CHAPTER FOURTEEN

“Skipping” the Bismarck Sea

During the six months since the Japanese beat MacArthur to the punch and seized the Buna beachhead, MacArthur’s forces had fought a tenacious and costly campaign, first retreating and then advancing across Papua. Strategically, however, they were right where they would have been had they gotten to Buna before the Japanese. This weighed particularly heavily on Admiral King as the Joint Chiefs awaited MacArthur’s plans for executing tasks 2 and 3 of their July 2, 1942, directive. MacArthur’s initial response did nothing to alleviate King’s apprehensions.

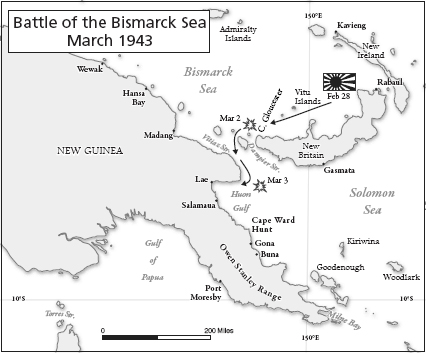

MacArthur merely dusted off the memo he and Admiral Ghormley had crafted before Guadalcanal and reiterated a five-step plan to capture (1) Lae and Salamaua, on New Guinea; (2) Gasmata and other toeholds on the opposite end of New Britain from Rabaul; (3) Lorengau, on Manus Island, in the Admiralty Islands, and Buka, at the western end of the Solomons; (4) Kavieng, on the northern tip of New Ireland; and (5) Rabaul itself.1 MacArthur believed these phases were necessary, making possible the orderly advance of airfields to provide land-based air protection for naval movements and to bring bombers with fighter escorts over the ultimate objective, Rabaul. However, MacArthur asserted that he was not yet prepared to undertake any of these phases because he lacked sufficient ground and air forces.2

King retorted that MacArthur’s reply was more of a “concept” than a “plan” and told Marshall, “It does not give us any concrete idea of what he intends to do or how he expects to do it or what the command setup is to be.” Given the expanse of the Japanese-occupied Solomons between American-held Guadalcanal and MacArthur’s target of Buka, King was especially concerned that MacArthur did not appear to have given much thought to Halsey’s operations. King recommended that, unless MacArthur provided specific plans soon, Halsey should develop his own operations for the Solomons and the Joint Chiefs should withhold MacArthur’s authority over the South Pacific Area.3

Complicating the planning for these operations was the fact that, at King’s urging, navy planners were studying a westward advance across the central Pacific. Initially, this thrust would be against the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, the former a British protectorate captured by the Japanese within a week of Pearl Harbor and the latter a Japanese mandate since World War I. Striking directly westward across the central Pacific was the manifestation of the time-honored Plan Orange, and King saw this axis as the most direct route to Japan. His goal of stopping any Japanese threat to the West-Coast-to-Australia lifeline had been met at Guadalcanal, and he had little enthusiasm for conducting similar island-by-island fights across the expanse of the southwestern Pacific.

The ultimate planning challenge for the army and navy thenceforward would be to make operations on these two separate axes—west across the central Pacific under Nimitz, largely a navy and marines operation, and northwest from the Solomons and New Guinea under MacArthur, primarily an army action—complement, rather than complicate, one another.

In order to flesh out the details of his strategic plan, MacArthur suggested that he send representatives to meet with army and navy planners in Washington. Marshall concurred, and, although King himself was on the West Coast conferring with Nimitz, the Joint Chiefs directed MacArthur, Nimitz, and Halsey to dispatch officers from their theater staffs to meet and map out future operations in the Pacific. Before the conference could convene, however, MacArthur and his team had to contend with a counterattack against New Guinea.4

In early February of 1943, senior Japanese commanders at Rabaul held a strategy session of their own to discuss options on the northern coast of New Guinea after the loss of Buna. Having also abandoned Guadalcanal, Imperial General Headquarters called for an “active defense” in the Solomons while pursuing an “aggressive offensive” in New Guinea, just as MacArthur had long feared. With the loss of Lieutenant General Tomitaro Horii, the responsibility fell to General Hitoshi Imamura and the recently created Eighth Area Army. Headquartered at Rabaul, the Eighth Area Army comprised Lieutenant General Hatazo Adachi’s Eighteenth Army in New Guinea and Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army spread throughout the Solomons.5

