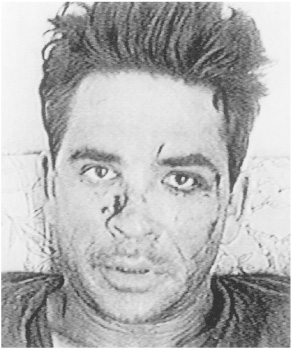

Mike Durant as he appeared on the videotape shot by his Somali captors the day after he was shot down and taken captive. Courtesy: Cable News Network. Copyright © 1998 Cable News Network, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

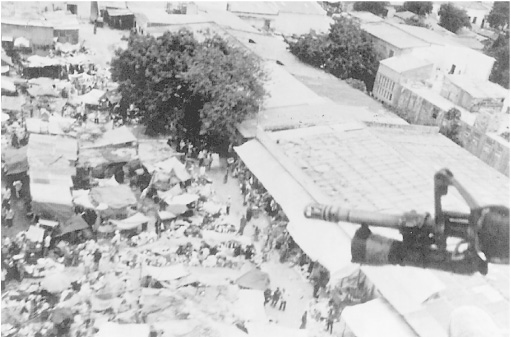

View from a Black Hawk doorway over one corner of Mogadishu’s Bakara Market. Courtesy: Lance Twombly.

Enraged Somalis drag the body of Black Hawk crew chief Bill Cleveland through the streets of Mogadishu the morning after the battle. Courtesy: Paul Watson/The Toronto Star.

Michael Durant heard the guns of the giant rescue convoy roaring into the city. The injured Black Hawk pilot was flat on his back bound with a dog chain on a cool tile floor in a small octagonal room with no windows. Air, moonlight, and sounds filtered in through a pattern of crosses cut high in the upper third of the concrete walls. He tasted dust in the air and he smelled of blood and gunpowder and sweat. The room had no furniture and only one door, which was closed.

When the angry mob had closed over him, he thought he was going to die. He still did not know the fate of the three other men on his crew, copilot Ray Frank and crew chiefs Tommy Field and Bill Cleveland, or of the two D-boys who had tried to protect them. Durant did not know those men’s names.

He had passed out when the mob carried him off. He’d felt himself leaving his body, watching the scene from outside himself, and at the worst of the chaos and terror it had calmed him. But the feeling hadn’t lasted. He’d come to when he was thrown into the back of a flatbed truck with a rag tied around his head, surprised to still be alive and expecting at any moment to die. He was driven around. The truck would go and then stop, go and then stop. He guessed it was about three hours after the crash when they’d brought him to this place, removed the rag, and wrapped his hands with the chain.

What Durant didn’t know was that he had been taken from the first group of Somalis who seized him. Yousef Dahir Mo’alim, the neighborhood militia leader who had spared him from the attacking crowd after it had overwhelmed and killed the others, had intended to carry Durant back to his village and turn him over to leaders of the Habr Gidr. As they’d left the crash site, however, they were stopped by a better-armed band of maverick mooryan, who had a technical with a big gun in back. This group considered the injured pilot not a war prisoner to be swapped for captured clan leaders, but a hostage. They knew somebody would pay money to get him back. Mo’alim’s men were outnumbered and outgunned, so they’d reluctantly given Durant up. This was the way things were in Mogadishu. If Aidid wanted the pilot back, he would have to fight for him, or pay.

Durant’s right leg ached where the femur was broken and he could feel the ooze of blood inside his pants where one end of the broken bone had pushed through his skin in the manhandling. It did not hurt that badly. He didn’t know if that was good or bad. He was still alive, so the bone had not punctured an artery. His back was what really bothered him. He figured he’d crushed a vertebrae in the crash.

He managed to work one hand free of the chain. He was sweating so his hand slid out easily when he relaxed it. It gave him his first sense of triumph. He had fought back in some small way. He could wipe the dirt from his nose and eyes and straighten his broken leg somewhat and get a little more comfortable. Then he wrapped his hand back into the chain so that he still appeared to be bound.

At one point he heard several armored vehicles roll right past outside. He heard shooting and thought he was about to be rescued, or killed. There was a furious firefight. He heard the low pounding of a Mark 19 automatic grenade launcher and the explosion of what sounded like TOW missiles. He had never been at the receiving end of a barrage and he was shaken by how powerful and frightening it was. The explosions came closer and closer. The Skinnies holding him grew more and more agitated. They were all young men with weapons that looked rusty and poorly maintained. He listened to them shouting at each other, arguing. Several times one or more barged into the room to threaten him. One of the men spoke some English. He said, “You kill Somalis. You die Somalia, Ranger.”

Durant couldn’t understand the rest of their words but he gathered they would shoot him before letting the approaching Americans take him back.

He listened to the pitched battle with hope and fear. Then the sounds marched off and faded. He felt disappointed, despite the danger. They had been so close!

Then a gun barrel poked around the door. Just the black barrel. Durant caught the motion in the corner of his eye and turned his head just as it flamed and the room rang with a shot. He felt the impact in his left shoulder and his left leg. Eyeing his shoulder, he saw blood and the back end of a bullet protruding from his skin. It evidently had hit the floor first and had ricocheted into him without enough force to fully penetrate. A bit of shrapnel had punctured his leg.

He slid his hand from the chain and tried to wrench the bullet from his shoulder. It was an automatic move, a reflex, but when his fingers touched it they sizzled and he winced with pain. It was still hot. It had burned his fingertips.

He thought: Lesson learned; wait until it cools down.

Word of the big fight in Mogadishu reached Washington early Sunday. General Garrison had received a call several hours into the battle from General Wayne Downing, an old friend who was commander in chief of U.S. Special Operations Command. Downing had come to his office at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa after a morning jog, and had decided to ring up his friend in Mogadishu to see how things were going. This was about two hours into the fight. Garrison quickly summarized what had happened so far: There had been a successful mission, two of Aidid’s lieutenants and a slew of lesser lights had been captured, but two helicopters were down, lots of lead was flying, and the boys were still in the thick of it. Downing asked Garrison if there was anything he could do right away, and then got off the phone. The last thing his friend needed at that moment was some desk jockey thirteen thousand miles away looking over his shoulder.

Downing spread the word. National Security Adviser Tony Lake was given the bare outline at the White House that morning, two Aidid lieutenants captured, two helicopters down, rescue operation underway. Lake was more preoccupied just then with events in Moscow, where Russian President Boris Yeltsin was fending off a right-wing coup d’état. President Clinton did not mention Mogadishu at a press conference that morning, which took place at the same time Task Force Ranger was pinned down around the first crash site. Clinton and the rest of America remained ignorant of the drama in faraway Mogadishu. After the press conference, the president flew to San Francisco for a planned two-day speaking tour.

Garrison’s move back into the city came with crushing force. If Aidid wanted to play, the U.S. Army would play. Centered around twenty-eight Malaysian APCs and four Pakistani tanks, the convoy numbered almost a hundred vehicles and was nearly two miles long, with enough firepower to blaze their own roads if necessary. Lieutenant Colonel Bill David was given responsibility for quickly assembling this force at the New Port, about two miles up the coast from the Ranger base.

David’s reaction, upon being handed this assignment, was, You’ve got to be kidding me. His own men, two 10th Mountain Division rifle companies, three hundred men strong, had amassed at the airport. David’s Charlie Company, the “Tigers,” had taken some light casualties at the K-4 circle ambush trying to get to Durant’s crash site, but they were otherwise fresh and eager to join the fight. They’d been joined by Alpha Company, under the command of Captain Drew Meyerowich. The armor would be nice, but what was David going to do with Malaysians and Pakistanis? He huddled with General Gile, second in command of the 10th. They agreed that once their men linked up with the foreign troops at the New Port, they would ask the Malaysians to take their own infantry out of the APCs and fill them with American troops. It would be, Thank you very much, we’ll take your vehicles and drivers, but we don’t need your men. David could sense how that was going to go over.

“Do these guys speak English?” he asked.

Most of the officers spoke some, Gile said, and there would be liaison officers to help smooth the process.

