4

Cannibals in America

U.S. Acculturation and the Construction of National Identity in Nineteenth-Century White Immigrants from the Hawaiian Islands

Ye parents who have children dear, and ye, too, who have none, if you would keep them safe abroad, pray keep them safe at home.

English nursery rhyme1

From birth I was cast upon you; from my mother’s womb you have been my God. Do not be far from me, for trouble is near and there is no one to help.

A Psalm of David (22:10–11)2

American assimilation has seldom been rapid or absolute, but its complexities have often been ignored. In the nation’s earliest period of immigration following the American Revolution, immigrants were usually merchants, tied to bilateral trade agreements and paying for passage aboard trade ships traveling the Atlantic Ocean. Predominantly European, these early “passengers” were usually overlooked and almost never feared once entering the United States. By the mid-nineteenth century, this had changed. American merchants, freed from restrictive mercantile trade practices with Britain, had discovered the Pacific Ocean and shattered the myth of American isolation, as well as the invisibility of immigration. New racial theories based on Darwin’s theory of natural selection fell on the heels of U.S. entry into the non-Atlantic world, and just as Americans traveling abroad had little desire to forsake their U.S. citizenship, Americans at home coupled their expanding knowledge of the non-European world with fears that Pacific-based immigrants to the United States would threaten American cultural values at the very time Americans were attempting to transport their cultural institutions abroad.3

American missionaries to the Hawaiian Islands were among the earliest waves of Americans living, trading, and proselytizing abroad, and their children were among the earliest foreign exchange students to attend U.S. colleges. The story of ABCFM missionary children entering the United States in some ways supports and in other ways belies studies of nineteenth-century U.S. immigration. As immigrants, missionary children quickly realized American culture was different from their own. The children negotiated this new landscape largely alone, depending upon “chain migration” for emotional and even physical support. And despite their parents’ desires to make them Americans, missionary children demonstrated the complex and often ambiguous acculturation process that confirms what historian Paul A. Kramer notes as the limits of U.S. cultural transmission through international college exchange.4

Many missionary children utilized their American educations and positions in U.S. society to advocate U.S. policies that benefited their families back home. Many returned to the Hawaiian Islands and participated in political revolution. Yet two events stand out in complicating these immigration stories. The 1809 arrival of the Triumph to the United States and the 1861 outbreak of the American Civil War both demonstrate that nineteenth-century immigrants from the Hawaiian Islands also affected the course of U.S. history.

Dull Strangers

The first children to immigrate to the United States from the Hawaiian Islands were native Hawaiians. Not only did young Henry Obookiah influence American missionary interest in the Hawaiian Islands, but he also set in motion the chain of events that led to the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and the U.S. annexation of the islands. Born around 1792, Obookiah witnessed as a young boy the violent deaths of his parents and infant brother in interisland struggles for ali‘i dominance. Desiring to leave the islands, Obookiah found refuge with an American ship captain, who transported him to the United States on board the Triumph. When he arrived in 1809, Obookiah was around seventeen years old, a child by nineteenth-century legal standards.5

Obookiah initially was not well received. Viewed by New Englanders as “unpromising,” his countenance “dull and heavy,” Obookiah desired to assimilate. It was his ability to learn English that changed the minds of those around him. Eager to learn, Obookiah soon attracted the attention of members of the newly formed ABCFM, who sought Obookiah’s company on their 1812 trip around the United States to raise funds for foreign missions. Because he did not yet consider himself a Christian, Obookiah’s presence on the trip was meant to solicit sympathy and, of course, donations.6

Most significant in Obookiah’s recollections of his early experiences in the United States was his desire to become a Christian in the way he had been taught, which meant gaining membership in a New England Congregational church. When he and his Hawaiian shipmate Thomas Hopu prayed together for the first time in their native language rather than in English, Obookiah recorded their surprise in his journal: “We offered up two prayers in our tongue—the first time that we ever prayed in this manner. And the Lord was with us.” One week later Obookiah began to plan his return to the Hawaiian Islands to preach “the religion of Jesus Christ” to fellow Hawaiians in their language.7

Despite the ABCFM’s efforts to educate Obookiah and raise funds to return him to the islands, Obookiah died of typhus fever in 1818. When his memoirs were published the following year, they sold over fifty thousand copies and required twelve editions. Reading his story in 1819, a group of young college graduates decided they needed to complete Obookiah’s mission, and the ABCFM’s first company of missionaries to the Hawaiian Islands left the United States the same year. While Obookiah’s friend Thomas Hopu was on board the ship transporting the seven white missionary couples, the ABCFM had clearly replaced Obookiah’s goal with a new directive: the permanent settlement of American missionaries in the Hawaiian kingdom.8

Superior Adventures

During the 1820s and 1830s missionary parents in the Hawaiian Islands sent almost all missionary children back to the United States by the time they reached age seven. Missionary mother Mercy Whitney explained parental reasoning to her children: to capture “advantages far superior to what you would have had at the Islands.”9 Missionaries recorded many of these parting scenes, including one daughter who screamed from the deck of her ship, “Oh, father, dear father, do take me back!”10 Missionary parents often made the situation worse by advising their children that they might never see each other again. Indeed, some did not. Whitney, for example, never saw two of her four children again. While nineteenth-century parents in the United States often chose familial separation in order to secure an education or apprenticeship for a child—and had the legal authority to do so—the length of time and the distance missionary parents were willing to put between themselves and their very young children were extreme. That so many missionary parents chose separation from their children demonstrates the power the missionary occupation held over their children’s lives.11

For the missionary children who traveled to the United States without a parent or guardian, the six-month voyage could be terrifying. Even for American whalers and merchants, traversing the Pacific was a relatively new experience. U.S. trade with China increased after the American Revolution, but Americans had little to offer the Chinese until they discovered that sandalwood from the Hawaiian Islands and seal furs from the Pacific Northwest could help equalize exchange rates. American whalers also began entering the Pacific, as whale oil became a popular lubricant in the growing number of factories and as a better-smelling source of light. The Hawaiian Islands made it possible for Americans to buy sandalwood from the Hawaiian monarchy in order to trade for Chinese goods and resupply whaling and sealing vessels for excursions into the North Pacific.12

