Time, happiness, and the curve of the U

Not everyone, of course, will be unhappy at forty-five, or happy after that. In this chapter, I’ll explore the meaning and magnitude of the happiness curve; but the best way to introduce the curve is by emphasizing first of all what it is not. It is not an inevitability; it’s a tendency.

There is a world of difference between the two—a difference which explains why the happiness curve’s real-world effects can be subtle, unpredictable, and strange. The river in the Voyage of Life has regular currents and well-charted turns; yet, paradoxically, no two voyagers experience the same journey.

Psychologists say that the notion of a universal midlife crisis is a myth. “People can certainly be unhappy in their middle adult years, and they can certainly go out and buy sports cars (or fantasize about buying them),” writes Susan Krauss Whitbourne, in Psychology Today. “However, whether they do so because of, or in direct relation to, their age is doubtful. Change is possible at any age, whether in crisis form or not, as we all try to achieve fulfillment.” Her statement is certainly right. For everyone I encountered who had experienced the U-shaped happiness curve, I encountered someone else whose life satisfaction had taken a very different shape.

As I have mentioned, I gave almost three hundred people of middle age and above a questionnaire asking them to both rate and describe their satisfaction in each decade of life so far.* Aside from the U, the life-satisfaction trajectory I encountered most commonly—and very commonly, at that—was a rising line. People who experience this upward-slope pattern typically have unhappy or turbulent early adulthoods, a start in life they’re happy to put behind them.

Take Joe, for example. When we spoke, he was fifty-seven, and his life-satisfaction ratings had risen with each decade of life: four in his twenties, five in his thirties, six in his forties, and seven in his fifties. He was born in the South and had never left. Not college-educated, he went to work after high school, first as a truck driver, then a welder. He made mistakes, including a bad marriage that began when he was twenty-three and ended before he turned thirty. He drank too much and did drugs. His divorce forced him to start over and landed him with a pile of unpaid bills, and he had to move back in with his parents, a setback he found humiliating. At thirty, though, he met the right person, and they married and had a son. Meanwhile, he took a job running cranes at a steel mill, where after more than twenty years he still works. He likes what he does and knows that stable, decently paid blue-collar employment is becoming rare. The real anchor of his values, though, is his family: “A lot of kids in my day wanted to be a fireman or policeman or astronaut. I just wanted to be a dad.”

In middle age, Joe realized he needed to walk closer to the Lord. He had always been a churchgoer, he said, “but I wasn’t living the life or being the example that I should.” Fatherhood convinced him he needed to do better. At fifty-seven, he felt his relationship with God was good and improving. “My wife and I were out the other day and a young man asked us what’s the secret of a good marriage. We both said, ‘God.’ I’m a firm believer that if you don’t have God in your life, it’s tough.” When I asked how the future looks, he said he expects to hit an eight in his sixties. “I’ll have my wife and hopefully some grandchildren by then. Hopefully a place on the beach or on the lake. Life just seems to get better as you get older. I learn something each day, and it adds up.”

Another common life-satisfaction pattern is the V-shaped curve. It is rarer than either the U or the upward-sloping line—mercifully so, because it’s the pattern characterized by a disruptive breakdown or an acute crisis rather than a chronic malaise. An example is someone I know well, Tony. When we met in the early 1990s, he was twenty-two, a sweet-natured, baby-faced gay man who had only recently moved from a city in the South to Washington, D.C. He had an easygoing, positive personality, and bushels of talent, so he was never someone I worried about. And then, when he was forty-six, he disappeared. I asked around, but all that anyone had heard was a rumor that he had quit his job and moved to Florida. For a time, I wondered if I would ever hear from him again. When he resurfaced, it was with a story of midlife collapse.

Tony had risen fast. From waiting tables and sharing an apartment, he became an arts reporter in his twenties. By thirty, he was movie editor for a major media outlet, where he managed writers more experienced than he. Then he followed a boyfriend to Asia, wrote freelance, began a successful blog, won an award. “My thirties were fucking great,” he told me, when I finally reconnected with him. “I’m feeling really successful. I’m starting to hit my stride.” But he was fighting impostor complex, an incessant din of inner critics telling him his success was unearned and precarious. A move to the suburbs felt deadening and his sex life at home went flat. Tony couldn’t stay faithful; his partner broke up with him. Meanwhile, he began to feel his work lacked meaning. “I was having something of an existential crisis, asking myself if even this nice job I had, this job that seems to impress other people, was producing anything of value. I escaped into booze and sex.”

