Air force parajumper Tim Wilkinson climbed back into the wrecked helicopter looking for a way to get more leverage to free pilot Cliff Wolcott’s body. Maybe there was some way he hadn’t seen at first to pull the seat back and get more room and a better angle. But it was hopeless.

He climbed back out. Kneeling on top of the wreck in the shattering din of automatic weapons fire, he peered down through the open right side doors into the rear of the aircraft. He thought they had accounted for everyone on board. He knew some of the men had been rescued earlier by the Little Bird that landed right after the crash. So Wilkinson was looking for sensitive equipment or weapons that would have to be removed or destroyed. PJs are trained to quickly erase the memory banks of any electronic equipment with sensitive data. All of the avionics equipment and every piece of gear that hadn’t been strapped down had come to rest at the left side of the aircraft, which was now the bottom.

In the heap he noticed a scrap of desert fatigues.

“I think there’s somebody else in there,” he told Sergeant Bob Mabry, a Delta medic on the CSAR crew.

Wilkinson leaned in further and saw an arm and a flight glove. He called down into the wreck and a finger of the flight glove moved. Wilkinson climbed back into the wreckage and began pulling the debris and equipment off of the man buried there. It was the second crew chief, the left side gunner, Ray Dowdy. Part of his seat had gotten slammed and broken off the hinges but it was still basically intact and in place. When Wilkinson freed Dowdy’s arm from under the pile, the crew chief began shoving things away. He still hadn’t spoken and was only half conscious.

Mabry slithered down under the wreck and tried without success to crawl in through the bottom left side doorway. He gave up and climbed in through the upper doors just as Wilkinson freed Dowdy. The three men stood inside the wreck as a storm of bullets suddenly poked through the skin of the craft. Mabry and Wilkinson danced involuntarily at the sharp burst of snapping and crashing noises. Bits of metal, plastic, paper, and fabric flew around them like a sudden snow squall. Then it stopped. Wilkinson remembers noting, first, that he was still alive. Then he checked himself. He’d been hit in the face and arm. It felt like he’d been slapped or punched in the chin. Everyone had been hit. Mabry had been hit in the hand. Dowdy had lost the tips of two fingers.

The crew chief stared blankly at his bloody hand.

Wilkinson put his hand over the bleeding fingertips and said, “Okay, let’s get out of here!”

Mabry tore up the Kevlar floor panels and propped them up over the side of the craft where the bullets had burst through. Instead of braving the fire above, they tunneled out, digging through the dry sand at the rear corner of the left side door. They slid Dowdy out that way.

Then the two rescuers climbed back inside, Wilkinson looking for equipment to destroy, Mabry handing out Kevlar panels to be placed around the tail of the aircraft where they had established a casualty collection point. Fire was coming mostly up and down the alley. They were still expecting the arrival of the ground convoy at any moment.

Wounded Sergeant Fales was too busy shooting to take notice of the Kevlar pads. He had a pressure dressing on his calf and an IV tube in his arm and he was lying out by the broken tail boom looking for targets.

Wilkinson poked his head out the top. “Scott, why don’t you get behind the Kevlar?”

Fales looked startled. He had been so absorbed firing he hadn’t seen the panels go up behind him.

“Good idea,” he said.

Bullet hole after bullet hole poked through the broken tail boom.

Wilkinson was reminded of the Steve Martin movie The Jerk, where Martin’s moronic character, unaware that villains are shooting at him, watches with surprise as bullet holes begin popping open a row of oil cans. He shouted Martin’s line from the movie.

“They hate the cans! Stay away from the cans!”

Both men laughed.

After patching up a few more men, Wilkinson crawled back up into the cockpit from underneath, to see if there was some way of pulling Wolcott’s body down and out. There wasn’t.

A grenade came from somewhere. It was one of those Russian types that looked like a soup can on the end of a stick. It bounced off the car and then off Specialist Jason Coleman’s helmet and radio and then it hit the ground.

Nelson, who was still deaf from Twombly’s timely machine-gun blast, pulled his M-60 from the roof of the car and dove, as did the men on both sides of the intersection. They stayed down for almost a full minute, cushioning themselves from the blast. Nothing happened.

“I guess it’s a dud,” said Lieutenant DiTomasso.

Thirty seconds later another grenade rolled out into the open space between the car and the tree across the street. Nelson again grabbed the gun off the car and rolled with it away from the grenade. Everyone braced themselves once more, and this, too, failed to explode. Nelson thought they had spent all their luck. He and Barton were crawling back toward the car when a third grenade dropped between them. Nelson turned his helmet toward it and pushed his gun in front of him, shielding himself from the blast that this time was sure to come. He opened his mouth, closed his eyes, and breathed out hard in anticipation. The grenade sizzled. He stayed like that for a full twenty seconds before he looked up at Barton.

“Dud,” Barton said.

Yurek grabbed it and threw it into the street.

Someone had bought themselves a batch of bad grenades. Wilkinson later found three or four more unexploded ones inside the body of the helicopter.

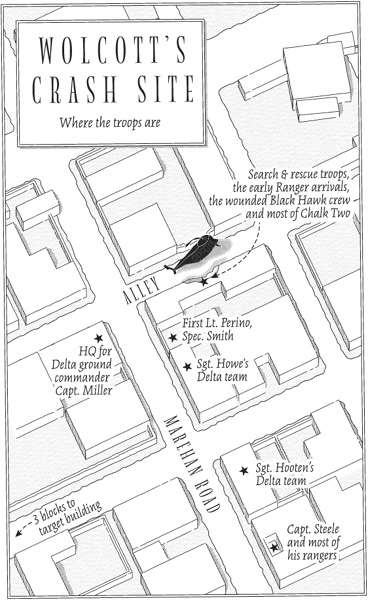

The American forces around Wolcott’s downed Black Hawk were now scattered along an L-shaped perimeter stretching south. One group of about thirty men was massed around the wreck in the alleyway, at the northern base of the “L.” When they learned that the ground convoy had gotten lost and delayed, they began moving the wounded through the hole made by the falling helicopter into the house of Abdiaziz Ali Aden (he was still hidden in a back room). Immediately west of the alley (at the bend of the “L”) was Marehan Road, where Nelson, Yurek, Barton, and Twombly were dug in across the street at the northwest corner. On the east side of that intersection, nearest the chopper, were DiTomasso, Coleman, Belman, and Delta Captain Bill Coultrop and his radio operator. The rest of the ground force was stretched out south on Marehan Road, along the stem of the “L,” which sloped uphill. Steele and a dozen or so Rangers, along with three Delta teams, about thirty men in all, were together in a courtyard on the east side of Marehan Road midway up the next block south, separated from the bulk of the force by half a block, a wide alley, and a long block. Sergeant Howe’s Delta team, with a group of Rangers that included Specialist Stebbins, followed by the Delta command group led by Captain Miller, had crossed the wide alley and was moving down the west wall toward Nelson’s position. Lieutenant Perino had also crossed the alley and was moving downhill along the east wall with Corporal Smith, Sergeant Chuck Elliot, and several other men.

As Howe approached Nelson’s position, it looked to him as though the Rangers were just hiding. Two of his men ran across the alley to tell the Rangers to start shooting. Nelson and the others were still recovering from the shock of the unexploded grenades. Rounds were taking chips off the walls all around them, but it was hard to see where the shots were coming from. Howe’s team members helped arrange Nelson and the others to set up effective fields of fire, and placed Stebbins and machine-gunner Private Brian Heard at the southern corner of the same intersection, orienting them to fire west.

Captain Miller caught up with Howe, trailing his radioman and some other members of his element, along with Staff Sergeant Jeff Bray, an air force combat controller. With all the shooting at that intersection, Howe decided it was time to get off the street. There was a metal gate at the entrance to a courtyard between two buildings on his side of the block. He pushed against the gate, which had two doors that opened inward. Howe considered putting a charge on the door, but given the number of soldiers nearby and the lack of cover, the explosion would probably hurt people. So the burly sergeant and Bray began hurling themselves against the gate. Bray’s side gave way.

“Follow me in case I get shot,” Howe said.

