The widening war, June 1941

It was fifteen minutes after four o’clock on the morning of 22 June 1941. At that moment, the German invasion of the Soviet Union began. In its first hours, German bombers struck at sixty-six Soviet aerodromes, destroying many of their aircraft on the ground. At the same time, five selected Soviet cities were subjected to aerial bombardment: Kovno, Minsk, Rovno, Odessa and Sevastopol. Yet more bombers struck at Libava, one of the principal Soviet naval bases in the Baltic. Then, as Soviet citizens woke up to the screech of bombs, the German Army began its advance along a 930-mile front.

June 21 was the shortest night of the year. It was also one year to the day since the French surrender at Compiègne. On that same day, 129 years earlier, Napoleon had crossed the River Neman in his own search for a victory in Moscow. At seven o’clock that morning, a proclamation by Hitler was read over the radio by Goebbels. ‘Weighed down with heavy cares,’ Hitler declared, ‘condemned to months of silence, I can at last speak freely—German people! At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen. I have decided again today to place the fate and future of the Reich and our people in the hands of our soldiers. May God aid us, especially in this fight’.

Fifteen minutes after Hitler’s proclamation was broadcast from Berlin, and with Stalin’s approval, Zhukov issued a directive authorizing Soviet troops to ‘attack the enemy and destroy him’ wherever the frontier had been crossed. But Soviet troops were ordered not to cross the frontier into Germany. Air strikes would be mounted against German positions, including Königsberg and Memel, but none to a depth greater than 150 kilometres behind the lines. Molotov was to broadcast at noon.

Was Stalin hoping to negotiate some kind of settlement or ceasefire? ‘Russians have asked Japan’, General Halder noted in his diary,’ to act as intermediaries in the political and economic relations between Russia and Germany, and are in constant radio contact with the German Foreign Office.’ ‘Only when it became clear that it was impossible to halt the enemy offensive by diplomatic action’, one Soviet historian, Karasev, has written, ‘was the Government announcement about the attack of Germany, and the start of war for the Soviet Union, made at noon’.

The Russians could not halt the forward march of the German armies. That day, south of Kovno, a crucial bridge at Alytus was captured intact, and the Neman river line turned without a battle. Some Russian units, Halder noted in his diary that day, ‘were captured quite unawares in their barracks, aircraft stood on the aerodromes secured by tarpaulin, and forward units, attacked by our troops, asked their Command what they should do’. At nine fifteen that night, Timoshenko issued his third directive in less than twenty-four hours, ordering all Soviet frontier forces to take the offensive, and to advance to a depth of between fifty and seventy-five miles inside the German border.

The tide of war could no longer be turned by a directive. By nightfall on June 22, the Germans had forced open a gap just north of Grodno between the Soviet North-Western front under Voroshilov, and the Western Front under Timoshenko. But not all observers took the German onslaught tragically. When news of the German attack on Russia had been broadcast over the German loudspeakers in Warsaw at four o’clock that aftermoon, the Jews in the ghetto, as one of them, Alexander Donat, later recalled, were trying ‘unsuccessfully’ to hide their smiles. ‘With Russia on our side,’ they felt, ‘victory was certain and the end for Hitler was near.’

The confidence of the Jews who were trapped, and starving, in Warsaw had a curious echo in the mood in Berlin. ‘We must win, and quickly,’ Goebbels wrote in his diary on June 23. ‘The public mood is one of slight depression. The nation wants peace, though not at the price of defeat, but every new theatre of operations brings worry and concern.’

Hitler, leaving Berlin that day for a new headquarters, the Wolf’s Lair, near Rastenburg in East Prussia, told General Jodl: ‘We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down’. But even Hitler’s confidence was not unqualified. ‘At the beginning of each campaign,’ he told one of his staff later that day, ‘one pushes a door into a dark, unseen room. One can never know what is hiding inside.’

By noon on June 22, the German Air Force had destroyed more than a thousand Soviet aircraft on the ground or in combat: a quarter of Russia’s whole air strength. That day, both Italy and Roumania declared war on the Soviet Union.

By nightfall on June 22, the Germans had overrun the Fortress Area towns of Kobryn and Pruzhany. On the following day, in Moscow, an Evacuation Council was set up, with Alexei Kosygin as one of its three members, to organize the dismantling, removal and reassembly of more than 1,500 armament factories and industrial plants in Western Russia and the Ukraine, to safety in the East. Beyond the Urals, far from any probable or even possible battle zone, in distant cities such as Sverdlovsk, Kurgan and Chelyabinsk, in Siberia, and in Kazakhstan, the Soviet Union, in its very moment of shock and weakness, was rebuilding the basis of a massive war potential.

