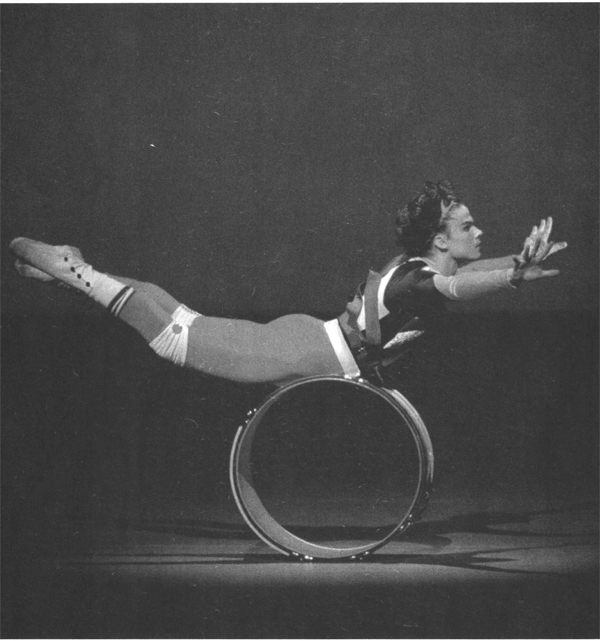

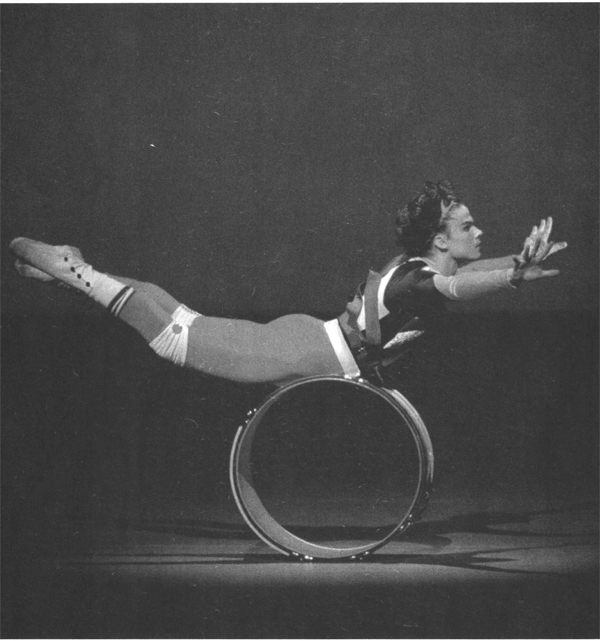

(Adam Hendrickson in Eliot Feld’s The Unanswered Question)

Common Challenges for All Dancers

It’s better to deal with your strengths and weaknesses before you get into a tough situation in dance.

—ADAM HENDRICKSON, NYCB soloist

While injuries are without a doubt a dancer’s worst nightmare, the biggest revelation from New York City Ballet’s research is that many challenges exist long before a dancer is incapacitated. Demanding schedules, emotional stress, worries about food, and difficult floors, costumes, and props top the list. A dancer’s first instinct may be to ignore these problems; however, doing so can compromise both health and career. This chapter describes the common challenges that every dancer faces in order to excel in this profession.

Why is dancing so challenging? Because it requires all of a dancer’s abilities, energy, and resources to handle the artistic and athletic demands, in addition to pleasing an audience. The dancer’s deep connection to movement as a form of self-expression is all-encompassing. These demands apply not only to company dancers with extensive touring and performance schedules (such as NYCB) but to Broadway “gypsies” in musical theater, “commercial” dancers who do world tours with pop stars like Beyoncé, and aspiring professionals and students. The message from NYCB’s wellness program is that it’s okay for dancers—from ballet to tap—to have problems. These should not be seen as a sign of failure; they just need to be addressed.

