Midlife malaise is often about nothing

At age forty-six, Anthony believes he has peaked. His best personal growth and most exciting days are behind him, or so he thinks.

He is very likely mistaken. I would lay a bet that his best years are ahead of him. He, however, is incapable of seeing that. The happiness curve manufactures discontent from what seems to be thin air, and then, having done so, entices us to give up on doing better just as things are about to turn around. It’s an insidious trick, one whose mischief Anthony is experiencing.

He is a professional whom I had met at a few social functions. When he filled out my life-satisfaction questionnaire, I noticed a downward-sloping curve, declining from his twenties. Nothing unusual there. But when I saw that he used the word peaked to describe his forties, I decided to ask him about it.

His twenties, he told me, were a time of reveling in newfound independence and rapid intellectual growth. He thrived in school, had an exceptional mentor, met and became engaged to his future wife. His thirties brought the typical dose of reality. The job market in his field was tough, he and his wife endured two disruptive moves, and in the midst of one of those moves, both of their fathers died. They were devastated. “For a year after that,” Anthony said, “I went through life like a robot.” A year’s journey through grief brought Anthony back to normality, but it was a new normal. “It had a permanent effect on me. I describe it as the last death of childhood.”

Professionally, things went better. In their mid-thirties, Anthony and his wife both landed dream jobs. But then, in his early forties, he began to feel stagnant. “Reality bites, and it’s pretty clear I had peaked. I had reached my limits, given my IQ and creativity. It was going to be hard to grow more. Let me put it this way: it became clear that I’d done as well externally as I possibly could. So I had a period of depression during that time, maybe a year, a year and a half.”

When I interviewed Anthony, his depressed period was several years behind him. Using my zero-to-ten scale, he rated his life satisfaction an eight, the same as in his thirties. He said he feels fortunate. Still, what I heard, listening to him, was a man adjusting to the idea that the best is behind him. He accepts that he will never be one of the top people in his field, and he is coming to terms with physical decline. He’s on a cholesterol medication. His body doesn’t recover as quickly. The other day, after reading in the paper about someone his age who dropped dead on the StairMaster, he thought: something like that could happen to me.

So he feels he has peaked? “Definitely. I am over the halfway point in terms of age. Physically for sure. And mentally the decline has clearly begun.”

I wondered if he could imagine recapturing the satisfaction and spirit he had enjoyed in his twenties. He replied firmly: “No. That was a very high-growth period. I don’t see that happening. There’s just not enough time.”

Anthony is not an unhappy person, but he finds himself working to accommodate what he assumes are diminishing prospects. He feels that his capacity for both outward achievement and inner satisfaction is waning. It isn’t that things are bad. It’s that things are unlikely to get better. What is missing in his voice is not happiness. It’s optimism.

Here is what I would have been able to explain to Anthony had I spoken to him only a few days later, after I interviewed a young German economist named Hannes Schwandt. Precisely because Anthony’s optimism has ebbed and he feels he has peaked, chances are his pessimism is misplaced and his emotional peak is yet to come. If Schwandt is right, Anthony is a leading candidate for a pleasant surprise.

* * *

It’s hard, actually, to remember journalistic etiquette and call Hannes—I mean, Schwandt—by his last name, because he may be the least formal person I’ve ever interviewed. When I went to meet him at Princeton University one spring day, he bounded downstairs to meet my husband and me in the lobby of the social sciences building and gave us an exuberant welcome before sweeping us off on a campus tour, showing us dinosaurs and chemistry labs while frequently checking his cell phone and talking so fast (in English—not his native tongue) that it was hard to keep up. When we finally alit in the little office he shared with another researcher, students kept coming by to ask where to pick up some T-shirts. Six feet, balding, and trim, with prominent features and beefy hands, Schwandt was in his early thirties and still on the threshold of his first professorial appointment (in Zurich), but he was already enjoying the kind of success which most postdoctoral researchers can only dream of.

Originally from Hamburg, Germany, and schooled in Munich, Schwandt began his graduate work in business economics but quickly got bored. He liked math, but he was more interested in improving society than maximizing profits, and he was frustrated with the tyranny of mathematical modeling. “You spend a lot of time with a lot of fancy models, and you learn very little about anything in real life. We had this class on macroeconomics and unemployment, but I didn’t learn anything about unemployment. I went to the professor and said maybe we should do something on the history of unemployment, and he said he couldn’t even really think without a model.” (Shades, there, of Andrew Oswald, an earlier generation’s rebel against dry mathematical economics.)

He thought about quitting economics altogether, a fate averted when he read a lecture by Richard Layard, a pioneering happiness economist whose approach made sense to Schwandt (and whose work I’ve mentioned in chapter 2). After reading Layard, Schwandt found it bizarre that the economics profession had left to others the study of wellbeing—of what it is that gives people satisfaction. After all, the idea that people always make rational choices, much less choices that reliably improve their wellbeing, is demonstrably wrong. “It could well be that we’re making choices that aren’t optimal for us,” Schwandt said. “And revealed preferences will never tell you this.”

It would be one thing if people were just randomly guessing wrong about their utility, but that, too, is demonstrably untrue. Experiments show a whole assortment of ways in which people’s irrationality is not random but systematically biased. To name just one example (from a famous 1990 experiment by the Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman and colleagues Jack Knetsch and Richard Thaler), people who would be willing to pay, say, only $3 for a mug will then, if given that mug, demand more like $7 to part with it a few minutes later, as if their simply coming into possession of the mug had increased its value. People seem averse to losing what they have, even when they would be better off getting something new. If people exhibit this “endowment bias” consistently, then they will also consistently forgo opportunities to better their lot by trading upward—at least by traditional economists’ definition of upward. Humans, it turns out, are shot through with biases of this kind.

In 2007, Schwandt, still a first-year PhD student, began wondering if people’s expectations were rational about something quite central to their wellbeing: their own satisfaction with life. “I was open to the idea that rational expectations are wrong, and I thought it would be a good test just to check.”

At the suggestion of a mentor, Schwandt dived into data from a German study which had followed the same group of individuals for almost fifteen years, from 1991 to 2004. Not only had the study stayed with its subjects for more than a decade, it included both western and eastern Germany, thereby allowing for comparison across two very different political and cultural contexts. Most unusual of all, the study asked people, not only about their satisfaction with their lives, but also how satisfied they expected to feel five years down the road. By comparing expectations with subsequent reality, Schwandt could look at how right or wrong people had been about their future happiness.