That turned out to be a catastrophic mistake. As his drinking became heavier, he had trouble at work. He left with a nice severance package, which only made matters worse. “That made it possible for me to sit at home quietly and drink. I did that for almost exactly six months and made myself actually ill. I got to the point where I had to get out of town. Even through the bourbon haze it was clear I would probably not make it through the winter if I didn’t do something.” Fortunately, he managed to pull himself together enough to call a relative in Florida, get on a plane, and checked into a hospital for medical detox. Later came weeks of intensive rehabilitation.

When I finally heard his story, after having been out of contact with him for a year, it came as a shock. Nervously, I asked my old friend if he thought he was out of the woods. He replied that his finances were precarious but he was sober. He was unsure what lay ahead but was willing to venture optimism: “I think I can keep the ship more or less aright.”

When Tony’s slide began, it looked very much like the onset of a typical midlife malaise, the kind that causes chronic dissatisfaction, but not an acute crisis. In fact, if Tony had not mishandled his restlessness and discontent, he might well have plodded through more or less uneventfully, as most people do. When a U curve goes bad, it can turn into a V, causing pain to ourselves and the people around us, and sometimes leading to mistakes from which our life satisfaction never fully recovers.

An example is Alan. Unlike Tony, he was a stranger when I interviewed him. A tall, slender, dignified man of sixty-five, he was the first in his South Carolina family to go to college, where he earned an accounting degree. After serving in the Vietnam, he worked in a series of white-collar government jobs, building professional momentum which lasted into his thirties. Alan was someone who enjoyed being busy and having responsibility, and he ascended into management. Around the time he turned forty, however, he fell in with shady people. One of them asked him to intermediate in a drug deal. Alan agreed and took a cut. A few months later, the seller returned for a second deal. Alan realized he was in over his head. He considered turning informant, even contacted police, but got cold feet when he reflected that he could wind up “sleeping with the fishes.” Instead, he took a rap for attempted distribution of cocaine, which landed him in prison for a year.

Characteristically, he made the best of his confinement, working in the prison’s law library and as a clerk on an antidrug program. On release, he managed to find a data-entry job, worked at it for several years, but then was laid off. “So I’m back out of work,” he recalled of that time. “But now I have a record. It’s hard to get to the level where I was, because at some point you’re going to have to bring this up.”

After that, Alan found a position working as a corporate mail clerk. It was a long way from management, but it proved stable. Still, when we spoke he was sixty-five and could not afford to retire. He worked alongside millennials who, he said, couldn’t care less about doing the job right. He felt angry at himself for losing his way in his forties. He especially felt regret. He had never managed to rejoin the white-collar, upwardly mobile society of his youth; and he never would. “There’s always something to remind you. You’re riding high, and—Wham! Boom! After that, you feel it’s hard to be around those people you knew before. It’s hard to go back.”

I interviewed dozens of people for this book, trying to understand in an intimate, textured way how they experience life satisfaction over time. I have learned what we all already know. There is no single, standard trajectory for human happiness. The only rule is differentness. My own path (so far) has followed a U that might have been lifted right out of one of Carol Graham’s graphs, but Tony’s and Alan’s V and Joe’s upward-sloping line are also commonplace.

Yet the U-shaped happiness curve, while not necessarily dispositive for any of us, may nonetheless influence all of us—even if what we experience in life is more like a rising line or a V. How can that be? The answer requires looking more closely at the shape of the river.

* * *

As I was working on this chapter, Danny Blanchflower sent me an email. “Take a look here,” said the subject line, above a message that said: “This is the latest stuff from the U.K.” Britain maintains one of the world’s most thoroughgoing efforts to measure subjective wellbeing, of which its Office for National Statistics conducts annual surveys. The latest statistics, for 2014 to 2015, were in. Over three hundred thousand people of different ages had been asked, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?” Here is how the results look, by age group, when you graph the percentage of people saying their life satisfaction was high or very high (as opposed to low or medium).

As is immediately apparent, satisfaction declines from youth through middle age, bottoms out in the early fifties, and then rises to a peak at age seventy before roughly leveling off (with a mild decline) until advanced old age (eighty and beyond). People were also asked how happy and anxious they felt yesterday, measures of affect rather than satisfaction with life, and those indicators followed the same general pattern, with anxiety and unhappiness peaking in the early fifties and then falling through the sixties. You don’t need a PhD to interpret the graph; in fact, this is the kind of data which leads Blanchflower to roll his eyes and say, “How hard is that to see?” when psychologists say they can’t find a U.

The pattern is telling us something interesting about the happiness of people of different ages. In Britain, in 2014, the average middle-aged person was less happy about his or her life than was the average young person or older person. But what is it telling us about age itself? That is a different question.

