CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Bypassing Rabaul

The World War II strategy of island-hopping—isolating and bypassing enemy strong points—had many fathers. The Japanese, consciously or not, employed a version of it when they left MacArthur and some eighty thousand troops on Corregidor and Bataan. They rushed past to attack the East Indies and reach their goal of an unfettered supply of natural resources. When the North Pacific Force directed its assault against Japanese-occupied Attu, in the Aleutians, in May of 1943 after bypassing what was thought to be more heavily defended Kiska, they made the first American use of the strategy in the Pacific. The fact that Attu proved a buzz saw of opposition, and the fact that the Japanese later abandoned Kiska without a ground fight, in no way dissuaded planners from looking for similar opportunities to employ island-hopping as a strategic concept.

The idea of recapturing Rabaul, on New Britain, had been ingrained in Allied thinking since the Japanese wrestled it away from Australian forces early in 1942. MacArthur was a vocal proponent of the absolute necessity of doing so. He was clearly headed in that direction before the Japanese disrupted his plans by occupying Buna and forcing him to fight for Papua.

By the early summer of 1943, in the broad context of Aleutians operations and the debate between a central Pacific and southwestern Pacific advance, Washington planners began to ponder the economies that might result if Rabaul were neutralized rather than taken in a direct and likely prolonged assault. Doing so would benefit both Nimitz and MacArthur by permitting those resources to be allocated elsewhere in their respective theaters. The Joint Strategic Survey Committee came to favor the proposed central Pacific operations over Rabaul-bound Operation Cartwheel. Not only did the committee worry that the drive against Rabaul was, strategically speaking, merely a pushback against Japanese thrusts into the Solomons and at Buna, they also worried that it held “small promise of reasonable success in the near future.”1

By July 21, these staff discussions about isolating Rabaul had set George Marshall to thinking. He suggested to MacArthur that the ultimate objective of the Cartwheel operations be modified. Instead of assaulting Rabaul directly, why not encircle it and render it useless by capturing Kavieng, on the northern tip of New Ireland, and Manus, one of the Admiralty Islands? Marshall also suggested capturing Wewak, northwest of Lae, to spur the drive westward along the coast of New Guinea. This meant that MacArthur had to seize Lae, continue operations westward along the New Guinea coast, and bypass Rabaul rather than meet Halsey there.2

MacArthur was not convinced. He argued that a direct assault against Wewak would involve “hazards rendering success doubtful.” Interestingly enough, however, in rejecting the attack against Wewak, MacArthur did not propose to advance steadily toward it from Lae but rather to jump over it and seize a base farther west from which to isolate Wewak—exactly the sort of strategy Marshall was proposing against Rabaul. As for Rabaul itself, MacArthur remained of the mind that it would have to be captured—rather than merely neutralized—sooner or later, in part because he thought Simpson Harbor would make an excellent naval base from which to support his westward advance.3

On this latter point, Bill Halsey disagreed. At that moment, Halsey had his hands full with stiff enemy resistance on New Georgia, but he had long recognized that Rabaul would, in his words, “be a hard nut to crack.” Not only would the fighting be difficult—an estimated one hundred thousand ground troops waited in opposition—but also, once Rabaul was won, “we would not have anything worthwhile” that could not have been had elsewhere.4

The “elsewhere” decisions were several months off, but in the meantime, Marshall and King also opposed MacArthur’s fixation with Rabaul. The result at the First Quebec Conference in August of 1943 was that the Combined Chiefs of Staff, and ultimately Roosevelt and Churchill, approved the Joints Chiefs’ recommendation that Rabaul be neutralized, not captured. Momentarily, Kavieng was substituted for Rabaul as the primary target in the vicinity.5

Marshall dispatched a staff officer to MacArthur’s headquarters to brief the general on this decision, and MacArthur seems to have acquiesced to it rather than argue his position. He was in the midst of the Lae operation, and there is at least some speculation that he had begun to lean toward a similar decision regarding Rabaul. This may have been the result of interaction between his staff and the Washington planners as well as his own conversations with Halsey. Perhaps more to the point, Marshall reassured MacArthur that progress along the northern coast of New Guinea toward the oil fields of the Vogelkop Peninsula remained a priority. From there, the next logical objective was MacArthur’s cherished goal of Mindanao, although, Marshall warned him, “It may be found practicable to make this effort from the Central Pacific.”6

