3

Schooling Power

Teaching Anglo–Civic Duty in the Hawaiian Islands, 1841–53

There’s a neat little clock—in the schoolroom it stands, and it points to the time with its two little hands. And may we, like the clock, keep a face clean and bright, with hands ever ready to do what is right.

English nursery rhyme1

In the great mansion for men upon earth, we occupy a nursery room, where children may luxuriate and grow into strength.

Missionary son Robert Andrews (Hawaiian Islands, 1865)2

Designed to allow American missionary parents in the Hawaiian Islands to avoid sending their children on the six-month voyage around Cape Horn to New England preparatory schools, Punahou School, established outside Honolulu in 1841, accomplished much more than the missionaries could possibly imagine. While Punahou School may have begun as an isolated boarding school for the white children of American Protestant missionaries, Punahou bequeathed a complicated legacy of Anglo-Protestant influence both in the islands and abroad. By combining religious, moral, industrial, and classical training, teachers at Punahou sought to prepare their graduates for leadership positions within the Hawaiian kingdom. Punahou parents also hoped to transfer the American heritage they had left behind to their children, as preparation for the children’s inevitable journey to the United States to attend Congregational and Presbyterian colleges and seminaries.

As parents and teachers desired, Punahou was at its heart a religious institution, yet its initial practice of racial segregation complicated the white children’s practical application of Christianity in the islands and created tensions between the Anglo-American and indigenous Hawaiian communities. The closed society within which early Punahou students learned also created an environment that allowed the children, through extensive peer networks, to appropriate their schooling for the unique nineteenth-century historical context in which they lived and against which they ultimately rebelled. In 1893 Punahou graduates demonstrated the full impact of their missionary education, devising a political agenda based upon their moral and religious upbringing, a program that included the revolutionary overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy.

Birthing a School

The first American missionaries to arrive in the Hawaiian Islands in 1820 encountered a kingdom very different from the Protestant New England townships they left behind. Yet the missionaries quickly realized that long-held Hawaiian customs were not easy to overthrow, and protecting their children from a “heathen” culture while providing them with an education became missionary parents’ paramount concern. Not only did parents wish to segregate their children from the Hawaiian language, which if understood by their children might introduce them to idolatry and promiscuity, but parents also wished their children, especially their sons, to be prepared to follow in their own footsteps. The ABCFM expected its missionaries to have college and seminary training, including the ability to translate the Bible from its original Hebrew and Greek languages, and most ABCFM missionaries held advanced degrees from New England universities, including Harvard, Yale, and Princeton.3

In the mission’s first twenty years, these parental considerations, coupled with the missionaries’ unwillingness to be distracted from their own labors among the Hawaiian people, led to heartbreaking familial separations. Missionary parents routinely shipped children as young as five years old back to the United States to live among relatives and donors and receive an American education. Many of these children traveled the six-month voyage alone. Some never saw their parents again. With dubious reports of student success reaching them from the United States, missionary parents, by the 1840s, abandoned this practice. In 1841 the parents instead developed a piece of land Oahu governor Boki had gifted them into a boarding school. The school, named Punahou (fresh spring), sat two miles outside the expanding boundaries of Honolulu. Missionary parents convinced new American missionary arrivals Daniel and Emily Dole to serve as principal and teachers to its first class of thirty-four students, including nineteen boarders.4

Punahou-hoe-hoe

From the outset missionary parents demanded Punahou teachers provide their children with superior religious and moral instruction while preparing them to enter elite colleges in the United States. In the early years Punahou teachers attacked these lofty goals through embracing industrial education. In 1844 missionaries William and Mary Rice arrived at the school to help Daniel Dole. As Mary Rice later explained, Punahou was a school that “was intended to be one for manual labor.”5 Over the next ten years, William Rice instructed Punahou boarders in raising kalo, sweet potatoes, corn, beans, bananas, and melons. As one missionary parent wrote in 1842, “We trust [our children’s] physical, as well as mental powers, may be properly developed.”6

This educative pedagogy was based upon a simple reality: Punahou needed to control its costs through requiring student boarders to maintain the school. Punahou boarders provided for their own meals by planting, working, and harvesting the school’s fields. The results were mixed. “Nothing in their temporal concerns gives me so much uneasiness as the scantiness of their food at Punahou,” Abner Wilcox wrote his wife in 1850 about their sons at Punahou. Parents noticed their children had lost weight and often complained of hunger. Yet few parents wanted to jeopardize the school’s existence: “Probably you had better say nothing about all this,” Wilcox concluded.7

