IN CONTEXT

Biology

1794 Erasmus Darwin (Charles’s grandfather) recounts his vision of evolution in Zoonomia.

1809 Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposes a form of evolution through the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

1937 Theodosius Dobzhansky publishes his experimental evidence for the genetic basis of evolution.

1942 Ernst Mayr defines the concept of species through populations that reproduce only with one another.

1972 Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould propose that evolution occurs mainly in short bursts interspersed with periods of relative stability.

The British naturalist Charles Darwin was by no means the first scientist to suggest that plants, animals, and other organisms are not fixed and unchanging – or, to use the popular word of the time, “immutable”. Like others before him, Darwin proposed that species of organisms change, or evolve, through time. His great contribution was to show how evolution took place by a process he termed natural selection. He laid out his central idea in his book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, published in London in 1859. Darwin described the book as “one long argument”.

“Confessing a murder”

On the Origin of Species met with academic and popular opposition. It made no mention of religious doctrine, which insisted that species were indeed fixed and immutable and designed by God. But gradually the ideas in the book changed the scientific perspective on the natural world. Its core notion forms the basis for all modern biology, providing a simple, but immensely powerful, explanation of life forms both past and present.

Darwin was acutely aware of the potential blasphemy in his work during the decades he spent writing it. Fifteen years before publication, he explained to his confidant, the botanist Joseph Hooker, that his theory required no God or unchanging species: “At last gleams of light have come, & I am almost convinced (quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable.”

Darwin’s approach to evolution, like the rest of his wide-ranging work in natural history, was cautious, careful, and deliberate. He proceeded step by step, amassing great quantities of evidence along the way. Over almost 30 years, he integrated his extensive knowledge of fossils, geology, plants, animals, and selective breeding, with concepts from demography, economics, and many other fields. The resulting theory of evolution by natural selection is regarded as one of the greatest scientific advances ever.

"Creation is not an event that happened in 4004 BCE; it is a process that began some 10 billion years ago and is still under way."

Theodosius Dobzhansky

The role of God

In the early 19th century, fossils were widely discussed in Victorian society. Some regarded them as naturally formed rock shapes, and nothing to do with living organisms. Others saw them as the handiwork of the Creator, put on Earth to test believers. Or they thought that they were the remains of organisms still alive somewhere in the world, since God had created living things in perfection.

In 1796, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier recognized that certain fossils, such as those of mammoths or giant sloths, were the remains of animals that had become extinct. He reconciled this with his religious belief by invoking catastrophes such as the Flood depicted in the Bible. Each disaster swept away a whole assortment of living things; God then replenished Earth with new species. Between each disaster, each species remained fixed and immutable. This theory was known as “catastrophism” and it became widely known following the publication of Cuvier’s Preliminary Discourse in 1813.

However, at the time Cuvier was writing, various ideas based on evolution were already in circulation. Erasmus Darwin, the free-thinking grandfather of Charles, proposed an early, idiosyncratic theory. More influential were the ideas of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, professor of zoology at France’s National Museum of Natural History. His Philosophie Zoologique of 1809 articulated what was perhaps the first reasoned theory of evolution. He theorized that living beings evolved from simple beginnings through increasingly sophisticated stages, due to a “complexifying force”. They faced environmental challenges on their body physiques, and from this came the idea of use and disuse in an individual: “More frequent and continuous use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ…while the permanent disuse of any organ imperceptibly weakens and deteriorates it…until it finally disappears.” The organ’s greater power was then passed to offspring, a phenomenon that became known as inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Although his theory came to be largely discounted, Lamarck was later praised by Darwin for having opened up the possibility that change did not occur as a result of what Darwin disparagingly termed “miraculous interposition”.

By studying the fossil record, Georges Cuvier established that species had become extinct. But he believed that the evidence pointed to a series of catastrophes, not gradual change.

