors must speak and be spoken to through interpreters.”31

Notwithstanding Burdick and Lederer’s caution, the U.S. government escalated its involvement when, by the late 1950s, a communist insurgency had begun in the South. Many people in Vietnam viewed the 1,500 American researchers and advisers in South Vietnam as an early signal that the United States hoped to place Vietnam under its own colonial rule, even though, by 1960, the American military presence consisted of only 685 American troops.32

Kennedy understood Vietnam through the lens of modernization schemes endorsed by intellectuals and above all by MIT’s Walt Rostow, whose Stages of Economic Growth (1960) helped convince Kennedy to commit more resources to Vietnam. Rostow’s MIT friend and colleague Ithiel de Sola Pool, having helped get Kennedy elected, turned to the project of using the tools of Simulmatics to help modernize South Vietnam. Convinced that, with enough data, a computer could simulate an entire social and political system, Pool would eventually earn a $24 million contract from ARPA for a multiyear research project in Vietnam.33 “Modernizing” South Vietnam meant building roads and airstrips. But guaranteeing the security of those roads and airstrips required sending and training soldiers, because the South Vietnamese were engaged in a war with North Vietnam. By the end of 1963, after Ngo Dinh Diem was murdered in a U.S.-sanctioned coup only three weeks before Kennedy was assassinated, 16,000 American troops were stationed in Vietnam. Eventually, winning the war became the mission.34

Meanwhile, Kennedy’s administration came close to deploying a nuclear weapon in a nearly catastrophic confrontation with Cuba. Eisenhower’s administration had developed a plan by which the United States would support an invasion of Cuba by forces opposed to Fidel Castro. Kennedy approved the plan, but in April 1961, Castro’s army destroyed the forces that came ashore at the Bay of Pigs. The following summer, American U2s flying over Cuba detected ballistic missiles capable of reaching the United States. They’d been sent by Khrushchev, the latest move in the worldwide Cold War game of chess. On October 22, 1962, in a televised address, Kennedy revealed the existence of the missiles and argued for action. “The 1930s taught us a clear lesson,” he said, “aggressive conduct, if allowed to go unchecked and unchallenged, ultimately leads to war.” The navy would quarantine Cuba. “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” Two days later, sixteen of nineteen Soviet ships headed for the American naval blockade turned back. The Soviet premier then sent the White House two entirely different messages: one promising that it would withdraw its missiles from Cuba if the United States would end the blockade; the other saying something sterner. Urged by his advisers to ignore the second message, Kennedy responded to the first message. Khrushchev agreed to withdraw the missiles.35

As ever, Cold War confrontations abroad formed the backdrop for civil rights battles at home. To test the U.S. government’s guarantee of desegregation in interstate transit, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sent thirteen trained volunteers, seven blacks and six whites—the Freedom Riders—to ride two buses into and across the Deep South. The riders were mostly students, like John Lewis, a theology student, who, although determined to finish his education, explained that “at this time, human dignity is the most important thing in my life.” They left Washington, DC, on May 4. Two days later, thirty-five-year-old Robert Kennedy, the president’s brother, gave his first public address as attorney general, at the University of Georgia, throwing down a gauntlet to segregationists. “We will move. . . . You may ask, will we enforce the Civil Rights statutes. The answer is: ‘Yes, we will.’”36

That promise was soon challenged. Eight days later, in Anniston, Alabama, a white mob attacked the Greyhound bus on which one group of the Freedom Riders had been riding, shattering the windows, slashing the tires, and, finally, burning it. “Let’s burn them alive,” the mob cried. The riders barely escaped with their lives. A Klan posse was waiting for the second bus when it arrived at a Trailways station in Birmingham. Robert Kennedy ordered that the riders, badly beaten, be evacuated. But CORE decided to send in more riders—students from Nashville. Birmingham police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor had his troops meet them at the bus station and put them in jail before they could board the bus—there they were held, without having been charged—while the State of Alabama dared the federal government to act.

“As you know, the situation is getting worse in Alabama,” the attorney general reported to the president. He convinced the president to call the governor of Alabama, Democrat John Patterson, who’d supported JFK’s campaign in 1960. But Patterson, in a shocking act of defiance, refused to take the call. Before he’d become governor, Patterson, as the state’s attorney general, had sought to block the NAACP from doing business; in 1958, he’d won the governor’s office with the support of the KKK. Robert Kennedy sent an envoy to Montgomery to meet with the governor. “There’s nobody in the whole country that’s got the spine to stick up to the goddamned niggers except me,” Patterson said to the man from the U.S. Justice Department. Told that if the state would not protect the riders, the president would send in federal troops, the governor reluctantly agreed to provide a police escort for the bus on its trip from Birmingham to Montgomery. But when the bus reached the station in Montgomery, another mob was waiting. John Lewis, the first off the bus, began speaking to a crowd of reporters and photographers, only to pause. “It doesn’t look right,” he whispered to another rider. Vigilantes hidden in the station emerged and began pummeling the press and setting upon the riders, attacking them with pipes, slugging them with fists, braining them with their own suitcases. When the badly beaten and bandaged Freedom Riders and 1,500 blacks met at the First Baptist Church, next to the Alabama State Capitol, to decide what to do next, 3,000 whites surrounded the church, eventually to be dispersed by the Alabama National Guard. The Freedom Riders decided to keep on, and rode all summer long.37

Even as 400 Freedom Riders were arrested in Mississippi, and schoolchildren across the South were beaten at the doors of elementary schools, CORE and SNCC and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council continued to press for integration, pursuing a strategy of nonviolence, but they had to answer, more and more, to activists who favored separation and were willing to use force. Elijah Muhammad, the founder and prophet of the Nation of Islam, a Muslim movement begun in Detroit in the 1930s, had called for a black state. His most eloquent disciple, Malcolm X, had been criticizing King since the mid-1950s. He soon gained a new audience.

