7 Common and commons in the contradictory dynamics between knowledge-based economy and cognitive capitalism

Carlo Vercellone and Alfonso Giuliani

Introduction

Until the end of the 1980s, public and private, state and market still appeared as the two undisputed poles of economic and social organization and forms of property. Both in the debate on economic policies and systemic alternatives, beyond these two poles there seemed to be nothing. This dichotomic vision is increasingly questioned by the recent rediscovery of the theme of the Common, commons and common goods, both in the academic field and by social movements.

This powerful return of the commons takes concrete form in the emergence of alternative forms of self-government of production and resources that bring conflict on the very ground of the conception of the development of productive forces and the relationship between man and nature. In this context, the thesis defended in this chapter is that the Common and commons are far from being a new enclave that would simply complement the traditional representation of the economy based on the public–private dyad, contrary to what Ostromian neo-institutionalist approaches seem to suggest (Ostrom 1990; Coriat 2015a).

The ontological, historically determined ontological basis of the Common’s actuality is not found, in fact, mainly in the intrinsic nature and particular characteristics of certain goods. It lies instead in the capacity of self-organization of work, a capacity that in contemporary capitalism rests on the potential autonomy of cooperation in cognitive work and the development of collective intelligence. In this sense, the Common is always a social and political construction, whether it is its way of organization, as in the choice of criteria that elect or not certain resources, goods or services to the statute of common goods. The Common may therefore in principle concern the management of any type of goods or resource (whether rival or non-rival, excludable or non-excludable, material or immaterial).

According to our approach, the Common must be thought, in Marxian terms, as a real “mode of production” emerging. It is the bearer of an alternative to both the hegemony of the bureaucratic-administrative logic of the state and the capitalist market economy, as a principle of coordination of production and trade in the Marxian sense of the term, an increasingly acute tension between two key elements: (1) the nature of relationships of production, ownership, and appropriation of the increasingly parasitic value of cognitive capitalism, on the one hand; and (2) the living productive forces of a knowledge-based economy and production of humans for and by humans on the other hand, economy that contains within it the possibility of overcoming the capitalist order.

To illustrate these theses, this chapter will be structured in three main stages. The first stage will be dedicated to the key role that the development production of humans for and by humans of the welfare of humans have played, through an eminently conflicting process, both in the training of the productive forces of a knowledge-based economy (KBE) and in the emergence of institutions of the Common. In this context, the strategic reasons that push capital to try to submit welfare institutions to the principles of private management and the extension of the commodification process will also be highlighted.

The second stage will be more specifically devoted to the extension of the commons of information and knowledge. As we will show, they are the result of a dual impulse. On the one hand, they stem from the endogenous dynamic linked to the encounter between collective intelligence and the informational revolution that favours forms of production of knowledge and innovation, based on pooling and free access to resources. On the other hand, they present themselves as a reaction to the movement that, in the opposite direction, pushes capital to unleash the forces of a new and disruptive process of primitive accumulation. The new enclosures of knowledge and living are the main evidence of this.

The result is an increasingly strong tension between the new ethic of knowledge, at the basis of what we will call the “spirit of the common,” and the proprietary logic of cognitive capitalism which, in order to make survive the kingdom of the commodities, through the rarefaction of supply and the construction of annuities of position and monopoly.

In this context, we will return to the debate in economic theory on the justification of intellectual property rights (IPR), and we will analyse the real causes of the speculative bubble of patents that has been produced since the 1980s. This new form of conflict between capital and labour, between the new forms of development of the productive forces of the Common and the relations of capitalist production, does not, however, eliminate another possibility, that which certain theorists qualify as corruption of the Common (Hardt and Negri 2012).

The development of commons would become in this framework the support of a regeneration of the dynamics of cognitive capitalism that would sub-alternatively incorporate the forms of production of the so-called sharing economy. This is a logic in which the commons of knowledge would be reabsorbed within a new dynamic of so-called open innovation governed by the strategies of the great corporations of cognitive capitalism. This scenario, as we will see in the third part, can leverage a series of limits that affect the autonomy and development strength of commons. However, it faces both structural contradictions within the accumulation of capital and the continuing vitality of the Common.

The game is still open, defining the terms of a true historical forking at the heart of the current crisis of capitalism. It is also in this perspective that in the conclusions we will indicate three main axes of an economic and social development model that can guarantee the sustainability of commons and the affirmation of the principles of the Common as a mode of production.

From a welfare state system towards a commonfare system

The institutions of the welfare state present themselves as key pieces at stake in the development of a KBE and the contradictory relationship that the public, private, and common spheres maintain in this framework. In order to illustrate this concept, we shall start from the interpretation of a stylised fact which is often used by economic theory to characterise the emergence of the KBE. We are referring to the historical dynamic by which, in the United States, starting from the mid-1970s, the so-called intangible part of capital (R&D and, above all, education, training, and health) would have surpassed material capital in the global stock of capital (Kendrick 1994) and would have become the most decisive factor of development and competitiveness.

Intangible capital and knowledge economy: the driving role of welfare institutions

The interpretation of this stylised fact has many important and interrelated meanings which, however, are systematically concealed by mainstream economists. These meanings are nonetheless essential to understanding the role of welfare institutions and the profound and often misrepresented objective of the policies which aim at dismantling and privatising them.

The first meaning, on a conceptual level, is the following: in reality, that which we call intangible and intellectual capital is fundamentally incorporated in humans. It corresponds to the intellectual and creative faculties of the labour power, that which is often also called, using a controversial expression, the so-called human capital. Prolonging this reasoning it could be affirmed that the notion of intangible capital in reality merely expresses the way in which in contemporary capitalism the “living knowledge” incorporated in and mobilised by labour now perform, in the social organisation of production, a predominant role compared to dead “knowledge” incorporated in the steady capital and in the managerial organisation of businesses. The second meaning is that the increase in the part of capital called intangible is closely linked to the development of the institutions and collective services of welfare. In particular, it should in fact be emphasised how is actually the expansion of the collective welfare services that has allowed the development of mass education, carrying out a key role in the formation of what we can call collective intelligence or widespread intellectuality: it is in fact the latter, widespread intellectuality that explains the most significant part of the increase in the capital referred to as intangible which, as is emphasised, today represents the essential element of a territory’s potential growth and competitiveness. The third meaning refers to the way in which expansion of the socialised salary (pensions, unemployment benefit, etc.) allows a freeing-up of time mitigating dependency on wage relationships.

From the point of view of the development of a KBE, this freeing-up of time occurs, to use the words of the thesis of general intellect, as an immediate productive force. The socialised salary thus favours access to voluntary mobility between different forms of activities, training, self-improvement, and labour, which create wealth. Even though it is stigmatised today as an unproductive cost and brought back into discussion by workfare policies, it has made an indisputable contribution to the development of the quality of the labour power and the social networks of KBE. It should be noted that even from this point of view Friot (2010, 2012), one of the major French theorists of the sécurité sociale (social-security system), is right to defend the principles of the allotment pension system, founded on the mutualisation of resources, in the terms of a Common institution.1 Considering the active role of a large number of pensioners engaged in the third sector and in knowledge commons, he goes so far as to state that, after all, it is their free and voluntary work that pays a large proportion of their pensions.