The result astonished him, not just because the pattern was there, but because it was there for both men and women, and it was there for both eastern and western Germans (people whose prior experiences of life, in the Cold War years, had been very different), and it was there within individual people as well as groups of people. It didn’t go away when Schwandt checked for major events like recessions which might have disrupted people’s lives. It persisted when he performed statistical adjustments for things like income and demographics. As he would later write: “This pattern is stable over time, observed within cohorts, within individuals, and across different socio-economic groups.” The pattern was so strong—in fact, plainly visible to the naked eye, without any statistical manipulations—that at first Schwandt thought he might have miscoded the data. He hadn’t. “I thought: this must matter.”

At first, he wasn’t sure precisely why it might matter, though he had a general idea. He was aware of the happiness curve, and was intrigued by the lack of an explanation for it. For a while, though, he went back to his more mainstream work on the economics of health and wellbeing. He had not, after all, received much by way of encouragement. “This was my first project in my PhD. I remember presenting this in front of a group of macroeconomists, and they were literally laughing at me. I still remember: They found it really ridiculous that I would do this. They asked me literally why anyone would care about expected life satisfaction.”

One economist who did not think his findings were ridiculous was Andrew Oswald. When they connected at a conference, what was supposed to have been a brief breakfast turned into a two-hour conversation. “He said, ‘Wow, this is so important,’” Schwandt recalled. And so, returning to his work comparing expectations with reality, Schwandt developed an article which was published in 2016 in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, under the title, “Unmet Aspirations as an Explanation for the Age U-Shape in Wellbeing.”

Here is what Oswald saw in Schwandt’s paper that so excited him:

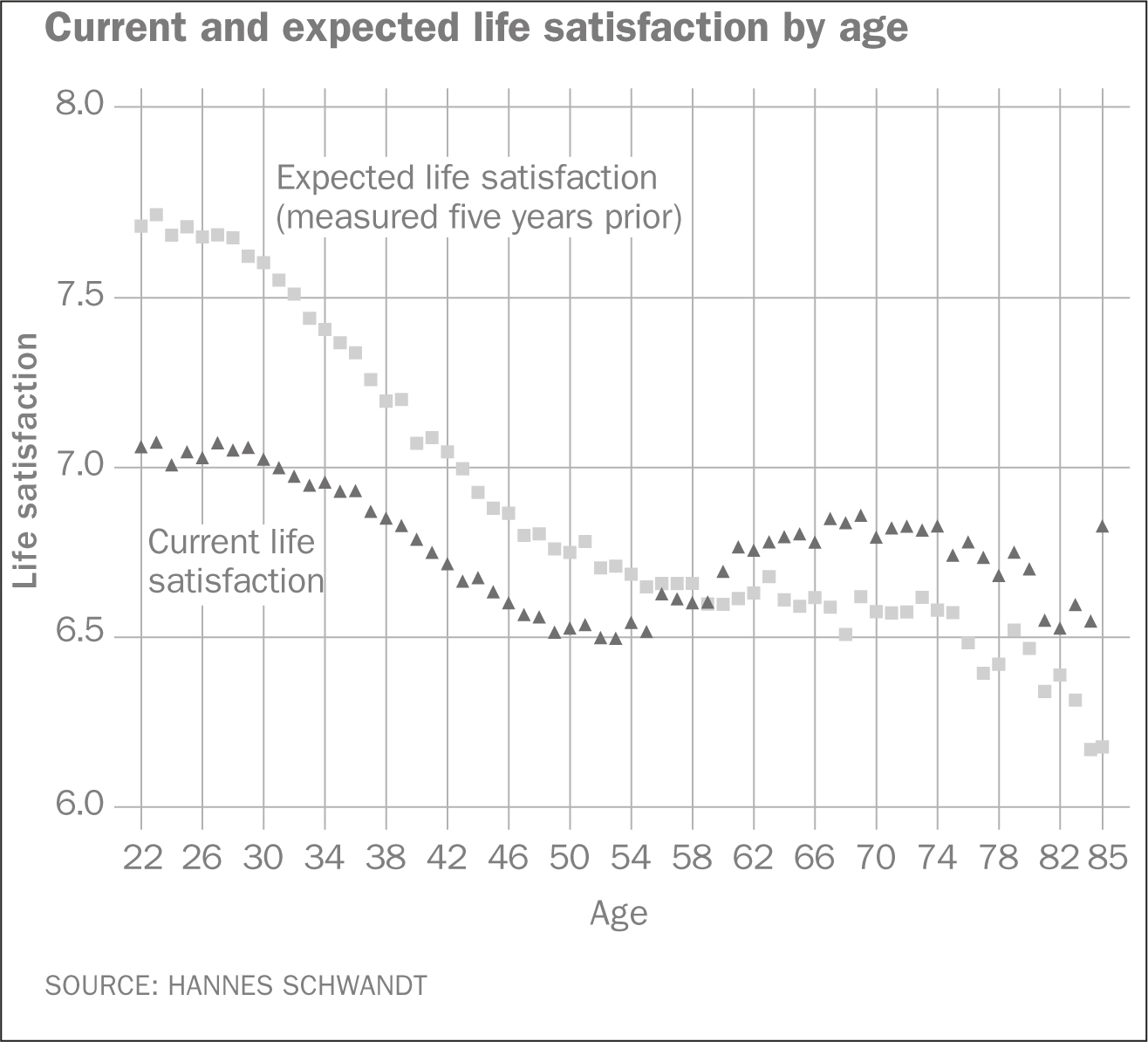

And what does the graph show? Germans in the database, whose ages range from seventeen to ninety, were asked to rate their current and future life satisfaction on a standard scale of 0 (“completely dissatisfied”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”). The triangles show how satisfied people actually are at every age. The squares show how satisfied they had expected to be five years prior. The curves are lined up to compare prior expectations with subsequent reality. For example, twenty-five-year-olds expect their satisfaction to rate about 7.5 when they reach the age of thirty; but when they actually are thirty, their satisfaction is only 7. In other words, they are not as happy with their lives as they expected to be. In yet other words, they’re disappointed. When the line of triangles is below the line of squares, people are disappointed with their state of contentment. When the line of triangles is above the line of squares, they’re pleasantly surprised.

