On May 31, 2009, anti–abortion rights activist Scott Roeder shot and killed Dr. George Tiller during Sunday morning services at Tiller’s church in Wichita, Kansas. The target of constant protests, Tiller had survived a clinic bombing, previous shooting, and multiple legal challenges to close his practice, Women’s Health Care Services—one of only three clinics in the country that performed abortions after twenty-one weeks.

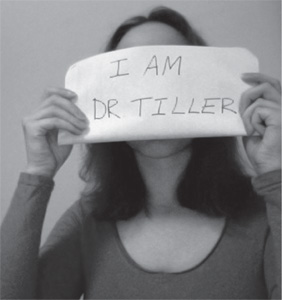

Within days of Tiller’s death, Steph Herold, a twenty-one-year-old recent college grad who was working as an abortion counselor in Pennsylvania, created the website I Am Dr. Tiller (IAmDrTiller.com). She sent the link to feminist blogs and women’s clinics, asking for stories from individuals working to make abortion safe, legal, and accessible. Submissions came in from nurses, medical students, escorts, volunteers at abortion funds, and abortion doctors themselves—all of whom held up a sheet of paper or sign proclaiming “I Am Dr. Tiller.” Criticism by Fox News host Bill O’Reilly only increased the site’s popularity.

Courtesy of IAmDrTiller.com

Herold also created a Twitter account—@iamdrtiller—to promote the stories and, later, to continue sharing facts and information around reproductive rights and justice and to connect with other pro-choice activists. She also founded a blog run by a group of young feminist activists (read her story).

Using new media tools and technologies, it’s easier for us to find and build community and make our voices heard. Today, anyone with a mobile phone or Internet connection can share information, create awareness, and attract the attention of policy makers or other stakeholders. While traditional forms of activism—such as street protests, boycotts, and well-crafted media campaigns—are still necessary and effective ways of gaining support and attention for some causes, the Internet and social media have transformed not only how we organize but also our ideas about what organizing or activism means.

There has never been a greater likelihood that one voice can make a difference. In fact, a far-reaching campaign is often started by just one person taking action—and today it might begin with blogging or raising awareness on Facebook, or tweeting about an injustice happening this very second. What may start as a small group of voices united by a common goal or grievance can develop into an organized and sustainable movement.

One group using the latest technological tools to effect change, the crowd-sourced initiative Hollaback! (ihollaback.org), formed to counter the street harassment frequently encountered by women and LGBTQ individuals. The movement encourages people to share their stories and to report instances of street harassment, from unwanted verbal attention to acts of touching or groping, using mobile technology such as the Hollaback! iPhone app. From its founding in New York City in 2005, Hollaback! has grown into an international movement.

We also have access to more information and viewpoints than ever before. Politicians, activist groups, and media sources keep us informed via email, text messages, and social networks. Racialicious (racialicious.com), Colorlines (color lines.com), Feministing (feminist ing.com), Pam’s House Blend (pamshouseblend.com), Feministe (feministe.us/blog), Pandagon (pandagon.net), INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence (inciteblog.wordpress.com), Shakesville (shakespearessister.blogspot.com), and The F Word (thefword.org.uk) are more than sites to visit for daily news and activism; they’re feminist communities where readers share, commiserate, and challenge one another. The do-it-yourself dynamic of blogs enables a wide variety of voices to reach a larger audience and become part of the dialogue.

Through social media, more teens and young women are speaking out and taking a stand. Julie Zeilinger was a fifteen-year-old high school student in Pepper Pike, Ohio, when she launched fbomb (thefbomb.org) in 2008 with the goal of creating a community and dialogue for teenage girls “who care about their rights as women and want to be heard.” Within two years, Zeilinger’s site had published submissions from all over the world.1

In this new era, traditional gatekeepers have been replaced by a decentralized assembly of digitally empowered citizen journalists. Organizing takes place independent of geographical boundaries, and stories have the potential to reach large audiences quickly. On the flip side, communities have never been more diffuse, and standing out among so many voices can be difficult. Online petitions and other forms of viral protest are sometimes dismissed as ineffective slacktivism. And access to new technology isn’t universal; a digital divide exists between the digitally adept and those without access to digital tools and/or those who lack the knowledge and skills to be media creators as well as consumers. Spending a few hours a week in a school computer lab isn’t the same as having a laptop or iPad in your backpack.

