Kingstree to Georgetown to Charleston County

Total mileage: approximately 143 miles.

THIS TOUR CAN BE COMBINED with Tours 1 and 3 for a complete look at the life and escapades of Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox.”

The tour begins at Williamsburg Presbyterian Cemetery, located on S.C. 261 approximately 0.3 mile east of the junction with S.C. 527. This sprawling graveyard is located on both sides of the road. A number of Revolutionary War veterans, including John Witherspoon (whose house is visited later in the tour), are buried here. The earliest graves date to the first half of the eighteenth century, when the cemetery was begun by the congregation of Williamsburg Presbyterian. Organized in 1736, the church was the first of its denomination in the South Carolina back country. The congregation moved to a church in downtown Kingstree in 1890.

From the cemetery, go west on S.C. 261 for 1 mile to the junction with U.S. 52 (Main Street) and S.C. 527 in the heart of Kingstree.

Just east of this intersection is the Williamsburg County Courthouse. On the courthouse grounds stands a monument to the Patriots of Williamsburg County during the Revolutionary War. Virtually every able-bodied Williamsburg man between the ages of fifteen and sixty fought under the command of General Marion for some or all of his two-year partisan campaign to reclaim South Carolina from British control.

The monument honors the sacrifice of local Patriots, who often dressed in nothing more than the skins of the animals they killed for food. They supplemented their diet with fish and locally grown sweet potatoes. To do battle with Tarleton’s troopers and Watson’s Tories, Marion’s followers from Williamsburg used swords fashioned from handsaws and bullets molded from pewter spoons.

Following the war, when Cornwallis was teased about the inability of his troops to subdue Marion in Williamsburg, the British general was quick to reply, “I could not capture web-footed men who could subsist on roots and berries.”

A state historical marker in front of the courthouse notes that this lot was the muster ground of local militia in colonial and Revolutionary War times.

Directly across Main Street from the courthouse is the Williamsburg County Museum, located at the corner of Main and Academy Streets. The museum’s exhibits and displays chronicle the long history of the area, including the period of the American Revolution.

It was here, at the head of Academy Street, that one of Marion’s most trusted lieutenants from Williamsburg, Major John James, intercepted Major James Wemyss and a British column on the night of August 27, 1780. After gaining an accurate count of the enemy party sent to raid the Williamsburg area, James launched a hit-and-run strike and galloped off to inform Marion of the presence of the British force.

Just west of the intersection is a D.A.R. marker in an island in the middle of U.S. 52/S.C. 261. It is located on the exact site where the “King’s Tree” stood for many, many years within a stone’s throw of the Black River. An early explorer notched the white pine with an arrow to reserve its use for naval stores for the king’s navy; it was thus that the tree acquired its name. And in time, the community that evolved here—the oldest inland settlement in South Carolina—took its name from the tree.

From the intersection, proceed south on S.C. 527 for 0.5 mile to Thorntree, a colonial home magnificently restored and maintained by the Williamsburg County Historical Society. Constructed by John Witherspoon in 1749, the frame dwelling is believed to be the oldest house in the Pee Dee area. Admission is free; the house is open by appointment.

Turn around at Thorntree and return to the junction with U.S. 52 and S.C. 261. Turn left on U.S. 52/S.C. 261 and drive 0.9 mile to the Black River, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the Battle of Kingstree.

Major John James’s surveillance of and attack on the British force under Major Wemyss on the night of August 27, 1780, enabled the Swamp Fox to plan his ambitious campaign in the area. Though he was heavily outnumbered at Kingstree, James could not resist the opportunity to inflict damage on Wemyss’s command. After all, Wemyss had paid a destructive visit to this, James’s hometown, several months earlier. His harsh treatment of area Patriots and his destruction of property drew the ire of the people of Williamsburg and made him one of the most hated British officers in South Carolina.

In the attack here at Kingstree, James killed or captured thirty enemy soldiers.

Retrace your route to S.C. 527. Turn left and drive north on S.C. 527 for 8.4 miles to S.R. 45-676. Nearby stands a state historical marker honoring Captain William Henry Mouzon, Sr. To see the grave of the Revolutionary War hero and cartographer, turn right on S.R. 45-696 and go 0.2 mile to the Mouzon family cemetery.

