1

Birthing Empire

Economies of Childrearing and the Establishment of American Colonialism in Hawai‘i

There was an old woman who lived in a shoe. She had so many children she didn’t know what to do.

English nursery rhyme1

We multiply like the Jews in Egypt. . . . Perhaps we are to inherit the land.

Missionary son Amos Cooke2

Domestic Economics in the Islands

Most among the ABCFM missionaries who stepped aboard New England ships traveling to the Hawaiian Islands between 1819 and 1848 believed they would never see the United States again. As part of the revivalist fervor sweeping the United States during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, young Americans—almost all college and seminary graduates—eagerly gave away their earthly possessions in order to qualify for Christian missionary service. Levi Chamberlain, for example, was a successful Boston businessman who sold his dry goods business and donated all his money and property to the ABCFM after joining the second company of missionaries to Hawai‘i in 1822. Sybil Bingham gave away her small but entire fortune before leaving with her husband for the islands. Other hopeful missionaries worked off their debts before the ABCFM would commission them for service.3

To ensure that missionaries devoted their entire energies to developing a written language for the Hawaiian people and translating the Bible into the Hawaiian language, the ABCFM took command of the missionaries’ economic resources by supplying the missionaries’ domestic needs through a common-stock system administered by appointed agents who were also commissioned as missionaries by the ABCFM. The ABCFM hoped to preserve the missionaries’ spiritual focus, as well as their reputations. “The kingdom to which you belong is not of this world,” ABCFM secretary Rufus Anderson instructed the missionaries. “Your mission is to the native race.” With supplies taking six months to reach the islands, missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands practiced rigid economy partly out of necessity, and partly out of a desire to appear trustworthy to the American churches upon whom they depended for total support.4

Within fifteen months of the fist missionaries’ arrival in 1820, each of the seven American wives gave birth. The arrival of these infants propelled the missionaries to begin the first of many renegotiations with the ABCFM over the common-stock system. For all but one family, parenthood was new. Exhausted missionary mothers demanded private food quotas rather than sharing all meals at the “good old long table.”5 The new mothers no longer wanted to rotate cooking responsibilities, required three times a day for as many as fifty missionaries and Hawaiian guests. A few mothers flatly refused to continue their communal duties, and the remaining couples soon reverted to operating as nuclear families.6

The economy of childrearing was a distracting and familiar topic for the ABCFM board in Boston. By 1822 the seven-year-old Ceylon mission was pressuring the ABCFM to establish a seminary in the United States to which it could send its children, some as young as eight years old. The board stayed silent during eight years of continual agitation from the Ceylon mission until 1830 when, according to the board, “the case of [the missionary] children was concisely and ably stated” by their parents for the first time.7

The Ceylon missionary parents presented to the board an economic argument, arguing their own inability to provide for the futures of their children. The American parents did not believe they could educate, employ, settle, and marry their children in Ceylon. As missionaries who earned no income, and who were not allowed to individually profit in any way from their work, they had no resources to offer their children to return to the United States. Lumping their children together with native children in rudimentary missionary schools, they argued, would be woefully inadequate, as well as morally dangerous. This fear of raising white missionary children in a non-Christian environment, and the corresponding impetus to racially segregate the white children, would be echoed by missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands.8

Within six years of the Hawaiian mission’s founding, the Hawaiian missionaries were also debating the “condition and prospects of [their] children.”9 In personal correspondence American missionaries in the islands were consumed with fear for the future of their children. “Of all the trials incident to missionary life, the responsibility of training up children, and of making provision for their virtue and usefulness . . . is comparatively speaking, the only one worthy of being named,” wrote missionary mother Lucy Thurston.10 “When my thoughts turn to their future prospects in life, a darkness visible seems to brood over their path,” Abigail Smith declared. A “thorough education” for her children, the missionary mother stated, was the “only personal luxury I crave.”11

The Hawaiian missionaries wrote letters to the board: “The education and future prospects of our children constitute a subject of increasing solicitude with us,” the missionaries wrote to Boston.12 “Children over eight or ten years of age . . . ought to be sent or carried to the United States,” missionary Hiram Bingham wrote, “in order that they might escape the dangers of a heathen country . . . and at the same time allow the parents more time and strength for missionary work.” Bingham rationalized that while parents could give very young children the “rudiments of education,” there was “no employment into which the parent could with propriety thoroughly initiate them as a business for life.” Bingham and his fellow missionary parents in Hawai‘i conflated worries regarding future employment opportunities for their children with their views of Hawaiian culture, which they believed had nothing to offer their children but dissipation, paganism, and intellectual malaise.13

The ABCFM missionaries also regarded the lack of New England–style preparatory schools and colleges in the islands as a severe hindrance to their children’s upbringing. Although they attempted to replicate the New England model for Hawaiian elites—such as at the Royal School in Honolulu—the majority of missionaries focused their attention on teaching native Hawaiians a written Hawaiian language, the same language they forbid their own children to learn. Missionary parents wanted their children to learn English, Greek, and Latin, a task, the parents argued, for which they had no time. The Congregationalist requirement that a male missionary be seminary ordained guaranteed that ABCFM missionaries to Hawai‘i were well educated, but missionary parents also desired the same advantages for their children.14 Our children “have a right to an education by inheritance,” the Hawaiian mission appealed in a joint letter to American churches.15 “We could more easily do with only half a loaf of bread than without the means of educating our children,” missionary Ephraim Clark stated.16

Missionary parents were hindered in their parental goals by Hawaiian cultural differences. The nineteenth-century American practice of apprenticing one’s son into his eventual occupation proved difficult for missionary parents in the islands. “There is not a mechanic in all the islands with whom any missionary would suffer his son to live in order to learn a trade—there is not a merchant with whom he would allow him to become a clerk—not a farmer to whom he could entrust him,” missionary Dwight Baldwin emphatically wrote. The “low character of the native population” and the “almost universally irreligious and immoral character of foreigners with whom the islands abound” make us “afraid to settle our children here,” Baldwin concluded.17