Within the first few days of the German assault, it was clear that it was not only to be a war of armies. When, in the bunkers around the frontier village of Slochy, on the border, a German Army unit finally overran the Russian defenders, it then burned down the village and murdered all hundred of its inhabitants. On June 25, General Lemelsen, commanding the 47th Panzer Corps, protested to his subordinate officers about what he called the ‘senseless shootings of both prisoners-of-war and civilians’ which had taken place. His protest was ignored.

The widening war, June 1941

Lemelsen renewed his protest five days later, declaring in a further order that, in spite of his earlier instructions, ‘still more shootings of prisoners-of-war and deserters have been observed, conducted in an irresponsible, senseless and criminal manner. This is murder! The German Army is waging war against Bolshevism, not against the Russian peoples.’ Yet General Lemelsen went on to endorse Hitler’s order that all those identified as political commissars and partisans ‘should be taken aside and shot’. Only by this means, he explained, could the Russian people be liberated ‘from the oppression of a Jewish and criminal group’.

On the field of battle, the last week of June saw continual Soviet setbacks. On June 25 two generals, Khatskilevich and Nikitin, were killed in action. Several strategic towns were also lost that day, including the railway junctions of Baranowicze and Lida in the north, and Dubno in the centre. Goebbels however was cautious. ‘I am refraining from publishing big maps of Russia,’ he noted that day in his diary. ‘The huge areas involved may frighten the public.’

From the first days of the German advance, Jews were as usual singled out for particular and systematic destruction. When, on June 25, German forces entered Lutsk, and found in the hospital there a Jewish doctor, Benjamin From, operating on a Christian woman, they at once ordered him to stop the operation. He refused, whereupon they dragged him from the hospital, took him to his home, and killed him with his entire family.

