I told my partner, Brian, at around four a.m. that I was starting labor. We snuggled in bed, and he put on one of my favorite movies. I held on to him tightly through my contractions, which were not that close together yet. I called Melissa, my nearest and dearest friend, who lives three hours away. She was one of my labor support team. She would head down right away to help me through this.

The latent phase of labor may feel much the same to you as prelabor, but during this time your cervix will open up (dilate) to 4 to 5 centimeters and will usually completely thin out (efface). Labor contractions will be short and spaced relatively far apart (from five to twenty minutes apart). During the latent phase, your contractions will become longer, more painful, and more regular. This is not yet the time to go to a hospital or birthing center. However, most women at this stage want some kind of care, such as the reassuring presence of a partner or close friend or a care provider or other guide familiar with birth. Some women say that this phase of labor is the hardest psychologically. One midwife explains:

It’s like starting a hike and no one is telling you how long it is. The trail has lots of meandering switchbacks and hills, and you don’t know where you’re headed or how long it will take to get there, but you just keep going. Later, it may get physically more difficult, but at least then you can see the end in sight, the peak of the mountain, and you can push on.

Sometimes contractions build up gradually, starting with any of the signs mentioned above, with menstrual-like cramps evolving into stronger contractions that grow closer together over a long period of time, sometimes even over a period of days. At the other extreme, labor can begin abruptly, with strong regular contractions no more than five minutes apart, causing you to stop everything you are doing and concentrate.

Everyone responds differently to early labor. Walking, showering, taking long baths, or cuddling with loved ones can relax you and help labor progress. These early hours may be sweet as you lie with your partner or sit alone, the baby still within you in the quiet of your home. It is important that you continue to eat nourishing foods to prepare you for the work ahead. And sleep is critical for much the same reason, particularly with a first baby, for which labor may be longer. Some women feel too excited or apprehensive to sleep. Try to save your energy for active labor. Don’t worry if contractions slow down when you lie down to rest; it’s still early. If you truly don’t feel up for rest, spending time with friends and family can be a nice distraction, but check in with yourself frequently and consider whether you would rather be resting. If you begin to feel like a “watched pot,” ask for some time alone.

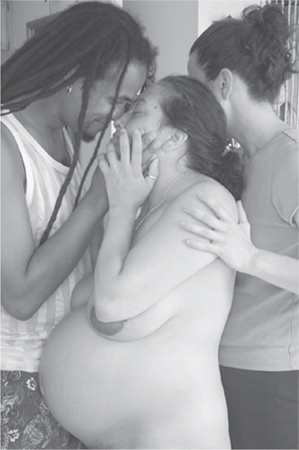

© Jada Shapiro, Birth Day Presence

When we went for a walk, we ran into friends. “What are you doing up? I thought you were in labor.” It was fun changing people’s image of a woman in labor.

For many first-time mothers, it can take a day or more to get to about 4 centimeters dilation, which signals entry into the active phase of labor. When you feel painful, wavelike, regular, rhythmic contractions that last forty-five to sixty seconds and that are so intense you can’t talk or walk while you are having one, you are likely in active labor. The contractions may begin in your back, you may feel them only in the front, or you may feel them in both the back and front. Your uterus feels hard to the touch.

Though you may have heard that labor will get more and more painful as it progresses, this is not necessarily true. Some women say the active phase of labor was the most painful, some say the transition phase, and others say pushing was the most painful. In general, women feel the most pain during periods when the cervix is dilating fast or when the baby is descending quickly. These events can happen at different phases of labor for different women.

I spent most of the night laboring alone in the dark, like a cat. It was marvelous. Not easy—it’s hard work; that’s why it’s called LABOR. It was intense. Not painful—I can’t call it painful. But it’s . . . inevitable. Inescapable. Uncontrollable. You can’t get away. I kept thinking of that kids’ game “Going on a bear hunt”: “Can’t go over it, can’t go around it, have to go through it!”

This is the time to gather your support people, to call your provider if you are having a home birth, or to prepare to go to the birth center or hospital. If you are not sure if you are in active labor yet, your care provider can help you know for sure. A careful phone consultation, a home visit, or a visit at the office can help determine your progression. Staying home or in another familiar, comfortable setting until active labor is well established is an important strategy for reducing your chance of interventions. Studies show that being admitted to a hospital in early labor increases the chances of having medications to speed up your labor or a cesarean section.5 Travel can be an uncomfortable challenge during active labor, but you can regain your rhythm once you are settled in your chosen birth setting.

Progress in the active phase of labor, both for first-time mothers and for women who have given birth before, is widely variable. In many hospital birth settings, expectations for labor progress are based on outdated studies that showed average dilation rates in women with medically managed labors (known as the “Friedman curve”) or driven by financial incentives to get labor done more quickly and make room for the next patient to be admitted. The traditions of natural or expectant management and current evidence show that normal labor can be significantly longer than previous studies suggested, and “plateaus”—when the woman’s cervix doesn’t actively dilate for several hours—are common.6 As long as the mother and baby are doing well, labor should be allowed to progress on its own.