The fourth meaning is defined in the fact that, contrary to a widespread idea, the social conditions and key institutions of a KBE are not reducible to only the private R&D laboratories of large companies. These social conditions also and above all correspond to the collective production of humans for and by humans traditionally guaranteed by the institutions of the welfare state, following a logic that essentially, at least in Europe, still escapes from the trade and financial circulation of capital. Furthermore, it is necessary to underline that this appreciation of the role of the welfare system is also confirmed by a comparative analysis on an international scale. Comparison at an international level in fact highlights a strong positive correlation between levels of development of non-commercial services and welfare institutions, on one side, and, on the other, that of the principal indicators of the economic and social effectiveness of a KBE (Vercellone 2010, 2014; Lucarelli and Vercellone 2011). A corollary of this observation is also that a weak level of social inequality, of income and of what is guaranteed by the welfare system goes hand in hand with a much more significant spread of the most advanced forms of organisation of labour, based on the centrality of cognitive labour These forms of organisation of labour, in fact, slip from the grasp of competition based on costs and guarantee lower vulnerability to the international competition from emerging countries (Lorenz and Lundvall 2009).

In conclusion, the main factors of long-term growth and competitiveness of a territory depend more and more, as emphasised by Aglietta (1997), on collective factors of productivity (general level of education and training of the labour power, the interactions of it within a territory, the quality of the infrastructures and research, and so on).

In particular, these are the factors that permit the circulation of knowledge in a territory, generating for the same businesses externalities of networks and dynamic learning economies, the essential foundations for technical progress and endogenous growth. On a macro-economic level, this also means that the conditions of training and reproduction of the labour power are by now directly or indirectly productive. To paraphrase Adam Smith, but reaching the opposite conclusion, the origin of “wealth of nations” rests ever more today on productive cooperation situated in society, outside companies, that is to say on social and institutional mechanisms that permit the circulation and pooling of knowledge, and with this a cumulative trend of innovation (Vercellone 2011). The development of the knowledge commons, like the attempt by enterprise to promote “open innovation platforms” in order to capture knowledge produced outside it, are one of the key manifestations of this. Despite their importance, teachings drawn from these stylised facts are generally ignored by academic output on the knowledge economy and by reports that contribute to the definition of guidelines of economic policies and structural reform in Europe. This forgetfulness is all the more serious in a context where the policies of austerity and privatisation risk profoundly destabilising, together with the welfare institutions, the very conditions for the development of a KBE and thus of potential long-run growth. The risk is thus to witness—notwithstanding the fact that it is happening for an opposite cause to that suggested by Garret Hardin’s well-known article (1968)—what we can call a new “tragedy of the commons” caused by the dynamics of cognitive and financialised capitalism, a tragedy of the Commons that, it must not be forgotten, goes step by step with that of the anti-commons linked to the excessive privatisation of knowledge. Numerous researches have in fact made it possible to highlight the short-sightedness of the neoliberalist policies conducted in Europe today.2

Apart from the theoretical weight of the precepts of neo-liberalism, one of the explanations for the persistence of these policies (privatisation strategies) can probably be found in the stakes, represented for the large multinational companies by the control and commercial colonisation of the welfare institutions, and this is due to two main structural reasons. The first reason is that health, public research, education, training, and culture do not only form lifestyles and subjectivity but also constitute the pillars of regulation and orientation of a KBE. The second reason is that the production of humans for and by humans also represent a growing part of production and social demand, demand which up to now, at least in Europe, has mainly been satisfied outside the logic of the market. In the face of ever more pronounced stagnational trends, since before the outbreak of the crisis, the commodification of the welfare institutions thus constitutes one of the last frontiers for the expansion of the logic of the market and the financialisation of the economy (for example through the transformation to a capitalisation pension scheme). On this point, we note that, contrary to the dominating ideological talk that censures costs and the supposed unproductiveness of welfare institutions, the objective of the neo-liberalist policies is thus not the reduction of the absolute amount of these expenses but rather that of their reintegration into private-sector commercial and financial circulation. To be sure, the expansion of the privatistic logic in these sectors is theoretically possible. Let us remember nevertheless that health, education, research, etc., correspond to activities that cannot be subordinated to the economic rationality of the private sector, unless at the cost of rationing of resources, profound social inequalities and, all in all, a drastic lowering of the social effectiveness of these productions. The result would be an unavoidable drop of the very quantity and quality of the so-called intangible capital that, as we have seen, by now constitutes in contemporary capitalism the key factor in the development of the productive forces and potential growth.

Three principal arguments support these theses regarding the counterproductive character and the perverse effects of subjugation of the collective production of humans for and by humans to the economic rationality of the private sector.

The first argument is linked to the intrinsically cognitive, interactive, and emotional character of these activities, in which the work does not consist of acting on inanimate matter but on humankind itself in a relationship of co-production of services. As a matter of fact, on the level of criteria of effectiveness, these activities escape from the economic rationality suited to capitalism, which is founded on an essentially quantitative concept of productivity that can be summarised through a concise formula: to produce more and more with a smaller quantity of labour and capital so as to reduce costs and increase profits. This type of rationality has without doubt given proof of some efficiency in the productions of standardised material commodities destined for private family consumption. In this way, it enabled, during the Fordist growth, a growing load of commodities to be produced with less and less work, thus also with decreasing costs and prices, in this way satisfying a significant volume of needs; it matters little whether they be authentic, driven or superfluous. Nonetheless, the production of humans for and by humans respond to a completely different productive rationality and this is for three main reasons:

- Due to their intrinsically cognitive and relational nature, neither the activities of work, not the production can really be standardised.

- In these activities, effectiveness in terms of result depends on a whole series of qualitative variables tied to communication, density of human relationships, uninterested care and thus to the availability of time for others, which the rationality of companies, or New Public Management, would be unable to integrate unless as costs and unproductive downtimes.

- Lastly, as Boyer (2004) notes, in these activities, particularly in the health sector, technological progress that permits improvement in the qualitative effectiveness of production is translated almost systematically in a cost increase and a decrease in overall productivity of factors that sets off the increase in the well-being of populations. All in all, the attempt to raise profitability and productivity of these activities therefore cannot be carried out except to the detriment to their quality and so to their social effectiveness. We could even argue that in these activities today, the problem regarding the improvement of effectiveness and quality does not require an increase in productivity but rather a reduction of it (Gadrey 2010). Here we have a first series of factors connected to their means of production which explain why these collective services are unlikely to be compatible with the logic of production and profitability of the private sector, and, on the other hand, they appear as a terrain with a predilection for practices of co-production and mutualisation of the resources themselves to the logic of common.

The second argument is tied to the profound distortions that application of the principle of solvent demand would introduce in the allocation of resources and the right of access to these common goods. By definition the productions of Common are based on universal rights. Financing them cannot therefore be ensured except through the collective price represented by social contributions, taxation or other forms of mutualisation of resources.

The third argument is tied to the way in which in the production of humans for and by humans the mythical figure of a perfectly informed consumer does not exist in reality, he/she who would make their own choices on the basis of rational calculation of the costs/benefits dictated by research into the maximum efficiency of the investment in their own human capital. This is certainly not the main criterion that stimulates a student in their search for knowledge. It is even less that of a sick person who, in the majority of cases, is imprisoned by a state of anguish that makes them incapable of making a rational choice and predisposes them instead to all the traps of a commercial logic in which selling hopes and illusions is a means of making a profit.