While social networking and digital media have certainly become important catalysts for change, providing new and effective forms of expression, we need to work to increase access so all of us have the tools and the means to tell our own stories.

This impulse toward activism usually begins when something affects us or someone we know. We may be motivated by a health problem or by injustices in our neighborhoods and schools. A friend or family member may alert us to issues we care deeply about and want to work to improve.

Organizing does not take experts or a lot of money. What it does take is a committed group of individuals willing to invest time and energy to work together toward a common goal. The Internet and mobile technology (which has even higher use among African Americans and Latinos than among whites)2 have made it easier for more people from diverse backgrounds to share information and get involved in causes that matter most to them.

Creating change on a larger level takes many voices. After we have taken a few steps on our own, we may want to get involved with groups working on an issue or start a group of our own. Here are some questions for groups to consider in the early stages of organizing:

• Can we clearly define our issue?

• What do we already know about the issue? What don’t we know? What research has already been done, and by whom?

• What will be the scope of our work? Do we have enough people to manage the work we want to do?

• Which online/offline communications tools will we use to spread our message? Which communication tools are used by the people most affected by this issue?

• Are there organizations or individuals already working on the problem? If so, how can we work together?

• How many women are affected? Are the women most affected involved in efforts to create solutions?

• Who are the opposition? How are they supported/funded?

• What approaches to the problem are we considering? What resources are needed to accomplish them? Where will we find the needed resources?

• How will our group be organized? What will be our group norms on inclusiveness, diversity, decision making, and logistics?

The answers to these questions will help you to create a supportive group infrastructure and work toward formulating an action plan. Think of specific objectives and consider what tools and resources you need to realize each goal. Remember to focus on telling people’s stories, which helps to personalize the issue.

Don’t assume that everyone will know about an event if you post it on Facebook. Think about whom you’re trying to reach and adapt your message—and your medium—accordingly.

In our group, very few women had experience speaking publicly to or before the media. So we set aside some meetings to role-play, to practice speaking before a group, and to learn how to say the most important things in the least amount of time. We also practiced saying the things we wanted people to hear, even if they were not related to the interviewer’s question. Doing all this is a great way to break through shyness and stage fright.

Need help making your voice heard? These groups work with individuals and organizations, helping them to tell their own stories and develop media expertise.

• The OpEd Project (opedproject.org) trains female experts in all fields to write for the op-ed pages of major print and online forums of public discourse. The OpEd Project works with universities, nonprofits, corporations, women’s organizations, and community leaders and offers seminars open to the public in major cities across the nation. Scholarships are available.

• The Women’s Media Center (womensme diacenter.org) aims to make women visible and powerful in the media. In addition to offering media training workshops to the public, women can apply for the Progressive Women’s Voices Project, an all-expenses paid program that trains women to position themselves as thought leaders/experts in their fields; craft strong media messages and newsworthy pitches; and prepare for both friendly and hostile broadcast inter-views.

• Barefoot Workshops (barefootworkshops.org) is a New York City–based nonprofit organization that teaches individuals and organizations how to use digital video, new media, and the arts to transform their communities and themselves.

• “Get Noticed! How to Publicize Your Book or Film” (aidandabet.org/resources/get-noticed) is your DIY guide to promoting a project. Written by Jen Angel, Matt Dineen, and Justine Johnson, this fifty-plus-page booklet covers everything from writing press materials to using social media and pitching stories to reporters at independent and mainstream media outlets.

In recent years, women of color and their allies have organized a reproductive justice movement that examines how issues of race and class affect women’s abilities to exercise their reproductive rights. This dynamic movement is growing, and today many organizations and networks are taking part. The largest among them is SisterSong, a network of eighty local, regional, and national organizations (and many other affiliate organizations) representing five primary ethnic populations/indigenous nations in the United States: African American, Arab American/Middle Eastern, Asian/Pacific Islander, Latina, and Native American/Indigenous.

