Chapter 1

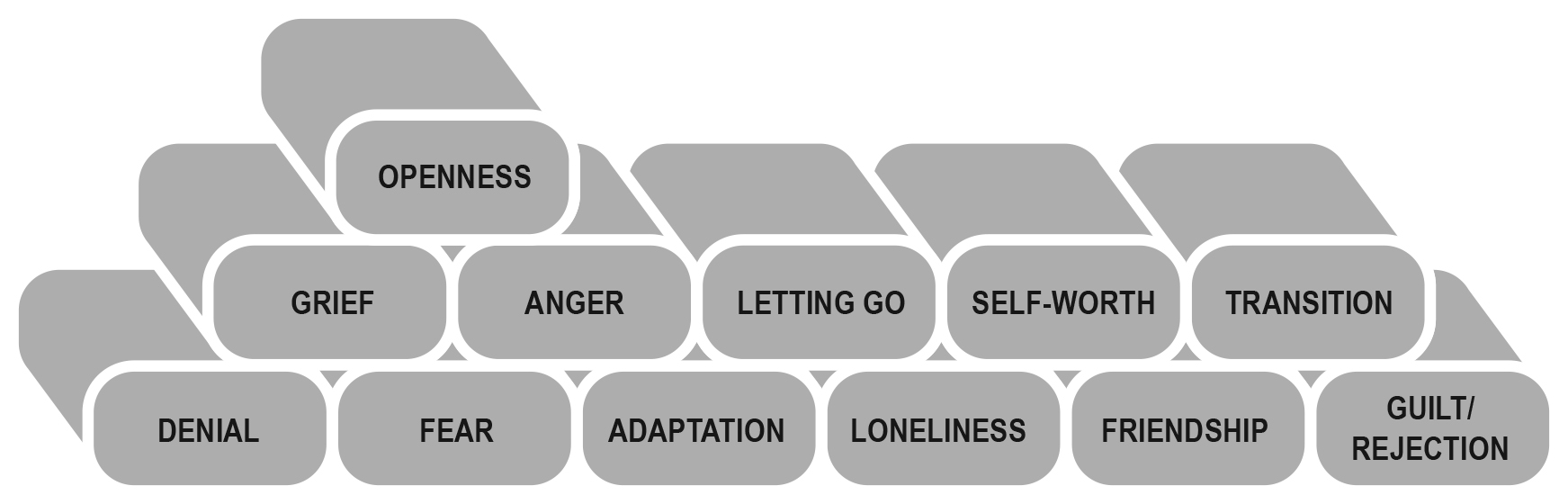

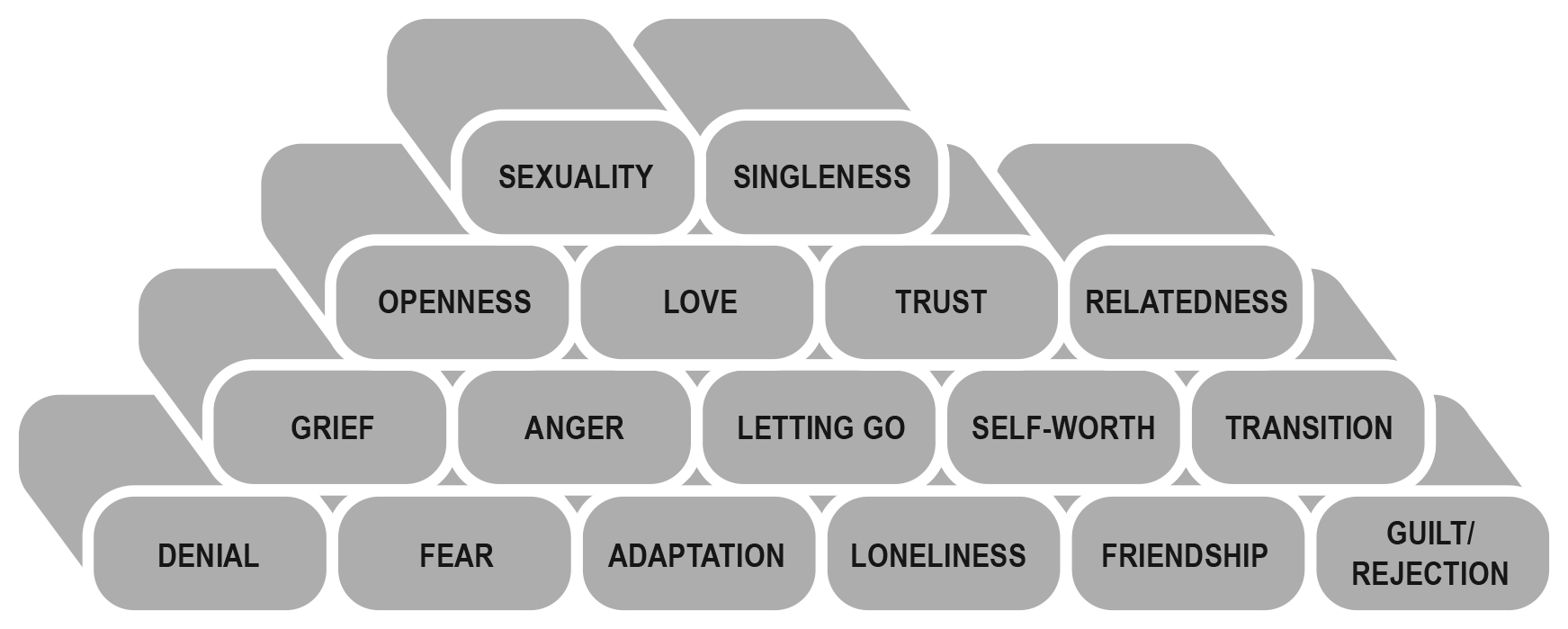

The Rebuilding Blocks

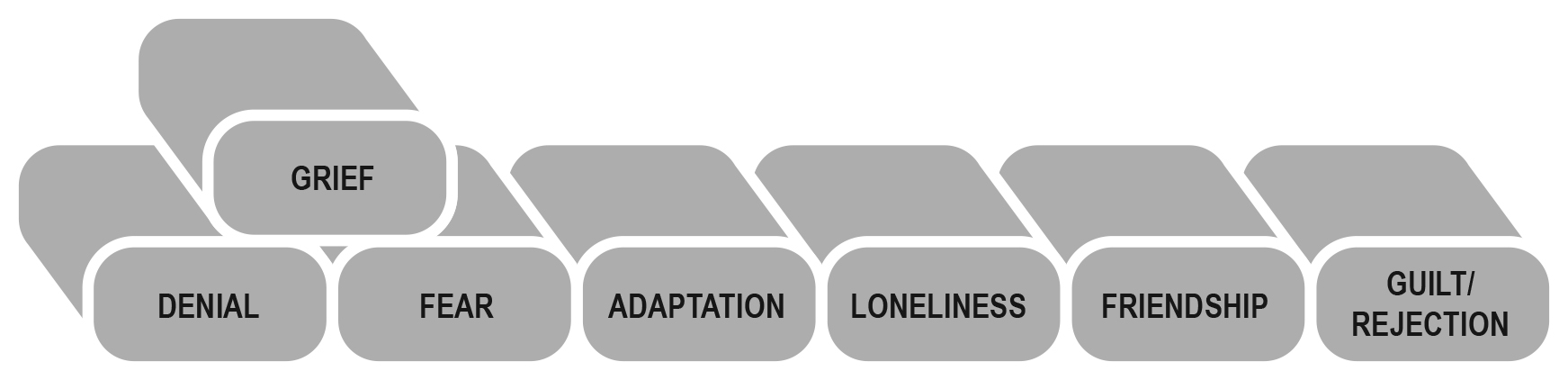

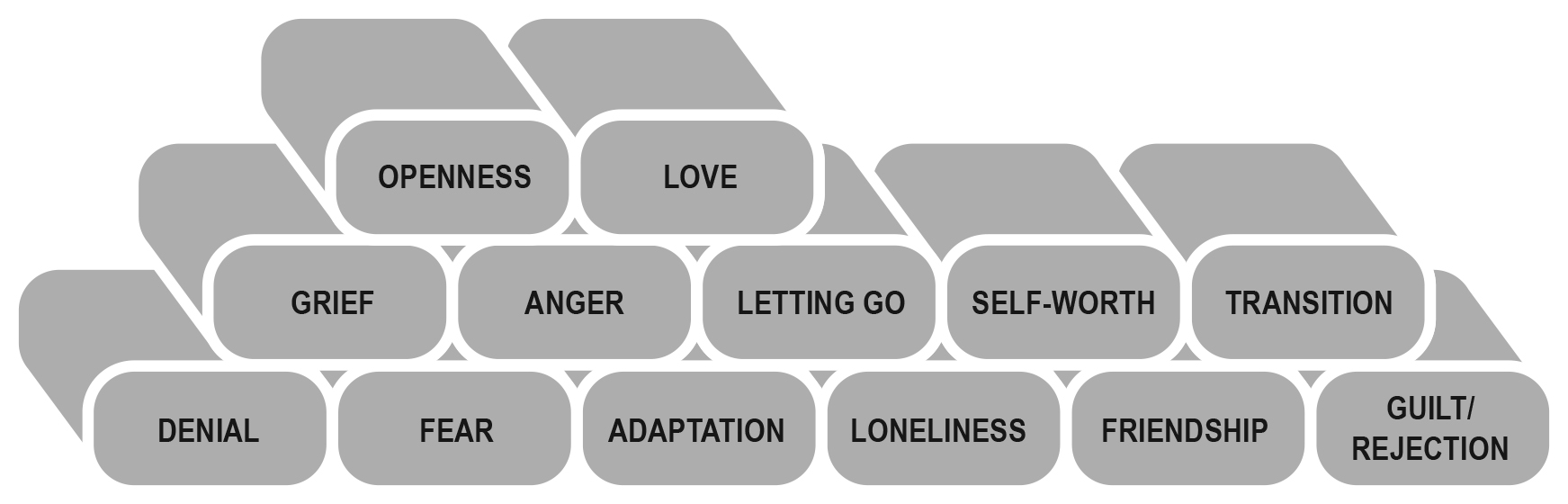

You are probably experiencing the painful feelings that come when a love relationship ends. There is a proven nineteen-step process of adjustment to the loss of a love. This chapter provides an overview and introduction to the rebuilding blocks that form that process.

Are you hurting? If you have recently ended a love relationship, you are. Those who appear not to hurt when their love relationships end have either already worked through a lot of hurt or have yet to feel the pain. So go ahead, acknowledge that you’re hurt. It’s natural, expected, healthy, even okay to hurt. Pain is nature’s way of telling us that something in us needs to be healed, so let’s get on with the healing.

Can we help? We think so. We can share with you some of the learning that takes place in the divorce recovery seminars Bruce Fisher conducted for over twenty-five years. The growth that takes place in people during a ten-week seminar is remarkable. Maybe by sharing with you some of these ideas and some of the feedback we’ve received from hundreds of thousands of readers of earlier editions of this book, we can help you learn how to get through the hurt also.

There is an adjustment process after a divorce—with a beginning, an end, and specific steps of learning along the way. While you’re feeling some of the pain, you’re more anxious to learn how to be healed. If you are like most of us, you probably have had some destructive patterns of behavior for years—maybe since your childhood. Change is hard work. While you were in a love relationship, you might have been comfortable enough that you felt no need to change. But now there is that pain. What do you do? Well, you can use the pain as motivation to learn and to grow. It’s not easy. But you can.

The steps of the adjustment process are arranged into a pyramid of “rebuilding blocks” to symbolize a mountain. Rebuilding means climbing that mountain, and for most of us, it’s a difficult journey. Some people don’t have the strength and stamina to make it to the top; they stop off somewhere on the trail. Some of us are seduced into another important love relationship before learning all that we can from the pain. They, too, drop out before reaching the top, and they miss the magnificent view of life that comes from climbing the mountain. Some withdraw into the shelter of a cave, in their own little worlds, and watch the procession go by—another group that never reaches the top. And, sadly, there are a few who choose self-destruction, jumping off the first cliff that looms along the trail.

