In this chapter, you’ll explore the ways in which mark making is natural to humans, but also how it is natural for humans to respond to marks once they’re made. We have an innate urge to make our marks, and we also have a brilliant capacity for making sense of marks made, by perceiving and forming ideas about them. We have experiences, we make marks in response to them, and then we decide what the marks mean. Being intuitive allows us to do more than just rationally identify drawn marks: “This one is straight; that one is curly.” We can emotionally respond to them: “This one is making me feel cautious; that one is making me feel excited.”

Finding meaning and expression in drawn lines and shapes is an artistic and intuitive process that will help you develop a visual-intuitive language that is your very own. This is a building process that is natural but not always cultivated. In our day-to-day lives, we are prepared to give facts and logical answers more than we are asked or expected to provide our own take on things. We are good at offering generalizations that describe our collective, universal meanings, but not as often given the opportunity to zero in on our personal, unconscious meanings. This exercise is a chance to reflect on what things mean to you personally, expanding your process of discovery. In other words, each time you see a line (curvy, straight, looping, zigzag—any kind of line), you’ll be recognizing it as a form of visual expression and communication. You’ll register what a line and its visual expression or character conveys or suggests to you personally. An example of my own is that I was looking at a line recently and noted that it was shaped like a swooping arch that dipped down low and curved, with a loop in it. I said to myself, “That line has such a swooping curve and a big egg-shaped loop in it.” I was already beginning to register an emotional response to the drawing. Then I said to myself, “And it makes me feel seasick! It reminds me of the time I was on a rollercoaster and regretted it because I didn’t enjoy it at all. I felt out of control.” Describing a line by what it feels like and what it reminded me of helps me open my intuitive sensibility. It helps me see how the line talks to me personally. The main emotion I had when viewing this particular line was that of feeling unnecessarily out of control. I reflected a little more and realized that I had learned to accept that there are certain things others may enjoy that I do not; seeing this line and intuiting its meaning helped me revisit a particular concept I had discovered based on an experience from my past.

Developing a perceptual, emotional response to drawing is a way to set about creating your very own visual-intuitive language. The visual part of your language perceives a line and the form it takes. The next time you see a familiar swooping line, you’ll remember that you have seen this shape before. Then you can immediately recognize what it means to you. The intuitive part senses the meaning the line has to offer you according to your own life experiences, thoughts, feelings, and associations. You’ll build your “vocabulary,” making new meanings each time you look at that line or one that is similar to it. Because line-work is so varied, you will never reach a moment when you have gathered all there is to know or feel.

By practicing this method of perceiving lines and shapes as they interact, you will gradually develop intuitive seeing as a second nature. But to get there, you must go through the process and make seeing this way a practice. Then you will slowly build a visual-perceptual language that holds within it an awareness of your responses, personal meanings, and intuitive knowing. The following examples of lines and shapes will help you create that language through experience. If you listen inwardly with each visual presentation of line and form in this exercise, you will deepen your empathic sensing; this will serve you while you’re learning to do intuitive stream drawing readings. This is about seeing differently—with a visual perception that is intuitive in nature. Cultivating this visual skill will support you in living an intuitive life. Developing this visual language is a playful, enjoyable process of discovery, because art is subjective and relative to each of us. Art and a visual comprehension of line, shape, texture, color, and form provides for you a window to your soul. Let yourself journey to the place within you where so much can be discovered.

Now that we’ve experimented with the basics of stream drawing, we can begin to use this carefree drawing technique in a new and purposeful way: intuitive stream drawing readings. Before we do that, though, we’ll take steps toward seeing and understanding, two methods I call “Gaze” and “Trust Your Words.”

Gaze

GazeWhen we look at an object, the impulse is to immediately label it. Gazing is different, in that there is no expectation. A label isn’t necessarily the outcome; labeling is not as important as considering the object with a completely open mind. Gazing means looking in a relaxed and “off-task” way—seeing the image without having to define it correctly or rationally. It allows you to suspend judgment and to accept whatever arises in your conscious mind. Gazing is a way to visually encounter a person, place, or thing while your own truths gradually surface. Feelings and associations may drift in and out while gazing, as well as totally new ideas about the subject you are perceiving.