The Warning Signs in Dance

The biggest dilemma for many dancers is spotting the warning signs that lead to major problems. Before we focus on the findings from NYCB’s survey, let’s play detective by looking at three case studies of dancers who are experiencing occupational stress. Can you uncover each of their problems?

Amy is a seventeen-year-old ballet student enrolled in a six-week summer dance program. She’s delighted to have passed the audition (scary!), even though it’s intimidating to be surrounded by a roomful of talented dancers. A typical day begins at 9:00 A.M. and includes three to four technique classes. Amy tries to follow a nutritionally balanced 1,100-calorie meal plan because she wants to be thin enough to beat out the competition for a spot in the winter program. Yet she’s gained five pounds over four weeks by pigging out on chocolate right before bedtime. What is she doing wrong?

Although you might jump to the conclusion that Amy’s problem is nerves, let’s take a closer look at her food intake. She currently eats a balanced meal plan (that is, healthy sources of carbohydrates, protein, and fats). However, there is a missing ingredient—calories! Without taking in a sufficient amount of food to balance her energy needs, cravings for sweets rule Amy’s life, especially when her defenses are down late at night. The challenge: to increase her caloric intake by making sensible choices throughout the day without feeling guilty or compromising her weight goals.

Then there is Mike, who relies on the gym rather than dance class to stay in physical shape, since it can be months before he finds work in musical theater, where he sings, acts, and dances (known as the “triple threat”). After finally landing a Broadway show, which is like hitting the lottery, he is thrust into eight rigorous weeks of rehearsals. Tech periods follow (where they set the lights and scenery) and Mike is on standby for ten hours a day. He does one warmup and waits around to perform his routine with cold, stiff limbs. Previews of the show are the last chance to work out any kinks in front of a live audience before opening night. At this point, Mike’s knees, which have had multiple injuries over the years, are killing him. What is he doing wrong?

Mike’s rehearsal period is brutal. However, there is something more insidious going on that deserves attention. He is dancing himself into shape! This is asking for trouble. While it is a useful adjunct for getting fit, the gym does not provide the speed, coordination, and timing of executing technical steps in dance class. His knees are the first things to hurt (owing to prior injuries), plus he is not staying warm during tech days. The challenge: to be in top physical shape before he gets a job, while preparing his body to perform at a moment’s notice with leg warmers and gentle warmup exercises.

The final scenario involves Sarah, who is in a modern dance company. Her days brim over with class, rehearsals, and performances that end at 11:00 P.M. She works hard, stays in shape, and does physical therapy exercises to prevent old injuries from recurring. Yet, in spite of being extremely conscientious, Sarah has begun to develop problems remembering new choreography. She is unaware of any personal concerns but often feels tired and takes frequent naps during the day. These help to revive her a bit for the next rehearsal. Sarah also makes sure to sleep at least seven hours per night but finds that during vacations her natural predilection is to sleep ten hours. What is she doing wrong?

Sarah’s problems with remembering new choreography are recent, suggesting that she does not have a learning disability. She also stays in shape (unlike Mike). The tipoff is that she sleeps more than seven hours during vacations. This defines her true need for sleep (not counting the first few days of a vacation when she’s working off her sleep debt). Dancing requires even more rest. As a result, Sarah is sleep-deprived, a problem that affects both her intellectual and her motor memory. The challenge: to get a sufficient amount of sleep during the season to enable her to perform up to her potential.

These cases highlight several of the many challenges that all dancers face. As you will see, some of the signs are subtle whereas others are more blatant. Regardless of the problem, it helps to be aware of the consequences and catch it early. Check out the following findings from NYCB’s research to find out if any apply to you.

Overwork and Fatigue

Most serious dancers have schedules that overwork them to one degree or another. This is an occupational hazard, and one a fit, healthy dancer—a dancer who has absorbed the principles of wellness outlined in this book—can usually sustain. However, at the time of our survey the performers at NYCB were like many dancers whose work patterns inadvertently undermine their goals. These patterns included (1) adding cross-conditioning to an already busy workweek and (2) jumping into a strenuous training schedule after a break without being in physical shape. In both cases, these habits led to an imbalance between physical exercise and the body’s ability to recover, creating extreme fatigue.