For missionary parents, making a New England education affordable in the islands required manual labor and served as an example of agrarian discipline to the indigenous Hawaiian population to whom missionaries hoped to impart agricultural training. For missionary children, the results could be damaging. Student John Gulick, who attended Punahou during the 1840s and 1850s, experienced a physical breakdown due, he later believed, to “the unduly Spartan attitude which his surroundings inculcated.” Required to ring the rising bell for fieldwork without an alarm clock, Gulick “went through unnumbered hours of wakefulness for fear that he might accidentally oversleep.” In 1846 Gulick withdrew from school due to his poor health, attending only intermittently during the next eight years.8

Students called their school “Punahou-hoe-hoe.”9 Rising before daylight, students hoed weeds in the fields until seven in the morning and again for an hour or two after supper until they could see at least two stars. After gathering their own water and changing clothes, students would study until bedtime at nine.10 Punahou students attempted to adapt to the rationale of their elders and the rigors of their schedule. “If you wish to be happy, keep busy,” declared the student-authored Punahou Gazette in 1848.11 “One way to promote happiness is to be industrious,” a female student explained in the Weekly Star.12

What parents and teachers deemed the virtues of an industrious life was evident in Punahou student compositions. The Punahou Gazette, running from 1848 to 1852, was a weekly newspaper students published and read publicly every Thursday afternoon. Students also issued the Critic, a weekly publication criticizing the Gazette. In 1852 the Weekly Star replaced both newspapers by combining contributions and criticism in one issue. The preserved newspapers, meticulously copied by hand for consumption among the student body, provide insight into the minds of the young missionary children, as well as the nature of their education. The extent to which missionary habits were transferred to their children, in the midst of an indigenous culture often at odds with these values, demonstrates the success of Punahou as a colonial institution.13 By keeping busy “the mind is occupied, and we cannot spare time for unpleasant feeling,” the Weekly Star reporter concluded.14 Not all observers agreed with such pedagogy. “We are happy all day long,” noted an old native woman, “not like white people, happy one moment, gloomy another.”15

Dichotomies of Island Learning

In fact moral and religious instruction at Punahou revolved almost exclusively around separating American values from indigenous Hawaiian practice. Time or, more specifically, not wasting one’s time, was a constant theme at Punahou during the 1840s and 1850s. While manual labor was necessary for the functioning of the school, parents and teachers stressed to their children that developing industrious minds was the most important responsibility in which missionary children were to engage their time. As one young scholar explained, “‘Knowledge is power,’—and the more you have of it, the better.”16

Yet all around them Punahou children witnessed an indigenous culture tuned to the natural rhythm of the islands and unmoved by the demands of the clock. Punahou teachers attempted to address this dichotomy by contrasting Hawaiian and American cultural practices and erasing any conflict missionary children may have felt about their station in the islands. In reality, Punahou turned out an odd mix of stern instruction in an unorthodox environment.

The school building itself was constructed in island fashion, a one-story, E-shaped adobe structure about two hundred feet in length. Each wing opened into a courtyard surrounded by verandahs. The building was, according to one observer, “purely a native product.”17 The treeless plain between Honolulu and the school allowed an unobstructed view of the ocean. Mountains were the children’s backyard. Horseback riding, caving, hiking, and swimming competed for the students’ attentions, and weekends were filled with such pursuits. “Children who are kept at continued application to any kind of employment can never enjoy that sprightliness and vigor, which is one of the chief indications of health,” a young contributor to the Gazette wrote, arguing for more free time. “Their ability to study is diminished.” Punahou students learned that securing beloved native pastimes, such as swimming, required utilizing exclusively Anglo-American arguments.18

In addition to the distractions of its geographic setting, Punahou’s amenities sharply contrasted with parental and teacher messages of cleanliness. Being sent away from the dining room table for one’s dirtiness may have seemed unfair to Punahou boarders, since the bathing pond had a foot of mud on its shallow bottom. Students would stir up the water until it was black. “The result of such a state of matters,” explained one student, is that “he who bathes [does] not derive very much benefit from it.”19 Student newspapers frequently complained about the bathing pond, a source of stress for some children whose parents had long taught them to despise the levels of cleanliness found in indigenous homes. Punahou living, in reality, had more in common with the “dirty kanaka,” in the words of one student, than with the New England standards their parents carried to the islands.20

Punahou also decried nineteenth-century American gender roles. Punahou girls and boys spent much more time together in educational pursuits than many midcentury, middle-class youth in the United States.21 Girls who did not board at Punahou rode their horses to school. Girls served as newspaper editors and contributors and studied Greek. Boys took drawing and music classes. And despite the school’s separate aims to prepare boys to “enjoy the privileges of a college and to study any of the learned professions” and to train girls “for the highest usefulness in whatever station Divine Providence may place,” Dole supplemented this more meager agenda for females by teaching Punahou girls to “render themselves independent of the assistance of others.”22 In this way Punahou School defied educational gender norms in the United States and contributed to the development of the missionary daughters’ pronounced self-assuredness, a confidence seemingly disproportionate to their white minority status within the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Close proximity between genders and extended time away from parental supervision led to peer bonding that often bridged the Puritan gender divide. Punahou girls and boys together visited volcanoes, explored the wilderness, rode horseback around Diamond Head, and visited Waikiki beach. Thirty-four missionary children eventually married each other.23

