CHAPTER TWELVE

“Take Buna, Bob…”

Unbeknownst to MacArthur’s intelligence, elements of General Horii’s South Seas Detachment had begun to move south from Buna within hours of their initial landing, early on July 22. Lieutenant Colonel Hatsuo Tsukamoto, the commander of an infantry battalion, received orders “to push on night and day to the line of the mountain range.” By that evening, Tsukamoto’s nine hundred men were already seven miles inland and making for the crossing of the Kumusi River at Wairopi, which means “wire rope bridge” in Tok Pisin, a language of New Guinea. A company of the Australian Thirty-Ninth Infantry Battalion and troops from the Papuan Infantry Battalion, the only Allied forces on the Kokoda Trail north of the Owen Stanley crest, managed to destroy the bridge before falling back to Kokoda and its primitive airfield.

Tsukamoto’s troops crossed the Kumusi in makeshift boats, pressed on to Kokoda, and momentarily routed the Australians from the airstrip. The Australians counterattacked around midday on July 28, recaptured the field, and desperately hoped to be reinforced by a full infantry company to be flown in by four transports capable of landing on the tiny strip. However, in the confusion, it never became clear to commanders in Port Moresby that Kokoda had been recaptured, and the reinforcements never took off. The next day, Tsukamoto’s troops again drove the Australians out of Kokoda.1

This frenzied fighting, albeit in less than battalion-strength numbers, did not particularly alarm Willoughby. He believed their main objective was to secure airfields on the grassy plains at Dobodura, near Buna, menacing Port Moresby via an air duel across the mountains but not advancing directly against it. According to the US Army official history, Willoughby “conceded that the Japanese might go as far as the Gap [near the crest of the Owen Stanley Range] in order to establish a forward outpost there, but held it extremely unlikely that they would go further in view of the fantastically difficult terrain beyond.”2

One of those not wanting to take any chances on that score was Admiral King. With Japanese troops in control of Kokoda, King pointedly asked Marshall for MacArthur’s plans “to deny further advance to the Japanese, pending the execution of Task Two.”3 King was concerned because if MacArthur’s task 2 charge—occupying New Guinea and the western Solomon Islands—faltered, the US Navy’s task 1 mission against Tulagi and Guadalcanal might be outflanked or overrun.

King was particularly annoyed with MacArthur at that moment because MacArthur had met with South Pacific Area commander Ghormley in Melbourne on July 8, and together they recommended delaying the Tulagi and Guadalcanal landings. King insisted these had to occur by August 1 in order to halt Japanese airfield construction, but MacArthur and Ghormley feared they did not have enough strength in their areas, particularly land-based air coverage, to guarantee success. They advised that the operation be deferred pending the further deployment of forces.4

For King, this was the first strike against Ghormley. As for MacArthur, King snidely reminded Marshall that, only weeks before, MacArthur had been eager to take a couple of carriers and charge into Rabaul. Now, said King, when “confronted with the concrete aspects of the task, he… feels he not only cannot undertake this extended operation [Rabaul] but not even the Tulagi operation.”5 King’s only concession was to grant Ghormley a one-week reprieve.

Thus on August 7, 1942, the first of sixteen thousand US Marines went ashore to confront moderate resistance on Tulagi and nearby Gavutu and initial light resistance on Guadalcanal. They captured the uncompleted airfield there—soon renamed Henderson Field—the next day. But then the bottom fell out. The Japanese counterattacked, and all hell broke loose.

MacArthur and Ghormley, while accused by King of getting “the slows,” had been right in their lengthy communiqué, warning, in part, that “a partial attack leaving Rabaul in the hands of the enemy… would expose the initial attacking elements to the danger of destruction by overwhelming force.”6

Put simply, land-based air from Rabaul and surrounding bases could cover Japanese convoys steaming through the Solomons to pummel Guadalcanal. The First Marine Division and the US Navy now faced that overwhelming force. There was little MacArthur could do—short of limited air operations and a few ships—to interdict the flow of men and supplies from Rabaul, because he had his hands full north of Port Moresby.

The day after the initial American landings at Guadalcanal, Australian troops yet again recaptured the Kokoda airfield. This success, too, was short-lived, and they were soon forced to yield to a concentrated Japanese force three times their number. These Japanese troops secured Kokoda and probed toward the Gap, a rocky five-mile-wide saddle 7,500 feet in elevation at the crest of the Owen Stanley Range. The Gap was around twenty miles south of Kokoda on terrain so broken that there was no space to pitch a tent and barely room enough for one man to pass another. From the Gap southward, the steep jungle slopes—almost perpetually wet from receiving between two hundred and three hundred inches of rain a year—became a slippery slide as the Kokoda Trail dropped six thousand feet to the foothills north of Port Moresby. As late as August 18, Willoughby still thought a strong Japanese overland movement beyond the Gap was unlikely given the terrain.7

Unbeknownst to MacArthur and Willoughby, however, Horii had planned a pincer movement on Port Moresby, sending the Kawaguchi Detachment to capture tiny Samarai, an island on the extreme southeastern tip of New Guinea, and then attack Port Moresby from the sea while the full complement of the South Seas Detachment moved against it overland from Kokoda. But the sudden need to reinforce Guadalcanal caused the Japanese to divert a large portion of the Kawaguchi Detachment there, while only one battalion continued toward Samarai.