From this point of view. it is interesting to note how the neo-liberalist policies of financial responsibilisation of the consumer in the field of health which also make them bear a growing part of the expenses of social protection, seem to take up, almost passage for passage, Hardin’s old argumentation on welfare as an example of the tragedy of the commons. As Boutifilier (2014) demonstrates, these policies nonetheless not only do not lead to a decrease in expenses (quite the opposite) but appear to have profoundly perverse effects on treatments and therefore on the effectiveness itself of the human capital. In conclusion, all these reasons tied both to their means of production, consumption, and finance explain the economic and social tensions provoked by the continuation of a policy of transformation of the production of humans for and by humans into private goods. This would risk dismantling the structure of the most essential conditions at the base of the reproduction of a KBE. Experimentation of a model of commonfare finds here one of its principal justifications and could constitute, in the age of the KBE, a fresh form of re-socialisation of the economy, in the manner of Polanyi (1944).

The knowledge-based and digital economy between the dynamics of commons and the new enclosures

In cognitive capitalism, the dynamics of the knowledge and digital commons is the other side of the coin, the reciprocal antagonist, of what is called the tragedy of the anticommons, tied to excessive privatisation of knowledge. Besides, the entire history of the development of a KBE and the information evolution itself is an illustration of this crucial aspect. From the conception of the first software up to that of the web protocols released by Tim Berners-Lee into the public domain, not forgetting the legal innovation of copyleft, the open nature of information technologies and the standards of the net is largely the product of a social construction of the commons. A construction in permanent conflict both with the state logic and with that of ownership generated by the great oligopolies of the internet and high-tech industries.

This evolution enters the in-depth debate which has started again of the regime of knowledge and innovation inherited from industrial capitalism and founded on the public–private pairing.

Knowledge as a public good and product of a specialized sector: the Fordist paradigm

In order to better comprehend the sense of this process on a theoretical and historical level, it is useful to start again from the dominant concept of knowledge theorized in the Fordist era by the founding fathers of the economic theory of knowledge and sociology of the science, that is respectively by Kenneth J. Arrow and Robert K. Merton.

The basic model of the economic theory of knowledge and market failures

Arrow’s article, “Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resource for Invention”(1962), is considered to be the founding essay on the KBE. The author’s approach rests on two principal arguments. The first concerns the agents and the methods of knowledge production. According to Arrow, the essentials of scientific and technological knowledge are created by an elite of researchers who act and reflect in separate places from the rest of society and situated at a distance from production, in R&D laboratories and in highly intense technological industries. The activity of innovation is thus represented as the result of a sector specialized in the production of knowledge on the basis of a function of production that combines highly qualified labour and capital.3 The second argument concerns the nature of knowledge or information as an “economic good.”4 In continuity with the neo-classical typology of goods, knowledge (or information), according to Arrow presents three main characteristics that make it an imperfect public good: its non-rivalrous, difficultly excludable, and cumulative nature. Unlike material goods, consumption of knowledge does not destroy it. On the contrary, it is enriched when it circulates freely among individuals. Every new item of knowledge generates another item of knowledge following a virtuous (not vicious) circle that permits each creator, as Newton reminded us, to be “like dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants.” For these reasons, knowledge is a good which is difficult to control. In other words, Arrow emphasizes how it is very simple for subjects other than those who invested in the production of the knowledge to come into its possession and use it without paying any market price. This transferability of knowledge is so much higher that it assimilates knowledge to information, mistakenly supposing that it is perfectly codable.

Given the characteristics of the knowledge as economic good, Arrow considers that its production represents a typical example of market failure: that is the production of knowledge, if left to mechanisms of the market and the initiative of private enterprise, would lead to a sub-optimal situation. The marginal private advantage of the economic subject who makes investments is lower than the social one. For these reasons, the state must intervene and play an active role in the production of knowledge, particularly in the finance and organization of fundamental research. Its results must be placed freely at the disposal of the rest of society as a public good. Certainly, Arrow also predicts instruments aimed at boosting applied research in companies, for example through IPR. Nevertheless, he considers that these instruments are unable to eliminate the gap between social advantages and private benefits, taking into account also the short-run horizon on the basis of which businesses make investment decisions according to profitability. In short, a precise division of labour is established between public-sector and private-sector research: the first provides basic knowledge mainly tied to fundamental research free of charge, like a public good; the second develops applied research in the framework of the large R&D laboratories of the large managerial enterprises. Innovation is internally produced, and resort to the monopoly of intellectual property performs a secondary role.

The norm of open science according to Merton

Merton, the founding father of the sociology of science, actually shares this representation. He completes it defining the ethos of the science and the norms of regulation of the public activity of scientists’ research according to the principles of open science. From this perspective, he defines four “institutional imperatives” (Merton 1973: 270–278):

- Universalism: knowledge and scientific results are judged independently from characteristics inherent to the subject which formulated them, such as social class, political and religious opinions, sex and ethnic origins (Merton 1973: 270–273).

- “Communism”: in the non-technical and extended sense of common ownership of goods, is a second integral element of the scientific ethos. The substantive findings of science are a product of social collaboration and are assigned to the community. They constitute a common heritage in which the equity of the individual producer is severely limited […] The scientist’s claim to “their” intellectual “property” is limited to that of recognition and esteem which, if the institution functions with a modicum of efficiency, is roughly commensurate with the significance of the increments brought to the common fund of knowledge.

And it is Merton who states that common ownership exactly “of the scientific ethos is incompatible with the definition of technology as ‘private property’ in a capitalistic economy” (1973: 275). In short, results and discoveries are not the property of a single researcher but a legacy of the scientific community and society as a whole. A scientist does not obtain recognition for their own work unless by making it public and therefore placing it at the disposal of others. The researcher’s objective thus becomes that of publishing the results of their own research first and as fast as possible, instead of keeping them secret and/or submitting them to the monopoly of intellectual property, as on the other hand is more and more the case today in the field of scientific research.

- Disinterestedness: each researcher pursues the primary objective of the progress of knowledge, obtaining recognition from their community of peers. This recognition can be translated into reputation and career advancement but not into the possibility of personal enrichment based on privatization of knowledge through, for example, patents or other business initiatives for profit.

- Organized skepticism: this consists of institutional devices, like Peer Review, which permit the systematic presentation of scientific results to the critical examination of the peer community.

In brief, according to Merton, the “institutional imperatives” for publication, pooling, and free circulation of research results make it possible to guarantee a system of open science and common ownership, though within a limited community of researchers and people working in those areas. This is a logic that, as we will see, presents some analogies with the model of free software and common ownership set up by copyleft which constitute an original construction.

The development of cognitive capitalism and the crisis of the Arrowian and Mertonian paradigm of knowledge

Whether it is in connection with the representation of the subjects of knowledge production, the regulatory role of the public sector or the ethos of the science, the Arrowian and Mertonian paradigm is in crisis today. All these pillars of the regime of knowledge and innovation in force in the age of Fordist capitalism have been profoundly destabilized by two opposing dynamics passing through cognitive capitalism.