Over lunch one day, Andrew Oswald illustrated the distinction by using one of his obsessions: fruits and vegetables. (As it happened, we were sharing a vegetable plate.) A few years ago, rummaging around in large data sets, he had discovered, in Britain, a “remarkable relationship” between eating fruits and vegetables and being satisfied with life. That became grist for a paper he coauthored with Blanchflower and Sarah Stewart-Brown. You might have thought there would be a lot of research on connections between diet and happiness, given how much everybody cares about both subjects, but in fact their study, Oswald said, is among only a few to have looked for a relationship. What they found was this: “Happiness and mental health rise in an approximately dose-response way with the number of daily portions of fruit and vegetables”—all the way up to seven daily portions, which is about as much fruit and vegetable matter as anyone can ingest.

But wait: People who eat a lot of vegetables are likely to be different in many ways from people who do not. They may have higher incomes (poor people have less access to fresh fruit and vegetables) and healthier lifestyles (smoking less, exercising more); they may be younger and better educated; they may just be happier to start out with. There are all kinds of reasons why what looks like a connection between diet and happiness might be the result of some third factor influencing both. What you really want to know, then, is not whether people who eat a lot of vegetables are happier on average, but whether eating vegetables is in and of itself associated with happiness and mental health. The more interesting finding of the fruit and vegetable study is that the answer is yes.

Oswald and his coauthors adjusted their analysis for all kinds of factors which might influence happiness, including, for instance, age, income, marriage, employment, sex, race, exercise, smoking, religion, body mass, and even consumption of other foods like fish, meat, and alcohol. In effect, they used statistical techniques to compare like with like across a variety of dimensions, which large data sets allow them to do. If adjusting for income or education or fish consumption had made the effect of eating fruits and vegetables go away, then that would suggest that income or education or fish consumption is what really matters. In fact, however, “the pattern [they write] is robust to adjustment for a large number of other demographic, social, and economic variables.” They find what they call a fruit-and-vegetable gradient, and its effect on happiness and mental health appears quite significant.

Their result does not prove that eating more fruits and vegetables will, by itself, make you happier. I wouldn’t be surprised if that were the case, but in the social sciences establishing causality is difficult. What the fruit-and-veggie gradient does reveal is a genuine association: some sort of independent relationship between the two variables, and thus something which cries out to be explained.

Age, of course, is different from diet inasmuch as we can’t control it. If someone develops a way to escape midlife blahs by becoming younger, no doubt many people will avail themselves of it, but that day seems far off. Still, the question which most intrigued Oswald and Blanchflower and me, once I got my head around it, is whether age itself has an apparent effect on how happy we are.

