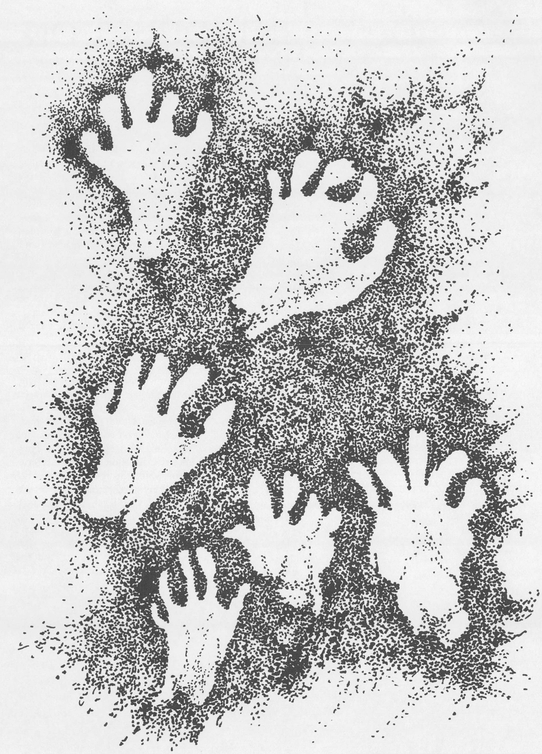

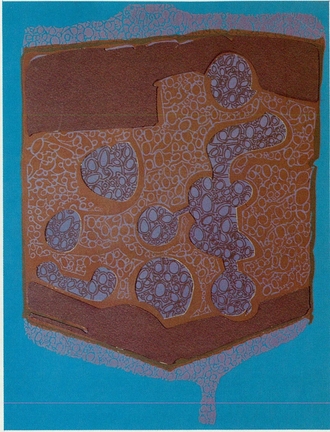

Fig. 1-1. The walls of Gargas Cave in the French Pyrenees are covered with records of prehistoric man’s culture. Shown here are negative prints of mutilated hands.

1. STENCILS—A SHORT HISTORY

In prehistoric times, when his castle was a mere hole in a hill, man left a visual record of his culture. On the walls of three caves—Gargas near Aventignan in the French Pyrenees, its small neighbor, Tibiran, and Maltravieso in the Spanish province of Estremadura—there are more than 200 prints of hands, most of them mutilated by sickness or accident. Their meaning can only be conjectured, but a close study clearly shows them to be a form of aesthetic expression. The idea of repetition, the feeling of rhythm that emerges from the images and the intervening space, and the horizontal alignment suggest a definite notion of artistic decoration.

These handprints are black (from the manganese deposits scraped from the walls of the cave) and red (obtained from ocher, a clayey earth colored with iron oxides). The positive prints were made by pressing a hand covered with color on the wall of the cave in the manner of a relief print. The negative prints (Fig. 1-1), which give the effect of a halo, were made by placing a hand on the wall and spraying the color over and around it. The color was blown directly from the mouth or, more likely, through a short piece of hollow bone. Thus spray painting, stencil printing, and relief printing were invented sometime around thirty thousand years before the birth of Christ. Man literally left his imprint on the wall of his cave to express symbolically and aesthetically his eternal needs.

The earliest stencils do not survive because they were made of leaves and skins and deteriorated rapidly. Some experts claim that the first stencils used by prehistoric man were some found in the Fiji Islands that were made from leaves from bamboo trees. When the leaves fell they curled up, and worms or larvae ate holes in them. Unrolled, they served as stencils for the primitive islanders to decorate garments with vegetable dyes. Later on these same islanders used heated banana leaves for cutting their stencil patterns, which they printed on a thin bark stripped from the malo tree.

Quintilian, in Italy during the early Christian era, was said to have taught children the alphabet by having them trace the letters through stencils. And several rulers living in the sixth century A.D. used stencil methods to attach their signatures to important documents.