Despite the missionaries’ arguments that there were no educational or employment opportunities for their children in the islands, the official position of the ABCFM was that “as a general rule . . . children should be educated under the inspection of their parents.” ABCFM secretary Jeremiah Evarts reminded the missionaries that “impurity and profaneness of language” also existed in U.S. schools. Missionaries who exchanged their own parental guardianship for the perceived benefits of an American education were simply exchanging “one degree of danger with another,” Evarts cautioned. He encouraged the missionaries to have faith that God would bless their parenting efforts in the islands.18

Not least on the ABCFM’s mind was the financial impact of providing for the education of missionary children, an expense bound to increase with the size of missionary families. “Should the Board make it a part of their plan to defray the expense of sending your children [to the United States] for education, this item of expenditure would in time become very great . . . the public mind would not probably bear the expenditures to which such a system would give rise,” Evarts wrote.19 Considering that the eventual number of children born to American missionaries in Hawai‘i numbered over 250 by the 1850s, Evarts’s worries proved prescient.

The ABCFM secretary attempted to blunt these practical considerations by sympathizing with the missionaries. “Parents find trying difficulties everywhere,” Evarts wrote. For those missionaries who persisted in their demands to send missionary children to the United States, Evarts suggested they see the benefit behind the increasing importance of the Hawaiian Islands to American commerce: “opportunities of obtaining a gratuitous passage,” Evarts argued, “would be to those enjoyed by your brethren [in Ceylon], probably, as ten or twenty to one.” Missionary parents in the islands remained unconvinced. Begging a ship captain to grant free passage to the United States for a six-year-old was the easy part. Parents still had to arrange U.S. guardianship and provide tuition for their children.20

Such was the standoff in 1830 when the Ceylon missionaries finally convinced the ABCFM to alter its policy. Rather than establish a seminary for missionary children in the United States, which the board found prohibitively expensive and unnecessary, the ABCFM agreed to provide one-way passages for missionary children to the United States to attend existing American schools. In 1833 the board extended its policy to missionary children in the Hawaiian Islands, and in 1834 it granted annual stipends to missionary children studying in the United States. By 1846 ABCFM missionaries had sent more than one hundred missionary children to the United States. Over thirty Hawaiian-born missionary children made the six-month voyage around Cape Horn, nineteen unaccompanied by an adult. Most of the children sent to the United States to live apart from their parents were between the ages of six and ten.21

3. The whale ship Averick brought the fifth company of ABCFM missionaries to the Hawaiian Islands in 1832. At least thirty missionary children rode similar vessels on the six-month voyage back to the United States for schooling. The children were usually between the ages of six and ten, and over half traveled unaccompanied by an adult. Mission Houses Museum Library.

The Missionaries Rebel

Placing a dollar amount upon the cost of raising one’s child, while a fairly routine occurrence for parents in the United States today, was disastrous to the nineteenth-century “disinterested benevolence” of ABCFM missionaries in Hawai‘i.22 While scholars have noted the impact of the Panic of 1837 upon decreasing American financial contributions to ABCFM missions, the demands of childrearing and the expectation that “God will not suffer children to be losers, by the sacrifices of their parents in his cause” played the more important role in transitioning the missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands toward new thinking regarding the accumulation of wealth.23 Through their role as parents, missionaries developed a settler mindset toward the Hawaiian Islands, a colonial mentality having permanent impact upon the nation’s domestic culture and political sovereignty.

By 1832 the Hawaiian missionaries were discussing a move from the common-stock system to fixed salaries. Realizing the increased expense the ABCFM board would incur from such a measure, the missionaries resolved that each family should estimate not only their current expenses but what their expenses were “likely to be in [the] future.”24 Clearly some missionaries had begun contemplating a kingdom of this world. Nevertheless, the missionaries continued to eschew private property. In 1836 the mission collectively wrote, “No man can point to private property to the value of a single dollar, which any member of the mission has acquired at the [Hawaiian] Islands.”25 Dwight Baldwin noted, “Every member, I think, to a man, has been engrossed in labors for the benefit of the people. And it is certainly true of nearly every one, that he has turned his attention to no provision whatever which his children might need in America.”26

Assailing many parental minds was the difficult process of shipping young children back to the United States to be thrown upon the goodwill of relatives or other guardians whom the board could procure. By the 1830s missionary feeling had decidedly cooled to the idea. For some parents it was due to the lack of relatives to whom they could send their children. Reports of missionary children who had been tossed around families did not ease their minds regarding the capacity of the board to adequately place their children. Others did not trust their own relatives—“Unitarians,” as one missionary called his—to safeguard their children’s moral upbringing.27 Some parents, unwilling to allow their children to travel alone, simply did not want to leave the islands for the yearlong journey required to personally place their children in American homes and schools.28

Parents were also obligated to obtain permission both from fellow mission members and the ABCFM board to leave the islands. This could prove challenging, as Abner Wilcox discovered when trying to take his young son Albert to the United States to receive surgery on a club foot. Their trip was almost stopped by the arrival of a doctor in Honolulu, who the mission depository agent thought might be able to provide cheaper medical services. From Boston, board secretary Rufus Anderson requested reconnaissance from other members of the mission regarding the medical necessity of Albert’s trip.29

More subtle influences shifted missionary parents away from sending their children to the United States, including cultural and economic changes occurring both in North America and the Hawaiian Islands. In the United States the market revolution of the early nineteenth century drove rural residents to the cities for wage employment, and the consequent rise of the urban middle class changed the nature of domestic relationships. No longer business partners, husbands and wives now divided their duties between public and private spheres. Women commanded the domestic front, in part, by developing complex theories of motherhood to justify the amount of time spent at home in their non-wage-earning capacities.30 Theories exalting the nurturing role of motherhood and the need for constant companionship with one’s children in order to oversee their moral upbringing culminated in the 1847 publication of Horace Bushnell’s immensely popular Christian Nurture: “It requires less piety . . . to be a martyr for Christ than it does to . . . maintain a perfect and guileless integrity in the common transactions of life,” Bushnell admonished parents.31

