CHAPTER TEN

Saving Australia

On April 18, 1942, with the concurrence of the Allied governments in hand, MacArthur formally incorporated the land, naval, and air forces in the Southwest Pacific Area into his CINCSWPA command structure. Command of land forces went to Lieutenant General Thomas Blamey, the commander of the Australian army, who had just returned from service in the Middle East. Since most SWPA troops, save around two divisions of Americans, were Australians, the War Department had instructed MacArthur to designate an Australian, and Blamey’s appointment was well received. Commander of Allied naval forces was to be Vice Admiral Herbert F. Leary, a 1905 classmate of Nimitz’s at Annapolis and the commander of a force of American, Australian, and New Zealand cruisers and destroyers charged with enforcing King’s mandate of a West-Coast-to-Australia lifeline.

The Allied Air Forces were under the command of Lieutenant General George H. Brett, who had been the commander of United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA). This was a curious choice in that Brett, whether by his own fault or not, already had two strikes against him from MacArthur’s point of view—the lack of air support in the Philippines in general and the dilapidated state of the B-17s that rescued him in particular.

Barely had MacArthur landed in Australia and given Brett the cold shoulder when he told Marshall, “I have found the Air Corps in a most disorganized condition and it is most essential as a fundamental and primary step that General Brett be relieved of his other duties [as USAFIA commander] in order properly to command and direct our air effort.”1

Major General Julian F. Barnes, who had been the commander of the forces on the Pensacola convoy, was left to command American forces in Australia, which were largely to function as the logistics and services command. Barnes’s job, short of a Japanese invasion of the Australian mainland, may have been the most important in the short term: get as many men and as much materiel to Australia as possible and put both in a position to fight.

In the spirit of Allied harmony, Marshall advised MacArthur to include a representative sample of Australian and Dutch officers among the key staff positions in his headquarters. Not only did MacArthur not do so, he also looked no further than his Bataan Gang to fill eight of the eleven top spots. It was so exclusive a fraternity that one is almost tempted to list them by the numbers of their PT boats: Dick Sutherland became chief of staff, Dick Marshall became deputy chief of staff, Charles Stivers was put in charge of G-1 (personnel), Charles Willoughby was put in charge of G-2 (intelligence), Spencer Akin was made signal officer, Hugh Casey was made engineering officer, William Marquat became the antiaircraft officer, and LeGrande Diller became the public relations officer.

Six other members of the Bataan Gang remained close: Sid Huff, as MacArthur’s personal aide, was charged in particular with taking care of Jean and little Arthur; C. H. Morhouse was on call as the general’s aide, personal physician, and sounding board regarding the health of his subordinates; Francis Wilson became Sutherland’s aide; Joseph McMicking became assistant G-2; Joe Sherr, assistant signal officer, was increasingly involved with code breaking; and youthful master sergeant Paul Rogers was Sutherland’s clerk.

The three newcomers to MacArthur’s staff were Brigadier General Stephen J. Chamberlin, Brett’s former chief of staff at USAFIA, now in charge of G-3 (operations); Colonel Lester J. Whitlock, head of G-4 (supply); and Colonel Burdette M. Fitch, adjutant general. Whitlock and Fitch had been in Australia with the USAFIA command.

As for the Australians and the Dutch, MacArthur told Marshall that he had found no qualified Dutch officers available in Australia and that the mushrooming size of the Australian army left him “no prospect of obtaining senior staff officers from the Australians.” There is, however, no record of MacArthur requesting that Blamey provide such staff members, even though there were many Australians equal to the Americans in military training who had the added advantage of wartime experience in recent operations in Africa, Europe, and Asia. As time went by, this cliquishness of MacArthur’s staff made it an American enclave and led to the subsequent disgruntlement of Australians, particularly after large numbers of Australian troops were committed to operations in New Guinea.2

A final member of the Bataan Gang, Brigadier General Harold H. George, was deployed in the field to help Brett revitalize the Allied air effort. Known as “Pursuit” George to differentiate him from Brigadier General Harold L. “Bomber” George, who was about to head the new Air Transport Command in Washington, Pursuit George flew north toward Darwin, where he had just been given command of air defenses for the Northern Territory. Upon landing at Batchelor Field to drop off an Australian major who was bumming a ride north, George and his entourage, which included veteran war correspondent Melville Jacoby, suffered tragedy. They were standing just off the runway alongside their Lockheed C-40 transport plane when two P-40s roared down the strip, taking off. The rear plane got caught in the other’s prop wash and careened out of control into George’s group. Jacoby and a lieutenant were killed instantly; George died of head and chest injuries the next morning. By some accounts, George’s death affected MacArthur more than any other during the war. Had George lived, MacArthur may well have opted to elevate him to Brett’s position.3

The choice of an Australian ground commander for MacArthur’s Allied forces also made sense because many in Australia anticipated an imminent Japanese invasion. “Experts believe that the Australian campaign will prove to be one of manoeuvre,” the Chronicle, based in Adelaide, reported within a week of MacArthur’s arrival in Melbourne. “It is considered doubtful whether General MacArthur will be able to prevent the establishment of enemy beachheads on Australia’s long, exposed coastline, since a static cordon of defence would require an astronomical number of men.”4 If the Chronicle knew of MacArthur’s ill-conceived beachhead defense plan for the Philippines, it made no mention of it.

