9. HANDLING THE COMPLETED PRINT

An artist should always be proud of what he has produced. To create is not to re-create. To produce serigraphs and printed textiles as personal therapy is not to be condemned or prevented, but it is not the goal of one who would be an artist. An artist must take a few yards of woven fabric or a piece of paper, both more or less ordinary, and make them extraordinary. At least that is what should happen. A bit of the artist’s dreams, hopes, sensitivities, glories, and even angers will become a part of the work. The serigraph or printed textile is born anew from the creative womb of the artist. They exist. They are blood kin to the artist. While he should be proud of what he has done, the artist must beware of too much self-satisfaction. To grow and improve continually in a creative field he has to have that nagging feeling that each work produced, somehow, in some way, could have been improved.

The artist, to maintain his individuality, responds sensitively and in a very personal way to his environment and his culture. He needs a certain amount of ego and strength to do this. For, in a way, the artist is “the conscience of mankind.” Great works of art are indeed rare and most of us will never produce one, but there is always that chance. But the chance will exist only so long as each work is an earnest, vital, and sensitive response on the part of the artist. These preconditions are the requisites for that rare, magical alchemy that gives greatness to any work of art.

Evaluating Your Work

Self-evaluation is most difficult. Yet it is the evaluation that is most meaningful. Honest evaluation from friends is hard to come by. Evaluation from a dedicated and experienced teacher or fellow artist can help clear one’s eyes. The main difficulty in self-evaluation is that one is so close to the work—so many plans and dreams have become part of it and there have been so many trials and retrials—that one is not always sure where he has failed or succeeded. It helps sometimes to let a work age. You will always see things better if you can stand back a few feet. Often it helps to place a work in a public exhibition with other works. This becomes a sort of testing ground. But even here it is the artist who must apply the final test. He must decide how a work holds up in view of his own goals.

The textile designer can find satisfaction in the printed textile in many implicit ways. The combined color, movement, and rhythmic arrangement—or the unexpected joy of the pattern—may reveal itself only after some study of the finished product; well after the in-process struggles and adjustments. It is a juxtapositioning of the difficult with the simple. It is a determined push into the unknown. It is a constant battle with the forces of conformity to make the plain rich, the dull exciting—a feast to the beholder.

Pieces that fall short of these high goals may be considered at least as a step along the way. One should learn from both successes and failures. If it really disappoints, the textile designer always has the practical option of washing out the design before the final heat setting. The weak image remaining in the fabric may generate a fresh idea that could be overprinted.

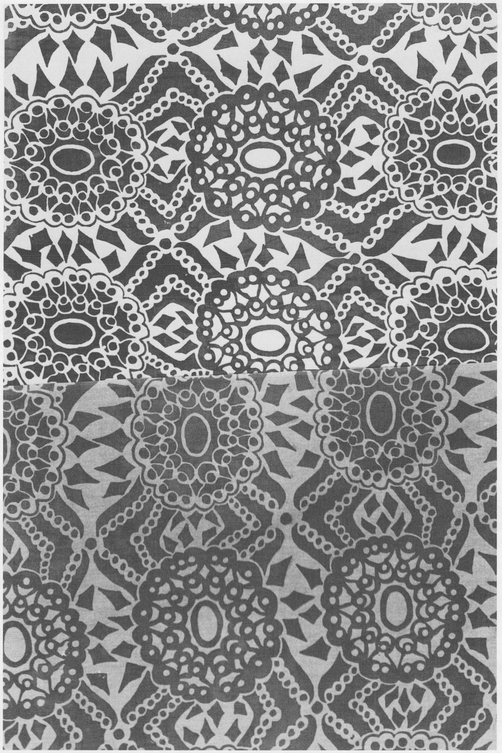

Fig. 9-2. Value differences in color can alter the effect of one design considerably. (“Sunburst,” by Susan Palm)

The serious serigrapher must face the “selection of the edition.” Each will devise his own method, but all the prints must be carefully scrutinized. Any that differs greatly from the rest must be set aside along with any prints with faults (smudges in the margins, bad registration, smearing, streaks). These are to be rejected from the edition. What is left is a nearly identical series of prints. They are not exactly alike. An experienced printer may have 5 to 10 per cent rejections from the original group.