He plunged into the courtyard and rapidly moved through the house on either side, running from room to room. Howe was looking for people, focusing his eyes at midtorso first, checking hands. The hands told you the whole story. The only hands he found were empty. They belonged to a man and woman and some children, a family of about seven, clearly terrified. He stood in the doorway with his weapon in his right hand pointing at them, trying to coax them out of the room with his left hand. It took a while, but they came out slowly, clinging to each other. The family was flex-cuffed and herded into a small side room.

Howe then more carefully inspected the space. Each of the blocks in this neighborhood of Mogadishu consisted of mostly one-story stone houses grouped irregularly around open spaces, or courtyards. This block consisted of a short courtyard, about two car-lengths wide, where he now stood. There was a two-story house on the south side and a one-story house on the north. Howe figured this space was about the safest spot around. The taller building would shelter them from both bullets and lobbed RPGs. At the west end was some kind of storage shack. Howe began exploring systematically, making a more thorough sweep, moving from room to room, looking for windows that would give them a good vantage for shooting west down the alley. He found several but none that offered a particularly good angle. The alley to the north (the same one that the helicopter had crashed into one block west) was too narrow. He could only see about fifteen yards down in either direction, and all he saw was wall. When he returned to the courtyard, Captain Miller and the others had begun herding casualties into the space. It would serve as their command post and casualty collection point for the rest of the night.

As he reentered the courtyard, one of the master sergeants with Miller told Howe to go back out to the street and help his team. Howe resented the order. He felt he was, at this point, the de facto leader on the ground, the one doing all the real thinking and moving and fighting. They had reached a temporary safe point, a time for commanders to catch their breath and think. They were in a bad spot, but not critical. The next step would be to look for ways to strongpoint their position, expand their perimeter, identify other buildings to take down to give them better lines of fire. The troop sergeant’s command was the order of a man who didn’t know what to do next.

Howe was built like a pro wrestler, but he was a thinker. This sometimes troubled his relationship with authority—especially the army’s maddeningly arbitrary manner of placing unseasoned, less-qualified men in charge. Howe was just a sergeant first class with supposedly narrower concerns, but he saw the big picture very clearly, better than most. After being selected for Delta he had met and married the daughter of Colonel Charlie A. Beckwith, the founder and original commander of Delta. They had met in a lounge by Fort Bragg and when he told her that he was a civilian, Connie Beckwith, a former army officer then herself, nodded knowingly.

“Look,” she said. “I know who you work for so let’s stop pretending. My dad started that unit.”

She had to pull out her driver’s license to prove who she was.

Not that Howe had any ambition for formal army leadership. His preferred relationship with officers was for them to heed his advice and leave him alone. He was frequently aghast at the failings of those in charge.

Take this setup in Mogadishu, for instance. It was asinine. At the base, the huge hangar front doors wouldn’t close, so the Sammies had a clear view inside at all hours of the day or night. The city sloped gradually up from the waterfront, so any Somali with patience and binoculars could keep an eye on their state of readiness. Every time they scrambled to gear up and go, word was out in the city before they were even on the helicopters. If that weren’t bad enough, you had the Italians, some of them openly sympathetic to their former colonial subjects, who appeared to be flashing signals with their headlights out into the city whenever the helicopters took off. Nobody had the balls to do anything about it.

Then there were the mortars. General Garrison seemed to regard mortars as little more than an annoyance. He had walked around casually during the early mortar attacks, his cigar clenched in his teeth, amused by the way everyone dove for cover. “Piddly-assed mortars,” he’d said. Which was all well and good, except, as Howe saw it, if the Sammies ever got their act together and managed to drop a few on the hangar, there’d be hell to pay. He wondered if the tin roof was thick enough to detonate the round—which would merely send shrapnel and shards of the metal roof slashing down through the ranks—or whether the round would just poke on through and detonate on the concrete floor in the middle of everybody. It was a question that lingered in his mind most nights as he went to sleep. Then there were the flimsy perimeter defenses. At mealtimes, all the men would be lined up outside the mess hall, which was separated from a busy outside road by nothing more than a thin metal wall. A car bomb along that wall at the right time of day could kill dozens of soldiers.

Howe did not hide his disgust over these things. Now, being ordered to do something pointless in the middle of the biggest fight of his life, he was furious. He began gathering up ammo, grenades, and LAWS off the wounded Rangers in the courtyard. It seemed to Howe that most of the men failed to grasp how desperate their situation had become. It was a form of denial. They could not stop thinking of themselves as the superior force, in command of the situation, yet the tables had clearly turned. They were surrounded and terribly outnumbered. The very idea of adhering to rules of engagement at this point was preposterous.

“You’re throwing grenades?” the troop sergeant major asked him, surprised when he saw Howe stuffing all of them he could find into his vest pockets.

“We’re not getting paid to bring them back,” Howe told him.

This was war. The game now was kill or be killed. He stomped angrily out to the street and began looking for Somalis to shoot.

He found one of the Rangers, Nelson, firing a handgun at the window of the building Howe had just painstakingly cleared and occupied. Nelson had seen someone moving in the window, and they had been taking fire from just about every direction, so he was pumping a few rounds that way.

“What are you doing?” Howe shouted across the alley.

Nelson couldn’t hear Howe. He shouted back, “I saw someone in there.”

“No shit! There are friendlies in there!”

Nelson didn’t find out until later what Howe had been waving his arms about. When he did he was mortified. No one had told him that Delta had moved into that space, but, then again, it was a cardinal sin to shoot before identifying a target.

Already furious, Howe began venting at the Rangers. He felt they were not fighting hard enough. When he saw Nelson, Yurek, and the others trying to selectively target armed Somalis in a crowd at the other end of a building on their side of the street, Howe threw a grenade over its roof. It was an amazing toss, but the grenade failed to explode. So Howe threw another, which exploded right where the crowd was gathered. He then watched the Rangers try to hit a gunman who kept darting out from behind a shed about one block north, shooting, and then retreating back behind it. The Delta sergeant flung one of his golf ball–sized minigrenades over the Rangers’ position. It exploded behind the shed, and the gunman did not reappear. Howe then picked up a LAW and hurled it across the road. It landed on the arm of Specialist Lance Twombly, who was lying on his belly four or five feet from the corner wall. The LAW bruised his forearm. Twombly jumped to his knees, angry, and turned to hear Howe bellowing, “Shoot the motherfucker!”

Down on one knee, Howe swore bitterly as he fired. Everything about this situation was pissing him off, the goddamn Somalis, his leaders, the idiot Rangers ... even his ammunition. He drew a bead on three Somalis who were running across the street two blocks to the north, taking a progressive lead on them the way he had learned through countless hours of training, squaring them in his sights and then aiming several feet in front of them. He would squeeze two or three rounds, rapidly increasing his lead with each shot. He was an expert marksman, and thought he had hit them, but he couldn’t tell for sure because they kept running until they crossed the street and were out of view. It bugged him. His weapon was the most sophisticated infantry rifle in the world, a customized CAR-15, and he was shooting the army’s new 5.56 mm green-tip round. The green tip had a tungsten carbide penetrator at the tip, and would punch holes in metal, but that very penetrating power meant his rounds were passing right through his targets. When the Sammies were close enough he could see when he hit them. Their shirts would lift up at the point of impact, as if someone had pinched and plucked up the fabric. But with the green-tip round it was like sticking somebody with an ice pick. The bullet made a small, clean hole, and unless it happened to hit the heart or spine, it wasn’t enough to stop a man in his tracks. Howe felt like he had to hit a guy five or six times just to get his attention. They used to kid Randy Shughart because he shunned the modern rifle and ammunition and carried a Vietnam era M-14, which shot a 7.62 mm round without the penetrating qualities of the new green tip. It occurred to Howe as he saw those Sammies keep on running that Randy was the smartest soldier in the unit. His rifle may have been heavier and comparatively awkward and delivered a mean recoil, but it damn sure knocked a man down with one bullet, and in combat, one shot was often all you got. You shoot a guy, you want to see him go down; you don’t want to be guessing for the next five hours whether you hit him, or whether he’s still waiting for you in the weeds.

Howe was in a good spot. There was nothing in front or behind him that would stop a bullet, but there was a tree about twenty feet south against the west wall of the street that blocked any view of him from that direction. The bigger tree across the alley where Nelson, Twombly, and the others were positioned blocked any view of him from the north. So the broad-beamed Delta sergeant could kneel about five feet off the wall and pick off targets to the north with impunity. It was like that in battle. Some spots were safer than others. Up the hill, Hooten had watched Howe and his team move across the intersection while he was lying with his face pressed in the dirt, with rounds popping all around him. How can they be doing that? he’d thought. By an accident of visual angles, one person could stand and fight without difficulty, while just a few feet away fire could be so withering that there was nothing to do but dive for cover and stay hidden. Howe recognized he’d found such a safety zone. He shot methodically, saving his ammunition.

