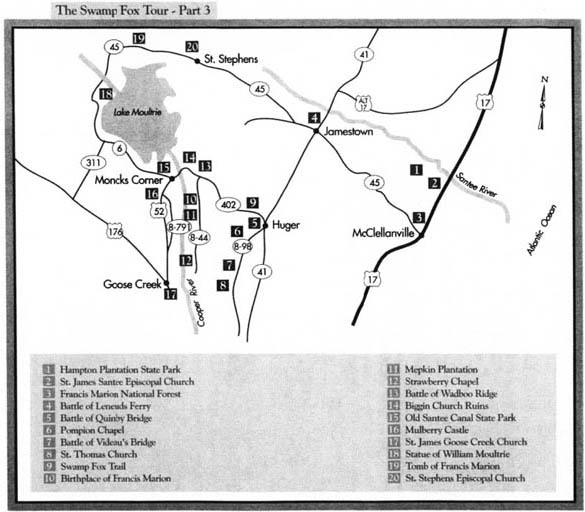

Hampton Plantation State Park, McClellanville, Francis Marion National Forest, Moncks Corner, Lake Moultrie, St.Stephens

Total mileage: approximately 164 miles.

THIS TOUR CAN BE COMBINED with Tours 1 and 2 for a complete look at the life of Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox.” This particular tour includes both his birthplace and his burial site.

The tour begins on U.S. 17 at the bridge that crosses the Santee River between Georgetown and Charleston Counties. Drive south across the bridge into Charleston County. Follow U.S. 17 for 1 mile to the state historical marker honoring Revolutionary War statesman Thomas Pinckney. (For information on Pinckney, see Tour 5, pages 68–69.) The history of St. James, Santee, is chronicled on the reverse side of the marker. This area was the site of the earliest French Huguenot settlements in South Carolina. Many descendants of the settlers, including the Swamp Fox, fought nobly for American independence.

Continue 0.2 mile south on U.S. 17 to S.R. 10-857. Turn right on S.R. 10-857, then turn left on to the unmarked sandy lane; this was formerly the King’s Highway, the primary coastal road in Revolutionary War times. Drive 2.4 miles; you’ll pass through a wilderness area that reveals not a single sign of human habitation. Suddenly, St. James Santee Episcopal Church will come into view. You’ll find it a stark contrast to the surrounding wild landscape.

Constructed in 1768, this architectural masterpiece was a departure from the rural church architecture of colonial South Carolina. The handsome brick structure, highlighted by classical porticos in front and back, shows the influence of St. Michael’s in Charleston.

Long abandoned as a place of worship, the church is nonetheless open to visitors. Its interior, which features pews that have never been painted, is little changed from the time local citizens worshiped here during the Revolution.

Note the ancient tombstones in the yard surrounding the church. One of the most weathered stones bears the nearly illegible details of the Revolutionary War record of Colonel Samuel Warren. During the Battle of Savannah, Colonel Warren lost a leg. He promptly mailed the severed limb to two aunts in England who thought ill of him for fighting against Great Britain. His father, the Reverend Samuel Fenner Warren, served as rector of this church before and during the Revolution.

Return to S.R. 10-857. Turn left and proceed 0.4 mile north to the entrance to Hampton Plantation State Park. Turn right and follow the entrance road to the parking lot. Admission to the park is free, but there is a fee for tours of the home that is its centerpiece.

Constructed between 1700 and 1730, the massive frame mansion has been owned at various times by the Horrys, the Pinckneys, and the Rutledges, families whose names are indelibly etched in the Revolutionary War history of South Carolina.

In 1757, Daniel Huger Horry acquired Hampton and promptly set about adding its two-story ballroom. Today, that ballroom, with its sky-blue ceiling and its floorboards more than thirty feet in length, is one of the few surviving in South Carolina outside Charleston.

At the onset of the Revolution, Daniel Horry served as an officer in the Second South Carolina and participated in the defense of Charleston. However, when Charleston fell, he took the oath of allegiance to the Crown. By doing so, he may have spared his plantation from destruction by the British.

As you walk the unfurnished rooms of the restored house, you are a guest in the same mansion that once attracted such renowned guests as Francis Marion, Lafayette, Daniel Webster, Edgar Allen Poe, Robert E. Lee, and John James Audubon. But the most famous guest of all was the first president of the United States.