Adachi was a hard-drinking, stone-faced veteran from campaigns in China who exemplified the Japanese warrior values of patience, perseverance, and endurance. He also wrote tanka—a structured form of Japanese poetry—on the side. Imamura directed Adachi to fortify Lae and prevent MacArthur from advancing westward along the New Guinea coast. Well aware that Kenney’s air forces were taking a toll on shipping in the Huon Gulf between Buna and Lae, Adachi faced a dilemma. He could land reinforcements at Madang—140 air miles to the west of Lae and beyond the reach of most Allied air—and attempt to march to Lae via a roadless tangle of swamps, or he could transport reinforcements directly to Lae by ship and confront the full fury of Allied bombers and fighters.

The gritty Kanga Force, a small detachment of Australian troops, had been holding Wau and the Bulolo Valley since May of 1942 and receiving supplies and reinforcements mostly by air. When this force repulsed a Japanese offensive aimed at Wau and pushed toward Salamaua, only twenty-five miles from Lae, Imamura and Adachi decided to reinforce Lae directly. The odds were not good.

Eighth Area Army staff war-gamed a ten-ship convoy inbound to Lae and estimated losses as high as 40 percent of the ships and 50 percent of their aerial escorts. Nevertheless, the urgent need to reverse the setback at Wau left no alternative, and on February 14, Imamura ordered Adachi to lead his Fifty-First Division to Lae by sea. Imamura and Adachi didn’t know that the odds against them were worse than they thought.6

MacArthur’s secret weapon was Ultra, the broad name for the special intelligence obtained by monitoring and decoding enemy radio traffic. Distinct from the US Navy’s efforts to crack the Imperial Japanese Navy codes that gave warning of the Coral Sea encounter and led to victory at Midway, MacArthur’s Ultra unit, Central Bureau, had its origins in a prewar group of army code breakers and analysts in Manila who evacuated from Corregidor shortly before it fell. Based first in Melbourne and then in Brisbane, Central Bureau slowly developed the capability to decipher Japanese military communications.

Directed by Brigadier General Spencer B. Akin, one of the Bataan Gang, Central Bureau worked closely with the navy’s Ultra unit in Australia, the core staff of which had also evacuated from Corregidor. As a theater commander, MacArthur received both army and navy Ultra. These intercepts and their analyses varied in quantity and quality over the years, but by 1943, traffic analysis permitted MacArthur’s subordinates to ascertain and plot detailed unit deployments, convoy schedules, and major aircraft movements with considerable certainty.

Like nearly everything surrounding MacArthur, the relationship between the Ultra operators of the War Department and US Navy and MacArthur’s Central Bureau code breakers was characterized by a degree of friction. But Edward J. Drea, the leading authority on MacArthur’s use of Ultra, asserts that “overemphasizing this aspect diminishes an appreciation of the remarkable accomplishment of MacArthur’s people, of the degree of cooperation, and of the exchange of Ultra intelligence among the three parties.”7

The results were significant and consequential. Kenney utilized Ultra intercepts in planning air attacks, and they proved key to his aircrafts’ ability to find Japanese ships. The key to sinking them was a tactic that Kenney and his deputy Ennis Whitehead perfected. Both men had experienced significant exposure during their careers to Hap Arnold’s most cherished technique: high-level daylight precision bombing. But bomb drops from fifteen thousand or twenty thousand feet had not proved very effective in the southwestern Pacific, particularly against moving targets at sea. Having already worked with the legendary Paul “Pappy” Gunn to modify B-25s for strafing attacks by installing .50-caliber machine guns in the noses, Kenney—always the innovative engineer—ordered the relatively agile medium bombers to make low-level attacks and skip their bombs to the target.