Why is it so bad for a dancer to drift into a fatigued state? Because it can lead to a host of problems (including burnout), according to dance medicine specialist Marijeanne Liederbach. For starters, chronic fatigue results in weaker muscles that are less able to protect your joints. It also takes a toll on your immune system. Besides prolonging the healing of injuries, excess fatigue increases the rate and severity of upper-respiratory infections, allergies, flulike illnesses, and one-day colds. Fatigue was a major cause of injuries in our survey. The good news is that it is possible to overcome the challenge of a busy dance schedule by practicing sensible work habits. NYCB dancers who paced themselves, like ballerina Yvonne Borree, were less likely to report fatigue or suffer health problems. “I would be injured if I went to the gym during the season,” she says. Yvonne does her cross-training only on company breaks.

The Insidious Impact of Mental Stress

Few dancers realize that constant worries, whether about the quality of one’s performance or about career, finances, or family, create another challenge to surmount. Yet the body’s response to chronic stress is similar to fatigue. In addition to compromising your immune response (yes, expect more colds), stress hormones make it difficult to concentrate or relax. At NYCB the most stressful event was learning new choreography, followed by a full load of rehearsals and performances. Ellen Bar, who was in the corps at the time of our survey, recalls the strain she felt performing a solo variation in Sleeping Beauty. “It’s a strenuous mental state because of the pressure to do well in a special role as well as whatever corps roles you have that night. You can’t really focus on just one thing. You know, you’re usually doing your [featured role] when you’re already exhausted.”

The dilemma for stressed-out dancers is that it is often difficult to stop worrying and get a good night’s sleep, thus adding to their problems. Besides interfering with the ability to learn and remember new steps, lack of sleep slows reaction time. It’s as if you had just polished off two martinis! It also affects your waistline. Professor Eve Van Cauter’s research at the University of Chicago shows that sleep deprivation influences appetite hormones, making you want to overeat by as much as 1,000 extra calories a day. Fortunately, our survey found that dancers who managed to rest and engage in stress-busting activities throughout the year, such as yoga or psychotherapy, experienced a reduction in emotional stress, better health, and more consistent performances.

Poor Nutrition: You Are What You Eat

NYCB’s initial survey revealed another finding that caught our attention: A number of female dancers had a significant delay in the onset of puberty compared to the general population, reaching menarche at fifteen years, against the population average of twelve and a half years. This was associated with a higher rate of stress fractures. Other dancers stopped menstruating for three or more months. Because nutrition can play a crucial role in menstrual problems, we developed a second questionnaire about food intake for all new dancers who entered the company. We learned that the dancers struggled with several issues when it came to eating, including poor time management, confusion about fad diets, and reliance on quick fixes like M&Ms for a sugar high that inevitably led to an energy crash.

Dancers need to eat for strength and energy, as well as to heal from injuries. This is why it is important to create a well-balanced meal plan to meet the athletic aspects of dance. While misconceptions about food and hydration are rampant among dancers, as well as in society at large, those who know about nutrition discover that food is an ally in their quest to excel. This was the case for principal dancer Ashley Bouder, who credits nutritional counseling with her ability to manage her weight without compromising her energy or health.

Costumes and Floors: The Occupational Hazards

The final challenge has to do with a dancer’s work environment, beginning with a floor that is neither too hard (as in linoleum on concrete) nor too bouncy. While floors have come a long way, with special products from companies like the American Harlequin Corporation (www.harlequinfloors.com), little things can still get in the way.