When George Washington called at Hampton in 1791, he was greeted at the front portico by Harriott Horry and Eliza Lucas Pinckney, who wore sashes bearing the president’s likeness. During his stay, Washington was instrumental in sparing an oak tree that had sprung up on the horse-racing track that stood in the front lawn. Today, the tall, mighty “Washington Oak” casts its shade over the lawn where the president stood more than two centuries ago.

Return to the junction of S.R. 10-857 and U.S. 17. Turn right and drive south on U.S. 17 for 6.5 miles to S.C. 45 at McClellanville. Turn right and proceed north for 6.3 miles to Wambaw Creek, where you’ll enter Berkeley County and Francis Marion National Forest.

An ancient political subdivision, Berkeley County was established on May 10, 1682, as one of the first three counties in the province of Carolina. It was named in honor of John William Berkeley, one of the Lords Proprietors.

Francis Marion National Forest encompasses more than a quarter of a million acres in the area where the Swamp Fox was born and where he later carried out his guerrilla warfare against Banastre Tarleton and lesser-known adversaries.

Follow S.C. 45 for 14.1 miles through the national forest to the junction with U.S. 17A/S.C. 41 at Jamestown. Turn right and drive 1.7 miles north to the Leneuds Ferry Bridge over the Santee River, where a state historical marker calls attention to the Battle of Leneuds Ferry.

On May 6, 1780, Colonel Anthony White and his New Jersey Continentals made their way to this ferry site after their raid at the plantation of Elias Ball to the south, where they had captured seventeen of Tarleton’s infantrymen. Unaware that Tarleton had been alerted about the raid, White’s men casually joined Colonel Abraham Buford and the Third Virginia at the ferry. Suddenly, Tarleton struck. Although the Americans held a numerical superiority, they were no match for Tarleton’s legion. Approximately a hundred Continentals were lost in the fight, including a number of soldiers who drowned while trying to swim the river.

Return to the junction of U.S. 17A/S.C. 41 and S.C. 45. Proceed south on S.C. 41 for 14.3 miles to S.R. 8-98 at the village of Huger. Drive south on S.R. 8-98 for 0.3 mile to the Ralph Hamer Boat Landing, located adjacent to the bridge over Quinby Creek. Leave your car in the parking lot at the landing and proceed on foot to the walkway near the bridge. You’ll see a state historical marker detailing the Battle of Quinby Bridge, fought on July 17, 1781.

Colonel John Coates moved his British soldiers to this creek after burning Biggin Church (discussed later in this tour). General Thomas Sumter decided to pursue Coates. Lighthorse Harry Lee’s cavalry led the way, and the infantry of Sumter and Marion followed, moving as fast as their legs would carry them.

Lee’s horsemen chased Coates across the bridge to Thomas Shubrick’s plantation, where the Redcoats, armed with a howitzer, took up a strong defensive position. When Marion appeared on the scene, he conferred with Lee. The two veteran warriors agreed that any further attack would be counterproductive.

Sumter and his infantry came up around five o’clock on the afternoon of July 17. He ignored the advice of Marion and Lee and promptly issued an order to attack. Although they fought valiantly, the Americans suffered heavy losses and were forced to retire from the engagement.

As a result of this defeat, Sumter lost a measure of respect. Indeed, Colonel Thomas Taylor informed the “Gamecock” that he would no longer obey his directives.

For years afterward, heavy rains washed up the bones of soldiers who died in the battle and were buried nearby. Local tradition holds that at night, the ghosts of headless Redcoats clatter about the bridge.

Return to your vehicle and drive south on S.R. 8-98 for 2 miles to the state historical marker for Pompion (pronounced “Punkin”) Chapel. If you care to walk 0.25 mile down the grassy lane adjacent to the marker, you will reach the magnificently preserved Georgian structure, erected in 1763 to replace a cypress building constructed in 1703. This was the first Church of England building in America outside Charleston. Its name comes from the bluff on which it rests. The church is not open to the public except on special occasions.

Continue south on S.R. 8-98 for 4.3 miles to the bridge over French Quarter Creek. It is another 0.9 mile to the state historical marker for Brabrant Plantation. It was on this plantation that the Battle of Videau’s Bridge was fought on January 2, 1782. While waiting for General Francis Marion’s army, Colonel Richard Richardson was soundly defeated by Major John Coffin and an army of 350 Tories. American casualties were reported to be as high as 77.