American missionary mothers in the Hawaiian Islands actively pursued subscriptions to American publications and were familiar with the new parenting theories.32 While not all of them embraced the popularized attitudes, they eventually admitted that “with adequate facilities [and] increased paternal faithfulness the children of missionaries may be trained up here.” With contributions to missionaries dipping in the United States by the end of the 1830s, parents worried that “placing their children so far out of their own influence” to be influenced instead by a country “where the missionary spirit is low” might adversely cause their children to “be lost to the mission.”33

A more important reason behind the missionaries’ reversal regarding the proper location for the education of their children was the economic changes occurring in the islands. As the missionaries explained, “The increase of foreigners of a good character . . . leads to the hope that were there no other employment for our children they might at least some of them, find employment as clerks, overseers, or laborers on the plantations.”34 More to the point, one missionary noted, “Natives are rapidly dying off. . . . Foreigners are multiplying—lands are now put as it were into the market to be leased out to the highest bidder for 25 years.”35

With comfort found in the increasing number of white immigrants to the Hawaiian Islands, missionary parents could also look to the 1840 Hawaiian constitution as a model of good governance, surpassing even their own American political system. No law, the constitution specified, was to be contrary to the Bible, meaning the moral landscape upon which missionary children played had dramatically shifted in favor of long-term Protestant influence and success.36 No greater example of this astounding transformation existed than in King Kamehameha III’s voluntary revolution in ancient landholding patterns. In the 1830s all Hawaiian lands were partitioned by the Hawaiian king, and according to the 1840 constitution, no one could “convey away the smallest portion of land” without his consent.37 With the decline of the Hawaiian sandalwood trade by the 1830s, however, the development of agriculture became increasingly important to the continued economic viability of the islands. The rise of the Pacific whaling industry meant as many as three or four hundred ships stopping each year to buy supplies from the islands. King Kamehameha III’s leasing of land to foreigners knowledgeable in agriculture meant potential trade opportunities for the kingdom, as well as avenues for missionary children to earn wages and acquire land.38

Consequently, almost as soon as the ABCFM had granted yearly stipends to missionary children sent to the United States, missionary parents in Hawai‘i adjusted their family budgets to include keeping their children in the islands and educating them in a yet-to-be-created New England style preparatory school. In 1838 the missionaries resolved that the adoption of salaries was necessary to the “missionary cause,” but they made it clear that any accumulation of wealth was for their children, “not . . . for ourselves.”39 In 1840 the missionaries hastened the Boston board to settle the amount of their salaries “as soon as possible” and complained that the board’s proposed $540 per year was “sufficiently low” for sustaining a family.40 At least one missionary also threatened to take his family back to the United States unless the board established a boarding school for missionary children in the islands.41

In the end missionary families took matters into their own hands. Utilizing whatever mission resources they could muster, the parents in 1841 built a school at Punahou (fresh spring), two miles outside Honolulu. Native Oahu governor Boki had gifted the land to Hiram Bingham, who, eschewing property as required by the ABCFM board, transferred the gift to the Hawaiian mission. The missionaries then determined that the use of mission property for the purpose of educating their children would free missionary labors for the native people, a “most economical expenditure.” The missionaries also notified the Boston board that they had convinced Daniel and Emily Dole, ABCFM missionaries who had arrived that year, to change their plans from missionary work among the native Hawaiians to teaching the white missionary children. “The Lord has graciously sent us instructors to take charge of the school just at the time they were needed,” the mission informed Boston.42

Punahou School, and the consequent retainer of scores of missionary children in the islands, might not have been possible without the aid of Kamehameha III. By 1840 the American missionaries were educating fifteen thousand indigenous Hawaiian children in schools across the islands. The mission had also established boarding schools at Hilo and Wailuku and the Royal School, a Honolulu academy for the children of Hawaiian chiefs. That same year the king established the first Hawaiian legislature and took financial responsibility for the support of all native elementary schools, a propitious act that eased the financial strain on the mission as it began to focus on retaining and educating its own children in the islands.43 Emily Dole noted that Kamehameha’s investment came as “a great relief to the mission, especially at this juncture of establishing a boarding school for the children of the Mission.”44

Faced with the realization that continued foreign encroachment was inevitable, the first Hawaiian legislature made primary education compulsory in 1840. So important did the Hawaiian government consider missionary schools to the ability of the indigenous population to maintain its national independence that the legislature soon enacted a law requiring a man to demonstrate his ability to read and write before being allowed to marry. Hawaiian royalty additionally looked to the missionaries to teach their own children the English language, in order to prepare the monarchs to operate within a region increasingly crowded by American and European diplomats and naval vessels.45

Two years after Kamehameha created the first public education system, the ABCFM transitioned to a salary system. The board allotted each couple $450 per year and granted children under ten $30 and children over ten $70 annually. The board abolished the common-stock system but retained the depository at which missionaries could purchase goods. Missionary parents could now give their children a New England education in the islands and save their personal incomes for their children’s futures.46

Still, missionaries worried about their children. Although Punahou School did not charge tuition to the missionary families, parents hoped the board would provide financial aid for the school’s operational costs. Some argued that the allowance for children under ten precluded parents’ abilities to pay for their children’s board at the school, around $25 per year. “You doubtless anticipate that money is again to be the subject of discussion. And you are right,” one missionary wrote the board in 1842.47 “Is it a small matter for a feeble mother to lie on her couch and see her children growing up and running wild without education?” asked another. Missionary parents retained the ever-present fear that without formal schooling their children would fall into ruin.48