Skip bombing was similar in concept to the favorite pastime of skipping flat stones across a pond. Twin-engine B-25s and A-20s came in at full throttle, flying 250 miles per hour at three hundred feet or less above the sea. Mere yards from the target, sticks of between two and four bombs equipped with four- or five-second delay fuses were dropped. With the proper angle of release, these skipped across the waves and either struck the side of the target and detonated or submerged and exploded below the waterline. Meanwhile, the bombers’ machine guns and those of the escort aircraft raked the decks of the target ship and thereby suppressed its antiaircraft fire.

As General Adachi and most of the Fifty-First Division—some seven thousand men on eight transports escorted by eight destroyers—sailed out of Rabaul around midnight on February 28 and steamed west through the Bismarck Sea, MacArthur and Kenney fully expected a major Japanese effort to reinforce New Guinea. Kenney’s overflights of Rabaul harbor in the preceding days had disclosed a large concentration of shipping reminiscent of the July 1942 buildup just before the landings at Buna. The question was, where would Adachi land—Lae, Madang, or even Wewak, farther west? Based on Ultra traffic analysis, US Navy cryptanalysts in the Melbourne unit handed MacArthur the answer and predicted that Adachi’s convoy would land at Lae sometime in early March.8

This information, welcome though it was, posed the usual quandary in the use of Ultra intelligence: it had to be made to appear that the enemy movement had been stumbled upon in the execution of routine operations. Too specific a targeting of forces would be a tipoff to the Japanese that their codes or other communications had been compromised. Even with Ultra information in hand, actual intercept operations could still be chancy.

A reconnaissance aircraft spotted the Lae-bound convoy, designated Operation 81 by the Japanese, off the northern coast of New Britain on March 1 but lost it in the evening darkness. Shortly after dawn, contact was reestablished off Cape Gloucester, and by midmorning, long-range B-17s and B-24s from Port Moresby made their usual high-altitude attack, sinking one transport and damaging two other ships, an especially good score for high-altitude bombing. Hoping this might be the worst of it, the convoy churned on at a plodding seven knots and during the night passed from the Bismarck Sea into the Solomon Sea via Vitiaz Strait, the westernmost of the two passages between the Huon Peninsula and New Britain and its last chance to make a dash toward Madang.

As its ships moved through Huon Gulf in clear daylight, Operation 81 had some protective air cover, but these planes flew at seven thousand feet in anticipation of another high-altitude attack. That’s when Kenney’s medium bombers roared in just above sea level and skipped their bombs against the targets. “We went in so low we could have caught fish with our props,” one pilot reported.

As the bombers skipped their payloads and fired their machine guns, P-38 and P-40 fighters, along with Australian twin-engine Bristol Beaufighters, strafed the decks of the transports as troops rushed topside to abandon ship when the bombs found their marks. The convoy was turned into chaos, and one after the other, the transports slowly began to sink. When the escorting destroyers moved to rescue survivors, they received a similar dose of bombs and machine-gun fire. It was a grisly business as bombers and fighters returned again and again throughout the day on March 3. Finally, PT boats from Buna moved in to finish off any crippled transports still afloat.

Over the running battle, eight Japanese transports and four destroyers sank. Only a handful of Allied planes and pilots were lost. Although records vary, of 6,900 troops in the convoy, an estimated three thousand died. Only one thousand reached their destination: the remaining survivors were rescued and returned to Rabaul on destroyers. General Adachi himself had to be pulled from the water. This loss of the Fifty-First Division as a fighting force marked the end of large-scale convoys to Lae and halted Japan’s efforts at an “aggressive offensive” in New Guinea. Adachi turned his efforts to road construction from Wewak through Madang to Lae and reluctantly assumed an “active defense.”9

By all accounts, the three-day action, which MacArthur immediately called the Battle of the Bismarck Sea—even though it was primarily fought in the waters of Huon Gulf, in the Solomon Sea—was a smashing Allied victory. MacArthur, Kenney, and Whitehead—not to mention their pilots and crews—might well have basked in unquestioned glory. But Douglas MacArthur had repeatedly shown that he was not often satisfied with the raw facts, no matter how exceptional and complimentary they might be to him. He had to reach for superlatives, even if that meant embellishing the truth.

