I AM HERE as the conscious result of events set in motion one day in October, 1950, by a remarkable man. Eric James, Lord James of Rusholme, was High Master of Manchester Grammar School throughout the seven years of my time there: a remarkable man; and a remarkable school, which instils the concept of excellence, in the absolute and for its own sake, within the individual, not the group; fitting the school to the boy, rather than making the boy conform to the school. In military terms: let a Winchester, or an Eton, be the Brigade of Guards. Then Manchester Grammar School is the SAS. Its planning of its mission (fulfilment of the boy’s potential) is meticulous and humane: its execution ruthless. I have not yet reached excellence, but I was equipped by that school to seek it out.1

This may sound too close to a production line, and many of the school’s detractors, who have not themselves been pupils there, disparage it as “Manchester Cramming Shop”. But I have experienced what can happen.

One boy, gifted, articulate, acted at all times as if he were a steam-locomotive. He would chuff along the road and the school corridors, feet shuffling, cheeks puffing, arms working as pistons. When he reached the room where his next lesson would be taught, the door was held open for him, imaginary points were changed to get him into the room and to his desk, and an imaginary turntable would turn him to be seated. Then the lesson began. At the end the process was reversed. No one mocked, showed impatience or criticised. He was accepted for the integrated totality of what he was. When, in his own time, that self-image changed, no comment was made, by staff or boys. Simply, the need for an aspect of being had passed.

That anecdote epitomised for me the greatness of the teaching at Manchester Grammar School: the ability to be perceptive, and the confidence to be eccentric. To this day, I am delighted to report, I know no member of the Common Room who is not a seeming loon. For therein lies the quality that sets the school apart. If the quest for excellence can be presumed, there is the freedom to be free. It is the most precious gift: a possession for ever. But what to make of that possession?

Eric James’ contribution was that he, a Physical chemist, impressed on me, a Classical linguist, that without him Science might continue, but without me and my companions Western culture and the context and justification for his skills would be lost.

I remember the room, the window, the desk, the swirl of his gown as he turned and said to me (I was the boy in his line of sight, no more) that for each generation, the Iliad must be told anew. The moment is so clear because it was the first realisation that privilege is service before it is power; that humility is the requirement of pride. Without that realisation I should not have found the temerity proper to the will to write.

Today I want to discuss written language, as an art rather than as a science; and for the purpose of the discussion I shall take “art” to mean the fabrication whereby a reality may be the more clearly revealed and defined.

A prime material of art is paradox, in that paradox links two valid yet mutually exclusive systems that we need if we are to comprehend any reality; paradox links intuition and analytical thought. Paradox, the integration of the non-rational and logic, engages both emotion and intellect without committing outrage on either; and, for me, literature is justified only so long as it keeps a sense of paradox central to its form. Therefore I speak for imaginative writing, not for the didactic. When language serves dogma, then literature, denied the paradox, is lost. The steam-engine was a necessary part of one human being’s development. If it had been quashed by dogma, the school would have survived; but would the boy? So it is if language is deemed to be the master of literature.

Two questions the writer has to answer before he can write are: What is the story and what words can tell it? The answers are the matter of my argument, and in order to achieve what the answers require, the writer must employ and combine two human qualities not commonly used together in harmony: a sense of the numinous, and a rational mind.

The revelation and definition of a reality by art is an act of translation. It is translation, by the agency of the writer and the instrument of story, across the gap between the reality and the reader.

The story is the medium through which the writer interprets the reality; but it is not the reality itself The story is a symbol, which makes a unity of the elements, hitherto seen as separate, that combine uniquely in the writer’s vision.

The words are the language: the means by which the story is made plain; and, unless the language is apt, the story will not translate, for the final translator is not the writer but the reader. To read also is to create.

Language shifts continually; it changes through space and through time. The problem is more easily understood when the language has to translate over chasms of space and time, for then the gap between story and reader, which is always present, is plainer to see. Eric James made me aware of the challenge when he said, “For each generation, the Iliad must be told anew.”

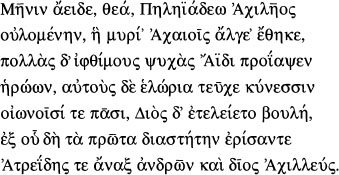

That is the opening of the Iliad as Homer told it. Clearly, we have to find other words. Here are some:

The Wrath of Peleus’ Son, the direful Spring

Of all the Grecian Woes, o Goddess, sing!