A couple of things are immediately apparent from the graph. The line of triangles—current life satisfaction—shows the U pattern (until old age, when survey subjects get sick and die off and the data gets thin and messy). The bottom is just where one might expect, at around age fifty. No surprises there!

Second, however, is this: young people consistently overestimate their future life satisfaction. They make a whopping forecasting error, as nonrandom as it could be—as if you lived in Seattle and expected sunshine every day. “These errors are large,” Schwandt comments, in his article. Young adults in their twenties overestimate their future life satisfaction by about 10 percent, on average. Over time, however, excessive optimism diminishes. Perhaps because they have been disappointed so regularly in the past, and perhaps because they feel that most of life’s adventurous, healthy years are behind them, their expectations fall. Not to 0: a drop from 7.5 to 6.5, though big, is not catastrophic. People are not becoming deeply depressed. They are becoming, well, realistic.

Look what happens in the fifties. The U curve begins swinging upward. Meanwhile, expectations have almost completed their downward drift. The expectations gap closes—and then reverses. Life satisfaction in late middle age and beyond, contrary to prior expectation, is growing, not shrinking. But expectations have plateaued at a low level. For a good twenty years, every year brings, not another dose of regret and disappointment, but another pleasant surprise. So there is the undertow, and its reversal. The forecasting errors that bring so much grief in the earlier part of life switch sign in the latter portion. The current shifts.

* * *

All of that—the expectations gap and its reversal—is fairly readily apparent at a glance. Hannes Schwandt, however, being an economist, did some math to seek relationships which may not be so obvious. The expectations-versus-reality gap turns out to have a peculiar self-referential characteristic, which helps explain why so many people, I among them, have felt, in middle age, that obnoxious sensation of being both puzzled and trapped.

Recall that people are not being asked here to rate expectations for their future situations in life. The question is not, say, “How much income do you expect in five years? How much health? How good a job?” Those would be questions about objective circumstances. Instead, people are being asked about something subjective: how satisfied they expect to feel in five years, and then, later, how they actually do feel. And feelings can operate on themselves. Disappointment and regret can make us dissatisfied. Dissatisfaction can add to our disappointment and regret.

The result turns out to be something which is quite easy to model mathematically—Schwandt wrote an equation for it—and which quite elegantly matches up with observed results. He calls it a feedback effect, and it helps explain why sometimes people with little to be dissatisfied about nonetheless feel so dissatisfied, and then feel dissatisfied about feeling dissatisfied. After showing me some equations, Schwandt explained it this way:

“Let’s say you’re at this stage where you feel midlife discontent. And let’s say things are really bad, that there are a lot of challenges in your life or things have turned really sour. Then you’re depressed, but at least you’re like, ‘Wow, there are good reasons to be depressed.’ It’s clear to you why you feel bad and that’s kind of the end of the story. You probably also share your problems more with other people, or other people acknowledge why you’re dissatisfied.

“But say you’re on a track where everything looks nice. Then you feel discontented. Instead of just saying, ‘I’m discontented because of this and that thing,’ and that’s it, you say, ‘I’m discontented and I don’t know why,’ and this makes you more miserable, and this makes the forecasting error even larger. So you keep the circumstances constant, but you feel bad about them. Since you feel bad about them you’re disappointed, your life satisfaction decreases and you feel even worse about that. You’re in a downward spiral. If your objective life circumstances are actually really good, this feedback effect might just be stronger—because you’re more disappointed about being disappointed.”

In his paper, Schwandt writes: “The mathematical model shows that this mechanism has explanatory power even in a world in which the utility derived from life circumstances is constant over age.” In other words, the math demonstrates that downward spirals can happen quite independently of one’s actual circumstances in life. The feedback effect can and often does afflict people who do not experience any severe crisis or shock, people who, on the contrary, are doing fine. Schwandt writes: “The feeling of regret about unmet expectations further increases the gap between expected and realized life satisfaction, leading to yet greater disappointment and a further lowering of life satisfaction.” That is a pretty good description of how I felt in my mid-forties. It was a frustrating and mystifying place to be.

Schwandt’s model helps explain why the happiness curve keeps appearing after economists factor out life circumstances: that is, why age itself, independent of other things that may be going on, keeps showing up as associated with lower satisfaction in midlife. Sometimes the people who are, relatively speaking, least affected by objective circumstances will be most trapped in feedback loops.

One can dismiss such objectless disappointment as a yuppie problem or first-world problem (though in fact the happiness curve turns up in many developing countries). One can dismiss it as whining. Which was exactly what I did when I experienced it. Whining was something I felt I had no right to do, given my privilege and good fortune. My dissatisfaction reduced my self-esteem. It made me dislike myself. It made me embarrassed to tell people I was in a rut.

Ironically, such embarrassment, although perfectly justifiable from a moral or objective point of view (everyone loathes a whiner, especially when the whiner is oneself), is a cause of yet more dissatisfaction and disappointment. All the things we have learned since childhood about the shame of ingratitude can turn against us by accelerating Schwandt’s weird spiral of disappointment. Counting my blessings, as I did on the threshold of forty, was a worthy exercise morally; I’m glad I did it. But, in light of Schwandt’s equation, I am no longer surprised that it didn’t help. Unknowingly, by trying to explain to myself why I ought to be more satisfied, I was giving myself more reason to dwell on the gap between how satisfied I felt and how satisfied I thought I should feel.

You see, then, the peculiar character of the feedback effect. Like the 1990s television comedy show Seinfeld, midlife slump can be about nothing. That very fact can itself be profoundly troubling. I think of my friend Simon. In his mid-forties, he has had his share of ups and downs, and his pattern is a familiar one: exciting twenties, progress toward goals in his thirties, turbulence in his forties, including some hard knocks. At last he had achieved success and prominence in his chosen field, becoming a media figure in a major market. “I’ve done everything I want to do, for the most part.” So did he feel content? “No. Exhausted. I feel at times like an amazing fuck-up who has gotten away with stuff, who has been lucky. I’ve thought of running away to Brazil. Changing my name and becoming a hotel clerk.” His dissatisfaction mystified and troubled him at a deep level that seemed not just emotional but spiritual. “I think it must be something internal,” he told me. “I see life as a challenge to overcome rather than an adventure to be enjoyed. If I did a deep psychological dive, I might say that nothing will ever make me content. Maybe there’s something deeply psychologically wrong with me.”

There’s something wrong with me. That is the feedback trap talking.