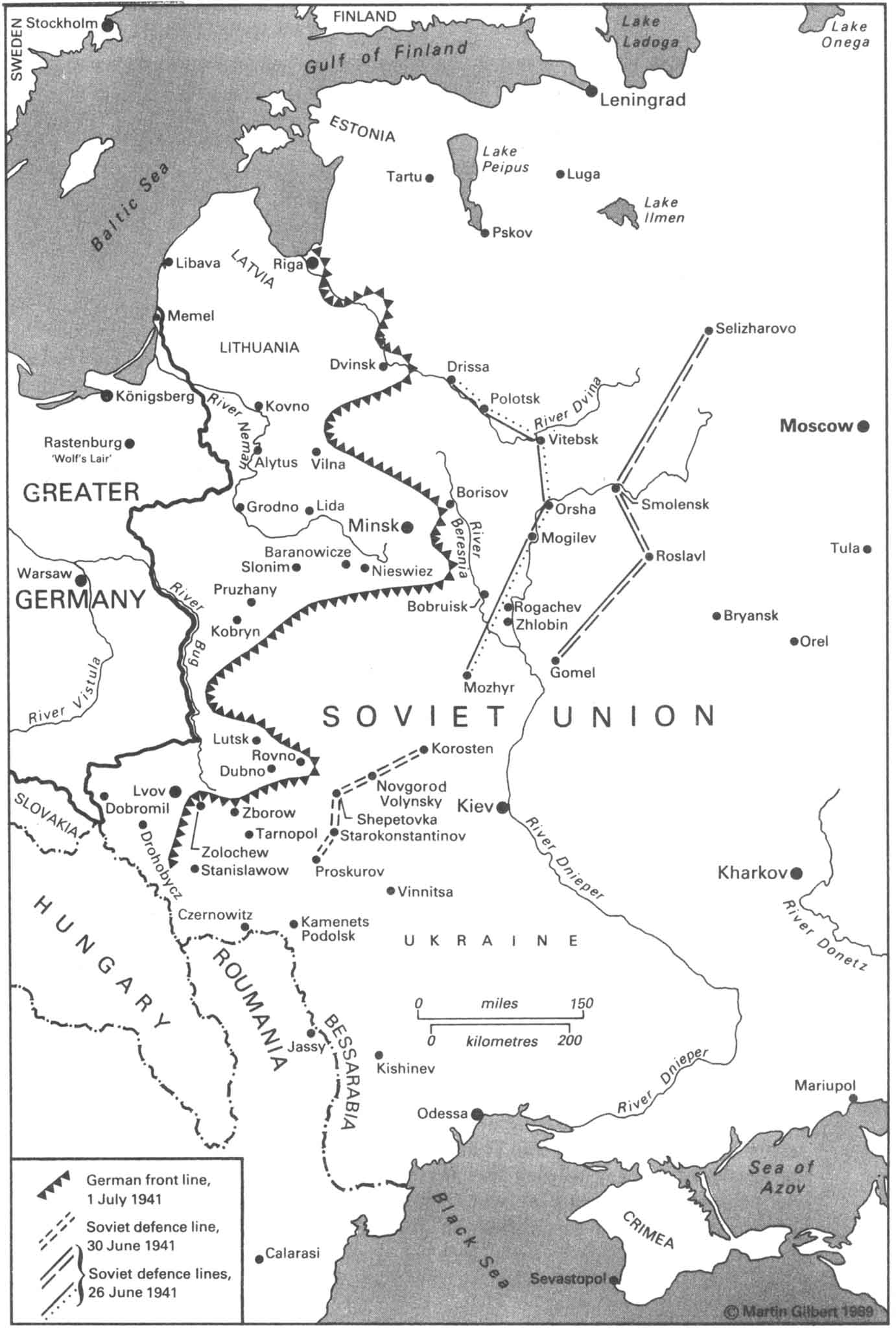

On the morning of June 26, German forces reached the city of Dvinsk, seizing both the road and rail bridges across the River Dvina. This was a remarkable success, similar to the seizure of Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium little more than a year earlier. The German Army was now 185 miles inside the Soviet border. Later that day, Finland declared war on the Soviet Union, while in Verona, Mussolini reviewed an Italian division that was about to leave Italy in order to fight alongside the Germans inside Russia. That night, having flown back to Moscow from the South-Western Army’s headquarters at Tarnopol, Zhukov obtained Stalin’s approval to set up an emergency defence system on the line Drissa—Polotsk—Vitebsk—Orsha—Mogilev—Mozyr, together with an even more easterly line on the axis Selizharovo—Smolensk—Roslavl—Gomel. A glance at the map shows how far both Zhukov and Stalin realized that their forces must in due course fall back. ‘Where the enemy could be stopped,’ Zhukov later recalled, ‘what should be the advantageous line for the counter-offensive, and what forces could be mustered, we did not know.’ That day, also in Moscow, Lavrenti Beria, the People’s Commissar of the Bureau of Internal Affairs—the NKVD—ordered all his regional NKVD organizations in western Russia to form special home defence units, known as Destruction Battalions, to guard important installations behind the lines, to prevent sabotage, and to counter any German parachute landings. These battalions, one to two hundred strong, were made up mostly of men too old, too young or not physically fit enough to join the ranks of the Red Army.

On June 27 all civilian building work in Leningrad was brought to a halt, and 30,000 building workers and their equipment transferred out of the city, in the direction of Luga, to dig anti-tank ditches and to build reinforced fire-points from concrete blocks. That day, Marshal Mannerheim appealed to the people of Finland to play their part in the ‘holy war’ against Russia. It was proving a far from easy war, however, even for the SS Death’s Head Division, which was astonished on June 27 by a succession of Russian counter-attacks, first with tanks and then, when the tanks had been knocked out, on foot. There was also fear among the SS troops at the many groups of Soviet soldiers who, isolated far behind the front line, consistently fought to the death rather than surrender. Orders were given that such stragglers should be dealt with ruthlessly. These orders were obeyed; after the first few encounters, those met with were usually shot even if they had not yet offered any resistance.

The German invasion of Russia, 22 June 1941

Not only Soviet stragglers, but organized Soviet partisans, were soon to make their appearance behind the German lines. On June 27, Nikita Khrushchev gave instructions for small partisan detachments of between ten and twenty men to be organized in Kamenets-Podolsk. More than 140 small groups were also set up by the local Communist Party authorities in the Lvov, Tarnopol, Stanislawow, Czernowitz and Rovno regions, about two thousand men in all. Once organized, they were slipped through the German lines into enemy-occupied territory.

It was on June 27 that Hungary declared war on the Soviet Union, followed a day later by Albania. Russia was now at war with five states—Germany, Finland, Roumania, Hungary and Albania. On June 27, at Bletchley, British cryptographers broke the Enigma key being used by the German Army on the Eastern Front. Known as ‘Vulture’, it provided daily readings of German military orders. On the following day, Churchill gave instructions that Stalin was to be given this precious Intelligence, provided its source could remain a secret. An officer in British Military Intelligence, Cecil Barclay, who knew of the work at Bletchley, and who was then serving in the British Embassy in Moscow, was instructed to pass on warnings of German moves and intentions to the head of Soviet Military Intelligence.