Captain Mouzon (1741–1807), a member of a French Huguenot family that settled in Charleston, was schooled in France and spoke French as fluently as English. A highly respected civil engineer, he moved his family to Williamsburg County prior to the Revolutionary War and worked to bring harmony between Huguenot and Scots-Irish settlers. His efforts reaped handsome rewards for the American cause during the Revolution, as the great majority of Williamsburg residents were united in the cause of independence.

As tensions mounted between the colonies and Great Britain in 1775, Mouzon drew a remarkably accurate map of the Carolinas that he called, fittingly, “An Accurate Map of North Carolina and South Carolina.” This masterpiece was the first map of the two colonies drawn to scale, and it was quickly published in Europe. The Mouzon map remains the basis of all maps of North Carolina and South Carolina produced since that time.

When Francis Marion organized his army in 1780, he named Mouzon one of his four captains. Marion’s brigade had been in action only a month when Captain Mouzon’s military career came to an abrupt end after he was badly wounded at the Battle of Black Mingo Creek. So severe was his wound that he was crippled for life.

The cemetery is located on the edge of Pudding Swamp, so named in the eighteenth century, tradition goes, for a local black man who called at every farmhouse at hog-killing time in hopes of getting some liver pudding. A trail was blazed across the swamp from Kingstree to Camden in the mid-eighteenth century.

Captain Mouzon established his plantation in Pudding Swamp prior to the war. When Tarleton came calling in Williamsburg County on August 6, 1780, he singled out the Mouzon place for the torch. When asked why he burned the plantation, Tarleton noted that not only was Mouzon a leader of local Patriot forces, but he spoke French as well.

Return to S.C. 527. Turn left, drive east for 2.4 miles to S.R. 45-248, turn left again, and proceed 3.4 miles to S.R. 45-44. Follow S.R. 45-44 northeast for 3.1 miles to U.S. 52. Turn left, head north for 2.7 miles to S.R. 45-28, turn right, and drive 0.4 mile east to the junction with S.C. 512 in the community of Cades. Cades was formerly known as Camp Ridge. The Swamp Fox maintained a recuperation camp here during the war.

Drive east on S.C. 512 for 14.2 miles to S.R. 45-39, where a state historical marker calls attention to Indiantown Presbyterian Church and Cemetery, located on the right side of S.C. 512. Organized in 1757, the original church here was burned by British raiders, who branded it a “sedition shop.” It was rebuilt after the war. The existing sanctuary, constructed in 1830, is the third at the site.

Among the Revolutionary War veterans buried in the adjacent cemetery is Major John James, one of Marion’s ablest and most fearless warriors. Born in Ireland in 1732, James came to Williamsburg with his parents when he was less than a year old. His grandfather, also named John James, had served as a captain of dragoons for William of Orange in his famous campaign against King James II.

Endowed with a commanding physical appearance, Major John James served as a militia captain for King George III until the war for American independence. He resigned his Royal commission at the onset of the war and served with distinction as a Patriot officer for the entire seven years of the conflict.

James was a longtime elder at Indiantown Presbyterian Church and served in the legislature in the years when South Carolina was being transformed from a colony into a state.

Continue on S.C. 512 as it swings southeast for 9.2 miles to S.C. 41/S.C. 51. Turn right on S.C. 41/S.C. 51 and proceed south for 1.6 miles to the bridge over Black Mingo Creek. A state historical marker calls attention to the skirmish that took place here between the Swamp Fox and Colonel J. C. Ball.

In the wake of the British takeover of Georgetown (covered later in this tour), Ball was dispatched to Black Mingo Creek to establish an outpost. Anxious to disperse the Tories, Marion decided to strike on the steamy night of September 14, 1780. So as not to alert Ball of his approach, Marion placed blankets on the bridge over the creek to muffle the sound of his horses.

Although the confrontation pitted no more than fifty of Marion’s men against a like number from Ball’s force and lasted only fifteen minutes, it was one of Marion’s hottest fights of the war. When it was over, the dark waters of Black Mingo Creek were tinctured red with the blood of the numerous Patriots and Tories who fell. Once again, Major John James was the hero of the day. When Tory bullets felled Captain George Logan, Captain Henry Mouzon, and Lieutenant Joseph Scott, James and his troops moved forward with blazing guns. Unnerved by James’s advance, Ball’s men took flight. According to Peter Horry, “On their retreat, they would not halt a moment at Georgetown, though twenty miles from the field of battle, but continued their flight, not thinking themselves safe until they had got Santee river between him and them.”