Let us assure you that the climb is worth it! The rewards at the top make the tough climb worthwhile.

How long does it take to climb the mountain? Studies with the Fisher Divorce Adjustment Scale indicate that, on average, it takes about a year to get up above the tree line (past the really painful, negative stages of the climb), longer to reach the top. Some will make it in less time, others in more. Some research suggests that a few in our climbing party will need as long as three to five years. Don’t let that discourage you. Finishing the climb is what counts, not how long it takes. Just remember that you climb at your own rate, and don’t get rattled if some pass you along the way. Like life itself, the process of climbing and growing is the source of your greatest benefits!

We’ve learned a great deal about what you’re going through by listening to people in the seminars and by reading hundreds of letters from readers. People sometimes ask, “Were you eavesdropping when my ex and I were talking last week? How did you know what we were saying?” Well, although each of us is an individual with unique experiences, there are similar patterns that all of us go through while ending a love relationship. When we talk about “patterns,” you will likely find that it will be more or less what you’re experiencing.

These patterns are similar not only for the ending of a love relationship, but for any ending crisis that comes along in your life. Frank, a seminar participant, reports that he followed the same patterns when he left the priesthood of the Catholic Church. Nancy found the same patterns when she was fired from her job, Betty when she was widowed. Maybe one of the most important personal skills we can develop is how to adjust to a crisis. There will probably be more crises in our lives, and learning to shorten the pain time will be a highly valuable learning experience.

In this chapter, we’ll briefly describe the trail that we will be taking up the mountain. In the following chapters, we will get on with the emotional learning of actually “climbing” the mountain. We suggest that you start keeping a journal right now, to make the climb more meaningful. After the journey is over, you can reread your journal to gain a better perspective on your changes and growth during the climb. (More about journals at the end of this chapter.)

