IN CONTEXT

Biology

4th century BCE The Greeks use the terms “genus” and “species” to describe groups of similar things.

1583 Italian botanist Andrea Cesalpino classifies plants based on seeds and fruits.

1623 Swiss botanist Caspar Bauhin classifies more than 6,000 plants in his Illustrated Exposition of Plants.

1690 English philosopher John Locke argues that species are artificial constructs.

1735 Carl Linnaeus publishes Systema Naturae, the first of his many works classifying plants and animals.

1859 Charles Darwin proposes the evolution of species by natural selection in On the Origin of Species.

The modern concept of a plant or animal species is based on reproduction. A species includes all individuals that can actually or potentially breed together to produce offspring, which in turn can do the same. This concept, first introduced by English natural historian John Ray in 1686, still underpins taxonomy – the science of classification, in which genetics now plays a major role.

Metaphysical approach

During this period, the term “species” was in common usage, but intricately connected with religion and metaphysics – an approach persisting from ancient Greece. The Greek philosophers Plato, Aristotle, and Theophrastus had discussed classification and used terms such as “genus” and “species” to describe groups and subgroups of all manner of things, living or inanimate. In doing so, they had invoked vague qualities such as “essence” and “soul”. So members belonged to a species because they shared the same “essence”, rather than sharing the same appearance or the ability to breed with one another.

By the 17th century, myriad classifications existed. Many were organized in alphabetical order, or by groups derived from folklore, such as grouping plants according to which illnesses they could treat. In 1666, Ray returned from a three-year European tour with a large collection of plants and animals that he and his colleague Francis Willughby intended to classify along more scientific lines.

"Nothing is invented and perfected at the same time."

John Ray

Practical nature

Ray introduced a novel practical, observational approach. He examined all parts of the plants, from roots to stem tips and flowers. He encouraged the terms “petal” and “pollen” into general usage and decided that floral type should be an important feature for classification, as should seed type. He also introduced the distinction between monocotyledons (plants with a single seed leaf) and dicotyledons (plants with two seed leaves). However, he recommended a limit to the number of features used for classification, to prevent species numbers multiplying to unworkable proportions. His major work, Historia Plantarum (Treatise on Plants), published in three volumes in 1686, 1688, and 1704, contains more than 18,000 entries.

For Ray, reproduction was the key to defining a species. His own definition came from his experience gathering specimens, sowing seeds, and observing their germination: “no surer criterion for determining [plant] species has occurred to me than the distinguishing features that perpetuate themselves in propagation from seed…Animals likewise that differ specifically preserve their distinct species permanently; one species never springs from the seed of another nor vice versa.” Ray established the basis of a true-breeding group by which a species is still defined today. In so doing, he made botany and zoology scientific pursuits. Devoutly religious, Ray saw his work as a means of displaying the wonders of God.

Wheat is a monocotyledon (a plant whose seed contains a single leaf) as defined by Ray. Around 30 species of this major food crop have evolved from 10,000 years of cultivation, and all of them belong to the genus Triticum.

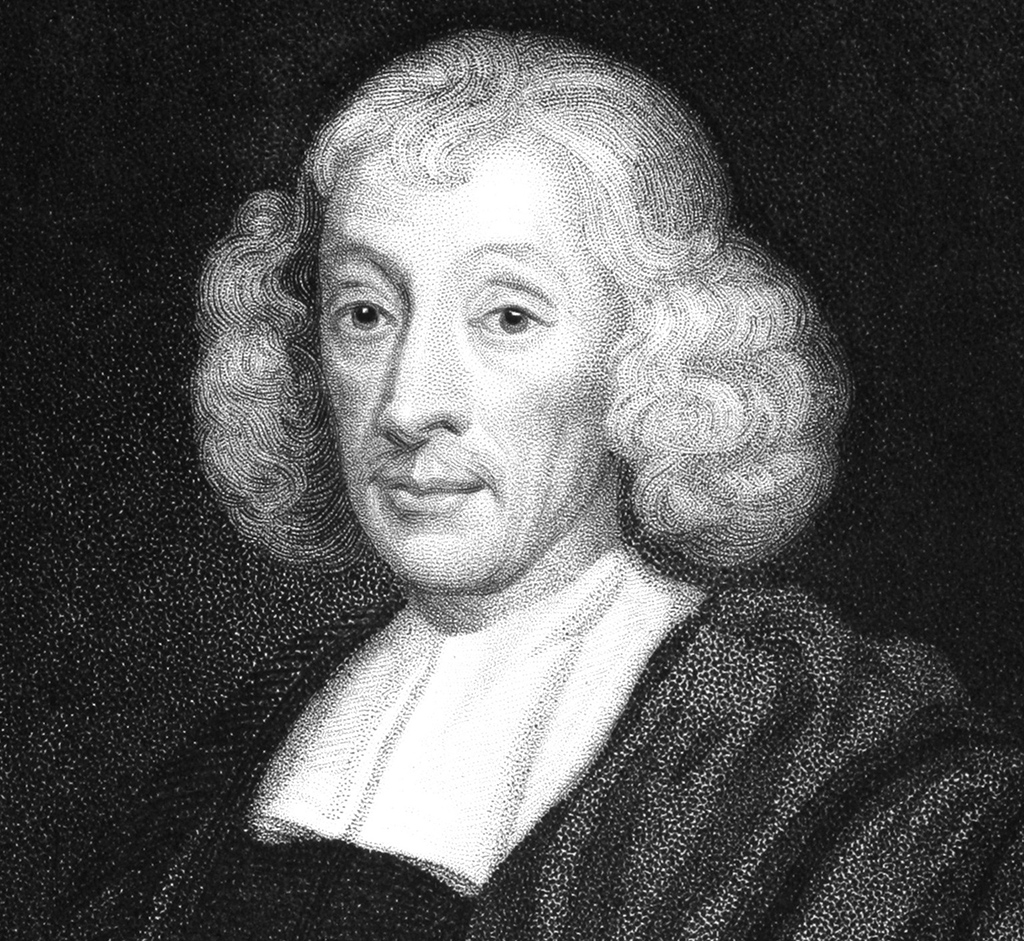

JOHN RAY

Born in 1627 in Black Notley, Essex, England, John Ray was the son of the village blacksmith and the local herbalist. At 16, he went to Cambridge University, where he studied widely and lectured on topics from Greek to mathematics, before joining the priesthood in 1660. To recuperate from an illness in 1650, he had taken to nature walks and developed an interest in botany.

Accompanied by his wealthy student and supporter Francis Willughby, Ray toured Britain and Europe in the 1660s, studying and collecting plants and animals. He married Margaret Oakley in 1673 and, after leaving Willughby’s household, lived quietly in Black Notley to the age of 77. He spent his later years studying specimens in order to assemble ever-more ambitious plant and animal catalogues. He wrote more than 20 works on plants and animals and their taxonomy, form, and function, and on theology and his travels.

Key work

1686–1704 Historia Plantarum

See also: Jan Swammerdam • Carl Linnaeus • Christian Sprengel • Charles Darwin • Michael Syvanen