David had walked out of the JOC with his head spinning. The forty-year-old career army officer (West Point, Class of ’75) from St. Louis, Missouri, had just been handed the assignment of a lifetime. He had been in Mogadishu for two months, commanding a battalion of peacekeepers there to back up the UN forces. He’d never been particularly happy about the presence of Garrison’s Task Force Ranger, which had flown in and begun its own secret missions independent of the force structure already in place. Regular army units both admire and resent the elite special forces. The conventional divisions don’t get nearly as much money to train, or the choice assignments. Watching Task Force Ranger move into Mogadishu and steal their thunder was not easy for the proud officers and men of the 10th, which has its own distinguished battle history. Since the daring mission had gone bad, it was easy to regard it as foolhardy—What were they doing in Aidid’s notorious Black Sea neighborhood in broad daylight? Where was the reserve force? Now David and his men, sometimes scorned by the elite forces, were charged with pulling Delta’s and the Rangers’ asses out of the fire.

He had to move his men, along with what was now called the “Cook Platoon,” volunteers combined with the remnants of the original assault forces, north to the New Port, negotiate with the Malaysians and Pakistanis, develop a plan, and then allow for his subordinates to disseminate it up and down the giant convoy. Then he had to steer them out into the city and keep it all together in the dark as they battled their way to the two crash sites.

While the commanders were working up this plan, the Rangers assigned to the rescue column fretted and paced. Their buddies were still trapped out there! Those who had already been in the fight knew how terrible the battle had become. The uninjured had helped move their wounded and dead buddies from the lost convoy’s Humvees and trucks to the field hospital, where Dr. Marsh and his team of doctors and nurses were furiously working to save their lives. The Rangers known to be dead were Pilla, Cavaco, and Joyce. In bad shape were Blackburn, Ruiz, Adalberto Rodriguez, and the Delta operator Griz Martin. There were dozens more injured. It was a ghastly scene. Even those soldiers who had not been hurt were so blood-splattered they looked injured.

Some of the medical aides approached Sergeant Eversmann, who had commanded Chalk Four and come out with his men on the lost convoy. Eversmann was unhurt, but most of the men on his chalk had been hit. On the ride out, he had been sandwiched on the back of a Humvee with the wounded, so his uniform was caked with blood. As he stood by now, helping to unload them, two medics grabbed him and began cutting off his pants.

“Leave me alone!” he said. “I’m okay!”

They paid him no mind. Some of the men who were really wounded protested in the same way.

“Look, I’m fine. Work on them!” he shouted, pointing to men who were waiting for attention.

Eversmann was losing it. He’d been through a lot this day, and just the sight of all this blood, and all those mangled men—his men!—dismayed him. It was hard to stay even. He was venting on the nurses and medics when one, an older man, pulled him aside.

“Sergeant, what’s your name?”

“Well, Matt, listen. You need to calm down.”

“Roger.”

“We are going to take care of these guys. They’re going to be fine. You just need to calm down.”

“I am calm,” shouted Eversmann, who clearly was not. “I just want you to take care of them!”

“What these guys need right now from you is to see you being a stand-up guy. Don’t let them see you being nervous because that just makes them nervous.”

Eversmann realized he was making a fool of himself.

“Okay,” he said.

He stood helplessly for a few moments, turned, and walked slowly back to the hangar. It was hard to remove himself from the emotions of the fight. He felt himself in a kind of aftershock. Having to identify the dead was chilling. Casey Joyce was one of his men. He’d last seen Joyce when he ran off with the litter carrying Blackburn back to the convoy. He’d lost track of him after that. Now he saw his face pale and stretched with the life drained out. During the fight there hadn’t been time to react to the terror or even to recoil at what was grotesque. Now it all sank in.

It helped when Lieutenant Colonel McKnight asked him to reinforce perimeter security at the airport. There were fears that with all the fighting, Aidid might try storming the base. So Eversmann packed his brooding away and went to work. He still had six men from his chalk who were able.

The stitches on Specialist Sizemore’s elbow, where he had earlier cut off his cast to join the fight, were open and bleeding, but he waved the nurses away. He didn’t want to be sidelined again. He was haunted by images of his buddies out there in the city under siege, waiting for him. He was angry, and like many of his Ranger buddies, he wanted revenge. He thought about Stebbins, who had taken his place on the bird, and was infuriated that the company clerk was out there in his place. He had to get out there. What was holding things up? Sizemore was pacing around the waiting Humvees when a D-boy approached and asked, “Anybody here know Alphabet?”

Sizemore said he did. They walked together through the gate and past the hospital tent to the fire station. Behind it the minibunker of sandbags built by Sergeant Rymes was now covered by a white sheet. The sergeant lifted the sheet. Inside was Kowalewski’s body with the RPG still embedded in his torso.

“Is this Kowalewski?” the D-boy asked.

Sizemore nodded, or he thought he did. He was stunned. The D-boy asked him again.

“Is this Kowalewski?”

“Yes, that’s him.”

Lanky Steve Anderson tried to motivate himself for going back out. He had gone out the first time reluctantly. The events of the day so far had stirred up a mess of strong feelings, but anger predominated. Until today Anderson had been as gung ho as the rest of the guys, but now, seeing all the dead and wounded, he just felt used and stupid. His life was being put at risk and he was being thrust into a situation where he had to shoot and kill people in order to survive ... and it was hard to see why. How could some politicians in Washington take men like him and put them in such a position, guys who are young, naive, patriotic, and eager to do the right thing, and take advantage of all that for no good reason?

He listened to one of his buddies, Private Kevin Matthews, who had been in the small Humvee column when Pilla was killed and had gone back out with the first rescue convoy. Matthews was going on about this guy he had killed out on the street a few hours before, about how the man shook as five, ten, fifteen rounds slammed into him, and it sounded to Anderson like Matthews was bragging. Except, as he listened more, he saw that the young private was actually upset and was going on because he just needed to talk about what had happened. Matthews was trembling. He wanted to be reassured that he had done the right thing.

“What else could you do?” Anderson said.

Anderson had just talked to his parents the night before back in Illinois, and he’d told them everything was okay, nothing was happening, and probably nothing would. And now, this.

* * *

An effort was launched to identify men who could drive the five-ton trucks wearing NODs. The night vision goggles blocked all peripheral vision and sharply foreshortened the view. It took time to get used to driving with them. Specialist Peter Squeglia, the company armorer, had some experience riding a motorcycle wearing NODs, so one of the lieutenants asked him to take a truck.

“Sir, if you’re telling me to drive it, I’ll drive it. But I’ve never driven a truck before.”

The idea of grinding gears and stalling out in the middle of a gun-fight, where one stalled vehicle can hold up an entire column, or, worse, get left behind, terrified Squeglia. The lieutenant made a face, and walked off to find someone else. Squeglia went back to collecting weapons off the dead and wounded. Later he would clean and repair them. For now he just piled them next to his cot, a heap of blood-smeared steel. The lieutenant’s expression left Squeglia feeling deflated and guilty. Everybody was scared. Some guys were frantic to join the fight while others were looking for a way to avoid going out. Squeglia was somewhere in the middle. After what he had seen of the lost convoy, part of him felt like going out into that city was like committing suicide. It was crazy, but they had to do it. They were going to load Rangers on the back of flatbed trucks lined with sandbags that weren’t going to stop a damn thing, and roll them out into the streets where every one of these skinny Somali motherfuckers was trying to kill them, and for what? At least the Malaysians had armored vehicles. Squeglia was going to go. He was going to do his part, but he wasn’t going to do anything foolish, like decide to learn how to drive a big truck in the middle of a firefight.

When it came time to climb aboard, Squeglia picked up his pistol and his CAR-15, which he had rigged with an M-203 grenade launcher. He made sure he got in the truck after most of the others. He figured the safest spot in the flatbed, if anyplace was safe, was toward the rear where the spare tire and muffler came up. He crouched down behind that. Maybe it would stop something. The sandbags certainly wouldn’t.

Just before the convoy left the base, Specialist Chris Schleif dashed back into the hangar, rooted through Squeglia’s pile of weapons, and fished out Dominic Pilla’s M-60 and ammo. The gun and ammo can were still slick with Pilla’s blood and brain matter. Schleif ditched his own weapon and boarded the Humvee with Pilla’s.

“He didn’t get a chance to kill anybody with it,” Schleif explained to Specialist Brad Thomas, who like Schleif was heading back out into the city for the third time. “I’m going to do it for him.”