One woman describes her experience of getting “stuck” temporarily at a certain point in active labor:

I got stuck at about 8 to 9 centimeters for a really long time. I wasn’t aware how long, except that it was hours. [The doctor] who was on call suggested Pitocin to speed things up, but I refused. Part of my concern was that the contractions were already so intense that I felt if they were stronger and closer together I wouldn’t be able to cope, and I did not want to do anything that put me at risk for a C-section …

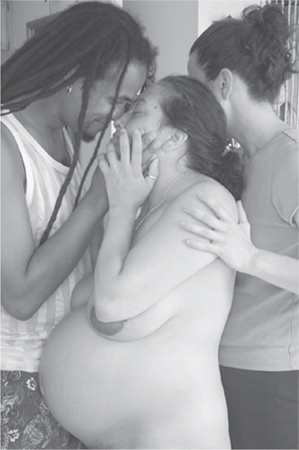

© Elana Hayasaka

Cervical dilation shown in actual size (in centimeters). When you reach about 10 centimeters, you will be ready to push.

… In the end, I realized that though it was hard, it was never more than I could take, and I had been prepared to keep pushing for even longer if necessary. I had not reached the end of my strength. We never would have been able to do it without our doula’s help—she was worth her weight in gold.

The last few centimeters from 8 cm to complete dilation (about 10 cm) can be the hardest, most intense phase of labor, but it is also usually the shortest. In first pregnancies, this period generally lasts no more than a couple of hours. The transition is when many women get discouraged and feel that they have hit a wall and can’t go on. Excellent labor support from a loved one or doula can help you discover deep wells of strength to finish birthing. If you experience challenges at this time, keep in mind that this is the home stretch. Your body has already accomplished most of the difficult work. Do whatever makes you feel more comfortable and helps you handle the intensity of labor. When transition is over, you will be pushing your baby out. One woman recalls how she shed her usual inhibitions during transition:

The hospital’s birthing pavilion was like a good hotel. But I didn’t get to kick back with a book and some room service. All through the night, I heaved around on the floor in a variety of positions—on my side Jane Fonda aerobics style, on all fours with ass and yoni to the wind, on the floor, and then up on the bed. I was desperate for comfort, relief and a baby in my arms.

Shift changes were going on, and people were coming and going. It was like Grand Central Station. . . . They asked me if I minded having a nursing student watch the birth. By this time, I didn’t care if the security guard from the parking lot brought in popcorn and Raisinettes to watch the event.

Another woman says:

The peak of each contraction was such that I needed to close my eyes and really concentrate on the number of deep breaths I was taking, knowing that at the count of five or eight, depending on the length of the sensation, it would start to ease up. There’s a sureness in numbers—the logic overwhelmed the raw wildness of the sensation. I knew time was my only ally in dealing with the pain. With time each contraction would be over, with time the baby would be born.

Labor and birth are intense and unpredictable, and can push us to places within ourselves that we’ve never been. Many of us fear the pain and wonder how we will manage.

Fortunately, many techniques are available to ease and help manage pain. These techniques range from comfort measures such as walking, touch, and submersion in water to mental strategies such as focused breathing and hypnosis to medications such as opioids and epidurals.

In everyday life, physical pain, especially intense pain, is usually a warning that something is wrong in our bodies. But the pain of labor is not a sign of danger, nor is it a symptom of injury or illness. It is a sign that your body is working hard to birth your baby.

Labor pain is different in many ways from other kinds of pain. For one, the pain is self-limiting—it will end when the baby is born. It is also intermittent, not continuous, which means you will usually have periods of no pain between contractions. In addition, labor sensations intensify gradually over time, and this allows your body time to adapt. These differences often make labor pain easier to cope with than other kinds of pain.

Because pain and suffering often go hand in hand, we tend to think they’re the same thing. But they’re not. Pain is a physical sensation, while suffering is an emotional experience. We may suffer (feel helplessness, anguish, remorse, fear, panic, or loss of control) even when there is no physical sensation of pain. And we may experience physical pain without suffering. As Penny Simkin and April Bolding, longtime advocates for birthing women, write, “One can have pain coexisting with satisfaction, enjoyment, and empowerment.”13 By the same token, they say, suffering can be caused or increased by factors other than physical pain: “Loneliness, ignorance, unkind or insensitive treatment during labor, along with unresolved past psychological or physical distress, increase the chance that the woman will suffer.”

While it is commonly believed that a woman’s satisfaction with her birth experience is linked to how much or how little pain she feels, this isn’t typically so. Our satisfaction seems to be highest when we trust that we are getting good information, we are given opportunities to participate in decisions regarding our care, and our caregivers treat us with kindness and respect.14 Pain and pain relief seem to have less effect on our overall satisfaction than the quality of support we receive from our caregivers.

My labor felt like a marathon that lasted over two days. There were easy periods, where I sailed along (I was even able to sleep), but there were stretches when it felt like a steep, uphill climb that would never end. But just like in a marathon, you just keep putting one foot in front of the other. You don’t think about reaching the end, you just think about taking the next step. Having the support of a great midwife, my husband, and a few close loved ones made all the difference. I had such a HUGE sense of accomplishment when my daughter emerged and made her first tiny sounds. I was exhilarated by meeting such a great physical (and mental) challenge and felt I had earned a marathon “crown.”

Certain strategies lay the foundation to help you cope with the pain of labor. These include working with a provider you trust; knowing ahead of time what pain relief strategies are available in your chosen birth setting and maximizing your range of safe options; and giving birth in a safe, comfortable space, surrounded by people who will provide you with good support.

Most women labor best in a calm, nurturing environment. For instance, having privacy, dim lights, quiet voices, and/or music of your choosing can contribute to your sense of ease and safety.