Despite being well informed of the German moves against them, Stalin and his commanders did not have the resources to counter these moves, or to resist the savagery with which they were conducted. On June 27 two German panzer groups, linking forces east of Minsk, turned against the 300,000 Russian troops caught in the trap, 50,000 of them in Minsk itself. In the ensuing battle, tens of thousands were killed. Almost all the rest were taken prisoner. Their fate was to be terrible: beaten, starved, denied medical attention, refused adequate shelter, shot down if they stumbled during endless forced marches, few of them were still alive a year later.

That day, June 27, in the village of Nieswiez, a young Jew, Shalom Cholawski watched horrified as a German soldier began punching a Soviet prisoner. ‘The prisoner,’ he later recalled, ‘a short fellow with dull Mongolian features, did not know why the German had singled him out or what he was raving about. He stood there, not resisting the blows. Suddenly, he lifted his hand, and with a terrific sweep, slapped his attacker powerfully and squarely on the cheek. Blood trickled down the German’s face. For a moment they stared at each other, one man seething with anger, the other calm. Several Germans brusquely shoved the man to a place behind the fence. A volley of shots echoed in the air.’

***

In an effort to counter the effect on Russian morale of the rapid German advance, on June 28 posters were put up in Leningrad, showing a photograph of the German deserter, Alfred Liskof, with the caption: ‘A mood of depression rules among German soldiers’. But the advance of those German soldiers, and their growing number of allies, was continuous. On June 28 German troops advancing from Norway and Finnish troops coming from Finland attacked the Russians in Karelia. That same day, on the Minsk front, the advancing German units were already one third of the way from the German border to Moscow, in only one week of war.

The Red Army was not however without resources, or at least without courage and ingenuity. On June 29 the SS Death’s Head Division was caught unawares by the appearance of Soviet fighter planes which, strafing the SS positions, killed ten men. General Halder, studying reports from the whole battlefield, noted in his diary: ‘Information from the Front confirms that the Russians are generally fighting to the last man.’ In the Grodno area, he was told by General Ott, the Russians were showing ‘stiff resistance’. In the Lvov area ‘the enemy is slowly retreating, putting up a tough fight for the last line’. Here, Halder added, ‘for the first time, mass destruction of bridges by the enemy can be observed’. The Russian soldier, the Nazi Party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter reported on June 29, ‘surpasses our adversary in the West in his contempt for death. Endurance and fatalism make him hold out until he is blown up with his trench, or falls in hand-to-hand fighting’.

It was on June 29 that a general directive was issued from Moscow. Before the Red Army withdrew from a town, the directive made clear, rolling stock and other moveable items, even food, must be removed, ‘leaving the enemy not a single locomotive, not a truck, not a loaf of bread, not a litre of fuel’. Cattle must be driven to the rear; and any food or fuel which could not be removed ‘must, without any exceptions, be destroyed’. Such was the scorched-earth policy; the directive also laid down the rules for partisan activities behind the lines, the task of the partisans being defined as ‘blowing up bridges, railway tracks, destroying enemy telephone and telegraph communications, blowing up enemy ammunition dumps’. That same day, the Leningrad authorities began a week-long evacuation of 212,209 children, mostly to Yaroslavl, on the Volga.

On June 29, as German forces drove through what had once been the eastern provinces of Poland, the first Prime Minister of Poland, the pianist Paderewski, died in the United States, at the age of eighty. President Roosevelt at once offered Arlington Cemetery as his coffin’s resting place ‘until Poland is free’. Paderewski’s lead-sealed casket, inside a cedarwood box, mounted on wheels for its journey back to Poland, is still at Arlington forty-seven years later.

***

On the night of June 29, the city of Lvov, capital of Eastern Galicia, fell to the Germans in what one historian has called ‘a nightmare of carnage and chaos’, beginning with a massacre of three thousand Ukrainian political prisoners by the NKVD. Hardly had the Russian troops withdrawn, some having to break out of an encircled city, when Ukrainian nationalists began slaughtering Jews in the streets. Further south, in the Roumanian city of Jassy, Roumanian soldiers went on the rampage, killing at least 250 Jews; a further 1,194 died after being sealed in a train and sent southward for eight days.