It was 9:30 P.M. when the rescue force left the airport and drove north to the New Port to link up with the Malaysians and Pakistanis. Most of the Rangers, all of the D-boys, SEALs, and air force combat controllers who hadn’t been killed or injured, and both companies of the 10th Mountain Division made up a force of nearly five hundred men. Waiting for them there were the Malaysian APCs, German-made “Condors,” rolling steel Dumpsters painted snow white with a driver in front and a porthole in the back for a gunner. Each was built to hold about six men. The Paki tanks were American-made M-48s. The armor was lined up and ready to go when the long convoy of trucks and Humvees arrived, but coordinating movement of this strange collection of vehicles—Lieutenant Colonel David called it a “gagglefuck”—was going to take more time.

He plunged right into it. With a map spread out on the hood of his Humvee, and with soldiers gathered around holding up flashlights to illuminate it, he began improvising a plan. To David’s relief, most of the Malaysian and Pakistani officers spoke English. There was little argument or discussion. The Malaysian officers at first balked at removing their infantry from the APCs, but relented when David agreed to let each vehicle retain a Malaysian driver and gunner. The various units did not have radios that were compatible, so American radios had to be placed with all the vehicles. They worked out fire control procedures, steps to prevent friendly fire incidents, call signs, the route, and a host of other critical issues.

David felt a sense of urgency, but not an overriding one. He knew there were critically injured soldiers at the first crash site for whom every minute was important. On the other hand, this convoy was it. If they screwed up, failed to reach the crash site, and got broken up or bogged down, who was going to come in and rescue them? If one or two soldiers died waiting it would be tragic, but rescuing the other ninety-seven men, and getting his own in and out safely, had to be the priority.

To the Rangers and the 10th Mountain Division soldiers eyeing the Condors for the first time, they looked like caskets on wheels. Choosing between the APCs and the sandbagged five-ton trucks was like choosing your poison: You could get riddled with bullets in the back of a flatbed or toasted by a grenade dropped into the turret or poked through the skin of an APC. The men reluctantly began to board the Condors an hour or so after they’d arrived at the New Port. There were only little peepholes in the sides, so most of the force would be riding blind. The idea of being driven out by Malaysians didn’t make them feel any better.

As the hours crept by without action, the Rangers stewed with impatience. As they saw it, they were being held back by this slow-moving, by-the-book regular army unit that didn’t fully appreciate the urgency of the situation. Further back in the column it looked like nothing was being done. Some of the 10th Mountain guys were dozing in the back of vehicles. Sleeping! Ranger Sergeant Raleigh Cash couldn’t contain himself. His buddies were dying out in the city and these guys were taking naps? Why the hell weren’t they moving? He had made peace with himself riding out with the cook convoy in that aborted effort to rescue Durant and his crew. If he was going to die today, so be it. The pull of loyalty felt stronger in him than the will to survive. He had thought it through methodically. He was wearing body armor, so if he got shot, it would probably be to the arms or legs and there were medics who would take care of him. It would hurt, but he had been hurt before. If he was shot in the head, then he would die. He wouldn’t feel any pain. His life would just be over. Just like that. The end. His friends would take care of his family for him. If he died then that was what was meant to happen.

When word came that Smith was dead, that he had bled out waiting for rescue, Cash lost it. He vented his anger and impatience on a 10th Mountain Division officer. He told the officer that before the Rangers had gotten saddled with his unit they’d had no trouble finding the fight.

“Look, we’re not holding things up,” the officer protested. “We’re ready to go just as much as you are. You have to have a little faith in your leaders.”

“It’s taking too long,” Cash said, his voice rising with anger. “My friends are dying out there! We need to get going now!”

Cash’s platoon leader came over and quieted him.

“Look, we all want to get going.”

By about 11 P.M., David had the “gagglefuck” set to go, and was feeling pretty good about it. He regarded the organizational effort as one of his major life accomplishments. The Paki tanks would lead the convoy out into the city. Behind them, each platoon would have four APCs interspersed with trucks and Humvees. The QRF’s Cobra gunships would provide air support. They’d roll out to a staging point on National Street, then one half of the force would steer south toward Durant’s Super Six Four crash site and the other would push north to Wolcott’s Super Six One, where the bulk of the task force was pinned down. They had commo links established, liaison officers dispersed throughout the convoy ... they were good to go.

Then one of the Pakistani officers ran up. His commander objected to the tanks leading the convoy. This was a problem because tanks were needed to plow through the formidable barricades (ditches, abandoned shells of cars and trucks, heaps of stone, burning tires and debris) the Somalis had erected to block most of the main roads leading out of the UN facilities. Since the New Port was home base for the Pakis, and they were the ones who had proposed the route to the holding point, a compromise was reached. The tanks would lead the way out to the K-4 circle, then fall back to the midfront of the column.

Then new problems surfaced. It was easy to see how, with enough commanders, a battle could be debated into defeat. After conferring with their superiors, the Malaysians said they had been ordered to keep their APCs on the main roads, for the same reason that Garrison had earlier judged Mogadishu the wrong place to fight with armor. It was hard for tanks and APCs to maneuver in the city’s complex web of narrow streets and alleys. The big vehicles were vulnerable when they moved slowly through streets where the enemy could creep up close or drop grenades down from rooftops and trees, or fire armor-piercing rounds at close range.

David got back out of his Humvee and huddled with the officers again. He told Captain Meyerowich, “Look, Drew, here’s the situation. I need for your company to lead us out.”

The Pakistanis agreed to lead the convoy as far as the K-4 circle, which was the borderline of Aidid’s turf. At that point Meyerowich’s company, most of them riding in the Condors, would pull through and take the lead.

It was now 11:23 P.M.

As he heard the guns of the giant convoy approaching, Captain Steele knew this was the most dangerous time of the night. The moon was high and shooting in the neighborhood around the first crash site had all but stopped. There were a few pops every once in a while. The air had cleared of smoke and gunpowder. Now there was just that musky stink of Somalia, the trace of desert dust in the air, and the slight aftertaste of the iodine pills in their canteens. Sammies would still inexplicably wander right into the middle of their perimeter up the street. The D-boys would let them walk until they reached a cross-fire zone and then drop them with a few quick shots. Every once in a while the Little Birds would rumble in and unleash a rocket and spray of minigun fire. But now the only noise that concerned Steele was the intensifying thunder of guns as the rescue column moved closer to their position. With that much shooting, with two jumpy elements of soldiers about to link up in a confusing city in darkness, the biggest threat to his pinned-down men were their rescuers.

—Romeo Six Four [Harrell], this is Juliet Six Four [Steele]. How we gonna keep from running out of the building and getting smoked?

—They’re looking for your position to be marked with an IR strobe. If there’s any doubt in your mind, flash a red desert flashlight at them.

Up the street, Captain Miller had his own concerns.

—Okay, this task force is made up of Malaysians and who, over?

—Malaysians and Americans. They have Rangers with them, over.

Miller added hopefully:

—Okay, so every vehicle should have some type of NODs so they can ID the strobe, over?

—That was the instruction sent back, over.

Then, a few minutes later, the command helicopter reassured Miller.

—Yeah, they’re moving. The lead element has night vision devices so they should be able to pick up your IR strobe, Scotty, over.

Miller was also informed that members of the Delta unit, including Major James Nixon, John Macejunas, Matt Rierson, and Chuck Esswein, would be leading the column in, which to him and the other Delta team leaders was an enormous relief.

The rescue convoy was coming from the south. By the sound of it, they were moving along the same route the Rangers and D-boys had taken that afternoon, east from the Olympic Hotel, which meant they would reach Steele’s position first. They were coming steadily but slowly, and from the sound of it they were just shooting at everything. It was about ten minutes before two in the morning. Without the NODs nobody could see that far down the street. They just had to hunker down and wait and hope the convoy did not come blasting its way down the middle of their street.

—Romeo Six Four, this is Juliet Six Four. We’re going to put IR strobes out in front of the buildings here. We plan on throwing a red Chemlite as well to mark for casualties. If we can have the APCs pull in as close to those red chems as possible that will facilitate the loading of the casualties, over.

—Roger, but you better be real careful with those red Chemlites or the bad guys will start shooting at them, over.

—Okay, but you’re saying all the guys will have NODs, right?

—They’ve got people in the lead element with NODs and they should be homing in on your IR strobes, over.

It was tense. Nearly an hour had gone by since Steele had been told the convoy would reach him in twenty minutes.