Despite the loss of several of his most important officers, Marion had once again vanquished his foe. In their haste to flee the Swamp Fox, the Tories left behind a great quantity of supplies and ammunition. Marion was delighted to take for himself one special spoil of the battle; he claimed the magnificent sorrel gelding, complete with bridle and saddle, that had belonged to his adversary, Colonel Ball. Always anxious to exact revenge against the despoilers of his homeland, Marion named his new mount Ball. For the remainder of the war, Ball was the Swamp Fox’s favorite horse.

Continue south on S.C. 41/S.C. 51 for 1 mile. In the wilderness here is the overgrown site of Welltown. Settled in 1750, Welltown enjoyed prominence during the Revolutionary War as the largest town in this part of South Carolina.

Turn around and drive north on S.C. 41/S.C. 51 for 1.4 miles to S.C. 513. It is 0.8 mile north on S.C. 513 to S.R. 22-6 at the Georgetown County line. Organized in 1768, the county was named for King George II. It was settled primarily by Englishmen who received land patents from the Lords Proprietors.

Turn right on S.R. 22-6 and proceed 1.5 miles southeast to the historical marker for China Grove, an eighteenth-century plantation on nearby Black Mingo Creek. Constructed around 1787 by James Snow, the house has been restored in recent years.

James Snow (1730–93) was a confederate of Francis Marion. Records show that he supplied Marion and Peter Horry with “cattle, many pounds of beef, horses, and clean rice, many bushels, 1780, 1781, 1782.” Snow’s Island, the lair of the Swamp Fox, was named for the Snow family.

For more than a hundred years, China Grove remained the home of the Snows. The frame house underwent extensive restoration during the twentieth century. It is not open to the public.

Follow S.R. 22-6 for 7.7 miles to S.R. 22-4. Turn right, drive south for 7.3 miles to U.S. 701, turn left, and head north for 3.7 miles to the junction with S.R. 22-264 between the Black and Pee Dee Rivers. Several miles northwest of this junction was an old estate called Hasty Point. It acquired its name from a hurried escape by the Swamp Fox from Tarleton.

It was also in the vicinity of the current tour stop that one of the most dramatic events of the war in South Carolina took place. Located in the neck formed by the rivers was the residence of John Postell. His son, also named John, was a captain in General Marion’s brigade. Operating under Marion’s orders dated December 30, 1780, Captain Postell moved into the neck to attack the British supply line to Georgetown.

Upon his arrival, the young American officer was dismayed to learn that his father’s home was occupied by Captain James De Peyster and twenty-nine British grenadiers. Captain Postell immediately devised a plan to remove the unwelcome visitors from the home.

On the night of January 18, 1781, a twenty-eight-man American force commanded by Captain Postell slipped by British sentries and made its way into the detached kitchen of the Postell home. When the sun rose on January 19, De Peyster received a summons from Captain Postell demanding his immediate surrender. De Peyster promptly issued a refusal and braced for an attack. Postell’s men poured out of the kitchen building. Instead of directing his men to open fire on the house occupied by the British, Postell set fire to his family’s kitchen. Then he made another surrender demand, along with a dire threat. If De Peyster and his men did not give up, Captain Postell would torch his father’s house with the British soldiers in it. With great dispatch, De Peyster and his subordinates came out to surrender.

Turn around and drive south on U.S. 701 for 8.7 miles to S.C. 51. Turn right on S.C. 51, proceed north for 0.3 mile, and then look to the right for a tablet dedicated to Marion and his brave soldiers. In the annals of American history, few groups of soldiers did so much with so little as did Marion’s brigade. Every man or boy who joined the Swamp Fox was a volunteer. As a result, the number of men in his command ranged from ten to five hundred.

In that band of swamp fighters, there were no uniforms and no government-issued weapons. Each man furnished his own clothing, guns, swords, and knives. When an emergency arose, Marion issued a call, and his men left their farms and reported with arms in hand, ready to do battle with British regulars and Tories in the swamps of eastern South Carolina.