That Wrath which hurl’d to Pluto’s gloomy Reign

The Souls of mighty Chiefs untimely slain;

Whose Limbs unbury’d on the naked Shore

Devouring Dogs and hungry Vultures tore.

Since Great Achilles and Atrides strove,

Such was the Sov’reign Doom, and such the Will of Jove.

Thus Alexander Pope in the year 1715.

There we have an example of a generation’s voice. But Pope exemplifies another theme of my argument: the duty of translation.

The more I contemplate the enormity of translation, the more I want to find some dark hole in which to die: or the more I marvel at the ingenuity of language. In this instance, the questions are: What is the essence of Homer? What is the unique, unmistakable genius, as opposed to the mechanical transposition of words? Words are more than the stuffing of a dictionary. They evoke mood as well as dispense fact,

My impression, when reading Plato, is that of drinking cold, fresh water. To me, Aeschylus is blood and darkness. And Homer is leather, oak, the secrets of the smith; Man; God; Fury; above all, magic and wonder in the world of Chaos and the logic of Dream. I see little of that in Pope’s immaculate couplets. His Iliad is the Iliad Homer might have written if he had been an English eighteenth-century gentleman of polite society. That is not quite the same as giving a generation its voice. The difference is important. Pope’s duty was to translate to polite society of the eighteenth-century the heart and mind of Homer; and that he did not do. Instead, the Greek poet was dressed as an Englishman. I sometimes wonder what would have been the result if John Clare could have taken on the task.

Homer raises another issue that Pope illustrates by his failure. What is the writer to do when the text is not a written one? For where Pope wrote, Homer sang. His was an oral art, in which memory and improvisation were talents that are not used by the deliberate, self-examining, word-by-word progress of ink over paper. The word in the air is not the same word on the page. The storyteller meets the same problem now in a different guise: in the writing of dialogue, which is never mere transcription of a tape recording. This was brought home to me when I adapted my novel, Red Shift, for film. When the book was published, a frequent critical reaction was that it was not prose but a script. However, in the adaptation most of the dialogue had to be rewritten. What did several unnoticed jobs in the book, would not work for the camera.

So the chasm between literate Pope and preliterate Homer is valuable because we can see it. But the chasm is always there for every writer, too wide, and the translator’s bridge too slender.

For the translator, the storyteller, there are the questions: what is the story and what words can tell it? We must add a question for ourselves: what does the story require of the teller? That is: what skills has the writer to deploy?

Since the purpose of language is to communicate, the writer must at least start from a shared ground with the reader. The place for worthwhile experiment to begin is in the middle of the mainstream. Linguistic and cultural crafts must be not so much simplified thereby as embraced. It is not enough to know. It is not enough to feel. The disciplines of heart and head, emotion and intellect, must run true together: the heart, to remain open to the potential of our humanity; the head to control, select, focus and give form to the expression of that potential. A third necessity is that the writer should have authority: not the authority of a reputation, but the authority of experience. Without that experience, judgment is suspect, the necessary iconoclasm a mischief. In order to control the vision, the gift, the work, or whatever term we care to use, the writer is required to harness an untrammelled receptivity to a strict intellectual vigour. It is not necesary to be able to analyse what one is doing, as I am attempting now. Indeed, for some it may be inhibiting; but for others, such analysis is a positive knowledge, leading to a refinement of technique and thereby achievement.

Already we have a picture of a dynamic union of opposites: heart and head, emotion and intellect: not the one subservient to the other, but the two integrated. It is the tension of the paradox, and the paradox must be active within the writer. Yet when I look around I do not see it; and so, you may take this as a Black Paper of culture. I do fear for the decadent generation. I am not simply being middle aged. I am not blind to, or rejecting, new values. I am crying out against loss.

Let me make the questions personal: what is my story and what words can tell it? The words for me must be English words; and a strength of English is its ability to draw for enrichment on both Germanic and Romance vocabularies. The English themselves have no clear view of this. We tend to assume (because they come late in our infant learning) that words of Romance origin are intrinsically superior to those of Germanic. Certainly, when I look at my own Primary School essays, it is the use of the Romance word that has won for me the teacher’s approving tick. But, in evolved English, the assumption is wrong. The two roots have become responsible for separate tasks.