More seriously, missionaries had begun to leave the mission because of their children. “My father has left the Board so we haf to work for our living,” explained ten-year old Sarah Andrews (1832–99).49 Sarah’s father justified his 1842 departure from the ABCFM as necessary for the support of his family. “It is my duty to look forward a little and see how I can accomplish my own designs to do the missionary work,” Lorrin Andrews stated. “What I call my own designs is the education of my children.” Andrews had made the momentous conclusion that the earthly success of his children would signal the spiritual acquiescence of the Hawaiian Islands to Protestant Christianity. Some missionaries wanted Andrews to leave the islands, but Andrews refused. Instead he taught school to Sarah and her four siblings before joining the Hawaiian government as a member of the Privy Council and, later, as a Supreme Court justice. Andrews was among the first American missionaries to reverse their economic challenges by offering their political services to the Hawaiian monarchy. Others, such as Reuben and Mary Tinker, resigned from the ABCFM and returned with their five children to the United States.50 After Elizabeth Judd’s parents severed their relationship with the board in 1842, Judd (1831−1918) wrote “a new and happier life opened to us all.” In 1843 the Hawaiian government appointed her father, Dr. Gerrit Judd, secretary of state for foreign affairs.51

In Boston, the ABCFM held its ground. Salaries were one thing, but the accumulation of private property and the acceptance of government appointments were quite another. Sereno Bishop (1827–1909) thought his parents’ salary “comparative opulence” to the family’s previous way of living, but Sereno’s father was incensed the board still required the family to send all supplemental income to the mission depository. Sereno’s stepmother annually earned between $400 and $500 making and selling butter, all of which she dutifully sent to Honolulu.52 “The only course that is safe for the minister and missionary . . . is, in holding on in his spiritual course,” board secretary Rufus Anderson reminded the mission in 1846. “We all most earnestly deprecate having any other one from the mission coming into any sort of official connection with the government,” Anderson added in reference to former missionaries like Andrews and Judd.53

Missionary parents continued to agitate. “The existing regulations of the mission in regard to herds . . . are offensive to some of our members, and are regarded by them as absurd,” mission depository agent Levi Chamberlain wrote the board in 1847. At least one missionary thought it was time for the missionaries to “have the right of making and using property as clergymen do at home,” Chamberlain noted. “Thus they may be able in due time to make provision for their families.”54 With Punahou School’s opening as a preparatory school, parents now argued that it was “inadequate.” Parents also wanted a college. As one English-language Hawaiian newspaper declared, “Every civilized, educated and Christian nation must have an elevated institution of learning, well officered and well endowed.”55 With greater opportunities for keeping their children in the islands, parents now worried about “capital” for funding advanced education for their children. Less than eight years before, the Hawaiian mission adamantly had declared that it was “very undesirable that any brother should turn aside from his work to engage in labor or [trade].” Missionary parents now argued for permission to privately invest in the indigenous economy, create institutions solely for the benefit of their white children, and establish white settlements outside ABCFM control, certainly impressive goals for a minority American population living outside formal U.S. power.56

Missionary parents knew they held the upper hand and, according to the board, were growing “impossible to guide.” At the 1848 general meeting in Honolulu, the mission counted 130 mission children, not including the ones who had been sent to the United States. Missionaries demanded the board grant them permission to acquire private property for their children. Chamberlain summarized parental feeling at the meeting: “They recommend that every obstacle [to acquiring private property] be removed . . . that we may have it in our power to obtain means to provide for our children either by settling them in the islands or doing something to educate them in the United States. . . . [I]s it not the duty of parents to provide for their children? Our sons must have employment, and, if they remain in the islands, they must have land, horses and cattle, and who shall provide all these things for them?”57

Chamberlain further advised: “Colonization by means of missionaries might well receive the attention of the wise men who have connected themselves with the missionary enterprise.” Although couched in household concerns, Chamberlain and his fellow missionaries were advocating total colonization, the impact of which would be nothing less than the transformation of the islands in accordance with their Protestant religion, liberal political values, and private property laws: a bequest to their numerous offspring.58

The ABCFM Reacts

In 1848 missionary parents prevailed. In fact, the ABCFM board had received enough personal correspondence from individual missionaries in Hawai‘i for Rufus Anderson to estimate that as many as twenty-six of the forty missionary families in the islands would return to the United States for the sake of their children. Anderson estimated the cost of returning these families to the United States would be $26,000, “not to speak of the missionary labor and influence at the islands.” To lose over half of its missionary presence in the islands, after spending “about seven hundred thousand dollars on the Sandwich Islands people since the year 1819,” was untenable to Anderson and the board. Thus, he wrote, “nothing short of the certainty of far greater evils would have induced the Committee to such a risk” as the one the board took that year.59

“I know not whether the communication I am about to make will take you by surprise,” Anderson wrote the Hawaiian mission on July 19, 1848. Such was the beginning of a momentous announcement from Boston. No longer would the ABCFM stand in the way of its missionaries pursuing the ownership of private property in Hawai‘i. Additionally the board would transfer all mission lands and property to individual missionary families. In order to encourage the colonization of American missionary families in the islands, the ABCFM would concede control over Protestant Hawaiian churches and allow American missionaries to obtain their own financial support from their native Hawaiian congregations.60

“O Brethren,” Anderson wrote, “you have only come to a new epoch in your labors at the islands. You will need to gird yourselves up anew, that you may become the fathers and founders of the Christian community that is to exist in that North Pacific.” The goal, Anderson explained, “is to keep the greater part of your children with you at the Islands, and to give them such an education and setting up, as you can there—as our fathers did in the first settlements of this country.” After decades of arguing, Anderson now agreed that white colonization in the Pacific could accomplish the long-term goals of the ABCFM: namely, to establish a Protestant Christian outpost in the Pacific region.61