Meanwhile, Allied operations against Lae continued. Indeed, MacArthur had already employed a mini leapfrog maneuver to gain ground in his pursuit of it. Repeated air attacks and feints by Australian ground troops near Salamaua convinced General Adachi and his Eighteenth Army staff that MacArthur’s next major move would be directly against it. Accordingly, they steadily reinforced their frontline positions there. Instead, the Allied landings had occurred east of Lae, on Huon Gulf, decidedly behind the Japanese lines at Salamaua. The result was to isolate Salamaua’s defenders and eventually cause the death of two thousand Japanese troops and the loss of large quantities of materiel, provisions, and barges.7

Aside from the Salamaua deception, the Allied attack against Lae was a variation on a plan prematurely conceived by General Blamey and the Australians during the Buna campaign. The amphibious forces just landed would move westward toward Lae and join up with troops descending the Markham River valley from Nadzab, squeezing Lae between them. Since the rugged Markham Valley acted as a barrier between the Huon Peninsula and the rest of New Guinea, the hope was that this maneuver would not only trap the Lae garrison but also cut off Japanese forces on the peninsula from Madang, their next base to the west.8

The key to success was to get a large number of troops to Nadzab as quickly as possible. The solution was to drop 1,700 men from the American 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment on Nadzab and seize a prewar Australian airstrip so that brigades of the Australian Seventh Division could be flown in from a staging area at nearby Tsili Tsili and directly from Port Moresby shortly thereafter. Although the First Marine Parachute Battalion had fought at Guadalcanal and Tulagi on foot, this was to be the first use of airborne troops as such by Allied forces in the Pacific.9

As George Kenney briefed MacArthur on this airborne operation, he casually mentioned that he would be flying in one of the accompanying B-17s to observe what he called “the show.” MacArthur took exception to this and reminded his air commander that he had been ordered to stay out of combat. Kenney protested and told MacArthur that given the recent success of raids against Wewak and the fact that a weather front was expected to keep planes grounded in Rabaul, he didn’t expect any trouble from Japanese aircraft. “They were my kids,” Kenney told MacArthur, “and I [am] going to see them do their stuff.”

According to Kenney, MacArthur “listened to my tirade” and pondered this last comment before finally replying, “You’re right, George, we’ll both go. They’re my kids, too.” That caused Kenney to regret he had ever brought up the topic, but MacArthur was adamant, saying that he wasn’t afraid of getting shot, only a little worried that he might get airsick crossing the mountains and “disgrace myself in front of the kids.”10

MacArthur remembered the story a little differently. When he inspected the paratroopers, he said he found, “as was only natural, a sense of nervousness among the ranks.” He continued, “I decided that it would be advisable for me to fly in with them. I did not want them to go through their first baptism of fire without such comfort as my presence might bring to them.”11

Kenney arranged what he called a brass-hat flight of three B-17s to shadow the C-47 transports as they made their Nadzab run. He put MacArthur in the lead bomber, named Talisman, climbed aboard the number two plane himself, and had “the third handy for mutual protection, in case we got hopped.” MacArthur suggested they ride together, but Kenney convinced him that was tempting fate just a little too much.12

At 8:25 a.m. on September 5, 1943, the first C-47s rolled down the runway at Port Moresby. By the time the airborne flotilla assembled southwest of Nadzab, it numbered 302 aircraft from eight different fields. Six squadrons of B-25s led the attack, strafing Nadzab with their .50-caliber nose guns and dropping bombs. Six A-20s followed, to lay a smoke screen for the paratroopers jumping from ninety-six C-47s. Bevies of P-38s and other fighters circled at various altitudes, while the heavy bombers—twenty-four B-24s and four B-17s—pounded a Japanese position halfway between Nadzab and Lae to disrupt ground reinforcements. Five other B-17s, their bomb racks loaded with three-hundred-pound packages of supplies, circled the drop zone and disgorged their loads as needed in response to markers on the ground. High above the transport columns, MacArthur and Kenney flew in their brass-hat flight of B-17s.13

