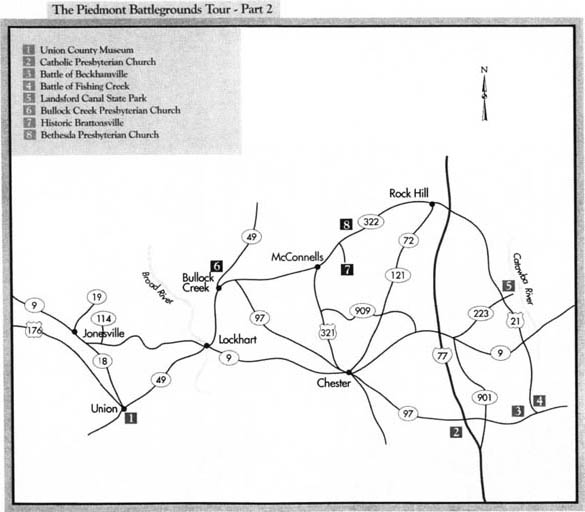

The Piedmont Battlegrounds Tour, Part 2

Jonesville, Union, Chester, Landsford, York County, McConnells, Brattonsville, Rock Hill

Total mileage: approximately 174 miles.

THIS TOUR EXPLORES a portion of north-central South Carolina that was an area of heavy fighting during the last several years of the Revolution.

The tour begins at the intersection of S.C. 18 and S.C. 9 in Jonesville. Drive north on S.C. 18 for 4.5 miles to the bridge over the Pacolet River at Grindal Shoals.

Little remains of the community that once prospered here thanks to the gristmills located on both sides of the river. In early January 1781, General Daniel Morgan camped at Grindal Shoals. When Tarleton began his pursuit of Morgan that ended at Cowpens, he rested the British army at Morgan’s abandoned campsite.

Turn around near the bridge, proceed south on S.C. 18 for 0.5 mile to S.C. 114, turn left, and drive south for 5.8 miles to U.S. 176. Follow U.S. 176 for 5.2 miles into the heart of the town of Union. Turn left on S.C. 49 (Main Street) and drive four blocks to visit the Union County Museum, located in the Federal Building. The museum holds a variety of artifacts from all periods of local history. Sumter and Marion carried out their partisan activities throughout Union County during the Revolutionary War. Nathanael Greene also operated here with his Continentals.

Several skirmishes between Patriots and Tories took place within a few miles of what is now the town of Union. Unfortunately, the exact sites have been lost to history.

In July 1780, Colonel William Bratton set up camp approximately 5 miles away during a recruiting trip. One of his Tory captives escaped and hurried to the enemy camp, where he divulged Bratton’s whereabouts. Before light the next morning, the Tories struck and routed the Patriots.

In the days that followed, Bratton brought his command back to fighting condition. His chance for revenge came later in July. It was an incident that revealed the nature of the civil war that raged in the area.

Bratton and his fifty men surrounded a fortified house that belonged to a man named Stallings. Holed up in the dwelling was a party of Tories. Positioned in front of the house was Captain Love and sixteen Patriots. Bratton took the remainder of his men to the rear.

Suddenly, Mrs. Stallings, the sister of Captain Love, came running out of the house to plead with her brother to refrain from attacking her home. Her pleas fell on deaf ears. Just as she made her way back to the house, a bullet fired from a Patriot gun entered through the open door and plowed into Mrs. Stallings’s body, killing her instantly.

At length, the Tories sent out the white flag, but they soon discovered that even an attempt to surrender meant bloodshed. They made the mistake of attaching the white flag to the barrel of a gun. Confused by the signals, the Patriots sent a bullet into the arm holding the gun.

Soon, the white flag appeared again, this time attached to a ramrod. For Captain Love, the Tory surrender was bittersweet, for it had cost the life of his sister.

Continue about 1.8 miles east on S.C. 49 to Union Cemetery. Located at the site of a former Presbyterian church, the burial ground holds the graves of many Revolutionary War soldiers, including Thomas Brandon, Colonel John Sharp, and Major Thomas Young.

Follow S.C. 49 another 7.8 miles to the junction with S.C. 9 at the Broad River. Proceed across the river, where you will enter Chester County. The highway splits 0.3 mile east of the river; take the right fork and drive southeast on S.C. 9 for 15.5 miles to S.C. 97 in downtown Chester, the county seat. Turn right on S.C. 97 and drive 2.5 miles south to Old Purity Presbyterian Cemetery. Buried here are at least seven Revolutionary War Soldiers from the area.