But MacArthur had his own surprise. Somehow, amid the far-ranging geography and frequently cloud-shrouded coastal mountains, the Japanese had failed to detect the Allied airfield under construction at Milne Bay. George Kenney was in command of Allied air operations by then and just as determined as MacArthur to reinforce it. One landing strip was operational for P-40s and twin-engine Hudson bombers, and two other runways were under construction. To bolster defenses, MacArthur ordered one brigade of the Australian Seventh Infantry Division to Milne Bay and the other two brigades to Port Moresby.8

Finally discovering this Allied threat, the Japanese rerouted the Samarai-bound battalion and additional troops to Rabi, near Milne Bay. P-40s strafed one fleet of landing craft and marooned them on nearby Goodenough Island while Kenney sent all available B-25s, B-26s, and nine B-17s in search of the main invasion force and its escorting cruisers and destroyers. Turbulent rainsqualls and a heavy overcast shielded most of the convoy, forcing it to land on a densely covered alcove flanked by the sea and steep mountains several miles farther east of Rabi than planned.9

With much of MacArthur’s navy on loan to Ghormley for the Guadalcanal operations, the Japanese held clear naval superiority in Milne Bay; however, when weather permitted, Kenney’s air forces played a major role as opposing ground troops engaged in seesaw battles for control of the airfields. The Japanese were clearly surprised by the ferocity of the defenses. While Allied troops faced similar deprivations, Commander Minoru Yano reported that his troops were “hungry, riddled with tropical fevers, suffering from trench foot and jungle rot, and with many wounded in their midst.” His superiors ordered an evacuation on the night of September 5—the first repulse of an amphibious force that Japan had suffered up to that point in the Pacific.10

Following fighting there, the airstrips at Milne Bay were rushed to completion and went on to play a critical role in offensives on the northern side of the Owen Stanley Range. In a September 10 communiqué, MacArthur reported that the Japanese thrust against Milne Bay had been anticipated and the position occupied and strengthened with great care so that “the enemy fell into the trap with disastrous results to him.”11 In truth, the victory was more of a testament to a dogged Allied defense and MacArthur’s determination not to retreat from New Guinea than it was to a shrewdly planned entrapment.

Meanwhile, despite the stout defense at Milne Bay, the Allies faced a juggernaut rolling along the Kokoda Trail. General Horii took personal command in the field and ordered a full-scale assault south from Kokoda on August 26. The Australians fought bitterly during their retreat, but were swept from the Gap and forced back to Ioribaiwa Ridge, dangerously close to Port Moresby.

In part swayed by Willoughby’s continuing reassurances, MacArthur remained convinced that Japanese strength on the trail was light and that there was little prospect of their advancing on Port Moresby. He could not understand the repeated Australian withdrawals. In fact, Horii had pushed the maximum number of troops he could reasonably supply over the harsh ground along the trail, and it was not until one of the Australian brigades hurriedly disembarked at Port Moresby on September 9 and the other joined it that the Allies achieved some measure of parity.12

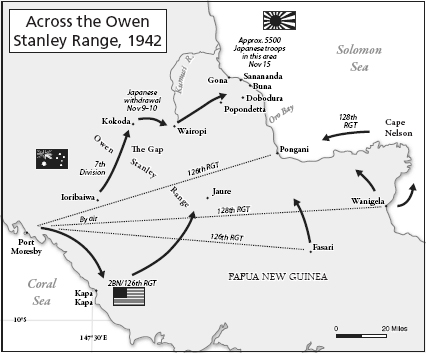

Finally realizing the magnitude of the Japanese attack, MacArthur looked at his maps and proposed what he called “a wide turning movement,” typical of his strategy. He proposed to deploy an American regimental command team, almost four thousand men, around Horii’s left flank and into his rear, crossing the Owen Stanley crest east of the Gap and threatening or cutting Horii’s tenuous supply line near Wairopi. The plan on paper looked shrewd, but MacArthur, Sutherland, and much of his general headquarters staff had still not come to appreciate the extreme topography of New Guinea. Lines on a map did not readily translate into the reality of the almost impenetrable jungle. MacArthur gave the assignment to Major General Robert L. Eichelberger, newly arrived from the states to command the US Army’s I Corps.13

Born in 1886, Eichelberger was six years MacArthur’s junior. Among his 1909 West Point classmates were George S. Patton, Jacob L. Devers, Edwin F. Harding, and Horace H. Fuller, the latter two by then subordinate to him as division commanders in Australia. Like MacArthur’s, Eichelberger’s personality could be both engaging and intimidating, with mood swings and his own share of paranoia. No one, however, ever questioned his personal courage. He had his own Distinguished Service Cross for bravery with the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia during World War I and knew George Kenney from the time when they were both assigned to Fort Leavenworth in the mid-1920s. Eichelberger, as post adjutant—for reasons not entirely clear—once tore up charges against Kenney for violating the strict ban on alcohol at the post.

Eichelberger was also well acquainted with Douglas MacArthur from his duty as secretary of the War Department’s General Staff when MacArthur was chief of staff. Readily acknowledged as an innovator and rising talent, he became superintendent of West Point in 1940 and quickly cut back on activities associated with an outdated gentleman’s army—training on horseback among them.