19. Henry Obookiah. Mission Houses Museum Library.

These Pacific trading ventures brought the first missionaries to the islands in 1820 and took missionary sons Warren and Evarts Chamberlain back around Cape Horn in the 1830s. The boys were ages seven and five. Even at the end of his life, Warren remembered with terror the “monster wave” that filled their cabin one night while they slept.13 Samuel and Henry Whitney, ages eight and six, remembered being left by their parents under the supervision of an “unkind captain.”14 Henry Obookiah noted the hazing he received from sailors, as well as the general discontent among the crew. Judging from Obookiah’s account, as well as lawsuits filed by sailors over inadequate food and water provisions, starvation was a constant concern for sailors on lengthy Pacific voyages. The memoirs of former cabin boys who recounted the physical abuse and neglect they experienced aboard nineteenth-century American merchant and whaling vessels suggest that it would be surprising if missionary children did not experience similar food shortages or mistreatment during their half-year voyages.15

Missionary children would have understood the irony of their situation. One of the most vexing attributes of Hawaiian society for missionary parents was its lack of nuclear fidelity. Hawaiian marriage traditionally had been rare outside of the ali‘i class, and children often changed hands, adopted by grandparents and others.16 English travel writer Isabella Bird noticed that despite the “capriciousness” of familial ties, Hawaiians were “remarkably affectionate to each other.”17 These relationships, while valued by Hawaiians, were shocking to Americans. Missionary parents who gave up their children, while attempting to teach the Hawaiians to keep their own, demonstrated an amazing ability to compartmentalize their lives.

Missionary parents expected their own children to rejoice in their opportunity to leave the islands to pursue superior advantages in the United States. Advised that the United States was a bastion of religious and educational opportunities, children were admonished by parents to “value your privileges, and to feel grateful for them.” Perhaps one day, Samuel and Mercy Whitney wrote their sons, you will be able to “thank your Parents who were willing to part with you.”18

20. Sophia Mosely Bingham (1820–87) was born the same year the first ABCFM missionary company arrived in the Hawtaiian Islands. She was eight years old when she arrived in the United States to live with relatives. Mission Houses Museum Library.

Trafficking in Children

Missionary children, most of whom were not U.S. citizens due to their birth outside the United States, traveled without currency. Their parents had none. Like the earliest “passengers” across the Atlantic, these children were, in fact, commodities, traded by missionary parents to host families and colleges and expected by parents to be received with reverence and care. Like the textiles, ceramics, and teas making their way from China to Boston and New York, missionary children were a novelty, providing a translation of the Pacific to those whose curiosities had been aroused.19

Because missionary parents had eschewed personal property, as well as monetary income, their children entered a nation in which they had no independent legal standing and little ability to earn money. By the 1820s the “assumption of the law had shifted to deny the identity of a child altogether, up to age twenty-one,” historian Holly Brewer writes. “The father had to contract on the child’s behalf.” Employers had little interest in entering into labor or property agreements with missionary children under the age of twenty-one, since such contracts would not be recognized in court, and children would not be held liable for broken agreements.20

Consequently, missionary parents placed their children into the hands of the ABCFM board. In 1834 the board began to grant small annual stipends to ABCFM missionary children attending U.S. schools. Until then, missionary children, usually between the ages of six and ten, entered a foreign nation literally destitute and alone. Missionary parents relied on the ABCFM to make sure their children found and maintained proper placement. If no sympathetic supporter could be found, children were, in essence, sold to strangers, the board providing portions of the child’s allowance to their guardians as needed.21 Board secretary Rufus Anderson argued that the system “with few exceptions” worked.22

The exceptions, according to Anderson, were “owing to causes which experience will remedy hereafter, or against which no human wisdom can provide in this imperfect world.”23 Such analysis probably was not comforting to the children of whom he spoke and who, like other immigrants to the United States, experienced the first rumblings of American distaste for foreigners. In 1819, the same year the ABCFM sent missionaries to the Hawaiian Islands, Congress placed its first restrictions on Atlantic passenger trade. The Act Respecting Passenger Ships and Vessels (Steerage Act) limited the number of people allowed passage on merchant ships to two persons per five tons. Atlantic seaboard states attempted even more restrictions, causing the Supreme Court to rule that only Congress could regulate foreign commerce. It was a divided court and a controversial decision, as states argued their own resources were being depleted to support newly arriving foreigners. The difference in the case of missionary children from the Hawaiian Islands, is that their parents—U.S. citizens—were among the first to send their poor and uneducated to the United States—the very action Americans feared foreign governments of plotting.24

The effect of ABCFM policy toward missionary children was to commodify missionary childhood. The success of the missionary parents’ plans for their children depended upon their children being well received by the American public. Two things were required: to project the horrors of childhood in the Hawaiian Islands and to display the successes of their children as they submitted to an American education. This rate of exchange, in turn, provided missionary children with a free education, as well as the necessities of life. For some the exchange rate proved too high. “You probably think I live fancy as I board myself,” James Chamberlain wrote to his sister. “Crackers and water is my principal diet.”25 Seven-year old Warren Chamberlain was entrusted to a farmer who required him to rise nearly four hours before dawn, in order to get his chores done before school. “I sleep on straw because . . . there is not a mattress in the house to sleep on,” Chamberlain wrote his parents. When a physician advised Chamberlain that the difficult farm work was damaging his health, Chamberlain moved, “as Mr. W. would not keep me without reducing my wages.”26

Situations such as the Chamberlains were common. Missionary children often were bounced around once inside the United States. Since correspondence between parents and children also took six months, parents sent letters to their child’s last known address only to hear six months later that the child had moved families, schools, or even states. Even living with relatives was not always the optimal situation. Maria Whitney, shipped to the United States at age six, was passed from home to home, her relatives deeply disapproving of her parents’ decision to send her to them and only agreeing to accept the burden of caring for Maria for short periods of time.27 Sophia Bingham’s guardian believed that the girl’s relatives had overindulged the eight-year-old upon her arrival to the United States and spent the next several years attempting “to counteract” the attention Sophia had received.28

The psychological costs of such a system were steep. “You will never find persons who will answer the part of parents after you have once left them,” Warren Chamberlain wrote his sisters. “Our experience before you convinces us of this.”29 Martha Chamberlain (1833–1913) wrote her mother asking for money so that she and her sister could leave their American home. “Dr. Anderson’s family is no home for us,” Martha wrote. She was referring to Rufus Anderson, the ABCFM secretary responsible for the placement and care of all ABCFM missionary children entering the United States.30

It is not hard to imagine confusion among missionary children over the dictates of a religious faith that required so much sacrifice at such a young age. In turn children were expected to display gratefulness to their parents and American donors for their position. Warren Chamberlain wrote to his sisters regarding relatives with whom he had briefly stayed: “I would not hurt mother’s feelings, if it were possible, and I will not say everything that impresses my mind.”31