* * *

Now look at what happens as people move through their early decades of adulthood: the expectations gap steadily narrows. You might think this would be a good thing: my actual feeling of disappointment shrinks as I shed my unrealistic optimism. So why the U-shaped curve, indicating steadily less satisfaction through middle age? Partly because of the feedback effect. But also, Schwandt thinks, because of what he calls a “hump-shaped regret function.” As he told me, “Life satisfaction depends on circumstances right now minus the regret that you feel about the sum of missed chances in your past life.” In plainer English, his math suggests that feelings of disappointment are cumulative.

“When you’re young,” Schwandt explained, “you don’t really feel so much regret, because even if things don’t turn out so well at the beginning, you still think there’s time. You don’t really care so much.” When you’re twenty-five, a disappointing year is just a bump in the road. Next year will be better!

But then what if, where life satisfaction is concerned (remember, we’re talking about the inner, subjective world, not about what’s actually happening to you), next year brings another disappointment? Things are pretty good, but you’re not as content as you expected to be. Then the same thing happens the next year. And the next. And the next and the next and the next. After a while, it dawns on you that disappointment seems to be a permanent feature of life. This has a couple of effects. On the one hand, your expectations for future satisfaction fall—pretty quickly, as the graph shows. So the hard work of realigning your happiness expectations is being done. But meanwhile, until the realignment happens, you’re being hit from two directions at once. “On the one hand,” Schwandt told me, “you feel all this disappointment about your past. And then also your expectations evaporate about the future. So in midlife you’re feeling miserable about the past and the future at the same time.”

This would go a long way toward explaining why, for example, Anthony, at age forty-six, though not depressed, is certain he has peaked. He has found that getting most of what he wanted does not make him as happy as he expected, a fact to which he is resigned—and which implies even less satisfaction in the future, as his physical and intellectual faculties decline. He is looking at his future circumstances and drawing what seems a logical conclusion about his future satisfaction: the best is behind him. He can’t intuit that when Schwandt’s lines cross, when reality begins to outperform expectations, the spiral changes direction. Positive feedback replaces negative as disappointments become pleasant surprises, and as growing satisfaction and gratitude reinforce each other.

So the story of expectations realigning with reality has a happy ending. But the only way out (to paraphrase Robert Frost) is through. The passage through is not generally traumatic; remember, we’re dealing with larger and smaller amounts of satisfaction, and with disappointment relative to high expectations. But it is a grind.

“Resigned,” Jasper said, when I asked how he feels about his life. We met at the neighborhood gym. He had seen an article I wrote about the happiness curve, and we struck up a conversation because, having recently turned forty, he felt himself inching toward the trough of the happiness curve. He had risen rapidly as a young lawyer in his twenties, a period he describes as “fun, future-oriented”; but in his thirties came the realization that the practice of law was a “soul-sucking grind,” that he was not the husband he wanted to be, and that he and his wife could not have kids. He had responded, readjusted: left the rat race, gone back to school, adjusted to childlessness. Now, in his early forties, he was managing a family dental practice, but only, he hoped, temporarily. He had set his sights on a new career teaching and writing about the things he cares most about.

With so much to look ahead to, I wondered, why was he resigned?

“I suppose by the time we hit forty,” he said, “most of us have run up against a reality that can look pretty different from the future we anticipated for ourselves at age twenty-five. There’s a definite spiritual maturity, a deepening self-awareness and introspection that result from embracing the truth about ourselves and our frailties and failures as well as our successes. So I wouldn’t say I’m not grateful for the wisdom that comes with experience. But there are times when I miss having a more simple and naïvely optimistic outlook on life—even if I know now that such an outlook required almost willful disregard of life’s realities.”

Jasper was in the process of bidding farewell to what Hannes Schwandt describes as a forecasting error, and what Thomas Cole depicts as a castle in the sky. Jasper missed the high expectations of the past, even though he knew they had misled him. Objectively, he was in the process of bringing his life into closer alignment with his values. But subjectively his optimism about his future life satisfaction had waned, and its decline was itself a source of regret.

* * *

The natural question for me, pondering Hannes Schwandt’s expectations gap, was: Why? Why the big forecasting error? It turns out there are answers to that question, but they move us from economics and big data, Schwandt’s world, to psychology: the construction and organization of our minds.

Tali Sharot, Israeli by birth, is a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, where her duties include directing the Affective Brain Lab, a center which studies how emotions affect cognition and behavior. She is particularly well known for her work on what she calls optimism bias (in fact, she has written a book by that name). Positive forecasting errors, she has found, are no biological mistake. They appear to be wired in. For all that they mislead and sometimes immiserate us, we may need them to survive and thrive. “It’s hard for us to get out of bed unless we can say, ‘Oh, it will be a great day, I’m going to succeed in what I’m doing,’” she told me. In a 2011 article in Current Biology, she described optimism bias this way:

[Students] expect higher starting salaries and more job offers than they end up getting. People tend to underestimate how long a project will take to complete and how much it will cost. Most of us predict deriving greater pleasure from a vacation than we subsequently do, and we anticipate encountering more positive events in an upcoming month (such as receiving a gift or enjoying a movie) than we end up experiencing. Across many different methods and domains, studies consistently report that a large majority of the population (about 80 percent, according to most estimates) display an optimism bias. Optimistic errors seem to be an integral part of human nature, observed across gender, race, nationality, and age.

People expect to have above-average longevity and health, underestimate their likelihood of divorce, overestimate their job success, and so on. They expect positive events in the future, “even when,” as Sharot and several coauthors reported in the journal Nature, in 2007, “there is no evidence to support such expectations.”

What happens if you give people accurate information? Will they correct their biased beliefs? In experiments, Sharot and various colleagues ask people about the likelihood that various bad things (a robbery or a cancer diagnosis, for instance) will happen to them over, say, the next five years. Once their answers are recorded, the subjects are informed of the actual odds, and then asked again whether the events will happen to them. It turns out they are better at assimilating positive than negative information. Sharot calls this the “good news/bad news effect.” If you put people in a brain scanner and perform the same kind of exercise, positive information and negative information appear to be coded by different regions of the brain—so the bad is not simply the inverse of the good. Moreover, Sharot and her colleagues found they could make the optimism bias disappear by aiming bursts of magnetic energy at a specific region of the brain. The implication is that we are wired to accentuate the positive and screen out the negative, not just in our emotional outlook, but in our basic cognitive functioning.