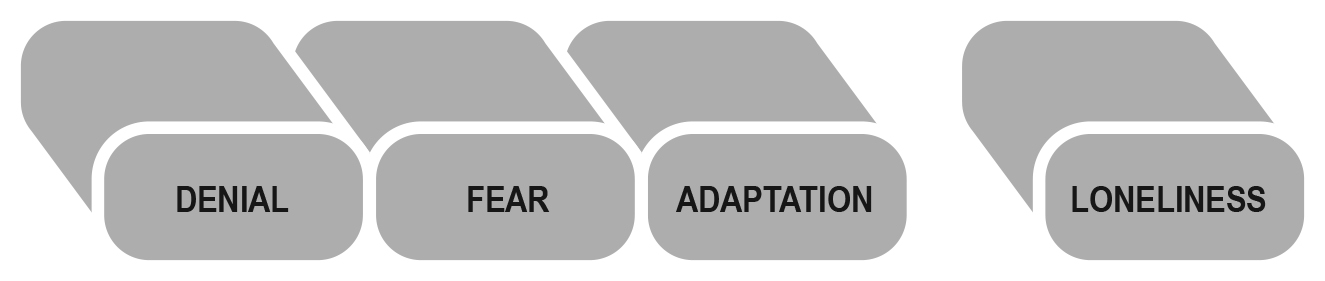

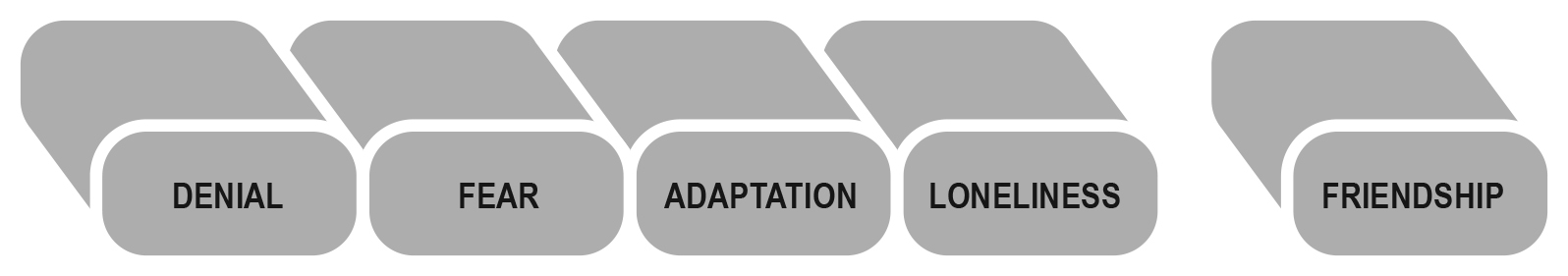

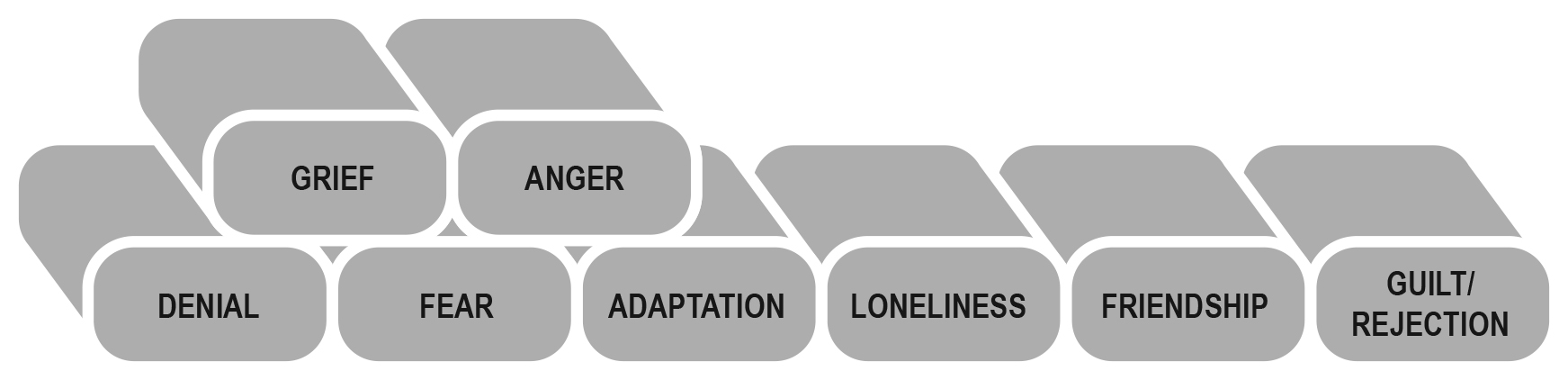

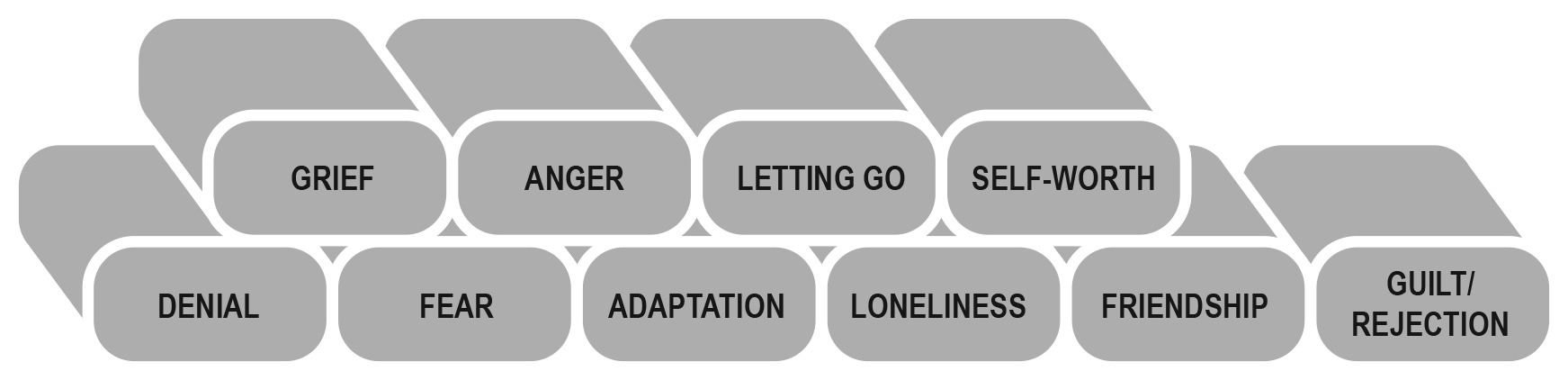

The rebuilding blocks model graphically shows nineteen specific feelings and attitudes, arranged in the form of a pyramid to symbolize the mountain that must be climbed. The adjustment process can be as difficult a journey as climbing a mountain. At first, the task is overwhelming. Where to start? How do you climb? How about a guide and a map to help us climb this difficult mountain? That’s what the rebuilding blocks are—a guide and a map prepared by others who have already traveled the trail. As you climb, you’ll discover that tremendous personal growth is possible, despite the emotional trauma you’ve experienced from the ending of your love relationship.

In the first edition of this book, published in 1981, Bruce described just fifteen rebuilding blocks. His work since then, with thousands of people who’ve gone through the divorce process, has led to the addition of four new blocks and some changes in the original fifteen. He was grateful to those whose lives touched his, through this book and through the classes. Much has been learned from them, and we’ll be sharing their experiences with you in these pages.

Throughout the book, you will find specific ways of dealing with each rebuilding block to prevent it from becoming a stumbling block. (You have probably already stumbled enough!) People often report that they can immediately identify their blocks that need work. Others are unable to identify a problem block because they have effectively buried their feelings and attitudes about it. As a result, at some higher point on the climb, they may discover and explore the rebuilding blocks they overlooked at first. Cathy, a volunteer helper in one of the seminars, suddenly recognized one during an evening class: “I’ve been stuck on the guilt/rejection block all along without realizing it!” The following week she reported considerable progress, thanks to identifying the problem.

The rest of this chapter presents a “pre-journey briefing” on the climb, addressing the blocks as we’ll encounter them on the trail up the mountain. Beginning at the bottom, we find denial and fear, two painful stumbling blocks that come early in the process of adjustment. They can be overwhelming feelings and may make you reluctant to begin the climb.

Denial: “I Can’t Believe This Is Happening to Me”

The good news is, we humans have a wonderful mechanism that allows us to feel only as much pain as we can handle without becoming overwhelmed. Pain that is too great is put into our “denial bag” and held there until we are strong enough to experience and learn from it.

The bad news is, some of us experience so much denial that we are reluctant to attempt recovery—to climb the mountain. There are many reasons for this. Some are unable to access and identify what they are feeling and will have difficulty adjusting to change of any sort. They must learn that “what we can feel, we can heal.” Others have such a low selfconcept that they don’t believe they are capable of climbing the mountain. And some feel so much fear that they are afraid to climb the mountain.

How about you? What feelings are underneath your denial? Nona talked hesitantly about taking the ten-week seminar and was finally able to describe her hesitation: “If I took the divorce seminar, it would mean that my marriage is over, and I don’t want to accept that yet.”

Fear: “I Have Lots of It!”

Have you ever been in a winter blizzard? The wind is blowing so hard that it howls. The snow is so thick that you can see only a few feet ahead of you. Unless you have shelter, it feels—and it can be—life threatening. It’s a very fearful experience.

The fears you feel when you first separate are like being in a blizzard. Where do you hide? How do you find your way? You choose not to climb this mountain because, even here at the bottom, you feel overwhelmed. How can you find your way up when you believe the trail will become more blinding, threatening, fearful? You want to hide, find a lap to curl up in, and get away from the fearful storm.

Mary called several times to sign up for the seminar, but each opening night came and went without her. As it turned out, she had been hiding in her empty apartment, venturing out only for an occasional trip to the grocery store when she ran out of food. She wanted to hide from the storm, from her fears. She was overwhelmed with fear; coming to opening night of the divorce class was way too scary for her.