Instead missionary children acted out in other ways. Some refused to write to their parents, forcing siblings to communicate basic information on their behalf. Others expressed their dissatisfaction more subtly. When Mercy Whitney eulogized her husband as “a Father to them all,” she was referring to the indigenous Hawaiians.32 Henry Whitney responded by naming his firstborn son after his American guardian.33 Maria Whitney, sent to the United States like her brother, returned to the islands sixteen years later but refused to live with her mother and married without her mother’s consent. “She manifests but little affection for, and still less confidence in me,” Mercy Whitney complained. “This seems strange . . . and I cannot account for it, unless I attribute it to her long absence from me.”34

Others satirized their responsibility to convey the perceived awfulness of life among the native Hawaiians. People came daily to visit Persis and Lucy Thurston’s trunk of Hawaiian “curiosities.” Persis chose to deal with the scrutiny by dressing in native Hawaiian clothing and parading around the curious visitors.35 She later did the same for peers at Mt. Holyoke Seminary, conducting a missionary prayer meeting in the Hawaiian language and “in the style of the Islanders, with white long gown, long shawl made of the bark of trees . . . a necklace of human hair taken from the head of captives.” Wearing jewelry made of whale and swine teeth, Thurston was, in the words of one observer, “truly comical to see.”36 Missionary daughter Elizabeth Judd dryly recalled her invitation to speak to the hundreds of “eager faces” who had turned out to hear “the woman from the Cannibal Islands.”37

Missionary children also rebelled against their parents by heading to California. “To our great surprise, we have just heard, that Asa Thurston, son of our honored brother Thurston, is digging gold in California!” one missionary father noted in 1849. “I should hope that none of our children at the Islands will be led in that direction.” Thurston was a student in the United States when gold was discovered in California.38 Missionaries reminded their children about the dangers of pursuing money. “The way of life is filled with temptations,” missionary Abner Wilcox told his son Charles, “more I fear in California than elsewhere.” Charles Wilcox disagreed and soon moved there.39

With California gold rushers spending winters in Honolulu, and Honolulu residents heading to California, the financial world had shrunk overnight. “I will go to California and worship the golden calf for one brief year,” a missionary son announced before leaving Punahou School for the United States.40 His friends followed him. John Gulick convinced his parents to allow him to visit Oregon missionaries, only to immediately head to San Francisco and mine for gold.41

California was not the missionary parents’ ideal America. Education, not gold mining, Fanny Gulick wrote her son in California, “is the first object.”42 The California gold rush had, however, placed San Francisco at the center of Pacific commerce. By 1850 missionary children and mail from the islands were able to travel to New York through San Francisco, overland to Nicaragua, and up the Atlantic coast, a journey of weeks, not months. Later companies of ABCFM missionary parents benefited from these changes, utilizing California as a mechanism to keep better tabs on their children in the United States.43

As a result of increasing U.S. contact with the Hawaiian Islands, missionary children failed in their most significant effort to subvert parental demands: the redefinition of their parents’ understanding of a successful education. Despite familial tensions created by distance and time, missionary parents maintained a profound grip on their children’s choice of professions. While allowing their children to pursue whatever course of “usefulness” God unveiled to them, missionary parents made clear to their children that becoming a missionary was the highest status one could attain. “Above all,” missionary Peter Gulick wrote, “I desire that [my children] become faithful and devoted missionaries.”44 When Lucy Thurston’s youngest child returned to the Hawaiian Islands as an ordained minister, years of familial separation melted away in an instant. “A son! Qualified for the gospel ministry,” she gushed. “It is enough.”45

In the face of such expectations, missionary children faced an uphill battle in reclaiming the “useful” life. James Chamberlain wrote to his mother that he wanted to become an artist. Chamberlain’s conviction did not last long in the face of parental criticism. He became a minister.46 Parents squashed several other dreams by correspondence. John Gulick asked permission to become a scientist, and Evarts Chamberlain (1831–82) a sailor: “I was born on an Island. I have sailed thousands of miles on the Ocean, and I have seen some storms that made the ship rock like a cradle,” Evarts wrote his parents. Both children were rebuked. Gulick became a missionary. Evarts Chamberlain, after numerous professional failures, settled for journalism.47 Even forty years later, James Chamberlain reflected, “I ought to have been an artist.”48

Warts and Winters

The stakes for missionary parents sending their children to the United States were enormous. Their ability to maintain their chosen missionary profession in the Hawaiian Islands rested with the continued goodwill of the Hawaiian people and financial support of the American public. Missionary children became the currency by which Americans understood the value of the missionaries’ efforts. Missionary parents viewed their children’s failures as their own, and in no greater arena were the successes and failures of their children on display than in New England colleges and seminaries.49

21. Jeremiah “Evarts” Chamberlain (1831–82). Named in honor of an early leader of the ABCFM, Chamberlain spent much of his life between locations and occupations. He traveled to the United States unaccompanied by an adult when he was only five years old. Chamberlain wanted to be a sailor, but his mother would not allow it. He served in the U.S. Army on a Mississippi steamboat during the Civil War, wrote a novel that failed to sell, and returned to the Hawaiian Islands only to leave them again. Evarts’s siblings noted that he was unsettled and discontent for much of his life. Mission Houses Museum Library.

Missionary parents expected their college-age children to demonstrate that they were capable of assimilating American standards of success, despite their birth in the Hawaiian Islands. Missionary children were also expected to display a desire to return to the islands to complete their parents’ mission to the Hawaiian people. These two goals were often at odds. Americans themselves were entering into a debate about whether those born outside the United States were capable of assimilation. Americans were newly independent and deeply sensitive about their relative position within the “civilized” world, and as Kariann Yokota explains, “American intellectuals linked cultural aspirations to an object already in their possession: whiteness.”50

Yet there was some confusion among U.S. and British elites about how well whiteness would survive in the more hostile environment of North America. “It was hoped and sometimes legislated, that whiteness was an object that could be possessed but not lost or transferred,” Yakota writes. The relative geographical relationship to centers of power “determined how others perceived their level of ‘civilization.’” While missionary parents had been born in New England and educated in Boston, Andover, and New York, their children had been born in the Hawaiian Islands. It was unclear to the new purveyors of race what impact this had, although their belief remained strong that over time even “savages” could become refined.51