The reproductive justice movement promotes a broader understanding of women’s rights and health, placing abortion within a larger framework that includes maternal and infant health, economic justice, racial equality, and ending violence against women. There are three main frameworks for addressing reproductive oppression: reproductive rights (legal structures), reproductive health (service delivery), and reproductive justice (movement building).

Organizations and individuals are working to strengthen each of these pillars and, by doing so, they are improving access for all women.

In 2010, the Georgia state legislature took up a bill that aimed to limit access to reproductive services. The new twist: The bill falsely proclaimed that women of color were being targeted by abortion providers. So-called “pro-life freedom rides” in the summer of 2010 co-opted important civil rights legacies in order to try to deny women of color access to reproductive choice. This followed on the heels of a controversial anti–abortion rights billboard campaign that called black children “an endangered species.”

“You cannot save black babies by discriminating against black women,” said Loretta Ross, national coordinator of SisterSong. “Civil rights has always been about expanding freedoms for black people, not rolling back the clock to the nineteenth century like these anti-abortionists want. Should black women again become breeders for their cause?”

Courtesy of Loretta Ross.

Loretta Ross, a founder and the National Coordinator of the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Health Collective, speaks at a Georgia rally for immigration rights in March 2011.

True freedom, she added, ensures human rights for all people, including reproductive rights and reproductive health care options for women.

When anti–abortion rights activists arrived by bus in Atlanta on July 24, SisterSong, along with SPARK Reproductive Justice NOW (sparkrj.org) and SisterLove (sisterlove.org) were waiting, their voices ready. This is Ross’s story from the counterrally:

More than fifty supporters came from Project South, Advocates for Youth, Feminist Women’s Health Center, the Malcolm X Movement, and of course, SPARK, SisterSong, and SisterLove. The folks were mostly African American, but a number of Latinas and some white activists came in solidarity. It was a decidedly young group, with only a few elders like me sitting back and watching them lead. We had a spirited rally for about an hour, with speeches and statements of solidarity, like from the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice.

Then the anti-abortionists’ bus and cars pulled up in front of the King Center. Staying on our side of the street as they disembarked, we started chanting. “Trust Black Women” as loudly as we could, holding up signs that read “You Can’t Steal Civil Rights” and “Women’s Rights are Human Rights.” Paris Hatcher and Tonya Williams from SPARK, and Heidi Williamson of SisterSong, led the rally with spirit and energy that really excited our side and kept everyone engaged and having fun.

We were quite surprised when the antis piled off the bus—all but four of whom were white as far as we could tell! For a campaign organized by the African-American outreach director for Priests for Life, Alveda King, it was surreal seeing all these white folks carrying signs that said “Abortion Is the #1 Killer of Black America.” Can you imagine the optics of the scene? Here’s a group of white folks claiming to save black babies being protested by mostly African-American women and men who are shouting “Trust Black Women!” Once we saw their signs, Paris instantly created a new chant: “Racism Is the #1 Killer of Black America, Not Black Women!” The ironies of the day seemed endless—when was the last time black folks protested at a white folks’ rally at the center named after Dr. Martin Luther King?

After marching in front of the tombs and reassembling on the sidewalk until they were told to move on, the antis left their side of the street and walked around the back of our demonstration to hold their prayer service on the grass behind the amphitheater where we were, possibly upon orders by the park police. Suddenly, there were no barriers, no police, nothing between the two groups. At first, everyone kept their distance—we shouted, they sang; we held up signs, they held up their hands. Then things got interesting when they decided to cross the invisible barrier and start praying over us. The park police providentially appeared and kept both sides apart.

