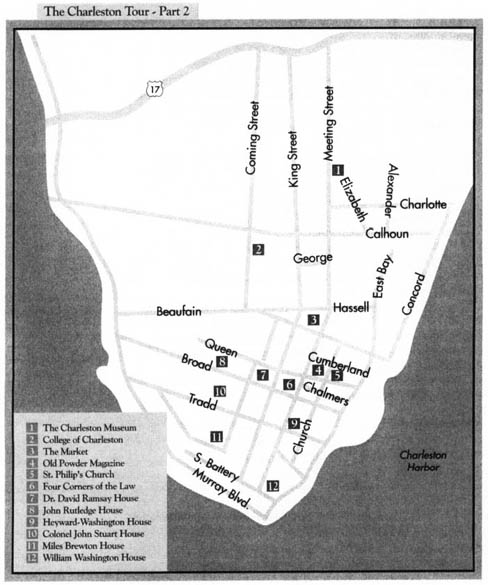

Charleston Museum, College of Charleston, the Powder Magazine, St.Philip’s Episcopal Church, the Four Corners of Law, Charleston waterfront

Total walking distance: approximately sixty-four blocks.

THIS WALKING TOUR may be combined with Tours 4 and 6 for a complete look at the role Charleston and its environs played in the Revolutionary War. Those who enjoy sightseeing on foot may wish to combine this tour with the walking portion of the previous tour; together, the two form a loop encompassing the area from White Point Gardens on the Charleston waterfront to the Charleston Museum.

The tour begins at the Charleston Museum, located at 360 Meeting Street at the intersection with John Street. This is billed as the oldest museum in the United States. Established in 1773, it moved to this spacious, modern $6 million complex in 1980. Inside, visitors are treated to a treasure trove of artifacts dating to the earliest history of Charleston.

From the museum, walk west on John Street to King Street. Head south on King for three blocks to George Street, turn right, and proceed one block to the College of Charleston. This is the main campus of the oldest municipal college in the United States. Founded in 1770, the college is located on land that was reserved for educational purposes as early as 1724. During the Revolution, the barracks of William Moultrie’s Second South Carolina were located at the present tour stop.

Continue west on George Street for half a block to Glebe Street. The Bishop Smith/Glebe House is located at 6 Glebe. Constructed around 1770, it sits on land once owned by St. Philip’s Church.

During the Revolution, this impressive brick Georgian structure was the home of Robert Smith, the rector of St. Philip’s. On an unknown date during the fight for independence, Smith, a native of England, announced from the pulpit that he was going to don the uniform of an American soldier and join the fight against his native land. He emerged from the war a hero and became the first Episcopal bishop of the state he helped establish.

In recent years, this home has served as the residence of the president of the College of Charleston.

Turn around and walk east on George Street for two and a half blocks to Meeting Street. The Middleton-Pinckney House, erected around 1796, is located near the intersection at 14 George Street. This was the home of Major General Thomas Pinckney. The three-story stucco house has a distinctive polygonal front projection.

Born in Charleston, Thomas Pinckney (1750–1828) was the younger brother of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. He was reared in England and groomed as a British gentleman. Trained in law at the Middle Temple in England and instructed in military matters in France, Pinckney was one of the best-educated Americans of his time.

Upon his return to Charleston in 1774, he found the colony headed toward the fight for independence. Pinckney never hesitated about casting his lot with the American cause. That Charleston was able to remain free of British troops until 1780 was due in part to the engineering work of Thomas Pinckney and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

When Charleston fell, Captain Thomas Pinckney avoided capture only because he had slipped outside the enemy lines in a desperate but unsuccessful attempt to obtain aid for the besieged city. Anxious to do what he could to assist the flagging American fortunes, he hurried north, where he joined George Washington and the Continental Army. Consequently, the force of Continentals assigned to Major General Horatio Gates in his campaign to take Camden in the summer of 1780 included Pinckney. Pinckney was wounded in that horrendous defeat. After obtaining his parole and being exchanged, he returned to active service and was an officer in Lafayette’s command at Yorktown.

When peace came, Pinckney worked to build a spirit of nationalism by advocating lenient treatment of former Tories. His greatest service to the new nation, however, came in international diplomacy. In 1792, he was appointed United States minister to Great Britain. Though he was not particularly effective in that role, his skillful work in 1795 on the accord with Spain known as “Pinckney’s Treaty” resulted in the recognition of the United States’ claim on the Mississippi.

Pinckney subsequently made repeated attempts to resign from his post in London. Bound to duty until he was officially relieved, he worked tirelessly to gain the release of the Marquis de Lafayette from prison.

In 1796, Pinckney came home, where his popularity led to his nomination as the Federalist Party’s candidate for vice president of the United States. However, Alexander Hamilton, anxious to see that John Adams was not elected president, pushed Pinckney’s name for the presidential slot. In the end, Adams won the presidency, and the South Carolinian never attained either office.

He was subsequently elected to the United States House of Representatives. During the War of 1812, the federal government appointed Pinckney as a major general; however, he never took the field against the British.

Turn around and walk one block west on George Street to King Street. Turn left, proceed three blocks south to Hassell Street, turn left again, and go one block to the Colonel William Rhett House, located at 54 Hassell.