Well, most of us, most of the time. There is an exception. Mildly depressed people predict the future accurately. It turns out that they are just as good as nondepressed people at taking in positive information, but they are more responsive to negative information, and thus more realistic. “They see the world as it is,” writes Sharot in a 2012 ebook, The Science of Optimism: Why We’re Hard-Wired for Hope. “In other words, in the absence of a neural mechanism that generates unrealistic optimism, it is possible all humans would be mildly depressed.” In fact, humans aren’t the only ones who seem wired for optimism. Ingenious experiments find that birds are, too. And mice. And other species.

Why would nature bias us to be optimistic, and therefore subject to continual disappointment? Perhaps because realism is bad for you. “Hope keeps our minds at ease, lowers stress, and improves physical health,” Sharot writes in The Science of Optimism. “This is probably the most surprising benefit of optimism. All else being equal, optimists are healthier and live longer.” In fact, “optimism is not only related to success, it leads to success.” Optimism inspires entrepreneurs to launch start-ups, despite dismal odds. I know: I tried a start-up. I was confident it would succeed. It failed. But I’m still glad I was unrealistic enough to try.

Optimism bias as a general idea is well established. Less firmly known, but tantalizing, is the idea, which researchers are now getting hints of, that optimism bias is not age-neutral. Rather, it seems to reach low ebb in middle age. Sharot writes, in The Science of Optimism:

How easily people learned from good news was relatively stable across age groups; they were pretty good at age nine, and they were still pretty good at ages forty-five and seventy-five. However, how well people learned from bad news followed an inverse U shape. From the time we are children, we slowly acquire the ability to alter our beliefs accordingly when we receive bad news (like learning that things we love, such as candy, may be bad for us). This ability seems to peak around age forty, and then it slowly deteriorates as people grow older.

In other words, people in middle age may be more likely than others to suffer from what has been called depressive realism, a heightened receptivity to lessons from the school of hard knocks.

“Why,” I asked Sharot, “might depressive realism be more common in middle age?”

“Unclear,” she replied. Maybe because the brain changes as it ages. Or maybe because stress is often high during midlife, and stress and anxiety reduce optimism bias. To mention the obvious, people might simply be learning from experience. Of course, the explanation could include all of the above, and more. For the young to sally forth optimistically into the world, taking risks and pushing limits, might serve the species’ interest; a subsequent recalibration in maturity might also be useful.

The research does not imply that middle-aged people are depressed. They still have an optimism bias. It is just smaller, noticeably so. They have received a dose of depressive realism. Jasper might be inclined to agree.

* * *

As my diary writing and blessing counting attest, when I was Jasper’s age I, too, had begun to feel, and feel disturbed by, declining optimism. My passage through my thirties had been smooth. I was fine with not having kids (a different internal conversation if you’re gay than if you’re straight). I didn’t need or want a change of career. No health trouble or financial problems. Having experienced no setbacks, I assumed I was in a temporary funk, a phase which would pass pretty soon (after all, there was no reason for it!). What finally got my attention, convincing me that something peculiar was going on, was an event that happened when I was forty-five. A positive event. Spectacularly positive. I had come to accept that my low-key style of journalism lacked the sort of sizzle that appeals to competition judges, and so when I won a National Magazine Award, the magazine industry’s equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize, it came as a complete surprise. It filled me with pride and gratitude and a sense of earned success. For about a week. Maybe two.

Then, creepily, with a mind of its own, the dissatisfaction oozed back. Soon it was as if the award had never happened. As ever, I found myself awakening most mornings to an unbidden, unwanted internal monologue badgering me about my underachievement. That was when I began reckoning with the reality that my nagging sense of disappointment had taken on a life of its own. It had become, apparently, a feature of my personality, always hunting for something to be dissatisfied about, and inventing spurious dissatisfactions if no real ones were on hand. Faced with the irrational persistence of my disappointment, I started to doubt my capacity to feel gratitude and satisfaction. That, I think, was when Schwandt’s feedback loop really kicked in. How, I wondered, could even the most tangible of achievements fail to turn me around? What I didn’t know was that the problem wasn’t me; it was my elephant.

* * *

Jonathan Haidt started his career on a disgusting note. Today, as a psychology professor at New York University, he is one of the world’s most innovative thinkers about the ways in which intuition, the sum of our involuntary sentiments, shapes human reason and cognition. Born in 1963, he suffered what he calls an existential depression during his senior year in high school, deciding that without God life must be meaningless. He turned to philosophy for answers, but discovered that psychology was more fun. After college, he spent a couple of years writing computer programs for the Bureau of Labor Statistics in Washington. Somehow, in the Mixmaster between his ears, his interests came together to propel him toward the empirical study of moral intuition. For his dissertation, he chose an intuition which had received little formal study: disgust. His doctoral dissertation was called Moral Judgment, Affect, and Culture, or, Is It Wrong to Eat Your Dog?

In a career’s worth of subsequent experiments, Haidt has found that gut feelings like disgust influence our reason much more than the other way around. He likes to compare reason to a press secretary, pushed forward by our rationalizing minds to justify choices we make at a gut level. “The central insight that I had in moral psychology,” he told me, “was: keep your eye on the intuitions, the gut feelings, and the reasoning follows.”

Memorably, and now famously, Haidt likens the reasoning mind to a rider perched atop an elephant. Historically, he notes, a common metaphor for thinking about emotion and reason is that of a horse and rider. But riders direct horses, absent a snake or stampede. That metaphor clashed with Haidt’s findings, including those in a natural experiment that he had conducted upon himself. “At the time I was single and I was dating,” he recalled. “I would make some big mistake in my dating life, and I would see myself making a mistake, and I saw that I was going to go ahead and make it, even though I knew it was the wrong thing to do. I knew what the right thing was and I knew all the psychology about the wrong thing, but I couldn’t stop myself.”

Apparently, if he and his experimental subjects were riding something, it was no obedient horse. “Elephants are really smart, and they’re really, really big, and I felt like a small boy perched atop a giant elephant. If the elephant didn’t have any plans of its own, the boy can kind of prick it and turn it this way and that.” But if the elephant has its own ideas, it goes whichever way it pleases. The rider is left to rationalize the elephant’s direction or look on in frustration, or both.

