2. WHAT IS SCREEN PRINTING?

When Johnny places his jam-covered hand on the door of the refrigerator, Johnny is printing. And it is a form of printing that is the major concern of this book. Modern screen-process printing is merely a much more sophisticated method. It really is a contemporary but distant relative of both the ancient handprints on the walls of Gargas Cave and Johnny’s jam print.

Four Different Types of Printing

Printing can be divided into four basic types: relief, intaglio, planographic, and stencil.

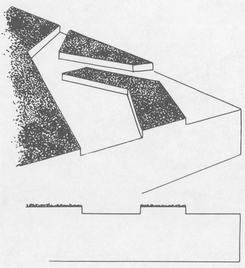

Relief and stencil printing are the oldest forms of printing. Along with those stenciled handprints on the walls of Gargas Cave, you will remember, there were handprints made by covering the surface of the hand with paint and then pressing it on the wall. The images in relief printing stands out on the surface of the printing block. This raised surface (Fig. 2-2) is then coated with ink and pressed on paper or fabric, and the image is printed. Newspapers, many magazines, linoleum block prints, and woodcuts are printed by means of relief printing. Fabrics are printed with linoleum or wood blocks and also with large roller presses that use wooden or copper rollers. This is a very common way of printing fabrics, and it too is relief printing.

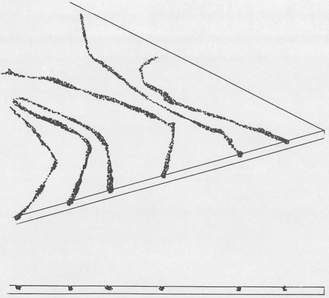

Intaglio (pronounced in-tal-yo) printing is not quite so ancient, but it has been around for quite a while. When Rembrandt van Rijn printed one of his famous etchings, he used the intaglio process. The image to be printed is scratched with a needle or eaten with an acid below the surface of the printing plate. Ink is rubbed on the surface and worked into the fine etched or scratched line (Fig. 2-3). The surface of the plate is then wiped clean, but just as with the dirt around fingernails, it is almost impossible to wipe the ink out of those fine lines. The plate is then placed under a damp piece of paper and pressed very hard in a special etching press. Because of the pressure of the rollers and the softness of the damp paper, the paper is actually pressed right down into the troughs where it sucks up the ink, producing the print. One way to tell an intaglio print is to run your finger over the paper just a little outside the image area. You will find a slight ridge where the damp paper has been forced down over the outside edge of the printing plate. Some early fabric prints (toile de Jouy) using very fine lines were engraved on copper plates and printed by the intaglio method.

Fig. 2-2. In relief printing, ink on the raised sections of the printing plate is transferred by means of pressure to the surface being printed.

Fig. 2-3. In the intaglio method of printing, ink in the etched troughs of the printing plate is transferred with great pressure to the surface of the print.

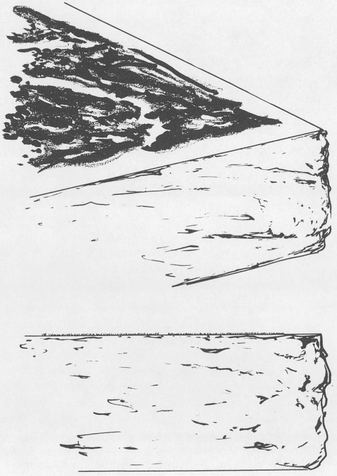

Fig. 2-4. In planographic printing, the surface of the printing plate is flat. Sections to be printed are covered with a greasy substance to which ink adheres and the rest of the surface is dampened with water, which repels ink. The image is then transferred to the print surface.

Planographic printing is more commonly known as lithography. The printing image is neither raised in relief nor cut into the surface of the plate but is a treated area of the surface. It works on the principle that water and grease will not mix but will resist each other (Fig. 2-4). The design is drawn or painted on the surface of a finely ground block of limestone—many commercial printers today use especially prepared metal plates—with a black greasy crayon or black greasy paint. The stone is then treated with gum arabic and nitric acid and dampened with water. When a large ink-charged roller is passed over the stone, the ink sticks to the greasy parts and is repelled by the wet areas. It is then put into a special press and printed. Many illustrations in magazines, posters, and children’s books are printed in this manner, and some efforts have been made to print fabrics using this process. Photo-offset is another form of lithographic, or planographic, printing that is commonly used commercially.