Upon one gender question Punahou boys remained decidedly orthodox: women should play no political role in civic life. The Punahou Debating Society attacked the question in the early 1850s, concluding that women were too busy in their domestic sphere to “meddle with politics.” Furthermore, the young debaters agreed, the biblical curse precluded a woman from governing a man.24 Only one male student voted in favor of granting women political rights, and it appears no girls were invited to participate in the debate. In this respect Punahou’s gender training mirrored New England values rather than its Hawaiian environment, a strong testament to the influence of missionary teachers and parents. The most influential Hawaiian premiers, since the founding of the Hawaiian kingdom, had all been women, and indigenous women prominently served in the House of Nobles. In 1840, for example, five women sat in the upper chamber. Despite these powerful female examples, the monarch who missionary descendants eventually overthrew was also a woman.25

Proximity among Punahou students also stretched across age. Punahou’s boarding arrangement meant children ranging from ages five to seventeen, and occasionally older, were required to interact as a family, the older students teaching the younger ones and helping them navigate critical childhood years away from home. Reality proved crueler. Students repeatedly reminded each other in their newspapers to be kind to younger students. Ignoring the feelings of younger children, according to the Gazette, is “frequent here.”26 Daniel Dole once admitted that he “dreaded” a new scholar arriving at Punahou, “knowing the seasoning he was sure to go through despite our utmost vigilance.”27 What parents hoped would be a safe haven for their children in the islands was, according to at least one graduate, a harsher experience than arriving alone in the United States for the first time. Bullying and cruelty at Punahou disrupted parental hopes that peer relationships would adequately supplement the missionary family back home. Instead peer culture at Punahou became an independent force pulling on children in new and, ultimately, political ways.28

Perhaps the greatest dichotomy in student learning at Punahou was the persistent loneliness that attacked some students, despite their parents’ hopes that keeping their children in the islands would spare them the difficulties of traveling to and studying in the United States. Missionary children in the Hawaiian Islands often suffered extreme emotional distress from prolonged family separations. Henry Lyman, who attended the school from 1846 to 1853, recalled the first time he visited home: “I could only clasp my mother’s neck, and weep like an infant in her arms.”29 Orramel Gulick (1830–1923), a contemporary of Lyman, reported home to his mother, “I puke once in a while.”30 Gulick’s younger brother Charles died of bulimia in 1854.31 One female student died of a “lingering illness,” perhaps an eating disorder, despite her Punahou teachers’ daily commands that she loosen her corset.32 A female eating disorder would not have been unusual. Missionary Elizabeth Edwards Bishop starved herself to death in 1828, due to an extreme curvature of the spine that made eating painful. Despite the pleas of fellow missionaries, Bishop continued to restrict her diet in an attempt to manage her pain. One lonely student lamented in a school essay, “I once had a happy home.”33

Loneliness among the scholars also was enhanced by dislike of their teachers. The anticipation of seeing school friends after vacations was, in the words of one student, always “mingled somewhat with the fear of Mr. Dole.”34 Dole, one biographer noted, “made it a point never to spare the rod.”35 Also a firm believer in corporal punishment, teacher Marcia Smith was known for “great physical strength.”36 Ann Eliza Clark remembered, “Her punishments were numerous and frequently applied, and her memory is indelibly stamped on the minds of all those who have enjoyed her instructions.” So severe were her memories that Clark, who attended Punahou for only one year, wrote, “I cannot think of her and of those days calmly.”37

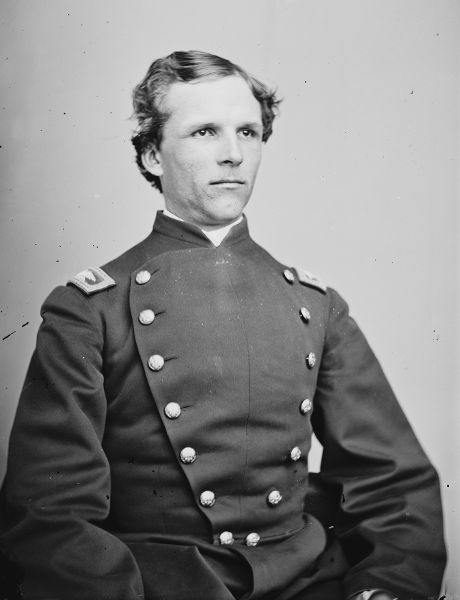

Despite student complaints Punahou School was doing something right, even under Dole, who retired in 1855. Punahou graduates were receiving high honors in U.S. colleges, and even a few American children were moving to Honolulu to attend the school. By 1858 the school had close to eighty pupils. A traveler sighting Honolulu from her ship asked if the city was Punahou.38 “I feel safe in saying that no school equal, on the whole, to [Punahou] is to be found west of the Alleghenies,” boasted William Alexander (1833–1913), who left Punahou in 1849 to attend Yale University. Graduating second in his class at Yale, Alexander asserted, “Only in New England would [Punahou] find a few rivals.”39