Knowledge as a socially widespread activity

The first is about the way in which knowledge production slips away more and more from the traditional places assigned for its production. In short, in contrast with what the Arrow and Merton models postulated,5 learning and intellectual labour are no longer, as Smith stated in The Wealth of Nations, “like every other employment, the principal or sole trade and occupation of a particular class of citizens”(1981: 70). They progressively spread and become manifest within society, even through the development of decentralized and autonomous forms of organization compared to the norms of public research centres and those of large private companies (Vercellone 2013). As David and Foray underline (2002: 10), “a knowledge economy appears when a group of people intensively co-produce (i.e. produce and exchange) new knowledge with the aid of ITC” sometimes establishing genuine knowledge commons. At the centre of this process we find two subjective and structural transformations. In the first place, as previously emphasized, is the success of a widespread intellectuality. It is only the latter that can, in fact, explain the development of knowledge-intensive communities which are able to organize themselves, share, and produce knowledge. It is a new dynamic, completely inconceivable even at the end of the twentieth century by theorists of economy and the sociology of knowledge. A dynamic that can go from the simple creation and sharing of a database, up to complex forms of co-production of intangible and material goods. As in the case of free software, biohackers and even more so, the makers, knowledge commons can develop on a technological frontier that challenges the supremacy of the public sector and large private companies on the level of economic efficiency and capacity for innovation.

On this terrain, there is the meeting and hybridization between Merton’s science ethos model and new forms of open knowledge promoted by the practices and cultural models tied to the development of a collective intelligence.

Towards the science paradigm 2.0: New Public Management and the privatization of knowledge

The second dynamic at the base of the destabilization of the Arrowian and Mertonian model is a powerful process of privatization of knowledge that goes hand in hand with the subordination of public research to the short-run imperatives of private profitability. The result is a debate about the concept of knowledge as a public good and the traditional role assigned to the state in its regulation in the Fordist era. The starting point of this evolution is found in the United States between the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s in a context in which the debate on economic and industrial policy is dominated by the problem of the loss of competitivity of American industry compared to Japan.

This results in the drawing up of a new strategy oriented at moving the norms of international competition ever more to the bottom of the production sphere, on the same level as the results of basic research. Under the thrust of the finance and lobbying of the large-scale enterprises in the pharmaceutic, information technology, and biotechnology sectors between the 1980s and 1990s, this strategy is marked by four main institutional innovations.

The first is constituted in 1980 by the Bayh–Dole Act, which marks the birth of the Science Model 2.0. 6 This grants universities and non-profit-making institutions the right to exploit and commercialize inventions made with public research funds in their laboratories. The law equally encourages universities to transfer patented technologies to the private sector, in particular through exclusive licences.

The second innovation refers to the 1980 sentence of the Supreme Court (in the Diamond v. Chakrabarty case) which extends protection to any natural product created through genetic engineering, recognizing that genetically modified bacteria are patentable in themselves, that is to say independently of their process of exploitation. Starting from this moment, the instances of obtaining patents on cell lines, gene sequences, animals, and plants have multiplied. The same is true for living organisms that are sufficiently modified to be able to be considered manufactured products. The distinction between discovery and invention is practically erased.

The third concerns the extension of IPR to software according to a process produced through two principal stages. In 1980, following the recommendations of the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works (CONTU), US Congress extended the possibility of copyright protection to software. As Mangolte (2013) recalls, it is nonetheless patents that are used initially. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) in fact rapidly accepted the introduction of patents in the field of software whether or not they were tied to hardware. However, their validity was strongly fought over on the legal front as the algorithms were still connected to ideas and not to tangible artefacts. Because of this, the copyright route seemed more secure as an ownership strategy, at least until the decision relating to a case in favour of patents on software backed by a 1996 USPTO document.

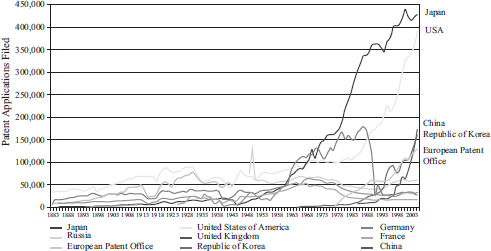

Finally, in 1994, the agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) for the first time in history establishes at world level a regime of IPRs which are binding for all the countries of the globe, in contrast with the United States’ essentially national regulation upon which besides the strategy of technological catching-up besides had relied in the past, like all the other countries in course of industrialization. In conclusion, the reorganization of the relationship between public and private sector and the IPR regime leads to a real explosion in the process of patenting that is demonstrated through a radical break with respect to the long-dating historic trend regarding the number of patents filed between 1883 and the beginning of the 1980s (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Evolution of worldwide patent filings in the long run

Source: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) statistics database

Note: WIPO PATENT REPORT: Statistics on Worldwide Patent Activities, 2007

Patents: a necessary evil or a useless evil?

The excess privatization of knowledge that seems to characterize contemporary capitalism is responsible for creating a tragedy of anticommons. Three key elements will enable us to better understand the signification of this evolution. A first element concerns the extension of the field of patentability. In industrial capitalism, the possibility of resort to the monopoly of intellectual property of the patent was limited to technical devices and products that had to prove their originality, that is to say to be an expression of human creativity and not therefore come from nature but be registered as technological artefacts inherent to the “arts and crafts.” The strengthening and extension of IPR that has been produced since the 1980s is not only about the possibility to patent ever more superficial devices, for example Amazon’s idea of the “click.” It concerns the weakening itself of the traditional frontier between discovery and invention and therefore between basic research and applied research. Algorithms, sequences of the human genome, plants, seeds, genetically modified organisms, even the isolation of a virus,7 have now entered the range of patentability in fact permitting the privatization of something living and of knowledge as such, of all that is often described in classic texts of Western political thought as a legacy of all humankind to share together (Hardt and Negri 2012; Shiva 2001).

The second element concerns the way in which the obsession for privatization of knowledge at any cost leads to an inefficient use of resources. According to the statistics drawn up by Marc-André Gagnon (2015) in the pharmaceutical industry, for example, the administrative legal costs for obtaining and defending IPRs are higher than those devoted to R&D. This disproportion between unproductive expenses and investment in R&D is even more considerable if integrated with the expenses mobilized on publicity and marketing to promote products and services with an ever more superficial innovative content. The patent then becomes more and more an instrument to renew monopoly rents by replacing, without significant innovations, the blockbuster drugs becoming part of the public domain and therefore in the production of generic medicines.

The third element concerns the misleading nature of the traditional argument according to which the patent is a necessary evil, in the framework of a difficult arbitration between static inefficiencies (a patent translates into price increases for the consumer and a lower use of the invention) and dynamic efficiency, tied to the increase of the rate of innovation. As a matter of fact, it is argued that in the absence of a provisional monopoly guaranteed by patents, certain innovations would not come about due to lack of profitability. To demonstrate the weakness of this theory, Boldrin and Levine (2008) have emphasized how in the case of an authentic invention, that is not banal, characterized by a certain level of technical complexity, the advantage of time that the innovator has at their disposal is a competitive factor sufficient to justify and remunerate investment in the innovation. The reason is simple: knowledge does not correspond only to its coded part but rests on a blend of tacit knowledge that requires a long time to be learned before a potential competitor can manage to imitate and improve the innovation in question (Vercellone 2014).