—Romeo, this is Juliet. I understand now they may have turned north. The ground reaction force turned north. Do they have an ETA at this location?

—No, they are moving slowly, taking their time. It is going to take them a while, Mike. Probably fifteen to twenty minutes based on where I think they are, over.

—Okay. We are fairly secure here. I think the Little Bird runs dampened the rebels’ spirits.

Word came from the command helicopter at about two o’clock.

—Okay, start getting ready to get out of there, but keep your heads down. Now is a bad time.

—Roger, copy. Positions are marked at this time. We are ready to move, said Steele.

—Roger, they are going to be coming in with heavy contact so be real careful.

—You better believe it, over.

“We’re about to link up,” Steele radioed Perino. “I want everybody to back up out of the courtyards, and to stay away from the doors and windows.”

So the Rangers drew back like hermit crabs into their shells, and listened. They were all terrified of the 10th Mountain Division, whom they regarded as poorly trained regular army schmoes, just a small step removed from utterly incompetent civilianhood.

Five minutes passed. Ten minutes passed. Twenty minutes passed. Then another radio call from the command bird.

—Just to give you an update. They are still at that U-turn off. They had a little bit of a direction problem amongst themselves. They should be moving now. Will let you know as soon as they start rolling northbound.

Perino called Captain Steele. “Where are they?” he asked.

Steele said, “Any minute now.”

Both men laughed.

Captain Drew Meyerowich was with the Delta operators who were leading his portion of the rescue convoy toward Steele and Miller’s position. It had been a pitched battle much of the way in. Two of the Malaysian drivers had taken a wrong turn and driven about thirty of Meyerowich’s men off in the wrong direction. They’d been ambushed and caught up in a severe firefight, and one of their men, Sergeant Cornell Houston, had been mortally wounded.

For all his careful planning, Specialist Squeglia ended up in a Humvee. The banging of gunfire was constant, most if it coming from the convoy, which stretched so far in both directions Squeglia could not see the front or rear. No one had lights on, but muzzle flashes and explosions lit up the whole line. In the reflected light he saw two dead donkeys by the side of the road, still strapped to carts. The air was filled with diesel fumes, and through the open side window of the Humvee Squeglia smelled the gunpowder from his weapon mingled with the burning tires and trash and the general pungent, rotten smell of Somalia itself. He was out in it now.

In a sudden volley of gunfire an RPG bounced off the hood. The explosion a few feet away sounded like somebody had dropped an empty Dumpster off a roof. Squeglia felt the concussion like a blow to the inside of his chest, and then smelled smoke. Everybody had ducked at the blast.

“Holy shit, what was that?” shouted Specialist David Eastabrooks, who was driving.

“Jesus,” said Sergeant Richard Lamb, who was in the front passenger seat. “I think I’ve been hit.”

“Where you hit?” Squeglia asked.

“In the head.”

“Oh, Jesus.”

One of the men in the Humvee fished out a red light flashlight, and they shined it on Lamb. He had a trickle of blood running down his face and a neat hole, a small one, right in the middle of his forehead.

“I think I’m okay,” Lamb said. “I’m still talking to you.”

He wrapped a bandage around his head. Doctors would later determine that a piece of shrapnel had lodged between the frontal lobes of his brain, missing vital tissues by fractions of an inch in either direction. He was all right. It felt like he had just banged his head. It hurt lots worse minutes later when he took a bullet to his right pinkie, which left the tip of it hanging by a piece of skin. Squeglia could see the bone of his finger jutting from the mangled flesh. Lamb just swore and stuck the fingertip back on, wrapped it with a piece of duct tape, and continued working his radio.

All the way out from the base, Specialist Dale Sizemore was shooting. He’d cut the cast off his arm to join the fight, and at last he was in it. Night vision gave him and the other men on this massive column a tremendous advantage over the Somalis. Sizemore spread out on his stomach in the back of the Humvee just looking for people to shoot. When there weren’t people he shot at windows and doorways. Most of the time he couldn’t see whether he’d hit anybody or not. The NODs severely restricted peripheral vision. He didn’t want to know, really. He didn’t want to start thinking about it.

At one point a spray of sparks flew up in his face. He turned his head to discover a fist-sized hole in the Humvee wall just inches from his head. He hadn’t felt a thing. When an RPG hit one of the trucks ahead, men came running down the street looking for space on the Humvees as tracers flew. One, Specialist Erik James, a medic, approached Sizemore’s open back hatch carrying a Kevlar blanket.

“You got room?” he asked. He looked dazed and scared.

Sizemore and Private Brian Conner moved over to make a space for him.

“Just get in here and keep that blanket over your head and you’ll be all right,” said Sizemore. He figured it was always a good idea to have a medic close by. James felt Sizemore had just saved his life.

Specialist Steve Anderson was in a Humvee near Sizemore’s in the column. He was in the back on the driver’s side with his eyes pressed to the night-vision viewfinder on his SAW. Whenever the column stopped, which was often, everyone was expected to pile out and pull security. The first time they stopped Anderson hesitated. He didn’t want to stick his legs out of the car. He had just started skydiving lessons at home before this deployment, and now, suddenly, he felt immobilized by the particular fear of being shot in the legs—he’d received a minor injury to his legs on an earlier mission. Back home he had just made his first freefall jump. It had been such a thrill. What if he got his foot shot off and could never jump again? Anderson reluctantly forced himself out on the street.

At one stop he and Sizemore stood for a long time, it seemed like hours, watching the windows of a three-story building for some sign of a shooter. They had been there for a time when Anderson noticed a dent and scrape on the roof of the Humvee right next to them. A round had ricocheted off it.

“Did you notice that before?” he asked Sizemore.

Sizemore hadn’t. It hadn’t been there when they got out either. Which meant a bullet had passed between them, missing them both by inches, without their even knowing it.

That was the way Anderson felt most of the time. Totally in the dark. He saw tracers and there were times the gunfire was so loud the night seemed ready to split at the seams, but he could never seem to tell where it was coming from, or find anyone to shoot. Sizemore, on the other hand, was going through ammunition as fast as he could load his weapon. Anderson was in awe of his friend’s confidence and selflessness, and felt both inspired and diminished by it.

Sizemore unloaded what must have been a full drum of ammo at the front of a building about fifty feet away. When he was done, Anderson could see rounds glowing and smoldering from the ground where he had been shooting, which meant he must have hit something. When rounds hit the ground or street or a building, they deflected off in other directions. But when they hit flesh, they would glow for a few moments.

“Didn’t you see them?” Sizemore asked Anderson. “There was a whole bunch of them there, shooting at us.”

Anderson hadn’t noticed. He felt completely out of his element. Minutes later he noticed another dent and scrape on the top of the Humvee, right alongside the first one. He hoped his buddy had silenced the gun that put it there.

At one stop on a wide street, when Anderson and the men in his Humvee were positioned near a two-story building, a Malaysian APC pulled up about twenty feet behind them and its machine gunner opened fire. He was shooting at the roof of the building alongside Anderson. The rounds traced red lines through the darkness, so Anderson could follow their trajectory, and they were all bouncing off the building next to him. The wall was made of irregular stone. Any one of those rounds could easily come his way. There was nothing he could do but watch. One of the rounds hit the building and then traced a wicked arc across the street like a curveball.

Private Ed Kallman was somewhere else along the giant convoy, driving again, equally amazed by the light show. Kallman’s left arm and shoulder were massively bruised from the unexploded RPG that had hit the door of his Humvee the previous afternoon and knocked him cold. He felt fine, excited again, and reasonably safe in such a massive force. There would be long periods of relative quiet, then suddenly the night would explode with light and noise. One or two shots from the dark houses or alleys on both sides of the street would trigger a violent explosion of return fire from the column. Up and down the line tracers splashed out from the long line, literally thousands of rounds in seconds, just hosing down whole blocks of homes. His NODs framed the scene in a circle and offered little depth perception. It also gave off heat just a half inch from his face that after a while started to bother his eyes. Then he would take a break and just look straight down or off to the side.

They eventually stopped and waited in the same spot for several hours. Kallman was asked to pull his Humvee back down the road, about a half block, which he did, and no sooner had he moved than an RPG exploded on what looked like the spot he had just left. He and others in his vehicle laughed. An explosion on the wall above sent a shower of debris down on them. No one was hurt. Kallman moved the Humvee forward a few feet just to make sure it wasn’t stuck.