This stuccoed brick dwelling on a half-basement, erected around 1712, is one of the oldest houses in the city. By the time of the Revolution, it was more than half a century old and had a famous history of its own. William Rhett, the builder, was a hero along the entire Atlantic seaboard because of his capture of the infamous pirate Stede Bonnett in 1718.

From the junction of Hassell, Pinckney, and Meeting Streets, proceed east on Pinckney to the American Military Museum, located at 40 Pinckney. This museum chronicles the history of the American armed services from the Revolutionary War to the modern era. An admission fee is charged.

Return to the junction of Pinckney, Hassell, and Meeting. Turn left on Meeting and walk south past Hayne Street to Market Street. At 188 Meeting is the imposing Market Hall, which stands at the site of the northern limit of the old city wall.

Walk west on Market Street for one block to King Street. Turn left, go south for two blocks to Clifford Street, turn right, and proceed one block to the junction with Archdale and Magazine Streets. Nearby at 6 Archdale is the Unitarian Church. Construction of this magnificent cathedral began in 1772, but work was halted after the fall of Charleston in the Revolutionary War. During their stay in the city, the British occupied the church and destroyed its pews. Completed in 1787 and remodeled in 1852, this was the first Unitarian church in the South.

Just down the street is the Philip Porcher House, located at 19 Archdale. This two-story frame Georgian structure was built by Philip Porcher, a Loyalist. Because of Porcher’s allegiance to the Crown, his property was confiscated during the Revolution. However, unlike many other Tories, he was able to regain possession of the estate after leading citizens vouched for his good character.

Retrace your route to the junction of Clifford and King Streets. Cross King on to Cumberland Street. Walk two blocks on Cumberland to the Old Powder Magazine, located at 79 Cumberland. Open to the public as a museum, this structure was built at the close of the seventeenth century and is the oldest public building in the Carolinas. Throughout much of the eighteenth century, gunpowder used in the defense of Charleston was stored here. Although a new magazine was erected elsewhere in 1748, this facility continued to be used through the Revolution.

Inside the ancient building, exhibits chronicle the history of colonial South Carolina. Listed on the National Register of Historic Landmarks, the Powder Magazine was the first structure in the city restored solely for historic reasons.

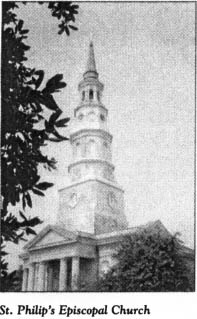

Continue on Cumberland to the end of the block; turn right on Church Street and walk south to St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, located at 146 Church. Near the street is a state historical marker for this ancient place of worship.

Established in 1670, St. Philip’s was the first Anglican church south of Virginia. It now houses the oldest Episcopal congregation in Charleston. The original church building was completed in 1722 and burned in 1835. The existing edifice was completed three years later. Towering high above the city, the church’s illuminated spire served as a lighthouse for ships entering the harbor. Well into the twentieth century, the federal government paid for the maintenance of the light.

During his seven-day stay in Charleston in 1791, President Washington attended a service at St. Philip’s.

Adjoining the church is its ancient cemetery, a veritable outdoor museum. Famous South Carolinians from virtually every period of the state’s history are buried here. The most notable of the many Revolutionary War heroes interred at St. Philip’s are Charles Pinckney, a signer and draftsman of the United States Constitution (whose grave remains unmarked at his request); Christopher Gadsden; Rawlins Lowndes; and Edward Rutledge.

Christopher Gadsden (1724–1805), one of South Carolina’s earliest advocates of independence, was born in Charleston. The son of a British merchant-fleet officer and port official, he was educated in England and served as a purser in the British navy before returning to Charleston. Here, prosperity and influence flowed to Gadsden as a result of his mercantile business.

A dispute with the Royal governor of South Carolina in 1762 soured Gadsden toward the mother country and its control of the colonies. At the Stamp Act Congress, Great Britain had no greater critic than Christopher Gadsden. Branded a radical by many Charlestonians because of his temper and his outspokenness, Gadsden was nonetheless acknowledged to be South Carolina’s leader in mounting an effective but orderly resistance to Great Britain.

Following his election to the First Continental Congress in 1774, South Carolina appointed Gadsden as a colonel of a regiment of Continental troops raised in 1775 in response to the open hostilities taking place in the North. As a member of the Second Continental Congress in 1775, Gadsden gained a national reputation as a hawk when he advocated that American forces attack the British at Boston.

Anxious to aid in the defense of his home, he left Philadelphia in January 1776 to assume command of Fort Johnson, one of the primary defense works that protected Charleston Harbor. A month later, he shocked many South Carolinians by openly declaring at the Provincial Congress that the colony should declare its independence. Though many of his influential colleagues considered this treasonous, Gadsden was undaunted. He presented to the body a flag that had a yellow field with a coiled rattlesnake and the words “Don’t Tread On Me.” He also delivered to the Provincial Congress the first copy of Common Sense ever brought to South Carolina.

Though Gadsden’s sentiments were considered premature by most of the colony’s leaders, his boldness and conviction were appreciated far and wide. According to Silas Deane of Connecticut, a member of the Continental Congress who would serve as an American diplomat in Europe during the war, “Mr. Gadsden leaves all New England Sons of Liberty far behind.”