The elephant, for Haidt, is the mind’s many automatic, involuntary processes; the rider is the mind’s controlled, voluntary processes. Unlike Freud’s subconscious, the involuntary, nonconscious form of mental processing is not some swirling cesspool of guilt and taboo and childhood trauma. It is more like a system of cognitive shortcuts allowing us to function in everyday life, because we don’t have nearly enough time or capacity to think through every decision from scratch. Disgust says Ick! sparing us the trouble of deciding whether to touch or eat something unfamiliar and potentially hazardous. The automatic processes, unlike the ones under conscious control, happen unbidden; they tend not to slow down when you’re tired; they do not require willpower or concentration. You are not aware of the process, just the output—for example, realizing someone is attractive. “It’s just bang,” Haidt said. “You’re aware of the attraction, though a huge amount of neural computation went into that attraction.”

When, at forty-five, I won that journalism prize, I—the rider—was very pleased. So I gave the elephant a pep talk: This is great! This is a lifetime achievement, a validation of my whole career! Yay! Quit sulking! Be pleased! And stay pleased! So … why didn’t the elephant stay pleased? When I asked that question of Haidt, he replied by asking me if I had seen the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

“Sure,” I said.

“And who’s running the spaceship in that movie?”

“HAL, the onboard computer.”

“And what is HAL’s goal?”

“To complete the mission.”

“And does HAL care if the crew is happy?”

“Well … no.”

The elephant’s mission, said Haidt, is not to make us feel satisfied with what we accomplish or do. “The elephant’s mission is to make us successful in producing offspring: in doing the things that will lead to the successful completion of the mission of life on earth. The elephant is especially concerned that you get prestige. The elephant was created by evolution to complete the mission. And happiness is not the goal of the mission.”

The elephant, as we have seen, is biased toward optimism. It is also biased toward disappointment. In his fine 2006 book, The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom, Haidt enumerates various ways in which the elephant undermines the rider’s efforts to savor success. One is the progress principle. We set many goals in life: status, friendship, finding a good mate, accumulating resources, rearing children so that they will give us grandchildren and great-grandchildren. But the mental reward for success, a shot of encouraging dopamine, comes mainly not when we meet some big life goal that we’ve set for ourselves intellectually, but when we take some short-term positive step. “Here’s the trick with reinforcement: it works best when it comes seconds—not minutes or hours—after the behavior,” writes Haidt. The elephant “feels pleasure whenever it takes a step in the right direction.” In other words, “when it comes to goal pursuit, it really is the journey that counts, not the destination. Set for yourself any goal you want. Most of the pleasure will be had along the way, with every step that takes you closer. The final moment of success is often no more thrilling than the relief of taking off a heavy backpack at the end of a long hike.” That is the progress principle: “Pleasure comes more from making progress toward goals than from achieving them.” For me (or for my dopamine system), winning that prize was not like taking off a heavy backpack, but it was of startlingly short duration. Just another step on a path.

Toward what? Having only just arrived, my elephant was already craving more dopamine, demanding progress toward some new goal—even though I had none in mind. That is the adaptation principle. “We don’t just habituate, we recalibrate,” writes Haidt. “We create for ourselves a world of targets, and each time we hit one we replace it with another. After a string of successes we aim higher; after a massive setback, such as a broken neck, we aim lower.” Unfortunately, the rider is not in on the secret. “Whatever happens, you’re likely to adapt to it, but you don’t realize up front that you will. We are bad at ‘affective forecasting’—that is, predicting how we’ll feel in the future. We grossly overestimate the intensity and the duration of our emotional reactions. Within a year, lottery winners and paraplegics have both (on average) returned most of the way to their baseline levels of happiness.”

From the elephant’s point of view, this kind of constant recalibration may be adaptive, keeping us abreast of changes in our environment. From the point of view of the rider trying to appreciate what he or she has accomplished or accumulated in life, it is not so good. “When we combine the adaptation principle with the discovery that people’s average level of happiness is highly heritable,” writes Haidt, “we come to a startling possibility: In the long run, it doesn’t much matter what happens to you. If this idea is correct, then we are all stuck on what has been called the ‘hedonic treadmill.’ … We continue to strive, all the while doing things that help us win at the game of life. Always wanting more than we have, we run and run and run, like hamsters on a wheel.”

To all of which, add the phenomenon we encountered in chapter 2: the social-competition treadmill. Haidt describes it:

The elephant was shaped by natural selection to win at the game of life, and part of its strategy is to impress others, gain their admiration, and rise in relative rank. The elephant cares about prestige, not happiness, and it looks eternally to others to figure out what is prestigious. The elephant will pursue its evolutionary goals even when greater happiness can be found elsewhere. If everyone is chasing the same limited amount of prestige, then all are stuck in a zero-sum game, an eternal arms race, a world in which rising wealth does not bring rising happiness.

I confess that, after I won my big award, I got some joy from the improvement in my prestige; and, I won’t lie to you, I still do. But my elephant kept gazing up the social ladder, not down; it quickly took on board my success, recalibrating; it demanded more achievement. Recalling my plight, I suggested to Haidt that the elephant’s priorities seemed designed to make us unhappy. He demurred. “They’re not designed to make us miserable. They’re designed to motivate us to be successful. A life of contentment is not motivating for success. Contentment means you can stop.”

This is not to say we are always dissatisfied or disappointed. As Haidt emphasizes, the trick is to depend less on trying to talk the elephant into being satisfied, as I was doing in my forties, and instead to give it an environment where the things it wants and the things the rider wants are in closer alignment. That would be an environment rich in the ingredients of sustainable satisfaction: ingredients like a high-trust social environment, adequate health and income, a goodly amount of control over our lives, and, above all, strong and supportive social bonds. When I asked Haidt if the elephant metaphor had affected the way he leads his own life, he replied: “Absolutely! I see my own life and my own mind much less as a machine, much less as a project or city to be built, and much more as giving myself the right kinds of experience and exposure and letting time do the work. Life is about training and educating the elephant and the rider, and getting them to work together in harmony.”

* * *

A life in memory, like a great painting, changes with the light it is seen in.

In my mind’s eye, I am almost twenty again, beholding for the first time Thomas Cole’s quadriptych in the National Gallery of Art. To the younger me, the swaddled innocence of Cole’s Childhood certainly rings true. So do the (literally) sky-high aspirations of Youth. Standing on the foothills of maturity, I want to make a mark on the world, though I have no settled ambitions.