As American intellectuals argued ways to secure their status of whiteness outside the British Empire, Congress succumbed to popularized views of national hierarchy and racial inferiority. Westward expansion became critical to linking U.S. trade in the Pacific to centers of power on the East Coast, but American legislators became increasingly hesitant to allow nonwhite immigrants from China, Japan, and the Hawaiian Islands the same legal protections that immigrants crossing the Atlantic had enjoyed.52

When the United States settled its Oregon boundary with Britain in 1846, hundreds of Hawaiian laborers, formerly employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company, sought U.S. naturalization. They were denied by Oregon’s territorial governor under legislation limiting citizenship to white males. When Hawaiian Islanders sought Oregon Territory land grants from the U.S. federal government, Oregon’s territorial delegate to Congress argued vehemently against including Hawaiians, whom he considered “a race of men as black as your negroes of the South, and a race, too, that we do not desire to settle in Oregon.” In 1852 the California senate passed a resolution to restrict the entrance of kanaka laborers. In 1866 the Oregon legislature declared it illegal for a person with one-fourth kanaka blood to marry a white person.53

Missionary children were aware of these debates and desired to prove their membership among civilized races. Punahou students, for example, became upset by news that American visitors reported the students a “more lazy and shiftless set than almost any school in New England.”54 Seventeen-year-old Lucy Thurston, on her way to the United States, worried, “The children of missionaries who have returned from the Sandwich Islands . . . are found fault with for their excessive indolence. . . . All those who return in this vessel will of course be criticized.”55 As missionary children from the Hawaiian Islands began to win top academic awards at schools such as Williams College and Yale University, the New York Observer would only call their success “curious.”56

Missionary children worked hard to dispel such perceptions. In this respect they joined in tandem with their parents’ educative goals. Williams College loomed especially large in parental hopes and student aspirations. Nestled deep in the hills of Massachusetts—Samuel Chapman Armstrong called them “nature’s warts” compared to the mauna (mountains) of the islands—Williams College began educating young men in 1793.57 Missionary parents were attracted to the college by several important events that had occurred at the institution. In 1810 Williams College and Andover Seminary students led the effort to form the ABCFM, the sending organization for all Congregational missionaries to the Hawaiian kingdom. Over a half-dozen missionary fathers had attended Williams. Most importantly, the college had appointed Mark Hopkins its president in 1836, a position he held for thirty-six years. In 1857 the ABCFM also elected Hopkins as its president, extending to missionary parents the hope their children would be encouraged by the college to follow their parents into missionary service.58 Williams College was also where board secretary Rufus Anderson sent his own son.59

Missionary parents and children generally had chosen wisely in Williams College. President Hopkins became an advocate for the missionary children, reserving special rooms for them and even, as in the case of Armstrong, inviting them to live with his family. “He told me that I should have no college bills whatever to pay, being a descendant of the Hawaiian mission,” Armstrong wrote home.60 The college’s moral and religious culture was also generally supportive of parental wishes. “The religious influences here are very good,” James Alexander wrote his mother. The college held prayer meetings five days each week and fined students for their absence. Students were required to attend two services each Sunday.61

Missionary parents could not control everything, however, and their sons assimilated a different theology than they had received as students. Hopkins was a new breed of theologian and critical of Rufus Anderson’s singular focus on teaching indigenous cultures to read the Bible. “We regard destiny as turning upon character,” Hopkins stated. “All desirable results of political economy and social order, and a high, pure, and permanent civilization, will follow.”62 As historian Paul Harris argues, this focus on character “represented a subtle departure from evangelical rhetoric” that emphasized spiritual conversion and discipline. Hopkins, Harris notes, considered colleges “character-building institutions vital to the creation of an educated elite to guide the process of social change.”63 Hopkins’s message was particularly well received by missionary youth whose segregated childhoods had already trained them to expect political and social leadership positions. When founding Hampton Institute, Samuel Chapman Armstrong declared, “Whatever good teaching I may have done has been Mark Hopkins teaching through me.”64

For missionary daughters, the Mecca of female institutions was Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, Massachusetts. Established in 1837 by Mary Lyon, the college prepared women to be “educators,” as opposed to “mere teachers,” in the words of Lyon.65 Lyon advocated training young women for usefulness around the world, as well as cultivating the “missionary spirit.”66 She was a personal friend of Rufus Anderson, who sent his daughter to the seminary during the 1840s, and the two cooperated to recruit Americans for missionary work.67 The ABCFM was, to Lyon, “the glory of our country—the corner stone of all our voluntary benevolent associations.”68 Several missionary mothers in the Hawaiian Islands had attended the seminary, and some of the earliest missionary daughters sent to the United States attended Mount Holyoke. In 1853 five missionary daughters attended the seminary together.69

Missionary parents were pleased that Lyon ran a tight ship. Lyon required all students to board at the institution and participate in its domestic upkeep. “All the teachers and pupils, without exception, will constitute one family,” she stated. To Lyon the enemies of American civilization were “infidelity and Romanism,” and the school required public worship and Bible study, private devotions, prayer meetings, and Sabbath keeping.70 Mount Holyoke girls also exercised daily. “How I hate winter,” Martha Chamberlain complained after a two-mile walk. “Sometimes it seems as though I could not possibly spend another winter in the United States.”71

Mount Holyoke faculty and students extolled, prayed for, and funded missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands. Teachers solicited missionary donations from all pupils and kept track of individual contributions to both home and foreign missions in a written notebook. In 1853, for example, the school donated over $900 to missions.72 The pressure to conform must have been great. As one student noted, New England had its Blue Laws, but Mount Holyoke had “Bluer Laws.”73

Lyon treated the missionary daughters from the islands well. The students had their own room and did not have to sleep in public rooms, where many students lived due to overcrowding. At least two missionary daughters were invited to stay and teach at the school after their graduation. But just like missionary sons at Williams, missionary daughters heard new messages at Mount Holyoke. Like other rising female institutions of the mid-nineteenth century, Mount Holyoke was changing the nature of a “woman’s profession.” As Anne Scott writes, “despite their emphasis upon the importance of woman’s sphere, [these colleges] were important agents in that development of a new self-perception and spread of feminist values.”74 Missionary daughters from the Hawaiian Islands became missionaries, teachers, and wives, just as their parents hoped they would, but unlike their mothers, Hawaiian missionary daughters could—and did—return to the islands as single professional women and married their partners for love, not expediency. Like their male counterparts at Williams, Mount Holyoke graduates returned to the Hawaiian Islands ready to take leadership roles within them.75