Kenney reported to Hap Arnold that MacArthur watched the whole assault “jumping up and down like a kid.” That seems out of character and a decided exaggeration, but it was nonetheless an impressive array of Allied airpower, and MacArthur was elated. The timing of the bomb runs, the fighter cover, and the air drops were near perfect, causing MacArthur, despite his thoughts of providing moral support, to admit, “They did not need me.”14

But Kenney had a surprise for MacArthur. “To my astonishment,” MacArthur wrote in his memoirs, “I was awarded the Air Medal.” The citation, which Kenney recommended, noted that MacArthur “personally led the American paratroopers on the very successful and important jump against the Nadzab airstrip” and “flew through enemy infested airlanes and skillfully directed this historic operation.” That, too, was a bit of Kenney exaggeration, and even MacArthur, while saying “this exceptionally pleased me,” graciously admitted, “I felt it did me too much credit.”15

Medals aside, MacArthur’s presence in a B-17 over Nadzab was a transformative event in his personal conduct in combat zones. The flight was certainly not without risk, and it was a long way from characterizations of Dugout Doug. It marked a return to the MacArthur of the trenches of World War I and stood in sharp contrast to his lone visit to Bataan and his failure to visit Eichelberger at Buna. It emboldened MacArthur to get out in the field more often.

By nightfall on September 5, the troopers had burned the tall kunai grass off the abandoned Nadzab airstrip, and the following afternoon the first transports, carrying elements of the Australian Seventh Division, landed. Within a week, engineers had constructed two parallel runways of six thousand feet each with a dispersal area capable of simultaneously handling thirty-six transports. This allowed the Seventh Division to hasten down the Markham Valley toward Lae. Salamaua fell on September 14 to Australian and American units that had linked up after the landings at Nassau Bay, and the Australian Seventh and Ninth Divisions entered Lae from opposite directions on September 16.16

The rapid collapse of Salamaua and Lae caused the Japanese considerable angst. Rather than wage a last-ditch defense, as they had at Buna and Gona, they conducted a withdrawal designed to save as many of their troops as possible. The result was a harrowing jungle march that nonetheless saw the bulk of nine thousand soldiers and sailors reach the north coast of the Huon Peninsula. This move became a small piece of a broad strategy to tighten Japan’s defensive perimeter throughout the entire Pacific.

One look at the map in Imperial General Headquarters told the rest of the story. In the South Pacific, Halsey gnawed away at the central Solomons and had just done his own island-hopping—bypassing Kolombangara in favor of a landing on Vella Lavella. To the north, the Gilbert and Marshall Islands lay exposed to any American advance through the central Pacific. In the northern Pacific, withdrawals from Attu and Kiska, in the Aleutians, had cost Japan its toehold in Alaska. It was time for Imperial General Headquarters to mandate a defensive line to be held at all costs.

The line drawn ran from western New Guinea in the face of MacArthur’s advance through Truk and the Carolines to Saipan and Guam, in the Mariana Islands. Rabaul, once considered an important hub by both sides, took on the character of a strong outpost, as did Kwajalein, in the Marshall Islands. This did not mean, however, that the Japanese would not aggressively defend them. In September, as Lae fell, Imperial General Headquarters dispatched the Seventeenth Division from Shanghai to Rabaul “to reinforce the troops manning the forward wall.”17

In organizing his Eighteenth Army for its new defensive role, General Adachi confronted a dilemma not unlike that which MacArthur had faced in defending the Philippines. From the Vogelkop Peninsula east to the Admiralty Islands and New Britain, there were thousands of miles of shoreline and hundreds of islands and inland locations that attackers might seize for airfield sites. Kenney had already proved he was adept at that, and Barbey’s budding amphibious forces promised to become an equal partner. If Adachi dispersed his troops too widely, he exposed them to selective attacks by larger forces, but if he concentrated them in certain strongholds, they risked being cut off by the type of leapfrog maneuvers both MacArthur and Halsey were beginning to employ.