Malcolm Little, who’d left a juvenile home in Michigan in 1941 to move in with his half-sister in Boston, had been arrested for armed robbery in 1945, when he was twenty. During his six years in prison, he converted to Islam, studied Greek and Latin, and learned how to debate. “Once my feet got wet,” he said, “I was gone on debating.”38 Paroled in 1952, he’d gotten a department store job in Detroit and become one of Elijah Muhammad’s most talented and devoted followers. Lecturing in Detroit in 1957, he’d drawn crowds 4,000 strong, and, disobeying a Nation of Islam directive not to talk about electoral politics (or even to register to vote), he’d asked, “What would the role and the position of the Negro be if he had a full voting voice?” He’d also drawn the attention of the press, having been featured in The Hate That Hate Produced, a five-part 1959 documentary narrated by CBS News’s Mike Wallace and reported by the African American television journalist Louis Lomax. (Appalled by the documentary, which he considered delusional to the point of inciting hysteria, Malcolm X compared it to Orson Welles’s 1938 adaptation of The War of the Worlds.) In the early 1960s, in a series of college-sponsored debates, Malcolm X had taken on integrationists. In 1961, as the Nation of Islam’s national spokesman, he debated Bayard Rustin at Howard University and James Farmer, the head of CORE, at Cornell. Farmer, who had spent forty days in jail during the Freedom Ride campaign, insisted on the importance of nonviolent struggle. But Malcolm X had little use for SNCC, CORE, and least of all, SCLC. “Anybody can sit,” he liked to say. “It takes a man to stand.”39

He first reached a national audience in 1962, after police in Los Angeles gunned down seven black Muslims, members of Mosque No. 27—a mosque Malcolm X had organized in the 1950s—who were loading dry cleaning into a car. Ronald X Stokes, a Korean war veteran, was shot with both hands raised. Malcolm X, speaking at a rally, framed the killings in racial, not religious, terms. “It’s not a Muslim fight,” he said. “It’s a black man’s fight.”40

Many in the black community called for armed self-defense, the argument of Negroes with Guns, published in 1962. King, preaching Christianity and a sanctified democracy, lamented that black Muslims had “lost faith in America.” Meanwhile, white moderates urged SNCC, CORE, and SCLC to slow down. In one poll, 74 percent of whites, but only 3 percent of blacks, agreed with the statement “Negroes are moving too fast.”41

In April 1963, King led a protest in Birmingham, part of a long-planned campaign in the most violent city in the South. Of the more than two hundred black churches and homes that had been bombed in the South since 1948, more bombs had gone off in Birmingham than in any other city. King had gone to Birmingham to get arrested, but found that support for his planned protest had ebbed. After white liberal clergymen denounced him in the Birmingham News, calling the protests “untimely,” King wrote a letter from jail, in solitary confinement. He began writing in the margins of the newspaper, adding passages on slips of paper smuggled in by visitors. In the end, the letter reached twenty pages, a soaring piece of American political rhetoric, testament to the urgency of a cause.

“Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, ‘Wait,’” he conceded, “but when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society . . . then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.”42

George Wallace, Alabama’s new governor, more or less answered that King would have to wait until hell froze. In June, Wallace said that if black students tried to enter the campus of the state university in Tuscaloosa, he’d block the door himself.

Wallace, forty-three, ate politics for breakfast, lunch, and dinner; he slept politics and he breathed politics and he smoked politics. He’d been a page in the state senate in 1935, when he was sixteen. At the University of Alabama, he’d been both a star boxer and class president. After studying law, he’d served as an airman in the Pacific during the war. He ran for state congress in 1946, the same year Nixon and Kennedy won seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. A loyal southerner, he’d never been a particularly ardent segregationist. As an alternate at the 1948 Democratic convention, he’d refused to bolt with the rest of the Dixiecrats. He’d endorsed Stevenson. But in 1958, running for governor with “Win with Wallace” as his motto, flanked by Confederate flags, he’d lost the Democratic primary to Patterson, who was more ardently opposed to desegregation; and, as the story goes, Wallace had pledged to his supporters, “No other son of a bitch will ever out-nigger me again.” In 1962, with a speechwriter who doubled as an organizer for the KKK, Wallace had won the governorship, with 96 percent of the vote. In his inaugural in Montgomery, delivered a week before Kennedy was inaugurated in Washington, Wallace stood in the shadow of a statue of the president of the Confederacy, who’d been sworn in on that very spot. “Today I have stood, where once Jefferson Davis stood, and took an oath to my people,” Wallace shouted. “And I say, segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” He’d followed by meeting with educational leaders in the state and telling them: “If you agree to integrate your schools, there won’t be enough state troopers to protect you.” In May, when Kennedy celebrated his birthday, his staff gave him a pair of boxing gloves, for his upcoming bout with the heavyweight from Alabama.43 But when the day came, on June 11, Wallace gave in only three hours after the arrival of the National Guard.