It was also here that Mad Archy Campbell met his demise. Campbell, considered one of the most colorful officers in the British army, was taken captive in the battle and was subsequently shot when he attempted to flee.

One story about Mad Archy concerns the day he took Margaret Philips, a Charleston lady, out for a carriage ride to nearby St. James, where he put his pistol to the head of the local Anglican minister and ordered him to marry the couple. With the unwilling bride-to-be howling screams of protest, the minister calmly announced to Campbell that he would marry them only with the consent of Miss Philips and her mother.

Continue south on S.R. 8-98 for 4.4 miles to the historical marker for St. Thomas Church. Built in 1819, the tiny whitewashed brick edifice replaced the original building on the site, which dated to around 1708; a forest fire claimed it in 1815. In the loblolly pine forest surrounding the church are numerous graves. The stone over the grave of Richard Fordham notes that he served aboard the United States frigate Randolph during the Revolution.

Follow S.R. 8-98 for another 2.5 miles to S.R. 8-33. Turn left, drive east for 1 mile to S.C. 41, turn left again, and proceed 12.8 miles to S.C. 402 at Huger, a community settled by French Huguenots as early as 1735. Turn left on S.C. 402 and head northwest for 2.5 miles to the state historical marker for Silk Hope Plantation. Not open to the public, this plantation is an ancient place. It was the home of Sir Nathaniel Johnson, the governor of South Carolina from 1702 to 1709. He is buried on the estate. Cornwallis had his headquarters here for several months during the Revolutionary War.

Continue on S.C. 402 for 0.4 mile to the Huger Recreational Area of Francis Marion National Forest. The recreational area offers picnic and camping facilities under a canopy of moss-laden live oaks. It is an excellent place to enjoy the land that figured so prominently in the life of the Swamp Fox. Nearby is the Swamp Fox Trail, a 20-mile hiking route that follows old logging roads, paths, and creeks deep into the wilderness where Marion thrived.

Proceed 11.1 miles on S.C. 402 to S.R. 8-44 and turn left. It is 2.5 miles to the state historical marker that commemorates the birthplace of Francis Marion at Goatfield Plantation, which was located nearby.

Gabriel Marion and Esther Cordes—the parents of the Swamp Fox—were married in 1715. Both the Marion and Cordes families had come to Carolina in 1685 after the Huguenots were driven from France following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

Francis Marion was the sixth and last child born to Gabriel and Esther. At his birth in 1732, Francis was “not larger than a New England lobster, and might easily enough have been put into a quart pot,” according to Peter Horry. Although his childhood was a happy one, the Swamp Fox was a frail, scrawny lad who suffered from badly formed knees and ankles.

By the age of fifteen, Francis was intent on becoming a sailor. His parents, hopeful that a stint at sea might aid the growth of their puny son, gave their permission. On his first voyage as a crewman on a West Indies schooner, his ship was attacked and severely damaged by a whale. In their haste to escape the sinking ship in a lifeboat, young Marion and other survivors failed to take any food or water with them. After drifting for five days under a hot sun, the desperate men killed a little dog that had made its way through the water to the lifeboat, drank its blood, and ate its raw flesh. Two of the crewmen died a day later, but Marion and the others ultimately made landfall.

Though his ordeal at sea ended Marion’s career as a sailor, he returned to South Carolina in excellent health. According to Horry, “His constitution seemed renewed, his frame commenced a second and rapid growth while his cheeks, quitting their pale, suet-colored cast, assumed a bright and healthy olive.”

Back at home, Marion settled on family land in Berkeley County and took up farming. His first experience as a soldier came in 1761, near the end of the French and Indian War. As a lieutenant under the command of Captain William Moultrie, Marion displayed extraordinary skill and valor in the expedition against the Cherokees. His distinguished service drew the attention of many influential men in South Carolina.

In 1773, the young military hero purchased a plantation on the Santee River 4 miles south of Eutaw Springs. Little could he have imagined that, nine years later, he would enjoy his greatest moment as a soldier at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, where he and his militiamen would save the day for Major General Greene. (For more about the Battle of Eutaw Springs, see the Tour 20, pages 286–89.)

Continue south on S.R. 8-44 for 3.3 miles to the state historical marker for Mepkin Plantation. To visit the plantation site, now known as Mepkin Abbey, turn left into the entrance.

Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, the publishers of Time and Life magazines, acquired this estate in 1936; they later donated it to the Roman Catholic Church. Since 1949, the plantation has been a Trappist monastery. Today, the monks of Mepkin Abbey open the grounds of the historic plantation to the public on a daily basis.

From the handsome entrance gates, you’ll drive a long avenue of mighty oaks; near the end of the tree-shaded lane is a visitor center where members of the monastery welcome guests to the grounds.

This three-thousand-acre estate, situated on the Cooper River 30 miles above Charleston, was once the home of Henry Laurens (1724–92), one of the most effective diplomats that the American colonies sent to Europe. Sadly, his original manor house was burned by the British during the Revolutionary War and destroyed by Union forces in the Civil War.

Long before the Revolution, Henry Laurens was one of the wealthiest of South Carolinians, having amassed a fortune as a trader in rice, indigo, wine, and slaves. As the possibility of hostilities between the colonies and Great Britain grew, Laurens had everything to lose and nothing to gain by supporting the fight for independence. However, he took up the cause of the colonies without hesitation.

In 1776, Laurens was elected vice president of South Carolina. A year later, South Carolina sent him to the Continental Congress, where his fellow delegates elected him to succeed John Hancock as president of that body in November 1777. Political discord led Laurens to resign as president after thirteen months of service.

His colleagues in Congress appointed Laurens as a diplomat to Holland in 1779. On August 3, 1780, he set sail from Philadelphia. Included in his papers were a draft of a treaty with the Netherlands and documents to secure a loan for the American war effort.

His ship, the Mercury, was seized by the British off Newfoundland on September 3. In order to protect his country, Laurens dumped the confidential papers overboard, but his captors salvaged them from the cold waters of the Atlantic.

Now a prisoner, Laurens was taken to London, where he was interrogated by the Privy Council. His refusal to cooperate with the inquiry led to his imprisonment in the Tower of London.

For fifteen months, Laurens languished in the infamous tower. Although his health failed, he twice refused pardons that were conditional on his pledge of service to the British cause. To the offer, he responded, “I will never subscribe to my own infamy and to the dishonor of my children.”

After payment of a fortune in bail, his release was secured on December 30, 1781. Four months later, Laurens was paroled in a prisoner exchange. His counterpart was none other than Lord Charles Cornwallis himself.

While still a prisoner, Laurens had been appointed by Congress as one of America’s peace commissioners. He arrived in Paris just days before the signing of the preliminary treaty to officially end the Revolutionary War.

His final service to the new nation came during 1782 and 1783, when he served as the unofficial United States ambassador to Great Britain. Upon his return to America, Laurens was offered another term as president of Congress, but by then, he was a broken man. He had sacrificed his all—his health, most of his fortune, and his son—to the cause of independence.

In 1785, Henry Laurens came home to Mepkin Plantation, where he lived in quiet retirement until his death.

To see his grave, walk along the main road leading past the visitor center to the point where the forested area behind the center ends. Turn left and walk across a field for approximately 0.25 mile to the Laurens family cemetery.

Henry Laurens (or his dust) was laid to rest here after his death in 1792. Almost phobic that he would be buried alive, Laurens had directed in his will that he be cremated. His is believed to have been the first cremation in the United States.

Also in the isolated cemetery is the cenotaph of John Laurens (1745-82), the distinguished son of Henry Laurens. Born in South Carolina, John received a superior education in England and Switzerland. Like his father, he proved a true hero in the quest for independence.

In 1777, he left his educational pursuits in Europe and hurried home to America to take up the sword. An immediate favorite of General George Washington, Laurens was appointed as his aide-de-camp. His ability to speak French made him indispensable as Washington’s translator and secretary.

On the field of battle at places like Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth, Laurens displayed great valor. Following the latter battle, he challenged General Charles Lee to a duel after Lee made negative remarks about Washington. Lee was wounded in the duel.

Laurens soon made his way to South Carolina to aid in the defense of Charleston. When the port city fell, British forces captured him, but he was quickly exchanged.

A year later, Congress sent him to Europe on a crucial mission to obtain assistance from the French government. When Laurens was introduced to King Louis XVI at a social gathering, the South Carolinian, disregarding court etiquette, handed the monarch a paper describing the desperate needs of the Americans. The king frowned, but his minister took the documents. Twenty-four hours later, a loan was pledged for the American cause.