In the Far East the Chinese and Japanese between 500 and 1000 A.D. developed the art of stenciling to a high level. Buddhism was rising in importance, and the faithful were encouraged to seek favor of Buddha by duplicating his picture as frequently as possible. This was best accomplished with a stencil. In the famous Caves of the Thousand Buddhas at Tun Huang, in western China, which was a strategic trade center and gathering place for Chinese, Turks, and Tibetans, one finds religious caves dug into the sandstone and extending for a half mile along the hillside. The walls of these grottoes are covered with images of Buddha. He is usually seated and sometimes surrounded by his faithful attendants. Some of the Buddha images are only a few inches high, while others tower 70 feet up the cave wall. A few are carved, but many are stenciled. Some, which are still unfinished, reveal the characteristic light-gray lines made by the thousands of little holes pricked in the stencil to duplicate the pattern.

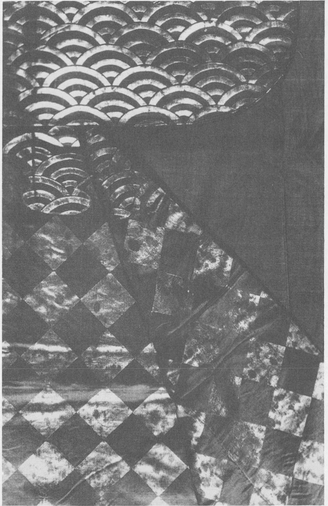

Fig. 1-2. Noh robe of the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, gold stenciled on red colored silk. (Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Robert Allerton)

Stenciled silks from China borrowed many symbols from the various religious faiths: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. The swastika, peacock, royal dragon, and conventionalized clouds and waves and various flowers shaded in the manner of embroidery also were stencil motifs. Since Chinese silks were much sought after in the Western world, it is probable that it was through them that the art of stenciling was introduced to Western cultures.

While not much is known about it, another method of producing a stencil was used in China in later years. An acid ink was used to draw or paint the design on stencil paper. The acid in the ink ate through the paper, leaving a clear-cut stencil.

In eighteenth-century Japan, which was closed to trade with the outside world, stencils were developed that might be described as the forerunners of today’s screen-process stencil. The highly skilled Japanese stencil cutters were able to cut extremely intricate patterns, but they were limited by the necessity of bridging the floating parts of the stencil. (The center island in the letter “O” is an excellent example of a floating part.) They soon developed a method whereby a varnish, called shibu, was painted over a single cut-stencil sheet. The stencil paper was often handmade from the fibers of mulberry leaves. Since the people were very thrifty, they sometimes used discarded documents for stencils, and some valuable records have therefore been saved that otherwise would have been lost. Fine threads of silk or human hairs were used to tie in floating parts to the main section of the cut stencil (Fig. 1-3). The varnish held the hair in place. Often the hairs were stretched in a crisscross grid pattern about one quarter of an inch apart. In extremely complicated stencils the thin threads were tied by hand or with a special hook. After all the floating parts had been secured with thin threads, a second identical stencil was cut, varnished, then placed over the first stencil, with the two varnished sides facing each other. This was dried under pressure, producing an extremely strong and durable stencil. The supporting threads were so thin that their effects could hardly be seen on prints from the stencils.

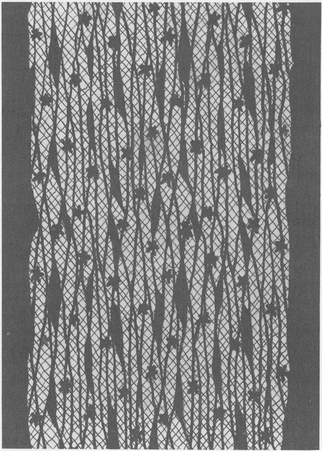

Fig. 1-3. In the Yuzen style of Japanese stencil production, developed in the eighteenth century, a grid of fine silk threads or hairs secures the floating parts of the stencil. (From the Helen Allen Textile Collection, Department of Related Arts, University of Wisconsin)

