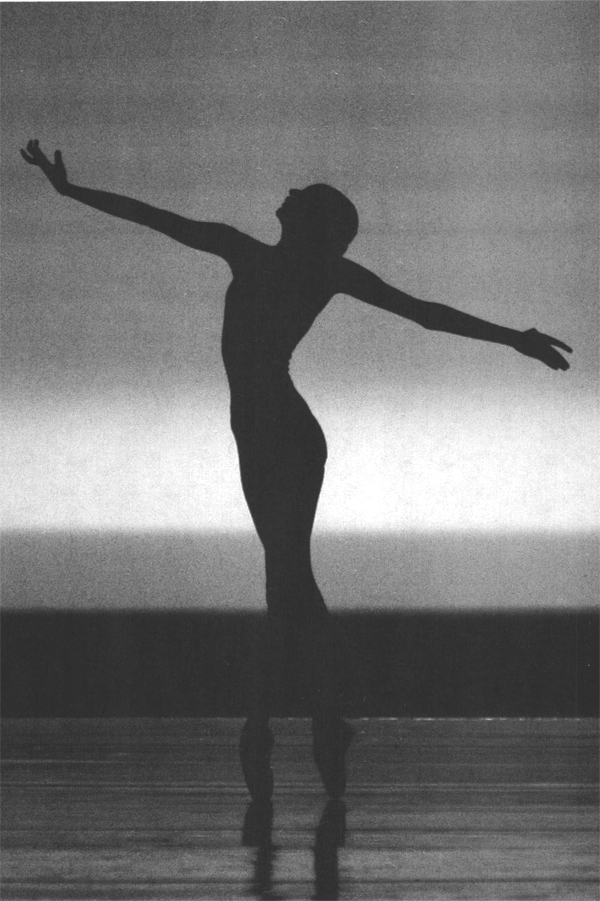

(Kaitlyn Gilliland in Eliot Feld’s Étoile Polaire)

A Holistic Approach to Healthy Dancing

Dancing requires a combination of everything—the right foods, physical conditioning, and a positive attitude.

—KAITLYN GILLILAND, NYCB corps

Overcoming the challenges in dance is critical to your health, well-being, and success. Unfortunately, many dancers learn this lesson only after they experience a serious problem. New York City Ballet corps member Kaitlyn Gilliland is a poster girl for changing her entire approach to dancing after fragmenting the articular knee cartilage on the joint’s surface at the age of seventeen. By using NYCB’s annual screenings and available resources, Kaitlyn not only recovered from her injury but, in spite of the low odds, went on to land a leading role in Eliot Feld’s Étoile Polaire. Though she was a fledgling apprentice, she got rave reviews and her photo in The New York Times. This chapter highlights ways to reduce the risks of a dancer’s life outlined in Chapter 2 by taking a holistic approach to healthy dancing, rather than having to troubleshoot major problems after the fact.

One leading dancer told me that he would have made fewer mistakes taking care of his body if there had been a handbook called Dancing for Dummies. Well, here is your handbook—although dancers are no dummies! You are smart, goal-oriented high achievers who want to fulfill your dreams. The road to healthy dancing begins with establishing a lifestyle that supports your goals, based on the pillars of wellness. You will then be ready to use the clear, easy-to-follow guidelines discussed in Part 2. Remember: Correcting problems is only one half of your arsenal of dance tools; the other half is living a healthy lifestyle.

The Pillars of Wellness

While many factors make up a healthy approach for dancers, the basic ingredients include education, coping skills, social support, and mind-body resources. These pillars of wellness, or foundations, will help you make wise choices in response to changing circumstances. For example, it’s smart to adjust your lifestyle to meet different needs during performances, breaks, and auditions. The same goes for taking your anatomy and stage of life into account. A final area that benefits from sensible decision making involves fatigue, burnout, illness, and injury. To see how to create a healthy lifestyle, check out the basic elements.

EDUCATION. Serious dancers are perpetual students who believe in lifelong learning—at least when it comes to technique. However, it pays to educate yourself about your body’s strengths and weaknesses by getting a physical screening. Ellen learned that the reason she could perform high kicks to the back was because she had loose joints. While this body type is an asset as a child (dance schools love flexible students), hypermobility makes you prone to injuries at the advanced level of training. The physical therapist who screened Ellen gave her special stability exercises to protect her joints. An annual screening can also pinpoint residual tightness or weakness from a prior injury, as well as help you improve your fitness level before starting a difficult season or dance program. The last pillar of wellness, mind-body resources, lists various specialists who can administer these tests. Additional educational sources, such as DVDs, are listed in Appendix A.