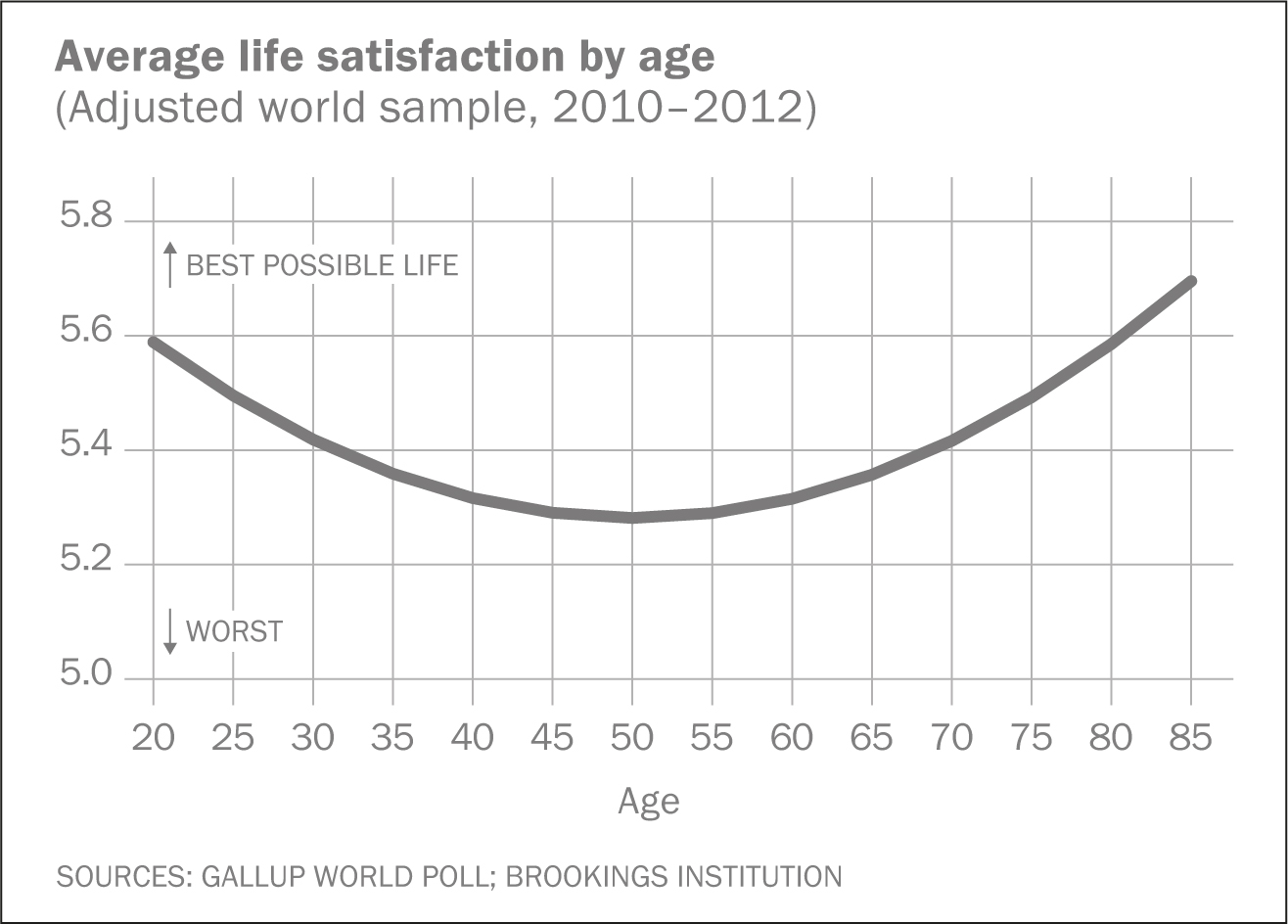

The answer, again, is yes. In fact, the happiness curve shows up more clearly and consistently after filtering out people’s life circumstances than before. Here is an example, from an analysis by Carol Graham and her colleague Milena Nikolova of the biggest data set out there, the Gallup World Poll, whose survey set of 160 or more countries covers about 99 percent of the world’s population. If you just look at people’s assessments of their own lives compared to the best possible life they can imagine for themselves (one of the most widely used gauges of overall satisfaction with life), the results turn out like this:

If there is a visible trend, it is that people get happier over time, with an upward bump around retirement age. But once Graham and Nikolova adjust for income, gender, education, employment, marriage, health, and so on—in other words, filtering out other factors influencing life satisfaction—here is how the relationship between age and life satisfaction looks:

There’s the U. Once Graham and Nikolova factor out the other things that are going on, your age, in and of itself, has a clear relationship with how happy you are.

The smoothness of the curve is something of a tip-off. Real-world responses from actual people are jiggly. The U curve, by contrast, is a statistical projection, or prediction, of how satisfied people would be if they were the same in all measurable respects except for age—not, obviously, a real-world condition. When I first encountered this finding, one reaction I had was: so what? We are each a huge bundle of variables, and what we care about is how they all add up—how happy we actually feel—and not how happy we might feel if only one thing in our lives were important. If I want to know, at age twenty, how happy or unhappy I may be at age forty, I’ll need to know whether I’m in a good marriage, whether I have enough food to eat, how my health is, and all the rest. Knowing the independent effect of age on happiness tells us no more about our actual lives than knowing the independent effect of pitching on baseball tells us about who actually wins the game.

The answer lies in understanding what the happiness curve is really saying, which is this: it is perfectly possible to be very satisfied with your life in middle age, but it is harder.

Returning to Thomas Cole’s metaphor of the river, I might say: the happiness curve is like an undertow that pulls against you in middle age. That doesn’t mean you can’t row against it. Or perhaps your load has become lighter, or your rowing skill has improved, or your muscles are stronger, or you have managed to improve your boat. Or perhaps, like Joe, you have come through a worse stretch upstream, when you were younger, so the middle portion of the river seems comparatively tame. If one or more of those things pertains, you may not even notice the more challenging current in middle age. You may think: why would anyone believe this portion of the river is difficult?

Or you may not.

* * *

I was someone who, after going to war with myself over my sexuality in my teens and early twenties, had had a blessed life. I enjoyed good health, did well in my career, had lots of friends. I felt excited and energized in my twenties and early thirties as I came into my own as a journalist and came out of the closet as a gay man. I certainly pulled hard on my oars. I pushed myself and took some serious risks, such as when I quit a good job to attempt a wildly ambitious book, which failed twice before it finally got published. But I was someone who had never experienced an unfavorable current. Events and circumstances had flowed in my favor. In my late thirties, therefore, when the U sloped down and the background current changed, I felt the change keenly. Rowing against the undercurrent was noticeably harder; the river ahead seemed longer; my destination, farther away. The circumstances of my own life had sensitized me to an unfavorable shift in the undertow.