When he saw Perino, Smith, and Elliot creeping down to a similar position on the other side of the street, he figured they were trying to do what he was doing. Except, on that side of the street there were no trees to provide concealment.

He shouted across at them impatiently, but in the din he wasn’t heard.

Perino and his men had moved down to a small tin shed, a porch really, that protruded from the irregular gray stone wall. They were only about ten yards from the alley where Super Six One lay. A West Point graduate, class of 1990, Perino at twenty-four wasn’t much older than the Rangers he commanded. His group had gotten out ahead of Captain Steele and most of the Ranger force. They had pushed across the last intersection to the crash site after Goodale had been hit. They had cleared the first courtyard they passed on that block, and Perino had then led several of the men back out in the street to press on down Marehan Road. He knew they were close to linking up with Lieutenant DiTomasso and the CSAR team, which had been their destination when they started this move. The shed was just a few steps downhill from the courtyard doorway.

Sergeant Elliot was already on the other side of the shed. Corporal Smith was crouched behind it and Perino was just a few feet behind Smith. They were taking so much fire it was confusing. Rounds seemed to be coming from everywhere. Stone chips sprayed from the wall over Perino’s head and rattled down on his helmet. He saw a Somali with a gun on the opposite side of the street, about twenty yards north of Nelson’s position, blocked from those guys’ view by the tree they were hiding behind. Perino saw the muzzle flash and could tell this was where some of the incoming rounds originated. It would be hard to hit the guy with a rifle shot, but Smith had a grenade launcher on his M-16 and might be able to drop a 203 round near enough to hurt the guy. He moved up to tap Smith on the shoulder—there was too much noise to communicate other than face-to-face—when bullets began popping loudly through the shed. The lieutenant was on one knee and a round spat up dirt between his legs.

Across the street, Nelson saw Smith get hit. The burly corporal had moved down the street fast and had taken a knee to begin shooting. Most of the men at that corner heard the round hit him, a hard, ugly slap. Smith seemed just startled at first. He rolled to his side and, like he was commenting about someone else, remarked with surprise, “I’m hit!”

From where Nelson was, it didn’t look like Smith was hurt that badly. Perino helped move him against the wall. Now Smith was screaming, “I’m hit! I’m hit!”

The lieutenant could tell by the sound of Smith’s voice that he was in pain. When Goodale had been hit he seemed to feel almost nothing, but the wound to Smith was different. He was writhing. He was in a very bad way. Perino pressed a field dressing into the wound but blood spurted out forcefully around it.

“I’ve got a bleeder here!” Perino shouted across the street.

Delta medic Sergeant Kurt Schmid dashed toward them across Marehan Road. Together, they dragged Smith back into the courtyard.

Schmid tore off Smith’s pants leg. When he removed the battle dressing, bright red blood projected out of the wound in a long pulsing spurt. This was bad.

The young soldier told Perino, “Man, this really hurts.”

The lieutenant went back out to the street and crept back up to Elliot.

“Where’s Smith?” Elliot asked.

“He’s down.”

“Shit,” said Elliot.

They saw Sergeant Ken Boorn get hit in the foot. Then Private Rodriguez rolled away from his machine gun, bleeding, screaming, and holding his crotch. He felt no pain, but when he had placed his hand on the wound his genitals felt like mush and blood spurted thickly between his fingers. He screamed in alarm. Eight of the eleven Rangers in Perino’s Chalk One had now been hit.

At the north end of the same block there was a huge explosion and in it Stebbins went down. Nelson saw it from up close. An RPG had streaked into the wall of the house across the alley from him, over near where Stebbins and Heard were positioned. The grenade went off with a brilliant red flash and tore out a chunk of the wall about four feet long. The concussion in the narrow alley was huge. It hurt his ears. There was a big cloud of dust. He saw—and Perino and Elliot saw from across the street—both Stebbins and Heard flat on their backs. They’re fucked up, Nelson thought. But Stebbins stirred and then slowly stood up, covered from head to foot in white dust, coughing, rubbing his eyes.

“Get down, Stebbins!” shouted Heard. So he was okay, too.

Bullets were hitting around Perino and Elliot with increasing frequency. Rounds would come in long bursts, snapping between them, over their heads, nicking the tin shed with a high-pitched ring and popping right through the metal. Rounds were kicking up dirt all over their side of the street. It was a bad position, just as Howe had foreseen.

“Uh, sir, I think that it would be a pretty good idea if we go into that courtyard,” said Elliot.

“Do you really think so?” Perino asked.

Elliot grabbed his arm and they both dove for the courtyard where Schmid was working frantically to save Smith.

Corporal Smith was alert and terrified and in sharp pain. The medic had first tried applying direct pressure on the wound, which had proved excruciatingly painful and obviously ineffective. Bright red blood continued to gush from the hole in Smith’s leg. The medic tried jamming Curlex into the hole. Then he checked Smith over.

“Are you hurt anywhere else?” he asked.

“I don’t know.”

Schmid checked for an exit wound, and found none.

The medic was thirty-one. He’d grown up an army brat, vowing never to join the military, and ended up enlisting a year after graduating from high school. He’d gone into Special Forces and elected to become a medic because he figured it would give him good employment opportunity when he left the army. He was good at it, and his training kept progressing. By now he’d been schooled as thoroughly as any physician’s assistant, and better than some. As part of his training he’d worked in the emergency room of a hospital in San Diego, and had even done some minor surgery under a physician’s guidance. He certainly had enough training to know that Jamie Smith was in trouble if he couldn’t stop the bleeding.

He could deduce the path the bullet had taken. It had entered Smith’s thigh and traveled up into his pelvis. A gunshot wound to the pelvis is one of the worst. The aorta splits low in the abdomen, forming the left and right iliac arteries. As the iliac artery emerges from the pelvis it branches into the exterior and deep femoral arteries, the primary avenues for blood to the lower half of the body. The bullet had clearly pierced one of the femoral vessels. Schmid applied direct pressure to Smith’s abdomen, right above the pelvis where the artery splits. He explained what he was doing. He’d already run two IVs into Smith’s arm, using 14-gauge, large bore needles, and was literally squeezing the plastic bag to push replacement fluid into him. Smith’s blood formed an oily pool that shone dully on the dirt floor of the courtyard.

The medic took comfort in the assumption that help would arrive shortly. Another treatment tactic, a very risky one, would be to begin directly transfusing Smith. Blood transfusions were rarely done on the battlefield. It was a tricky business. The medics carried IV fluids with them but not blood. If he wanted to transfuse Smith, he’d have to find someone with the same blood type and attempt a direct transfusion. This was likely to create more problems. He could begin reacting badly to the transfusion. Schmid decided not to attempt it. The rescue convoy was supposed to be arriving shortly. What this Ranger needed was a doctor, pronto.

Perino radioed Captain Steele.

“We can’t go any further, sir. We have more wounded than I can carry.”

“You’ve got to push on,” Steele told him.

“We CANNOT go further,” Perino said. “Request permission to occupy a building.”

Steele told Perino to keep trying. Actually, inside the courtyard they were only about fifty feet from Lieutenant DiTomasso and the CSAR force, but Perino had no way of knowing that. He tried to reach DiTomasso on his radio.

“Tom, where are you?”

DiTomasso tried to explain their position, pointing out landmarks.

“I can’t see,” said Perino. “I’m in a courtyard.”

DiTomasso popped a red smoke grenade, and Perino saw the red plume drifting up in the darkening sky. He guessed from the drift of the plume that they were about fifty yards apart, which in this killing zone was a great distance. On the radio, Steele kept pushing him to link up with DiTomasso.

“They need your help,” he said.

“Look, sir, I’ve got three guys left, counting myself. How can I help him?”

Finally, Steele relented.

“Roger, strongpoint the building and defend it.”