That afternoon, King telegrammed Kennedy that “the Negro’s endurance may be at the breaking point.” Kennedy, who had been deliberating for months, went to Congress to meet with House members. He decided the time had come to speak to the public. On television that night, he addressed the nation: “If an American, because his skin is dark, cannot eat lunch in a restaurant open to the public; if he cannot send his children to the best public school available; if he cannot vote for the public officials who represent him; if, in short, he cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color of his skin changed and stand in his place?” He talked about military service. “When Americans are sent to Viet-Nam or West Berlin, we do not ask for whites only.” He invoked history. “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free.” And he asked Congress for new civil rights legislation.44 One hundred years had been too long. No longer would Kennedy counsel patience.

To mark the one hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, Bayard Rustin had been charged with planning a March on Washington, scheduled for August 1963. The Kennedy administration, worried about violence, had arranged for military troops to be kept on alert. The District of Columbia had canceled two Washington Senators baseball games. Some 300,000—the largest crowd ever gathered between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument—assembled on a cloudless summer’s day, “this sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent,” King called it. They came by bus and train and subway. One young man roller-skated all the way from Chicago, wearing a sash that read “Freedom.” But Rustin had organized the march flawlessly and, by the time it was over, there would be only four march-related arrests; all the arrested were white.45

SNCC chairman John Lewis, earnest and only twenty-three, approached the microphone on the makeshift stage on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. He said he supported the proposed civil rights bill but with great reservations, because there was so much that the federal government had failed to do at every turn. The crowd stirred each time he spoke his speech’s refrain: “What did the federal government do?”

Television stations that had cut away from earlier speeches resumed coverage when Martin Luther King rose to the stage. It was the first time most Americans had seen King deliver an entire speech. It was the first time that President Kennedy had ever seen King deliver an entire speech.46

He began by welcoming “the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of the nation,” honoring Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, and condemning “the manacles of segregation and the chain of discrimination” that still shackled blacks one hundred years later. He spoke slowly and solemnly and formally. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were promissory notes, he said, a promise that all men would be guaranteed their rights. “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note.” It was stock stuff, delivered sternly, and loaded with sorrow. He cautioned the movement about the dangers of the “marvelous new militancy,” the loss of the support of whites. He listed grievances. Ten minutes into the speech, his voice rising, he said, “We are not satisfied and will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” He looked down at the cumbersome next lines of his speech—“And so today, let us go back to our communities as members of the international association for the advancement of creative dissatisfaction”—and left them unsaid. Instead, he began to preach. Mahalia Jackson, behind him on the platform, called out “Tell ’em about the dream, Martin.” He paused, for an instant. “I still have a dream,” he said. “It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’” He found his rhythm, and the depth of his voice, and the spirit of Scripture. “I have a dream today,” he said, shaking his head. “I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted.” The crowd rose, and bowed their heads, and wept. “Let freedom ring!” he cried.47 It was as if every bell in every tower in every city and town and village had rung: a toll of justice.

III.

THREE MONTHS LATER, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Less than five years after that, King himself would be shot and killed in Memphis. By then, the dreams of American liberals had been felled in a hail of bullets and a trail of napalm bombs that rained down on the world from the streets of Newark and Detroit to the rice paddies of South Vietnam.

The long arc of American liberalism that began with the inauguration of FDR in 1933 reached its peak, and began its decline, during the administration of LBJ. Roosevelt pursued a New Deal; Truman promised a Fair Deal; Johnson talked about a Better Deal until he decided that made him sound like a footnote. He aimed for nothing less than a Great Society. A great society was more than an affluent society; it was also a good society, “a place where men are more concerned with the quality of their goals than the quantity of their goods.” Said the president, “The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time.”48

The day after Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson met with Walter Heller, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, and told him that, contrary to his reputation as a conservative, he was not one. “If you look at my record, you would know I’m a Roosevelt New Dealer. As a matter of fact, to tell the truth, John F. Kennedy was a little too conservative to suit my taste.” In his first address to Congress, on November 27, 1963, he urged action on civil rights. “We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights,” he said. “We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time now to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law.” Johnson always said his slogan was “He gets things done.” He wanted to further Kennedy’s agenda, and he had his own agenda, an “unconditional war on poverty,” which he announced in his first State of the Union address, in January 1964.49

Johnson once told reporters, “When I was young, poverty was so common that we didn’t know it had a name.” But, as Galbraith had pointed out in The Affluent Society, poverty hadn’t been eradicated; it had only been forgotten. “Few things are more evident in modern social history than the decline of interest in inequality as an economic issue,” Galbraith wrote. “Inequality has ceased to preoccupy men’s minds.” Some of the poor were far away from the cities and the suburbs: one-fourth of those who lived below the “poverty line” worked on farms. In the Kennedy administration, the War on Poverty had its origins in January 1963, after Kennedy read a long essay by Dwight Macdonald in The New Yorker, “Our Invisible Poor.” No piece of prose did more to make plain the atrocity of poverty in an age of affluence. Prosperity, Macdonald argued, had left the nation both blinded to the plight of the poor and indifferent to their suffering. “There is a monotony about the injustices suffered by the poor that perhaps accounts for the lack of interest the rest of society shows in them,” Macdonald wrote, in a scathing indictment of the attitude of the American middle class toward those less well off. “Everything seems to go wrong with them. They never win. It’s just boring.”50

Heller had given Kennedy a copy of Macdonald’s article. In February 1963, the entire text of the article had been entered into the Congressional Record. Johnson, leveraging the nation’s sympathy for the martyred president, pressed Congress for legislation. The next year, he signed the Economic Opportunity Act and the Food Stamp Act. He believed poverty would be eradicated within a decade.