In a March 4, 1943, press communiqué, MacArthur grandly announced, “The battle of the Bismarck Sea is now decided. We have achieved a victory of such completeness as to assume the proportions of a major disaster to the enemy. His entire force was practically destroyed.” This was absolutely true. But MacArthur went on to describe the Japanese naval component as “22 vessels, comprising 12 transports and 10 warships—cruisers or destroyers,” and claimed, “All are sunk or sinking.” Additionally, he reported fifty-five Japanese aircraft destroyed and a staggering fifteen thousand troops “killed almost to a man.”10

This tally of enemy ship and aircraft losses probably came from individual battle reports, which frequently duplicated sightings and sinkings as one air unit after another reported in. Even MacArthur’s public relations chief, LeGrande “Pick” Diller, cautioned MacArthur to wait for a final accounting. MacArthur, however, simply responded, “I trust George Kenney.” As Diller later remarked, “It wasn’t up to me to verify the communiqués.”11

Two days later, with Kenney’s concurrence, MacArthur issued another communiqué affirming the ship and personnel losses but raising to 102 the number of aircraft shot down. This was essentially the accounting submitted to Washington by both MacArthur and Kenney in their official reports.12

Such high enemy losses, particularly when they were considerably more than Ultra estimates of vessels en route in the first place, were met with skepticism in Washington. Yet in the euphoria of victory, especially one so sweeping, this might have been the end of the matter. MacArthur, however, could not refrain from trumpeting the Bismarck Sea victory in a way guaranteed to incur the supreme wrath of the US Navy.

Around a month after the victory, secretary of the navy Frank Knox responded to Australia’s latest expression of anxiety over fears of a Japanese invasion. MacArthur had frequently orchestrated such Aussie angst in order to apply political pressure to increase aid to his theater. And these expressions had become routine and continued despite Allied successes in New Guinea and the Solomons. In this particular case, Knox issued a reassuring statement noting that an invasion of Australia would require “a tremendous sea force” and there was “no indication of a concentration pointing to that.”13

There was no reason for MacArthur to weigh in on the matter, but, still basking in the Bismarck Sea victory, he couldn’t resist. “The Allied naval forces can be counted upon to play their own magnificent part,” he began patronizingly, “but the battle of the western Pacific will be won or lost by the proper application of the air-ground team.” Despite his having just proved the opposite in the seas off Lae, MacArthur nonetheless maintained that “the Japanese, barring our submarine activities, which are not to be discounted, have complete control of the sea lanes in the western Pacific and of the outer approaches toward Australia.”

But Australians should not fear. According to MacArthur, control of those sea lanes no longer depended primarily upon naval power but rather on airpower operating from land bases held by ground forces. Apparently forgetting the final days in Manila, when he had boasted that his thirty-five B-17s made the Philippines a fortress, MacArthur concluded, “The first line of Australian defense is our bomber line.”

But then MacArthur twisted the knife. “A primary threat to Australia,” he lectured, “does not therefore require a great initial local concentration of naval striking power. It requires rather a sufficient concentration of land-based aviation.”14 If MacArthur had made his point any stronger, he might as well have said that there was not much reason for the US Navy to be in the South Pacific. It was little wonder that General Marshall was told by his planning chief to expect a visit from Admiral King, who reportedly was more disgruntled than usual.15

Truth be told, MacArthur had a point—at least as far as the ever-increasing role of Kenney’s air force is concerned—but this was hardly a very politic way to put it with the US Navy. Having knocked down the hornets’ nest, MacArthur had to deal with the consequences.