Adventures of the Beagle

Darwin had plenty of time to muse on the immutability of species during a round-the-world voyage aboard the survey ship HMS Beagle, in 1831–36, under captain Robert FitzRoy. As expedition scientist, Darwin was charged with collecting all manner of fossil, plant, and animal specimens, and sending them back to Britain from each port of call.

This epic voyage opened the eyes of the young Darwin, still only in his twenties, to the incredible variety of life. Wherever the Beagle docked, Darwin keenly observed all aspects of nature. In 1835, he described and collected a group of small, insignificant birds on the Galápagos Islands, a Pacific Ocean archipelago 900km (560 miles) west of Ecuador. He thought there were nine species, six being finches.

After his return to England, Darwin organized his mass of data and oversaw a multi-volume, multi-author report, The Zoology of the Voyage of HMS Beagle. In the volume on birds, the renowned ornithologist John Gould declared that there were in fact 13 species in Darwin’s specimens, all of them finches. Within the group, however, were birds with differently shaped beaks, adapted to different diets.

In his own, bestselling account of his adventure, The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin wrote, “Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.” This was one of the first clear, public formulations of where his thoughts on evolution were heading.

This giant tortoise is only found on the Galápagos Islands, where unique subspecies have developed on each island. Darwin gathered evidence here for his theory of evolution.

Comparing species

Darwin’s finches, as the Galápagos specimens became known, were not the only trigger for his work on evolution. In fact, his thoughts had been mounting throughout the Beagle’s voyage, and especially during his visit to the Galápagos. He was fascinated by the giant tortoises he saw, and by the way the shapes of their shells differed subtly from island to island. He was also impressed by the species of mockingbirds. They, too, varied between the islands, yet they also had similarities not only among themselves, but with species that lived on the South American mainland.

Darwin suggested that the various mockingbirds might have evolved from a common ancestor that had somehow crossed the Pacific from the mainland; then each group of birds evolved by adapting to the particular environment on each island and its available food. Observing giant tortoises, Falkland Island foxes, and other species supported these early conclusions. But Darwin was sensitive about where such blasphemous ideas would lead: “Such facts would undermine the stability of species.”

"Natural selection is the…principle by which slight variation (of a trait), if useful, is preserved."

Charles Darwin

Other parts of the jigsaw

On his way to South America in 1831, Darwin had read the first volume of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology. Lyell argued against Cuvier’s catastrophism history and his theory of fossil formation. Instead, he adapted the ideas of geological renewal put forward by James Hutton into a theory known as “uniformitarianism”. Earth was continually being formed, altered, and reformed over immense time periods by processes such as wave erosion and volcanic upheaval that were the same as those happening today. There was no need to invoke disastrous interventions by God.

Lyell’s ideas transformed the way Darwin interpreted the landscape formations, rocks, and fossils he found on his explorations, which he now saw “through Lyell’s eyes”. However, while he was in South America, volume two of Principles of Geology arrived. In it, Lyell rejected ideas of gradual evolution of plants and animals, including Lamarck’s theories. Instead, he invoked the concept of “centres of Creation” to explain species’ diversity and distribution. Although Darwin admired Lyell as a geologist, he had to discount this latest concept as the evidence for evolution mounted.

Another piece of the jigsaw was revealed in 1838 when Darwin read An Essay on the Principle of Population by the English demographer Thomas Malthus, which had been published 40 years earlier. Malthus described how human populations can increase in an exponential way, with the potential to double after one generation of 25 years, then double again in the next generation, and so on. However, food supplies could not expand in the same way, and the result was a struggle for existence. Malthus’s ideas were one of the main inspirations for Darwin’s theory of evolution.

The finches of the Galápagos have evolved differently shaped beaks adapted to specific diets.

The quiet years

Even before the Beagle had returned to England, the interest generated by the specimens Darwin had sent back had made him a celebrity. After his return, his scientific and popular accounts of the voyage increased his fame. However, his health deteriorated and gradually he withdrew from the public eye.