Identification of Work and Keeping Records

For the professional printmaker, the finished edition can be important as a source of income, but even if not primarily concerned with the sale of his work, the printmaker is fairly prolific if he is serious. This suggests that there ought to be some system of identifying works and keeping records. The prints finally selected in an edition are usually signed by the artist in the bottom right-hand margin. In the bottom left-hand margin the print is titled and given an identification number. (In etching and lithography, the number indicates the order in which the prints come off the press, but that has no significance in serigraphy.) For example, 6/35 written after the title indicates that the identifying number for this particular print is 6 and the number of prints in the entire edition is 35. The date can follow this number or it can follow the artist’s signature. Some printmakers place the title in the center of the bottom margin; others put the identifying number in the center. There is no one way to do it, but all prints in an edition should contain that information. Rejected prints or proof prints (the first prints made while you are experimenting with the color run) are signed in a similar manner but are labeled “artist’s proof.” Prints that are not suitable are destroyed.

Professional textile designers sign their work in a similar fashion, but as part of the printing process. Along one edge of the yardage the artist’s name is screened and sometimes the title of the design, date of production, and the name and location of the studio. Usually this information is put on acetate and a photogelatin-emulsion resist produced, which is placed on a small screen specially built for this purpose. It is then squeegeed close to one of of the edges approximately every yard. It should not be conspicuous if the textile is to serve as a wall hanging and will probably end up in a hem or seam if the textile finds a practical use. But it serves the same purpose as the signature of the serigrapher: it is testimony to the quality and originality of the work and is useful for the designer in keeping records of his work.

Serigraphs are easily transported, sold, borrowed, and exhibited, and in recent years there has been a growing interest in the exhibition and sale of hand-printed textiles. Because of income-tax considerations and the need to keep track of where a work is at a particular time, it is necessary to keep some simple records. Some printmakers and designers find a card-file index suitable, devoting a card to each edition, on which is recorded the name of the print, its insurance value, retail price, and date of production. The number of prints in the edition and the cost in materials and time are items useful in figuring the annual income-tax report. Sales, loans, and exhibitions can also be recorded on the same card. If the card is quite small, a separate card can be devoted to each print in the edition. Other printmakers find it simpler to keep records in a standard business ledger. Textile designers can keep the same type of records under the title given to each fabric design. When screens are stored for subsequent production, they are labeled with the title of the design.

Matting and Framing a Print

Often a designer does not really see his print until it appears for the first time in a mat, which serves to separate the print from the competing environment. Many printers keep a spare mat handy so that each color run of an edition can be properly viewed for evaluating the results. The mat is usually a smooth or slightly pebbled sheet of heavy white cardboard called mat board. Occasionally a printmaker will use a light cream or gray mat, but strong mat colors tend to compete with the print. Many exhibitions and the National Serigraph Society suggest that mats be cut in one of three sizes: 15 by 20 inches, 20 by 24 inches, or 22 by 28 inches. Because of the difficulty of hanging and shipping, some exhibitions will not accept mats much larger than those sizes.

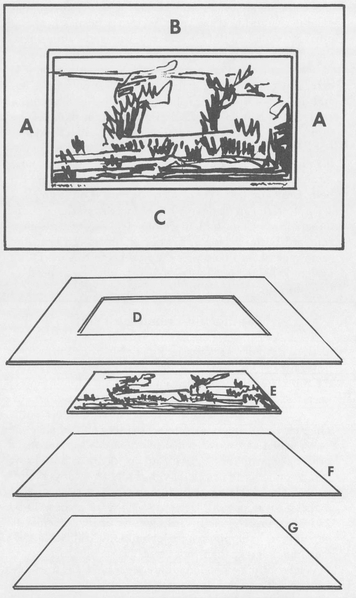

While cutting a good mat may seem to be a rather simple procedure, there is a great deal of skill involved. If you plan to mat only a few prints, it is better to have your mats cut by someone with experience. Generally, the width of the center hole is ½ inch wider than the width of the print. The height of the hole is ¾ inch higher. This allows the print to be exposed ¼ inch on both sides and the top and ½ inch on the bottom for signing and identifying the print. If the print is matted without such margins, it is signed, dated, and numbered on its surface in the lower right-hand corner; then the title is put on the mat. However, this is not the normal procedure. The side widths of the mat are the same. The size of the mat board may not permit the top width to be the same as the sides. The bottom width is usually wider than the sides and the top. This gives the print a little better optical centering and makes it more comfortable to view (Fig. 9-3). The area of the mat should be sufficient to set off the print from its surroundings.