COPING SKILLS. It’s equally important to cope with the challenges in dance by using a range of mental skills to manage both physical and emotional stress, rather than resorting to self-destructive behaviors such as overwork or worse! Allen was alarmed when his personal stress barometer went through the roof after he was promoted to soloist. He had always been a talented dancer, yet he worried about whether he was “good enough” to perform leading roles. Most gifted people, including dancers, are perfectionists who often set unrealistic goals that are impossible to achieve. Keeping your expectations in perspective is essential. In Allen’s case, he counteracted his self-doubt by working with a cognitive-behavioral psychologist who taught him to set challenging but realistic goals, use positive self-talk to counteract his inner critic, and reframe his promotion in a more positive light (see it as an opportunity to grow as an artist). Further ways to reduce stress include balanced meals, aerobic exercise, and sufficient sleep (ten hours per night is ideal).

SOCIAL SUPPORT. Having positive people around you who support a healthy lifestyle is another pillar of wellness. Jackie never questioned her sensible eating habits until she entered a college dance program, where a group of students obsessed with being thin were living on coffee, cigarettes, and chocolate M&Ms. Realizing that she was starting to skip meals because she felt self-conscious around food, she switched to a different circle of friends, who knew that nutritious food revs up your metabolism and prevents binge eating. Social support also helps with other problematic behaviors, from smoking to substance abuse (see Chapter 4). Finally, having a group of friends can combat isolation and help prevent burnout, which is especially important on tour or if you live far away from your family. Dancers who find it difficult to reach out to others may benefit from joining community or religious centers or pursuing hobbies that bring them in contact with like-minded people.

MIND-BODY RESOURCES. A healthy lifestyle in dance depends on not only making the right choices but also having access to appropriate resources. Apart from working with a good dance teacher, these include:

• Rejuvenating activities, such as massage and acupuncture

• Medical, nutritional, and psychological services

• Cross-training sessions like yoga or Pilates

• Self-help information from books, Web sites, documentaries, etc.

Obviously, contact information is crucial. Miriam, who is a freelance dance teacher and performer, discovered that the International Association for Dance Medicine & Science’s Web site offered a variety of resources, ranging from fact sheets on nutrition to books referencing research papers on every topic in the field and an extensive summary of IADMS’s annual conferences. Dancers who want to locate a medical specialist in their geographic area can seek referrals from the executive director of IADMS, as well as the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, the American Physical Therapy Association, and the American Dietetic Association. The American Psychological Association provides referrals for mental health specialists. (Contact Web sites are listed in Appendix A.)

As you can see, creating a healthy lifestyle takes both time and money. A decent survival job can do wonders; however, you need to be prepared. Many dancers have gotten certificates to be aerobic instructors at health clubs by taking home-study courses from the American Council on Exercise. Others work at Starbucks, which provides health insurance for part-time employees, or make do by catering on the weekend. The resources section in the back lists additional sources for health insurance and medical providers that offer dancers a break.

Developing a Healthy Lifestyle That Works for You

As you can see, many factors go into creating a holistic approach to healthy dancing. At its core are the pillars of wellness. These include education, coping skills, social support, and resources for your mind and body that will be used throughout this book. Furthermore, NYCB’s proven screening protocol, outlined in the following section, can be used by a competent physical therapist or trainer to identify potential problems in all dancers. A general health, injury, and training questionnaire assesses basic parameters for dancers, combined with standard manual tests for orthopedic deficits, physical fitness, and hypermobility. Our nutritional evaluation is adapted for each dancer. Consequently, we offer general guidelines below, with considerable leeway for specific weight goals and preferences.

By helping dancers improve their overall conditioning while addressing any underlying mental or physical vulnerabilities, our wellness program emphasizes a healthy lifestyle. This includes counseling sessions and lectures given by the medical team. In my sessions I often focus on mental skills to help dancers cope with issues like performance anxiety, burnout, and stress management. In addition, the current company nutritionist, Joy Bauer, R.D., educates the dancers about ways “to keep their energy up and optimize their performance.” Although dancers who are not naturally thin may also need to monitor their weight, Bauer emphasizes, “they can still have incredible energy and maintain muscle mass.” Here is how this works.