According to former production stage manager Perry Silvey, NYCB uses a resilient (or sprung) floor based on an internal basketweave wooden construction to absorb the shock of landing from a jump. Yet, while he is happy with this setup in the studio, the stage floor is harder than he would like because it must be able to support heavy scenery. The portable dance floor that the company brings on tour also cannot completely compensate for a hard or poorly constructed floor at another location, often causing shin splints, tendonitis, or stress fractures. (See Appendix B for injury definitions.) The vinyl covering (formerly called marley) can cause problems too. When the dancers use too much rosin on the soles of their shoes, it remains in clumps on the stage, making the cleaner areas feel slippery. This can lead to falls.

Awkward props, toe shoes, and costumes place additional stress on the body. NYCB soloist Adam Hendrickson had an unrecognized weakness in his back, which created problems when he had to perform somersaults over a drum. He addressed this injury in physical therapy to protect himself from future problems. Toe shoes cause a different problem for female dancers, who have a higher rate of foot injuries. Partly, this risk is due to the hypermobility (or loose joints) associated with a good pointe position. Dancing on toe adds to the risk of injury. Because you are balancing on a hard tip about the size of a silver dollar, it is easy to twist your foot if you slip. The solution is to be aware of this vulnerability, especially if you have had a previous ankle sprain, and strengthen the muscles around the joint to provide protection. The Pointe Book, listed in Appendix A, is an excellent resource for dancers who have questions about toe work. Heavy costumes also overload certain muscles; ankle-length brocade skirts can put a strain on the hips of dancers who are out of shape.

Awareness of this challenge is key. Dancers who back off from jumping on hard floors during rehearsals or address physical weaknesses with remedial exercises when faced with awkward props, toe shoes, and heavy costumes are less likely to falter even if they run through a blizzard of paper snowflakes. Now, if only they would use less rosin!

A Recipe for Injury

Put all these challenges together and you have an injury waiting to happen. While not all of them are under individual control, many are, and this book will help dancers take charge of those that are preventable. This is what happened to injured dancers Abi Stafford and Megan LeCrone, who learned the hard way how to gain control through NYCB’s wellness program.

Abi and Megan: From the Injury Trap to Recovery

Abi Stafford and Megan LeCrone both suffered foot injuries while rehearsing new choreography. For each of these women rehab, not surgery, was the treatment of choice, as the initial diagnostic tests showed relatively minor problems.

Abi’s hypermobile ankles made dancing in toe shoes precarious, as she found out after landing badly from a jump in The Nutcracker. “I have loose ankles, so rolling over is something I do often,” she recalls. “I’d just never done it this drastically.” The MRI, which shows soft-tissue damage like slices of a loaf of bread, revealed a grade 2 ankle sprain with a completely torn and a partially torn ligament. Abi was out of commission for six weeks, with several more weeks of physical therapy on the horizon before she could resume dancing.

Up until her injury, Abi’s career had seemed like a fairy tale. Promoted to soloist two years after joining the company, Abi had performed numerous ballerina roles, as well as winning the Martin E. Segal Award for her exemplary achievements as a young artist. She showed the same dedication during her rehab and tried to come back in the spring season, but her foot “didn’t feel right.” Dr. Hamilton and his partner, Dr. Phillip Bauman, ordered a second MRI with thinner slices. The results showed additional pathology that had been missed the first time, including a bone chip and a small defect in her ankle. It was a relief to finally have an answer to her pain and a plan of action. Her injury required arthroscopic surgery to drill and fill in the hole, just like a cavity in a tooth. Afterward, a cast and six weeks on crutches were necessary to let it heal.

Abi was forced to pace herself, particularly throughout her five months of rehabilitation, to regain motion and strength. Even when she felt as though she could push herself on pointe, her calf was not always ready. Abi had to be patient about getting back to a full class schedule. “My biggest regret is that I didn’t get the other MRI sooner to know if my ankle was really okay. Maybe part of it was that I didn’t want to know if there was another problem. I just wanted to get back to dancing. I was sort of in denial about it.”