Through the remainder of the night he just listened to the radio, trying to make sense out of the constant chatter, trying to figure out what was going on.

Ahead of them in the long column, Sergeant Jeff Struecker was shocked by all the shooting. He had heard a sergeant major from the 10th Mountain Division telling his men before they left, “This is for real. You shoot at anything,” and clearly these guys had taken him seriously.

Streucker had warned his own gunner to pick targets carefully. “When you shoot that fifty cal, that round goes on forever,” the sergeant explained. It was clear the rest of the convoy was not taking such precautions. They were throwing lead all over that part of Mogadishu.

Earlier in the day, the American helicopters had attacked the garage of Kassim Sheik Mohamed, a tall, beefy businessman with a round face, a swaggering walk, and a troublemaker’s smile. Kassim’s garage was bombed because he had, being a wealthy man, a fairly large number of armed men guarding it. At the height of the battle, any large number of well-armed Somalis in the vicinity of the fight was a target. The attack was not too misdirected. Kassim was a well-to-do member of the Habr Gidr and a supporter of Mohamed Farah Aidid.

When the bombing started, Kassim ran to a nearby hospital, figuring it was a place the Americans would not attack. He stayed there for two hours. When he returned to his garage, much of it was a smoldering ruin. An explosion had flipped a white UN Land Rover Kassim had purchased about twelve feet into the air and deposited it upright atop a stack of steel shipment boxes, as though someone had parked it up there. Some of his most valuable earthmoving equipment was destroyed. Dead was his friend and accountant, forty-two-year-old Ahmad Sheik, and one of his mechanics, thirty-two-year-old Ismael Ahmed.

It was late in the day, and the dead, according to Islamic law, needed to be buried before sundown, so Kassim and his men took the bodies to Trabuna Cemetery. On their way there, a helicopter swooped down low over them and fired rounds that hit all around the car but missed them.

The cemetery was crowded with wailing people. In the darkness, as the guns of the fight still pounded in the distance, every open space was crowded with people digging graves. Kassim and his men drove to one of the only quiet corners. They took shovels and the two bodies from the back of their cars and began carrying them. Then another American helicopter came down, frightening them, so they dropped the bodies and shovels and ran.

They hid behind a wall until the helicopter was gone, and then went back out and picked up the bodies, which were wrapped in sheets, and continued carrying them. Another helicopter zoomed in low over them. Again they dropped the bodies and shovels and ran to the wall. This time they left the bodies of Ahmad Sheik and Ismael Ahmed and drove away, agreeing to come back later in the night to bury them.

Four of Kassim’s men came back at about midnight. The guns still pounded out in the city. They carried the bodies up to a small rise and began digging. But another American helicopter appeared, hovering low and shining a floodlight down. Kassim’s men ran, leaving the bodies on the ground.

They returned at three in the morning and were finally able to bury Ahmad Sheik and Ismael Ahmed.

Half of the rescue convoy had steered south to Durant’s crash site, but had gotten stalled on the outskirts of the ghettolike village of rag and tin huts where Super Six Four had gone down. In darkness, the unmapped maze of footpaths leading into the village looked potentially deadly—it was like probing directly into the heart of the hornet’s nest. Sergeant John “Mace” Macejunas, the fearless blond Delta operator, on his third trip out into the city, slipped off a Humvee and personally led a small force on foot, wearing NODS and feeling his way into the village toward the wrecked helicopter, where hours before Mace’s buddies Randy Shughart and Gary Gordon had made their last stand.

Around the wreckage they found pools and trails of blood, torn bits of clothing, and many spent bullet shells, but no weapons and no sign of their buddies Shughart and Gordon, nor of Durant and the three other crew members. The soldiers searched the huts around the crash site, demanding information about the downed Americans through a translator, but no one offered any. Risking drawing fire, they bellowed into the night the names of all six of the missing men: “Michael Durant!” “Ray Frank!” “Bill Cleveland!” “Tommie Field!” “Randy Shughart!” “Gary Gordon!” There was only silence.

Macejunas then supervised the setting of thermite grenades on the helicopter. They stayed until Super Six Four was a ball of white flame, and then returned to the convoy.

Meyerowich’s northern half of the convoy had been delayed by a big roadblock on Hawlwadig Road up near the Olympic Hotel, which the Malaysian drivers refused to roll through. In the past, such roadblocks had been heavily mined.

Meyerowich pleaded with the liaison officer. “Tell them small arms fire is ineffective against them!” he said.

Once or twice he got out of his Humvee and walked up to the lead APC and shouted, waving his arms, urging the vehicle forward. But the Condor drivers refused to proceed. So the convoy was stalled while soldiers climbed off the vehicles and dismantled the roadblock by hand.

Meyerowich and the D-boys decided not to wait for the roadblock situation to be sorted out. They ran up and down the line of vehicles banging on the doors, shouting for all the men to pile out of the vehicles. They knew they were only blocks from the pinned-down force.

“Get out! Get out! Get out! Americans, get out!”

One of those who emerged warily was Specialist Phil Lepre. Earlier in the ride out, when the shooting got heavy and rounds were pinging off the sides of the APC, Lepre had removed a snapshot of his baby daughter he carried in his helmet and kissed it good-bye. “Babe,” he said, “I hope you have a wonderful life.” He stepped out now into the Mogadishu night, ran to a wall with two other soldiers, and pointed his M-16 down an alley. When his eyes adjusted to the darkness he saw a group of Somalis a few blocks down, edging their way toward him.

“I’ve got Somalians coming down this way!” he said.

One of the D-boys told him to shoot, so Lepre fired down toward the crowd. First he shot over their heads, but when they didn’t disperse he fired straight into them. He saw several fall. The others dragged them off the alley.

Out in the intersection, soldiers were pulling apart the barricade by hand under heavy fire. Lepre moved once or twice up the road with the rest of the men. They were spread out now on both sides of an alley a few blocks ahead of the APCs. They would move, stop, and wait, then move again, like parts of a human accordion slinking its way east. At one of the places where they stopped they began taking heavy fire from a nearby building. Men moved to take better cover and find an improved vantage to return fire.

“Hey, take my position,” he called back to twenty-three-year-old rifleman Private James Martin.

Martin hustled up and crouched behind the wall. Lepre had moved only two steps to his right when Martin was hit in the head by a round that sent him sprawling backward. Lepre saw a small hole in his forehead.

Lepre’s voice joined others shouting, “Medic! We need a medic up here!”

A medic swooped over the downed man and began loosening his clothes to help prevent shock. He worked on Martin a few minutes, then turned to Lepre and the others and said, “He’s dead.”

The medic and another soldier tried to drag Martin’s body to cover but were scattered by more gunfire. One of them ran back out and braved the gunfire, firing his weapon with one hand and dragging Martin to cover with the other. When he got close, others ran out to help, pulling the body into the alley.

Lepre was behind cover just a few feet away, gazing at Martin’s body. He felt terrible. He had asked the private to take his position, and then the man had been shot dead. All the dragging had pulled Martin’s pants down to his knees. Few of the guys wore underwear in the tropical heat. Lepre couldn’t bear seeing Martin sprawled there like that, half naked. So despite the gunfire, he stepped out into the alley and tried to pull up the dead soldier’s pants, to give the man some dignity. Two bullets struck the pavement near where he stooped, and Lepre scrambled reluctantly back to cover.

“Sorry, man,” he said.

The command bird continued to coax the force linkup at the first crash site.

—They are leading the mounted troops by dismounted troops. The dismounted troops and the mounted troops are holding south of the Olympic Hotel....

Then, talking to the convoy, as they approached the left turn:

—Thirty meters south of the friendlies. They are one minor block to the north of you right now. If your lead APC continues moving he can make the next left and go one block, over.

Steele heard the vehicles making the turn. Out the door his men saw the dim outline of soldiers. Steele and his men called out, “Ranger! Ranger!”

“Tenth Mountain Division,” came the response.

—Roger, we’ve got a linkup with the Kilo and Juliet element, over.

Steele stuck his head out the door.

“This is Captain Steele. I’m the Ranger commander.”

“Roger, sir, we’re from the 10th Mountain Division,” a soldier answered.

“Where’s your commander?” Steele asked.