I had no way to know what the light of hindsight and recent scientific learning would show. I would do well professionally. I would find love and commitment, albeit not oriented as I expected. I would have everything to be grateful for. But the castle in the sky? Perhaps that glittering elusive palace is not the objective situation we expect to attain—our material and social ambition—but the happiness we expect to reach: our subjective ambition. After all, one of the most striking facts about The Voyage of Life is that the Voyager is alone. There are no other people, no cities, no society. One interpretation is that Cole was naïve about the importance of social connections in life. Another is that he was portraying not life’s circumstances but its psychology: the inner world, where we are all, finally, alone. Perhaps what he is telling us is that our inner river will bend away from satisfaction, and that the rapids and crags are within ourselves.

Cole was a visionary whose time was far removed from our own, so I can’t say exactly what he meant. What I can say—or, more precisely, see—is what the twenty-year-old version of me got wrong. I was certain in youth that I would be better off objectively by middle age. That forecast was accurate. My conditions improved. But I also made another youthful forecast: that my satisfaction would keep pace with my accomplishments. That forecast was off. Yes, I was appreciative, but nowhere near as appreciative as I had believed I would or should be. The closing of the optimism gap, plus upward social comparison, plus the hedonic treadmill and my elephant’s other tricks to keep contentment out of reach: all of those things, as the years ticked by, conspired to create a sense of disappointment which I couldn’t shake by force of will. And that was disappointing. In my forties, caught in the feedback loop, I was stumped and stuck.

* * *

If Cole were painting his Voyage of Life today, he would need to add a fifth painting, one between Manhood and Old Age—but I’ll come back to that. First, I linger for a moment on what is, to me, the most interesting (if also the least pleasant) place on the happiness curve: that in-between region of middle age where Schwandt’s lines are in the process of converging and crossing. Here, the expectations gap is closing, but has not yet closed. Disappointment will soon end, but still seems endless. Realism has arrived, but not yet settled in. Here is the bottom of the U, a treacherous zone.

It is important to see what this time of unfinished transition is not: a crisis. At least, not usually. The whole point of Schwandt’s research—and Sharot’s, and for that matter Andrew Oswald’s and David Blanchflower’s and Carol Graham’s—is that the curve implies no disruption or discontinuity in our emotional wellbeing. Change is gradual and cumulative, a buildup of increments of disappointment as youthful optimism bias is squeezed away. In fact, as Schwandt’s math shows, negative feedback implies that we can still feel a cumulating sense of disappointment even without any objective disruption or emotional trigger at all. The idea of midlife “crisis” thus misses the point. Instead, to understand what’s going on in this transitional phase, and why people’s experiences of it vary widely, consider the stories of three people I interviewed: Randy, Mary Ann, and Margaret.

Randy, at forty-four, is an example of someone who feels the undercurrent of disappointment all the more keenly for having had smooth sailing. His emotional set point is healthy, his external conditions comfortable, and his personal choices wise, but his sensible steadiness has given full rein to the effects of time. He achieved his career goals and has a happy marriage and a thriving son, but, for the reasons we’ve seen, arrival didn’t bring satisfaction. Going by the statistics, he has been on the downslope of the curve for a few years and might not hit the upturn for a few years more, and so he is in that particularly difficult period near the bottom when disappointment seems eternal. When I asked him to characterize his forties, he replied: tired, fatalistic. Why fatalistic? “I’ve been in the same job more than ten years. In the field that I’m in, which is downsizing and changing rapidly, I’m feeling that things are now less up to me to change and they’re more predecided. In my twenties, I felt I had the power to do what I want to do and try new things and experiment. Now I feel like if I want to stay in the kind of lifestyle that I have, which is a nice house, supporting a child, saving for college, going on vacation with my family, here’s what I’ll need to do: I’ll need to stay in a job that’s well paying, even if I don’t always enjoy it. That’s what I mean by fatalistic. There’s less room for experimentation.”

Does he ever have escape fantasies? “Of course.” On a vacation in Mexico, kayaking on a beautiful lagoon, he admired the sunset. “I thought, I want to do this: pull up stakes and live in Mexico and look at the stars at night.” Sometimes he fantasizes about retiring early. “Can I really do this for another twenty years? Am I going to get up at six a.m. every day and keep doing what I’m doing? I just have to shake my head. No. I don’t want to. So I am trying to imagine what else I can do.”

I asked: “Are you having a midlife crisis?”

“I’m at midlife. But a crisis seems to me something that’s sudden and then suddenly resolved. There’s probably a better word for something that’s long-lasting.” He said he imagines an uptick in his life satisfaction a few years hence: from six to maybe seven. But in the next breath he acknowledged that his optimism is, to some extent, forced. “I try to stay optimistic because, if I didn’t, there wouldn’t be much point in going on. By whatever means, I’ve been able to develop a pretty strong core to deal with things.” To me, this sounded less like optimism than like soldiering on.

Talking to Randy, I thought of what Hannes Schwandt said: On the one hand, you feel all this disappointment about your past. And then also your expectations evaporate about the future. So in midlife you’re feeling miserable about the past and the future at the same time.

Randy isn’t miserable. When I see him interact with his affectionate wife and his exuberant eleven-year-old son, I know he isn’t clinically depressed. I believe him when he says he realizes he’s lucky. But he is at that wearisome juncture where the past feels like a stream of accumulating disappointments and the future is still around the bend.

Randy’s case contrasts tellingly with that of Mary Ann. Like him, she is a forty-four-year-old professional. Unlike him, in midlife she encountered the kinds of catastrophes we all dread. The result, though, is that she seems to have shifted her disappointment curve—thereby advancing the realism and acceptance which people with fewer problems rely on time to bring.

Unlike most people I interviewed, Mary Ann is someone who embraces the term midlife crisis, and it is easy to see why. In rapid succession, her mother received a cancer diagnosis; then Mary Ann herself received a cancer diagnosis, which was a false alarm; then she received another cancer diagnosis, which was not a false alarm. Meanwhile, her husband ran into an exotic and hard-to-treat health problem, and her father-in-law died.

“I’ve hit my midlife crisis,” she told me. “All the sorts of things that are supposed to precipitate midlife crisis hit—poof—in my forties. You come smack-dab slamming into the concept of your own mortality. It makes you feel really old, really fast. You’re facing mortality, you’re feeling old, you’re thinking there are more achievements behind you than ahead. These are the hallmarks. I’m textbook in some ways.”