In time, his quest for independence gained widespread popularity. When the war came to Charleston in June 1776, just days before the Declaration of Independence was signed, Gadsden was commanding the garrison at Fort Johnson. On September 16, 1776, he was promoted to brigadier general. However, the lack of military action around Charleston gave him little opportunity to demonstrate his abilities as an officer.

When Major General Robert Howe, the North Carolinian who was the highest-ranking Continental officer born south of Virginia, was given command of the Southern Department in 1777, Gadsden was irate, as were many others in South Carolina and Georgia. Howe’s presence in Charleston after a dismal campaign against the British in Florida did little to win warm feelings for him. Gadsden became his most vocal critic.

Howe demanded that Gadsden issue apologies for his public statements. When Gadsden refused, the two met in Charleston for a duel on August 13, 1778. Gadsden insisted that Howe fire first. His adversary complied, and the bullet nicked Gadsden’s ear. Gadsden next proceeded to fire his gun into the air. He then walked over to Howe, shook his hand, and apologized. Thereafter, the two were close friends.

Gadsden remained active in the political affairs of South Carolina. He played a leading role in the effort that produced a new state constitution in March 1780. However, he angered many conservatives at the convention, including John Rutledge. As a result, his political power was diluted for the remainder of the war. Still, he was elected lieutenant governor in 1780, at the very time Sir Henry Clinton successfully invested Charleston. For much of the siege, Gadsden implored General Benjamin Lincoln to hold out. Ultimately, much blame was placed on Gadsden for the unfavorable surrender terms imposed on Lincoln because of the extended siege.

Taken prisoner at the fall of Charleston, Gadsden had little political or military impact on the war in the years that followed. South Carolina voters elected him governor in 1782, but he declined the office, citing ill health. When peace came, voters sent Gadsden to the state legislature for several terms. He was also a member of the conventions that ratified the United States Constitution and produced yet another state constitution.

Gadsden’s grandson, James, gave his name to the famous Gadsden Purchase.

Also buried at St. Philip’s is Rawlins Lowndes (1721–1800). Born in the West Indies, Lowndes was a prominent politician and office holder in colonial South Carolina. An ardent supporter of the cause of the colonies, he was a leader in the Provincial Congresses. In 1778 and 1779, before the war enveloped the entire state, Lowndes served as president of South Carolina.

You can also visit the grave site of Edward Rutledge (1749–1800), the younger brother of John Rutledge. This brother team provided outstanding leadership as South Carolina struggled throughout the Revolutionary War to attain independence.

Edward was born near Charleston. Like many of his contemporaries in the city, he was educated in England. He returned to Charleston prior to the Revolution and embarked upon a successful career as an attorney.

In 1774, Edward was elected as one of South Carolina’s first five delegates to the Continental Congress. Also in the delegation were his brother John, who was ten years older, and his father-in-law, Henry Middleton. At Philadelphia, the Rutledges often clashed with the delegates from New England. Because of this rancor, John Adams left us with a rather unflattering description of the brothers: “[Edward] Rutledge is a very uncouth and ungraceful speaker, he shrugs his shoulders, distorts his body, nods and wriggles with his head, and looks about with his eyes from side to side, and speaks through his nose. … His brother, John dodges his head too, rather disagreeably, and both of them spout out their language in a rough and rapid torrent, without much force or effort.”

Adams’s opinion notwithstanding, Edward became a political force to be reckoned with. While serving in the Continental Congress, he also sat as a member of the Provincial Congresses in South Carolina.

When John Rutledge, Christopher Gadsden, and other senior members of the South Carolina congressional delegation left Philadelphia because of ill health and other reasons, Edward assumed the leadership of the South Carolina representatives in the crucial months leading up to July 4, 1776. Even though he believed independence was inevitable, he urged caution and deliberation. Finally, on July 2, Rutledge advised his fellow delegates that they should vote for independence. Two days later, he became the youngest delegate to cast his lot for a free and independent America.

After the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Congress dispatched Rutledge, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin to Staten Island, where they labored in vain with British officials to reach a peace accord. When the conference adjourned, the young South Carolinian hurried back to Charleston, where he assumed the role of artillery captain. His state attempted to send him back to the Continental Congress in 1779, but Rutledge refused the assignment. Instead, he devoted his energy to the military defense of South Carolina, and Charleston in particular.

As British forces massed near the port city in the spring of 1780, General Benjamin Lincoln sent Captain Rutledge through the lines on a perilous mission to obtain assistance. In the course of his journey, he was captured by enemy soldiers. He was subsequently imprisoned at St. Augustine for almost a year. Following his parole and exchange, Rutledge lived in Philadelphia while Major General Nathanael Greene was liberating South Carolina.

After the war, voters elected Rutledge to both houses of the state legislature and to the state conventions of 1788 and 1790. Although poor health had robbed much of his vigor, he was elected governor in 1798. He died in that office two years later.

From St. Philip’s, walk one block south on Church Street to Queen Street. Located at 140 Church is the majestic French Protestant (Huguenot) Church. Constructed in 1844, this was the first ecclesiastical structure of Gothic Revival design in the city. It is the fourth church building at its site.

This congregation was formed in 1687 by Huguenots who had fled France to avoid religious persecution. When Charleston was captured by the British, the French residents of the city were deemed prisoners of war.

Located nearby at 135 Church is the Dock Street Theatre. Of special interest in this Georgian-style auditorium is the carved bas-relief of the Royal Arms of England. It was duplicated from a bas-relief located over the altar at the Goose Creek Chapel of Ease.

