CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Gambling in the Admiralties

Douglas MacArthur didn’t waste any time committing his forces to new action in 1944. On January 2, 6,800 men of the Thirty-Second Infantry Division of Krueger’s Alamo Force landed at Saidor, on the northeastern coast of New Guinea. Given the ongoing operations at Arawe and Cape Gloucester, on New Britain, Krueger protested the leap as stretching his forces too thin, but MacArthur wanted to cut the Japanese Eighteenth Army in half and trap its eastern units on the Huon Peninsula.

Dan Barbey’s amphibious forces were also stretched thin by the Saidor assault, but Barbey later claimed, “The Saidor landing was an excellent example of MacArthur’s concept of ‘hit them where they ain’t’ and ‘bypass the strongpoints.’” Barbey said both phrases translated into “big gains with little losses.” Saidor had “good beaches, a good airstrip, and was weakly defended.”1 Kenney especially welcomed the airstrip. Lying 125 miles west of Finschhafen and two-thirds of the way to Madang, Saidor was a key pivot point from which his planes could support both an advance farther west along the New Guinea coast and a move northward against the Admiralty Islands, the latter being the final step in the isolation of Rabaul.

The immediate priority, however, was to effect MacArthur’s contemplated entrapment of the Japanese forces east of Saidor. They were under pressure from the Australian Ninth Division, moving northward from Finschhafen. Despite encountering minimal enemy resistance at the Saidor beachhead and soon having fifteen thousand men ashore, Brigadier General Clarence Martin’s task force delayed moving inland to cut the Japanese escape route. This was the result of garbled communications and multiple warnings from Krueger that they should prepare the Saidor area defensively in anticipation of a counterattack rather than link up with the Australians and pinch the Japanese between them.

Meanwhile, Japanese Eighteenth Army commander Adachi visited divisional headquarters at Kiari and Sio, between Finschhafen and Saidor. After evaluating the situation, he received orders from General Imamura in Rabaul to move these troops westward and concentrate on defending Madang and Wewak rather than force an action at Saidor. Consequently, the Japanese undertook their own form of leapfrogging, and the Twentieth and Fifty-First Divisions surreptitiously retreated from Kiari and Sio via an inland route that avoided the Americans recently landed at Saidor. Adachi left Sio by submarine deeply depressed because the two divisions would be forced to go through an arduous retreat reminiscent of the withdrawal from Lae.

Their departure left the way open for the Australian Ninth Division to march into Sio on January 15. Not until February 6, however, when American advance patrols in the steep, jungle-clad mountains beyond Saidor reported large numbers of Japanese troops struggling along the inland trail, did Martin know for certain that Saidor would not be attacked. An estimated ten thousand Japanese troops—only half the strength of those divisions two months before—survived the grueling two-hundred-mile withdrawal to Madang.2

Through operational delays and unwillingness on the part of the Japanese to engage, MacArthur had failed to close the trap he intended on the Huon Peninsula. But the concentration of these survivors and other reinforcements that Adachi rushed to Madang and Wewak set MacArthur and his planners to thinking about a much grander leap in the future. Until then, aside from the Saidor airfield, the biggest prize had come at Sio.

As the headquarters’ radio platoon of the Japanese Twentieth Division broke down their equipment for the torturous retreat on foot, they deemed the division’s codebooks, substitution tables, and key registers too heavy to haul along. They merely tore off the covers as proof of destruction, put the bulk of the material in a steel trunk, and buried the trunk near a streambed, hoping that rising water would obliterate the remainder.

As Australian troops leery of booby traps moved into the abandoned Japanese headquarters area, they detected what they first took to be a buried land mine. Demolition experts soon found otherwise and unearthed the trunk. An intelligence officer quickly recognized the treasure trove. The soggy mess was transported to MacArthur’s Central Bureau, in Melbourne, and it gave his Ultra efforts a huge boost. With the Sio documents in hand, US Army cryptologists decrypted more than thirty-six thousand Japanese army messages in March of 1944 alone. The result was that code breakers could monitor Japanese army signals with the same speed and precision as they did Japanese naval traffic.3

With the advance to Saidor secure, the Joint Chiefs directed MacArthur to close the ring around Rabaul by invading the Admiralty Islands. Centered on the main island of Manus and nearby Los Negros, this island cluster forms the northwestern boundary of the Bismarck Sea. The Japanese had occupied the islands in 1942 and developed two airfields, but they generally ignored the fine anchorage of Seeadler Harbor. Formed by the horseshoe-shaped curvature of Los Negros against the eastern end of Manus, its protected waters are six miles wide, twenty miles long, and 120 feet deep—the perfect assembly, provisioning, and repair point for fleet operations against the Philippines. The chiefs set April 1 as the target date for the invasion.