Turn around at the tablet and return to U.S. 701. Turn right and drive south for 2.8 miles to U.S. 17 in Georgetown. En route, you will pass a state historical marker at the spot where Sergeant McDonald bayoneted Major Micajah Ganey in January 1781.

After a bloody clash between Colonel Peter Horry’s Americans and a band of Tories north of here, Major Ganey took flight toward Georgetown, and Sergeant McDonald, a Patriot, took up the chase. As he drew close to Ganey, McDonald plunged his bayonet into his adversary’s back. In the heat of the moment, the bayonet pulled away from McDonald’s gun, and Ganey rode into town with the weapon in his back. He survived the ordeal.

Turn left on U.S. 17 and drive east for 1.2 miles to the Harrell Siau Bridges over the Great Pee Dee and Waccamaw Rivers. Once across the bridges, you will enter Waccamaw Neck, the narrow strip of land extending from the Atlantic Ocean to the Waccamaw River. During the Revolutionary War, the area produced large quantities of badly needed salt.

Continue north on U.S. 17 for 0.8 mile to two state historical markers at a turnout on the left side of the road.

One of the markers stands near the site of Clifton Plantation, where President George Washington was entertained by Captain William Alston in late April 1791. A twentieth-century house now stands on the estate. It is not open to the public.

The other marker calls attention to the nearby island where two of America’s greatest freedom fighters arrived from Europe. On June 13, 1777, the Marquis de Lafayette, Baron Johann de Kalb, and a group of volunteers landed on North Island in their quest to fight for American independence. The Europeans selected North Island—accessible only by boat today—for their landing because its isolation enabled them to escape the British blockade.

Once ashore, the newcomers found a single house on the island—the summer residence of Major Benjamin Huger of the South Carolina militia. When he heard a knock at his door, Huger expected to open it to find British raiders. Instead, he was pleasantly surprised to see Lafayette, who explained that he and his group had set sail from Bordeaux fifty-four days earlier and were looking for a pilot to take them to the mainland. Huger welcomed the allies into his home and showed them warm hospitality over the next two days. It was here that Lafayette recorded his first impressions of America in a letter to his wife: “The customs of this world are simple, honest, and altogether worthy of the country where everything echoes the beautiful name of liberty.”

From the historical markers, retrace your route south on U.S. 17 to the bridges over the Great Pee Dee and the Waccamaw. A state historical marker for the Revolutionary War battles at Georgetown stands at a turnout between the two bridges. The turnout affords a panoramic view of Georgetown, the third-oldest town in South Carolina. Settled as early as 1705, the town officially came into being in 1729 when Elisha Screven began selling lots. Three years later, the new town was recognized as a port of entry.

As you look down on the venerable port city from the current tour stop, it will be evident that water has played a crucial role in the history of Georgetown. Less than 10 miles to the east is the mighty Atlantic Ocean. Just south of the bridges, the Pee Dee and the Waccamaw converge to form Winyah Bay, which flows southeast from the Georgetown waterfront to the Atlantic. From the west, the Sampit River flows into Winyah Bay on the Georgetown waterfront. Farther south, the Santee empties into the Atlantic.

In the years leading up to the fight for independence, rice and indigo plantations thrived in the low-lying areas adjacent to the rivers that flow into Georgetown. Planters brought their crops to the port for shipment to the outside world. Thus, at the outbreak of the Revolution, Georgetown was an important city.

From the Battle of Fort Moultrie in June 1776 to the fall of Charleston in May 1780, Georgetown was a bustling place. However, on July 1, 1780, British naval commander John Plumer Ardessif attacked and captured the town by sea. He seized the vessels then in port and sent naval raiders out to plunder nearby plantations. The outrages committed by those sailors in Georgetown and the surrounding countryside incensed the men who would soon make up the nucleus of Francis Marion’s army.

Upon taking possession of Georgetown, the British wasted no time in establishing a base here. Over the next eleven months, the Swamp Fox attacked the town on several occasions in an attempt to liberate it.

On November 15, 1780, Marion launched a raid on Georgetown after being informed that the town was garrisoned by only fifty British soldiers. Area Tories reinforced the Redcoats, however, and the Patriots were repulsed.