Marks of Mammon

Despite the support children received from college administrators, missionary children from the Hawaiian Islands did not wish to stay in the United States after graduation. Ann Eliza Clark did not wait for graduation, leaving Mount Holyoke early to return home to the islands. Like many foreign-exchange students, missionary children had every intention of returning home, yet their desire to return to the islands was based upon something more than homesickness, pointing again to the complexities of assimilation.76

At Mount Holyoke Mary Lyon feared that the “temptations” to return to the islands to live like aristocracy would cause the young ladies from the Hawaiian Islands to lose their missionary spirit.77 Part of Lyon’s concern may have stemmed from what she saw the girls experience in the United States. Martha Chamberlain, for example, kept a list of those students, “the aristocracy,” she called them, who invited each other to parties off campus. Martha referred to herself and her sister as the “common people.”78 Similarly, while missionary sons excelled academically at Williams, they also felt they had something to prove. Sanford Dole remarked in 1867 that the Hawaiian delegation at Williams was down to only one “solitary representative from the Islands, to stand up for the reputation of Hawaii during the coming year.”79

22. Maria (1832–1909) and Martha (1833–1913) Chamberlain. The sisters together attended Mount Holyoke Seminary and returned to the Hawaiian Islands in 1853. Mission Houses Museum Library.

Nineteenth-century missionary children from the Hawaiian Islands demonstrated the insecurities and rootlessness noted in other groups of “third-culture” children.80 They respected the United States as an institution: “The free and just government of the United States is preferable to any other,” wrote one student in the Punahou Gazette.81 Missionary children in the islands celebrated George Washington’s birthday and the Fourth of July. Yet once arriving in the United States, missionary children found themselves unimpressed by American society, writing home about the intemperance, profanity, novel reading, and Sabbath breaking around them. In 1844 former missionary Gerrit Judd accused his missionary colleagues of trying to “make” their children Americans instead of allowing them to embrace the Hawaiian kingdom as home.82 In these efforts missionary parents decidedly failed. Their children repetitively complained about cheaters at school, denominationalism in the churches, Democrats who supported slavery, and Unitarians who preached pluralism.83

Missionary children detested the number of people living in American cities. In Manhattan, “carts, carriages, horses, men, newsboys, bootblacks, beggars, porters . . . all appeared to see who could make the most noise,” William Andrews (1842–1919) described. Andrews called the furrowed brows of New York shipping merchants the “mark of Mammon” and disdained the New Yorkers who traveled to New Jersey every Sunday to frequent liquor stores closed by law across the river. “This leaves us a quiet city on Sundays—something new for New York.”84 In many places, missionary children noted, “religion is almost a dead letter.”85

Students from the Hawaiian Islands also attacked the American psyche. “It is nothing but hurry, hurry, hurry, hurry, one thing after another all the time. No idle moments here,” Martha Chamberlain wrote her mother.86 “An American tries to be in two places at once,” Samuel Armstrong observed.87 “The imaginary wants of many people in America are quite too numerous,” Oliver Emerson remarked.88 James Chamberlain criticized Americans for “running after each new thing.”89 Immigrants from the Hawaiian Islands conversely sensed a closed-mindedness in Americans. William Alexander disparaged “the shallowness, the slavery to prejudice . . . and narrow views that prevail so much among what are called educated men in this country.”90

The missionary children’s attitudes about the United States often stemmed from their feeling that they were outsiders. By speaking only the Hawaiian language to each other when around Americans who did not understand it, and holding annual conventions across Massachusetts and New York, white immigrants from the Hawaiian Islands demonstrated their frustration with their foreign status. “I feel truly thankful that we have been brought up amidst the good influences of a heathen country and not in the U.S.A,” James Alexander wrote home in the 1850s.91 His sister Mary Jane Alexander (1840–1915) concurred, “I am thankful my home is not here, and that I can hope to return to my native land.”92

Not all were able to return to the Hawaiian kingdom. Passage to the islands could cost as much as $500. James Alexander borrowed money from the ABCFM in order to return home to his parents. The board expected him to pay it back.93 Evarts Chamberlain borrowed funds at 6 percent interest from a Boston merchant.94 Henry Lyman left the Hawaiian Islands intending to return as an attorney “to grow rich in the courts of the kingdom.” He never did.95 Missionary sons and daughters who settled in the United States lamented the loss of their native land throughout the remainder of their lives.96

War Comes a Calling

Despite their overwhelming desire to return to the islands, missionary children embraced the Union with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. In fact, for missionary children entering the United States during the 1850s and 1860s, the war was the single most important influence in their American acculturation. As staunch opponents of slavery, missionary parents admired the Republican Party and cheered the election of Abraham Lincoln. Missionary sons eagerly joined the Union Army, believing it a way to combine the values they had learned at home with the patriotism around them.

Some missionary sons may have also used the war as a way to demonstrate their independence. Historian Philip Greven argues that many nineteenth-century evangelicals suppressed deep animosity toward parents and authority because they had not been taught how to disagree. “Consequently by becoming soldiers for Christ,” Greven proposes, “evangelicals often demonstrated a remarkable capacity for vigorous and sustained aggressiveness.” Missionary children living in the United States during the war showed a decided determination to join the Union cause, despite their parents’ pleas they remain uninvolved. “We send Nathaniel from us hardly expecting to see his face again,” missionary John Emerson worried, “as he goes to our native land at a time when the spirit of war is raging.”97

At least a dozen missionary sons from the islands enlisted in the Union Army. Brothers William, Theodore, and Joseph Forbes enlisted. “I feel as though I had buried them all in one grave,” their mother wrote.98 William Forbes traveled with General Sherman through Georgia. Theodore Forbes spent six months in a hospital and was permanently disabled. A rebel sharpshooter killed Joseph Forbes.99

For his part, Nathaniel Emerson fought at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg before catching fever during the Battles of the Wilderness. Emerson’s Punahou friends were impressed, noting to each other that he was “spilling his blood in the glorious cause of universal liberty.”100 Samuel Ruggles, appointed assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army, died in the war. Henry Lyman, also an army surgeon, served casualties after the battle of Shiloh. Titus Coan practiced medicine in the U.S. Navy. Samuel Conde twice escaped being held prisoner by the Confederate Army. James and Evarts Chamberlain served the U.S. Army on Mississippi River steamboats. Siblings Porter and Mary Green and Jennie Armstrong taught freed slaves. Jennie’s brother Samuel Armstrong became a brigadier general, his service allowing him to become a naturalized U.S. citizen. Armstrong cited the American Civil War as among the greatest influences upon his life.101