We use the Germanic when we want to be direct, close, honest: such words as “love”, “warm” “come”, “go”, “hate”, “thank”, “fear”. The Romance words are used when we want to keep feeling at a distance, so that we may articulate with precision: “amity”, “exacerbate”, “propinquity”, “evacuate”, “obloquy”, “gratitude”, “presentiment”. Romance, with its distancing effect and polysyllabic intricacies, can also conceal, so that the result is not ambivalence but opacity. Extreme cases are to be found in political and military gobbledygook, when Madison Avenue gets into bed with Death: Thus death itself is a “zero survivability situation”, explosion is “energetic disassembly”; and we do not see human flesh in “maximise harrassment and interdiction” or “terminate with extreme prejudice”.

Romance is rodent, nibbled on the lips. Germanic is resonant, from the belly. It is also simple, and, through its simplicity, ambivalent: once more the paradox.

A more general aspect of English is that vowels may be seen to represent emotion and consonants to represent thought. We are able to communicate our feelings in speech without a written statement when the vowels are omitted. The head defines the heart, and together they make the word.

A large vocabulary is another characteristic of English. English contains some 490,000 words, plus another 300,000 technical terms: more than three-quarters of a million fragments of Babel. Studies show that no one uses more than 60,000 words; that is, the most fluent English speakers use less than an eighth of the language. My own vocabulary is about 40,000 words: 7 per cent of what is available to me.

British children by the age of five use about 2,000 words; by the age of nine, 6,000 (or 8,000, if encouraged to read). By the age of twelve, the child will have a vocabulary of 12,000 words; which is that of half the adult population of all ages. 12,000 words: 2.4 per cent of the language is spoken by 75 per cent of the population. They are rough figures, but even an approximation does not hide the discrepancy.

The purpose of language is to communicate. How can I, with a vocabulary three times bigger than that of three-quarters of my fellows, choose the words that we have in common? The question is unreal. I pose it in order to draw attention to the nature of imaginative writing. My experience over twenty-seven years is that richness of content varies inversely with complexity of language. The more simply I write, the more I can say. The more open the prose as the result of clarity, the more room there is for you the reader to bring something of yourself to the act of translating the story from my subjectivity to your own. It is here that reading becomes a creative act. The reason why I have no dilemma over choosing the one shared word in three is that the vocabulary I use in writing is almost identical to the 12,000 words of childhood and of most adults. They are the words of conversation rather than of intellectual debate; concrete rather than abstract; Germanic rather than Romance.

Through a preference for the simple and the ambivalent and the clear, the relatively sophisticated mind arrives at a choice of vocabulary that coincides with that of the relatively less sophisticated mind. It is in the deployment of the word that the difference and the sophistication lie. And, by deployment, by cunning, I am able to choose words in addition that are not shared and to place them without confusion and with implicit meaning, so that they are scarcely noticed, but the reader is enriched. It is a beauty of English. Yet I could be critical. English, for all its power, has mislaid its soul. English, despite my fluency, is not my own.

To make sense of what I mean, here is a little of my background, which is a background still common to many children in Britain today. I come from a line of working-class rural craftsmen in Cheshire, and was the first to benefit from the Education Act of 1944, which enabled me to go to the school with the highest academic standards in the country, and from there to Oxford University. Manchester Grammar School had at that time no English department. English, as a main subject, was for the few who could not master the literature of a foreign tongue. My ability lay in Latin and Greek. When I came to peer at English from the disdainful heights of the Acropolis, I saw only a verbal pulp. No writing, after The Tempest, had much to say to me. I was not surprised. Modern English, I would have said if I had thought about it, was a partial creole of Latin, and little more. My true discovery of English began some time after I had started to write.

I was reading, voluntarily, the text of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; and I wondered why there were so many footnotes. My grandfather was an unlettered smith, but he would have not needed all these footnotes if a native speaker had read the poem to him aloud.

– a little on a lande · a lawe as hit were;

A balg berg bi a bonke · the brimme besyde,

Bi a fors of a flode · that ferked there.