I think this kind of sensitization may be common for people who reach middle age without having experienced major difficulties in earlier adulthood. Joe rated his happiness in his forties at six, which is relatively low. But he experienced his forties as a relief after his unhappy, unsettled twenties and his better but still difficult thirties. On the other hand, Tony’s trajectory is more like mine. He made a fast start and went from strength to strength as a young man, but was then all the more sensitive to the ennui which caught up with him in his late thirties. I doubt the happiness curve, by itself, caused his collapse in his mid-forties; that had more to do with bad decisions he made, notably drinking too much, moping too much, and failing to reach out for help before he lost control. I do think, though, that the curve’s downslope contributed to his malaise, which set him up for the trouble he ran into.

Of course, the undertow would not matter if it were faint. Then it would be a statistical curiosity, something real but not usually noticeable, or at least noticeable only in situations like mine, where everything else is going well in life and no unexpected jolts come along. You may have noticed that, in the chart above showing the happiness curve for the entire world, the difference between the most and least happy portions of the curve is not even a full point on a scale of one to ten.

Actually, however, less than one point still turns out to be quite a bit. Most people restrict themselves to a narrow band in the upper-middle portion of the scale. Eighty percent of people rank themselves between seven and nine, and anything below six is rare enough to indicate serious misery. (Tens almost never appear. People like to leave room for improvement.) Because the rest of the world is not generally as happy as the United States, the average global response is in the five-to-six range, a tick or two lower than in America. Either way, a decline of a point or even half a point is significant.

How significant? The same statistical manipulations which allow economists to tease out the effects of particular variables on happiness also allow them to estimate how large those effects are. In their landmark 2008 paper (which I discussed in the previous chapter), Blanchflower and Oswald find that going from age twenty to age forty-five decreases life satisfaction by about a third as much as becoming unemployed—and unemployment is one of the worst things that commonly happen to people. “That is suggestive of a large effect on wellbeing,” they write. In another paper, which looks at more than two dozen European countries, they find that being middle-aged nearly doubles a person’s risk of using antidepressants, after controlling for other variables. Most recently, in their longitudinal study (also discussed in the previous chapter) of how individuals experience the effects of age on happiness over time, Oswald, Nick Powdthavee, and Terence Cheng find that the effect of going from about age twenty to about age forty-five is comparable “to a substantial percentage of the effect on wellbeing of major events such as divorce or unemployment.” That kind of magnitude is no guarantee that you or any particular person will feel the undertow, or will have trouble with it if you do feel it. But it does explain why the undertow, while too weak to heave me into a full-tilt depression, was strong enough to bother me day in and day out for a decade or more.

In a way, I had it easy. Having enjoyed an enviable launch in early adulthood and then been spared major setbacks or trauma, I experienced the U’s downturn as an unwonted, unwarranted sourness. But if you’re already in a depressed or dissatisfied emotional state, or if you’re struggling with difficult conditions, then the negative undertow can amplify your other problems. One of the more painful interviews I did for this book was with a woman named Nancy, a stranger who emailed me thanking me for an article I wrote about the happiness curve. “It made me feel better about the unaccountable—and very deep—funk I find myself in at age forty-two,” she wrote. Later, in an interview, she told me she was someone who had always struggled with depression. It ran in the family. Her great-grandmother had been institutionalized, her grandmother had been hospitalized, her mother, she said, was a “nutty buddy.” Her twenties, like so many people’s, were fun and exciting. She took an office job in an exciting city, then went back to school, and enjoyed a life of carefree discovery. But, she said, “There was always the background of depression.” Antidepressants, which she finally began in her late twenties, were life-changing, but they did not eliminate the depression, only reduced it. In her early thirties, she became a mother, but she experienced parenthood as a source of stress and anxiety. By the time she turned forty, chronic depression had become a fact of life.

“Even with all that, when I turned forty, something got worse,” she told me. “A couple of years ago—I don’t know—I wake up either sad or angry. It’s worse, and it’s not life-related.” I asked if she could think of a reason for her downturn. No, she replied. Nothing had changed or gone wrong in her life. “I still have the same problems. I’m in a job that’s pretty perfect for me, other than low money.” Her kids were older and at an easier age, which should have reduced the emotional pressure. Her marriage was okay. “I think I’m just sadder,” she said—now fighting back tears, a catch in her voice. “If the depression is the same, and if my life is the same, why am I sadder?” As was also true of me, she not only felt bad, she felt bad about feeling bad; but, unlike me, she was depressed to begin with. If other things are more or less equal, entering the trough of the curve can make an already bad situation worse.