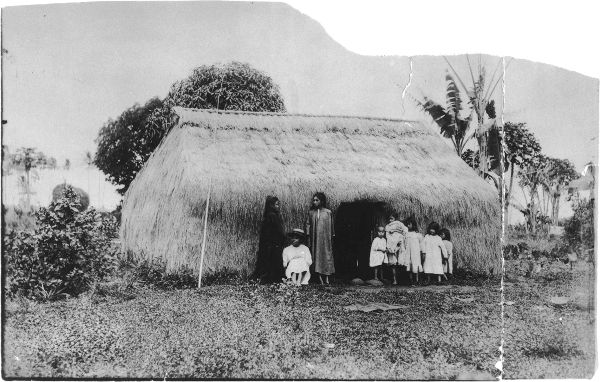

13. Hawaiian children in front of a grass house. Missionary children were not allowed to attend their parents’ schools for native Hawaiians. Instead the white children were segregated from the Hawaiian culture and taught to devalue Hawaiian practice. Mission Houses Museum Library.

More importantly to parents, Punahou students were inheriting the cultural standards of their New England–born elders and preparing themselves for entry into the United States. Few parents in the 1840s and early 1850s saw a future for their children in the Hawaiian Islands and trusted Punahou to make their children’s transition into American culture seamless. Taught by their nineteenth-century American primers, Punahou students believed that deportment constituted character. Biting one’s nails, swearing, lying, and stealing were bad habits one formed in childhood, just as Sabbath keeping, Bible reading, and prayer were necessary for lifelong success. Gambling, billiards, and theater made the list of “don’ts,” as did saying don’t, can’t, and won’t.40 As one student attested, “A person’s character may often be known by the language he uses.”41 Most importantly, missionary children learned that filial obedience was necessary for receiving love. “God loves obedient children, but those who are disobedient he does not love,” one child summarized. When differences between missionary parents and their indigenous hosts arose, it was clear whose side missionary children were expected to take.42

Raising Race

From their earliest memories missionary children were taught to distrust native Hawaiians. Parents built kapu yards within which children played, and from which indigenous people were forbidden. In some missionary homes natives were required to leave the room whenever a child entered. Parents spoke only English to their children. Under no circumstances were missionary children allowed to attend school or fraternize with indigenous children. As a result Punahou School refused to admit indigenous children until 1852, more than a decade after the school’s founding.43 Missionary Dwight Baldwin voiced what nineteenth-century American missionary parents in the Hawaiian Islands all believed: “We must give a knowledge of the world . . . even while we are afraid to have them associate with any of the society around us.”44

Punahou teachers juxtaposed indigenous Hawaiians to the white Americans whenever refining their lessons of proper industry and use of time. Student papers attest to teacher success. Numerous school compositions contrasted missionary diligence with the dreaded “Kanaka fever.” As one student wrote, the illness, also known as “Lazy fever,” could only be cured by “Dr. Industry” or “Dr. Birch.”45 Advocating corporal punishment for indigenous practice, Punahou students transferred their own transgressions against Anglo-Protestant norms onto native Hawaiians. In an essay entitled “Evil Tendencies to be Resisted in Procuring an Education at these Islands,” another student explained that “the indolent habits of the natives” were caused by a tropical climate and the easy availability of food. Students were to pay special attention to these risks, which could threaten their status in the islands as “respectable” members of society.46

Missionary children prized their Punahou education, which set them further apart from the Hawaiian population. As missionary son and Punahou student Samuel Alexander rhetorically asked, “What is man without a cultivated intellect, but a brute, and what are the majority of men, who live along through life, but a drove of sensual asses?”47 Despite the missionaries’ support for numerous indigenous schools, missionary parents could not hide their racism from their own children. Missionaries had designed their native schools to teach the indigenous people a written Hawaiian language and to read a Hawaiian-language Bible. Missionary parents had far loftier goals for their own children, including one day transferring their pastoral and educative responsibilities to their children. As John Gulick noted to his father when Punahou began accepting nonwhite students, “I think perhaps . . . you would find more aversion to such equality than you anticipate, even amongst your good folk.”48