Schmid was still working frantically on Smith’s wound. He’d asked Perino to help him by applying pressure just over the wound so he could use his hands. Perino pushed two fingers directly into the wound up to his knuckles. Smith screamed and blood shot out at the lieutenant, who swallowed hard and applied more pressure. He felt dizzy. The spurts of blood continued.

“Oh, shit! Oh, shit! I’m gonna die! I’m gonna die!” Smith shouted. He knew he had an arterial bleed.

The medic talked to him, tried to calm him down. The only way to stop the bleeding was to find the severed femoral artery and clamp it. Otherwise it was like trying to stanch a fire hose by pushing down on it through a mattress. He told Smith to lean back.

“This is going to be very painful,” Schmid told the Ranger apologetically. “I’m going to have to cause you more pain, but I have to do this to help you.”

“Give me some morphine for the pain!” Smith demanded. He was still very alert and engaged.

“I can’t,” Schmid told him. In this state, morphine could kill him. After losing so much blood, his pressure was precariously low. Morphine would further lower his heart rate and slow his respiration, exactly what he did not need.

The young Ranger bellowed as the medic reached with both hands and tore open the entrance wound. Schmid tried to shut out the fact that there were live nerve endings beneath his fingers. It was hard. He had formed an emotional bond with Smith. They were in this together. But to save the young Ranger, he had to treat him like an inanimate object, a machine that was broken and needed fixing. He continued to root for the artery. If he failed to find it, Smith would probably die. He picked through the open upper thigh, reaching up to his pelvis, parting layers of skin, fat, muscle, and vessel, probing through pools of bright red blood. He couldn’t find it. Once severed, the upper end of the artery had evidently retracted up into Smith’s abdomen. The medic stopped. Smith was lapsing into shock. The only recourse now would be to cut into the abdomen and hunt for the severed artery and clamp it. But that would mean still more pain and blood loss. Every time he reached into the wound Smith lost more blood. Schmid and Perino were covered with it. Blood was everywhere. It was hard to believe Smith had any more to lose.

“It hurts really bad,” he kept saying. “It really hurts.”

In time his words and movements came slowly, labored. He was in shock.

Schmid was beside himself. He had squeezed six liters of fluid into the young Ranger and was running out of bags. He had tried everything and was feeling desperate and frustrated and angry. He had to leave the room. He got one of the other men to continue applying pressure on the wound and walked out to confer with Perino. Both men were covered with Smith’s blood.

“If I don’t get him out of here right now, he’s gonna die,” Schmid pleaded.

The lieutenant radioed Steele again.

“Sir, we need a medevac. A Little Bird or something. For Corporal Smith. We need to extract him now.”

Steele relayed this on the command net. It was tough to get through. It was nearly five o’clock and growing dark. All of the vehicles had turned back to the air base. Steele learned that there would be no relief for some time. Putting another bird down in their neighborhood was out of the question.

The captain radioed Perino back and told him, for the time being, that Smith would just have to hang on.

Stebbins shook with fear. Having his friends around him kept him going, but that was about all that did. You could be prepared for the sights and sounds and smells of war, but the horror of it, the blood and gore and heartrending screams of pain, the sense of death perched right on your shoulder, breathing in your ear, there was no preparation for that. Things felt balanced on an edge, threatening at any moment to spin out of control. Was this what he had wanted so badly? An old platoon sergeant had told him once, “When war starts, a soldier wants like hell to be there, but once he’s there, he wants like hell to come home.”

Beside Stebbins, a burst of rounds hit Heard’s M-60, disabling it permanently. Heard drew his 9 mm handgun and fired it. Squinting down the alley west into the setting sun, Stebbins could see the white shirts of Somali fighters. There were dozens of them. Groups would come running out and fire volleys up the alley, and then duck back behind cover. Over his right shoulder, across Marehan Road and down the alley, he could hear the rescue guys hammering at the wreck, still trying to free Wolcott’s body. The sky overhead was getting darker, and there was still no sign of the ground convoy. They had actually seen the vehicles drive past just a few blocks west about an hour earlier. Where were they?

Everyone dreaded the approaching darkness. One distinct advantage U.S. soldiers had wherever they fought was their night-vision technology, their NODs (Night Observation Devices), but they had left them back at the hangar. The NODs were worn draped around the neck when not in use, and weighed probably less than a pound, but they were clumsy, annoying, and very fragile. It was an easy choice to leave them behind on a daylight mission. Now the force faced the night thirsty, tired, bleeding, running low on ammo, and without one of their biggest technological advantages. Stebbins, the company clerk, gazed out at the giant orange ball easing behind buildings to the west and had visions of a pot of fresh-brewed coffee out there somewhere waiting for him.

The Little Birds had the lay of the land well enough now to be making regular gun runs, and were doing a lot to keep at bay the Somalis crowded around the neighborhood. The tiny helicopters came swooping in at almost ground level, flying between buildings with their miniguns ablaze. It was an amazing sight. The rockets made a ripping sound and then shook the ground with their blasts. Twombly was admiring one such run when Sergeant Barton told him the pilots were still calling for more markers on the road to better outline the American positions.

“You’re going to take this thing,” said Barton, holding up a fluorescent orange plastic triangle, “and drop it right out there,” pointing to the middle of the road.

Twombly didn’t want to go. There was so much lead flying through that road that it felt like suicide to venture from cover, much less run out to the middle. It crossed his mind to refuse Barton’s order, but just as quickly he rejected that. If he didn’t do it, somebody else would have to. That wouldn’t be fair. He had volunteered to be a Ranger, he couldn’t back out now just because things had gotten rough. He grabbed the orange triangle angrily, ran out a few steps, and flung it toward the center of the road. He dove back to cover.

“That won’t do it,” Barton shouted at him. He explained that the rotor wash from the birds on their gun runs would blow the marker away.

“You have to secure it, put a rock on it.”

Furious now, and terribly frightened, Twombly put his head down and ran out into the road again.

Nelson remembers feeling moved by his friend’s courage. The second Twombly took off again there was shooting on the street and so much dust kicked up Nelson couldn’t see him. That’s the last time I’ll ever see Twombly. But moments later the big man from New Hampshire came clomping back in, swearing fluently, unscathed.

An old man stumbled out from behind a wall wildly firing an AK. Rangers from all three corners were pointing guns at this man, who looked frail and had a shock of white hair and a long bushy white beard that was stained greenish on both sides of his mouth, presumably from khat. He was evidently drunk or stoned or so high that he didn’t know what was happening. His rounds were so off target the Rangers watching him at first were just stunned, and then laughed. The old man made a stumbling turn and fired a round into the wall, far from any targets. Twombly flattened him with a burst from his SAW.

They saw strange sights as the fight wore on. In the midst of cascading gunfire, Private David Floyd watched a gray dove land in the middle of Marehan Road. The bird scratched at the dirt nonchalantly and strutted a few feet up the road seemingly oblivious to the fury around it. Then it flew away. Floyd wistfully watched it go. A donkey pulling a wagon wandered across the intersection up the hill, through one of the heaviest fields of fire (near where Fillmore had been killed), and crossed the road unscathed, then came trotting back out again minutes later, clearly confused and disoriented. It was comical. Nobody could believe the donkey hadn’t been hit. Ed Yurek watched with pity, and amazement. God loves that donkey. Closer to the wrecked helicopter, a woman kept running out into the alley, screaming and pointing toward the house at the southeast corner of the intersection where many of the wounded had been moved. No one shot at her. She was unarmed. But every time she stepped back behind cover a wicked torrent of fire would be unleashed where she pointed. After she’d done this twice, one of the D-boys behind the tail of Super Six One said, “If that bitch comes back, I’m going to shoot her.”

Captain Coultrop nodded his approval. She did, and the D-boy shot her down on the street.

Then there was the woman in a blue turban, a powerful woman with thick arms and legs who came sprinting across the road carrying a heavy basket in both arms. She was wearing a bright blue-and-white dress that billowed behind her as she ran. Every Ranger at the intersection blasted her. Twombly, Nelson, Yurek, and Stebbins all opened up. Howe fired on her from further up the hill. First she stumbled, but kept on going. Then, as more rounds hit her, she fell and RPGs spilled out of her basket onto the street. The shooting stopped. She had been hit by many rounds and lay in a heap in the dirt for a long moment, breathing heavily. Then the woman pulled herself up on all fours, grabbed an RPG round, and crawled. This time the massive Ranger volley literally tore her apart. A fat 203 round blew off one of her legs. She fell in a bloody lump for a few moments, then moved again. Another massive burst of rounds rained on her and her body came further apart. It was appalling, yet some of the Rangers laughed. To Nelson the woman no longer even looked like a human being; she’d been transformed into a monstrous bleeding hulk, like something from a horror movie. Later, just before it got dark, he looked back over. There was a large pool of blood on the street, blood and clothing and the basket, but the RPG rounds and what remained of the woman were gone.