This was no Latin creole. This was what I knew as “talking broad’. I had had my mouth washed out with carbolic soap for speaking that way when I was five years old. The Hopi, and other peoples, report the same treatment today.

Hit hade a hole on the ende · and on ayther syde,

And overgrowen with gresse · in glodes aywhere,

And al was holwe inwith · nobbut a cave,

Or a crevisse of an old cragge, · . . .

Every generation needs its voice, but here was I, at home in the fourteenth century, and finding the English of later centuries comparatively alien, unrewarding.

“Yon’s a grand bit of stuff,” my father said when I read a passage to him, which he understood completely. “I recollect as Ozzie Leah were just the same.” “And that’s what all our clothing coupons went on, to get you your school uniform?” said my mother. Something had gone wrong. “Is there any more?” said my father.

I realised that I had been taught (if only by default) to suppress, and even to deride, my primary native tongue. Standard Received English had been imposed on me, and I had clung to it, so that I could be educated and could use that education. Gain had been bought with loss.

This sense of loss, I found later, had been expressed, albeit patronisingly, long before I could feel sorry for myself. Roger Wilbraham, a landed gentleman, read a paper before the Society of Antiquaries on 8 May 1817, in which he made a plea for what he called Provincial Glossaries. He said:

“‘Provincial Glossaries’, accompanied by an explanation of the sense in which each of them still continues to be used in the districts to which they belong, would be of essential service in explaining many obscure terms in our early poets, the true meaning of which, although it may have puzzled and bewildered the most acute and learned of our Commentators, would perhaps be perfectly intelligible to a Cheshire clown.”

Wilbraham was not wrong.

“And I shal stonde him a strok stif on this flet;

Elles thou wil dight me the dom. to dele him an other, barlay,

And yet gif him respite,

A twelmonith and a day;”

In my copy of the text there is a note on the word “barlay”: “an exclamation of obscure origin and meaning.” But, where I live, it would take only one school playtime for that exclamation to lose all obscurity and to have a precise meaning, unless you wanted another black eye. It is a truce word among local children even now.

Years after my surprised reading of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Professor Ralph Elliott, Master of University House at the Australian National University, told me that I could be the first writer in 600 years to emerge from the same linguistic stock as the Gawain poet and to draw on the same landscape for its expression. Then I felt humbled, and, above all, responsible; responsible for both my dialects, and for their feeding. I saw, too, why little after The Tempest in English literature had said anything to me. It was an aspect of the Age of Reason that had committed the nuisance, and the nuisance was not only linguistic but social.

When the English, through Puritanism, tried to clarify their theology, they demystified the Church, and also cut themselves off from their national psyche; and a culture that wounds its psyche is in danger. The English disintegrated heart from head, and set about building a new order from materials foreign in space and time: the Classical Mediterranean. But, at the same time, they instinctively tried to grab back the supernatural. The supernatural was forbidden. It did not exist. That is the tension within Hamlet: “If only the silly boy hadn’t gone on the battlements, none of this need have happened.”

Just as I would claim that the English language benefits from the fact of having both Romance and Germanic roots, so I would claim that all language is fed from the roots that are social. But those roots were incidentally denied us by the sweep of the Puritan revolution. No distinction was made. Our folk memory was dubbed a heresy. The Ancient World was the pattern for men of letters, and the written word spoke in terms of that pattern. Education in the Humanities was education in Latin and Greek. English style came from the library, not from the land; and the effect, despite the Romantic Movement, has continued to this day.

Yet many British children share the experience of being born into one dialect and growing into another, and, since the Education Act of 1944, we have had an increased flow of ability from the working class into the Arts. The result has been singularly depressing. We discovered our riches, so long abused, and we abused them further by reacting against the precepts of discipline inherent in Classical Art as mindlessly as the Puritan revolution had suppressed our dreams.

Generally speaking, among the newly educated, the historical inability of the working class to invest time and effort without an immediate return has joined with the historical opportunism of the middle class and has produced a disdain for controlled and structured form. Excellence is not pursued. We are in a phase without direction, the heart ruling the head. It is most noticeable in theatre and in television, where surface brilliance is mistaken for substance, and verbal maundering is held to be reality. These are the wages of universal partial education. Now, to be cultured, it is enough to be vulgar. We are still reduced.