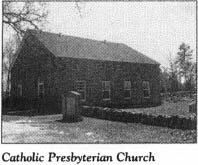

Continue southeast on S.C. 97 for 9.8 miles to S.R. 12-355, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the venerable Catholic Presbyterian Church and Cemetery, the next stop on the tour. Turn right and proceed south for 0.8 mile to the site.

Constructed in 1842, the existing red-brick church houses a Presbyterian congregation that was organized as early as 1759. Buried in the sprawling cemetery adjacent to the church are a large number of Revolutionary War soldiers. The impressive monument near the fieldstone wall of the graveyard was dedicated on August 30, 1933. On the tablet are the names of sixty-one members of Catholic Presbyterian who fought in the Revolution.

Return to S.C. 97, turn right, and drive southeast for 7.3 miles to S.C. 99, where you’ll see a state historical marker for the Battle of Beckhamville (Beckham’s Old Fields). To visit the actual site of the battle, look for the granite marker in the open field northeast of the junction.

Lost to history is the exact date of this battle, but it most likely took place in June 1780, just after the fall of Charleston. Intent on capitalizing on the rising fortunes of the British war effort in the state, a large group of Tories assembled at the current stop to administer oaths of loyalty to area citizens. Although he was heavily outnumbered, Captain John McClure used the element of surprise to his advantage when he attacked the Tories. In what turned out to be one of the first Patriot victories after the loss of Charleston, McClure thoroughly routed a two-hundred-man force of Tories. The battle here served to inspire local citizens to rally for the American cause.

Turn left on S.C. 99 and proceed 1 mile north to the Anderson family cemetery. Buried here are William Anderson and Daniel Green, two of the Patriots who continued the fight for independence after Charleston fell to the British.

Return to S.C. 97, turn left, and drive east for 1.8 miles to U.S. 21 on the northern side of Great Falls. A nearby state historical marker notes that the Battle of Fishing Creek was fought in this vicinity on August 18, 1780.

The exact site of the battle between Thomas Sumter and Banastre Tarleton is unknown. It is most likely under the Fishing Creek Reservoir near the Catawba River dam visible from U.S. 21. To see the granite monument commemorating the battle, follow U.S. 21 as it bends sharply to the north just south of the dam. The marker is located on the hilltop on the eastern side of the road.

As soon as the smoke cleared from the stunning American defeat at Camden on August 16, 1780 (see Tour 19, pages 273–75), a courier was dispatched to warn Thomas Sumter of the setback and to direct him to repair to Charlotte. At the same time, Lord Cornwallis, sensing a complete victory in South Carolina, sent Tarleton after Sumter.

On August 17, Sumter set up camp on the western side of the river just south of the present tour stop. In his camp, he counted three hundred of his own soldiers, a hundred Maryland Continentals, and four hundred militiamen from North Carolina.

Tarleton finally caught sight of his prey that night. Early the next morning, the British commander cautiously approached the Americans with just 160 of his 350 troops. When he came within view of the enemy camp, Tarleton could hardly believe what he saw. Sumter’s men were engaged in three pursuits: cooking, sleeping, and bathing. Apparently, the Gamecock had no idea about what was soon to happen to him.

Tarleton launched a sudden attack against the unsuspecting Americans. The battle was over almost as soon as it began. Awakened by the sound of fighting, Sumter narrowly escaped capture by jumping on a saddleless horse and galloping away.

Two days later, the defeated Gamecock rode into William R. Davie’s camp.

As to the army he left behind, some of his junior officers gallantly attempted to rally the Americans. While they were trying to make a stand, they killed Captain Charles Campbell, the man who had torched Sumter’s home.

Nonetheless, the day belonged to Bloody Ban. When the short battle was over, 16 British soldiers lay dead or wounded. On the other hand, American losses were enormous: 150 dead, 300 captured, 100 British prisoners lost, and 44 wagons of supplies taken.

Continue north on U.S. 21 for 7.4 miles to S.C. 9 at Fort Lawn. Turn left and drive 3.1 miles west to the bridge over Fishing Creek. Just west of the bridge is a state historical marker that calls attention to the home of Justice John Gaston, which stood 2 miles south of the marker during the Revolution.

A distinguished jurist, Gaston served as a justice of the peace for the colonial and state governments. By the time the war came, he was an old man, but he was nonetheless an outspoken advocate for the cause of the colonies. Many area Patriots were spurred to action by Gaston’s fiery words. All nine of his sons fought for independence. Four of them died in battle.