When the sun had slipped behind the buildings to the west, shadow fell over the alley and it became easier for Stebbins and Heard to find the Sammies who were shooting at them from windows and doorways. Their muzzle flashes gave their positions away clearly. Stebbins squeezed off rounds carefully, trying to conserve ammo. Heard was shooting now with an M-16. Nearly deaf, he tapped Stebbins on the shoulder and shouted, “Steb, I just want you to know in case we don’t get out of this, I think you’re doing a great job.”

Then the ground around them shook. Stebbins heard a shattering Kabang! Kabang! Kabang! the sound of big rounds smashing into the stone wall of the corner where they had taken cover. He was engulfed in smoke. The wall that had been their shield for more than an hour began to come apart. Somebody with a big gun down the alley had zeroed in on them, and was just taking down their position. After the first shattering volley, Stebbins stepped out into the alley and returned fire at the window where he had seen the muzzle flash. Then he ducked back behind his corner, took a knee, and kept placing rounds in the same place.

Kabang! Kabang! Kabang! Three more ear-shattering rounds hit the corner again and Stebbins was knocked backward and flat on his ass. It was as though someone had pulled him from behind with a rope. He felt no pain, just a shortness of breath. The explosions or the way he had slammed into the ground had sucked the air right out of him. He was dazed and covered once again with white powder from the pulverized mortar of the wall. He felt angry. The son of a bitch almost killed me!

“You okay, Stebby? You okay?” asked Heard.

“I’m fine, Brian. Good to go.”

Stebbins stood up, infuriated, cursing at full throttle as he stepped back out into the alley and resumed firing at the window.

Sergeant Howe, the Delta team leader, watched with amazement from further up the street. He couldn’t believe the Ranger didn’t have the good sense to find better cover. To Nelson, it looked like somebody had flipped a switch inside Stebbins. For the second time that hour he thought Stebbins had been killed. But the mild-mannered office clerk bounced back up. He was a changed man, a wild animal, dancing around, shooting like a madman. Nelson, Twombly, Barton, and Yurek were all shooting now at the same window, when there came a whooosh and a cracking explosion and both Stebbins and Heard screamed and disappeared in a ball of flame.

That’s it for Brian and Stebby.

Stebbins woke up flat on his back again. He had the same feeling as before, like he’d been punched in the solar plexus. He gasped for air and tasted dust and smoke. Up through the swirl he saw darkening blue sky and two clouds. Then Heard’s face came swimming into view.

“Stebby, you okay? You okay, Stebby?”

“Yup, Brian. I’m okay,” he said. “Just let me lay here for a couple of seconds.”

“Okay.”

This time, as he gathered his thoughts, common sense intruded. They needed help at this spot. More of the corner had been blown away. Stebbins figured he’d been hit in the chest by stones flying off the wall, enough to knock him over and out, but not enough to penetrate his body armor and seriously hurt him. The Sammies had set up some kind of crew-served weapon and it was going to take more than an M-16 to silence it. As he got back up, he heard Barton across the alley radioing for help. Then a voice came from ear level, right behind Stebbins. One of the D-boys was in the window of the corner building, the same window Nelson had fired at earlier. The voice sounded cool, like a surfer’s.

“Where’s this guy shooting from, dude?”

Stebbins pointed out the window.

“All right, we’ve got it covered. Keep your heads down.”

From inside the building, the Delta marksman fired three 203 rounds, dropping them right into the targeted window. There was an enormous blast inside the building. Stebbins figured the round had detonated some kind of ammo cache, because there was a flash throughout the first floor of the building too bright and loud for a 203 round. After that it went dark. Black smoke poured from the window.

It got quiet. Stebbins and Heard and the guys across the alley shouted their congratulations to the D-boy for the impressive shot. Back on one knee a little further behind the chewed-up wall, Stebbins watched some lights flick on in the distance and was reminded that they were in the middle of a big city, and that in some parts of the city life was proceeding normally. There were fires burning somewhere back toward the Olympic Hotel, where they had roped in. It seemed like ages ago. He thought now that it was dark, maybe the Sammies would all put down their weapons and go home, and he and his buddies could walk back to the hangar and call it a night. Wouldn’t that be nice?

A voice shouted across the intersection that everyone was to retreat back toward the bird. As darkness fell, the force was going to move indoors. One by one, the men on his corner sprinted across the intersection. Stebbins and Heard waited their turn. The volume of fire had died down. Okay, the big part of the war is over.

Stebbins then heard a whistling sound, and turned in time to see what looked like a rock hurtling straight at him. It was going to hit his head. He ducked and turned his helmet toward the missile, and then he vanished in fire and light.

Sergeant Fales, the wounded PJ, got a radio call for a medic. They needed somebody fast across the wide intersection west of the downed helicopter. Private Rodriguez was bleeding badly from the gunshot wound to his crotch. The men were all falling back into the various casualty collection points. The medic Kurt Schmid was in the courtyard up the road working on Corporal Smith. No one on the other side of Marehan Road had the skills to deal with an injury as severe as Rodriguez’s. Fales was propped up behind the Kevlar plates near the tail boom of the helicopter, his hastily bandaged leg stretched out useless before him.

His buddy Tim Wilkinson, who was working on some of the wounded alongside him, had been making him laugh. The two air force medics had long commiserated over how unlikely they were to see real combat on this deployment. Wilkinson had just tapped Fales on the shoulder as the bullets flew overhead and said, “Be careful what you wish for.”

Wilkinson was still working under the impression that the ground convoy (long since returned broken and bleeding to base) was going to arrive at any moment. He felt his job was to get all the wounded patched up and on litters, ready to be loaded up as soon as the trucks arrived. When he’d instructed Fales to get on a stretcher earlier that afternoon, the master sergeant had balked.

“Hey, you know the deal. Get on!” Wilkinson insisted.

Fales had climbed on reluctantly and had been strapped down, but as time wore on and the vehicles didn’t show, Fales worked himself free of the straps, retrieved his weapon, and resumed firing. Now he heard the call from across the street.

“They need a medic, Wilky.”

Bullets and RPG rounds formed a deadly barrier between their position and the men across Marehan Road. Wilkinson folded up his medical kit and moved toward the intersection. Then he stopped. If he was afraid, he had simply filed the emotion away. Ever since the rounds had peppered the inside of the helicopter, filling it with a little snowstorm of dust and debris, Wilkinson had just stopped worrying about bullets and focused on his job, which was demanding enough to block out everything else. He worked quickly and with purpose. There were more things to do than he could get done. It was as though he couldn’t think about both things, about both the danger and the work. So he concentrated on the work. Now he turned to his friend and deadpanned an absurd and deliberately cinematic request.

“Cover me,” he said.

And he ran, and ran, plowing across the wide road, head down as the volume of fire suddenly surged. Wilkinson’s buddies would later joke that he wasn’t shot because he was so slow the Sammies had all miscalculated his speed and aimed too far in front of him. To the medic, it just felt like he had willed himself safely across the street. Once inside the Delta command-post courtyard he began to assess the wounded, making quick triage decisions. It was obvious Rodriguez needed help first. He was bleeding heavily, and very frightened. Wilkinson tried to calm him.

The medic cut open Rodriguez’s uniform to assess the damage. Rodriguez had been hit by a round that entered his buttock and bored straight through his pelvis, blowing off one testicle as it exited through his upper thigh. The first goal was to stop Rodriguez from bleeding out. If his femoral artery had been hit (as with Smith, across the street), he knew there wasn’t much chance of stopping the bleeding. Wilkinson began applying field dressings, stuffing wads of Curlex into the gaping exit wound. He wrapped the area tightly with an Ace bandage. Wilkinson then slipped rubber, pneumatic pants over Rodriguez’s legs and pelvis, and pumped them with air to apply still more pressure to the wound. The bleeding stopped. He dosed Rodriguez with morphine and started an IV to replenish fluids, which he quickly exhausted trying to get the private stabilized.