He had more ambitions, too. Wrangling congressmen like cattle, as ever, he secured passage of the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; gave the attorney general power to enforce desegregation; allowed for civil rights cases to move from state to federal courts; and expanded the Civil Rights Commission. “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long,” Johnson said, in a canny piece of political rhetoric.51

Both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X went to Washington to watch the congressional debates over the civil rights bill, a rare bringing together of the two men. Malcolm X had fallen out with the leadership of the Nation of Islam. He’d mocked the August 1963 March on Washington but, disobeying the explicit orders of Elijah Muhammad, had attended anyway. In December, he’d answered reporters who asked him to comment on Kennedy’s assassination—despite specific instructions from Muhammad not to speak on the subject. He said Kennedy’s assassination sounded to him like “chickens coming home to roost.” In the ensuing controversy, Muhammad had ordered Malcolm X to withdraw from all public activity, but in April 1964, having advocated that black men arm themselves, he delivered in Cleveland a speech called “The Ballot or the Bullet,” in which he argued that revolution required elections.52 That vantage had brought him to the halls of Congress.

The congressional debates that Malcolm X and Martin Luther King watched revealed fractures within both parties, with Democrats challenged by their southern flank and Republicans by their Right flank. “I’m not anti-Democrat,” Malcolm X said. “I’m not anti-Republican. I’m not anti-anything. I’m just questioning their sincerity.” The point is, he said, the time had come to vote.53 The debates also revealed the worst of American political chicanery. Southern Democrats filibustered for fifty-four days. Strom Thurmond said that the “so-called Civil Rights Proposals, which the President has sent to Capitol Hill for enactment into law, are unconstitutional, unnecessary, unwise and extend beyond the realm of reason.”54 A segregationist from Virginia, Howard Smith, introduced an amendment adding the word “sex” into the bill, a proposal so ridiculous that he was certain it would spell the legislation’s defeat. But after Maine Republican Margaret Chase Smith’s spirited defense of the amendment, it passed—a momentous if ironic achievement in the battle for equality for women.55

Meanwhile, George Wallace, running for the 1964 Democratic nomination, did surprisingly well in early primaries. On the campaign trail, he heard from white voters whose expressions of deep-rooted racial animosity were part of a backlash that would only gain force. At a Wallace rally in Milwaukee, a man named Bronko Gruber said, about the city’s blacks, “They beat up old ladies 83-years-old, rape our womenfolk. They mug people. They won’t work. They are on relief. How long can we tolerate this? Did I go to Guadalcanal and come back to something like this?”56

Wallace’s bid for the nomination was ended, not by Johnson’s popularity, but by the entry into the race of a conservative Republican. Barry Goldwater, a far right conservative Republican from Arizona, voted against the civil rights bill, making clear that he did so on constitutional grounds alone. “If my vote is misconstrued,” he said, “let it be, and let me suffer its consequences.”57 Supporters of the bill eventually broke the filibuster, and on July 2, 1964, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law. Eleven days later, the Republican National Convention met in the Cow Palace, in Daly City, California, and nominated Goldwater as its candidate for president.

In 1960, Goldwater had published a ghostwritten manifesto, The Conscience of a Conservative, that had become a best seller. His positions, at the time, occupied the very margin of American political discourse. He called for the abolition of the graduated income tax and recommended that the federal government abandon most of its functions, closing departments and diminishing staffs at a rate of 10 percent a year. Goldwater also opposed the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board, insisting on states’ rights, a position that aligned him with southern Democrats and also with John Birchers, whose goals included impeaching Earl Warren and withdrawing the United States from the United Nations. Their leader, Robert Welch, had gone so far as to suggest that Eisenhower might be a communist agent; some Birchers believed Sputnik was a hoax. Birchers especially hated Kennedy. Right-wing radio commentator Tom Anderson said in Jackson, Mississippi, “Our menace is not the Big Red Army from without, but the Big Pink Enemy within. Our menace is the KKK—Kennedy, Kennedy, and Kennedy.”58

Conspiracy theorists who believed Eisenhower was a communist looked like an easy target, and some Kennedy advisers, including Arthur Schlesinger Jr., had urged him to tie the Republican Party to the John Birch Society. In 1961, Kennedy began talking about the “right wing” of the GOP. Daniel Bell, in The New American Right, had argued that the “right wing” was fighting nothing so much as modernity itself. Moderate Republicans, too, had energetically attacked Goldwater. New York governor Nelson Rockefeller warned that a “lunatic fringe” might “subvert the Republican party itself.”59 A matchup between Kennedy and Goldwater would have been interesting. Kennedy, who’d had much success debating Nixon in 1960, had apparently agreed to debate Goldwater if he won the Republican nomination in 1964. Goldwater later said that he and Kennedy had planned to cross the country together, debating at every whistle-stop, “without Madison Avenue, without any makeup or phoniness, just the two of us traveling around on the same airplane.”60

But Johnson had no reason to agree to debate Goldwater, whose chances of winning the nomination seemed remote. Rockefeller, vying with Goldwater for the nomination, painted him as a Nazi. (In fact, Goldwater had Jewish ancestry.) Liberals said much the same. “We see dangerous signs of Hitlerism in the Goldwater campaign,” said Martin Luther King. At the Republican National Convention, Margaret Chase Smith, who sought the nomination herself—the first woman to run for a major-party nomination—refused to release her delegates to Goldwater, in order to prevent him from gaining a unanimous vote.61