Some of the strategies listed below can help reduce pain, while others can help you cope better with it. Women’s responses to these techniques vary; you may find that some techniques are helpful while others are not. Your support team can help you try different strategies and see what works. An experienced nurse, midwife, or doula will have suggestions for specific techniques to assist you. In some cases, there is little scientific evidence that a particular strategy is helpful, but it is included as some women find it comforting and it poses no risks.

Having the freedom to move and change positions makes labor more manageable for many women. Upright movements, such as walking, swaying, lunging, moving on a birthing ball, and dancing, can help reduce discomfort and help move the baby down into a good position for birth.15 As labor progresses, you may find yourself staying in one place or gravitating to a bed, but you are unlikely to want to lie on your back. Upright positions may be more comfortable and may open your pelvis to help the baby descend. Being on your hands and knees can help relieve back pain. Lying on your side helps you rest your legs and may help the baby to rotate into a good position for birth.

In active labor, you turn inward, and you develop a rhythm that takes you through each contraction and rest period. You may rock back and forth, moan, curl around a partner’s hand during each contraction, and then want massage or total silence in between. The pattern that works for you will be uniquely yours. While the woman is in this zone, she can benefit when her support team reinforces her rhythm/ritual and keeps interruptions to a minimum.

The two things that helped me through the labor were mooing and yelling at the top of my lungs. Mooing was the only sort of deep moaning noise that made my whole body feel good, but it did not fit into my mental picture of myself as a chic, polite woman, so I kept making myself laugh. I would do these big low bellows and then burst out laughing because I was so embarrassed, but then that felt really good, so I would just keep laughing.

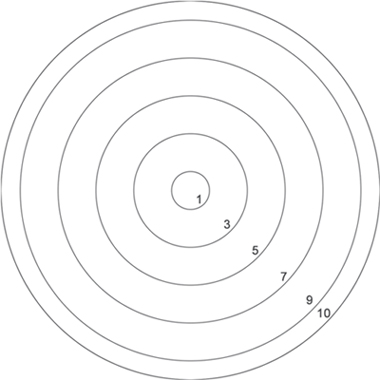

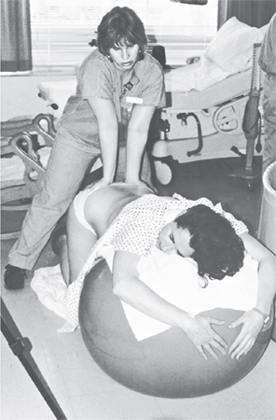

© Judith Elaine Halek / Birth Balance

Many hospitals may restrict your movement, especially if you are alone, so try to have a support person with you and try to maintain your freedom to move during your labor. If you are encumbered with multiple attachments such as blood pressure cuffs, IVs, a bladder catheter, and electronic fetal monitoring equipment, it may be impossible to move freely. You have a right to refuse all these monitors. If you do accept them, you can adapt by standing by your bed, sitting in a chair, swaying in your partner’s arms, and so forth. If you have an epidural or have taken medicines that can make you feel dizzy, you will likely be restricted to bed.

© Judith Elaine Halek / Birth Balance

Being in water during labor can be wonderfully soothing and can help you relax. Many studies have shown water immersion during labor to be safe for both mother and baby while also reducing the mother’s pain and her need for pain medication. Women who bathe or shower during labor have high satisfaction with this method.

When using a tub, work with your midwife or physician to determine when and for how long you can be in the bath, so that you can avoid any negative effects. If a woman enters the bath before she is in active labor or stays in for more than one or two hours, labor progress can be slowed.16 Drink plenty of fluids, and keep the tub water at body temperature to avoid getting dehydrated or overheated.

If a tub is not available, showers are also a good option during labor. Standing and swaying under the water or holding an extended showerhead and letting the water run over your belly can be very helpful.

Focusing on your breath, a calming and centering technique used in meditation and yoga, may help in labor as well. Classic strategies include a deep, sighing breath at the beginning and end of each contraction to release tension. During contractions, you can pay attention to your breath, letting it anchor you to the moment as your contraction begins. Or breathe along with the contraction, matching your breathing to the rise and fall of the contraction as it becomes stronger, peaks, and subsides. Repeating affirmations may also be helpful. Focusing on exhaling slowly between contractions as you relax muscles and get rid of tension can help as well.

The use of hypnosis in labor has undergone a recent renaissance. Self-hypnosis involves practicing techniques before labor begins that you can use to help trigger deep relaxation when the contractions start. You can practice these on your own or with a partner. Several kinds of prenatal classes are available to learn hypnosis for birthing.

The human touch is a powerful way to relieve pain and reduce anxiety in labor.17 Touch may range from a supportive hand placed for reassurance in one spot, such as on your arm, to light stroking on your back and arms as you have a contraction to a firm massage on your neck and shoulders between contractions. Counter-pressure is using a special kind of touch to help relieve back pain in labor. Someone places the palms of her or his hands over your lower back where the sacrum (the triangular area at the base of the spine) is and then firmly presses in and supports your back during a contraction, holding it until the contraction is over. Another technique is squeezing in on both hips, which places pressure on the outside of your pelvic bones.

In the midst of the wildness of transition, as I was on hands and knees throwing up into a bowl, my midwife placed her hand right at the small of my back. After giving birth, I couldn’t conjure up in my mind what a contraction felt like, but I will always remember just how that touch felt.