He radioed over to Fales, “You guys got any more fluids?”

They did. Wilkinson told them to just bag them up and toss them as far as they could in his direction. He watched across the street as one of the men there wound up for the heave, and realized that was a bad idea. He called back over and told them not to throw it. If the contents broke open, or were hit by a round, they’d waste precious fluids. If the bags spilled out, he’d be stuck in the middle of Marehan Road gathering it all up. He decided it would be better to brave the road twice at full speed than stop in the middle of it.

He ran across, again moving at what seemed tortoise pace, and again arriving unscathed. The men watching from their positions hunkered down around the intersection were amazed at Wilkinson’s bravery. Wilkinson told Fales that he would have to go back for good this time. Rodriguez was in a critical state. He needed to be taken out immediately. Wilkinson would care for him until that happened. Then, with the fluids cradled in his arms, head down, he dashed across the road for the third and last time. Again, he arrived unhurt.

As he burst back into the courtyard, one of the D-boys told him, “Man, God really does love medics.”

It was fast growing dark. Wilkinson got help moving Rodriguez and the others into a back room. He learned then that the convoy coming to rescue them had turned back, and that they were going to be spending the night.

Wilkinson sought out Captain Miller.

“Look, I’ve got a critical here,” he said. “He needs to get out right now. The others can wait, but he needs to come out.”

Miller gave him a look that said, We’re in a bad spot here, what can I say?

Specialist Stebbins had his eyes closed but he still saw bright red when the grenade exploded. He felt searing flames and then he just felt numb.

He smelled burned hair and dust and hot cordite and he was tumbling, tumbling, mixed up with Heard, until they both came to rest sitting upright staring at each other.

“Are you okay?” Heard asked after a long moment.

“Yeah, but I don’t have my weapon.”

Stebbins crawled back to his position, looking for his weapon. He found it in pieces. There was a barrel but no hand grip. The dust was still thick in the air; he could feel it up his nose and in his eyes and could taste it. He could also taste blood. He figured he’d busted his lip.

He needed another weapon. He stood up and started for the door of the courtyard where the D-boys were holed up, figuring he’d grab one of the wounded’s rifles, but he fell down. He got up and took a step and then fell down again. His left leg and foot felt like they were asleep. After falling the second time he walked, dragging his leg, toward the courtyard. He found his buddy Heard standing in the doorway telling one of the D-boys, “My buddy Steb is still out there.”

Stebbins put his hand on Heard’s shoulder.

“Brian, I’m okay.”

Wilkinson grabbed hold of Stebbins, who looked a fright. He was covered with dirt and powder and dust, his pants were mostly burned off, and he was bleeding from wounds up and down his leg. He was groggy and seemed not to have noticed his injuries.

“Just let me sit down for a few minutes,” Stebbins said. “I’ll be okay.”

The medic helped Stebbins limp into the back room where the other wounded were gathered. It was dark, and Stebbins smelled blood and sweat and urine. The RPG that had exploded outside had briefly set fire to the house, and there was a thick layer of black smoke now hanging from the ceiling about halfway to the floor. The window was open to air things out, and everyone was sitting low. There were three Somalis huddled on a couch. Rodriguez was in the corner moaning and taking short, loud sucking breaths. He had an IV tube in his arm and these weird inflated pants around his middle. Fucking got his dick shot off.

Heard was arguing with a medic, “Look, I’ve just got a little scratch on my wrist. I’m fine. Really. I should put a bandage on it and go back.”

The Somalis moved to the floor and Wilkinson eased Stebbins down on the couch and began cutting off his left boot with a big pair of shears.

“Hey, not my boots!” he complained. “What are you doing that for?”

Wilkinson slid the boot off smoothly and slowly, removing the sock at the same time, and Stebbins was shocked to see a golf ball–sized chunk of metal lodged in his foot. He realized for the first time that he’d been hit. He had noticed that his trousers looked burned and singed, and now, illuminated by the medic’s white light, he saw that the blackened flaking patches along his leg were skin! He felt no pain, just numbness. The fire from the explosion had instantly cauterized all his wounds. He could see the whole lower left side of his body was burned.

One of the D-boys poked his head in the door and gestured toward the white light.

“Hey, man, you’ve got to turn that white light out,” he said. “It’s dark out there now and we’ve got to be tactful.”

Stebbins was amused by that word, “tactful,” but then he thought about it—tactful, tact, tactics—and it made perfect sense.

Wilkinson turned off the white light and flicked on a red flashlight.

Stebbins thrust his hand back into his butt pack for a cigarette, and found the pack had been burned as well. Wilkinson wrapped Stebbins’s foot.

“You’re out of action,” he said. “Listen, you’re numb now but it’s gonna go away. All I can give you is some Percocet.” He handed Stebbins a tablet and some iodized water in a cup. Wilkinson also handed him a rifle. “Here’s a gun. You can guard this window.”

“Okay.”

“But as your health care professional, I feel I should warn you that narcotics and firearms don’t mix.”

Stebbins just shook his head and smiled.

He kept hearing sounds out the window, coming up the alley. But there was no one there. His mind was playing tricks on him. Once or twice he shouted in panic and blasted a few rounds at the window, but it was just shadows.

Stebbins’s outbursts and the blast of occasional RPG hits against the outside wall roused Rodriguez from his morphine reverie. He laughed and shouted out the window what bad shots the Somalis were. As bad as his wound was, he felt no pain, just discomfort. The rubber pants had the lower half of his body in a vise. He asked Wilkinson once or twice if he would release some of the pressure. The medic said no.

One of the D-boys came in and asked Stebbins where the RPG had come from that got him, which direction? Stebbins wasn’t sure.

“From down the alley west,” he said.

But that had been the direction he was facing, and his injuries were all on his back side. Then Stebbins remembered he had turned and looked back when he had seen it coming at him. It must have come from behind him.

“No, east. Not from over the bird though,” he said. “From further up the street.”

Finally he was left to sit there alone, his pants blown off, clutching his rifle, listening to Rodriguez breathing steadily and to the Somali woman complaining with words he didn’t understand that her husband’s flex cuffs were too tight. He realized he had to urinate badly. There was no place to go. So he just released the flow where he sat. It felt great. He looked up at the Somali family and gave them a weak smile.

“Sorry about the couch,” he said.

Still out on the street one and a half blocks south, Private David Floyd was shooting at everything that moved. At first he had hesitated firing into crowds when they massed downhill to the south, but he had seen the Delta guy, Fillmore, get hit, and Lieutenant Lechner, and about three or four of his other buddies, and now he was just shooting at everybody. The world was erupting around him and shooting back seemed the only sensible response. But no matter how many rounds he and Specialist Melvin DeJesus poured down Marehan Road, the crowds kept on creeping in. Out in the street, still flat in his little dip in the middle of the road, Specialist John Collett was doing the same. They were the southernmost point on the perimeter and had no idea what was happening down around the crash site, or anywhere else for that matter. When Floyd hit someone with rounds from his SAW, he could see their bodies begin to twitch, like they were being zapped with electricity. They would usually make it only a step or two more before falling over.

A bullet or a casing or something hit him. Floyd jumped a foot. He felt down, afraid to take his eyes off the road ahead, and found that his pants had been ripped from his crotch to his boot, but the round hadn’t even scratched him. It had evidently come through the tin wall.

“Whooo!” he said, looking over at DeJesus, grateful and frightened.

His ears were ringing but for some reason he could still hear. DeJesus was starting to freak out. He was getting jumpier and jumpier, saying he couldn’t stay there anymore. He had to move. He and Floyd had felt safe for a time pressed behind the tin shed wall on the west side of the road in shadow, but as it grew darker now, DeJesus wasn’t staying low. He was up on his feet, hopping up and down. He said he had to do something. He had a bad feeling. He had to be somewhere else. Now!

Floyd felt like slapping him.

“Sit yer ass down!” he screamed at him.

As it happened, across Marehan Road men were waving them into the courtyard. Captain Steele had given up for the time being catching up to Lieutenants Perino and DiTomasso in the next block. He wanted all the men at this southern end of the perimeter to consolidate in the courtyard. Already there were three Delta teams and a number of wounded in the small space, including Neathery and Errico, who both had gunshot wounds to their biceps, and Lechner, who was still howling with the pain of his shattered right lower leg. Goodale was still working the radio while a medic stuffed Curlex into the exit wound in his buttock. The courtyard was a haven, but the wide road that separated Floyd, DeJesus, and the other members of Chalk Three from it loomed like an impassable gulf.