But what were the Japanese planning? Their drive through Southeast Asia had taken most of the Philippines, save Corregidor and increasingly isolated areas throughout the southern islands, routed the Dutch from Java, and occupied the extent of the Malay Barrier from Timor west to Rangoon. Would they next look west to India or southeast to Australia? Sensing the rapid completion of Japan’s first-stage operations, Matome Ugaki, Yamamoto’s chief of staff, had posed that very question three months earlier. “What are we going to do after that?” Ugaki queried his diary. “Advance to Australia, to India, attack Hawaii, or destroy the Soviet Union at an opportune moment?”5

In mid-March, Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and his army and navy chiefs of staff tried to provide an answer by agreeing on a “General Outline of Policy of Future War Guidance.” Hopes for an early negotiated settlement with the United States had been dashed by American reaction to the Pearl Harbor attack, and as Tojo and his chiefs recognized, “It will not only be most difficult to defeat the United States and Britain in a short period, but, the war cannot be brought to an end through compromise.”

With repeated references to the need to build up the nation’s war machinery, the conclusion of the Japanese leaders was to remain on the offensive and take all measures possible to force the United States and Britain to remain on the defensive. That said, the report warned that any “invasion of India and Australia” should be decided upon only after careful study.6

Australia at the time had a population of a little more than seven million people, the majority of them clustered in the southeast, between Brisbane and Melbourne. As a member of the British Commonwealth, the country had been loyally fighting on Great Britain’s side for more than two years. Nine squadrons of the Royal Australian Air Force were scattered across the United Kingdom, the Middle East, and Malaya. Some 8,800 additional Australians were serving in the Royal Air Force. The principal ships of the Royal Australian Navy, two heavy and three light cruisers, had only recently returned to home waters after long service with the Royal Navy. The four trained and equipped divisions of the overseas Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were mostly in the Middle East, although after Pearl Harbor, British prime minister Winston Churchill slowly and reluctantly agreed to their return.7

Exposed though it appeared militarily, what Australia had going for it was scale. Sprawling over approximately three million square miles, it is roughly the size of the continental United States. Any enemy landing on the expanse of Australia’s northwestern coast would face several thousand miles of sparsely populated desert terrain before approaching the farming and industrial centers in the southeast. Just prior to MacArthur’s arrival in Australia, however, General Brett told Marshall that he was convinced that the Japanese would push forward the concentrations of ships, planes, and troops that they had used to capture Java and land them on the northwestern coast, probably at Darwin.

The Australian chiefs of staff weren’t so sure. The Japanese might indeed take Darwin, but the chiefs surmised that if they did, it would be to prevent its use as a “springboard” from which Allied troops could counterattack in the East Indies rather than as their own “stepping stone” to an invasion of Australia. Even if the latter occurred, the Japanese would find themselves relatively isolated and not that much closer to Brisbane or Melbourne than they already were at Timor.

Instead, the Australian chiefs looked at the bigger map and became convinced that the ultimate Japanese objective had to be cutting the air and shipping lanes between the United States and Australia in order to prevent Australia from becoming a major base for just the offensive operations the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters already feared. This meant that the northeastern coast of Australia, including nearby Papua, in New Guinea, might be in far more danger than Darwin and the northwestern coast were. As it turned out, the enemy agreed with them.

On March 15, army and navy representatives of the Imperial General Headquarters met to begin the careful study Tojo had assured the emperor would be undertaken with regard to an Australian strategy. Navy officers emphasized the increase in air and sea traffic between the United States and Australia and urged an invasion of the continent before it could be turned into a platform for offensive operations. But the army calculated that it would take ten or more divisions to invade and hold Australia, even if the navy could find the ships for such an attack. Such a major maneuver was likely to hamstring operations throughout the Pacific and significantly reduce mobility. With that the Imperial Japanese Navy could hardly disagree.