Walk one block west on Queen Street to the brightly painted three-story apartment building at 22-28 Queen. This complex was constructed before the Revolutionary War. One Sunday morning while en route to morning worship at St. Philip’s, General William Moultrie stopped in the alley adjacent to the building (known alternately as Philadelphia Alley or Cow Alley) to answer a challenge to a duel. Gaining the upper hand early in the contest with swords, Moultrie “pinked” his opponent, sheathed his weapon, and resumed his leisurely stroll to church, where he sang more fervently than ever.

Proceed to Meeting Street at the end of the block. Located just north of the intersection at 150 Meeting is the Circular Church, a beautiful Victorian Romanesque structure built in the nineteenth century. Forty-five percent of Charleston’s residents worshiped on this site in the late seventeenth century. The adjacent burial ground dates to 1691. Here, you will see an impressive array of ancient tomb boxes, vaults, and gravestones of some of the leading citizens of Charleston throughout the nation’s history. Found in this, the city’s oldest cemetery, is the largest and most impressive collection of New England slate grave markers south of Boston. Among the Revolutionary War luminaries buried here is Dr. David Ramsay, the historian who preserved much of the Revolutionary War history of South Carolina. Details of Ramsay’s life will be chronicled at his home, visited later on this tour.

Proceed south on Meeting Street for one block to Chalmers Street and turn left. Located at 17 Chalmers is the Pink House, constructed between 1694 and 1712. During its first century of existence, this three-story pink masonry building served as a tavern in Charleston’s red-light district. It was a favorite among sailors and soldiers.

Return to Meeting Street, turn left, and walk one block south to Broad Street. This famous intersection has long been known as the “Four Corners of Law” because the buildings at the corners represent the law of the city (Charleston City Hall), the law of the county (the Charleston County Courthouse), the law of the nation (the United States Courthouse), and the law of God (St. Michael’s Episcopal Church). It was Robert Ripley of “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” fame who coined the popular name. But this intersection played a prominent role in the history of the city and state long before it acquired its catchy nickname.

Begin your tour of the Four Corners at Charleston City Hall, located at the northeastern corner at 80 Broad Street. Constructed around 1800, the stately structure has welcomed virtually every important person who has visited Charleston over the last two centuries. In 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette was entertained here during his triumphant tour of America. The building is the second-oldest city hall in continuous use in the United States.

Open to the public, the second-story City Council Chambers feature a magnificent collection of original oil paintings of famous Americans and South Carolinians. Among the likenesses exhibited here are those of William Moultrie, Francis Marion, Lafayette, James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson. The most valuable work in the splendid collection is John Trumbull’s portrait of George Washington, rendered in 1791.

At the rear of Charleston City Hall is City Hall Park, a quiet, tree-shaded public area dedicated as Washington Square in 1881, during the centennial celebration of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

Among the monuments located on the well-landscaped grounds are several related to the Revolutionary War.

One honors Francis Salvador, the young Jewish soldier who became the first of his faith in South Carolina to give his life for the American cause. (For more information about Salvador, see Tour 10, page 135.)

Also note the memorial to Elizabeth Jackson, the mother of Andrew Jackson. Mrs. Jackson came to Charleston during the Revolutionary War to minister to wounded and ailing American troops. She died while she was here.

The yellow-brick monument base in the park was once adorned with a statue of William Pitt, the British member of Parliament who openly supported the cause of the colonies. On May 8, 1766, the South Carolina Colonial Assembly authorized the statue of Pitt in recognition of “his noble Disinterested and Generous Assistance … towards obtaining the Repeal of the Stamp Act.” During the siege of Charleston, the statue’s right arm (depicted holding the Magna Carta) was blasted away by a British cannonball. The statue was moved from its original location to this site at City Hall Park in the 1880s, then was relocated to the Charleston Museum a hundred years later.

From Charleston City Hall, walk across Broad Street to St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, located at the southeastern corner. Considered one of the most spectacular colonial church buildings in America, St. Michael’s is the oldest religious structure in a city filled with historic churches. At the time of its construction in the mid-eighteenth century, the immense Georgian building was placed at the site of the original St. Philip’s; in 1751, the Charleston parish was divided, and the southern half was named St. Michael’s.

Looking at the 186-foot steeple, you will note that it is surmounted by a weather vane that towers another 7½ feet. Located in the tower is the spectacular four-sided clock that has provided the time to Charlestonians since 1764. During the Revolution, British occupation forces removed the steeple bells and spirited them away to England. They were later returned.

As you admire the unique craftsmanship, consider that this church is one of the few of its age to retain its original design and appearance.

On the inside, you will quickly note that the interior is as commanding as the exterior. The box pews are original. George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette sat in these pews, as did many local Revolutionary War heroes. A baptismal font dating to around 1770 and the original case of the church’s 1768 Snetzler organ are also in the sanctuary.

In the adjoining church cemetery are the graves of a number of Revolutionary War leaders, including Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and John Rutledge, both of whom signed the United States Constitution for South Carolina.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (1746–1825) was the brother of Thomas Pinckney and the second cousin of Charles Pinckney. He was born in Charleston and schooled in law in London and in the art of soldiering in Caen, France. When he returned to Charleston, he married Sarah Middleton, the daughter of Arthur Middleton, a social and political kingpin in the area.