So now, for the first time, floating parts were held in place without the traditional bridges characteristic of earlier stencils. This process, called the Yuzen style by the Japanese, made possible new complexities in designing, but it was very tedious and difficult. Only the most skilled craftsmen could accomplish it. While it would seem to be only one easy step from this difficult grid system of fine threads or hairs to the use of an excellent grade of woven silk as the carrier for a stencil design, it was not until late in the nineteenth century, almost 150 years later, that this was done.

In Europe during the Middle Ages color was used on prints depicting various saints and on some playing cards. Wood blocks printed the basic design in black, and then the printer applied colors to these prints with very simple, crude stencils. Also, during this period, thousands of knights headed for the Holy Land and the Crusades needed red crosses on their clothing to identify them. The designers stretched a fine cloth made from hair over iron hoops from old wine casks. Pitch or ship’s tar was used as a resist to block out the areas that would remain white, and the red cross was printed through the unfilled parts of the cloth on clothing and banners. In this manner the red cross could easily be duplicated many times over.

No one knows at what early date Nigerians formulated their stencil methods. They use stencils to print portions of fabric with a starch made from the cassava root. These starched areas resist the characteristic indigo dye while the unstarched areas accept it.

In 1868, Owen Jones published Grammar of Ornament, one of the most important works on decoration published in the nineteenth century. It illustrated various styles of ornament and contained many color plates. By 1910 the book had gone through nine editions and had been responsible for a considerable change in the types of stencil designs wallpaper and textile designers were producing. William Morris, the great nineteenth-century designer who was responsible for a revival in the field of decoration, was greatly influenced by Owen Jones and his work. Many of Morris’s textile and wallpaper designs, though not directly copied from Jones, reflect his basic design philosophy, especially in the rich organic quality of decoration. The Art Nouveau of the late nineteenth century also owes some of its ideas to Owen Jones, particularly the strong feeling for growing things evident in Art Nouveau patterns.

Honors for the development of screen-process printing into a major craft must be given to the commercial printing industry and, in the United States, to the advertising and sign-painting industries. While there has been more activity in the United States in this century, it was in Germany and the Lyons district of France around 1870 that the pioneer work was accomplished. Here silk was used as the stencil carrier. The first recorded patent for the use of silk was awarded to Samuel Simon of Manchester, England, in 1907. However, Mr. Simon printed his stencils with a stiff bristle brush charged with color instead of the rubber squeegee so common today.

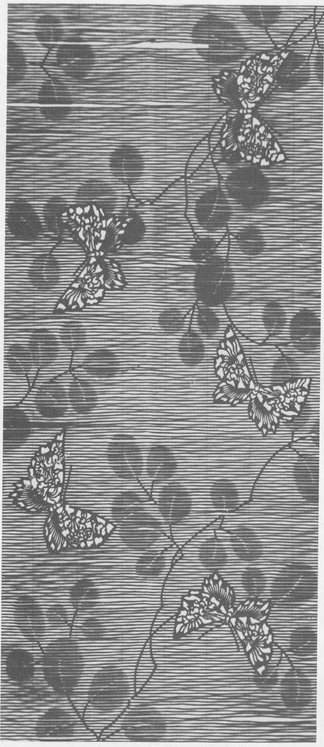

Fig. 1-4. An early hand-cut Japanese stencil. (Art Institute of Chicago, Frederick W. Gookin collection)

In 1914, John Pilsworth, a commercial artist from San Francisco, perfected a multicolor screen process called the Selectasine method, for which he was later granted a patent in collaboration with a Mr. Owen. Only one screen was used. Like reduction color methods in relief and process printing, the largest color area, often the background, was printed first. Then, part of the design was blocked out with glue, and it was printed again with a second color over parts of color number one. Then a still smaller area was blocked out and printed with a third color. This went on until the final print was finished.