This is how gazing works: Open your eyes once you’ve stopped drawing. Take a deep breath and gaze at your drawing. Gazing in this context implies looking intently, but with an open mind and heart. Once you become relaxed while gazing and develop a quiet sense of presence, you will open to your empathic, intuitive knowing. While absorbing the image you have made with a sense of gratitude and ease, you will begin to discover a feeling of enchantment so pleasant that you may feel yourself light up from head to toe. Feeling this wonderment is the sign that you are activating your “higher self,” your spirit within. This aspect of self is your total sense of well-being that is a state of being which resides in you perpetually, even if you block or do not recognize it. This aspect of you is already complete, enriched, and open to heartfelt information. Stream drawing and gazing allow you to unblock and feel the deep beauty that is the natural state at the core of your being.

As you practice gazing, take all of the visual imagery you created inward without focusing on anything in particular at first—gazing is about seeing with an expectant openness. Try to be just as aware of what you see in your peripheral vision as what you see at your focal point. Gazing allows for appreciation and an empathic but detached observance. When you gaze, behold the image with an open heart. You may have feelings that are similar to those you felt while creating the stream drawing. Just appreciate the marks you made, allowing thoughts to stream in and back out. As you gaze, notice if you reflexively criticize or label your drawing; let those thoughts flutter away from you like butterflies. Breathe. Do not criticize yourself or listen to your inner chatter at all. Quiet your mind without judging your drawing; instead, gaze at it with real gratitude. These are the marks you made. They are evidence of your free will on planet Earth, evidence of your power to create change on a subtle level.

Trust whatever comes into consciousness while gazing, knowing there is no right or wrong. Allow feelings and meanings to arrive and accept them.

This is how it works: practice trusting what streams in from your unconscious to your conscious mind. This is exciting because you can feel surprised and delighted by what arrives. Ideas seem to stream in from nowhere! Trusting your impressions encourages your mind toward creative possibilities and gives you the opportunity to entertain different perspectives. Free association of thought and feeling is a wild ride, since you do not know where your thoughts will take you.

It is necessary to practice this because we have a tendency to mistrust ourselves. We block or resist our instincts, and judge or examine thoughts before we commit to them with spoken words. We analyze before allowing our intuitive thoughts into an internal belief system. We reflexively label the things we look at (that’s a tree, that’s a shoe, that’s a tiger, etc.), so we are rarely in an intuitive flow while looking at people, places, or things. We are often locked in a logical, rational mind-set. In this intuitive exercise we are going to decide that whatever surfaces in our minds while gazing can be a guide—an intuitive guide, and it does not have to be logical.

You do not have to do away with logic. In fact, you will use some logic while gazing. Naturally, your mind will try to find what is recognizable. You don’t have to fight it; this is part of this process. You may see a line or loop that reminds you of something your mind understands easily, such as a line that looks like a stick or a square shape that reminds you of a table. The point is not to block your rational thoughts or your intuitive ones. Practice not blocking anything that comes to mind. You may look at a line that reminded you of a stick and end up having words surface into your conscious mind that do not seem logically related. It might suddenly remind you of a person you used to know named LeRoy. Why? That’s the fun part. You will use your visual-intuitive language and answers will come via intuitive sensing, just as they often arrive in a logical context.

Trusting your words is easy. You just have to open up to your intuitive intelligence and your emotional, empathic awareness, which is part of your intuitive knowing. It is not only fun, but also a fascinating experience. This method of self-discovery works when you use visual marks to create intuitive, unconscious associations. We each have a history that is unique. We carry within us the information we got from all these life experiences, and we can tap into that information when we respond to images. This inner core is where your intuitive intelligence resides. And the best way to tap into this amazing source and essence of knowledge is to get playful, like a child. Having a playful attitude and disposition is what makes self-discovery so much fun. As a result, your imaginative, creative expressiveness blossoms, heightening your sensitivity.

The “personality” of a line can be seen and felt by the viewer. A line has character in its quality, determined by its attributes, such as its shape, density, length, and angle. The most simple line—for example, a check mark on a grocery list—has an entire universe of personality in it, giving us clues about the mark’s temperament. As we observe a line’s personality, we determine and ascribe meaning to it. Each of us, individually, assigns our own meaning. For example, I may look at a check mark and see a very rigid and energetic shape. It is exacting and positive. It gives me the feeling of “I mean business”—like a person that wastes no time. Someone else may see and feel completely different things when looking at the same mark. It might remind them of a line graph showing how well the stock market is doing (it starts at a low height, plummets down, then quickly rises up very high). We each have our own perceptions, and lines will teach us what they are and what they mean to us personally if we pay attention.