Punahou students reserved in their minds one exception to their parents’ and teachers’ views on race. Born into virtual poverty, supported wholly by the goodwill and donations of Americans they had never met, and surrounded by an extravagantly wealthy indigenous elite who had welcomed their births with open arms, missionary children during the early years of Punahou revered the Hawaiian monarchy. Punahou students had a long association with members of the ali‘i class. In Honolulu several missionary families sent their children to the Hawaiian Chiefs’ Children’s School (called the Royal School after 1846), prior to their transfer to Punahou. The Royal School, under the administration of missionaries Amos and Juliette Cooke, was designed to teach Hawaiian chiefs and chiefesses the English language, and of the sixteen Hawaiian royal children who boarded at the school, five became Hawaiian monarchs.49 Students at the Royal School formed significant attachments with missionary children. Elizabeth Judd wrote that the king’s sons Lot Kamehameha and Alexander Liholiho “came to our house daily, where we read, sang and played together.”50

At Punahou students also came into contact with young Hawaiian royalty. Henry Lyman remembered the “cavalcade” of young chiefs who visited the school. “The vivacious young chieftains, resplendent in blue broadcloth and gilt buttons, always made a profound impression on our barefooted squad,” he wrote.51 The two schools would organize wrestling matches and running races in which the missionary children often lost to the six-foot-tall Hawaiians.52

Missionary children respected the authority of the Hawaiian monarchy and the grandeur of their Hawaiian schoolmates. Prince Alexander, for instance, had a retinue of twenty-five servants at the Royal School.53 Punahou students accepted the wealth, privilege, and physical prowess of their future monarchs and admired their skills in memorization, oration, and languages. This respect must have been communicated to the young chiefs, for Lot was shocked when called “nigger” while visiting the United States. “Lot never forgave or forgot it,” Elizabeth Judd noted.54

Missionary children seemed oblivious to these inconsistent attitudes toward native Hawaiians. From its outset Punahou School employed Hawaiian natives, who lived in separate quarters while maintaining the campus and serving the students. Opuni worked in the Punahou kitchen for ten years. Kahui, the campus carpenter, guided the boys on hiking trips.55 Yet in four years of weekly Punahou student newspapers, only a handful of contributors refer to non-ali‘i Hawaiians by name, and only one in a positive manner. “There is now on the Island of Kauai an old woman who was my nurse in younger years,” the young author wrote. “I have no doubt but that she would make any sacrifices on my account. That she would risk her life and go through any danger for my sake.” Despite this praise, the Weekly Star writer apologized: “I do not mean however to say that the Hawaiians are not degraded.”56

Missionary children’s acceptance of Hawaiian elites also extended only so far. While at least six missionary children eventually married native Hawaiians, Punahou student Charles Judd (1835–90) voiced what many of his peers believed: “Do you think I would marry a girl with native blood? . . . [F]ar from it.”57 Judd was discussing the future Queen Emma. Warren Chamberlain neatly summarized where Punahou students obtained such attitudes, noting in 1849—nearly thirty years after missionary arrival to the islands—that missionary parents thought the amalgamation of their white children and native Hawaiians “repugnant.”58

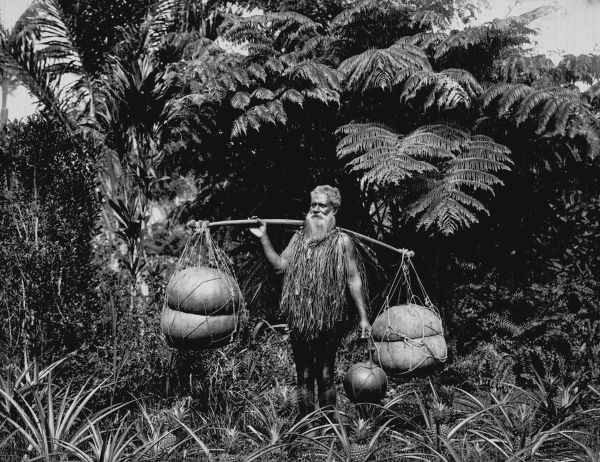

14. Hawaiian man carrying calabashes. Native Hawaiians were instrumental to missionary families. Fetching water, growing food, and washing clothing were just a few of the tasks for which missionaries relied on their indigenous servants. Hawaiian missionaries also used indigenous Hawaiians as wet nurses and nannies for their infants. Mission Houses Museum Library.