It was the lively competition between commercial sign painters and small print shops that sparked the early development of the screen-process craft in the United States. For a time each firm jealously guarded its own variations as house secrets. But by the time the Screen Process Printing Association, International, was founded in 1948, this commercial printing process was public property and a rapidly expanding industry.

In the textile industry even before World War I, stencils made of cardboard and zinc were used, and the color was applied with stiff brushes. This method, called brush painting, was soon replaced by the spraygun, but the same kind of stencils continued to be used. Then France became the first country to use screen-process printing for textiles in the early 1920s.

The screen process was used at the time by sign-painting firms in the United States, where its initial great expansion was due to the formation of grocery chains. They needed many inexpensive signs, which had to be produced by local sign painters because they were changed frequently. Sign shops that went into screen-process printing were able to underbid the traditional hand-brush sign painters. However, the image produced by these early screen-process sign printers was crude, particularly along the edges of the color areas. Because of this, the more polished letter-press and lithograph industry continued to make signs.

In 1925 the automatic screen-process printing machine was invented, which made it possible to print faster than the ink would dry. Unfortunately, the industry was not large enough at this time to induce paint manufacturers to produce fast-drying inks for screen printing. In 1929 a screen printer in Dayton, Ohio, Louis F. D‘Autremont, developed a knife-cut stencil-film tissue that gave a print a clean, sharp edge. No longer was the crude, ragged edge a characteristic feature of the screen print. This new film was patented by an associate of D’Autremont, A. S. Danemon, and sold under the commercial name of Profilm. The film was improved upon a few years later with the introduction of Nufilm, which was the invention of Joseph Ulano. It was easier to cut, adhered more easily to the silk, and therefore saved considerable time.

With the invention of Profilm and Nufilm the craft boomed. It was large enough now to be attractive to paint manufacturers, and many different kinds of paint were especially produced to be used in screen printing. With faster-drying inks, the automatic printing machines were further developed and took over most of the industry. Today these machines and the new inks can produce 2,000 to 3,000 impressions an hour.

During the early 1930s, the opening of Rockefeller Center in New York created a design sensation. It was the birth of another important style, which today’s design historians refer to as Art Deco. It was a form of decoration that had its major roots in Cubism, American Indian crafts, and Egyptian design motifs. It found its first great expression in the decorative patterns in Radio City Music Hall, and it greatly affected the character of the textile and wallpaper designs produced by screen-process printers during the 1930s and 1940s.

Although the photographic process in screen printing has not been extensively used until recently, the original experimentation dates back to the late nineteenth century. Some of the principles were first developed in England by such men as Mongo Ponton and Sir Joseph W. Swan, working mostly in the printing of textiles and wallpaper. Since 1914, in the United States, there has been a similar active development of photographic screen-process printing with about twenty different photographic screen-process plates having been developed.

Why, with all this feverish and rapid development in the screen-process industry, was the fine artist so slow in picking up the medium as part of his expressive vocabulary? It was due partly to the secrecy prevalent in the commercial screen industry and partly to the natural suspicion and distaste that many artists have for anything so predominantly commercial as was the industry. This lack of interest must also be explained by the fact that artists before the 1930s showed little interest in any of the graphic-arts processes.

Credit for the development of screen-process printing as a fine-art medium belongs to two men, Anthony Velonis and Carl Zigrosser. During the 1930s the great Depression sparked the formation of the WPA Federal Arts Project. A separate silk-screen unit of this project was set up in New York under the direction of Anthony Velonis. Early artists working in this area were Guy McCoy, Hyman Warsager, Edward Landon, Elizabeth Olds, Harry Gottlieb, Mervin Jules, Ruth Gikow, and Harry Sternberg. In 1938 the first one-man showing of silk-screen prints was held at the Contemporary Art Gallery in New York with the works of Guy McCoy. In the March 1940 issue of Parnassus magazine, Elizabeth McCausland reviewed McCoy’s exhibition and wrote: “There is an exciting historical portent in the speed with which the silkscreen color print has captured the fancy of contemporary graphic artists.”