Meanwhile, Halsey’s parallel thrust through the Solomons had resulted in the invasion of Bougainville in November of 1943. Fighting was tough and would continue for months, but in the interim, Halsey looked ahead for another opportunity to bypass heavy opposition. His next stop was supposed to be Kavieng, on New Ireland, though Halsey had other ideas. Complicating both his plans and MacArthur’s were Nimitz’s activities in the central Pacific and the requirement for the main United States Fleet to support amphibious operations anywhere in the South or Southwest Pacific Areas.

The central Pacific campaign began in earnest on November 20, 1943, with the invasion of Makin and Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands. Code-named Operation Galvanic, the campaign provided a steep learning curve and demonstrated that naval firepower alone could not eliminate deeply dug-in fortifications, particularly on volcanic atolls. Nimitz came under harsh criticism from all sides—including from his marine commander, MacArthur, and the public at large—for the resultant casualties as well as for his decision to attack the Gilberts in the first place instead of bypassing them and attacking the Marshalls directly. But as in the Aleutians and MacArthur’s own experiences in Papua, certain lessons of amphibious warfare and specific geography (cold-weather operations, jungle warfare, coral-fringed landing sites) had to be learned somewhere.

Nimitz applied the lessons of Tarawa to the Marshalls invasion and, against the advice of his top commanders, chose to strike directly for the main Japanese base at Kwajalein rather than nibble away at the outer islands. Supported by the main Pacific Fleet, whose growing collection of fast carriers was given the task of blocking reinforcements from Truk and the Marianas, this assault began on February 1, 1944. Within a week, Kwajalein was secure. Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance urged Nimitz, King, and the Joint Chiefs to keep the drive rolling and seize the atoll of Eniwetok, four hundred miles west of Kwajalein, before it could be reinforced. With a circumference of fifty-some miles, the Eniwetok lagoon provided the largest natural harbor in the Pacific. By mid-February, this, too, had been accomplished.4

Douglas MacArthur was probably the only American military officer celebrating these successes with less than unqualified enthusiasm. Despite the dictates of Combined Chiefs of Staff memorandum 417, agreed upon at the Cairo conference for twin offensives via both the Central and Southwest Pacific Areas, MacArthur remained adamant that his New Guinea–Vogelkop–Mindanao axis provided the key to defeating Japan. Having convinced himself that he was to be given “a big piece of the fleet” and that the British were likewise going to contribute ships, MacArthur decided he needed a veteran, high-profile naval commander all his own.

When Halsey made a brief visit to Brisbane in December of 1943 to confer with MacArthur before heading to the States for conferences with Nimitz and King, he was taken aback by the unexpected offer. “How about you, Bill?” MacArthur pointedly asked Halsey. “If you come with me, I’ll make you a greater man than Nelson ever dreamed of being!” Halsey responded graciously but said he would have to take the matter up with Nimitz and King. He did—and that’s the last he ever heard of it, either from MacArthur or the US Navy.5

Halsey and MacArthur also discussed their coordinated next moves—MacArthur against the Admiralties and Halsey against Kavieng. Yet when Halsey got to his conference with King, the admiral asked him, “When are you going to be ready to take Rabaul or Kavieng?” Halsey, in what he recalled was a flippant manner, replied, “Why take either one?” Then, as Halsey told the story, “in a most delightful sarcastic tone, which you know as well as I do, [King] said ‘and what have you to suggest in lieu thereof.’” Halsey replied with one word, “Emirau.”6

Emirau is a tiny island eight miles long and two miles wide located ninety miles north of Kavieng. It was unoccupied and offered a location for an airfield, which Halsey thought would make an assault against Kavieng unnecessary. King appeared noncommittal, and Halsey went east on leave. By the time the schedule for the Southwest Pacific and South Pacific operations was next discussed in depth, at a planning conference in Honolulu at the end of January, Halsey’s plane was grounded by bad weather in the States and he was unable to attend.