Whether the navy’s pique over this incident played any role in what happened next is uncertain, but Hap Arnold’s staff in Washington decided to take a second look at MacArthur’s and Kenney’s claims of sinking twenty-two ships, downing 102 planes, and killing fifteen thousand soldiers in the Bismarck Sea. Considering it was wartime, they conducted a rather exhaustive review that included captured Japanese documents and Ultra intercepts. The inquiry concluded that there were never more than sixteen ships in the Japanese convoy and that, except for one rescue destroyer dispatched from Kavieng, no other ships joined it, as Kenney had claimed in trying to explain the discrepancy. Of this number, investigators confirmed that all eight transports and four destroyers were sunk, with a loss of around three thousand men.16

The results of this investigation were relayed to MacArthur and Kenney in August of 1943 with a request to file an amended action report. This was relatively routine and frequently occurred following the analysis of all after-action reports. But this time, there was no response from either MacArthur or Kenney. Three weeks later, Marshall wrote to MacArthur noting that his biennial report to the secretary of war was due. In the interest of incorporating “only uncontested factual material,” Marshall said, “if the facts are as stated in [the] Air Force letter, I [should] be advised immediately and a corrected communiqué be issued.”17

Wrong though he almost certainly was, MacArthur would not simply submit a revised report. Instead he fired off an angry response, which, coming from any other subordinate’s pen, would likely have had him relieved. His original communiqué was factual as issued, MacArthur claimed, and subsequent data gathered confirmed every essential fact. Then he got personal, as only he could. “Operations reports and communiqués issued in this area,” MacArthur wrote, “are meticulously based upon official reports of operating commanders concerned, and I am prepared to defend both of them officially or publicly.”

If Marshall was not going to include his report as originally issued, MacArthur demanded that any report “challenging the integrity of my operations reports of which the Chief of Staff is taking cognizance, be referred to me officially in order that I may take appropriate steps, including action against those responsible if circumstances warrant.”18

Given far more important ongoing matters, Marshall chose not to pick up MacArthur’s gauntlet. He printed MacArthur’s version in his biennial report to the secretary of war and was inclined to let the matter drop. Kenney, however, contested the findings of the inquiry in a point-by-point refutation to Arnold, who assured him that had he not been in Europe and ignorant of the air force investigation, he would have put a stop to it.19

This should have been the end of the matter, but MacArthur could not stop fighting. Two years later, in an interview held the day after accepting the final Japanese surrender, MacArthur brought up the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, calling it “the decisive aerial engagement in his theater of war” as he reflected on the course of the Pacific campaigns. “Some people have doubted the figures in that battle,” he then noted, “but we have the names of every ship sunk.”20

A few days after this interview, Kenney’s headquarters created a committee to reexamine all records in the hope, according to one of the investigators, “that Japanese sources would bear out the Kenney-MacArthur position.” When this didn’t happen, the new report was never sent to Washington, and, according to one account, “MacArthur’s headquarters ordered that the report be destroyed.” Far from naming twenty-two ships, it had concluded that “the number of Japanese personnel lost was 2890, not 15,000, the number of vessels sunk twelve, not twenty-two,” thus affirming the findings of the 1943 inquiry.21

Nonetheless, MacArthur and Kenney never wavered in their stated version. In the years that followed, they stood by it in interviews and their respective memoirs. Somewhat tellingly, two of MacArthur’s most ardent supporters did not. Writing in MacArthur: His Rendezvous with History, Courtney Whitney gave the convoy total as sixteen ships and seven thousand troops, but instead of giving losses, he merely noted that there had been “some slighting comments” made about MacArthur’s characterization of the battle as “a major disaster to the enemy.” Intelligence chief Charles Willoughby, writing in MacArthur 1941–1951, correctly excused the higher numbers as early estimates that “included duplication of eyewitness accounts that was inevitable in haze and rain” and reported that Japanese records “definitely established that Kenney’s raids got a minimum of eight transports and four of the eight destroyers.”22

Much of this story is decidedly petty. But it must be recounted because it strikes to the core of the dark side of Douglas MacArthur. Kenney, writing in The MacArthur I Know, maintained that “the actual number [of losses] is unimportant and the whole controversy is ridiculous.” The important fact, he continued, “remains that the Jap attempt to reinforce and resupply their key position at Lae resulted in complete failure and disaster.”23 Kenney was correct all around. But why couldn’t MacArthur see that?