Thus the Japanese plan became to encircle and isolate Australia from its American allies by driving eastward through the Solomon Islands to capture New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa and cut the West-Coast-to-Australia lifeline. Doing so would isolate Australia, which in due course would drop from the Allied tree without a costly invasion.8

The foundation for this plan was already in place as, concurrent with its drives throughout the Malay Barrier, Japan had been expanding toward New Guinea from its naval bastion of Truk, in the Caroline Islands. The huge island of New Guinea, the second largest in the world (after Greenland) and approximately twice the size of California, guarded the northern approaches to Australia. It was divided into three political units: Netherlands New Guinea, occupying the western half of the island; Northeast New Guinea and the adjacent Bismarck Archipelago, which were Australian mandates from German spoils at the end of World War I; and Papua, an Australian territory roughly separated from Northeast New Guinea by the rugged Owen Stanley Range. Papua extended eastward to Port Moresby and the Louisiade Archipelago, in the northern reaches of the Coral Sea. The sprawling harbor at Rabaul, on the island of New Britain, in the Bismarck Archipelago, was a particularly inviting prize, a place from which to move into the Solomon Islands.

The Imperial General Headquarters of the Japanese army ordered a force of around five thousand men drawn from the Fifty-Fifth Infantry Division, called the South Seas Detachment, to embark from Guam, capture Rabaul, then move south from there. These forces had captured Guam just days after Pearl Harbor, and among the ships that escorted its transports south were the aircraft carriers Kaga and Akagi. This invasion convoy stood off Rabaul on the night of January 22–23, 1942, and commenced landing operations shortly after midnight.

Resisting mostly with mortars and machine guns, the 1,400-man Australian garrison was overwhelmed within hours. As on Bataan, many of the defenders were captured and massacred, although around four hundred of them made their way to the coast and were evacuated by small boats from New Guinea. The resulting Japanese occupation of Rabaul posed a looming threat to northeastern Australia, given Rabaul’s harbor, central location, and two developed airfields within easy range of the northern coast of New Guinea and the western Solomons.9

The next stops for the South Seas Detachment were Lae and Salamaua, opposite New Britain, on the northern coast of New Guinea. Although Lae was born as a gold-rush town in the 1920s, its main claim to fame was that it served as a refueling stop in 1937 for Amelia Earhart on one of the final legs of her ill-fated around-the-world attempt. It was her last stop prior to her disappearance, en route to Howland Island. Proving that the United States was not the only country with interservice rivalries, Japanese forces reached an agreement that navy troops would assault Lae while army troops took Salamaua.

The landings were delayed when the US aircraft carrier Lexington and an accompanying task force of four heavy cruisers and ten destroyers made a threatening foray northeast of Rabaul. Finally, in the wee hours of March 8, a battalion of the Japanese 144th Infantry Regiment landed unopposed at Salamaua. A few hours later, naval troops did the same at Lae. What few locals were there to oppose the landings melted into the jungle.

The Lexington soon returned, this time from the southeast in concert with the carrier Yorktown. The carriers sailed west of Port Moresby and—beyond the range of Japanese land-based air from Rabaul—dispatched air attacks from the Gulf of Papua directly over the Owen Stanley Range against the new beachheads on the northern coast. Damage reports varied, but in the end three transports and one converted minesweeper were sunk, and a transport, seaplane tender, minelayer, and two destroyers sustained medium damage.

These results were easily the greatest loss of ships yet suffered by the Japanese. But only one attacking aircraft out of 104 failed to return to the American carriers. MacArthur routinely groused about a do-nothing American navy, but here was strong evidence that Nimitz was using his carriers carefully but aggressively—a strategy that King termed “calculated risk.”

If nothing else, this carrier raid seasoned American airmen and sailors in battle and prepared them for bigger things to come, but in retrospect, there was much more to it than that. The foray by the Lexington and Yorktown is largely unremembered, being overshadowed by the Coral Sea battle sixty days later. But the loss of transports and the evident need for carriers to cover future landings caused the Japanese to postpone their thrusts into the Solomons and against Port Moresby until carriers could be returned from operations in the Indian Ocean. At a time when mere days meant a great deal in terms of increasing Allied preparedness, a month’s delay was significant.10

Despite the showing of the Lexington and Yorktown off New Guinea, MacArthur pressed for carriers under his own command to augment Admiral Leary’s meager naval forces. Told on April 27 that “all available carriers are now being employed on indispensable tasks,”11 MacArthur continued his demands for more troops and resources. Dissatisfied with Marshall’s responses, delivered through the established chain of command, MacArthur turned to Australian prime minister John Curtin and attempted to apply political pressure, a frequent MacArthur tactic.

MacArthur’s relationship with Curtin was an interesting one. Politically, they were polar opposites. While conservative MacArthur was leading troops with the Rainbow Division during World War I, liberal Curtin had been the editor of the Westralian Worker in Perth and an outspoken opponent of conscription. Five years MacArthur’s junior, Curtin became prime minister of a coalition government with a narrow Labor plurality on October 7, 1941. Without military training, he had nonetheless spent years arguing for stronger Australian defenses and less reliance on the British fleet.12

Curtin’s skepticism proved well placed after Pearl Harbor and the loss of the Prince of Wales and Repulse. In his New Year’s message, a few weeks later, Curtin told his countrymen: “Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.” Great Britain was preoccupied and could hold on without Australia, Curtin continued, so Australians must “exert all our energies towards the shaping of a plan, with the United States as its keystone, which will give our country some confidence of being able to hold out until the tide of battle swings against the enemy.”13

Perhaps the critical moment when that swing began, politically if not militarily, had been MacArthur’s arrival in Australia. While bookish Curtin would rouse his fellow Australians with his own brand of Churchill-like speeches, MacArthur’s display of assurance and resolve from the moment he stepped from his railcar in Melbourne helped bolster the same in Curtin. How much MacArthur allowed his ego to cast him in the role of Australia’s savior differs with the telling.

Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Wilkinson, MacArthur’s first British liaison officer in Australia, quoted MacArthur as saying that “Curtin and Co. more or less offered him the country on a platter when he arrived from the Philippines.”14 MacArthur readily told Curtin, however, that “though the American people were animated by a warm friendship for Australia, their purpose in building up forces in the Commonwealth was not so much from interest in Australia but from its utility as a base from which to hit Japan.”15

Meeting with Curtin late in April, MacArthur professed his bitter disappointment with the “utterly inadequate” assistance he was receiving from Washington and suggested that Curtin plead with Churchill for an aircraft carrier, two British divisions then en route to India, and an increase in British shipping assigned to the West Coast–Australia lifeline. Curtin took up the reins and immediately passed these requests on to Churchill, saying he was doing so at MacArthur’s request.

Upon the receipt of Curtin’s letter, Churchill did what most leaders do when a subordinate of someone with whom they have an equal and trusted working relationship appears to be “out of channels”: he promptly passed the Curtin/MacArthur letter on to Roosevelt, saying, “I should be glad to know whether these requirements have been approved by you… and whether General MacArthur has any authority from the United States for taking such a line.”16

The answer, of course, was a firm no. Marshall immediately told MacArthur that such indirect tactics on his part served only to create confusion, and he “requested that all communications to which you are a party and which relate to strategy and major reinforcements be addressed only to the war department.”17

“I am embarrassed by your [letter],” MacArthur disingenuously began his reply, “which seems to imply some breach of frankness on my part. I can assure you that nothing is further from my thoughts.” But then MacArthur launched into a four-page missive that left no doubt about the way he really felt—that Marshall and Roosevelt were the ones who should be embarrassed by their lack of support. Professing to “know nothing of the communications between the prime ministers of Great Britain and Australia,” MacArthur pointedly told Marshall that he had explained fully to Curtin “the limitations placed upon me by my directive to the effect that I am responsible neither for grand strategy nor for the allocation of resources from the British Empire or from the United States.”

Noting that Curtin had asked his advice and that he deemed open communications with the Australian prime minister to be part of his charge, MacArthur claimed to have the confidence of both the Australian government and people “due largely to the lack of any attempt on my part at intrigue or reservation.” They were rallying to him, and whatever he did was only in response to the overarching exigency of defending Australia. “It is hard to conceive the unanimity and intense feeling which animates every element of Australian society in its belief that proper protective measures for the safety of this continent are not being taken,” MacArthur concluded. “It represents an avalanche of public opinion that nothing can suppress.”18

When Marshall received this communiqué, it was clear that it was time for another personal letter from Roosevelt. “I fully appreciate the difficulties of your position,” FDR began. “They are the same kind of difficulties which I am having with the Russians, British, Canadians, Mexicans, Indians, Persians and others at different points of the compass.” No one was “wholly satisfied,” but the president noted he had managed to keep all of them “reasonably satisfied” and avoid “any real rows.”

What Roosevelt did not say to MacArthur in so many words is that Marshall had just returned from England and agreed with the British that top priority would be given to Operation Bolero, the buildup of American troops and materiel in England in anticipation of an invasion of France in 1943. This “second front” in the war with Germany was deemed critical, as was the continued supply of munitions to the ally who was then bearing the brunt of the “first front.”

On that issue, Roosevelt was quite candid with MacArthur: “In the matter of Grand Strategy,” FDR wrote, “I find it difficult this spring and summer to get away from the simple fact that the Russian armies are killing more Axis personnel and destroying more Axis material than all the other 25 United Nations put together. Therefore, it has seemed wholly logical to support the great Russian effort in 1942 by seeking to get all munitions to them that we possibly can, and also to develop plans aimed at diverting German land and air forces from the Russian front.”