The Orthopedic Screening

As you will learn in Chapter 5, recurring injuries, such as a sprained ankle, are common in the absence of sufficient rehab. Apart from examining the dancer’s general health, training, and injury history, the orthopedic screening picks up structural and functional deficits (see Appendix C). For example, dancers with poor turnout in their hips (a structural problem) may eke out a few more degrees in ballet positions that require external rotation by “rolling in” their feet and ankles. This situation puts excessive pressure on the lower leg, knee, hip, and back, often creating tendonitis (a functional problem). If left uncorrected, this habit can lead to an acute injury, such as a torn knee cartilage, when landing badly from a jump. Similarly, dancers with unequal turnout, pointe, or relevé may get into trouble by trying to make their “bad” side look exactly like the good one. A common case is the dancer with a poor pointe in one foot. Frequently, the hidden problem is an extra bone in the back of the ankle (known as an “os trigonum”). Forcing it to improve by sitting on your foot or hooking it under a piano leg (please say no to those tricks!) can lead to chronic pain that may require surgery. The remedy for most structural problems is to work within your physical limitations, preferably under the guidance of a physical therapist.

Other functional problems, including tight hamstrings, also benefit from physical therapy. The hamstring spans two joints (the hip and the knee), so it is used in almost every movement of the lower body. This area is more likely to be injured when it is tight, as a result of growth spurts, structural asymmetries, or muscle strength imbalances. A stretching regimen can prevent a serious injury in these instances.

Another correctable problem is the labral tear in the hip (similar to a torn knee cartilage). Before the advent of MRI with a special hip coil that diagnoses soft-tissue damage of the labrum, dance medicine specialists mistook this injury for iliopsoas tendonitis, or inflammation of the hip. Now they know that the labrum can tear and may result in pain and premature wearing out of the hip joint, leading to degenerative arthritis (and a potential hip replacement in the distant future) if left untreated. Interestingly, these injuries often occur in dancers with excellent turnout, due to shallow hip sockets that have a large acetabular labrum (hip cartilage), which stabilizes the joint by extending the rim of the hip socket.

The last aspect of the orthopedic screening focuses on common foot problems that require major TLC. For example, bunions, which are especially prevalent in women, affect as many as 53 percent of top-level professional ballet dancers. While a number of factors have been implicated, such as heredity and tight shoes, a bunion is not caused by dancing on pointe. The most persuasive explanation is a genetic predisposition. This is referred to as a “simian” foot. We recommend that the bunion-prone dancer wear wide shoes and a spacer between the big toe and second toe to keep it better aligned. Bunion surgery is not an option for dancers until retirement, because removing bunions can limit the motion in the joint and ruin the demi-pointe relevé. Your practitioner will help you identify areas that can be corrected by physical therapy. Remember, prevention is best, so try to get screened before an injury occurs.

The Physical Fitness Screening

As dancing has become increasingly athletic, the need to be physically fit increased as well. The fitness screening focuses on three areas crucial to physical performance: cardiovascular fitness, physical strength, and flexibility (see Appendix D). We also check for muscle imbalances, where opposing muscles are either too weak or too strong, and hypermobility, both of which can lead to injuries. We give each dancer feedback, remedial exercises if necessary, and an individualized workout program. According to a number of dancers, the exercises have helped to prevent serious injuries. Many thought they were strong in places where they were really weak.

For example, if you are prone to knee injuries because of weak quadriceps, then you would need to do strength training at the gym. Upper-body weakness might call for twenty-five daily push-ups. For dancers with hypermobile ankles, like Abi Stafford and Megan LeCrone, stabilization exercises to strengthen the muscles around the joint, such as relevés and working the peroneal tendons, are helpful (see here). Flexibility, which is less of a problem in dancers than athletes, can vary for different muscle groups, as well as between the right and left sides. Again, appropriate exercises are needed to prevent tightness that can lead to muscle pulls. The last component of fitness is aerobic capability. This is rarely developed in dancers (because the movement is episodic), even though a cardiovascular workout can reduce the onset of fatigue—a major cause of dance injuries. Because most dance classes are filled with stops and starts, 41 percent of our dancers who did not go to the gym needed to have additional exercises, like workouts on an elliptical machine. To increase stamina, during breaks in the performance season they do thirty minutes of aerobic activity at least three times a week, working at their target rate. (See Chapter 6.)

For dancers like Abi, aerobic exercises were a great way to get in shape after her surgery. In addition to frequent physical therapy, she says, “I rode the bike even with my boot on!” This is not dangerous; post-op patients frequently ride bikes in a protective boot. Megan also went to the gym and remembers that her first dance class after she returned felt like she had never been out.

The Hypermobility Screening

One of the fundamental physical requirements for a dancer is to have an extensive range of motion to perform the choreography. However, there is a fine line between being flexible and being hypermobile. Although hypermobility is an asset in the selection process of young dancers, it can be a liability for professionals.