At this critical juncture the Hawaiian government again assisted the missionaries. Kamehameha III had already established his preference for foreign advisers, and the newly established Hawaiian legislature had agreed with him that it was necessary to “select persons skilful like those from other lands to transact business with foreigners.” Beginning in 1845 these advisers, including former missionary Gerrit Judd, presided over what became known as the Great Māhele, one of the most astounding volitional acts of a national sovereign in history. The king divided all Hawaiian land among the crown, chiefs, and common people, and again divided crown lands between him and the Hawaiian government. Private individuals, “whether native or foreigners,” could for the first time seek permanent title to their land grants and claims. Individuals could sell their titles, and by 1850 even alien residents could buy and sell property to anyone.62

Native Hawaiian John Papa Ii, who served Kamehameha III and later sat in the House of Representatives and on the Hawaiian Supreme Court, described the Hawaiian response to Kamehameha’s act: “It was said that he was the greatest of the kings, a royal parent who loved his Hawaiian people more than any other chief before him.”63 Later Hawaiians would remember Kamehameha III differently. “The real loss of Hawaiian sovereignty began with the 1848 Māhele,” Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa writes.64

The ABCFM missionaries in Hawai‘i were forthright in their efforts to take advantage of the Māhele. The ABCFM mission pursued land titles for its homes and churches, property that at one time had been granted to the mission by the king and chiefs. The ABCFM then sold the titles to individual missionaries. Transactions between the ABCFM and individual missionaries often were written for “$1.00 and services rendered.” For example, former missionary Richard Armstrong bought 1,382 acres of land from the government in Ha‘ikū, Maui, for $2.00 and services rendered.65 As nineteenth-century native historian Samuel Kamakau noted, “The missionaries were given land by the chiefs without any payment. They left these to the American Board when they moved away from the land, and those missionaries who wished to own the lands given by the chiefs bought them of the American Board. . . . They were clever people!”66

Missionaries also acquired property from the Hawaiian government through gifts, gifts for service, and outright purchase. All sales of government lands were crucial to the government’s revenue stream, yet astoundingly the Hawaiian government justified transactions with missionaries as being necessary for the care of missionary children. In a joint statement the Foreign and Interior Ministries argued in 1850: “Much has been said against sales of land to individuals of the American missionaries at low prices. But nothing can be more unreasonable and unjust. It is well known that these parties are severing their connection with the Board in Boston with a determination to seek support for themselves and families on the Islands, that they return poor and in most cases with numerous children all born in the Islands.”67

The ABCFM plan appeared to work. By 1850 the missionaries owned close to eight thousand acres of former government lands. The mission reported to Boston that “all” at the 1849 general meeting agreed that the board’s changes allowing private property and income “would be likely to diminish the number of [missionary] returns” to the United States. Although some missionaries worried about the ability of their native congregations to support them, the board assured missionaries who left the formal care of the ABCFM that they could still receive grants-in-aid and provision in old age as needed. Their children would still attend Punahou School free from tuition.68

The Hawaiian Evangelical Association Is Born

Within the first few years of the ABCFM announcement, at least six families took advantage of the plan and left the support of the mission, yet new conflicts soon arose. Rumors reached Boston that these former missionaries were engaged in government surveying and were serving in the Hawaiian national legislature. The “Resolution relaxes no man’s responsibilities and leaves him no more at liberty than he was before to become a legislator, mechanic, surveyor, landbroker or speculator, trader, banker, or money broker,” Anderson wrote missionaries in 1851; “grasping after worldly gain, is no part of the object of this act.” Although missionaries released from the ABCFM were to raise their own financial support, the ABCFM limited the ways in which they were allowed to do so.69

Income raised from secular occupations jeopardized one’s relationship with the ABCFM. In a private letter to his son, Richard Armstrong predicted, “The native churches will never support the missionaries; they can help, but the burden must rest somewhere else. The missionaries will of necessity in this way be more or less engaged in secular pursuits.” Armstrong had already left the mission to serve the king as minister of public instruction, a position looked upon very skeptically by the ABCFM. Meanwhile the California gold rush, a boon to Hawaiian farmers and merchants supplying San Francisco, caused prices of goods in the islands to rise. Missionary families sent another flurry of letters to Boston arguing against the board’s expansive definition of ill-gotten gain.70

Clearly the ABCFM hoped the missionaries would earn full financial support as pastors in the islands, while training their own children and a native pastorate to carry on after their retirement. The board also hoped to end its financial support of the missionaries without sacrificing any of the missionary spirit. The board had no desire “to change this mission into a mere secular community, into a colony,” Rufus Anderson complained. “It was a far different proposal that was commended to your attention.” Financing changes were “forced upon us,” Anderson reminded the missionaries, because “the parental feelings of not a few of you seemed likely to overpower your missionary self-consecration, and bring you home.”71

The Boston board now realized that missionary practice had intractably shifted to include secular pursuits, demonstrating an agenda that in later decades the U.S. government would formally undertake in the development of its colonial possessions. Missionary families easily justified their land purchases. As Kame‘eleihiwa notes, “It was not surprising that these influential foreigners used the new system to their advantage. . . . They firmly believed that by acquiring and developing Hawaiian ‘Āina they were teaching the ignorant Natives how to improve the economy and become a ‘civilized’ capitalist nation.”72

Not all the missionaries were ready to end the communal property and salary system. Abigail Smith wrote that the family’s purchase of land in 1854 “was the first direct effort we had made to increase our possessions, and we should not have done this, had it not seemed very necessary in the new arrangements for our support.” Smith rationalized her acquiescence to the new ABCFM policies regarding private property: “Land here costs a great deal—but it will never probably cost less than now and perhaps our Heavenly Father designs this to be a comfort to us and our dear children in future years.”73