In his absence, Sutherland, representing MacArthur and the original plan, argued convincingly that MacArthur deemed an assault by Halsey’s South Pacific forces on Kavieng, not Emirau, to be essential. Nimitz, for his part, agreed to provide long-range carrier support by making a major strike against Truk around March 26 in anticipation of the coordinated Admiralty and Kavieng landings on April 1.7

Momentarily stymied in his bid to take Emirau, Halsey invaded the Green Islands. This tiny group of four coral atolls lies north of Bougainville and east of Rabaul and offered yet another potential airfield from which to attack Kavieng or Rabaul. Troops from the New Zealand Third Division, previously in the Solomons, landed there on February 15 to only minimal ground resistance and a last-ditch air assault from Rabaul. Within two days, a PT base was operational, and by March 4, navy Seabees had constructed a five-thousand-foot fighter airstrip, to be followed shortly thereafter by a longer bomber strip.8

Against this backdrop, MacArthur pondered his directive to wait until April 1 to invade the Admiralties, particularly in light of Nimitz’s successful jump from Kwajalein to Eniwetok at least two months ahead of schedule. MacArthur’s fixation on Kavieng notwithstanding, he was well aware from Kenney’s air-operations reports that Rabaul had been rendered largely ineffective. Continuous bombardments had reduced its strength so much that, after February 19, there were no warships in its harbor, and no fighters rose to challenge Allied bombers.

An estimated one hundred thousand well-supplied Japanese ground troops remained in Rabaul, but they were to prove that in the war of island-hopping, ground forces without coordinated naval and air strength were largely impotent—unless the enemy decided to attack them directly in a ground assault. Japanese naval aircraft effectively abandoned the skies over eastern New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Solomon Islands while army planes concentrated at Wewak to block MacArthur’s advance along the New Guinea coast. The door to the Admiralties appeared to be wide open.9

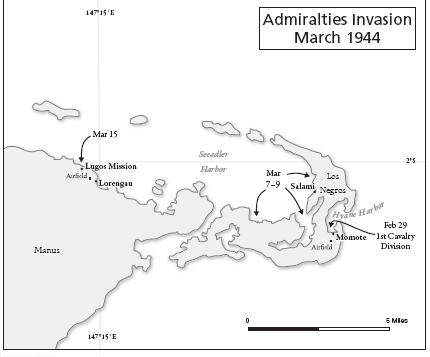

George Kenney and his trusted deputy, Ennis Whitehead, were determined to keep it that way. Whitehead in particular wanted to get the planned Admiralties invasion out of the way and have his flank covered so he could concentrate operations against the Japanese air buildup around Wewak. Kenney was always looking for an opportunity to seize an airfield in a quick strike, as he had done at Nadzab and other locations in New Guinea. By February 6, their attacks had rendered the airfields at Lorengau, on Manus and Momote, on Los Negros, unserviceable, with no sign of enemy aircraft. Antiaircraft fire had stopped, but unbeknownst to them, this was because the Japanese commander had ordered his defenders to conceal their positions for the time being.

Consequently, on February 23, Whitehead showed Kenney a reconnaissance report attesting that three B-25s had lazed for ninety minutes at low altitudes over the Admiralties without drawing any opposition and without detecting any ground movement. According to Whitehead, the whole archipelago looked “completely washed out,” and he recommended that a reconnaissance party be landed at once to take a look.10

Kenney, who had been with Sutherland in Honolulu and had been part of those discussions, was back in Brisbane when he received Whitehead’s report. Judging, in his words, that “Los Negros was ripe for the plucking,” Kenney hurried upstairs to MacArthur’s office. He proposed to seize the Momote airfield immediately with a few hundred troops and some engineers and then use it to control the islands rather than making the full-scale assault directly into Seeadler Harbor as planned on April 1. According to Kenney, MacArthur paced back and forth as Kenney expounded on the idea, then stopped suddenly and said, “That will put the cork in the bottle. Let’s get Chamberlin and Kinkaid up here.”11

MacArthur’s operations officer and naval commander quickly bought into the plan and coordinated it with Krueger’s Alamo Force. One thousand men from the First Cavalry Division would board two destroyer transports (APDs) at Oro Bay and sail north to Los Negros in just five days’ time. It was a huge gamble. As the US Army official history points out: “MacArthur was sending a thousand men against an enemy island group approximately one month ahead of the time that his schedule had originally called for a whole division to make the invasion.”

What’s more, there was a wide difference of opinion as to how many Japanese troops—if any—remained on Los Negros and nearby Manus. Whitehead told Kenney that there were no more than three hundred Japanese defending the islands, although how he arrived at that number is unclear. Willoughby, who had badly underestimated the Finschhafen defenders, gave an estimate of 4,050. The First Cavalry Division’s own intelligence estimates pushed that figure to 4,900, although in its field order it noted that air reconnaissance had shown no signs of enemy occupation.