The current way to identify hypermobility in different areas of the body is based on the revised Brighton criteria for benign joint hypermobility syndrome. Dancers who are born with this syndrome often have unstable joints everywhere, as well as minor symptoms, such as loose, stretchy skin. Dance training can also cause specific hypermobility in the knee or ankle. In either case, a hypermobile joint is prone to injury and osteoarthritis, owing to less stability, coordination, and proprioception. The goal of this screening is to strengthen hypermobile joints with physical therapy. (See Appendix E.)

The Nutrition Evaluation

Because of the importance of a lean body in the dance world, food issues are a touchy subject for many dancers. Both men and women need guidance about keeping their energy up with nutritious meals. However, male and female dancers usually have different goals when it comes to weight. In general, women are more concerned with how to lose weight, while the men often need to build muscle. Injured dancers can also use nutritional counseling. For example, Megan discovered that her daily intake lacked sufficient protein to promote the healing process.

Our wellness program requires all apprentices to get a nutrition evaluation with the goal of offsetting potential problems. Each person receives a brief questionnaire, including personal and family medical history (such as diabetes or food allergies), a three-day food log, and a blank page to describe past experiences with food and weight. The dancers use this last page to explain their present situation and goals for the future. They then meet with a registered dietician who has extensive experience with dancers. This health-care professional takes into account various lifestyle issues, such as whether the dancer cooks, has dietary restrictions, smokes cigarettes, or has a current or past history of eating disorders.

The goal, which varies depending on the individual dancer, may be to lose weight or to maintain sufficient energy to perform. In all cases, the dancer and nutritionist should settle on mutually agreed-upon food guidelines. Yo-yo dieting, characterized by undereating followed by bingeing, is addressed by adjusting caloric intake throughout the day and trying to remove problematic trigger foods from the dancer’s diet. Some dancers have trigger eating times, such as free days, which must also be dealt with. Liquid intake is important as well, because dancers who lose electrolytes and water from sweating need to stay well hydrated. While many foods, like cucumbers, have a high water content, drinking fluids, including water, is essential. Coffee in excess can be dehydrating, so try to drink water rather than six cups of Starbucks. NYCB soloist Ellen Bar admits, “It’s something I fight with because I hate drinking water. I make myself do it.” Hint: A squeeze of lemon juice adds flavor. Ideally, female dancers need to drink at least nine eight-ounce cups of fluids per day for moderate exercise, whereas male dancers require a minimum of thirteen eight-ounce cups. Certain liquids are better to drink before, during, and after dance, and one must know how to identify the rare but dangerous signs of overhydration.

To see how a screening profile works, take a look at the following results from one of the company’s apprentices, whom we shall call John.

Sample of Screening Profile

John is an eighteen-year-old NYCB apprentice. His first appointment was with Dr. William Hamilton, the company’s orthopedic consultant, for a general health and orthopedic screening. This twenty-minute evaluation, which included a questionnaire and physical exam, revealed a number of anatomical findings. John was knock-kneed and he had a poor relevé and insufficient turnout. In an effort to improve his fifth position, he forced his feet outward, causing him to roll in—a common problem in ballet. Fortunately he had not yet developed tendonitis or any other injuries from these habits, in spite of occasional pain.

Dr. Hamilton felt that John would benefit from a Pilates exercise program. This would strengthen the turnout muscles in his hips, while decreasing the tendency to roll over in his feet. He also referred John to the company’s physical therapists to improve his technique and placement. (Note: Talent, not a perfect body, got John into NYCB.)

Of course, physical fitness is another story. While John could do twenty-five push-ups in the blink of an eye, he was surprised to learn that his deltoids and abdominals were weak. NYCB chiropractor Dr. Lawrence DeMann recommended that he correct these deficits with light weights at the gym to avoid unwanted bulk, along with Pilates exercises. John’s fitness evaluation also showed physical therapist Marika Molnar that he needed to be in better cardio shape, given that his heart rate did not return to normal three minutes after jumping rope at high speed. The remedy was to use the elliptical machine three times a week for thirty minutes.

The good news: No problems were found for hypermobility or nutrition. A follow-up during the next season showed that John had followed the recommendations from his screening protocol and remained injury-free.

To conclude: By being willing to make a life change—to shift your approach to how you view your body and treat it—you can free yourself to become an artist. The pillars of wellness will provide a solid foundation for developing a holistic approach to healthy dancing. However, change is not an on-off switch. It is a process that requires overcoming roadblocks as you alter ingrained habits. This book will take you through this process as we navigate the road ahead.