The lines we draw speak to us! In this section, we are going to play, using simple drawings to discover the essence of each line. You will have a chance to frolic with your responses in a lighthearted way, letting your imagination sail. This will help you understand feelings that arise when you stream draw and will be greatly helpful while conducting intuitive stream drawing readings.

Truly, even in a very simple mark, a world of information can be discovered. Just as a single note of music can fill us with emotion or a single scent can immediately elicit a strong memory, lines and marks stimulate our feelings. It is important for us to understand our responses to images, because once we are attuned to our own associations, we respond intuitively, with conscious awareness. Intuitive stream drawing work or other kinds of psychic reading is possible as we build our awareness and an inner structure of consciousness stemming from our own meanings (our own associations and personal unconscious memory based on our unique history), but we have to become sensitive in order to truly value all the information we carry inside us. These exercises were created to help you see how meanings arise from visual clues. Your experience will inform and guide you. Remember, it is not a formula, but a process.

Drawn lines and marks carry a body of content that we each understand in our own way, depending on our perception. We use our five senses to give context, or meaning, to everything we encounter. Art forms such as lines and shapes represent elements from our experiences in the world, either symbolically or literally. It is up to us to understand and comprehend the personal meanings in art forms. To develop a visual-intuitive language, we embark on a journey to discover and know what our own meanings are and how to use them to have a better life.

As we begin our next visual-intuitive adventure, I want to introduce projection, which plays a big part in the process of stream drawing. Projection is a response we send outward to all things in our environment. As we perceive, we project our own ideas about a subject directly onto it. In other words, I project my own experiences on what I perceive around me. I may project outwardly that something is “good” or “bad,” but that doesn’t make it necessarily true—yet it may be true to me. An example of this is that I got a very short haircut and loved it. I was so excited and felt so free. I encountered someone later that day who saw my haircut and instantly assumed my short hair meant that I was unhappy. She projected onto me what it would feel like to her if she resorted to a short haircut. To her it was a sign of depression or of troubling times; possibly she only cut her hair when she felt upset. But for me, it symbolized freedom and artistic expression that took me years to be gutsy enough to demonstrate!

Projection is part of perception for each of us, and being aware of it will help us to look beyond what we currently perceive. While we accept our own truths as they arrive, we also keep an open heart and mind so that we can gain new insights. Reflecting while gazing and trusting the words as they come (meanings we assign to visual stimuli) involves projection. We see images and project our own meaning onto them; it’s a natural reaction and relationship between vision and mental processing. Our memories influence us enormously and quickly offer us input as we form our perceptions of what we see, sending those perceptions outward as projections. At all times we have the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious (or subconscious) working with us, helping us determine what things mean to us. Memories are available for retrieval through the stream of consciousness.

In my first book on intuition, a working journal using forty large image cards, I made the point that imagery can powerfully seize memories from the unconscious mind and project them at faster-than-light speed into our awareness. A single image can suddenly cause us to feel and remember something we forgot we knew. Other sensory exposure besides sight can do this, too, such as music or smelling the scent of something from childhood, like your grandmother’s perfume. Encountering the same scent can take you back decades as it delivers a memory you didn’t realize you had, yet it was there all the time! Experiences bring it all back into conscious recognition.

We know what is on the open sea of the conscious mind, but there is much more under the surface. Interpretations and perceptions stored within the unconscious mind appear in conscious awareness when something triggers a memory. Those memories can be pleasant or unpleasant. But even if an experience is long forgotten, it can be brought back into the arena of the conscious mind, depending on the nature of the experience.

When experiences are unpleasant, we may not remember them for a number of reasons. The preconscious plays the role of the built-in protector, kind of like a mediator between the conscious and unconscious. Certain traumatic experiences sink below our level of consciousness because remembering them would mean experiencing the trauma all over again. Those forgotten memories are still there, streaming deeply through the mental-emotional layer under the threshold of our awareness. The preconscious mind sifts through what we can handle at any given time, and so certain memories may remain submerged in the subconscious while others enter fully into the mind. If repressed memories are too difficult for the ego (our persona, our sense and idea of self that we create in order to survive), then that stream of information will remain in the preconscious mind. We may not have developed the strength to incorporate, process, and cope with the information it holds, especially in the case of trauma or injury.

