Ed White (left) and Jim McDivitt listen to President Lyndon B. Johnson as he congratulates them after their successful mission. Johnson said that what the two men had done “will never be forgotten.”

Soon after White and McDivitt reached the Wasp, the captain called them to the phone. President Lyndon Johnson was on the line. “What you have done will never be forgotten,” Johnson told them. “[You] two outstanding men have taken a long stride forward in mankind’s progress.”1 To the American people, that “long stride forward” meant that the United States had jumped into the lead in the space race with the Soviet Union.

Before the astronauts left the Wasp, doctors ran them through a series of tests. The effects of weightlessness had been the doctors’ greatest worry. A few had predicted that the pilots would faint—or even die—when they returned to Earth. To their surprise, neither astronaut showed signs of distress. Except for feeling tired and hungry, they were in good shape. White even danced a little jig when he stepped onto the red carpet. The tests did show that both men had lost some bone mass, but that was expected. Doctors also noted the fact that they had lost weight and their blood pressure had dropped.2

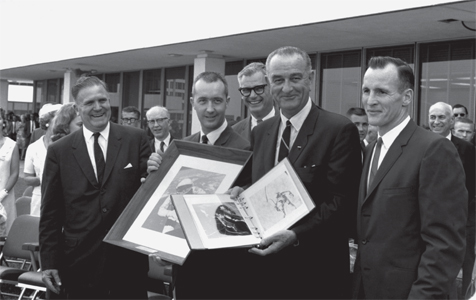

Ed White (left) and Jim McDivitt listen to President Lyndon B. Johnson as he congratulates them after their successful mission. Johnson said that what the two men had done “will never be forgotten.”

Four days in space left the astronauts badly in need of a shower. As White said with a smile, “I thought I smelled fine. It was all those people on the carrier that smelled strange.”3 While the tests dragged on, the astronauts found it hard to contain their high spirits. At one point, while lying on an X-ray table, McDivitt cut loose with a loud “Yahoo!”4 On the second day, White joined in a tug-of-war between the ship’s sailors and marines. His team lost, but his display of strength and endurance pleased the doctors.5

With medical worries laid to rest, NASA drew up its balance sheet. Gemini 4, the record showed, met all but two of its objectives. Early in the flight, lack of fuel cut short the attempt to rendezvous with the booster. Four days later, the computer glitch kept McDivitt from flying the ship to a gliding reentry. As a joke, reporters gave the team an abacus (an ancient, handheld counting device). Use it, they said, if the computer conks out on future flights.6

For the most part, both men and machine performed flawlessly. At Mission Control, Gemini 4’s support teams proved they were ready to handle longer flights. While in orbit, the astronauts devoted twenty-two hours to eleven important experiments.7 The high point, clearly, was White’s spacewalk. His trouble-free EVA proved that astronauts could do useful work in space. The next big challenge, NASA’s engineers agreed, would be the Apollo moon mission. After Apollo, their dream was to use spacewalkers to assemble an orbiting space platform.

Back in Houston, the astronauts’ families welcomed them with smiles and hugs. President Johnson pinned medals on both men and promoted them to lieutenant colonel. Then he sent them to represent the United States at the Paris Air Show. In France, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, revered as the first man to fly in space, shared the spotlight with the Gemini twins.8 When White and McDivitt returned home, Chicago honored them with a ticker-tape parade. Not to be outdone, the University of Michigan gave them honorary doctorate degrees. Their new degrees entitled the astronauts to be called Dr. White and Dr. McDivitt.

After the astronauts passed all the necessary medical tests, they were awarded with medals, parades, and honorary degrees. Jim McDivitt (left, holding photo) and Ed White (right) stand with President Johnson (center) as he presents photos of the spacewalk.

Gemini 4 set a bundle of new space records, from total flight time to time spent in EVA. Then, one by one, those records began to tumble. Each new Gemini mission pushed ahead, building on what earlier flights had achieved. By the time Gemini 12 splashed down in November 1966, the United States was well out in front in the space race. President Johnson spoke of these successful flights when he said, “Ten times in . . . the last twenty months we have placed two men in orbit . . . ten times we have brought them home.”9 Thanks to Gemini, NASA was ready to push ahead with the Apollo moon lander program.

Ed White and Jim McDivitt saw the Apollo missions as their ticket for more trips into space. For White, that assignment ended in tragedy. On January 27, 1967, he joined Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee in the command module of Apollo 1. During the countdown, an electric spark started an intensely hot fire in the cabin. A few seconds later, all three astronauts were dead. NASA went back to the drawing board to rethink its safety rules.10

McDivitt returned to space on March 3, 1969, as Apollo 9’s command pilot. During their ten days in Earth orbit, McDivitt, Rusty Schweickart, and Dave Scott gave the lunar module a tough workout. The big test came on their fifth day in space. McDivitt and Schweickart backed the fragile-looking lunar module clear of the Apollo 9 command ship and flew off into the inky blackness. After simulating an ascent from the moon’s surface, they returned to Scott in the command ship. As the docking mechanism snapped into place, cheers erupted in Houston’s control center. All the pieces were in place. It was only a matter of time before a team of astronauts landed on the moon.11

The Apollo 9 mission was the final test before NASA sent astronauts to land on the moon. Jim McDivitt was part of the Apollo 9 crew. In this photo, McDivitt (right) and David Scott take part in a test of the spacecraft.

Six months later, Apollo 11 carried Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins on their historic moon mission. On July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin flew the lunar lander to a soft landing on the moon.

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed,” Armstrong told a waiting world.12 Without a doubt, it was Apollo’s show. Back on Earth, however, the Gemini crews must have felt that they, too, were part of that great moment.