One by one, they ran for it. Private George Siegler went first. Then Collett jumped up from his spot in the middle of the road and sprinted for the door. Private Jeff Young, his big glasses bouncing on his nose and long legs pumping high, made it across next. As each man ran, Floyd and DeJesus, who had settled down again, blasted rounds to the south to provide covering fire. Finally, only Floyd and DeJesus were left.

“You’re gonna run across that road,” Floyd told his buddy.

DeJesus nodded.

“But, listen here. When you get across, don’t you go through that doorway, see? You turn around and start shooting, because as soon as you’re across, I’m coming. Okay?”

DeJesus nodded. Floyd wasn’t at all sure he’d gotten through.

He must have blasted fifty rounds as DeJesus ran. And his friend didn’t forget. Before entering the courtyard, DeJesus turned, dropped to one knee, and started shooting. Floyd felt like he had lead in his boots as he ran. His torn pants were flapping around him like a skirt, and he wasn’t wearing any underwear, so he felt naked in more ways than one as his legs churned up the road. It seemed like the doorway to the courtyard was actually receding while he ran.

But he made it.

Across the city, back at the Ranger’s airfield base an hour or so earlier, the truckloads of injured and dead off the lost convoy had arrived. This was the kind of catastrophe Major Rob Marsh had long planned for, hoping he would never see. He had entered the army in 1976 as a Special Forces medic, and then had gone on to medical school at the University of Virginia. His father, John Marsh, was then Secretary of the Army. Marsh was working as a flight surgeon in Texas when he had met General Garrison. The two had hit it off. A few years later, as Delta commander, Garrison invited Marsh to be the unit’s surgeon—no doubt mindful of the family connection. Marsh said no, fearing that the offer might have more to do with his father than his medical skills. But when the offer was renewed about a year later, he’d accepted. He’d been doctoring for the unit ever since, eight years now.

One of Marsh’s proudest innovations were four large trauma chests, four-by-two-foot trunks, packed with IV fluid bags, gauze, Curlex, petroleum jelly, needles, chest tubes ... all the things needed for initial treatment of wounds. Instead of just filling the chests with the equipment, Marsh and his staff had packaged fifteen separate Ziploc bags in each trunk, five serious-wound packets and ten for lesser wounds. The idea was to assess the seriousness of an injury, then grab the appropriate packet. Marsh had seen British forces do that during the Falkland Islands war. Delta had been lugging the trunks around with them now for years, not always happily. Officers had complained about how much space the trunks took up on pallets, and more than once had tried to have them removed. In Marsh’s experience, it was always officers with actual combat experience like Garrison who would step in to save his chests. Now, for the first time, they needed them.

Marsh had been hovering around the JOC all afternoon as the mission deteriorated. At first, Garrison had been in the back of the room, chewing on his unlit cigar, listening and watching quietly. He was not one to interfere. Some top commanders insisted on calling most of the shots themselves, but Garrison wasn’t like that. When they’d begun this deployment, the general had given a little speech explaining that, for the first time in his career, he’d been given command of men he felt he didn’t need to lead. They knew how to lead themselves. Garrison told them his job was just to supply them with what they needed and stay out of their way. But as things began going wrong, the general had moved to the front of the room.

Marsh had to leave the JOC to tend to Private Blackburn—who had not, as the medic had feared, broken his neck when he fell from the Black Hawk. The young Ranger had suffered head and neck trauma, and had a few broken bones. Marsh was working on him when he got word that a Black Hawk was down in the city. When he returned to peek into the JOC, there was an anxious buzz about the place. Commanders seemed fixated on the TV screens. Garrison was fully engaged. Things had clearly gone amok.

The army field hospital at the U.S. embassy was alerted to be ready for casualties. There was some discussion about sending men directly there, but it was decided to do the primary care at Marsh’s tent. He was ready. He had two surgeons, a nurse anesthetist, and two physician assistants. Nurses from the adjacent air force mobile surgical facility also volunteered to help. There would be a triage area just outside the tent. The most urgent cases would go directly inside. Those who could wait would go to a holding area out back. Those who were “expectant,” near death and beyond help, would go to a separate spot near the ambulance, away from the other wounded. Marsh had designated his unit’s ambulance for the dead. It was cool in there. The bodies would be out of the sun and out of view. Pilla’s body was already there.

When the convoy pulled up it was like a scene out of some nightmarish medieval painting. The back of one of the five-tons opened on a mass of bleeding, wailing, moaning men. Griz Martin sat to one side holding his entrails in his hands, his legs shattered, awake but groggy. There hadn’t even been time in most cases for the wounds to have been bandaged. Marsh had just seconds to make a judgment call on each as the litter bearers lifted them out. Private Adalberto Rodriguez, who had been blown up and run over, went into the tent. A Delta sergeant, whose left calf had been shot off, went out back to wait. Into the tent went Sergeant Ruiz, who had a sucking wound in his chest. Some of the wounded Rangers were dazed. They wandered around the triage area, sputtering angrily. Marsh noted they all were still carrying weapons. He asked the chaplain to start gathering those guys and talking to them.

Delta medic Sergeant First Class Don Hutchinson confronted Marsh about Griz. Hutch and Griz were close.

“He’s hurt real bad, Doc.”

Some of the other D-boys had come over to be with Griz, who was semiconscious with what Marsh recognized as a clearly nonsurvivable injury. His midsection was basically gone, and when Marsh tried to turn him over, he saw the whole back of his pelvis had been blown off. Griz was in shock level three going into four. His skin was pasty pale. He’d obviously lost a tremendous amount of blood. It was amazing that he was still alive, much less semiconscious, but when Marsh took his hand, Griz gripped it as hard as the doctor’s hand had ever been gripped. He should have labeled him “expectant,” or certain to die, and sent him back by the ambulance, but with all the guys from the unit pressing in, urging him to do something, Marsh felt compelled to act. He felt sure it was hopeless, but they’d give Griz a full-court press anyway.

Marsh sent into the tent Private Kowaleski, the Ranger driver whose torso had been penetrated by the unexploded RPG. Amazingly, he still had vital signs. Inside, Captain Bruce Adams, a general surgeon, examined the broken body of the soldier and recoiled at what he found. Kowaleski’s left arm was gone—one of the air force nurses would find it, to her horror, in his pants pocket where Specialist Hand had placed it. Adams began working to restore Kowaleski’s breathing while a nurse removed his clothing. They found the entrance wound of the RPG on one side of his chest, and, lifting a flap of skin under his right arm, Adams saw the tapered front end of the grenade.

Marsh came by for a quick second assessment and told Adams, “This guy’s expectant. Don’t waste any more time on him.”

Assigned to help carry the nearly dead man back out was Sergeant First Class Randy Rymes, a munitions expert. It was Rymes who recognized that Kowalewski had a live bomb embedded in his chest. The detonator was on the tip, just under his right arm. Instead of taking him out by the ambulance, Rymes and another soldier built a sandbag bunker and placed Kowalewski’s body inside it. Rymes then stretched out beside the bunker on his stomach and reached his hand around to delicately remove the tip of the grenade from under the man’s skin.

While all this was going on, commanders inside the JOC had watched with horror as triumphant Somalis overran the site of the second Black Hawk crash, pilot Mike Durant’s, and were now getting frantic calls for a chopper to medevac Smith and Carlos Rodriguez from the first crash site. They had ninety-nine men pinned down in the city, and no rescue force on its way. They knew it would be foolhardy to try to put another Black Hawk down there to evacuate the two badly injured Rangers. The volume of fire was much heavier there than anywhere else in Mogadishu, and the Somalis had already shot down four Black Hawks. Garrison had pilots who were willing to try, but there was no point in getting more men killed trying to save two.