MacArthur would feel this effect, Roosevelt acknowledged, but he also reaffirmed that “we will continue to send you all the air strength we possibly can” and work to secure the line of communication between the United States and Australia. “I see no reason why you should not continue discussion of military matters with Australian Prime Minister,” Roosevelt concluded, “but I hope you will try to have him treat them as confidential matters and not use them for public messages or for appeals to Churchill and me.” MacArthur had to be “an ambassador as well as supreme commander.”19

Despite Roosevelt’s words and those of others, MacArthur would never accept the reality that his command was only a secondary front—not even “the second front.” In a global war, MacArthur presided over a relatively small piece. Nonetheless, his Southwest Pacific Area stretched 3,700 miles from the Indian Ocean to longitude 160˚ east, in the Solomon Islands, and 4,700 miles from Tasmania north to Luzon, an area almost twice the size of Europe. Regardless of the emphasis of the central Pacific in the vestiges of Plan Orange, Japan’s rapid dominance throughout the Southwest Pacific Area and the importance of the natural resources of the East Indies to Japan’s war economy made the Southwest Pacific heavily contested. Pragmatists did not question the commitment to Germany First, but MacArthur had an unlikely ally in his emphasis on the Pacific, even if he never fully recognized it.

The chief champion of pouring resources into the Pacific—even as he managed a two-ocean war and fought the battle against German U-boats in the North Atlantic—was Admiral Ernest J. King. While King went out of his way to avoid the wartime publicity that MacArthur courted—fearing such attention could not help but telegraph future operations to the enemy—the admiral and the general were far more alike than either would have admitted.

Both men were supreme egotists, each certain that his way was the right way. Both were avid readers of military history, biography, and strategy and took from that an exceptionally high opinion of their own military acumen. Both rubbed a good many subordinates the wrong way with a grating manner, a practiced sense of entitlement, and strict expectations, yet each also had his inner circles of devoted followers. Both were said to have a soft underside—particularly toward their children. But first and foremost, both men were determined fighters.

A 1901 graduate of Annapolis, King served his first tour in the Far East in time to observe the Russo-Japanese War. Staff positions during World War I gave him a close look at emerging developments in submarines and aviation as well as a lesson or two in working with allies. Between the wars, King pioneered submarine rescue operations, learned to fly, and embraced the emergence of the aircraft carrier. He pushed night carrier operations, introduced combat air patrols (CAP) circling overhead, and war-gamed surprise carrier attacks against the Hawaiian Islands.

When William D. Leahy retired as chief of naval operations in 1939, King desperately wanted the job, but his abrasive style and advocacy of naval aviation in the face of the still-dominant battleship crowd cost him the position. Relegated to the navy’s General Board as the final step before retirement, King found a champion in Roosevelt’s secretary of the navy, Frank Knox. At Knox’s urging, Roosevelt gave King command of the North Atlantic fleet as it struggled to shepherd lend-lease convoys to Great Britain in an icy, undeclared war with German U-boats. After Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt and Knox immediately summoned King to Washington to command the United States Fleet. Among King’s first actions was to dispatch Chester W. Nimitz to command the Pacific Fleet.20

Nimitz was the polar opposite of MacArthur and King in both personality and command style. Born in the sand hills of Texas west of Austin, Nimitz went to Annapolis only after there were no openings at West Point; otherwise, he would have been two years behind MacArthur there. Nimitz did not, however, enjoy the meteoric rise that family connections and World War I afforded MacArthur, and, while given the four stars of a full admiral when he assumed command of the Pacific Fleet, Nimitz was far below MacArthur in seniority.

His early specialty had been converting the neophyte American submarine force from gasoline to diesel. He supervised the construction of the submarine base at Pearl Harbor in the early 1920s, anticipated aircraft carriers as the center of the fleet while studying at the Naval War College, and taught Naval ROTC at the University of California, Berkeley. His sea commands included the heavy cruiser Augusta, then the flagship of the Asiatic Fleet.

Whether in the classroom or on the bridge, Nimitz taught by example, not tirade; he led men rather than drove them. He had a razor-sharp mind for details as well as an adroit sense of overall strategy. In a trio of keen intellects, Nimitz may have been smarter than either MacArthur or King. He certainly was far more humble, self-effacing, and diplomatic, a dedicated team player. Never afraid to argue his points, Nimitz nonetheless accepted the command decisions of his superiors and gave his all to execute them. He expected the same from his subordinates: discussion but full commitment to his final decisions.21

Having been chief of the navy’s Bureau of Navigation—despite its name, essentially the personnel branch—when tapped to be CINCPAC, Nimitz had an in-depth understanding of the strengths and weakness of the officers who were flooding into the Pacific. What he shared most with MacArthur and King, however, was that he, too, was a fighter. He hated to lose, and he fully embraced King’s plans for offensive operations as early as was practical.

King instructed Nimitz that his two primary missions were to hold Hawaii and maintain the West-Coast-to-Australia lifeline, but King had also made it clear to Roosevelt and Marshall that he viewed the best defense to be a strong offense. To his instructions to Nimitz, King proposed adding a third task. “The general scheme or concept of operations,” King wrote, “is not only to protect the lines of communications with Australia but, in so doing, to set up ‘strong points’ from which a step-by-step general advance can be made through the New Hebrides, Solomons, and the Bismarck Archipelago.”