More sinister, this obscenity is creeping into all fields of expression by its gaining the trappings of propriety. The worst vandalisms are given the imprimatur of “Political Correctness”. I know nothing of this phenomenon’s rectitude, nor of its gubernation, but I see it more as “Ignorance and Uglification of English”.

The whole rationale of what was happening to a great culture, which I have done no more than touch on here, was laid before me when I read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The irony was savage. I had been educated to articulate what that education had cost. But I was fortunate. I had a lifeline. I could get back.

The physical immobility of my family was the lifeline. My family is so rooted that it ignores social classification by others. On one square mile of Cheshire hillside, the Garners are. And this sense of fusion with a land rescued me.

The education that had made me a stranger to my own people, yet had shown me no acceptable alternative, did increase my understanding of that hill. The awareness of place that was my birthright was increased by the opening of my mind to the physical sciences and to the metaphors of stability and of change that were given by that hill. Until I came to terms with the paradox I was denied, and myself denied, the people. But those people had their analogue in the land, and towards that root I began to move the stem of the intellect grown hydroponically in the academic hothouse. The process has taken twenty-seven years, so far; and my writing is the result.

It is a writing prompted by a feeling of outrage personal, social, political and linguistic. Yet, if any of it were to show overtly on the page, it would defeat itself. My way is to tell stories.

It may be enlightening, or at least entertaining, to illustrate what I mean. My primary tongue, which I share with several million other people, a number greater than the population of Estonia, a country with a substantial literature, I would call North-West Mercian. My secondary tongue is Standard English, which is a dialect of the seat of power, London. Both are valid. Both can be described. Standard English, because of its dominance has the greater number of abstract words. North-West Mercian is the more concrete, with little of the Romance in its vocabulary, and native speakers think of it as “talking broad”, and will not use it, out of a xenophobic pride and a sense of a last privacy, in the presence of social strangers. Social strangers treat it as a barbarism. There are differences between the dialects; but they are little more than differences. Neither is superior to the other.

In the sixteenth century, English achieved an elegance of Germanic and Romance integration that it has not recaptured. We respond instinctively to its excellence. The Bible had the good fortune to be translated into this excellence, and the debility of English thereafter is plotted in all subsequent failures to improve on that text. Here is a short passage from the King James’ Bible and its equivalent in North-West Mercian, which I shall have to write in a phonetic abomination in order for it to be understood. But, spoken, it is poetry as is the other.

And Boaz said unto her, “At mealtime come thou hither, and eat of the bread, and dip thy morsel in the vinegar.” And she sat beside the reapers: and she reached out her parched corn, and she did eat, and was sufficed, and left.

And when she had risen up to glean, Boaz commanded his young men, saying, “Let her glean among the sheaves and reproach her not:

“And let fall some handfuls of purpose for her, and leave them, that she may glean them, and rebuke her not.”

So she gleaned in the field until even, and beat out that she had gleaned; and it was about an ephah of barley.

North-West Mercian:

Un Boaz sed to ur, “Ut baggintaym, thay kum eyur, un av sum u’ th’ bread, un dip thi bit u’ meet i’ th’ alliger.” Un oo sit ursel dayn usayd u’ th’ reepers; un oo raut ur parcht kuurn, un oo et it, un ad ur filt, un went uwee.

Un wen oo wuz gotten up fer t’ songger, Boaz gy’en aurders t’ iz yungg yooths, sez ay, “Lerrer songger reyt umungg th’ kivvers, un dunner yay skuwl er.

“Un let faw sum antlz u’ purpus fer er, un leeuv sum fer er fer t’ leeze um, un dunner sneep er.”

“So ur songgert in th’ felt ter th’ neet, un oo bumpt wor oo songgert, un it koom ter ubayt too mishur u’ barley.

The language of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is still spoken in the North-West of England today; but it has no voice in modern literature. The detriment works both ways. Modern literature does not feed from its soil. North-West Mercian is not illiterate, nor preliterate; it has been rendered non-literate and non-functional. I have just demonstrated its failure to communicate anything other than an emotion.