Because of his formal military education, Pinckney proved the most able soldier in his distinguished family. When the colony raised its first regiment of Continental soldiers, it named Pinckney as a captain. He took an active role at Sullivan’s Island in William Moultrie’s successful defense of Charleston in 1776. Several months later, he was promoted to colonel.

Because of the lack of military activity in the Charleston area, he then went north, where he served as George Washington’s aide-de-camp and took part in the action at Germantown and Brandywine.

In 1778, Colonel Pinckney returned home, where he was involved in the defense of his native city. When the British attacked Charleston in the spring of 1780, Pinckney was commanding the decrepit Fort Moultrie. Because of its deteriorated condition, the installation was of no significance in the siege.

Pinckney was taken prisoner when the city fell. He was not exchanged and paroled until 1782, due to his unwavering allegiance to the American cause. The grateful government later awarded him the brevet rank of brigadier general.

Throughout the war, Pinckney was also an influential politician. In 1779, he rose to the presidency of the state senate.

He resumed his political career after the war. As a leading Federalist, he advocated a strong national government at the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia in September 1787. When the delegates assembled on September 17, he signed the historic document (allegedly written by his cousin). Back home, he led the successful fight to gain its ratification in South Carolina.

Between 1790 and 1795, the infant federal government offered Pinckney a number of prestigious posts—the command of the United States Army (1791), associate justice of the Supreme Court, secretary of war (two times), and secretary of state (1795). But for reasons unknown, he declined them all.

Finally, in 1796, Pinckney accepted an appointment as American envoy to France, replacing James Monroe. This came at a time when France was poised to declare war on the United States. When the French government refused to recognize his credentials and threatened to arrest him, the South Carolinian fled to the Netherlands. France welcomed him a year later, when he arrived with John Marshall and Elbridge Gerry on a special mission to restore relations between the two countries.

While in Paris in 1797, Pinckney became embroiled in the famous XYZ affair, in which three French agents attempted to offer a peace treaty in return for a $250,000 bribe for Talleyrand. Pinckney steadfastly refused the offer; it is said that he remarked to X, “It is No! No! Not a sixpence!” As a result of his refusal to meet the French demand, an undeclared war between the two nations began. The United States summoned Pinckney home, where he was appointed as a major general in preparation for a land war with France that never materialized.

Pinckney’s name was now known nationally. As a result, he was the Federalist Party’s nominee for vice president in 1800 and for president in 1804 and 1808. But by that time, the party’s popularity was waning, and Pinckney lost all three campaigns.

Also buried in the cemetery is John Rutledge (1739–1800). The older of the famous brother duo that guided South Carolina through the Revolutionary War and into statehood, he was born in Charleston, the son of Dr. John Rutledge. The younger John Rutledge received an excellent legal education in England and was admitted to the bar there in 1760. Upon his return to Charleston, voters elected him to the colonial assembly.

Although Rutledge was opposed to many of Great Britain’s policies toward the colonies—most particularly the Stamp Act—he was against independence and urged reconciliation with the mother country. His views were made known on the national front when he was a delegate to the first two Continental Congresses, held in 1774 and 1775.

In 1776, he was named president of South Carolina, a post he held until March 1778, when he resigned in opposition to the liberalization of the state’s constitution. Nine months later, however, he was elected governor, thus becoming the state’s first chief executive to use that title, rather than president.

When Charleston fell to the British, Governor Rutledge escaped into the hinterlands, where he attempted to operate the government in exile. While Tarleton relentlessly pursued him, Rutledge attempted to rally South Carolinians for the uphill battle facing the state. To that end, he made the wise decision to appoint Francis Marion and Thomas Sumter to carry out partisan activities until the Continental reinforcements that he had requested could arrive.

In early 1781, Rutledge sought exile in North Carolina, where he traveled with Major General Nathanael Greene in his miraculous retreat across the state. When Greene brought the Continental Army to South Carolina several months later, he was accompanied by the governor.

Cognizant that he could not legally serve another term, Rutledge resigned his office on January 29, 1782, after convening the state legislature at Jacksonboro (see Tour 7, page 101). There, he was praised for his efforts to help the state while in exile.

Voters sent Rutledge back to Congress in 1782 and 1783. At the federal Constitutional Convention in 1787, he was an outspoken advocate for the interests of the South. There, he signed the United States Constitution for South Carolina.

For the remainder of his public career, he sought judicial posts. In 1791, President Washington appointed Rutledge as the senior associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. Rutledge later resigned that position to become the chief justice of South Carolina. When Washington was prevailed upon to nominate Rutledge to replace John Jay as chief justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1795, Rutledge proceeded to bitterly attack Jay’s Treaty, thereby eliminating any chance he had for Senate confirmation.

In his twilight years, Rutledge suffered from insanity. He died just months before his younger brother.

Walk across Meeting Street to the Charleston County Courthouse, the oldest portion of which served as the original South Carolina Statehouse. Constructed in 1753, the building was heavily damaged by fire in 1789 just after the state Constitutional Convention ratified the United States Constitution here.

The colonial and early state legislatures, the provincial court, and the Royal Governor’s Council all convened their meetings inside this building. Important affairs of state were announced to the people from a balcony overlooking the street. It was here that the Declaration of Independence was read publicly for the first time in South Carolina.