Missionary children were caught up in the feeling of being part of something greater than themselves. Mary Jane Alexander described being in New York City after the fall of Sumter: “the scene was grand; the change of men from dollar and cent calculators to enthusiastic patriots was sublime.”102 Samuel Alexander declared, “I am not certain but [war] is my calling.”103 Mary Andrews, lacking a flag, “hung out of a window a red dress, a white one, and a blue one, determined not to be behind in [her] exhibition of patriotism.”104 Supporting the Union was one way missionary children could agree with Yankees and demonstrate they were not like idle Southerners. After all, in his wildly successful How to Be a Man, popular nineteenth-century children’s author Harvey Newcomb compared children from the tropical climate of the Hawaiian Islands to Southern slaveholders, that “vicious” class of idlers.105

Homefront Battlefields

Like other Western-educated foreigners who returned to their homelands to appropriate what they had learned, the Hawaiian-born U.S. college students of the 1860s became the middle-aged revolutionaries of the 1890s. But supporting the eventual U.S. absorption of the islands and working toward it initially were considered two different things to missionary descendants returning to the Hawaiian kingdom. Missionary children remained ambivalent about U.S. expansion. English writer Isabella Bird was confused by the “incongruous elements” of Hawaiian culture in which “Republicans by birth and nature” uttered the words “Your Majesty” so easily. Bird noted that although missionary descendants expected U.S. annexation, it was “impious and impolitic to hasten it.”106

The Union’s prosecution of the Civil War gave missionary children from the islands a moral confidence in the United States. Bird, traveling the Hawaiian Islands in 1873, called the small nation thoroughly “Americanized.”107 Missionary children did not agree. Believing themselves Hawaiian, not American, they did not see the cultural and racial superiority by which they lived their Hawaiian lives. Missionary children believed their moral education and appreciation for republican government, which they had received at Punahou and in the United States, elevated their position in the islands. While in the United States, missionary children adopted racial understandings of national behavior. White missionary children distanced themselves from the Hawaiian people and argued for their own ability to rule the island nation based upon race. By lecturing each other not to abuse their superiority, they reaffirmed those beliefs. As missionary son Henry Whitney—who returned to the islands and became editor of the Pacific Commercial Advertiser—stated, native Hawaiians were “inferior in every respect to their European and American brethren.”108

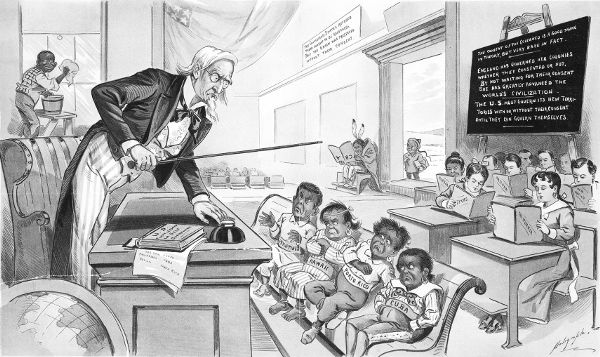

23. Louis Dalrymple for Puck magazine (January 25, 1899): “School Begins.” Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawai‘i, and the Philippines receive the benefits of an American education. The blackboard reads: “England has governed her colonies whether they consented or not. By not waiting for their consent she has greatly advanced the world’s civilization. The U.S. must govern its new territories with or without their consent until they can govern themselves.” Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-28668.

“Who are the real people of Hawaii?” Sereno Bishop asked in 1896. “Are they the decadent and dwindling race of aboriginal Hawaiians, who still linger in the land?” Sent to the United States at age twelve, Bishop returned to the islands thirteen years later as an ABCFM missionary. “Or are they not rather the fresh, active, brainy white race?” Bishop used his bully pulpit as editor of the Hawaiian evangelical publication the Friend from 1887 to 1902 to argue annexation was necessary for maintaining white political and economic control over the Hawaiian Islands. “Hawaii is to find its unavoidable and certain destiny in the bosom of the American Union,” Bishop predicted.109 By the 1890s Bishop had also convinced Sanford Ballard Dole. Perhaps no Hawaiian-born missionary son better illustrates the complexities of Americanization and what historian Donna Gabaccia calls “immigrant foreign relations” than Dole.110

Sanford Ballard Dole (1844–1926)

Sanford Ballard Dole attended college and law school in the United States with a clear desire to return to the Hawaiian Islands. Despite the U.S. citizenship of his parents and his status as a white native in the islands, Dole never viewed himself as an American, and his life exemplifies a reluctant acceptance of U.S. international power. Born at Punahou School to Emily and Daniel Dole, Sanford Dole’s earliest years were marked by tragedy and transiency. Just days after her son’s birth, Emily Dole died, and Dole was removed from his father and two-year-old brother George. Shuffled between missionary families, Dole returned to his father and stepmother, Charlotte Knapp Dole, two years later. The one constant in Dole’s early life was the presence of a Hawaiian wet nurse. Dole later remarked, “I am of American blood but Hawaiian milk.111

As a student at Punahou, Dole imbibed the same messages fellow missionary children did. Principal Daniel Dole’s belief that the racial character of the islands was inevitably changing and his desire to teach the missionary children “to become part of a new nation” were not lost on his son Sanford.112 The younger Dole retained a lifelong respect for the school’s mission, later becoming its longest-serving trustee and helping to administer the institution for forty-eight years.113

When Sanford Dole arrived at Williams College in 1866, he entered the institution as a senior. Dole was anxious to return home to the Hawaiian Islands, and Williams College president Mark Hopkins encouraged his leanings. “I have decided to study law, with reference to practicing at Honolulu,” Dole wrote to his parents in 1866. “I look upon it as a possible stepping stone to influence and power in the Government, where they need good men.”114 The decision deeply disappointed his parents, who wished Dole to return as a pastor to the natives. “It is too late to change my plans,” he answered them.115

Like Hopkins, Dole was critical of the American missionary experiment in Hawai‘i. “I think that the reason that the old missionaries have so little influence . . . is because they thunder at [the people] too much from the pulpit, and shun them too much in the affairs of daily life,” Dole wrote his stepmother from the United States in 1868. “A good man could, I think, do more for the nation for morality and justice than preaching to the natives,” Dole noted.116