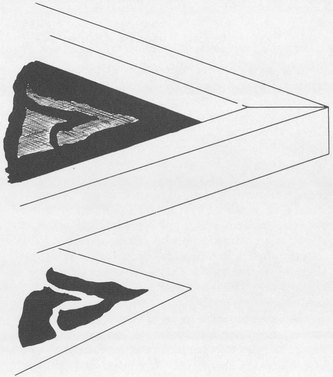

Stencil printing (Fig. 2-5) is as old as relief printing. The image is actually cut out of a thin material called a stencil, and printing ink is forced through the holes onto the surface to be printed. The screen-process method that is the subject of this book is an important form of stencil printing.

Fig. 2-5. in stencil printing the ink is forced through holes in a material impervious to the ink (top) onto the surface being printed (bottom).

The screen-process stencil is an impervious material supported on a woven mesh (silk, linen, organdy, cotton, nylon, copper, bronze, brass, and stainless-steel fibers) tightly stretched on a rectangular frame. The secret of the process is that the stretched material both supports the stencil and prevents the semifluid paints or dye pastes from flowing easily through the stencil holes, yet when pressure is applied by means of a rubber squeegee pulled back and forth over the stencil, the paint or dye is forced through the woven mesh to produce the printed image.

The Screen-Process Print

Screen-process printing possesses amazing versatility. It is simple enough to be used by a child. It requires no elaborate workshop, no expensive presses, no unavailable inks or tools. In its rudimentary forms it can be easily and quickly mastered by an elementary-school class.

Fig. 2-7. (Reproduced in full color between pages 16 and 17.) The design for this serigraph, entitled “David’s Shield,” was drawn on transparent acetate and exposed on a light-sensitive emulsion resist. (By James A. Schwalbach)

Fig. 2-8. (Reproduced in full color between pages 16 and 17.) The fiber-reactive dye pastes used in this fabric print are easy to prepare. The designer has painted free, expressive lines after screen-printing the basic design, and where the two merge new colors are created. (“Purpled Scarf,” by Irene Naik)

Yet, both the professional and the amateur who wish to explore the process in some depth will find it a rewarding challenge. It will print on almost any surface (glass, wood, paper, canvas, leather, fabric, stone—anything firm enough to hold the ink). While generally used on a flat surface, screens can be constructed to print on curved, round, or irregularly shaped forms. It is a portable process, and the frames can be moved wherever the artist chooses.

Screen printing allows the artist such a wide range of creative possibilities that it has become the most personal of all the printing processes. It inhibits the artist less than any other. The evolutionary growth of the printed image is completely under his control at every step. And contrary to all of the other methods of printing, it does not require him to make the mental translations of a reversed image.

He can make prints almost any size he wishes. He has at hand an extremely wide range of printing inks and dyes, either transparent, opaque, dull, shiny, or fluorescent. Some dry in minutes; others take hours. It is possible for him to build up textures and layers of paint so that he can achieve surfaces rich with color nuances or clear, cool, and flat or rhythmically calligraphic. They can be as fresh as a brush stroke that has scarcely dried. He can suit his approaches to a free, even abandoned and intuitive method or one as carefully controlled as a well-disciplined soldier. Many artists feel that screen-process printing is as versatile and personal as oil painting.

The stencil itself can be a very simple blockout scrubbed in with wax crayon by an eight-year-old child (see Chapter 3) or a very sophisticated halftone photographic image. The operation is basically small and simple, suited to a one-man kitchen-studio approach. But it has also become one of the giants of the commercial printing industry. (Large, complex, and automatic screen-process printing machines turn out 2,000 to 3,000 impressions every hour, all dried and neatly stacked, ready for packaging.) It prints articles as varied as advertising materials, banners, sweat shirts, dials for scientific instruments, electronic circuits for radio and television sets, labels on soda-pop bottles, designs on ceramic dishes, reproductions of oil paintings, yardgoods, wallpaper, and highway signs.