How do you handle your fears? What do you do when you discover your fears have paralyzed you? Can you find the courage to face them so you can get ready to climb the mountain? Each fear you overcome will give you strength and courage to continue your journey through life.

Adaptation: “But It Worked When I Was a Kid!”

Each of us has many healthy parts: inquisitiveness, creativity, nurturance, feelings of self-worth, appropriate anger. During our growing-up years, our healthy parts were not always encouraged by family, school, religious community, or other influences, such as movies, books, and magazines. The result was often stress, trauma, lack of love, and other hindrances to health.

People who are not able to meet their needs for nurturance, attention, and love will find ways to adapt—and not all adaptive behaviors are healthy. Examples of adaptive responses include being overresponsible for others, becoming a perfectionist, trying to always be a people pleaser, or developing an “urge to help.” Unhealthy adaptive behaviors that are too well developed leave you out of balance, and you may try to restore your balance through a relationship with another person.

For example, if I am overresponsible, I may look for an underresponsible love partner. If the person I find is not underresponsible enough, I will train her to be underresponsible! This leads me to “polarize” responsibility: I become more and more overresponsible, the other person becomes more and more underresponsible. This polarization is often fatal to the success of a love relationship and is a special kind of codependency.

Jill stated it clearly: “I have four children—I’m married to the oldest one.” She resents having all of the responsibility, such as keeping track of the bank account and paying all of the bills. Instead of blaming Jack for not being able to balance the account, she needs to understand that the relationship is a system, and as long as she is overresponsible, chances are Jack will be underresponsible.

Adaptive behaviors you learned as a child will not always lead to healthy adult relationships. Does that help you understand why you need to climb this mountain?

The next handful of blocks represent the “divorce pits”—loneliness, loss of friendships, guilt and rejection, grief, anger, and letting go. These blocks involve difficult feelings and pretty tough times. It will take a while to work through them before you start feeling good again.

Loneliness: “I’ve Never Felt So Alone”

When a love relationship ends, the feeling is probably the greatest loneliness you have ever known. Many daily living habits must be altered now that your partner is gone. As a couple, you may have spent time apart before, but your partner was still in the relationship, even when not physically present. When the relationship is ending, your partner is not there at all. Suddenly, you are totally alone.

The thought I’m going to be lonely like this forever is overwhelming. It seems you’re never going to know the companionship of a love relationship again. You may have children living with you and friends and relatives close by, but the loneliness is somehow greater than all of the warm feelings from your loved ones. Will this empty feeling ever go away? Can you ever feel okay about being alone?

John had been doing the bar scene pretty often. He took a look at it and decided, “I’ve been running from and trying to drown my lonely feelings. I think I’ll try sitting home by myself, writing in my journal to see what I can learn about myself.” He was beginning to change feeling lonely into enjoying aloneness.

Friendship: “Where Has Everybody Gone?”

As you’ve discovered, the rebuilding blocks that arise early in the process tend to be quite painful. Because of this, there is a great need for friends to help you face and overcome the emotional pain. Unfortunately, many friends are usually lost as you go through the divorce process, a problem that especially affects those who have already physically separated from a love partner. The problem is made worse by withdrawal from social contacts because of emotional pain and fear of rejection. Divorce is threatening to friends, causing them to feel uncomfortable around the dividing partners.

Betty says that her old gang of couples had a party last weekend, but she and her ex were not invited. “I was so hurt and angry. What did they think—that I was going to seduce one of the husbands or something?” Social relationships may need to be rebuilt around friends who will understand your emotional pain without rejecting you. It is worthwhile to work at retaining some old friends—and at finding new friends to support and listen.

It’s so easy these days to connect with others online that it’s tempting to let your cell phone or tablet or laptop substitute for seeing others face-to-face. The web is a wonderful resource for many things, but we urge you not to let texting or Twitter or Facebook isolate you from in-person contact.

Guilt/Rejection: Dumpers: 1; Dumpees: 0

Have you heard the terms “dumper” and “dumpee” before? No one who has experienced the ending of a love relationship needs definitions for these words. Usually, there is one person who is more responsible for deciding to end the love relationship; that person becomes the dumper. The more reluctant partner is the dumpee. Most dumpers feel guilty for hurting the former loved one. Dumpees find it tough to acknowledge being rejected.

The adjustment process is different for the dumper and the dumpee, since the dumper’s behavior is largely governed by feelings of guilt and the dumpee’s by rejection. Until our seminar discussion of this topic, Dick had maintained that his relationship ended mutually. He went home thinking about it and finally admitted to himself that he was a dumpee. At first, he became really angry. Then he began to acknowledge his feelings of rejection and recognized that he had to deal with them before he could continue the climb.

Grief: “There’s This Terrible Feeling of Loss”

Grieving is an important part of the recovery process. Whenever we suffer the loss of love, the death of a relationship, the death of a loved one, or the loss of a home, we must grieve that loss. Indeed, the divorce process has been described by some as largely a grief process. Grief combines overwhelming sadness with a feeling of despair. It drains us of energy by leading us to believe we are helpless, powerless to change our lives. Grief is a crucial rebuilding block.

One of the symptoms of grief is loss of body weight, although a few people do gain weight during periods of grief. It wasn’t surprising to hear Brenda tell Heather, “I need to lose weight—guess I’ll end another love relationship!”

Anger: “Damn the S.O.B.!”

It is difficult to understand the intensity of the anger felt at this time unless one has been through divorce. Here’s a true story published in the Des Moines Register that tends to draw a different response from divorced and married people: While driving by the park, a female dumpee saw her male dumper lying on a blanket with his new girlfriend. She drove into the park and ran over her former spouse and his girlfriend with her car! (Fortunately, the injuries were not serious; it was a small car.) Divorced people respond by exclaiming, “Right on! Did she back over them again?” Married people, not understanding the divorce anger, will gasp, “Ugh! How terrible!”

Most divorced people were not aware that they could be capable of such rage because they had never been this angry before. This special kind of rage is specifically aimed toward the ex–love partner, and—handled properly—it can be really helpful to your recovery, since it helps you gain some needed emotional distance from your ex.