Richard Nixon did not share Smith’s principles. He’d run unsuccessfully for governor of California in 1962 and, having lost two elections in two years, he was in no position to seek the presidential nomination himself. Nevertheless, he set up a clandestine campaign, headquartered in a boiler room in Portland, Oregon. He considered his options. He toyed with running. He toyed with joining the moderate GOP’s stop Goldwater campaign. And he toyed with supporting Michigan governor George Romney. When he finally concluded that he had no chance of beating Goldwater, he threw his support behind him. Accepting the party’s nomination, Goldwater defended himself against the charge of extremism in language that lost him what little support he might have hoped to enjoy from party moderates. “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” Goldwater said. And “moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Rockefeller and Romney refused to campaign for Goldwater. Nixon, with his eye on 1968, exerted himself tirelessly: he gave 156 speeches on behalf of the party’s nominee.62

Johnson was tickled. “In Your Heart, You Know He’s Right” was Goldwater’s slogan, to which Johnson’s campaign answered, “In Your Guts, You Know He’s Nuts” or, alluding to Goldwater’s enthusiasm for deploying nuclear weapons, “In Your Heart, You Know He Might.” Goldwater had campaigned for a constitutional amendment to guarantee Bible reading and prayer in public schools, but Johnson, who had broad support among evangelical Christians, made sure Goldwater had little success with that constituency. Days before the election, Billy Graham’s followers urged him to throw his support behind Goldwater, sending him more than a million telegrams and tens of thousands of letters. Johnson pounced. “Billy, you stay out of politics,” he told Graham in a phone call, and then invited him to stay the weekend at the White House—far from his mail.63

In November, Goldwater lost to Johnson by more than sixteen million votes, winning only his home state of Arizona and five states in the Deep South. So catastrophic was the loss that GOP leaders attempted to purge conservatives from leadership positions with the party. That meant purging conservative women.

Goldwater’s nomination had been crucially supported by Phyllis Schlafly, a former Kitchen Kabineter who was president of the National Federation of Republican Women. Born in Missouri in 1924, Schlafly would become one of the most influential women in the history of American politics. During the Second World War, she’d worked as a gunner, test-firing rifles in a munitions plant, to put herself through college, after which she’d earned a graduate degree in political science from Radcliffe. A devout Catholic, she had been an ardent supporter of McCarthy; her husband was president of the World Anti-Communist League. In 1952, she’d run for Congress under the slogan “A Woman’s Place Is in the House.”64

In 1963, Schlafly had nominated Goldwater as the speaker at a celebration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the federation of Republican women’s clubs. During that celebration, she’d also taken a straw poll: out of 293 federation delegates, 262 chose Goldwater as the party’s nominee. Conservative women had flocked to the Goldwater campaign’s “Crusade for Law and Morality” and to Mothers for Moral America, a fake grassroots organization that recruited Nancy Reagan to its board. But while conservative women had supported Goldwater, the mainstream of the Republican Party had not. The 1964 presidential election was the first in which as many women voted as men. They also voted differently than men. Overall, across parties, women were even more likely to vote against Goldwater than were men. Goldwater Republican women, it seemed, were out of touch not only with the party but with the country.

After Goldwater’s ignominious defeat, Elly Peterson, a Michigan party chairman and Romney supporter, set herself the task of keeping Schlafly from the presidency of the National Federation of Republican Women at its next election. This proved difficult, Peterson said, because “the nut fringe is beautifully organized.” Schlafly was narrowly defeated, but she contested the results, and police had to remove women from the convention floor when they began attacking one another. The “dame game,” Time said, had become altogether unladylike.65

Schlafly was not so easily defeated. She would never have called herself a feminist, but she believed women should be helping to lead the GOP. “Many men in the Party frankly want to keep the women doing the menial work, while the selection of candidates and the policy decisions are taken care of by the men in the smoke-filled rooms,” she complained. The book she wrote about her ouster includes an illustration of a woman standing at a door labeled Republican Party Headquarters, by a sign that reads “Conservatives and Women Please Use Servants’ Entrance.” Three months after she was kept from the presidency of the women’s arm of the GOP, she began writing a monthly newsletter, waging her own crusade for law and morality.66 It would take her years, but, in the end, she would retake the Republican Party.

Lumbering Lyndon Johnson, flushed with victory, decided to use his sixteen-million-vote margin to shoot for the moon. He had a big Democratic majority in the House, what’s known as a fat Congress. He knew his mandate wouldn’t last. “Just by the way people naturally think and because Barry Goldwater has simply scared the hell out of them, I’ve already lost about three of those sixteen,” he told his staff in January 1965. “After a fight with Congress or something else, I’ll lose another couple of million. I could be down to eight million in a couple of months.”67

Johnson headed what political scientists call a unified government, in which the executive and legislative branches are controlled by the same party, as opposed to a divided government, in which one party controls the White House and the other Congress. Unified governments and divided governments have legislative agendas of roughly the same size, but unified governments, unsurprisingly, are more productive than divided governments: they get more of their bills passed. Still, no unified government in American history was as productive as LBJ’s.68