It seemed a bit ridiculous when they started singing “We Shall Overcome” to counter our singing “Lift Ev’ry Voice.” Eventually, the heat of the day wore everyone out. They moved across the street again (not in front of the King Center) in order to finish their praying. We climbed to the top of the amphitheater to look down on them to continue our chant, “Trust Black Women!” I think we frustrated them because I’m sure many of these white folks assumed the black community of Atlanta would welcome them as saviors of the black race. It was obvious they were more than a little uncomfortable at being shouted down by black women. After about an hour and a half of this back and forth, they boarded their bus and left and so did we, but not without singing, “Nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah. Hey-hey-hey. Good-bye.”

Website: advocatesforpregnantwomen.org In October 2010, Colorado voters rejected a ballot measure seeking to classify “preborns” as “legal persons with protection under the law.” With implications that went far beyond attempting to restrict abortion, this measure would have granted fetuses, embryos, and even fertilized eggs legal status separate from the women who carry them. The National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW), an advocacy group working on behalf of all pregnant women, published a commentary criticizing the Colorado measure’s sponsor Personhood USA’s “radical fetal-separatist agenda” and helped defeat the ballot measure. Other states, including Montana and Nevada, have attempted without success to pass similar laws.

Lynn M. Paltrow, founder and executive director of NAPW, wrote, “Pregnant women could be sued, subject to child welfare interventions, or even arrested if they engaged in activities at work and at home that might be thought to create a risk to the life of the ‘preborn.’ Legally separating the ‘preborn’ from the pregnant women who sustain them will ensure that in jobs, education, and civic life, pregnant women will, once again, be unequal to men.”3

Speaking out against laws that undermine the rights of women, the NAPW formed to expand the reproductive rights movement to all parenting and pregnant women, including those who plan to continue their pregnancies to term. Through a wide array of advocacy work—including local and national organizing, litigation, public policy development, and public education—the organization works to secure reproductive rights for all women, especially underrepresented and at-risk groups such as women of color, low-income women, and women addicted to drugs or alcohol. In addition to safe and legal abortion, the organization lobbies for access to adequate prenatal health care, alternative birthing practices, support for vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), and nonpunitive drug treatment services for pregnant women.

NAPW’s legal advocates vocally oppose the shackling of inmates during labor and the criminalization of drug addiction in pregnancy and have provided litigation support in a variety of related cases across the country. Relying on a network of more than two thousand local and national activists, the group has challenged the arrests of pregnant women charged with child endangerment for drinking alcohol and has formed alliances with other organizations to file amicus (friend of the court) briefs explaining how so-called fetal rights laws dehumanize and criminalize pregnant women.

Websites: abortiongang.org and iamdrtiller.com

Steph Herold is a reproductive justice activist who has worked in direct service abortion care and reproductive health advocacy.

In 2010, I created the Abortion Gang blog as a space specifically for young people in the reproductive justice movement, with the goal of raising our visibility and highlighting our activism.

There were a number of articles in the mainstream media that year claiming that young people weren’t pro-choice enough or were not engaged in meaningful activist work. I wanted to counteract those attitudes with tangible evidence. The next time someone wondered what young people were doing, I could point to numerous activities documented on the blog.

The name “Abortion Gang” came out of the seemingly endless health care reform debates. Then-representative Bart Stupak was accused of having an “abortion gang”—a group of congressmen who were committed to voting no on the bill unless Stupak’s antichoice abortion language was included. My first reaction was: Why does this antichoice, antiwoman politician get to have an abortion gang? He doesn’t know the first thing about abortion, women’s health, and reproductive justice, to say the least. If there’s anyone who could disqualify from being in an abortion gang, it’s Bart Stupak. So I decided to start the real abortion gang, one composed of people fully committed to abortion rights.

When the blog first appeared, we received some criticism from within the feminist community, asking why we focus specifically on abortion. I explained that calling ourselves an abortion gang means that we are committed to destigmatizing not only abortion care work but also reproductive justice activism. We support all aspects of reproductive justice work and do not shy away from controversy and complexity. We embrace and analyze it in order to better understand why we do what we do, and to explore the power of justice and compassion.

© Darrin Weathersby

In the past year and a half, I’ve launched the Abortion Gang blog, the I Am Dr. Tiller project, and both Twitter accounts associated with these initiatives. The success of each of these campaigns speaks volumes to the power of social media and the Internet as organizing tools.