Marshall immediately seized on the words “general advance” and questioned how, with the priorities of Germany First, King could even consider a general advance in the Pacific. But King maintained that an offensive rather than passive line of operations would “draw the Japanese forces there to oppose it, thus relieving pressure elsewhere, whether in Hawaii, [the Southwest Pacific], Alaska, or even India.”22 Marshall warmed to the plan; Roosevelt embraced it, providing it did not disrupt Bolero; and King’s strategy for offensive operations in the Pacific—as opposed to defensive containment—was adopted.

To be sure, there would always be friction between the US Navy’s South Pacific command and MacArthur’s SWPA over allocation of resources, but had not King aggressively pushed for offensive operations and done his best to increase resources throughout the general Pacific theater, MacArthur might have spent the war simply ensuring that the Japanese did not invade Australia. MacArthur was to push the limits of his initial operational orders and, rather than simply “prepare to take the offensive” (emphasis added), plan and execute offensive operations: King’s aggressive stance gave him the cover to do so. MacArthur would never have admitted that, and King was not particularly thinking of aiding MacArthur when he crafted his strategy, but it had that effect.

MacArthur’s PR machine needed no cover: it was already on the offensive. In fact, under the auspices of Pick Diller, with heavy contributions from MacArthur himself, it had continued its Manila and Corregidor practice of cranking out ubiquitous press releases from the moment the Bataan Gang landed at Batchelor Field. On the one hand, Japanese propaganda boasted verbosely about the triumphs—real and imagined—of the Japanese army and navy, and MacArthur appears to have felt that part of his charge was to counter this stream with propaganda of his own. But on the other hand, his communications were released so quickly that they frequently did not have all the facts straight. In addition, they sometimes reported results for operations over which MacArthur had no direct command, and their revelations threatened to undercut the top-secret code-breaking operations being performed not only by the US Navy but also by his own intelligence unit.

Marshall called MacArthur to task for just those reasons after a press release datelined “Allied Headquarters, Australia, April 27,” reported in great detail on the buildup of Japanese forces at Rabaul. The Japanese had to suspect, Marshall told MacArthur, that reconnaissance alone could not have gathered such information and that their codes were compromised, if not broken. “This together with previous incidents,” Marshall admonished, “indicates that censorship of news emanating from Australia including your headquarters is in need of complete revision.”23

MacArthur replied that after what he termed had been “a careful check,” the material in question had not been announced “by direct communiqué” from his headquarters. He professed to have Marshall believe that the term “Allied Headquarters, Australia,” had been loosely appropriated by reporters—despite MacArthur being so particular about such things—and that its use did not imply his control or approval. MacArthur blamed an Australian censor for the release, then pointedly noted, “As I have explained previously, it is utterly impossible for me under the authority I possess to impose total censorship in this foreign country.”24 But then the stakes got higher.

The US Navy’s code-breaking unit in the Philippines, code-named Cast, had been a high-priority evacuation from Corregidor early in February. A similar army unit, Station 6, delayed leaving until after MacArthur’s departure but was partially evacuated late in March. Both units reassembled in Melbourne and continued deciphering signal intelligence. The center of Pacific intelligence against the Japanese, however, was Station Hypo, located at Pearl Harbor under the leadership of Lieutenant Commander Joseph J. Rochefort.

Based on Rochefort’s intercepts, Commander Edwin T. Layton, Nimitz’s chief intelligence officer, sent a message through channels that advised Sutherland that the Japanese appeared to be preparing to extend their reach from Rabaul and that Port Moresby might be attacked by sea as early as April 21. MacArthur ordered an aerial reconnaissance of Simpson Harbor at Rabaul, but General Brett’s pilots found no concentration of ships that would suggest a major amphibious operation.

On April 22 in Hawaii, Layton reaffirmed his suspicions to Nimitz: despite the reconnaissance results, he still anticipated an imminent Japanese offensive from Rabaul, either against southern New Guinea or eastward into the Solomons. Given the predilection of the Japanese navy to advance under the protection of land-based air—the Battle of Midway was soon to be a major exception—Layton suggested that the target was Port Moresby.