Mary Ann’s feelings are complicated, though. Describing her forties, she used the words: anxious, reflective, appreciative. Why, amid all the jolts, appreciative? She and her husband are healthy now, and her expectations have been reset by their ordeal. “Once you come through, you think: my god, I do have a great life. I’ll just sit outside sometimes when the weather is nice and think: yes!” On the Cantril Ladder scale, she rates her current life at seven: down from the eight she gave her twenties and thirties, but not bad. She sees the future as unlikely to bring the kinds of adventures she once had, but she seems to be making her peace with that. “I don’t feel so old that I don’t feel surprises are possible,” she said. “I don’t rule out the possibility of big shifts. I just don’t expect them.” And is that okay? Again, a mixed answer. “No one’s happy about coasting or sliding. But I’m not flipping out about it. I’m too old to sweat the small stuff.”

Mary Ann actually is not old at all, but she uses the phrase too old to refer, not to her objective age, but to her subjective position on the happiness curve. Schwandt suggests that the presence of objective difficulties in midlife—things like health crises—can mitigate emotional difficulties by helping people understand and accept their disappointment, thereby protecting them from a negative feedback cycle. I would not for a moment say there was anything desirable about Mary Ann’s bruising trials, but her encounters with mortality and suffering may have boiled off unrealistic optimism which otherwise would have taken longer to leach away. Her family’s crises seem to have taken her on a shortcut to the mature realism of the latter portion of the expectations curve. Her chronological age is the same as Randy’s, but her life-satisfaction age seems, perhaps, ten years ahead of his.

If the transition to realism sounds dreary and gloomy, take heart. The draining away of unrealistic optimism, although a grind when underway, can cast a freshening light on life. Take Margaret. An Australian in her early fifties, she has rounded the bend that probably lies a few years ahead for Randy. Her forties brought uncertainty, unsettledness, a series of jobs that didn’t feel right, but her fifties? Industrious, settled, are the terms she uses. When I probed, I learned that by “settled” she means that she has settled down, but also that she has settled for. Her job still isn’t quite the right fit, but it is pretty good and she can settle for it. “It’s good enough. I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ve accepted an area of work that’s not my ideal, but it’s still very satisfying.” Meanwhile, she finds satisfaction in pursuits which might have seemed less worthwhile to her younger, more ambitious self. A piece of jewelry broke, so she took a jewelry-making course. She learned to knit. She took sewing lessons. “I come out of it feeling so refreshed and relaxed, like I’ve had a big rest. It’s using a different part of the brain. I feel like there’s more of a balance.” She describes herself as happier than she has ever been. I can tell that Margaret is surprised by the pleasure she is getting from what she calls her “little courses.” She uses the word awakened to describe her life.

On Hannes Schwandt’s map, Margaret has passed the crossing and reached the place where expectations are realistically low and satisfaction surprisingly high. On Thomas Cole’s map, she is out of the rapids.

* * *

Talking to Jasper and Randy and Margaret, and to many others, it dawned on me that we don’t have a good vocabulary for the rich and ambivalent mixture of emotions they are encountering in midlife. Clinical words like depression and anxiety don’t fit; dramatic words like crisis don’t fit, either, at least not reliably. Malaise is pretty good, but it is one-dimensional and needs fleshing out. I hear fatalism and resignation from Randy, something like acceptance from Mary Ann, and something closer to satisfaction from Margaret. I hear, in Randy, a note of mourning for optimism lost, but in Margaret, a note of relief at letting go of the ambition that is optimism’s burden (Jonathan Haidt’s “heavy backpack”). From Mary Ann I hear notes of sadness, but also notes of lightness. And so on. The feelings my midlife interviewees describe are too complex and rich to fit easily into any standard emotional box.

The unscientific but, I think, revealing survey research I did for this book drives home the emotional ambivalence and richness that characterize the midlife passage. When asked to rate and describe their state of satisfaction in each decade of life, my respondents send clear signals about their twenties (fun, exciting, hopeful, busy, uncertain, adventure, ambitious, free) and their sixties and seventies (happy, satisfied, content). But in describing their middle decades, respondents proffer a messy mixture of positive and negative and neutral. At the bottom of the happiness curve, it seems, you can’t tell a simple story about the textures of life, because expectations and reality and personality and choices and age are all hurling themselves at you and interacting with each other.

Amid all the complexities, though, one finding turned up invariably: no one sees around the bend in the river.

Remember, the optimism which diminishes through the middle decades of life is optimism about our future life satisfaction. The long downturn of the happiness curve conditions us to expect disappointment, and so naturally a turnaround is the last thing we foresee.

There is a famous scene toward the end of the film The African Queen in which the protagonists, their boat trapped in a swamp and their view blocked by tall reeds, give up on ever reaching open water, not realizing that it is only a few yards away. The happiness curve plays its own version of that wicked trick. In a manner of speaking, the bend in the river hides itself, lurking out of view just when we would most benefit from a glimpse of it.

Cole, in Manhood, seems to make the same point. From our point of view, the calm of the ocean, not far away, is visible through a gap in the crags; but the worried Voyager, looking heavenward and surrounded by high rocks, does not perceive it.

* * *

And what of The Voyage of Life’s missing fifth painting?

In 1840, Cole, looking past Manhood’s rapids, saw the still waters of impending death. In Old Age the boat is becalmed, progress has subsided, and the future lies not in this world but the next. Cole had every reason to see the period after midlife that way. In his day, the average American twenty-year-old could expect to live to the age of only about sixty; and, of course, high childhood mortality meant that large numbers of people never even made it to adulthood. Cole himself died at the age of forty-seven. From where he sat, not much lay beyond Manhood except death. He could not have foreseen a world of much longer, healthier lives: a world in which the Voyager enjoys a decade or two (or three) of vitality and improving happiness before death finds him—the scene Cole didn’t paint.

Today, of course, we live in that world, at least if we are fortunate enough to be denizens of an advanced country with good health care and high incomes. Today’s average twenty-year-old American can expect to live to about the age of eighty. In theory, we should be able to see what Cole could not. Oddly, however, we don’t. Those who feel trapped and squeezed between the pincers of Schwandt’s narrowing expectations gap make a forecasting error that perversely mirror-images the forecasting error of youth. Where the twenty-year-old was too optimistic, the fifty-year-old is too pessimistic. That is part of what can make the middle years such a slog: the hard knocks of repeated disappointment lead us to make the biggest forecasting error of all.

Fortunately, the depressive realism of middle age turns out to be … well, unrealistic. Life gets better. Much better.