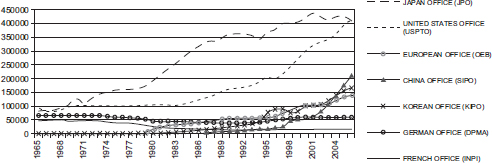

In conclusion, it is possible to maintain that the patent, especially as far as authentic radical innovations are concerned, is not a necessary evil. It is purely and simply a useless evil (Boldrin and Levine 2008), at least if one reasons from the point of view of the dynamics of innovation and not from those of the monopoly rents that large enterprises can obtain thanks to holding these patents.8 Proof of this is also the way in which the explosion of patent applications that happened in all the OECD countries starting from the 1980s, did absolutely not go hand in hand with a parallel increase of the Total Factor Productivity (TFP) which, according to economic theory, ought to constitute the principal indicator of technical progress. On the contrary, compared to an explosion in the number of patent filings which went, for example in the United States, from an average of 90,000 a year in the 1960s to 345,000 in the 1990s, leaping up again in the first ten years of the twenty-first century (482,871 in 2009; 501,162 in 2013. See Figure 7.2),9 it is necessary to observe that the dynamics of the TFP in the past fifty years has not shown any tendency to grow (Boldrin and Levine 2008: 79).

Figure 7.2 Trends in patent filings at selected patent office, 1965–2006

Source: Lallement (2008: 3). Data from Centre d’Analyse Stratégique

The second item of empirical evidence is the observation according to which the increase in the number of patents is associated, in the United States, as in Europe, with a strong deterioration of the average quality of the patents in terms of innovation originality (Lallement 2008). As shown in a detailed empirical study by Rémi Lallement for Europe, this evolution goes hand in hand with a use of IPR that, particularly as far as large enterprises are concerned (40.8 per cent of patents), tends more and more to favour the functions of patents as instruments to block competition and not in view of potential innovation.

A last argument that confirms and clarifies the affirmation according to which the patent is often more of a pointless evil than a necessary evil is provided by the long-run dynamics of economic history. In reality, it is in fact very difficult to find an example of a radical innovation in economic history, caused by the existence of the system of patents as an instigative factor.10 Rather, we notice an inverse causative sequence. The same institution of IPRs is a phenomenon that follows and does not precede a cluster of radical innovations. Proof of this is the same historic genesis of the first structured legislation on patents, developed in Venice in 1474 to then spread to the rest of Europe. In fact, it was produced after and in reaction to the problems of controlling knowledge generated by the invention of movable type printing and by the spread of the information revolution of the so-called Gutenberg galaxy (May 2002).

This observation is perhaps even truer for the information revolution in contemporary capitalism which, as Bill Gates himself explicitly acknowledged, could never have happened if at that time we had the arsenal of IPRs that has developed since the 1980s. As shown also by the works of Bessen and Maskin (2000), the re-enforcement of intellectual property regulations in the United States during the 1980s reduced innovation and translated into a decline in R&D in the industries and corporations that were most active in patenting their work, and this in stark contrast with the dynamism and innovative capacity of which the model of open source and copyleft is proof in the same period.

More precisely three logical-historical steps can be distinguished in the development of the information revolution and the new knowledge commons. In the first, the dynamics of the principal radical innovations at the base of the information revolution are driven from the bottom. In this framework, resort to IPRs is still relatively rare and not structured by the new norms of privatization which will gradually come into force starting from the 1980s. It is a process in which the very concept of technological innovation strongly bears the stamp of the dissenting counterculture of the American campus and of what Boltanski and Chiappello (1999) have called the “artistic critique.”

In the second, continuation of this dynamic of open-science and open-knowledge innovation must be placed even more explicitly in opposition to the ownership model. In contrast with the development of biopiracy and the processes of privatization and standardization of the living, this conflictual logic also concerns more and more the construction of the commons of biodiversity and agriculture. Two consequences ensue. The movement of the commons has to give itself a more formalized organizational structure and conceive original legal forms of common ownership such as copyleft to protect itself from the “predatory” practices of the private sector. The great oligopolies that have formed in the framework of the information revolution set up strategies that lead to the tragedy of the anticommons of knowledge and to processes of recentralization of the net which, like for the platforms of the well-known GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) destabilize its open and decentralized structure.

In the third, the protagonists of the ownership model become ever more aware of the limits that the logic of fencing in and secrecy tied to the IPRs implies for their own capacity of innovation. It appears more and more to be a limit in the face of an embittering of the competition in the international division of labour knowledge-based. To compensate for this impasse digital and bio-technological capitalism sets up strategies which try to recover the commons model from within, by imitation or co-optation. At the same time, the logic of the knowledge commons spreads more and more to new activities and productive branches, defining, after the model of free software, that of the makers which appears to lay the foundations of a possible new industrial revolution.

The information revolution of the PC and the net: in the beginning was the common

The development of the commons and the principles of free software is often considered to be a reaction to the property excesses of cognitive capitalism. This concept provides an inexact picture of a technological revolution that found its driving force in the system of private capitalist economy and in the role of Big Science organized by the public research system.

Thus, in standard presentations of the IT (information technology) revolution, the idealized figure of the great businessmen of success Bill Gates-style often crosses that of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANet), an embryonic form from which Internet was born subsequently in 1983, created in 1969 by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency responsible for the development of new technologies for military use of the United States.

The part of truth contained in this reconstruction is a little like the tree that hides the forest of creative effervescence of multitudes of hackers and hobbyists mobilized much more by the search for technological virtuosity11 than by that of personal enrichment and profit. The IT sector is perhaps the best contemporary illustration of the way in which the monopoly of intellectual property is not the cause of innovation. It is rather a consequence that intervenes when the development of a sector, having reached a certain degree of maturity, sees the way to build economic rent and prevent dynamics that could undermine them in resorting to and strengthening the IPRs. The main innovations at the base of the start of the information revolution and the conception of the Internet could not have taken place without the determining role of practices founded on the Common and driven by alternative motivations both to the logic of private and that of public. It is not only the fact that at the dawn of the ICT (information communication technology) revolution, in the 1960s and 1970s, practices of sharing the source code and the gratuitousness of software constituted the norm of co-operation in the work of those employed in IT (Mangolte 2013). It is also and above all the fact that the birth of a new socio-technical paradigm never obeys narrow technological determinism but is the result of a social construction that is engraved in a trajectory of innovation that expresses the interests and visions of the world of the players who are its protagonists.12 So, unquestionably, on the level of innovative practice, the anti-authoritarian countercultures that developed on American campuses in the 1960s and their meeting with the open-knowledge culture which at the time still innervated the university world in the United States, have been of decisive importance in the history of the IT revolution. As Delfanti (2013a: 30) stresses, “from the bond between activists for the freedom of information who dreamt of using computers as an instrument of communication for the resistant communities and the hobbyists of Silicon Valley […] the libertarian ethos emerged that partially guided the evolution of computers towards what they are today.”