Dole was dissatisfied at Williams and in the United States, calling himself a “Hawaiian exile.”117 Yet when he returned to the islands, he often condemned the white residents, who had visibly increased in number during his absence, for what he believed to be their negative influence upon the Hawaiian kingdom of his youth. From his first years back in the islands, Dole was concerned with the issue of Hawaiian labor. In Dole’s condemnation of the Masters and Servants Act, Dole compared Chinese contract labor to U.S. slavery. The 1850 act allowed Hawaiian planters to offer foreign labor contracts of up to five years. The contracts were binding even if signed outside the islands.118 “The words so often heard during the last few years, ‘I did not like my Chinaman, so I sold him last week,’ or ‘I have bought a new cook,’ smack too disagreeably of the Southern institution for us to pass lightly by,” Dole wrote in 1869.119 Dole’s first issue of the Punch Bowl, an anonymous newspaper which ran from July 1869 through October 1870, dealt with the labor question, and his biographer Helen Allen concludes that Dole was “more interested in the workers than the plantation owners.”120

Dole instead advocated selling individual plots of up to thirty acres of government lands to immigrant settlers and paying for the passages of up to eight hundred families annually. “The children of the immigrants, educated in our schools, would grow up, to all intents and purposes, nationalized Hawaiians,” he explained. Dole’s view of Hawaiian citizenship was racially expansive but politically restrictive, based upon a degree of commitment and responsibility. In truth it was a blend of his own attachment to the islands as a Hawaiian-born white, but also American influences, including the 1862 Homestead Act.121

In 1884 Dole became a member of the Hawaiian legislature and worked to pass the first Hawaiian Homestead Act, designed “to provide many persons of small means who were without permanent homes and are desirous of obtaining homesteads.”122 The Hawaiian government made available for purchase public lands of between two and twenty acres. Individuals, irrespective of race, who paid a $10 filing fee and quarterly interest on the appraised value of the land were freed from paying taxes on the land for five years. Homesteaders could not transfer their land to a third party and were required to pay or mortgage the price of the land at the end of five years. In 1887 King Kalākaua rewarded Dole with an appointment to the Hawaiian Supreme Court, where he served until the 1893 revolution.123

Dole held the Hawaiian monarchy in high regard. The fact that the Hawaiian monarchy had willingly created a constitution and legislature limiting its power, and continued to live under it, deeply influenced Dole’s thinking. Kamehameha III’s 1839 Bill of Rights was “not wrung from an unwilling Sovereign by force of arms, but the free surrender of despotic power by a wise and generous ruler,” Dole wrote. The Māhele, Dole commended, resulted from “the earnestness and patriotism of the King and chiefs, who cheerfully made great sacrifices of authority.”124 The 1853 Hawaiian constitution forbade slavery, Dole noted, “ten years before this enlightened policy was followed by the United States.”125

Despite his support for the monarchy, Dole had concerns about its retrenchment. In 1864 King Lot Kamehameha refused to take the oath pledging loyalty to the constitution and unilaterally called a constitutional convention. The changes he ushered through the convention continued to allow the Hawaiian monarch to appoint the house of nobles but reduced the legislature to one chamber, ostensibly to increase the king’s influence. All cabinet appointments were made by the king and served at his pleasure. There was no provision for overriding the king’s veto. “The constitution was defective,” Dole wrote, “in that it lacked restrictions on royal arbitrary power, if the sovereign was bent on attempting to exercise it.”126 Dole’s commitment to constitutional law now propelled him in a new direction—toward abolishing the monarchy.

Missionary grandson Lorrin A. Thurston stated that Dole “was the revolution.”127 Yet Dole’s leadership in both the 1887 and 1893 revolutions was tentative and ambivalent. Dole advocated a native solution to political unrest, including putting Princess Kaiulani on the Hawaiian throne rather than abolishing the monarchy, but he also continued to support the revolutionaries when they moved against the throne. In a letter to his brother George, Sanford Dole wrote, “Over and over again I pleaded that they consider accepting Kaiulani in a regency. When it proved to be of no avail I felt there was nothing else to do.” Dole viewed his own participation in revolution as necessary to safeguarding the Hawaiian kingdom he loved.128

In 1887 Dole invited the Hawaiian League to meet at his home to plan revolution. The league illegally forced Kalākaua to sign a new constitution limiting the monarch’s power by allowing the election of nobles, separating the legislative houses, and creating a veto override. Dole strongly agreed with these constitutional changes that favored the legislature. When Queen Lili‘uokalani attempted to abrogate this Bayonet Constitution, Dole again assumed leadership in the resistance movement. As he had done before, Dole condemned what he viewed as constitutional proposals that allowed for monarchial abuse of power. Under the queen’s proposed constitution, the Hawaiian monarch would be able to remove cabinet officials without legislative approval, ignore a legislative veto override, appoint nobles, and restore a one-house legislature.129

Dole’s ideas on legislative authority actually ran counter to evolving U.S. constitutional theory. As Fareed Zakaria has pointed out, similar debates were occurring in the United States with the opposite outcome. Post–Civil War presidents flexed their executive muscles by arguing for the unilateral right to remove cabinet members and for an increased use of their veto power. Like the Hawaiian monarchs, U.S. presidents sought greater executive privileges at the expense of legislative power. In the case of the United States, presidents did so in order to move around deeply divided congresses and exert greater national and international influence. Dole did not look to the United States as his guide when attempting to define executive power in the islands, although he utilized the legal training he had received there to assert legislative authority over the monarchy.130

As the revolutionaries seized control of government buildings, Dole forced Lili‘uokalani to abrogate the monarchy, and he became the first and only president of the provisional government and Hawaiian republic. In defending the revolutionaries’ actions, Dole wrote U.S. minister Albert Willis: “It is difficult for a stranger like yourself . . . to obtain a clear insight into the real state of affairs and to understand the social currents, the race feeling and the customs and traditions which all contribute to the political outlook. We, who have grown up here . . . are conscious of the difficulty of maintaining a stable government here. A community which is made up of five races, of which the larger part but dimly appreciate the significance and value of representative institutions, offers political problems which may well tax the wisdom of the most experienced statesman.”131

The new constitution of the Hawaiian Republic, which Dole helped draft, maintained property and literacy requirements for the electors of the upper house but also gave the upper house the right to introduce revenue bills. Dole noted that the plan, which reasserted the mostly white, propertied class, would “raise considerable opposition.”132 Lili‘uokalani had endeared herself to her people by promising to disenfranchise white foreigners and reduce the property requirements for the electorate. Dole knew he was diluting the indigenous Hawaiian vote. Although native voters technically maintained their franchise, they were also required to swear allegiance to the new republic, and many refused. Through language requirements for naturalization, the republican government also restricted the franchise of Japanese and Chinese residents who comprised nearly half of the islands’ residents.133