The majority of missionaries, however, had shifted away from such sentimentality toward communal life. In 1854 the ABCFM transferred formal governing power over Congregational activities in the islands to the newly created Hawaiian Evangelical Association (HEA). With this action the ABCFM gave the missionaries “home rule” status, and the board considered its missionary work in the Hawaiian Islands essentially finished. Still the economic concerns of the missionaries stalled efforts to train a native pastorate. Some missionaries argued that they could find few viable candidates, but other missionaries blamed fellow missionaries. “But why have the missionaries been so tardy in bringing forward a native ministry?” one missionary wrote the board. “A pastor can get a larger salary from a larger flock than from a small one. . . . To carve up their mammoth churches and form distant parishes with distant pastors would so reduce the number who contribute to their support that the amount would not meet the wants of their families.”74

The U.S. Civil War in 1861 devastated American contributions to ABCFM missions just as it devastated American churches. The Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist denominations each split, in part, over the issue of slavery, and the ABCFM, made up of Presbyterians and Congregationalists, was not exempt from the controversy. The board lost donations from Southerners, who were convinced the ABCFM was a Boston abolitionist group. It also lost the support of Northerners for accepting donations from slave owners. To hasten the end of ABCFM financial support to missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands, Rufus Anderson traveled to the kingdom in 1863 to conduct meetings with the HEA. The HEA finally agreed to divide most large churches, giving new churches to native pastors, and allowed native pastors and laymen to join all religious governing bodies in the islands. From this point forward the ABCFM considered itself an “auxiliary” to the HEA. While some missionaries retained partial support from the ABCFM until their deaths, others were told to depend upon their children, now landowners, merchants, lawyers, surveyors, government workers, pastors, and teachers in the islands.75

4. Missionaries Amos and Juliette Cooke and their seven children, ca. 1860. Missionary families, on average, were quite large. Amos Cooke left the ABCFM to begin the successful mercantile business Castle & Cooke with partner and former missionary Samuel Castle. Many of their children remained in the islands, and the two partners would later finance the business ventures of several missionary children. Mission Houses Museum Library.

Missionary Descendants Come of Age

The American missionaries to Hawai‘i arrived with idealistic notions of preaching a message of spiritual conversion to the Hawaiian people without entangling themselves in political and economic concerns. With the birth of the first missionary child in 1820, missionary practice changed. Not only were white missionary children aware of these changes, but they actively participated in completing their parents’ revolution. The children’s understanding of these events, however, almost totally differed from that of their parents. Missionary children felt both a tremendous pride in and responsibility toward their parents’ work. “Should they not be considered among the greatest men on earth?” young Levi T. Chamberlain II (1837–1917) asked in a school essay.76 “Perhaps there is no other missionary station whose success has equaled that of the mission,” a student writer in the Punahou Gazette argued to peers, at the same time missionary parents debated returning to the United States in the 1840s. “Can ye who have spent the best portion of your lives and strength in laboring for these inhabitants give them up now in their present critical circumstances?” the writer admonished missionary parents.77

Missionary children knew their parents felt great trepidation regarding the future, yet the children seemed to possess a better grasp on the domestic economy than either the missionaries or Boston board. Seventeen-year-old James Chamberlain (1835–1911), who worked in the mission depository, ridiculed the board for shipping fully assembled rocking chairs, “while if they had been packed in boxes ten times the amount of freight would have been saved.” Chamberlain also noticed when friends Curtis Lyons and Henry Lyman earned “more than $100 per month” as government surveyors, compared to his $100 per year at the missionary depository. “Curtis sent down $1000 the other day to be put at interest for him,” Chamberlain wrote his sisters Martha and Maria.78

In a particularly resourceful move, Henry Lyman (1835–1904) asked the Hawaiian minister of the interior to appoint his father as land agent for the southern half of Hawai‘i. Lyman was too young to hold the position himself but asked his father to use his new position to make the younger Lyman a government surveyor. “This arrangement was perfectly satisfactory to me,” Henry wrote, “to the no small discontent of my father, who was not at all pleased with the idea of becoming, even nominally, a government official.” Lyman’s tale reminds us that parental guilt is a powerful weapon in the hands of a child. “On second thought,” Henry noted, “[my father] concluded for my sake to accept the situation, though it involved a compulsory sacrifice of inclination on his part.”79

Missionary children understood the financial hardships their parents experienced. At the depository Chamberlain observed that there was “hardly a missionary that is not in debt,” with “some of them having taken twice their salary in goods and other things.” Even though former missionaries Samuel Castle and Amos Cooke charged the missionaries lower prices than native Hawaiians and other foreigners who shopped at the former ABCFM depository, the burgeoning market for Hawaiian goods placed even the Chamberlain family in debt to the store.80 Missionary children worried about their “duty and privilege” to help aging parents. “I feel that you have a claim upon me. I am your oldest son,” Warren Chamberlain (1829–1914) told his father. “Perhaps the King might favor me in some way.” Chamberlain was not the only missionary son who hoped for government patronage in establishing a financial future in the islands.81

The U.S. Civil War also boosted the Hawaiian economy at a time when many missionary children were entering adulthood. With the Union embargo on Confederate sugar, northern states increased their importation of Hawaiian sugar. In 1860 the Hawaiian Islands contained twelve plantations exporting one and a half million pounds of sugar annually. By 1866 the kingdom possessed thirty-two plantations who together exported nearly eighteen million pounds that year. Missionary children benefited. Former missionaries and successful Honolulu mercantilists Castle and Cooke financed missionary sons Samuel Alexander and Henry Baldwin in the sugar industry. Baldwin’s brother Dwight joined former missionary Elias Bond at the Kohala Sugar Plantation. Alexander’s brother James began a plantation with their father. Joseph Emerson became plantation manager at Kaneohe, Oahu. Emerson’s brother Oliver worked as a plantation overseer before entering college.82