Back in America, Lieutenant Colonel Laurens won accolades for his battlefield conduct at Yorktown. After that fight, General Washington named Laurens and Viscount de Noailles to head the surrender negotiations with Cornwallis.

Following the surrender at Yorktown, Laurens was drawn back to his home state, where fighting continued for more than a year. On August 27, 1782, a British ambush at Combahee Ferry (see Tour 7, pages 104–5) cost the gallant officer his life. He was buried near the site where he fell; a marker was also placed in the cemetery here.

Upon learning of the death of John Laurens, George Washington remarked, “He had no fault that I could discover—unless it was an intrepidity bordering on rashness.”

When you are ready to leave Mepkin Abbey, return to S.R. 8-44 and drive south for 1.8 miles to S.R. 8-1054. Turn right and proceed 0.2 mile to Strawberry Chapel. Built in 1725 as a chapel of ease for Biggin Church, this well-preserved structure is all that remains of the town of Childsbury, which was abandoned following the Revolutionary War. The pink-colored edifice and its cemetery, filled with graves from the eighteenth century, are located in a picturesque setting on the banks of the Cooper River.

Follow S.R. 8-1054 to its terminus near the entrance to Rice Hope Plantation. This plantation was first owned by Dr. William Reed, a deputy surgeon general in the Revolutionary War. It is now operated as a bed-and-breakfast.

Adjacent to Rice Hope on the south was Comingtree Plantation, the site of the wedding of Henry Laurens and Eleanor Ball in 1750.

Retrace your route to the junction of S.R. 8-44 and S.C. 402. Turn left on S.C. 402. You will cross the bridge over Wadboo Swamp almost immediately.

Three Revolutionary War skirmishes—on January 24, 1781, July 16, 1781, and August 29, 1782—were fought in this vicinity. The third was the final battle of the famed Swamp Fox. After going up against an old British adversary, Major Thomas Fraser (see Tour 19, page 258), General Marion bid farewell to his loyal band.

Drive east on S.C. 402 for 1.5 miles to the state historical marker for Biggin Church, the ruins of which can be seen just off the left side of the highway. Park near the old church cemetery if you care to examine the two remaining brick walls of the historic edifice.

Constructed in 1755 to replace an earlier building destroyed by a forest fire, the church was named for a nearby creek. During the Revolutionary War, Biggin Church was located at the intersection of three roads and was thus a strategic point for both armies. For a time, British forces garrisoned the church and used it as a supply post. Finally, in 1781, Lieutenant Colonel John Coates put the torch to the building when he was forced to abandon it.

Among the parishioners at Biggin Church during the Revolutionary War era were Henry Laurens and William Moultrie.

The church was restored after the war, but a forest fire in 1890 damaged it beyond repair.

Numerous graves from the eighteenth century are in the adjacent cemetery. You may notice a low-arched vault in a state of deterioration. A fascinating tale is associated with this vault. During the Revolutionary War, Turpentine John Palmer and his brother were sealed in the vault by the enemy because John’s son was a soldier in the command of the Swamp Fox. You might even make out the indentations in the brick—tangible reminders of the two men’s grim attempt to cut their way out of their living entombment. After two days of being buried alive, they were released. They were so weakened by the ordeal that it took them two days to walk the 10 miles to their homes.

Follow S.C. 402 for 0.8 mile to U.S. 52 at Moncks Corner, the seat of Berkeley County. Turn left, drive south for 1.2 miles to S.R. 8-801, turn left again, and proceed 0.6 mile to Stony Landing Road. Turn left to reach the entrance gate of Old Santee Canal State Park at historic Stony Landing.

This 250-acre park was named for the Santee Canal, a project started in 1786 to aid commercial water transportation from inland South Carolina to Charleston. A portion of the old canal can be seen in the park along the bluffs of Biggin Creek. Among the many attractions at the park is the Berkeley County Museum, housed in the antebellum Dennis House. Numerous displays and exhibits tell the long, storied history of Berkeley County and Moncks Corner.

Established in 1735, Moncks Corner was an important commercial center by the time the war for independence began. When British forces surrounded Charleston on three sides in April 1780, Moncks Corner was a vital link to the outside world for Charlestonians.

