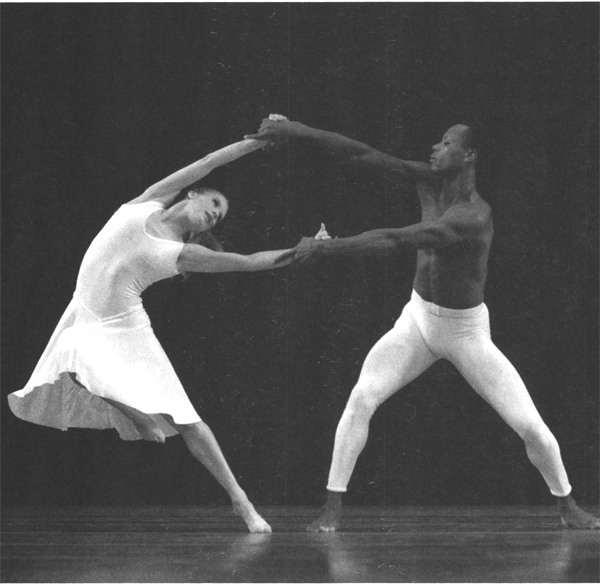

(Elizabeth Walker and Albert Evans in Peter Martins’s Barber Violin Concerto)

Keeping Your Eye on the End Goal

I’ve learned to keep my eye on the end goal. Even when I mess up, I try to let it go, and move ahead.

—ELIZABETH WALKER, NYCB corps

Did you know that only 40 percent of people who make a New Year’s resolution keep it? Whether it’s quitting a cigarette habit or eating more nutritious food, changing behavior is not an on-off switch. It is a multistage process where you may think about change, experiment with it, and go back and forth before you’re ready to take action. Slipping back into an old habit that is ingrained, pleasurable, or comforting is also normal. Consequently, switching gears is difficult for even the most highly driven, motivated dancer because it takes more than your own willpower to make change happen—it takes strategies. This chapter gives you the tools to understand and embrace the process of change, and survive the bumpy ride.

Correcting a problematic behavior or adopting a healthier one requires that you give yourself a break by having realistic expectations. (Hint: Perfection isn’t one of them.) This can be challenging for dancers who are used to being evaluated by how well they perform. Common stumbling blocks in dance include:

• Labeling yourself as “weak” if you have a problem, which may keep you from seeking help until you hit a major roadblock

• Clinging to unhealthy habits to manage your weight, strive for perfection, or reduce occupational stress

• Feeling superstitious about updating your training routine, such as adding aerobic workouts, because the old way (e.g., just dance class) worked in the past

• Being afraid to adopt a new behavior and fail, especially if you are a perfectionist who has tried and failed before

• Worrying that you’ll be given fewer opportunities by those in power if you seem to have problems

These obstacles are tied to losing face as a performer and a person. Former NYCB principal dancer James Fayette, who is now a union dance executive at the American Guild of Musical Artists, says, “I’ve been a victim of it myself. You want to focus on your strengths in dance [not what’s wrong] to avoid feeling tentative as a performer.” Still, he recognizes the benefits of stepping out of your comfort zone and taking advantage of the company’s wellness initiative. The question is, where do you begin?

Psychologists James Prochaska, John Norcross, and Carlo DiClemente have identified specific stages in everyone—not just dancers—associated with altering a wide variety of behaviors. To move forward, you need to use strategies that match where you are right now for your most pressing problem. Take the following self-quiz to locate your current stage, and note the tactics that will help you move to the next stage and eventually achieve your goal.

Self-Quiz: What’s Your Stage and Strategy for Change?

STAGE 1: You “don’t think” about changing your behavior.

STRATEGIES: Learn more about it; benefit from social supports, like smoke-free zones or low-fat menus.

STAGE 2: You “think” about making a change but do not have a specific plan.

STRATEGIES: Notice negative outcomes; see how your behavior clashes with your view of yourself.

STAGE 3: You “prepare to change” within thirty days, using a realistic plan and time line.

STRATEGIES: Add additional assistance (e.g., hotlines or therapy); use educational self-help tools.

STAGE 4: You’ve “taken action” in the last six months, but may have had a few slips.

STRATEGIES: Commit to change; reward good behavior; expand support network; respond differently to triggers; restructure environment (e.g., replace candy with fruit).

STAGE 5: You’ve consistently replaced an old habit with a new one for over six months.

STRATEGIES: Same as stage 4. Bravo!

Putting the Show on the Road

Now that you have a general idea of where you are on the change continuum, it is important to use the strategies that will foster movement to the next stage. Be aware that few people are ready to take immediate action. Instead, it is more common to move back and forth several times between stages 1 and 3, where change isn’t on your mind, you start to consider it, and eventually prepare a plan and time line to act within the next month. Focusing on two or three related behaviors, such as cardio, resistance training, and nutrition for healthy weight loss, will increase your chances of success. Trying to change more than three behaviors at once is counterproductive. Discover how the stages of change can work for you by following Carrie as she deals with her food cravings in a college dance program.