The Serigraph

To the professional or amateur artist, screen-process printing means the production of serigraphs, or original prints made by the screen-process printing method and produced by an artist after his own design for his own purpose.

In 1964 the Print Council of America defined an original print as follows:

“An original print is a work of art, the general requirements of which are: (1) The artist alone has created the master image in or upon the plate, stone, wood block or other material for the purpose of creating a print. (2) The print is made directly from the said material, by the artist or pursuant to his direction. (3) The finished print is approved by the artist.”

When an artist makes a serigraph, he usually prints a definite number that he has decided in advance, or an edition of serigraphs. These are duplicates or near duplicates of the same master stencil. How precise the duplication is, is up to the individual artist. There will always be some variation among the prints in any one edition. However, a print that differs considerably from the others is not included in a signed edition. It may be saved and gain value as a unique print, especially if it is a good one. Occasionally an artist holds on to prints produced during the evolution of the edition. These generally differ somewhat from the edition and are either destroyed or labeled “proof prints.” Prints that do not come up to the standards of the artist are also destroyed.

Screen-Process Textile Printing

When you think of the quantities of fabrics printed by large textile plants that specialize in roller printing, you might be tempted to qualify all fabrics produced by the screen-process method as fine art. Yet there are many large manufacturers that use semiautomatic screen-process printing machines to print rather large quantities of fabric. Since many of these employ excellent designers, the fabrics are hard to distinguish from the product of a small hand-process studio. But both have an advantage over the much larger roller-printing industry. In screen-process printing there is more penetration of the color into the fibers of the fabric, which results in stronger, more vivid colors. Also, the screen-process industry, especially the smaller workshops, can afford to be a little more experimental and daring. They generally have lower investment in equipment and print smaller runs that involve a lower market risk. Many of the smaller workshops specialize in high-quality fabrics of distinctive design for such specialty markets as high-fashion apparel construction.

It should be mentioned that the printing of better wallpaper is similar to screen-process fabric printing, and most of the information in this book concerning fabrics applies equally to wallpaper.

Basically there are three methods of printing a design in or on a piece of fabric: direct, discharge, and resist. In the direct process the color is printed directly through the holes in the process stencil onto the surface of the cloth. In the discharge process the cloth is dyed before it is printed. A paste containing a bleaching agent is then printed on the cloth through the holes of the process stencil. This bleach paste selectively bleaches the dyed cloth, producing a design that is lighter than the dyed cloth. The resist process is somewhat similar to the discharge process. A specially prepared paste is printed on the cloth through the holes of the process stencil, causing the printed areas to resist dye. The cloth is then placed in a dye solution. The design is also lighter than the dyed background.

Fig. 2-6. Stretching a screen fabric on a printing frame is tricky. The screen must be very tight so that no sags can develop.

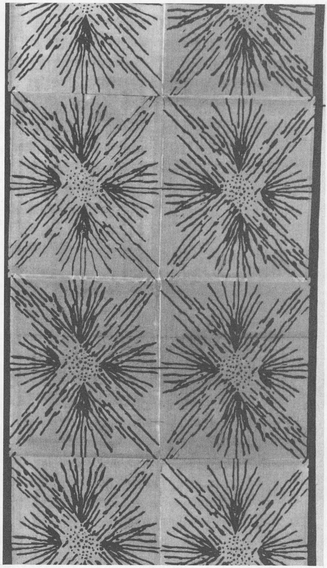

Fabric design presents an entirely different problem from that facing serigraphers. Fabrics are usually continuous lengths of cloth, and the design must continue as long as the cloth does. Therefore the design must work visually in all directions, or at least in two directions. Often a unit of a design that is to be repeated looks one way when it stands alone, but when it is repeated in one or more directions, it takes on an entirely different character. Certain parts of the unit that do not predominate (these parts frequently are near the outside edges of the unit) will join forces with sympathetic parts in the next unit and gain strength in the union. This can produce either a very dynamic design or one that falls apart because of conflicting forces.

Movement or rhythm produced visually is a very important part of textile design. Some interesting analogies can be made with music. In music there is a repetition of simple motifs of sound as there is a repetition of single visual motifs in fabric design. This will cause certain configurations of sound in music and certain configurations of pattern in fabric design. This unifies the pattern into a continuing design that is the lifeblood of the entire product and gives a vitality to the design that is difficult to get in a more static art.