On January 24, 1781, the Swamp Fox, reinforced by Lighthorse Harry Lee and his vaunted cavalry, attacked Georgetown and captured Colonel Campbell, the commander of the two hundred British soldiers defending the town. Once again, however, Marion was unable to capture the port.

Finally, on June 6, when the Swamp Fox made his third attempt to take Georgetown, the British evacuated the port, leaving behind their stores. Marion and his men captured the goods, destroyed the enemy fortifications, and then went on to new challenges.

To visit the historic port city, proceed across the bridge and follow U.S. 17 to Wood Street. Turn left on Wood, drive four blocks to the junction with Front Street in the heart of old Georgetown, and park nearby; the beauty, charm, and historic essence of this quaint seaport are best enjoyed on foot.

Begin the short walking tour at the Kaminski House Museum, located on the waterfront at 1003 Front Street. Constructed in 1769, this magnificent three-story brick-and-frame mansion rests on one of the most elevated spots in all of Georgetown.

Paul Trapier II, called the “King of Georgetown” because of his significant business holdings in the Revolutionary War era, was the first owner of the house. Trapier was an early leader in the Patriot defense of Georgetown. The last private owner, Mrs. Harold Kaminski, donated the house and its exquisite antique furnishings to the city of Georgetown in 1972. Today, the house is open to the public as a museum. A fee is charged.

Adjacent to the Kaminski House Museum is the Robert Stewart House, at 1019 Front Street. This eye-pleasing two-and-a-half-story Georgian brick structure was built around 1750. On April 30, 1791, President George Washington spent the night here on his famous tour of the South.

Washington was welcomed to Georgetown by a fifteen-gun salute and a “Company of Infantry handsomely uniformed,” as he put it.

In an official proclamation read to the president, the citizens greeted him with these words: “We are no less happy, sir, at being called upon the laws to obey, and to respect as the first magistrate of the Federal Republic, that person, whom of all men were disposed to revere as our benefactor, and to love as the father of his country.”

After a full day of toasts, teas, receptions, a public dinner, and a ball, the chief executive retired to the Robert Stewart House.

In his diary, he recorded his reflections on the town: “George Town seems to be in the shade of Charleston—It suffered during War by the British, having had many of its Houses burnt. The Inhabitants of this place (either unwilling or unable) could give no account of the number of Souls in it, but I should compute them at more than 5 or 600.—Its chief export, Rice.”

The house is not open to the public.

Walk between the Robert Stewart House and the Kaminski House Museum to Harborwalk, a public walkway that stretches the length of the historic waterfront. From Harborwalk, you can enjoy a spectacular waterfront view of the Robert Stewart House, which sits on a promontory overlooking the Sampit River.

Return to Front Street, turn right, and walk to the Federal Building, at 1001 Front. This structure is a former post office and customs house. A bronze plaque near the entrance commemorates “the 175th anniversary of the landing of the Marquis de Lafayette at North Island on Winyah Bay June 13, 1777, and the first day issue of the Lafayette Memorial Stamp in Georgetown, South Carolina, June 13, 1952.”

Continue east down Front Street for two and a half blocks to Broad Street. This was the site of the British headquarters during the war; a D.A.R. plaque on the nearby Italianate building notes the site.

You’ll also see two state historical markers nearby.

One of them details the early history of Georgetown. After the Swamp Fox liberated the port from British control in June 1781, some of General Sumter’s men plundered the homes and plantations of area Tories. In retribution, British gunboats entered the Sampit River, appeared on the waterfront near the current tour stop, opened fire, and rained down a deadly barrage of shells on the city. More than forty houses and buildings were destroyed in the attack.

The second marker pays homage to Francis Marion, the liberator of Georgetown.

Nearby is Francis Marion Park, which overlooks Harborwalk. A D.A.R. monument in the park is dedicated “to the honor and glory of Francis Marion and his men who under extreme hardships did such valued service for the independence of their country in the war of the American Revolution.”

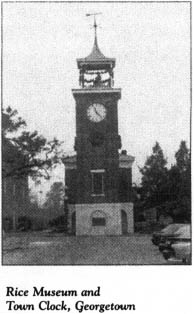

From the junction of Front and Broad, continue east on Front for one block to Screven Street, named for Elisha Screven, the founder of Georgetown. At this junction stands the most famous landmark in this ancient town, the Rice Museum and Town Clock.