A case study of just how powerful online campaigns can be is the Twitter hashtag I started in the fall of 2010, #IHadAnAbortion. I asked women to tweet their abortion stories as a way to counteract the stigma associated with abortion. I had no idea what to expect, if there was going to be any response at all. What happened in the next twenty-four hours amazed me: Women shared their stories, women who had previously been completely absent from the pro-choice activist community. It didn’t take long for the media to catch on, and soon enough, CNN, PBS, and a variety of mainstream media, online and off, were talking about this phenomenon. Did they understand it? Usually not. But their coverage showed that this campaign struck a nerve, and this exposure led more women to speak out and find a new community of people who support them and their reproductive choices.

That isn’t to say the world of social media advocacy isn’t without its complexities and problems. If you looked at the hashtag a few weeks later, it’s dominated by antichoice cruelty and misinformation. That is the reality of online organizing: when you open up a conversation, everyone has access to it.

A clever advertising tactic is to manipulate the message that many feminists have tried to promote: Girls have the power to be anything and to do anything they want. It’s not surprising that in what author and activist Ariel Levy calls “raunch culture,” advertisers and other media have reinterpreted this idea. In a male-centered culture, where female athletes gain praise and recognition when they pose in Playboy and pop stars focus first and foremost on how sexy and attractive they are, this girl power gets translated into a distorted message that tells girls they can wear anything they want and no one can tell them otherwise.

In this interpretation, power has nothing to do with character or achievement but instead equates to the power of sexual attraction. For tweens and teens navigating this landscape, the pressure and expectation to be pretty, thin, and sexy can become an all-consuming task.

Levy aptly observes: “Adolescent girls in particular—who are blitzed with cultural pressure to be hot, to seem sexy—have a very difficult time learning to recognize their own sexual desire, which would seem a critical component of feeling sexy.”4 The notion that performance of sexuality equals power and control is particularly perilous for girls navigating their way to adulthood.

The APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls, formed by the American Psychological Association, issued a report in 2007 (updated in 2010)5 addressing the omnipresence and damaging effects of sexualized images of girls and young women in every media format studied, including advertising, television, movies, music videos, music lyrics, magazines, sports media, video games, and online.

As expected, the images and depictions of women presented reflect a narrow—and unrealistic—standard of beauty that serves to undermine women. And, according to the report, sexualization has a host of negative psychological consequences for girls and young women—it affects their “cognitive functioning, physical and mental health, sexuality, and attitudes and beliefs” and harms “girls’ self-image and healthy development.” (See Chapter 3, “Body Image,” for more discussion.)

The report also took an important step in identifying the components of sexualization, noting that it occurs when:

• a person’s value comes only from his or her sexual appeal or behavior, to the exclusion of other characteristics

• a person is held to a standard that equates physical attractiveness (narrowly defined) with being sexy

• a person is sexually objectified—that is, made into a thing for others’ sexual use, rather than seen as a person with the capacity for independent action and decision making

• sexuality is inappropriately imposed upon a person

In response to this widespread problem, feminist and youth groups are promoting their own positive messages about sexuality tied to thinking critically about media representations of girls and women. New Moon Girls (newmoon.com) is both a magazine and a moderated online community for girls ages eight and older. Designed to help girls develop healthy body image, the site features articles on girls changing the world, stories about arts and culture from around the world, and a safe and moderated chat room where girls can express themselves and share ideas. Girls can also create and share their own artwork, poetry, and videos through the site.

Dedicated to the health and well-being of girls and young women, Hardy Girls Healthy Women (hghw.org) is a nonprofit that works to give girls opportunities to explore new interests and build alliances with other girls. The organization trains adults who work with girls in second to twelfth grade and develops programs that encourage girls to think critically about media depictions of women and recognize and address unfairness. On the website, a program participant named Beth says: “When I see an ad that is selling women instead of the product, I recognize it. When I hear a sexist comment, I recognize it. And when I feel the need to speak my mind, I do, and without feeling out of line.”6

Geared toward an older demographic, Name It, Change It (nameitchangeit.org) is a nonpartisan organization that works to end sexist and misogynistic coverage of women candidates in the media. The site has exposed sexist comments by radio hosts, pundits, bloggers, and journalists that undermine women candidates and leaders.