Nearby at 8 Courthouse Square is the Meyer Peace House. Constructed around 1787, this three-story stuccoed brick structure was the home of sugar manufacturer Philip Meyer, who acquired the lot from Henry Laurens before the Revolution. A leading local Patriot, Meyer was taken prisoner when Charleston fell to the British and was confined to a prison ship in the harbor from 1780 to 1782.

From the Four Corners, proceed west on Broad Street. A number of historic structures are located in the first block.

The house at 85-87 Broad was built in 1796 by Josiah Smith, an influential merchant who aided the Patriot cause during the Revolution.

Across the street at 92 Broad is the Dr. David Ramsay House. This impressive three-story frame structure of Georgian design was constructed in 1740. During the Revolution, it was the home of David Ramsay, one of the state’s most celebrated physicians.

Educated at the College of New Jersey and the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Ramsay trained under noted Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush before settling in Charleston in 1773 at age twenty-four. He promptly gained social status upon marrying Martha Laurens, the daughter of the eminent statesman.

His medical accomplishments were many. Ramsay is credited with introducing the smallpox vaccine in Charleston; Nathaniel Ramsay, his son, is believed to have been the first recipient. Historians also believe that Ramsay was one of the first physicians in America to recommend that water be boiled before drinking.

Ramsay was an outspoken advocate of independence from the onset of the Revolution. In addition to serving in the state legislature during the war, he took to the field, where his services as a surgeon were in great demand. When Charleston was captured by the British, Ramsay was one of the many Americans taken prisoner. He was confined at St. Augustine.

During his long hours of solitude, he set about writing the history of South Carolina. Initially, he worked from memory. But after the war, he availed himself of firsthand accounts when he took a seat in the Continental Congress. He corresponded with many notable Americans, including Thomas Jefferson, to gather material for his epic work.

His project was entitled History of the Revolution of South Carolina from a British Colony to an Independent State. Before the manuscript was shipped to its publisher in Trenton, New Jersey, Ramsay received the assistance of Nathanael Greene, who proofed and corrected his work. Once the book was in print, Americans learned of the atrocities committed by British soldiers, especially Banastre Tarleton, during the long war. The book was banned in Great Britain.

Located at 95 Broad is the Bocquet House, built in 1770 for Peter Bocquet, who served in the Patriot government of John Rutledge.

Continue west on Broad Street across King Street to the Lining House, located at 106 Broad. A classic example of Charleston’s colonial architecture, this is one of the oldest buildings in the city. It was the home of Dr. John Lining, a noted scientist who moved here from Scotland in 1730. A dedicated observer of the weather, Lining recorded the first meteorological data in colonial America. His work led him to a regular correspondence with Benjamin Franklin, who persuaded Lining to replicate the Philadelphia’s famous kite experiment in a Charleston thunderstorm.

Several doors down is the Izard House, at 110 Broad. This three-story dwelling was erected around 1757. During the Revolutionary War, it was the home of Ralph Izard, a prosperous planter who dedicated his fortune to the cause of the colonies.

At 116 Broad is the John Rutledge House. A state historical marker tells a portion of the history of the house where John Rutledge, sometimes known as “Dictator John,” lived. Constructed in 1763, the three-story mansion is said to be the birthplace of two American institutions—the United States Constitution and she-crab soup.

Considered the city’s best example of a residence erected for official functions, the house has welcomed many distinguished visitors and been the site of several important events. For example, Charles Pinckney called on his close friend John Rutledge here in the spring of 1787. Dominating their dinner conversation was the upcoming federal Constitutional Convention, to which both men had been elected delegates. Later that night, the two statesmen collaborated in composing what became known as the “Pinckney draught” of the Constitution. When Rutledge and Pinckney subsequently affixed their signatures to the United States Constitution in Philadelphia, it contained most of the key provisions drafted here in Charleston. Later, when someone remarked to French political observer Alexis de Tocqueville that Thomas Jefferson had penned the Constitution, he was quick to reply, “There is no mystery about it. A man named John Rutledge wrote it.”

At least two United States presidents have been entertained at the John Rutledge House. In 1791, Rutledge hosted his friend George Washington. Much later, in the early twentieth century, President William Howard Taft was entertained here by Robert Goodwin Rhett, then the mayor of Charleston and the owner of the house. Determined to serve the chief executive a dish he had never sampled, Rhett’s butler (no pun intended) created she-crab soup, now a favorite in coastal South Carolina.

Across the street at 117 Broad is the Edward Rutledge House. Constructed in 1760 by the brother of Henry Laurens, this large Georgian house was later the home of Edward Rutledge, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the brother of John Rutledge. In terms of historic importance, this house stands in the shadow of John’s home, much as Edward did with his older brother.

Near the Edward Rutledge House, turn south off Broad Street on to Orange Street. The Samuel Carne House, at 4 Orange, was constructed in 1776. Carne, a Tory, moved in a year later and lived here for the duration of the war.

Located at 7 Orange Street, the two-and-a-half-story frame Charles Pinckney House was built in 1776 by Charles Pinckney, the father of the man so closely associated with the United States Constitution.

Return to Broad Street, turn right, and walk three blocks to Church Street. Turn right, proceed one block, and cross Elliott Street to see the three-story brick house at 94 Church, a home that holds much history.