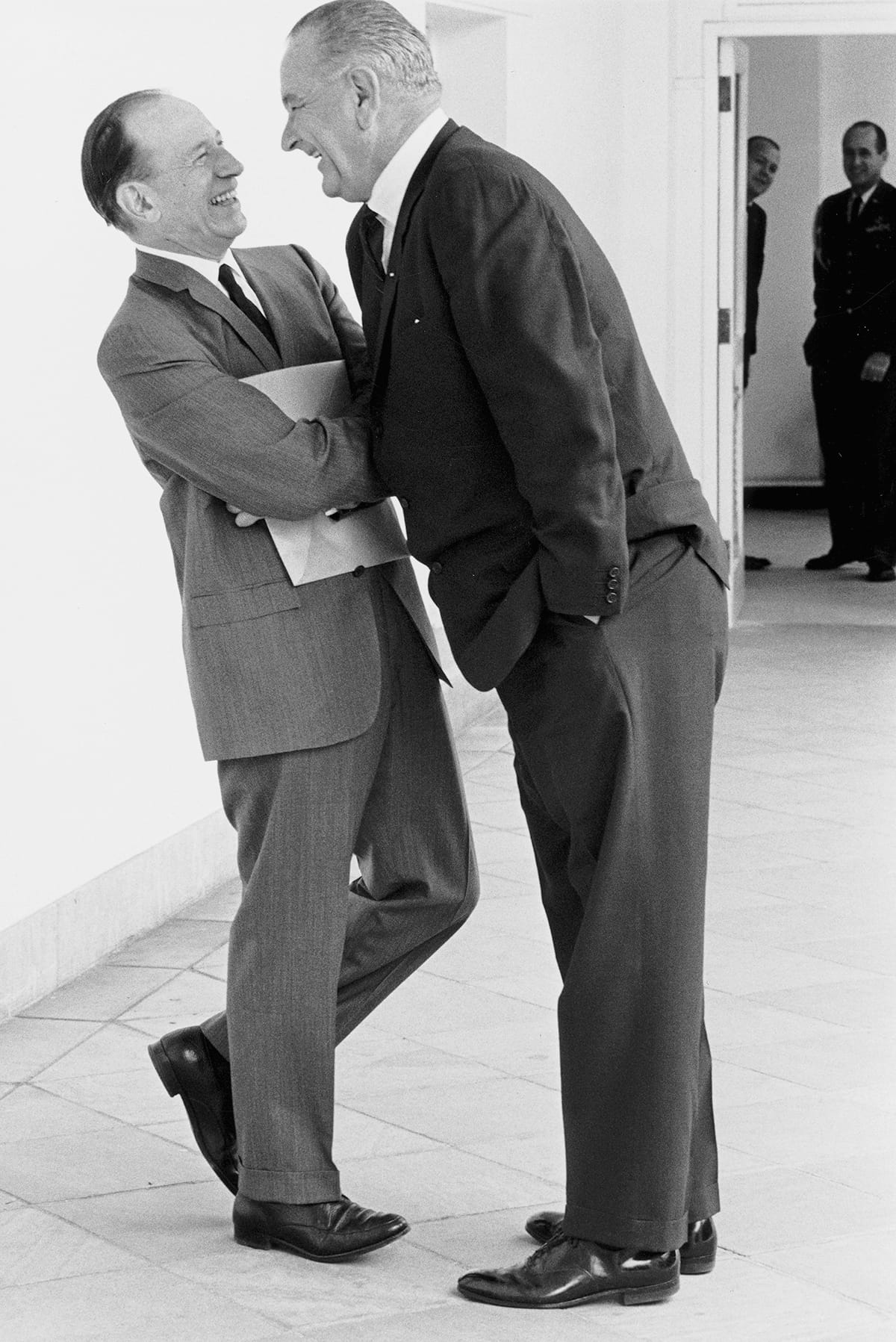

Johnson, who’d begun his career in Washington in 1937, understood the nature of political power better than nearly every other American president. He met with leaders of Congress every week for breakfast. He called senators in the middle of the night. He cajoled and he threatened and he made trades and he made deals. He got Congress to pass an education act, providing millions of dollars to support low-income elementary and high school students. He convinced Congress to amend the Social Security Act to establish Medicare, health insurance for the elderly, and Medicaid, health coverage for the poor—“care for the sick and serenity for the fearful”—and he then flew to Independence, Missouri, so that Truman could witness the signing. “You have made me a very, very happy man,” said a deeply moved Truman.69

The flurry of bills was hardly limited to social reform. Johnson also persuaded Congress to pass a tax bill, a tax cut that had been introduced into Congress before Kennedy’s assassination, the largest tax cut in American history. He hoped it would relieve unemployment. Instead, it undermined his reform programs. It was as if he’d cut off one of his own feet.

“I want to turn the poor from tax eaters to taxpayers,” Johnson said, selling his tax cut to Congress. In this formulation, recipients of social programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), created in 1935, and Medicaid, created in 1965, were the tax eaters. Recipients of other kinds of federal assistance (Medicare, veterans’ benefits, farm subsidies) were the taxpayers. By making this distinction, 1960s liberals crippled liberalism. The architects of the War on Poverty, like the New Dealers before them, never defended a broad-based progressive income tax as a public good, in everyone’s interest; nor could they separate it from issues of race. They also never referred to Social Security, health care, and unemployment insurance as “welfare.” Johnson’s Council of Economic Advisers told him that when explaining how the government might fight poverty, he ought to “avoid completely the use of the term ‘inequality’ or the term ‘redistribution.’” The poor were to be referred to as “targets of opportunity.”70

At first, the tax cut worked: people used the money they once used to pay taxes to buy goods. In 1965, Time put Keynes on the cover and announced, “We Are All Keynesians Now.”71 But, as with everything Johnson did, his economic reforms were demolished by his escalation of the war in Vietnam.