Another musical analogy can be made. Music is performed by different individuals, and therefore there are slight variations from one performance to another as each musician interprets the sound configurations of the composer. A somewhat similar thing happens in the hand-printing of a fabric design. For no human being can work in exactly the same way each time he prints one of the design units on the fabric. The pressure of the squeegee is changed slightly; the paint is changed slightly in hue or consistency; the screen is placed a very small fraction of an inch out of line. These add a personal touch to the configuration planned for the design and a vitality that one cannot find even in the screen-process prints produced by semiautomatic machines and that certainly is absent in roller-printed fabrics.

It is the interesting, creative textile printer who carefully and deliberately seeks such a random effect in the printing process. Often certain changes of color can be made as each unit is printed. This must be done with great sensitivity, for it is usually only one small step away from catastrophic disorganization and aesthetic failure.

The fabric designer is also presented with an unknown that can easily complicate his problem. The appearance of the printed fabric as a dress or draperies is usually far different from its appearance on the printing table. Fabrics are all printed flat but hardly ever used flat, and a design must be able to follow the folds and drapes of the materials and still maintain its quality. If the design is to be cut apart, rearranged, and pieced together into clothing, creative and careful planning is called for. Many fabrics are used as support or background for other activities. A tablecloth, for example, is designed to protect the table and to make the meal more pleasant and possibly even more palatable. A tablecloth design that competes with the meal and dishes might be a most unhappy one.

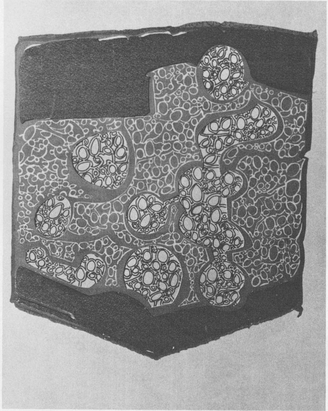

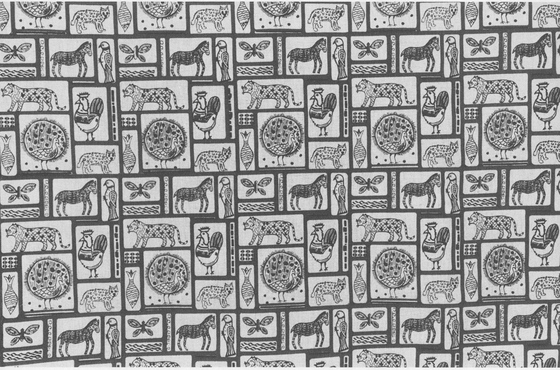

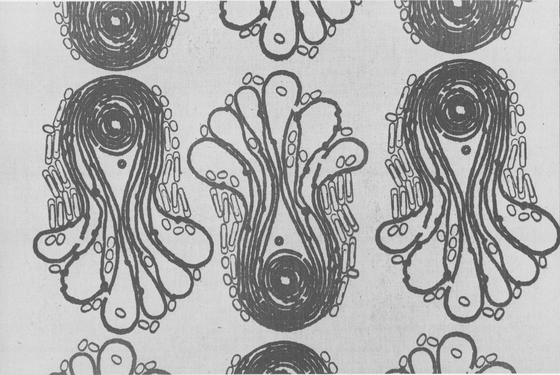

Fig. 2-9. A scooper cutter, or scratch tool, is a versatile instrument in making a cut-film stencil. The fine lines in this fabric’ print inspired by Pennsylvania Dutch designs would be very difficult if not impossible without such a tool. (“Zoorama,” by Alta Hertzler)

Where Do You Get Your Ideas and What Do You Do with Them?

While screen-process printing may be fun and recreation, do not count on it and do not seek this from it. For any serious pursuit of a creative process requires concentration, absorption, and intensity of purpose. It is a job that requires full creative and intellectual attention. What started out in fun may turn out to be blood and sweat if it is to amount to anything worthwhile. There is no magic way to do it. There is no doctrine. Success lies in being flexible and trying different approaches, methods, and ideas. All we can do is suggest some ideas that might start your thinking in a useful direction.