Thomas Bee, a distinguished graduate of Oxford University, constructed this mansion around 1760. Like many of his fellow Charlestonians, Bee served as both a soldier and a statesman during the war; he was elected to the state legislature, the Continental Congress, and the lieutenant governorship during the Revolution. In 1790, George Washington rewarded Bee for his selfless service when he appointed him to the federal bench.

Bee’s grandson, Civil War general Bernard Bee, is credited with giving General Thomas Jonathan Jackson his enduring nickname. Upon witnessing Jackson’s valor at First Manassas, General Bee remarked, “There stands Jackson like a stone wall.”

In the early 1800s, the house was acquired by Governor Joseph Alston and his wife, Theodosia Burr Alston, the daughter of Aaron Burr. (For more information about Theodosia Burr Alston, see Tour 2, page 28.)

The famous Nullification Movement that led to the Civil War was begun in this house by John C. Calhoun. Longtime Charleston residents called that event the most dramatic in the city since the Revolutionary War.

Continue on Church Street to the Heyward-Washington House, at 87 Church. This majestic brick mansion is one of the most famous dwellings in the city. Thomas Heyward, Jr., erected it as his townhouse in 1771. He went on to sign the Declaration of Independence five years later. (For a biographical sketch of Heyward, see Tour 8, pages 112–13.)

During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the house was a beehive of activity. While her husband was imprisoned in St. Augustine after the fall of Charleston, Mrs. Thomas Heyward gallantly refused a British command to light candles in the windows as a token of gratitude to the occupation army.

In 1791, President Washington was lodged and entertained in this home, which was located in what was then the city’s most affluent residential area. Regarding his stay here, Washington recorded, “The lodging provided for me in this place, was very good, being the furnished house of a gentleman at present in the country.”

Since 1929, the house has been owned by the Charleston Museum. It is open to the public for a fee. A tour of the interior offers a look at an exquisite collection of period antiques. Furniture appraisers consider the Holmes bookcase to be among the finest pieces of American-crafted furniture in existence.

Continue on Church Street across Tradd Street to see the Capers-Motte House, at 69 Church. It is believed that while President Washington was in residence nearby, he spoke from the second-floor balcony of this three-story masonry dwelling, which dates to around 1750. Its wartime owner, Jacob Motte, was the father-in-law of Thomas Lynch and William Moultrie. Motte’s wife, Rebecca, was the heroine of Fort Motte (see Tour 20, pages 284–85).

The James Veree House, located at 58-60 Church, dates to around 1754. It was once owned by Thomas Heyward, Jr.

Proceed south less than a block to Water Street. At the southwestern corner of the intersection stands the George Everleigh House, at 39 Church. Considered the most-photographed dwelling in Charleston, this pre-Revolutionary War mansion is also one of the largest homes in the city.

George Everleigh built the house around 1757. A prosperous merchant, he opened the South Carolina frontier to settlers by sending British goods deep into the upstate, where they were traded for skins.

On the night of September 14, 1775, Lord William Campbell, the last Royal governor of South Carolina, fled past this house on his official exit from the colony. His flight led most Charlestonians to rally around the cause of independence.

During the Revolutionary War, the house was owned by Colonel James Parsons, a distinguished Patriot soldier and a delegate to the Continental Congress. Parsons was supposedly offered the presidency of South Carolina in 1776, but he declined the office.

In the front yard, you can see a small Revolutionary War-era shot that was dug up on the premises.

Turn right on Water Street and walk one block to Meeting Street. Turn left to see the Gibbes House, located at 37 Meeting. During the Revolution, this dwelling was owned by Governor Robert Gibbes. Upon the arrival of the British, they sequestered the house and forced Gibbes and his family to seek residence elsewhere. When they returned, they discovered that the house had been ransacked. Even the family Bible had been partially burned.

Across the street is the striking Daniel Elliott Huger House, at 34 Meeting. When this three-story mansion was constructed in 1760, it was fit for royalty. In fact, the British government rented the dwelling for Royal Governor William Campbell. It was from this house that he fled on the night of September 14, 1775, after an unruly mob of Patriots gathered in the front yard. Carrying the Great Seal of the province of South Carolina with him, Campbell made it to the safety of the British cruiser Tamar in Charleston Harbor.

Nearby at 30 Meeting Street stands the expansive, three-story Young-Motte House. This was once the home of Colonel Isaac Motte, an acknowledged Tory who served in the Sixtieth Royal Americans.

When the order was given for British forces to evacuate the city, a number of Hessian soldiers deserted and hid in the massive chimneys of this dwelling.

Continue south to the Thomas Heyward House, at 18 Meeting. Constructed in the early part of the nineteenth century by the signer of the Declaration of Independence, this handsome three-story mansion has a hidden room on the second floor.

Nearby at 15 Meeting is the elegant two-story John Edwards House. A dedicated follower of John Rutledge, Edwards was imprisoned at St. Augustine following the capture of Charleston. In his absence, his residence became the headquarters of British vice admiral Marriott Arbuthnot.

Just north of the John Edwards House, turn west on to Lamboll Street. Walk two blocks to Legare Street, turn right, and proceed north for one block to Gibbes Street. Continue north on Legare; in the next block, you will see the spectacular John Fullerton House, at 15 Legare.

