Chapter 9

Instant Influence

Primitive Consent for an Automatic Age

Every day in every way, I’m getting better.

—Émile Coué

Every day in every way, I’m getting busier.

—Robert Cialdini

Back in the 1960s, a man named Joe Pyne hosted a rather remarkable TV talk show syndicated from California. The program was made distinctive by Pyne’s caustic and confrontational style with his guests—for the most part, a collection of exposure hungry entertainers, would-be celebrities, and representatives of fringe political or social organizations. The host’s abrasive approach was designed to provoke his guests into arguments, fluster them into embarrassing admissions, and make them look foolish. It was not uncommon for Pyne to introduce a visitor and launch immediately into an attack on the individual’s beliefs, talent, or appearance. Some people claimed Pyne’s acid personal style was partially caused by a leg amputation that had embittered him to life; others said, no, he was just offensive by nature.

One evening, the rock musician Frank Zappa was a guest on the show. This was at a time in the 1960s when very long hair on men was still unusual and controversial. As soon as Zappa had been introduced and seated, the following exchange occurred:

Pyne: I guess your long hair makes you a girl.

Zappa: I guess your wooden leg makes you a table.

Primitive Automaticity

Aside from containing what may be my favorite ad-lib, the dialogue between Pyne and Zappa illustrates a fundamental theme of this book: often when we make a decision about someone or something, we don’t use all of the relevant available information. We use only a single, highly representative piece of the total. An isolated piece of information, even though it normally counsels correctly, can lead to clearly stupid mistakes—mistakes that, when exploited by clever others, leave us looking silly or worse.

At the same time, a complicating companion theme has been present: despite the susceptibility to stupid decisions that accompanies reliance on a single feature of the available data, the pace of modern life demands that we frequently use this shortcut. Recall early in chapter 1 when we compared the shortcut to the automatic responding of lower animals, whose elaborate behavior patterns could be triggered by the presence of a lone stimulus feature—a cheep-cheep sound, a shade of redbreast feather, or a specific sequence of light flashes. The reason lower animals must rely on such solitary stimulus features is their restricted mental capacity. Their small brains cannot begin to register and process all the relevant information in their environments. So these species have evolved special sensitivities to certain aspects of the information. Because those selected aspects of information are normally enough to cue a correct response, the system is usually efficient: for example, whenever a mother turkey hears cheep-cheep, click, run, out rolls the proper maternal behavior in a mechanical fashion that conserves much of her limited brainpower for dealing with other situations and choices she must face.

We, of course, have vastly more effective brain mechanisms than do mother turkeys or any other animal group. We are unchallenged in our ability to take into account a multitude of relevant facts and, consequently, make good decisions. Indeed, it is this information-processing advantage over other species that has helped make us the dominant form of life on the planet.

Still, we have our capacity limitations, too; and, for the sake of efficiency, we must sometimes retreat from the time-consuming, sophisticated, fully informed brand of decision-making to a more automatic, primitive, single-feature type of responding. For instance, in deciding whether to say yes or no to a requester, we frequently pay attention to a single unit of the relevant information in the situation. In preceding chapters, we’ve explored several of the most popular of the single units of information we use to prompt our compliance decisions. They are the most popular prompts precisely because they are the most reliable ones—those that normally point us toward a correct choice. That’s why we employ the factors of reciprocation, liking, social proof, authority, scarcity, commitment and consistency, and unity so often and so automatically in making our compliance decisions. Each, by itself, provides a highly reliable cue as to when we will be better off saying yes instead of no.

We are likely to use these lone cues when we don’t have the inclination, time, energy, or cognitive resources to undertake a complete analysis of the situation. When rushed, stressed, uncertain, indifferent, distracted, or fatigued, we focus on less of the available information. Under these circumstances, we often revert to the rather primitive but necessary “single piece of good evidence” approach to decision-making. All this leads to an unnerving insight: with the sophisticated mental apparatus we have used to build world eminence as a species, we have created an environment so complex, fast-paced, and information-laden that we must increasingly deal with it in the fashion of the animals we long ago transcended.

Modern Automaticity

John Stuart Mill, the British economist, political thinker, and philosopher of science, died a century and a half ago. The year of his death (1873) is important because he is reputed to have been the last man to know everything there was to know in the world. Today, the notion that one of us could be aware of all known facts is laughable. After eons of slow accumulation, human knowledge has snowballed into an era of momentum-fed, multiplicative, monstrous expansion. We now live in a world where most of the information is less than fifteen years old. In certain fields of science alone (physics, for example), knowledge is said to double every eight years. The scientific-information explosion is not limited to such arcane arenas as molecular chemistry or quantum physics but extends to everyday areas of knowledge, where we strive to keep ourselves current—health, education, nutrition. What’s more, this rapid growth is likely to continue because researchers are pumping their newest findings into an estimated two million scientific-journal articles per year.

Apart from the streaking advance of science, things are quickly changing closer to home. According to yearly Gallup polls, the issues rated as most important on the public agenda are becoming more diverse and surviving on that agenda for a shorter time. In addition, we travel more and faster; we relocate more frequently to new residences, which are built and torn down more quickly; we contact more people and have shorter relationships with them; in the supermarket, car showroom, and shopping mall, we are faced with an array of choices among styles, products, and technological devices unheard of last year that may well be obsolete or forgotten by the next. Novelty, transience, diversity, and acceleration are prime descriptors of civilized existence.

This avalanche of information and choice is made possible by burgeoning technological progress. Leading the way are developments in our ability to collect, store, retrieve, and communicate information. At first, the fruits of such advances were limited to large organizations—government agencies or powerful corporations. With further developments in telecommunications and digital technology, access to such staggering amounts of information is within the reach of individuals. Extensive wireless and satellite systems provide routes for the information into the average home and hand. The informational power of a single cell phone exceeds that of entire universities of only a few years ago.

But notice something telling: our modern era, often termed the Information Age, has never been called the Knowledge Age. Information does not translate directly into knowledge. It must first be processed—accessed, absorbed, comprehended, integrated, and retained.

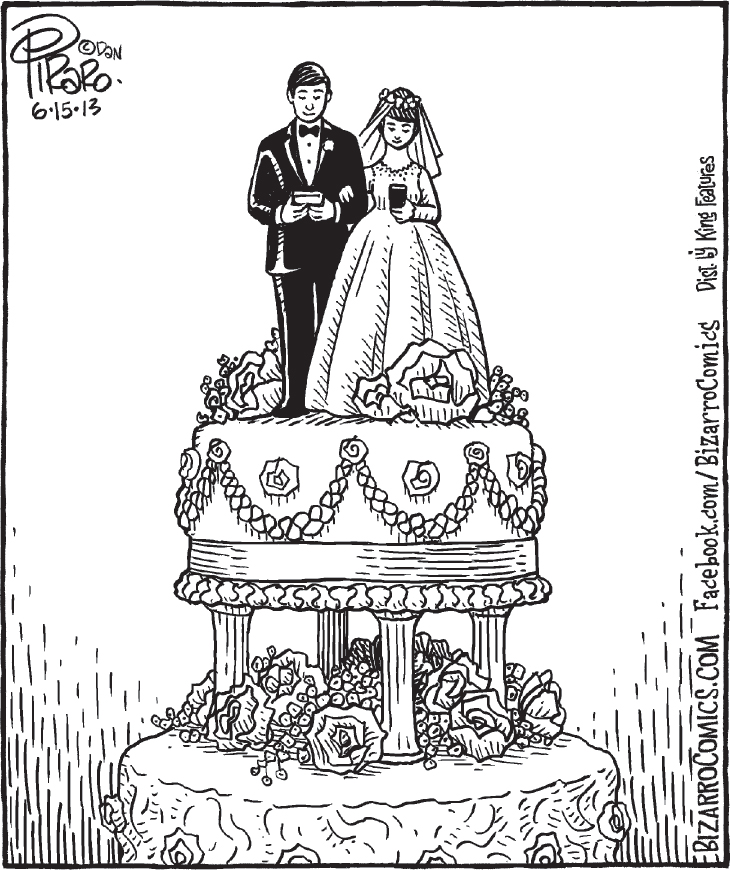

EBOX 9.1

Do You Take This Phone? I Do . . . Everywhere.

Author’s note: Not only is the informational power of our digital devices unprecedented, but it can be addicting (Foerster et al., 2015; Yu & Sussman, 2020). Surveys show that people check their phones on average over one hundred times a day, and 84 percent say they “couldn’t go a single day without their mobile devices.”

BIZZAROCOMICS.COM Facebook.com/BizarroComics Distributed by King Features

Shortcuts Shall Be Sacred

Because technology can evolve much faster than we can, our natural capacity to process information is likely to be increasingly inadequate to handle the abundance of change, choice, and challenge that is characteristic of modern life. More and more frequently, we find ourselves in the position of lower animals—with a mental apparatus unequipped to deal thoroughly with the intricacy and richness of the external environment. Unlike the lower animals, whose cognitive powers have always been relatively deficient, we have created our own deficiency by constructing a radically more complex world. The consequence is the same as that of the animals’ long-standing one: when making a decision, we will less frequently engage in a fully considered analysis of the total situation. In response to this “paralysis of analysis,” we revert increasingly to focusing on a single, usually reliable feature of the situation.1

When those single features are truly reliable, there is nothing inherently wrong with the shortcut approach of narrowed attention and automatic responding to a particular piece of information. The problem comes when something causes the normally trustworthy cues to counsel us poorly, to lead us to erroneous actions and wrongheaded decisions. As we have seen, one such cause is the trickery of certain compliance practitioners, who seek to profit from the mindless and mechanical nature of shortcut responding. If, as it seems, the frequency of shortcut responding is increasing with the pace and form of modern life, we can be sure that the frequency of this trickery is destined to increase as well.

What can we do about the intensified attack on our system of shortcuts? More than evasive action, I urge forceful counterassault; however, there is an important qualification. Compliance professionals who play fairly by the rules of shortcut responding are not to be considered our adversaries; to the contrary, they are our allies in an efficient and adaptive process of exchange. The proper targets for counter-aggression are only those who falsify, counterfeit, or misrepresent the evidence that naturally cues our shortcut responses.

Let’s take an illustration from what is perhaps our most frequently used shortcut. According to the principle of social proof, we often decide to do what other people like us are doing. It makes all kinds of sense because, most of the time, an action that is popular in a given situation is also functional and appropriate. Thus, an advertiser who, without using deceptive statistics, provides information that a brand of toothpaste is the largest selling has offered us valuable evidence about the quality of the product and the probability that we will like it. Provided we are in the market for a tube of good toothpaste, we may want to rely on that single piece of information to try it. The strategy will likely steer us right, unlikely steer us far wrong, and conserve our cognitive energies for dealing with the rest of our increasingly information-laden, decision-overloaded environment. The advertiser who allows us to use effectively this efficient strategy is hardly our antagonist but, rather, our cooperating partner.

The story becomes quite different, however, when a compliance practitioner tries to stimulate a shortcut response by giving us a fraudulent signal for it. Our nemesis is the advertiser who seeks to create an image of popularity for a brand of toothpaste by, say, constructing a series of staged “unrehearsed interview” ads in which actors posing as ordinary citizens praise the product. Here, where the evidence is counterfeit, we, the principle of social proof, and our shortcut response to it, are all being exploited. In an earlier chapter, I recommended against the purchase of any product featured in a faked “unrehearsed interview” ad and urged that we send the product manufacturers letters detailing the reason and suggesting they dismiss their advertising agency. I also recommended extending this aggressive stance to any situation in which an influence professional abuses the principle of social proof (or any other principle of influence) in this manner. We should refuse to watch TV programs that use canned laughter. If, after waiting in line outside a nightclub, we discover from the amount of available space that the wait was designed to impress passersby with false evidence of the club’s popularity, we should leave immediately and announce our reason to those still in line. We should boycott brands found to be planting phony reviews on product-rating sites—and spread the word on social media. In short, we should be willing to use shame, threat, confrontation, censure, tirade, nearly anything, to retaliate.

I don’t consider myself pugnacious by nature, but I actively advocate such belligerent actions because in a way I am at war with the exploiters. We all are. It is important to recognize, however, that their motive for profit is not the cause for hostilities; that motive, after all, is something we each share to an extent. The real treachery, and what we cannot tolerate, is any attempt to make their profit in a way that threatens the reliability of our shortcuts. The blitz of modern daily life demands that we have faithful shortcuts, sound rules of thumb in order to handle it all. These are no longer luxuries; they are out-and-out necessities that figure to become increasingly vital as the pulse quickens. That is why we should want to retaliate whenever we see someone betraying one of our rules of thumb for profit. We want that rule to be as effective as possible. To the degree its fitness for duty is regularly undercut by the tricks of a profiteer, we naturally will use it less and will be less able to cope efficiently with the decisional burdens of our day. That we cannot allow without a fight. The stakes are far too high.

READER’S REPORT 9.1

From Robert, a social-influence researcher in Arizona

A while ago I was in an electronics store to buy something else when I noticed a high quality big screen TV on sale at an attractive price. I wasn’t in the market for a new TV, but the combination of the sale price and its strong product rating got me to stop and examine some related brochures. A salesman, Brad, came up and said, “I can see you’re interested in this set. I can see why. It’s a great deal at this price. But, I have to tell you it’s our last one.” That spiked my interest immediately. Then he told me he had just gotten a call from a woman who said she might come in that afternoon to purchase it. I’ve been a persuasion researcher all my professional life; so I knew he was using the scarcity principle on me.

It didn’t matter. Twenty minutes later, I was wheeling out of the store with the “prize” I had obtained in my cart. Tell me, doc, was I a fool to react the way I did to Brad’s scarcity story?

Author’s note: As readers should by now recognize, the Robert in the report was me, which gives me an especially informed perspective on his question. Whether he should feel duped by the appeal depends on whether Brad accurately informed him about the scarcity-related features of the situation. If so, Robert should feel grateful to Brad for the gift of that information. For instance, imagine if Brad hadn’t informed Robert of the genuine circumstances, Robert went home to think things over and returned that evening to make the purchase—only to learn the last set had been sold. He would have been furious at the salesman: “What?! Why didn’t you tell me it was the last one before I left? What’s wrong with you?”

Now, suppose instead of providing honest information, Brad fabricated the scarcity-related conditions surrounding the TV. Then, once Robert was gone, he went to the back room, got another of the same model and put it on the shelf, where he could sell it to the next customer using the same story. (By the way, Best Buy employees were caught doing exactly this a few years ago.) No longer would he be a valuable informant to Robert; he’d be a damnable profiteer.

Which was it? Robert was determined to find out. He returned to the store the next morning to see if there was another such TV on display. There was not. Brad had been straight with him—which spurred Robert to go to his office and write a highly favorable review of the store and, especially, of Brad. Had Brad lied, the review would have been an equally strong condemnation. When exposed to the principles of influence, we should unfailingly promote those who seek to arm us and demote those who seek to harm us with them.

SUMMARY

- Modern life is different from that of any earlier time. Owing to remarkable technological advances, information is burgeoning, alternatives are multiplying, and knowledge is exploding. In this avalanche of change and choice, we have had to adjust. One fundamental adjustment has come in the way we make decisions. Although we all wish to make the most thoughtful, fully considered decision possible in any situation, the changing form and accelerating pace of modern life frequently deprive us of the proper conditions for such a careful analysis of all the relevant pros and cons. More and more, we are forced to resort to another decision-making approach—a shortcut approach in which the decision to comply (or agree or believe or buy) is made on the basis of a single, usually reliable piece of information. The most reliable and, therefore, most popular such single triggers for compliance are those described throughout this book. They are commitments, opportunities for reciprocation, the compliant behavior of similar others, feelings of liking or unity, authority directives, and scarcity information.

- Because of the increasing tendency for cognitive overload in our society, the prevalence of shortcut decision-making is likely to increase proportionately. Compliance professionals who infuse their requests with one or another of the levers of influence are more likely to be successful. The use of these levers by practitioners is not necessarily exploitative. It only becomes so when the lever is not a natural feature of the situation but is fabricated by the practitioner. In order to retain the beneficial character of shortcut response, it is important to oppose such fabrication by all appropriate means.