In turn, Michel Lallement (2013) proposes a winning historic reconstruction of the experiences of the counterculture of the hippy community that developed in California in the 1960s and 1970s and in which were embedded personalities such as Gordon French and Fred Moore, founders in 1975 of the Homebrew Computer Club, the first real model of hackerspace. It is right in this club, around the first accessible personal computer, the Altair 8800, they are to produce innovative experimentations and decisive meetings for the conception of our modern personal computer. It is again this libertarian and democratic “ethics” that explain the ‘sociology’ of principles innovations, as modem, that will lead to the birth of Internet (Cohen 2006). In particular, this ethics of the open knowledge leads Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau to convince the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) to release in 1993 the web protocols, including the source code of the first navigator,13 into the public domain. Rapid diffusion is made possible in this way, thanks to the lack of patents on the standard of the net, and this happens while in the United States we witness the rise of software patenting; in France, Minitel’s closed pay-for model still predominates.

In short, it is a very precise socio-technical trajectory thought out on the basis of the Common and in function of the creation of the infrastructures of the Common that allows open and original structures to be conceived according to a dynamic that will find two fundamental and closely bound achievements:

- the free-software model with its best-known concrete creations like GNU/Linux, Firefox, Apache, LibreOffice, Thunderbird and VideoLAN Client (VLC);

- the open architecture nature of the Web designed by Tim Berners-Lee like a global hypertext in which all the sites in the world can be consulted and fed by everyone.

In this manner, personal computers put in a network through the internet are, at least potentially, like “a universal tool accessible to everyone thanks to all the knowledge and all the activities that can in principle be put in common” (Gorz 2003: 21 [our translation]).14 In fact, the information revolution and its emblematic product, the net, are not limited, as is often stated by mainstream theorists of the knowledge economy, to bringing about an extraordinary reduction in the costs of transmission and codification of knowledge itself. It introduces two other greater qualitative breaks compared to previous information revolutions in the history of humankind, in particular, after that of writing, the revolution of movable type printing that gave rise to the formation of the Gutenberg galaxy.

The first break consists in the fact that information and knowledge, like all digitizable cultural products, can now circulate independently from a material medium, like, for example, a book. This dematerialization not only drastically reduces the costs of the technical reproduction of intellectual labour making them enter an economy of abundance and at zero marginal cost. It also results in their emancipation from the control mechanisms, censorship and selection that in the past the state and market could exercise over them acting on their material media.

The second qualitative break consists in the way in which the net radically destabilizes the terms of the classic producer/consumer, creator/public, issuer/user dichotomies, that up to today had structured the workings of all traditional media. The Internet, in particular, in fact consents the transition from a classic relationship pattern from one toward everyone, usually mediated by a mercantile or administrative/bureaucratic relationship, to an interactive pattern from everyone toward everyone. The circulation of information and the production of knowledge can thus become a cooperative process that mobilizes the intelligence of multitudes on a global scale. It is a dynamic of which one of the best exemplifications is without doubt that of Wikipedia, the open encyclopedia that has actually, for the number of terms, but also for the reliability of the content, now definitively won the competition with the noble Encyclopædia Britannica.

This decentralized and democratic aspect is undoubtedly the most revolutionary trait of the Internet which makes it the most suitable infrastructure of the Common for the development of a KBE founded on the autonomy of cognitive labour and collective intelligence. Again, for this reason, bringing up for discussion again the neutrality of the net and its open structure is the objective on which the attempts at recentralization of the Internet are focused in order to re-establish the supremacy of mercantile mediation and/or bureaucratic-administrative control of the public. This logic stirs up animated disputes due to its perverse effects on the freedom of citizens and the dynamics of the circulation of knowledge that constitutes one of the key conditions for the development and sustainability of the commons. Around what is at stake here a complex and highly conflictual dialectic is unravelling more and more that opposes the spirit of Common 15 from the dawn of the KBE to that of a new spirit of digital and cognitive capitalism, which is trying to reabsorb the former within its operational mechanisms.

The spirit of Common: the meeting between the Mertonian culture of open science and hacker ethics

Like Max Weber spoke of the spirit of industrial capitalism, relating it to Protestant ethics, it is possible to speak of a spirit of Common that has innervated the open nature of IT technologies and the standards of the Web just as the resistance to the growth of ownership capitalism. Like the spirit of capitalism, the spirit of Common also has a historical and socio-cultural base which it is possible to formalize in an ideal-type model.16 It presents itself as the result of the meeting and hybridization between the ethos of open science, described by Merton and the hacker spirit of collective intelligence defined by Pekka Himanen,17 according to a model that under many aspects is incarnated in the figures respectively of Richard Stallman and Tim Berners-Lee. The new generation brought up on widespread knowledge takes up and reformulates the four fundamental Mertonian principles of universalism, communism, disinterestedness, and organized skepticism. It integrate them in a new system of values in which the main points are the following:

- Universalism is structured around the criticism of the closure and the claim of official scientific institutions to hold a monopoly on knowledge. In the hacker spirit and that of the counterculture of widespread intellectuality the values of sharing and cooperation extend to the whole of society, independently of the qualifications and the professional status of an individual: this is a typical aspect of a society based on collective intelligence.

- Communism or scientific communitarianism, in which knowledge is considered to be common ownership, takes up the basic imperative again of the publication of results of research and putting them at the disposal of the whole of society. In the hacker philosophy, this need is combined, however, with the awareness that publication, as in the case of an open-source software, as an instrument is no longer sufficient to prevent attempts at private appropriation. From this perspective, legal mechanisms that permit the creation of a protected common ownership, i.e. a non-appropriable public domain, to which each can add something but not take anything away for private benefit.

- Disinterestedness. As in Mertonian open science, the hacker philosophy pursues the disinterested objective of progress of knowledge. It differs however from the ethos of scientist which remains largely structured by the Weberian ethic of work as a duty and an end in itself (Merton 1973). Rather, disinterest is associated with a Fourierist concept of work thought of as a creative, even if terribly serious, game. It is about the passion of the cognitive effort, recompense for which, as in the Mertonian model, consists in the recognition of one’s peers and the community of users.

- Organized Skepticism. Finally, the hackers as in the science world have adopted the model of organized skepticism and open knowledge as the most functional for the production of new knowledge. However, the hacker spirit differs because of its refusal of academic hierarchy and a structured career of regulated bureaucratic passages.

On this basis, it elaborates two new closely bound principles lacking from the Mertonian universe of open science: the principle of the do-cracy (the power of doing) which indicates research of maximal individual autonomy and which opposes any external directive and interference, potentially giving each person the influence that comes out of their own initiatives; and the principle of direct horizontal cooperation intended as a form of self-organization in which individuals co-ordinate themselves, allocating themselves tasks that they carry out taking full responsibility for them. We note that the last two principles are also the most general expression of the culture refusing work directed by others and aspiring to self-management that has characterized the main social movements of widespread intellectuality over the past decades, from the experience of the social centres in Italy up to that of the indignados in Spain.