Psychic acceptance of this material (held back from the ego) is known as ego syntonic condition. Reflection and contemplation, prayer and meditation are a few ways in which the memory content can be brought out. Dreams and activities like expressive mark making and stream drawing are practices that can allow us to bring forward information from our subconscious mind. We need only to open ourselves to the stream of inner-knowing residing within. Through our empathic surrender, hidden and forgotten knowledge may flow, offering information that has the potential to be life-changing.

Activating this enormous stream of memory can feel very good, even when the memories are difficult for us, because our preconscious mind is there, protecting us. When we are ready to accept certain memories, it can be like an epiphany; we realize what caused us to be oriented in a certain way, or what motivated us in certain situations. Sometimes we break through barriers that have held us back in life.

While we stream draw and gaze, trusting our words (as memories and associations we hold), we project those impressions forward. Mark making is an act of will and intent—evidence of our presence and an expression of our gestures. We project further by creating lines and shapes on a previously blank page. Then, we read our own understandings of our drawings, intuiting meaning from the way lines and shapes interact and appear on the paper. As each of us is unique, we will have our own perceptions in addition to agreeing on universal or collective perceptions. For example, we may all agree that the glowing sphere in the night sky is the moon; we all see the moon in the sky. Yet, according to my personal experience, my definition of the moon may include my memory of reading folktales, fairy tales, or myths. So when I see the moon, my personal impressions are at play, whether I’m conscious of them or not. To another person, the moon may suggest space exploration or memories of wanting to be an astronaut. So, even though we collectively agree and recognize the moon, we will each have a unique experience when we look up at the moon. When we honor that stream of consciousness that delivers us these meanings—a source of compassion, information, and intuitive sensing—we connect with others in a more meaningful way as well.

![]()

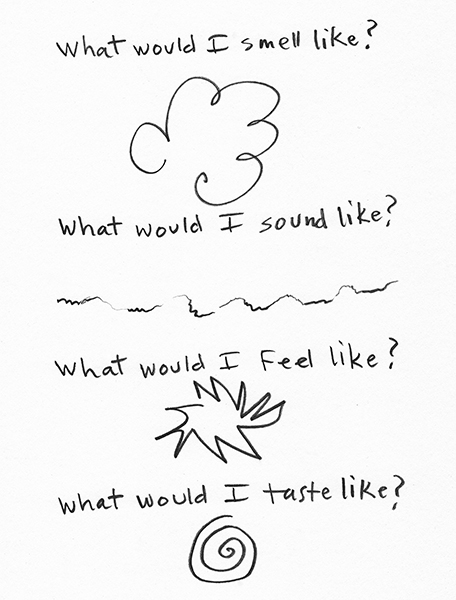

Our senses work together to give us a full range of information about the world around us. To explore that, we’ll practice synthesis of the senses. We can claim our unique perceptions of how drawn lines make us think or feel. Not only will we look at lines, but we’ll see how our unconscious memories and personal library of associations arise when we gaze.

For example, a single arcing line may remind you of a rainbow (the context being that a prism in the sky has this shape). Then your mind may immediately jump to the various content the image of an arc or rainbow has, such as memories of seeing a rainbow with family or friends. Immediate associations loaded with sensory input may add volume to the content as your awareness increases and builds on the original impression. First, you see an arc; then, you imagine a rainbow; then, you taste rainbow sherbet. A simple line shaped like an arc stimulated associations with the sense of sight and taste (seeing the rainbow and then thinking of the flavor of ice cream).

However, a line in the shape of an arc might hold completely different context and content for someone else. Perhaps she sees the arc as a bridge, which might take her back to memories of a bridge she used to cross frequently; she may remember the scent of mossy brook water. To another person, that same arcing line might remind him of a frown painted on a clown in a circus he once saw, bringing up the sounds of circus music and the ringmaster’s voice. And in another person’s mind, the line might produce a thought or feeling that has no rational explanation, where the context is not obviously connected and the content seems illogical.

We may not always be able to explain why images give us certain feelings or why intuitive sensing clues us into things (as in precognition), but we do know it happens. Art often elicits what we can’t explain verbally, and intuitive knowing arrives similarly—seemingly out of nowhere. The important thing is to accept whatever surfaces, whether it is rational or not.