At times during labor, an ice pack on your lower back or a warm compress on your abdomen or back may be just the right thing. (Wrap an ice pack so that the ice is never directly in contact with your skin, and a warm compress should never be too hot to hold comfortably in the hand.) At other times, a cold washcloth on your forehead or on the back of your neck may feel perfect. The changing sensations can sometimes distract you from labor pain.

When I was home-birthing my baby daughter, my four-year-old son, Alex, held an ice-cold wet washcloth to my forehead during the most intense part of my labor. It was extremely soothing and also allowed me to direct my focus to a single place without distraction. It was definitely one of the best tools for birthing comfortably and calmly. Not to mention, it was a wonderful way for my son to participate in the birth of his sister!

Pain medications can be extremely helpful at certain times and in certain situations in labor. They can dramatically ease the pain of labor and can be vital in managing complicated or difficult labors. Yet, like most medical interventions, they have some risks for mothers and babies and should be used only with full knowledge of all options and alternatives as well as of the risks and benefits. Medications do not take the place of emotional support and encouragement, which are essential regardless of whether you are using medication or not. These medications are not available at outside-of-hospital births; if you are giving birth at home or in a freestanding birth clinic, you will have to transfer to a hospital if at some point you need or want them.

There are two basic ways that pain medications are used during labor: systemically, that is, affecting the entire body, and regionally, affecting a targeted area. The systemic medications are usually opioids (also known as narcotics), but they also include nitrous oxide. (See box.) Epidurals use a mixture of local anesthetic (numbing medicine) and usually add an opioid.

Opioids (also called narcotics) are the most commonly used systemic medicines given to relieve pain during labor. They include morphine (usually used only in early labor to help women get some sleep when this stage of labor is long), meperidine (Demerol or Pethidine), nalbuphine (Nubain), butorphanol (Stadol), and fentanyl (Sublimaze). Specific medicines used vary by provider and location.

When used systemically, opioids are given through an intravenous line (IV) or by an injection into your arm, leg, or buttock. They work by being absorbed into the bloodstream and going to the receptors in your body that diminish pain perception. In general, they make you feel relaxed, sleepy, and possibly a little dizzy, and you tend to feel your contractions less. They may make it easier for you to rest for longer periods of time between the contractions.

Each opioid works for only a limited length of time and can be safely given only at certain times during labor. After a peak of effectiveness, the medicine begins to wear off. The length of time varies from one medicine to another. One to two hours is common, with the peak often being less than half an hour after the medicine is given.

One advantage of systemic medicines is that they are short-acting. They therefore can be used at a time in the labor when you just need some help to make it through a challenge. The use of morphine for women who are exhausted in early labor is one example. Another common example is a onetime dose of systemic medicine if you are in the middle of labor and feel exhausted or like giving up; it may be what you need to get through this short but tough time. Mothers who try this may get a second wind and do fine without further medication. Others may have an even harder time coping with labor because of the way the medication makes them feel (“high” or disoriented). Another advantage of using systemic medicine over regional medicine such as an epidural is that you can either avoid the possible adverse effects of the epidural altogether or delay getting the epidural until later in the labor, which may diminish the impact of some of the epidural’s negative effects.

The main disadvantage of systemic opioids (narcotics) is that their use in labor has generally been found to have limited effect on controlling women’s pain. When women rate the effectiveness of all the techniques used to minimize pain during labor, systemic opioids are less effective than immersion in water.20 They are also much less effective for pain relief than epidurals. They will not take the pain away completely. The medicine may “knock you out” between contractions, or it may “take the edge off” by decreasing the intensity of the contraction at its strongest. Some women experience a welcome feeling of relaxation; others feel a bit out of control.

Other disadvantages of opioids are:

• The use of these medicines may decrease the production of your own endorphins (hormones that reduce your perception of pain).

• They are short-acting, and there is a time limit for when you can get another dose. So after you have been given one dose, there is usually a waiting period before you can have more if the first dose doesn’t work as well as you want. Some women find this waiting period very difficult.

• Just as they circulate throughout your body, systemic medicines get into the baby’s circulation. There, they have the same effect on the baby that they do on you. If a baby is born too soon after this type of drug is given to the mother, she or he may need help to breathe or may have to be given medication to wake up. For this reason, many care providers will not give systemic pain medication if birth is likely to occur soon.

• Babies of mothers who receive these medicines can also have trouble initiating breast-feeding successfully and may not be able to suck correctly during the first few hours or days of life.21

Epidurals and spinals cause numbness below the level of the back at which they are placed. In an epidural, medicine is infused just outside the outermost of the two membranes covering the spinal cord (the epidural space); in a spinal, the medicine is injected between the two membranes. Either epidurals or combined spinal-epidurals are offered for labor pain. These methods may involve the use of local anesthesia, which works by taking away sensation through a numbing effect on nerves. Or it may involve opioid medications only or a combination of local anesthesia and opioid medications.

To place an epidural or spinal, an anesthesiologist or nurse-anesthetist first numbs a small area of skin on your back. For an epidural, she or he uses a needle to place a catheter (a tiny, flexible plastic tube) into the epidural space. With the catheter in place, an anesthetic, or more usually a combination of anesthetic and opioid, can be infused through a pump that controls the dose and the rate throughout your labor. In patient-controlled epidural anesthesia, you have access to a button that activates the pump. (It has controls that won’t allow you to overdose yourself.)