In 1842, Darwin moved to the peace and quiet of Down House in Kent, where he continued to amass evidence to support his theory of evolution. Scientists around the world sent him specimens and data. He studied the domestication of animals and plants, and the role of selective breeding, or artificial selection, especially in pigeons. In 1855, he started breeding varieties of Columbia livia, or rock doves, and they would feature prominently in the first two chapters in On the Origin of Species.

Through his work on pigeons, Darwin began to understand the extent and relevance of variation among individuals. He rejected the accepted wisdom that environmental factors were responsible for such differences, insisting that reproduction was the cause, with variation somehow inherited from parents. He added this to the ideas of Malthus and applied them to the natural world.

Much later, in his autobiography, Darwin recalled his reaction when he first read Malthus back in 1838. “Being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence…it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species…I had at last got a theory by which to work.”

Knowing more about the role of variation, by 1856 Darwin the pigeon breeder could imagine not humans but nature doing the choosing. From the term “artificial selection” he derived “natural selection”.

Jolt into action

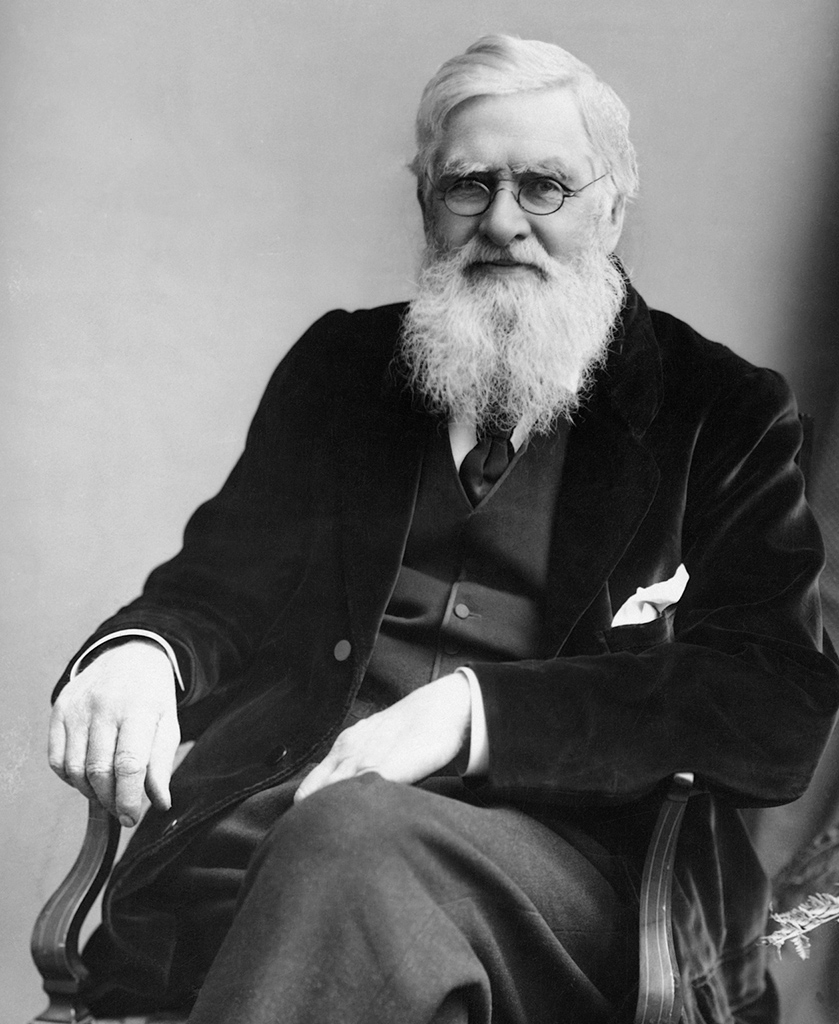

On 18 June 1858, Darwin received a short essay by a young British naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace described a flash of insight in which he had suddenly understood how evolution occurred, and asked Darwin for his opinion. Darwin was startled to read that Wallace’s insight replicated almost exactly the same ideas he himself had been working on for more than 20 years.