Instead Eichelberger promoted modernized combat training and optional flight instruction, the latter allowing cadets to receive pilots’ licenses. In March of 1942, Marshall determined that Eichelberger was needed in the field, and he took command of the Seventy-Seventh Infantry Division. When MacArthur asked Marshall to send him a corps commander to preside over the two American divisions then in Australia, Marshall dispatched Eichelberger to the Pacific.14

Eichelberger was none too pleased by the assignment. He was on the short list for a role in Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa scheduled for November, and knew MacArthur well enough to recognize that he would be difficult to serve under. Marshall had scrapped his initial choice, Major General Robert C. Richardson Jr., after concluding, “Richardson’s intense feelings regarding service under Australian command made his assignment appear unwise.”15 Eichelberger’s corps headquarters was staffed and ready, had been trained in amphibious operations, and, whatever the potential for friction, Eichelberger had previously worked for MacArthur. He got the orders.

Eichelberger arrived in Australia on August 25. Technically, his immediate superior was Australian general Thomas Blamey, the commander of Allied ground forces in the Southwest Pacific Area. Eichelberger, however, understood MacArthur well enough to know who his real boss was, particularly after MacArthur and his headquarters staff made it a point to instruct him “never to become closely involved with the Australians.”16

Eichelberger’s I Corps contained the Thirty-Second Infantry Division, the core of which were National Guard units from Wisconsin and Michigan, under the command of Edwin Harding, and the Forty-First Infantry Division, largely National Guard units from the Pacific Northwest, under the command of Horace Fuller, both major generals. Their divisions had been called to active duty in the fall of 1940 and—by prewar standards—had undergone rigorous training. The bulk of the Forty-First arrived in Australia in April, followed by its remaining units and the Thirty-Second Division in May.

When Eichelberger inspected both divisions upon arriving in Australia, however, he found the Thirty-Second’s training “barely satisfactory” and particularly deficient in jungle warfare, even though it had spent much of the preceding year on maneuvers in the swamps of Louisiana. Nonetheless, on Harding’s recommendation that the 126th Infantry was the best trained and best led of the Thirty-Second’s three regiments, Eichelberger chose it to make MacArthur’s flanking attack against the Kokoda Trail. The 128th Infantry would follow to bolster the Australians outside Port Moresby.17

To facilitate the mission, Eichelberger found a willing and creative ally in feisty George Kenney. Within days of his arrival in Australia, Kenney had had a predictable run-in with Sutherland over air operations. Sutherland sent Kenney detailed orders for an air strike, prescribing takeoff times, bomb sizes, numbers and types of aircraft, and all manner of other things best left to the air force. Kenney stormed into Sutherland’s office and told him that when he was given a mission he expected that the best way to execute it would be left to his professional judgment. When Sutherland protested, Kenney stood firm. Fine, he said: “Let’s go in the next room, see General MacArthur, and get this thing straight. I want to find out who is supposed to run this Air Force.”18 Sutherland backed down, and Kenney’s stock with MacArthur—who was listening from his adjoining office—went up another notch.

The movement of anything—men, equipment, munitions, and supplies—between Australia and New Guinea was problematic because of the extended distances—1,300 miles between Brisbane and Port Moresby—and a shortage of ships. Kenney’s initial inspection visit to New Guinea had convinced him that time was of the essence in holding Port Moresby, and he urged MacArthur to let him fly a full regiment to New Guinea by air and save the two weeks required to load and transport it by ship.

Sutherland and most of MacArthur’s staff were skeptical, but MacArthur asked how many men Kenney might lose that way. Kenney replied that his planes had been ferrying freight to Port Moresby without losing a pound, and he figured he could do the same with troops. MacArthur agreed to a test, and on the morning of September 15, Eichelberger and Kenney arranged to move one company from the 126th Infantry—230 men with small arms and packs—from Amberley Field, near Brisbane, to Port Moresby in a collection of Douglas DC-3s and Lockheed Lodestars.

The flight went off without a hitch—the first American infantry to arrive in New Guinea—and Kenney asked to move the remainder of the regiment. Told that it was already embarking by ship, Kenney said, “All right, give me the next regiment to go.” With Sutherland looking askance, MacArthur agreed and ordered Kenney to get together with Eichelberger and make the arrangements. This move, too, of the 128th Regiment, went off without incident, becoming the largest deployment of ground troops by air up to that point and giving Eichelberger and Kenney ideas for future operations.19

At the same time these transport operations were under way, Kenney’s combat aircraft from Port Moresby and Milne Bay pounded Japanese positions along the length of the Kokoda Trail. A-20 twin-engine light bombers, modified to carry eight forward machine guns and drop parachute fragmentation bombs, which Kenney himself had had a hand in developing, made low-level attacks against Japanese supply trains, ammo dumps, and landing barges as well as the airstrip at Buna and the river crossing at Wairopi. These operations dramatically disrupted the Japanese supply chain, and by mid-September there was not a grain of rice to issue to troops in the front lines at Ioribaiwa.

