IN CONTEXT

Biology

2000 BCE Chinese scientists make a water microscope with a glass lens and a water-filled tube to see very small things.

1267 English philosopher Roger Bacon suggests the idea of the telescope and the microscope.

c.1600 The microscope is invented in the Netherlands.

1665 Robert Hooke observes living cells and publishes Micrographia.

1841 Swiss anatomist Albert von Kölliker finds that each sperm and egg is a cell with a nucleus.

1951 German physicist Erwin Wilhelm Müller invents the field ion microscope and sees atoms for the first time.

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek rarely ventured far from his home above a drapery in Delft in the Netherlands. But working on his own in his back room, he discovered an entirely new world – the world of previously unseen microscopic life, including human sperm, blood cells, and, most dramatically of all, bacteria.

Before the 17th century, no one suspected there was life too small to see with the naked eye. Fleas were thought to be the smallest possible form of life. Then, in about 1600, the microscope was invented by Dutch spectacle-makers who put two glass lenses together to boost their magnification. In 1665, English scientist Robert Hooke made the first drawing of tiny living cells that he had seen in a slice of cork through a microscope.

It never occurred to Hooke or any other microscopist of the time to look for life anywhere they could not already see it with their own eyes. Leeuwenhoek, by contrast, turned his lenses on places where there appeared to be no life at all, particularly in liquids. He studied raindrops, tooth plaque, dung, sperm, blood, and much more besides. It was here, in these apparently lifeless substances, that Leeuwenhoek discovered the richness of microscopic life.

Unlike Hooke, Leeuwenhoek did not use a two-lens “compound” microscope, but a single, high-quality lens – really a magnifying glass. At the time, it was in fact easier to produce a clear picture with such simple microscopics. A magnification greater than 30 times was impossible with compound microscopes as the image became blurred. Leeuwenhoek ground his own single lens microscopes, and after years of honing his technique, managed a magnification of more than 200 times. His microscopes were small devices with tiny lenses just a few millimetres (fractions of an inch) wide. The sample was placed on a pin on one side of the lens, and Leeuwenhoek held one eye up close to the other side.

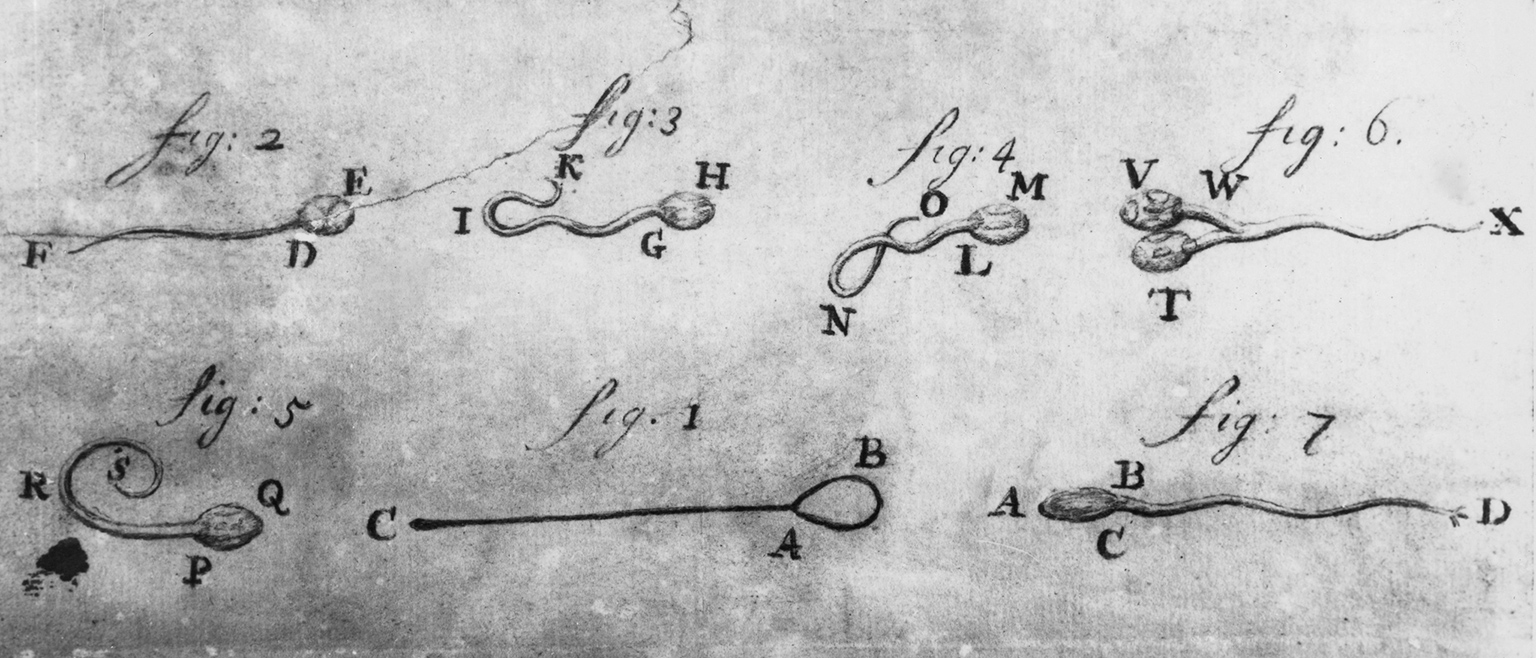

When Leeuwenhoek’s drawings of human sperm were first published in 1719, many people did not accept that such tiny swimming “animalcules” could exist in semen.

Single-celled life

At first, Leeuwenhoek found nothing unusual, but then, in 1674, he reported seeing tiny creatures thinner than a human hair in a sample of lake water. These were the green algae Spirogyra, an example of the simple life forms that are now known as protists. Leeuwenhoek called these tiny creatures “animalcules”. In October 1676, he discovered even smaller single-celled bacteria in drops of water. In the following year, he described how his own semen was swarming with the little creatures we now call sperm. Unlike the creatures he had found in water, the animalcules in semen were all identical. Each of the many thousands he looked at had the same tiny tail and the same tiny head, and nothing else, and he could see them swimming like tadpoles in the semen.

Leeuwenhoek reported his findings in a series of hundreds of letters to the Royal Society in London. While he published his findings, he kept his lens-making techniques secret. It is probable that he made his tiny lenses by fusing thin glass threads, but we do not know for sure.

ANTONIE VAN LEEUWENHOEK

The son of a basket-maker, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was born in Delft in 1632. After working in his uncle’s linen drapery, he established his own draper’s shop at the age of 20 and remained there for the rest of his long life.

Leeuwenhoek’s business allowed him time to pursue his hobby as a microscopist, which he took up in about 1668 after a visit to London, where he may have seen a copy of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia. From 1673 onwards, he reported his findings in letters to the Royal Society in London, writing more reports to them than any scientist in history. The Royal Society was initially sceptical of the amateur’s reports, but Hooke repeated many of his experiments and confirmed his discoveries. Leeuwenhoek made more than 500 microscopes, many designed to view specific objects.

Key works

1673 Letter 1, Leeuwenhoek’s first letter to the Royal Society

1676 Letter 18, revealing his discovery of bacteria

See also: Robert Hooke • Louis Pasteur • Martinus Beijerinck • Lynn Margulis