Stage 1: Precontemplation

Carrie is an emotional eater who uses candy and ice cream to cope with stress. After years of trying and failing to make better food choices, she feels hopeless about altering her behavior. Change is not on Carrie’s mind, even though she’s gained ten pounds. At this stage, the last thing Carrie wants to hear is practical advice about weight loss. Her mother’s well-intentioned efforts to try to force her to go on a diet also do more harm than good. Carrie feels coerced into changing her behavior and eats more junk food. What does help her think about change? A lecture on eating problems at her college raises her conscious awareness and shows Carrie how other dancers thrive after addressing this issue. A newsletter on the topic from the dance department also helps her to learn more about the problem. Another tool that increases her consciousness involves the following two exercises in her health education course. The first requires that she create a list of the reasons why making healthier food choices might be helpful. Carrie wrote:

1. “I’ll have more energy for dancing.”

2. “Adding fruit and vegetables to my diet will help me get back to a healthy weight.”

3. “I won’t feel sick from eating three candy bars right before dance class.”

In the second exercise, Carrie lists the reasons why she is not giving up junk food:

1. “I lack the willpower to change.”

2. “Chocolate helps me cope with pressure.”

3. “I want to have fun at the end of the day by eating ice cream.”

Carrie decides to talk to a friend who has dealt successfully with her own food issues (another way to learn more about this behavior). The fact that the college cafeteria provides tasty alternatives to junk food (social support) makes it easier to eat a healthy lunch once in a while, as she begins to think about changing her behavior. (Note: The only time it is appropriate to force a dancer to take action at stage 1 is when his or her health requires medical intervention, as in the case of someone with anorexia nervosa or serious substance abuse.)

Stage 2: Contemplation

Just thinking about giving up junk food represents a giant leap forward for Carrie. Yet mixed feelings also rear their ugly head now that she is beginning to weigh the pros and cons of change. While ambivalent feelings pop up throughout the different stages, they are at full strength during stage 2. It is easy to get stuck here indefinitely. After all, Carrie’s friends are giving her tons of positive reinforcement for her “good intentions,” while she is feeling self-righteous because someday she will eat healthy food. The strategies that helped her to acknowledge her problem continue to be useful (i.e., intellectual awareness; social support). However, Carrie needs a strategy to arouse her emotions. A health crisis serves as a wake-up call. After eating candy all day, which results in an energy high that drops precipitously, Carrie tears her knee cartilage in a dress rehearsal for the school’s choreographic workshop and has to sit out the performance. Arthroscopic surgery and six weeks of rehab hammer in the point. (Note: A personal crisis isn’t necessary to increase your emotional awareness, as long as some event arouses strong feelings about the need to change.)

As Carrie buys into the notion, intellectually and emotionally, that her eating has to change, she needs to use a different strategy to correct the mismatch between her thoughts and actions. She sees herself as a serious dancer who wants to be a professional in musical theater. However, her eating behavior conflicts with her self-concept and threatens her aspirations.

Carrie speaks to the school nurse, who tells her that she can control her cravings, but also alerts her that she needs to be well prepared because change isn’t easy. She asks her if there are any roadblocks standing in her way. Carrie thinks for a while and writes down three in her notebook, which she shares. These include:

1. “I don’t know where to start.”

2. “How do I deal with stress?”

3. “I know I can’t do it alone.”

The nurse is compassionate and understanding. She tells her that help is available at the campus counseling center, which is free for college students. (Professional dancers can also locate psychological services on a sliding scale by contacting the Dancers’ Resource program.) For the first time, Carrie is truly hopeful that she can change her eating problem. The nurse’s message of a brighter future, along with the reality that common discomforts accompany letting go of any problematic behavior, keep her from being blindsided by her fears. She makes an appointment with the therapist. Carrie is entering stage 3.

Stage 3: Preparation

At this stage, all kinds of options appear that Carrie either didn’t see or failed to recognize until she finally decided to change. The extent to which she remains determined, motivated, and hopeful will have a major impact on later decisions, such as setting a time line and developing a plan. She uses therapy to realistically visualize the future without using food as an emotional crutch as in the past. Carrie rehearses success by learning how to use a variety of therapeutic tools, like relaxation exercises, to manage stress. (See Chapter 9 for more details.) She develops the coping skills of a controlled eater who can deal with stressful dance auditions and performances. Mentally rehearsing successful outcomes helps her to see the light at the end of the tunnel even in the face of periodic relapses.

Carrie’s therapist also recommends further education and support in the preparation stage through online tools such as Overeaters Anonymous (www.overeatersanonymous.org), and self-help publications that focus on her health and eating problem. For example, she is able to get more information and help by logging on to OA and recognizing that others have the same problem that she does. In reading Life Without Ed (Ed=eating disorder), Carrie learns to treat her penchant for junk food as an abusive relationship from which she can eventually separate. All these strategies contribute to Carrie’s written plan. This includes starting the day with a relaxation exercise, planning her daily menu, logging onto OA daily for online meetings, and locking Ed in the closet (so to speak) when she has a yearning to deal with her emotions with a candy bar or ice cream.