A spinal is a single injection usually used for short-term pain relief in situations when pain control is needed faster. A spinal uses local anesthetic and sometimes an opioid that is injected into the spinal fluid that surrounds the spinal cord. Loss of feeling below the site of injection occurs quite quickly. Spinals are often used for cesarean surgery and sometimes for forceps or vacuum extraction deliveries.

Some hospitals offer a combined spinal-epidural: a onetime dose of opioid or anesthetic is injected into the woman’s spinal fluid, and then a catheter is left in place in the epidural space for use when the spinal medicine wears off. The advantage of the combined spinal-epidural is that the spinal component offers relief without numbing, and if relief wears off before the birth, the anesthesia staff can add anesthetics to the epidural catheter and avoid a second procedure.

An epidural or a spinal will be accompanied by continuous electronic fetal monitoring of the baby. In addition, women who have an epidural or spinal will have an IV and equipment to monitor blood pressure. Most women will need a temporary urinary catheter to empty the bladder and will be confined to bed, because this type of medication also affects the nerves that control the hip and leg muscles.

The greatest advantage of epidurals (and spinals) is that they can take away the greater part of the pain in labor and while giving birth for most women who use them. An epidural can provide much-needed rest for an exhausted mother, especially when other approaches have failed. An epidural can be helpful in the case of a very long labor. Psychological issues or individual circumstances may make experiencing the physical sensations of labor too difficult for some mothers at some point. Finally, some women choose epidurals simply to eliminate all labor pain.

However, regional analgesia can change the course of labor in many adverse ways. The disadvantages of regional medications used for labor pain include:22

• Sometimes the insertion of the epidural is ineffective, and the process has to be repeated. Epidurals sometimes fail to work or fail to relieve pain in a small area of your abdomen or back (also known as an epidural window). Such areas sometimes can be anesthetized with higher doses of medication but some women never do get complete pain relief.

• You are more likely to have a short episode of low blood pressure right after the epidural or spinal is injected, which may be associated with a drop in the baby’s heart rate. If this happens, your providers will increase fluids through the IV, help you change position, or administer medicine to raise your blood pressure. If the drop in the baby’s heart rate lasts for more than a few minutes, your provider will likely give you oxygen and may place an internal monitor (which involves breaking your membranes, if they are not already broken) to better track the baby’s response. These episodes of low blood pressure usually resolve quickly and do not cause any lasting effect on you or the baby.

• Spinal and epidural opioids can cause itching. This is generally mild but can be quite bothersome for some women.

• This type of medication can increase the amount of time that you are in labor, including a longer pushing phase.

• You may be more likely to receive Pitocin, a synthetic form of the hormone oxytocin, to make your contractions stronger. (See “Medical Approaches to Speeding Up Labor.”)

• The longer you have an epidural, the more likely you are to develop a fever during labor. Because your providers cannot know if a fever is from an infection or from the epidural, if you get a significant fever in labor, your providers will start antibiotics and your baby may be separated from you and subjected to more tests in the first hours after birth.

• You are more likely to have forceps or vacuum delivery. Instrumental vaginal deliveries are more likely to lead to tears into or through the anal sphincter muscle.

• Between one and two of every one hundred women who get an epidural, and fewer than one of every one hundred women who receive a labor spinal, get a severe headache called a spinal headache. The headache usually doesn’t start until the next day; if it occurs, effective treatment is available.

Evidence is mixed on whether there is an association between epidurals and problems in establishing breastfeeding; such problems seem more likely to be linked to epidurals that include high-dose opioids in the mixture.23

The active phase of labor is complete when your cervix is open wide enough to accommodate the baby’s head (about 10 cm, or 4 inches) or there is full or complete dilation. Around this time, you will likely feel a strong urge to begin pushing your baby out the final few inches. Often, after transition and just before you feel like pushing or bearing down, your contractions may space out or even stop for a while, allowing you to rest.

The contractions were coming hard, [but] I could actually sleep between them. It was all very surreal and otherworldly. Immense pain and then total relaxation. I felt like I was in a scene from The Red Tent [a novel set in biblical times; the title refers to a tent in which women gave birth]. I pushed from somewhere buried inside me. Deep, guttural, almost animal-like noises came from within me. Loud noises. Noises I soon had no control over. My body was pushing out my baby, and I was merely providing the sound track.

More rapid, intense contractions, a powerful opening-up feeling, and rectal pressure (a sense that you need to have a bowel movement) are signs that you are completely dilated and ready to push your baby down through your vagina and give birth. Pushing can be a great relief because it requires you to become an active participant, in contrast to the yielding and letting go necessary for active labor.

After a few pushes, I somehow realized that I had to change gears. Pushing was up to me. I wasn’t supposed to lie there and cope with it, counting and breathing and moaning until it was over. It was time to be active, to decide when to push, when to breathe, when to rest.

Pushing your baby out works best when you do just what your body wants, without external direction. Bear down when you feel the urge—an innate reflex stimulated when your body produces high levels of oxytocin in response to pressure from your baby’s head low in your pelvis. In the past, women were taught to hold their breath and push during each contraction. Many providers may still tell you to hold your breath and push down as hard as you can for a count of ten. But breath holding and sustained, directed bearing down can be exhausting and frequently do more harm than good. Studies of women in labor have shown that holding your breath can increase the chance of worrisome fetal heart rate patterns because your baby does not get as much oxygen when you push this way.24 With gentle support and positive feedback, you can follow your own urges and find a rhythm that feels right and moves your baby down. You or your labor support companions may need to tell your care providers not to direct you how and when to push.