The “Cold Water” Army

Issues of race and class infused the cultural understandings of nineteenth-century missionary youth in the Hawaiian Islands. The children viewed their own whiteness, as well as their parents’ close association with the Hawaiian monarchy and ali‘i class, as distinct identifiers that separated them from the majority native population. Yet missionary children also united around a shared moral code, the prize missionary parents hoped to earn for their children by sending them to Punahou. During Punahou’s earliest decades, one Anglo-Protestant value surpassed all: temperance. On every island missionary children joined temperance societies, attended temperance meetings, and debated all facets of the issue. George Wilcox, who attended Punahou throughout the 1850s, remembered joining a temperance society when he was three years old. Influenced by the American temperance movement, some missionary children also joined the “cold water army” and refused to drink coffee or tea.59

So serious were Punahou students regarding the evils of intoxicating drink that in 1846 debaters unanimously voted rum “productive of more evil than war.”60 Missionary children were taught that the “free circulation of spirituous liquors” lessened respect for law, life, and property. Under the influence of the missionaries, thousands of native children also joined temperance societies.61 At Punahou students learned that alcohol was destroying native lives and culture. “I have not much fear in saying that if it were not for the restraining influence of the present stringent laws with regard to liquor and the good influence of the missionaries,” wrote a student in the Weekly Star, “that they would soon dwindle away to nothing.”62

With the missionary children’s hatred of liquor came a distrust of foreign visitors. Missionaries had long influenced native rulers to legislate against prostitution and drunkenness—vices encouraged, the missionaries argued, by foreign whalers, merchants, and naval sailors. Missionary son Sereno Bishop noted that almost all foreigners in Honolulu during the first twenty years of the mission were at odds with the missionaries.63 This ongoing conflict grew stronger when Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) issued a law against drunkenness in 1835 and outlawed liquor distillation and importation in 1838. The king also imposed the first Hawaiian duty, a tax on wine imports.64

Kamehameha III also sided with the American missionaries on Protestantism, forbidding Roman Catholic missionaries from operating in the islands. As a result of his policies, the nation faced in 1839 the first threat to its independence. Arriving in Honolulu the French frigate L’Artemise brought demands from the French government: religious toleration for French Catholic missionaries, as well as limits on Hawaiian duties for French wines and brandies. Kamehameha ultimately acquiesced to French demands, effectively repealing his own liquor laws.65 To the missionary families, Catholic priests and alcoholic imports represented the worst sort of foreign aggression. As one Punahou student revealed, “Those who have visited these shores are worse than the Hawaiians themselves.”66

Of the foreigners increasingly coming to shore, most Punahou students directed their animosity toward the French, whose invasive actions were directly related to the two things their parents most abhorred: liquor and Roman Catholicism. In 1840 Persis and Lucy Thurston’s father refused to leave his post and travel with his daughters to college in the United States because “two Catholic priests ha[d] lately established themselves at Kailua.” He never saw Lucy again. His daughter contracted a respiratory infection upon arriving in America and died a few weeks later.67

Thurston was not the only missionary father concerned with French influence. “Popery and Brandy, as you will see are at the bottom of this whole affair,” Ann Eliza Clark’s father wrote to the ABCFM board regarding the 1849 incident with France. Punahou students generally agreed with their parents, decrying French influence in the islands. The missionary children never predicted that future Hawaiian monarchs would willingly choose to reverse the course their parents had charted for the islands.68

God Save the Queen

By 1865 many missionary descendants were choosing to remain permanently in the islands. Kamehameha III had opened the doors to private land ownership, and the American Civil War had boosted Hawaiian agriculture. Missionary children saw, for the first time, an economic future for themselves in the islands.

Missionary descendants also began to notice the Hawaiian monarchy’s progressive repudiation of their parents’ missionary efforts. Kalākaua, whose reign began in 1874, distanced his government from the American missionaries and their children by joining the Anglican Church and reinstituting native religious practices. By reviving genealogical meles (chants), promoting the hula, and redirecting the Hawaiian Board of Health to license kāhuna (native healers), Kalākaua solidified the origins of chiefly power, importance of indigenous ceremonies, and possibilities of priestly medicine. Kalākaua’s reign was further marred, in the eyes of the missionary families, by his close association with Walter Murray Gibson, a Mormon.69

“Church-going among the Hawaiians is now about as rare as staying away used to be forty years ago,” missionary son and Punahou graduate William Castle (1849–1935) lamented in 1881.70 Castle was right in one respect. The American-founded Congregational church in the islands had lost its hold on the government and the people. By 1896 there were almost as many Catholics as Protestants in the islands, and the number of Protestants included Anglicans. Fully one-sixth of the population adhered to Mormonism.71 The years of Kalākaua’s rule, wrote missionary son and Punahou graduate Joseph Emerson (1843–1930), “mark the lowest stage of corruption reached in church and state in these islands.”72