This two-story frame dwelling rests upon a raised masonry basement. It was erected in 1772 by John Fullerton, a native of Scotland who had a deep-rooted hatred of the British. He was one of the early Patriots who joined Christopher Gadsden and other like-minded residents under the Liberty Tree to discuss American independence.

Fullerton died before the British captured the city. Had he lived, he would have been mortified when Redcoat officers used his house as their quarters.

Proceed to the two-story house at 31 Legare. It is said that the ghost of a Revolutionary War veteran who was killed in a hunting accident just after the war inhabits this dwelling.

Continue north to the end of the block at Tradd Street, named for Robert Tradd, the first child of English descent born in Charleston. Turn right on Tradd to see the Mrs. Peter Fayssoux House, at 126 Tradd. This impressive three-story frame dwelling was constructed around 1732. It takes its name from the wife of the surgeon general of the Continental Army. She owned the structure before the war.

Walk to the Colonel John Stuart House, at 106 Tradd. It was here that British Indian agent John Stuart conducted secret meetings with the Cherokees in an attempt to gain their support for the Crown in the growing unrest with the colonies. Stuart is believed to have constructed the highly ornamented three-story frame house in 1772.

When he was forced to flee the city for British-occupied Florida in the early days of the war, the home was confiscated by the Americans, who used the second-floor drawing room for strategy sessions.

Legend holds that Francis Marion once leaped out of a second-story window here in an attempt to avoid a friendly drinking contest. He fractured his ankle in the jump and was unfit for duty. However, the accident may have been fortuitous for the Americans. Marion retired to the Santee River area to recover and thus was not in Charleston when the British arrived.

Cross the street to the Jacob Eckhard House, at 103 Tradd. In a city known for its culture, Eckhard is acknowledged to have been the “Father of Music in Charleston.” Ten years after he built this two-and-a-half-story stuccoed brick house in 1797, he organized the first boys’ choir in America while serving as choirmaster and organist at St. Michael’s.

Ironically, Eckhard came to America in 1776 as a Hessian soldier.

From Legare Street, it is two blocks east on Tradd to King Street. Turn right and proceed south to the Miles Brewton House, at 27 King. This two-story mansion is the best-preserved and most elegant Georgian residence in Charleston. Some architectural historians consider it the most complete Georgian townhouse in all of America.

Constructed in 1769, it was the residence of Mrs. Rebecca Motte during the Revolutionary War. Both Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Charles Cornwallis claimed the house as their headquarters during the British occupation of the city. The matron of the house remained in residence and served meals to her unwanted guests with scorn. Meanwhile, she hid her daughters in the attic in order to avoid being separated from her family. She firmly believed that their presence had not been detected by the British. But when Lord Cornwallis offered his gratitude to Mrs. Motte as he prepared to leave town, he rolled his eyes toward the ceiling and remarked that he regretted not having had the opportunity to meet the rest of the family.

During his stay here, a British officer carved the silhouette of Sir Henry Clinton in one of the marble mantels.

Continue south on King to Lamboll Street. Cross Lamboll, walk one block to South Battery, and turn right to see the Magwood-Moneland House, at 39 South Battery. When it was constructed in 1835, this home was placed on a crib of palmetto logs. Some historians believe the logs were the remains of a Revolutionary War redoubt crafted in much the same manner as the original Fort Moultrie.

Walk one block west on South Battery to Legare Street. At 1 Legare is the Edward Blake House, constructed around 1760. This two-story frame house on a raised basement was rolled here on palmetto logs from another site in the city in the 1870s. Its original owner was Edward Blake, a Patriot and the commissioner of the South Carolina navy during the war.

Continue west on South Battery for one block, where you’ll find two historical houses on the waterfront.

The fine Georgian house at 58 South Battery was built in the late eighteenth century by John Blake, a Revolutionary War Patriot and a member of the state legislature.

The exquisite William Gibbes House is located at 64 South Battery. It was constructed in 1772 by William Gibbes, one of the wealthiest shipowners and merchants in the city. When the British arrived in Charleston, Gibbes was taken prisoner because of his sympathy to the American cause and interned at St. Augustine.

In the 1930s, Mrs. Washington A. Roebling, the widow of the builder of the Brooklyn Bridge, purchased the home.

Turn around and proceed east on South Battery past Legare and King Streets to the William Washington House, located between Meeting Street and White Point Gardens at 8 South Battery. Constructed around 1768, this fine two-story frame dwelling was acquired after the Revolutionary War by Colonel William Washington, a noted cavalry commander. Twenty years younger than his famous cousin, George Washington, William maintained a plantation south of the city. His life is chronicled in Tour 6, pages 98–99.

The tour ends here, along the historic Charleston waterfront. As you take one last look at the picturesque harbor, consider the jubilant celebration that took place here on October 27, 1782, when a fleet of forty British ships put out to sea with most of the enemy occupation forces aboard. It was early in the morning on December 14 that the last of the Redcoats sailed out of the harbor. At eleven o’clock that morning, in the wake of their departure, the victorious Continental Army, Nathanael Greene riding at its head, made a triumphant entry into the city. Charleston was free, and so were Americans.

Walk north on Meeting Street to the Charleston Museum to return to where the tour began. Or if you have the energy, you may want to continue your explorations by taking the walking portion of the previous tour, which begins at White Point Gardens and ends near the museum.