Where does that leave us, in terms of thinking about happiness and age? In his book Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment, Martin E. P. Seligman, one of America’s most prominent psychologists, posits a formula for happiness:

H = S + C + V where H is your enduring level of happiness, S is your set range, C is the circumstances of your life, and V represents factors under your voluntary control.

His formula is elegant and seems intuitively right, and it offers some guidance for thinking about how to become happier. We can’t do much about our happiness set point, which is mostly a function of our genes and personality. We can work to change our life’s circumstances and our own behavioral and emotional patterns in ways that help us be happier. All well and good. But the happiness curve suggests that the formula is missing a term and should look like this:

H = S + C + V + T

where T stands for time, or perhaps more specifically, aging. T—whether you are at age twenty-five, forty-five, or sixty-five—matters, but it is not the only thing that matters.

You can see right away that H, happiness, can get complicated. If C and V, your circumstances and voluntary choices, are changing in ways that make you feel dramatically better about life as you move into middle age, then time may not matter to you. For example, Perry, seventy-two and semiretired, was aware of nagging midlife discontent, but it was swamped by improvements in his circumstances. In young adulthood, he was wounded twice in Vietnam, got married to the wrong person and painfully divorced, and then watched his career as a police officer go up in smoke after he cited the commissioner for drunken driving. (“I made the right decision. You took an oath to enforce the oath, and nowhere in that oath did it say, ‘With exceptions.’”) As sharply as circumstances had zigged south for him in his twenties and early thirties, they zigged north in his mid-thirties when he met a “wonderful woman” and began a new career as a safety officer for a shipping company. “Life turned around,” said Perry. The result was that his satisfaction rating jumped from only three in his early thirties to seven in his forties—and then, once time started working in his favor, to eight in his sixties and nine in his seventies. By contrast, in Nancy’s case, her circumstances and voluntary choices remained mostly steady over time, but in her forties the negative pull of T (middle age) compounded the depressive effects of S (her low emotional set point). Result: misery. And what if different elements are moving in different directions? Well, then it all depends. That is why individual cases vary so widely, even though the U-shaped undertow is quite strong.

In my amended version of the equation, two of the four terms (our emotional set point and our age) are beyond our personal control. One term (our voluntary choices about our lives and attitudes) is entirely under our control. The fourth term (our circumstances) is partly under our control and partly not; one of our challenges in life is to control and improve our circumstances. So the message here is not as simple as fatalism (“You can’t do anything about your happiness, it’s wired into your personality”) or stoicism (“Control your emotions and attitudes, because the rest is not really up to you”); nor does it support the idea that we can be as happy as we choose simply by thinking positively. It clearly does not support a crude story about the inevitability of an emotional crisis or meltdown in middle age.

What it does say is something which I believe is important, even fundamental, and insufficiently or incorrectly appreciated by science and society—a point which I’ll spend most of the rest of this book trying to unpack. Time matters. We cannot reverse its flow or alter our age, but we can comprehend time’s effects and adjust to them, both individually and socially, in ways that make us happier. We can become smarter about that central feature of Cole’s Voyage of Life, the hourglass. In the first three paintings, the hourglass remains squarely in the Voyager’s field of view; yet he pays no attention to it. The baby is too young to be aware of time; the youth gazes at the castle in the sky; the middle-aged man looks heavenward. In the final, fourth painting, the hourglass is gone, knocked away by the travails that have battered the boat; the voyage has reached its end and earthly time is no longer important. The Voyager has overlooked what was right in front of his face all along. Perhaps he should have paid more attention to time, and perhaps we should, too.

* * *

The passage of time is inevitable and inexorable; the clock ticks at the same rate for all of us. To understand the happiness curve, however, a distinction is important. Unless we happen to be traveling at nearly the speed of light, time is an absolute concept. Aging is a more subtle, more relative phenomenon. For one thing, people age at visibly different rates. Anyone who has attended a high school or college reunion will have played the mental game of comparing his or her own aging process with others’. Some people look a good ten years older or younger. Some people, at age fifty, are more physically active and fit than in their days of beer and pizza. Others struggle with painful backs and aching knees and have been forced to relinquish their vigorous self-images.

Moreover, how old we think of ourselves as being depends not just on our bodies, but also on how long we expect to live, and how long-lived and vital the people around us are at any given age. A fifty-year-old person in a poor developing country, where health care is rudimentary and nutrition is sketchy and life is physically taxing and the average age is quite young, will seem very old compared to a fifty-year-old person in today’s America, where it’s said, with much justification, that fifty is the new forty. In China, average life expectancy has risen from the low forties in 1960 to the mid-seventies today, an increase of more than thirty years in just two generations: one of the most staggeringly impressive accomplishments in all of human (or probably galactic) history. True, much of that gain has come from reduced infant and child mortality; the average Chinese person in 1960 did not drop dead at age forty-three. Nonetheless, being forty-three years old in China means something very different today than it did in 1960. Aging, unlike chronological time, is a social concept.