Continue west on S.C. 9 for 3.9 miles to S.R. 12-56, turn left, and proceed 0.7 mile to S.C. 901. Nearby stood an oak known as the Cornwallis Tree. According to local legend, Cornwallis tied his horse to the tree when it was a young sapling, and the animal ate the top out of it.

Turn right on S.C. 901 and drive north for 0.8 mile to S.C. 223. Turn right, proceed east for 6.7 miles to S.R. 12-330 in Landsford, turn right again, and drive east for 2.5 miles to Landsford Canal State Park.

This park, built to showcase the northernmost of four canals engineered in the early nineteenth century to allow navigation of the Catawba River/Wateree River system, is an excellent place to observe a landscape where much Revolutionary War action took place. At various times after the fall of Charleston, Thomas Sumter, William R. Davie, Andrew Jackson, and many other noted American soldiers camped along the river in this area. Cornwallis crossed the river here while moving his army to Winnsboro in October 1780.

Retrace your route on S.R. 12-330 to the junction with S.C. 223, U.S. 21, and S.R. 12-70 in Landsford. Proceed west on S.R. 12-70 for 4.6 miles to S.C. 901, turn left, and drive south for 0.4 mile to S.R. 12-46. Turn right, go west for 2.9 miles to S.R. 12-32, turn right again, and head north for 2 miles to S.R. 12-50. Located here is the historic Fishing Creek Presbyterian Church and Cemetery.

Established in 1752, this church is housed in a much-altered brick building constructed in 1785. Like most of the Presbyterians in the upstate, the members of Fishing Creek were ardent Patriots throughout the war. They suffered great indignities and losses during the frequent warfare between Tories and Patriots in the area.

Many Revolutionary War veterans are buried in the adjacent cemetery.

A state historical marker for the church and cemetery stands nearby.

Turn left on S.R. 12-50 and drive 2.5 miles south to S.C. 909. Turn right and proceed 3.1 miles west to U.S. 72/U.S. 121. Continue west on S.C. 909 for 0.1 mile over the railroad tracks to the Lewis Inn. Now a private home, this dwelling was constructed in colonial times and served as an inn during the Revolution. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Continue on S.C. 909 for 8.5 miles to the junction with U.S. 321 and S.R. 12-29. Proceed west on S.R. 12-29 for 1.6 miles to S.R. 12-142, turn right, and go 2.7 miles to S.R. 12-521. Drive west on S.R. 12-521 for 4.2 miles to S.C. 97, turn left, and head north. It is 1.7 miles to the York County line. Continue north on S.C. 97 for 3.2 miles to S.C. 322, turn left, and drive 2.6 miles west to S.C. 49. Located here is Bullock Creek Presbyterian Church.

Organized in 1769, the congregation is now housed in its fourth building, which was built around 1953. During the Revolutionary War, Dr. Joseph Alexander served as the minister at Bullock Creek, and the church proved a Patriot stronghold. It is said that Dr. Alexander always took the pulpit with a loaded gun, ready for British or Tories.

His residence was located 1.5 miles southwest. When needed, it was used as a hospital during the war.

Dr. Alexander is buried in the cemetery adjacent to the church.

A state historical marker is located nearby.

Turn around near the church and drive east on S.C. 322 for 11.6 miles to U.S. 321 in McConnells. Continue on S.C. 322 for 2.4 miles to S.R. 46-165, turn right, and go southeast for 2 miles to Historic Brattonsville. An admission fee is charged to visit this wonderful assemblage of more than two dozen buildings on a twenty-five-acre site.

The restored village chronicles the life and times of the Bratton family, which played an important role in the economic, military, and cultural affairs of this area. A tour of the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century restoration site begins at the visitor center, located in the two-story Ingram-Montgomery House, built around 1840. While a full tour of the buildings and grounds is well worth the effort, three village sites are directly related to the Revolution.

To the rear of the visitor center is a backwoodsman’s cabin, a reproduction of the kind of log structures common in the area in the eighteenth century. The back-country people who took part in the Revolutionary War battles and skirmishes of the upstate lived in quarters like these.

From the cabin, walk west across the grounds to the home of Colonel William Bratton and his wife, Martha. This handsome frame dwelling bears little resemblance to the log structure Colonel Bratton constructed in 1776. It was remodeled to its present appearance in 1839 by Bratton’s son, John. The house is the oldest documented building in York County.