At that point the Japanese faced a reality check. While MacArthur believed the Joint Chiefs continually subordinated his efforts to Allied priorities elsewhere, particularly the battle raging on Guadalcanal, Horii may well have felt the same way about his superiors. On September 18, under pressure from air attacks and out of rice, Horii received orders to abandon his forward position at Ioribaiwa and effect a fighting withdrawal back across the Owen Stanley Range, past Kokoda and Wairopi, to a stronghold at the Buna beachhead.

Japanese strategy then called for the bulk of its army and naval forces in the Rabaul region to destroy the US Marines on Guadalcanal as their first priority. When this was accomplished, the force would turn its attention to New Guinea, moving back across the mountains against Port Moresby and seizing Milne Bay with much greater numbers than those just repulsed. Consequently, Horii began his withdrawal from Ioribaiwa, and by September 28, the Australian Twenty-Fifth Infantry Brigade had moved from defense to offense, retaken Ioribaiwa, and was proceeding northward on the Kokoda Trail.20

MacArthur grumbled about the effectiveness of the Australian troops and found similar fault with Harding’s Thirty-Second Division, but Kenney’s air force became a newfound source of pride. Kenney’s can-do attitude rapidly filtered down to his pilots and crews. He cleaned out what he considered dead wood, particularly among the colonels and brigadier generals serving in Australia, and made Brigadier General Ennis C. Whitehead his deputy and point man in New Guinea and Brigadier General Kenneth N. Walker his bomber command chief at Townsville. Both men were newcomers. “I had known them both for over twenty years,” Kenney recalled. “They had brains, leadership, loyalty, and liked to work. If Brett had had them about three months earlier his luck might have been a lot better.”21

That may well have been true, but it was Kenney’s own personality, no doubt helped by the success of his airmen, that quickly earned MacArthur’s trust and confidence. MacArthur interacted the most with Dick Sutherland and discussed military strategy and history at length with Charles Willoughby, but gruff George Kenney quickly made it into MacArthur’s inner circle. Kenney became one of the very few officers permitted to saunter from his offices on the fifth floor of the AMP building to MacArthur’s office on the eighth floor or from his quarters to MacArthur’s suite in Lennons Hotel, uninvited and unannounced, and receive a warm welcome.22

In a military hierarchy where a commanding general with MacArthur’s aloof and distancing personality might be said to not have any friends, Kenney came as close as anyone to filling that role. MacArthur would not have described Kenney as a friend, but he was glowing in his praise—always reciprocated by Kenney—and certainly considered him a close confidant.

A little more than a month after Kenney assumed command of his air forces, MacArthur told Kenney, “The improvement in its performance has been marked and is directly attributable to your splendid and effective leadership.”23 Ten days later, MacArthur boasted to Marshall: “General Kenney with splendid efficiency has vitalized the air force and with the energetic support of his two fine field commanders, Whitehead and Walker, is making remarkable progress. From unsatisfactory, the air force has already progressed to very good and will soon be excellent.”24

By the end of September, Kenney had made an airpower believer out of MacArthur, and MacArthur recommended Kenney for promotion to lieutenant general, citing his “superior qualities of leadership and professional ability.” In the same letter, MacArthur also recommended Robert Eichelberger for promotion to lieutenant general, but Eichelberger was momentarily to take a backseat in operations in New Guinea.25

Delighted in Kenney and satisfied for the moment just to have Eichelberger on his team, MacArthur scrutinized his naval commander, Herbert F. Leary. A classmate of Nimitz’s at Annapolis, Leary had spent most of his sea duty in cruisers. Handicapped by limited combat ships—Southwest Pacific Area naval forces then floated only five cruisers, eight destroyers, twenty submarines, and seven auxiliary vessels—Leary had nonetheless supported the Coral Sea fight and the initial Guadalcanal campaign until MacArthur begged Marshall to order the ships returned to his area to augment the Milne Bay defenses.

Leary proved reluctant, however, to dispatch his cruisers and destroyers into what he viewed as dangerous, reef-strewn waters. Tentativeness was never a good thing with MacArthur, and it didn’t help Leary’s standing with him that regardless of the SWPA unity of command—Leary was supposed to report to and receive his orders from MacArthur on operational matters—Admiral King routinely communicated directly with Leary, and Leary responded directly to King, on all naval matters. MacArthur pushed for a change, and Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender took over from Leary on September 11 as commander of the US Navy’s Southwest Pacific Force as well as Allied Naval Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area. To MacArthur’s frustration, Carpender would prove equally timid in the waters between Milne Bay and Buna.26

Meanwhile, the crisis continued on Guadalcanal. King and Nimitz shared MacArthur’s view that subordinate commanders should be fighters. Alarmed that there had been neither determination nor daring in Ghormley’s brief command of the South Pacific Area, Nimitz flew four thousand miles from Hawaii to Ghormley’s headquarters at Nouméa, New Caledonia, in late September to confer. With MacArthur’s Brisbane headquarters only nine hundred miles farther west, Nimitz suggested through King and Marshall that MacArthur attend the conference “as a means to reach a common understanding of each other[’]s problems and future plans.”27

MacArthur was on record, only days before, as once again asking what assistance he could expect from the US Pacific Fleet should the Japanese launch a seaborne attack on New Guinea.28 Such a conference would have been highly beneficial in answering these operational questions as well as in building a personal rapport. Marshall had already encouraged MacArthur to communicate directly with Ghormley and/or Nimitz in critical situations as long as MacArthur kept him informed of any action taken.29 This was an exception to the formal protocol—MacArthur reporting to Marshall and Nimitz reporting to King, with communications and decisions passed via the Joint Chiefs.