Finally, if you’re tired of stories that misrepresent girls and women—or leave us out of the picture entirely—visit Women, Action & the Media (womenactionmedia.org), also known as WAM! This organization aims to change the narrative by connecting and supporting media makers, activists, academics, and funders working to advance women’s media participation, ownership, and representation. Among its many offerings is an active and informative Listserv that welcomes students as well as professionals.

In October 2010, Hunter College—in partnership with the Women’s Media Center, Hardy Girls Healthy Women, Ms. Foundation, and numerous other educators and organizations—held the first-ever SPARK Summit (sparksum mit.com) to counter the increasing sexualization of girls in the media.

SPARK in this instance stands for Sexualization Protest: Action, Resistance, Knowledge. Speakers tackled a wide variety of issues, including the marketing of padded bras and thong underwear to little girls, the passive or hypersexualized roles of girls and women in TV and films, and the link between self-sexualization and low self-esteem in teens. More than three hundred people attended the summit, with hundreds more participating online.

At the Women Media Center’s action station—dubbed “Changing the Conversation/Amplifying Your Voice”—girls created their own video journalism, submitted posts to WMC’s blog, and reported on incidents of sexism through the WMC’s Sexism Watch campaign. Some girls went on to be featured on NPR and CBS, in The Huffington Post, in El Diario, and in other media outlets.

As one speaker at the summit explained, the focus wasn’t antisex but, rather, anti-exploitation. Women and girls need to think critically about the messages they’re receiving and “take sexy back”—in other words, reclaim their sexuality in a healthy and positive way.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, more than 80,000 chemicals in use in the United States have never been fully tested for their potential adverse impact on humans or the environment. While the European Union has banned 1,100 dangerous chemicals from use in personal care products, the FDA has banned or restricted only 11. (For more information on toxics and chemicals and their effect on our health, see Chapter 25, “Environmental and Occupational Health.”)

Consider the case of bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical used to make plastics more durable. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence that BPA disrupts the endocrine system and has been shown to cause cancer as well as developmental and reproductive problems, the product is still used in water bottles, baby bottles, the lining of aluminum cans, and other food and drink packaging. Seven states and a few cities have passed laws prohibiting the sale of baby bottles containing BPA, but the federal government has yet to pass a nationwide ban on the chemical’s use in food and drink containers. (Notably, the European Union and Canada have already banned the use of BPA in baby bottles.)

For years, activist groups have taken up the slack, delving into critical issues about the safety of our food, water, and air and carrying out their own research into the effects of chemicals in the environment. The Silent Spring Institute, for example, works to identify and cast light on the links between environmental issues and women’s health, particularly breast cancer. Formed in 1994 to investigate the higher rates of breast cancer on Cape Cod, the organization took its name from Rachel Carson’s landmark 1962 book Silent Spring, which helped launch the environmental movement. The coalition of scientists, physicians, and public health activists at the institute has undertaken research into, among other issues, the environmental causes of breast cancer, rates of household exposure to endocrine disrupters, and the presence of hormone-disrupting chemicals in septic systems.

In an open letter on the organization’s website (silentspring.org), Silent Spring Institute executive director Julia G. Brody details the important questions we should be asking about the link between environmental issues and breast cancer and other diseases: “In the past decade, the very personal question, ‘Why did I get breast cancer?’ has been transformed. New voices ask, ‘Why do we have breast cancer rates higher than generations before and among the highest in the world? What can we do as a community of women and men to change the legacy for our daughters?’”

Website: bcaction.org

In the past two decades, the fight against breast cancer has become a popular cause. Walks, runs, and fund-raisers exist in every major city in the United States. Breast Cancer Action (BCA) has used this growing public interest to challenge the cancer industry—that is, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, research institutes, and other organizations—and insist on increased focus on prevention.