Encouraging his parents to begin planting sugar on their land, missionary son Albert Wilcox (1844–1919) became one of the most successful planters in the islands. “Albert has quite a mind to go to cane planting,” his mother, Lucy Wilcox, wrote in 1862. Wilcox’s brother Edward (1841–1934) also spent time working on a sugar plantation. “We usually worked till midnight four days in the week. I got $1 a day and board, and $1.00 extra for the night work, making $10.00 a week,” Edward Wilcox remembered. “This seemed like affluence beyond the dreams of avarice.”83 Their brother George Wilcox attended Yale University in order to study engineering and returned to the islands to build water irrigation systems for sugar plantations.84 Rufus Anderson proved prophetic in his encouragement to missionary parents in 1849: “As for your children, the great field of enterprise now is certainly in the part of the world where you are.”85

Missionary daughters also entered the changing Hawaiian economy, particularly as teachers. As Maria Whitney (1820–1900) explained in 1878, “While we were connected with the Seminary at Lahainaluna, we received a larger salary from Government than we needed for our support. [We] invested $1,000.00 in the stock of the Sugar Plantation at Kohala, Hawaii, which after more than 12 years of patient waiting, is now paying dividends.”86 In 1870 Anderson noted over thirty missionary daughters employed in the islands.87

Missionary daughters also owned land. Although Jean Hobbs concluded in her study of missionary land deeds that “comparatively small areas were left by will to descendants,” many children inherited or bought land nonetheless. Jonathan Osorio writes that all but two of the missionaries who remained in Hawai‘i after the Māhele possessed land. Helen, Elizabeth, and Laura Judd each received lots in Honolulu after their father’s death.88 “Honolulu is becoming a large place. Houses are all the time going up,” James Chamberlain wrote his sisters. “There has probably been two hundred or more wood houses put up since you left.” At least one peer, Chamberlain noted, had bought one.89 Sanford Dole (1844–1926) observed that missionary lands “became in later years of great value and enriched their owners.”90

As Hawaiian-born subjects, missionary children also took political appointments from the Hawaiian government. Joseph Emerson accepted a position with the Hawaiian Government Survey, and Nathaniel Emerson became president of the Hawaiian Board of Health. William Richards Castle and William Neville Armstrong served as attorney generals and Samuel Mills Damon as minister of finance. Albert Judd and Sanford Dole accepted appointments to the Hawaiian Supreme Court. At least fifteen missionary sons were elected to the national legislature. In 1887 nine of the forty-nine members of the legislature were missionary sons.91

At a time when native Hawaiians were watching foreign diseases destroy the indigenous population, it certainly appeared as if the white missionary children had, in the words of Amos Cooke (1851–1931), “multipl[ied] like the Jews in Egypt” and “inherit[ed] the land.”92 English travel writer Isabella Bird noticed the growing discrepancy during her visit to the Hawaiian Islands in 1873. “At Honolulu and Hilo a large proportion of the residents of the upper class are missionaries’ children,” Bird wrote. “Most of the respectable foreigners on Kauai are either belonging to, or intimately connected with, the Mission families; and they are profusely scattered through Maui and Hawaii in various capacities.”93

Missionary children ferociously protected their familial legacy—“our inheritance,” Sanford Dole called it.94 With the ascension to the throne of Lot Kamehameha in 1863, the children correctly sensed that native emotions had shifted against American missionary influence. Lot immediately distanced himself from the former American missionaries by refusing to support the constitution they had helped to write and by reinstituting native priests, such as medical kāhuna. The missionary children rose to his challenge. “We are the children of the missionary enterprise,” Anderson Forbes (1833–88) declared.95 “It is to us that the Hawaiian nation must look for . . . its advocates, its protectors and defenders,” Asa Thurston (1827–59) argued.96

Missionary children—now adults—were concerned that the institutions their mothers and fathers had created in partnership with earlier Hawaiian sovereigns were in jeopardy. In 1865, for the first time, no one associated with the ABCFM or HEA served on the Hawaiian Board of Education. The new inspector general of schools, Abraham Fornander, was openly critical of the missionaries.97 Soon adult missionary children were also calling the Hawaiian legislature “one of the weakest and most corrupt that ever sat in Honolulu.”98

By the reigns of King Kalākaua in 1874 and Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1891, fortune tellers and mediums, not missionaries, played frequent advisory roles to the Hawaiian monarchy.99 By the 1880s the term missionary had become an epithet. In the words of one missionary son, anyone who “would not bow the knee” to such changes “received the honorable sobriquet of ‘missionaries.’”100 Even more distressing to missionary descendants was King Kalākaua’s 1886 revival of the ancient Hawaiian religion. “This was done in order to promote sorcery and bring the nation into political subjection to the king himself as the chief sorcerer,” Sereno Bishop protested.101

Just as important as defending their parents’ religious legacy in the islands were the missionary children’s attempts to protect the material inheritance bequeathed by them. Bribery scandals erupting under Kalākaua, and Lili‘uokalani’s final attempt to dilute the political weight of white landowners went too far in threatening the missionary descendants’ interests in the islands.102 “In order to safeguard the stability of the Government and its commercial interests,” Oliver Emerson (1845–1938) concluded, “a closer relation with the United States was more and more favored.”103 Bishop was blunter: “On account of the commercial necessities of the Islands, nothing can be more certain than that some strong and efficient government must and will be maintained here.”104

Missionary descendants in Hawai‘i might not have been as eager to accept the formal power of the United States had it not been for their belief that Americans had abandoned their parents and left the Hawaiian missionary project incomplete. Missionary children’s growing calls for U.S. annexation stemmed, in part, from their tenuous relationship with the ABCFM. “The old missionaries were not reinforced by outside aid, and on the shoulders of a native ministry was laid a burden which we can now see was too heavy for it to bear,” Samuel Damon (1845–1924) assessed in 1886. “I think there are few who are truly conversant with the real state of affairs on our Islands but will acknowledge the inexpediency of this action.”105

Missionary children interpreted the ABCFM’s move to end its financial support of missionaries in Hawai‘i very differently from their parents. To their parents, the ability to own private property and pursue individual income allowed better provision for their children. To the children, this difficult transition represented an American desertion of their parents and the islands, the effects of which they were left alone to rectify. “These men and women love the fair land of their birth and are not willing to let it return to barbarism,” Emerson said of fellow missionary sons and daughters. “Their pride in the institutions which their fathers were enabled to build, spur them on to a studied and careful support of humane and worthy causes which may save their loved native land.”106 American aid, in the form of U.S. trade reciprocity, military protection, and, ultimately, annexation signaled for missionary descendants the rectification of decades of familial pressures.