MacArthur, however, claimed that it was inadvisable for him to leave his command and declined to travel less than a quarter of the distance that Nimitz had traveled. MacArthur went on to tell Marshall that he and Ghormley had already conferred—albeit back in early July—“so extensively that we understand thoroughly our mutual situations.” Not only did this raise the question of why MacArthur had just queried the navy’s intentions, it also kept MacArthur firmly in Ghormley’s corner.

Instead of going to Nouméa, MacArthur invited Nimitz to extend his trip to Brisbane so that he “could see at first hand the problems of this area.” Stressing the importance of his personal presence in Brisbane, and overlooking Nimitz’s far more sweeping geographic responsibilities, MacArthur said he doubted that he could leave his command at any time and concluded, “The emergencies of command make it impossible for me to attend a conference outside of this area.”30

Marshall did not try to persuade MacArthur otherwise, but he instructed him that it was very important that a member of his staff attend. Sutherland and Kenney went in MacArthur’s place, making their first of many trips together to represent MacArthur’s interests. While Sutherland, as MacArthur’s chief of staff, was clearly the senior officer, Kenney gave observers some insight into his own ego and interaction with Sutherland when he later wrote that he flew to the conference “taking Sutherland along.”31

What Marshall knew but could not yet say was that King and Nimitz had strong doubts about Ghormley’s suitability for the South Pacific command. In the nearly two months since the invasion, Ghormley had never visited Guadalcanal. More disconcerting was the fact that twice during the conference at Ghormley’s headquarters a staff officer delivered high-priority radio dispatches to Ghormley only to have him mutter, “My God, what are we going to do about this?”

Rather than visiting MacArthur, Nimitz decided to see the Guadalcanal situation for himself, and after the conference—which included planning air operations, conducted by Kenney, against Rabaul and Guadalcanal-bound convoys—he flew there in a B-17 to confer with the commander of the embattled First Marine Division, Major General Alexander Vandegrift. After a good deal of candid discussion, both men resolved that there would be no retreat from Guadalcanal, and Nimitz returned to Pearl Harbor convinced he had to relieve Ghormley.32

Had the Guadalcanal campaign failed and ended in an American withdrawal, the Japanese might well have directed far greater force in a much more timely manner against New Guinea. Viewed in that light, it is not too great a leap to say that what saved Port Moresby and kept MacArthur from a defeat in New Guinea may well have been the First Marine Division slugging it out on Guadalcanal. With the Japanese firmly committed there, MacArthur had the opportunity to turn the tide on New Guinea and move forward toward Buna.

With the Japanese retreating over the Kokoda Trail, MacArthur issued offensive plans on October 1 to recapture Buna. These were based in part on a memo Eichelberger had prepared at MacArthur’s request two days before. Eichelberger pleaded that he and his I Corps headquarters staff be deployed to New Guinea to direct Harding’s Thirty-Second Division staff and gain combat experience with it. Otherwise, Eichelberger asserted, there would be nothing for him and his staff to do but cool their heels in Australia and watch the training of the Forty-First Division.33 MacArthur refused the request—apparently with substantial input from Sutherland.

Consequently, Eichelberger and his corps staff remained in Australia while MacArthur expanded his proposed right hook into the Japanese rear at Wairopi. He decided on an even wider sweep to the east in two columns. This would bring three lines of attack to bear on the Japanese strongholds around Buna: the Australian Seventh Division, via the Kokoda Trail; the 126th Infantry, from Kapa Kapa, on the southern coast, over the Owen Stanley Range to Jaure; and the 128th Infantry, via air and sea along the north coast. Obligingly, the Japanese remained committed to falling back to the coastal strongholds after appropriate delaying actions.

As this three-pronged offensive was beginning, MacArthur chose to make his first visit to New Guinea. Since his arrival in Australia some six months before, he had remained largely remote and isolated in his Melbourne and Brisbane headquarters, so much so that “MacArthur sightings” were the talk of the citizens and servicemen alike who happened to catch a glimpse of him. At one level this added to his mystique—the grim-faced warrior beneath his crushed cap ducking into a car or striding through a doorway—but it did little to build esprit de corps among his frontline troops, be they American or Australian.

Save for his early trip to Canberra to address Parliament and a sixty-mile excursion out of Melbourne to inspect the training camp of the Forty-First Infantry Division, MacArthur did not travel out of Melbourne until his move to Brisbane in July. Once there, he hunkered down in similar fashion at Lennons Hotel and his headquarters in the AMP building and insisted that visitors come to him. By Kenney’s account, it was he—Kenney—who suggested that the time had come for him to see New Guinea, and MacArthur readily agreed.34

On October 2, MacArthur and Kenney flew in a B-17 from Brisbane to Townsville, then continued to Port Moresby. MacArthur spent the next day touring the area with Blamey. According to Kenney, MacArthur “made quite a hit with the Aussies.” He fired up Brigadier John E. Lloyd, the commander charged with driving the Japanese back up the Kokoda Trail, with characteristic MacArthur flair: “Lloyd,” intoned MacArthur, “by some act of God, your brigade has been chosen for this job. The eyes of the western world are upon you. I have every confidence in you and your men. Good luck and don’t stop.”35

MacArthur also inspected recently arrived American infantry and found them “fresh and full of pep.” MacArthur took a dose of that pep with him when he returned to Brisbane early the next day. Indeed, his first trip to New Guinea seems to have wiped away some of the regret he may have felt over his failure to visit Bataan more often. Certainly its success spurred him to undertake more frontline excursions.