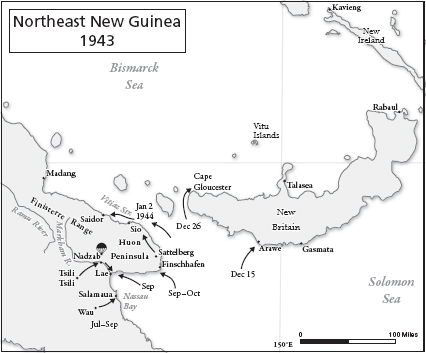

The fall of Lae had also caused the Allies to reevaluate their own strategic plans. MacArthur’s original timetable for the following round of Operation Cartwheel called for an assault against Finschhafen six weeks after the landings at Lae. Finschhafen, seventy miles east of Lae, near the tip of the Huon Peninsula, and Cape Gloucester, on New Britain, were considered essential to controlling the intervening Vitiaz and Dampier Straits. This would permit Allied naval vessels to pass from the Solomon Sea into the Bismarck Sea and effect landings to encircle Rabaul as well as advance along the coast of New Guinea. MacArthur assigned the assault against Finschhafen to George Wootten’s Australian Ninth Division and against Cape Gloucester to Walter Krueger’s Alamo Force.

Before embarking from Milne Bay for Lae, Wootten had gotten a hint that he might be required to dispatch one of his brigades to Finschhafen on short notice. Given the rapid demise of Lae, that came sooner than even he anticipated, when MacArthur decided on September 17 to invade Finschhafen immediately. Dan Barbey showed that he was getting the knack of amphibious operations by assembling four transports, eight LSTs, sixteen LCIs, and ten destroyers and landing Wootten’s Twentieth Brigade infantry group six miles north of Finschhafen just before dawn on September 22, almost a month ahead of the proposed schedule. As Commander Charles Adair, who had responsibility for scouting the landing site, reminisced years later, Finschhafen “was not too bad when you consider that we landed, in about four hours, the following: 5,300 troops, 180 vehicles, 32 guns, and 850 tons of bulk stores.”18

Part of MacArthur’s decision to expedite the Finschhafen landing was based on the rapid progress at Lae, but Willoughby had fueled his decision by estimating that Japanese defenders there numbered only 350. In fact, there were almost five thousand Japanese troops in and around Finschhafen. Adachi had also relieved his Twentieth Division of its Madang-Lae road-building project and ordered it to reinforce Finschhafen and nearby Sattelberg. This was not the first time Willoughby had made a major blunder in numbers, and it would not be the last. The Australians faced heavy resistance before reinforcements moving along the coast from Lae joined up with the landing force and secured the town on October 2.19

The quick thrust at Finschhafen—Willoughby’s faulty intelligence aside—initially looked to be inspired, but as elements of the Japanese Twentieth Division counterattacked, the Allied positions there and along the tip of the Huon Peninsula became very exposed. This did not keep MacArthur from prematurely announcing on October 4 that all enemy forces between Finschhafen and Madang had been “outflanked and contained.”20

Among those most disgruntled by this misplaced optimism was Wootten’s Ninth Division, whose troops were fighting fiercely between Finschhafen and Sattelberg to keep themselves from being outflanked and contained. Barbey landed a major reinforcement on the Finschhafen beach on October 20, but the official Australian war history groused, “MacArthur’s planners felt that Finschhafen would be a ‘pushover’ and that the operation could be considered as finished” even before the town was secured.21

At MacArthur’s strategic level, the next question became whether to order the Australians to push around the Huon Peninsula and capture intermediary points toward Madang or have Krueger strike at Cape Gloucester and secure the opposite side of the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits. Simultaneous blows might have been advisable, but Barbey lacked the ships to conduct both operations at the same time. Which to undertake first was a tricky decision.

Against this backdrop, the plans for Cape Gloucester caused dissension at MacArthur’s headquarters. Code-named Operation Dexterity, these plans called for Krueger’s Alamo Force to seize airfield locations at Cape Gloucester, on the western tip of New Britain, with a combined airborne and amphibious operation as well as to assault a forward Japanese base at Gasmata, on the southern coast. The invasion force at Gasmata would drive north to Talasea, on the northern coast, effectively lopping off Cape Gloucester and the western third of the island from Japanese control. For good measure, they would also capture the tiny islands of Long and Vitu, in the Bismarck Sea.