It took hours to pry Elvis out of the wreck. It was ugly work. The rescue column had brought along a quickie saw to cut the chopper’s metal frame away from his body, but the cockpit was lined with a layer of Kevlar that just ate up the saw blade. Next they tried to pull the Black Hawk apart, attaching chains to the front and back ends of it. A few of the Rangers, watching this from a distance, thought the D-boys were using the vehicles to tear the pilot’s body out of the wreckage. Some turned away in disgust.

The dead were placed on top of the APCs, and the wounded were loaded inside them. Goodale hobbled painfully out to the one that had stopped before their courtyard, and was helped through the doors. He rolled to his side.

“We need you to sit,” he was told.

“Look, I got shot in the ass. It hurts to sit.”

“Then lean or something.”

At Miller’s courtyard they carried Carlos Rodriguez out first in his inflated rubber pants. Then they moved the other wounded. Stebbins was feeling pretty good. Out the window he could see 10th Mountain Division guys lounging up and down the street, a lot of them. He protested when they came back for him with a stretcher.

“I’m okay,” he told them. “I can stand on one leg. Just help me over to the vehicle. I’ve still got my weapon.”

He hopped on his good foot and was helped up into the armored car.

Wilkinson climbed into the back of the same vehicle. They all expected to be moving shortly, but instead they sat. The closed steel container was like a sauna and it reeked of sweat and urine and blood. What a nightmare this mission had become. Every time they thought it was over, that they’d made it, something worse happened. The injured in the vehicles couldn’t see what was going on outside, and they didn’t understand the delay. They’d all figured the convoy would arrive and they’d scoot home. It was only a five-minute drive to the airport. It was now after three o’clock in the morning. The sun would be coming back up soon. Bullets occasionally pinged off the walls. What would happen if an RPG hit them?

There was a brief mutiny under way in Goodale’s Condor.

“Shouldn’t we be moving?” Goodale asked.

“Yeah, I would think so,” said one of the other men crammed in with him.

Goodale was closest to the front, so he leaned up to the Malay driver.

“Hey, man, let’s go,” he said.

“No. No,” the driver protested. “We stay.”

“God damnit, we’re not staying! Let’s get the fuck out of here!”

“No. No. We stay.”

“No, you don’t understand this. We’re getting shot at. We’re gonna get fucked up in this thing!”

The commanders were also growing impatient.

—Scotty [Miller], give me an update please, asked Lieutenant Colonel Harrell.

Other than brief stops back at the base to refuel, Harrell and air commander Tom Matthews were up over the city in their C2 Black Hawk throughout the night.

Miller responded:

—Roger. They’re trying to pull it apart. So far no luck.

—Roger. You’ve only got about an hour’s worth of darkness left.

There were more than three hundred Americans now in and around these two blocks of Mogadishu, the vanguard of a convoy that stretched a half mile back toward National Street, which created a sense of security among the recently arrived 10th Mountain troops that was not shared by the Rangers or the D-boys who had been fighting all night. The weary assault force watched with amazement as the regular army guys leaned against walls and lit cigarettes and chatted out on the same street where they had just experienced blizzards of enemy fire. To Howe, the Delta team leader who had been so disappointed by the Rangers, these men seemed completely out of place. The wait for them to extract Elvis’s body was beginning to worry everybody.

When an explosion rocked Stebbins’s APC, men shouted with anger inside. “Get us the fuck out of here!” one screamed. Rodriguez was moaning. Stebbins and Heard were taking turns holding up the machine gunner’s IV bag. They were wedged into the small space like pieces of a puzzle. Soon after the explosion the carrier’s big metal door swung open and a soldier from the 10th who had been hit in the elbow was lifted in on a litter. He screamed with pain as he hit the floor.

“I can’t believe it!” he shouted.

The Malaysian driver kept turning back, trying to keep things calm. “Any minute now, hospital,” he would say.

After patching up the new arrival, Wilkinson sat back against the inner wall and saw through a peephole that darkness had begun to drain from the eastern sky. The volume of fire was starting to pick up. There were more pings off the side of the carrier.

The wounded who had been so eager to board the big armored vehicles now prayed to get off. They felt like targets in a turkey shoot. Goodale had only a small peephole to see outside. It was so warm he began to feel woozy. He removed his helmet and loosened his body armor, but it didn’t help much. They all sat in the small dark space just staring silently at each other, waiting.

“You know what we should do,” suggested one of the wounded D-boys. “We should kind of crack one of these doors a little bit so that when the RPG comes in here, we’ll all have someplace to explode out of.”

About an hour before sunrise, there was an update from the C2 bird to the JOC:

—They are essentially pulling the aircraft instrument panel apart around the body. Still do not have any idea when they will be done.

—Okay, are they going to be able to get the body out of there? Garrison demanded. I need an honest, no shit, for-real assessment from the platoon leader or the senior man present. Over.

Miller answered:

—Roger. Understand we are looking at twenty more minutes before we can get the body out.

Garrison said:

—Roger. I know they are doing the best they can. We will stay the course until they are finished. Over.

As the sky to the east brightened, Sergeant Yurek was startled by the carnage back in the room where they had spent the night. Sunlight illuminated the pools and smears of blood everywhere. As he poked his head out the courtyard door he could see Somali bodies scattered up and down the road in the distance. One of the bodies, a young Somali man, appeared to have been run over several times by one of the vehicles being used to pull apart the helicopter. Yurek was especially saddened to see, at a corner of Marehan Road, the carcass of the donkey he had watched miraculously crossing the street back and forth through all the gunfire the day before. It was still hooked to its cart.

Howe noticed among the bodies stacked on top of the APCs the soles of two small assault boots. There was only one guy in the unit with boots that small. It had to be Earl Fillmore.

Everybody knew the respite here was about to end. Daylight would bring Sammy back outdoors. Captain Steele stood outside the courtyard door checking his watch compulsively. He must have looked at it hundreds of times. He couldn’t believe they weren’t moving yet. The horizon was starting to get pink. Placing three hundred men at jeopardy in order to retrieve the body of one man was a noble gesture, but hardly a sensible one. Finally, at sunup, the grim work was done.

—Adam Six Four [Garrison], this is Romeo Six Four [Harrell]. They are starting to move at this time, over. ... Placing the charges and getting ready to move.

Then came the next shock for the Rangers and D-boys who had been fighting now for fourteen hours. There wasn’t enough room on the vehicles for them. After the 10th Mountain Division soldiers reboarded, the anxious Malaysian drivers just took off, leaving the rest of the force behind. They were going to have to run right back out through the same streets they’d fought through on their way in.

It was 5:45 A.M., Monday, October 4. The sun was now over the rooftops.

So they ran. The original idea was for them to run with the vehicles in order to have some cover, but the Malay drivers had sped out.

Still hauling the radio on his back, Steele ran alongside Perino. Eight Rangers were strung out behind them. Behind them were the rest of Delta Force, the CSAR team, everybody. It happened so fast, men at the far end of the line were surprised when they made the right turn at the top of the hill to find that the others had moved out already.

Yurek ran with Jamie Smith’s gear. Nobody had wanted to touch it. It was like acknowledging he was gone. The whole force ran the same route the main force had used coming in, stopping at each intersection to spray covering fire as they one by one sprinted across. As soon as they began moving the shooting resumed, almost as bad as it had been the afternoon before. The Rangers shot at every window and door, and down every cross street. Steele felt like his legs were lead weights and that he was moving at a fraction of his normal speed, yet he was running as fast as he could.

When they got up to their original blocking position there was withering fire across the wide intersection before the Olympic Hotel. Sergeant Randy Ramaglia saw the rounds hitting the sides of the armored vehicles blocks ahead. We’re going to run through that? It was the same shit as yesterday. He had made it up to the intersection when he felt a sharp blow to his shoulder, like someone had hit him with a sledgehammer. It didn’t knock him down. He just froze. It took a few seconds for him to regain his senses. At first he thought something had fallen on him. He looked up.

“Sergeant, you’ve been shot!” shouted Specialist Collett, who had been running beside him.

Ramaglia turned to him. Collett’s eyes were wide.

“I know it,” he said.

He took several deep breaths and tried to move his arm. He could move it. He felt no pain.

The round had hit Ramaglia’s left back, taking out a golf ball–sized scoop of it. The round had then skimmed off his shoulder blade and nicked Collett’s sleeve, tearing off the American flag he had stitched there.