William Bratton (1742-1815), a native of Virginia, first became acquainted with upstate South Carolina as a trader using the local route to the Catawba Indian nation. On the eve of the Revolution, he and his wife settled at the current tour stop and built a large two-room log cabin on a high ridge between the Catawba and Broad River Valleys.

As soon as the fight for independence began, Bratton took up arms as an officer of the local militia. In the spring of 1780, these upstate militiamen were rushed to Charleston to aid in the defense of the port city. When Charleston fell, Bratton, then a major, came home to brace for the British invasion of the back country.

Described as a “short-necked, high-shouldered, small spare man,” Bratton did not have the physique of a mighty warrior. Yet when the threat of an invasion of his home territory became real, there was no stronger or more valiant Patriot. He was promptly promoted to colonel. Working with Captain John McClure, Bratton mobilized Patriot forces in the upstate.

On May 26, 1780, the Americans achieved a victory at Mobley’s Meeting House thanks largely to the leadership of Bratton and McClure. However, the debacle known as Buford’s Massacre (see Tour 18, pages 242–45) on May 29 took a toll on Bratton. In early June, Patriots gathered at Bullock Creek Presbyterian Church, where they were shocked to hear Bratton say that “any further opposition to the British would be to no avail.”

A few days later, his soldiers assembled with other area Patriots at William Hill’s ironworks to listen to an offer of parole and pardon by a British commissioner dispatched by Lord Rawdon. Just as it appeared that the Patriots were about to concede, William Hill stood up and offered words of inspiration about how General Washington was “in a more prosperous way” than he had been in some time. He spoke of Washington’s appointment of “an officer with a considerable army,” who were at that moment “on their march to the relief of the Southern states.”

His words renewed the fighting spirit in area Patriots. According to Hill, “There was a visible animation in the countenance of the citizens, and their former state of despondency visibly reversed.” It was just a few days later that Colonel Bratton resumed command of his militia and reported to General Thomas Sumter.

The renewed fighting spirit of Bratton and his men came at an opportune time, since Captain Christian Huck had begun his reign of terror in the upstate. Huck, a Tory who had come south as a part of Tarleton’s legion, set up a base at Rocky Mount in Fairfield County and initiated a series of raids throughout the countryside. His destruction of Hill’s ironworks and the library and manse at Fishing Creek Presbyterian Church in June 1780 sparked deep resentment among area residents. On the other hand, Huck’s British superiors were anxious for him to continue his successful campaign. Colonel William Bratton and Captain John McClure were placed on the wanted list.

As June melted into July, Huck was given specific instructions: “You are hereby ordered, with the cavalry, under your command, to proceed to the frontier of the Province, collecting all the royal militia with you in your march, and said forces, to push the rebels as far as you may deem convenient.” With this new license to wreck havoc on the people of the back country, the notorious captain set out from White’s Mill on an expedition of burning, plundering, and cruelty.

High on Huck’s list of places to visit was the plantation of Colonel William Bratton at the current tour stop. En route, he was delighted to capture the son and son-in-law of Captain McClure, who were arrested for melting pewter plates into rifle balls. Huck sentenced the two men to die by hanging.

On the evening of July 11, Huck and his 115-man band of Tories rode to the current tour stop, surrounded the house, and demanded to see Colonel Bratton. Martha Bratton answered the door and informed Huck that her husband was not at home. When asked his whereabouts, she indicated that he was with Sumter’s army, where she desired him to remain. When Huck asked the location of Bratton’s camp, Martha responded, “I have told the simple truth and would not tell if I could.”

Outraged by her impertinence, one of Huck’s men grabbed her and threatened to cut her throat with a reaping hook unless she provided the information. Taken by Martha’s bravery, Captain John Adamson, one of Huck’s junior officers, stepped in to save the life of the American heroine.

Convinced that he would gain no information about Bratton here, Huck moved his army to the plantation of Bratton’s neighbor James Williamson, located less than 0.5 mile away. There, he found that all five of the Williamson men were away with Colonel Bratton’s militia.

Meanwhile, the local ladies sent out messengers to warn the Patriots of Huck’s arrival. Martha Bratton dispatched Watt, a trusted family servant, to find her husband. Watt located Colonel Bratton at Fishing Creek, where the Patriot officer hoped to surprise Huck at White’s Mill. About the same time, Captain McClure’s daughter arrived with the report that Huck was at the plantation of James Williamson.