When Kennedy died, Robert Kennedy had pressed Johnson not to abandon Vietnam, which had been Johnson’s inclination. By the spring of 1965, Johnson had come to understand that he couldn’t withdraw without losing, and he didn’t want to lose. “I am not going to be the President who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went,” he said. In March 1965, the United States began to bomb North Vietnam; that spring Johnson committed to ground forces. But because he didn’t want to abandon his domestic agenda, he decided to conceal the escalation. He lied about American involvement, and his administration lied about the war itself. By the end of the year, there were 184,000 troops in Vietnam. College students managed to avoid the draft. Disproportionately, American troops in Vietnam were poor whites and blacks. Johnson deliberately hid the cost of the war. Eventually, paying for the war would require raising taxes. To postpone that inevitability for as long as possible, he cut funding for his social programs. “That bitch of a war,” he later said, “killed the lady I really loved—the Great Society.” Even as the president insisted that “this is not Johnson’s war, this is America’s war,” protesters chanted, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?”72

Johnson, elected in a landslide in 1964, would be so unpopular by 1968 that he’d decide not to run for a second term. And liberalism would be so shattered by Johnson’s compromises, by the rise of the New Left, by race riots, by the antiwar movement, by white backlash, and by the Right’s calls for law and order, that Nixon would gain the prize he’d been eyeing since his days on the high school debate team in Whittier, California: the White House.

IV.

“THERE ARE MORE NEGROES IN JAIL WITH ME THAN THERE ARE ON THE VOTING ROLLS,” read an ad placed in the New York Times by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference while Martin Luther King was in prison in Selma, Alabama. Civil rights workers had been trying to register voters in the Deep South for years, without much success. Still, the spirit of protest had spread.

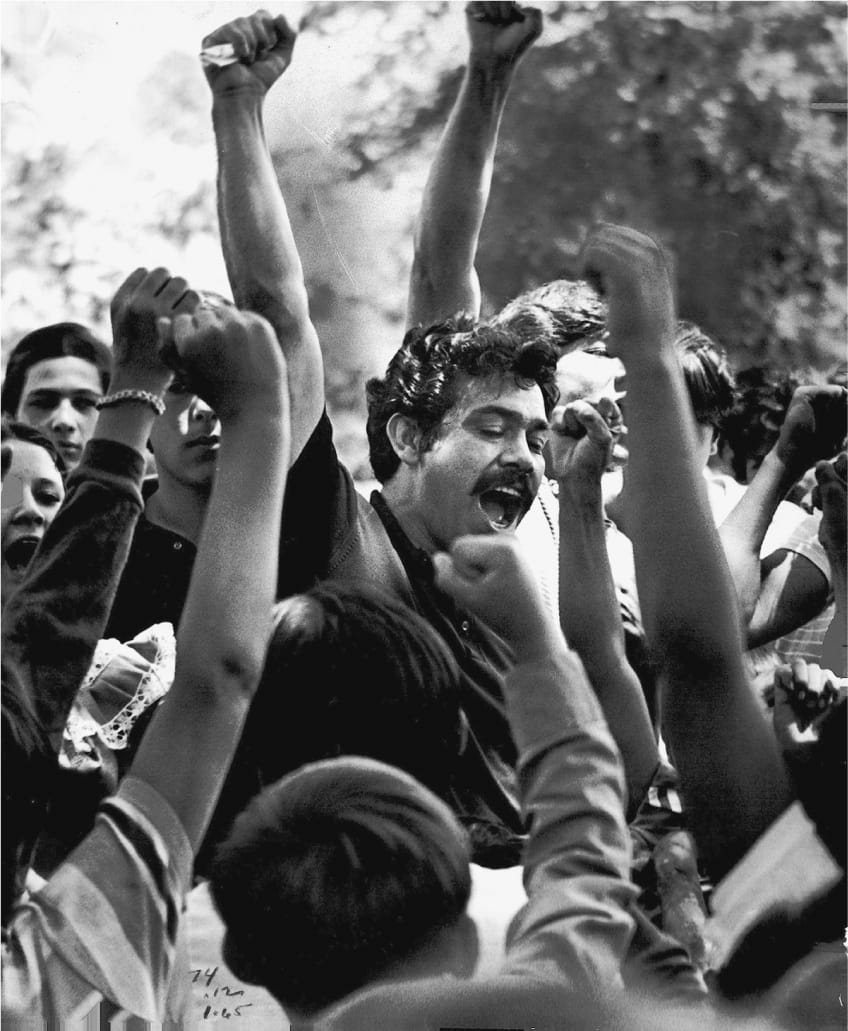

In 1964, Mario Savio, a twenty-one-year-old University of California philosophy major, spent the summer—the Freedom Summer—registering black voters in Mississippi. When he got back to Berkeley that fall, he led a fight against a policy that prohibited political speech on campus by arguing that a public university should be as open for political debate and assembly as a public square. The same right was at stake in both Mississippi and Berkeley, Savio said: “the right to participate as citizens in a democratic society.”73 After police arrested nearly eight hundred protestors during a sit-in, the university acceded to the students’ demands. The principle of allowing political speech on campus was afterward extended from public universities to private ones. Without this principle, students wouldn’t have been able to rally on campus for civil rights or against the war in Vietnam, or for or against anything else, then or since.