Until his next visit to New Guinea, Allied troops doggedly pressed his three lines of attack. On the Kokoda Trail, the Australians pushed the Japanese back through the Gap and, after a bitter fight at Eora Creek, recaptured Kokoda and its airfield for the final time on November 2. The orderly withdrawal General Horii had hoped to execute took the form of a rout. The main Japanese force fled across the Kumusi River at Wairopi on the night of November 12–13. The Australians wiped out the rear guard, took possession of the crossing, and erected a temporary bridge. Horii and his chief of staff drowned farther downstream while trying to cross the swift and swollen river on a raft.

The center prong, from Kapa Kapa to Jaure, quickly became a grueling quagmire. Companies of the 126th Infantry forced their way across the Owen Stanley divide at a pass two thousand feet higher than the Gap. The terrain on both sides was rougher and more precipitous than the tough Kokoda Trail and said to be so narrow that “even a jack rabbit couldn’t leave it.” The troops marched in single file, and there was usually no place on either side of the trail for a bivouac. Still, by October 28, the Second Battalion of the 126th Infantry, weakened by dysentery and assorted jungle maladies, was marshaled at Jaure and hacking its way toward Buna.

The likelihood of adequate reinforcements and supplies following the battalion, however, was low. Thanks to information provided by a local missionary, it was discovered that suitable landing sites were located north of the range, and transports airlifted the remainder of the 126th directly from Port Moresby to points north on the coast. These hastily constructed dirt strips—created mostly by burning off tall grasses and small trees—put to rest any thoughts of attempting a similar overland route. The men of the Second Battalion thus remained the only American troops to cross the Owen Stanley Range on foot.

For the eastern prong, MacArthur was severely handicapped by a lack of landing craft and small vessels to move west from Milne Bay. Kenney solved this problem by flying a battalion of Australian infantry and American engineer and antiaircraft troops from Milne Bay to Wanigela, on the eastern side of the Cape Nelson peninsula. After they secured and expanded an airfield, Kenney’s Fifth Air Force flew the bulk of the 128th Infantry directly to Wanigela from Port Moresby—avoiding the cross-mountain slog. Meanwhile, another Australian battalion from Milne Bay landed on Goodenough Island to roust the Japanese troops marooned there since the Battle of Milne Bay and preclude the Japanese from using the island for flanking operations.36

While these three lines of attack developed, MacArthur kept a wary eye on Guadalcanal, fearful that a Japanese victory there would bring increased forces against him on New Guinea. By mid-November, Nimitz’s new South Pacific commander replacing Ghormley, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr.—with whom MacArthur was about to have considerable interaction—was far from declaring victory, but he seemed to have gained the upper hand, thanks in part to some fierce naval battles. Buoyed by this news, MacArthur was confident that the ring around Buna and Gona, to the west, which the Australians and Americans had formed by mid-November, could be squeezed tight in a matter of days.

Sensing that victory was close at hand, MacArthur returned to Port Moresby on November 6 along with Kenney. Preceded several days earlier by Sutherland and a small staff, they moved into Government House, the rambling one-story former residence of the Australian territorial governor, which perched on a small rise overlooking the harbor. Shortly afterward, MacArthur’s headquarters issued a press release saying that it could “now be revealed” that MacArthur, Kenney, and Allied land forces commander Thomas Blamey were “personally conducting the campaign from the field in Papua.”37

Assuming he would be back in Brisbane long before Christmas, MacArthur issued his plan of attack on the Gona-Buna stronghold on November 14. It tasked the Australian Seventh Division with taking Gona and Sanananda, west of the point where the Girua River emptied into the sea. East of the river, two regiments of the American Thirty-Second Division were charged with taking the village of Buna (hereinafter referred to as Buna Village) and what was called Buna Mission, the latter not a religious enclave but rather a government station.

An impenetrable swamp of murky waist-deep water, bottomless mud, and a thick tangle of jungle growth split the Buna front in two. Humidity averaged 85 percent, daily temperatures approached one hundred degrees Fahrenheit, and a long list of tropical maladies inflicted debilitating illness. Beyond these natural obstacles and infirmities, Japanese defenders had had ample time to turn even the smallest spots of relatively dry ground into well-concealed foxholes. These guarded every conceivable route around the swamps and were backed up by a string of heavily fortified bunkers.38

In the face of these defenses, Blamey suggested to MacArthur a rather daring leapfrog by air. He proposed landing a brigade from Milne Bay two hundred miles to the north of Buna at Nadzab, near Lae, to frustrate Japanese supply lines. MacArthur judged it too big of a gamble, fearing that Japanese control of the waters between Buna and Lae—Admiral Carpender still refused to commit his vessels to the area—might lead to reinforcements at Lae that could isolate the brigade. When Blamey later wanted to move the Milne Bay brigade to bulk up his forces opposite Gona, MacArthur again demurred because he was not convinced that Milne Bay was immune from another attack.39