When I use the shorthand “time matters” or the letter T in the happiness equation, then, I am really mashing together two different things. Which is it that shapes the U? Aging, a relative concept that changes across eras and cultures? Or time, which is absolute? The answer has to be: both.

The discovery of a relationship between age and happiness among our closest primate relatives implies that time itself—chronological age rather than social age—matters. After all, chimps age physically, but they don’t know how old they are or celebrate birthdays and retirements. Among species, only we humans tally our years since birth and use incendiary devices and unhealthy comestibles to demarcate the increments. Only humans carry in our heads a statistical forecast of how long we expect to live, and use it to count down our remaining years. Only humans are obsessively aware of where we stand in the aging process relative to others around us. That’s why a fifty-year-old feels, and effectively is, so much older in a society where the average life expectancy is only sixty than where it is eighty.

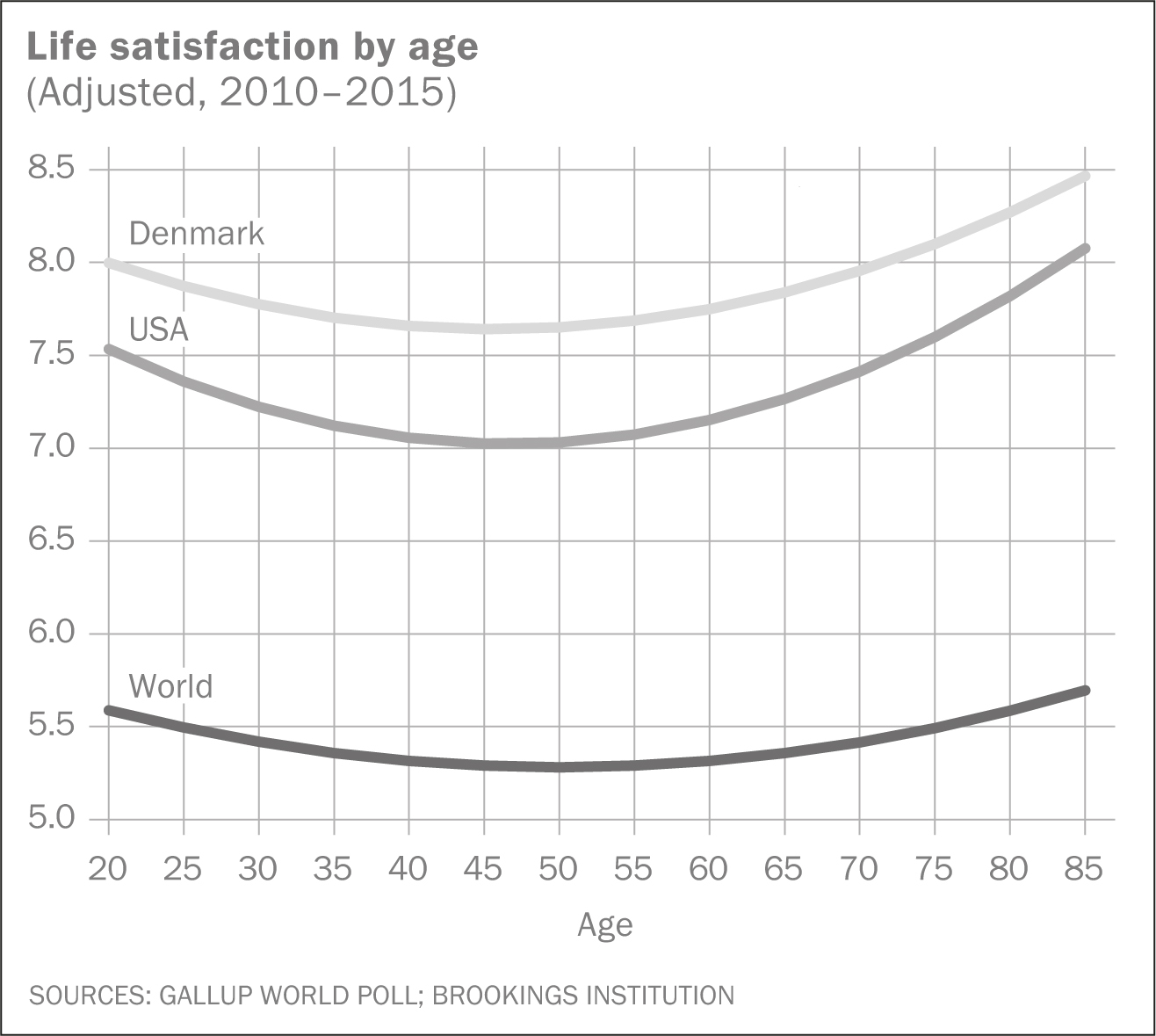

We might expect, then, where you live would inflect the way your age and happiness interact—if you’re human. The chimps and orangutans we met in the last chapter live in three countries and two hemispheres, some in zoos and some in sanctuaries, but their U curves look almost identical. That stands to reason: assuming they are housed and treated more or less comparably, apes have no reason to care which country they are in. It would be surprising if apes in Japan had midlife problems, but apes in Australia did not. The same is not true of humans. Consider this chart, based, again, on Carol Graham’s and Milena Nikolova’s analysis of Gallup World Poll data:

The lowest line is the same worldwide happiness U curve we already saw above. Here, however, it is compared with the age-happiness curves of two countries, namely the United States and Denmark. The general patterns are the same; but at every stage of the curve, Americans are happier than the world as a whole. Age may tend to push their satisfaction downward in midlife, but you would still rather be an average American at age forty-five than an average person in the world at age twenty or seventy. That is not too surprising: America is a stable, wealthy, and generally desirable place to live, which is why so many people want to live there. On the other hand, Denmark, the uppermost line, is happier still. In general, Scandinavia is a very happy place to be. According to the 2016 World Happiness Report, six of the world’s eight happiest countries were in that part of the world (for the record: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden).

It thus turns out that different countries and regions show different age-curve patterns. Countries’ happiness curves bottom out at different average ages, and they can show very different relationships between early and later stages of life. Below, for example, are curves for six places, again from Graham’s and Nikolova’s analysis of Gallup World Poll data.