These were not the first Jews to be murdered in the latest onslaught. Three days earlier, within forty-eight hours of German troops entering Kovno, local Lithuanians had turned on some of the city’s 35,000 Jewish inhabitants, killing more than a thousand.

On June 30, in the Borisov region, on the east bank of the Beresina river, the thirty-six-year-old Soviet general, Jakov Kreiser, a Jew, commanding a motorized infantry division, halted an attack of Guderian’s tanks for two days. As he did so, Soviet reinforcements were being hurried forward to the Drissa—Mozyr line. Later, in recognition of his achievement, Kreiser was awarded the coveted Hero of the Soviet Union. To the south of Borisov, however, after capturing the town of Bobruisk, German forces established a bridgehead across the Beresina.

Each Soviet city, each town, each village, was to honour its heroes and its victims of those first weeks of war. Leningrad, for example, remembers to this day its first writer to fall in action, Lev Kantorovich, the member of a border detachment, killed on June 30. Even as Russians were being killed in action, the Commissar Decree was leading to hundreds of deaths each day in cold blood. It was on 30 June that the twenty-one-year-old SS officer cadet, Peter Neumann was told by his lieutenant to shoot two commissars whom his unit had just captured in a small village outside Lvov. When Neumann hesitated, the task was handed over to SS Lance-Corporal Libesis, ‘a cheerful Tyrolean peasant’, Neumann later recalled, ‘who had twice won the Iron Cross in battle’, and Libesis, ‘quietly, casually, as if he had all the time in the world, approached the commissars’. ‘You are a People’s Commissar?’ he asked, in simple Russian. ‘Yes. Why?’ they replied. Libesis then took his pistol from his holster, ‘aimed at each shaven head in turn, and shot them both dead.’

***

The cohorts and collaborators of the Germans did their own killing. It was not only Ukrainians and Lithuanians who had begun to kill Jews; in Norway, Josef Terboven ordered the round-up of all Jews in Tromsö and the northern provinces. They were deported to Germany. Other Jews, arrested in Trondheim, were shot. From Holland, on 30 June, another three hundred young Jews were rounded up and deported to the stone quarries of Mauthausen. ‘They followed the same stony path,’ one Dutch witness of their deportation later recalled. ‘Nobody survived.’

***

On June 30, the Australians lost their first warship to be destroyed by enemy action, the Waterhen, struck by German dive bombers off Sidi Barrani while on its way with supplies to besieged Tobruk. Not only was the ship’s company saved by a British destroyer, but the Australian loss was quickly revenged, when a Royal Australian Navy cruiser, the Sydney, sank the Italian cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni.

***

As the German Army continued its relentless thrust into western Russia on June 30, General Kirponos ordered a Soviet withdrawal from the Lvov salient to a new defensive line, Korosten—Novgorod—Shepetovka—Starokonstantinov—Proskurov. This line was reached by July 9, while behind it reinforcements were brought up.

Despite heavy Soviet losses, the Soviet front line had not disintegrated. In the far north, on July 1, the Germans launched two further military operations, Silver Fox, against the Soviet Arctic port of Murmansk, and Salmon Trap, against the railway line between Kandalaksha and Belomorsk. At the same time, the Finnish Army advanced eastward from central Finland. Hurrying reinforcements northwards, the Russians were able to hold their northern lifeline: the German troops had not been trained in forest warfare, and the Russian resistance, as in western Russia, surprised their adversaries by its tenacity.

It was in western Russia, on July 1, that a Russian counter-attack east of Slonim penetrated the German encirclement of two severely mauled Russian tank brigades, enabling the remnants to escape.

On the night of July 1, a train made up of twenty-two goods wagons and two passenger cars left Leningrad for the east; on board, under the vigilant eye of the art scholar Vladimir Levinson-Lessing, were some of the finest treasures of the Hermitage: Rembrandt’s Holy Family and the Return of the Prodigal, two Madonnas by Leonardo da Vinci and two by Raphael, as well as paintings by Titian, Giorgione, Rubens, Murillo, Van Dyck, Velasquez and El Greco. Also on the train was a marble Venus acquired by Peter the Great, Rastrelli’s sculpture of Peter, the museum’s Pallas Athena, and its superb collection of diamonds, precious stones, crown jewels and ancient artefacts of gold.