General Isaac Huger’s 500 troops were handed the awesome responsibility of keeping the lifeline to Charleston open. By the evening of April 13, the lead elements of the 1,400-man British attack force under Lieutenant Colonel James Webster were within striking distance of Huger. This first wave of attackers was composed of some of the best troops sent to America as part of the British expeditionary force: Banastre Tarleton and his legion and Patrick Ferguson and his 150 rangers.

At three o’clock in the morning on April 14, Tarleton and Ferguson struck General Huger’s unsuspecting troops near Biggin Bridge. In the fight that followed, the Patriots were routed. Soon thereafter, Webster arrived with the bulk of his army, and the fate of Charleston was sealed.

Return to U.S. 52 and turn left. It is 1 mile to the junction with S.R. 8-791. Turn left on S.R. 8-791, follow it south for 2.9 miles to S.R. 8-407, turn left again, and head east for 1.7 miles to S.R. 8-408. Turn left and drive north for 1 mile to the entrance to Lewisfield Plantation.

Not open to the public, this colonial plantation has as its centerpiece the majestic frame mansion called Little Landing, constructed by Keating Simons in 1774. Simons had little time to enjoy his paradise here on the western branch of the Cooper River, as his estate soon became a beehive of Revolutionary War activity.

When Charleston fell, Simons was paroled to Lewisfield, which was already being used by the British as a landing site. In 1781, he was at his home enduring the indignities rendered by the British raiding party when Colonel Wade Hampton happened by. The spirited fight that ensued ended in a victory for Hampton, who took seventy-eight prisoners.

Fully aware that British authorities would implicate him in the successful attack, Simons chose to ride off with Hampton “with a rope around his neck,” as the saying went; under British law, the punishment for breaking parole was hanging.

For the duration of the war, Simons avoided the noose and served as a gallant soldier under the command of the Swamp Fox. Marion promoted him to the rank of major. Following the war, Simons and Marion were close friends—so close that when the heirless Swamp Fox died, he willed his plantation to Keating Simons’s son.

Retrace your route to the junction of S.R. 8-407 and S.R. 8-791. Turn right on S.R. 8-791 and drive north for 0.7 mile to S.R. 8-383. Turn right and follow S.R. 8-383 for 0.5 mile to the entrance gate of Mulberry Castle.

Built around 1711, this magnificent manor house is not open to the public. Despite its age, it remains one of the finest houses in South Carolina. Its four small tower rooms, each surmounted by a ball-shaped cupola, lend a medieval appearance to the house.

During the Yemasee War of 1715, the sturdy castle served as a fortress. More than half a century later, British cavalrymen used Mulberry as their headquarters during the Revolution.

Thomas Broughton, an ardent Patriot who was a descendant of a former governor of the colony, owned the plantation when the fight for independence began. On one occasion, he rode up to Mulberry with his neighbor Keating Simons, only to find the plantation overrun by British horse soldiers. Without inquiring as to the men’s identity, the presumptuous Redcoat commander offered the owner of the castle a drink from Broughton’s own decanter. Hiding his indignity, Broughton took the drink, but Simons adamantly refused. Then the British troopers plundered the plantation.

Thereafter, Broughton was forced to flee British raiders on numerous occasions. On his final attempt at flight, he was thrown headlong into a tree by his horse. He perished in the accident. But there are those who say the ghosts of the Broughton family still roam the halls and stairways of the ancient castle.

Return to S.R. 8-791 and turn left. Drive south for 7 miles to U.S. 52, turn left, and go 5.2 miles to the state historical marker for St. James Goose Creek Church. To see the beautiful church building, turn left on Ned Road and drive 0.1 mile to Goose Creek Road. Turn right and follow Goose Creek Road for 0.8 mile.

Construction on this stuccoed edifice took almost a decade. Completed around 1715, it is considered by many to be one of the most interesting and beautiful Anglican churches from the colonial period. It is the oldest church building in South Carolina.

On the interior (which is not generally open to the public), the Royal arms of Great Britain decorate the wall above the chancel. No other colonial church in America bears such ornamentation. It is believed that British soldiers spared the church because of the special decor. However, the constant reminder of the Crown did not meet with the approval of some of the parishioners during the Revolutionary War. On one occasion, when the minister said a prayer for King George III, a prayer book thrown from the congregation narrowly missed the cleric’s head.