These were significant steps toward Rabaul, and they seem to have been premised on tightening the noose in preparation for an invasion of Rabaul rather than isolating and bypassing it. Indeed, the official US Army history notes—the decision to bypass Rabaul at the Quebec conference notwithstanding—that there seemed to be “a strategic lag” before that decision was reflected in the operational orders emanating from MacArthur’s headquarters. This was not necessarily out of any disregard on the part of MacArthur or his staff for the bypass decision but more likely a case of long-held inertia that took some time to reverse.22

George Kenney was the first to protest the Cape Gloucester plan. Operation Cartwheel’s original concept had been to encircle Rabaul with a ring of air bases, but Kenney told MacArthur that the bypass decision rendered this moot. Now that faster action was contemplated, it would take too long to develop Cape Gloucester into a viable base. By then, it would no longer be essential because the existing bases at Dobodura, Nadzab, and Kiriwina, as well as the one under construction at Finschhafen and whatever might be developed en route to Madang, could support further advances in the Admiralties and against Kavieng. Rabaul would wither on the vine while the thrust of MacArthur’s advance continued toward the Philippines instead of diverting back toward Rabaul.23

Stephen Chamberlin, MacArthur’s operations chief, took exception to Kenney’s view and asserted that airdromes at Cape Gloucester could be taken and upgraded in a timely manner and that they would ensure both tighter control of the Vitiaz Strait and closer support for future attacks. Even with Cape Gloucester, Chamberlin argued that Gasmata or another point on the southern coast of New Britain would be needed to control the straits and provide an emergency airfield for planes attacking Rabaul.

Admiral Arthur Carpender, for the moment still MacArthur’s senior naval commander, and Dan Barbey supported Chamberlin in the need to hold both sides of the straits. General Krueger agreed. But the admirals were far from keen on the operation against Gasmata, fearing that it would needlessly expose ships to Rabaul-based aircraft.24

With Chamberlin determined to seize Cape Gloucester, Kenney joined forces with Carpender and Barbey against the Gasmata operation. The proposed landing site, just east of Gasmata at Lindenhafen, was swampy even by New Guinea standards; the coral runway was located on an island and limited to 3,200 feet in length; and the Japanese were reinforcing the area with the recently arrived Seventeenth Division. Kenney’s deputy, Ennis Whitehead, who remained the tactical maestro behind Kenney’s air successes, offered his own analysis when he told Kenney, “Any effort used up to capture any place on the south coast of New Britain is wasted unless an airdrome suitable for combat airplanes can be constructed there.” Both air bosses, although confident of their growing air superiority, also thought Gasmata a little too close to Rabaul for adequate warning of incoming attacks.25

The matter was finally resolved on November 21 in a conference that included MacArthur, Chamberlin, Kenney, Carpender, and Barbey. While the navy continued to oppose Gasmata, they nonetheless wanted a PT boat base somewhere on the southern coast of New Britain from which to patrol the straits. Kenney claimed in his memoirs that it was his idea to substitute Arawe, a lightly defended harbor halfway between Gasmata and the straits. Conversely, Barbey remembered poring over charts with Carpender to find the solution. When they presented Arawe as an option, Barbey said that Kenney appeared relieved and promised better air cover to Arawe than he could provide to Gasmata.26

This plan was approved, but the dates initially selected for the Operation Dexterity landings—November 14 for Gasmata-Lindenhafen and November 20 for Cape Gloucester—had already been postponed once, in part because heavy fighting around Finschhafen had slowed construction of its supporting airfield. This had a ripple effect—because of the lack of nearby air cover, Barbey’s VII Amphibious Force was disrupted in stockpiling supplies, a task that had to be completed before Barbey could turn his ships loose from Finschhafen for the New Britain landings.