Nearer to the front, at Mogilev, July 1 saw two Soviet Marshals, Voroshilov and Shaposhnikov, briefing those who were to stay behind as the Germans advanced, and set up partisan groups. ‘Blow up bridges,’ they were told, ‘destroy single trucks with enemy officers and soldiers. Use any opportunity to slow up the movement of enemy reserves to the Front. Blow up enemy trains full of troops, equipment or weapons. Blow up his bases and dumps.’

On July 1, the Germans entered Riga. In Berlin, Ribbentrop urged the Japanese to enter the war at once, and to strike at the Soviet Union in the Far East. The Japanese refused to do so, the news of their refusal, and of their decision to push instead into French Indo-China, being radioed from Tokyo to Moscow by Richard Sorge on July 6. As a result of this Intelligence, Soviet troops from the Far East could continue to reinforce the armies battling in the West. Reinforcements were urgently needed; on July 2 the Roumanian Army, having watched the German forces advancing for eleven days, had attacked in the south, striking in the direction of the Ukrainian city of Vinnitsa.

This new onslaught made even more urgent the evacuation of factories from southern Russia. On July 2 it was decided to move the armoured-plate mill at Mariupol to the Ural city of Magnitogorsk. On the following day, the State Defence Committee in Moscow ordered the transfer eastward of twenty-six further armaments factories from throughout western Russia, including Moscow, Leningrad and Tula. From Kiev and Kharkov too, individual plants and essential machinery were ordered eastward.

On July 3, Stalin broadcast, for the first time since the invasion twelve days before, to the Russian people. ‘A grave threat hangs over our country,’ he warned, and he went on to tell his listeners: ‘Military tribunals will pass summary judgement on any who fail in our defence, whether through panic or treachery, regardless of their position or their rank.’

Stalin’s speech contained a powerful appeal, not to Communism but to patriotism. He addressed his listeners, in his opening words, not only as ‘comrades’ and ‘citizens’, but also as ‘brothers and sisters’ and ‘my friends’. In one passage, he appealed for the formation of partisan units behind the lines ‘to foment guerrilla warfare everywhere, to blow up bridges and roads, damage telephone and telegraph lines, set fire to forests, stores, transports’. The enemy, ‘and all his accomplices,’ must be ‘hounded and annihilated at every step’.

The Germans failed to appreciate the storm which such an injunction was to raise against them. ‘It is no exaggeration to say’, wrote General Halder in his diary on July 3, ‘that the campaign against Russia has been won in fourteen days.’ Behind the lines, the cruelty was beginning to exceed all previous cruelty in this or any other war. On July 4 one of Himmler’s Special Task Forces recorded the murder of 463 Jews in Kovno; two days later a further 2,514 were killed. In Tarnopol, within forty-eight hours of the German occupation, six hundred Jews had been killed, and in Zborow a further six hundred. In Vilna, fifty-four Jews were shot on July 4 and a further ninety-three on the following day.

On July 5, the part played in these massacres by Lithuanians was raised at Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia by a German Army officer. In Kovno, according to a report by the Special Task Forces, 2,500 Jews had been killed by the Lithuanians before the Germans had even occupied the city. German soldiers, Hitler’s adjutant Colonel Schmundt, replied, were not to interfere in these ‘political questions’; what was happening to the Jews was part of ‘a necessary mopping up operation’. Hitler himself was confident of victory; that day, to his private staff, he spoke of making the ‘beauties of the Crimea’ accessible by autobahn from Germany: ‘for us Germans, that will be our Riviera’. Croatia too, he said, would be ‘a tourists’ paradise for us’. In Russia, it was enough ‘for the present’ for the Urals to be the new Eastern frontier. ‘What matters,’ Hitler explained, ‘is that Bolshevism must be exterminated. In case of necessity, we shall renew our advance wherever a new centre of resistance is formed.’ Moscow, he added, ‘as the centre of the doctrine, must disappear from the earth’s surface, as soon as its riches have been brought to shelter’.

Those who were determined to prevent such an outcome to the war redoubled their efforts that July. From London, plans were made to send military and medical aid to the Soviet Union on a substantial scale, even diverting American aid—then on its way to Britain—from British to Soviet ports. In the air, the attacks on Germany continued, despite a considerable improvement in the German air defences. In a bombing raid on Bremen on July 4, five out of the twelve attacking aircraft had been shot down. For his bravery in persevering with the raid, and in bringing the survivors home, the leader of the raid, the Australian pilot Hughie Edwards, was awarded the Victoria Cross. More than a thousand miles to the south, on July 5 the Yugoslav Communist partisan, Tito, issued an appeal to his fellow Yugoslavs. ‘Now is the time,’ he declared, ‘the hour has struck to rise like one man in the battle against the invaders and hirelings’. On the following day, Tito sent a Montenegrin student, Milovan Djilas, to his native province, to organize resistance against the German occupation forces. Tito told Djilas: ‘Shoot anyone if he wavers or shows any lack of courage or discipline!’