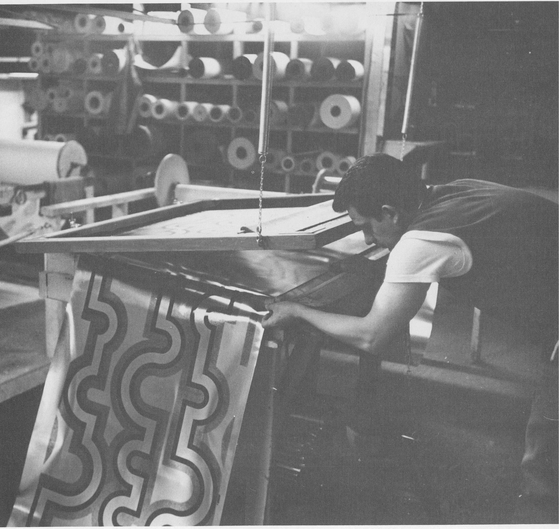

Fig. 1-5. Wallpaper printing at Jack Denst Designs Inc., Chicago.

But recognition for this new artistic medium was not automatic. Major credit for interesting the artist, the public, and particularly art collectors, museums, galleries, and art critics must go to Carl Zigrosser, eminent curator of prints of the Philadelphia Museum of Fine Arts. To distinguish the fine-art product from that produced by the screen-process industry, Zigrosser coined the term serigraph (seri means silk in Greek and graph means to draw). This term has since been generally accepted by screen-print artists. Albert Kosloff, at the end of World War II, attempted to give the screen-process print produced by the industry the term mitograph (from the Greek prefix mitos meaning threads or fibers and the suffix graphein meaning to write or draw). He reasoned that many other materials are used in contemporary screen-process printing as the carrier for the stencil besides silk—cotton, linen, nylon, organdy, copper, brass, bronze, and stainless-steel fibers. However, by then “silk-screen print” had been abandoned by the industry in favor of “screen-process print,” which continues to designate the commercial product today.

Another major force in the development of serigraphy as a fine art was the formation in 1940 of the National Serigraph Society. It has set standards of excellence and has sent hundreds of exhibitions of its members’ work to countries all over the world. These exhibitions are responsible for a good deal of museum interest in the purchase of original prints as part of museum collections.

Before the development of the massive automatic machines for the screen-process printing of textiles, commercial textile-printing firms printed their stencil repeats with an airbrush. Hard paper and even copper stencils were cut, laid on the fabrics, and the designs airbrushed. This method made delicate color gradations possible. However, it was a slow and costly method and has been replaced by speedier machine screening.

Recently, a form of stencil printing using painting brushes has reappeared. The process, known as pochoir, was used in France years ago for making stenciled reproductions of fine paintings, especially watercolors and gouaches. It is particularly useful, in the hands of a skilled technician, for the accurate reproduction of watercolors because the printing medium is a brush and fine artist’s grade watercolors. The color is simply painted through the cut stencil, and usually a screen frame is not used. A few artists have recently experimented with pochoir for the creative production of original prints.

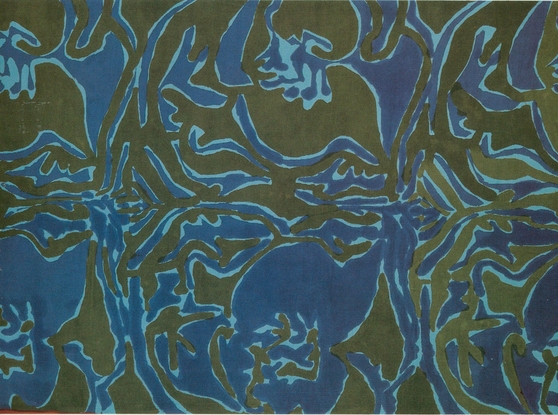

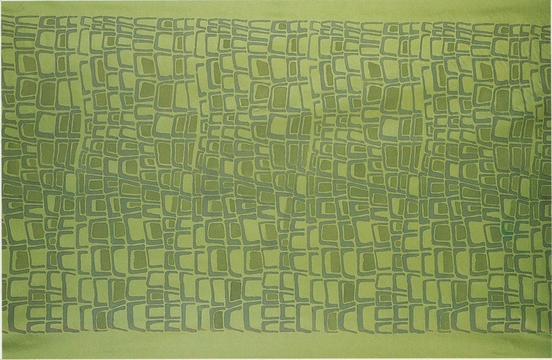

Unlike the format of regular repeats established historically by wood-block printers, the large fashion prints that appeared in the 1960s were free and seemingly at random (Fig. 1-6). The repeats are so large and the prints so complex and irregular that one’s eye is kept moving over the fabric. The problem of printing each repeat in exactly the right place is minimized. Other contemporary prints are often engineered precisely for the way the cloth will be cut in the manufacture of a specific garment, with no repeats at all. Any change in the printing would spoil the style and render the fabric useless for that particular garment. This coordination of the printed design and the finished piece of clothing is very helpful in the garment trade and is practiced in the fashion industry.

Helen Giambruni says in the May/June 1968 issue of Crafts Horizon magazine, in an article titled “Color Scale and Body Scale”: “It should be remembered, however, that simplification of shape in clothing design preceded the print revival [of the 1960s] and, indeed, was probably one of its causes; shift-type dresses almost demand the use of prints for variety.”

Another new technique, called Ambiente, for printing by use of machinery, has been developed by Timo and Pi Sarpaneva of Helsinki, Finland. Details of the method have not been made public, but the pattern is printed on both sides of the fabric. Any fabric can be used, and the patterns we have seen suggested free, brushed, expressionistic stripes or waves, either horizontal or vertical, that blended into each other in an almost unlimited range of colors.

The textile industry has found that screen prints have an advantage over the faster roller printing of textiles because screen colors penetrate the cloth much more deeply This results in the brighter colors that became quite popular in the 1960s.

During the final years of our century we can expect such innovations in textile printing as paper-transfer printing, a heat-applied paper transfer with thermoplastic inks.

While the fine art of serigraphy has assured itself an important place in the history of art, it is probably too soon to evaluate its real consequence. This is also true of screen-process textile printing. However, one thing seems certain. The extreme versatility of the medium has opened completely new possibilities for design and expression to both the serigrapher and the textile designer, and the inexpensiveness of the equipment needed for small printing has also encouraged experimentation in design.

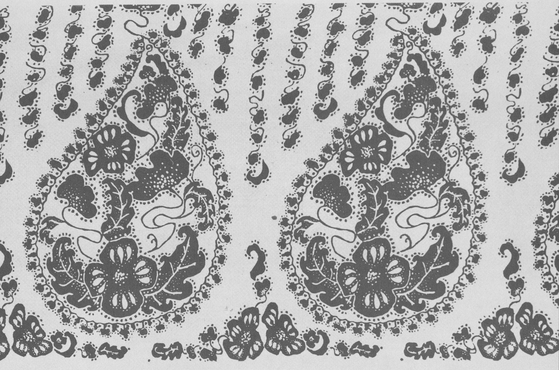

Fig. 1-6. Entitled “Paisley,” this large random design is screen-printed on dotted swiss. (By Sue Palm)