Do-cracy, horizontal co-operation and cognitive division of labour: the controversy on the nature of the productive model of free software and open source

This combination between direct co-operation and glorification of individual autonomy in which the individuals themselves allocate themselves tasks and objectives and appeal to others to carry them out gives rise to a particularly effective form of cognitive division of labour.18 This model of self-management of cognitive labour rests on different strongly autonomous small groups. As Jollivet (2002: 165) stresses, “the work carried out in these hacker communities, like in project Linux, for example, is directly co-operative and voluntary work the structure of which is horizontal” (our translation). These characteristics are important for two reasons.

The first is that they correspond to a form of co-ordination belonging to the commons, in alternative both to the hierarchy and the market, the effectiveness of which made it during the 1990s the most serious competitor to the monopoly of Microsoft and to the logic of the ownership model of the so-called new economy (Boyer 2002).

The second is that the explanation for the effectiveness of these models constitutes an important controversial element with some defenders of the standard neo-classic approach of labour economics. In particular, economists like Lerner and Tirole (2000) refute any originality in the model of labour organization in the hacker community of the Linux type. They maintain, in fact, that there is really nothing different in the world of hacking and free software compared to the traditional way enterprises function. Hacking stars, like Linus Torvalds and Richard Stallman, would in fact carry out a role in the productive organization of free software identical to that of a company director. Jollivet (2002), basing himself on Himanen’s analysis, supplies numerous elements to refute this theory. He states first of all that the relative lack of organizational structures does not mean that they are missing. The organizational structure is that of a horizontal network that, however, does not profess to be totally flat. In fact, in the free-software project there are prominent personalities who, inside small committees, have an unquestionable influence over certain choices, in particular over the contributions that have to be integrated or not in the programme in question. Nonetheless, there is a fundamental difference between these figures and a hierarchical superior. As Himanen (2001: 80) emphasizes, “the statute of authority is open to everyone.” This is a decisive point characterizing the institutional specificness and the production model of free-software projects: the means of production are in fact placed in common, and no one can take advantage of the property right of the software produced under free license. Here there is a substantial divergence compared to the classic enterprise model in which the power of ownership of things (production tools and capital supplied) confers the power of direction over humans and the right to appropriate the product of the labour. So, for example, in the models of the agency theory (Jensen and Mekling 1976), to which Lerner and Tirole refer, the managers or leaders are, according to the supremacy of private-property rights, agents of the shareholders only. In a classic enterprise—and this is even truer in companies where the main capital is the so-called human or intellectual capital—this hierarchical structure can lead to recurring conflicts between ownership power and decision-making power of those who hold adequate knowledge (Weinstein 2010). The rigidity of the structures of control and decision-making tied to ownership often interfere with the mechanisms that should guarantee the most efficient forms of organization of a cognitive division of labour (Vercellone 2013a, 2014).

In the free-software model, the absence of ownership instead determines the social conditions which ensure that authority is effectively open and removable, guaranteeing democracy and collective deliberation both as far as the labour organisation and the purposes of the production. For this reason, the free-software model is also more flexible and reactive than the hierarchical model. As a matter of fact, if the decisions taken by one of the micro-structures of arbitration are considered unsatisfactory by a significant number of contributors to the project, nothing is simpler than setting up the process of removal of the leadership of project in hand. Concerning this, it is sufficient for a dissident group to duplicate—which is perfectly legal in general public license (GPL) licenses—the program source codes, set themselves up as a holding group of an alternative project with an internet site appealing to other contributors so that they join the new project (Jollivet 2002). The inappropriability of goods produced in a project of the free-software type (right of duplication and modification) thus constitutes a fundamental incentive to do things in such a way that the traditional schemes of hierarchical authority of an enterprise are not reproducible. This mechanism explains not only why “the statute of authority is open to anyone,” but equally why it is “solely founded on results” (Jollivet 2002: 166). In this way, no one can occupy a role in which their work is not subjected to the examination of their peers in the same way as the creations of any other individual (Himanen 2001: 80–82). The individuals to whom authority is delegated temporarily and revocably are those who enjoy the greatest admiration from their peers.

Copyleft and common property in the free-software movement

For certain authors, like Dardot and Laval (2014), common is constituent acting and forms of institutionalization of common property outside a permanent procedure of commoning cannot exist. For other authors, like Coriat (2015) and Broca (2013), the example of copyleft would on the other hand prove it is possible to set up a form of common property that guarantees free access to a stock of resources independently of the activity of commoning. Examination of the free-software model allows us to demonstrate the innate error in both these positions. The case of copyleft rests in fact on a close synergy between a form of common property founded on rights of use, on the one hand, and a logic of cooperative acting belonging to the Common as it is the mode of production organization, on the other hand. There is no disjunction, but a process of reciprocal fertilization between the activity of commoning and the legal regime of copyleft. This process illustrates the way in which labour co-operation, the ontological foundation of the Common, can generate legal forms that promote coherent governance for it and its reproduction (Hardt and Negri 2012). The history of the dynamics through which the free-software movement (FSM) arrived at the formulation of copyleft is a demonstration of this theory. As we have seen, practices of direct co-operation and sharing of the source code and programs were a continuous norm at the dawn of the IT revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. The commons as a method of organization of production, exchange, and circulation of knowledge pre-existed, in short, the institutionalization of the FSM. The latter did not intervene until the logic of Common had to face more and more the development of ownership strategies that marked a turning point in the dynamics of the IT revolution and Internet.

In the 1980s, as Mangolte (2013) recalls, in enterprises in this field, in fact, growing resort to IPR became popular, which the programmers, breaking with historic tradition, were obliged to integrate in their practice, whether they wanted to or not. This is a general reversal of the rules of behaviour that will progressively contaminate the universities themselves and the research centres where the Mertonian norm of publication of research results and making them available in the public domain was still in force. This break-up was particularly unpopular with the community that set itself up from 1974 around the development of the operating system Unix and in which the University of Berkeley performed, together with Bell Labs from the AT&T group, a predominant role, both for UNIX and for the management of the 5TCP/IP networks required for the development of ARPANet. Following the breaking up of the AT&T group, Bell Labs, having become an independent enterprise, developed commercial activities in IT, restricting conditions of access to the codes and increasing the cost of licenses. The conflict between the ownership strategy of Bell Labs and the University of Berkeley users lead to the disintegration of the Unix community which had been working up till then, on an international level, according to principles close to those of open source. The result has also been the multiplication of Unix owners (AIX, HP-UX, IRIX, Solaris 2, etc.). It is in this context that Stallman took the initiative, in September 1983, to promote the GNU project. The aim was to create a group of free software around an operating system compatible with free Unix, with an open-source code, accompanied by very extensive rights of use, rights that the author grants to all users (Stallman 1999). The name “GNU,” which means “Gnu’s Not Unix,” was chosen deliberately, exactly to emphasize the opposition between the philosophy of the new project and the logic that led to the break-up of the original Unix community. From this perspective, rejection of the ownership model is united to the desire to reproduce the model of sharing and horizontal co-operation of the first Unix. This is an important point as well because it shows the unjustified character of certain criticisms levelled at Stallman according to which he was a libertarian tormented exclusively by the matter of ownership, without harbouring any interest instead on the conditions of production in the software world. To dispel any doubt, we need merely remember how Stallman explains with extreme clarity that the birth of the GNU project was above all a way of escaping from “a world in which the higher and higher walls, those of different companies, would have separated the different programmers (or user-programmers), isolating them from each other” (Stallman 1999: 64). We could add that here he demonstrated extreme lucidity on the “negative externalities” that the ownership model, by its nature pyramidal and hierarchical, would have had on the development of the most effective forms of organization of cognitive labour, leading to an individualization of the wage relation and a fragmentation of labour collective. In fact, it is one of the main causes of the inefficiency of the ownership model on the matter of innovation and product quality, particularly if compared to the free-software model of horizontal co-operation. Since the beginning of the FSM, these two objectives, preservation of an open and horizontal co-operative model and the fight against the drift towards ownership of cognitive capitalism, are therefore inseparable. For this reason also, the GNU project sees its number of participants increase progressively, and, in 1985, the Free Software Foundation (FSF) was founded. Its purpose was to defend the principles of free software and to establish norms that made it possible to say clearly if a program is free or not. This was also the sense behind the creation of the GPL. In short, what before was a spontaneous form of co-operation and open-source sharing, now had to organize itself in an institutional way and at the same time formulate forms of ownership that opposed the advance of copyright and the patentability of software. The dynamics of shared production innovation of free software thus gave life to a greater legal innovation. We refer to copyleft, that is to say to the creation of a common property, of an inappropriable public domain, “to which each can add something, but not take away any part of it” for their benefit, as the legal professional Eben Moglen,adviser to the FSF, explained (quoted by Mangolte 2013: 1, our translation).