When I was pushing, really pushing, I felt powerful. When I realized that I was in charge of pushing, and when I felt my contractions as guides to how often and for how long I should push, I started to reel in my mounting panic and to harness my energy.

Depending on the baby’s position, pushing can sometimes be very painful and very hard work. Change positions to relieve pressure points and to find positions that are more comfortable for you. Sometimes pushing while sitting on the toilet can be effective, as we are psychologically conditioned to relax our pelvic muscles there. Being upright (leaning, squatting, hanging from something or someone) may lessen pain and backache. Upright positions may also help align the baby in your pelvis better and open the pelvic bones a bit to give the baby more room, allowing her or him to navigate through the birth canal more easily.

It may take only a few pushes, or it may take a few hours of pushing, to birth your baby. As long as both you and your baby are doing fine and the baby is moving down, there’s no reason to limit this phase of labor.

Photos courtesy of Judith Bishop

Between pushes, breathe slowly and rest. You might even fall asleep for a few minutes. Remember that—just as in earlier phases of labor—your uterus works involuntarily to move the baby down and out. Work with it, and give it time. Your labor may not progress as quickly as you had imagined or as others around you expect.

When the pushing stage of labor is nearing its end, the baby moves under your pubic arch, and your perineum, the area between the vaginal opening and the rectum, stretches slowly to accommodate the head. Gentle guidance to push slowly and with short pushes at this stage, encouragement of favorable positions, and techniques such as touch, hot compresses, and warm oils applied to the perineum for comfort all work with this process and may prevent or minimize tearing. When you feel a burning sensation, breathe lightly so as not to push too rapidly and risk tearing. Reaching down to touch your baby’s head for the first time often produces an “Ahhhh” that opens you up even more.

A midwife who gave birth at home says:

I often tell women in labor that they will feel a second wind—a surge of energy—when it is time to push. I found that this didn’t really happen when I started pushing. But I definitely felt this when I started feeling the stretching and knew [my baby] would be born soon. It was like the only thing I needed to do in the world was push with all of my might. And that was true! It was the only thing I had to do. All the wonderful people supporting me were taking care of every single other thing.

I pushed and the burning peaked, and then, all of a sudden, nothing. My baby’s head was out. It is truly amazing how quickly you can go from the most intense pain to no pain at all.

Within seconds of birth, babies make a remarkable transition from life in the womb, where all of their needs were met by the placenta, to life outside the womb, where they must regulate their own breathing, temperature, and digestion. These transitions happen most easily when the baby is placed on your chest for skin-to-skin contact with you, with the umbilical cord intact (not clamped immediately) and in an environment of peace and calmness. Sometimes hospital routines or medical complications make it difficult or impossible for the mother and baby to remain in such close contact right after birth. Babies can overcome these disruptions when they are medically necessary, but it is best to keep the mother and baby together barring extreme circumstances.

Some babies breathe as they are being born and look pink immediately. Others take a few moments to begin breathing, a process that unfolds as blood continues to flow through the umbilical cord.29 Gentle stimulation such as rubbing the baby’s back can also help a baby begin breathing in a regular, sustained way. Healthy babies are usually able to clear their own airways of fluid and mucus without suctioning. If there was meconium (the baby’s first bowel movement) in the amniotic fluid and the baby isn’t breathing immediately, she or he may need suctioning right after birth to prevent the meconium from getting into her or his lungs.

Not all newborns cry. Some do for a moment and then stop. Often they breathe, blink, and look around or cough, sneeze, and snuffle. Your baby’s head may appear oddly shaped, having been temporarily molded by coming through the birth canal. Her or his body may be covered with patches of vernix, a white, waxy substance that coats and protects the baby’s skin inside the uterus. All babies arrive wet with amniotic fluid.

© Britt Fohrman

Mothers and babies belong together during this precious time. When you feel ready, hold your baby naked against your belly and breasts, near the familiar sound of your heart, so that she or he can touch your skin and smell, hear, and see you. You and your new child need as much peace and quiet time together as you can create. In any setting, well-meaning providers and others can interrupt this important personal time because they want to know how you and your baby are doing. In a hospital, medical personnel may have their own schedules for evaluations. Providers can often unobtrusively examine your baby in your arms. It is usually not necessary to have tests done right away. If there is a medical reason to take your baby away from you for a short time, your partner or support person may accompany the baby.

Writing to her child, one woman recalls:

You were perfect, of course. Sue caught you and placed your warm, wet body on my chest. You immediately gave out a healthy, albeit short, cry and then just looked around and took it all in. The three of us just sat there getting to know each other. We were so in awe and in love with you that we forgot to check to see whether you were a boy or girl!

You may approach labor and birth with a vision of how you will react when you first meet your baby. It is common to have a reaction that does not match up with a vision of instantaneous bonding. Often disbelief, shock, wonder, or an overwhelming sense of pride are the first emotions. As you spend quiet moments with your baby over the next hours and days, the bonding process will intensify.

Delivering the placenta completes the birthing process. After five to thirty minutes or so, the umbilical cord lengthens, a contraction occurs, and the placenta is expelled, often with a gush of blood. Breastfeeding or simple skin-to-skin contact in a quiet and undisturbed environment stimulates this process. It’s important that your providers not pull on the placenta before it has separated from the uterine wall. It is very important that no fragments of the placenta remain in your uterus, as these fragments may allow blood vessels to remain open, causing hemorrhage. Retained fragments can also put you at risk for infection in the uterus. Your care provider will inspect your placenta carefully to make sure it is complete and intact.