BCA’s Think Before You Pink initiative (thinkbeforeyoupink.org) has challenged a number of misguided breast cancer awareness campaigns that trivialize or sexualize breast cancer—for example, taking to task one manufacturer for selling pink ribbon thongs imprinted with the slogan “I’ve lost my boobies, but not my sex appeal.”

BCA also targets pinkwashers, or companies profiting from pink-cause marketing that make or sell products that could increase the risk of breast cancer. One such pinkwashing campaign was KFC’s “Buckets for the Cure,”7 an attempt by the fried chicken franchise to raise breast cancer awareness in partnership with Susan G. Komen for the Cure. BCA exposed the hypocrisy of linking fast food—and franchises disproportionately located in low-income neighborhoods with limited access to fresh, healthful food options—to efforts to reduce the rate of breast cancer.

In an interview on NPR, Barbara Brenner, former executive director of BCA, countered the assumption that all the marketing and awareness around the disease have solved the problem, saying that “if shopping could cure breast cancer, it would be cured by now.” She continued, “Awareness we have, the question is, what are we doing about it? And when companies can just slap a pink ribbon on any product, then we’re in trouble, because many of those products don’t do anything for breast cancer. And many of them are actually harmful to our health.”8

© Sarah Harding for Breast Cancer Action

In 2008, Think Before You Pink took on the mainstream dairy industry. Yoplait was selling pink-lidded yogurt to raise money for breast cancer. Yoplait’s yogurt, however, was made from milk containing recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH), an artificial hormone injected into cows to make them produce more milk; rBGH may be associated with increased rates of breast, prostate, colon, and other cancers. BCA started an online campaign to raise awareness about the issue and helped activists get their message directly to the CEO of Yoplait’s parent company, General Mills. As a result of the campaign, Yoplait changed to rBGH-free milk. Shortly after, the second-largest dairy product manufacturer, Dannon, followed suit.

The backlash against pinkwashing is gaining momentum and more people—and media—are questioning if the focus on awareness is helping women. In the article “The Downside of Awareness Campaigns,” the Los Angeles Times reported this troubling statistic: “The stark reality is that in the 26 years since the campaign [National Breast Cancer Awareness Month] began, deaths from breast cancer have dropped only slightly—about 2 percent per year, starting in 1990.” Certain breast cancer–related issues, such as overdiagnosis and overtreatment, the article continues, don’t make it into the mainstream literature or most large-scale advocacy compaigns.9

When buying pink products or donating to breast cancer causes, find out about the company’s environmental practices (to learn whether the company contributes to the problem) and how much of the money raised actually goes to support breast cancer research or treatment.

Many women with breast cancer are inspired to ask questions and get involved in efforts to find the answers. One woman recalls how meeting and working with other women transformed her experience:

I was first diagnosed with breast cancer in September of 1991 at the age of forty-two. I was angry, depressed, and hopelessly paralyzed. I was certain that I would die—never to see my children grow up. Within two months, I found a small group of women who were meeting at a coffee shop in my neighborhood. What began as a support group turned into a call to action. I recall bringing homemade petitions to the group and asking people to sign letters to senators, representatives, and even the president of the United States asking for more money for research. We found women in other support groups who were also wanting to mobilize—to channel our anger and our energy. We started to talk about things like environmental exposures and prevention.…As I think back to those first years, I remember clearly the faces of the women in those groups. Some are still alive, many are not. Now it is clear to me how much becoming active in a movement was a vital piece of my getting through treatment and getting well again. For this I am eternally grateful.

In our increasingly plugged-in and interconnected world, it’s never been easier to read stories and view videos created by women working to secure sexual and reproductive health rights around the world. You don’t have to look any farther than Facebook, Flickr, or YouTube to be awed by the range of actions held during the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence (16dayscwgl.rutgers.edu), the international campaign that runs from November 25 (International Day Against Violence Against Women) to December 10 (International Human Rights Day), or to connect deeply with one girl’s story about how she is creating change in her community.