Worried about precedence, Darwin consulted Charles Lyell. They agreed to a joint presentation of Darwin’s and Wallace’s papers at the Linnaean Society in London on 1 July 1858. Neither author would attend in person. The audience’s response was polite, with no outcry about blasphemy. Encouraged, Darwin now finished his book. Published on 24 November 1859, On the Origin of Species sold out on its first day.

Darwin’s theory

Darwin states that species are not immutable. They change, or evolve, and the main mechanism for this change is natural selection. The process relies on two factors. First, more offspring are born than can survive when faced with the challenges of climate, food supply, competition, predators, and diseases; this leads to a struggle for existence. Second, there is variation, sometimes tiny but nonetheless present, among the offspring within a species. For evolution, these variations must fulfil two criteria. One: they should have some effect on the struggle to survive and breed, that is, they should help to confer reproductive success. Two: they should be inherited, or passed to offspring, where they would confer the same evolutionary advantage.

Darwin describes evolution as a slow and gradual process. As a population of organisms adapts to a new environment, it becomes a new species, different from its ancestors. Meanwhile, those ancestors may remain the same, or they may evolve in response to their own changing environment, or they may lose the struggle for survival and become extinct.

Alfred Russel Wallace, like Darwin, developed his theory of evolution in the light of extensive field work, conducted first in the Amazon River Basin and later in the Malay Archipelago.

"I think I have found out (here’s presumption!) the simple way by which species become exquisitely adapted to various ends."

Charles Darwin

Aftermath

Faced with such a thorough, reasoned, evidence-based exposition of evolution by natural selection, most scientists soon accepted Darwin’s concept of “survival of the fittest”. Darwin’s book was careful to avoid any mention of humans in connection with evolution, apart from the single sentence, “Light will be shed on the origin of man, and his history”. However, there were protests from the Church, and the clear implication that humans had evolved from other animals was ridiculed in many quarters.

Darwin, as ever avoiding the limelight, remained engrossed in his studies at Down House. As controversy mounted, numerous scientists sprang to his defence. The biologist Thomas Henry Huxley was vociferous in supporting the theory – and arguing the case for human descent from apes – and dubbed himself “Darwin’s bulldog”.

However, the mechanism by which inheritance occurred – how and why some traits are passed on, others not – remained a mystery. Coincidentally, at the same time that Darwin published his book, a monk named Gregor Mendel was experimenting with pea plants in Brno (in the present-day Czech Republic). His work on inherited characteristics, reported in 1865, formed the basis of genetics, but was overlooked by mainstream science until the 20th century, when new discoveries in genetics were integrated into evolutionary theory, providing a mechanism for heredity. Darwin’s principle of natural selection remains key to understanding the process.

This cartoon ridiculing Darwin appeared in 1871, the year in which he applied his theory of evolution to humans – something he had been careful to avoid in earlier works.

CHARLES DARWIN

Born in Shrewsbury, England, in 1809, Darwin was originally destined to follow his father into medicine, but his childhood was filled with pursuits such as beetle-collecting, and with little inclination to become a physician, he trained for the clergy. A chance appointment in 1831 placed hiim as expedition scientist on HMS Beagle’s round-the-world trip.

Following the voyage, Darwin was under the scientific spotlight, gaining fame as a perceptive observer, reliable experimenter, and talented writer. He wrote on the formation of coral reefs and on marine invertebrates, especially barnacles, which he studied for almost 10 years. He also wrote works on fertilization, of orchids, insect-eating plants, movement in plants, and variation among domesticated animals and plants. Later in life, he tackled the origin of humans.

Key works

1839 The Voyage of the Beagle

1859 On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection

1871 The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex