IN CONTEXT

Palaeontology

11th century Persian scholar Avicenna (Ibn Sina) suggests that rocks can be formed from petrified fluids, leading to the formation of fossils.

1753 Carl Linnaeus includes fossils in his system of biological classification.

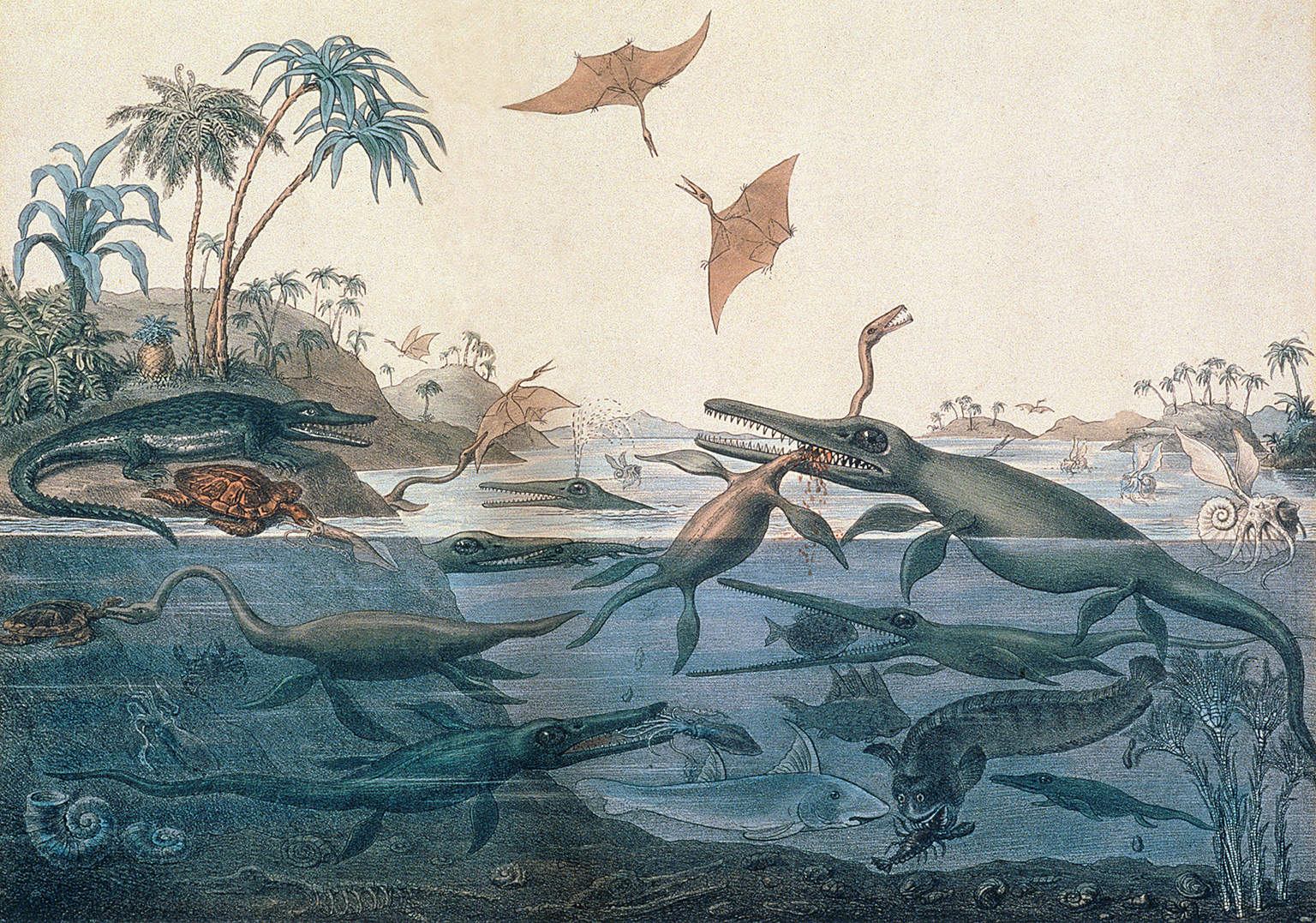

1830 British artist Henry De la Beche paints one of the first palaeo-reconstructions of a scene from “deep time”.

1854 Richard Owen and Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins make the first life-size reconstructions of extinct plants and animals.