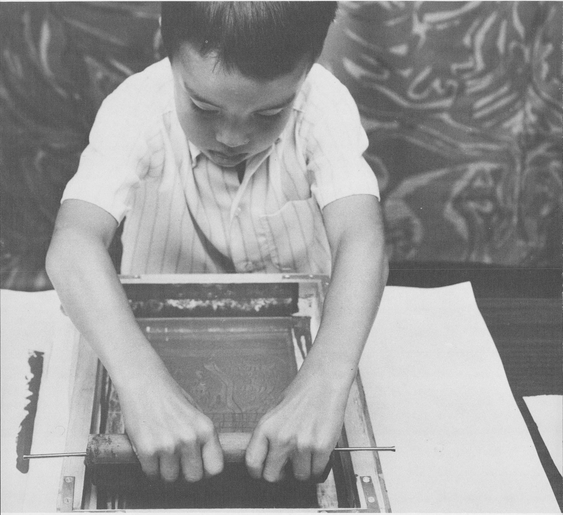

Fig. 2-1. This youngster produced the design he is printing by painting the resist directly onto the screen with fingernail lacquer.

Fig. 1-5. (See Frontispiece.) The design for “Simple Grace” was screen-printed on fabric and then painted. (By Irene Naik)

Fig. 2-7. (See pages 19 and 20.) The design for this serigraph, entitled “David’s Shield,” was drawn on transparent acetate and exposed on a light-sensitive emulsion resist. (By James A. Schwalbach)

Fig. 2-8. (See pages 19 and 20.) The fiber-reactive dye pastes used in this fabric print are easy to prepare. The designer has painted free, expressive lines after screen-printing the basic design, and where the two merge new colors are created. (“Purpled Scarf,” by Irene Naik)

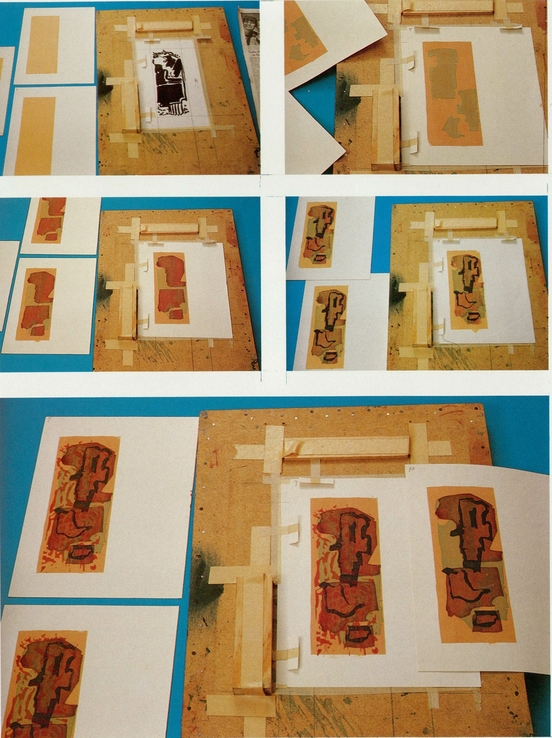

(See pages 32 and 33.) The final steps in a print for the beginner.

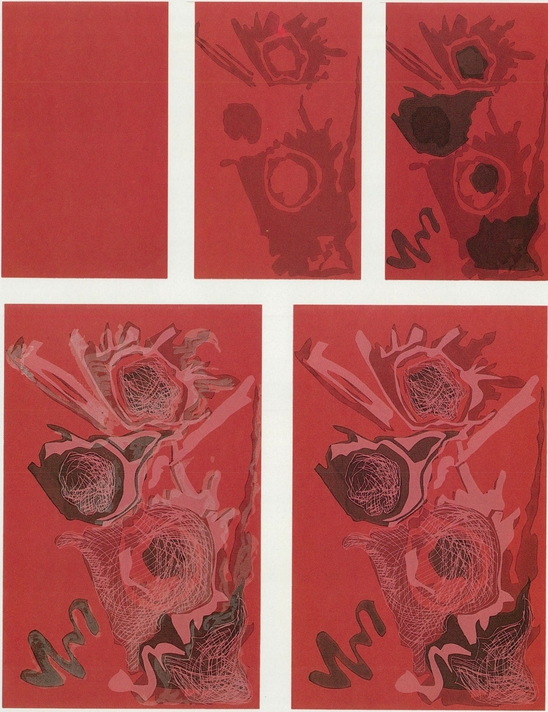

Fig. 4-41. (See pages 52 and 53.) This progression shows what the serigraph looks like after each of the five colors has been added.