Located on the waterfront, the Greek Revival brick structure was built in 1842; the clock tower was added in 1845. In 1970, the Georgetown Historical Commission acquired the building. After a period of restoration, the commission opened it as a museum to chronicle the historic importance of rice and indigo to Georgetown. A D.A.R. tablet affixed to the exterior of the Rice Museum commemorates the 150th anniversary of Lafayette’s landing. Inscribed on the plaque are these words: “He came to draw his sword for the young republic in the hour of her greatest need.”

Adjacent to the Rice Museum is Lafayette Park. A bust of the young French soldier is located in this placid setting. Born to wealth in France, Lafayette (1757–1834) was an orphan by age twelve, a soldier by thirteen, and a husband by sixteen. He was an untested captain in the French army in 1775 when he learned about the mounting tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain.

Six weeks after his arrival in Georgetown, Lafayette appeared before the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and pledged his services as a volunteer in the fight for liberty. Commissioned a major general without a command on July 31, 1777, the young soldier met General George Washington the following day. From the outset, Washington liked Lafayette. Though his young protégé had never seen a minute of combat, the American commander was convinced he would be a good soldier.

Time proved Washington right. Lafayette matured rapidly and became a trusted and skillful military tactician and strategist. From his inauspicious landing here in coastal South Carolina, the “boy”—as Cornwallis called him—emerged to play a key role in subduing the British at a place called Yorktown.

Walk one block north on Screven Street to Prince Street. At the northwestern corner of the intersection is the Georgetown County Courthouse, built around 1824. Like many county courthouses in this book, it was designed by native South Carolinian Robert Mills. One of America’s greatest architects, Mills designed the Washington Monument, the masterpiece erected to honor the man who led the American armies in the Revolution.

Return to the junction of Screven and Front. Walk east on Front for one block to Queen Street. At the northeastern corner of the intersection stands the Mary Man House, at 528 Front. This Georgian-style rice planter’s house has a second-floor ballroom. The home was completed in 1775 and survived the fighting around Georgetown in the years that followed. Some years later, Theodosia Burr Alston, the wife of the governor of South Carolina and the daughter of Aaron Burr, danced in the ballroom on the night before the ill-fated voyage during which she vanished forever.

Proceed another block on Front to Cannon Street. Near the waterfront at 15 Cannon stands the Dr. Charles Fyffe House. Constructed in 1765, this two-and-a-half-story Georgian dwelling belonged to its builder, Dr. Fyffe, a Scottish physician, at the outbreak of the Revolution. Because of his loyalty to the Crown, Dr. Fyffe was forced to flee the country in the early stages of the war. His house was confiscated, and he never regained possession of it.

Just across the street at 16 Cannon is the Red Store Warehouse, which rests on a lot that was once reserved for a fort. It is known that the Swamp Fox attacked the fort in Georgetown on several occasions, but the location of that fort is unknown. Historians have concluded that it was most likely not at the current tour stop, since a shipyard was located here in the years leading up to the Revolution. Built in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the warehouse was the site where Theodosia Burr Alston boarded the Patriot for the mysterious voyage that ended her life.

If you care to see another house owned by Dr. Charles Fyffe, walk across Front Street to 107 Cannon. Dr. Fyffe built two houses on this lot before the war. Only one survives today. Like the house on the waterfront, the dwellings here were confiscated when Dr. Fyffe fled the country; however, the physician regained possession of this property.

Resume the route east on Front Street; it is one block to St. James Street. A state historical marker at the southwestern corner of the intersection calls attention to the John and Mary Cleland House, which stands nearby at 405 Front.

Built by the Clelands around 1737, this two-story structure is one of the oldest houses in the city. Archibald Baird, a nephew of John Cleland, acquired the property in 1753. When Baird and his family returned from a trip to England in 1775, he was branded a British sympathizer. He subsequently lost most of his fortune and died without friends.

A later owner of the house was John Withers, Jr., a Patriot officer who fought in the Battle of Fort Moultrie in 1776.