“Are you okay?” a Delta medic shouted at him from across the street.

“Yeah,” said Ramaglia, and he started running again. He was furious. The whole scene seemed surreal to him. He couldn’t believe some pissant fucking Sammy had shot him, Sergeant Randal J. Ramaglia of the U.S. Army Rangers. He was going to get out of that city alive or take half of it with him. He shot at anyone or anything he saw. He was running, bleeding, swearing, and shooting. Windows, doorways, alleyways ... especially people. They were all going down. It was a free-for-all now. All semblance of an ordered retreat was gone. Everybody was just scrambling.

* * *

Sergeant Nelson, still stone deaf, ran alongside Private Neathery, who had been shot in the right arm the afternoon before. Nelson had his M-60 and carried Neathery’s M-16 slung across his back. They ran as hard as they could and Nelson shot at everything he saw. He had never felt so frightened, not even at the height of things the previous day. He and Neathery were toward the rear and were terrified that in this wild footrace they would be left behind or picked off. Neathery was having a hard time running, which slowed them down. When they caught up to a group providing covering fire at the wide intersection they were supposed to stop and take their turn, cover for that group to advance, but instead they just ran straight through.

Howe kicked in a door of a house on the street and the team piled in to reload and catch their breath. Captain Miller stepped in, breathing hard, and told them to keep moving. Howe went around the room double-checking everybody’s status and ammo and then they pushed back out to the street. He was shooting his CAR-15 and his shotgun. Up ahead the APC gunners were shooting up everything.

Private Floyd ran with his torn pants flapping, all but naked from the waist down, feeling especially vulnerable and ridiculous. Alongside him, Doc Strous disappeared suddenly in a loud flash and explosion that knocked Floyd down. When he regained his senses and looked over for Strous, all he saw was a thinning ball of smoke. No Doc.

Sergeant Watson grabbed Floyd’s shoulder. The private’s helmet was cockeyed and his eyes felt that way.

“Where the hell is Strous?”

“He blew up, Sergeant.”

“He blew up? What the hell do you mean he blew up?”

“He blew up.”

Floyd pointed to where the medic had been running. Strous stepped from a tangle of weeds, brushing himself off, his helmet askew. He looked down at Floyd and just took off running. A round had hit a flashbang grenade on Strous’s vest and exploded, knocking him off his feet and into the weeds. He was unhurt.

“Move out, Floyd,” Watson screamed.

They all kept running, running and shooting through the brightening dawn, through the crackle of gunfire, the spray of loose mortar off a wall where a round hit, the sudden gust of hot wind from a blast that sometimes knocked them down and sucked the air out of their lungs, the sound of the helicopters rumbling overhead, and the crisp rasp of their guns like the tearing of heavy cloth. They ran through the oily smell of the city and of their own bodies, the taste of dust in their dry mouths, with the crisp brown bloodstains on their fatigues and the fresh memory of friends dead or unspeakably mangled, with the whole nightmare now grown unbearably long, with disbelief that the mighty and terrible army of the United States of America had plunged them into this mess and stranded them there and now left them to run through the same deadly gauntlet to get out. How could this happen?

Ramaglia ran on some desperate last reserve of adrenaline. He ran and shot and swore until he began to smell his own blood and feel dizzy. For the first time he felt some stabs of pain. He kept running. As he approached the intersection of Hawlwadig Road and National Street, about five blocks south of the Olympic Hotel, he saw a tank and the line of APCs and Humvees and a mass of men in desert battle dress. He ran until he collapsed, with joy.

At Mogadishu’s Volunteer Hospital, surgeon Abdi Mohamed Elmi was covered with blood and exhausted. His wounded and dead countrymen had started coming early the evening before. Just a trickle at first, despite the great volume of shooting going on. Vehicles couldn’t move on the streets so the patients were carried in or rolled in on handcarts. There were burning roadblocks throughout the city and the American helicopters were buzzing low and shooting and most people were afraid to venture out.

Before the fight began, the Volunteer Hospital was virtually empty. It was located down near the Americans’ base by the airport. After the trouble had started with the Americans most Somalis were afraid to come there. By the end of this day, Monday, October 4, all five hundred beds in the hospital would be full. One hundred more wounded would be lined in the hallways. And Volunteer wasn’t the biggest hospital in the city. The numbers were even greater at Digfer. Most of those with gut wounds would die. The delay in getting them to the hospital—many more would come today than came yesterday—allowed infections to set in that could no longer be successfully treated with what antibiotics the hospital could spare.

The three-bed operating theater at Volunteer had been full and busy all through the night. Elmi was part of a team of seven surgeons who worked straight through without a break. He had assisted in eighteen major surgeries by sunrise, and the hallways outside were rapidly filling with more, dozens, hundreds more. It was a tidal wave of gore.

He finally walked out of the operating room at eight in the morning, and sat down to rest. The hospital was filled with the chilling screams and moans of broken people, dismembered, bleeding, dying in horrible pain. Doctors and nurses ran from bed to bed, trying to keep up. Elmi sat on a bench smoking a cigarette quietly. A French woman who saw him sitting down approached him angrily.

“Why don’t you help these people?” she shouted at him.

“I can’t,” he said.

She stormed away. He sat until his cigarette was finished. Then he stood and went back to work. He would not sleep for another twenty-four hours.

Abdi Karim Mohamud left his friend’s house in the morning after the Americans had gone. The day before he’d been sent home early from his job at the U.S. embassy compound and had run to witness the fighting around the Bakara Market. It was so fierce he’d spent a long sleepless night on the floor at his friend’s house, listening to the gunfire and watching the explosions light up the sky.

The shooting flared up again violently after sunrise as the Rangers fought their way out. Then it stopped.

He ventured out an hour or so later. He saw a woman dead in the middle of the street. She had been hit by bullets from a helicopter. You could tell because the helicopter guns tore people apart. Her stomach and insides were spilled outside her body on the street. He saw three children, tiny ones, stiff and gray with death. There was an old man facedown in the street, his blood in a wide pool dried around him, and beside him was his donkey, also dead. Abdi counted the bullets in the old man. There were three, two in the torso and one in the leg.

Bashir Haji Yusuf, the lawyer, heard the big fight resume at dawn. He had managed to fall asleep for a few hours and it awakened him. When that shooting stopped he told his wife he was going to see. He took his camera with him. He wanted to make a record of what had happened.

He saw dead donkeys on the road, and severe damage to the buildings around the Olympic Hotel and further east. There were bloodstains all over the buildings and streets, as if some great thrashing beast had been through, but most of the dead had been carried off. He snapped pictures as he walked down one of the streets where the soldiers had run, and he saw the husk of the first Black Hawk that had crashed, still smoldering from the fire the Rangers had set on it. As he walked he saw the charred remains of Humvees, one that was still burning, and several Malaysian APCs.

Then Bashir heard a great stir of excitement, people chanting and cheering and shouting. He ran to see.

They had a dead American soldier draped over a wheelbarrow. He was stripped to black undershorts and lay draped backward with his hands dragging on the dirt. The body was caked with dry blood and the man’s face looked peaceful, distant. There were bullet holes in his chest and arm. Ropes were tied around his body, and it was half wrapped in a sheet of corrugated tin. The crowd grew larger as the wheelbarrow was pushed through the street. People spat and poked and kicked at the body.

“Why did you come here?” screamed one woman.

Bashir followed, appalled. This is terrible. Islam called for reverential treatment and immediate burial of the dead, not this grotesque display. Bashir wanted to stop them, but the crowd was wild. These were wild people, ghetto people, and they were celebrating. To step forward and ask, “What are you doing?” to try to shame them, as Bashir wanted to do, would risk having them turn on him. He snapped several pictures and followed the mob. So many people had been killed and hurt the night before. The streets filled with even angrier, more vicious people. A festival of blood.

Hassan Adan Hassan was in a crowd that was dragging another dead American. Hassan sometimes worked as a translator for American and British journalists, and wanted to be a journalist himself. He followed the crowd down to the K-4 circle, where the numbers swelled to a sizable mob. They were dragging the body on the street when an outnumbered and outgunned squad of Saudi Arabian soldiers drove up on vehicles. Even though they were with the UN, the Saudis were not considered enemies of the Somalis, and even on this day their vehicles were not attacked. What the Saudis saw made them angry.

“What are you doing?” one of the soldiers asked.