By using one-on-one counseling, education, and other self-help materials, Carrie not only moves into the action stage but increases her chance of lifelong change. She has created a realistic plan and set a date to change her behavior in two weeks, after a birthday party where she might be tempted to have too much cake. Carrie chooses July Fourth because of its special meaning—Independence Day! Be aware that each plan is specific to the individual. While psychotherapy helped Carrie successfully move to stage 4, most people change without the benefit of a formal support program. The exceptions are serious health problems, such as eating disorders and substance abuse.

Stage 4: Action

The good news is that Carrie has finally arrived; the reality is that her new behavior can last anywhere from one day to six months. Two characteristics define the action stage for Carrie: conflict and turmoil. Her intellectual side is struggling for change using facts, logic, and reason, but her emotions are fighting just as hard to soothe herself with sweets. It takes considerable energy and conscious thought to change her old behavior, often leaving her completely exhausted. Her burning desire to succeed keeps her going, but she always has to be on guard. Carrie adds the following strategies to help her out.

First, she takes responsibility for changing her eating patterns by making a public commitment to her friends and family, which is more powerful than making a private commitment to herself. Second, Carrie rewards herself every time she makes a decision to avoid candy in the face of stress by having her nails manicured or getting a back massage. Third, she constantly restructures her environment by filling her pantry with healthy treats, such as low-fat string cheese, yogurt, grapes, figs, and a single serving of her favorite snack that she replenishes daily. To avoid feelings of deprivation, no food is off-limits. The key is moderation. Fourth, Carrie keeps a food diary, where she records her feelings. This tool helps her note when she’s vulnerable to emotional eating. (See Chapter 7 for a more detailed description.)

It is normal to relapse in the action stage. Carrie succumbs after auditioning for the lead role in a school production and feeling worthless after she isn’t chosen. Fortunately, her therapist teaches her how relapses provide an opportunity to learn ways to avoid triggering the same behavior in the future. Carrie discovers that she is extremely sensitive to rejection. In fact, anyone who goes in front of an audience is taking a special risk. Dancers need corrections, but they also require affirmation. She must address this issue if she wants a career in musical theater. Her therapist teaches her to “reframe” situations like an audition as learning experiences (a cognitive technique). No dancer can control the outcome. However, Carrie can control her performance by warming up, remembering the choreography, and smiling at the judges. That way she can’t lose. Carrie is graduating to the last stage.

Stage 5: Maintenance

It’s been over six months since sweets dominated Carrie’s life. Still, even though she is replacing her old habit with healthy eating, she worries about whether she can maintain this for the long haul. Carrie’s therapist reassures her that it’s both realistic and safer to be aware of possible pitfalls rather than being complacent. Her responses become automatic after a year of positive (or neutral) reactions to old triggers. While there are several sporadic incidents where she thinks of “sinful behavior,” she is in control 99 percent of the time by continuing to use all of her strategies. Carrie celebrates her accomplishment, shares her story with other struggling dancers, and creates a list of the benefits she’s had from healthy eating. She writes:

1. “I feel more confident as a dancer and a person.”

2. “My energy level is consistent, with no more sugar highs or lows.”

3. “I’m finally happy with my weight.”

4. “I love dancing even when it’s challenging.”

Now that Carrie is maintaining healthy eating, she begins to look at other changes that might improve her career. She decides to focus on taking more risks by pushing her technique, with the goal of performing at her peak.

What About Abi and Megan?

The two injured NYCB dancers whom we are following throughout this book had succumbed to serious injuries at the onset of promising careers. They came to psychotherapy for stress management through the company’s wellness program because they felt overwhelmed. Abi recalls, “I wasn’t prepared for this freak accident. Suddenly, I was out [unable to dance] and on crutches. I was sleeping all the time. And the more I slept, the more tired I got.” In contrast, Megan found herself struggling with mounting internal pressures to dance, even though her injury had yet to heal. Their dramatic injuries catapulted them to stage 3, where they made a plan to change how they coped with occupational stress, using cognitive-behavioral techniques like reframing their injury as an opportunity to cross-train and become a better dancer. They also focused on practicing good work habits that would protect them in the future, such as pacing themselves. Finally, Megan learned how to work with her perfectionism by setting more realistic goals. As you’ll see, taking a healthy approach to dancing improved their performance when they were back on their feet and being featured in principal roles.

Understanding how change works can help you address self-defeating behaviors and harness your potential in dance and in life. You can refer back to the different stages and strategies, as needed. Whenever you envision a change of behavior, the hardest battle is within. However, even when you backslide, you can use this experience to learn different ways to cope in the future. Remember: You double your chance of success when you move to the next stage!