Samuel Eliot Morison, chronicler of the navy’s official history of the war, was generous in his appraisal, even if MacArthur grumbled to Kenney that “he thought the Navy was trying to belittle the whole thing because they weren’t in on it.” It was understandable that MacArthur would base his official communiqué on early aviator reports, Morison wrote, “but such mistakes are common in war and inevitable in air war. It would be more credible to acknowledge the truth, which is glorious enough for anyone, than to persist in the error.”24

D. Clayton James, MacArthur’s most balanced and definitive biographer, agreed. “It is amazing,” James wrote, “that MacArthur would have accepted their challenge to make the affair a cause célèbre, particularly since he could have quietly excused his erroneous statements on the grounds of incomplete battle reports.” But as was evidenced by his intense and inflexible reactions in similar situations throughout his career—the Veracruz Medal of Honor recommendation and later censorship exchanges with Marshall among them—whenever Douglas MacArthur perceived an affront to his honor, pride, or public image, no matter how incontrovertible the evidence against him, he did not retreat from his position.25

All of which gets back to Ultra. When Ultra intercepts confirmed the sinking of the lower total of ships within days of the battle, MacArthur and Kenney might have amended their reports then and there, particularly as these same intercepts were read in Washington and contributed to the skepticism over MacArthur’s and Kenney’s claims. But as Edward Drea observes, “Both commanders ignored ULTRA confirmations of results not to their liking. In other words, they exploited ULTRA when it supported their operational preference, but this did not necessarily mean that they regarded this intelligence as definitive, particularly when the ULTRA version of events conflicted with their own perceptions.”26

For all his exaggerations and defiant intransigence, the Battle of the Bismarck Sea was unquestionably a defining moment for Douglas MacArthur, both in terms of his embrace of airpower as well as his professional and personal regard for George Kenney. MacArthur had already seen airpower applied to the jungles along the Kokoda Trail and had seen it used as a tactical weapon to move full regiments of men and supplies quickly and stealthily, but after the Bismarck Sea battle he saw it as an increasingly strategic weapon. “We never could have moved out of Australia,” he told reporters after the war, “if General Kenney hadn’t taken the air away from the Jap.”27

Allied land-based air was proving itself in New Guinea and making a believer out of MacArthur. According to Eddie Rickenbacker’s account of his visit with MacArthur a few months before the Bismarck Sea fight, MacArthur told him, “You know, Eddie, I probably did the American Air Force more harm than any man living when I was chief of staff by refusing to believe in the future of the airplane as a weapon of war. I am now doing everything I can to make amends for that great mistake.”28 MacArthur was learning. The question was, would the MacArthur of fact be able to catch the MacArthur of legend?

Fresh from the Bismarck Sea triumph, Kenney joined Sutherland and flew to Washington to represent MacArthur in what came to be called the Pacific Military Conference. They were indeed an odd couple, the proverbial Mutt and Jeff: tall, spit-and-polish Sutherland, who greeted everyone with a curt, commanding nod, and short, rumpled Kenney, who took his down-home, “How’s it going, boys” attitude with him, whether on the flight line or in the staff room.

For both men, the conference marked a transition in their careers. Sutherland stepped out of MacArthur’s shadow and into his own as a strategic planner. Having seen to theater operations as MacArthur’s chief of staff, he increasingly focused on intertheater relationships and took on a quasi-ambassadorial role as a liaison between MacArthur’s headquarters and the Joint Chiefs.

Kenney was hailed as the architect of the Bismarck Sea battle—no matter what the number of enemy losses might be—and he emerged as the champion of using the full spectrum of airpower. Hap Arnold and his British counterparts might promote heavy bombing to wear down German industry, but Kenney had proved airpower’s value at all levels, from fighter support for ground troops to medium and heavy bomber strikes to transport operations for troop and supply movements.

Both men were well aware, of course, that they owed their positions and increasing prominence to Douglas MacArthur. In their own ways, they were both fiercely loyal to him, Sutherland as the by-the-book martinet, Kenney as the irreverent buccaneer, as MacArthur called him. In both instances, it was obvious that the more MacArthur believed in someone, the more power that person could assume and the more he could get away with. Unlike Sutherland, who eventually became a little too quick to decide what MacArthur wanted done, Kenney seems never to have taken advantage of the relationship and remained genuinely loyal to MacArthur, warts and all.