Basically there are two different ways that you can approach the design problem in screen-process printing. You can work intuitively, feeling your way, allowing the material and the process to suggest what to do next. This is an attitude that well suits the personalities of some designers. It gives you a chance to make use of happy accidents, providing, of course, that you are sensitive and knowledgeable enough to recognize a happy accident when you see it. Many designers are disturbed by any kind of accident and cannot differentiate between the unfortunate and the fortunate ones. The intuitive approach is probably a good one for most neophyte screen-process designers to take because it tends to keep your ideas more compatible with the process. Your final print is more likely to be suited to the screen process if you let the process dictate the major directions the design should take. However, when designers work intuitively there comes a critical moment when the seeming chaos must be organized into some kind of valid, clear statement. Some control must be exercised at this point. Many designers do not recognize this moment until the design has become hopelessly lost. Others find themselves incapable of exercising the control necessary to solidify the design.

After some experience with the materials and tools, most (but not all) designers work best if they get some sort of a general notion beforehand about the design they would like to produce. This can be done with sketches. If he wants, the designer can break up a sketch into its various color components and paint each one on different pieces of clear acetate or tracing paper. These then are placed over each other, and some approximation of the final design can be visualized. Changes will suggest themselves even before the printing begins. Generally it is better to simplify designs rather than complicate them. But however the sketch appears, it can only approximate the final print. The designer must be quite willing to make changes, even drastic ones, as the print evolves.

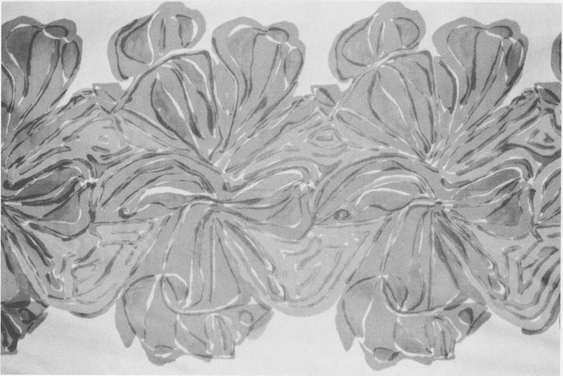

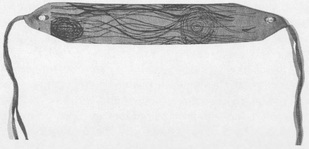

Fig. 2-10. The hairband above is printed with chiaroscuro made with a film line cutter (scooper cutter or scratch tool) in Profilm. In the radiating motif below, semitransparent white ink is printed on dark fabric with a lacquer stencil. The artist designed the pattern with free brush strokes of lacquer applied directly to the screen fabric. (Hairband by Joy H. Dohr; radiating motif by Gretchen Widder)

Serigraphers will need to think of the total area within the design unit. It is easy to think of the positive forms that are printed, but we tend to forget negative unprinted space around and behind these positive forms. This is an equally important part of the visual statement and should be given equally careful consideration. A good screen print allows the background to take shape and become an integral part of the motif. In addition, fabric designers should use acetates, tissue paper, or carbons to repeat their design units in as many different directions as is necessary in order to get some idea how the units will interrelate and how the visual statement will be affected by that interrelation. Units can be interconnected with many devices, a few of which are: (1) a side-by-side continuous pattern; (2) sinuous and expressive lines that extend from one unit into the next in one or more directions; (3) negative space that creates a similar directional fluidity; (4) notches from one irregular unit that carefully fit into reverse notches in the adjoining irregular unit. Connections may need to be both vertical and horizontal in fabric designing. Often a rhythm or concealed beat can be injected into a fabric design by carefully created breaks or fractures between the various units.

But besides form, line, and texture, screen printing is most importantly an expression in color, and color experience can be gained only in the process of printing. The material on which the color is printed has a great deal to do with the final effect of the color. The amount of opacity and transparency of each color used is also critical. Since certain effects can be achieved by overprinting colors, most of the colors used will have certain qualities of transparency and each color can be evaluated only after it has been printed over the color underneath.