Look at each drawing in Figure 4 and answer the sensory questions.

Sensory Lines.

For this exercise, we will practice being open to context and content. We’ll let imagery awaken our five senses and put a human touch on each line we see. Imagine the lines you see as people, full of personality in their gestures.

While looking at the lines, write down what each type of line makes you feel or think. Do not hesitate or second-guess your associations. Write down whatever comes to you when you see and perceive these lines.

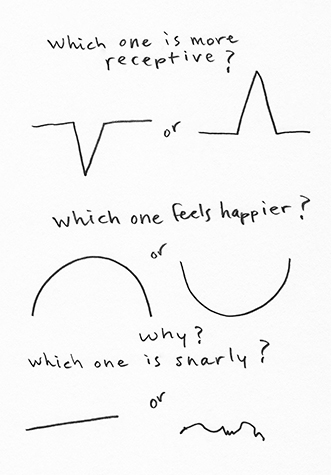

Become aware of your breathing. As you breathe slowly and deeply, gazing, relax into the image before you. Use the gaze technique (your intuitive seeing skill) as you consider the lines and questions in Figure 5. Enjoy the lines for what they are.

Comparing each line, think of their individual characteristics and get into a dialogue with yourself. “One line is like steps, the other is like a slide,” you may say to yourself. Their attributes lead us to further descriptions as we gaze at them. The first question prompts: “Which one is going up?” I may respond without hesitation that the line that resembles a staircase feels as though I am going “up.” The angle of the line beside it, higher on the left and lower on the right end, suggests “down” to me. Those single drawn lines speak volumes. Continue to gaze at the lines and absorb the feelings each one gives you, using your sense of logic to help you connect with them. No answer you give is wrong.

As you gaze at the other line exercises, ask yourself why you have arrived at your answers. Within them is information about how you perceive; your response, whether logical or more intuitive, is the key. The question “Which one is water?” compares a wavy line to a choppy one, shapes jutting up and back down. Logically, we might decide that the wavy line suggests ocean waves or ripples we have seen on the surface of water. Yet the other image could be frozen water, with rigid ice formations. Looking again, we might say that the wavy lines make us feel a particular rhythm and flow that we connect with swimming in the sea. Embrace whatever impressions arise when you gaze at the lines. Remember to play. Imagine these lines as people; build on this by having an inner dialogue about it. Also, remember to ask yourself questions about the lines and what they may mean. Be flexible. Playful questions may help you relate to the lines as people. Think of roles people play in life and apply them to the lines you see. For example, given its visual characteristics, which line seems to project sadness? If so, why? Ask someone else what they see in these lines and have a fun discussion. Comparing and contrasting your impressions and projections can be exciting.

Line drawing comparison, part one.

Now take some time to gaze at the lines in Figure 6 and allow your logic to help you as you accept your response. Then go deeper by asking yourself why and how you arrived at your answers.

Line drawing comparison, part two.

Your thinking may go like mine. For example, the question “Which one is more receptive?” is interesting for me because I perceive the first line on the left as jutting into the ground. To me, it looks like a deep cut into a surface. I could pour something into it if I wanted to. The line makes me feel a kind of receptivity, although it is a non-emotional line for me; I imagine its metallic precision, so I do not feel relaxed gazing at it. I feel a rigidity that I do not associate with the word “receptive.” These lines, if human-like, would be more like robots than actual people, if you ask me. They might be beaky, hard-nosed personalities.

Looking again at the line on the left, I see it is concave (valley) and conveys spacial receptivity; therefore, it is receptive. I can drop or pour something in there. In contrast, the same line inverted the opposite way (on the right) makes me feel like I just encountered a steep hill. I do not perceive this line to be receptive at all. For me, it has a convex (peak), unyielding, industrial feeling. Breathing slowly to really take in this line, I think, maybe it is receptive, but in a way I didn’t realize at first. Gazing for depth of meaning, I find that this convex line may be receptive in its own way. Perhaps it is a radio tower or satellite receiver of some kind, receiving unseen signals. I realize that if I go under it, I could fill that space, too—it looks hollow. Maybe it has a military purpose and is bombproof.