In fact, Willoughby’s use of Ultra had correctly identified the Japanese units present, and this time his estimate of strength was about right. The men from “the First Team,” with the emblem of a horse’s head on their shoulder patches, might be sailing into a buzz saw. Aware that Whitehead’s estimate did not jibe with Willoughby’s, MacArthur ordered the First Cavalry Division to field a second force of 1,500 combat troops and 428 Seabees to land two days after the initial landings if the decision was made to keep the reconnaissance force on Los Negros. The remainder of the division was to follow as necessary.12

An issue that would become more pertinent six months later was that the Admiralties operation involved three separate naval forces under three separate chains of command: Halsey’s naval forces, reporting to him as SOPAC commander; Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet, reporting to him and then MacArthur as CINCSWPA; and any Pacific Fleet units that might play supporting or diversionary roles, including Spruance’s Fifth Fleet, reporting to Nimitz as CINCPAC. Chamberlin suggested that in the event of a major naval engagement, the command of those three forces should reside with Halsey as the senior admiral. “This suggestion was accepted,” according to the US Army official history, “although for some reason it was not followed in similar situations at Hollandia and Leyte.”13

Then MacArthur made a brash decision. Just as he had done with Kenney in the air attack on Nadzab, he decided to accompany the troops on their reconnaissance-in-force, claiming that he would thus be on the scene to decide whether to evacuate the beachhead or hold it. When MacArthur invited Kinkaid along, the admiral could hardly decline, and the invasion force suddenly swelled from two APDs and four destroyers to include two cruisers and another four destroyers. Years later, Kinkaid claimed that the cruisers were necessary because a destroyer “had neither accommodations nor communications suitable for a man of MacArthur’s position” and that it was “poor practice to send but one ship of any type on a tactical mission.”14

Before MacArthur sailed into the fray at Los Negros, however, he fired a heavy barrage against Chester Nimitz and the US Navy in a lengthy memo addressed to the chief of staff. MacArthur’s song had a familiar refrain: the navy wanted to usurp his command and fold his Southwest Pacific Area into the broader Pacific Ocean Area, the command of which Nimitz held as one of his two hats.

This latest exchange had started with a cable MacArthur had sent Marshall earlier in February in which he once again urged the New Guinea–Vogelkop–Mindanao axis as the best route to the Philippines. He criticized the central Pacific offensive as lacking a “major strategic objective” and being ineffective as an approach to the Philippines because of the distances involved and the lack of major airfields and fleet bases. MacArthur strongly recommended that after the operations in the Marshalls, “the maximum force from all sources in the Pacific [should] be concentrated in my drive up the New Guinea coast.”15

Admiral King took exception, of course, and remarked that MacArthur must not have “accepted the decisions of the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Sextant [Cairo]” about dual offensives. Nimitz’s response had been action-oriented, as Spruance rapidly pushed beyond the Marshalls and seized Eniwetok, admittedly nine hundred miles farther from Mindanao than MacArthur’s position at the time but also four hundred miles closer to Japan.16

But Nimitz was also interested in using Seeadler Harbor, in the Admiralties, after its capture by MacArthur as a base for the Pacific Fleet. He consequently recommended that, after its capture, Manus Island be assigned to Halsey’s South Pacific Area for development and control. This seemed logical in many quarters, particularly because Halsey’s staff—not MacArthur’s—had already been working on harbor plans and because the island was near the dividing line between the Southwest Pacific and Central Pacific Areas. MacArthur saw the matter quite differently.

MacArthur claimed that by wanting to control Manus Nimitz was projecting his own command “into the Southwest Pacific by the artificiality of advancing South Pacific Forces into the area.” Harking back to earlier proposals to put the entire Pacific under Nimitz’s supreme command, MacArthur found this relatively minor boundary change to be a step toward that goal and predicted that it would “be followed by others until the desired result is effected.”

Such a move, MacArthur asserted, would disrupt relations with the Australians, demoralize soldiers and the general public, and reflect poorly upon his capacity to command. If Manus and Seeadler Harbor were assigned to the South Pacific Area, it was evidence that the ultimate issue was the command of the campaign to retake the Philippines. If he were denied that command, MacArthur was convinced that “my professional integrity, indeed my personal honor would be so involved that, if otherwise, I request that I be given early opportunity personally to present the case to the Secretary of War and to the President before finally determining my own personal action in the matter.”17

George Marshall must have sighed upon reading this. As he usually did, the chief of staff patiently worked to defuse the matter. MacArthur should indeed retain command of bases in his area, Marshall told him, but it was essential to the war effort that naval facilities be developed “as desired by the fleet and that the fleet will have unrestricted use of them.” There was no grand conspiracy, and Marshall had heard nothing about boundary changes or “any idea that control of the campaign for recapture of the Philippines should be taken from you.”

If “a real military reason” arose for any changes, they would be made, Marshall said, but he did not “see them in prospect.” As for the oft-used gauntlet of MacArthur’s “professional integrity and personal honor,” Marshall assured him they were “in no way questioned or, so far as I can see, involved.” But should MacArthur still desire to do so, Marshall said he would willingly “arrange for you to see the secretary of war and the president at any time on this or any other matter.”18 Meanwhile, MacArthur was out the door and on his way to attack the harbor that had just caused him so much anguish.

Early on the morning of February 27, with Dusty Rhoades at the controls, MacArthur’s B-17, the Bataan, lifted off from the Archerfield airport, outside Brisbane, with MacArthur and Kinkaid on board and headed north. At the usual refueling stop at Townsville, the trip almost came to a premature end when the bomber’s brakes failed to hold after landing on a short runway, and Rhoades “narrowly averted a crack-up.” They flew on to Milne Bay, where MacArthur and his party boarded the cruiser Phoenix late that afternoon.19

That same day, a stealthy reconnaissance conducted by a six-man scouting party that had landed from a PBY Catalina floatplane paddled a rubber raft off Momote and Hyane Harbor and reported that the wooded area between Momote and the coast was “lousy with Japs.” Whitehead worried that Kenney had gotten himself and MacArthur “out on a limb,” but Kenney discounted this report, claiming that “twenty-five Japs in those woods at night” might well make it appear that the place was “lousy with Japs.”20

Among MacArthur’s small entourage on the Phoenix was Roger O. Egeberg, a medical doctor from Cleveland, Ohio, who had spent a year at Milne Bay as a surgeon with a field hospital. Shortly after being reassigned to Brisbane, Egeberg was summoned for an interview with MacArthur. The general was looking for a personal physician to replace Charles Morhouse, who was returning to the States after having been with him since Corregidor. Egeberg was at first leery of the assignment, but he quickly became a MacArthur admirer, and MacArthur in turn took to him, even though on one of his first visits Egeberg casually suggested that little Arthur be given nothing more than a day or two of rest to get over a fever.

Barely had Egeberg settled into his quarters at Lennons Hotel when Lloyd “Larry” Lehrbas, the general’s assistant public relations officer, warned him to be ready for a trip. Egeberg was in his cabin on the Phoenix the night before the Los Negros landing when a marine guard knocked on his door and told him that MacArthur wanted to see him. Egeberg found the general in an excited state, restlessly circling his little stateroom. Egeberg quickly took his pulse and found it “strong, slow and regular.” MacArthur brushed off any further examination but launched into a long discourse on his youth, West Point athletics, and early assignments in the Philippines. After an hour or so, he calmed down and said he would like to go back to sleep.

The next morning, as they assembled in the predawn darkness to watch preparations for the landing, MacArthur grinned and told Egeberg, “Doc, you missed that diagnosis last night. I went back to bed after you left and pretty soon I began to feel excited again.” MacArthur claimed he discovered that, at the speed the cruiser was moving, the foot of his bed was several inches above his head, and when he made up the bed the other way, he finally got a restful sleep.21

Egeberg’s story aside, it is likely that MacArthur was more than a little keyed up by the prospect of his first close encounter with the enemy since his days in the trenches with the Rainbow Division. No doubt he also pondered the prospects of success for the gamble he was about to make as he watched the first wave of troops climb down cargo nets into the waiting landing craft.

Sporadic fire from coastal guns dogged the troops as they made for the beach, but well-placed shells from the cruisers and an accompanying destroyer quickly silenced them. This wave hit the beach at 8:17 a.m. on February 29, and by 9:50 a.m., a portion of the Momote airfield was in American hands. Three hours later, the entire landing force was ashore. Two soldiers were killed and three wounded, and a like number of sailors was lost on one of the landing craft.