In the light of the same experience lived with the crisis of the first Unix community, Stallman and the members of the FSE were in fact aware of two key elements needed to permit the sustainability of the logic of the free-software commons. On the one hand, in a capitalist system, a simple open-source logic that limited itself to spilling knowledge and information into the public domain was unable to prevent free rider strategies of corporations. The latter can completely legally help themselves to open-source resources (like the source code) released into public domain only to then conceal them in a new product subject to copyright and/or patents. On the other hand, the accumulation of a stock of inalienable common-pool resources implies the formation of institutional forms (rules of governance, incentive norms, and forms of property) that canalize the behaviour of the commoners towards these ends. To this end, it was necessary to make use of private-property devices in some way, particularly copyright, to turn them against it and to place them at the service of a completely different logic based on the inalienability of resources. Copyleft is in fact a technique that uses the same legal instruments as copyright as a means to subvert its restrictions at the spread of knowledge.

As Stallman states, “copyleft uses copyright law, but flits it over to serve the opposite of its usual purpose: instead of means of privatizing software, it becomes a means of keeping software free” (2002: 22). In other words, in order to guarantee the sustainability of the free-software commons, the private-property devices are astutely used and subverted to create a protected public domain in which “no ‘free rider’ can any longer operate to strip the creators, which is what was permitted by the absence of rights before software with a GPL license” (Coriat 2015b). In the copyleft, the source code is in effect open and authorizes all users to help themselves to the software, to modify it, and to improve it on condition that they pass on these rights, in turn making all the applications public, freely accessible, and usable. Fundamentally, these rights are the four “fundamental freedoms” that define a free software according to the FSE: (1) the freedom to be able to use a software for every aim; (2) the freedom to be able to gain access to the functioning of a software, to adapt it for specific purposes; (3) the freedom to be able to make copies for others; and (4) the freedom to improve the software and make these improvements as open and accessible as possible for the public good.

We note that the four freedoms at the base of the free-software licences are in general completed by additional conditions meant to eliminate possible impediments for free use, distribution, and the modification of copies. They are what Ostrom (1990) would call the control measures and essential sanctions for governing a commons, like, for example, ensuring that: (1) the copyleft license cannot be revoked; (2) the labour and versions derived from it are distributed in a form that facilitates modifications (in the case of software this is equivalent to requesting both distribution of the source code and all the scripts and commands used for that operation so that the writing the programs can take place without impediments of any sort); (3) the modified labour is accompanied by a precise description to identify all the modifications made to the original work through means of user manuals, descriptions, etc.

For this capacity to closely combine forms of co-operation and alternative ownership, the free-software commons have now become one of the principal reference points of the resistance to a tragedy of the anticommons of knowledge that is spreading well beyond the world of IT.

They present themselves, at the same time, as concrete proof of the possibility to oppose this tragedy and proof of the existence of an alternative model, founded on the Common, capable of giving proof on the matter of quality and rate of innovation of a superior efficiency both to the private model and the public one.

Evidence of this lies not only in the development of the most well-known creations such as Linux, Debian, Mozilla, Guana, etc., but in the more general multiplication of small and large community projects. Besides, the interest of copyleft as a mechanism of protection of the free circulation of knowledge is proven by the extension of this model, beyond the universe of free software or open source, to a whole group of other cultural and scientific practices.

It is exactly to facilitate this process that, in 2001, Lawrence Lessig founded Creative Commons licence (CC) a non-profit-making organization. It proposes to provide all those who desire to leave their cultural content free or partially free from IPRs a way to find an alternative legal solution, through copyleft licenses inspired by the experience devised by Stallman. Apart from Wikipedia, Arduino, numerous journalistic sites or sites of governmental statistical information have registered the protection of their content under the CC license. Under this impulse, the CC license also contaminates the scientific community where a growing number of researchers reject a logic of ownership that denatures the “disinterested curiosity” of learning and prevents the sharing of information.

Nevertheless, in the case of software like in that of the scientific research, it would be simplistic drawing a clear separation between an open science, oriented at sharing and a private science subjected to access restrictions and oriented at the market. As Delfanti (2013a: 50) opportunely stresses, this is more complex and multi-faceted phenomenon. It is what is shown by, for example, the exemplary case of Craig Venter, a symbol of the new figure of a scientist businessman and privatization of research. At first, with the company Celera Genomics, he developed a profit strategy founded on the unscrupulous use of IPRs in the sequencing of the human genome. In this framework, Celera Genomics competes with the Human Genome Project co-ordinated by Francis Collins which respects a more classic logic of publication of the results on Internet. Celera Genomics and Craig Venter do not hesitate to take advantage in a logic of free riding, plundering the results made public by the Human Genome Project. It is not pointless to observe that this predatory strategy probably could not have happened if the results of the Human Genome Project had been protected by a legal formula of the copyleft type. In any case, this fact stirred up massive indignation in the international scientific community and public opinion. Also because of this (reputation is a market value), Craig Venter, in a subsequent bio-genetic project, Sorcener II, has been converted into a business model that integrates the principles of open data and open science. It is not a question of abandoning a profit logic at all but of moving from a strategy based primarily on IPR revenues to a strategy where open access to codes becomes the tool enabling him to sell the services and know-how of his business. This change in strategy is representative of a more global evolution of cognitive and information capitalism. As we will see better below, no longer restricts itself to opposing a logic of ownership to a logic of Common. It is now looking to integrate the same logic of the commons as a resource for the creation of value inside a new form of capitalism. This new form corresponds to what Andrea Fumagalli (2015) qualifies, with a striking expression, as “cognitive biocapitalism,” to indicate exactly, like all life forms, the human common in its most basic form would now be placed directly or indirectly at the service of capital exploitation.

The metamorphoses of cognitive capitalism and integration of the criticisms of the multitudes: can the spirit of Common be diluted inside a new spirit of capitalism?