Kalākaua’s support for removing liquor restrictions, licensing the sale of opium, and chartering a lottery company were untenable political positions to white Punahou graduates, and missionary descendants experienced a major defeat in 1882 when the Hawaiian legislature eliminated prohibition for native Hawaiians. The restriction on giving intoxicating drink to Hawaiian natives had been in place for over three decades and came with steep fines or imprisonment for those who broke the law. In 1886 the Hawaiian legislature further voted to allow the licensing and sale of opium.73

William Alexander—who graduated from Punahou School in 1849 and served as the school’s president from 1864 to 1871—asserted in his History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the Revolution of 1893 that opium licensing and its related scandals were directly responsible for the revolution against the Hawaiian monarchy.74 In 1887 a group calling itself the Hawaiian League demanded through armed force that Kalākaua sign a new constitution that removed his powers to appoint the upper house of the legislature and made his executive cabinet responsible only to the legislature. Of the known organizers of this secret league, all but one had attended Punahou. All were members of American missionary families.75 “The mad plunge into the abyss was suddenly arrested by the determined efforts of Hawaii’s most faithful sons and friends,” Joseph Emerson declared. The new legislature immediately revoked the opium licensing law and prohibited the sale of opium in the islands.76

Queen Lili‘uokalani took her brother’s place after his death in 1891. She reigned for less than two years. An Anglican like her brother, Lili‘uokalani signed new opium licensing legislation and a lottery bill, while presenting to the nation a new constitution, which would restore the monarchical powers lost by her brother and suppress white political power through enlarging the indigenous electorate.77

While the influence of white business and agricultural interests would certainly have been checked by the queen’s efforts to restore the powers of the monarchy and increase the voting influence of the indigenous population, more worrying to missionary descendants was her rejection of their parents’ moral and religious values, passed down in missionary homes, reinforced at Punahou, and commended in New England colleges.78 Of the twenty-eight men on the Committee of Public Safety that overthrew Lili‘uokalani in 1893, more than one-third were Punahou graduates. Sanford Ballard Dole, the son of Punahou principal Daniel Dole, led the revolution and served as the new Hawaiian Republic’s first president.79

Trampling Down the Vineyards

Punahou graduates encouraged each other during the political struggles of the late nineteenth century. Just as their Punahou teachers had done in the classroom, missionary children as adults contrasted their own moral training to the immorality of the indigenous nation. “What now may we naturally expect from the descendants of the American Missionaries?” asked Hiram Bingham Jr. “They have been, are now, and will be trained in the highest schools of the nation.”80 Who better than to lead the nation, Punahou graduate Samuel Damon argued, than the missionary descendants? “In the midst of this new world stands our own group, undoubtedly called to be of influence in the propagation of great and noble ideas,” Damon surmised.81 The growth of the Roman Catholic Church, influence of British Anglicanism and American Mormonism, and resurgence of monarchical support for native religion, liquor, gambling, and opium brought the Punahou graduates to their breaking point.

15. Missionary son William Dewitt Alexander (1833–1913) attended Punahou School, graduated from Yale University, and returned to Punahou to serve as a teacher and president. After the revolution, Alexander became minister of public instruction for the Hawaiian Republic and wrote A Brief History of the Hawaiian People (1899) for use in the public schools. In the preface Alexander professes to write his history from the perspective of “a patriotic Hawaiian.” Alexander married missionary daughter and fellow Punahou student Abigail Baldwin (1833–1913). Mission Houses Museum Library.

16. Queen Lili‘uokalani. Mission Houses Museum Library.

The missionary children’s outcry against native Hawaiian rule did not occur overnight. Punahou School with its parental directives and secluded environment nurtured a culture that fostered peer networks and utilized peer pressure to reinforce the white minorities’ social morals. Vulnerable children, themselves a colonial battleground, lived isolated from the culture of their birthplace and separated from their parents. Formal authoritative structures and informal peer networks instead worked in tension at Punahou to replace traditional familial and community bonds. Through peer culture, students creatively engaged their social world by publicly critiquing each other’s work. These “intensive negotiations with and among the students” created what Yitzak Kashti calls a “profound experience of culture.”82 It is not surprising that in such an environment discussions turned political. As one graduate remembered, “What profound discussion we used to have concerning ‘the powers that be.’”83

White missionary children in the islands coalesced around each other in the decades following their Punahou experiences. Education served as an additional marker to race and religion. Punahou remained a solid indicator of deportment and class, a divider, missionary descendants argued, between those capable of moral and political leadership and the outsiders who were to follow them. That Punahou students would be leaders in the islands the graduates did not question. “Who are better qualified . . . than the children of those who first brought light to the land?” James Alexander (1835–1911) asked.84 That they would always respect the monarchy was less certain. “We are all as yet good and loyal subjects to his majesty,” fifteen-year-old Robert Andrews noted in 1852. When the opportunity came for Punahou graduates to choose sides, they chose revolution.85

Samuel Chapman Armstrong (1839–93)

This revolutionary mindset traveled with the missionary children around the world. Perhaps the best example of Punahou’s early and extensive influence is found in the legacy of missionary son Samuel Chapman Armstrong. Armstrong attended the school during its first two decades before traveling to the United States to attend Williams College. When the American Civil War broke out, Armstrong joined the Union Army, earned his U.S. citizenship, and, after the war, founded Hampton Institution to educate former Southern slaves.

In his last report to the Trustees of Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Armstrong estimated that close to 150,000 pupils had been reached by Hampton teacher-graduates during the twenty-five years following the Civil War.86 More importantly, Armstrong’s message of racial uplift through manual labor was adopted by mentee Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute, hundreds of secondary schools in the rural South, and U.S. educators in colonial Hawai‘i, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Many have argued that Armstrong set in motion a system of training that would dominate U.S. educational models for minority and colonial populations for one hundred years.87

Nevertheless, Armstrong’s application of manual labor for freed slaves was distinctly rooted in his personal experiences at Punahou and the racialist ideas he and fellow missionary sons and daughters developed as children in the islands. Armstrong explained: “The [N]egro and the Polynesian have many striking similarities. Of both it is true that not mere ignorance, but deficiency of character is the chief difficulty, and that to build up character is the true objective point in education. It is also true that in all men education is conditioned not alone on an enlightened head and a changed heart, but very largely on a routine of industrious habit, which is to character what the foundation is to the pyramid.”88 One can almost hear the earlier battle cry of Armstrong’s Punahou instructors in his philosophy of education, as Armstrong urged his charges to appreciate the twin habits of industry and scholarship.

Teaching Revolution

American missionary parents in the Hawaiian Islands never intended their children to acculturate into indigenous Hawaiian society. Their educative efforts were strictly designed to train their children to assimilate into American society or lead the Hawaiian kingdom in its spiritual and cultural regeneration, a process missionaries designed from the beginning to reflect nineteenth-century, Anglo-Protestant ideals. While parental efforts remained incomplete, and missionary children maintained a sense of bicultural identity throughout their lives, the segregated nature of their education and their asymmetrical opportunities for advanced education separated them from the larger indigenous society and caused them to form peer attachments almost solely within their racial and religious communities. When these communities appeared threatened by Hawaiian monarchs, the children reacted violently.89

17. Samuel Chapman Armstrong (1839–93). Born in the islands and educated at Punahou School, Armstrong attended Williams College in Massachusetts before joining the U.S. Army and fighting in the American Civil War. After the war Armstrong founded Hampton Institute in Virginia. Image ca. 1860–70, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpb-05892.

18. Students studying soil formation at Hampton Institute, ca. 1898. At Hampton Institute Samuel Chapman Armstrong combined the manual labor experiences of his childhood at Punahou School with his military training in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Library of Congress, Johnson (Frances Benjamin) Collection, LC-USZ62-62379.

Ironically, parallel missionary efforts in Honolulu to separate indigenous children from their Hawaiian caretakers and inculcate them in New England Calvinism and Anglo-American deportment fell far short of missionary goals. After teaching ten years at the Royal School, the Cookes had witnessed few—if any—Christian conversions. Historian Linda Menton argues that the ali‘i children probably did not “internalize the values taught at the school” because they were not isolated from the indigenous Honolulu community.90 Hawaiian caretakers could always be found on the other side of the wall surrounding the school, often weeping over the separation.91 White boarders at Punahou had no similar familial outlets for escape. Instead, they turned toward each other and formed their own army of resistance against the indigenous vices that so occupied their parents’ attentions.

Punahou School during the 1840s and 1850s provides an example of the highest educational ideals accomplished within a relatively impoverished setting. Missionary parents struggled to pay their children’s board, and Punahou children worked in the school’s fields to help supply enough food for boarders. That numerous Punahou graduates went on to attend elite U.S. institutions such as Harvard, Mount Holyoke, Williams College, and Yale testifies to the resolve of white parents, teachers, and students in the islands. Nevertheless, Punahou graduates entered Hawaiian civil society with tremendous baggage. Their racialist understanding of morality and culture limited their ability to work with their indigenous Hawaiian neighbors. It is not surprising that white colonial childhood in the islands included such complicated messages. More surprising are the significant efforts missionary children undertook to connect their religious beliefs to political values and, eventually, to revolution—an agenda that went far beyond what their missionary parents had arrived in the islands to accomplish. The 1893 political overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani reflects the ability of missionary children in the Hawaiian Islands to appropriate their religious upbringing into a political plan tailored to fit their colonial experience as white, privileged minorities living in a nineteenth-century Christian missionary field.