Given that amphibious invasions usually occurred during the new moon to avoid silhouetting the landing force, this meant that the New Britain landings would have to be made either prior to December 4 or after the full moon on December 11. MacArthur wanted to make the Cape Gloucester landing on December 4, but Krueger protested that because Barbey’s amphibious force would have to finish at Finschhafen, return to Milne Bay for assault troops, land the Arawe force, and reload for Cape Gloucester, there would not be time for rehearsals and that any ship losses at Arawe would hamper the main Gloucester force. MacArthur reluctantly agreed. The regiment-size landings at Arawe were set for December 15 and the full-blown assault on Cape Gloucester for December 26.27

In the midst of these operations, there was a new face on the US Navy side. Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid was the last senior officer to join one of MacArthur’s two inner circles: the tight-knit circle reserved for the Bataan Gang and, for lack of a better word, the “fighting” circle, made up of those commanders who were to earn MacArthur’s respect for their military accomplishments, including Kenney, Barbey, Krueger, and, somewhat begrudgingly, Eichelberger.

Born into a navy family in 1888, Kinkaid graduated from Annapolis in 1908. He served tours on battleships, including the Nebraska as part of the Great White Fleet, and developed a specialty in ordnance and gunnery. World War I found Kinkaid doing special assignments in between postings on the battleships Pennsylvania and Arizona. Afterward, he commanded a destroyer, attended the Naval War College, served as a naval adviser to the Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments in Geneva, and returned to battleships as executive officer of the Colorado. After Kinkaid’s stint in the Bureau of Navigation, Rear Admiral William D. Leahy supported his promotion to captain, and Kinkaid took command of the cruiser Indianapolis in 1937.

Kinkaid was interested in the plum diplomatic post of naval attaché in London, but when the job went to someone else, he accepted the post in Rome instead. This put him on the front lines of wartime diplomacy after Italy declared war on Great Britain and France. He returned to the United States in March of 1941 looking for a promotion to rear admiral, but he lacked a few months of required sea command because he had left the Indianapolis early for his Rome assignment. An Annapolis classmate then in the Bureau of Navigation came to his rescue and arranged a few months in command of a destroyer squadron based in Philadelphia to make up the time. The classmate, Arthur Carpender, was himself a newly minted rear admiral, and the irony of his favor would not become apparent for several years.

With his new flag rank, Kinkaid replaced Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher as commander of a cruiser division several weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Kinkaid led cruiser forces at the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway and afterward became commander of Task Force 16, which was built around the carrier Enterprise. Task Force 16 sailed near the Solomons as one of three task forces under Fletcher’s overall command, and Enterprise took a mauling in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons.28

By the fall of 1942, Halsey was in charge of the South Pacific Area, and Kinkaid and Enterprise were back on station there. This time, however, Kinkaid was the overall commander of two carrier task forces as a major Japanese force of carriers, battleships, and cruisers attempted another end run around the eastern Solomons. Halsey exhorted Kinkaid, “Strike—repeat—strike,” but a mix-up in radio communications gave the Japanese a head start in attacking the Americans. Kinkaid saved Guadalcanal, but the Enterprise came away damaged once again and the Hornet had to be scuttled—a decision for which Halsey and a host of naval aviators never forgave Kinkaid. The Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands was the last time a nonaviator commanded a carrier task force, and, more important for their future relations, it put Halsey and Kinkaid on less-than-friendly terms.29

Having weathered the major engagements of 1942 in the Pacific, Kinkaid returned to the United States for leave shortly thereafter and early in 1943 was sent to Alaska to command the North Pacific Force. Interservice rivalry was not limited to the South Pacific, and Kinkaid’s first job was to promote harmony among army, navy, and air force commands and cut through the tangled chain of command that had developed there. The result was success in the Aleutians campaign.

After MacArthur twice requested Arthur Carpender’s relief as his naval commander—among Carpender’s sins, from MacArthur’s viewpoint, were his less-than-aggressive use of ships off the New Guinea beachheads and his direct communications with the Navy Department—King and Nimitz determined that Kinkaid’s reputation in working with the army in Alaska and his combat experience in major Pacific engagements made him the most appropriate choice.30

MacArthur was finally to get his own fighting admiral, but Secretary of the navy Frank Knox prematurely announced the appointment at a press conference before either MacArthur or the Australian government had been consulted. The latter was required under the Allied agreement covering MacArthur’s appointment as supreme commander. MacArthur noted this lack of proper process to Marshall but made no objection to Kinkaid personally.