Letting Go: Disentangling Is Hard to Do

It’s tough to let go of the strong emotional ties that remain from the dissolved love union. Nevertheless, it is important to stop investing emotionally in the dead relationship.

Stella came to take the seminar about four years after her separation and divorce. She was still wearing her wedding ring! To invest in a dead relationship, an emotional corpse, is to make an investment with no chance of return. You need instead to begin investing in productive personal growth, which will help you in working your way through the divorce process.

Self-Worth: “Maybe I’m Not So Bad After All!”

Feelings of self-worth and self-esteem greatly influence behavior. Low self-esteem and a search for a stronger identity are major causes of divorce. Divorce, in turn, causes lowered self-esteem and loss of identity. For many people, self-concept is lowest when they end the love relationship. They have invested so much of themselves in the love relationship that when it ends, their feelings of self-worth and self-esteem are devastated.

“I feel so worthless, I can’t even get out of bed this morning,” Jane wrote in her journal. “I know of no reason for doing anything today. I just want to be little and stay in bed until I can find a reason why I should get up. No one will even miss me, so what’s the use of getting up?”

As you improve your feelings of self-worth, you’re able to step out of the divorce pits and start feeling better about yourself. With improved self-worth also comes the courage you’ll need to face the journey into yourself that is coming up.

Transition: “I’m Waking Up and Putting Away My Leftovers”

You want to understand why your relationship ended. Maybe you need to perform an “autopsy” on your dead relationship. If you can figure out why it ended, you can work on changes that will allow you to create and build different relationships in the future.

At the transition stage of the climb, you’ll begin to realize the influences from your family of origin. You’ll discover that you very likely married someone like the parent you never made peace with and that whatever growing-up tasks you didn’t finish in childhood, you’re trying to work out in your adult relationships.

You may decide that you’re tired of all the “shoulds” you’ve always followed and instead want to make your own choices about how you’ll live your life. That may begin a process of rebellion, breaking out of your “shell.”

Any stumbling block that is not resolved can result in the ending of your primary love relationship.

It’s time to take out your trash, to dump the leftovers that remain from your past and your previous love relationship and your earlier years. You thought you had left these behind; but when you begin another relationship, you find they’re still there. As Ken said during one seminar, “Those damn neuroses follow me everywhere!”

Transition represents a period of transformation as you learn new ways of relating to others. It is the beginning of becoming free to be yourself.

The next four blocks are hard work, but highly satisfying, as you face yourself, learn about who you really are, and rebuild your foundation for healthy relationships. Openness, love, and trust will take you on a journey into yourself. Relatedness will ease you back into intimate contact with others.

Openness: “I’ve Been Hiding Behind a Mask”

A mask is a feeling or image that you project, trying to make others believe that is who you are. But it keeps people from knowing who you really are, and it sometimes even keeps you from knowing yourself. Bruce remembered a childhood neighbor who always had a smiling face: “When I became older, I discovered the smiling face covered up a mountain of angry feelings inside the person.”

Many of us are afraid to take off our masks because we believe that others won’t like the real person underneath. But when we do take off the mask, we often experience more closeness and intimacy with friends and loved ones than we believed was possible.

Jane confided to the class that she was tired of always wearing a Barbie-doll happy face. “I would just like to let people know what I am really feeling instead of always having to appear to be happy and joyful.” Her mask was becoming heavy, which indicated she might be ready to take it off.

Love: “Could Somebody Really Care for Me?”

The typical divorced person says, “I thought I knew what love was, but I guess I was wrong.” Ending a love relationship should encourage one to reexamine what love is. A feeling of being unlovable may be present at this stage. Here’s how Leonard put it: “Not only do I feel unlovable now, but I’m afraid I never will be lovable!” This fear can be overwhelming.

Christians are taught to “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” But what happens if you don’t love yourself? Many of us place the center of our love in another person rather than in ourselves. When divorce comes, the center of our love is removed, adding to the trauma of loss. An important element in the rebuilding process is learning to love yourself. If you don’t love yourself—accepting yourself for who you are, “warts and all”—how can you expect anybody else to love you?

Trust: “My Love Wound Is Beginning to Heal”

Located in the center of the pyramid, the trust rebuilding block symbolizes the fact that the basic level of trust, within yourself, is the center of the whole adjustment process. Divorced people frequently point their fingers and say they cannot trust anyone of the opposite sex. There is an old cliché that’s very fitting here: when you point a finger at something, there are three fingers pointing back to you. When divorced people say they don’t trust the opposite sex, they are saying more about themselves than about the opposite sex.

The typical divorced person has a painful love wound resulting from the ending of the love relationship, a love wound that prevents him or her from loving another. It takes a good deal of time to be able to risk being hurt and to become emotionally close again. Incidentally, keeping that distance can be hazardous too! Lois says that when she returned home from her first date, there was a mark on the side of her body caused by the door handle on the car—she was attempting to get as far away from the man as possible!

Relatedness: “Growing Relationships Help Me Rebuild”

Often after a love relationship has ended, one finds another relationship—one that appears to have everything the previous union lacked. The thoughts go something like this: I believe I’ve found the one and only with whom I will live forever. This new relationship appears to solve all of my problems, so I’ll hold on to it very tightly. I believe this new partner is what’s making me happy.

This person needs to realize that what feels so good is that she is becoming who she would like to be. She needs to take back her own power and take responsibility for the good things she is feeling.

The new relationship after a breakup is often called a “rebound” relationship, a label that is partly true. When this relationship ends, it is often more painful than when the primary love relationship ended. One symptom of that pain: about 20 percent of the people who sign up for the divorce seminar don’t enroll after their marriages end; they enroll after their rebound relationships end.

You may not be quite ready to think about the next block just yet. But it’s time.

Sexuality: “I’m Interested, but I’m Scared”

What do you think of when the word sex is mentioned? Most of us tend to react emotionally and irrationally. Our society overemphasizes and glamorizes sex. Married couples often imagine divorced people as oversexed and free to “romp and play in the meadows of sexuality.” In reality, single people often find the hassles of sexuality among the most trying issues in the divorce process.

