With Gemini 4 buttoned up tight, McDivitt took a good look at his partner. White’s faceplate, he saw, was fogged with sweat. The sight convinced him that they both needed a rest. In Houston, a big sigh of relief had echoed through Mission Control when the hatch snapped shut. Three teams were keeping a round-the-clock watch on the spacecraft. White Team leader Gene Kranz summed up the pride everyone was feeling. “This was one of those magical moments,” he wrote. “Pride, patriotism, and American know-how triumphed that day. I was happy and proud, almost giddy, but then . . . it was time to get back to business.”1

In the media center, reporters hurried to file their stories. A few spiced up their efforts by calling the ship Little Eva—a tribute to the nation’s first EVA. Until this time, each capsule had been given its own flight name. John Glenn made the first orbital flight in Friendship 7. Gemini 3 had been christened the Molly Brown. McDivitt and White had wanted to call their ship American Eagle, but NASA refused. Naming the capsules, officials said, detracted from the serious nature of the missions.2

Image Credit: NASA

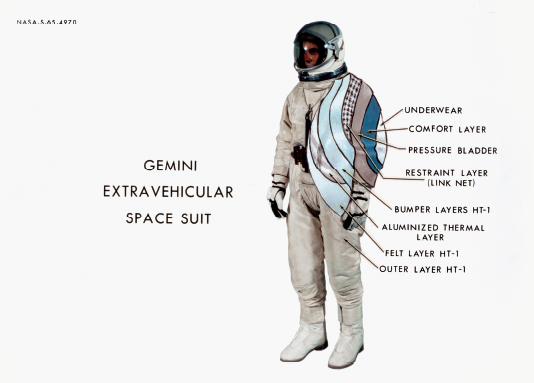

Although both astronauts wore G4C space suits, White’s had an extra EVA layer to protect him during his spacewalk. However, once he returned to the spacecraft’s cabin, the extra insulation kept him too warm. This diagram shows the suit’s different layers.

Life in Orbit

After a short rest, the Gemini 4 astronauts settled into a regular routine. Both men wore their G4C space suits throughout the mission. The suits protected the astronauts from radiation from the sun, as well as sudden changes in cabin temperature and pressure. With the cabin temperature holding at 75°F (24°C), McDivitt said he felt fine. White’s suit, with its extra EVA layer, kept him a bit too warm. Six hours into the flight, both men complained of a strong odor that made their eyes burn. Mission Control guessed that the climate-control system was releasing the fumes. Later, the astronauts grumbled about their radio headsets. The lightweight headsets worked well enough—except when they floated off their heads at odd moments.3

On shorter flights, astronauts had shown some loss of muscle strength. Worried that the loss might be greater on a longer mission, doctors added a workout program for Gemini 4. The exerciser was a bungee cord with a handle at one end and a foot strap at the other. Nothing else would have worked in the tiny cabin. When the astronauts exercised, data flowed back to Houston from sensors embedded in their suits. The sensors kept track of pulse rates, blood pressure, and other vital signs. By the two-day mark, both men told CapCom they had lost interest in their workouts. They were more faithful in doing the stretching routines that relieved cramped leg and back muscles.4

For this first four-day flight, sleep and meal breaks had been added to the schedule. The plan was for one man to sleep while the other carried on his duties. But when put to the test, the sleep schedule failed on all counts. Each time the on-duty astronaut moved, he disturbed the sleeper. To make matters worse, the cabin was anything but quiet. The radio crackled, thrusters fired with a whoosh, and power circuits hummed and buzzed. On later Gemini missions, the astronauts slept and ate at the same time.5

Image Credit: NASA

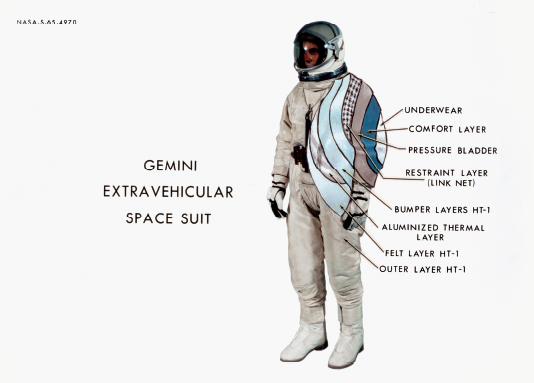

In this photo, packages of beef and gravy (top left) are ready to be “cooked.” To prepare their meals aboard the spacecraft, the astronauts squirted water into the dried food packets using the water gun (top right).