Marshall forwarded a kindly worded explanation from Admiral King that noted that Kinkaid’s orders had not yet been cut and asked whether Kinkaid would be acceptable to MacArthur. To King’s conciliatory message, Marshall added praise of Kinkaid’s work in the northern Pacific and noted: “His relations have been particularly efficient and happy with Army commanders, and… I think you will find him energetic, loyal, and filled with desires to get ahead with your operations. I think he is the best naval bet for your purpose.”31

MacArthur and Australian prime minister John Curtin concurred, and Kinkaid arrived in Brisbane as commander of Allied Naval Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area and commander of the Seventh Fleet. As such, he wore two hats, just as Halsey did. Kinkaid was responsible to MacArthur as the Allied naval commander and to King for the Seventh Fleet. (Kinkaid’s chain of command ran directly to King and not through Nimitz because Nimitz controlled only those units of the United States Fleet that ventured into the Southwest Pacific Area and not those permanently assigned there.) But one thing was certain: no matter how much MacArthur and his staff might rant and rave against the US Navy, it would have been difficult for King to have found an officer better suited in temperament, experience, and self-confidence to serve MacArthur than Thomas C. Kinkaid.

Kinkaid met at length with MacArthur on November 26, the day after Kinkaid formally relieved his old classmate Carpender, who had helped him get his first stars. Despite receiving a warm welcome from MacArthur, Kinkaid was not shy about delivering a dose of reality. Barbey’s amphibious forces, Kinkaid told MacArthur, would continue to make do with what they had or could beg on a ship-by-ship basis, but MacArthur’s dreams of receiving carriers, cruisers, and even some battleships would not be realized in the near future.

If Kinkaid’s oral history tapes are to be believed, the new Seventh Fleet commander went so far as to tell MacArthur that he didn’t think these larger ships should be assigned to the Seventh Fleet at that point because they would likely be held in Australian waters beyond the reach of Japanese air attack and thus be ineffective in directly engaging the Japanese fleet. It was a better use of limited resources, Kinkaid said, if they sailed with Halsey in the South Pacific or Nimitz in the central Pacific.32

Kinkaid was correct in this analysis, but within a few months, the tremendous surge of America’s industrial production would dramatically change the picture. In fact, Halsey had already received several of the new Essex-class carriers, and their planes were raining destruction in and around Rabaul in conjunction with Kenney’s bombers.

As Kinkaid engaged in his new assignment, there was more controversy over the Cape Gloucester operation. Instead of overall strategic importance and invasion dates, the discussion centered over tactics. No doubt influenced by the successful airborne assault on Nadzab, MacArthur’s planners called for a lone regiment of the by-then-veteran First Marine Division to land by sea at Cape Gloucester, while the Nadzab veterans, the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, jumped behind the beachhead and linked up with the marines at two Japanese airfields.

Alamo Force commander Krueger was never keen on this arrangement, and the First Marine Division’s commander, Major General William H. Rupertus, even less so, fearing that the assault logistics as well as Japanese defenses were far more complex than they had been at Nadzab. Add in uncertain weather, and there were just too many things that could go wrong with the proposed linkup.

According to the official history of the First Marine Division, MacArthur and Krueger visited division headquarters on Goodenough Island late in November and stumbled onto the division’s internal debate. When MacArthur casually asked how the Cape Gloucester plan was coming, the division operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel Edwin A. Pollock, boldly replied, “We don’t like it.” Asked by MacArthur what it was that he didn’t like, Pollock replied, “Sir, we don’t like anything about it.”

MacArthur raised an eyebrow in Krueger’s direction while Krueger glared at Pollock. MacArthur and Krueger left, but shortly afterward, general headquarters planners and the division’s staff held a joint planning session, undoubtedly at MacArthur’s directive. The airborne assault was scrapped and the entire First Marine Division ordered in at full strength to take the beaches with plenty of support. It was an instance of MacArthur listening to his troops in the field and not just to the planners in his headquarters. It was also a case of MacArthur listening to the navy’s Marine Corps and not his army planners.33

The other piece of the Cape Gloucester operation that concerned the navy was air cover for Barbey’s landing forces. According to Barbey, Kenney had beefed up the air cover over the Finschhafen beaches only “after a bit of nudging by MacArthur.”34 Barbey was determined to get that much or more for Cape Gloucester.