But the fight for a democratic society divided the Left. When the civil rights movement turned its attention from desegregation to voting rights, it splintered. The fight for voting rights also hit a wall with the Democratic Party. Contesting the Democratic Party’s all-white delegation to the party’s nominating convention, SNCC set up an alternative party, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Ella Baker ran its Washington office and delivered the keynote speech at its state nominating convention in Jackson. At the Democratic Party’s August 1964 convention in Atlantic City, party leaders refused to seat the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegation. Stokely Carmichael decided to give up on party politics. Carmichael, who’d been a Freedom Rider in 1961, graduated from Howard University in 1964 with a degree in philosophy and was nominated for a Senior Class Humanity Award for his work registering voters in Mississippi; he’d been arrested half a dozen times. “The liberal Democrats are just as racist as Goldwater,” he concluded. Borrowing the word “black” from Malcolm X, Carmichael urged a new militancy. “If we can’t sit at the table,” said one leader of SNCC, “let’s knock the fucking legs off.” King, and the SCLC, still favored working with white liberals; SNCC, increasingly, favored black consciousness and black power. Selma would be their last stand together.74

In January 1965, one hundred years after Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, Johnson delivered his inaugural address in Washington, and King went to Selma, where demonstrators had pledged to march all the way to Montgomery, a fifty-five-mile journey that would take them through a county whose population was more than 70 percent black but where hardly any African Americans had so much as attempted to vote since the rise of Jim Crow. On March 7, 1965, they met five hundred Alabama state troopers stationed on the far side of the Pettus Bridge, ordered by George Wallace to arrest anyone who tried to cross.

Malcolm X, who had by now been denounced by the Nation of Islam, flew to Selma. Though SCLC leaders worried that he’d incite violence, he spoke in support of the protesters. Only weeks later, his house was firebombed in New York, and, on February 21, he was assassinated in Manhattan by three men from the Nation of Islam armed with pistols and shotguns. He was shot ten times, once in the ankle, twice in the leg, and seven times in the chest.75 “I disagreed with him,” James Baldwin said, deeply shaken. “But when he talked to the people in the streets,” he went on, “if one ignored his conclusions, he was the only person who was describing, making vivid, making a catalog, of the actual situation of the American Negro.”76

Johnson, pressured by the televised spectacle of Alabama state troopers cracking the skulls of civil rights marchers in Selma as they repeatedly tried to cross the bridge, addressed Congress on March 15. “At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom,” he said. “So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.” Calling on Congress to pass a Voting Rights Act, he closed, with his trademark Texas twang: “And we shall overcome.” King, watching in Alabama, fell to weeping.77

The week before Johnson sent Congress the Voting Rights Act, he’d sent Congress the Law Enforcement Assistance Act, saying he wanted 1965 to be remembered as “the year when this country began a thorough, intelligent, and effective war against crime.” The creation of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, which funded eighty thousand crime control projects, vastly expanded the police powers of the federal government. “For some time, it has been my feeling that the task of law enforcement agencies is really not much different from military forces; namely, to deter crime before it occurs, just as our military objective is deterrence of aggression,” the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee had said during hearings over the bill. After Johnson signed the act into law, his administration opened a “war on crime,” a war in which the police were empowered to act like a military force, using helicopters to patrol city neighborhoods and computer simulations to anticipate crime. Money that had gone to cities for antipoverty measures was used to fight crime. After-school programs and teen centers, instituted as elements of the war on poverty under Johnson, would come, under Nixon, beginning in 1969, to be run by police, elements of the war on crime. More Americans would be sent to prison in the twenty years after LBJ launched his war on crime than went to prison in the entire century before. Blacks and Latinos, 25 percent of the U.S. population, would make up 59 percent of the prison population, in a nation whose incarceration rate would rise to five times that of any other industrial nation. Dismantling the parts of Johnson’s program that were aimed to provide services to children and teenagers, Nixon would leave intact only the parts of the program that were aimed to punish them. Running the Great Society became the work of police. Block grants for urban renewal were used, instead, to build prisons. James Baldwin said urban renewal ought to be called “Negro removal.”78

On August 6, 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. But the quiet that Johnson had anticipated did not come. The next day, the House Committee on Education and Labor held hearings in Los Angeles’s Will Rogers Park Auditorium to find out why the city had failed to implement federal antipoverty programs. A thousand people came; the hearings turned into a rally. Four days later, riots broke out in South Central Los Angeles, in Watts, the first in a series of riots that would shock the nation over four long, hot summers.

King flew to Los Angeles and preached nonviolence; no one really listened. The population density in the city of Los Angeles, outside of Watts, was 5,900 per square mile; in Watts, it was 16,400. The uprising lasted for six days and nights and involved more than 35,000 people. Thirty-four people were killed and nearly a thousand injured as the streets burned. Army tanks and helicopters turned an American city into a war zone. L.A. police chief William Parker said that fighting the people of Watts was “very much like fighting the Viet Cong.”79 Johnson asked, “Is the world topsy-turvy?”80

Watts, a neighborhood twice the size of Manhattan, had not a single hospital. An affluent society? Watts was an indigent society. From the outside, it looked as if rights had been answered with riots, as if the entire project of liberalism were collapsing in on itself.