Five Japanese were reported slain, but there was an uneasy air about the apparent success. To many troops moving forward, it appeared as if the Japanese defenders had melted inland. The landing force commander, Brigadier General William C. Chase, reported to Krueger, “Enemy situation undetermined.” In part this was because Colonel Yoshio Ezaki’s garrison had expected a concerted landing via Seeadler Harbor. By coming in the back door of Los Negros, at tiny Hyane Harbor, the First Cavalry Division troops caused an initial surprise and avoided the bulk of Ezaki’s defenses, reports of the area being “lousy with Japs” notwithstanding.22

MacArthur, Kinkaid, Lehrbas, and Egeberg came ashore at 4:00 p.m. MacArthur’s mind was on the decision to withdraw or stay, but he took time to award a Distinguished Service Cross to the first man ashore. Immediately afterward, as Lehrbas reported in his press release, MacArthur “walked through the muck and blasted palms to inspect the extent and condition of the Momote Airfield disregarding possible Jap snipers.” He was reported to have admonished Chase, “You have all performed magnificently. Hold what you have taken no matter against what odds. You have your teeth in him now. Don’t let go.”23

Had Colonel Ezaki chosen that moment to launch a concerted counterattack, MacArthur and the entire beachhead might have been overwhelmed. But Japanese forces were still spread thin and reacting slowly to both the surprise of the landing and its location at Hyane Harbor. Nonetheless, the obvious uncertainty and danger raises the questions of why MacArthur accompanied the expedition and why he went ashore. By his own account, MacArthur did not mention that he had gone ashore, saying only, “I was relying almost entirely upon surprise for success and, because of the delicate nature of the operation and the immediate decision required, I accompanied the force aboard Admiral Kinkaid’s flagship.”24

Roger Egeberg offered a less direct version of the story. Walking along the Momote runway, MacArthur stopped to look at two dead Japanese soldiers. Egeberg heard the voices of other Japanese in the nearby woods. While they were walking, Egeberg positioned himself on the general’s left, between MacArthur and the woods on the far side of the strip. When they turned around to come back, Egeberg took up a similar position, even though he was then on the general’s right, a clear violation of protocol. One martinet called Egeberg out on it and demanded rather loudly, “Shouldn’t you be on the other side of the General?” MacArthur heard him, looked around, and said, “I think I know why Doc is there. This is not a parade ground.”25

After they were back on board the Phoenix, MacArthur had one more comment for Egeberg. “Doc,” he said, according to Egeberg, “I noticed you were wearing an officer’s cap while we were ashore. You probably took a look at me and put it on. Well, I wear this cap with all the braid. I feel in a way that I have to. It’s my trademark… a trademark that many of our soldiers know by now, so I’ll keep on wearing it, but with the risk we take in a landing I would suggest that you wear a helmet from now on.” That same evening, MacArthur took one of his few drinks of the war when he had Egeberg “prescribe” a shot of bourbon as “a little medicine in celebration of this successful reconnaissance in force.”26

That evening, the Phoenix, an accompanying cruiser (the Nashville), and six destroyers departed the Los Negros beachhead for New Guinea, leaving two destroyers on station. Lehrbas released a second press release, noting that “the assault on the Admiralty Islands was carried out under the immediate observation of General MacArthur” because the operation was “one of the most important of the entire campaign and as is his practice, [he] wished to be present at the crisis.”27

But there was a major difference between this communiqué and those issued earlier in the war. Instead of begrudging his subordinates their publicity, MacArthur named three ground commanders, four naval commanders, and air-operations chiefs Kenney and Whitehead as having led the operation. It was a far cry from his bristling over Eichelberger’s press after Buna.

Arriving at Finschhafen the next morning, March 1, MacArthur and his group found Rhoades and the Bataan waiting for them, and they made the hop back to Port Moresby for the night. Rhoades described MacArthur as “in rare humor” and “most pleased over the success of the landings.” Even so, Rhoades wondered about MacArthur’s reported stroll along the Momote runway. “I hate to see him take these chances,” Rhoades confessed to his diary, “but he wants to do it and it instills respect in his troops, I guess.”

The next day, Rhoades delivered MacArthur and Kinkaid back to Brisbane in time for dinner.28 But on Los Negros, things were not yet fully calm. As MacArthur sailed away, Colonel Ezaki’s defenders counterattacked with a vengeance but without concentrating their forces. The First Cavalry troops dug in, and by daylight on March 1, most of the attackers had withdrawn three to four hundred yards. A tense standoff followed, but by the morning of March 2, the supporting force of ground troops and Seabees unloaded and joined the action.29