It had been easy to believe, prior to this day, that the Somali warlord Aidid lacked broad popular support. But this fight had turned into something akin to a popular uprising. It seemed like everybody in the city wanted suddenly to help kill Americans. There were burning roadblocks everywhere. It was obvious Aidid and his clan had been waiting for the right moment, and this was it. At the second crash site, seen from high overhead, there was no sign of Shughart, Gordon, Durant, or the Super Six Two crew, only busy crowds of excited Skinnies still swarming over the wreckage. There was a brief flurry of hope when the observation birds picked up tracking beacons from Durant’s and his copilot Ray Frank’s flight suits, but it was quickly dashed when it became apparent that the beacons had been stripped from the pilots by canny Aidid militia and were being run all over the city to confuse the airborne search.

As for the men around the first crash site, they would be all right. Those ninety-nine were some of the toughest soldiers in the world. They were superbly trained, well-armed, and mean as hell. They owned that neighborhood and nobody was going to take it away from them, certainly no armed force in Mogadishu.

Unless they ran out of ammo, that is, or keeled over from dehydration. The C2 helicopter had begun calling for help shortly before dusk.

—Need a resupply ... IV bags, ammo, and water. ... Obviously we need them to hurry as fast as they can. Our boys on the ground are running out of bullets.

—Romeo Six Four [Harrell], this is Adam Six Four [Garrison]. You want us to put resupply on a helo?

—If you can. Put resupply on a helo. Try to take it out to the northern crash site. They’re running out of ammo, IV bottles, and water, over.

Few of the Rangers had even bothered to take full canteens. They had been running and fighting now in sweltering heat for several hours. If they were going to make it through the night they would need more than skill and willpower. So even though it risked turning a bad situation worse, Garrison ordered a Black Hawk in. They could drop water and ammo and medical supplies, and, if possible, land and pull the two critical Rangers out. In the JOC, most of the officers believed the helicopter would be shot out of the sky. It would most likely crash-land right there on Marehan Road. Either way, the men on the ground would get their ammo and water.

Black Hawk Super Six Six, piloted by Chief Warrant Officers Stan Wood and Gary Fuller, moved down through the night just after seven o’clock, guided by infrared strobe lights set out on the wide street just south of the crash site. As the helicopter descended, machine-gun fire erupted again from points all around the Ranger perimeter, and RPGs flew. The men inside courtyards and houses were startled by how close the gunfire was to their positions, in some cases on the other side of the walls. The rotor wash from the Black Hawk kicked up a furious sandstorm.

It hovered for about thirty seconds, which was about twenty-eight seconds too long as far as Sergeant Howe was concerned. He held his breath as the deafening bird hung over the block, afraid that it was going to pancake in on them. Delta Sergeant First Class Alex Szigedi, who had survived the lost convoy earlier that afternoon, now hustled in the back of the helicopter with another operator to shove the kit bags filled with water, ammo, and IV bags overboard. The helicopter was getting riddled. Szigedi was hit in the face. Bullets poked holes in the rotor blades and the engine, which began sprouting fluids. One round passed through the transmission gearbox. Super Six Six kept flying. As it pulled up and away, men scurried out of the buildings to retrieve the new supplies.

Back in the JOC they heard Wood announce, calmly:

—Resupply is complete.

The stranded force had been tucked in for the night.

The fight now raged around three blocks of Mogadishu real estate. The block immediately south of the crash was occupied in two places. The CSAR team and Lieutenant DiTomasso’s Chalk Two Rangers, about thirty-three men in all, had moved in through the wall knocked over by Super Six One on its way down. They had begun spreading out to adjacent rooms and courtyards to the south. Abdiaziz Ali Aden was still hiding in one of those back rooms. Lieutenant Perino had led his men into a courtyard on the same block through a door on the east side of Marehan Road. He and about eight other soldiers were grouped where Sergeant Schmid was still working on Corporal Smith, who was slowly fading away. Perino still wasn’t sure where the downed bird was or how close they were to DiTomasso, although they were separated now by only a few feet. Captain Miller and his contingent of D-boys and wounded Rangers were in the courtyard Howe had cleared on the west side of Marehan Road. Miller’s twenty-five men had spread out into that block, moving into rooms off the courtyard. The third block was across a wide alley south on the same side of the street as Perino. There, in the courtyard they’d sought shelter in earlier, Captain Steele and three Delta teams were still stuck, unable to push further down toward the wreck.

This ungainly distribution of forces was problematic. The Little Bird pilots, who were making frequent gun runs, were having a hard time clearly delineating friendly force locations from targets. From the C2 Black Hawk high above, Lieutenant Colonel Harrell radioed a request to Captain Miller.

—Scotty, is it possible for you to get everybody in one small tight perimeter? The problem we have is everyone is spread out. It’s hard to get close accurate fire into you. And mark your location. We need to know exactly where you are. Is there any way you can accomplish that, over?

Miller explained that Steele seemed reluctant to move up, and that the Delta teams with Steele were also pinned down by heavy fire.

—Roger, I know it’s tough and you’re doing the best you can but try to get everyone at one site and have one guy talking down there if you can.

Miller conveyed the request to the team leaders cornered with Steele. Then, just before dark, he ordered Sergeant Howe to move across Marehan Road and into the courtyard opposite in order to improve their coverage of the street. Howe thought it was a poor idea. It did nothing he could see to improve their position. He’d been out on the street for long periods earlier, and had a plan of his own. Steele and the others stranded at the southernmost tip of this awkward perimeter should move up and consolidate with them. This would shorten the long leg of the “L,” give them a single strong position to hold, and give the Little Birds a clearly defined one-block area to work around. They could then establish strong interlocking fire positions at each of the key intersections, both in front of and behind the downed bird, and at the south end of the block. Looking around outside, Howe had seen three buildings that could be taken down and occupied, which would have expanded their fire perimeter. A two-story house at the northwest corner of the intersection off the bird’s tail would have provided a shooting platform that could push the Somali gunmen to the north several blocks further out. Howe felt this was so obviously the way to go it surprised him that the ground commanders hadn’t begun it already. Instead, as Howe saw it, they seemed overwhelmed. They had followed him into the courtyard and then squatted there, just as Steele was now squatting in a worthless position off to the south. Everything in Howe’s training said that survival depended on proactive soldiering. You constantly assessed your position and worked to improve it.

Howe knew there was no point arguing. He and the three men on his team ran across the road in groups of two. They barged through the front door of a two-room house and cleared it. There was no one inside. Through a barred window in back Howe saw Perino and his group. One of Howe’s team members knocked out the bars and just pushed down the flimsy stone wall to open up a passage into their space. Perino and Schmid strapped the dying Corporal Smith to a board and passed him through the window into the room. There they would be sheltered from grenades lobbed over the walls.

As far as Howe was concerned, his position sucked. From the doorway, he could see only the corners of the alleyways to the south and north. Far from expanding their field of fire, he could see no more than twenty yards out in each direction!

Just listening to the shouted questions and commands on the radio, Howe sensed that some of those in charge were out of their depth. There was just too much going on. He could see it in their faces. Sensory overload. When it happened you could almost see the fog pass over a man’s eyes. They just withdrew. They became strictly reactive.

Take the vaunted Rangers. Some of the Rangers were out there in the fight, but nobody was telling them what to do, and they sure as hell didn’t know. Most of them were holed up in back rooms of the house one block south with their commander, Steele, waiting to see what was going to happen next. Howe figured there were more than two dozen capable men and several heavy weapons back there in that house. What the hell were they doing? That was one thing he and Miller and even the commanders overhead seemed to agree on at least. Steele and his Rangers needed to pick up their wounded and move fifty fucking yards down the slope to consolidate the perimeter and join the fucking fight! But Steele wouldn’t budge. It was as if the Rangers saw the D-boys as their big brothers, and since their big brothers were around, everything would be okay.

Shooting quieted down after the moon came up. It cast faint shadows out on the street. The Little Bird gun runs lit up the sky with tracers and rockets. Brass from their miniguns rained down on the tin rooftops like somebody banging on the side of an empty metal bucket. There were bodies of Somalis still stretched out on the road. Howe had noticed that the Sammies were good about hauling off their wounded and dead. Bodies tended not to stay put unless they were right in the middle of the street. Weapons, too. If there was a weapon down on the ground, it would be gone eventually unless it was broken. They were smart street fighters. Howe felt a grudging professional admiration. They were disciplined, and what they lacked in sophisticated weapons and tactics they made up for with determination. They used concealment very well. Usually all you saw of a shooter was the barrel of his weapon and his head. Once darkness fell and the amateurs went home, the firing became less frequent but more accurate.