Turn around and retrace Front Street to the Rice Museum. Walk through Lafayette Park to Harborwalk. A leisurely stroll along the historic waterfront will take you back to the Kaminski House Museum, where the walking tour ends.

Return to your vehicle and drive east on Front to Orange Street. Turn left and proceed two blocks north to Highmarket Street. At the northeastern corner of this intersection stands the Childermas Croft House, one of more than thirty eighteenth-century homes in the city. This much-altered dwelling was built around 1765. During the Revolutionary War, its owners were evicted by British forces, and the house was used by the Redcoats as a hospital. Following the war, cows were stabled in the house in the false hope that the animals would rid the place of germs.

Turn right on Highmarket Street and drive one block to Broad Street. A state historical marker for Prince George’s Parish Church, Winyah, stands in the shadow of the towering Episcopal church.

Completed in 1753, this brick Jacobean-style structure has remained in continuous use since that time, with the exception of brief periods when it underwent restoration after suffering damage in the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. A dozen years of labor and materials imported from England were needed to create this architectural masterpiece.

A plaque near the front entrance notes that the church was used to quarter British soldiers during the Revolution. Horses were also stabled here by the Redcoats. Much of the interior was burned before the occupation army left town.

The church’s ancient cemetery holds the graves of local men who took part in the fight for independence.

Turn left on Broad Street and proceed one block to Duke Street, where you’ll see a state historical marker for Beth Elohim Cemetery. The cemetery is located at the northeastern corner of the intersection.

As early as 1762, Georgetown boasted a large Jewish population. Before the eighteenth century came to an end, the Jewish community assumed a leading role in the political and economic life of the town. Buried within the brick-walled cemetery here are several Jews who were ardent supporters of the American fight for independence. Mordecai Myers, Abraham Cohen, and Solomon Cohen were vocal opponents of British taxation of the colonies. Myers, a local merchant, subsequently served as a supplier for American troops during the war.

Turn left on Duke Street, drive one block to Orange Street, turn left again, and proceed one block to Highmarket Street. Turn right on Highmarket and follow it five blocks to U.S. 17. Cross U.S. 17 on Highmarket and continue west for 1.6 miles to White’s Bridge Drive. A state historical marker at the junction points out that Lieutenant Gabriel Marion, the nephew of the Swamp Fox, was murdered by Tories about 0.25 mile north of here.

In January 1781, General Marion dispatched Captain John Melton and a scouting party that included Lieutenant Marion to the Sampit Road. As the Patriots were making their way through a swampy morass, they came face to face with a strong force of Tories under the command of Captain Jesse Barfield. Both sides fired at each other. Lieutenant Marion, affectionately called “Gabe” by the Swamp Fox, had his horse shot from under him. Barfield, the Tory leader, sustained a painful gunshot to the face.

As the two armies disengaged, the Tories captured Gabe and began clubbing him. Recognizing one of their number as a man he had seen at the home of his uncle, the young Patriot cried out for mercy and took hold of the man. But the Marion name proved fatal to him. His captors cried, “He is one of the breed of that damned old rebel!”

The Tories demanded that their compatriot push Gabe away. Finally, they pulled the young American officer free. A gun was thrust against his breast, the trigger was squeezed, and buckshot plowed through his heart.

Throughout the months of guerrilla warfare, General Francis Marion had witnessed unspeakable acts of violence, but Gabe was the first of his kin to give his life in the service of the Swamp Fox. Francis loved Gabe like a son, and the news of his murder brought great sorrow. To hide his tears, Marion turned his face away from his soldiers when he received the grim tidings.

By the next morning, he regained his composure. To his assembled partisans, he said, “As to my nephew, I believe he was cruelly murdered. But living virtuously, as he did, and then dying fighting for the rights of men, he is no doubt happy. And this is my comfort.”

Retrace your route to the junction with U.S. 17. Turn right and proceed south for 1.9 miles to S.R. 22-18 (South Island Road). Turn left, drive 3.3 miles to S.R. 22-23, turn left again, and go 0.7 mile to the entrance to Belle Isle Garden and Yacht Club. At the security gate, request permission to visit Battery White and the mini-museum located in Belle Isle Yacht Club.

Belle Isle was the boyhood home of Francis Marion. His parents were first-generation Carolinians of Huguenot descent. When Francis was about six years old, they moved the family from Goatfield Plantation in Berkeley County to the present tour stop so their children might be near the English school in Georgetown. While they were here, the Marions dropped their French traditions.