The second dancer to experience the same frustrating recovery was corps member Megan LeCrone—only this happened almost as soon as she entered the company. She had been accepted into NYCB’s affiliated School of American Ballet three months before becoming a company apprentice, and she received her contract the following year. Megan then began to understudy a number of solo parts. She remembers thinking, “This is your chance to prove yourself. If someone goes out, you want to be prepared.” She worked all the time and found the process nerve-wracking. One of the challenges associated with injuries in our survey was mental strain. However, since high achievers tend to be under some level of mental strain all the time, it can be difficult to determine when you need to ask for emotional support.

By failing to get educated about her body, Megan was unaware that her vulnerable areas included loose ankles and tight calves. While this combination may sound strange, only about 15 percent of the company’s dancers are hypermobile in many joints, a condition known as benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS). It is more common to have a mix of both loose and tight joints, as well as muscle imbalances that affect the joints. Like so many other dancers, Megan ignored pain and fatigue and was not wary of having a recurring injury, even though she had suffered a grade 2 ankle sprain in her right foot as an apprentice. This time, as a full-fledged member of the company, she felt pain in the same foot but chose to dismiss it. The injury came during an evening performance and left her unable to dance. She was initially diagnosed with acute tendonitis from a strained flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon, which she was told would take a few weeks to heal.

Meanwhile, the MRI, which can often diagnose soft-tissue problems (CT scans focus on bones), revealed nothing serious. Because it continued to hurt, Megan had numerous tests over the next ten months, but only a diagnostic injection to temporarily numb the pain revealed a serious problem: a tear in the FHL tendon. In some cases, anesthetic injections are more effective than MRIs in making a correct diagnosis in tendons, especially now that doctors use ultrasound (sonography) to identify the exact location of the injury. The end result: Megan was headed for surgery, physical therapy, and much-needed sessions to manage mental stress. She also visited a nutritionist, who encouraged her to increase her protein intake to speed up her physical recovery.

All was well when Megan returned to dance six months after her surgery—until she slipped during a rehearsal doing a minor step. Her “bad” foot had been completely rehabilitated, but her left ankle, which was also hypermobile, suffered a grade 2 sprain (a torn ligament with some instability). After four months of rehab she went back to dancing, while stabilizing both joints with daily exercises that helped her withstand another slip in a pile of snow during a Nutcracker rehearsal. This time it was a grade 1+ (a partial tear of one ligament), which took five weeks to heal.

Megan’s biggest regret is her perfectionism. “I used to think, ‘If I just work harder than anyone else in the world, I can make it.’ Not true! If I had found a way to manage each stressful situation instead of trying to prove myself every day, maybe I wouldn’t have had such a big injury. It forced me to accept not being perfect.”

Fortunately, she says, “I learned a lot of things in the time I was injured that made me a better dancer.” Now she pays attention to her body and does daily remedial exercises. She also works on her perfectionism. “You have to let go of the stuff you can’t control—the casting or if a new, good dancer joins the company—because it doesn’t change you.” Needless to say, she is a lot less stressed.

These stories are not atypical as they encompass the many challenges faced by dancers, including overwork, mental strain, nutritional concerns, slippery floors, toe shoes, and the hazards of ungainly costumes and tricky sets. They also highlight the importance of knowing your body’s vulnerabilities.

Challenges are a fact of life in dance. Yet the more you know about your body’s weaknesses, the better equipped you are to pick up the warning signs before problems become serious. NYCB’s wellness program frees dancers to reach their potential as athletes and artists. Become proactive and you can overcome common challenges by taking a holistic approach to healthy dancing.

Highlights Revealed in Our NYCB Survey

• Ninety-six percent of the dancers reported an average history of four injuries.

• A heavy work schedule (more than five hours per day) was associated with new injuries due to fatigue.

• Women had more foot problems, whereas men had more knee and shoulder injuries.

• Poor physical conditioning during breaks predisposed dancers to new injuries.

• Mental strain from a variety of sources was a precursor to becoming injured.

• Dancers who stayed in shape and practiced stress management remained injury-free.