The Seabees’ Fortieth Naval Construction Battalion played a critical role in capturing the remaining portion of the Momote airstrip, and MacArthur later recommended it for a Presidential Unit Citation. Landing during a critical situation, they went to work clearing and repairing the airstrip and bulldozing fire lanes into the surrounding jungle. But, MacArthur boasted, they “still found time during their few hours of leisure off duty to rout out small bands of the enemy, locate and report pillboxes, and otherwise carry the offensive to the enemy’s positions.”30

Japanese resistance throughout the Admiralties continued for weeks, but Los Negros was largely cleared within ten days of the invasion. The Momote airstrip was made operational for fighters in short order, and the second airfield—at Lorengau, on Manus—was captured after a landing at Lugos Mission. MacArthur’s communiqué of March 10 reported, “Our naval and supply ships entered Seeadler Harbor without interference.” Nonetheless, it was not until May 18 that Krueger officially declared the Admiralties operation complete. Only seventy-five of Ezaki’s defenders—a number that did not include Ezaki himself—survived to surrender. The Japanese dead amounted to 3,280, and Krueger estimated that another 1,100 had already been buried, coming close to Willoughby’s intelligence estimate. The cost to the First Cavalry Division totaled 326 men killed, 1,189 wounded, and four missing.31 There was, however, to be one more fight over the Admiralties.

Barely had MacArthur returned to Brisbane on the evening of March 2 when he revisited the issue of who would control the facilities soon to be under construction in Seeadler Harbor. Halsey’s representative on MacArthur’s staff alerted Halsey, in Nouméa, that a crisis was at hand and requested that he come to Brisbane at once. Halsey did so with his chief aides in tow and went immediately to MacArthur’s office to meet with the general, Admiral Kinkaid, and key members of their respective staffs.

As Halsey recalled, “Even before a word of greeting was spoken, I saw that MacArthur was fighting to keep his temper.” Having not yet received Marshall’s quieting response to MacArthur’s pre-Admiralties rant over shifting boundaries and concomitant control, MacArthur had his sights set on Halsey as a coconspirator with Nimitz. “I had had no hand in originating the dispatch,” Halsey recalled. “I did not even hear of it until after it had been sent; but MacArthur lumped me, Nimitz, King, and the whole Navy in a vicious conspiracy to pare away his authority.”

Angry as MacArthur was, Halsey’s recollection offers an insight into the general’s temperament. Confessing that, when he got angry himself, strong emotion made him profane, Halsey said that MacArthur did not need that crutch because “profanity would have merely discolored his eloquence.” And eloquent but forceful the general was for around fifteen minutes—by MacArthur standards, a short presentation.

He had no intention of submitting to such interference, MacArthur thundered, and, according to Halsey, “he had given orders that, until the jurisdiction of Manus was established, work should be restricted to facilities for ships under his direct command.” When he had finished this diatribe, MacArthur jabbed his pipe stem in Halsey’s direction and demanded, “Am I not right, Bill?”

Halsey responded with an emphatic, “No, sir!” which was promptly seconded by Kinkaid. What was more, Halsey told MacArthur, if he stuck to those orders, he would be “hampering the war effort!”

MacArthur’s staff squirmed under this rebuke to their chief, and the argument lasted around an hour. Finally MacArthur seemed to acquiesce to Halsey’s plea, and the session adjourned, only to reconvene at MacArthur’s summons the following morning. “We went through the same argument as the afternoon before, almost word for word,” Halsey recalled, “and at the end of an hour we reached the same conclusion: the work would proceed.”

Halsey thought that ended the matter and prepared to return to Nouméa, but he was asked to return to MacArthur’s office again. “I’ll be damned,” wrote Halsey, “if we didn’t run the course a third time!” Finally MacArthur gave Halsey “a charming smile” and told him, “You win, Bill!”32

When Admiral Leahy published his memoirs in 1950, he opined in his characteristically understated and diplomatic way that, when it came to general Pacific strategy, “it appeared that MacArthur’s ideas might conflict with those of Nimitz, and the difference in the personalities of these two able commanders was going to require delicate handling.”33

Going on to recount the particulars of the Seeadler Harbor battle, Leahy wrote, drawing upon his diary: “MacArthur was reported to have said he would not stand for the Nimitz proposal, that the American people would not stand for it, that the Australians would not stand for it, and furthermore that nothing was going to be allowed to interfere with his march back to the Philippines.” This was pretty much a paraphrase of MacArthur’s points in his February 29 letter to Marshall.