On each curve, the star indicates the bottom of the curve, where life satisfaction touches its nadir and begins to improve; the dot indicates the average life span in that country or region. In this data set, the United States and the United Kingdom look similar, which is not surprising given their fairly similar cultures and economies. The pattern is the same in Latin American and Caribbean countries, but the overall level of life satisfaction is a notch lower there, perhaps because life is not as easy. In all three places, the turnaround begins in the forties. In China, satisfaction is yet another notch lower, but the upturn later in life is significantly steeper. So China is a relatively unhappy place overall, but it is a place where age brings striking improvement. Germany, on the other hand, is a fairly happy country—sixteenth in the world, according to the 2016 World Happiness Report—but the clock seems to be set somewhat differently there, because happiness does not bottom out until the mid-fifties. On average, Germans live through more years of downswing than upswing. We don’t necessarily need to shed tears for them, because their relatively unfavorable trajectory of happiness is offset by their relatively high level of happiness. Would you rather live in a place with a higher happiness level overall, or a place with more years of increasing happiness? Take your pick. But try not to pick Russia. In the 2016 World Happiness Report it was the world’s fifty-sixth happiest country, and, according to Graham and Nikolova, the curve there does not turn until the average person is dead. That combination of a low level of happiness and a late-turning trajectory of happiness is the perfect mix for misery.

It turns out that these things—happiness level and happiness trajectory—may be connected. Not long ago, when Carol Graham and Julia Ruiz Pozuelo looked at forty-six countries where the Gallup World Poll had surveyed an especially large number of people from 2005 to 2014 (the extra data density produces more statistically reliable results), they found U curves in all but two of them. Going further, they divided the countries into three groups: the most happy set, the least happy set, and a group in the middle. Finally, they looked at the turning point in each group of countries: that is, the age at which people start feeling better, so that the river’s undertow begins to work in their favor instead of against them. They found that the turning point was earliest (age forty-seven) in the happiest countries and latest (age sixty-two) in the least happy ones. In other words, they found a kind of rich-get-richer phenomenon: people in happier countries not only enjoy higher levels of life satisfaction, they also enjoy more years of rising satisfaction, because they get past their midlife dip earlier. The chart below shows how that relationship works.

The same pattern holds for individuals, as well as countries. When Graham and Ruiz Pozuelo looked at the world sample, they found that the happier people are, the earlier their upswing—and, therefore, the more years they spend (other things being equal) enjoying rising satisfaction with their lives. The reason is unknown, but the result, as with so much about happiness, seems neither particularly logical nor particularly fair: the undertow helps soonest those people and countries who need its help the least.

The fact that the relationship between happiness and age is different in different places tells us something important, aside from “Don’t be Russian.” Whatever is going on is partly biological and genetic. The happiness curve would not show up in as many data sets and places as it does, including among apes, if it were not to some extent hardwired. But it is not entirely biological or genetic, because genes don’t vary much between countries, but the pattern does. The happiness curve, then, must be about both time and aging.

So now to the really hard question. Something complex is going on. What is it?