On July 7, at the Serbian village of Bela Crkva, the first armed clash took place between a small Communist detachment and the German police. Two policemen were killed.

Plans for resistance went forward, slowly, in many lands; but the German advance into Russia struck fear into all the captive peoples. On July 6, on the Leningrad front, German troops reached Tartu, less than two hundred miles from the former Imperial capital. But in the German High Command it was the repeated ability of the Russians to counter-attack that was causing alarm. ‘Everyone’ at headquarters, Halder noted in his diary, ‘is vying for the honour of telling the most hair-raising tales about the strength of the Russian forces.’ On July 6, two German divisions had been driven back from Zhlobin. A panzer attempt to breach Stalin’s first defence line at Rogachev, had been repulsed. There was evidence of Soviet reinforcements being brought up in force to Orel and Bryansk.

Early in July, British Intelligence learned from the German Army’s Enigma messages that the Germans were reading certain Russian Air Force codes in the Leningrad area, as well as decrypting Russian naval messages in the Baltic. This information was passed on to the British Military Mission in Moscow on July 7, with the request that the Russians be alerted to this gap in their security. That day, in the Atlantic, the United States launched Operation Indigo, the landing of a Marine brigade in Iceland. To the American people, Roosevelt justified the operation in terms of the need to defend the Western hemisphere; but for Britain’s transatlantic shipping it was an important contribution to seaborne traffic nearer home. Roosevelt himself, four days later, on a map torn out of the National Geographical Magazine, marked the new eastward extension of American patrols in the Atlantic; those patrols now came to within four hundred miles of the northern coast of Scotland.

American support was enabling Britain to extend her own support for Russia. On July 7, the day on which the American Marines landed on Iceland, Churchill wrote to Stalin to say that Britain would do ‘everything to help you that time, geography, and our growing resources allow’. British bombing raids on Germany, Churchill explained, which had recently been intensified, would go on: ‘Thus we hope to force Hitler to bring back some of his air power to the West and gradually take some of the strain off you.’ On the day of this telegram to Stalin, Churchill instructed the Chief of the British Air Staff to use Britain’s air resources for the ‘devastation of the German cities’ in an effort to draw German aircraft back from the Russian front.

***

On July 8, German forces entered Pskov, a mere 180 miles from Leningrad. That same day, in pursuance of his stern words of five days earlier, Stalin removed General Korbokov from his command; accused of ‘permitting the destruction of his army by the Germans’, Korbokov was shot. On the day of the capture of Pskov, at Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters at Rastenburg, General Halder noted in his diary: ‘Führer is firmly determined to level Moscow and Leningrad to the ground, and to dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.’

Hitler seemed to have cause for his confident bellicose assertions; on July 9 he learned that 287,704 Soviet soldiers had been taken prisoner, and 2,585 Soviet tanks destroyed, in the salient west of Minsk, where ‘mopping up’ operations came to an end that day. But, in every area overrun by German troops, partisan units were formed; some, like one set up by Colonel Nichiporovich, were created out of the remnants of fighting units which had been almost totally destroyed. Further north, as the Red Army withdrew along the road between Pskov and Luga, one partisan commander, Dudin by name, having spent ten days collecting 123 rifles and two light machine guns from Soviet units pulling back, ‘went over’, as he reported, ‘to the position of a partisan detachment, taking refuge with the population in the woods’. On July 9, Dudin carried out his first action behind the lines; within two months he had destroyed more than twenty German lorries, and killed 120 Germans, ‘not counting those accounted for by the Red Army on the basis of information we gave’.

Information was a key to survival; on July 9 a group of British cryptanalysts broke the Enigma key used by the German Army to direct its ground—air operations on the Eastern Front. But good Intelligence could seldom make up for a serious lack of weapons. On July 10, when the first division of volunteers left Leningrad for the ever encroaching front line, there were not enough rifles to go round. While each man had been given hand grenades and Molotov cocktails, many without rifles carried picks, shovels, axes and even hunting knives instead. That same day, at Korosten, a massive Soviet counter-attack in defence of Kiev was checked, and then driven back. ‘He is infinitely confident of victory,’ Walther Hewel wrote of Hitler, after seeing him at Rastenburg on July 10. ‘The tasks confronting him today are as nothing, he says, compared with those in the years of struggle, particularly since ours is the biggest and finest army in the world.’