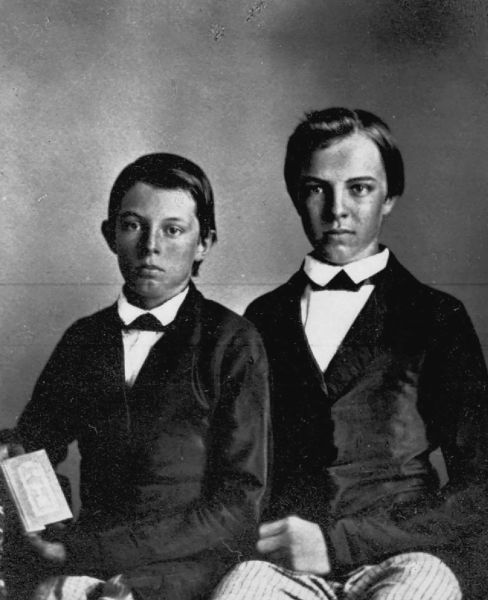

5. Sanford B. Dole (1844–1926) and George H. Dole (1842–1912). The Dole brothers were born in the Hawaiian Islands to missionary parents Daniel and Emily Dole. Sanford Dole became the first president of the Hawaiian Republic after leading the revolution against the Hawaiian monarchy. Mission Houses Museum Library.

Missionary children couched their pro-annexation arguments in terms of rescuing the islands from their moral decline and argued that the American churches had not fully done their part. While the ABCFM officially “favored the independence of the Islands,” missionary children were not as deferential to the ABCFM position as their parents had been. White missionary children living in the islands were, in the words of one missionary son, “practically unanimous for the overthrow of the monarchy and for annexation to the United States.”107

Familial Colonialism and Hawaiian Sovereignty

What missionary parents and their children held in common was an inability to see their struggle as an economic one. “To us they left no heritage of gold, or jewels or land,” Albert Lyons (1841–1926) addressed fellow missionary descendants in 1890. “A richer bequest they left us; we inherit the fruits of their work in the material prosperity which the Christian civilization they established here has made possible.” Missionary descendants conflated their religious ideals and economic agendas, as had their parents, who argued for more wealth even while denying they sought it. “And how can I better aid the work of the Master than by earning money thus to devote to missionary enterprises which must be maintained by the contributions of Christians?” Lyons asked. After nearly a century of American missionary activity in the Pacific, the question seemed perfectly natural.108

While such a distant American frontier implied physical hardship and danger, the health and survival of American missionary children in Hawai‘i were never in question. The average family size of missionary families living in the islands was between 6 and 7 children. Of the 282 mission children born by 1853, only 36 had died in the islands. In fact, Rufus Anderson postulated that the sizeable number of missionary children was due to “the extraordinary healthfulness of the Islands.”109 By contrast, British children born in nineteenth-century India had twice the mortality rate as their peers back home, often succumbing to tropical diseases during their first five years of life. British colonial administrators worried that a permanent white population in India could not survive past the third generation.110

American missionary parents instead fixated on the moral education and economic independence of their children.111 Missionary parents pursued both goals with inordinate fearfulness. “It has always seemed to me,” Anderson complained, “that the great enemy of missions directs his chief assaults on the parental side of our missionary brethren, as their most assailable point.”112 Missionary children in Hawai‘i derived security not only from their parents but also from the ways in which their parents addressed the children’s needs and the environments in which missionary parents told the children they were secure. Missionary children learned to accept Hawaiian lands and political appointments as necessary to securing their own “civilized” place in Hawaiian society. In the case of their economic well-being, missionary children in Hawai‘i pursued U.S. annexation as a form of parental protection over the institutions and property their parents had fought long and hard to secure.

The complicated familial relationships of American missionaries and their Hawaiian-born children contextualize the process by which the United States acquired the Hawaiian Islands in 1898. The political and cultural successes of the ABCFM missionaries in the first two decades of their arrival to the islands became monuments to American Protestant influence in the Pacific, which missionary children later sought to protect. The economic gains made by missionary families, the children believed, were made possible by native Hawaiian acceptance of their parents’ instruction. The revolution ending the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893 demonstrates the complicated mixture of political, economic, and cultural considerations, not least of which religion played a role. White missionary children born in the islands viewed their parents as martyrs worthy of continued recognition both in Hawai‘i and the United States. In many cases the children conflated their parents’ concerns about economic security with their own desires for material success. This sense of entitlement, the missionary descendants argued, was never about them. It was about protecting the legacy of their parents. Missionary children had accepted the normalcy of their parents’ spiritual influence among the early Hawaiian monarchs and continued to live in their parents’ shadows. In the process missionary children expected land ownership, government offices, and economic opportunity in the islands as their birthright.

American missionaries did not begin their residencies in the islands with an economic agenda, but in their role as parents, with the pressures of parenting clouding their missionary zeal, they taught their children to become colonizers. To their children the missionaries bequeathed the rationale and means to participate in one of the most dramatic periods of U.S. global expansion. The missionary experience in the Hawaiian Islands displays international affairs at the most intimate level. That the first president of the Hawaiian Republic was missionary son Sanford Dole reveals the codependence of religious and economic ideals by which nineteenth-century American missionary families in the Hawaiian Islands determined their support for and participation in the birth of an American empire in the Pacific.