Willoughby read the same decoded message and came to a different conclusion. Noting the reported presence of four Japanese carriers, Willoughby predicted an attack beyond the cover of land-based air, either against the northeastern coast of Australia or on New Caledonia, the critical link in the West-Coast-to-Australia lifeline. When Port Moresby remained quiet, additional naval intelligence convinced Sutherland that the attack had only been delayed a week or two. Willoughby backed off his appraisal and revised it: thereafter he expected a landing in division strength at Port Moresby between May 5 and May 10.25

In response to Layton’s intelligence, Nimitz ordered the carriers Lexington and Yorktown, under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, to rendezvous and venture into the Coral Sea. Convinced by Layton that the Japanese were making a major offensive thrust, Nimitz also ordered the carriers Enterprise and Hornet, which were returning from the Doolittle Raid under Bill Halsey’s command, to join Fletcher. Bunching the only four American carriers in the Pacific into one force marked a major shift in the way the US Navy deployed its carriers—even though Enterprise and Hornet would arrive too late to engage—and, to Nimitz’s credit, it signaled his emergence as an aggressive theater commander. Nonetheless, it took Nimitz’s muscular lobbying with King to persuade him to do the bundling—and to do it without the millstone of lumbering battleships slowing him down.26

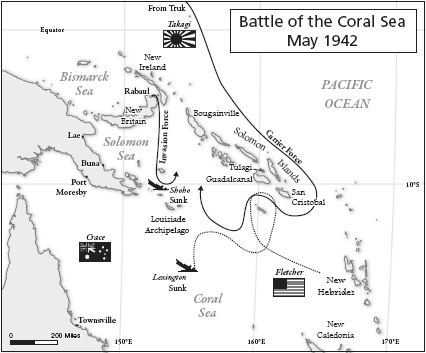

The Japanese sortied three main groups: a battle, or “striking,” force from Truk under Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi, including the carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku; an invasion force from Rabaul bound for Port Moresby containing seven destroyers, five transports, and several seaplane tenders; and an escort, or “covering,” force that shadowed the invasion force and included the light carrier Shoho along with four heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a squadron of submarines.27

The architect of the Japanese attack was Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue, the commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Fourth Fleet, based at Truk. In addition to Port Moresby, Inoue had his eye on a seaplane facility at tiny Gavutu, near the island of Tulagi, at the far eastern end of the Solomons. Capturing Gavutu and Tulagi would allow Japanese seaplanes to patrol the eastern reaches of the Coral Sea while an airfield for land-based air was constructed nearby on the larger island of Guadalcanal.

As a small force wove its way through the Solomons from Rabaul and made the Tulagi landings, Takagi’s striking force would sweep around the eastern end of the islands, sprint westward across the Coral Sea, and launch a surprise attack against the Allied airfields at Townsville, on the Australian mainland, crippling a chunk of MacArthur’s air force prior to the Port Moresby landing. Inoue did not expect that Takagi would encounter American carriers until Takagi moved northward after the Townsville raid to cover the Port Moresby landings.28 At least that was the plan.

On May 2, the small Royal Australian Air Force detachment at Tulagi learned of the advance of the Japanese landing force and escaped to the New Hebrides after demolishing some facilities. The following day, the Japanese force, landing unopposed, was observed by SWPA reconnaissance planes. MacArthur passed the report to Admiral Fletcher, who, unbeknownst to Inoue, was cruising on the Yorktown in the Coral Sea south of the Solomons. Fletcher ordered Yorktown north and launched a raid against Tulagi that returned with high boasts but did little actual damage to the invasion force. The result, however, was to warn Takagi of the presence of an American carrier and expedite his approach with the Shokaku and Zuikaku around the eastern end of the Solomons and into the Coral Sea by midday on May 5.

General Brett’s bombers, flying out of Townsville and Port Moresby, caught glimpses of the Port Moresby invasion force slowly making for Jomard Passage, between the New Guinea mainland and the Louisiade Archipelago. Repeated air attacks over the course of three days ended with little damage to the Japanese ships, but inexplicably, Brett, or perhaps it was MacArthur, did not relay any of these sightings or actions to Fletcher—just one consequence of a less-than-unified command.29

Elements of what would come to be called MacArthur’s Navy were, however, on the scene. Admiral Leary had sent the bulk of his SWPA naval forces—two Australian and one American cruiser and three destroyers—to assist Fletcher, but on the morning of May 7, Fletcher detached them westward to protect Port Moresby from any force steaming out of Jomard Passage. Successive waves of Japanese medium and heavy bombers found the ships and pressed attacks dangerously close, at one point straddling Rear Admiral John G. Crace’s Australian flagship with a spread of bombs. Barely had these planes departed when three more medium bombers dropped bombs from twenty-five thousand feet on one of the destroyers.