Cutting the hole requires skill. A good sharp, sturdy mat knife is a necessity, and so is a strong metal straight-edge at least 3 feet long. Since the metal has a tendency to slide out of position during cutting, glue some fine sandpaper along its underside. This will prevent the sliding. Place several old newspapers under the cardboard and cut firmly. The angle at which you hold the blade will determine the bevel of the cut, and whether it is straight or beveled is up to you. The knife should be sharp enough to cut easily with one smooth stroke. Pull the knife toward you as you cut. Keep a sharpening stone handy for frequent resharpening of the cutting edge.

Fig. 9-3. When a print is matted, the sides (A) of the mat are almost always equal in width; the top (B) is frequently the same width but can be slightly larger or smaller; and the bottom (C) is always larger than the top or sides. The hole in the mat (D) should be slightly larger than the print (E). The mat covers the print, which is in turn backed by background paper (F)—a fairly stiff paper to which the print is carefully glued with wallpaper paste or lightly taped. The whole thing is backed by protective cardboard (G).

After the mat is cut, position the print properly behind the hole and fasten it lightly to the back of the mat. It can then be adhered with gummed paper tape. Some printmakers place an extra sheet of blank print paper behind the print. The print is then protected with a backing of ordinary cardboard cemented with wallpaper paste or one of the casein glues produced specifically for use on paper.

The white surface of a mat dirties very easily. Most of the smudges and dirt can be removed with ordinary art gum erasers. Greasy finger marks will need rubbing with white powdered pumice, which can be purchased at many drug- or hardware stores. Use a clean cotton cloth to rub the pumice into the surface of the cardboard. If the prints are going into a sales and rental gallery or are going to be subjected to rough handling, it is a wise precaution to protect them with clear acetate. Some printers object to the reflections that this causes, but rough handling can destroy a print. The acetate should be as thin as possible. Stretch it tightly over the front of the matted print, fold it down, and fasten it to the back with gummed or masking tape. If the prints are going on an extensive exhibition circuit, such protection is mandatory. The hanging of the prints will be facilitated if you punch into each corner of the mat a white eyelet similar to the kind used in tennis shoes.

Framing serigraphs is primarily a matter of personal decision. Since serigraphs rarely have the weight of oil paintings, they are usually presented in simpler, smaller frames. Prints are mounted under a mat and generally framed under glass with the back and edges sealed against changes in humidity. Prints given a careful spraying of clear plastic can be framed without glass, but much more care must be taken with the mounting to prevent the print from buckling. Rubber cement should not be used in mounting prints. Wallpaper paste is preferred, as are the new casein glues especially prepared for paper. The cardboard used for mounting should be smooth and absorbent. First coat the back of the print with the glue so that the paper will expand before the print has adhered, then coat the mounting board. Allow both to set until they get tacky. Both glue coats should be very thin and set long enough to be absorbed into the surface. This will prevent the glue from oozing out beyond the edges. Place the print and mounting board together carefully, and cover the print with a piece of clean unprinted newsprint or white wrapping paper. Roll the print carefully with a rubber roller, starting from the center of the print and working out toward the edges.

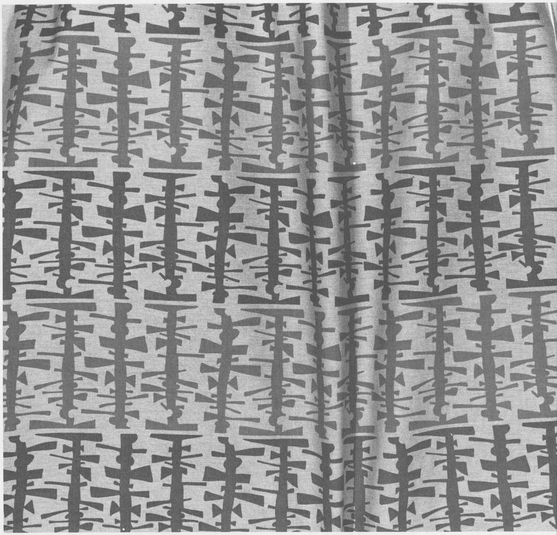

Fig. 9-4. The stencil for this two-color textile print was made with Profilm. (“Pines,” by Sue Churchill Powell)

Display of Textiles

Printed textiles present far fewer problems than paper prints in mounting for display. Wall hangings are usually stiffened at the top with an inconspicuous bar of metal or wood. A cord fastened to each end of the bar allows the fabric to be hung. Occasionally the bottom of the textile may be weighted with a similar bar of wood or metal. Textiles are frequently designed to be hung on a wall and are not necessarily repeated patterns. Repeated patterns can also be used as wall hangings with great success, although they are usually cut up and rearranged for clothing, pillows, or the like. These varied uses often determine the nature of a design, but this does not preclude textile designs printed for pure pleasure and self-expression.