As for Halsey, Leahy recounted, “Halsey, no shrinking violet himself, in turn charged that MacArthur was suffering from illusions of grandeur and that his staff officers were afraid to oppose any of their General’s plans whether or not they believed in them.” This generally squared with Halsey’s account in his memoirs.34

Nonetheless, when MacArthur received a galley proof of Leahy’s I Was There, he took exception to Leahy’s account, writing, “Dear Bill… the quoted statement is so lacking in factuality that I very much doubt its insertion was with your own personal knowledge.” MacArthur asked Leahy to eliminate the quoted passages from his book. “There has been much rumor mongering concerning my differences with Nimitz and Halsey,” MacArthur maintained, “and yet my relations with both have always been on the warmest plane of cordiality.”35

“Dear Douglas,” Leahy assured him in response, “nobody is better qualified than you are to comment on my notes insofar as they refer to the war in the Pacific.” However, Leahy claimed that his account was “taken from notes made by me at the time” and passed on to the Joint Chiefs, as was his custom, “in order that they might have all the information that came to us for use in their consideration of the problem and in reaching their decision.” Citing a publishing deadline, Leahy concluded, “I believe it would be practically impossible to eliminate that part of the text to which you offer objection.”36

Leahy termed MacArthur-navy relations and the Seeadler Harbor ruckus “the most controversial single problem before the JCS during March, 1944.”37 Considering that the chiefs were occupied with deciding how far and how rapidly Nimitz should push westward after seizing Eniwetok, whether to assault or bypass Truk, in the Carolines,38 and what role, if any, Formosa should play in an attack on Japan—not to mention planning the upcoming Normandy invasion—that was a significant assessment.

There was also an about-face. The chiefs reversed themselves and came to an overdue decision on Kavieng. Halsey had been right. There was no reason to force another bloody assault when Kavieng could be bypassed in the general envelopment of Rabaul. The Joint Chiefs told Halsey to take Emirau instead. He dusted off his plans, and South Pacific troops landed there without opposition on March 20. The only casualty was a broken leg when a Seabee fell off a bulldozer.

The Joint Chiefs also affirmed Marshall’s earlier caution to MacArthur. Manus and Seeadler Harbor would remain under MacArthur’s control in the Southwest Pacific Area, but he had best roll out the red carpet for the harbor’s use by all units of the US Navy, be they assigned to his Seventh Fleet, Halsey’s South Pacific Area, or the Pacific Fleet in general.

Just to be certain there was no misunderstanding, Admiral King circulated a memo that quoted from a JCS directive of almost two years before, when the chiefs had initially carved up the Pacific: “Boundary lines of ocean areas… give a general definition to usual fields of operations; they are not designed to restrict or prevent responsible commanders from extending operations outside their assigned areas when such action will assist or support friendly forces, when it is necessary to accomplish the task in hand, or when it will promote the common cause.”39

King’s reminder was perhaps a needless stab in MacArthur’s direction, but in a broader operational sense, it highlighted an area where MacArthur was still evolving. As much as MacArthur had come to embrace coordinated air and naval operations, he still showed the bias of his army roots by fixating on lines on a map, stationary fortifications, and rigidly defined areas of control rather than adopting the more fluid operational views traditionally espoused by the navy—out of necessity—on the seas. In short, whereas MacArthur’s pins tended to stay in place on the map, the navy’s were constantly moving. Although this was dictated to a large extent by geography, neither approach was necessarily correct, exclusive, or an assurance of victory. Rather, the differences between the two approaches begged for coordination and mutual support rather than routine avoidance.

Interservice bickering and MacArthur’s usual pontificating aside, his success in the Admiralties had an important effect on the Joint Chiefs and their view of him. He had gambled and won. Had he delayed the landings a month, until the projected April 1 date, it is probable that his forces would have faced reinforced defenses. That likely would have delayed operations against or beyond Wewak and/or Nimitz’s move to the Marianas rather than, as will be seen, expediting them.

The Joint Chiefs were far from easing up on their supervision of MacArthur, but his success in the Admiralties was the first step toward the virtual carte blanche his operations were to receive the following spring. Had his reconnaissance-in-force been repelled—or had he been captured or killed during his beachhead stroll—it would have had just the opposite effect.

The success in the Admiralties also emboldened MacArthur and his staff to draw lines on their maps ever farther afield, particularly if carrier aviation was available to support a leap beyond the range of Kenney’s land-based fighters. “Please accept my admiration for the manner in which the entire affair has been handled,” Marshall cabled MacArthur, speaking only to field operations, “and pass it on to Krueger, Kenney [and] Kinkaid.”40 The four men made a good team, and they were about to get ever bolder.