Fig. 2-11. Knotted yarn, paper clips, and small rubber bands were used to create this design. To make the resist the artist arranged these objects directly on a light-sensitive emulsion and exposed the emulsion. (By Mathilda V. Schwalbach)

Man can consciously and intuitively control his visual forms, and much can be learned from his environment, particularly his natural environment. For in nature there is an inexhaustible resource of ideas. Serious designers should carry small sketchbooks with them for recording ideas, for both serigraph and textile-design ideas have a habit of unpredictable genesis.

Because of the prominence of the camera in our contemporary experience and because of its heavy use in television, our society is becoming more and more visually oriented. So the younger you are, the more visually acute you probably are.

A successful designer or artist is able to individualize his visual language. A Paul Klee is a marvelous colorist and a witty and delightfully surprising designer . . . an Henri Matisse is bold and strong in his flat color abstractions . . . a Piet Mondriaan is orderly and meticulous with his geometric patterns . . . a Ben Shahn is socially perceptive and both witty and caustic in his calligraphic line quality. But no one else has been exactly like any of them, and no one will be exactly like any successful fabric designer or serigrapher. His visual signature will be recognizably his own. This is the very difficult but necessary goal that the serious designer must set for himself. It comes only after long experience and many trials and errors in a never-ending search.

The Possibilities and Limitations of Materials and Tools

New ideas and new techniques are always thrilling and exciting, and it is natural that the first thrills and experiences in screen printing will be related almost completely to techniques, tools, and materials. This stage must be passed through as quickly as possible, for it is not until the technique of the craft becomes second nature that any significant prints or designs are likely to result.

Each craft and art form has its own peculiar attributes and limitations. Screen-process printing is no exception. But there is no way that anyone can give you an understanding of them. There is an experience that must be and can be acquired only by working with the materials, tools, and processes involved. Work must be extensive enough to make experience intuitive. It must become second nature. It must become an easily functioning part of the designer’s creative vocabulary.

The major materials are paper and fabric, paint and dye. Both are different from each other and different from anything else. Paper is flat and usually white and smooth, but not always so. Fabrics have a peculiar flexibility that must be understood and used. Rarely does a serigraph look like a fabric or a fabric like a serigraph.

The whole study of dyes and paints is a gargantuan task that certainly is beyond the scope of any individual printer. But minimum characteristics of the visual and chemical reactions must be learned. It is exciting when a serigrapher or fabric designer sees what happens with his first color overprinting. What unexpected variety there is in the ways colors will dry as they are printed on different surfaces with varying degrees of penetration.

When the serigrapher or fabric designer knows his process well enough to be able to anticipate its actions, then he can really begin to design intelligently and significantly.

Significant Expression Relates to a Living Contemporary Culture

The humanist philosopher, Kenneth L. Patton, in Man Is the Meaning, said: “His [man’s] body is the bed of a stream through which flow the many waters of his world and his race. A man is many wires strung in the wind, and he must sing the song of the air that flows over him.” Meaningful expression grows out of the culture in which it is rooted. This has always been understood by artists and designers of significance.

Today swift communication and transportation have shrunk not only our world but our universe as well. The electron microscope and other scientific marvels have given us fresh new looks at our environment. We are becoming more conscious of social and political inequities —of injustice and human strife. François Bucher, in his book, Josef Albers: Despite Straight Lines, stated: “Rapid motion within seemingly stable systems has changed our daily way of life as well as our inner imagery. We sit in a car or in a plane while the landscape slips by. Rocks change their shape, rivers and roads change their course relative to our eyes. Façades rise while we approach, recede and decline while we go by. Matter, the matrix of being, has become a function of energy and its dynamic and infinite transformations.”

Man has always spoken of his culture through the arts, and relevant serigraphy and textile design will continue to be responsive to these cultural forces. There are also social implications to creative activity, especially that kind of creative studio experience that involves more than one person. For within the necessary freedom of the creative studio environment, true individualism can flower only in an atmosphere of sensitive mutual respect and understanding of each individual’s efforts. The artist must learn the difficult procedures of both self- and group evaluation, for without continued scrutiny and evaluation no progress is possible. There is a kind of freedom of expression that can be practical only within the social and utilitarian demands of a group studio experience, and it is a very healthy experience psychologically for the participants.