At that point, the major difference between the Australian and American troops was that many of the Australians were battle-tested from combat along the Kokoda Trail. The Americans had as yet faced only the rigors of climate and terrain. These were, of course, significant, and Eichelberger later reported that even before the Thirty-Second Division had its baptism by fire in mid-November, its troops “were riddled with malaria, dengue fever, tropical dysentery, and were covered with jungle ulcers.”40

A final burden to be faced by the Allied troops was that Willoughby’s intelligence estimated that the Japanese had only between fifteen hundred and two thousand troops in the Gona-Buna area. Actual numbers were three to four times this, and not only were they heavily dug in, they were also well supplied with ample stocks of food and ammunition. The Allies, on the other hand, were dependent on sketchy supply lines from Kokoda by land and Milne Bay by sea and the increasingly reliable drone of Kenney’s transports, either dropping supplies from the air or landing on jungle airstrips. According to Eichelberger, “Both Australian and American ground forces would have perished without ‘George Kenney’s Air.’”41

As MacArthur’s Allied forces attacked the Gona-Buna area starting in mid-November, they met harsh reality on all fronts. On the evening of November 22, despite a week of little progress, MacArthur ordered Harding to launch another all-out attack regardless of the cost. Meeting tough resistance, Harding halted the attack and pulled back. To MacArthur and those in Port Moresby, this appeared premature, and it particularly did not square with MacArthur’s ideas of “going over the top” from World War I. With continuing pressure from MacArthur, Harding ordered another assault on November 30. The Japanese defenders also repulsed this effort with heavy casualties. Harding claimed, with considerable justification, that a major part of the problem was that he lacked tanks and heavy artillery to counter the stout defenses.42

Once again, Blamey proposed a creative approach and asked to make an amphibious landing seaward of the line of defenses. This time MacArthur heartily concurred, but Carpender remained adamant about not committing his ships off Buna. The plan was further frustrated by a lack of landing craft in New Guinea. In desperation, MacArthur appealed to Halsey for a loan of naval resources to conduct the operation.

The two had not yet met, and while Halsey appeared on the cover of Time magazine that week as the savior of Guadalcanal, he was far from confident. “Until Jap air in New Britain and Northern Solomons has been reduced,” Halsey responded to MacArthur, “risk of valuable naval units in Middle and Western reaches [of the] Solomon Sea can only be justified by major enemy seaborne movement against South coast New Guinea or Australia itself.”43

This was not a matter of some sinister Washington conspiracy, the likes of which MacArthur frequently denounced, and MacArthur was well justified in complaining to Marshall about the response. However grudgingly, MacArthur had supported the Guadalcanal operations with Allied ships until launching his own Milne Bay operation, and Kenney’s bombers had pounded Rabaul as much as possible to interdict the flow of aircraft, shipping, and troops toward Guadalcanal. The effectiveness of these air operations varied with the telling—whether the reports came from MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area or Halsey’s South Pacific Area headquarters—but MacArthur had seriously tried to help.

Now MacArthur faced the possibility of a defeat brought on as much by disease as by enemy troops if he did not take Buna quickly. He heatedly told Marshall that despite his support for the South Pacific during its crises, at a moment when he faced similar pressure and appealed for naval assistance, he had “not only been refused but occasion has been taken to enunciate the principles of cooperation from my standpoint alone.”44

MacArthur was further vexed by reports from Blamey and other Australian commanders, as well as from Sutherland’s firsthand impressions, that the American leadership in the Thirty-Second Division, from Harding on down, was unaggressive and that its soldiers lacked the will to fight, disease-ridden though they were. Consequently, in a final measure of desperation, MacArthur turned to the man he and Sutherland had theretofore kept from the action, I Corps commander Bob Eichelberger.

In mid-November, Eichelberger had finally made it to Port Moresby, but his reception by Sutherland had been less than warm. Eichelberger planned to stay a few days and observe the Thirty-Second Division in combat, but before he could get north of the Owen Stanley Range, Sutherland ordered him back to Australia on a courier plane, telling him that his job was to train troops. In Eichelberger’s words, despite being the second-ranking American army officer in the Pacific, he “was being given a monumental brush-off.”45

Two weeks later, Sutherland was forced by MacArthur to do an about-face and cable Chamberlin, MacArthur’s operations chief in Brisbane: “Advise Eichelberger immediately to be prepared to proceed [to Port Moresby]… to take command of the American troops in the Buna Area. If such an order issues it will come Monday [the following day] and should be executed immediately.”46

The order came around midnight on November 29, and Eichelberger, his chief of staff, Brigadier General Clovis E. Byers, and others of his staff arrived in Port Moresby on December 1 and made the trip to Government House to get their marching orders from MacArthur. The general paced back and forth from one end of the sweeping veranda to the other in his characteristic pontifical manner. Sutherland, just returned from the Dobodura airfield, near Buna, sat at a desk looking grim-faced and perturbed. Only Kenney, animated as usual, greeted Eichelberger and Byers with any measure of warmth.