A sexual partner was available in the love relationship. Even though the partner is gone, sexual needs go on. In fact, at some points in the divorce process, the sex drive is even greater than before. Yet most people are more or less terrified by the thought of dating—feeling like teenagers again—especially when they sense that somebody has changed the rules since they last dated. Many feel old, unattractive, unsure of themselves, and fearful of awkwardness. And for many, moral values overrule their sexual desires. Some have parents who tell them what they should do and their own teenagers who delight in parenting them. (“Be sure to get home early, Mom.”) Thus, for many, dating is confusing and uncertain. No wonder sexual hang-ups are so common!

As we near the top of our climb, the remaining blocks offer comfort and a feeling of accomplishment for the work you’ve done to get this far: singleness, purpose, and freedom. Here at last is a chance to sit down and enjoy the view from the mountaintop!

Singleness: “You Mean It’s Okay?”

People who went directly from their parental homes into their marital homes without experiencing singleness often missed this important growth period entirely. For some, even the college years may have been supervised by “parental” figures and rules.

Regardless of your previous experience, however, a period of singleness—growth as an independent person—will be valuable now. Such an adjustment to the ending of a love relationship will allow you to really let go of the past, to learn to be whole and complete within yourself, and to invest in yourself. Singleness is not only okay, it is necessary!

Joan was elated after a seminar session on singleness: “I’m enjoying being single so much that I felt I must be abnormal. You help me feel normal being happy as a single person. Thanks.”

Purpose: “I Have Goals for the Future Now”

Do you have a sense of how long you are going to live? Bruce was very surprised during his divorce when he realized that, at age forty, he might be only halfway through his life. If you have many years yet to live, what are your goals? What do you plan to do with yourself after you have adjusted to the ending of your love relationship?

It is helpful to make a “lifeline” to take a look at the patterns in your life and at the potential things you might accomplish during the rest of your life. Planning helps bring the future into the present.

Freedom: From Chrysalis to Butterfly

At last, the top of the mountain!

The final stage has two dimensions. The first is freedom of choice. When you have worked through all of the rebuilding blocks that have been stumbling blocks in the past, you’re free and ready to enter into another relationship. You can make it more productive and meaningful than your past love relationships. You are free to choose happiness as a single person or in another love relationship.

There is another dimension of freedom: the freedom to be yourself.

Many of us carry around a burden of unmet needs, needs that may control us and not allow us freedom to be the persons we want to be. As we unload this burden and learn to meet needs that were formerly not met, we become free to be ourselves. This may be the most important freedom.

Looking Backward

We have now looked at the process of adjustment as it relates to ending a love relationship. While climbing the mountain, one occasionally slips back to a rebuilding block that may have been dealt with before. The blocks are listed here from one to nineteen, but you won’t necessarily encounter and deal with them in that order. In fact, you’re likely to be working on all of them together. And a big setback, such as court litigation or the ending of another love relationship, may result in a backward slide some distance down the mountain.

Reconnecting with Your Faith

Some people ask how religion relates to the rebuilding blocks. Many people working through divorce find it difficult to continue their affiliation with the religious community they were part of while married, for several reasons. Some faith groups still look upon divorce as a sin or, at best, a “falling from grace.” Many people feel guilty within themselves, even if their faith doesn’t condemn them. (It is worth noting that in 2016 Pope Francis offered a ray of hope to divorced Roman Catholics: without changing church law, he noted that divorced people are not automatically excommunicated, and should be met with an attitude of welcome in their parishes.)

Many churches, temples, mosques, and synagogues are very family-oriented, and single parents and children of divorced people may be made to feel as if they don’t belong. Many people become distant from their faith community since they are unable to find comfort and understanding as they go through the divorce process. This distance leaves them with more loneliness and rejection.

There are, happily, many congregations that are actively concerned for the needs of people in the divorce process. If yours does not have such a program, we urge you to express your needs. Let the leaders know if you feel rejected and lonely. Organize a singles group, talk to an adult class, or ask how you can help to educate others about the needs of people who are ending their love relationships.

The way each of us lives reflects our faith, and our faith is a very strong influence on our well-being. Bruce liked to put it this way: “God wants us to develop and grow to our fullest potential.” And that’s what the rebuilding blocks are all about—growing to our fullest potential. Learning to adjust to a crisis is a spiritual process. The quality of our relationships with the people around us and the amount of love, concern, and caring we’re able to show others are good indications of our relationship with God.

Children Must Rebuild Too

“What about the children?” Many people ask about how the rebuilding blocks relate to children. The process of adjustment for kids is very similar to that for adults. The rebuilding blocks apply to the children (as they may to other relatives, such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, and close friends). Many parents get so involved in trying to help their kids work through the adjustment process that they neglect to meet their own needs.

If you’re a parent who is embarking on the rebuilding journey, we recommend that you learn to take care of yourself and work through the adjustment process. You will find that your children will tend to adjust more easily as a result. The nicest thing you can do for your kids is get your own act together. Kids tend to get hung up on the same rebuilding blocks as their parents, so by making progress for yourself, you will be helping your children, too.

In our discussion of each rebuilding block in the chapters to come, we will take up the implications of that stage for the kids. And appendix A concentrates specifically on the process as it relates to children should you wish to develop a more structured approach to helping your children adjust to the divorce.

Homework: Learning by Doing

Millions of people read self-help books looking for answers to life and relationship problems. They learn the vocabulary and gain awareness, but they don’t necessarily learn from the experience at a deep emotional level. Emotional learning includes those experiences that register in your feelings, such as: mothers are usually comforting; certain kinds of behavior will bring punishment; ending a love relationship is painful. What we learn emotionally affects our behavior a great deal, and much of the learning we have to do to adjust to a crisis is emotional relearning.

Some things you believed all of your life may not be true and will have to be relearned. But intellectual learning—thoughts, facts, and ideas—is of value only when you also learn the emotional lessons that let it all make sense in your life. Because emotional learning is so important, we have included in this book exercises to help you relearn emotionally. Many chapters have specific exercises for you to do before continuing your climb up the mountain.