Perry Horry, one of Marion’s greatest subordinates, acquired Belle Isle in 1801. No remains of the Marions’ plantation exist today.

Battery White, a Civil War fortification, was built on the site of Belle Isle. When Belle Isle Gardens were developed in the twentieth century, the old breastworks were incorporated into the beautiful landscape. The remains of the fortifications can still be seen among the azaleas and live oaks.

Return to the junction with S.R. 22-18. Turn left, go south for 4.3 miles to S.R. 22-30, turn right, and proceed southwest on a pleasant 7.6-mile drive that passes the entrances to numerous antebellum plantations. Much of the route is shaded by a canopy of moss-laden trees.

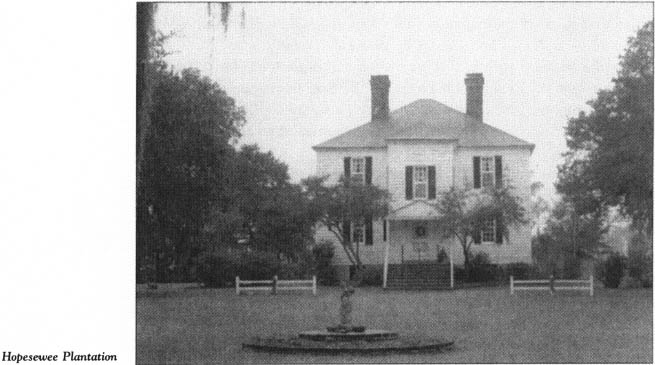

At the junction with U.S. 17, turn left and drive south for 0.5 mile to the state historical marker for Hopsewee Plantation. To see the well-preserved plantation where Thomas Lynch, Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was born, turn right at the historical marker. An admission fee is charged.

Of immense architectural importance, the white two-story house was constructed of black cypress for Thomas Lynch, Sr. (1727–76), in 1739. Set on a high bluff, it commands a spectacular view of the Santee River.

Thomas Lynch, Sr., was the son of the man who discovered how to cultivate rice in coastal South Carolina. He was a person of enormous wealth and political influence when the colonies began questioning the taxation policies of Great Britain. Based upon his distinguished service in the provincial assembly, Lynch was elected to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765. In the years that followed, South Carolina had no greater advocate for independence. His fellow citizens sent Lynch to the First Continental Congress, where he was an outspoken opponent of the continued importation of British goods to America. His position won him friends in the North and a broad base of support back home.

His only child, Thomas, Jr. (1749–79), was born at Hopsewee. After receiving his early education on the plantation, he went to England, where he studied at Cambridge and Eton. Upon his return to South Carolina, he followed in his father’s footsteps and served in the provincial assembly. As South Carolina moved toward independence, the young Lynch volunteered as a captain in the First South Carolina in 1775. A recruiting trip exposed Captain Lynch to a fever that left him weak for the duration of his short life.

Early in 1776, while serving in the Continental Congress, Thomas, Sr., suffered a serious stroke. His son was promptly elected as an extra delegate and dispatched to Philadelphia to aid his ailing father. While there, Thomas, Jr., signed the Declaration of Independence for South Carolina. At twenty-nine, he was one of the youngest signers.

In December 1776, father and son began the long trek back to South Carolina. Tragedy—one of a series soon to befall the Lynch family—struck when they reached Annapolis, Maryland. There, Thomas Lynch, Sr., suffered a fatal stroke.

By the time Thomas, Jr., reached home, he was seriously ill. His health remained poor over the next two years. In 1779, desperate to regain his strength, Lynch sailed with his wife to the West Indies. From there, they headed for southern France. After their ship set sail, it was never heard from again. It is presumed that all aboard were lost at sea.

Mrs. Thomas Lynch, Sr., married General William Moultrie after her husband’s death.

Return to U.S. 17 and drive south for 0.2 mile to the bridge over the Santee River. A careful backward glance will reveal one last vista of Hopsewee in its majestic river setting.

The tour ends at the river, which serves as the boundary between Georgetown and Charleston Counties. If you wish to continue with Tour 3, simply cross the bridge.