Storing Your Work

Fabrics ready for printing and finished textiles can be successfully stored if rolled on tubes of cardboard or old newspaper. They remain free from creases and wrinkles and may be easily rolled out when needed. Thirty-six-inch rolls and other full widths can be placed upright in tall cartons in most household closets. Narrower widths can go on shelves or in drawers for convenient access. If the title of the design is written on protective wrapping paper around the roll, it can be identified more quickly.

Prints are safer stored in portfolios, which can be laid flat on shelves or in shallow (but wide and deep) drawers. Again, the title of the edition can be labeled on the outside of each portfolio. Having one portfolio that contains one or more copies of all your current work facilitates preparation for sales and exhibitions. Because of the relatively heavy layer of ink on a serigraph, the surface is subject to creasing, cracking, and scratching. Avoid touching the surface of a serigraph and do not fold or crease one. Even rolling a print should be avoided. If absolutely necessary, it should be rolled loosely (a minimum of 4 inches in diameter). Storing rolled prints is very hazardous since they are subject to creasing if any weight is placed on them inadvertently, and the paint may be loosened from the paper and flake off. Also, rolled prints are more difficult to mat and frame. Never pull a print out from the center of a stack. This is likely to result in a scratch or abrasion. Remove the top copies until you reach the one you wish.

Exhibition and Sale of Work

Both the serigrapher and the textile designer should consider the possible exhibition of their work. The exhibition is not usually a commercially profitable activity, but it is the necessary public testing of the artist’s idea. Many exhibitions are juried, and whatever faults may be found with the jury system, it still represents the best outside test an artist can find for his work. But no single exhibition success or failure should be taken too seriously. The designer or serigrapher who participates in a fair number of competitive exhibitions will get a somewhat useful judgment of the quality of his work. Exhibitions range from the very large national and international ones with thousands of entries to the very small local ones. They vary a good deal. Art magazines usually list them well in advance and anyone wishing to compete can send for an entry blank and information. It is a time-consuming and somewhat expensive endeavor. You must be prepared to face entry fees and transportation costs as well as packing expenses. Most exhibitions will pay for returning work that has been accepted, but usually the printer pays for transportation to the exhibition as well as the return costs if his work is rejected.

Those interested in selling their work will find it more useful to deal with private galleries and agents. Most will take work on consignment. When the artist is pricing his work, he should realize that anywhere from 30 to 40 per cent of the price is the commission paid to the gallery. Agents usually get as much as 50 to 75 per cent of the retail price, but remember that an agent can often sell an entire edition. When delivering work to a gallery or agent, the artist is usually expected to furnish a complete listing of the works, including the retail price (which includes the gallery’s commission), in duplicate. The gallery will keep one copy and the artist the other. It is wise to get a signed contract that stipulates how long the work will be left at the gallery as well as the financial arrangements. The artist usually must agree not to sell a print for less than the gallery charges for the same print. Galleries often put considerable effort into promoting the artist and his work.

Serigraphs and textiles shipped to exhibitions should be carefully labeled and identified. For the textile designer, the roll is a convenient way to ship or transport pieces with a minimum of wrinkling. Serigraphs should be protected first with clean newsprint or tissue paper on each surface, then wrapped together in clean wrapping paper. Placing the prints face to face gives further protection. The package then is protected with a thin sheet of plywood on one side and corrugated cardboard on the other side. This in turn is wrapped in heavy wrapping paper. Constructing a wooden case for shipping is more expensive but a good investment if much use is anticipated.

The artist or designer does not have very adequate protection against the unwarranted display or reproduction of his work. And in most cases the court costs and procedures involved in fighting it are far too expensive. But if he is interested, he gets some protection if he does the following: somewhere on the print or fabric he should place a copyright symbol © and his signature. It can be incorporated in one of the color runs and printed. It is not necessary to register this copyright or pay any fees to have a valid binding copyright. However, if he wishes to start a suit, then he would have to register it, submit a copy of the work, and pay the registration fee. Additional protection is assured if he accompanies the sale of each work with a bill that has this statement printed on it: “All reproduction rights are reserved by the artist.”

The problem for the textile designer is even greater. The pirating of a design can be easily accomplished if the pirate changes only some small part of the design, which, in theory, produces a new design.