Here’s your first set of homework exercises to get you started:

1. Keep a journal or a diary in which you write down your feelings. Use your tablet, a laptop, or a small notebook—whatever fits your personal style. You might journal daily, weekly, or whenever it fits your schedule. Start a lot of the sentences in the journal with “I feel”—that should help you concentrate more on feelings. Keeping a journal will not only be an emotional learning experience that will enhance your personal growth, but it will also provide a yardstick to measure your personal growth. People often come back months later to read what they wrote and are amazed at the changes they have been able to make. Every report we’ve heard from those who have kept a journal has described it as a worthwhile experience. We suggest you start writing the journal as soon as you finish reading this chapter. You may want to write in your journal after reading each chapter, or perhaps once a week, or on some other regular schedule. But “regular” or not, do make this a part of your rebuilding process.

2. Find a person you trust and can ask for help, and learn to ask. Call someone you would like to get to know better and start building a friendship. Use any reason you need to get started. Tell the person about this homework assignment if you like. You’re learning to build a support system of friends. Make that connection when you’re still feeling somewhat secure, so that when you are down in the pits (it’s tough to reach out when you’re down there!), you will know you have at least one friend who can throw you an emotional lifeline.

3. Build a support group for yourself. Because a support system is so important, this is a key part of your first homework assignment. We suggest you find one or more friends, preferably of both genders, and discuss with them those rebuilding blocks with which you’re having difficulty. This sharing may be easier for you with people who have gone or are going through the divorce process themselves because many married people may have difficulty relating to your present feelings and attitudes. Most important, however, is your trust in these people.

If you choose to form a discussion group of supportive friends, you may find this book a helpful guide. We do caution you to be aware that not all “support groups” are supportive. Choose carefully the others with whom you work through this process. They should be as committed as you are to a positive growth experience and willing to maintain confidentiality of personal information.

4. Answer the checklist questions. At the end of each chapter, you’ll find a series of statements, most of them adapted from the Fisher Divorce Adjustment Scale, which we have included as checklists for you (the complete version of the scale is available at http://www.rebuilding.org/assessment). Take the time to answer them, and let your responses help you decide how ready you are to proceed to the next rebuilding block.

How Are You Doing?

Here is the first checklist to respond to before you proceed to the next chapter. Assess your response to each question as “satisfactory,” “needs improvement,” or “unsatisfactory.”

- I have identified the rebuilding blocks that I need to work on.

- I understand the adjustment process.

- I want to begin working through the adjustment process.

- I want to use the pain of this crisis to learn about myself.

- I want to use the pain of this crisis as motivation to experience personal growth.

- If I am reluctant to grow, I will try to understand what feelings are keeping me from growing.

- I will keep my thoughts and feelings open to discover any rebuilding blocks that I may be stuck on at the present time.

- I have hope and faith that I can rebuild from this crisis and transform it into a creative learning experience.

- I have discussed the rebuilding blocks model of adjustment with friends in order to better understand where I am in the process.

- I am committed to understanding some of the reasons why my relationship ended.

- If I have children of any age, I will attempt to help them work through their adjustment process.

How to Use this Book

On your own. Most readers of Rebuilding are recently divorced individuals who are reading this book on their own. If that description fits you, we suggest you start at the beginning and take it one chapter at a time. Do each chapter’s homework before going on to the next chapter. The chapters are arranged in the approximate order most people experience the rebuilding blocks, although you may find that your life doesn’t follow the sequence exactly!

On the other hand, we have found that many readers want to devour the whole book first, then go back and work their way through the stages, doing all of the homework then. Whichever approach you choose, we suggest you use a highlighter as you read the book in order to better understand the information. Some readers have found it helpful to use a different-colored highlighter each time they read the book, because each time you read it, you will find new and different concepts that you missed before. You hear only what you are ready to hear, depending upon where you are in your personal growth process.

There are many different reactions from individuals who read this book. Some readers are overwhelmed with some of the information. You may, for example, realize you left your relationship too soon and need to go back and work on some of the unfinished business with your love partner. One seminar participant, George, reported that after he had read the first chapter, he experienced so much anger that he threw the book against the wall as hard as he could!

In a group. Even better than reading the book on your own is to form a small group to discuss a chapter per week together. It takes a minimum of leadership to do this, and you will be pleased to discover how much support you get and how much more you learn from the book by discussing it with others.

In fact, experience and research have shown that the most personal growth and transformation comes in a group setting, including but not limited to that offered by the ten-week Fisher divorce recovery seminar (see http://www.rebuilding.org for information on the Fisher seminar). Most people are amazed at the transformation that takes place throughout the course of a group recovery program, where participants are guided through taking control of their lives and learning to make “loving choices” in the way they live. When you’re putting your life back together after the ending of a love relationship, you may find this approach even more helpful than individual therapy, so check out what’s available in your local area.

A note of caution. It is rewarding to see that many religious and community organizations have developed programs for divorce recovery. In some such programs, however, guiding texts like this one are accompanied by an “expert” lecture each week on a related topic. With this method, you must adjust not only to your crisis, but also to a new viewpoint each week. Instead of giving you an opportunity for active discussion and learning from your peers—a “laboratory” in how to take control of your life—the lecture approach keeps you listening passively. We therefore endorse a participation-centered program over a lecture-based approach, so that group members can bond and connect with one another in a meaningful way.

Don’t get us wrong here. There is nothing wrong with gaining lots of information about divorce. There are many excellent books—you’ll find a list of some of our favorite resources at the end of this book—and we encourage you to read them and broaden your knowledge of the complexities of the process. But information alone will just put a Band-Aid on your pain; it doesn’t allow you to really heal and transform your life.

We don’t claim to have all the answers, but we do know that the program described in this book works. It has been successful for hundreds of thousands of individuals going through the divorce process, and it can help you deal effectively with your crisis and take control of your life. We believe you’ll find in these pages strong practical support for your desire to learn, to grow, to heal, to become more nearly the person you would like to be. We wish you every success in climbing the mountain!