Gaze at the lines in Figure 7 and have fun with them. Read each question and allow your answers to surface. Then, gaze at each line separately to see how you feel. Think about them in terms of their characteristics: as masculine versus feminine, soft or hard, sharp or smooth. Does a line give you a feeling of calm or nervousness? Does one line seem angry? Take your time while you gaze. A line may suggest happiness or sadness, threat or safety, clarity or confusion. It depends how you relate to their expression. Breathe in and register why you have certain perceptions, and connect with your feelings.

As I gaze, my feelings begin to activate. Once I allow myself to go beyond my first responses, my imagination helps me discover my personal viewpoints, logical or not. There are many ways to perceive the lines, so enjoy gazing and contemplating them, discovering your own personal reactions and responses.

Line drawing comparison, part three.

As we discussed at the beginning of this section, lines and all other forms have a context and carry with them a body of content that we understand each in our own way (depending on our perception). In this next image of several lines together (Figure 8), you may find that your response to it is immediate. You may see something whole. It is made of many separate parts, all working together. These simple lines together take on a significant form. The content of the image allows you to describe it as a whole; the context allows you to arrive at the meaning you give it. While these meanings are subjective and personal, they can also be universal. The mind and heart seek and identify their meanings. Notice the image as a whole, then pay attention to each line and notice what they tell you.

Line drawing comparison of many lines together.

Gaze at this group of lines. You have already compared and contrasted sets of two lines—now try this one! This multi-line image offers another way to perceive the personality of a line. When more lines are seen together, arranged as a group, some different kinds of associations may come into play. What do they make as a whole? Are they all alike, or do they vary in expression? Several lines fanned out slightly might remind you of something in particular. Gazing at each line may offer you more insight into the personality of each one. The space between lines, called the negative space, may also hold information. Is one line far apart from another? Does that imply emotional distance? Is another line extremely close? Does that imply physical or emotional attachment of some kind?

Trust your words as you honor any and all associations you have while looking at the image. For example, I see grass blades, but I am also reminded of a lion’s mane. The lines make gestures that remind me of calligraphy, and even sports team logos. I see a y and a v. The two lines in the center seem to me to be like parent and child—they are closer together than the other lines, which sway away from the center.

Shapes evoke emotion and trigger associations out of the unconscious and into our decision making process, the same way lines can. Using the same playful openness you used while gazing at lines, try shapes and lines together. See what arises into your awareness.

Gaze at the shape with a line attached to it in Figure 9 and consider its form. Is it a person at all for you, or something else? Could it be a part of an actual person (such as the head)? What thoughts arise in you when you look at this line? What kind of object does it remind you of?

Trust your words as you gather all of the thoughts and impressions that come to mind while gazing at this. One may seem more prominent than another.

At first I think of a deflating balloon on a string. It gives me a depressed feeling, like a big letdown. Then the next line has the same basic idea, but with a different visual result. Now the line goes up softly to a floating bubble shape. For me, it looks like a balloon that is filled with helium. All is not lost: the party is not over! The impression I get feels much better, a feeling of positivity coming over me.

A line and shape together.

Gazing longer at this line and shape combination makes me want a piece of bubble gum for some reason: my sense of taste was activated when I looked at this, probably by the round shape of the drawing. Blowing pink bubbles reminds me of childhood days and gives me an easygoing feeling. Yet it also awakens this memory: someone had gum but not enough to go around. They wrapped a rock in a gum wrapper, so that when my sister opened it, she had a full-out tantrum. I remember feeling so sorry that my sister got tricked. I wanted her to be treated better but felt helpless, and just stood there chewing my own piece of bubble gum. With this simple shape, I can check in with my unique feelings and memories. They conjure up a lot for me internally.

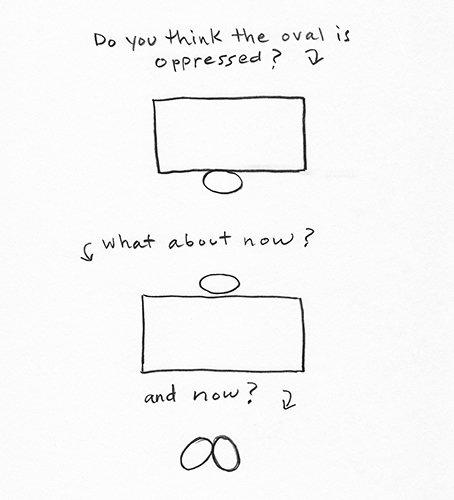

Gaze at the two shapes in Figure 10 and see if you feel something different from the last exercise. How do you react while gazing at the oval shape, compared with the rectangular one above it? What sensations and emotions come to you? Do you feel secure when you confront this shape combination, or wary? What is the dynamic between the two shapes? Do their size differences have a connotation for you? Does bigger mean more powerful? Does smaller mean vulnerable? Gaze at the first combination for a while and see what memories or associations surface for you, then go to the next. Do different feelings arise?