The Pacific Military Conference, convened in Washington on March 12, 1943, was a who’s who of the supporting cast in the Pacific. In addition to Sutherland and Kenney, MacArthur also sent Brigadier General Stephen J. Chamberlin, his operations (G-3) officer. Halsey’s South Pacific Area headquarters was represented by Lieutenant General Millard F. Harmon, commanding the army and air forces under Halsey; Major General Nathan F. Twining, commanding the Thirteenth Air Force; Captain Miles R. Browning, Halsey’s mercurial chief of staff; and Brigadier General DeWitt Peck, the chief Marine Corps planner on Halsey’s staff. From the Central Pacific Area, Nimitz dispatched Lieutenant General Delos C. Emmons, commanding the Hawaiian Department; Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Nimitz’s chief of staff; and Captain Forrest P. Sherman, of Nimitz’s staff. Admiral King and General McNarney, the latter representing Marshall, welcomed the group but left Rear Admiral Charles M. “Savvy” Cooke Jr. and Major General Albert Wedemeyer to orchestrate the discussion.29

The first order of business was for Sutherland to present MacArthur’s detailed strategy for carrying out tasks 2 and 3 of the July 2, 1942, directive. Code-named Operation Elkton, the plan fleshed out the five phases MacArthur had proposed and called for a two-pronged advance along the northeastern coast of New Guinea and northwest through the Solomons, culminating in the capture of Rabaul. The first step on the western prong would be to capture Lae to advance Kenney’s line of operational airfields. Halsey had already made a small step in the Solomons beyond Guadalcanal by seizing the Russell Islands en route to New Georgia and Bougainville.30

A major bone of contention between the Pacific representatives and the Washington planners became the number of troops and aircraft available. MacArthur proposed—to which Halsey agreed—a total of twenty-three divisions for the Southwest Pacific Area and the South Pacific Area. But the planners foresaw only twenty-seven divisions in the entire Pacific by the end of September, 1943. That included US Army, US Marines, and Australian divisions, six of the latter being mostly militia units assigned to Australian defense.

If two of the remaining twenty-one divisions were assigned to the Central Pacific Area for operations against the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, this left nineteen divisions to be divided between the Southwest Pacific and South Pacific Areas. MacArthur was projected to get eleven divisions and Halsey eight divisions, in each case two divisions—or around twenty-five thousand troops—shy of what they judged Elkton required.

An even greater shortage of aircraft existed, with fifteen air groups in the two areas and forty-five requested. Even if there had not been an overriding concern about shipments of aircraft to the European theater, the planners judged a shortage of shipping problematic in deliveries to the Pacific. On the other hand, as for manpower, at the end of February in 1943, despite the Pacific being judged a secondary front, the US Army alone had 374,000 men in the Pacific, exclusive of Alaska, compared to 298,000 in the Mediterranean and 107,000 in the British Isles.31

Nonetheless, the scramble for resources led to the usual jockeying for position between the army and the navy as well as among the three Pacific areas. As Kenney put it, “Representatives of both the South and Central Pacific Areas were watching the situation very closely to see that, if anything was passed out, they would get their share of it before MacArthur’s crowd from the Southwest Pacific grabbed it off.”32

Wedemeyer finally reminded the group that the Combined Chiefs of Staff had committed to capture Rabaul. The Pacific commanders either had to find a way to execute the operation with the resources available or request a change in directive from the chiefs. Sutherland relented and agreed that the next step—moving on Lae and through the Solomons—might be accomplished with the resources available. Even then, however, Kenney warned that the operations could not occur until additional aircraft were received in September. With similar reservations, Halsey’s South Pacific representatives agreed to proceed through the Solomons, leaving specific operations against Rabaul to be decided later.33

The Joint Chiefs directed the principal representatives to put that plan in writing. Without committing their respective commanders, Sutherland, Spruance, and Browning proposed that the available forces execute task 2, including Madang and the southeast portion of Bougainville Island, and extend the line forward to include Cape Gloucester and the islands called Kiriwina and Woodlark.34