Once the placenta comes out, blood vessels close off. Your uterus contracts and begins to shrink. After the placenta is out, your baby’s suckling helps keep your uterus firm and contracted.

Some view the placenta as a beautiful organ, with its pattern of blood vessels resembling a tree of life. Many cultures have rituals surrounding the afterbirth, including planting trees or flowering bushes above it. Let the staff know if you want to see and/or keep the placenta.

© Eric Silverberg

The first few hours of a baby’s life are a time of heightened alertness. Breastfeeding will be easier to establish if your baby nurses at least briefly within the first hour or two after birth. Babies have an instinctive sucking reflex but show varying degrees of interest and take different amounts of time to nurse. Some latch on to the breast immediately; others learn to do so more gradually. Smelling, licking, and exploring your breasts are part of the process. Allowing your baby to suckle, even if you don’t plan to breast-feed, will give her or him the benefit of antibodies and nutrients from colostrum, the first milk. After a few hours, your baby will fall asleep, and when he or she wakes up the next time, breast-feeding may not be as easy as it was the first time. Over the first twenty-four to seventy-two hours, your baby will learn all the coordinated moves used to latch on to your breast and nurse effectively. If she or he was able to nurse initially right after birth, the learning process will be a little faster and can set you on the path of a long, fulfilling breastfeeding relationship.

You might want to ask your midwife or doctor in advance to help you start breastfeeding by placing your baby onto your belly or chest, skin to skin, right after birth. Also, if you are planning to breastfeed, it is important to insist that the baby not be given any water or formula without a clear medical need.

At home and in birthing centers, it is usually easy for you both to be together, sleeping and waking together, getting to know each other, the baby nursing whenever she or he desires. In the hospital, specifically request that your baby remain with you. If a practitioner thinks that separation is needed, ask for an explanation and remind hospital staff that you want your baby to remain with you. Even if medical observation or treatment becomes necessary, it is usually possible for you or your partner to stay with your baby.

My first baby was a face presentation, mentum posterior, and there was no way he would have made it out alive vaginally; that position wedges the baby’s face between the sacrum and the pubic bone, with no room to descend. I had a C-section in a small local hospital. The OR [operating room] was actually warm. . . . My midwife and my partner were with me, right in the OR! It was a good way for this skeptic to learn that yes, a surgical birth can be a positive event. I had minimal anesthesia and had the baby back with me within an hour or so of his birth.

In certain circumstances, cesarean sections are clearly needed for the safety of the mother and/or the baby. In other circumstances, it can be difficult to determine whether or not the surgery is medically necessary and a different care path might have resulted in healthy vaginal birth. The risks and benefits of a cesarean vary according to your specific situation. Ideally, you will discuss during prenatal visits the possibility of having a cesarean section, although many of the circumstances that require birth by cesarean section emerge only during labor.

I’d always dreamed of having a home birth and, if that wasn’t possible, to give birth in a birth center with a midwife. At thirty-two weeks, I had some bright red spotting. My midwife came to the hospital with me for an ultrasound, which showed that my placenta was partially covering my cervical opening. The obstetrician held out the possibility that the placenta might still move away from the cervix, although he was doubtful. I returned home with directions to call immediately if there was any more bleeding. At thirty-five weeks, I woke to find blood pouring. With a towel between my legs, I called my midwife, jumped in the car, and headed to the hospital, where my lovely five-pound daughter, Chiara, was delivered by cesarean section.

If you are giving birth by cesarean section, whether planned or not, the process will start in an operating room, where you will usually receive spinal or epidural anesthesia to make you completely numb below the level of your ribs. Your partner or support person may be asked to wait outside the operating room while the spinal or epidural is being set up, but in most instances he or she can return to the room to support you during the surgery. If an epidural catheter (tube) is already in place when the decision for surgery is made, the level of anesthesia will be increased so that you are completely numb.

In the rare instance when a cesarean section needs to be performed very quickly, you may be given general anesthesia (which makes you unconscious), because it is faster than making you numb with a spinal or epidural. General anesthesia is also used in the rare instances when an adequate level of anesthesia is not obtained with a spinal or epidural.

For most cesarean sections, your belly will be scrubbed and you will be given a dose of antibiotics before or during the procedure to reduce the risk of infection. In addition, a small tube (catheter) will be placed in your bladder to keep it empty during the procedure. A drape will be placed between your chest and the lower part of your body to create a sterile area for the operation. The drape also prevents you from seeing the surgery as it happens, although you can ask to have it lowered enough to see the baby emerge, if you prefer. Sometimes the drape is close to your neck, but you can turn your head to the side if it makes you feel claustrophobic. Orgasmic Birth authors Elizabeth Davis and Debra Pascali-Bonaro also suggest:

You may be able to have music in the room, aromatherapy on a tissue at your nose, touch support from your partner or doula, the opportunity to see the baby emerge by watching in a mirror, and photos (taken by your partner or doula) of your first few moments with your baby.30

Your arms may be strapped down at either side to keep you from inadvertently touching the sterile field, although some hospitals are doing away with this requirement because it makes some women feel vulnerable and helpless. If you prefer to have one or both arms free, say so. Operating room staff will attach a sticky patch to your skin and place a small clip over one of your fingers that monitors your vital signs. In most hospitals, if you do not have general anesthesia, a support person or partner as well as a doula or midwife can be present during the surgery. He or she will likely stay at the head of the bed, next to your head, behind the drape.