Hitler also spoke to Hewel on July 10 about the Jews. ‘It is I’, he said, ‘who have discovered the Jews as the bacillus and ferment that causes all decay in society. And what I have proved is this—that nations can survive without Jews; that the economy, culture, art and so on, can exist without Jews and in fact better. That is the cruellest blow I have dealt the Jews.’

Crueller blows were, in fact, being dealt against the Jews daily, as German forces occupied areas with large Jewish populations, totalling more than a million Jews. On July 7, it was reported eleven days later from Berlin, 1,150 Jews had been shot in Dvinsk, ‘without ceremony, and interred in previously prepared graves’. In Lvov, 7,000 Jews had been ‘rounded up and shot’. In Dobromil, 132 Jews had been killed. In Lutsk, three hundred Jews had been shot on June 30 and a further 1,160 on July 2. At Tarnopol, 180 Jews were killed. At Zolochew ‘the number of the Jews liquidated may run to about 300–500’.

Such reports, marked ‘top secret’, were compiled every few days; merely to print them in full would be a book itself, as large as this one. Not only Jews, but former Soviet officials and local dignitaries were executed in large numbers in every town and village overrun by the German Army. Soviet prisoners-of-war also continued to be the victims of deliberate barbarity from the first moments of their captivity; on 10 July information reached Berlin of the terrible conditions in the newly opened prisoner-of-war camp of Maly Trostenets, just outside Minsk, where hundreds of Soviet soldiers in captivity were dying every day from disease, starvation and the brutality of their guards.

***

The Red Army was determined to fight for every mile of the road to Moscow. ‘The enemy Command is acting ably,’ General Halder wrote in his diary on July 11. ‘The enemy is putting up a fierce and fanatical fight.’ On the following day, Britain and the Soviet Union signed a pact pledging ‘mutual assistance’ against Germany. Neither side would make a separate peace. At the same time, the British bombing raids on Germany, of which Churchill had written to Stalin a week earlier, began with a renewed intensity on July 14 when Hanover was bombed, followed, during the next nine days, by two more raids on Hanover, two on Hamburg, two on Frankfurt and Mannheim, and one on Berlin itself. ‘In the last few weeks alone’, Churchill declared in a broadcast on July 14, ‘we have thrown upon Germany about half the tonnage of bombs thrown by the Germans upon our cities during the whole course of the war. But this is only a beginning…’.

On the day of Churchill’s speech, British Military Intelligence sent a top secret message to the British Military Mission in Moscow, to pass on at once to the Russians details, culled from the German Enigma messages, of the dispositions and order of battle of the German forces. Two days later, at Churchill’s specific request, the Military Mission in Moscow was sent an appreciation of German intentions in both the Smolensk and Gomel areas, together with the news, once again taken from the Germans’ own most secret instructions, that the German Air Force had been ordered to prevent Russian withdrawals by attacks on the railways leading to the rear.

The ability of the Russians to withdraw their troops was distressing to the German High Command, which had hoped to see those troops destroyed in battle. But Hitler’s confidence was undimmed. On July 14, in a supplementary to his earlier Directive No. 32, he set out a plan for eventual reductions in German military, naval and air strength. Hitler began with the words: ‘Our military mastery of the European continent after the overthrow of Russia…’.

That day, at Orsha, a Soviet artillery officer, Captain Flerov, used a new multiple rocket launcher in action for the first time; this was the Katyusha, which could fire 320 rockets in twenty-five seconds. It was to wreak considerable havoc on the German forces in the months to come. But Nazi tyranny was still triumphant; on July 14, Martin Gauger, a German civil servant who had refused to take the oath of allegiance to Hitler in 1933, and had fled to Holland in 1940 by swimming across the Rhine, only a few hours before German troops entered Holland, died in Buchenwald. That same day, in the Galician town of Drohobycz, SS Sergeant Felix Landau, one of the instigators in 1934 of the murder of the Austrian Chancellor, Dr Dolfuss, described in his diary the moments before a massacre of Jews in a nearby wood: ‘We order the prisoners to dig their graves. Only two of them are crying, the others show courage. What can they all be thinking? I believe each still has the hope of not being shot. I don’t feel the slightest stir of pity. That’s how it is, and has got to be.’