According to Eichelberger, there were no preliminaries. “Bob,” MacArthur said, “I’m putting you in command at Buna. Relieve Harding. I’m sending you in, Bob, and I want you to remove all officers who won’t fight. Relieve regimental and battalion commanders; if necessary, put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies—anyone who will fight.”

He went on to complain about reports of “American soldiers throwing away their weapons and running from the enemy.” Then MacArthur stopped his pacing and looked Eichelberger squarely in the face. “Bob,” he said pointedly, “I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive.” Pausing a moment and not looking at Byers, he added, “And that goes for your chief of staff too.”47

This exchange, as reported by Eichelberger in his account of the Pacific war, became one of the most quoted of MacArthur’s career. Two of his most worshipful biographers, Courtney Whitney and Clark Lee, do not mention it, nor did MacArthur in his own memoirs. Stalwart friend Kenney chose to ignore the “don’t come back alive” part and remember MacArthur’s orders to Eichelberger as “an inspiring set of instructions” from a real leader who knew how to inspire people. The remark has usually been cited as an example of MacArthur’s tough, even callous, leadership, although at least one biographer termed it “the absolute nadir of his generalship.”48

But whatever was said, it was really just vintage MacArthur hyperbole—the sort MacArthur had employed against himself when he boasted before Châtillon in World War I that his name would head the casualty lists if the place were not taken. In context, it was a typical MacArthur pep talk, and Eichelberger seems to have taken it that way.

At breakfast the following morning, as Eichelberger prepared to fly north, MacArthur showed his other side. He and Eichelberger laughed over stories about their days together in Washington when MacArthur was chief of staff. Kenney remembered MacArthur saying, “Now, Bob, I have no illusions about your personal courage, but remember that you are no use to me—dead.”

Eichelberger remembered that MacArthur put his arm around him afterward and promised him the two things that MacArthur always assumed motivated other men as much as they motivated him: a Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor and the highest award in MacArthur’s discretion to bestow, and the ultimate prize, regardless of the anonymity under which he required commanders in his theater to function—a promise to “release your name for newspaper publication.”49

But just as he had with conditions on Bataan, MacArthur seemed removed from the field conditions and couldn’t understand the delays. MacArthur had not visited—nor would he ever visit—the battlefields around Buna, which were only a short flight away from Port Moresby. Eichelberger and his staff landed at Dobodura around 10:00 a.m. on December 1, in Eichelberger’s words, “forty minutes from Moresby—but when the stink of the swamp hit our nostrils, we knew that we, like the troops of the 32nd Division, were prisoners of geography.”50

Eichelberger toured the front and came to the conclusion that while the deck had been stacked against Harding on many counts, inspired leadership was lacking. Harding’s relief and that of two regimental commanders were necessary to reinvigorate the division. Harding went quietly, but not without a long letter to MacArthur. “I do not feel I failed you or the men I commanded,” Harding told him, adding, “We took chances on a shoestring supply line and maintained it by expedients that aren’t in any textbook.” He disputed Eichelberger’s claim that his men were beaten and told MacArthur: “To the criticism that the men of the division did not fight, my answer is the casualty lists.”51

Eichelberger himself became appalled as casualties continued to mount, but he pressed forward on all fronts. On December 8, the Australians captured Gona, and the Thirty-Second Division renewed its drive on Buna Village. The night before it finally fell, a week later, Eichelberger wrote Sutherland: “The conditions since the heavy rains are indescribable. For hours I walked through swamps where every step was an effort.” Reporting regularly to Sutherland and MacArthur, Eichelberger once noted, “[I] cannot get this off tonight as it is dark now and the stenographer is getting eaten up by mosquitoes. More tomorrow.”52

Meanwhile, that same day, MacArthur continued to send his own brand of encouragement Eichelberger’s way: “However admirable individual acts of courage may be; however important administrative functions may seem; however splendid and electrical your presence has proven, remember that your mission is to take Buna. All other things are merely subsidiary to this.” Hasten your preparations, MacArthur told him, and “strike.”53

Even the capture of Buna Village had not satisfied MacArthur. Buna Mission remained a Japanese stronghold, and Sanananda, between Gona and Buna Village, promised even tougher fighting. MacArthur had long planned to be celebrating Christmas Day with Jean and Arthur in Brisbane, but he found himself still in Port Moresby and far from certain about ultimate victory. He wrote Eichelberger and thanked him for the gift of a captured Japanese sword, but rather than returning the general’s Christmas greetings, he launched into a critique of Eichelberger’s campaign to date. It was being done “with much too little concentration of force on your front,” MacArthur told him. He wanted an attack in such force as would overwhelm the Japanese lines, reminiscent of the trench warfare of the last war.

Casualties, which MacArthur would later boast were low, were not on his mind at that moment. “It will be an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth—and a casualty on your side for a casualty on his,” MacArthur wrote. Then, in words that sounded particularly calculating, he added, “Your battle casualties to date compared with your total strength are slight so that you have a big margin to work with.”54

As a final prod, MacArthur sent Sutherland to the Buna area between Christmas and New Year’s with full authority to get Eichelberger moving on MacArthur’s timetable or relieve him. According to Paul Rogers, whose desk was in a corner of the sweeping veranda at Government House, MacArthur told Sutherland, “If Eichelberger won’t move, you are to relieve him and to take command yourself. I don’t want to see you back here alive until Buna is taken.”55