The flight plan also called for four meals a day. “Cooking” mostly consisted of squirting water into packets of dried foods. To eat pot roast or chicken, the men squeezed the mushy mix into their mouths through a feed tube. The tastiest dish, they agreed, was smoked bacon. White, who loved big, juicy steaks, had to be content with this menu on the third day:

- Breakfastsugar-toasted flakes, sausage patties, cinnamon toast, orange-grapefruit juice.

- Lunchbeef and gravy, cheese sandwich, apricot pudding, orange juice.

- Dinnerbeef pot roast, green peas, toasted bread cubes, pineapple cubes, tea.

- Late dinnerChicken bites, toast, applesauce, brownies, grapefruit juice.6

To prevent dehydration, doctors asked the men to drink at least two quarts (1.9 L) of fluids a day. At one point, the men’s wives joined the doctors in urging their husbands to “drink up.” Speaking from Mission Control, Pat White told Ed, “Have a drink of water.”

“Roger,” the dutiful husband replied. “Stand by for a drink of water.”

Moments later, a second voice crackled through the headphones. “Hey, have a drink of water, both of you,” Pat McDivitt ordered.7

Image Credit: NASA Johnson Space Center

Patricia McDivitt (left) and Patricia White speak to their husbands during the Gemini 4 mission as the astronauts pass over the United States. Both wives ordered their husbands to drink more water. Doctors had warned the astronauts that they needed to drink at least two quarts of water a day to stay hydrated.

The two Pats did not know that the men had not bothered to shave or brush their teeth. If they had known, they might have added a few commands about personal hygiene.

Experiments and Observations

As the hours passed, the astronauts met another hazard of life in zero gravity. Each time a juice packet leaked, the droplets floated around the cabin. When they dug into a storage locker, the contents were sure to drift out. That meant catching each object (a gauge or a wrench, perhaps) and stowing it away again. If someone left a locker open, everything floated out all over again.

As the hours ticked by, McDivitt and White carried out a series of experiments. A dosimeter checked on radiation in the capsule. A magnetometer measured changes in the earth’s magnetic fields. Another assignment called on their camera skills. As they passed over the United States, the astronauts snapped pictures of the landscape below. One set of photos gave weather experts a topside look at a major storm system. Turning their gaze skyward, the pilots used a sextant to check their position. A sextant measures the angular distance between two points in space, such as the sun and the horizon. The test confirmed that future crews could one day use sextants to help find their way to the moon and back.8

Around and above them, the Gemini twins glimpsed satellites and burned-out rockets. Looking down, they spotted Egypt’s Nile River and the cities of Cairo and Alexandria. White said he could make out roads, streetlights, airfields, and smoke from factory chimneys. These sightings surprised the experts. Most had doubted that astronauts could see such small details from space.9

Image Credit: NASA

This photo shows the Nile River Delta, Egypt, the Suez Canal, Israel, Jordan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq from the Gemini 4 spacecraft. White and McDivitt reported that they could see details, such as cities, rivers, roads, and airfields, as they orbited the Earth.

“Like a Falling Rock”

As Gemini 4 logged a record fourth day in space, CapCom ordered the crew to prepare for reentry. By now, McDivitt had shown that he could maneuver Gemini 4 with great precision. All seemed ready for him to fly the spacecraft to a gliding reentry. To do so, however, he needed the help of the ship’s onboard computer. This was a first for an American spacecraft, and skeptics had warned that it might not work. The computer did work just fine—until day four. At that crucial moment, no matter how the men jiggled the switch, the computer did not respond. The failure left McDivitt with no choice but to make a plunging, Mercury-type reentry. To the command pilot, that was like riding a falling rock back to Earth. “I just think it’s old fashioned,” he muttered.10

During orbit sixty-two, the astronauts fired Gemini’s retro-rockets. After plunging to an altitude of 16.8 miles (27 kilometers), McDivitt slowed the roll rate and deployed the drogue parachute. A drogue parachute is designed to quickly slow objects as they fall.

Gemini 4 twisted and turned until the main chute popped open and further slowed the descent. Moments later, the ship splashed into the ocean. The impact slammed the two men around a bit, but they were down safely.

Image Credit: NASA

A navy frogman team keeps the Gemini 4 spacecraft afloat as it waits to be hauled aboard the USS Wasp. The astronauts boarded a chopper for the ride back to the Wasp after leaving the spacecraft.

Due to the computer breakdown, the astronauts landed 50 miles (80 kilometers) short of their target. Helicopters from the USS Wasp, however, reached them moments after splashdown. As Gemini bobbed in the waves, divers attached a flotation collar to keep it from sinking. McDivitt and White popped the hatch, jumped out, and climbed into a chopper. When they landed on the Wasp, the sailors rolled out a red carpet. The warm welcome, White said later, left him feeling “red, white, and blue all over.”11