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the idea that to overcome poverty in developing countries, more must be done to invest in the health, education, and empowerment of girls (see, for example, Half the Sky Movement [halftheskymovement.org] and The Girl Effect [thegirleffect.org]), reinforcing the strategies that a number of women’s organizations have been supporting for decades.

The Global Fund for Women (globalfund forwomen.org), for instance, advances human rights by channeling resources into women-run organizations worldwide working toward women’s economic security, health, education, and leadership. It trusts local activists to come up with solutions that best address the needs of their own communities and countries. Since 1988, it has awarded grants to more than 4,200 women’s groups in 171 countries—from helping the multicultural feminist organization The Fiji Women’s Rights Movement (fwrm.org.fj) address inequalities in Fiji’s legal system to supporting the work of Labrys (labrys.kg), a group advocating for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights in Kyrgyzstan .

In Mexico, Semillas (semillas.org.mx) does similar work, awarding grants to organizations that work in four primary areas: human rights, women and work, sexual and reproductive rights, and gender violence. Learn about other women’s funds around the world at the International Network of Women’s Funds (inwf.org) and the Women’s Funding Network (wfnet.org), both of which act as umbrella organizations, linking women’s funds together.

Website: iwhc.org

In September 2009, the Indonesian government passed a new health law that expanded reproductive health services for women. Prior to its passage, abortion was essentially illegal. The new law allows access to abortion in cases of rape or when the life of the woman is threatened. While far from perfect, it’s an encouraging start in a country lacking comprehensive reproductive health care for women.

One primary advocate of the new law was the Jakarta-based Yayasan Kesehatan Perempuan (YKP), or Women’s Health Foundation, which works with health workers and the Indonesian government to promote women’s rights. Funding from the International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC) helped YKP get its message across to policy makers and community leaders and influence the government’s decision to pass the law. The IWHC is also helping YKP promote other reproductive health issues, including increasing access to emergency obstetric care by trained midwives or birth attendants to reduce the maternal mortality rate.

Since 1984, the IWHC has distributed more than $16.5 million in grants to organizations advocating women’s rights and health in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The organization aims to have both a local and a global impact by focusing on two areas that are occasionally at odds: local activism and international policy. In addition to working closely with community and regional organizations and networks in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and Latin America, the IWHC has collaborated with other global women’s health and rights organizations to influence United Nations deliberations. It also has served as an intermediary between UN agencies and local and grassroots advocates on key issues regarding reproductive and sexual health. The IWHC’s collaborations with the World Health Organization focus on access to safe abortion services, sexuality and sexual health, and reproductive health and rights.

The IWHC also runs an informative blog, Akimbo (blog.iwhc.org), that provides coverage of global news and policies related to women’s health and rights. On the anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2011, one of Akimbo’s contributors posted a video about a dangerous abortion procedure that cost a woman her life in rural India. The video stressed that, even in places where abortion is nominally legal, it is not necessarily safe or accessible. The video and post underscored the importance of continuing to advocate for better access to safe abortion procedures and reproductive health care for women worldwide.

Social networks and new technologies have made information incredibly accessible, and the participation of a multitude of voices has made generating awareness and support for women’s issues a more organic and dynamic process. At the same time, the challenges facing the women’s health movement are formidable, and the political atmosphere in the United States has seldom been this volatile.

Regardless of the ever-changing ways we organize and communicate, and despite the nature and complexity of our present challenges, we can find our strength where we have always found it—in community. Together we stand a greater chance of addressing immediate issues while also taking on entrenched stereotypes and power structures.

When we—with our endless variety of backgrounds and experiences—are willing to cross boundaries to listen and learn from one another, anything is possible.

© B. Heidkamp

It wasn’t until I went to a social justice conference that I fully grasped the longevity of the struggle of which I am only the latest small part. I knew that many women had come before me, of course, but to see the generations interacting at this conference was a revelation to me. We have to keep listening and challenging and supporting each other. It’s a long road. But I get goose bumpy thinking of going forward with so many amazing women, of all ages and backgrounds, and I’m grateful that they are my friends and allies.