Trust your words as they arrive from within and don’t worry about whether they seems logical or rational. Often the feelings and memories that arise from seeing shapes, lines, color, and texture are connected to certain life experiences that seem unrelated to the shapes themselves. For example, I immediately noticed I was struggling to breathe when I saw the first image of the rectangle on top of the little oval. The weight of it really got me, but if I had not paid attention, I might have not noticed this. Gazing, breathing, and allowing myself to go beyond rational thinking helped me recognize an inner response I had.

The question asks, “Do you think the oval is oppressed?” This is a leading question, one that prompts the response “Yes, the little oval is being overtaken by this enormous rectangle. Help!” Looking again, I feel new fondness for the image. That little oval reminds me of a pure and perfect white stone I found on a beach in Cape Cod. It was smooth and looked like alabaster. Nothing could crush it. I think this little oval is carrying the rectangle, perhaps because the rectangle can’t roll around like the oval can. Or the oval has a job lifting empty cardboard boxes. With this new impression, I feel better and can breathe more easily. Looking at the image below, where the rectangle is beneath the oval, I get all new feelings and ideas. Do you? And the next image of two ovals together, does this image convey an entirely different relationship? Is there a sense of companionship and trust or interdependence and affection? Or something else?

Rectangle and oval comparison.

Gaze now at this triangle shape (Figure 11). The center traingle has a very different expression from the one above it. What is the quality of the line in comparison to the shape above? Imagine this shape in an argument with the shape above it. Who would win and why? Does this triangle remind you of anything? Anyone?

Trust your words as you gaze at this shape. What words can you come up with to describe this triangle?

Triangle comparison.

Gaze at the next triangles. These shapes have a few subtle differences. Concentrate on the small triangle. What happens when you gaze at this one in relation to the larger one? Is there a parental feel to these two triangles due to size differences? Or does it convey something else for you?

Remember the importance of being aware of the content and context. Take the time to notice how small variations communicate meaning to you; this is what helps you develop your visual-intuitive language. The soft-edged triangle may feel very different than the pointed one. When you finish gazing at the first two triangles, look at the two on the bottom. You might respond very quickly to the question asked about those two triangles. Ask yourself why you have the answer you have, and then play with options that might be possible as alternative ways to perceive the two together.

Trust your words as you write down whatever comes, without blocking or censoring yourself.

Let’s put another line and shape together (Figure 12). What kind of relationship do they have? Would they get along like the same things, or have different tastes altogether? What are their similarities and differences? Imagine that they are people. Do you have a pleasing feeling when you see them together, or something else? What do you make of the negative space, or the space between them? What does it convey, if anything? Does the negative space indicate intimacy or alienation? And what kind? Why or why not?

Trust your words as you consider the dynamic between these two shapes, and be playful!

There are some common, universally familiar configurations—often very simple ones—that we recognize immediately. We agree upon the meaning conveyed by the visual suggestion. Without even having time to consciously gaze at the image in Figure 13 (a single shape, a single line, and two short marks) we can see: this is a smiley face!

Line and square shape together.

Gaze at the image at the top of the page in Figure 13. You may have discovered you did not even have to gaze—you immediately saw the circle, line, and marks and knew they were a face, mouth, and eyes. These simple marks most likely instantly registered meaning for you. And all we’ve done is play with a simple circle shape, a simple arc of a line, and two small marks.

Smiley face, frowny face.

The same combination, with only one little change (inverting the arc) really alters the emotional response for me. Now I see a sad face instead of a smiley face.

Next, let’s take the same shape, change the line from an arc to a straight line, and place it in a less logical position, atop the two small marks (see Figure 14), which I’ve moved a little closer to the line. What happens? It may no longer seem like a face, but can you intuit an emotion?