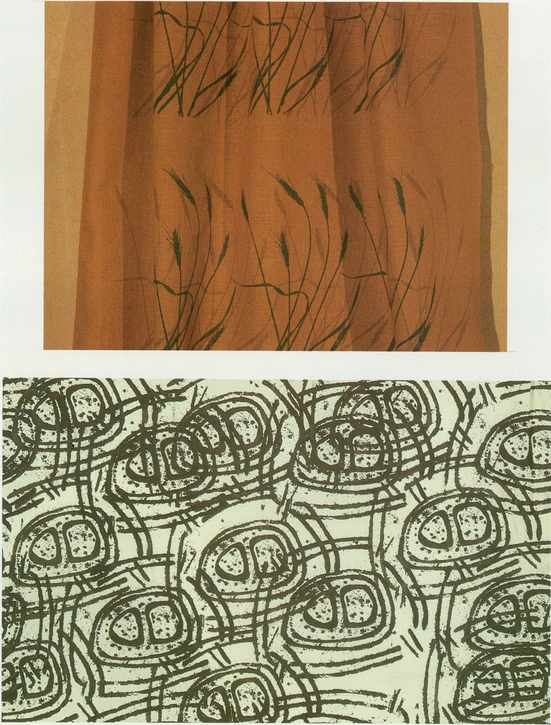

Fig. 5-13. (See pages 64 and 65.) Two strikingly different effects are achieved in basically the same way. Seed pods, dried stalks of grain, and cut paper were used to make the designs on light-sensitive resists, and overlapping in the printing process built up the pattern sequences. (Top, by Barbara C. Knollenberg; bottom, by Patricia Zuzinec)

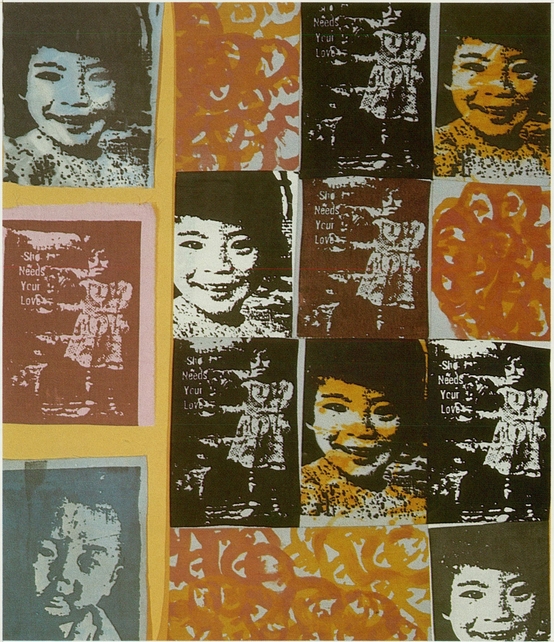

Fig. 6-12. (See pages 88 and 89.) Textile pattern composed of images in a light-sensitive film stencil made with a dry-copier transparency from current press cuttings produces a social commentary banner. (By Bobette Heller)

Fig. 7-14. (See page 105.) This textile print was produced by discharging color from the fabric with a stencil. (“Morning Snow,” by Timothy J. McIlrath)

Fig. 8-5. (See pages 124 and 125.) Light-sensitive emulsion resists were used to make two very different designs, one a textile print entitled “November Feathers” and the other a serigraph called “Signs of the Times.” (Textile, top, by Mathilda V. Schwalbach; serigraph, bottom, by James A. Schwalbach)