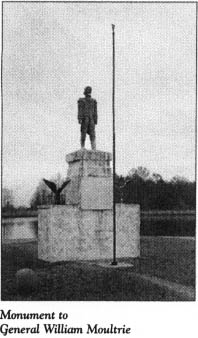

Retrace your route to U.S. 52. Turn right, drive 0.8 mile to U.S. 176, turn left, and proceed north for 19.6 miles to S.R. 8-135. Turn right and head north for 7.4 miles to S.C. 6. Drive north on S.C. 6 as it winds along the shore of Lake Moultrie, the 60,400-acre body of water named in honor of Revolutionary War hero William Moultrie.

It is 5.2 miles on S.C. 6 to S.R. 8-132. En route, you will pass a state historical marker near the site of a country store operated by Thomas Sumter before the Revolutionary War.

Proceed north on S.R. 8-132 for 0.8 mile to S.R. 8-1141 (Black’s Camp Road). Turn right and follow S.R. 8-1141 to its terminus at Black’s Camp on the shore of Lake Moultrie, where you’ll see a massive statue of General William Moultrie, the Patriot hero who saved Charleston from British capture early in the war. (Moultrie’s life is chronicled in Tour 4, pages 55–58.)

Return to S.R. 8-132. Turn right, drive north for 2.1 miles to S.C. 45, turn right again, and follow S.C. 45 as it begins to circle Lake Moultrie. After 5.3 miles, you will reach the entrance to Francis Marion’s tomb; a state historical marker is located on the left at the entrance. Turn left and follow the mile-long avenue that ends at the tomb of the great warrior.

Maintained by the National Park Service, the cemetery is located in a quiet setting on land that was once part of Belle Isle Plantation, the estate of Gabriel Marion, brother of the Swamp Fox. Francis lived with his brother at Belle Isle for fifteen years. Pond Bluff, the estate acquired by the Swamp Fox in 1773, was located some miles away and is now under the waters of lake that bears his name, Lake Marion.

Following his illustrious military career, Marion served his state as commander of Fort Johnson at the entrance to Charleston Harbor and as a member of the state senate for several terms. In 1786, he married his wealthy spinster cousin, Mary Esther Videau. Although he had survived countless Indian arrows, bullets fired from Tory and British guns, and venomous reptiles in the swamps of South Carolina, the Swamp Fox was no match for his hot-tempered wife. When he arrived home, he always tossed his hat through the window before entering. If it did not sail back out of the house, he reckoned it was safe to go in. When the Swamp Fox died on February 27, 1795, Mrs. Marion was said to be inconsolable. She lies at his side at the current tour stop.

That the legacy of Francis Marion lives on is beyond dispute. Though he left no children, countless boys have borne his name over the past two hundred years. And a study of the United States map shows that twenty-nine towns and seventeen counties are named for the man who ruled the swamps of South Carolina. Like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, he is the subject of enduring legend. His daring exploits at a time when the fight for freedom had few friends in South Carolina continue to inspire generation after generation of his countrymen. In the early 1960s, Walt Disney introduced him to millions of Americans through television in a movie called, appropriately enough, The Swamp Fox.

Continue 11.3 miles on S.C. 45 to St. Stephens Episcopal Church in the town of St. Stephens. As you near the town, you will see a small monument honoring Hezekiah Maham (1739–89). Born in this area, Maham was the Patriot officer who invented the Maham Tower, which allowed Marion and Lighthorse Harry Lee to invest Fort Watson (see Tour 1, page 11).

St. Stephens Episcopal Church is a massive brick structure completed in 1768. An expansive cemetery with many graves from the eighteenth century encircles it. Several ghosts are said to haunt the graveyard, at least one of them a spirit from the Revolutionary War.

Dave Peigler was a notorious local horse thief and Tory. He made a living plundering the homes and plantations of his Patriot neighbors while they were away doing battle with other Tories and British regulars. His career of thieving came to an abrupt halt when he raided the plantation of Captain Theus. To Peigler’s dismay, Theus was home.

The captured Peigler was escorted to the current tour stop for execution. Before the hangman could complete his duty, the thief escaped, but only momentarily. He was returned to the gallows and swung off just as a British patrol arrived.

On dark nights, a ghost with a rope around its neck, a rum bottle in one hand, and a pistol in the other roams the cemetery. It is said to be Dave Peigler.

The tour ends at St. Stephens Episcopal Church. If you care to visit more sites associated with the Swamp Fox, this tour may be combined with Tours 1 and 2.