With Barbey occupied with the landing at Arawe, it fell to Kinkaid to emphasize Barbey’s concerns to MacArthur. Still in his first few weeks on the job, Kinkaid once again did not mince words. He told a conference at MacArthur’s headquarters—where Kenney was present—that while the navy maintained combat air patrols over an objective, army planes sat on the ground until an attack was imminent. The problem with that approach, Kinkaid said, was that “bomb holes on an airfield could be filled in, but a bombed ship might be lost.” MacArthur listened intently, then responded, “You can tell Barbey, you can assure him that he will have adequate air cover to go into Gloucester, and he’ll have better cover than he has ever had.”35 Kenney got the point, and it turned out to be true.

On December 15, the 112th Cavalry Regiment and a field artillery battalion landed at Arawe to light resistance after Kenney’s air forces had pounded Gasmata and Cape Gloucester as a diversion. On Christmas Day in 1943, the First Division marines embarked from Oro Bay, Goodenough Island, and Milne Bay for Cape Gloucester and went ashore there the next day. Initial light resistance led to heavier fighting around the airfields until they were secured on December 30. Heavy fighting continued, but medium and light tanks landed by Barbey’s LSTs finally won the day. It also helped that Allied air attacks pounded the defenders and generally cut them off from support from Rabaul.36

The landings at Arawe and Cape Gloucester proved successful, but in hindsight they renewed Kenney’s initial question about whether any attack on New Britain was essential to the strategy of bypassing Rabaul. Willoughby waxed poetic about the result and claimed after Gloucester, “The approach to the Admiralties lay miraculously open, with a Japanese Army on each flank rendered powerless to hinder the projected breakthrough.” Willoughby went on to say that in context, “‘miraculous’ is a superficial word. To immobilize with a relatively small force the Japanese Eighth Army on the Rabaul flank represents a professional utilization not only of astute staff intelligence but of time and space factors cannily converted into tactical advantage.”37

Others weren’t so sure. While these landings pushed Japanese forces back toward Rabaul, naval chronicler Samuel Eliot Morison claimed, “Arawe was of small value. The harbor was never used by us; the occupation served only to pin down some of our forces that could have been used elsewhere.” As for the capture of Cape Gloucester, Morison found it “an even greater waste of time and effort than Arawe.” His main point was that the bypass of Rabaul should have been made to include all of New Britain. “With the Huon Peninsula in our possession,” he concluded, “a big hole had been breached in the Bismarcks Barrier and there was nothing on Cape Gloucester to prevent General MacArthur from roaring through Vitiaz Strait to the Admiralties, Hollandia and Leyte.”38

Indeed, MacArthur chomped at the bit to get on with the drive westward from the Huon Peninsula toward Madang. He had found the intermediary point between Finschhafen and Madang from which to impede the Japanese retreat and put Kenney’s planes that much closer to the Admiralties and Wewak. The location was Saidor, on the coast of the Vitiaz Strait, around two-thirds of the way from Finschhafen to Madang. MacArthur assigned the task to the Thirty-Second Division of Krueger’s Alamo Force, which had been held in reserve for the New Britain operations.

Krueger protested. Conservative plodder that he was, Krueger pointed out that his command was already engaged in two landings on New Britain and that MacArthur’s January 2, 1944, timetable for Saidor left no reserve and stretched the limits of Barbey’s amphibious force yet again. “I am most anxious,” MacArthur replied, “that if humanly possible this operation take place as scheduled. Its capture will have a vital strategic effect which will be lost if materially postponed.”39

The strategic effect MacArthur wanted—cutting off retreating Japanese troops and extending his forward air reach—showed that, the diversion of resources to New Britain notwithstanding, he was embracing the leapfrog concept of bypassing, or island-hopping.

The question of whose idea it was to bypass Rabaul would be forever debated. Pro-MacArthur accounts during the postwar years gave rise to the legend that not only had MacArthur originated the plan to bypass Rabaul, he had also conceived the entire strategy of island-hopping. In reality it was much more of a team effort and gradual evolution. Indeed, MacArthur initially opposed bypassing Rabaul, but when it served his purposes, no commander embraced island-hopping more readily than MacArthur.40