The addition of Kiriwina and Woodlark was a major change to MacArthur’s original Elkton plan, but it made sense, as these would provide Kenney with forward air bases both to support operations in the northern Solomons with medium bombers and to serve as a stepping stone for operational interchanges of air units between the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific Areas. (The latter was evidence that, reports of intertheater friction aside, there was considerable cooperation between MacArthur’s and Halsey’s commands.) The revised Elkton plan still called for mostly a mile-by-mile, island-by-island advance, but an important change for Halsey was the decision to bypass New Georgia, in the midst of the Solomons, and capture Bougainville directly, thanks in part to the anticipated air cover from Woodlark.35

The end result of this sixteen-day conference was that the Joint Chiefs issued a directive on March 28 canceling their charge of July 2 of the prior year and outlining specific offensive operations in the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific Areas for the remainder of 1943. As Marshall and King had already tentatively agreed, the Joint Chiefs confirmed MacArthur’s supreme command of his Southwest Pacific Area with no change in boundaries. They put Halsey under MacArthur’s command for matters involving general strategy to facilitate intertheater cooperation and left the United States Fleet, other than the units the Joint Chiefs assigned to task forces in those areas, under Nimitz’s control as CINCPAC.

Together, MacArthur and Halsey were charged with establishing airfields on Kiriwina and Woodlark, seizing the Huon Peninsula from Lae west to Madang, occupying Cape Gloucester, on the western end of New Britain, and moving through the Solomons as far as the southern portion of Bougainville. MacArthur was ordered to submit specific plans to the Joint Chiefs for the composition of task forces and the sequence and timing of major operations.36

No matter how MacArthur chose to sequence the actions, it was clear that there would be a pause in offensive operations throughout the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific Areas. King argued that during this self-imposed lull, the bulk of Halsey’s South Pacific naval strength should be used to move against the Gilbert and Marshall Islands. But many of the same reasons for delay also existed there: a shortage of men, planes, and ships and the need to maintain the initiative and continue an aggressive advance beyond those points once they were captured. Instead, Admiral Spruance advocated moving part of the fleet back to Hawaiian waters as a safety measure—Ultra was thin during that period because of a change in codes, and there was some uncertainty as to Japanese whereabouts—and he recommended using other elements of the fleet to oust the Japanese from two tiny islands in the Aleutians in Alaska.

As part of the Midway operations the year before, Japanese troops had taken possession of the islands of Attu and Kiska, at the far western end of the Aleutians. The American response was to build the Alaska Highway, safeguard the Northwest Staging Route, via which airplanes were ferried to Russia, and pour men and materiel into a series of airfields and army bases. Now, with the rest of their Pacific operations idling, the Joint Chiefs agreed to the Alaskan operation. In May, a bloody battle ensued for Attu after the Allies skipped over Kiska, which planners thought to be more heavily defended. Later, the largest battle fleet ever to assemble in Alaskan waters, including three battleships and five cruisers, pounded Kiska before an invasion found that the Japanese had abandoned the island.

For MacArthur and Halsey, this meant that during the summer of 1943, the Alaskan theater and various on again, off again Japanese attempts to reinforce the Aleutians diverted Japanese naval forces to the northern Pacific and left the Solomons relatively quiet. Perhaps most significant to MacArthur, out of this northern campaign would come a new naval commander much to his liking.

And for all of Ernie King’s impatience during 1943, as well as MacArthur’s and Halsey’s cries for more resources, America’s industrial might was reaching a fever pitch in the summer of 1943. The United States had gone from having a total of eight aircraft carriers, including the seaplane tender Langley, on December 7, 1941, to having seven new Essex-class aircraft carriers and nine smaller Independence-class light aircraft carriers commissioned in 1943 alone. More were on the slipways, readying to be launched and commissioned during 1944. They would speed the drive westward across the Pacific, and no matter what his thoughts about the United States Navy were, Douglas MacArthur would be a prime beneficiary of their power. As Sutherland, Kenney, and Chamberlin returned to Brisbane and got to work on the revised Elkton plans, MacArthur decided it was time to meet with a man reputed to be almost as tough and opinionated as he was. It was time for him to meet Bill Halsey.