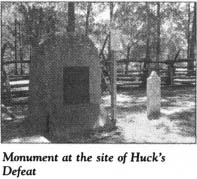

From the Bratton House, walk along the road toward the visitor center. En route, you will notice a large D.A.R. marker for the Battle of Williamson’s Plantation (also known as “Huck’s Defeat”). As soon as he was alerted of Huck’s location, Colonel Bratton put his army on the move. As he approached his own home, the Patriot commander was in desperate need of information about Huck’s camp. Suddenly, the Americans came upon Reuben Lacy, a blind Tory who had just visited Huck. Bratton proceeded to tell Lacy that he had become separated from his unit, Captain Huck’s command. Lacy thus unwittingly divulged details of the Tory encampment.

Around dawn on July 12, Colonel Bratton divided his ninety-man army as he approached the Tory encampment, where tents had been pitched between the rail fences along the road to James Williamson’s house. Those fences served to pen up the Tories and made them ripe for slaughter when the Americans attacked.

Bratton’s soldiers were within seventy-five yards of the Tory tents when reveille sounded. Suddenly, American muskets blazed. The fenced-in Tories could not reach their horses, nor could they charge with bayonets. Alarmed by the disaster that was unfolding, Captain Huck rushed out of the Williamson residence in an attempt to rally his men. He was killed instantly with a wound to the head.

When the slaughter was over, only two dozen Tories escaped. Among the badly wounded was Captain John Adamson. When Colonel Bratton came upon the fallen soldier on the battlefield, the Tory looked at him and said, “It is of little consequence to me, sir, for you can only hasten the end which, I feel, is fast approaching, but I beg of you to consult with Mrs. Bratton before you perpetuate so great a wrong.” Colonel Bratton spared Adamson, and upon Mrs. Bratton’s arrival, she identified the Tory as the man who had earlier saved her life. Adamson was taken to the Bratton home, where his wounds were treated.

One Patriot died that day.

Although the battle involved fewer than two hundred men, its effects were far-reaching. In Charleston, Tarleton was incensed by the apparent misuse of a portion of his legion, and his ill feelings against Rawdon and Cornwallis festered for the duration of the war. Conversely, the “small” American victory at Williamson’s Plantation and others like it helped General Sumter increase the size of his partisan army. Deeply concerned, Lieutenant Colonel George Turnbull wrote Lord Rawdon from the Tory post at Rocky Mount, “I find the enemy exerting themselves wonderfully and successfully in stirring up the people. … They have terrified our friends.”

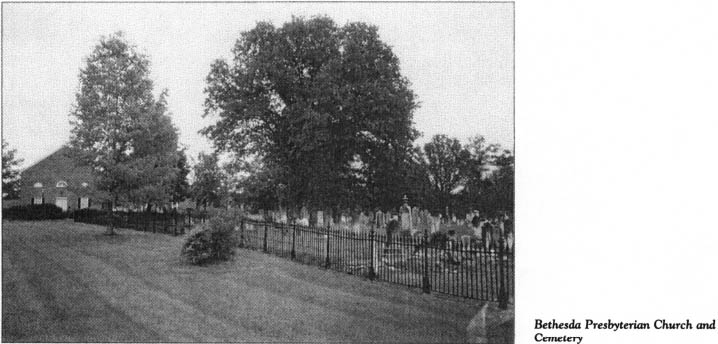

When you are ready to leave Historic Brattonsville, return to S.C. 322, turn right, and drive 1.3 miles northeast to Bethesda Presbyterian Church. A Presbyterian congregation came together here as early as 1760, but the church was not officially organized until 1769. The present church building, an elegant brick structure, dates to 1820. Among the Revolutionary War veterans buried in the adjoining cemetery is Colonel William Bratton.

Continue northeast on S.R. 322 for 0.5 mile to S.R. 46-347, turn left, and drive 1.1 miles north to S.C. 324. Turn right, go southeast for 9.5 miles to S.C. 72, turn left, and proceed 0.5 mile to S.R. 46-739. At this junction stands a state historical marker for White’s Mill. To see the site, turn right on S.C. 46-739 and follow it for 1.5 miles to the bridge over Fishing Creek.

White’s Mill stood here on this creek during Revolutionary War times. In September 1780, Banastre Tarleton and his legion camped at the mill for several days. During his stay, Tarleton was seriously ill with fever.

The tour ends here. If you wish to continue traveling in the area, you can combine this tour with the following one by returning to S.C. 72, turning right, and driving northeast for 6.7 miles to U.S. 21 in Rock Hill.