It would be retrogressive, a negation, if I were to try to impose North-West Mercian on the speakers of Standard English; and I should deservedly fail. Writer and language are involved in the process of history, and in history Standard English has become supreme over all regional dialects, of which North-West Mercian is but one. How then can I feed the two, to both of which I must own?

The answer is seen only with hindsight. Each step has appeared at the time to be simple expediency, in order to tell a story. One image, though, has remained: the awareness of standing between two cultures represented by two dialects: the concrete, direct culture from which I was removed and to which I could not return, even if I would; and the culture of abstract, conceptual thought, which had no root in me, but in which I have grown and which I cherish. It was self-awareness without self-pity, but full of violence. I knew that I had to hold on to that violence, and, somehow, by channelling them through me, make the negative energies positive.

All my writing has been fuelled by the instinctive drive to speak with a true and Northern voice integrated with the language of literary fluency, because I need both if I am to span my story. It was instinctive, not conscious, and I have only recently become aware enough to define the nuances.

First efforts were crude and embarrassing: a debased phonetic dialogue in the nineteenth-century manner. Such awkwardness gets in the way, translates nothing. Phonetic spelling condescends. Phonetic spelling is not good enough in its representation of the speakers. It is ugly to look at, bespattered with apostrophes, as my example from The Bible has shown.

It is the sign of a writer alienated from his subject and linguistically unschooled. Worst of all, in my writing and in that of others, the result, when incorporated in dialogue as an attempt to promote character, is to reduce demotic culture to a mockery; to render quaint, at best, the people we should serve. The novel, I would suggest, is not the place for phonetics.

Dialect vocabulary may be used to enrich a text, but it should be used sparingly, with the greatest precision, with accurate deployment, otherwise the balance is tipped through the absurd to the obscure. The art is to create the illusion of demotic rather than to reproduce it. The quality of North-West Mercian, as of all dialects, lies not in the individual words but in the cadence, in the music of it all.

So what words can tell my story? The words are the language, heart and head: a language at once idiosyncratic and universal, in the full growth of the disciplined mind, fed from a deep root. To employ one without the other is to be fluent with nothing to say; or to have everything to say, and no adequate means of saying it. Yet, for historical reasons, those are the alternatives for the artist in Britain today, unless he or she, consciously or unconsciously, wages total war, by which I mean total life, on the divisive forces within the individual and within society.

The conflict of the paradox must consume, but not destroy. It must be grasped until, leached of hurt, it is a clear and positive force, matched to an equal clarity of prose. It must be rage: rage for, not rage against. That way, although there is no guarantee, a new language may result that is neither false nor sentimental, that can stand without risk of degradation, without loss of ambivalence, and be at all times complete. Twenty-seven years have not given me that language, but at least I feel that I know some of its qualities, and where to look for them in myself.

Here is a tentative example, from The Aimer Gate. It describes, as did the earlier passage from the Bible, a harvest field:

The men stood in a line, at the field edge, facing the hill, Ozzie on the outside, and began the swing. It was a slow swing, scythes and men like a big clock, back and to, back and to, against the hill they walked. They walked and swung, hips forward, letting the weight cut. It was as if they were walking in a yellow water before them. Each blade came up in time with each blade, at Ozzie’s march, for if they ever got out of time the blades would cut flesh and bone.

Behind each man the corn swarf lay like silk in the light of poppies. And the women gathered the swarf into sheaves, stacked sheaves into kivvers. Six sheaves stood to a kivver, and the kivvers must stand till the church bells had rung over them three times. Three weeks to harvest: but first was the getting.

Standard English and North-West Mercian are there combined in syntax, vocabulary and cadence. They speak for me, as the head to the heart; as the consonant to the vowel; as Romance to Germanic; as the stem to the root.

From such are the words formed. Now what else is the story? To answer that, I have to draw on the work of the late Professor Mircea Eliade, in whose precision of discourse I have often found my instincts to be defined.

The story that the writer must tell is no less than the truth. At the beginning, I took “art” to mean the fabrication whereby a reality may be the better revealed. I would equate “truth” with that same reality.

A true story is religious, as drama is religious. Any other fiction is didactic, instruction rather than revelation, and not what I am talking about. “Religious”, too, is a quarrelsome word. For me, “religion” describes that area of human concern for, and involvement with, the question of our being within the cosmos. The concern and involvement are often stated through the imagery of a god, or gods, or ghosts, or ancestors; but not necessarily so. Therefore, I would consider humanism, and atheism to be religious activities.

The function of the storyteller is to relate the truth in a manner that is simple; for it is rarely possible to declare the truth as it is, because the universe presents itself as a Mystery. We have to find parables, we have to tell stories to unriddle the world. It is yet another paradox. Language, no matter how finely worked, will not speak the truth. What we feel most deeply we cannot say in words. At such levels only images connect; and hence story becomes symbol.

A symbol is not a replica of an objective fact. It is not responsive to reductive analytical rationalism. A symbol is always religious and always multivalent. It has the capacity to reveal several meanings simultaneously, the unity between which is not evident on the plane of experience. This capacity to reveal a multitude of united meanings has a consequence. The symbol can reveal a perspective in which diverse realities may be linked without reduction; so that the symbolism of the moon speaks to a unity between the lunar rhythms, water, women, death and resurrection, horses, ravens, madness, the weaver’s craft and human destiny – which includes the Apollo space missions. All that is not an act of reason; but it is an act of story. Here is a dimension where paradox is resolved; for story itself is myth.

In the beginning, the earth was a desolate plain, without hills or rivers, lying in darkness. The sun, the moon and the stars were still under the earth. Above was Mam-ngata, and beneath, in a waterhole, was Binbeal.

Binbeal stirred. And the sun and the moon and the stars rose to Mam-ngata. Binbeal moved. And, with every movement, the world was made: hills, rivers and sea, and life was woken. And all this Binbeal did “altijirana nambakala”, “from his own Dreaming”; that is, from his own Eternity.

The life that Binbeal woke was eternal, but lacked form. This life became animals and men. And these, the Ancestors, were given shape and came onto the face of the new earth. And the place where each Ancestor came is sacred for ever.

That is a synthesis of a pan-Australian myth. From myth came the totemism of the Aboriginal Australian, and an awareness that amounts to symbiosis with the land. For the Australian, the Ancestor exists at the same time under the earth; in ritual objects; in places such as rocks, hills, springs, waterfalls; and as “spirit children” waiting between death and rebirth; and, most significantly, as the man in whom he is incarnate. It is a world view close to the one I discovered for myself, as a child of my family on Alderley Edge in Cheshire.

Through the mediation of myth, the Aboriginal Australian has not only a religious nobility of thought, but, coincident with the “real” earth, a mystical earth, a mystical geography, a mystical sequence of Time, a mystical history, and, through the individual, a mystical and personal responsibility for the universe.

Ritual initiation of the individual is the assumption by the individual of this knowledge and responsibility.

When an Aboriginal Australian boy is initiated into manhood, the sacred places of his People are visited, the sacred rites performed, to help the boy to remember. For this boy, this reincarnated Ancestor, has to recall the primordial time and his own most remote deeds. Through initiation, the novice discovers that he has been here already, in the Beginning, Altjira, the Dreaming. It is a Second Coming. It is a Holy Communion. To learn is to remember.

In Classical Greek the word is “anamnesis” and was first expounded to us by the father of Western philosophy, Plato. There are many differences between the Australian “altjira” and Greek “anamnesis”, but both are a spiritual activity: philosophy for the Greek; life itself for the Australian.

I am not advocating a rejection of sophisticated values in favour of “primitive” animism. I am a rationalist, a product of the Classical Mediterranean, and an inheritor of two thousand five hundred years of Western thought. I need Manchester Grammar School just as much as I need Alderley Edge. But I do need them both.

My concern, in writing and in life, is that, by developing our greatness, the intellect, we should not lose the other greatness, our capacity to Dream. The two can work side by side, even if it means that I have to imagine a railway system to get me to my desk. Achilles can walk in Altjira. Indeed he must: he has such a lot to remember.

Not least of the memories is that to live as a human being is in itself a religious act.

That is why the stories must be told. It is why Eric James had such a catalytic effect upon one of his sixth-formers; and so justified his function as a chemist, after all.

1 This lecture was delivered at the Children’s Literature Association Tenth Annual Conference, entitled “Frontiers in Children’s Literature” at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, on 15 May 1983.