Dole’s biographer called the new constitutional government an “oligarchy.”134 Yet from a comparative perspective, a far different scenario was occurring in the United States as presidents sought to negate ethnic, political, and racial divides by exerting new executive interpretations of formerly legislative prerogatives.135 Dole chose to divide ethnic political interests by emphasizing legislative power. His ideas were rooted in the political legacy of Kamehameha III, but the new constitution was also a reflection of Dole’s confidence in peers living in the islands—white, propertied missionary descendants who shared Dole’s love for the land but resistance to indigenous autonomy. Dole called them a new breed of “missionaries.”136

Dole never escaped from his missionary parents or Punahou education. Dole’s respect for Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) and the Hawaiian constitution did not override his belief in white superiority and American intellectual and cultural supremacy. Dole had read Columbia University professor John Burgess’s Political Science and Comparative Constitutional Law (1891) in which Burgess argued that the “Teutonic race” had built the most complex states. In writing to Burgess for advice on the new constitution, Dole complained, “There are many natives and Portuguese who have had the vote hitherto, who are comparatively ignorant of the principles of government and whose vote from its numerical strength as well as from the ignorance referred to will be a menace to good government.”137 Dole’s acceptance of American racial ideology, but hesitance toward the expansion of U.S. power in the Pacific, explain why Dole was willing to stare down U.S. authority shortly after the revolution. When President Grover Cleveland ordered U.S. minister to Hawaii Albert Willis to return the throne to Lili‘uokalani in 1893, Dole replied to Willis: “We do not recognize the right of the President of the United States to interfere in our domestic affairs. Such right could be conferred upon him by the act of this government, and by that alone, or it could be acquired by conquest. This I understand to be the American doctrine, conspicuously announced from time to time by the authorities of your Government.”138

While Dole and the Committee of Safety had established the Hawaiian Republic with “the view of eventual annexation to the United States,” Dole believed he and fellow missionary descendants were the proper gatekeepers of Hawaiian sovereignty until that time.139 Like other missionary children, Dole’s desire to sway U.S. foreign policy was always on behalf of the islands, yet unlike other nineteenth-century immigrants to the United States, these white missionary children ultimately demonstrated disproportionate influence over their one-time host country. They convinced the U.S. government to annex their nation by congressional joint resolution in 1898.

Adult Rebellions

It is tempting to view the missionary children’s participation in revolution and support for U.S. annexation as the simple product of racial hatred or economic incentive. Queen Lili‘uokalani certainly did. It was a “project of many years on the part of the missionary element that their children might some day be rulers of these islands,” she argued to the U.S. government after her overthrow.140 Certainly Sanford Dole was familiar with the interests of sugar planters in the islands, having served as president of the Planter’s Labor and Supply Company in 1885. The group of planters had formed after the United States granted trade reciprocity, in order to cooperate on labor issues and share scientific and technological advancements. The group also had strong ties to the Hawaiian League, which forced the Bayonet Constitution upon Kalākaua in 1887 and was led by Sanford Dole.141

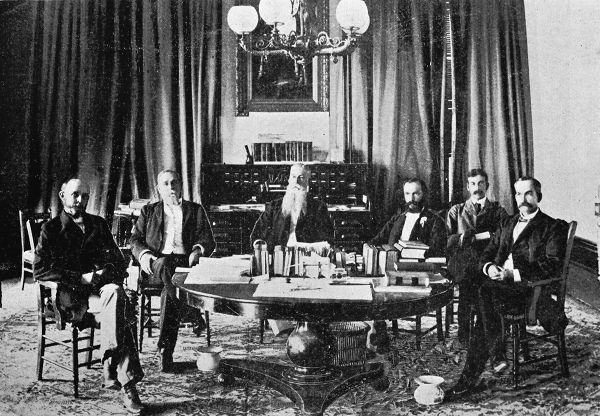

24. Executive Council of the Republic of Hawai‘i. Samuel Mills Damon (far left), Sanford Ballard Dole (middle), and William Owen Smith (far right) were all missionary sons. Mission Houses Museum Library.

Certainly Sereno Bishop’s repeated calls for annexation were steeped in the language of white superiority. But when one pictures Bishop as a child watch his mother starve herself to death, rather than return to the United States to seek medical attention, or imagines Bishop arriving in the United States only to realize the “grossness of speech” there was what his parents had shipped him away from the islands to avoid, one begins to understand the complexities of missionary children’s attitudes toward the Hawaiian kingdom.142 For example, missionary son Henry Baldwin (1842–1911), one of the most successful and powerful sugar planters in the Hawaiian Islands, did not want to remove Lili‘uokalani from her throne and advocated working within Hawaiian constitutional means to address political conflict. Baldwin’s public efforts on her behalf, as well as his peers’ response (he was “howled down” at a public meeting), demonstrate that debate over U.S. annexation began in the Hawaiian Islands among the white missionary descendants.143

It seems ridiculous that a parent like Peter Gulick could force his children to become missionaries while living six months away by mail or sea. It becomes less amusing when one learns that Gulick’s son Charles died of bulimia as a college student in the United States, the illness caused by what biographer Clifford Putney believes was fear of disappointing God and his parents.144

While Henry Obookiah may have begun the trajectory toward U.S. annexation in 1812, the American Civil War propelled it forward by giving moral license to a frustration and aggressiveness that many of the missionary children sensed but few could describe. The war allowed them an outlet for supporting a cause independent of their parents—a cause that gave them prestige among their American peers. The frustration missionary children experienced stemmed from their complicated relationships with their parents.

In 1861 President Abraham Lincoln gave young students from the Hawaiian Islands a reason to identify with the American nation. Republican unity against the expansion of slavery and the Northern commitment to fight against secession provided an environment for the acculturation of Hawaiian immigrants, a process affecting not just white children from the islands. Indigenous Hawaiians served in the Union Army, as well. Yet the war affected each group of Hawaiians in dramatically different ways. Among whites from Hawai‘i the war fostered loyalty to the United States and a rationale for installing republicanism through violent means. For indigenous Hawaiians the war created a false sense of security, as Queen Lili‘uokalani found when she surrendered her island nation to the United States during the 1893 revolution. Hoping for justice, she was met with silence. For nineteenth-century white Americans, ousting a U.S.-educated, white republican government to restore an indigenous monarchy would have been, in fact, truly revolutionary.