Early 20th century The development of radiometric dating techniques allows scientists to date fossils according to the rock strata in which they are found.

By the end of the 18th century, it was generally accepted that fossils were the remains of once living organisms that had been petrified as the sediment around them hardened into rock. Both fossils and living organisms had been classified for the first time into a hierarchy of species, genera, and families by naturalists such as the Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus. However, fossil remains were still seen in isolation from their environmental and biological context.

In the early 19th century, the discovery of large fossilized bones unlike those of any living animal raised many new questions. Where did they fit into the classification systems, and when had they become extinct? Within the Judaeo-Christian culture of the Western world, it was generally thought that a benevolent God would not have allowed any of his creations to die out.

Monsters from the abyss

Some of the first of these large and distinctive fossil remains were found by the Anning family of fossil collectors around Lyme Regis on the coast of southern England. Here, Jurassic-period limestone and shale strata outcrop in the cliffs, where they are eroded by the sea to reveal abundant remains of ancient marine organisms. In 1811, Joseph Anning found a 1.2m- (4ft-) long skull with a curiously elongated toothed beak. His sister Mary found the rest of the skeleton, which they sold for £23. Exhibited in London, this was the first entire skeleton of an extinct “monster of the abyss” and attracted a great deal of popular attention. It was identified as an extinct marine reptile and named an ichthyosaur, meaning “fish-lizard”.

The Anning family went on to find more ichthyosaurs and the first complete specimen of another marine reptile, the plesiosaur, in addition to the first British specimen of a flying reptile, new fossil fish, and shellfish. Among the fish they found were cephalopods known as belemnites, some with the ink-sac preserved. The family, and especially Mary, had a talent for fossil-hunting. Although poor, Mary was literate and taught herself geology and anatomy, which made her a far more effective fossil-hunter. As Lady Harriet Sylvester observed in 1824, Mary Anning was “so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones she knows to what tribe they belong.” She became an authority on many kinds of fossils, especially coprolites – fossilized dung.

The picture of life in ancient Dorset revealed by Anning’s fossils was one of a tropical coast where a wide variety of now-extinct animals thrived. In 1854, Anning’s fossils provided models for the first life-size reconstruction of an ichthyosaur, made for London’s Crystal Palace park by the sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and the palaeontologist Richard Owen. It was Owen who coined the word “dinosaur”, but Anning who had provided the first glimpse of the richness of Jurassic life.

In 1830, Henry De la Beche painted this reconstruction of life in the Jurassic seas around Dorset based on Anning’s fossil discoveries.

MARY ANNING

Several biographies and novels have been written about the life of Mary Anning, a self-taught fossil collector. She was one of two surviving children out of 10 born into an impoverished Dorset family of religious dissenters who lived in the coastal village of Lyme Regis. The family eked out a precarious living collecting fossils for sale to the growing numbers of tourists. However, it was Mary who found and sold their most significant finds – fossils of Jurassic reptiles that lived 201–145 million years ago.

Due to a combination of her gender, humble social standing, and religious unorthodoxy, Anning received little formal recognition of her work in her lifetime, and she noted in a letter, “The world has used me unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone”. However, she was widely known in geological circles and various scientists sought out her expertise. When her health failed, Anning was provided with a small annual pension of £25 in recognition of her contribution to science. She died of breast cancer at the age of 47.

See also: Carl Linnaeus • Charles Darwin • Thomas Henry Huxley