After the anesthesia has taken effect, the surgeon will usually make a horizontal incision in your skin, low down near the pubic bone—the so-called bikini cut. The surgeon will then open up the layers inside your abdomen and cut through the uterine muscle to lift your baby out.

I looked up at my husband. There he was, looking quite ridiculous in his blue scrubs and hairnet. He was standing slightly, just enough to see over the draped curtain. His eyes [were] intently staring. I can’t even be certain he blinked. When the doctor announced the birth of our daughter, there was no need for him to say it. I saw it on my husband’s face, the birth of his daughter. His eyes widened at first, almost as if someone had stomped on his toe, then he began to cry. The look on his face was amazement, pride, love. I saw the birth of our daughter that day, too . . . through the eyes of my husband. It was beautiful.

© Can Stock Photo Inc. / M. Valigursky

The surgeon will clamp and cut the umbilical cord and hand your baby to a nurse or other attendant, who will suction your baby’s nose and mouth if needed and assess the baby’s breathing. Once the baby is breathing normally and has been bundled into a warm blanket, your partner and you can hold your baby next to you cheek to cheek and you can welcome your child even as the doctor removes the placenta, sews up the incision, and closes the skin with sutures or staples. The entire procedure usually takes about an hour.

Following your surgery, you will be cleaned up in the operating room and taken to a recovery room, where you can focus on getting to know your baby. This is an important time to start breastfeeding. The baby is usually alert for the first hour or two after birth. Ask for help if you feel that you cannot start breastfeeding on your own. The surgery and recovery pose extra challenges for getting breastfeeding off the ground, and good support and your determination can make all the difference. During this time, if you have had a spinal or epidural, the anesthesia will gradually wear off. If you received a long-acting medication in the spinal/epidural catheter, you shouldn’t have much pain the first twenty-four hours. If you did not have the long-acting medicine, you will be given IV pain medication as needed. Usually, after a few hours you are ready to go to your postpartum room.

Women who have complicated labor and obstetric emergencies understand the necessity of a cesarean section. Some experience a cesarean section as a relief, even while wondering whether or not it was truly necessary. Some fault themselves, feeling guilty or defensive that they didn’t do “everything possible” to have a vaginal birth even though they did the best they could, given their physical circumstances and the information and support available. It’s normal for women to have a wide variety of emotional responses to a cesarean. Honor your feelings, whatever they are. If you feel you need additional support after a cesarean, visit the website of the International Cesarean Awareness Network (ican-online.org).

A midwife says:

I tell women who begin labor at home and end up in a hospital, “Who you are never changes. Your planning, ideals, beliefs, and principles never change just because you end up with a cesarean. You are stronger than you would have been, because you’ve gone through all these decisions and made the choices you did.”

We relive the births of our children many times during the days, weeks, months, and years afterward. Looking back upon your birth experience may call up a wide range of emotions. You may feel fulfilled, ecstatic, and immensely close to your loved ones and your baby, especially if you felt supported and respected throughout the process. You may feel joy, wonder, and a great sense of accomplishment.

© Patti Ramos Photography

On the other hand, if unexpected complications, medical interventions, or insensitive comments and behaviors of medical personnel dominated your birth experience, you may feel a bewildering mix of joy and disappointment. You may feel distant from your baby. It is not uncommon to apologize for having wanted more (“It doesn’t matter—after all, my baby is healthy, and that’s all that counts”) or to feel sad or guilty about not having had the birth you wanted. Worst of all, you may blame yourself—“My body just didn’t work right”—instead of recognizing that you did not get the support that might have resulted in a different outcome or that birth is, in the end, unpredictable.

Even though I was relieved that everything was okay and thrilled with my baby, I had the nagging sense that I had failed somehow. Later I got over feeling that it was my fault, but I still felt cheated out of the birth experience we had hoped and planned for. Sometimes I still can’t help feeling a little jealous when I hear women talk about their wonderful birth experiences.

It is normal to have doubts, regret, grief, or anger rising to the surface over time. Talk with your partner, good friends, or a counselor for comfort, understanding, and support. Women’s groups and online discussion groups or chat rooms may also be helpful.

If you are dissatisfied and want to learn more about what happened, get a copy of your baby’s birth records. Check them against your memories. Talk to the practitioner and others who attended your labor. Write letters to those you feel did not meet your needs; it may help them to become more responsive and respectful in the future. Going through some of these processes may make it possible for you to feel more at peace.

The transformation to becoming a mother is profound; the demands are huge. With a new baby you experience a new identity and responsibilities, a connection with someone who, having been part of yourself for nine months, now becomes an individual outside of yourself who needs your help and support twenty-four hours a day. Our society provides mothers with few if any rituals, resources, or social supports for this transition. Most other Western industrialized societies offer generous paid maternity and paternity leave, flexible working conditions, quality state-run day care programs, and well-organized midwifery services. Though there is little government support for new parents in the United States, many communities have active doula groups, birth networks, breastfeeding support, or new parents’ organizations. These groups offer much-needed help with the joyful, difficult, passionate, challenging work of being a mother.

Even now, twenty-four years after my daughter’s birth, I am still learning how powerful that event was. It is amazing how the experience of pregnancy, labor, and birth keeps reaching across the years of my life to open doors in my heart.