“It was subsequently discovered,” Crace later reported, “that these aircraft were U.S. Army B-26 from Townsville.” Photographs taken as the bombs were released left little doubt that they had attacked their own ships. “Fortunately,” Crace concluded, “their bombing, in comparison with that of the Japanese formation a few moments earlier, was disgraceful.”30

Records showed only eight Allied B-17s then engaged anywhere in the vicinity. General Brett flatly denied that his planes—B-26s, B-25s, or otherwise—had attacked Crace’s command and rejected an offer from Leary to work on improving the air forces’ recognition of naval vessels. MacArthur seems to have stayed above this fray, but he held conferences with both Brett and Leary the next day, and the affair likely did not improve his regard for either man.31

Meanwhile, both Fletcher and Takagi launched search planes to find each other’s carriers. They found targets, but not the ones they were looking for. The first strike from the Japanese carriers mistook the destroyer Sims and oiler Neosho, idling by themselves waiting for a refueling rendezvous, for a carrier and cruiser and sank them after a furious onslaught. The Americans fell victim to a similar problem of misidentification and launched full complements of aircraft from Yorktown and Lexington against reports of “two carriers and four heavy cruisers” 175 miles to the northwest. The nervous pilot had meant to encode “two heavy cruisers and two destroyers,” but dive-bombers from the Lexington stumbled upon the light carrier Shoho in the covering force, sinking it to one pilot’s cry of “Scratch one flattop.”32

Finally, on the morning of May 8, planes from the two principal carriers on each side found their targets, leaving the Lexington and the Shokaku the most heavily damaged of the four and proving that carrier aircraft could fight major encounters without surface ships ever coming into direct contact with each other. The Americans made headway to save the Lexington, but gasoline vapors from ruptured fuel lines ignited and started a series of chain explosions. Sailors lined the flight deck in a calm evacuation, and Fletcher had the grim duty of ordering a destroyer to sink the flaming wreck to avoid any chance of its salvage by the Japanese.

Having already been instructed by Admiral Inoue to abandon the raid against Townsville, Takagi turned northward with the Zuikaku to follow the wounded Shokaku. The loss of the Shoho prompted a similar recall as both the Port Moresby invasion fleet and the remnants of its covering force turned around and sailed back to Rabaul. Tactically, the Americans had sustained heavier losses, but strategically, they had dealt the first major setback to Japan’s unchecked post–Pearl Harbor romp and managed to blunt the Japanese drive to cut Australia’s lifeline. King would never forgive Fletcher for the loss of the Lexington, but five months after Pearl Harbor, Fletcher had taken on a slightly superior force and, at worst, emerged with a draw. At best, he had saved Australia.33

But the Battle of the Coral Sea was not quite over. There was to be a secondary fight of press releases between MacArthur and the American navy. During the course of the running naval battle, the Australian Advisory War Council had taken the unprecedented step of granting MacArthur just the sort of supreme censorship over SWPA operations that MacArthur had just told Marshall was “utterly impossible” to enforce. News was to come only from Diller’s SWPA communiqués. The first two dispatches of May 8 reported ten enemy ships sunk and five badly damaged in the Coral Sea action, with MacArthur’s bombers playing a leading role and without any mention of specific American losses, including the Lexington. It was an egocentric way for MacArthur to show he was “in the know,” but it had just the opposite effect. Such shabby reporting sparked criticism from the Australians and outrage from the American navy.34

The Lexington had barely settled beneath the warm waters of the Coral Sea when Marshall told MacArthur that King and Nimitz were quite disturbed by his “premature release of information” concerning forces under Nimitz’s command because it imposed “definite risks upon participating forces and jeopardize[d] the successful continuation of fleet task force operations.” King decreed that thenceforth, news of Nimitz’s forces would be “released through the Navy Department only.”35

Predictably, MacArthur took affront and immediately dispatched a characteristically lengthy reply: “Absolutely no information has been released from my headquarters with reference to action taking place in the northeastern sector of this area except the official communiqués. By no stretch of possible imagination do they contain anything of value to the enemy nor anything not fully known to him.” The forces so engaged, MacArthur noted, included a large part of his air force, a major portion of the Australian navy, and his heavily Australian ground forces at Port Moresby and elsewhere. The battle involved “the very fate of the Australian people and continent,” MacArthur maintained, “and it is manifestly absurd that some technicality of administrative process should attempt to force them to await the pleasure of the United States Navy Department for news of action.”36

In response to this tirade, Marshall took his usual calm approach—he did not reply. It is difficult to imagine that Marshall would have brooked such insolence from another subordinate. Far from being cowed by MacArthur, Marshall was simply following the party line. The president had decided that MacArthur’s worth as an asset outweighed his liabilities, and Marshall would do his best to follow suit. That did not mean, of course, that Roosevelt did not share Marshall’s frequent exasperation.

“As you have seen by the press,” Roosevelt wrote Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King on May 18, “Curtin and MacArthur are obtaining most of the publicity. The fact remains, however, that the naval operations were conducted solely through the Hawaii command!”37

Far from shying away from Nimitz, MacArthur complimented the admiral on the manner in which his forces were handled and announced he was eager to cooperate. “Call upon me freely,” MacArthur wrote. “You can count upon my most complete and active cooperation.”38 Meanwhile, MacArthur regaled his staff with stories of how his planes had discovered the Japanese invasion fleet. “He told it all in the most wonderfully theatrical fashion,” Brigadier General Robert H. Van Volkenburgh, his antiaircraft chief, remembered years later. “I enjoyed every second of it.”39