“We have Animal Howe,” answered an armed young Somali man, one of the ringleaders.

“This is an American soldier,” said another.

“If he is dead, why are you doing this? Aren’t you a human being?” the Saudi soldier asked the ringleader, insulting him.

One of the Somalis pointed his gun at the Saudi soldier. “We will kill you, too,” the gunman said.

People in the back of the crowd shouted at the Saudis, “Leave it. Leave it alone! These people are angry. They might kill you.”

“But why do you do this?” the Saudi persisted. “You can fight and they can fight, but this man is dead. Why do you drag him?”

More guns were pointed at the Saudis. The disgusted soldiers drove off.

Abdi Karim was with the crowd dragging the dead American. He followed them until he grew afraid that an American helicopter would come down and shoot at them all. Then he drifted away from the mob and went home. His parents were greatly relieved to see him alive.

The Malaysians led everyone to a soccer stadium at the north end of the city, a Pakistani base of operations. The scene there was surreal. The exhausted Rangers drove in through the big gate out front, passed through the concrete shadows under the stands, like going to a football or baseball game at home, and then burst out blinking into a wide sunlit arena, rows of benches reaching up all around to the sky. In the lower stands lounged rows and rows of 10th Mountain Division soldiers, smoking, talking, eating, laughing, while on the field doctors were tending the scores of wounded.

Dr. Marsh had flown to the stadium with two other docs to supervise the emergency care. Unlike the first load of casualties that had come in with the lost convoy, these had mostly been patched up by medics in the field. Still, Dr. Bruce Adams found it a hellish scene. He was used to treating one or maybe two injuries at a time. Here was a soccer pitch covered with bleeding, broken bodies. The wounded Super Six One crew chief Ray Dowdy walked up to Adams and held up his hand, which was missing the top digits of two fingers. The doctor just put his arm around him and said, “I’m sorry.”

For the Rangers, even the ride from the rendezvous point on National Street to the stadium had been traumatic. There was still a lot of shooting going on and barely enough room on the Humvees to take all the men who had run out, so guys were piled in two and three layers deep. Private Jeff Young, who had badly twisted his ankle on the run out, was picked up by one of the D-boys, who dropped him into the backseat of a Humvee and then unceremoniously sat on his lap. Private George Siegler had hopefully sprinted up to the hatch of an APC just as a voice yelled from inside, “We can only take one more!” Lieutenant Perino already had one leg in the hatch. Out of the corner of his eye Perino saw the younger man’s desperation. He withdrew his leg from the hatch and said, cloaking his kindness with officerly impatience, “Come on, Private, come on.” It would have been easy for the lieutenant to say he hadn’t seen him. Siegler was so moved by the gesture he decided then and there to reenlist.

Nelson found himself in a Humvee that had four full cans of 60 ammo, so he worked his pig the whole way out of the city, shooting at anybody he saw. If they were on the street and he saw them he shot at them. He was close to coming out of this mess alive, and he was doing everything he could to make sure he did.

On his way out, Dan Schilling, the air force combat controller who had ridden out the bloody wandering of the lost convoy and then come back out into the city with the rescue convoy, saw an old Somali man with a white beard walking up the road with a small boy in his arms. The boy appeared to be about five years old and was bloody and looked dead. The old man walked seemingly oblivious to the firefight going on around him. He turned a corner north and disappeared up the street.

For Steele, the worst moment in the whole fight had come as they pulled away from National Street. The captain was looking down the line of APCs, watching men climb on board, and he saw Perino down at the end of the line step back and let Siegler in the hatch, and then, boom! the vehicles took off. There were still guys back there, Perino and others! He beat frantically on the shoulders of the APC driver, screaming at him, “I’ve got guys still out there!” but the Malay driver had a tanker helmet on and acted like he didn’t hear Steele and just kept on driving. The captain got on the command net. Reception was so bad inside the carrier that he could barely hear a response, but he broadcast his alarm in disjointed phrases:

—We got left back on National. ... The Paki vehicles were gonna follow us home, the foot soldier. ... But we loaded up but we had probably fifteen or twenty still had to walk. They took off and left us. We need to get somebody back down there to pick them up.

—Roger. I understand, Harrell had answered. I thought everybody was loaded. I got about three calls. They were telling me they were loaded. Where are they on National?

—Romeo, this is Juliet. I’m sending this blind. I need those soldiers picked up on National ASAP!

In fact, Perino and the others had been picked up, but not without some trouble. The lieutenant and about six other men, Rangers and some D-boys, were the last ones on the street when what looked like the last of the vehicles approached. The exhausted soldiers shouted and waved but the Malaysian driver paid them no mind until one of the D-boys stepped out and leveled a CAR-15 at him. He stopped. They just piled in on top of the other men already jammed inside.

Steele didn’t find out until he got to the stadium. Some of the Humvees had gone straight back to the hangar, so it took a last stressful half hour to account for them. Finally someone back at the JOC read him a list of all the Rangers who had come back there. It was only then that the captain took a long look around him and the magnitude of what had happened began to register.

* * *

Lieutenant Colonel Matthews, who had been aloft in the command bird with Harrell for the last fifteen hours except for short refueling breaks, stepped out of the bird and stretched his legs. He’d become so used to the sound of the rotors by now that he perceived the scene before him in silence. The wounded were on litters filling half of the field, tethered to IV bags, bandaged and bloody. Doctors and nurses huddled over the worst of them, working furiously. He saw Captain Steele sitting by himself on the sandbags of a mortar pit with his head in his hands. Behind Steele were rows of the dead, neatly arrayed in zippered body bags. Out on the field, moving from wounded man to wounded man, was a Pakistani soldier holding a tray with glasses of fresh water. The man had a white towel draped over his arm.

Those who were not wounded walked among the litters on the soccer pitch with tears in their eyes or looking drained and emotionless—thousand-mile stares. Helicopters, Vietnam-era Hueys emblazoned with the Red Cross, were coming and going, shuttling those who were ready back to the hospital by the hangar. Private Ed Kallman, who earlier had thrilled at the chance to be in combat, now watched as a medic efficiently sorted the litters as they came off vehicles like a foreman on a warehouse loading dock—“What have you got there? Okay. Dead in that group there. Live in this group here.” Sergeant Watson wandered slowly through the wounded, taking account. Once the medics and doctors had cut off their bloody, dirty clothes and exposed the wounds, the full horror of it was much greater. There were guys with gaping bruised holes in their bodies, limbs mangled, poor Carlos Rodriguez with a bullet through his scrotum, Goodale and Gould with their bare wounded asses up in the air, Stebbins riddled with shrapnel, Lechner with his leg mashed, Ramaglia, Phipps, Boorn, Neathery ... the list went on.

Specialist Anderson, despite his deep misgivings about coming out with the main convoy, had come through it unhurt. He was thrilled to find his skydiving buddy Sergeant Keni Thomas still alive and unhurt, but other than that he just felt emotionally spent. He recoiled at the ugliness of the scene, the wounds, the bodies. When the APC with Super Six One copilot Bull Briley’s body on top arrived, Anderson had to turn away. The body was discolored. It looked yellow-orange, and through the deep gash in his head he could see brain matter spilled down the side of the carrier. When the medics came over looking for help getting the body down, Anderson just ducked away. He couldn’t deal with it.

Goodale was laid out in the middle of the big stadium with his pants cut off looking up at a clear blue sky. A medic leaned over him dropping ash from his cigarette as he tried to stick an IV needle in his arm. And even though it was sunny and probably close to ninety degrees again, Goodale’s teeth chattered. He was chilled to the bone. One of the doctors gave him some hot tea.

That’s how Sergeant Cash found him. Cash had just arrived on the tail end of the rescue convoy and was wandering wild-eyed across the field looking for his friends. At first sight he thought Goodale, who was pale and shivering violently, was a goner.

“Are you all right?” Cash asked.

“I’ll be all right. I’m just cold.”

Cash helped flag a nurse, who covered Goodale with a blanket and tucked it in around him. Then they compared notes. Goodale told Cash about Smith, and went down the list of wounded. Cash told Goodale what he had seen back at the hangar when the lost convoy came in. He told him about Ruiz and Cavaco and Joyce and Kowalewski.

“Mac’s hit,” said Cash, referring to Sergeant Jeff McLaughlin. “I don’t know where Carlson is. I heard he’s dead.”